Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.4 Perception

Learning objectives.

- Understand the influence of self in the process of perception.

- Describe how we perceive visual objects and how these tendencies may affect our behavior.

- Describe the biases of self-perception.

- Describe the biases inherent in perception of other people.

- Explain what attributions mean, how we form attributions, and their consequences for organizational behavior.

Our behavior is not only a function of our personality, values, and preferences, but also of the situation. We interpret our environment, formulate responses, and act accordingly. Perception may be defined as the process with which individuals detect and interpret environmental stimuli. What makes human perception so interesting is that we do not solely respond to the stimuli in our environment. We go beyond the information that is present in our environment, pay selective attention to some aspects of the environment, and ignore other elements that may be immediately apparent to other people. Our perception of the environment is not entirely rational. For example, have you ever noticed that while glancing at a newspaper or a news Web site, information that is interesting or important to you jumps out of the page and catches your eye? If you are a sports fan, while scrolling down the pages you may immediately see a news item describing the latest success of your team. If you are the parent of a picky eater, an advice column on toddler feeding may be the first thing you see when looking at the page. So what we see in the environment is a function of what we value, our needs, our fears, and our emotions (Higgins & Bargh, 1987; Keltner, Ellsworth, & Edwards, 1993). In fact, what we see in the environment may be objectively, flat-out wrong because of our personality, values, or emotions. For example, one experiment showed that when people who were afraid of spiders were shown spiders, they inaccurately thought that the spider was moving toward them (Riskin, Moore, & Bowley, 1995). In this section, we will describe some common tendencies we engage in when perceiving objects or other people, and the consequences of such perceptions. Our coverage of biases and tendencies in perception is not exhaustive—there are many other biases and tendencies on our social perception.

Visual Perception

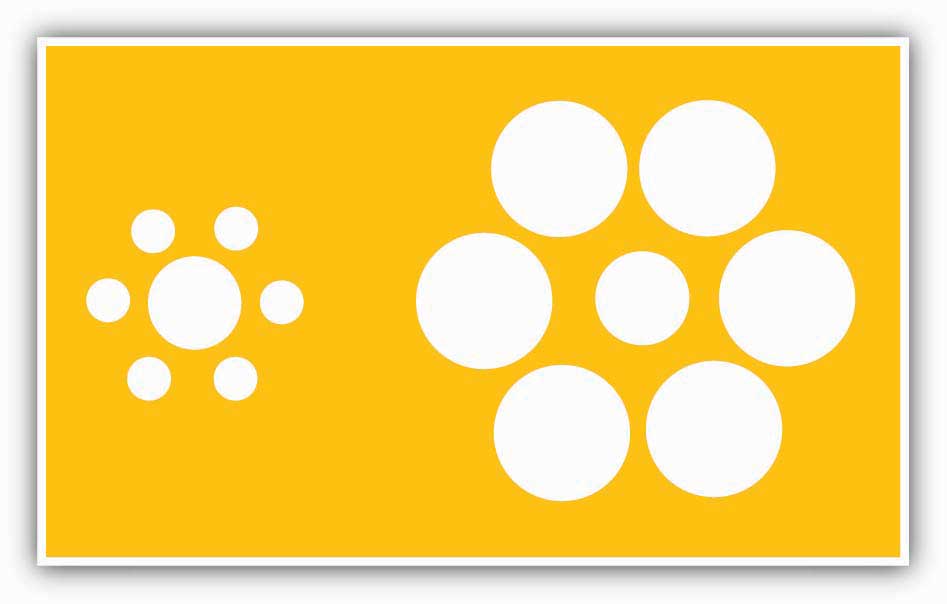

Our visual perception definitely goes beyond the physical information available to us. First of all, we extrapolate from the information available to us. Take a look at the following figure. The white triangle you see in the middle is not really there, but we extrapolate from the information available to us and see it there (Kellman & Shipley, 1991).

Our visual perception goes beyond the information physically available. In this figure, we see the white triangle in the middle even though it is not really there.

Which of the circles in the middle is bigger? At first glance, the one on the left may appear bigger, but they are in fact the same size. We compare the middle circle on the left to its surrounding circles, whereas the middle circle on the right is compared to the bigger circles surrounding it.

Our visual perception is often biased because we do not perceive objects in isolation. The contrast between our focus of attention and the remainder of the environment may make an object appear bigger or smaller. This principle is illustrated in the figure with circles. Which of the middle circles is bigger? To most people, the one on the left appears bigger, but this is because it is surrounded by smaller circles. The contrast between the focal object and the objects surrounding it may make an object bigger or smaller to our eye.

How do these tendencies influence behavior in organizations? You may have realized that the fact that our visual perception is faulty may make witness testimony faulty and biased. How do we know whether the employee you judge to be hardworking, fast, and neat is really like that? Is it really true, or are we comparing this person to other people in the immediate environment? Or let’s say that you do not like one of your peers and you think that this person is constantly surfing the Web during work hours. Are you sure? Have you really seen this person surf unrelated Web sites, or is it possible that the person was surfing the Web for work-related purposes? Our biased visual perception may lead to the wrong inferences about the people around us.

Self-Perception

Human beings are prone to errors and biases when perceiving themselves. Moreover, the type of bias people have depends on their personality. Many people suffer from self-enhancement bias . This is the tendency to overestimate our performance and capabilities and see ourselves in a more positive light than others see us. People who have a narcissistic personality are particularly subject to this bias, but many others are still prone to overestimating their abilities (John & Robins, 1994). At the same time, other people have the opposing extreme, which may be labeled as self-effacement bias . This is the tendency for people to underestimate their performance, undervalue capabilities, and see events in a way that puts them in a more negative light. We may expect that people with low self-esteem may be particularly prone to making this error. These tendencies have real consequences for behavior in organizations. For example, people who suffer from extreme levels of self-enhancement tendencies may not understand why they are not getting promoted or rewarded, while those who have a tendency to self-efface may project low confidence and take more blame for their failures than necessary.

When perceiving themselves, human beings are also subject to the false consensus error . Simply put, we overestimate how similar we are to other people (Fields & Schuman, 1976; Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). We assume that whatever quirks we have are shared by a larger number of people than in reality. People who take office supplies home, tell white lies to their boss or colleagues, or take credit for other people’s work to get ahead may genuinely feel that these behaviors are more common than they really are. The problem for behavior in organizations is that, when people believe that a behavior is common and normal, they may repeat the behavior more freely. Under some circumstances this may lead to a high level of unethical or even illegal behaviors.

Social Perception

How we perceive other people in our environment is also shaped by our values, emotions, feelings, and personality. Moreover, how we perceive others will shape our behavior, which in turn will shape the behavior of the person we are interacting with.

One of the factors biasing our perception is stereotypes . Stereotypes are generalizations based on group characteristics. For example, believing that women are more cooperative than men, or men are more assertive than women, is a stereotype. Stereotypes may be positive, negative, or neutral. Human beings have a natural tendency to categorize the information around them to make sense of their environment. What makes stereotypes potentially discriminatory and a perceptual bias is the tendency to generalize from a group to a particular individual. If the belief that men are more assertive than women leads to choosing a man over an equally (or potentially more) qualified female candidate for a position, the decision will be biased, potentially illegal, and unfair.

Stereotypes often create a situation called a self-fulfilling prophecy . This cycle occurs when people automatically behave as if an established stereotype is accurate, which leads to reactive behavior from the other party that confirms the stereotype (Snyder, Tanke, & Berscheid, 1977). If you have a stereotype such as “Asians are friendly,” you are more likely to be friendly toward an Asian yourself. Because you are treating the other person better, the response you get may also be better, confirming your original belief that Asians are friendly. Of course, just the opposite is also true. Suppose you believe that “young employees are slackers.” You are less likely to give a young employee high levels of responsibility or interesting and challenging assignments. The result may be that the young employee reporting to you may become increasingly bored at work and start goofing off, confirming your suspicions that young people are slackers!

