South Africa's Black Consciousness Movement in the 1970s

Voice of Anti-Apartheid Movement in South Africa

- American History

- African American History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/download-5c293cd646e0fb0001dd5b3e.jpg)

- Ph.D., History, University of Michigan - Ann Arbor

- M.A., History, University of Michigan - Ann Arbor

- B.A./B.S, History and Zoology, University of Florida

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was an influential student movement in the 1970s in Apartheid South Africa. The Black Consciousness Movement promoted a new identity and politics of racial solidarity and became the voice and spirit of the anti-apartheid movement at a time when both the African National Congress and the Pan-Africanist Congress had been banned in the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre . The BCM reached its zenith in the Soweto Student Uprising of 1976 but declined quickly afterward.

Rise of the Black Consciousness Movement

The Black Consciousness Movement began in 1969 when African students walked out of the National Union of South African Students, which was multiracial but white-dominated, and founded the South African Students Organization (SASO). The SASO was an explicitly non-white organization open to students classified as African, Indian, or Coloured under Apartheid Law.

It was to unify non-white students and provide a voice for their grievances, but the SASO spearheaded a movement that reached far beyond students. Three years later, in 1972, the leaders of this Black Consciousness Movement formed the Black People’s Convention (BPC) to reach out to and galvanize adults and non-students.

Aims and Forerunners of the BCM

Loosely speaking, the BCM aimed to unify and uplift non-white populations, but this meant excluding a previous ally, liberal anti-apartheid whites. As Steve Biko , the most prominent Black Consciousness leader, explained, when militant nationalists said that white people did not belong in South Africa, they meant that “we wanted to remove [the white man] from our table, strip the table of all trappings put on it by him, decorate it in true African style, settle down and then ask him to join us on our own terms if he liked.”

The elements of Black pride and celebration of Black culture linked the Black Consciousness Movement back to the writings of W. E. B. Du Bois, as well as the ideas of pan-Africanism and La Negritude movement. It also arose at the same time as the Black Power movement in the United States, and these movements inspired each other; Black Consciousness was both militant and avowedly non-violent. The Black Consciousness movement was also inspired by the success of the FRELIMO in Mozambique.

Soweto and the Afterlives of the BCM

The exact connections between the Black Consciousness Movement and the Soweto Student Uprising are debated, but for the Apartheid government, the connections were clear enough. In the aftermath of Soweto, the Black People’s Convention and several other Black Consciousness movements were banned and their leadership arrested, many after being beaten and tortured, including Steve Biko who died in police custody.

The BPC was partially resurrected in the Azania People’s Organization, which is still active in South African politics.

- Steve, Biko, I Write What I like: Steve Biko. A Selection of his Writings, ed. by Aelred Stubbs, African Writers Series . (Cambridge: Proquest, 2005), 69.

- Desai, Ashwin, “Indian South Africans and the Black Consciousness Movement under Apartheid.” Diaspora Studies 8.1 (2015): 37-50.

- Hirschmann, David. “The Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa.” The Journal of Modern African Studies . 28.1 (Mar., 1990): 1-22.

- Biography of Stephen Bantu (Steve) Biko, Anti-Apartheid Activist

- Biography of Nontsikelelo Albertina Sisulu, South African Activist

- What Was Apartheid in South Africa?

- 16 June 1976 Student Uprising in Soweto

- The End of South African Apartheid

- Understanding South Africa's Apartheid Era

- Biography of Donald Woods, South African Journalist

- A Brief History of South African Apartheid

- Apartheid 101

- Grand Apartheid in South Africa

- Pass Laws During Apartheid

- Memorable Quotes by Steve Biko

- The Origins of Apartheid in South Africa

- South Africa's Extension of University Education Act of 1959

- The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act

- Apartheid Quotes About Bantu Education

Black Consciousness and South Africa’s National Literature pp 17–40 Cite as

The History of Black Consciousness

- Tom Penfold 2

- First Online: 14 October 2017

289 Accesses

Beginning with its roots in Bantu Education, this chapter sketches the rise and fall of Black Consciousness. Penfold summarises the diverse and complex influences behind this struggle ideology that was led by Steve Biko. Importantly, Penfold suggests that Black Consciousness must be fundamentally understood as a cultural movement. He also questions the suitability of using simplified racial binaries when discussing Black Consciousness ideology. The chapter ends with a discussion of the 1976 Soweto Uprisings. It speculates as to the different ways Black Consciousness remained prominent in South Africa’s political and literary psyche after its official banning.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Biko, Steve. n.d. [1987]. We Blacks. In I Write What I Like, ed. Aelred Stubbs, 27–32. Oxford: Heinemann.

Google Scholar

Biko, Steve. 1970 [1987]. Black Souls in White Skins? In I Write What I Like , ed. Aelred Stubbs, 19–26. Oxford: Heinemann.

Biko, Steve. 1971 [1987]. Some African Cultural Concepts. In I Write What I Like , ed. Aelred Stubbs, 40–47. Oxford: Heinemann.

Biko, Steve. 1972. White Racism and Black Consciousness. In Student Perspectives on South Africa , ed. Hendrik van der Merwe, and David Walsh, 190–202. Cape Town: David Philip.

Biko, Steve. 1973 [1987]. Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity. In I Write What I Like , ed. Aelred Stubbs, 87–98. Oxford: Heinemann.

Biko, Steve. 1976 [1978]. Oral Testimony. In The Testimony of Steve Biko , ed. Millard Arnold. London: Maurice Temple Smith.

