- Advisory Board

- Publications

- Data & Tools

- News & Analysis

- Stepping Up

- Justice Reinvestment

- Reentry 2030

- Justice & Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP)

- More Projects

- Career Opportunities

- Partner With Us

- Stay Connected

Addressing Misconceptions about Mental Health and Violence

Despite public perception that there is a direct connection between mental health and violence, research shows that this relationship is complex and that the presence of a mental illness doesn’t automatically predispose a person to violent behavior. As criminal justice professionals work to protect public safety, it’s important that their policies and practices reflect accurate information, not common misperceptions. This brief addresses these misconceptions, presents important information about risk factors for violence, and offers ways that criminal justice professionals can help mitigate such risks.

Project Credits

About the author.

When incidents of violence occur, the public is sometimes quick to assume that the person (or people) involved has a mental illness. This can be for numerous reasons, but largely, it is that misconceptions about mental health and violence are often perpetuated in media and public discourse. In fact, despite prevailing beliefs about a direct connection between the two, research shows that the relationship between violence and mental illness is complex, and the presence of a mental illness does not automatically predispose a person to violent behavior. 1

As criminal justice professionals work to protect public safety, it is important that their policies and practices reflect accurate information, not common misperceptions. Additionally, they need to understand the real risk factors and warning signs of violence to minimize the risk of violence among the people they supervise or encounter. This brief addresses common misconceptions about the relationship between mental illness and violence, presents important information about risk factors for violence, and offers ways that criminal justice professionals can help mitigate these risks.

Dispelling Misconceptions

Many people are not familiar with the signs, symptoms, and effects of various mental illnesses, and therefore sometimes use mental illness as an explanation when seeking reasons for seemingly senseless acts of violence. The public also often does not understand the complex nature of the relationship between mental illness and violence. Below are three important facts people should know.

1. People with mental illnesses are not more likely to be violent than the general public.

The perception that people with mental illnesses are more prone to violence is based on the stigma surrounding mental illnesses and the ways in which researchers study this relationship. For example, most research on mental illness is conducted in inpatient treatment settings, but evidence indicates that people receiving inpatient treatment have a higher risk of violence than people in outpatient settings. 2

The National Council for Mental Wellbeing says that having a diagnosed mental illness is not, in the absence of other factors, a sufficient risk to warrant fear of mass violence. 3

2. People with mental illnesses are more likely to cause self-harm or be victims of violence than to inflict harm on others. 4

Serious mental illnesses (SMI) such as depression, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder may at times increase the risk of danger to oneself. 5

This can include suicidal ideation, parasuicidal behaviors, 6 and self-harm. However, there are no accurate data to support the belief that people with mental illnesses are more likely to be violent toward others. Indeed, research shows the opposite—people with mental illnesses account for only about 4 percent of violent crime in the United States. 7 When there is a direct relationship between people with SMI and violence, factors such as substance use 8 and environmental stressors, such as poverty and housing instability are associated with the connection. 9

3. Clinical assessments are not the most effective way to determine a person’s risk of violence.

Although clinical behavioral health practitioners have often been asked to determine the risk of violence a person with mental illness poses, research shows that clinicians’ judgment regarding risk is no better than chance. 10 Instead, the use of actuarial violence risk assessment tools are more accurate, and tools have been developed to determine risk for specific types of violence including sexual violence 11 and workplace violence. 12 It is also important to keep in mind that clinicians and violence risk assessment tools , like most people and tools used in the criminal justice system, have inherent biases, even when there are good intentions. Criminal justice professionals should receive implicit bias training even when using violence risk assessment tools to mitigate some of these concerns.

Risk factors for violence

While people with mental illnesses are not predisposed to violent behavior, criminal justice professionals should still understand key risk factors for violence. These factors include:

Prior history of violent behavior

Previous acts of violence can be a risk factor for future violence, especially if other risk factors were and are present.13

Times of crisis

During times of crisis, anyone can be at an increased risk for acting out violently because they may have a lower tolerance for frustrations when stressed. For some people, this tolerance can drop so low that they are less able to control their behaviors. It is important to distinguish between a diagnosable mental illness and someone with mental health needs, however.14 For example, if someone is experiencing a time of stress, trauma, or crisis, such as being fired from a job, the breakdown of a relationship, or the loss of a loved one, it can be a risk factor for violence regardless of whether they have been diagnosed with a mental illness.15

Command auditory hallucinations

When someone is experiencing auditory hallucinations telling them to act in violence, this is considered a risk because they may follow the command.16 This may be especially true if the person has a history of acting on these types of commands. Increased stress may make this risk even more acute.

Substance use

Substance use can be a stand-alone risk factor or increase other risk factors for violence, especially co-occurring substance use and mental illness.17 Intoxication by some substances can increase the risk for violence, especially stimulants.18 Agitation, due to withdrawal or intoxication, is a sign someone should be assessed for risk of violence.

Mitigating Risks of Violence: Practical Steps

1. understand the research. .

Becoming familiar with the research and data on the relationship between mental illness and violence—as well as the general causes and risk factors for violent behavior—can help criminal justice professionals recognize warning signs and avoid misconceptions and biases. Understanding the research can also help agencies choose the most appropriate actuarial violence risk assessment tool, as well as help focus resources on people at highest risk for becoming violent based on the chosen assessment instrument.

2. Provide ongoing training.

Staff who may encounter people at risk of committing violence should be trained on recognizing risk factors and intervention methods, like de-escalation techniques. They should also receive implicit bias training and education on stereotypes so that they do not assume a person is dangerous simply because of a mental illness. This is especially important for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) with mental illnesses, who can be seen as intimidating to some staff due to premature judgments, limited personal experiences, or prejudices.

3. Leverage community resources and their clinical expertise.

Criminal justice professionals should partner with local behavioral health treatment providers and access resources that can help them recognize people who are at risk to act violently. This can also help facilitate referrals when people are experiencing a mental health crisis. As partners, clinicians may be able to provide trainings to criminal justice staff on ways to identify signs and symptoms of risk. This partnership can also help make criminal justice staff aware of all the mental health resources that exist in their community, such as diversion programs, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) Teams, or as a last resort, civil commitment .

The Council of State Governments Justice Center offers free in-depth subject matter expertise and can connect you to jurisdictions that are supporting people with serious mental illness to help them avoid violent behavior. Visit the Center for Justice and Mental Health Partnerships to learn more.

Additional Resources

Mass Violence in America: Causes, Impacts, and Solutions by National Council for Mental Wellbeing

Understanding and Managing Risks for People with Behavioral Health Needs by The Council of State Governments Justice Center

1 Seena Fazel et al., “Schizophrenia and Violence: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” PLOS Medicine 6, no. 8 (2009).

2 Solveig Osborg Ose et al., “Risk of Violence Among Patients in Psychiatric Treatment: Results from a National Census,” Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 71, no. 8 (2017): 551.

3 Note that the National Council for Mental Wellbeing defines an act of mass violence as an event in which four or more people are killed. See National Council for Mental Wellbeing, Mass Violence in America Executive Summary (Washington, DC: National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2019), v.

4 Jeanne Y Choe et al., “Perpetration of Violence, Violent Victimization, and Severe Mental Illness: Balancing Public Health Concerns,” Psychiatric Services 59, no. 2 (2008): 153–64; Kimberlie Dean et al., “Risk of Being Subjected to Crime, Including Violent Crime, After Onset of Mental Illness: A Danish National Registry Study Using Police Data,” JAMA Psychiatry 75, no. 7 (2018): 689–696.

5 “Mental Illness and Suicide,” Suicide Awareness Voices of Education, accessed August 18, 2021 .

