- Schools & departments

Critical thinking

Advice and resources to help you develop your critical voice.

Developing critical thinking skills is essential to your success at University and beyond. We all need to be critical thinkers to help us navigate our way through an information-rich world.

Whatever your discipline, you will engage with a wide variety of sources of information and evidence. You will develop the skills to make judgements about this evidence to form your own views and to present your views clearly.

One of the most common types of feedback received by students is that their work is ‘too descriptive’. This usually means that they have just stated what others have said and have not reflected critically on the material. They have not evaluated the evidence and constructed an argument.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the art of making clear, reasoned judgements based on interpreting, understanding, applying and synthesising evidence gathered from observation, reading and experimentation. Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2016) Essential Study Skills: The Complete Guide to Success at University (4th ed.) London: SAGE, p94.

Being critical does not just mean finding fault. It means assessing evidence from a variety of sources and making reasoned conclusions. As a result of your analysis you may decide that a particular piece of evidence is not robust, or that you disagree with the conclusion, but you should be able to state why you have come to this view and incorporate this into a bigger picture of the literature.

Being critical goes beyond describing what you have heard in lectures or what you have read. It involves synthesising, analysing and evaluating what you have learned to develop your own argument or position.

Critical thinking is important in all subjects and disciplines – in science and engineering, as well as the arts and humanities. The types of evidence used to develop arguments may be very different but the processes and techniques are similar. Critical thinking is required for both undergraduate and postgraduate levels of study.

What, where, when, who, why, how?

Purposeful reading can help with critical thinking because it encourages you to read actively rather than passively. When you read, ask yourself questions about what you are reading and make notes to record your views. Ask questions like:

- What is the main point of this paper/ article/ paragraph/ report/ blog?

- Who wrote it?

- Why was it written?

- When was it written?

- Has the context changed since it was written?

- Is the evidence presented robust?

- How did the authors come to their conclusions?

- Do you agree with the conclusions?

- What does this add to our knowledge?

- Why is it useful?

Our web page covering Reading at university includes a handout to help you develop your own critical reading form and a suggested reading notes record sheet. These resources will help you record your thoughts after you read, which will help you to construct your argument.

Reading at university

Developing an argument

Being a university student is about learning how to think, not what to think. Critical thinking shapes your own values and attitudes through a process of deliberating, debating and persuasion. Through developing your critical thinking you can move on from simply disagreeing to constructively assessing alternatives by building on doubts.

There are several key stages involved in developing your ideas and constructing an argument. You might like to use a form to help you think about the features of critical thinking and to break down the stages of developing your argument.

Features of critical thinking (pdf)

Features of critical thinking (Word rtf)

Our webpage on Academic writing includes a useful handout ‘Building an argument as you go’.

Academic writing

You should also consider the language you will use to introduce a range of viewpoints and to evaluate the various sources of evidence. This will help your reader to follow your argument. To get you started, the University of Manchester's Academic Phrasebank has a useful section on Being Critical.

Academic Phrasebank

Developing your critical thinking

Set yourself some tasks to help develop your critical thinking skills. Discuss material presented in lectures or from resource lists with your peers. Set up a critical reading group or use an online discussion forum. Think about a point you would like to make during discussions in tutorials and be prepared to back up your argument with evidence.

For more suggestions:

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (pdf)

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (Word rtf)

Published guides

For further advice and more detailed resources please see the Critical Thinking section of our list of published Study skills guides.

Study skills guides

This article was published on 2024-02-26

University of Tasmania, Australia

Courses & units, critical thinking for postgraduate studies xpd503, introduction.

The aim of this unit is to help you understand critical thinking as a ‘habit of mind’ and to develop and apply advanced critical thinking knowledge and skills to complex issues meeting the academic requirements of postgraduate studies. The Unit establishes the grounds for thinking critically and exploring what contextual thinking means; and it (ii) encourages you to think about and discuss concepts and ideas in a critical fashion, which includes demonstrating appreciation of the times and places in which those concepts and ideas originated, what their purpose was, and how subsequently they have been and are employed. This unit will also develop your skills in working independently and collaboratively and with well-developed judgements through the application of advanced academic knowledge and skills to authentic, complex and higher-level topics.

Availability

Please check that your computer meets the minimum System Requirements if you are attending via Distance/Off-Campus.

Units are offered in attending mode unless otherwise indicated (that is attendance is required at the campus identified). A unit identified as offered by distance, that is there is no requirement for attendance, is identified with a nominal enrolment campus. A unit offered to both attending students and by distance from the same campus is identified as having both modes of study.

* The Final WW Date is the final date from which you can withdraw from the unit without academic penalty, however you will still incur a financial liability (refer to How do I withdraw from a unit? for more information).

Unit census dates currently displaying for 2024 are indicative and subject to change. Finalised census dates for 2024 will be available from the 1st October 2023. Note census date cutoff is 11.59pm AEST (AEDT during October to March).

About Census Dates

Learning Outcomes

- Discuss and evaluate the significance of critical and contextual thinking for postgraduate level studies, reflecting on own strengths, weaknesses and approaches to critical thinking;

- Apply advanced knowledge and skills in critical thinking to postgraduate level studies;

- Develop advanced skills in critically considering and analyzing high level and complex issues/problems;

- Generate sophisticated conclusions and solutions taking into account alternatives and different perspectives.

Fee Information

1 Please refer to more information on student contribution amounts . 2 Please refer to more information on eligibility and Approved Pathway courses . 3 Please refer to more information on eligibility for HECS-HELP . 4 Please refer to more information on eligibility for FEE-HELP .

If you have any questions in relation to the fees, please contact UConnect or more information is available on StudyAssist .

Please note: international students should refer to What is an indicative Fee? to get an indicative course cost.

The University reserves the right to amend or remove courses and unit availabilities, as appropriate.

Critical Thinking Skills for Postgraduate Study Essay

Critical thinking has recently gained increased importance as the skill that encourages personal, academic, and professional development. The ability to question the nature of an observed phenomenon, the feasibility of a particular statement, and credibility of a certain piece of information are instrumental to the efficacy of one’s communication. 1 However, to be able to explore a certain area and converse with others effectively, critical thinking is not enough, In addition to the ability to discern between the sensible and the nonsensical, one also needs the skill of providing a unique argument. 2 Put differently, the presence of creative thinking is inseparable from the phenomenon of critical thinking.

It could be argued that the ability to think critically is a separate skill that cannot serve as the starting point for acquiring other abilities, such as creativity. However, the specified assumption seems to be quite far from the truth. 3 While there is no direct link between being critical and creative, the former helps develop a good understanding of how a good discourse is structured and worded. 4 As a result, one can build a bare minimum of skills needed to produce a coherent and creative statement.

Nevertheless, critical thinking should not be regarded as the notion that is entirely inseparable from creativity. Creative thinking also implies that one is capable to transform a particular viewpoint and discover new ways of viewing a situation. 5 Thus, critical thinking skills can be seen as an essential tool for a postgraduate student, yet it is only one constituent of a much larger entity. 6 Creative thinking is also not to be dismissed as one of the essential elements of a postgraduate skill set. When combined, creativity and critical thinking become the pillars for creating a coherent approach toward locating available information and processing it to produce an innovative approach.

Bibliography

Bista, KKK., Exploring the Social and Academic Experiences of International Students in Higher Education Institutions , IGI Global, New York, NY, 2016.

Davies, M., and Barnett, R., The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , Springer, New York, NY, 2015.

