Open 365 days a year, Mount Vernon is located just 15 miles south of Washington DC.  From the mansion to lush gardens and grounds, intriguing museum galleries, immersive programs, and the distillery and gristmill. Spend the day with us!  Discover what made Washington "first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen".  The Mount Vernon Ladies Association has been maintaining the Mount Vernon Estate since they acquired it from the Washington family in 1858.  Need primary and secondary sources, videos, or interactives? Explore our Education Pages!  The Washington Library is open to all researchers and scholars, by appointment only. Federalist Papers George Washington was sent draft versions of the first seven essays on November 18, 1787 by James Madison, who revealed to Washington that he was one of the anonymous writers. Washington agreed to secretly transmit the drafts to his in-law David Stuart in Richmond, Virginia so the essays could be more widely published and distributed. Washington explained in a letter to David Humphreys that the ratification of the Constitution would depend heavily "on literary abilities, & the recommendation of it by good pens," and his efforts to proliferate the Federalist Papers reflected this feeling. 1 Washington was skeptical of Constitutional opponents, known as Anti-Federalists, believing that they were either misguided or seeking personal gain. He believed strongly in the goals of the Constitution and saw The Federalist Papers and similar publications as crucial to the process of bolstering support for its ratification. Washington described such publications as "have thrown new lights upon the science of Government, they have given the rights of man a full and fair discussion, and have explained them in so clear and forcible a manner as cannot fail to make a lasting impression upon those who read the best publications of the subject, and particularly the pieces under the signature of Publius." 2 Although Washington made few direct contributions to the text of the new Constitution and never officially joined the Federalist Party, he profoundly supported the philosophy behind the Constitution and was an ardent supporter of its ratification. The philosophical influence of the Enlightenment factored significantly in the essays, as the writers sought to establish a balance between centralized political power and individual liberty. Although the writers sought to build support for the Constitution, Madison, Hamilton, and Jay did not see their work as a treatise, per se, but rather as an on-going attempt to make sense of a new form of government. The Federalist Paper s represented only one facet in an on-going debate about what the newly forming government in America should look like and how it would govern. Although it is uncertain precisely how much The Federalist Papers affected the ratification of the Constitution, they were considered by many at the time—and continue to be considered—one of the greatest works of American political philosophy. Adam Meehan The University of Arizona Notes: 1. "George Washington to David Humphreys, 10 October 1787," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 657. 2. "George Washington to John Armstrong, 25 April 1788," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 672. Bibliography: Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life . New York: Penguin, 2010. Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of The Federalist . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. Furtwangler, Albert. The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984. George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel. New York: Library of America, 1997. Quick Links 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.  - Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

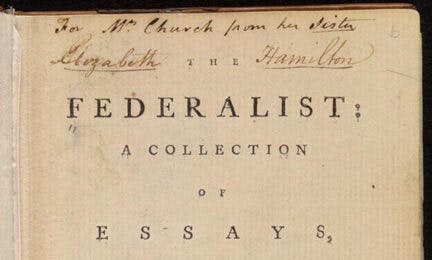

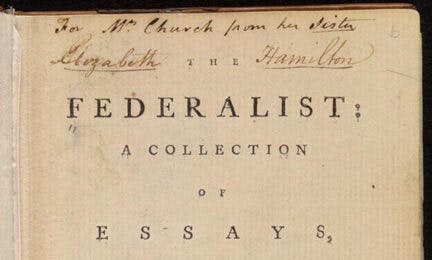

Federalist papers summaryFederalist papers , formally The Federalist , Eighty-five essays on the proposed Constitution of the United States and the nature of republican government, published in 1787–88 by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay in an effort to persuade voters of New York state to support ratification. Most of the essays first appeared serially in New York newspapers; they were reprinted in other states and then published as a book in 1788. A few of the essays were issued separately later. All were signed “Publius.” They presented a masterly exposition of the federal system and the means of attaining the ideals of justice, general welfare, and the rights of individuals.  Top of page Film, Video Federalist PapersBack to Search Results Event video About this Item- Federalist Papers

- In this segment of From the Vaults in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, we discuss the history of the Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The Federalist Papers were written and published to urge New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution, which was drafted in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787.

- Library of Congress

- Library of Congress. Rare Book Division, sponsoring body

Created / Published- Washington, D.C. : Library of Congress, 2022-03-02.

- - Mark Dimunation.

- - Recorded on 2022-03-02.

- 1 online resource

- https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gdc/gdcwebcasts.210630rbk1300

Library of Congress Control NumberOnline format. LCCN Permalink- https://lccn.loc.gov/2024697873

Additional Metadata Formats- MARCXML Record

- MODS Record

- Dublin Core Record

- From the Vaults (27)

- Event Videos (7,542)

- Rare Book and Special Collections Division (28,491)

- General Collections (196,462)

- Library of Congress Online Catalog (1,603,359)

- Film, Video

Contributor- Library of Congress. Rare Book Division

Featured in- Event Videos | News & Events | Rare Book and Special Collections Reading Room | Research Centers

Rights & AccessWhile the Library of Congress created most of the videos in this collection, they include copyrighted materials that the Library has permission from rightsholders to present. Rights assessment is your responsibility. The written permission of the copyright owners in materials not in the public domain is required for distribution, reproduction, or other use of protected items beyond that allowed by fair use or other statutory exemptions. There may also be content that is protected under the copyright or neighboring-rights laws of other nations. Permissions may additionally be required from holders of other rights (such as publicity and/or privacy rights). Whenever possible, we provide information that we have about copyright owners and related matters in the catalog records, finding aids and other texts that accompany collections. However, the information we have may not be accurate or complete. More about Copyright and other Restrictions For guidance about compiling full citations consult Citing Primary Sources . Credit Line: Library of Congress Cite This ItemCitations are generated automatically from bibliographic data as a convenience, and may not be complete or accurate. Chicago citation style:Library Of Congress, and Sponsoring Body Library Of Congress. Rare Book Division. Federalist Papers . Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, -03-02, 2022. Video. https://www.loc.gov/item/2024697873/. APA citation style:Library Of Congress & Library Of Congress. Rare Book Division, S. B. (2022) Federalist Papers . Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, -03-02. [Video] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2024697873/. MLA citation style:Library Of Congress, and Sponsoring Body Library Of Congress. Rare Book Division. Federalist Papers . Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, -03-02, 2022. Video. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2024697873/>. Navigation menuPersonal tools. - View source