6 Virpi Leppanen et al., “Association of Parasuicidal Behavior to Early Maladaptive Schemas and Schema Modes in Patients with BPD: The Oulu BPD Study,” Personality and Mental Health 10 (2016): 61.

7 “This means that even if all of the association between mental illness and violence could somehow be eliminated, we would still have to confront 96 percent of the violence in the United States.” See John S. Rozel and Edward P. Mulvey, “The Link Between Mental Illness and Firearm Violence: Implications for Social Policy and Clinical Practice,” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 13, (2017): 445–69.

8 Seena Fazel et al., “Schizophrenia and Violence: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” PLOS Medicine 6, no. 8 (2009); Because substance use disorder is a criminogenic risk factor, which increases the likelihood someone will commit another crime, a high criminogenic risk level may increase the risk of violent crime. See also Fred Osher et al., Adults with Behavioral Health Needs Under Correctional Supervision: A Shared Framework for Reducing Recidivism and Promoting Recovery (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2012) .

9 Eric B. Elbogen and Sally C. Johnson, “The Intricate Link Between Violence and Mental Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions,” Arch Gen Psychiatry 66, no. 2 (2009): 152–161.

10 Claudia C. Hurducas et al., “Violence Risk Assessment Tools: A Systematic Review of Surveys,” International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 13, no. 3 (2014): 182 ; J. Monahan, The Clinical Prediction of Violent Behavior: An Assessment of Clinical Techniques (Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson, 1981).

12 Dr. J. Reid Meloy, Dr. Stephen G. White, and Dr. Stephen Hart, “Workplace Assessment of Targeted Violence Risk: The Development and Reliability of the WAVR-21,” Journal of Forensic Sciences 58, no. 5 (2013): 1353.

13 Mairead Dolan and Regine Blattner, “The Utility of the Historical Clinical Risk-20 Scale as a Predictor of Outcomes in Decisions to Transfer Patients from High to Lower Levels of Security –A UK Perspective,” BMC Psychiatry 10, no. 76 .

14 In times of transition or stress, many people may experience some mental health needs that don’t rise to the level of a diagnosable mental illness. They may benefit from behavioral health supports like talk therapy or skill-building exercises to strengthen coping skills. See American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

15 In one study of 28 acts of violence, every person who committed the act had recent stressors reported. See National Council for Mental Wellbeing, Mass Violence in America Executive Summary (Washington, DC: National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2019), 11.

16 R. Upthegrove et al., “Understanding Auditory Verbal Hallucinations: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence,” Acta Pschiatrica Scandanavica 188 (2016): 355.

17 Elbogen and Johnson, “The Intricate Link Between Violence and Mental Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions.”

18 Rebecca McKetin et al., “Does Methamphetamine Use Increase Violent Behavior? Evidence From a Prospective Longitudinal Study,” Addiction 109 (2014): 901.7. “This means that even if all of the association between mental illness and violence could somehow be eliminated, we would still have to confront 96 percent of the violence in the United States.” See John S. Rozel and Edward P. Mulvey, “The Link Between Mental Illness and Firearm Violence: Implications for Social Policy and Clinical Practice,” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 13, (2017): 445–69.

Writing: Deirdra Assey, CSG Justice Center

Research : Deirdra Assey, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Julia Kessler and Demetrius Thomas, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Darby Baham and Emily Morgan, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Public Affairs: Ruvi Lopez, CSG Justice Center

Web Development : Andrew Currier

This project was supported by Grant No. 2019-MO-BX-K001 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

With support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs’ Bureau of Justice Assistance, The Council…

Unlike drug courts, which have been informed by national standards for 10 years, mental health courts (MHCs)…

With support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs’…

On March 9, 2024, President Joe Biden signed a $460 billion spending…

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- Winter 2024 | VOL. 36, NO. 1 CURRENT ISSUE pp.A5-81

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

The Neurobiology of Violence

- Jan Volavka , M.D., Ph.D.

Search for more papers by this author

Clinical correlates of violent behavior are known, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. This article reviews recent progress in the understanding of such mechanisms involving complex interactions between genes, prenatal and perinatal environmental factors, and rearing conditions. Violent behavior is heterogeneous; that is, impulsive and premeditated violent acts differ in their origins, mechanisms, and management. Recent molecular genetic studies of neurotransmitter regulation are providing new insights into pathophysiology of violent behavior. Functional anatomy of neurotransmitters involved in the regulation of violent behavior is being studied with recently developed brain imaging methods. Increasing evidence indicates commonalities between the neurobiology of violent and suicidal behavior. Progress in the prevention and management of violent behavior depends on studies that address biological factors in their social context. This article updates a previous review.

In the United States, homicide accounts for approximately 20,000 deaths annually. 1 A victimization survey estimated that approximately 4.2 violent crimes (assaults, robberies, and rapes) occur annually for each 100 persons older than 12 years. 1 Another survey of the general adult population found a 3.7% annual rate of self-reported violent behavior against other persons. 2 Thus, violent crime and violent behavior in general cause a major public health problem.

Societal and cultural factors play an important role in the development of violent behavior. However, these environmental factors and their fluctuations elicit different responses in different people. Violent behavior develops as a result of complex interactions between neurobiological and environmental factors. This review will focus primarily on neurobiology. Some of the neurobiological mechanisms of violent behavior are similar or identical to those that operate in suicidal behavior. 3

Substance use, personality disorders, major mental disorders, head injuries, and other diagnosable disorders contribute to the level of community violence. However, recent evidence points to neurobiological mechanisms that affect the development and the control of violent behavior but that are not clearly linked to the existing diagnostic categories. These mechanisms involve neurotransmitters that are in part under genetic control; the details are emerging in current research efforts. The main purpose of this article is to update a previous review, 4 stressing the neurobiological commonalities between aggressive and suicidal behavior.

DEFINITION AND SUBTYPES OF VIOLENT BEHAVIOR

For the purpose of this review, violent behavior is defined as overt and intentional physically aggressive behavior against another person. Examples include beating, kicking, choking, pushing, grabbing, throwing objects, using a weapon, threatening to use a weapon, and forcing sex. The definition does not include aggression against self. Violent crimes include murder, robbery, assault, and rape. In this review, I will not deal with organized state violence or ethnic warfare.

Violent behavior is heterogeneous in its origins and manifestations. Nevertheless, most violent acts can be classified as impulsive or premeditated, and many perpetrators can be classified as committing predominantly impulsive or predominantly premeditated violent acts. There is increasing evidence for the validity of this distinction. Phenytoin reduced impulsive, but not premeditated, violent acts among prisoners. 5 Impulsive violent offenders had lower verbal skills than those committing premeditated violent acts. 6 Persons who committed impulsive murders differed from those who committed premeditated ones in their pattern of brain glucose utilization. 7 Premeditated violent acts may be either predatory (committed for one's own gain; for example, a robbery) or pathological (committed, for example, by mentally ill people acting on their delusions or hallucinations). The mentally ill, however, may also commit predatory or impulsive violent acts.

CLINICAL CORRELATES OF VIOLENT BEHAVIOR

Substance use disorders (alcohol and drugs) play a major role in violent and suicidal behavior. In the United States, 34% of the risk of violence self-reported by community residents is attributable to substance abuse. 2 Urine tests were positive for illicit drugs in 37% to 59% of males arrested for violent crimes in U.S.cities. 8 Among Finnish males, 40% of the risk for homicide is attributable to alcoholism. 9 There are two types of alcoholism. 10 Type 2 accounts for most of the violence associated with alcohol abuse. This type, transmitted from fathers to sons, develops early in life. Type 2 abusers frequently fight under the influence of alcohol and show features of antisocial personality disorder. Personality disorders, particularly the antisocial personality and the borderline personality disorders, are frequently manifested by violent behavior.