Bowers, Chet, and Frederique Apffel-Marqlin. 2004. Re-thinking Freire: Globalization and the Environmental Crisis . London: Routledge.

Brooks, Alan, and Jeremy Brickhill. 1980. Whirlwind Before the Storm . London: International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa.

Brown, Julian. 2009. Public Protest and Violence in South Africa, 1948–1976. Unpublished Ph.D., University of Oxford.

Cabral, Amilcar. 1980. Unity and Struggle , trans. Michael Wolfers. London: Heinemann.

Dlamini, Jacob. 2009. Native Nostalgia . Johannesburg: Jacana Press.

Fanon, Frantz. 1965. The Wretched of the Earth , trans. Constance Farrington. London: MacGibbon and Gee.

Fanon, Frantz. 1968. Black Skin, White Masks , trans. Charles Lam Markmann. London: MacGibbon and Gee.

Fleisch, Brahm. 2002. State Formation and the Origins of Bantu Education. In The History of Education Under Apartheid, 1948–1994 , ed. Peter Kallaway, 39–52. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Gerhart, Gail. 1978. Black Power in South Africa . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gibson, Nigel. 2004. Black Consciousness 1977–1987: The Dialectics of Liberation in South Africa. Centre for Civil Society Research Report No. 18, Durban.

Giliomee, Hermann. 2003. The Afrikaners . London: Hurst and Company.

Healy, Meghan. 2011. ‘To Control Their Destiny’: The Politics of Home and the Feminisation of Schooling in Colonial Natal, 1885–1910. Journal of Southern African Studies 37 (2): 247–264.

Article Google Scholar

Hirson, Baruch. 1979. Year of Fire, Year of Ash . London: Zed Press.

Hook, Derek. 2004. Frantz Fanon, Steve Biko, ‘Psycho-politics’ and Critical Psychology. In LSE Research Online . London: London School of Economics.

Horrell, Muriel. 1968. Bantu Education to 1968 . Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations.

Hutmacher, Barbara. 1980. In Black and White . London: Junction Books.

Kallaway, Peter. 2002. Introduction. In The History of Education Under Apartheid, 1948–1994 , ed. Peter Kallaway, 1–15. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Khoapa, Bennie. 1972. The New Black. In Black Viewpoint , 61–67. Durban: Black Community Programmes.

Lobban, Michael. 1996. White Man’s Justice . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lodge, Tom. 1983. Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945 . Frome: Longman Group.

Lodge, Tom. 1991. All, Here, and Now . London: Hurst and Co.

Magaziner, Daniel. 2010. The Law and the Prophets . Athens: Ohio University Press.

Mathiane, Nomavenda. 1989. South Africa: Diary of Troubled Times . London: Roman and Littlefield.

May, Stephen. 2008. Language and Minority Rights . New York: Routledge.

Mji, Diliza. 1977. SASO Bulletin . Durban: Black Community Programmes.

Moodie, Dunbar. 2009. N. P. van Wyk Louw and the Moral Predicament of Afrikaner Nationalism: Preparing the Ground for Verligte Reform. Prepublication manuscript.

Mufson, Steven. 1991. Introduction. In All, Here, and Now , ed. Tom Lodge, 3–21. London: Hurst and Co.

Ndebele, Njabulo. 1972. Black Development. In Black Viewpoint , ed. Steve Biko, 13–28. Durban: Black Community Programmes.

O’Meara, Dan. 1996. Forty Lost Years . Randburg: Ravan Press.

Pelzer, A.N. 1966. Verwoerd Speaks: Speeches 1948–1966 . Johannesburg: AP Publishers.

Ramphele, Mamphela. 1996. Across Boundaries . New York: First Feminist Press.

Reed, W.C. 1999. Review: Liberals Against Apartheid: A History of the Liberal Party of South Africa, 1953–1968 by Randolph Vigne. Africa Today 46 (1): 145–147.

Reyhner, Jon. 2012. Review of Kirkendall, Andrew, Paulo Freire and the Cold War Politics of Literacy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press (H-Education: H-Net Reviews).

Rich, Paul B. 1984. White Power and the Liberal Conscience . Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

Sanders, Mark. 2003. Complicities: The Intellectual and Apartheid . London: Duke University Press.

Seekings, Jeremy. 2000. The UDF . Oxford: James Currey.

Seleoane, Mandla. 2007. Biko’s Influence and a Reflection. In We Write What We Like , ed. Chris van Wyk, 63–75. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Senghor, Leopold. 1965. Prose and Poetry , ed. John Reed and Clive Wake. London: Heinemann.

South African Education Trust. 2010. The Road to Democracy in South Africa, Volume 2: 1970–1980 . Johannesburg: UNISA Press.

Snail, Mgwebi. 2008. The Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa: A Product of the Entire Black World. Historia Actual Online 15: 51–68.

Tambo, Oliver. 1987. Black Consciousness and the Soweto Uprising. In Preparing for Power , ed. Adelaid Tambo, 115–131. London: Heinemann.

Willan, Brian. 1982. An African in Kimberley: Sol T. Plaatje, 1894–1898. In Industrialisation and Social Change in South Africa , ed. Shula Marks and Richard Rathbone, 238–258. Harlow: Longman Group.

Woods, Donald. 1978. Biko . London: Paddington Press.

Vigne, Randolph. 1997. Liberals Against Apartheid. New York: St Martin’s Press.