Stereotypes persist because of a process called selective perception. Selective perception simply means that we pay selective attention to parts of the environment while ignoring other parts. When we observe our environment, we see what we want to see and ignore information that may seem out of place. Here is an interesting example of how selective perception leads our perception to be shaped by the context: As part of a social experiment, in 2007 the Washington Post newspaper arranged Joshua Bell, the internationally acclaimed violin virtuoso, to perform in a corner of the Metro station in Washington DC. The violin he was playing was worth $3.5 million, and tickets for Bell’s concerts usually cost around $100. During the rush hour in which he played for 45 minutes, only one person recognized him, only a few realized that they were hearing extraordinary music, and he made only $32 in tips. When you see someone playing at the metro station, would you expect them to be extraordinary? (Weingarten, 2007)

Our background, expectations, and beliefs will shape which events we notice and which events we ignore. For example, the functional background of executives affects the changes they perceive in their environment (Waller, Huber, & Glick, 1995). Executives with a background in sales and marketing see the changes in the demand for their product, while executives with a background in information technology may more readily perceive the changes in the technology the company is using. Selective perception may perpetuate stereotypes, because we are less likely to notice events that go against our beliefs. A person who believes that men drive better than women may be more likely to notice women driving poorly than men driving poorly. As a result, a stereotype is maintained because information to the contrary may not reach our brain.

First impressions are lasting. A job interview is one situation in which first impressions formed during the first few minutes may have consequences for your relationship with your future boss or colleagues.

World Relief Spokane – Job Interviews – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Let’s say we noticed information that goes against our beliefs. What then? Unfortunately, this is no guarantee that we will modify our beliefs and prejudices. First, when we see examples that go against our stereotypes, we tend to come up with subcategories. For example, when people who believe that women are more cooperative see a female who is assertive, they may classify this person as a “career woman.” Therefore, the example to the contrary does not violate the stereotype, and instead is explained as an exception to the rule (Higgins & Bargh, 1987). Second, we may simply discount the information. In one study, people who were either in favor of or opposed to the death penalty were shown two studies, one showing benefits from the death penalty and the other discounting any benefits. People rejected the study that went against their belief as methodologically inferior and actually reinforced the belief in their original position even more (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979). In other words, trying to debunk people’s beliefs or previously established opinions with data may not necessarily help.

One other perceptual tendency that may affect work behavior is that of first impressions . The first impressions we form about people tend to have a lasting impact. In fact, first impressions, once formed, are surprisingly resilient to contrary information. Even if people are told that the first impressions were caused by inaccurate information, people hold onto them to a certain degree. The reason is that, once we form first impressions, they become independent of the evidence that created them (Ross, Lepper, & Hubbard, 1975). Any information we receive to the contrary does not serve the purpose of altering the original impression. Imagine the first day you met your colleague Anne. She treated you in a rude manner and when you asked for her help, she brushed you off. You may form the belief that she is a rude and unhelpful person. Later, you may hear that her mother is very sick and she is very stressed. In reality she may have been unusually stressed on the day you met her. If you had met her on a different day, you could have thought that she is a really nice person who is unusually stressed these days. But chances are your impression that she is rude and unhelpful will not change even when you hear about her mother. Instead, this new piece of information will be added to the first one: She is rude, unhelpful, and her mother is sick. Being aware of this tendency and consciously opening your mind to new information may protect you against some of the downsides of this bias. Also, it would be to your advantage to pay careful attention to the first impressions you create, particularly during job interviews.

OB Toolbox: How Can I Make a Great First Impression in the Job Interview?

A job interview is your first step to getting the job of your dreams. It is also a social interaction in which your actions during the first 5 minutes will determine the impression you make. Here are some tips to help you create a positive first impression.

- Your first opportunity to make a great impression starts even before the interview, the moment you send your résumé . Be sure that you send your résumé to the correct people, and spell the name of the contact person correctly! Make sure that your résumé looks professional and is free from typos and grammar problems. Have someone else read it before you hit the send button or mail it.

- Be prepared for the interview . Many interviews have some standard questions such as “tell me about yourself” or “why do you want to work here?” Be ready to answer these questions. Prepare answers highlighting your skills and accomplishments, and practice your message. Better yet, practice an interview with a friend. Practicing your answers will prevent you from regretting your answers or finding a better answer after the interview is over!

- Research the company . If you know a lot about the company and the job in question, you will come out as someone who is really interested in the job. If you ask basic questions such as “what does this company do?” you will not be taken as a serious candidate. Visit the company’s Web site as well as others, and learn as much about the company and the job as you can.

- When you are invited for an office interview, be sure to dress properly . Like it or not, the manner you dress is a big part of the impression you make. Dress properly for the job and company in question. In many jobs, wearing professional clothes, such as a suit, is expected. In some information technology jobs, it may be more proper to wear clean and neat business casual clothes (such as khakis and a pressed shirt) as opposed to dressing formally. Do some investigation about what is suitable. Whatever the norm is, make sure that your clothes fit well and are clean and neat.

- Be on time to the interview . Being late will show that you either don’t care about the interview or you are not very reliable. While waiting for the interview, don’t forget that your interview has already started. As soon as you enter the company’s parking lot, every person you see on the way or talk to may be a potential influence over the decision maker. Act professionally and treat everyone nicely.

- During the interview, be polite . Use correct grammar, show eagerness and enthusiasm, and watch your body language. From your handshake to your posture, your body is communicating whether you are the right person for the job!

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Bruce, C. (2007, October). Business Etiquette 101: Making a good first impression. Black Collegian , 38(1), 78–80; Evenson, R. (2007, May). Making a great first impression. Techniques , 14–17; Mather, J., & Watson, M. (2008, May 23). Perfect candidate. The Times Educational Supplement , 4789 , 24–26; Messmer, M. (2007, July). 10 minutes to impress. Journal of Accountancy , 204 (1), 13; Reece, T. (2006, November–December). How to wow! Career World , 35 , 16–18.

Attributions

Your colleague Peter failed to meet the deadline. What do you do? Do you help him finish up his work? Do you give him the benefit of the doubt and place the blame on the difficulty of the project? Or do you think that he is irresponsible? Our behavior is a function of our perceptions. More specifically, when we observe others behave in a certain way, we ask ourselves a fundamental question: Why? Why did he fail to meet the deadline? Why did Mary get the promotion? Why did Mark help you when you needed help? The answer we give is the key to understanding our subsequent behavior. If you believe that Mark helped you because he is a nice person, your action will be different from your response if you think that Mark helped you because your boss pressured him to.

An attribution is the causal explanation we give for an observed behavior. If you believe that a behavior is due to the internal characteristics of an actor, you are making an internal attribution . For example, let’s say your classmate Erin complained a lot when completing a finance assignment. If you think that she complained because she is a negative person, you are making an internal attribution. An external attribution is explaining someone’s behavior by referring to the situation. If you believe that Erin complained because finance homework was difficult, you are making an external attribution.

When do we make internal or external attributions? Research shows that three factors are the key to understanding what kind of attributions we make.

Consensus : Do other people behave the same way?

Distinctiveness : Does this person behave the same way across different situations?

Consistency : Does this person behave this way in different occasions in the same situation?

Let’s assume that in addition to Erin, other people in the same class also complained (high consensus). Erin does not usually complain in other classes (high distinctiveness). Erin usually does not complain in finance class (low consistency). In this situation, you are likely to make an external attribution, such as thinking that finance homework is difficult. On the other hand, let’s assume that Erin is the only person complaining (low consensus). Erin complains in a variety of situations (low distinctiveness), and every time she is in finance, she complains (high consistency). In this situation, you are likely to make an internal attribution such as thinking that Erin is a negative person (Kelley, 1967; Kelley, 1973).

