The Cabrini Blog

Filter Your View:

Narrow by Topic

- Activities and Events

- Just for Fun

- Living on Campus

- Service and Mission

Covid-19 and Critical Thinking

Posted on 5/1/2020 4:48:36 PM

Written by Sharon Schwarze, PhD , from Cabrini's Department of Philosophy and Liberal Studies

The covid-19 crisis is very upsetting to all of us, you and me. It has us upset because we do not know how to anticipate the future -- the world's future and our own personal futures. We can't make plans. Our expectations are thwarted. We are very unhappy not knowing what the future will bring and not knowing what consequences our own actions will bring. We want to have pleasant experiences, not unpleasant ones. But we do not know what to anticipate.

This is because our inductive reasoning that helps us to anticipate the future is confounded. Remember the principle of induction : that the future will be like the past? The problem is that we have never had a past like this! You should also remember that that principle has no non-circular justification. Just because in past the future was like the past does not guarantee that the coming future will also be like the past. And now it isn't. We have never had a corona virus like this one, one that makes people so sick. We do not know what to anticipate and therefore we do not know how to make decisions or to make plans. It makes us anxious and unhappy. To put it another way, we have a present that is sufficiently unlike any recent past such that our ordinary expectations for the future have been upset and we are upset.

So how can critical thinking help us in these times? Certainly, critical thinking cannot make covid-19 and the chaos it is causing go away. What it can do is help us to understand what has happened and suggest ways to cope and improve the current situation. Inductive reasoning is at the heart of the problem – and is the tool our leaders and scientists are using to anticipate and improve the future. They are collecting the traces , that is the marks they find on the world that indicate something (new) is going on. These include the deaths and the number of deaths, the pathogens (germs) they find on those bodies, the bodily changes in those who are sick (difficulty breathing, sore throats, fever), and the places the disease strikes. Then they look for patterns among these traces. They see that people tend to get sick after touching something that the sick person has come in contact with. They need to know the patterns so they can interrupt those patterns and stop the spread of the disease.

They then use induction , namely the three types of inductive reasoning:

- They reason by using generalizations . They see the pattern that older people die from covid-19 more frequently than younger people and draw the generalization that covid-19 is more dangerous to older people or to people with underlying conditions. They generalize that people can catch the disease from people without symptoms, etc. These generalizations are not necessarily universal (they are not about all , but about some ).

- They reason using analogy. They look at past pandemics to see how they spread. They see that this event has similar properties to other pandemics and reason that it will share other properties as well. They look at other corona viruses (they cause the common cold) and examine their known behavior. They reason by analogy that this corona virus will behave somewhat similarly. Of course, they also have to look at where the similarities stop. For example, why does this corona virus kill more people than does the common cold? Microscopic analysis shows some differences. Those differences will help lead to an antidote or vaccine for covid-19.

- They reason using causal reasoning. That is, they reason that the virus covid-19 causes the symptoms that give so much suffering. There is a necessary connection between the virus and the illness. Whenever A happens, B happens. Now we know that not everyone who carries the virus gets sick, but we do know that everyone who carries the virus can pass it on to someone else who will most probably get sick. We do not know exactly why some (lucky) people do not experience symptoms but we do know that the virus is the cause of the disease. (Just as cigarettes cause cancer but not everyone who smokes gets cancer.) We also know that good hygiene and disinfecting can cause the death of the virus. That is just as important for us to know.

We also know using all three of these reasoning processes that a future vaccine is a must for overcoming this scourge. We know that most people who are vaccinated against other diseases do not get those disease or get very light cases of them. That's using generalization and analogy and causal reasoning. We all look forward to that day!!

Now let's use this example to talk more generally about correlations . A correlation is when two events repeatedly happen together, like being exposed to a sick person and later getting sick yourself. Some correlations happen necessarily because, we assume, there is a causal relation between them. If the first event happens then the second event has to happen. E.g., if you are exposed to covid-19 you will get sick or you have a very strong immune system that can fight off this invader. One of those two things has to happen. There is a necessary connection between them.

Some events happen together by accident. These are accidental correlations . There is an accidental correlation between you're being a Cabrini University student and being healthy (at least I hope so). It's not that you couldn't get sick, but you just happen to be both a Cabrini student and not sick. And we hope that there continues to be a fairly high correlation between these two! This distinction is important for understanding causal reasoning. When researchers look for a vaccine, they want to make sure that the vaccine causes the lack of sickness and it is not just an accident that those who received it stayed healthy.

The material in this announcement should help you to understand why inductive reasoning is so important and why critical thinking is so important. We hope that our scientists have good inductive reasoning. They are known for it. Our politicians are not!

You should also keep in mind that inductive reasoning is always about confirmation, not proof. We will have to wait for scientists to confirm that a vaccine works. There is never proof. We can confirm, over and over again, that hand washing and staying away from sick can keep a person healthy. But we cannot prove it. Some people who ignore these prescriptions will not get sick, but they are lucky, not smart. They are not thinking critically.

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- Undergraduate

- Adult and Professional Studies

- Directory <

- Principal Leadership

- Volume 21 (2020-2021)

- Principal Leadership: October 2020

Critical Thinking During COVID: October 2020

In uncertain times, it’s human to react with stress and fear. As school leaders, you’re tasked with making big decisions and providing reassurance to staff, students, and families. Crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic require us to lead by example through critical thinking. Critical thinking is a research-validated tool in crisis management because it helps us sort through information, gain an accurate view of the situation, and make decisions.

Tapping Into Critical Thinking

Critical thinking requires us to dig deep and focus on facts and credible sources. Applying critical thinking skills helps us wade through uncertainty and reach sound conclusions.

As a reference point, consider the “9 Traits of Critical Thinking™” from Mentoring Minds:

- Adapt: I adjust my actions and strategies to accomplish tasks.

- Examine: I use a variety of methods to explore and to analyze.

- Create: I use my knowledge and imagination to express new and innovative ideas.

- Communicate : I use clear language to express my thoughts and to share information.

- Collaborate: I work with others to achieve better outcomes.

- Inquire: I seek information that excites my curiosity and inspires my learning.

- Link: I apply knowledge to reach new understandings.

- Reflect: I review my thoughts and experiences to guide my actions.

- Strive: I use effort and determination to focus on challenging tasks.

These traits can help individuals of any age navigate unfamiliar circumstances. The pandemic has had an undeniable impact on education, but critical thinking can help us all cope with the changes and challenges presented by COVID-19.

To keep education moving forward during COVID-19 while also supporting your school community, consider the following tips:

- Seek out factual information, not fast information. Make reasoned, informed decisions by understanding facts, evidence-based data, and credible sources. While it is essential to gather and rely on a variety of information and data, critical thinkers know it’s necessary to check the accuracy and bias of what is read and heard. Inquire: Encourage parents, teachers, and students to ask questions. A crisis causes anxiety, stress, and fear if individuals don’t feel permitted to investigate essential questions. Here are a few examples: How will the COVID-19 pandemic impact jobs? What instructional changes might occur? How will grading procedures change? Technology allows us quick access to an abundance of information, some contradictory and misleading. If we forget to pause and carefully review information, it can be dangerous to us and others. Examine: Caution the use of believing everything that is presented in the media. Remind others of the importance of examining information first. Seek out a variety of credible sources. When information is accurate, it can be used to resolve challenges. Misinformation is common, and it’s also harmful. In fact, the U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres recently remarked that the “global ‘misinfo-demic’ is spreading … hatred is going viral, stigmatizing and vilifying people and groups.” While networking platforms such as Facebook work to combat the overabundance of false content, it’s up to us as consumers of media to assess what we read first—and then share it with others. In a crisis, information changes by the minute. A critical thinker knows updates will be forthcoming and how crucial it is to assimilate the latest facts. Because of the vast amount of content available to us, we must continuously remind ourselves to listen to those in the know and to source trusted information—such as the COVID-19 resources NASSP is compiling.

- Practice proactive planning. Be ready to adapt routines as situations change. School leaders have been tasked with hefty responsibilities. As a principal, you’re accountable for the success of your students and staff—a daunting task on the most normal of days. Link: Use your prior knowledge and experiences to problem-solve. As a school leader, you recognize the importance of making connections—if a crisis exists, then effects appear. Discuss potential barriers and challenges with staff members and identify the various ways students and their families may be impacted. We must prepare our school communities to embrace disruption as learning takes on a new image. Educators are not only trying to plan and deliver academic lessons, but they’re also addressing the social aspect of learning in an entirely new format. Collaborate: Offer guidance and support to your colleagues. Set an example by showing how collaboration can help us navigate the new modes of teaching and learning in which we currently find ourselves. Some parents or caregivers might be recently unemployed, others may be struggling to hold onto their jobs, and some may not have the right equipment for remote learning. There are even parents—and teachers—who are trying to manage their schedules while supervising nonschool-aged children. Communicate: Pave the way for two-way communication. Ensure that information sent to students and families is clear and concise. Offer a range of ways for students to interact and ask questions. Provide an avenue for open communication with parents and teachers. As leaders, we must guide our teachers to support parents in establishing new routines while welcoming flexibility in tasks and choice in activities. Remember to integrate time for reflection or downtime within home-based learning. Help parents see the importance of maintaining certain hours for completing tasks or assignments and managing workload.