Legg, M., et al., Academic English: Skills for Success , 2nd ed., Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, 2014.

National Academies of Sciences, Indicators for Monitoring Undergraduate STEM Education , National Academies Press, 2018.

Scheg, S. A., Implementation and Critical Assessment of the Flipped Classroom Experience , IGI Global, New York, NY, 2015.

Wisdom, S., Handbook of Research on Advancing Critical Thinking in Higher Education , IGI Global, New York, NY, 2015.

- National Academies of Sciences, Indicators for Monitoring Undergraduate STEM Education , National Academies Press, 2018, p. 63.

- S. Wisdom, Handbook of Research on Advancing Critical Thinking in Higher Education , IGI Global, New York, NY, 2015, p. 127.

- S. A. Scheg, Implementation and Critical Assessment of the Flipped Classroom Experience , IGI Global, New York, NY, 2015, p. 26.

- M. Legg et al., Academic English: Skills for Success, 2nd ed., Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, 2014, p. 22.

- K. Bista, Exploring the Social and Academic Experiences of International Students in Higher Education Institutions , IGI Global, New York, NY, 2016, p. 293.

- M. Davies and R. Barnett, The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , Springer, New York, NY, 2015, p. 292.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 15). Critical Thinking Skills for Postgraduate Study. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-thinking-skills-for-postgraduate-study/

"Critical Thinking Skills for Postgraduate Study." IvyPanda , 15 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/critical-thinking-skills-for-postgraduate-study/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Critical Thinking Skills for Postgraduate Study'. 15 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Critical Thinking Skills for Postgraduate Study." May 15, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-thinking-skills-for-postgraduate-study/.

1. IvyPanda . "Critical Thinking Skills for Postgraduate Study." May 15, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-thinking-skills-for-postgraduate-study/.

IvyPanda . "Critical Thinking Skills for Postgraduate Study." May 15, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-thinking-skills-for-postgraduate-study/.

- Master Degree in Accounting

- Dual Role of Clinical and Administrative Supervision

- How to Get Communication Skills for Medical Doctors?

- Multiple Intelligences and Interest Inventory

- Core Business Concepts of Bizcafe Simulation: How to Win?

- Six-Step Problem Solving Process

- Child's Development From Birth to High School

- Critical Thinking Development in Students

Welcome to Student Learning Te Taiako

Critical thinking.

Critical thinking is an important everyday skill. It is even more important at postgraduate level.

Critical thinking involves interpreting the viewpoints of others, as well as being able to express your own opinion. Agoos (2016), in the TED-Ed video below describes a five-step process:

- Formulate your question

- Gather your information

- Apply the information

- Consider the implications

- Explore the other points of view.

Student Learning offers a three-week practical workshop for postgraduate students. You will need to register for this.

If you miss these workshops have look at our handout on how to Write a Critique pdf 488KB .

You can also make a one-to-one appointment with the Postgraduate Learning Adviser to discuss ways to develop your critical thinking skills.

- pdf 234.3KB Writing a critique

The power of critical thinking in the modern graduate

“Economists who have studied the relationship between education and economic growth confirm what common sense suggests: the number of college degrees is not nearly as important as how well students develop cognitive skills, such as critical thinking and problem-solving ability.” – Derek Bok

In today’s fast-paced business environment, paper qualifications are simply not enough. Employers are looking for something extra because the problems they face demand it. That’s why the need for “critical thinking” skills appear so often, everywhere from job advertisements to business conferences to global forums. But what is critical thinking and why is it so indispensable today?

There are many definitions of “critical thinking”, but simply put, it is a process through which problems are identified and analysed so they may be solved in an effective and efficient manner. It means re-evaluating conventional and existing approaches to problems, seeing if they make sense, and applying changes if necessary. It’s the idea that problems are insurmountable only if we fail to think outside of the box.

Pic: University of Western Australia

Critical thinking can be broken into six stages. The first stage is to observe . This involves determining what information is available, and through what means. Then information is gathered for the next stage – analyse . That’s when you arrange the information into digestible themes and arguments.

Next, you evaluate what you have – you separate fact from opinion, and you decide what’s important and what’s not. After all, information is useless if you don’t establish some priorities – first and foremost, ask yourself if what you’ve gathered answers your core question. For example, how can I reduce costs without harming productivity?

Following this, you question your assumptions – are there better alternatives to your approach or better explanations of the issue? Be sure to contextualize the information you’re dealing with, considering everything from culture to politics and ethics. For example, if you’re launching a marketing campaign, have you considered how locals would react to a translated slogan or catch phrase? Finally, you come to the reflection stage – that’s when you put your plan to the test, making changes and learning as you take stock of the outcome.

But critical thinking is more than just a theoretical concept. It can be the difference between a stagnant career and a fruitful professional life. Because so many people have bachelor’s and master’s degrees these days, displaying a strong streak in critical thinking will allow you to stand out from your peers. Showing that you’ve solved problems for previous employers strengthens your hand when applying for new jobs. Suggesting opportunities and solutions to your boss will help when negotiating for higher pay.

Pic: University of Auckland

These days, giving presentations and selling ideas to clients and bosses are not infrequent duties, but part of the job description. While those may be intimidating activities, those with the ability to think critically should be able to undertake them with ease. That person will be able to field difficult questions from clients and superiors, and converse intelligently with them, lessening any chance of embarrassment and making strong, positive impressions on the people that really matter in your career.

Because the business environment is frequently fluid and decisions must be made quickly, critical thinking is essential in avoiding costly mistakes and groupthink. One must be able to consider every aspect of a business plan, marketing campaign, or research project, and plan for contingencies. As it is often said, if you fail to plan, you plan to fail. Things don’t always go according to plan, but if you’re able to quickly pivot away from disaster, you’ll always be valued by employers.

Critical thinking is also the key driver behind all innovation, and is extremely useful when confronting the two great monsters that plague every decision-maker in every industry – costs and time. If you can find a way to achieve objectives even while using less resources and/or time, you’ll be the darling of every manager and client you meet. But you won’t get there unless you think differently and think critically – unless you consider all the alternatives no matter improbable.

Pic: Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Because of all the reasons listed above, universities have poured much time and effort into incorporating critical thinking lessons into their curricula. While traditionally associated with the humanities and social sciences, critical thinking is now a cornerstone of most academic programs – whether undergraduate or postgraduate – from business to marketing to engineering.

Read on to find out more about 10 universities that prioritize instilling the power of critical thinking in their graduates:

UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA – AUSTRALIA The University of Western Australia (UWA) is what you get when you merge top-tier academics and a supportive environment which emphasizes critical thinking as well as personal growth. A proud member of the Group of Eight, which consists of Australia’s most respected universities, UWA’s academic prestige has been repeatedly recognized by independent organizations. For example, QS World University Rankings 2015/16 named it among the top 100 universities in the world.

As a research-intensive institution, UWA has shown exceptional affinity with the Arts , and it has been rated with 5 Stars for teaching quality and overall satisfaction by The Good Universities Guide 2016 for Humanities and Social Sciences. They have also ranked between 51 – 100 in the QS Rankings for Anthropology, Archaeology, English Language And Literature And Performing Arts.

The Faculty of Arts has an inspiring history of highly successful graduates and outstanding research results, which have made a valuable contribution to Western Australia, Australia and internationally. They have more than 3000 students studying a range of undergraduate and postgraduate courses through the School of Humanities, Music and Social Sciences. The Faculty provides a culture of international excellence in research, teaching and learning.