Interestingly though, our attributions do not always depend on the consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency we observe in a given situation. In other words, when making attributions, we do not always look at the situation objectively. For example, our overall relationship is a factor. When a manager likes a subordinate, the attributions made would be more favorable (successes are attributed to internal causes, while failures are attributed to external causes) (Heneman, Greenberger, & Anonyou, 1989). Moreover, when interpreting our own behavior, we suffer from self-serving bias . This is the tendency to attribute our failures to the situation while attributing our successes to internal causes (Malle, 2006).

Table 3.1 Consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency determine the type of attribution we make in a given situation.

| Consensus | Distinctiveness | Consistency | Type of attribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Everyone else behaves the same way. | This person does not usually behave this way in different situations. | This person does not usually behave this way in this situation. | |

| No one else behaves the same way. | This person usually behaves this way in different situations. | Every time this person is in this situation, he or she acts the same way. |

How we react to other people’s behavior would depend on the type of attributions we make. When faced with poor performance, such as missing a deadline, we are more likely to punish the person if an internal attribution is made (such as “the person being unreliable”). In the same situation, if we make an external attribution (such as “the timeline was unreasonable”), instead of punishing the person we might extend the deadline or assign more help to the person. If we feel that someone’s failure is due to external causes, we may feel empathy toward the person and even offer help (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). On the other hand, if someone succeeds and we make an internal attribution (he worked hard), we are more likely to reward the person, whereas an external attribution (the project was easy) is less likely to yield rewards for the person in question. Therefore, understanding attributions is important to predicting subsequent behavior.

Key Takeaway

Perception is how we make sense of our environment in response to environmental stimuli. While perceiving our surroundings, we go beyond the objective information available to us, and our perception is affected by our values, needs, and emotions. There are many biases that affect human perception of objects, self, and others. When perceiving the physical environment, we fill in gaps and extrapolate from the available information. We also contrast physical objects to their surroundings and may perceive something as bigger, smaller, slower, or faster than it really is. In self-perception, we may commit the self-enhancement or self-effacement bias, depending on our personality. We also overestimate how much we are like other people. When perceiving others, stereotypes infect our behavior. Stereotypes may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Stereotypes are perpetuated because of our tendency to pay selective attention to aspects of the environment and ignore information inconsistent with our beliefs. When perceiving others, the attributions we make will determine how we respond to the situation. Understanding the perception process gives us clues to understand human behavior.

- What are the implications of contrast error for interpersonal interactions? Does this error occur only when we observe physical objects? Or have you encountered this error when perceiving behavior of others?

- What are the problems of false consensus error? How can managers deal with this tendency?

- Is there such a thing as a “good” stereotype? Is a “good” stereotype useful or still problematic?

- How do we manage the fact that human beings develop stereotypes? How would you prevent stereotypes from creating unfairness in decision making?

- Is it possible to manage the attributions other people make about our behavior? Let’s assume that you have completed a project successfully. How would you maximize the chances that your manager will make an internal attribution? How would you increase the chances of an external attribution when you fail in a task?

Fields, J. M., & Schuman, H. (1976). Public beliefs about the beliefs of the public. Public Opinion Quarterly , 40 (4), 427–448.

Heneman, R. L., Greenberger, D. B., & Anonyou, C. (1989). Attributions and exchanges: The effects of interpersonal factors on the diagnosis of employee performance. Academy of Management Journal , 32 , 466–476.

Higgins, E. T., & Bargh, J. A. (1987). Social cognition and social perception. Annual Review of Psychology , 38 , 369–425.

John, O. P., & Robins, R. W. (1994). Accuracy and bias in self-perception: Individual differences in self-enhancement and the role of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 66 , 206–219.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation , 15 , 192–238.

Kelley, H. H. (1973). The processes of causal attribution. American Psychologist , 28 , 107–128.

Kellman, P. J., & Shipley, T. F. (1991). A theory of visual interpolation in object perception. Cognitive Psychology , 23 , 141–221.

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 64 , 740–752.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Peer responses to low performers: An attributional model of helping in the context of groups. Academy of Management Review , 26 , 67–84.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 37 , 2098–2109.

Malle, B. F. (2006). The actor-observer asymmetry in attribution: A (surprising) meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin , 132 , 895–919.

Riskind, J. H., Moore, R., & Bowley, L. (1995). The looming of spiders: The fearful perceptual distortion of movement and menace. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 33 , 171.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 13 , 279–301.

Ross, L., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self-perception and social perception: Biased attributional processes in the debriefing paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 32 , 880–892.

Snyder, M., Tanke, E. D., & Berscheid, E. (1977). Social perception and interpersonal behavior: On the self-fulfilling nature of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 35 , 656–666.

Waller, M. J., Huber, G. P., & Glick, W. H. (1995). Functional background as a determinant of executives’ selective perception. Academy of Management Journal , 38 , 943–974.

Weingarten, G. (2007, April 8). Pearls before breakfast. Washington Post . Retrieved January 29, 2009, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/04/AR2007040401721.html .

Organizational Behavior Copyright © 2017 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

3.1 The Perceptual Process

- How do differences in perception affect employee behavior and performance?

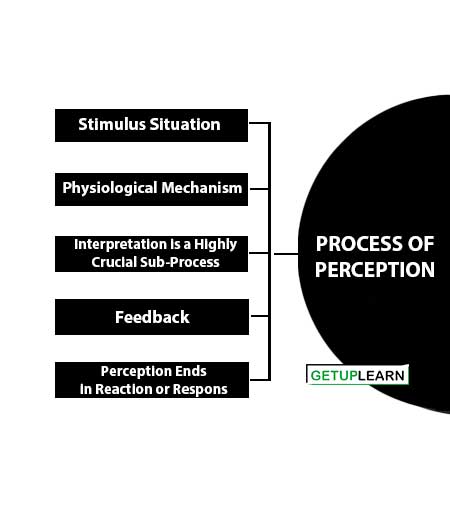

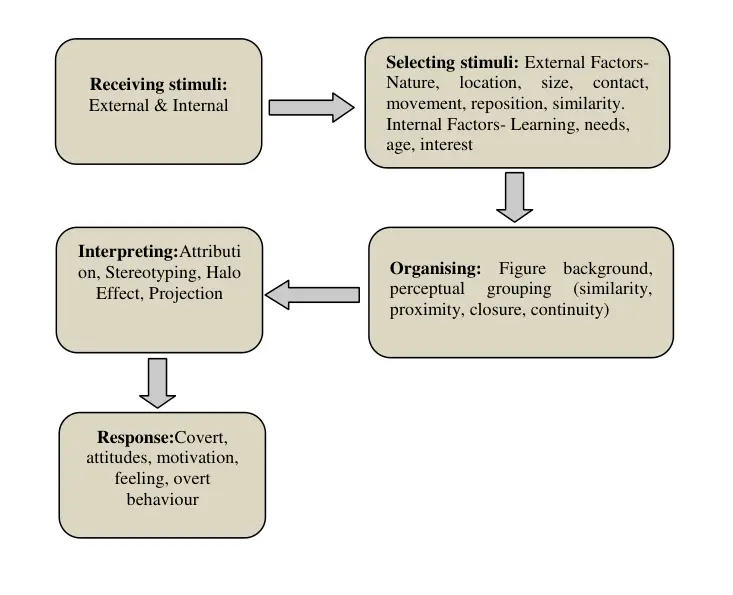

By perception , we mean the process by which one screens, selects, organizes, and interprets stimuli to give them meaning. 1 It is a process of making sense out of the environment in order to make an appropriate behavioral response. Perception does not necessarily lead to an accurate portrait of the environment, but rather to a unique portrait, influenced by the needs, desires, values, and disposition of the perceiver. As described by Kretch and associates, 2 an individual’s perception of a given situation is not a photographic representation of the physical world; it is a partial, personal construction in which certain objects, selected by the individual for a major role, are perceived in an individual manner. Every perceiver is, as it were, to some degree a nonrepresentational artist, painting a picture of the world that expresses an individual view of reality.