A proportion of violent acts occurring in the community are committed by persons diagnosed with major mental disorders such as schizophrenia or mood disorders. Although these disorders carry an elevated risk for violent crime, 9 , 11 only about 4% of the risk for violence self-reported by community residents in the United States is attributable to such disorders. 2 However, major mental disorders are frequently comorbid with substance abuse, 12 and this comorbidity further elevates the risk for violent behavior. 2 , 13 Patients with major mental disorders who stop taking their medication are at a higher risk for developing violent behavior than those who adhere to the treatment. 14 The combination of substance abuse and nonadherence to treatment places patients at a particularly high risk for violence. 15 Brain injuries, particularly those affecting the frontal ventromedial areas 16 or the temporal lobes, are frequently associated with violent behavior. Dementia, mental retardation, and essentially any other disease or disorder affecting the brain may elicit impulsive violent behavior through cognitive impairment and a failure of inhibitory control.

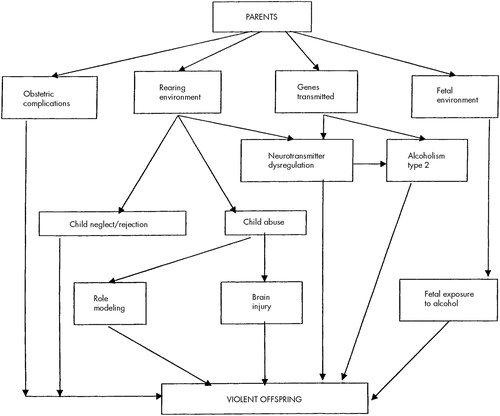

Rearing environment has a powerful effect on behavior, including violence ( Figure 1 ). At least one-third of victims of child abuse grow up to continue the pattern of inept, neglectful, or abusive rearing as parents. 17 Many aspects of the rearing environment are determined by the parents' behavior; that behavior is of course not independent of the parents' genes (a factor not shown in Figure 1). Furthermore, the rearing environment is partly shaped by the child's behavior. Thus, genetic and environmental factors continuously interact in child development.

It is clear that maladaptive behaviors can be learned, but this is not the only mechanism of the intergenerational transfer of violence. Well before any teaching or role modeling takes place, the development of the brain may be affected by various factors in the prenatal and perinatal environment. Fetal exposure to alcohol may contribute to the development of violent behavior. 18 , 19 Early maternal rejection of the child interacts with obstetrical complications to predispose the individual to later (adult) violence. 20 Aggressive behavior is heritable, 21 , 22 and these pre- and perinatal events interact with genetic factors. Some of these complex relationships are depicted in Figure 1 .

The clinical correlates of suicidal and violent behavior overlap: alcohol and drug abuse, personality disorders, schizophrenia, early life experiences, and various brain disorders predispose to both types of behavior. 3

NEUROTRANSMITTERS, THEIR GENETIC CONTROL, AND VIOLENCE

Many neurotransmitters and hormones, including vasopressin, 23 steroids, opioids, and other substances, are involved in the modulation of aggressive behavior. Most of the current evidence strongly supports the roles of serotonin and catecholamines.

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) exerts inhibitory control over impulsive aggression. It is formed in the body by hydroxylation and decarboxylation of the essential amino acid tryptophan. The hydroxylation is the rate-limiting step in 5-HT synthesis; it is catalyzed by tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH). The gene for TPH has been cloned and mapped to the short arm of chromosome 11; two polymorphisms have been identified. The levels of a serotonin metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of impulsive offenders were associated with TPH genotype. 24 In general, these levels are believed to reflect presynaptic serotonergic activity in the brain. Reduced CSF 5-HIAA levels thus indicate a reduction in central serotonergic activity. At the synaptic level, reuptake is a mechanism for the termination of the action of serotonin. This reuptake is accomplished by a plasma membrane carrier called serotonin transporter (5HTT). The gene for 5HTT has been mapped to chromosome 17; a polymorphism has been described. 25 Thus, in summary, serotonin synthesis and activity regulation are under genetic control.

These indices of serotonergic transmission were examined in relation to violent and suicidal behavior. TPH genotype was associated with impulsive-aggressive behavior in male (but not female) patients who had personality disorders 26 as well as with suicide attempts in impulsive offenders 24 and in nonoffenders. 27 Low levels of CSF 5-HIAA have been reported in persons who attempted suicide (particularly by violent means) 28 and in persons with personality disorders who showed high levels of lifetime aggressiveness. 29 In these subjects, there was an association between aggressiveness and suicidal behavior. 29 This trivariate relationship between low levels of CSF 5-HIAA, impulsive aggression, and suicide has been replicated in various other populations. 3 , 4 As mentioned above, type 2 alcoholics frequently exhibit violent behavior; there is a common predisposition underlying the transmission of both alcoholism and violent behavior in families. Type 2 alcoholism is associated with a serotonergic deficit. 30 – 32 An association between low-activity 5HTT promoter genotype and early-onset alcoholism with habitual impulsive violent behavior has been observed. 33 Furthermore, a polymorphism of the 5-HT 1B receptor gene was linked to alcoholism with aggressive and impulsive behavior. 34 A nonhuman primate model confirmed that the serotonergic deficit, assessed by CSF 5-HIAA concentrations, is an antecedent (not a consequence) of alcohol consumption. 35

Neuroendocrine challenges offer another method of indirectly studying central serotonergic activity. A single dose of fenfluramine elevates the plasma levels of prolactin. This response is mediated by serotonergic action, and the prolactin elevation thus measures central serotonin activity. Prolactin response is reduced in aggressive subjects; this measure may be more sensitive than the CSF 5-HIAA. 36

These measures demonstrated a central serotonergic deficit associated with violence, but they could not locate the deficit to any area within the brain. Such localization has now become possible. Localized reductions of the 5HTT-specific binding were visualized in the living human brain. 37 I will return to these results in the section on brain imaging.

Thus, in summary, the association between impulsive violent behavior and central serotonin deficit has been demonstrated by using varied measures of serotonin function. The subjects in these studies were largely diagnosed with personality disorders and alcoholism. The role of serotonergic mechanisms in violent behavior accompanying other disorders is not clear; a small study has failed to detect low levels of CSF 5-HIAA in violent schizophrenic patients. 38

Norepinephrine systems also play a role in aggression. Similar to suicidal behavior, aggression is associated with increased noradrenergic activity. Stress-elicited noradrenergic activity is linked to irritable aggression in animals. The evidence for noradrenergic involvement in human aggression is indirect. Plasma levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine were related to experimentally induced hostile behavior in normal subjects. 39 Growth hormone response to clonidine, an alpha-2-adrenergic receptor agonist, was related to irritability (but not to assaultiveness) in normal subjects and in patients with personality disorders. 40 Furthermore, beta-adrenergic blocking agents have been used clinically to suppress violent behavior in patients with a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders. 41

Two enzymes are important in the catabolism of catecholamines, including norepinephrine: monoamine oxidase (MAO) and catechol- O -methyltransferase (COMT). MAO exists in two forms, A and B. Both types are present in the brain; type B is also in the platelets where it can be assayed. Genes for both types are located at the X chromosome. Several lines of evidence link MAO to aggressive behavior. Low MAO activity was found in the platelets of violent offenders. 42 In a large kindred, several males showed consistent impulsive violent behavior and mental retardation; each of these males had a point mutation in the MAO-A structural gene that resulted in a complete and selective deficiency of the activity of this enzyme. 43 Male “knockout” (genetically altered) mice lacking the MAO-A gene showed aggressive behavior. 44 Thus, low levels of MAO activity were associated with impulsive aggression.