TRC. 1998. Truth and Reconciliation Commission Final Report, vol. 3. Cape Town.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Tom Penfold

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tom Penfold .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Penfold, T. (2017). The History of Black Consciousness. In: Black Consciousness and South Africa’s National Literature. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57940-5_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57940-5_2

Published : 14 October 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-57939-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-57940-5

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Steve Biko: The Black Consciousness Movement

The saso, bcp & bpc years.

By Steve Biko Foundation

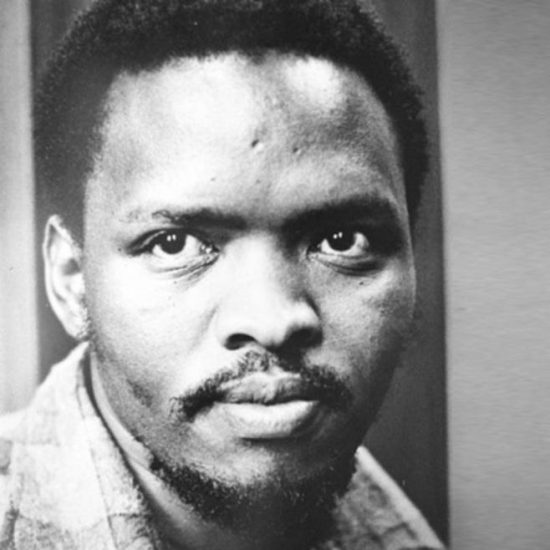

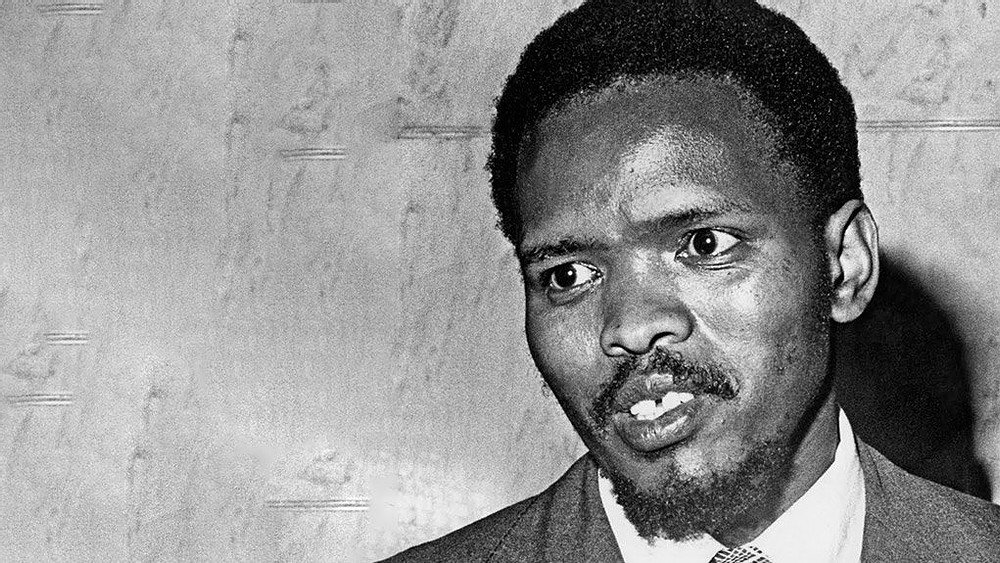

Stephen Bantu Biko was an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. A student leader, he later founded the Black Consciousness Movement which would empower and mobilize much of the urban black population. Since his death in police custody, he has been called a martyr of the anti-apartheid movement. While living, his writings and activism attempted to empower black people, and he was famous for his slogan “black is beautiful”, which he described as meaning: “man, you are okay as you are, begin to look upon yourself as a human being”. Scroll on to learn more about this iconic figure and his pivotal role in the Black Consciousness Movement...

“Black Consciousness is an attitude of mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time” - Biko

1666/67 University of Natal SRC

On completion of his matric at St Francis College, Biko registered for a medical degree at the University of Natal’s Black Section. The University of Natal professed liberalism and was home to some of the leading intellectuals of that tradition. The University of Natal had also become a magnet attracting a number of former black educators, some of the most academically capable members of black society, who had been removed from black colleges by the University Act of 1959. The University of Natal also attracted as law and medical students some of the brightest men and women from various parts of the country and from various political traditions. Their convergence at the University of Natal in the 1960s turned the University into a veritable intellectual hub, characterised by a diverse culture of vibrant political discourse. The University thus became the mainstay of what came to be known as the Durban Moment.

At Natal Biko hit the ground running. He was immediately influenced by, and in turn, influenced this dynamic environment. He was elected to serve on the Student's Representative Council (SRC) of 1966/67, in the year of his admission. Although he initially supported multiracial student groupings, principally the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a number of voices on campus were radically opposed to NUSAS, through which black students had tried for years to have their voices heard but to no avail. This kind of frustration with white liberalism was not altogether unknown to Steve Biko, who had experienced similar disappointment at Lovedale.

Medical Students at the University of Natal (Left to Right: Brigette Savage, Rogers Ragavan, Ben Ngubane, Steve Biko)

Correspondence designating Biko as an SRC delegate at the annual NUSAS Conference

In 1967, Biko participated as an SRC delegate at the annual NUSAS conference held at Rhodes University. A dispute arose at the conference when the host institution prohibited racially mixed accommodation in obedience to the Group Areas Act, one of the laws under apartheid that NUSAS professed to abhor but would not oppose. Instead NUSAS opted to drive on both sides of the road: it condemned Rhodes University officials while cautioning black delegates to act within the limits of the law. For Biko this was another defining moment that struck a raw nerve in him.