THE HONG KONG POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY – HONG KONG The Hong Kong Polytechnic University places a strong emphasis on opening the minds of its students. Its highly regarded Faculty of Humanities specializes in offering a broad array of language and cultural programs including the Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in Chinese and Bilingual Studies , and the Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in English Studies for the Professions . Through these programs and more, students will have the opportunity to immerse themselves in different languages and cultures while utilizing their critical thinking skills in intercultural and corporate contexts.

Advanced students may also pursue their PhD studies (via the Hong Kong PhD Fellowship Scheme ) as well as a professional doctoral program, namely the Doctor of Applied Language Sciences . Furthermore, students are able to explore the Chinese culture, history and philosophy through other postgraduate programs in its Department of Chinese Culture, allowing them to enhance their critical thinking with a strong, cultural dimension.

UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND – NEW ZEALAND The University of Auckland holds the distinction of being the highest ranked university in New Zealand – 82nd in the QS World University Rankings 2015/16. With a student population of 42,000 – including 6,000 international students from over 110 countries – it is also the largest. Offering more than 130 postgraduate programmes across eight faculties and two large-scale research institutes, it is easily New Zealand’s most comprehensive institution of higher learning. While students are free to choose from a vast array of course offerings, the university particularly excels at teaching accounting and finance, education, psychology, law, and English language and literature.

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY – UNITED STATES The Johns Hopkins University (JHU) is undoubtedly one of the United States’ best universities, consistently appearing near the top of the major rankings – 16th in the QS World University Rankings 2015/16. As America’s first research university , it has a long and rich history in encouraging critical thought and pioneering innovation. It is no surprise that it has attracted the best and the brightest – 36 Hopkins researchers in the past and present have earned Nobel Prizes. The university’s medical and nursing schools are particularly well regarded, as its affiliated teaching hospital, which is one of the best known hospitals in the country.

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL – UNITED STATES The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) is one of the finest public universities in the United States – the U.S. News & World Report ranked it 5th among public schools in the country. Founded in 1789, the university is famous for being a ‘Public Ivy’ school, offering an Ivy League academic environment for a public schooling price. Spanning 14 schools and the College of Arts and Sciences, UNC offers outstanding teaching and research based on critical and creative thinking. As one of the country’s premier schools, it is well-respected for its studies in public health , business , and journalism .

UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK – UNITED KINGDOM The University of Warwick is among the most prestigious and highly selective universities in the world. Multiple rankings place it within the top 10 best universities in the U.K. – typically 6th or 7th place. Due to this, Warwick graduates are always in demand with employers, and they do well both in industry and academia. Located in Coventry, England, the university is renowned for its outstanding aptitude for research and innovation – the perfect breeding ground for critical thinking. The university is also famously diverse – about a third of its 23,000-strong student body come from abroad, representing more than 120 countries.

Pic: University of Warwick

UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH – UNITED KINGDOM Being the sixth oldest university in the English-speaking world, the University of Edinburgh has a long and illustrious history which spans centuries. Founded in 1582, it consistently ranks among the world’s and the United Kingdom’s top universities – 21st in the QS World University Rankings 2015/16. It is a member of the Russell Group of universities – a distinction it shares with its cousins Cambridge and Oxford. Edinburgh has received plaudits for the research done by its cutting-edge Computer Science and Informatics department. Also, world-class teaching in the arts and humanities have solidified the university’s a reputation as a center of critical thinking.

NANYANG TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY – SINGAPORE Students looking for top-notch education in Asia should look no further than the Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Young by global standards, the university consistently punches above its weight – 13th in the QS World University Rankings 2015/16 and 2nd best in Asia by the same ranking. Adhering to rigorous academic standards and drawing expert-level staff from 80 countries, NTU is famous for producing quality, world-class graduates in engineering, business, science, the arts and humanities, and the social sciences. NTU is particularly known for its business school ( The Nanyang Business School ) which has been consistently ranked as the best in Singapore by the Economist.

UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY – AUSTRALIA The University of Sydney is Australia’s first university and unsurprisingly still among its most prestigious. It is ranked 45th in the QS World University Rankings 2015/16, its academic prowess led by its outstanding performance in the arts and humanities . The university also produces top graduates in the fields of Life Sciences and Medicine as well as Social Sciences and Management. Sydney boasts a total of 16 faculties, running the gamut of fields from agriculture to engineering to law to music. The university is also the site of intense and never-ending research, putting critical thinking and innovation at the forefront of their efforts.

Pic: University of Melbourne

UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE – AUSTRALIA The University of Melbourne is one of Australia’s best universities, or simply the best by at least one measure – the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2015-2016 ranked it the top university the country. Located in cosmopolitan Melbourne, it is Australia’s second oldest university, having being founded in 1853. Over the years, it has grown into a bustling institution of learning and research, with over 47,000 students and 22 discipline-specific faculties. Its education , law , and business programs are long recognized as among the finest in the world. The university’s prestige has not gone unnoticed by employers – the university is ranked 18th in the world for graduate employability by the QS World University Rankings 2015/16.

Popular stories

How to improve social skills: 11 top tips from the world’s most successful introverts.

Free or little-to-no charge: The countries with the best healthcare benefits for international students

The road to residency: Easiest countries for international students to get PR

May the Fourth be with you: Best Yoda quotes to get you through university

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Postgraduate Study

Douglas Eacersall; Moria Drake; and Allison Millward

INTRODUCTION

Postgraduate study is further education that follows the completion of an undergraduate degree. As an undergraduate student, graduation can seem a long way away, and often the goal is to complete your degree and move straight into employment. It is important, however, to consider postgraduate study options and how these might align with your future goals. Postgraduate study is an opportunity to delve deeper into a specific field of interest, expand your knowledge, develop specialised skills, and open doors to additional employment prospects. From traditional disciplines such as business, engineering, and the humanities, to emerging areas like artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and biomedical sciences, postgraduate study caters to a diverse range of academic pursuits. This chapter begins by outlining postgraduate study in Australia and the benefits of furthering your education through a postgraduate program, including increased professional skills, employment opportunities and personal growth. Following this, the different postgraduate study options are explained and the various pathways into postgraduate study are described. The chapter concludes by discussing study load, and finances and scholarships. This chapter provides you with the information to consider and plan for future postgraduate study.

POSTGRADUATE STUDY IN AUSTRALIA

The postgraduate experience focuses on the practical and theoretical application of knowledge either through coursework or research. This often enables students to engage in research projects, collaborate with industry partners, and contribute to meaningful discoveries that have real-world impact. As a postgraduate student, you can expect to benefit from university facilities, well-equipped laboratories, and advanced technology that facilitate a dynamic learning environment. The multicultural nature of Australian society enriches the study experience. You will have the chance to interact with fellow students from around the world, exchange ideas, and gain valuable insights into different cultures and perspectives. This diversity fosters a global outlook and prepares you for an interconnected world where collaboration and cross-cultural understanding are highly valued.

BENEFITS OF POSTGRADUATE STUDY

Undertaking postgraduate education is an exciting endeavour that can lead to many different positive outcomes. It can advance your career; grow your earning potential, knowledge, and expertise; develop higher level thinking, writing and research skills; and provide networking opportunities with like-minded individuals that are invaluable for personal and professional life. The benefits of postgraduate education are especially evident in the development of professional skills, increased employment options, and personal growth.