COMT activity is governed by a common polymorphism that results in 3- to 4-fold variations in enzymatic activity. Two studies have demonstrated an association between the allele coding for the less active form of the enzyme and violent behavior in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients. 45 , 46 This association seemed more expressed in males. These small association studies need to be replicated in larger samples of schizophrenic patients and extended to nonschizophrenic subjects. Male (but not female) knockout mice deficient in the COMT gene exhibited aggressive behavior. 47 Thus, in summary, high noradrenergic activity and low activity of the enzymes that catabolize catecholamines are associated with aggressive behavior. The roles of dopaminergic mechanisms in relation to alcoholism and personality traits are being studied; the results have not yet provided a generally accepted pattern of association with violence.

In the preceding paragraphs, I discussed various polymorphisms that contribute to the control of neurotransmission. These polymorphisms are genetically transmitted; this is the template function of the gene. This function is not amenable to any changes due to environmental effects except for mutations. However, the transcriptional function that determines the gene expression (i.e., the manufacture of specific proteins) does depend on environmental and social factors. 48 Gene expression can be modified, for example, by the rearing environment: CSF 5-HIAA in monkeys varies depending on whether they were reared by their mothers or by peers 49 (see Figure 1 ).

GENDER AND VIOLENCE

Gender is a very robust predictor of violent behavior 4 and of suicide. 3 In the United States, male suspects account for 85% of arrests for violent crimes. 1 Victimization surveys as well as self-reports by adults living in the community 2 have generally supported the predominance of males among perpetrators of violence. However, this gender difference is reduced among community residents with major mental disorders and those with substance use disorders, 2 and it disappears among hospitalized psychiatric patients. 4

The gender difference in aggressiveness develops in preschool years, and it is fully expressed by puberty. The difference is partly due to societal causes, including child-rearing practices. Numerous lines of evidence suggest biological origins of the gender difference. As noted above, the TPH, MAO-A, and COMT genotypes show associations with violent behavior that are largely limited to males. Males are more likely than females to develop alcoholism, particularly type 2 alcoholism that is associated with aggression. Elevated circulating testosterone level may be associated with aggression in young males, 50 and perhaps even in young females, 51 but these findings have not been consistently replicated; furthermore, it is not clear whether the hormonal level is an antecedent or a consequence of violent behavior. 52

BRAIN STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

The orbitomedial prefrontal cortex is involved in controlling and inhibiting impulsive actions, and lesions to this area may result in disinhibited aggressive 4 , 16 or suicidal behaviors. 3 Furthermore, literature on aggression points to a dysfunction of parts of the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and the hippocampus, the two limbic structures within the temporal lobe. 53 There is some evidence that the frontal and temporal abnormalities associated with violence may be more expressed in the dominant hemisphere. Until recently, electroencephalography was the main method of studying the function of these systems in humans; this approach was useful in confirming frontotemporal abnormalities in violent individuals (particularly in impulsive violence), but the information was relatively nonspecific in terms of the nature of the dysfunction and its subcortical localization. 54 , 55 More recent imaging methods such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) are providing more specific information. Glucose utilization and blood flow measurements using PET showed abnormality in the left temporal lobe and in the frontal lobes of violent psychiatric patients. 56 Mentally ill murderers showed selective reductions in prefrontal glucose utilization during a continuous performance task. 57 A reanalysis of the data obtained in this study showed that the murderers who had no history of early psychosocial deprivation (e.g., no childhood abuse or family neglect) had lower prefrontal glucose metabolism than murderers with early psychosocial deprivation and a group of normal controls. 58 Thus, these results suggest the existence of two paths toward the development of violent behavior: abnormal neurobiology (prefrontal cortical dysfunction), or abnormal rearing environment. Another reanalysis of these data 57 determined that the impulsive (but not the predatory) offenders had lower prefrontal glucose metabolism in comparison with the control subjects. 7 Thus, prefrontal cortical functioning that controls aggressive behavior was impaired specifically in persons who exhibit impulsive (but not premeditated) violence.

The PET results discussed have revealed brain dysfunctions that were localized, but not specifically linked to any neurotransmitter system. A recent SPECT study reported such specific findings. The 5HTT binding in the midbrain and in the occipital and the frontal mesial cortex of alcoholic impulsive violent offenders was lower than that in healthy control subjects or in nonviolent alcoholics. 37 Interestingly, autoradiographic studies of suicide victims' postmortem brain tissue have also revealed serotonin receptor abnormalities in the ventral prefrontal cortex. 3 The recent PET and SPECT results discussed above will have to be replicated.

If these studies are correct, what are the origins of the brain dysfunctions they reveal? They may be genetic, or due to noxious environmental influences disturbing prenatal neurodevelopment, or related to perinatal complications, or an interaction among these factors. Some structural changes, such as a reduction of the temporal lobe volume, may be caused by child abuse; this effect could be mediated by chronic elevations of glucocorticoids and catecholamines associated with the stress of being maltreated. 59 Similarly, a quantitative EEG study provided preliminary evidence for aberrant cortical development in abused children. 60

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF VIOLENCE

Improvements in prenatal and perinatal care and prevention of head injuries may reduce the level of violence in the community. Since substance use disorders play such an important role in violence, it seems that recidivistic violent crime could be substantially reduced if the treatment of substance use disorders were routinely available to prisoners. In the United States, the availability is inadequate. Facilities that care for schizophrenic and manic patients need to focus on the diagnosis and treatment of the frequently comorbid substance use disorders. Adherence to treatment must be strongly encouraged and monitored in patients with major mental disorders who have a history of recidivistic violence after they discontinue their medication.

Pharmacological treatment of violent behavior in patients with mental disorders is somewhat similar to the treatment of patients with suicidal ideation. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that are routinely used to treat depression were also effective against impulsive aggression in patients with personality disorders who were not suffering from major depression. 61 Clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic medication, is more effective than other antipsychotics in reducing both aggressive 41 and suicidal 3 behaviors in schizophrenia. Pharmacological reduction of violent behavior in persons without mental disorders might be possible, but it could raise ethical issues that have not been addressed. Lithium, a medication that appears to reduce suicide risk for bipolar patients, 3 also reduced impulsive aggressive behavior in prisoners who were not psychotic; 62 both effects could be mediated by an enhancement of serotonergic activity. The administration of an SSRI for 4 weeks to persons without mental disorders has reduced their feelings of hostility. 63 Pharmacological treatments of aggression have been recently reviewed in detail elsewhere. 41 , 64 , 65

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Phenotypic heterogeneity of violent behaviors is a principal problem of this research area. Efforts at subtyping of violence (e.g., impulsive versus premeditated violence) are in progress, but much remains to be done. Most of the neurobiological tools I discussed have separated, one tool at a time, a group of violent subjects from a group of control subjects. Very rarely has a single tool been used to define subgroups of violent patients; using more than one tool for such grouping is even rarer. But even violent behaviors that are phenotypically identical may be heterogeneous from the standpoint of underlying neurobiology.

A fundamental challenge is to translate the recognition of this heterogeneity into research, prevention, and treatment. This requires using the available tools of molecular genetics, neuropharmacology, brain imaging, and psychopharmacology in the same subjects. In this way, it may, for example, become possible to identify patients with specific serotonergic or noradrenergic deficits that could be corrected pharmacologically, or, in the future, perhaps using gene therapy. Furthermore, such a multidisciplinary approach would enable a search for protective factors that might explain, for example, why some patients with very low CSF 5-HIAA do not become violent. Knowledge of such protective factors would be useful in developing strategies for prevention and treatment.