- View history

- Encyclopedia Home

- Alphabetical List of Entries

- Topical List

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

The Federalist PapersThe Federalist Papers originated as a series of articles in a New York newspaper in 1787–88. Published anonymously under the pen name of “Publius,” they were written primarily for instrumental political purposes: to promote ratification of the Constitution and defend it against its critics. Initiated by Alexander Hamilton , the series came to eighty-five articles, the majority by Hamilton himself, twenty-six by James Madison , and five by John Jay. The Federalist was the title under which Hamilton collected the papers for publication as a book. Despite their polemical origin, the papers are widely viewed as the best work of political philosophy produced in the United States, and as the best expositions of the Constitution to be found amidst all the ratification debates. They are frequently cited for discerning the meaning of the Constitution and the intentions of the founders, although Hamilton’s papers are not always reliable as an exposition of his views: in The Federalist , Hamilton took care to avoid coming out clearly with his views on either the inadequacies of the Constitution or the potentiality for using it dynamically. Instead, he expressed himself indirectly, arguing that the only real danger would arise from the potential weaknesses of the central government under the Constitution , not from its potentialities for greater strength as charged by its opponents. Despite this, The Federalist can be and frequently has been referred to for its exposition of Hamilton’s position on executive authority, judicial review, and other institutional aspects of the Constitution. The Federalist Papers are also admired abroad—sometimes more than in the United States. Hamilton is held in high esteem abroad: while in America his realist style is received with suspicion of undemocratic intentions, abroad it is taken as a reassurance of solidity, and it is the Jeffersonian idealist style that is received with suspicion of hidden intentions. The Federalist Papers are studied by jurists and legal scholars and cited for writing other countries’ constitutions. In this capacity they have played a significant role in the spread of federal, democratic, and constitutional governments around the world. - 1 MODERN FEDERATION AS EXPOUNDED BY THE FEDERALIST