- Prioritize positive relationship-building. Be confident and recognize the importance of validating the feelings and perspectives of others. Educators are going the distance to keep learning moving forward while maintaining excellence. School leaders realize the importance of retaining the human element in education. Offering reassurance to one another, our students, and their families is vital. Create: Invite faculty to contribute their ideas for the summer and fall semester. Are there instructional practices that should change? Innovative thinking will be a critical piece of successfully returning to school. Never has it been more important to connect with parents and students. We must encourage them and thank them for embracing this new partnership of virtual communication. We must recognize that all situations and classrooms at home are just as diverse as the classrooms in brick-and mortar buildings. Adapt: You have the power to guide others in adapting to new situations. Educators are teaching from their homes; students are learning in their kitchens and living rooms—diverse, at-home situations require flexibility. We can use this as an opportunity to adapt our practices. Whether it’s offering support for parents, hosting “office” hours for students, or providing devices to those in need, change may be required. Let’s work to openly communicate and collaborate, examine the pulse of others, and frequently inquire about their thoughts. We should model talking about today’s issues so we can emulate the importance of analyzing and interpreting information to solve problems—big or small. Strive: Principals recognize the importance of modeling. While planning high-quality online learning isn’t the easiest task, it is possible when you remain focused. When students see their principal and teachers demonstrating “strive,” they can follow suit. Reflect: Take time to reflect on how you can take care of yourself. Crises are draining. We can easily become impatient, weary, and reactive, which makes situations even more problematic. We must pace ourselves, taking moments to pause and consider our own needs as important. Reflecting helps us push through challenges, improve upon past actions, and face our fears. How can we make better choices? How has COVID-19 changed our lives? What support do we need? By voicing our personal experiences, we can dig deeper to reveal strengths and opportunities.

Put Critical Thinking Into Practice

No matter the crisis, the nine traits can assist individuals of any age in making important decisions about their actions or finding an approach for resolution. We all have the capacity to think skillfully. When we incorporate critical thinking into our personal and professional lives, we can better support the growth of ourselves and our school communities. A critical thinker does not give up, but instead seeks ways to improve or resolve problems. Now is the time for principals to recognize the relevancy of thinking beyond the surface.

Sandra Love, EdD, is the director of education insight and research for Mentoring Minds, an organization that provides critical thinking resources to educators. She is a former elementary principal and recipient of the National Distinguished Principal Award.

- More Networks

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, “fake news” or real science critical thinking to assess information on covid-19.

- 1 Department of Applied Didactics, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (USC), Santiago de Compostela, Spain

- 2 IES Ramón Cabanillas, Xunta de Galicia, Cambados, Spain

Few people question the important role of critical thinking in students becoming active citizens; however, the way science is taught in schools continues to be more oriented toward “what to think” rather than “how to think.” Researchers understand critical thinking as a tool and a higher-order thinking skill necessary for being an active citizen when dealing with socio-scientific information and making decisions that affect human life, which the pandemic of COVID-19 provides many opportunities for. The outbreak of COVID-19 has been accompanied by what the World Health Organization (WHO) has described as a “massive infodemic.” Fake news covering all aspects of the pandemic spread rapidly through social media, creating confusion and disinformation. This paper reports on an empirical study carried out during the lockdown in Spain (March–May 2020) with a group of secondary students ( N = 20) engaged in diverse online activities that required them to practice critical thinking and argumentation for dealing with coronavirus information and disinformation. The main goal is to examine students’ competence at engaging in argumentation as critical assessment in this context. Discourse analysis allows for the exploration of the arguments and criteria applied by students to assess COVID-19 news headlines. The results show that participants were capable of identifying true and false headlines and assessing the credibility of headlines by appealing to different criteria, although most arguments were coded as needing only a basic epistemic level of assessment, and only a few appealed to the criterion of scientific procedure when assessing the headlines.

Introduction: Critical Thinking for Social Responsibility – An Urgent Need in the Covid-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global phenomenon that affects almost all spheres of our life, aside from its obvious direct impacts on human health and well-being. As mentioned by the UN Secretary General, in his call for solidarity, “We are facing a global health crisis unlike any in the 75-year history of the United Nations — one that is spreading human suffering, infecting the global economy and upending people’s lives.” (19 March 2020, Guterres, 2020 ). COVID-19 has revealed the vulnerability of global systems’ abilities to protect the environment, health and economy, making it urgent to provide a responsible response that involves collaboration between diverse social actors. For science education the pandemic has raised new and unthinkable challenges ( Dillon and Avraamidou, 2020 ; Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig, 2021 ), which highlight the importance of critical thinking (CT) development in promoting responsible actions and responses to the coronavirus disease, which is the focus of this paper. Despite the general public’s respect of science and scientific advances, denial movements – such as the ones that reject the use of vaccines and advocate for alternative health therapies – are increasing during this period ( Dillon and Avraamidou, 2020 ). The rapid global spread of the coronavirus disease has been accompanied by what the World Health Organization (WHO) has described as the COVID-19 social media infodemic. The term infodemic refers to an overabundance of information (real or not) associated with a specific topic, whose growth can occur exponentially in a short period of time [ World Health Organization (WHO), 2020 ]. The case of the COVID-19 pandemic shows the crucial importance of socio-scientific instruction toward students’ development of critical thinking (CT) for citizenship.

Critical thinking is embedded within the framework of “21st century skills” and is considered one of the goals of education ( van Gelder, 2005 ). Despite its importance, there is not a clear consensus on how to better promote CT in science instruction, and teachers often find it unclear what CT means and requires from them in their teaching practice ( Vincent-Lacrin et al., 2019 ). CT is understood in this study as a set of skills and dispositions that enable students and people to take critical actions based on reasons and values, but also as independent thinking ( Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig, 2021 ). It is also considered as a dialogic practice that students can enact and thereby become predisposed to practice ( Kuhn, 2019 ). We consider that CT has two fundamental roles in SSI instruction: one role linked to the promotion of rational arguments, cognitive skills and dispositions; and the other related to the idea of critical action and social activism, which is consistent with the characterization of CT provided by Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig (2021) . Although research on SSIs has provided us with empirical evidence supporting the benefits of SSI instruction, particularly argumentation and students’ motivation toward learning science, there is still scarce knowledge on how CT is articulated in these contexts. One challenge with promoting CT, especially in SSIs, is linked to new forms of communication that generate a rapid increase of information and easy access to it ( Puig et al., 2020 ).

The study was developed in an unprecedented scenario, during the lockdown in Spain (March–May 2020), which forced the change of face-to-face teaching to virtual teaching, involving students in online activities that embraced the application of scientific notions related to COVID-19 and CT for assessing claims published in news headlines related to it. Previous studies have pointed out the benefits of virtual environments to foster CT among students, particularly asynchronous discussions that minimize social presence and favor all students expressing their own opinion ( Puig et al., 2020 ).

In this research, we aim to explore students’ ability to critically engage in the assessment of the credibility of COVID-19 claims during a moment in which fake news disseminated by social media was shared by the general public and disinformation on the virus was easier to access than real news.

Theoretical Framework

We will first discuss the crucial role of CT to address controversial issues and to fight against the rise of misinformation on COVID-19; and then turn attention to the role of argumentation in students’ development of CT in SSI instruction in epistemic education.