Speech by Dr. Saleem Badat, author of Black Man You Are on Your Own, on SASO

Reacting angrily, Biko slated the artificial integration of student politics and rejected liberalism as empty echoes by people who were not committed to rattling the status quo but who skilfully extracted what best suited them “from the exclusive pool of white privileges”. This gave rise to what became known as the Best-able debate: Were white liberals the people best able to define the tempo and texture of black resistance? This debate had a double thrust. On the one hand, it was aimed at disabusing white society of its superiority complex and challenged the liberal establishment to rethink its presumed role as the mouthpiece of the oppressed. On the other, it was designed as an equally frank critique of black society, targeting its passivity that cast blacks in the role of “spectators” in the course of history. The 7th April 1960 saw the banning of the African National Congress and the Pan African Congress and the imprisonment of the leadership of the liberation movement had created a culture of apathy

Bantu Stephen Biko

“ We have set out on a quest for true humanity, and somewhere on the distant horizon we can see the glittering prize. Let us march forth with courage and determination, drawing strength from our common plight and our brotherhood. In time we shall be in a position to bestow upon South Africa the greatest gift possible - a more human face.”

Biko argued that true liberation was possible only when black people were, themselves, agents of change. In his view, this agency was a function of a new identity and consciousness, which was devoid of the inferiority complex that plagued black society. Only when white and black societies addressed issues of race openly would there be some hope for genuine integration and non-racialism.

Transcript of a 1972 Interview with Biko

At the University Christian Movement (UCM) meeting at Stutterheim in 1968, Biko made further inroads into black student politics by targeting key individuals and harnessing support for an exclusively black movement. In 1969, at the University of the North near Pietersburg, and with students of the University of Natal playing a leading role, African students launched a blacks-only student organisation, the South African Student Organisation (SASO). SASO committed itself to the philosophy of black consciousness. Biko was elected president.

Black Student Manifesto

The idea that blacks could define and organise themselves and determine their own destiny through a new political and cultural identity rooted in black consciousness swept through most black campuses, among those who had experienced the frustrations of years of deference to whites. In a short time, SASO became closely identified with 'Black Power' and African humanism and was reinforced by ideas emanating from Diasporan Africa. Successes elsewhere on the continent, which saw a number of countries, achieve independence from their colonial masters also fed into the language of black consciousness.

SASO's Definition of Black Consciousness

Cover of a 1971 SASO Newsletter

“ In 1968 we started forming what is now called SASO... which was firmly based on Black Consciousness, the essence of which was for the black man to elevate his own position by positively looking at those value systems that make him distinctively a man in society” - Biko

Cover of a 1971 SASO Newsletter

Cover of a 1972 SASO Newsletter

Cover of SASO newsletter, 1973

Cover of a 1975 SASO Newsletter

Steve Biko speaks on BCM

The Black People’s Convention By 1971, the influence of SASO had spread well beyond tertiary education campuses. A growing body of people who were part of SASO were also exiting the university system and needed a political home. SASO leaders moved for the establishment of a new wing of their organisation that would embrace broader civil society. The Black People’s Convention (BPC) with just such an aim was launched in 1972. The BPC immediately addressed the problems of black workers, whose unions were not yet recognised by the law. This invariably set the new organisation on a collision path with the security forces. By the end of the year, however, forty-one branches were said to exist. Black church leaders, artists, organised labour and others were becoming increasingly politicised and, despite the banning in 1973 of some of the leading figures in the movement, black consciousness exponents became most outspoken, courageous and provocative in their defiance of white supremacy.

BPC Membership Card

Minutes of the first meeting of the Black People's Convention

In 1974 nine leaders of SASO and BPC were charged with fomenting unrest. The accused used the seventeen-month trial as a platform to state the case of black consciousness in a trial that became known as the Trial of Ideas. They were found guilty and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, although acquitted on the main charge of being party to a revolutionary conspiracy.

SASO/BPC Trial Coverage SASO/BPC Trial Coverage BPC Members

SASO/BPC Coverage

Poster from the 1974 Viva Frelimo Rally

Their conviction simply strengthened the black consciousness movement. Growing influence led to the formation of the South African Students Movement (SASM), which targeted and organised at high school level. SASM was to play a pivotal role in the student uprisings of 1976.

Barney Pityana, Founding SASO Member

In 1972, the year of the birth of the BPC, Biko was expelled from medical school. His political activities had taken a toll on his studies. More importantly, however, according to his friend and comrade Barney Pityana, “his own expansive search for knowledge had gone well beyond the field of medicine.” Biko would later go on to study law through the University of South Africa.

Steve Biko's Order Form for Law Textbooks

Upon leaving university, Biko joined the Durban offices of the Black Community Programmes (BCP), the developmental wing of the Black People Convention, as an employee reporting to Ben Khoapa. The Black Community Programmes engaged in a number of community-based projects and published a yearly called Black Review, which provided an analysis of political trends in the country.