- 2 AMBIGUITIES OF COORDINATE FEDERALISM IN THE FEDERALIST

- 3 USE AND ABUSE OF THE FEDERALIST

- 4.1 Ira Straus

MODERN FEDERATION AS EXPOUNDED BY THE FEDERALISTThe Federalist Papers defended a new form of federalism : what it called “federation” as differentiated from “confederation.” There were precursors for this usage; The Federalist Papers solidified it. All subsequent federalism has been influenced by the example of “federation” in the United States; indeed, the success of it in the United States has led to its being known as “modern federation” in contrast to “classical confederation.” In its basic structures and principles, it has served as the model for most subsequent federal unions, as well as for the reform of older confederacies such as Switzerland. The main distinguishing characteristics of the model of modern federation, elucidated and defended by The Federalist Papers , are as follows: 1. The federal government’s most important figures, the legislative, are elected largely by the individual citizens, rather than being primarily selected by the governments of member states as in confederation. 2. Conversely, federal law applies directly to individuals, through federal courts and agencies, rather than to member states as in confederation. 3. State citizens become also federal citizens, and naturalization criteria are established federally. 4. The federal Constitution and federal laws and treaties are the supreme law of the land, over and above state constitutions and laws. 5. Federal powers are enumerated, along with what came to be called an “Elastic Clause” (the authority to take measures “necessary and proper” for implementing its enumerated powers); the states keep the vast range of “reserved” powers, that is, the unspecified generality of other potential governmental powers. States cannot act where the federal government is assigned exclusive competence, nor where preempted by lawful federal action; they are specifically excluded from independent foreign relations, from maintaining an army or navy, from interfering with money, and from disrupting contracts or imposing tariffs. 6. Federal and state laws operate in parallel or as “coordinate” powers, each applying directly to individual citizens, rather than acting primarily through or with dependence on one another. This “coordinate” method applies only to the “vertical” division of powers between federal and state governments, not to the “horizontal” or “functional” division of federal powers into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The latter “separation of powers” is made in such a form as to deliberately keep the three branches mutually dependent on one another, so that no one of them can step forth—excepting the executive in emergencies—as a full-fledged authority on its own. This mutual functional dependence within the federal level is considered an assurance of steadiness of the rule of law and lack of arbitrariness; by contrast, obstructionism was feared if there were to remain a relation of dependence upon a vertically separate level of government. Thus the turn to “coordinate” powers, with federal and state operations proceeding autonomously from one another, or what came to be called “coordinate federalism.” This terminology encapsulated the departure from the old confederalism, in which federal government operations had been heavily dependent on the states. AMBIGUITIES OF COORDINATE FEDERALISM IN THE FEDERALISTDespite The Federalist ’s strong preference for coordinate powers, there are important deviations from it. For example, there are “concurrent” or overlapping powers, such as taxation. This, Hamilton says in The Federalist No. 32, necessarily follows from “the division of sovereign power”: each level of government needs it in order to function with “full vigor” on its own (thus allowing the celebratory formulation for American federalism, “strong States and a strong Federal Government”). Coordinate federalism requires, it turns out, some concurrent powers, not just coordinate powers. In practice, the deviations from the “coordinate” theory go farther still. For the militia, the state governments have the competence to appoint all the officers and to conduct the training most of the time, but the federal government is authorized to regulate the training and discipline, as well as to place the militia when needed under federal command (a provision defended by Hamilton in The Federalist No. 29). For commercial law, the states draw up the detailed codes, but the federal power to regulate interstate commerce opened the door to broad federal interference with state codes in the twentieth century. In these spheres there is state authority, but it is subordinated to federal authority—a situation close to the traditional hierarchical model, not to the matrix model sometimes used for the coordinate ideal. While the states are reserved the wider range of powers, the federal government is assigned the prime cuts among the powers. Its competences go to what are usually viewed as core areas of sovereignty—foreign relations, military, and currency—as well as to regulation of some state powers when they get too close to high politics or to interstate concerns. It already formally held most of these competences during the Confederation, but now could carry them out independently of state action. The Federalist Papers advertise this as being the main point of the Constitution: not a fearsome matter of extending the powers of the federal government into newfangled realms, but the unobjectionable matter of rendering its already agreed-upon powers effective. This effectiveness is achieved by adding the key structural characteristic of the modern sovereign state, elaborated by Hobbes in terms not dissimilar to passages in The Federalist : that of penetrating all intermediate levels and reaching down to the individual citizen to derive its authorization and, conversely, to impose its obligations. In the early years after the Constitution, many federal powers remained dependent de facto on cooperation from the states; The Federalist ’s authors worried that the states would use this dependence to whittle away federal powers, and defended the Constitution’s provisions for federal supremacy as a protection against such whittling away. Later it was the states that became more dependent on federal cooperation. There was an undefined potential for developing the powers of the two levels of government in a cooperative or mutually dependent form; in the twentieth century, the federal government developed this into what came to be called “cooperative federalism,” wielding its superior financial resources to influence state policy in the fields of cooperation. USE AND ABUSE OF THE FEDERALISTThe Federalist Papers have been used with increasing frequency as a guide for interpreting the Constitution. Bernard Bailyn (2003) has counted the frequency and found an almost linear progression: from occasional use by the Supreme Court in the years just after 1789 to more frequent use with every passing stage in American history. Much of this use he regards as abuse of the Papers. The notes of Madison on the Constitutional Convention of 1787 are in principle a better source for discovering intention, but are less often used than The Federalist . They are harder to read, are harder to systematize, and have a structure of shifting counterpoint rather than consistent exposition. Moreover, they were just notes of debates where people were thinking out loud, not formal polished documents, and got off to a yawning start: they were kept secret for half a century. The Federalist Papers , while clearer, are often subjected to questionable interpretation. Taking the Papers as gospel shorn from context, the result can be to stand the purpose of the authors on its head. The crux of the problem is the fact that The Federalist Papers were both polemically vigorous and politically prudent. They were intended to promote ratification of a stronger central government as something that could sustain itself, sink deeper roots, and grow higher capabilities over time. In doing so, they often found it expedient to emphasize how weak the Constitution was and portray it as incapable of being stretched in the ways that opponents feared and proponents sometimes quietly wished. They cannot always be taken at face value. To locate the original intention of the Constitution itself, the place to start would not be The Federalist Papers , but—as Madison did in The Federalist No. 40—the authorizing resolutions for the Constitutional Convention. There one finds a clear and repeated expression of purpose, namely, to create a stronger federal government, and specifically to “render the federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union” (Madison 1788). Next one would have to look at the brief statement of purpose in the preamble of the Constitution. There, the lead purpose is “in Order to form a more perfect Union,” followed by a number of more specific functional purposes understood to be bound up with a more perfect union. The intention of the wording of the Constitution would be found by looking at the Committee on Style at the Constitutional Convention, a group dominated by centralizing federalists. It took the hard substance of the constitutional plan that had been agreed upon in the months of debate, and proceeded to rewrite it in a soft cautious language, restoring important symbolic phrases of the old confederation in order to assuage the fears of the Convention’s opponents. It helped in ratification, but at the usual cost of PR: obfuscation. Theorists of nullification and secession, such as Calhoun , would later cite the confederal language as proof that each state still retained its sovereignty unchanged. The original purpose of The Federalist Papers is the least in doubt of the entire series of documents: it was to encourage ratification and answer the critics who argued the Constitution was a blueprint for tyranny. As such, it was prone to carry further the diplomatic disguises already introduced by the Committee on Style. The authors, particularly Hamilton, argued repeatedly that, if anything, the government proposed by the Constitution would be too weak, not too strong. They said this with a purpose, not of restraining it further—as would be done by taking their descriptions of its weaknesses as indications of original intent—but of enabling its strengths to come into play and get reinforced by bonds of habit. Hamilton in practice opposed “strict constructionism” regarding federal enumerated powers; he generally emphasized the Elastic (“necessary and proper”) Clause in the 1790's. But in The Federalist Papers , Hamilton in No. 33 justifies the Elastic and Supremacy Clauses in cautious, defensive, polemical fashion, denying any elastic intention but only the necessity of defending against what he portrays as the main danger: that of a whittling away of federal power by the states. Madison in No. 44 is slightly more expansive, arguing the necessity of recurrence in any federal constitution to “the doctrine of construction or implication” and warning against the ruinously constrictive construction that the states would end up applying to federal powers in the absence of the Elastic Clause. The logical implication was that either one side or the other—either the federal government or the states—must dominate the process of construing the extent of federal powers, and his preference in 1787–88 was for the federal government to predominate. In The Federalist , he warned against continuing dangers of interposition by the states against federal authority; at the Convention, he had advocated a congressional “negative” on state laws, that is, a federal power of interposition against state laws, as the only way of preventing individual states from flying out of the common orbit. While a legislative negative was rejected at the Convention, a judicial negative was later achieved in practice by the establishment of judicial review under a Federalist-led Supreme Court. Hamilton in The Federalist Nos. 78 and 80 provided support for judicial review, arguing—in defensive form as ever—that it was needed for preventing state encroachments from reducing the Constitution to naught. The Elastic Clause was a residuum at the end of the Constitutional Convention flowing from the original pre-Convention resolutions. The resolutions called for powers “adequate to the exigencies of the Union”; the Convention met and enumerated the federal powers and structures that it could specifically agree on, then invested the remainder of its mandate into the Elastic and Supremacy Clauses, in which the Constitution makes itself supreme and grants its government all powers “necessary and proper” for carrying out the functions it specifies. There is a direct historical line in this, extending afterward to Hamilton’s broad construction of the Elastic Clause in the 1790's. From beginning to end, the underlying thought is dynamic, to do all that is necessary for union and government. The static, defensive exegesis of the Elastic Clause in The Federalist Papers , and in subsequent conceptions of strict construction, is implausible. THE FEDERALIST AND THE GLOBAL SPREAD OF MODERN FEDERATIONThe success of the modern federation in the United States after 1789 made it the main norm for subsequent federalism. The Federalist Papers provided the template for federation building; Hamilton was celebrated as its greatest evangelist. Switzerland reformed its confederation in 1848 and 1870 along the lines of modern federation. The new Latin American countries also often adopted federal constitutions in this period, although their implementation of federalism, like that of democracy itself, was sketchy. After 1865, several British emigrant colonies adopted the overall model of modern federation: first the Canadian colonies (despite using the name “confederation”), then the Australian ones (using “commonwealth”), then South Africa (using “union”; there the ideological role of Hamilton and The Federalist was enormous, and the result was almost a unitary state). After 1945, several countries emerging out of the British dependent empire, such as India and Nigeria, adopted variants of modern federation. Defeated Germany and Austria also adopted federal constitutions. Later, other European and Third World countries also federalized their formerly unitary states. The process is by no means finished. Enumerating all the countries that had developed federal elements in their governance, Daniel Elazar concluded in the 1980's that a “federal revolution” was in process. Once modern federation was known as a solution to the limitations of confederation, there has been less tolerance for the inconsistencies of confederation. Confederalism was a compromise between the extremes of separation and a unitary centralized state, splitting the difference; modern federation is more like a synthesis that upgrades both sides. What in previous millennia could be seen in confederalism as a lesser evil and a reasonable price to pay for avoiding the extremes, after 1787 came to seem like a collection of unnecessary contradictions: and if unnecessary, then also intolerable, once compared to what was available through modern federation. The Federalist Papers have themselves been the strongest propagators of the view that confederalism is an inherently failed system. They made their case forcefully, not as scholars but as debaters for ratifying the Constitution. Their case was one-sided but had substance. They showed that confederation, even when successful, was working on an emergency basis, or else on a basis of special fortunate circumstances or external pressures. They offered in its place a structure that could work well on an ordinary systematic basis, without incessant crises or fears of collapse or dependence on special circumstances. In recent years, it has been argued that Swiss confederalism was an impressive success, and so in a sense it was, holding together for half a millennium. Yet half a century after modern federation was invented in the United States, the Swiss found their old confederal system a failure and replaced it with one modeled along the lines of the modern federal one. The description of the old Swiss confederation as a failure became a commonplace; it entered into the realm of patriotic Swiss conviction. The judgment looks too harsh when the length of the two historical experiences are viewed side by side, yet has carried conviction in an evolutionary sense, as the cumulative outcome of historical experience. After the Constitution and The Federalist Papers , confederalism could not remain as successful in terms of longevity as it had been previously; the historical space for it shrank, while new and larger spaces opened up for modern federation. The advance of technology worked in the same direction, increasing interdependence within national territories and making localities more intertwined. Despite the shrinkage of space for confederation within national bounds, confederation took on new force on another level. The American Union’s survival of the Civil War and consolidation afterwards gave a further impetus to discussion of modern federation, understood not only as a static technique for more sophisticated government within a given space, but also as a dynamic method of uniting people across wider spaces, in order to meet the needs of modern technological progress and the growth of interdependence. International federalist movements emerged after 1865, taking The Federalist Papers as their bible. They gained influence in the face of the world wars of the 1900's, feeding into the development of international organizations ranging from very loose and weak ones to integrative alliances and confederations such as NATO and the EU. The missionary ideology of The Federalist , used by its proponents for pummeling confederation, led on the international level to new confederations. When some (such as the League of Nations) were viewed as failures, further missionary use of The Federalist fed into the formation of still more confederations, often stronger and better conceived but confederations nonetheless, even if (as in the case of the EU) with a genetic plan of evolving into a federation. Federation seemed no less necessary but more difficult than federalist propagandists had suggested. Reflection on this situation led to an academic school of integration theory in the 1950's and 1960's, which treated functionalism and confederation as necessary historical phases in integration; in the neofunctionalist version of the theory it would lead eventually to federation, and in the version of Karl Deutsch it need not move beyond a “pluralistic security-community.” The work of Deutsch tied in with the view that confederation had been a greater success historically than was usually credited; to prove the success of the American confederation, Deutsch and his colleagues cited Merrill Jensen, an historian highly critical of The Federalist and friendly to the Anti-Federalists or Confederalists. Jensen argued that the Articles of Confederation had been a success, contrary to the American patriotic story that paralleled the Swiss one in condemning the confederalist experience. The relevance of The Federalist Papers was seen in this new literature as minimal, except at the final stages of a process that was only beginning and that the Papers themselves mystified as a matter of tactical necessity for getting a difficult decision made. Their exaggerations of the defects of confederalism were highlighted; their argument that only federation would “work” was seen as both a mistake and a diversion from the direction that progress would actually need to take in this era. It was only their normative orientation that was seen as helpful. The very success of The Federalist Papers had led to their partial eclipse. Nevertheless, their eclipse on the supranational level may not be permanent, and their influence on the level of national constitutionalism has remained enormous throughout. | Bernard Bailyn, (New York: Knopf, 2003); Madison, James, 40 (New York Pachet, January 18, 1788); Clinton Rossiter ed., (New York: Signet, 1999). | Last updated: 2006 SEE ALSO: Anti-Federalists ; Federalists ; Hamilton, Alexander ; Madison, James - Historical Events