Critical Thinking on Socio-Scientific Instruction to Face the Rise of Disinformation

SSIs are compelling issues for the application of knowledge and processes contributing to the development of CT. They are multifaceted problems, as is the case of COVID-19, that involve informal reasoning and elements of critique where decisions present direct consequences to the well-being of human society and the environment ( Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig, 2021 ). People need to balance subject matter knowledge, personal values, and societal norms when making decisions on SSIs ( Aikenhead, 1985 ) but they also have to be critical of the discourses that shape their own beliefs and practices to act responsibly ( Bencze et al., 2020 ). According to Duschl (2020) , science education should involve the creation of a dialogic discourse among members of a class that focuses on the teaching and learning of “how did we come to know?” and “why do we accept that knowledge over alternatives?” Studies on SSIs during the last decades have pointed out students’ difficulties in building arguments and making critical choices based on evidence ( Evagorou et al., 2012 ). However, literature also indicates that students find SSIs motivational for learning and increase their community involvement ( Eastwood et al., 2012 ; Evagorou, 2020 ), thus they are appropriate contexts for CT development. While research on content knowledge and different modes of reasoning on SSIs is extensive, the practice of CT is understudied in science instruction. Of particular interest in science education are SSIs that involve health controversies, since they include some of the challenges posed by the post-truth era, as the health crisis produced by coronavirus shows. The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting most countries and territories around the world, which is why it is considered the greatest challenge that humankind has faced since the 2nd World War ( Chakraborty and Maity, 2020 ). Issues like COVID-19 that affect society in multiple ways require literate citizens who are capable of making critical decisions and taking actions based on reasons. As the world responds to the COVID-19 pandemic, we face the challenge of an overabundance of information related to the virus. Some of this information may be false and potentially harmful [ World Health Organization (WHO), 2020 ]. In the context of growing disinformation related to the COVID-19 outbreak, EU institutions have worked to raise awareness of the dangers of disinformation and promoted the use of authoritative sources ( European Council of the European Union, 2020 ). Educators and science educators have been increasingly concerned with what can be done in science instruction to face the spread of misinformation and denial of well-established claims; helping students to identify what is true can be a hard task ( Barzilai and Chinn, 2020 ). As these authors suggest, diverse factors may shape what people perceive as true, such as the socio-cultural context in which people live, their personal experiences and their own judgments, that could be biased. We concur with these authors and Feinstein and Waddington (2020) , who argue that science education should not focus on achieving the knowledge, but rather on gaining appropriate scientific knowledge and skills, which in our view involves CT development. Furthermore, according to Sperber et al. (2010) , there are factors that affect the acceptance or rejection of a piece of information. These factors have to do either with the source of the information – “who to believe” – or with its content – “what to believe.” The pursuit of truth when dealing with SSIs can be facilitated by the social practices used to develop knowledge ( Duschl, 2020 ), such as argumentation understood as the evaluation of claims based on evidence, which is part of CT development.

We consider CT and argumentation as overlapping competencies in their contexts of practice; for instance, when assessing claims on COVID-19, as in this study. According to Sperber et al. (2010) , we now have almost no filters on information, and this requires a much more vigilant, knowledgeable reader. As these authors point out, individuals need to become aware of their own cognitive biases and how to avoid being victims themselves. If we want students to learn how to critically evaluate the information and claims they will encounter in social media outside the classroom, we need to engage them in the practice of argumentation and CT. This raises the question of what type of information is easier or harder for students to assess, especially when they are directly affected by the problem. In this paper we aim to explore this issue by exploring students’ arguments while assessing diverse claims on COVID-19. We think that students’ arguments reflect their ability to apply CT in this context, although this does not mean that CT skills always produce a well-reasoned argument ( Halpern, 1998 ). Students should be encouraged to express their own thoughts in SSI instruction, but also to support their views reasonably ( Puig and Ageitos, 2021 ). Specifically, when they must assess the validity of information that affects not only them as individuals but also the whole society and environment. CT may equip citizens to discard fake news and to use appropriate criteria to evaluate information. This requires the design and implementation of specific CT tasks, as this study presents.

Argumentation to Enhance Critical Thinking Development in Epistemic Education on SSIs

While the concept of CT has a long tradition and educators agree on its importance, there is a lack of agreement on what this notion involves ( Thomas and Lok, 2015 ). CT has been used with a wide range of meanings in theoretical literature ( Facione, 1990 ; Ennis, 2018 ). In 1990, The American Philosophical Association convened an authoritative panel of forty-six noted experts on CT to produce a definitive account of the concept, which was published in the Delphi Report ( Facione, 1990 ). The Delphi definition provides a list of skills and dispositions that can be useful and guide CT instruction. However, as Davies and Barnett (2015) point out, this Delphi definition does not include the phenomenon of action. We concur with these authors that CT education should involve students in “CT for action,” since decision making – a way of deciding on a course of action – is based on judgments derived from argumentation using CT. Drawing from Halpern (1998) , we also think that CT requires awareness of one’s own knowledge. CT requires, for instance, insight into what one knows and the extent and importance of what one does not know in order to assess socio-scientific news and its implications ( Puig and Ageitos, 2021 ).

Critical thinking and argumentation share core elements like rationality and reflection ( Andrews, 2015 ). Some researchers suggest understanding CT as a dialogic practice ( Kuhn, 2019 ) has implications in CT instruction and development. Argumentation on SSIs, particularly on health controversies, is receiving increasing attention in science education in the post-truth era, as the coronavirus pandemic and denial movements related to its origin, prevention, and treatment show. Science education should involve the creation of a dialogic discourse among members of a class that enable them to develop CT. One of the central features in argumentation is the development of epistemic criteria for knowledge evaluation ( Jiménez Aleixandre and Erduran, 2008 ), which is a necessary skill to be a critical thinker. We see the practice of CT as the articulation of cognitive skills through the practice of argumentation ( Giri and Paily, 2020 ).

This article argues that science education needs to explore learning experiences and ways of instruction that support CT by engaging learners in argumentation on SSIs. Despite CT being considered a seminal goal in education and the large body of research on CT supporting this ( Dominguez, 2018 ), debates still persist about the manner in which CT skills can be achieved through education ( Abrami et al., 2008 ). Niu et al. (2013) remark that educators have made a striking effort to foster CT among students, showing that the belief that CT can be taught and learned has spread and gained support. Therefore, CT has slowly made its way into general school education and specific instructional interventions. Problem-based learning is one of the most widely used learning approaches nowadays in CT instruction ( Dominguez, 2018 ) because it is motivating, challenging, and enjoyable ( Pithers and Soden, 2000 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). We see active learning methodologies and real-word problems such as SSIs as appropriate contexts for CT development.

The view that CT can be developed by engagement in argumentation practices plays a central role in this study, as Kuhn (2019) suggested. However, the post-truth condition poses some challenges to the evaluation of sources of information and scientific evidence disseminated by social media. According to Sinatra and Lombardi (2020) , the post-truth context raises the need for critical evaluation of online information about SSIs. Students need to be better prepared to assess science information they can easily find online from a variety of sources. Previous studies described by these authors emphasized the importance of source evaluation instruction to equip students toward this goal ( Bråten et al., 2019 ), however, this is not sufficient. Sinatra and Lombardi (2020) note that students should learn how to evaluate the connections between sources of information and knowledge claims. This requires, from our view, engaging students in CT and epistemic performance. If we want students to learn to think critically about the claims they will encounter on social media, they need to practice argumentation as critical evaluation.

We draw on research on epistemic education ( Chinn et al., 2018 ) which considers that learning science entails students’ participation in the science epistemic goals ( Kelly and Licona, 2018 ); in other words, placing scientific practices at the center of SSI instruction. Our study is framed in a broader research project that aims to embed CT in epistemic design and performance. In Chinn et al. (2018) AIR model, epistemic cognition has three core elements that represent the three letters of the acronym: epistemic Aims, goals related to inquiry; epistemic Ideals, standards and criteria used to evaluate epistemic products, such as explanations or arguments; and Reliable processes for attaining epistemic achievements. Of particular interest for our focus on CT is that the AIR model also proposes that epistemic cognition has a social nature, and it is situated. The purpose of epistemic education ( Barzilai and Chinn, 2017 ) should be to enable students to succeed in epistemic activities ( apt epistemic performance ), such as constructing and evaluating arguments, and to assess through meta-competence when success can be achieved. This paper attends to one aspect of epistemic performance proposed by Barzilai and Chinn (2017) , which is cognitive engagement in epistemic assessment. Epistemic assessment encompasses in our study the evaluation of the content of claims disseminated by media. Aligned with these authors we understand that this process requires cognitive and metacognitive competences. Thus, epistemic assessment needs adequate disciplinary knowledge, but also meta-cognitive competence for recognizing unsupported beliefs.

Goal and Research Questions

This paper examines students’ competence to engage in argumentation and CT in an online task that requires them to critically assess diverse information presented in media headlines on COVID-19. Competence in general can be defined as “a disposition to succeed with a certain aim” ( Sosa, 2015 , p. 43) and epistemic competence, as a special case of competence, is at its core a dispositional ability to discern the true from the false in a certain domain. For the purposes of this paper, the attention is on epistemic competence, being the research questions that drive the analysis of the following:

1. What is the competence of students to assess the credibility of COVID-19 information appearing in news headlines?

2. What is the level of epistemic assessment showed in students’ arguments according to the criteria appealed while assessing COVID-19 news headlines?

Materials and Methods

Context, participants, and design.