Professional skills

Students who pursue a postgraduate degree, graduate with an important set of professional skills that will help them in their careers. When you pursue a postgraduate degree, you will be introduced to the skillset of those who practice the profession. For example, a postgraduate degree in journalism will expose you to faculty staff who have newsroom experience, technology within the field, and lessons in press writing. A postgraduate degree in history will expose you to courses on archival and primary source research work – the core of the historian’s job. Students will also be exposed to the culture of the profession and its language or jargon. It is a great start to enculturating yourself in your field, especially if you lack prior professional experience.

Employment opportunities

A postgraduate qualification can result in additional career options and opportunities for promotion and greater career advancement. Postgraduate degrees build specialised expertise on a topic, leading to employment requiring levels of expertise that exceed those provided by an undergraduate degree. Working within a university is a common option for successful postgraduates, as the research-focus and service-focus of universities naturally lend themselves to the content students studied while in postgraduate education. Postgraduate study can also incorporate internships, industry placements, and networking opportunities, which can significantly enhance your employability upon graduation (see the chapter Preparing for Employment for more discussion). Postgraduate qualifications can result in promotions and new pathways in already-established careers, as the degree can prepare you to critically think, analyse, and lead.

Personal growth

As you progress through your study, you may find that career progression becomes less of the focus, and personal benefits and growth starts to take a front seat; you may note the benefits of increased self-confidence, problem-solving abilities and critical thinking skills (Neary, 2014). Motivations for study exist on a continuum and relate to life course and context (Swain & Hammond, 2011). Typically, while undertaking postgraduate study, it is important to keep this motivation in mind as it will serve as a driving force during the postgraduate journey. Pursuing a postgraduate qualification can build upon your perception of self, especially concerning the future employment pathways you wish to pursue. This is a primary motivator to start a postgraduate journey. Although the reason for engagement in postgraduate study may fluctuate, the result will likely still be further development of skills that can be used in your personal and professional life.

Postgraduate STUDY OPTIONS

Postgraduate study programs include, graduate certificates, graduate diplomas, masters’ degrees by coursework, masters’ degrees by research, and doctorates. The table below (see Table 26.1) compares the differences between undergraduate study and the different types of postgraduate study, in terms of degree type, structure and workload.

Graduate certificates are often the first step students can take towards postgraduate study. Typically, these qualifications take between four to five months of full-time study. Undertaking a graduate certificate program can be a good way to add to your resume or explore a new topic or passion.

Graduate diplomas fit the ideal middle-ground between a graduate certificate and a master’s degree program, taking about a year of full-time study. Diplomas cover the same course options as the graduate certificates but extend into further study. The offering can be similar to a master’s degree program without committing to a complete master’s degree.

The master’s degree comes in two distinct forms; a master’s degree by coursework and a master’s degree by research. Each type of master’s degree is designed to build upon existing knowledge and requires approximately two years of full-time study. Similar to undergraduate coursework, a master’s degree by coursework involves attending classes and completing course-based assessment items. A master’s degree by research can also include coursework but this will be limited as most of the program is focused on undertaking independent research and presenting the results as a research outcome. This outcome is usually a written thesis. A master’s degree by research is a good stepping-stone towards doctoral study.

A doctorate is the highest academic program achievement at university. Doctorates focus on developing significant, original research, typically taking three to four years of full-time study. The goal of a doctorate is to make an original and significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge in a specific field. It involves independent research, critical thinking, and the production of a substantial research output, usually a written thesis. It is a highly regarded degree and often required for academic and research employment at university, as well as for career advancement in certain fields. It represents the pinnacle of intellectual achievement and expertise in a chosen area of study.

COURSEWORK VERSUS RESEARCH

Both coursework and research postgraduate degree programs are designed to provide you with further opportunities to expand your knowledge, investigate issues within your field of study, and understand the important practical and theoretical underpinnings in your discipline.

The basics of postgraduate coursework

Although the two routes allow you to better understand your discipline, they have several key differences. Similar to undergraduate study, students studying a postgraduate degree by coursework achieve their degree by taking courses until they have met the number of required units for the degree. Depending on the institution, students undertaking a degree by coursework may be required to complete a final assessment that may include a comprehensive exam, practicum, project, or thesis. This is to test the content learned and the skillset necessary for a specific field.

In coursework, lecturers often serve as mentors guiding you on specific pathways or specialisations within a program. Relationships with lecturers are important during postgraduate study. Although the primary focus is for a lecturer to lead a course, in postgraduate coursework they often provide so much more in the form of guidance and assistance for you through the lifespan of your program. Indeed, sometimes in postgraduate coursework degrees, you may develop a mentor/mentee relationship with your lecturers who can later help you gain access to industry employment, postgraduate research degrees and other opportunities.

The basics of postgraduate research work

Although a postgraduate research degree may also contain courses, it is based on your success in producing a research outcome such as an independent thesis. Typically, these degrees include research master’s degrees and doctoral degrees. Research degrees are largely undertaken as independent study usually with assistance from at least two academic supervisors/advisors. The process of undertaking research includes sourcing these supervisors, proposing a research topic that will make an original and significant contribution to the field, designing a research methodology, working with your supervisors to plan and undertake the research, possibly producing research publications, and writing a thesis.

Undertaking research can be challenging (Brownlow et al., 2022), but this avenue of study offers a rewarding experience for those that choose to pursue it (Villanueva & Eacersall, forthcoming 2024). This is because research work allows you to contribute original knowledge to your field of study while learning and engaging in the research process. This prepares you for careers in academia, government work, consulting agencies, and the private sector. A research project commences with a student identifying an area within their field that they believe requires further investigation and crafting a proposal which presents a research question, identifies research goals, and establishes a research methodology. Both students at the master’s degree and doctoral levels (depending on program requirements) typically present their proposals at a Confirmation of Candidature seminar where they deliver their preliminary proposal to a panel of experts in the field (Bartlett & Eacersall, 2018). Many research projects require ethical approval to ensure that they are conducted in an ethical way. This is facilitated by the university ethics office and should be a supportive and collegial experience for student researchers (Hickey et al., 2021). Usually, Confirmation of Candidature and ethical approval will occur in the first third of the degree.

Because of the independent nature of the research degree, students need high-level organisational and communication skills. Indeed, communication is key for research students, as they are positioned at the intersection of their research teams, the university, and outside stakeholders. Research students must communicate with their supervisory teams in regard to meeting and drafting schedules. Further, research students need to prioritise their work. Since they are contributing a significant piece of research to their field, they may have to communicate with outside organisations such as labs, archives, and/or government offices to retrieve data or necessary supplies. Consequently, research students must be self-advocates, clearly explaining their needs. Finally, since each university has milestones for research degrees, students are expected to organise their time to meet these. In many instances, they must organise their research and writing schedule, but at a micro level, they must organise their daily research tasks so they can stay on track. The research study experience is an excellent way for students to hone these soft skills along with their content skills.

Coursework or research — How do I choose?

Both research and coursework postgraduate programs have immense benefits for an individual’s overall personal and professional growth. As you progress through your undergraduate degree program, you can plan for future postgraduate study by considering the following:

- What do you enjoy most about your undergraduate experience? Do you enjoy a more guided learning approach (coursework) or more self-directed opportunities to investigate solutions using theory, research, and/or knowledge-based results (research)?

- Do you desire structure and firm deadlines set by lecturers (coursework) or a more fluid structure (research)?

- Do you enjoy engaging with an existing body of knowledge to add to it (research) or applying it more directly to your own context (coursework)?