The multitude of objects that vie for attention are first selected or screened by individuals. This process is called perceptual selectivity . Certain of these objects catch our attention, while others do not. Once individuals notice a particular object, they then attempt to make sense out of it by organizing or categorizing it according to their unique frame of reference and their needs. This second process is termed perceptual organization . When meaning has been attached to an object, individuals are in a position to determine an appropriate response or reaction to it. Hence, if we clearly recognize and understand we are in danger from a falling rock or a car, we can quickly move out of the way.

Because of the importance of perceptual selectivity for understanding the perception of work situations, we will examine this concept in some detail before considering the topic of social perception.

Perceptual Selectivity: Seeing What We See

As noted above, perceptual selectivity refers to the process by which individuals select objects in the environment for attention. Without this ability to focus on one or a few stimuli instead of the hundreds constantly surrounding us, we would be unable to process all the information necessary to initiate behavior. In essence, perceptual selectivity works as follows (see Exhibit 3.2 ). The individual is first exposed to an object or stimulus—a loud noise, a new car, a tall building, another person, and so on. Next, the individual focuses attention on this one object or stimulus, as opposed to others, and concentrates his efforts on understanding or comprehending the stimulus. For example, while conducting a factory tour, two managers came across a piece of machinery. One manager’s attention focused on the stopped machine; the other manager focused on the worker who was trying to fix it. Both managers simultaneously asked the worker a question. The first manager asked why the machine was stopped, and the second manager asked if the employee thought that he could fix it. Both managers were presented with the same situation, but they noticed different aspects. This example illustrates that once attention has been directed, individuals are more likely to retain an image of the object or stimulus in their memory and to select an appropriate response to the stimulus. These various influences on selective attention can be divided into external influences and internal (personal) influences (see Exhibit 3.3 ).

External Influences on Selective Attention

External influences consist of the characteristics of the observed object or person that activate the senses. Most external influences affect selective attention because of either their physical properties or their dynamic properties.

Physical Properties. The physical properties of the objects themselves often affect which objects receive attention by the perceiver. Emphasis here is on the unique, different, and out of the ordinary. A particularly important physical property is size . Generally, larger objects receive more attention than smaller ones. Advertising companies use the largest signs and billboards allowed to capture the perceiver’s attention. However, when most of the surrounding objects are large, a small object against a field of large objects may receive more attention. In either case, size represents an important variable in perception. Moreover, brighter, louder, and more colorful objects tend to attract more attention than objects of less intensity . For example, when a factory foreman yells an order at his subordinates, it will probably receive more notice (although it may not receive the desired response) from workers. It must be remembered here, however, that intensity heightens attention only when compared to other comparable stimuli. If the foreman always yells, employees may stop paying much attention to the yelling. Objects that contrast strongly with the background against which they are observed tend to receive more attention than less-contrasting objects. An example of the contrast principle can be seen in the use of plant and highway safety signs. A terse message such as “Danger” is lettered in black against a yellow or orange background. A final physical characteristic that can heighten perceptual awareness is the novelty or unfamiliarity of the object. Specifically, the unique or unexpected seen in a familiar setting (an executive of a conservative company who comes to work in Bermuda shorts) or the familiar seen in an incongruous setting (someone in church holding a can of beer) will receive attention.

Dynamic Properties. The second set of external influences on selective attention are those that either change over time or derive their uniqueness from the order in which they are presented. The most obvious dynamic property is motion . We tend to pay attention to objects that move against a relatively static background. This principle has long been recognized by advertisers, who often use signs with moving lights or moving objects to attract attention. In an organizational setting, a clear example is a rate-buster, who shows up his colleagues by working substantially faster, attracting more attention.

Another principle basic to advertising is repetition of a message or image. Work instructions that are repeated tend to be received better, particularly when they concern a dull or boring task on which it is difficult to concentrate. This process is particularly effective in the area of plant safety. Most industrial accidents occur because of careless mistakes during monotonous activities. Repeating safety rules and procedures can often help keep workers alert to the possibilities of accidents.

Personal Influences on Selective Attention

In addition to a variety of external factors, several important personal factors are also capable of influencing the extent to which an individual pays attention to a particular stimulus or object in the environment. The two most important personal influences on perceptual readiness are response salience and response disposition .

Response Salience. This is a tendency to focus on objects that relate to our immediate needs or wants. Response salience in the work environment is easily identified. A worker who is tired from many hours of work may be acutely sensitive to the number of hours or minutes until quitting time. Employees negotiating a new contract may know to the penny the hourly wage of workers doing similar jobs across town. Managers with a high need to achieve may be sensitive to opportunities for work achievement, success, and promotion. Finally, female managers may be more sensitive than many male managers to condescending male attitudes toward women. Response salience, in turn, can distort our view of our surroundings. For example, as Ruch notes:

“Time spent on monotonous work is usually overestimated. Time spent in interesting work is usually underestimated. . . . Judgment of time is related to feelings of success or failure. Subjects who are experiencing failure judge a given interval as longer than do subjects who are experiencing success. A given interval of time is also estimated as longer by subjects trying to get through a task in order to reach a desired goal than by subjects working without such motivation.” 3

Response Disposition. Whereas response salience deals with immediate needs and concerns, response disposition is the tendency to recognize familiar objects more quickly than unfamiliar ones. The notion of response disposition carries with it a clear recognition of the importance of past learning on what we perceive in the present. For instance, in one study, a group of individuals was presented with a set of playing cards with the colors and symbols reversed—that is, hearts and diamonds were printed in black, and spades and clubs in red. Surprisingly, when subjects were presented with these cards for brief time periods, individuals consistently described the cards as they expected them to be (red hearts and diamonds, black spades and clubs) instead of as they really were. They were predisposed to see things as they always had been in the past. 4

Thus, the basic perceptual process is in reality a fairly complicated one. Several factors, including our own personal makeup and the environment, influence how we interpret and respond to the events we focus on. Although the process itself may seem somewhat complicated, it in fact represents a shorthand to guide us in our everyday behavior. That is, without perceptual selectivity we would be immobilized by the millions of stimuli competing for our attention and action. The perceptual process allows us to focus our attention on the more salient events or objects and, in addition, allows us to categorize such events or objects so that they fit into our own conceptual map of the environment.

Expanding Around the Globe

Which car would you buy.

When General Motors teamed up with Toyota to form California-based New United Motor Manufacturing Inc. (NUMMI), they had a great idea. NUMMI would manufacture not only the popular Toyota Corolla but would also make a GM car called the Geo Prizm. Both cars would be essentially identical except for minor styling differences. Economies of scale and high quality would benefit the sales of both cars. Unfortunately, General Motors forgot one thing. The North American consumer holds a higher opinion of Japanese-built cars than American-made ones. As a result, from the start of the joint venture, Corollas have sold rapidly, while sales of Geo Prizms have languished.

With hindsight, it is easy to explain what happened in terms of perceptual differences. That is, the typical consumer simply perceived the Corolla to be of higher quality (and perhaps higher status) and bought accordingly. Not only was the Prizm seen more skeptically by consumers, but General Motors’ insistence on a whole new name for the product left many buyers unfamiliar with just what they were buying. Perception was that main reason for lagging sales; however, the paint job on the Prizm was viewed as being among the worst ever. As a result, General Motors lost $80 million on the Prizm in its first year of sales. Meanwhile, demand for the Corolla exceeded supply.