A teaching sequence about COVID-19 was designed at the beginning of the lockdown in Spain (Mid-March 2020) in response to the rise of misinformation about coronavirus on the internet and social media. The design process involved collaboration between the first and second author (researchers in science education) and the third author (a biology teacher in secondary education).

The participants are a group of twenty secondary students (14–15 years old), eleven of them girls, from a state public school located in a well-known seaside village in Galicia (Spain). They were mostly from middle-class families and within an average range of ability and academic achievement.

Students were from the same classroom and participated in previous online activities as part of their biology classes, taught by their biology teacher, who collaborated on previous studies on CT and learning science through epistemic practices on health controversies.

The activities were integrated in their biology curriculum and carried out when participants received instruction on the topics of health, infectious diseases, and the immune system.

Google Forms was used for the design and implementation of all activities included in the sequence. The reason to select Google Forms is that it is free and a well-known tool for online surveys. Besides, all students were familiar with its use before the lockdown and the teacher valued its usefulness for engaging them in online debates and in their own evaluation processes. This online resource provides anonymous results and statistics that the teacher could share with the students for debates. It needs to be highlighted that during the lockdown students did not have the same work conditions; particularly, quality and availability of access to the internet differed among them. Thus, all activities were asynchronous. They had 1 week to complete each task and the teacher could be consulted anytime if they had difficulties or any question regarding the activities.

The design was inspired by a previous one carried out by the authors when the first case of Ebola disease was introduced in Spain ( Puig et al., 2016 ), and follows a constructivist and scientific-based approach. The sequence began with an initial task, in which students were required to express their own views and knowledge on COVID-19 and health notions related with it, before then being progressively involved in the application of knowledge through the practice of modeling and argumentation. The third activity engaged them in critical evaluation of COVID-19 information. A more detailed description of the activities carried out in the different steps of the sequence is provided below.

Stage 1: General Knowledge on Health Notions Related to COVID-19

An individual Google Forms survey around some notions and health concepts that appear in social media during the lockdown, such as “pandemic”, “virus,” etc.

Stage 2: Previous Knowledge on Coronavirus Disease

This stage consisted of three parts: (2.1) Individual online survey on infectious diseases; (2.2) Introduction of knowledge about infectious diseases provided in the e-bugs project website 1 and activities; virtual visit to the exhibition “Outbreaks: epidemics in a connected world” available in the Natural History Museum website (blinded for review); (2.3) Building a poster with the chain of infection of the COVID-19 disease and some relevant information to consider in order to stop the spread of the disease.

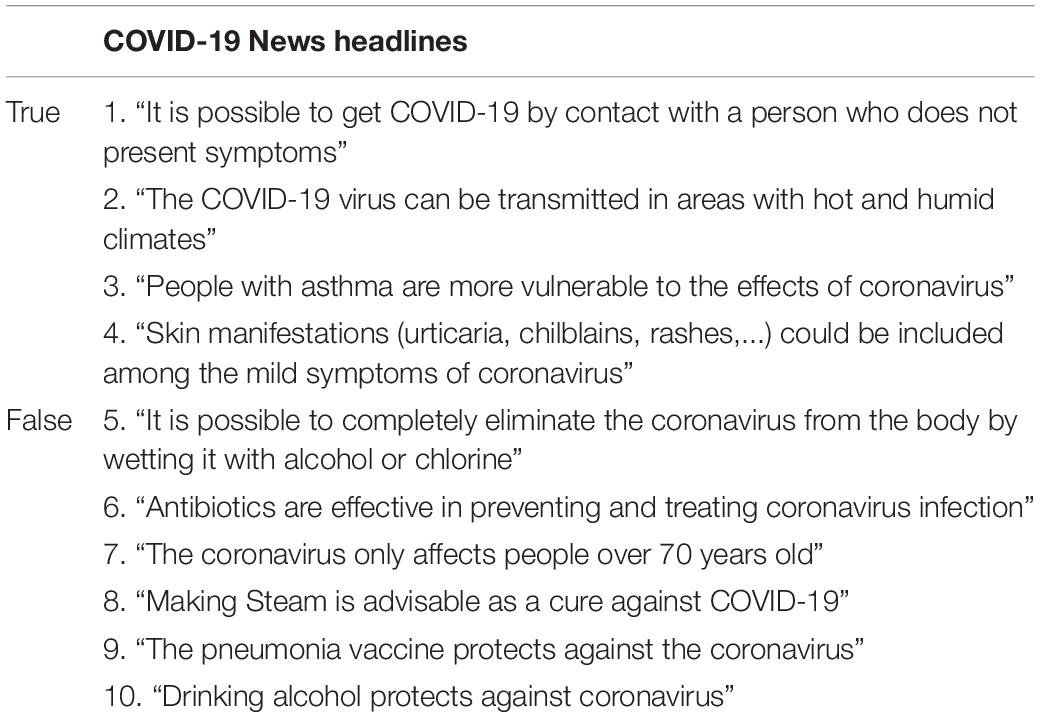

Stage 3: COVID-19, Sources of Information

This stage consisted first of a virtual forum in which students shared their own habits when consulting scientific information, particularly coronavirus-related, and debated on the main media sources they used to consult for this purpose. Secondly, students had to analyze ten news headlines on COVID-19 disseminated by social media during the outbreaks; six corresponded to fake news and four were true. They were asked to critically assess them and distinguish which they thought were true, providing their arguments. Media sources were not provided until the end of the task, since the act of asking for the source was considered as part of the data analysis (see Table 1 ). The second part of this stage is the focus of our analysis.

Table 1. COVID-19 News Headlines provided to students.

Stage 4: Act and Raise Awareness on COVID-19

The sequence ended with the creation of a short video in which the students had to provide some tips to avoid the transmission of the virus. The information provided in the video must be supported and based on established scientific knowledge.