- This page was last edited on 4 July 2018, at 21:08.

- Content is available under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike unless otherwise noted.

- Privacy policy

- Federalism in America

- Disclaimers

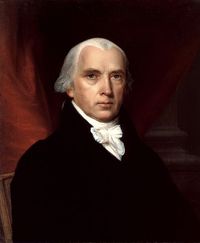

The Federalist Papers | Overview & AuthorsAdditional info. Avery Gordon has experience working in the education space both in and outside of the classroom. He has served as a social studies teacher and has created content for Ohio's Historical Society. He has a bachelor's degree in history from The Ohio State University. Nate Sullivan holds a M.A. in History and a M.Ed. He is an adjunct history professor, middle school history teacher, and freelance writer. Table of ContentsJames madison, the shaping of the american constitution, james madison's federalist papers, the federalist papers' legacy, lesson summary, what is the 51st federalist paper about. The 51st Federalist paper is written by James Madison. In this essay, Madison outlines the importance of checks and balances and discusses how they would be implemented in the Constitution. How many Federalist Papers did James Madison write?James Madison wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers. This is second to Alexander Hamilton who wrote a total of 51. What does federalist 39 say?Federalist paper 39 outlined what a republic is. Madison emphasized in this essay that the foundation of republic is the authority of the people. Did James Madison contribute to The Federalist Papers?Yes. James Madison wrote 29 of the 85 Federalist Papers. Some of his more significant essays were Federalist paper #10, #19, #39, and #51. How many Federalist Papers did each person write?Alexander Hamilton wrote the most, totaling at 51 of the 85 essays. James Madison wrote 29 and John Jay wrote 5. James Madison was born in 1751 and would go on to become the fourth President of the United States of America, a position he held from 1809-1817. Despite rising to the highest office in the land, Madison's most significant contributions to American history came years before being sworn in as President. As a founding father, Madison played a critical role in the creation of the United States Constitution, notably through his contributions to the influential Federalist Papers . As a member of congress he helped draft the Bill of Rights, which include the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Due to all his contributions he earned the nickname "Father of the Constitution." Though he did object to this moniker, stating it was not 'the off-spring of a single brain,' but 'the work of many heads and many hands.' James Madison is known as the Father of the Constitution | | To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member. Create your account Following the Revolutionary War, which ended in 1783, the US government was formed under the Articles of Confederation , which had been ratified two years earlier. Before the Constitution, The Articles of Confederation served as the document that outlined the role and function of the federal government. Under this document, the United States was truly more of a confederation, or alliance, of sovereign states than it was a united country. The states were given much of the power and could mostly operate autonomously. The central government, such as there was, mostly served a body that dealt with foreign affairs such as declaring wars, signing treaties, forming alliances, and managing relations with Native Americans. The problematic nature of such a weak federal government quickly became apparent to many. Thus, the fight for a new constitution began. The Debate: Federalist vs Anti-FederalistThe struggle for a new constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation was fought between two sides, Federalists and Anti-Federalists Federalists Alexander Hamilton, prominent Federalist and co-author of the Federalist Papers | | The core of Federalists' beliefs was their support for a strong central government. Leaders among this movement include James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Ben Franklin, and John Jay . Some of their main arguments included: - A strong central government was needed to fend off attacks from foreign nations. Under the Articles of Confederation, there was no Federal Army and Federalists thought this left them vulnerable to attack

- Without a new Constitution, the central government had no means to fund projects because Articles of Confederation did not give it the power to collect taxes.