Black Community Programmes Pamphlet

Overview of the BCP

BCP Head, Ben Khoapa

86 Beatrice Street, Former Headquarters of the BCP

"To understand me correctly you have to say that there were no fears expressed" - Biko

Ben Khoapa, Beatrice Street Circa 2007

Biko's Banning Order

When Biko was banned in March 1973, along with Khoapa, Pityana and others, he was deported from Durban to his home town, King William’s Town. Many of the other leaders of SASO, BPC, and BCP were relocated to disparate and isolated locations. Apart from assaulting the capacity of the organisations to function, the bannings were also intended to break the spirit of individual leaders, many of whom would be rendered inactive by the accompanying banning restrictions and thus waste away.

Following his banning, Biko targeted local organic intellectuals whom he engaged with as much vigour as he had engaged the more academic intellectuals at the University of Natal. Only this time, the focus was on giving depth to the practical dimension of BC ideas on development, which had been birthed within SASO and the BPC. He set up the King William’s Town office (No 15 Leopold Street) of the Black Community Programmes office where he stood as Branch Executive. The organisation focused on projects in Health, Education, Job Creation and other areas of community development.

No 15 Leopold Street , Former King William's Town Offices of the BCP

It was not long before his banning order was amended to restrict him from any meaningful association with the BCP. Biko could not meet with more that one person at a time. He could not leave the magisterial area of King William’s Town without permission from the police. He could not participate in public functions nor could he be published or quoted.

Zanempilo Clinic, a BPC Clinic

These restrictions on him and others in the BCM and their regular arrests, forced the development of a multiplicity of layers of leadership within the organisation in order to increase the buoyancy of the organisation. Notwithstanding the challenges, the local Black Community Programme office did well, managing among other achievements to build and operate Zanempilo Clinic, the most advanced community health centre of its time built without public funding. According to Dr. Ramphele, “it was a statement intended to demonstrate how little, with proper planning and organisation, it takes to deliver the most basic of services to our people.” Dr. Ramphele and Dr. Solombela served as resident doctors at Zanempilo Clinic.

Community Member from Njwaxa

Other projects under Biko’s office included Njwaxa Leatherworks Project, a community crèche and a number of other initiatives. Biko was also instrumental in founding in 1975 the Zimele Trust Fund set up to assist political prisoners and their families. Zimele Trust did not discriminate on the basis of party affiliation. In addition, Biko set up the Ginsberg Educational Trust to assist black students. This trust was also a plough-back to a community that had once assisted him with his own education.

Click on the Steve Biko Foundation logo to continue your journey into Biko's extraordinary life. Take a look at Steve Biko: The Black Consciousness Movement, Steve Biko: The Final Days, and Steve Biko: The Legacy.

—Steve Biko Foundation:

Steve Biko: The Inquest

Steve biko foundation, 11 february 1990: mandela's release from prison, africa media online, detention without trial in john vorster square, south african history archive (saha), what happened at the treason trial, steve biko: final days, 9 august 1956: the women's anti-pass march, steve biko: the early years, the signs that defined the apartheid, steve biko: legacy, leadership during the rise and fall of apartheid.

- Publications

- Student Ambassadors

Mubarak Aliyu

August 24th, 2021, steve biko and the philosophy of black consciousness.

0 comments | 6 shares

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

MSc Development Studies candidate, Mubarak Aliyu tells us about the life and work of Steve Biko who pioneered The Black Consciousness Movement and played a crucial role in the resistance to Apartheid in South Africa . Pursuing broad coalitions alongside ideas of Black theology and indigenous values, Biko’s role in the anti-Apartheid struggle can be read as one of philosopher as much as activist.

This post is a winning entry in the LSE student writing competition Black Forgotten Heroes , launched by the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa .

Born 18 December 1946, Steve Biko was a South African activist who pioneered the philosophy of Black Consciousness in the late 1960s. He later founded the South African Students Organisation (SASO) in 1968, in an effort to represent the interests of Black students in the then University of Natal (later KwaZulu-Natal). SASO was a direct response to what Biko saw as the inaction of the National Union of South African Students in representing the needs of Black students.

Biko’s experiences under Apartheid drove his philosophy and political activism. He had witnessed police raids during his childhood and lived through the brutality and intimidation the Apartheid government was known for. Biko’s philosophy focused primarily on liberating the minds of Black people who had been relegated to an inferior status by white power structures, seeing the power struggle in South Africa as ‘a microcosm of the confrontation between the third world and the first world’.

The philosophy of Black consciousness

The Black Consciousness Movement centred on race as a determining factor in the oppression of Black people in South Africa, in response to racial oppression and the dehumanisation of Black people under Apartheid. ‘Black’ as defined by Biko was not limited to Africans, but also included Asians and ‘coloureds’ (South Africans of mixed race including African, European and/or Asian origin), incorporating Black Theology, indigenous values and political organisation against the ruling system.

The movement viewed the liberation of the mind as the primary weapon in the fight for freedom in South Africa, defining Black consciousness as, first, an inward-looking process, where Black people regain the pride stripped away from them by the Apartheid system. His philosophy casts a positive retelling of African history, which has been heavily distorted and vilified by European imperialists in an attempt to construct their colonies. In his writings, he notes that ‘[a] people without a positive history is like a vehicle without an engine’.

At the heart of this thinking is the realisation by blacks that the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed

A necessary step towards restoring dignity to Black people, according to Biko, involves elevating the heroes of African history and promoting African heritage to deconstruct the idea of Africa as the dark continent. Black consciousness seeks to extract the positive values within indigenous African cultures and to make it a standard with which Black people judge themselves – the first form of resistance towards imperialism and Apartheid. According to Biko, ‘what black consciousness seeks to do is to produce at the output end of the process, real black people who do not consider themselves as appendages to white society’.