Data Corpus and Analysis

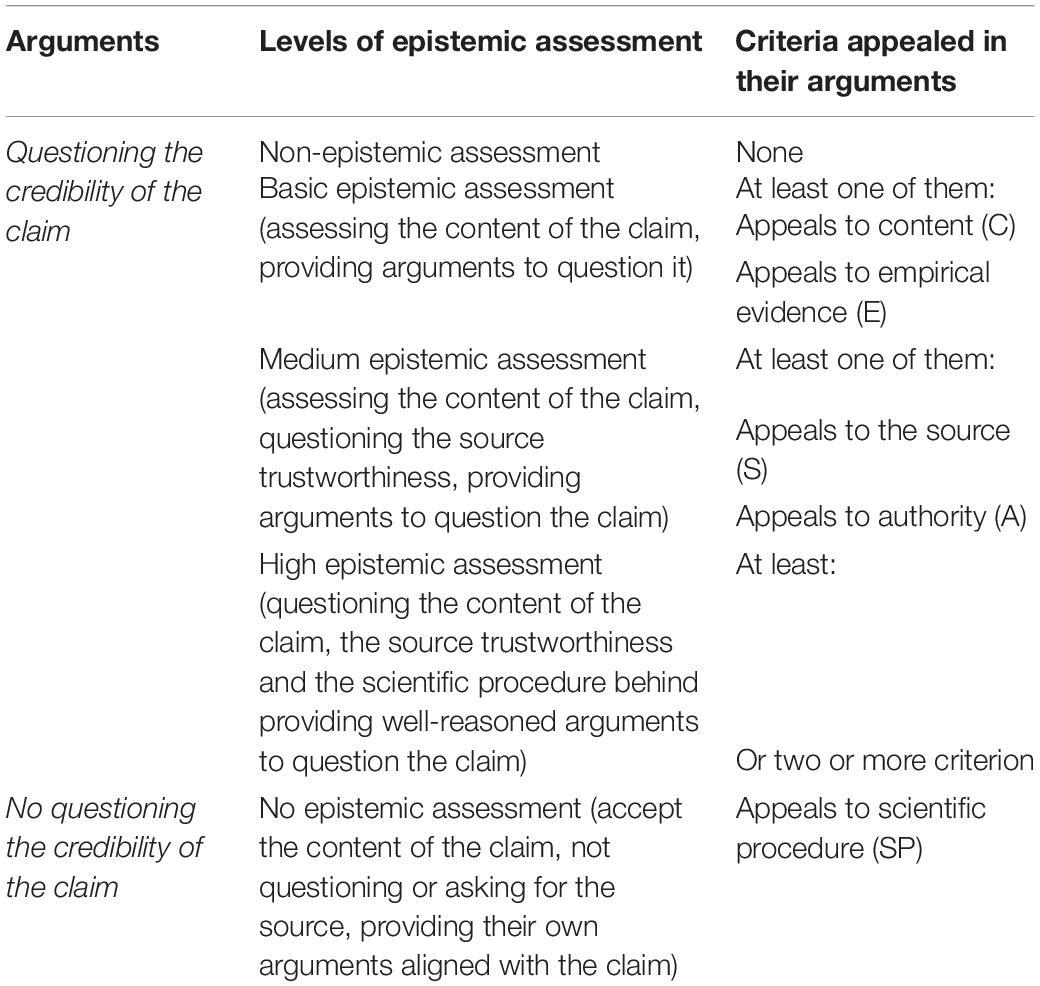

Data collection includes all individual surveys and activities developed in Google Forms. We analyzed students’ individual responses ( N = 28) presented in Stage 3. The research is designed as a qualitative study that utilizes the methods of discourse analysis in accordance with the data and the purpose of the study. Discourse analysis allows the analysis of the content (implicit or explicit) of written arguments produced by students, and so the examination of the research questions. Our analysis focuses on students’ arguments and criteria used to assess the credibility of COVID-19 headlines (ten headlines in total). It was carried out through an iterative process in which students’ responses were read and revised several times in order to develop an open-coded scheme that captures the arguments provided. To ensure the internal reliability of our codes, each student response was examined by the first and the second author separately and then contrasted and discussed until 100% agreement was achieved. The codes obtained were established according to the following criteria, summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2. Code scheme for research questions 1 and 2.

For Research Question 1, we distributed the arguments in two main categories: (1) Arguments that question the credibility of the information ; (2) Arguments that do not question the credibility of the information.

For Research Question 2, we classify arguments that question the credibility of the headline in accordance with the level of epistemic assessment into three levels (see Table 2 ). The level of epistemic assessment (basic, medium, and high) was established by the authors based on the criteria that students applied and expressed explicitly or implicitly in their arguments. These criteria emerged from the data, thus the categories were not pre-established; they were coded by the authors as the following: content (using the knowledge that each student has about the topic), source (questioning the origin of the information), evidence (appealing to empirical evidence as real live situations that students experienced), authority (justifying according to who supports or is behind the claim) and scientific procedure (drawing on the evolution of scientific knowledge).

Students’ Competence to Critically Assess the Credibility of COVID-19 Claims

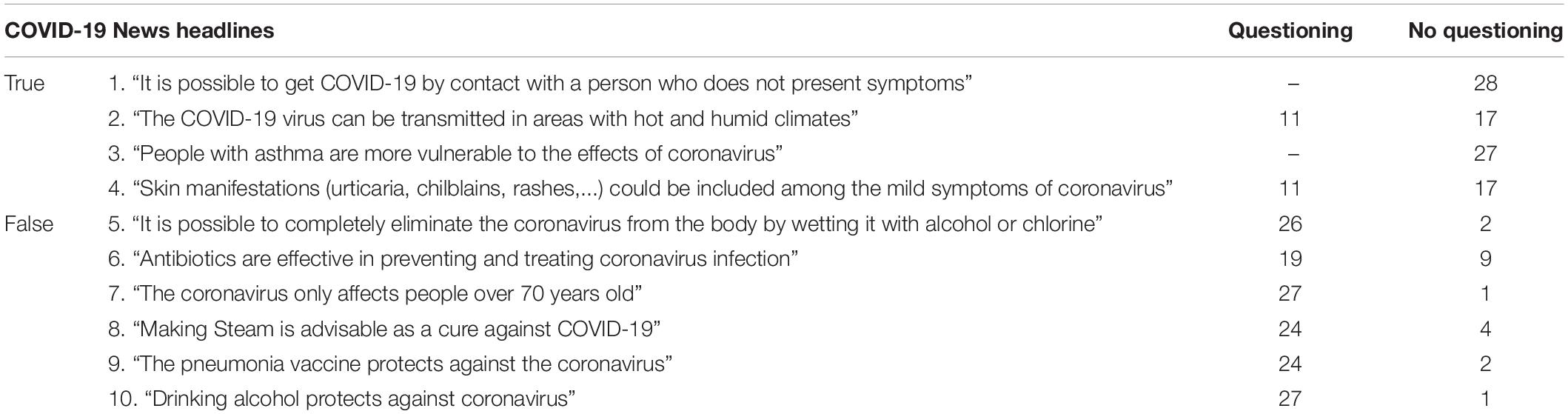

In general, most students were able to distinguish fallacious from true headlines, which was an important step to assess their credibility. For those that were false, students were able to question their credibility, providing arguments against them. On the contrary, for true news headlines, as it was expected, most participants developed arguments supporting them. Thus, they did not question their content. In both cases, the arguments elaborated by students appealed to different criteria discussed in the next section of results.

As shown in Table 3 , 147 arguments were elaborated by students to question the false headlines; they created just 22 arguments to assess the true ones. This finding was expected by the authors, as arguments for questioning or criticality appear more frequently when the information presented differs from students’ opinions.

Table 3. Number of students who questioned or not each news headline on COVID-19.

Students showed a higher capacity for questioning those claims they considered false or fake news , which can be related to the need to justify properly why they consider them false and/or what should be said to counter them.

The headlines that were most controversial, meaning they created diverse positions among students, were these three: “The COVID-19 virus can be transmitted in areas with hot and humid climates,” “Skin manifestations (urticaria, chilblains, rashes…) could be among the mild symptoms of coronavirus” and “Antibiotics are effective in preventing and treating coronavirus infection.”

The first two were questioned by 11 students out of 28, despite being real headlines. According to students’ answers, they were not familiar with this information, e.g., “I think the heat is not good for the virus.” On the contrary, 17 students did not question these headlines, arguing for instance as this student did: “because it was shown that both in hot climates and in cold climates it is contagious in the same way.”

A similar situation happened with the third headline, which is false. A proportion of students (9 out of 28) accepted that antibiotics could help to treat COVID-19, showing in their answers some misunderstanding regarding the use of antibiotics and the diseases they could treat. The rest of the participants (19 out of 28) questioned this headline, affirming that “because antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections and coronavirus is a virus,” among other justifications for why it was false.