- A strong federal government was necessary for the survival of the country. Federalists feared that under the current circumstances the country was liable to in-fighting between states that could lead to a separation of the union.

Anti-FederalistsThe core belief of Anti-Federalist was the support for a strong state level government. Its prominent leaders included John Hancock, Patrick Henry, and George Mason. Some of their main arguments included: - A strong central government could be tyrannical, becoming something that resembled the British Monarchy.

- Anti-Federalists feared that federal politicians could become an aristocratic class that was to far removed from the will of the common people.

- Anti-Federalist were staunchly against any new constitution that didn't include a bill of rights to protect citizens against the possibility of a tyrannical government.

The Federalist PapersHere are a few key facts about the Federalist Papers. | Who authored the Federalist Papers? | The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay from October 1787 to May 1788. | | How many Federalist Papers are there? | There were 85 essays. Each essay outlined a different argument in support of a new constitution that created a strong central government. | | Who wrote most of the Federalist Papers? | Of the 85 essays, 51 were written by Hamilton, 29 by James Madison, and 5 by John Jay. All of the essays, however, were published under the pseudonym Publius in New York newspapers. | | What did James Madison write? | James Madison wrote Federalists Papers 10, 14, 18-20 , 37-49, 50-52 , 53, 54-58 , 62-63. | John Jay, co-author of the Federalist Papers | | James Madison's most significant contributions come from papers #10, #19, #39, and #51 Federalist Paper #10Federalist Paper #10 built further upon #9 written by Hamilton, and was titled The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection . This essay is about the dangers of political factions. His main argument was that a representative republic, rather than a direct democracy, could curb the negative consequences of political factions, which he viewed as inevitable and virtually impossible to eliminate entirely. This can be seen in the following excerpt from #10 "If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote. It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the Constitution. " So his argument is that the republican principles of the new constitution will shield against the threats of political factions. Federalist Paper #19Federalist paper #19 is titled The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union . This essay continued the topic of how a confederation that has a weak central government and strong smaller states is prone to in-fighting that weakens the whole and can even break it apart completely. Madison draws comparisons to the contemporary state of Germany (Holy Roman Empire). This can be seen in the following quote: "The history of Germany is a history of wars between the emperor and the princes and states; of wars among the princes and states themselves; of the licentiousness of the strong, and the oppression of the weak; of foreign intrusions, and foreign intrigues; of requisitions of men and money disregarded, or partially complied with; of attempts to enforce them, altogether abortive, or attended with slaughter and desolation, involving the innocent with the guilty; of general inbecility, confusion, and misery." The point Madison is making is that confederations are easily susceptible to internal strife. They are constantly at war with themselves as states struggle for dominance over one another. He points out that this leaves them vulnerable to attack from foreign powers. Ultimately he concludes in this essay that a strong central government is needed to protect the Union from breaking apart. Federalist Paper #39Federalist Paper 39 is titled The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles . In this essay, Madison discusses what a republic is and how the United States would look as a republic under the new constitution. He emphasizes that the people are the foundation of a republic, that elected officials derive their power from the people, and that leaders of the republic must have term limits. The following quote highlights Madison's belief that it is the authority of people that matters and it is they who will ratify the Constitution. "It is to be the assent and ratification of the several States, derived from the supreme authority in each State, the authority of the people themselves. The act, therefore, establishing the Constitution, will not be a NATIONAL, but a FEDERAL act." Madison also emphasizes the distinction between national and federal. Federal implies a union of states where national implies that there is just one singular nation that is whole and not made up of many states. This was an important distinction for Madison to get across to assuage anti-federalist fears that a central government would become tyrannical. Madison is making sure that people know that just because the central government will be strengthened under this new constitution that doesn't mean the country will lose its identity of being a union. Federalist Paper #51Federalist Paper 51 is titled The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments . This essay goes over the importance of checks and balances across the different departments of government. It also highlights how that would look in the United States if the constitution were to be ratified. One explanation is given by Madison in the following excerpt. "In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates. The remedy for this inconveniency is to divide the legislature into different branches; and to render them, by different modes of election and different principles of action, as little connected with each other as the nature of their common functions and their common dependence on the society will admit. It may even be necessary to guard against dangerous encroachments by still further precautions. As the weight of the legislative authority requires that it should be thus divided, the weakness of the executive may require, on the other hand, that it should be fortified. " Here he explains that in a republic the legislature, by nature, has the most power and the executive office has the least. To counterbalance that the U.S. would divide the legislature in two while keeping the executive branch consolidated. This explains why congress is divided into two houses, the House of Representatives and the Senate. The Federalist papers were printed in newspapers in New York in an effort to convince citizens to ratify the Constitution. Afterward, they were re-printed across the states as the ratification process continued. Eventually the Constitution was ratified in 1788. While New York did vote to ratify the Constitution, it's unclear how much of an effect the Federalist Papers played, but that hasn't diminished their legacy. The Federalist Papers, which didn't earn that nickname until the 20th century, are widely considered to be some of the most significant publications of political philosophy. They serve to explain the reasoning and intent behind the Constitution for modern day Americans. James Madison would go on to become the fourth President of the United States, however, his most important accomplishments happened well before he was inaugurated. Known as the "Father of the Constitution," Madison played a critical role in both determining the content of the Constitution and getting it ratified in 1788. After the Revolutionary War, the United States was still under the Articles of Confederation . The predecessor to the Constitution, the Articles of Confederation, gave almost all the power to the states leaving only a few foreign policy duties to the central government. Many quickly realized that such a weak central government was tenable for the Union's survival. A divisive debate began between the Federalists , who were in favor of a strong central government, and Anti-Federalists , who believed the majority of the power should remain with the states. James Madison was a Federalist and, alongside Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, he wrote the Federalist Papers (which didn't earn that nickname until the 20th century). These were a series of essays that outline the importance of a strong central government, how it should be implemented, and why New Yorkers should vote for the ratification of the Constitution . The essays were published under the pseudonym Publius in New York newspapers. Key essays written by Madison include Federalist Paper 10 (which dealt chiefly with political factions), Federalist Paper 39 (which explores what a republic is and how it should look), and Federalist Paper 51 (which goes over the importance of checks and balances). James Madison: Brilliant Thinker and Contributor to the Federalist PapersJames Madison was America's shortest president, standing only 5 feet 4 inches tall, but what he lacked in physical presence, he made up for in mental fortitude. The man was brilliant. After all, he wrote the U.S. Constitution. One of the authors of the Federalist Papers, James Madison. | | He also wrote something else. He was the author of many of the essays in the Federalist Papers , a collection of 85 political essays arguing for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. They also promoted the ''Federalist'' political philosophy, which emphasized a strong central government. Along with James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay authored the essays comprising the Federalist Papers . In this lesson we will be learning about the role Madison played in authoring the Federalists Papers . Let's dig in!  Federalism vs. Anti-Federalism and the Federalist PapersBefore we get into James Madison's actual essays, we first need just a little bit of context. It's important that we understand exactly what was going in regard to the Federalism vs. Anti-Federalism controversy. Established under a document called the Articles of Confederation , America's first government proved to be pretty ineffective. The government did not have the power it needed to raise revenue and adequately administer affairs. Because of this, a new ''federal'' style government was proposed under the U.S. Constitution. Those who supported the implementation of a new federal government became known as ''Federalists''. They favored a strong, central government, complete with a national bank. Anti-Federalists, on the other hand, feared that under the U.S. Constitution, the government would have too much power. The Articles of Confederation. | | The numbered essays that make up the Federalists Papers were all written under the pseudonym ''Publius'' . However, historians are in generally agreement over which essays were written by which authors. It is believed James Madison wrote 28 essays, compared with Alexander Hamilton's 52, and John Jay's five. Most of the essays were written between October 1787 and August 1788. Some essays are typically regarded as more influential than others. When these essays were first published in 1788, they were titled The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, as Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787 . It was not until the 20th century that the term Federalist Papers began to see widespread use. A collection of 85 political essays called the Federalist Papers. | | James Madison's Federalist EssaysJames Madison was the author of Federalist No. 10 , which is often regarded as the most influential of the entire collection. This essay was formally titled The Same Subject Continued: The Utility of the Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection . In this essay, Madison expands upon Alexander Hamilton's Federalist No. 9, which discusses political factions and the need for unity. Madison believed that political factions were inevitable, and he was especially concerned about political splintering along class lines, or in other words, between the ''haves'' and the ''have-nots''. Madison warned than in a decentralized pure democracy, the have-nots might band together, initiating a sort of ''mob rule'' that had the potential to become unstable. (One only needs to consider the French Revolution to see this in action.) The solution then, Madison argues, is not pure democracy, but a representative republican government like the one outlined in the U.S. Constitution. Madison argues that representative government tends to be more stable than direct democracy. Federalist No. 18-20 , The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union address the failures of the government under the Articles of Confederation. In these essays, Madison makes a case for why a national, federal government under the U.S. Constitution is needed to replace the confederation. In Federalist No. 39 , The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles , Madison addresses the nature or republican government. He calls into question whether America should have a national quality, or whether power should be held within the individual states. The issue of state's rights vs. the federal government is a major theme in this important essay. Madison argues for strong national government and argues for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Federalist No. 51 , The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments is another important essay written by Madison. This essay concerns systems of ''checks and balances'' through which the power of the national government should be limited. Madison argues that the powers of the national government should be separated so as to safeguard liberty for the people. The separation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches that we observe in American government to this day is the direct product of Madison's thinking regarding ''checks and balances''. Madison wrote other essays as well, but these are some of his noteworthy ones. In June 1788, the Federalists won the day, so to speak, when the U.S. Constitution was ratified. It replaced the Articles of Confederation and went into effect in March 1789. Let's review. - The Federalist Papers were a collection of 85 political essays arguing for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the creation of new national and centralized government.