- Do you prefer, shorter projects and collaborative thinking (coursework), or do you prefer independent work, presenting research to a small community, and keeping up-to-date with scholarship in your field (research)?

Ultimately, as you explore different opportunities at university and answer these questions, you will be able to make a choice about the next steps in your academic journey.

PAthways to postgraduate study

There are several pathways into postgraduate education, and it is important to recognise that not everyone’s pathway is the same. Postgraduate study occurs after successful completion of an undergraduate degree, or sometimes after evaluation of experience through work. Some may decide to pursue further study immediately after completion of their undergraduate degree and others might start a postgraduate qualification after time in the workforce. It is useful for undergraduate students to be aware of the pathways to postgraduate education so that they better understand the potential opportunities open to them for further study (see the chapter Life after Graduation for more discussion of pathways).

The typical way to apply for entry into a postgraduate degree is to first decide which degree you are aiming for. The degree you choose can have a great impact on your postgraduate experience and your career. Earlier in this chapter we outlined the graduate certificate, graduate diploma, master’s degree by coursework, master’s degree by research, and doctorate. Knowing which level of degree you are applying for is a good first step. Next, is figuring out which discipline to focus on. There are going to be many to choose from, be it social sciences, engineering, education, arts, law, science, business, etc. Once you have decided on the degree and discipline, focusing on the entry dates and prerequisites is next. In Australia, each institution has their own method of segmenting their calendar year, some use two semesters per year, some a trimester model, others use a combination, or divide their study periods into smaller blocks. Be sure to check the entry dates with your institution.

Similar to entry windows, institutions will have differing entry requirements for each of the postgraduate degrees on offer. For undergraduate, in particular Australian school-leavers, this would have been a rank dependent on your performance in your secondary education, potentially accompanied by an interview, audition, or folio entry. Postgraduate study is similar, though differs slightly as these secondary school rankings are replaced by a grade point average (GPA) requirement, which is a reflection on your performance in undergraduate studies. For a master’s degree by research and doctorate level courses, prior experience undertaking research may also be a requirement. For example, it is common for doctoral level courses to require successful completion of an honours degree or a research master’s degree. Elements such as recognition of prior learning can also be considered under certain circumstances. Different universities will have different entry requirements and so, the best source of specific information will be the university you are interested in.

In addition, many universities offer flexible pathways once enrolled in a postgraduate course, often breaking courses down to allow students to stop and start at their own pace. There can also be options to exit a master’s program early, utilising the existing work for a graduate diploma qualification. The busy schedules of postgraduate students, especially those working and studying at the same time, have encouraged many institutions to adopt further flexibility. Again, investigating what individual institutions have on offer, is the best way to see what can fit you and your study needs.

For international students, Australian postgraduate programs are an attractive option for many academic disciplines, notably biology, engineering, chemistry, mathematics, social sciences, and the medical fields. It is important to note that each higher education institution has unique programs, entry requirements, costs, and culture. There are also issues for postgraduate international students to consider, including supervisory relationships, communication ability, and the benefits of positive engagement with the Australian community and culture (Brownlow et al., 2023). Doing thorough research and fact finding into your ideal institution and destination is vital to ensuring that you get the best possible postgraduate study experience. To study in Australia, you must apply for a student visa through the relevant Australian government department. For both domestic and international students, if you would like to know more about postgraduate study, reach out to your intended institution’s student support team. They are there to help you.

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Study load: can i work and study at the same time.

The question of whether to work while undertaking postgraduate studies plagues many students and is often one of the first questions they consider when deciding to pursue their degree. The answer is – it depends on the individual. The decision to work while undertaking postgraduate studies is often a personal, individual one that requires careful consideration. International students also need to consider the work conditions of their student visa. Working can be beneficial as it can reduce or negate any student debt you may need to take out. Working can also provide you with disposable income that scholarships, grants, and loans may not cover. For example, this income can be used for school supplies, personal/family emergencies, travel, and savings. If you are working in your field of study, you will be able to put into practice the content you are studying. Even if you are not working within your chosen field, students who work often bring many professional attributes to the classroom.

At the same time, working can present challenges. Students, especially in the first semester of postgraduate study, may struggle to balance work and studies, which may impact their results and their ability to make meaningful connections with peers and mentors. Similarly, if students undertake coursework programs, they may find it difficult to schedule work around their courses and vice versa. Research students, as well, may struggle to plan and begin their research journey while balancing work, as the research process can be intense initially. Although these may present struggles at first, you can use university resources to manage time and discuss this with specialist advisors and supervisors who can give you advice on managing work and studies. In all, working while studying hones postgraduate students’ organisational, time-management, and communication skills (see the chapters Goals and Priorities and Time Management for more discussion).

Finances and scholarships

For students considering postgraduate studies, finances for both their educational and personal expenses can be crucial, and students should consider how they will fund their studies as soon as they decide that they want to pursue a graduate degree. Luckily, there is aid available for those interested in pursuing a postgraduate degree. One of the major areas of financial support is scholarships. Scholarships are awards students receive for achievements like grades, their participation in extra-curricular activities, or social beliefs and activities. Scholarships can be external or internal. External means the scholarship is awarded by an organisation or industry other than your university, while internal is awarded by your university. Students should investigate scholarship opportunities by accessing resources on external scholarship websites as well as the university’s scholarship webpages. Some scholarships are based on the student’s research activities, so students should seek out possible opportunities through professional and student organisations. Australian domestic postgraduate students undertaking a Higher Degree by Research degree (most doctorates and research master’s) may be eligible to receive a Research Training Program place. This is a federal government scholarship that covers tuition fees for the stipulated duration of the degree.

There are many things to consider in relation to postgraduate study. These include the benefits of a postgraduate education, different types of postgraduate study, entry pathways, when to start, the differences between postgraduate coursework and postgraduate research, the expectations required of postgraduate students, and available resources to support your study. If you are in the early stages of your undergraduate degree, postgraduate study may seem like an option a long way off in the future. It is important, though, to be aware of postgraduate possibilities and the opportunities they offer. Careful consideration of this information, during undergraduate studies, can enable you to identify and plan successful pathways into postgraduate study.

- Postgraduate study occurs after successful completion of undergraduate study.

- The benefits of postgraduate study include increased employment opportunities, personal growth and professional skills.

- Postgraduate programs include graduate certificates, graduate diplomas, masters’ degrees by coursework, masters’ degrees by research, and doctorates.

- Postgraduate study can include coursework and/or research elements.

- Your undergraduate Grade Point Average (GPA) is important for entering postgraduate programs.

- For postgraduate research programs, your GPA and/or research experience may be part of the entry requirements.

- There are many supports to assist you with postgraduate study.

- During undergraduate study, consider the pathways and options for future postgraduate study.