The final irony here is that no two cars could be any more alike than the Prizm and the Corolla. They are built on the same assembly line by the same workers to the same design specifications. They are, in fact, the same car. The only difference is in how the consumers perceive the two cars—and these perceptions obviously are radically different.

Over time, however, perceptions did change. While there was nothing unique about the Prizm, the vehicle managed to sell pretty well for the automaker and carried on well into the 2000s. The Prizm was also the base for the Pontiac Vibe, which was based on the Corolla platform as well, and this is one of the few collaborations that worked really well.

Sources: C. Eitreim, “10 Odd Automotive Brand Collaborations (And 15 That Worked),” Car Culture , January 19, 2019; R. Hof, “This Team-Up Has It All—Except Sales,” Business Week, August 14, 1989, p. 35; C. Eitreim, “15 GM Cars With The Worst Factory Paint Jobs (And 5 That'll Last Forever),” Motor Hub , November 8, 2018.

Social Perception in Organizations

Up to this point, we have focused on an examination of basic perceptual processes—how we see objects or attend to stimuli. Based on this discussion, we are now ready to examine a special case of the perceptual process— social perception as it relates to the workplace. Social perception consists of those processes by which we perceive other people. 5 Particular emphasis in the study of social perception is placed on how we interpret other people, how we categorize them, and how we form impressions of them.

Clearly, social perception is far more complex than the perception of inanimate objects such as tables, chairs, signs, and buildings. This is true for at least two reasons. First, people are obviously far more complex and dynamic than tables and chairs. More-careful attention must be paid in perceiving them so as not to miss important details. Second, an accurate perception of others is usually far more important to us personally than are our perceptions of inanimate objects. The consequences of misperceiving people are great. Failure to accurately perceive the location of a desk in a large room may mean we bump into it by mistake. Failure to perceive accurately the hierarchical status of someone and how the person cares about this status difference might lead you to inappropriately address the person by their first name or use slang in their presence and thereby significantly hurt your chances for promotion if that person is involved in such decisions. Consequently, social perception in the work situation deserves special attention.

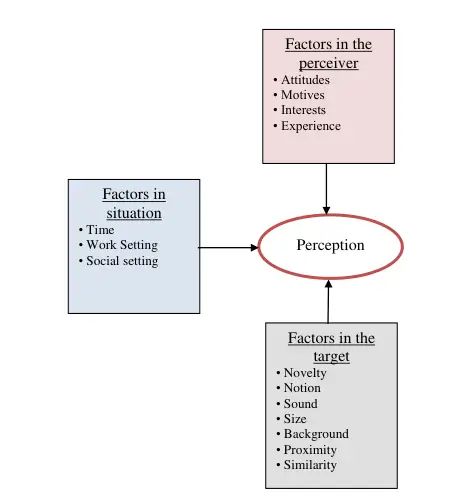

We will concentrate now on the three major influences on social perception: the characteristics of (1) the person being perceived, (2) the particular situation, and (3) the perceiver. When taken together, these influences are the dimensions of the environment in which we view other people. It is important for students of management to understand the way in which they interact (see Exhibit 3.4 ).

The way in which we are evaluated in social situations is greatly influenced by our own unique sets of personal characteristics. That is, our dress, talk, and gestures determine the kind of impressions people form of us. In particular, four categories of personal characteristics can be identified: (1) physical appearance, (2) verbal communication, (3) nonverbal communication, and (4) ascribed attributes.

Physical Appearance. A variety of physical attributes influence our overall image. These include many of the obvious demographic characteristics such as age, sex, race, height, and weight. A study by Mason found that most people agree on the physical attributes of a leader (i.e., what leaders should look like), even though these attributes were not found to be consistently held by actual leaders. However, when we see a person who appears to be assertive, goal-oriented, confident, and articulate, we infer that this person is a natural leader. 6 Another example of the powerful influence of physical appearance on perception is clothing. People dressed in business suits are generally thought to be professionals, whereas people dressed in work clothes are assumed to be lower-level employees.

Verbal and Nonverbal Communication. What we say to others—as well as how we say it—can influence the impressions others form of us. Several aspects of verbal communication can be noted. First, the precision with which one uses language can influence impressions about cultural sophistication or education. An accent provides clues about a person’s geographic and social background. The tone of voice used provides clues about a speaker’s state of mind. Finally, the topics people choose to converse about provide clues about them.

Impressions are also influenced by nonverbal communication—how people behave. For instance, facial expressions often serve as clues in forming impressions of others. People who consistently smile are often thought to have positive attitudes. 7 A whole field of study that has recently emerged is body language , the way in which people express their inner feelings subconsciously through physical actions: sitting up straight versus being relaxed, looking people straight in the eye versus looking away from people. These forms of expressive behavior provide information to the perceiver concerning how approachable others are, how self-confident they are, or how sociable they are.

Ascribed Attributes. Finally, we often ascribe certain attributes to a person before or at the beginning of an encounter; these attributes can influence how we perceive that person. Three ascribed attributes are status, occupation, and personal characteristics. We ascribe status to someone when we are told that the person is an executive, holds the greatest sales record, or has in some way achieved unusual fame or wealth. Research has consistently shown that people attribute different motives to people they believe to be high or low in status, even when these people behave in an identical fashion. 8 For instance, high-status people are seen as having greater control over their behavior and as being more self-confident and competent; they are given greater influence in group decisions than low-status people. Moreover, high-status people are generally better liked than low-status people. Occupations also play an important part in how we perceive people. Describing people as salespersons, accountants, teamsters, or research scientists conjures up distinct pictures of these various people before any firsthand encounters. In fact, these pictures may even determine whether there can be an encounter.

Characteristics of the Situation

The second major influence on how we perceive others is the situation in which the perceptual process occurs. Two situational influences can be identified: (1) the organization and the employee’s place in it, and (2) the location of the event.

Organizational Role. An employee’s place in the organizational hierarchy can also influence his perceptions. A classic study of managers by Dearborn and Simon emphasizes this point. In this study, executives from various departments (accounting, sales, production) were asked to read a detailed and factual case about a steel company. 9 Next, each executive was asked to identify the major problem a new president of the company should address. The findings showed clearly that the executives’ perceptions of the most important problems in the company were influenced by the departments in which they worked. Sales executives saw sales as the biggest problem, whereas production executives cited production issues. Industrial relations and public relations executives identified human relations as the primary problem in need of attention.

In addition to perceptual differences emerging horizontally across departments, such differences can also be found when we move vertically up or down the hierarchy. The most obvious difference here is seen between managers and unions, where the former see profits, production, and sales as vital areas of concern for the company whereas the latter place much greater emphasis on wages, working conditions, and job security. Indeed, our views of managers and workers are clearly influenced by the group to which we belong. The positions we occupy in organizations can easily color how we view our work world and those in it. Consider the results of a classic study of perceptual differences between superiors and subordinates. 10 Both groups were asked how often the supervisor gave various forms of feedback to the employees. The results, shown in Table 3.1 , demonstrate striking differences based on one’s location in the organizational hierarchy.

| Differences in Perception between Supervisors and Subordinates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency with Which Supervisors Give Various Types of Recognition for Good Performance | ||

| Types of Recognition | As Seen by Supervisors | As Seen by Subordinates |

| Gives privileges | ||

| Gives more responsibility | ||

| Gives a pat on the back | ||

| Gives sincere and thorough praise | ||

| Trains for better jobs | ||

| Gives more interesting work | ||

| Source: Adapted from R. Likert, New Patterns in Management (New York: McGraw Hill, 1961), p. 91. | ||

Location of Event. Finally, how we interpret events is also influenced by where the event occurs. Behaviors that may be appropriate at home, such as taking off one’s shoes, may be inappropriate in the office. Acceptable customs vary from country to country. For instance, assertiveness may be a desirable trait for a sales representative in the United States, but it may be seen as being brash or coarse in Japan or China. Hence, the context in which the perceptual activity takes place is important.