- America's first government was a confederation established under the Articles of Confederation . This government was weak and ineffective, and James Madison and other Federalists called for it to be replaced.

- Federalists argued for a strong, centralized government, while Anti-Federalists called for a more limited government in which the states held power.

- The Federalists Papers were all written under the pseudonym ''Publius'' .

- Federalist No. 10 is often regarded as the most influential of the entire collection. It deals with the issue of political factions and presents representative government as the solution to disunity.

- In Federalist No. 39 Madison addresses the nature or republican government. He questions whether power should be consolidated at a national level or among the states.

- In Federalist No. 51 Madison argues for a system of ''checks and balances'' within the national government.

Register to view this lessonUnlock your education, see for yourself why 30 million people use study.com, become a study.com member and start learning now.. Already a member? Log In Resources created by teachers for teachersI would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline. The Federalist Papers | Overview & Authors Related Study MaterialsBrowse by Courses- Praxis Core Academic Skills for Educators: Reading (5713) Prep

- Praxis Core Academic Skills for Educators - Writing (5723): Study Guide & Practice

- ILTS TAP - Test of Academic Proficiency (400): Practice & Study Guide

- US History: High School

- Praxis Sociology (5952) Prep

- Praxis Social Studies: Content Knowledge (5081) Prep

- High School World History: Tutoring Solution

- High School World History: Homework Help Resource

- History 101: Western Civilization I

- Effective Communication in the Workplace: Certificate Program

- Effective Communication in the Workplace: Help and Review

- Western Civilization I: Help and Review

- Political Science 101: Intro to Political Science

- Western Civilization I: Certificate Program

- UExcel Workplace Communications with Computers: Study Guide & Test Prep

Browse by Lessons- Federalist Papers | Summary, Authors & Impact

- The Federalist Papers | Definition, Writers & Summary

- James Madison and Alexander Hamilton

- Federalist John Jay | Biography & Facts

- Federalist Papers Lesson for Kids: Summary & Definition

- Triglyph Definition, Origin & the Doric Corner Conflict

- Pythagoras | Biography, Facts & Impact

- Prometheus God in Greek Mythology | Story & Symbol

- Pseudo-Dionysius Biography, Writings & Influence

- Mark Antony of Rome | Overview, Biography & Death

- Protogeometric Pottery Overview & Examples

- Dante Alighieri | Poems, Philosophy & Works

- Incan Empire | Map, Culture & Religion

- Cosimo de' Medici | Biography, Death & Legacy

- Giovanni Boccaccio | Biography, Decameron & Other Writings

Create an account to start this course today Used by over 30 million students worldwide Create an account Explore our library of over 88,000 lessons- Foreign Language