In Apartheid South Africa, Black consciousness aimed to unite citizens under the main cause of their oppression. Biko’s philosophy goes further to introduce the concept of Black theology, arguing the message in Christianity needs to be taught from the perspective of the oppressed to fit the journey of Black people’s self-realisation. According to Biko, Black theology must preach that it is a sin to allow oneself to be oppressed. Adapting Christianity to African values and belief systems is at the core of doing away with ‘spiritual poverty’.

In 1972, Biko founded the Black People’s Convention as an umbrella organisation for the Black Consciousness Movement, which had begun sweeping through universities across the nation. One year later, he and eight other leaders of the movement were banned by the South African government, which limited Biko to his home of King William’s Town. He continued to defy the banning order, however, by supporting the Convention, leading to several arrests in the following years.

On 21 August 1977, Biko was detained by the police and held at the eastern city of Port Elizabeth, where he was violently tortured and interrogated. By 11 September, he was found naked and chained to a prison cell door. He died in a hospital cell the following day as a result of brain injuries sustained at the hands of the police. Although the details of his torture remain unknown, Biko’s death has been understood by many South Africans as an assassination.

Black consciousness was beyond a movement; it was a philosophy deeply grounded in African Humanism, for which Biko should be considered not only an activist but a philosopher in his own right. His legacy remains one deeply relevant today – of resistance and self-determination in the face of widespread oppression.

All quotes are taken from Steve Biko’s selected writings in his book ‘I write what I like’ .

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

This article was originally published in Africa at LSE .

Featured photo: Steve Biko. Stained glass window by Daan Wildschut in the Saint Anna Church, Heerlen (the Netherlands), ca. 1976

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to email this to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

About the author

Mubarak Aliyu is an MSc Development Studies candidate at LSE, with a specialism in African Development. His research interests include education reform, indigenous knowledge systems and grassroots political organisation.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Posts

Design, Development, and Danes: Lessons from the London Literature Festival

October 26th, 2017.

£0 London: Enjoying London without spending a penny

May 18th, 2022.

Speaking at a House of Commons event for UK Refugee Week 2022

July 5th, 2022.

Meet our 2023 Student Ambassadors!

March 20th, 2023, justice and security research programme, lse’s engagement with south asia.

- The Demand for a Hindu Rastra in Nepal Political parties in Hindu-majority Nepal are increasingly demanding the (re)establishment of Nepal as a Hindu state (rastra). Narendra Thapa looks at how there is a growing presence of Hindu identity politics in Nepal, moving away from its secular Constitution. The forthcoming national elections in India are important not just for India but also […]

- The East End, Local Archives and Global Histories: British Bangladeshi Political Activism in London What role and value do archives of local and community histories have in the study of transnational and global events, especially in the pre-internet era? In this unique post, Michele Benazzo discusses some such documents relating to the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, and how it enlightens us about the engagement of the diaspora Bangladeshi […]

Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers)

Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers) and Summary: The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-Apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Africanist Congress leadership after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960.

Table of Contents

Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement Summary: A Legacy of Empowerment and Resistance

Stephen Bantu Biko , born in 1946 in South Africa, was a prominent anti-apartheid activist and leader of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) . The movement played a crucial role in the fight against apartheid by empowering black South Africans to embrace their identity, instilling pride and self-worth, and promoting resistance against the oppressive regime. This article will discuss Biko’s life, the origins and objectives of the Black Consciousness Movement, and the lasting impact of Biko’s ideas on South Africa and beyond.

Early Life and Influences

Steve Biko grew up in a society deeply divided along racial lines. From an early age, he was exposed to the harsh realities of apartheid, which inspired his lifelong commitment to fighting against racial oppression. As a student at Lovedale High School , Biko encountered the writings of Frantz Fanon , a psychiatrist and philosopher from Martinique who advocated for the liberation of colonized peoples through mental emancipation. Fanon’s ideas influenced Biko’s development of the Black Consciousness philosophy.

Formation of the Black Consciousness Movement

In 1968, Biko co-founded the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) with other like-minded black students. SASO aimed to provide a platform for black students to challenge apartheid and create a sense of unity among them. The organization became the backbone of the Black Consciousness Movement, which sought to empower black South Africans by encouraging them to embrace their identity and value their cultural heritage. By fostering a strong sense of self-worth, the BCM aimed to break down the psychological barriers imposed by apartheid.

Philosophy and Goals

Central to the Black Consciousness Movement was the idea that black South Africans needed to liberate themselves from the mental chains of apartheid. The movement emphasized the importance of self-reliance and self-determination, rejecting the notion that white people were necessary for the liberation of black South Africans. Instead, Biko and the BCM insisted that black people could achieve freedom by developing their own solutions to the problems caused by apartheid.

Biko often spoke about the need to redefine “blackness” as a positive identity, fostering pride and unity among black South Africans. He also believed that social, political, and economic empowerment were essential for the liberation of black people, and that these goals could be achieved through community-based projects and initiatives.

Arrest, Death, and Legacy

The South African government saw Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement as a significant threat to the apartheid regime. In 1973, Biko was banned from participating in political activities and confined to the Eastern Cape. Despite these restrictions, he continued to work clandestinely to advance the goals of the movement.

In August 1977, Biko was arrested, and on September 12, he died from a brain injury sustained while in police custody. His death sparked international outrage and galvanized the anti-apartheid movement, drawing global attention to the brutalities of the apartheid regime.