Bartlett, C. L., & Eacersall, D. C. (2019). Confirmation of candidature: An autoethnographic reflection from the dual identities of student and research administrator. In T. M. Machin, M. Clara & P. A. Danaher (Eds.), Traversing the doctorate: Reflections and strategies from students, supervisors and administrators (pp. 29-56). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23731-8_3

Brownlow, C., Eacersall, D., Martin, N., & Parsons-Smith, R. (2023). The higher degree research student experience in Australian universities: A systematic literature review, Higher Education Research & Development , 42 (7), 1608-1623. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2023.2183939

Brownlow, C., Eacersall, D., Nelson, C. W., Parsons-Smith, R. L., & Terry, P. C. (2022). Risks to mental health of higher degree by research (HDR) students during a global pandemic. PLoS ONE , 17 (12), e0279698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279698

Hickey, A., Davis, S., Farmer, W., Dawidowicz, J., Moloney, C., Lamont-Mills, A., Carniel, J., Pillay, Y., Akenson, D., Brömdal, A., Gehrmann, R., Mills, D., Kolbe-Alexander, T., Machin, T., Reich, S., Southey, K., Crowley-Cyr, L., Watanabe, T., Davenport, J., …Eacersall, D., & Maxwell, J. (2021). Beyond criticism of ethics review boards: Strategies for engaging research communities and enhancing ethical review processes. Journal of Academic Ethics, 20, 549-567 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09430-4

Neary, S. (2014). Reclaiming professional identity through postgraduate professional development: Careers practitioners reclaiming their professional selves. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling , 42 (2), 199-210.

Swain, J., & Hammond, C. (2011). The motivations and outcomes of studying for part-time mature students in higher education. International Journal of Lifelong Education , 30 (5), 591-612.

Villanueva, J. A. R., & Eacersall, D. (forthcoming, 2024). Autoethnographic reflections on a research journey: Dual perspectives from a doctoral student and a researcher development specialist . SpringerBriefs in Education, Springer Nature. https://link.springer.com/book/9789819949281

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge our colleagues, Wendy Hargreaves, Ben Ingram and Eddie Thangavelu, for their valuable advice and feedback on this chapter.

Academic Success Copyright © 2021 by Douglas Eacersall; Moria Drake; and Allison Millward is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Open access

- Published: 02 May 2024

Use of the International IFOMPT Cervical Framework to inform clinical reasoning in postgraduate level physiotherapy students: a qualitative study using think aloud methodology

- Katie L. Kowalski 1 ,

- Heather Gillis 1 ,

- Katherine Henning 1 ,

- Paul Parikh 1 ,

- Jackie Sadi 1 &

- Alison Rushton 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 486 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

240 Accesses

Metrics details

Vascular pathologies of the head and neck are rare but can present as musculoskeletal problems. The International Federation of Orthopedic Manipulative Physical Therapists (IFOMPT) Cervical Framework (Framework) aims to assist evidence-based clinical reasoning for safe assessment and management of the cervical spine considering potential for vascular pathology. Clinical reasoning is critical to physiotherapy, and developing high-level clinical reasoning is a priority for postgraduate (post-licensure) educational programs.

To explore the influence of the Framework on clinical reasoning processes in postgraduate physiotherapy students.

Qualitative case study design using think aloud methodology and interpretive description, informed by COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research. Participants were postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students who learned about the Framework through standardized delivery. Two cervical spine cases explored clinical reasoning processes. Coding and analysis of transcripts were guided by Elstein’s diagnostic reasoning components and the Postgraduate Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy Practice model. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis (inductive and deductive) for individuals and then across participants, enabling analysis of key steps in clinical reasoning processes and use of the Framework. Trustworthiness was enhanced with multiple strategies (e.g., second researcher challenged codes).

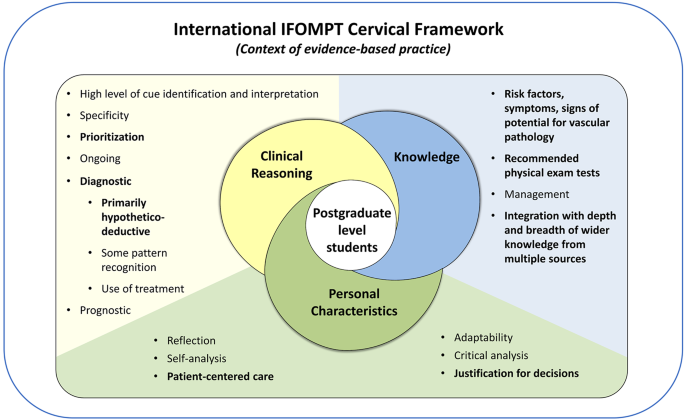

For all participants ( n = 8), the Framework supported clinical reasoning using primarily hypothetico-deductive processes. It informed vascular hypothesis generation in the patient history and testing the vascular hypothesis through patient history questions and selection of physical examination tests, to inform clarity and support for diagnosis and management. Most participant’s clinical reasoning processes were characterized by high-level features (e.g., prioritization), however there was a continuum of proficiency. Clinical reasoning processes were informed by deep knowledge of the Framework integrated with a breadth of wider knowledge and supported by a range of personal characteristics (e.g., reflection).

Conclusions

Findings support use of the Framework as an educational resource in postgraduate physiotherapy programs to inform clinical reasoning processes for safe and effective assessment and management of cervical spine presentations considering potential for vascular pathology. Individualized approaches may be required to support students, owing to a continuum of clinical reasoning proficiency. Future research is required to explore use of the Framework to inform clinical reasoning processes in learners at different levels.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Musculoskeletal neck pain and headache are highly prevalent and among the most disabling conditions globally that require effective rehabilitation [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. A range of rehabilitation professionals, including physiotherapists, assess and manage musculoskeletal neck pain and headache. Assessment of the cervical spine can be a complex process. Patients can present to physiotherapy with vascular pathology masquerading as musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction, as neck pain and/or headache as a common first symptom [ 5 ]. While vascular pathologies of the head and neck are rare [ 6 ], they are important considerations within a cervical spine assessment to facilitate the best possible patient outcomes [ 7 ]. The International IFOMPT (International Federation of Orthopedic Manipulative Physical Therapists) Cervical Framework (Framework) provides guidance in the assessment and management of the cervical spine region, considering the potential for vascular pathologies of the neck and head [ 8 ]. Two separate, but related, risks are considered: risk of misdiagnosis of an existing vascular pathology and risk of serious adverse event following musculoskeletal interventions [ 8 ].

The Framework is a consensus document iteratively developed through rigorous methods and the best contemporary evidence [ 8 ], and is also published as a Position Statement [ 7 ]. Central to the Framework are clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice, providing guidance in the assessment of the cervical spine region, considering the potential for vascular pathologies in advance of planned interventions [ 7 , 8 ]. The Framework was developed and published to be a resource for practicing musculoskeletal clinicians and educators. It has been implemented widely within IFOMPT postgraduate (post-licensure) educational programs, influencing curricula by enabling a comprehensive and systemic approach when considering the potential for vascular pathology [ 9 ]. Frequently reported curricula changes include an emphasis on the patient history and incorporating Framework recommended physical examination tests to evaluate a vascular hypothesis [ 9 ]. The Framework aims to assist musculoskeletal clinicians in their clinical reasoning processes, however no study has investigated students’ use of the Framework to inform their clinical reasoning.

Clinical reasoning is a critical component to physiotherapy practice as it is fundamental to assessment and diagnosis, enabling physiotherapists to provide safe and effective patient-centered care [ 10 ]. This is particularly important for postgraduate physiotherapy educational programs, where developing a high level of clinical reasoning is a priority for educational curricula [ 11 ] and critical for achieving advanced practice physiotherapy competency [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. At this level of physiotherapy, diagnostic reasoning is emphasized as an important component of a high level of clinical reasoning, informed by advanced use of domain-specific knowledge (e.g., propositional, experiential) and supported by a range of personal characteristics (e.g., adaptability, reflective) [ 12 ]. Facilitating the development of clinical reasoning improves physiotherapist’s performance and patient outcomes [ 16 ], underscoring the importance of clinical reasoning to physiotherapy practice. Understanding students’ use of the Framework to inform their clinical reasoning can support optimal implementation of the Framework within educational programs to facilitate safe and effective assessment and management of the cervical spine for patients.