- Social Science

- See All College Courses

- Common Core

- High School

- See All High School Courses

- College & Career Guidance Courses

- College Placement Exams

- Entrance Exams

- General Test Prep

- K-8 Courses

- Skills Courses

- Teacher Certification Exams

- See All Other Courses

- Create a Goal

- Create custom courses

- Get your questions answered

The Federalist Papers (1787-1788) Additional TextAfter the Constitution was completed during the summer of 1787, the work of ratifying it (or approving it) began. As the Constitution itself required, 3/4ths of the states would have to approve the new Constitution before it would go into effect for those ratifying states. The Constitution granted the national government more power than under the Articles of Confederation . Many Americans were concerned that the national government with its new powers, as well as the new division of power between the central and state governments, would threaten liberty. In order to help convince their fellow Americans of their view that the Constitution would not threaten freedom, James Madison , Alexander Hamilton , and John Jay teamed up in 1788 to write a series of essays in defense of the Constitution. The essays, which appeared in newspapers addressed to the people of the state of New York, are known as the Federalist Papers. They are regarded as one of the most authoritative sources on the meaning of the Constitution, including constitutional principles such as checks and balances, federalism, and separation of powers. Related Resources James MadisonNo other Founder had as much influence in crafting, ratifying, and interpreting the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights as he did. A skilled political tactician, Madison proved instrumental in determining the form of the early American republic.  Alexander HamiltonA proponent of a strong national government with an “energetic executive,” he is sometimes described as the godfather of modern big government.  John Jay epitomized the selfless leader of the American Revolution. Born to a prominent New York family, John Jay gained notoriety as a lawyer in his home state.  Federalist 10Written by James Madison, this essay defended the form of republican government proposed by the Constitution. Critics of the Constitution argued that the proposed federal government was too large and would be unresponsive to the people.  Federalist 51In this Federalist Paper, James Madison explains and defends the checks and balances system in the Constitution. Each branch of government is framed so that its power checks the power of the other two branches; additionally, each branch of government is dependent on the people, who are the source of legitimate authority.  Federalist 70In this Federalist Paper, Alexander Hamilton argues for a strong executive leader, as provided for by the Constitution, as opposed to the weak executive under the Articles of Confederation. He asserts, “energy in the executive is the leading character in the definition of good government.  Would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?Federalist or Anti-Federalist? Over the next few months we will explore through a series of eLessons the debate over ratification of the United States Constitution as discussed in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers. We look forward to exploring this important debate with you! One of the great debates in American history was over the ratification […]  U.S. Constitution.netFederalist papers’ role in constitution. The formation of the United States Constitution was a pivotal moment in history, reflecting the deep commitment of the Founding Fathers to create a balanced and enduring system of governance. The Federalist Papers, written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, played a crucial role in advocating for this new framework. These essays provided detailed arguments for a strong central government, checks and balances, and the protection of individual liberties. Historical Context and PurposeThe Articles of Confederation, though groundbreaking, revealed many weaknesses that hindered the viability of a unified nation. Congress couldn't levy taxes, leading to a financially weak federal government. Each state operated almost independently, making commerce a chaotic affair. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was filled with lively debates and differing opinions. Federalists pushed for a strong central government, arguing that the survival of the nation depended on a robust framework that could address common needs and settle disputes among states. Antifederalists worried about losing the hard-won liberties they fought for during the Revolution. Alexander Hamilton, determined to sway public opinion in favor of the new Constitution, enlisted John Jay and James Madison. The trio adopted the pseudonym "Publius," inspired by a Roman general who helped establish the Roman Republic. The Federalist Papers were born from this alliance, starting with Hamilton's first essay in the Independent Journal on October 27, 1787. The essays were a vigorous defense of the new Constitution, explaining its provisions and benefits. John Jay contributed five essays focusing on foreign policy and the limitations of the Articles of Confederation before dropping out due to illness. Madison, nicknamed "Father of the Constitution," wrote 29 essays, including the crucial Federalist 10, which tackled the issue of factions and argued that a large republic could better manage diverse interests. Hamilton penned 51 essays, exploring the weaknesses of the Articles, stressing the need for a unified nation capable of defending itself and thriving economically, and arguing for the critical issue of taxation. The Federalist Papers also explored the concept of checks and balances, emphasizing the careful division of power among three branches of government. Federalist 51, written by Madison, famously said, If men were angels, no government would be necessary, underscoring the need for internal and external controls within the government to prevent abuse of power. Despite the articulate arguments, the Federalist Papers saw limited circulation outside New York, and many delegates remained unconvinced. Yet, a narrow majority eventually voted for ratification, with a promise of future amendments, leading to the Bill of Rights. The Federalist Papers' long-term impact is awe-inspiring, serving as key references for understanding the Constitution's intentions and revealing the Founders' intent behind federalism, the separation of powers, and individual liberties. George Washington, though not an essayist, played a subtle yet significant role, believing the Federalist Papers were essential in educating the public about the new government's principles. The Federalist Papers remain a timeless resource for anyone seeking to understand the foundation of American governance, reflecting a deep commitment to creating a government that balances necessary powers with the protection of individual rights.  Key Arguments in the Federalist PapersThe Federalist Papers laid out several paramount arguments advocating for the newly proposed Constitution, addressing concerns and misconceptions while explaining the necessity of a robust federal framework. One of the primary assertions was the necessity of a strong central government. The existing Articles of Confederation had created a government too weak to address the challenges facing the new nation. Alexander Hamilton articulated the failures of the Articles of Confederation, such as their inability to enforce laws, regulate commerce, or levy taxes. These deficiencies posed a risk to the nation's stability and its ability to defend itself and maintain economic prosperity. A recurring theme in the Federalist Papers is the concept of checks and balances within the new government structure. The Founders were acutely aware of the dangers of tyranny, whether from an individual despot or a majority faction. James Madison, in Federalist No. 51, famously encapsulated this necessity with the assertion, If men were angels, no government would be necessary. The Constitution's framework ensured that no single branch of government could consolidate unchecked power. Madison's Federalist No. 10 elucidated the dangers of factionalism and how an extended republic could mitigate these dangers. Madison argued that factions were inevitable in any society. However, the brilliance of a large republic lay in its ability to dilute factional influences. By expanding the sphere, it became less likely that a single faction could dominate the political landscape. This large republic would offer a greater diversity of parties and interests, making it more challenging for any one group to gain a majority and impose its will on others. - Federalist No. 10 and No. 51 stand out for their detailed treatment of these principles.

- Federalist No. 10 directly challenges Montesquieu's notion that true democracy could only survive in small states.

- Federalist No. 51 further explored the mechanisms necessary to ensure that the branches of government could effectively check each other, thus protecting individual liberty from the risks of consolidated power.