Testing the efficacy of antiaggressive treatments will require substantial modifications of the classic trial designs that have been used in psychopharmacology for the past three decades. The problems to be addressed include the need for precise definition of violent behavior, the difficulty of measuring outcome because of the relative rarity of violent incidents, bias in the selection of patients for study, inadequate and inappropriate control groups, and inattention to comorbidities and concomitant medications in analyzing results. 66

Neurobiological and environmental (e.g., social) factors continuously interact and influence each other. For example, obstetrical complications and maternal rejection interact to raise the propensity for violence, and they may influence each other (e.g., a child with brain dysfunction resulting from obstetrical complications may behave in a way that provokes maternal rejection). To understand the neurobiology of violence, we need to study it in the context of such biosocial interactions.

CONCLUSIONS

The past five years have brought significant progress in our understanding of the neurobiology of violence. The field has been enriched by numerous contributions in the areas of molecular genetics and brain imaging. With deeper understanding of the underlying neurobiology, commonalities between violent and suicidal behaviors can be seen more clearly now.

Up until recently, the assessment of biosocial interactions that result in violent behavior was largely limited to acknowledgments of their existence; we have now progressed to formal statistical demonstrations of these interactions. The “nature or nurture” controversy inherited from Francis Galton has been an underlying philosophical basis of numerous political problems that have plagued the field of violence research during the past decade. 67 The recent studies of biosocial interactions have rendered the controversy of nature and nurture moot; nature is nurture.

FIGURE 1. Mechanisms for the intergenerational transmission of propensity for violence

1 Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Online. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1997 Google Scholar

2 Swanson JW: Mental disorder, substance abuse, and community violence: an epidemiological approach, in Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment, edited by Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994, pp 101–136 Google Scholar

3 Mann JJ: The neurobiology of suicide. Nat Med 1998 ; 4:25–30 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Volavka J: Neurobiology of Violence. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995 Google Scholar

5 Barratt ES, Stanford MS, Felthous AR, et al: The effects of phenytoin on impulsive and premeditated aggression: a controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997 ; 17:341–349 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

6 Barratt ES, Stanford MS, Kent TA, et al: Neuropsychological and cognitive psychophysiological substrates of impulsive aggression. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:1045– 1061 Google Scholar

7 Raine A, Meloy JR, Bihrle S, et al: Reduced prefrontal and increased subcortical brain functioning assessed using positron emission tomography in predatory and affective murderers. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 1998 ; 16:319–332 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Maguire K, Pastore AL, Flanagan TJ (eds): Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 1992. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1993 Google Scholar

9 Eronen M, Hakola P, Tiihonen J: Mental disorders and homicidal behavior in Finland. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996 ; 53:497–501 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

10 Cloninger CR, Bohman M, Sigvardsson S: Inheritance of alcohol abuse: cross-fostering analysis of adopted men. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981 ; 38:861–868 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

11 Hodgins S, Mednick SA, Brennan PA, et al: Mental disorder and crime: evidence from a Danish birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996 ; 53:489–496 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

12 Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 1990; 264:2511– 2518 Google Scholar

13 Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998 ; 55:393–401 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

14 Torrey EF: Violent behavior by individuals with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 1994 ; 45:653–662 Medline , Google Scholar

15 Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry 1998 ; 155:226–231 Medline , Google Scholar

16 Grafman J, Schwab K, Warden D, et al: Frontal lobe injuries, violence, and aggression: a report of the Vietnam head injury study. Neurology 1996; 46:1231– 1238 Google Scholar

17 Oliver JE: Intergenerational transmission of child abuse: rates, research, and clinical implications. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1315– 1324 Google Scholar

18 Brown RT, Coles CD, Smith IE, et al: Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure at school age, II: attention and behavior. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 1991 ; 13:369–376 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

19 Streissguth AP, Randels SP, Smith DF: A test-retest study of intelligence in patients with fetal alcohol syndrome: implications for care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991 ; 30:584–587 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

20 Raine A, Brennan P, Mednick SA: Interaction between birth complications and early maternal rejection in predisposing individuals to adult violence: specificity to serious, early-onset violence. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1265– 1271 Google Scholar

21 Coccaro EF, Bergeman CS, Kavoussi RJ, et al: Heritability of aggression and irritability: a twin study of the Buss-Durkee aggression scales in adult male subjects. Biol Psychiatry 1997 ; 41:273–284 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

22 Bergeman CS, Seroczynski AD: Genetic and environmental influences on aggression and impulsivity, in Neurobiology and Clinical Views on Aggression and Impulsivity, edited by Maes M, Coccaro EF. Chichester, UK, Wiley, 1998, pp 63–80 Google Scholar

23 Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ, Hauger RL, et al: Cerebrospinal fluid vasopressin levels: correlates with aggression and serotonin function in personality-disordered subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998 ; 55:708–714 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

24 Nielsen DA, Goldman D, Virkkunen M, et al: Suicidality and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentration associated with a tryptophan hydroxylase polymorphism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994 ; 51:34–38 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

25 Collier DA, Stober G, Li T, et al: A novel functional polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene: possible role in susceptibility to affective disorders. Molecular Psychiatry 1996 ; 1:453–460 Medline , Google Scholar

26 New AS, Gelernter J, Yovell Y, et al: Tryptophan hydroxylase genotype is associated with impulsive-aggression measures: a preliminary study. American Journal of Medical Genetics 1998 ; 81:13–17 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

27 Courtet P, Buresi C, Abbar M, et al: Association between the tryptophan hydroxylase gene and suicidal behavior (abstract 146). Presented at the American Psychiatric Association 151st annual meeting, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, May 30–June 4, 1998 Google Scholar

28 Åsberg M, Traskman L, Thoren P: 5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal fluid: a biochemical suicide predictor? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1193– 1197 Google Scholar

29 Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, et al: Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1979 ; 1:131–139 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

30 Virkkunen M, Linnoila M: Serotonin in early-onset, male alcoholics with violent behaviour. Ann Med 1990 ; 22:327–331 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

31 LeMarquand D, Pihl RO, Benkelfat C: Serotonin and alcohol intake, abuse, and dependence: clinical evidence. Biol Psychiatry 1994 ; 36:326–337 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

32 Cloninger CR: The psychobiological regulation of social cooperation. Nat Med 1995 ; 1:623–625 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

33 Hallikainen T, Saito T, Lachman HM, et al: Association between low activity serotonin transporter promoter genotype with habitual impulsive behavior among antisocial early onset alcoholics. Molecular Psychiatry 1999 (in press) Google Scholar

34 Lappalainen J, Long JC, Eggert M, et al: Linkage of antisocial alcoholism to the serotonin 5-HT 1B receptor gene in 2 populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998 ; 55:989–994 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

35 Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M: A nonhuman primate model of type II excessive alcohol consumption? Part I: low cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentrations and diminished social competence correlate with excessive alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996 ; 20:629–642 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

36 Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ, Cooper TB, et al: Central serotonin activity and aggression: inverse relationship with prolactin response to d -fenfluramine, but not CSF 5-HIAA concentration, in human subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1430– 1435 Google Scholar

37 Tiihonen J, Kuikka JT, Bergstrom KA, et al: Single-photon emission tomography imaging of monoamine transporters in impulsive violent behaviour. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine 1997; 24:1253– 1260 Google Scholar

38 Kunz M, Sikora J, Krakowski M, et al: Serotonin in violent patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1995 ; 59:161–163 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

39 Gerra G, Zaimovic A, Avanzini P, et al: Neurotransmitter-neuroendocrine responses to experimentally induced aggression in humans: influence of personality variable. Psychiatry Res 1997 ; 66:33–43 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

40 Coccaro EF, Lawrence T, Trestman R, et al: Growth hormone responses to intravenous clonidine challenge correlate with behavioral irritability in psychiatric patients and healthy volunteers. Psychiatry Res 1991 ; 39:129–139 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