Levels of Epistemic Assessment in Students’ Arguments on COVID-19 News Headlines

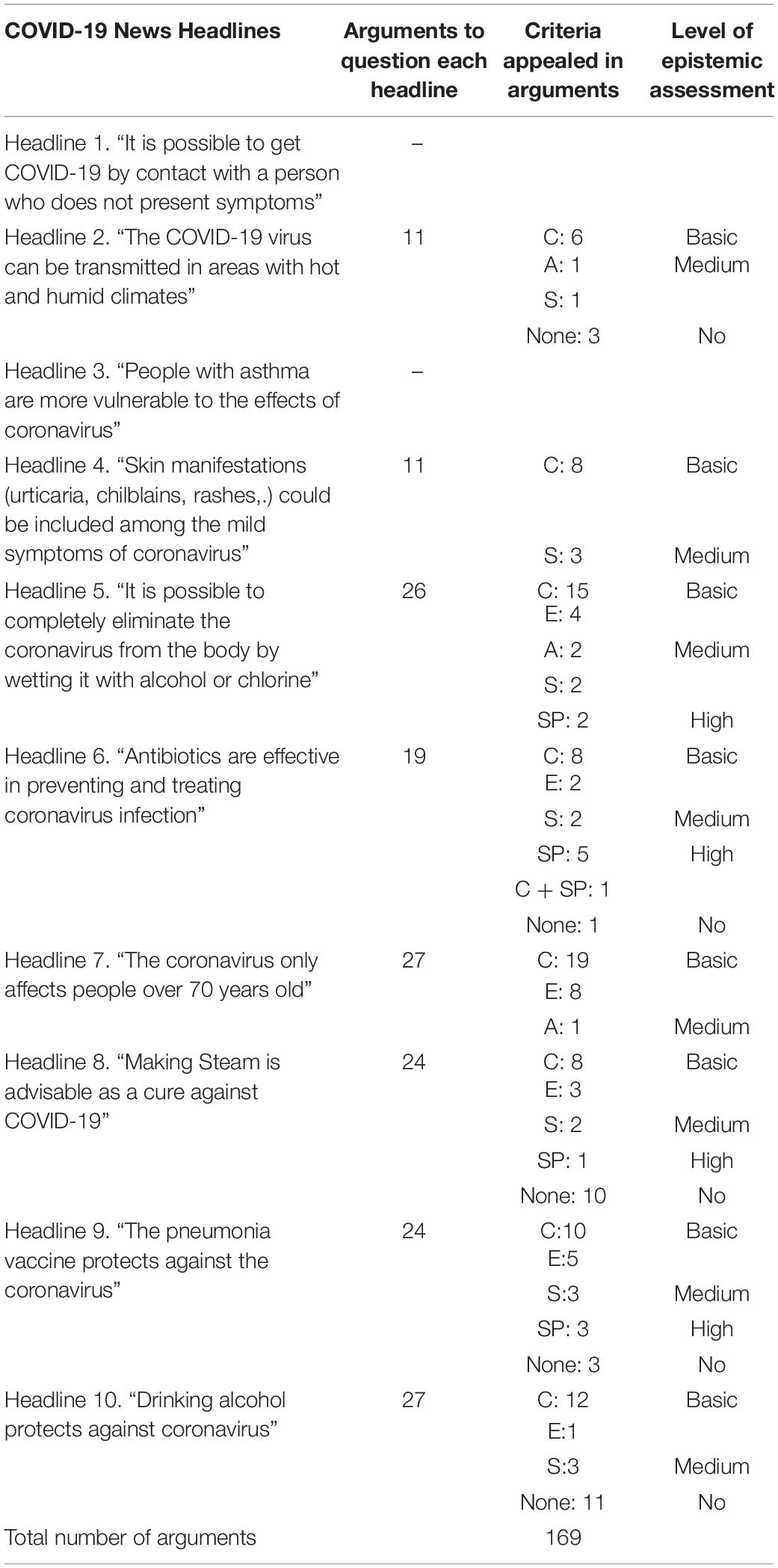

To analyze the level of epistemic assessment showed in students’ arguments when dealing with each headline, attention was focused on the criteria students applied (see Table 2 ). As Table 4 summarizes, almost all arguments included only one criterion (139 out of 169), and 28 out of 169 did not incorporate any criterion. These types of arguments can be interpreted as low epistemic assessment, or even without epistemic assessment if no criterion is included.

Table 4. Arguments used by students to assess the credibility of each COVID-19 headline.

In the category of Basic Epistemic Assessment , we include all students’ arguments that included one criterion: Content or Empirical Evidence. Students assessed the content of the claim appealing to their own knowledge about that piece of information or to empirical evidence, without posing critical questions for assessing the credibility of the source of information. These two criteria, content and evidence, were included in students’ arguments with a frequency of 86 and 23, respectively, with this category the most common (109 out of 169) when questioning false and true headlines. In the case of true headlines, arguments under this category were identified in relation to headlines 2 and 4, whose credibility were questioned by appealing to the content, such as: “those are not the symptoms (skin manifestations) ” . Examples of arguments assessing the content of false headlines are provided below:

“Because the virus is inside the body, and even if you injected alcohol into the body it would only cause intoxication”

This student rejects headline 5, appealing to the fact that alcohol causes intoxication rather than the elimination of coronavirus.

“I know a person who had coronavirus and they only gave him paracetamol”

In this example, the student rejects headline 6 and appeals to his/her own experience during the pandemic, particularly a close person who had coronavirus, as evidence against the use of antibiotics for coronavirus disease treatment.

The category Medium Epistemic Assessment gathers arguments that make critical questions, particularly those asking for information about the authority or the source of information. For us, these criteria reflect a higher level of epistemic performance since they imply questioning beyond the veracity of the headline itself to its sources and authorship. There are 20 out of 169 arguments coded within this category.

The assessment of true headlines includes arguments that question the authority and source, e.g., “because they said it on the news” (headline 2), “that news does not seem very reliable to me” (headline 4). It is also an ordinary category in questioning false headlines, since students appealed to the source (16), “because in the news they clarified that it was a fake news and because it is not credible either” (headline 10) or the authority (4), “because the professionals said they were more vulnerable (people over 70 years old) but not that it only affected them” (headline 7).

For the highest category, High Epistemic Assessment , we consider those arguments (12 out of 169) in which students appealed to the scientific procedure (11) to justify why the headline is false, which manifests students’ reliance on epistemic processes, e.g., “because treatments that protect against coronavirus are still being investigated” (headline 9). Also, under this category we include arguments that combined more than one criterion, content and scientific procedure “Because antibiotics don’t treat those kinds of infections. In addition, no medication has yet been discovered that can prevent the coronavirus” (headline 6). Students’ arguments included in this category were elaborated to assess false headlines.

Lastly, a special mention is afforded to those arguments that did not include any criteria (28), which are contained in the category Non-Epistemic Assessment. It appears more frequently in students’ answers to headlines 8 and 10, as these examples show: “I don’t think it’s true because it doesn’t make much sense to me” (headline 8) or “I never heard it and I doubt it’s true” (regarding drinking alcohol, headline 10).

The findings of our study indicate that students were able to deal with fake news , identifying it as such. They showed capacity to critically assess the content of these news headlines, considering their inconsistencies in relation to their prior knowledge ( Britt et al., 2019 ). As Evagorou (2020) pointed out, SSIs are appropriate contexts for CT development and to value the relevance of science in our lives.

The examination of RQ1 shows that a proportion of students were able to perceive the lack of evidence behind them or even identified that those statements contradict what science presents. This is a remarkable finding and an important skill to fight against attempts to diminish trust in science produced in the post-truth condition ( Dillon and Avraamidou, 2020 ). CT and argumentation are closely allied ( Andrews, 2015 ) but as the results show, knowledge domain seems to play an important role in assessing SSIs news and their implications. Specific CT requires some of the same skills as generalizable CT, but it is highly contextual and requires particular knowledge ( Jones, 2015 ).

Students’ prior knowledge influenced the critical evaluation of some of the COVID-19 headlines provided in the activity. This is particularly relevant in responses to headline 6 (false) “Antibiotics are effective in preventing and treating coronavirus infection.” A previous study on the interactions between the CT and knowledge domain on vaccination ( Ageitos and Puig, 2021 ) showed that there is a correspondence between them. This points to the importance of health literacy for CT development, although it would not be sufficient to provide students with adequate knowledge only, as judgment skills, in this case regarding the proper use of antibiotics, are also required.

We found that the level of epistemic assessment (RQ2) linked to students’ CT capacity is low. A big majority of arguments were situated in a basic epistemic assessment level, and just a few in a higher epistemic assessment. One reason that might explain these results could be related to the task design and format, in which students worked autonomously in a virtual environment. As CT studies in e-learning environments have reinforced ( Niu et al., 2013 ), cooperative or collaborative learning favors CT skills, particularly when students have to discuss and justify their arguments on real-life problems. The circumstances in which students had to work during the outbreak did not allow them to work together since internet connections were not good for all of them, so synchronous activities were not possible. This aspect is a limitation for this research.

There were differences in the use of criteria, and thus in the level of epistemic assessment, when students dealt with true and false headlines. This could be related to diverse factors, such as the language. The claims are marred by language and they are formulated in a different way. Particularly, it is quite nuanced in true statements while certain and resolute in false headlines. The practice of CT requires an understanding of the language, the content under evaluation and other cognitive skills ( Andrews, 2015 ).

In the case of false headlines, most arguments appealed to their content and less to the criteria of source, authority, and the scientific procedure, whereas in the case of true headlines most of them appealed to the authority and/or source. According to the AIR model ( Chinn and Rinehart, 2016 ), epistemic ideals are the criteria used to evaluate the epistemic products, such as claims. In the case of COVID-19 claims, students need to have an ideal of high source credibility ( Duncan et al., 2021 ). This means that students acknowledge that information should be gathered from reliable news media that themselves obtained information from reliable experts.

Only few students used the criterion of scientific procedure when assessing false headlines, which shows a high level of epistemic assessment. Promoting this type of assessment is important since online discourse in the post-truth era is affected by misinformation and by appeals to emotions and ideology.

Conclusion and Implications

This research has been conducted during a moment in which the lives of people were paralyzed, and citizens were forced to stay at home to stop the spread of the coronavirus disease. During the lockdown and even after, apart from these containment measures, citizens in Spain and in many countries had to deal with a huge amount of information about the coronavirus disease, some of it false. The outbreak of COVID-19 has been accompanied by dissemination of inaccurate information spread at high speed, making it more difficult for the public to identify verified facts and advice from trusted sources ( World Health Organization (WHO), 2020 ). As the world responds to the COVID-19 pandemic, many studies have been carried out to analyze the impact of the pandemic on the life of children from diverse views ( Cachón-Zagalaz et al., 2020 ), but not from the perspective of exploring students’ ability to engage in the epistemic assessment of information and disinformation on COVID-19 under a situation of social isolation. This is an unprecedented context in many aspects, where online learning replaced in-person teaching and science uncertainties were more visible than ever.