Today, Steve Biko is remembered as a martyr and a symbol of resistance against racial oppression. The Black Consciousness Movement played a crucial role in the fight against apartheid by empowering black South Africans to take control of their destiny. Biko’s ideas continue to inspire generations of activists worldwide, who strive for social justice and the eradication of racial inequality.

How Essays are Assessed in Grade 12

The essay will be assessed holistically (globally). This approach requires the teacher to score the overall product as a whole, without scoring the component parts separately. This approach encourages the learner to offer an individual opinion by using selected factual evidence to support an argument. The learner will not be required to simply regurgitate ‘facts’ in order to achieve a high mark. This approach discourages learners from preparing ‘model’ answers and reproducing them without taking into account the specific requirements of the question. Holistic marking of the essay credits learners’ opinions supported by evidence. Holistic assessment, unlike content-based marking, does not penalise language inadequacies as the emphasis is on the following:

- The construction of an argument

- The appropriate selection of factual evidence to support such an argument

- The learner’s interpretation of the question.

Steve Biko: Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay s Topics

Topic: the challenge of black consciousness to the apartheid state.

Introduction

K ey Definitions

- Civil protest : Opposition (usually against the current government’s policy) by ordinary citizens of a country

- Uprising : Mass action against government policy

- Bantu Homelands : Regions identified under the apartheid system as so-called homelands for different cultural and linguistic groups.

- Prohibition : order by which something may not be done; prohibit; declared illegal

- Resistance : When an individual or group of people work together against specific domination

- Exile : When someone is banished from their country

(Background)

- “South Africa as an apartheid state in 1970 to 1980

- 1978 PW Botha and launched his “Total Strategy”

- There were limited powers granted to the Colored, Indians and black township councils to ensure economic and political white supremacy

- Despite these reforms, Africans still did not gain any political rights outside their homelands

- Government’s response to violence against government reform policies – the declaration of a state of emergency in 1985:

- Banishment of the ANC and PAC to Sharpeville in 1960 – Underground Organizations

- Leaders of the Liberation Movements were in prisons or in exile

- New legislation – Terrorism Act – increases apartheid government’s power to suppress political opposition •Detention without trial – leads to the deaths of many activists

- Torture of activists in custody

- Increasing militarization within the country

- Bantu education ensures a low-paid labour force •Apartheid regime had total control

- In the late 1960s there was a new kind of resistance – The Black Consciousness Movement

( Nature and Objectives of Black Consciousness )

- In the late 1970s, a new generation of black students began to organize resistance

- Many were students at “forest college” established under the Bantu education system for black students such as the University of Zululand and the University of the North

- They accepted the Black Consciousness philosophy

- The term “black” was a direct dispute with the apartheid term “non-white”.

- “Black people” were all who were oppressed by apartheid – including Indians and coloured people

Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Questions

Question 1: how did the ideas of the black consciousness movement challenge the apartheid regime in the 1970.

How to answer and get good marks?

- Learners must use relevant evidence e.g. Uses relevant evidence that shows a thorough understanding of how the ideas of Black Consciousness challenged the apartheid regime in the 1970s .

- Learners must also use evidence very effectively in an organised paragraph that shows an understanding of the topic

When you answer, you should not ignore the following key facts where applicable:

- Black Consciousness wanted black South Africans to do things for themselves

- Black Consciousness wanted black South Africans to act independently of other races x Self-reliance promoted self-pride among black South Africans

SASO references can also be applicable (if sources are presented)

- SASO was formed to propagate the ideas of Black Consciousness

- To safeguard and promote the interests of black South Africans students

- SASO was based on the philosophy of Black Consciousness

- SASO was associated with Steve Biko

- SASO encouraged black South Africans students to be self-assertive

Question 2: How did the truth and reconciliation commision assist South Africa to come in terms with the past?

- To ensure healing and reconciliation among victims and perpetrators of political violence through confession

- The TRC encouraged the truth to be told

- Hoped to bring about forgiveness through healing

- To bring about ‘Reconciliation and National Unity’ among all South Africans

- Any other relevant response.

Download Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers) on pdf format

View all # History-Grade 12 Study Resources

We have compiled great resources for History Grade 12 students in one place. Find all Question Papers, Notes, Previous Tests, Annual Teaching Plans, and CAPS Documents.

More relevant sources

https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/steve-biko-the-black-consciousness-movement-steve-biko-foundation/AQp2i2l5?hl=en

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Black-Consciousness-movement

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

The Ideology of the Black Consciousness Movement

The emergence of the Black Consciousness movement that swept across the country in the 1970s can best be explained in the context of the events from 1960 onwards. After the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, the National Party (NP) government, which was formed in 1947, intensified its repression to curb widespread civil unrest. It did this by passing harsher laws, extending its use of torture, imprisonment and detentions without trial.

By the late 1960s, the government had jailed, banned or exiled the majority of the Liberation Movement’s leaders. In response to this, an intensified wave of tyranny, and a new set of organisations emerged. These organisations filled the vacuum created by the government’s suppression of the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) after the Sharpeville massacre in 1960. United loosely around a set of ideas described as “Black Consciousness,” these organisations helped to educate and organise Black people, particularly the youth. In fact, the eruption of the Black Consciousness Movement signalled an end to the quiescence that followed the banning of the black political movements.