41 Citrome L, Volavka J: Psychopharmacology of violence, II: beyond the acute episode. Psychiatric Annals 1997 ; 27:696–703 Crossref , Google Scholar

42 Belfrage H, Lidberg L, Oreland L: Platelet monoamine oxidase activity in mentally disordered violent offenders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992 ; 85:218–221 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

43 Brunner HG, Nelen M, Breakefield XO, et al: Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science 1993 ; 262:578–580 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

44 Cases O, Seif I, Grimsby J, et al: Aggressive behavior and altered amounts of brain serotonin and norepinephrine in mice lacking MAOA. Science 1995; 268:1763– 1766 Google Scholar

45 Strous RD, Bark N, Parsia SS, et al: Analysis of a functional catechol O -methyltransferase gene polymorphism in schizophrenia: evidence for association with aggressive and antisocial behavior. Psychiatry Res 1997 ; 69:71–77 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

46 Lachman HM, Nolan KA, Mohr P, et al: Association between catechol O -methyltransferase genotype and violence in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998 ; 155:835–837 Medline , Google Scholar

47 Gogos JA, Morgan M, Luine V, et al: Catechol- O -methyltransferase-deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic changes in catecholamine levels and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95:9991– 9996 Google Scholar

48 Kandel ER: A new intellectual framework for psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 1998 ; 155:457–469 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

49 Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M: A longitudinal assessment of CSF monoamine metabolite and plasma cortisol concentrations in young rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry 1992 ; 32:127–145 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

50 Dabbs JM Jr, Carr TS, Frady RL, et al: Testosterone, crime, and misbehavior among 692 male prison inmates. Personality and Individual Differences 1995 ; 18:627–633 Crossref , Google Scholar

51 Dabbs JM Jr, Hargrove MF: Age, testosterone, and behavior among female prison inmates. Psychosom Med 1997 ; 59:477–480 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

52 Susman EJ, Worrall BK, Murowchick E, et al: Experience and neuroendocrine parameters of development: aggressive behavior and competencies, in Aggression and Violence: Genetic, Neurobiological, and Biosocial Perspectives, edited by Stoff DM, Cairns RB. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1996, pp 267–289 Google Scholar

53 Bear D: Neurological perspectives on aggressive behavior. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:S3–S8 Google Scholar

54 Volavka J: Aggression, electroencephalography, and evoked potentials: a critical review. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1990 ; 3:249–259 Google Scholar

55 Convit A, Douyon R, Yates K, et al: Frontotemporal abnormalities and violent behavior, in Aggression and Violence: Genetic, Neurobiological, and Biosocial Perspectives, edited by Stoff DM, Cairns RB. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1996, pp 169–194 Google Scholar

56 Volkow ND, Tancredi L: Neural substrates of violent behaviour: a preliminary study with positron emission tomography. Br J Psychiatry 1987 ; 151:668–673 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

57 Raine A, Buchsbaum M, LaCasse L: Brain abnormalities in murderers indicated by positron emission tomography. Biol Psychiatry 1997 ; 42:495–508 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

58 Raine A, Phil D, Stoddard J, et al: Prefrontal glucose deficits in murderers lacking psychosocial deprivation. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1998 ; 11:1–7 Medline , Google Scholar

59 DeBellis MD, Casey BJ, Clark DB, et al: Anatomical MRI in maltreated children with PTSD (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1998 ; 43:16S Crossref , Google Scholar

60 Ito Y, Teicher MH, Glod CA: Preliminary evidence for aberrant cortical development in abused children: a quantitative EEG study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998 ; 10:298–307 Link , Google Scholar

61 Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ: Fluoxetine and impulsive aggressive behavior in personality-disordered subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1081– 1088 Google Scholar

62 Sheard MH, Marini JL, Bridges CI, et al: The effect of lithium on impulsive aggressive behavior in man. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:1409– 1413 Google Scholar

63 Knutson B, Wolkowitz OM, Cole SW, et al: Selective alteration of personality and social behavior by serotonergic intervention. Am J Psychiatry 1998 ; 155:373–379 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

64 Citrome L, Volavka J: Psychopharmacology of violence, I: assessment and acute treatment. Psychiatric Annals 1997 ; 27:691–695 Crossref , Google Scholar

65 Citrome L, Volavka J: The efficacy of pharmacological treatments in preventing crime and violence among persons with psychotic disorders, in Violence, Crime, and Mentally Disordered Offenders: Concepts and Methods for Effective Treatment and Prevention, edited by Hodgins S, Muller-Isberner R. New York, Wiley (in press) Google Scholar

66 Volavka J, Citrome L: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of the persistently aggressive psychotic patient: methodological concerns. Schizophr Res 1999 (in press) Google Scholar

67 Touchette N: Genetics and crime: It's not over. Till it's over. Journal of NIH Research 1993 ; 5:32–34 Google Scholar

- Examining the cognitive contributors to violence risk in forensic samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 74

- Assessing attentional bias to emotions in adolescent offenders and nonoffenders 24 November 2023 | Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 14

- Prediction of violence: Part contagious disease, part unpredictable individual: Is a public health assessment approach an additional option and at what cost? 3 March 2023 | Behavioral Sciences & the Law, Vol. 41, No. 5

- Low oxytocin levels in schizophrenia patients involved in crime and the relationship of these levels to aggression, empathy and forgiveness 15 December 2022 | The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, Vol. 34, No. 1

- Effects of Psychiatric Disease Severity and Clinical Characteristics on Duration of High Violence Risk: A Perspective on Violence Prevention in the Psychiatric Ward 1 March 2023 | Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Vol. Volume 19

- Assessment and Management of Violent Behavior 1 July 2023

- A Machine Learning Approach to the Analytics of Representations of Violence in Khaled Hosseini's Novels

- Violent crimes and homicide in New York City: The role of weather and pollution Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Vol. 91

- Personality Factors Predicting Cyberbullying and Online Harassment

- Biochemical Factors in Aggression and Violence

- Anger Experience and Anger Expression Through Drawing in Schizophrenia: An fNIRS Study 1 September 2021 | Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 12

- Reprint of "Executive dysfunction, violence and aggression" Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 54

- Sex Differences in QEEG in Psychopath Offenders 6 September 2019 | Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, Vol. 51, No. 3

- Executive dysfunction, violence and aggression Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 51

- Psychometric properties of the Impulsive/Premeditated Aggression Scale in Portuguese community and forensic samples 1 June 2019 | Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Vol. 41, No. 2

- Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 47

- Workplace violence perpetrated by clients of health care: A need for safety and trauma‐informed care 30 October 2018 | Journal of Clinical Nursing, Vol. 28, No. 1-2

- Neurobiology of Brain Injury and its Link with Violence and Extreme Single and Multiple Homicides 16 February 2018

- Applied Nursing Research, Vol. 43

- Revue Neurologique, Vol. 174, No. 4

- Criminal Justice and Behavior, Vol. 45, No. 4

- Preventing aggressive/violent behavior: a role for biomarkers? Biomarkers in Medicine, Vol. 11, No. 9

- Psychological Medicine, Vol. 47, No. 7

- Prevalence and Correlates of Aggression and Hostility in Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients 11 July 2016 | Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 32, No. 2

- Doriana Chialant , Ph.D. ,

- Judith Edersheim , M.D., J.D. ,

- Bruce H. Price , M.D.