Participants engaged in the epistemic assessment of coronavirus headlines and were able to put into practice their CT, arguing why they considered them as true or false by appealing to different criteria. We are aware that our results have limitations. Once such limitation is that students performed the activity independently, without creating a collaborative virtual environment, understood by the authors as one of the e-learning strategies that better promote CT ( Puig et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, despite the fact that teachers were available for students to solve any questions regarding the task, the remote and asynchronous process did not allow them to guide the activity in a way that helped the students to carry out a deeper analysis. CT development and epistemic cognition depends on many factors, and teachers have an important role in achieving these goals ( Greene and Yu, 2016 ; Chinn et al., 2020 ).

The analysis of arguments allows us to identify some factors that are crucial and directly affect the critical evaluation of headlines. Some of the students did not question the use of antibiotics for coronavirus disease. This result highlights the importance of health literacy and its interdependency with CT development, as previous studies on vaccine controversies and CT show ( Puig and Ageitos, 2021 ). Although it is not the focus of this paper; the results point to the importance of making students aware of their knowledge limitations for critical assessment. A key instructional implication from this work is making e-learning activities more cooperative, as we have noted, and epistemically guided. Moreover, CT dimensions could be made explicit in instructional materials and assessments. If we want to prepare students to develop CT in order to face real/false news spread by social media, we need to engage them in deep epistemic assessment, namely in the critical analysis of the content, the source, procedures and evidence behind the claims, apart from other tasks. Promoting students’ awareness and vigilance regarding misinformation and disinformation online may also promote more careful and attentive information use ( Barzilai and Chinn, 2020 ), thus activities oriented toward these goals are necessary.

Our study reinforces the need to design more CT activities that guide students in the critical assessment of diverse aspects behind controversial news as a way to fight against the rise of disinformation and develop good knowledge when dealing with SSIs. Students’ epistemological views can influence their performance on argumentation thus, if uncertainty of knowledge is explicitly address in SSI instruction and epistemic activities, students’ epistemological views may be developed, and such development may in turn influence their argumentation competence and consequently their performance on CT.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin to participate in this study in accordance with the National Legislation and the Institutional Requirements.

Author Contributions

BP conducted the conceptual framework and designed the research study. PB-A conducted the data analysis and collaborated in manuscript preparation. JP-M implemented the didactical proposal and collected the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the project ESPIGA, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Education and Universities, partly funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Grant code: PGC2018-096581-B-C22.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out within the RODA research group during the lockdown in Spain due to COVID-19 pandemic. We gratefully acknowledge all the participants for their implication, despite such difficult circumstances.

- ^ https://www.e-bug.eu

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Ramim, R., et al. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: a stage 1 meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res . 78, 1102–1134. doi: 10.3102/0034654308326084

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ageitos, N., and Puig, B. (2021). “Critical thinking to decide what to believe and what to do regarding vaccination in schools. a case study with primary pre-service teachers,” in Critical Thinking in Biology and Environmental Education. Facing Challenges in a Post-Truth World , eds B. Puig and M. P. Jiménez-Aleixandre (Berlin: Springer).

Google Scholar

Aikenhead, G. S. (1985). Collective decision making in the social context of science. Sci. Educ . 69, 453–475. doi: 10.1002/sce.3730690403

Andrews, R. (2015). “Critical thinking and/or argumentation in highr education,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , eds M. Davies, R. Barnett, et al. (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 93–105.

Barzilai, S., and Chinn, C. A. (2017). On the goals of epistemic education: promoting apt epistemic performance. J. Learn. Sci . 27, 353–389. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2017.1392968

Barzilai, S., and Chinn, C. A. (2020). A review of educational responses to the “post-truth” condition: four lenses on “post-truth” problems. Educ. Psychol. 55, 107–119. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2020.1786388

Bencze, L., Halwany, S., and Zouda, M. (2020). “Critical and active public engagement in addressing socioscientific problems through science teacher education,” in Science Teacher Education for Responsible Citizenship , eds M. Evagorou, J. A. Nielsen, and J. Dillon (Berlin: Springer), 63–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-40229-7_5

Bråten, I., Brante, E. W., and Strømsø, H. I. (2019). Teaching sourcing in upper secondary school: a comprehensive sourcing intervention with follow-up data. Read. Res. Q . 54, 481–505. doi: 10.1002/rrq.253

Britt, M. A., Rouet, J. F., Blaum, D., and Millis, K. K. (2019). A reasoned approach to dealing with fake news. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci . 6, 94–101. doi: 10.1177/2372732218814855

Cachón-Zagalaz, J., Sánchez-Zafra, M., Sanabrias-Moreno, D., González-Valero, G., Lara-Sánchez, A. J., and Zagalaz-Sánchez, M. L. (2020). Systematic review of the literature about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of school children. Front. Psychol . 11:569348. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569348

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chakraborty, I., and Maity, P. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ . 728:138882. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882

Chinn, C., and Rinehart, R. W. (2016). “Epistemic cognition and philosophy: developing a new framework for epistemic cognition,” in Handbook of Epistemic Cognition , eds J. A. Greene, W. A. Sandoval, and I. Braten (New York, NY: Routledge), 460–478.

Chinn, C. A., Barzilai, S., and Duncan, R. G. (2020). Disagreeing about how to know. the instructional value of explorations into knowing. Educ. Psychol . 55, 167–180. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2020.1786387

Chinn, C. A., Duncan, R. G., and Rinehart, R. (2018). “Epistemic design: design to promote transferable epistemic growth in the PRACCIS project,” in Promoting Spontaneous Use of Learning and Reasoning Strategies. Theory, Research and Practice for Effective Transfer , eds E. Manalo, Y. Uesaka, and C. A. Chinn (Abingdon: Routledge), 243–259.

Davies, M., and Barnett, R. (2015). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education . London: Palgrave MacMillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137378057

Dillon, J., and Avraamidou, L. (2020). Towards a viable response to COVID-19 from the science education community. J. Activist Sci. Technol. Educ . 11, 1–6. doi: 10.33137/jaste.v11i2.34531

Dominguez, C. (2018). A European Review on Critical Thinking Educational Practices in Higher Education Institutions. Vila Real: UTAD. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322725947_A_European_review_on_Critical_Thinking_educational_practices_in_Higher_Education_Institutions

Duncan, R. G., Caver, V. L., and Chinn, C. A. (2021). “The role of evidence evaluation in critical thinking,” in Critical Thinking in Biology and Environmental Education. Facing Challenges in a Post-Truth World , eds B. Puig and M. P. Jiménez-Aleixandre (Berlin: Springer).

Duschl, R. (2020). Practical reasoning and decision making in science: struggles for truth. Educ. Psychol . 3, 187–192. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2020.1784735

Eastwood, J. L., Sadler, T. D., Zeidler, D. L., Lewis, A., Amiri, L., and Applebaum, S. (2012). Contextualizing nature of science instruction in socioscientific issues. Int. J. Sci. Educ . 34, 2289–2315. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2012.667582

Ennis, R. (2018). Critical thinking across the curriculum. Topoi 37, 165–184. doi: 10.1007/s11245-016-9401-4

European Council of the European Union (2020). Fighting Disinformation . Available online at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/coronavirus/fighting-disinformation/

Evagorou, M. (2020). “Introduction: socio-scientific issues as promoting responsible citizenship and the relevance of science,” in Science Teacher Education for Responsible Citizenship , eds M. Evagorou, J. A. Nielsen, and J. Dillon (Berlin: Springer), 1–11. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-40229-7_1

Evagorou, M., Jimenez-Aleixandre, M. P., and Osborne, J. (2012). ‘Should we kill the grey squirrels?’ a study exploring students’ justifications and decision-making. Int. J. Sci. Educ . 34, 401–428. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2011.619211

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical Thinking: a Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. Fullerton, CA: California State University.

Feinstein, W. N., and Waddington, D. I. (2020). Individual truth judgments or purposeful, collective sensemaking? rethinking science education’s response to the post-truth era. Educ. Psychol . 55, 155–166. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2020.1780130

Giri, V., and Paily, M. U. (2020). Effect of scientific argumentation on the development of critical thinking. Sci. Educ . 29, 673–690. doi: 10.1007/s11191-020-00120-y

Greene, J. A., and Yu, S. B. (2016). Educating critical thinkers: the role of epistemic cognition. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci . 3, 45–53. doi: 10.1177/2372732215622223

Guterres, A (2020). Secretary-General Remarks on COVID-19: A Call for Solidarity . Available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_remarks_on_covid-19_english_19_march_2020.pdf (accessed March 19, 2020).

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains. dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. Am. Psychol . 53, 449–455. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.53.4.449

Jiménez Aleixandre, M. P., and Erduran, S. (2008). “Argumentation in science education: an overview,” in Argumentation in Science Education: Perspectives from Classroom-Based Research , eds S. Erduran and M. P. Jiménez Aleixandre (Dordrecht: Springer), 3–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6670-2_1

Jiménez-Aleixandre, M. P., and Puig, B. (2021). “Educating critical citizens to face post-truth: the time is now,” in Critical Thinking in Biology and Environmental Education. Facing Challenges in a Post-Truth World , eds B. Puig and M. P. Jiménez-Aleixandre (Berlin: Springer).