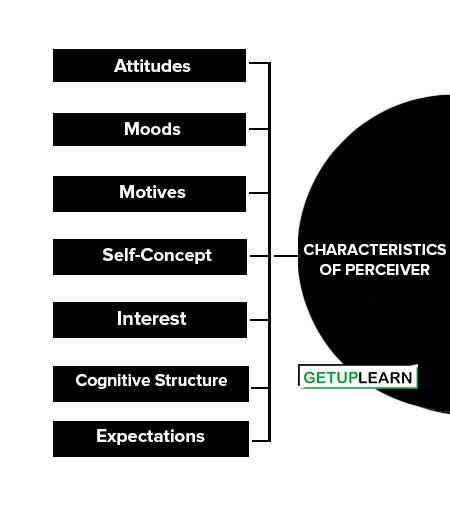

Characteristics of the Perceiver

The third major influence on social perception is the personality and viewpoint of the perceiver. Several characteristics unique to our personalities can affect how we see others. These include (1) self-concept, (2) cognitive structure, (3) response salience, and (4) previous experience with the individual. 11

Self-Concept. Our self-concept represents a major influence on how we perceive others. This influence is manifested in several ways. First, when we understand ourselves (i.e., can accurately describe our own personal characteristics), we are better able to perceive others accurately. Second, when we accept ourselves (i.e., have a positive self-image), we are more likely to see favorable characteristics in others. Studies have shown that if we accept ourselves as we are, we broaden our view of others and are more likely to view people uncritically. Conversely, less secure people often find faults in others. Third, our own personal characteristics influence the characteristics we notice in others. For instance, people with authoritarian tendencies tend to view others in terms of power, whereas secure people tend to see others as warm rather than cold. 12 From a management standpoint, these findings emphasize how important it is for administrators to understand themselves; they also provide justification for the human relations training programs that are popular in many organizations today.

Cognitive Structure. Our cognitive structures also influence how we view people. People describe each other differently. Some use physical characteristics such as tall or short, whereas others use central descriptions such as deceitful, forceful, or meek. Still others have more complex cognitive structures and use multiple traits in their descriptions of others; hence, a person may be described as being aggressive, honest, friendly, and hardworking. (See the discussion in Individual and Cultural Differences on cognitive complexity.) Ostensibly, the greater our cognitive complexity—our ability to differentiate between people using multiple criteria—the more accurate our perception of others. People who tend to make more complex assessments of others also tend to be more positive in their appraisals. 13 Research in this area highlights the importance of selecting managers who exhibit high degrees of cognitive complexity. These individuals should form more accurate perceptions of the strengths and weaknesses of their subordinates and should be able to capitalize on their strengths while ignoring or working to overcome their weaknesses.

Response Salience. This refers to our sensitivity to objects in the environment as influenced by our particular needs or desires. Response salience can play an important role in social perception because we tend to see what we want to see. A company personnel manager who has a bias against women, minorities, or handicapped persons would tend to be adversely sensitive to them during an employment interview. This focus may cause the manager to look for other potentially negative traits in the candidate to confirm his biases. The influence of positive arbitrary biases is called the halo effect , whereas the influence of negative biases is often called the horn effect . Another personnel manager without these biases would be much less inclined to be influenced by these characteristics when viewing prospective job candidates.

Previous Experience with the Individual. Our previous experiences with others often will influence the way in which we view their current behavior. When an employee has consistently received poor performance evaluations, a marked improvement in performance may go unnoticed because the supervisor continues to think of the individual as a poor performer. Similarly, employees who begin their careers with several successes develop a reputation as fast-track individuals and may continue to rise in the organization long after their performance has leveled off or even declined. The impact of previous experience on present perceptions should be respected and studied by students of management. For instance, when a previously poor performer earnestly tries to perform better, it is important for this improvement to be recognized early and properly rewarded. Otherwise, employees may give up, feeling that nothing they do will make any difference.

Together, these factors determine the impressions we form of others (see Exhibit 3.4 ). With these impressions, we make conscious and unconscious decisions about how we intend to behave toward people. Our behavior toward others, in turn, influences the way they regard us. Consequently, the importance of understanding the perceptual process, as well as factors that contribute to it, is apparent for managers. A better understanding of ourselves and careful attention to others leads to more accurate perceptions and more appropriate actions.

Concept Check

- How can you understand what makes up an individual’s personality?

- How does the content of the situation affect the perception of the perceiver?

- What are the characteristics that the perceiver can have on interpreting personality?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: J. Stewart Black, David S. Bright

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Organizational Behavior

- Publication date: Jun 5, 2019

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/3-1-the-perceptual-process

© Jan 9, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Organizational behavior.

- Neal M. Ashkanasy Neal M. Ashkanasy University of Queensland

- and Alana D. Dorris Alana D. Dorris University of Queensland

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.23

- Published online: 29 March 2017

Organizational behavior (OB) is a discipline that includes principles from psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Its focus is on understanding how people behave in organizational work environments. Broadly speaking, OB covers three main levels of analysis: micro (individuals), meso (groups), and macro (the organization). Topics at the micro level include managing the diverse workforce; effects of individual differences in attitudes; job satisfaction and engagement, including their implications for performance and management; personality, including the effects of different cultures; perception and its effects on decision-making; employee values; emotions, including emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and the effects of positive and negative affect on decision-making and creativity (including common biases and errors in decision-making); and motivation, including the effects of rewards and goal-setting and implications for management. Topics at the meso level of analysis include group decision-making; managing work teams for optimum performance (including maximizing team performance and communication); managing team conflict (including the effects of task and relationship conflict on team effectiveness); team climate and group emotional tone; power, organizational politics, and ethical decision-making; and leadership, including leadership development and leadership effectiveness. At the organizational level, topics include organizational design and its effect on organizational performance; affective events theory and the physical environment; organizational culture and climate; and organizational change.

- organizational psychology

- organizational sociology

- organizational anthropology

Introduction

Organizational behavior (OB) is the study of how people behave in organizational work environments. More specifically, Robbins, Judge, Millett, and Boyle ( 2014 , p. 8) describe it as “[a] field of study that investigates the impact that individual groups and structure have on behavior within organizations, for the purposes of applying such knowledge towards improving an organization’s effectiveness.” The OB field looks at the specific context of the work environment in terms of human attitudes, cognition, and behavior, and it embodies contributions from psychology, social psychology, sociology, and anthropology. The field is also rapidly evolving because of the demands of today’s fast-paced world, where technology has given rise to work-from-home employees, globalization, and an ageing workforce. Thus, while managers and OB researchers seek to help employees find a work-life balance, improve ethical behavior (Ardichivili, Mitchell, & Jondle, 2009 ), customer service, and people skills (see, e.g., Brady & Cronin, 2001 ), they must simultaneously deal with issues such as workforce diversity, work-life balance, and cultural differences.

The most widely accepted model of OB consists of three interrelated levels: (1) micro (the individual level), (2) meso (the group level), and (3) macro (the organizational level). The behavioral sciences that make up the OB field contribute an element to each of these levels. In particular, OB deals with the interactions that take place among the three levels and, in turn, addresses how to improve performance of the organization as a whole.