To explore the influence of the Framework on the clinical reasoning processes in postgraduate level physiotherapy students.

Using a qualitative case study design, think aloud case analyses enabled exploration of clinical reasoning processes in postgraduate physiotherapy students. Case study design allows evaluation of experiences in practice, providing knowledge and accounts of practical actions in a specific context [ 17 ]. Case studies offer opportunity to generate situationally dependent understandings of accounts of clinical practice, highlighting the action and interaction that underscore the complexity of clinical decision-making in practice [ 17 ]. This study was informed by an interpretive description methodological approach with thematic analysis [ 18 , 19 ]. Interpretive description is coherent with mixed methods research and pragmatic orientations [ 20 , 21 ], and enables generation of evidence-based disciplinary knowledge and clinical understanding to inform practice [ 18 , 19 , 22 ]. Interpretive description has evolved for use in educational research to generate knowledge of educational experiences and the complexities of health care education to support achievement of educational objectives and professional practice standards [ 23 ]. The COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) informed the design and reporting of this study [ 24 ].

Research team

All research team members hold physiotherapy qualifications, and most hold advanced qualifications specializing in musculoskeletal physiotherapy. The research team is based in Canada and has varying levels of academic credentials (ranging from Clinical Masters to PhD or equivalent) and occupations (ranging from PhD student to Director of Physical Therapy). The final author (AR) is also an author of the Framework, which represents international and multiprofessional consensus. Authors HG and JS are lecturers on one of the postgraduate programs which students were recruited from. The primary researcher and first author (KK) is a US-trained Physical Therapist and Postdoctoral Research Associate investigating spinal pain and clinical reasoning in the School of Physical Therapy at Western University. Authors KK, KH and PP had no prior relationship with the postgraduate educational programs, students, or the Framework.

Study setting

Western University in London, Ontario, Canada offers a one-year Advanced Health Care Practice (AHCP) postgraduate IFOMPT-approved Comprehensive Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy program (CMP) and a postgraduate Sport and Exercise Medicine (SEM) program. Think aloud case analyses interviews were conducted using Zoom, a viable option for qualitative data collection and audio-video recording of interviews that enables participation for students who live in geographically dispersed areas across Canada [ 25 ]. Interviews with individual participants were conducted by one researcher (KK or KH) in a calm and quiet environment to minimize disruption to the process of thinking aloud [ 26 ].

Participants

AHCP postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students ≥ 18 years of age in the CMP and SEM programs were recruited via email and an introduction to the research study during class by KK, using purposive sampling to ensure theoretical representation. The purposive sample ensured key characteristics of participants were included, specifically gender, ethnicity, and physiotherapy experience (years, type). AHCP students must have attended standardized teaching about the Framework to be eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria included inability to communicate fluently in English. As think-aloud methodology seeks rich, in-depth data from a small sample [ 27 ], this study sought to recruit 8–10 AHCP students. This range was informed by prior think aloud literature and anticipated to balance diversity of participant characteristics, similarities in musculoskeletal physiotherapy domain knowledge and rich data supporting individual clinical reasoning processes [ 27 , 28 ].

Learning about the IFOMPT Cervical Framework

CMP and SEM programs included standardized teaching of the Framework to inform AHCP students’ clinical reasoning in practice. Delivery included a presentation explaining the Framework, access to the full Framework document [ 8 ], and discussion of its role to inform practice, including a case analysis of a cervical spine clinical presentation, by research team members AR and JS. The full Framework document that is publicly available through IFOMPT [ 8 ] was provided to AHCP students as the Framework Position Statement [ 7 ] was not yet published. Discussion and case analysis was led by AHCP program leads in November 2021 (CMP, including research team member JS) and January 2022 (SEM).

Think aloud case analyses data collection

Using think aloud methodology, the analytical processes of how participants use the Framework to inform clinical reasoning were explored in an interview with one research team member not involved in AHCP educational programs (KK or KH). The think aloud method enables description and explanation of complex information paralleling the clinical reasoning process and has been used previously in musculoskeletal physiotherapy [ 29 , 30 ]. It facilitates the generation of rich verbal [ 27 ]as participants verbalize their clinical reasoning protocols [ 27 , 31 ]. Participants were aware of the aim of the research study and the research team’s clinical and research backgrounds, supporting an open environment for depth of data collection [ 32 ]. There was no prior relationship between participants and research team members conducting interviews.

Participants were instructed to think aloud their analysis of two clinical cases, presented in random order (Supplementary 1 ). Case information was provided in stages to reflect the chronology of assessment of patients in practice (patient history, planning the physical examination, physical examination, treatment). Use of the Framework to inform clinical reasoning was discussed at each stage. The cases enabled participants to identify and discuss features of possible vascular pathology, treatment indications and contraindications/precautions, etc. Two research study team members (HG, PP) developed cases designed to facilitate and elicit clinical reasoning processes in neck and head pain presentations. Cases were tested against the research team to ensure face validity. Cases and think aloud prompts were piloted prior to use with three physiotherapists at varying levels of practice to ensure they were fit for purpose.

Data collection took place from March 30-August 15, 2022, during the final terms of the AHCP programs and an average of 5 months after standardized teaching about the Framework. During case analysis interviews, participants were instructed to constantly think aloud, and if a pause in verbalizations was sustained, they were reminded to “keep thinking aloud” [ 27 ]. As needed, prompts were given to elicit verbalization of participants’ reasoning processes, including use of the Framework to inform their clinical reasoning at each stage of case analysis (Supplementary 2 ). Aside from this, all interactions between participants and researchers minimized to not interfere with the participant’s thought processes [ 27 , 31 ]. When analysis of the first case was complete, the researcher provided the second case, each lasting 35–45 min. A break between cases was offered. During and after interviews, field notes were recorded about initial impressions of the data collection session and potential patterns appearing to emerge [ 33 ].

Data analysis

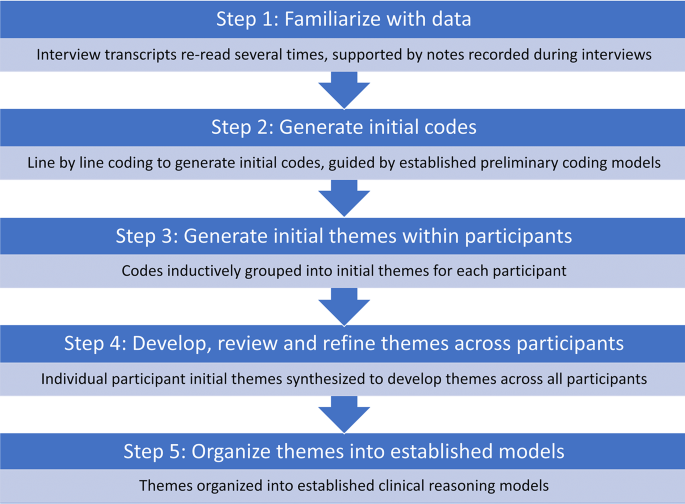

Data from think aloud interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis [ 30 , 34 ], facilitating identification and analysis of patterns in data and key steps in the clinical reasoning process, including use of the Framework to enable its characterization (Fig. 1 ). As established models of clinical reasoning exist, a hybrid approach to thematic analysis was employed, incorporating inductive and deductive processes [ 35 ], which proceeded according to 5 iterative steps: [ 34 ]

Data analysis steps

Familiarize with data: Audio-visual recordings were transcribed verbatim by a physiotherapist external to the research team. All transcripts were read and re-read several times by one researcher (KK), checking for accuracy by reviewing recordings as required. Field notes supported depth of familiarization with data.