Jones, A. (2015). “A disciplined approach to CT,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , eds M. Davies, R. Barnett, et al. (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 93–105.

Kelly, G. J., and Licona, P. (2018). “Epistemic practices and science education,” in History, Philosophy and Science Teaching , ed. M. R. Matthews (Dordrecht: Springer), 139–165. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62616-1_5

Kuhn, D. (2019). Critical thinking as discourse. Hum. Dev . 62, 146–164. doi: 10.1159/000500171

Niu, L., Behar-Horenstein, L. S., and Garvan, C. W. (2013). Do instructional interventions influence college students’ critical thinking skills? a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev . 9, 114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2012.12.002

Pithers, R. T., and Soden, R. (2000). Critical thinking in education: a review. Educ. Res . 42, 237–249.

Puig, B., and Ageitos, N. (2021). “Critical thinking to decide what to believe and what to do regarding vaccination in schools. a case study with primary pre-service teachers,” in Critical Thinking in Biology and Environmental Education. Facing Challenges in a Post-Truth World , eds B. Puig and M. P. Jiménez-Aleixandre (Berlin: Springer).

Puig, B., Blanco Anaya, P., and Bargiela, I. M. (2020). “A systematic review on e-learning environments for promoting critical thinking in higher education,” in Handbook of Research in Educational Communications and Technology , eds M. J. Bishop, E. Boling, J. Elen, and V. Svihla (Cham: Springer), 345–362. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36119-8_15

Puig, B., Blanco Anaya, P., Crujeiras Pérez, B., and Pérez Maceira, J. (2016). Ideas, emociones y argumentos del profesorado en formación acerca del virus del Ébola. Indagatio Didactica 8, 764–776.

Sinatra, G. M., and Lombardi, D. (2020). Evaluating sources of scientific evidence and claims in the post-truth era may require reappraising plausibility judgments. Educ. Psychol . 55, 120–131. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2020.1730181

Sosa, E. (2015). Judgment and Agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sperber, D., Clement, F., Heintz, C., Mascaro, O., Mercier, H., Origgi, G., et al. (2010). Epistemic vigilance. Mind Lang . 25, 359–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0017.2010.01394.x

Thomas, K., and Lok, B. (2015). “Teaching critical thinking: an operational framework,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , eds M. Davies, R. Barnett, et al. (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 93–105. doi: 10.1057/9781137378057_6

van Gelder, T. (2005). Teaching critical thinking. some lessons from cognitive science. Coll. Teach . 53, 41–48. doi: 10.3200/CTCH.53.1.41-48

Vincent-Lacrin, S., González-Sancho, C., Bouckaert, M., de Luca, F., Fernández-Barrera, M., Jacotin, G., et al. (2019). Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What it Means in School, Educational Research and Innovation. Paris: OED Publishing.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Promoting Healthy Behaviours and Mitigating the Harm from Misinformation and Disinformation. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation

Keywords : critical thinking, argumentation, socio-scientific issues, COVID-19 disease, fake news, epistemic assessment, secondary education

Citation: Puig B, Blanco-Anaya P and Pérez-Maceira JJ (2021) “Fake News” or Real Science? Critical Thinking to Assess Information on COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:646909. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.646909

Received: 28 December 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021; Published: 03 May 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Puig, Blanco-Anaya and Pérez-Maceira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Blanca Puig, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Science Education for Citizenship through Socio-Scientific issues

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Thinking about life in COVID-19: An exploratory study on the influence of temporal framing on streams-of-consciousness

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Communication, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

- Constance M. Bainbridge,

- Published: April 28, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285200

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The COVID-19 global pandemic led to major upheavals in daily life. As a result, mental health has been negatively impacted for many, including college students who have faced increased stress, depression, anxiety, and social isolation. How we think about the future and adjust to such changes may be partly mediated by how we situate our experiences in relation to the pandemic. To test this idea, we investigate how temporal framing influences the way participants think about COVID life. In an exploratory study, we investigate the influence of thinking of life before versus during the pandemic on subsequent thoughts about post-pandemic life. Participants wrote about their lives in a stream-of-consciousness style paradigm, and the linguistic features of their thoughts are extracted using Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). Initial results suggest principal components of LIWC features can distinguish the two temporal framings just from the content of their post-pandemic-oriented texts alone. We end by discussing theoretical implications for our understanding of personal experience and self-generated narrative. We also discuss other aspects of the present data that may be useful for investigating these thought processes in the future, including document-level features, typing dynamics, and individual difference measures.

Citation: Bainbridge CM, Dale R (2023) Thinking about life in COVID-19: An exploratory study on the influence of temporal framing on streams-of-consciousness. PLoS ONE 18(4): e0285200. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285200

Editor: Michal Ptaszynski, Kitami Institute of Technology, JAPAN

Received: November 4, 2022; Accepted: April 18, 2023; Published: April 28, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Bainbridge, Dale. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data and analysis script is available on Github: https://github.com/conbainbridge/covid_thoughts DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7809317 .

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

What is the semantic structure of free-flowing thought? How do meanings come up in our thoughts, and how are they linked over time? Human experience is filled with this structure, while we stand in line for our groceries, wait in line at the bus station or even in a moment of mind wandering while conversing with a friend. In this paper, we explore recent events surrounding COVID as a domain to tap into this semantic structure. We devised a “stream-of-consciousness” task in which participants imagined the future beyond COVID, and quantified how their free-flowing thought varied as a function of how they were prompted before this writing. We find that if participants are prompted with the present COVID situation vs. the pre-COVID times, their structure of thought changes. Our exploratory analyses suggest language from the future-oriented responses reflects its temporal priming, i.e., the pre-pandemic vs. during the pandemic prompt that came before. These results offer hints at the semantic patterns that characterize these self-reflections, and how context is central to the forms they take. We end by arguing that a generalized notion of “self-communication” may organize phenomena such as these in intriguing ways.

When the COVID-19 global pandemic spread rapidly in late 2019 and early 2020, major life impacts reverberated globally. These effects were felt across many aspects of everyday life, from direct health impacts to more indirect effects on the economy and social life. People began referring to life before the pandemic colloquially as the “before times,” and there was a sense of a new normal. These effects were also significant in the lives of younger individuals, such as students, with virtual schooling, diminished social interaction, and limited hands-on learning (e.g., [ 1 ]). Evidence suggests an alarming impact of the pandemic on the mental health of college students, including increased stress moderated by self-regulation efficacy [ 2 ], increased depression and anxiety [ 3 ], and negative changes to student relationships [ 4 ]. The effect of perceived threat of COVID-19 on mental well-being appears to be mediated by future anxiety as well, showing the potential to impact mental health in the long run as decisions about the future may be impacted [ 5 ]. The pandemic thus provides a unique opportunity to study how major events influence perceptions of life and mental health, and their relationship to other dimensions.

To study these perceptions, we investigate how student participants construct a narrative text about their lives. Our approach is inspired by methods used in essay writing and journaling [ 6 ], self-talk [ 7 ], and think aloud [ 8 ]. These domains suggest that when we speak to ourselves, ruminate, or reflect on aspects of our lives, our linguistic styles and strategies may be a signature for underlying mental or emotional states and processes. Intriguingly, such intrapersonal communication has been frequently the topic of discussion, yet remains largely an understudied construct. Self-communication occurs when both sender and receiver of a communicative instance are contained within a single individual, such as in dialogical self-talk [ 7 ], and can include transcending across time and space [ 9 ]. Here we use this process as a source of data about these life perceptions.

While not all aspects of intrapersonal communication may be easily accessible for study, such as the seemingly endless streams-of-consciousness we engage in every day, various methods have been employed to tap into self-talk through writing or speech. Raffaelli et al. [ 8 ] used a think aloud paradigm in which individuals are instructed to speak aloud their thoughts. Negative valence in the words used correlated with a narrowing of conceptual scope, such that thoughts became more semantically similar when they were more negative. Social context may play a role, too. Oliver et al. [ 10 ] used a think aloud task to study mental health outcomes. Changing social context to more supportive environments led to greater use of positive emotion words, fewer negative emotion words, fewer swear words, and fewer first-person references compared to a control condition that lacked emotional recognition or meaningful rationale. Recent work has shown that self-talk also links to mental health outcomes during COVID-19. In a questionnaire study conducted on an Iranian sample, there were significant relationships found between self-talk, death anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and coping strategies in relation to the pandemic [ 11 ].