Hamilton's essays also explored deeply the practical aspects of a functional government. In Federalist No. 23 through No. 25 , he argued for the necessity of a federal army, outlining why a strong central government needed the capability to defend its citizens adequately. Although these essays were written to influence immediate public opinion towards ratification of the Constitution, their insights possess lasting significance. They form a central reference for legal scholars, judges, and anyone seeking to understand the philosophical underpinnings of American governance.  Judicial Interpretation and the Rule of LawFederalist No. 78 , written by Alexander Hamilton, holds distinct importance in understanding the judiciary's critical role within the framework of the United States Constitution. This essay examines the imperative of an independent judiciary to safeguard the principles of the Constitution and ensure the rule of law. Hamilton posits that the judiciary must be an "intermediate body between the people and their legislature," tasked with ensuring that the will of the people, as enshrined in the Constitution, prevails over any legislative enactments that conflict with it. Hamilton argues that the judiciary must possess a distinct form of independence to perform its duty effectively. He emphasizes that judges should hold their offices during good behavior to protect them from external pressures and influence. This tenure would grant them the necessary insulation from political factions and undue influence, allowing them to make decisions based solely on constitutional principles and legal merits. By doing so, the judiciary would act as a guardian of the Constitution, protecting individual rights and preventing the encroachment of tyranny from any branch of government. One of the fundamental assertions in Federalist No. 78 is the principle of judicial review. Hamilton contends that when laws enacted by the legislature contravene the Constitution, it is the judiciary's duty to declare such laws void. He articulates that the Constitution is the "fundamental law" and asserts that it embodies the will of the people, which transcends ordinary legislative acts. Thus, judges ought to prioritize the Constitution in their rulings, interpreting its provisions faithfully to preserve the rule of law. Hamilton further stresses the importance of the judiciary in maintaining the balance of power among the three branches of government. He elucidates how the judiciary serves as a check on the other branches, ensuring that neither the executive nor the legislative branches exceed their constitutional authority. By interpreting the Constitution and invalidating unconstitutional laws, the judiciary upholds the principle of checks and balances, which is essential to preserving a functional and fair government. Federalist No. 78 also touches on the inherent limitations of the judiciary's power. Hamilton recognizes that the judiciary, as the "least dangerous" branch, lacks the force of the executive and the financial control of the legislature. Its power rests solely on judgment and the effective interpretation of laws. The impact of Hamilton's arguments in Federalist No. 78 reverberates through American judicial history. The principle of judicial review established in Marbury v. Madison (1803) finds its roots in Hamilton's articulation. Chief Justice John Marshall's landmark decision in Marbury v. Madison affirms Hamilton's vision, cementing the judiciary's role as the arbiter of constitutional interpretation. Through this decision, the judiciary asserted its authority to review and nullify laws that contravened the Constitution, thereby ensuring that constitutional principles remain supreme. 1 In the broader context of constitutional interpretation, Federalist No. 78 remains a cornerstone. It underscores the necessity of a judiciary that can interpret the Constitution free from external pressures and biases. The essay's insights continue to guide judicial philosophy, emphasizing the judiciary's role in protecting individual rights and maintaining the rule of law against potential overreach by the legislative or executive branches. Hamilton's vision in Federalist No. 78 exemplifies the brilliance of the Founding Fathers in crafting a system of governance that preserves liberty while ensuring effective government. His advocacy for an independent judiciary and judicial review demonstrates the depth of thought and foresight that went into the Constitution.  Impact on Ratification and Subsequent AmendmentsThe influence of the Federalist Papers on the ratification debates, particularly in New York, was significant. New York was a battleground of fierce political contention where Anti-Federalist sentiments were deeply entrenched. Critics of the proposed Constitution feared that it concentrated too much power in the hands of a centralized government, potentially trampling on the liberties won during the American Revolution. 1 The essays by Hamilton, Madison, and Jay—published under the collective pseudonym "Publius"—aimed to counter these arguments, presenting a reasoned case for ratification. As the essays circulated through New York newspapers, they became the focus of public debates. They served as an educational tool, clarifying the intentions behind various constitutional provisions. Hamilton's essays explained the necessity of federal taxing power and a standing military, addressing concerns over economic stability and national defense. Madison's writings on the separation of powers and the dangers of factionalism provided reassurance that the Constitution was designed to protect individual liberties. Despite the compelling nature of the Federalist Papers, their initial impact on New York's ratification process was nuanced. The essays did not instantly convert Anti-Federalists but succeeded in shaping the discourse and providing Federalists with a robust framework to defend the new Constitution. The New York ratifying convention in 1788 was a critical juncture. Anti-Federalists held a majority, and securing ratification seemed an uphill battle. Nonetheless, the arguments put forth by the Federalist Papers played a strategic role. Delegates like Hamilton and Madison used these writings as a foundation to argue their points, underscoring that a stronger federal government was indispensable for unity and stability. A turning point came with the promise of future amendments. Recognizing the pervasive concerns about individual liberties and potential government overreach, Federalists agreed to support a Bill of Rights as a condition for ratification. 2 This compromise was pivotal, mollifying skeptics by ensuring that the first ten amendments would safeguard fundamental rights. The persuasive power of the Federalist Papers, combined with the promise of a Bill of Rights, led to a narrow victory for the Federalists in New York. This state's ratification aided in securing the Constitution's broader national acceptance, aligning with the necessary momentum to establish a strong federal framework. The adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 reflected many of the concerns debated during the ratification process. James Madison, recognizing the anxieties articulated by the Anti-Federalists, took the lead in drafting these amendments, addressing fears that the new government might become too powerful and encroach on individual freedoms. The Federalist Papers significantly impacted the ratification debates by addressing the Anti-Federalists' concerns and paving the way for a balanced approach to governance that included the Bill of Rights. The collaboration and writings of Hamilton, Madison, and Jay have left an indelible mark, ensuring that the Constitution remains a living testament to the principles of liberty and justice.  Enduring Legacy and Modern RelevanceThe Federalist Papers have an enduring legacy that continues to shape the understanding and interpretation of the United States Constitution among legal scholars and within American political theory. These essays have become foundational texts within legal analysis, political science, and education, providing a window into the minds of the Founding Fathers and their vision for the republic. The Federalist Papers maintain their modern relevance through their application in legal contexts. The essays are frequently cited in Supreme Court decisions and legal arguments as authoritative sources that elucidate the Framers' intent. In landmark cases such as Marbury v. Madison and McCulloch v. Maryland , the Supreme Court utilized insights from the Federalist Papers to interpret key constitutional provisions, reinforcing the judiciary's role in checking legislative and executive power. In Marbury v. Madison , Chief Justice John Marshall drew upon Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 to establish the principle of judicial review, asserting the judiciary's duty to declare unconstitutional laws void. 3 This principle, rooted in Hamilton's argument for the primacy of the Constitution over ordinary legislative acts, underscored the judiciary's role as a guardian of the Constitution. The arguments laid out in the Federalist Papers continue to inform debates about the balance of power between state and federal governments. Madison's Federalist No. 10 and No. 51 are frequently referenced in discussions about federalism and the separation of powers, providing a theoretical framework that guides contemporary interpretations of federal authority and state sovereignty. Beyond the legal realm, the Federalist Papers are indispensable in academic circles, particularly in political science and history. They serve as key texts for understanding the philosophical underpinnings of the United States' political system, examining essential concepts such as: - Republicanism

- Representative democracy

- Safeguards against tyranny