Generate initial codes: Line-by-line coding of transcripts by one researcher (KK) supported generation of initial codes that represented components, patterns and meaning in clinical reasoning processes and use of the Framework. Established preliminary coding models were used as a guide. Elstein’s diagnostic reasoning model [ 36 ] guided generating initial codes of key steps in clinical reasoning processes (Table 1 a) [ 29 , 36 ]. Leveraging richness of data, further codes were generated guided by the Postgraduate Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy Practice model, which describes masters level clinical practice (Table 1 b) [ 12 ]. Codes were refined as data analysis proceeded. All codes were collated within participants along with supporting data.

Generate initial themes within participants: Coded data was inductively grouped into initial themes within each participant, reflecting individual clinical reasoning processes and use of the Framework. This inductive stage enabled a systematic, flexible approach to describe each participant’s unique thinking path, offering insight into the complexities of their clinical reasoning processes. It also provided a comprehensive understanding of the Framework informing clinical reasoning and a rich characterization of its components, aiding the development of robust, nuanced insights [ 35 , 37 , 38 ]. Initial themes were repeatedly revised to ensure they were grounded in and reflected raw data.

Develop, review and refine themes across participants: Initial themes were synthesized across participants to develop themes that represented all participants. Themes were reviewed and refined, returning to initial themes and codes at the individual participant level as needed.

Organize themes into established models: Themes were deductively organized into established clinical reasoning models; first into Elstein’s diagnostic reasoning model, second into the Postgraduate Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy Practice model to characterize themes within each diagnostic reasoning component [ 12 , 36 ].

Trustworthiness of findings

The research study was conducted according to an a priori protocol and additional steps were taken to establish trustworthiness of findings [ 39 ]. Field notes supported deep familiarization with data and served as a means of data source triangulation during analysis [ 40 ]. One researcher coded transcripts and a second researcher challenged codes, with codes and themes rigorously and iteratively reviewed and refined. Frequent debriefing sessions with the research team, reflexive discussions with other researchers and peer scrutiny of initial findings enabled wider perspectives and experiences to shape analysis and interpretation of findings. Several strategies were implemented to minimize the influence of prior relationships between participants and researchers, including author KK recruiting participants, KK and KH collecting/analyzing data, and AR, JS, HG and PP providing input on de-identified data at the stage of synthesis and interpretation.

Nine AHCP postgraduate level students were recruited and participated in data collection. One participant was withdrawn because of unfamiliarity with the standardized teaching session about use of the Framework (no recall of session), despite confirmation of attendance. Data from eight participants were used for analysis (CMP: n = 6; SEM: n = 2; Table 2 ), which achieved sample size requirements for think aloud methodology of rich and in-depth data [ 27 , 28 ].

Diagnostic reasoning components

Informed by the Framework, all components of Elstein’s diagnostic reasoning processes [ 36 ] were used by participants, including use of treatment with physiotherapy interventions to aid diagnostic reasoning. An illustrative example is presented in Supplement 3 . Clinical reasoning used primarily hypothetico-deductive processes reflecting a continuum of proficiency, was informed by deep Framework knowledge and breadth of prior knowledge (e.g., experiential), and supported by a range of personal characteristics (e.g., justification for decisions).

Cue acquisition

All participants sought to acquire additional cues early in the patient history, and for some this persisted into the medical history and physical examination. Cue acquisition enabled depth and breadth of understanding patient history information to generate hypotheses and factors contributing to the patient’s pain experience (Table 3 ). All participants asked further questions to understand details of the patients’ pain and their presentation, while some also explored the impact of pain on patient functioning and treatments received to date. There was a high degree of specificity to questions for most participants. Ongoing clinical reasoning processes through a thorough and complete assessment, even if the patient had previously received treatment for similar symptoms, was important for some participants. Cue acquisition was supported by personal characteristics including a patient-centered approach (e.g., understanding the patient’s beliefs about pain) and one participant reflected on their approach to acquiring patient history cues.

Hypothesis generation

Participants generated an average of 4.5 hypotheses per case (range: 2–8) and most hypotheses (77%) were generated rapidly early in the patient history. Knowledge from the Framework about patient history features of vascular pathology informed vascular hypothesis generation in the patient history for all participants in both cases (Table 4 ). Vascular hypotheses were also generated during the past medical history, where risk factors for vascular pathology were identified and interpreted by some participants who had high levels of suspicion for cervical articular involvement. Non-vascular hypotheses were generated during the physical examination by some participants to explain individual physical examination or patient history cues. Deep knowledge of the patient history section in the Framework supported high level of cue identification and interpretation for generating vascular hypotheses. Initial hypotheses were prioritized by some participants, however the level of specificity of hypotheses varied.

Cue evaluation

All participants evaluated cues throughout the patient history and physical examination in relationship to hypotheses generated, indicating use of hypothetico-deductive reasoning processes (Table 5 ). Framework knowledge of patient history features of vascular pathology was used to test vascular hypotheses and aid differential diagnosis. The patient history section supported high level of cue identification and interpretation of patient history features for all but one participant, and generation of further patient history questions for all participants. The level of specificity of these questions was high for all but one participant. Framework knowledge of recommended physical examination tests, including removal of positional testing, supported planning a focused and prioritized physical examination to further test vascular hypotheses for all participants. No participant indicated intention to use positional testing as part of their physical examination. Treatment with physiotherapy interventions served as a form of cue evaluation, and cues were evaluated to inform prognosis for some participants. At times during the physical examination, some participants demonstrated occasional errors or difficulty with cue evaluation by omitting key physical exam tests (e.g., no cranial nerve assessment despite concerns for trigeminal nerve involvement), selecting physical exam tests in advance of hypothesis generation (e.g., cervical spine instability testing), difficulty interpreting cues, or late selection of a physical examination test. Cue acquisition was supported by a range of personal characteristics. Most participants justified selection of physical examination tests, and some self-reflected on their ability to collect useful physical examination information to inform selection of tests. Precaution to the physical examination was identified by all participants but one, which contributed to an adaptable approach, prioritizing patient safety and comfort. Critical analysis of physical examination information aided interpretation within the context of the patient for most participants.

Hypothesis evaluation

All participants used the Framework to evaluate their hypotheses throughout the patient history and physical examination, continuously shifting their level of support for hypotheses (Table 6 , Supplement 4 ). This informed clarity in the overall level of suspicion for vascular pathology or musculoskeletal diagnoses, which were specific for most participants. Response to treatment with physiotherapy interventions served as a form of hypothesis evaluation for most participants who had low level suspicion for vascular pathology, highlighting ongoing reasoning processes. Hypotheses evaluated were prioritized by ranking according to level of suspicion by some participants. Difficulties weighing patient history and physical examination cues to inform judgement on overall level of suspicion for vascular pathology was demonstrated by some participants who reported that incomplete physical examination data and not being able to see the patient contributed to difficulties. Hypothesis evaluation was supported by the personal characteristic of reflection, where some students reflected on the Framework’s emphasis on the patient history to evaluate a vascular hypothesis.