- Journal of Veterinary Behavior, Vol. 16

- Psychology of Sport and Exercise, Vol. 22

- Serotonin and Dopamine Candidate Gene Variants and Alcohol- and Non-Alcohol-Related Aggression 3 June 2015 | Alcohol and Alcoholism, Vol. 50, No. 6

- Treatment of Aggressive and Violent Behavior 20 February 2015

- Cognitive Systems Research, Vol. 34-35

- L'Encéphale, Vol. 41, No. 5

- Safety Science, Vol. 78

- Val158Met COMT polymorphism and risk of aggression in alcohol dependence 3 October 2013 | Addiction Biology, Vol. 20, No. 1

- Impulsivity and Physical Aggression: Examining the Moderating Role of Anxiety The American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 127, No. 2

- Rousseau, Happiness and Human Nature 13 November 2012 | Political Studies, Vol. 62, No. 1

- Neurology and Neurochemistry of Crime 27 November 2018

- Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 19, No. 1

- Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 19, No. 3

- Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol. 58

- The COMT Met158 allele and violence in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis Schizophrenia Research, Vol. 140, No. 1-3

- Journal of Family Violence, Vol. 27, No. 1

- International Review of Economics, Vol. 59, No. 4

- Persönlichkeitsstörungen

- Schizophrenia Bulletin, Vol. 38, No. 1

- Foreign Policy Analysis, Vol. 8, No. 2

- Genomic architecture of aggression: Rare copy number variants in intermittent explosive disorder 2 August 2011 | American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, Vol. 156, No. 7

- Manganese Exposure from Drinking Water and Children’s Classroom Behavior in Bangladesh Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 119, No. 10

- Current Psychology, Vol. 30, No. 4

- Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 16, No. 6

- Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 39, No. 1

- Research in Veterinary Science, Vol. 91, No. 3

- An Exploratory Analysis of Factors Associated With Repeat Homicide in Canada 22 March 2010 | Homicide Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2

- Journal of Neural Transmission, Vol. 117, No. 3

- Neuroethics, Vol. 3, No. 1

- The Combative Patient

- États dangereux et troubles mentaux

- Accident Analysis & Prevention, Vol. 42, No. 6

- Medical Hypotheses, Vol. 74, No. 3

- Brain, Vol. 133, No. 12

- Low Resting Heart Rate and Antisocial Behavior 10 August 2009 | Criminal Justice and Behavior, Vol. 36, No. 11

- Evil: Illusion of 15 September 2009

- Influence of Functional Variant of Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase on Impulsive Behaviors in Humans Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol. 66, No. 1

- Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, Vol. 171, No. 3

- Polypharmacy With Second-Generation Antipsychotics: A Review of Evidence Journal of Psychiatric Practice, Vol. 14, No. 6

- The Neural Basis of Moral Cognition 3 April 2008 | Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1124, No. 1

- Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Vol. 4, No. 2

- Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 13, No. 5

- Physiology & Behavior, Vol. 94, No. 4

- Seyed Mohammad Assadi, M.D.

- Maryam Noroozian, M.D.

- Seyed Vahid Shariat, M.D.

- Omid Yahyazadeh, M.D.

- Mahdi Pakravannejad, M.D.

- Shahrokh Aghayan, M.D.

- Contrary to popular belief, a lack of behavioural inhibitory control may not be associated with aggression 27 June 2007 | Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, Vol. 17, No. 3

- Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 12, No. 1

- Schizophrenia Research, Vol. 97, No. 1-3

- Neuropsychopharmacology, Vol. 32, No. 11

- Steven G. Sugden, M.D.

- Shawn J. Kile, M.D.

- Robert L. Hendren, D.O.

- Journal of Family Violence, Vol. 21, No. 7

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Vol. 15, No. 2

- Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, Vol. 147, No. 2-3

- International Journal of Nursing Studies, Vol. 42, No. 2

- Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Vol. 114, No. 3

- Serial murder by children and adolescents 16 June 2004 | Behavioral Sciences & the Law, Vol. 22, No. 3

- Association of serotonin transporter promoter gene polymorphism with violence: relation with personality disorders, impulsivity, and childhood ADHD psychopathology 16 June 2004 | Behavioral Sciences & the Law, Vol. 22, No. 3

- Role of experience in processing bias for aggressive words in forensic and non-forensic populations 1 January 2004 | Aggressive Behavior, Vol. 30, No. 2

- Australian Emergency Nursing Journal, Vol. 7, No. 2

- Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 55, No. 5

- Aggression, psychopathology, and delinquency: influences of gender and maturation – where did all the good girls go?

- Antiaggressive Action of Combined Risperidone and Quetiapine in a Patient with Schizophrenia 1 July 2003 | The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 48, No. 6

- Expanding Evolutionary Psychology: toward a Better Understanding of Violence and Aggression 29 June 2016 | Social Science Information, Vol. 42, No. 1

- Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol. 37, No. 6

- Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, Vol. 11, No. 2

- International Journal of Men's Health, Vol. 2, No. 1

- Annotation: The role of prefrontal deficits, low autonomic arousal, and early health factors in the development of antisocial and aggressive behavior in children 21 April 2002 | Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Vol. 43, No. 4

- Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 52, No. 1

- VIOLENCE against Psychiatric Nurses: An Untreated Epidemic? Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, Vol. 40, No. 1

- Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer disease 1 March 2001 | Annals of Neurology, Vol. 49, No. 3

- Epilepsy & Behavior, Vol. 1, No. 3

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Vol. 9, No. 4

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 23 January 2017

Mental illness and violent behavior: the role of dissociation

- Aliya R. Webermann 1 &

- Bethany L. Brand 2

Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation volume 4 , Article number: 2 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

12 Citations

67 Altmetric

Metrics details

The role of mental illness in violent crime is elusive, and there are harmful stereotypes that mentally ill people are frequently violent criminals. Studies find greater psychopathology among violent offenders, especially convicted homicide offenders, and higher rates of violence perpetration and victimization among those with mental illness. Emotion dysregulation may be one way in which mental illness contributes to violent and/or criminal behavior. Although there are many stereotyped portrayals of individuals with dissociative disorders (DDs) being violent, the link between DDs and crime is rarely researched.

We reviewed the extant literature on DDs and violence and found it is limited to case study reviews. The present study addresses this gap through assessing 6-month criminal justice involvement among 173 individuals with DDs currently in treatment. We investigated whether their criminal behavior is predicted by patient self-reported dissociative, posttraumatic stress disorder and emotion dysregulation symptoms, as well as clinician-reprted depressive disorders and substance use disorder.

Past 6 month criminal justice involvement was notably low: 13% of the patients reported general police contact and 5% reported involvement in a court case, although either of these could have involved the DD individual as a witness, victim or criminal. Only 3.6% were recent criminal witnesses, 3% reported having been charged with an offense, 1.8% were fined, and 0.6% were incarcerated in the past 6 months. No convictions or probations in the prior 6 months were reported. None of the symptoms reliably predicted recent criminal behavior.

Conclusions

In a representative sample of individuals with DDs, recent criminal justice involvement was low, and symptomatology did not predict criminality. We discuss the implications of these findings and future directions for research.

Stereotypes abound in the media regarding violent behavior and crimes among those with mental illness. One need not look further than popular crime television shows, the latest blockbuster film or news stories on perpetrators of atrocities such as school shootings or terrorist attacks. Researchers have worked to unpack the complex question of what role mental illness plays in violence, if any, especially in light of mass shootings in the United States at Sandy Hook Elementary, Virginia Tech University and Pulse Nightclub, among others. Researchers generally agree that there is some relationship between mental illness and the risk for violence, such that mental illness increases the risk for violence perpetration as well as victimization, but there is less consensus on the specific psychopathology and symptoms that contribute to violence.

A brief literature review on mental illness and violent behavior

Stereotypes about mental illness and violence are common among the general public. Link, Phelan, Bresnahan, Stueve and Pescosolido [ 1 ] presented a large sample ( N = 1444) with vignettes of people with mental illness, in which no violent behavior or thoughts were described, and inquired how likely it was that the “patient” would be violent. Many participants believed it likely that the hypothetical mentally ill individual would perpetrate violence: 17% of respondents endorsed violence as likely among those with minor interpersonal problems, and 33% and 61% thought violence was likely among people with major depression or schizophrenia, respectively. Individuals with mental illness are frequently aware of others’ negative perceptions of them, which can worsen isolation, negative affect and treatment adherence [ 2 , 3 ].