In order to study OB and apply it to the workplace, it is first necessary to understand its end goal. In particular, if the goal is organizational effectiveness, then these questions arise: What can be done to make an organization more effective? And what determines organizational effectiveness? To answer these questions, dependent variables that include attitudes and behaviors such as productivity, job satisfaction, job performance, turnover intentions, withdrawal, motivation, and workplace deviance are introduced. Moreover, each level—micro, meso, and macro—has implications for guiding managers in their efforts to create a healthier work climate to enable increased organizational performance that includes higher sales, profits, and return on investment (ROE).

The Micro (Individual) Level of Analysis

The micro or individual level of analysis has its roots in social and organizational psychology. In this article, six central topics are identified and discussed: (1) diversity; (2) attitudes and job satisfaction; (3) personality and values; (4) emotions and moods; (5) perception and individual decision-making; and (6) motivation.

An obvious but oft-forgotten element at the individual level of OB is the diverse workforce. It is easy to recognize how different each employee is in terms of personal characteristics like age, skin color, nationality, ethnicity, and gender. Other, less biological characteristics include tenure, religion, sexual orientation, and gender identity. In the Australian context, while the Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act of 1992 helped to increase participation of people with disabilities working in organizations, discrimination and exclusion still continue to inhibit equality (Feather & Boeckmann, 2007 ). In Western societies like Australia and the United States, however, antidiscrimination legislation is now addressing issues associated with an ageing workforce.

In terms of gender, there continues to be significant discrimination against female employees. Males have traditionally had much higher participation in the workforce, with only a significant increase in the female workforce beginning in the mid-1980s. Additionally, according to Ostroff and Atwater’s ( 2003 ) study of engineering managers, female managers earn a significantly lower salary than their male counterparts, especially when they are supervising mostly other females.

Job Satisfaction and Job Engagement

Job satisfaction is an attitudinal variable that comes about when an employee evaluates all the components of her or his job, which include affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects (Weiss, 2002 ). Increased job satisfaction is associated with increased job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), and reduced turnover intentions (Wilkin, 2012 ). Moreover, traditional workers nowadays are frequently replaced by contingent workers in order to reduce costs and work in a nonsystematic manner. According to Wilkin’s ( 2012 ) findings, however, contingent workers as a group are less satisfied with their jobs than permanent employees are.

Job engagement concerns the degree of involvement that an employee experiences on the job (Kahn, 1990 ). It describes the degree to which an employee identifies with their job and considers their performance in that job important; it also determines that employee’s level of participation within their workplace. Britt, Dickinson, Greene-Shortridge, and McKibbin ( 2007 ) describe the two extremes of job satisfaction and employee engagement: a feeling of responsibility and commitment to superior job performance versus a feeling of disengagement leading to the employee wanting to withdraw or disconnect from work. The first scenario is also related to organizational commitment, the level of identification an employee has with an organization and its goals. Employees with high organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and employee engagement tend to perceive that their organization values their contribution and contributes to their wellbeing.

Personality represents a person’s enduring traits. The key here is the concept of enduring . The most widely adopted model of personality is the so-called Big Five (Costa & McCrae, 1992 ): extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness. Employees high in conscientiousness tend to have higher levels of job knowledge, probably because they invest more into learning about their role. Those higher in emotional stability tend to have higher levels of job satisfaction and lower levels of stress, most likely because of their positive and opportunistic outlooks. Agreeableness, similarly, is associated with being better liked and may lead to higher employee performance and decreased levels of deviant behavior.

Although the personality traits in the Big Five have been shown to relate to organizational behavior, organizational performance, career success (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 2006 ), and other personality traits are also relevant to the field. Examples include positive self-evaluation, self-monitoring (the degree to which an individual is aware of comparisons with others), Machiavellianism (the degree to which a person is practical, maintains emotional distance, and believes the end will justify the means), narcissism (having a grandiose sense of self-importance and entitlement), risk-taking, proactive personality, and type A personality. In particular, those who like themselves and are grounded in their belief that they are capable human beings are more likely to perform better because they have fewer self-doubts that may impede goal achievements. Individuals high in Machiavellianism may need a certain environment in order to succeed, such as a job that requires negotiation skills and offers significant rewards, although their inclination to engage in political behavior can sometimes limit their potential. Employees who are high on narcissism may wreak organizational havoc by manipulating subordinates and harming the overall business because of their over-inflated perceptions of self. Higher levels of self-monitoring often lead to better performance but they may cause lower commitment to the organization. Risk-taking can be positive or negative; it may be great for someone who thrives on rapid decision-making, but it may prove stressful for someone who likes to weigh pros and cons carefully before making decisions. Type A individuals may achieve high performance but may risk doing so in a way that causes stress and conflict. Proactive personality, on the other hand, is usually associated with positive organizational performance.

Employee Values

Personal value systems are behind each employee’s attitudes and personality. Each employee enters an organization with an already established set of beliefs about what should be and what should not be. Today, researchers realize that personality and values are linked to organizations and organizational behavior. Years ago, only personality’s relation to organizations was of concern, but now managers are more interested in an employee’s flexibility to adapt to organizational change and to remain high in organizational commitment. Holland’s ( 1973 ) theory of personality-job fit describes six personality types (realistic, investigative, social, conventional, enterprising, and artistic) and theorizes that job satisfaction and turnover are determined by how well a person matches her or his personality to a job. In addition to person-job (P-J) fit, researchers have also argued for person-organization (P-O) fit, whereby employees desire to be a part of and are selected by an organization that matches their values. The Big Five would suggest, for example, that extraverted employees would desire to be in team environments; agreeable people would align well with supportive organizational cultures rather than more aggressive ones; and people high on openness would fit better in organizations that emphasize creativity and innovation (Anderson, Spataro, & Flynn, 2008 ).

Individual Differences, Affect, and Emotion

Personality predisposes people to have certain moods (feelings that tend to be less intense but longer lasting than emotions) and emotions (intense feelings directed at someone or something). In particular, personalities with extraversion and emotional stability partially determine an individual predisposition to experience emotion more or less intensely.

Affect is also related as describing the positive and negative feelings that people experience (Ashkanasy, 2003 ). Moreover, emotions, mood, and affect interrelate; a bad mood, for instance, can lead individuals to experience a negative emotion. Emotions are action-oriented while moods tend to be more cognitive. This is because emotions are caused by a specific event that might only last a few seconds, while moods are general and can last for hours or even days. One of the sources of emotions is personality. Dispositional or trait affects correlate, on the one hand, with personality and are what make an individual more likely to respond to a situation in a predictable way (Watson & Tellegen, 1985 ). Moreover, like personality, affective traits have proven to be stable over time and across settings (Diener, Larsen, Levine, & Emmons, 1985 ; Watson, 1988 ; Watson & Tellegen, 1985 ; Watson & Walker, 1996 ). State affect, on the other hand, is similar to mood and represents how an individual feels in the moment.

The Role of Affect in Organizational Behavior

For many years, affect and emotions were ignored in the field of OB despite being fundamental factors underlying employee behavior (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995 ). OB researchers traditionally focused on solely decreasing the effects of strong negative emotions that were seen to impede individual, group, and organizational level productivity. More recent theories of OB focus, however, on affect, which is seen to have positive, as well as negative, effects on behavior, described by Barsade, Brief, and Spataro ( 2003 , p. 3) as the “affective revolution.” In particular, scholars now understand that emotions can be measured objectively and be observed through nonverbal displays such as facial expression and gestures, verbal displays, fMRI, and hormone levels (Ashkanasy, 2003 ; Rashotte, 2002 ).