Individuals with psychological disorders that are highly stigmatized and misunderstood, such as schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder (BPD) and dissociative identity disorder (DID), often face harmful and inaccurate stereotypes which portray them as dangerous and untreatable menaces who require psychiatric or forensic institutionalization. However, as we will review in this study, it is a myth that individuals with DID are the most likely patients in the mental health system to be violent. Various methodologies have been used to study the link between mental illness and violence including: reporting on the prevalence of mental illness among convicted violent offenders, typically homicide defendants; examining violent behavior and crime among clinical populations; and assessing prevalence of violent behavior and crime among those with mental illness in the general population (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 and 5 below for the results of studies utilizing each of these methodologies). Many studies examine only violence perpetration, but some examine victimization as well [ 4 – 6 ] (Table 1 ).

In research on the prevalence of mental illness among violent offenders, multiple studies have found the highest rates of violence among individuals with substance use disorders, rather than schizophrenia, BPD and other psychotic disorders [ 7 – 11 ] (Tables 2 and 3 ). Rates of substance use disorders (including alcohol use disorders and illicit substance use disorders) among self-reported violent offenders range from 20 to 42% [ 7 , 11 , 12 ] (Table 2 ). Rates of substance use disorders among convicted homicide offenders are lower but still noteworthy, ranging from 1 to 20% [ 8 , 9 , 13 , 14 ] (Table 3 ).

Other studies have approached the question of how mental illness intersects with violence through examining rates of violent behavior among clinical populations. These studies tend to focus on severe/serious mental illness (SMI), that is, disorders which cause or are associated with serious functional impairment or limitations on major life activities [ 15 ]. The majority of studies on violent behavior among SMI patients focus on schizophrenia, although some also include other SMIs such as bipolar disorder and antisocial personality disorder (Table 4 ). Studies on violent behavior and homicide among individuals with schizophrenia indicate these individuals are at increased risk for both violence perpetration and victimization, but that violence is often predicted by comorbid substance use, medication noncompliance and a recent history of being assaulted [ 16 – 18 ]. Studies on violent behavior among individuals with BPD indicate that emotion dysregulation is a longitudinal mediator of violent behavior and may be a primary mechanism that increases risk for violence in this population [ 19 , 20 ]. The complex DDs, including DID, have been conceptualized as disorders of emotional dysregulation and are often highly comorbid with BPD [ 21 ]. The association of emotion dysregulation with violence in DDs should be further examined.

Dissociative disorders and violent behavior

Notably missing from almost all studies on the intersection of mental illness and violent crime are individuals with dissociative disorders (DDs), including DID and DD not otherwise specified (DDNOS in DSM-IV)/other specified DD (OSDD in DSM-5). This is true of mixed clinical population studies [ 22 – 25 ], studies on violence and mental illness in the general population [ 7 , 11 , 12 , 26 ], as well as forensic studies of convicted violent offenders [ 8 , 9 , 13 , 14 , 27 ]. Although DID is missing from almost all the research on mental illness and violence, it gets an inordinate amount of focus in films about mental illness, particularly those in the horror and thriller genres such as Split , Psycho, Fight Club or Secret Window which portray people with dissociative self-states as prone to violence including homicide, or within comedies that poke fun at the “outlandishness” of dissociative self-states, such as Me, Myself and Irene. Given the paucity of research on violent behavior among individuals with DDs, coupled with the saturation of stereotypic portrayals of DDs in the media, misunderstanding abounds regarding what role dissociation plays in violent behavior, if any.

A few studies have examined dissociative symptoms, rather than DDs, as a predictor of violent interpersonal behavior within mixed clinical populations (Table 4 ). They typically focus on trait dissociation, that is, chronic and enduring dissociative experiences across multiple contexts [ 28 ], compared to state dissociation, e.g., transient, not enduring and time-limited dissociative experiences [ 29 ], the latter of which are often anecdotally reported by violent offenders, such as amnesia for a violent episode and violence-related dissociative episodes [ 30 ]. Quimby and Putnam [ 31 ] found that among adult psychiatric inpatients, trait dissociation was positively correlated with patient sexual aggression via staff reports. Kaplan and colleagues [ 32 ] found a positive correlation between trait dissociation and patient-reported general aggression among psychiatric outpatients. Dissociation has also been posited to play a role in the intergenerational transmission of domestic violence: grouping young mothers who were survivors of childhood maltreatment based on whether or not they abused their own children, Egeland and Susman-Stillman [ 33 ] found significantly greater trait dissociation among mothers who were abusive as compared to those who were not.

A number of case study reviews, conducted nearly three decades ago, reported high rates of violent behavior among patients with DID, according to reports by their treating clinicians [ 34 – 38 ] (Table 5 ). These studies were typically conducted with small samples derived from the authoring clinician’s case load, relied on clinician reports rather than patient self-report, utilized adult lifetime reporting timeframes rather than specified time frames (the latter is more typical of current studies on violence and mental illness), and did not attempt to objectively verify violent behavior through criminal records or other official documentation. Many studies inquired about DID patients’ violent and/or homicidal dissociative self-states. Footnote 1 Therapists reported that between 33 and 70% of DID patients had violent self-states [ 34 – 37 ]. At times, aggressive self-states within individuals with DID threaten other self-states, which some patients perceive to be internalized homicidal ideation and/or threats, but if carried out, would result in suicide and not homicide. Some of the studies reviewed above did not distinguish violent self-states who were violent towards the individual themselves versus those who were externally violent toward others [ 34 – 36 ]. Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] make the distinction that while 70% of those with DID had violent or homicidal self-states, 53% of the aggressive self-states were “internally homicidal,” that is, with homicidal ideation toward another self-state. Some DID patients may misperceive these internally aggressive self-states as external violent people, rather than the patient being self-destructive or suicidal [ 39 ]. Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] describe internalized homicidal behavior as occurring among 53% of their 100 DID patient sample. Some DID patients may also experience flashbacks of past violence perpetrated by another person against them and mistakenly believe they are perpetrating violence against someone else when in fact they are experiencing an intrusive recollection of the past [ 39 ].

Within these aforementioned case studies, clinicians reported that 38–55% of their DID patients had a history of any violent behavior [ 34 , 36 – 38 ]. Ross and Norton [ 38 ] reported that of 236 DID patients, 29% of the males and 10% of females reported being convicted of a crime, and the same percentage reported a history of incarceration. While the type of conviction and reason for incarceration were not specified, Ross and Norton [ 38 ] describe more antisocial behavior among men than women. Loewenstein and Putnam [ 36 ] and Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] report high rates of sexual assault perpetration among their DID patient samples. Among an all-male sample, Loewenstein and Putnam [ 36 ] reported 13% of patients reported having perpetrated a sexual assault, while in a predominately female sample, Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] reported 20% of patients reported having perpetrated sexual assault. Lewis, Yeager, Swica, Pincus and Lewis [ 40 ] reported severe childhood maltreatment and adult psychopathology among 12 DID inmates who were incarcerated for homicide. Two studies found 19% of DID patients had completed homicide [ 36 , 37 ]. Loewenstein and Putnam [ 36 ] attribute this extremely high rate of violent behavior to the childhood maltreatment these patients experienced which increases their risk for aggression and violence, as well as their reliance on an all-male sample, who have higher rates of violence. Alternatively, Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] describe confusion about “personified intraphysic conflicts” among the patients leading to misperceptions about the degree of actual violence among DID patients, as described above.