Fritz, Sonnentag, Spector, and McInroe ( 2010 ) focus on the importance of stress recovery in affective experiences. In fact, an individual employee’s affective state is critical to OB, and today more attention is being focused on discrete affective states. Emotions like fear and sadness may be related to counterproductive work behaviors (Judge et al., 2006 ). Stress recovery is another factor that is essential for more positive moods leading to positive organizational outcomes. In a study, Fritz et al. ( 2010 ) looked at levels of psychological detachment of employees on weekends away from the workplace and how it was associated with higher wellbeing and affect.

Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Labor

Ashkanasy and Daus ( 2002 ) suggest that emotional intelligence is distinct but positively related to other types of intelligence like IQ. It is defined by Mayer and Salovey ( 1997 ) as the ability to perceive, assimilate, understand, and manage emotion in the self and others. As such, it is an individual difference and develops over a lifetime, but it can be improved with training. Boyatzis and McKee ( 2005 ) describe emotional intelligence further as a form of adaptive resilience, insofar as employees high in emotional intelligence tend to engage in positive coping mechanisms and take a generally positive outlook toward challenging work situations.

Emotional labor occurs when an employee expresses her or his emotions in a way that is consistent with an organization’s display rules, and usually means that the employee engages in either surface or deep acting (Hochschild, 1983 ). This is because the emotions an employee is expressing as part of their role at work may be different from the emotions they are actually feeling (Ozcelik, 2013 ). Emotional labor has implications for an employee’s mental and physical health and wellbeing. Moreover, because of the discrepancy between felt emotions (how an employee actually feels) and displayed emotions or surface acting (what the organization requires the employee to emotionally display), surface acting has been linked to negative organizational outcomes such as heightened emotional exhaustion and reduced commitment (Erickson & Wharton, 1997 ; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002 ; Grandey, 2003 ; Groth, Hennig-Thurau, & Walsh, 2009 ).

Affect and Organizational Decision-Making

Ashkanasy and Ashton-James ( 2008 ) make the case that the moods and emotions managers experience in response to positive or negative workplace situations affect outcomes and behavior not only at the individual level, but also in terms of strategic decision-making processes at the organizational level. These authors focus on affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996 ), which holds that organizational events trigger affective responses in organizational members, which in turn affect organizational attitudes, cognition, and behavior.

Perceptions and Behavior

Like personality, emotions, moods, and attitudes, perceptions also influence employees’ behaviors in the workplace. Perception is the way in which people organize and interpret sensory cues in order to give meaning to their surroundings. It can be influenced by time, work setting, social setting, other contextual factors such as time of day, time of year, temperature, a target’s clothing or appearance, as well as personal trait dispositions, attitudes, and value systems. In fact, a person’s behavior is based on her or his perception of reality—not necessarily the same as actual reality. Perception greatly influences individual decision-making because individuals base their behaviors on their perceptions of reality. In this regard, attribution theory (Martinko, 1995 ) outlines how individuals judge others and is our attempt to conclude whether a person’s behavior is internally or externally caused.

Decision-Making and the Role of Perception

Decision-making occurs as a reaction to a problem when the individual perceives there to be discrepancy between the current state of affairs and the state s/he desires. As such, decisions are the choices individuals make from a set of alternative courses of action. Each individual interprets information in her or his own way and decides which information is relevant to weigh pros and cons of each decision and its alternatives to come to her or his perception of the best outcome. In other words, each of our unique perceptual processes influences the final outcome (Janis & Mann, 1977 ).

Common Biases in Decision-Making

Although there is no perfect model for approaching decision-making, there are nonetheless many biases that individuals can make themselves aware of in order to maximize their outcomes. First, overconfidence bias is an inclination to overestimate the correctness of a decision. Those most likely to commit this error tend to be people with weak intellectual and interpersonal abilities. Anchoring bias occurs when individuals focus on the first information they receive, failing to adjust for information received subsequently. Marketers tend to use anchors in order to make impressions on clients quickly and project their brand names. Confirmation bias occurs when individuals only use facts that support their decisions while discounting all contrary views. Lastly, availability bias occurs when individuals base their judgments on information readily available. For example, a manager might rate an employee on a performance appraisal based on behavior in the past few days, rather than the past six months or year.

Errors in Decision-Making

Other errors in decision-making include hindsight bias and escalation of commitment . Hindsight bias is a tendency to believe, incorrectly, after an outcome of an event has already happened, that the decision-maker would have accurately predicted that same outcome. Furthermore, this bias, despite its prevalence, is especially insidious because it inhibits the ability to learn from the past and take responsibility for mistakes. Escalation of commitment is an inclination to continue with a chosen course of action instead of listening to negative feedback regarding that choice. When individuals feel responsible for their actions and those consequences, they escalate commitment probably because they have invested so much into making that particular decision. One solution to escalating commitment is to seek a source of clear, less distorted feedback (Staw, 1981 ).

The last but certainly not least important individual level topic is motivation. Like each of the topics discussed so far, a worker’s motivation is also influenced by individual differences and situational context. Motivation can be defined as the processes that explain a person’s intensity, direction, and persistence toward reaching a goal. Work motivation has often been viewed as the set of energetic forces that determine the form, direction, intensity, and duration of behavior (Latham & Pinder, 2005 ). Motivation can be further described as the persistence toward a goal. In fact many non-academics would probably describe it as the extent to which a person wants and tries to do well at a particular task (Mitchell, 1982 ).

Early theories of motivation began with Maslow’s ( 1943 ) hierarchy of needs theory, which holds that each person has five needs in hierarchical order: physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization. These constitute the “lower-order” needs, while social and esteem needs are “higher-order” needs. Self-esteem for instance underlies motivation from the time of childhood. Another early theory is McGregor’s ( 1960 ) X-Y theory of motivation: Theory X is the concept whereby individuals must be pushed to work; and theory Y is positive, embodying the assumption that employees naturally like work and responsibility and can exercise self-direction.

Herzberg subsequently proposed the “two-factor theory” that attitude toward work can determine whether an employee succeeds or fails. Herzberg ( 1966 ) relates intrinsic factors, like advancement in a job, recognition, praise, and responsibility to increased job satisfaction, while extrinsic factors like the organizational climate, relationship with supervisor, and salary relate to job dissatisfaction. In other words, the hygiene factors are associated with the work context while the motivators are associated with the intrinsic factors associated with job motivation.

Contemporary Theories of Motivation

Although traditional theories of motivation still appear in OB textbooks, there is unfortunately little empirical data to support their validity. More contemporary theories of motivation, with more acceptable research validity, include self-determination theory , which holds that people prefer to have control over their actions. If a task an individual enjoyed now feels like a chore, then this will undermine motivation. Higher self-determined motivation (or intrinsically determined motivation) is correlated with increased wellbeing, job satisfaction, commitment, and decreased burnout and turnover intent. In this regard, Fernet, Gagne, and Austin ( 2010 ) found that work motivation relates to reactions to interpersonal relationships at work and organizational burnout. Thus, by supporting work self-determination, managers can help facilitate adaptive employee organizational behaviors while decreasing turnover intention (Richer, Blanchard, & Vallerand, 2002 ).

Core self-evaluation (CSE) theory is a relatively new concept that relates to self-confidence in general, such that people with higher CSE tend to be more committed to goals (Bono & Colbert, 2005 ). These core self-evaluations also extend to interpersonal relationships, as well as employee creativity. Employees with higher CSE are more likely to trust coworkers, which may also contribute to increased motivation for goal attainment (Johnson, Kristof-Brown, van Vianen, de Pater, & Klein, 2003 ). In general, employees with positive CSE tend to be more intrinsically motivated, thus additionally playing a role in increasing employee creativity (Judge, Bono, Erez, & Locke, 2005 ). Finally, according to research by Amabile ( 1996 ), intrinsic motivation or self-determined goal attainment is critical in facilitating employee creativity.

Goal-Setting and Conservation of Resources