The BCM urged a defiant rejection of apartheid, especially among Black workers and the youth. The South African Students Organisation (SASO) - an arm of the movement - was founded by Black students who refused to join NUSAS , another student led organization. At the same time, Black workers began to organise trade unions in defiance of anti-strike laws. In 1973, there were strikes throughout the nation, in cities like Durban. The collapse of Portuguese colonialism and the victories of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) in Mozambique, and the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in Angola, stimulated further activity against apartheid. This culminated in the Soweto Uprising of 1976.

In 1976, student protests against Bantu education in Soweto, the Johannesburg informal settlement reserved for Africans, led to a two-year uprising that spread to Black townships across the country. The protests encompassed all Black grievances against the apartheid system, and in that period police reportedly killed many protesters, including schoolchildren. Workers then mobilised to protest police killings of innocent demonstrators.

In the following year, boycotts and unrest among students and teachers grew after Steve Biko , a leader of SASO, died in a Pretoria detention cell. He had been detained by the police under the Terrorism Act, and after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in the 1990s, it was revealed that he was tortured and killed by police. Within a month of Biko’s death, the government had detained scores of people and banned 18 Black Consciousness organizations, as well as two newspapers with a wide Black readership.

The Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa is synonymous with its founder, Biko. From the beginning of Biko’s political life until his death, he remains one of the indisputable icons of the Black struggle against apartheid. As leader of the movement, he instilled courage among the masses to fight an unjust system under the banner of Black Consciousness. Defining Black Consciousness is no mean task. However, a broad understanding of the concept can be made from Biko’s speeches and writings, including those of his close friends and other writers.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

HSTORY T2 Gr. 12 Black Consciousness Essay

Grade 12: The Challenge of Black Consciousness to the Apartheid State (Essay) PPT

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa Essay

Introduction, the system of apartheid, the movement, the influence.

31 years ago, in September 1977, Bantu Stephen Biko, a young black activist, and a fighter against apartheid in South Africa have been killed in police torture chambers. Although he was only one of many young black figures of resistance who have become victims of the special forces of the police in South Africa, he, undoubtedly, was one of the great prophets of his generation. More than 20 000 people from all of the country have gathered to honor his memory at the funeral – having collected, thus, one of the most mass demonstrations in South Africa in the seventies.

Outside of South Africa, the news about his death has stirred up a wave of criticism against the policy of apartheid. Biko called for consciousness awakening, considering it as a means of resistance to oppression, against reconciliation with existence within a system that was based on inequality. He has gone through the way from an activist of one of the student’s organizations, which united black and white students, to the leader and the ideologist of one of the largest protest movements in South Africa which struggled and fought for blacks’ rights. The short life – 30 years which has been taken away – Biko has devoted to the dethronement of apartheid’s defects, the system of a social organization that brought sufferings to the black population of South Africa.

In his representation, the black consciousness is a way to resist racism not only by the rallying of the oppressed black majority, but also by the realized formation of the fundamentally excellent system of social relations: “Black Consciousness is, in essence, the realization by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their operation – the blackness of their skin – and to operate as a group in order to rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude.” 1

This essay despite its introduction is not about one man, it is about the movement that was influenced by a man and played a major role in the revival of resistance to apartheid in South Africa with the main idea that the ideology of Black Consciousness was the basis of African resistances towards white domination.

The system of apartheid has its roots in the 350-year-old history of religious, land, and labor conflicts. In 1652 a group of Dutch immigrants has landed on the Cape of Good Hope and has gradually based a colony with rigid social division, living at the expense of the cultivation of the fertile earth by using the labor of slaves from Africa and Asia. In 1795 the control over territory was grasped by Great Britain, and Dutch-Afrikaners have moved in the depth of the continent and have based their new colonies. In 1899-1902 the British have suppressed a revolt in what is called the Second Boer War. “The war lasted three years and resulted mainly from a combination of personal ambition, conflict over a sea route to India, and most importantly, competition for control of the gold-mining developing in Witwatersrand.” 2

After the declaration in 1910 of the Union of South Africa in which the former territories of British and the Boers have entered, the Afrikaners united under the power of the British monarch, who appeared in the majority had accepted the constitution in which basis laid the principle of the superiority of the white race. This was followed by the legislation that set the racial segregation by which almost all the land has been assigned to white owners, and the African, Asian, and “colored” population has been gradually superseded from the political life.

Following the declaration of the Union of South Africa, South African Native National Congress has been formed, and renamed in 1923 into the African National Congress, for racial discrimination counteraction, the fight for suffrage and equality while the shifting governments of the country steadily rejected its demands. Over half a century the rights of the black population were continuously denied through various acts that put further restrictions with each one released.

For example in 1913 an act called the Natives Land Act “prohibited African purchase or lease of land outside certain areas known as “reserves” 3 The Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923 stated that “Africans were denied freehold property rights and were only allowed in South African cities “For so long as their presence is demanded by the wants of the white population.” 4 After the power was captured in 1948 by the extremist Nationalist party which called itself the Gesuiwerde (purified) National Party formed by D.F. Malan, the system of apartheid became rooted in South Africa until 1994. The politics and policies of apartheid separated South Africa from the rest of the world through systematic and legal segregation upheld and defined by a small but powerful white bureaucracy. 5

During the apartheid regime the culture, not only youth but also public, was frequently imposed from above, instead of being developed naturally on the basis of consciousness and historical continuity. The concept of consciousness imposed from above has been multiplied by the concept of an ethnic accessory which was defined by ideology and was supported by group interests. The policy that was born from the philosophy of the iridescent nation considers the many-sided nature and dynamism of various groups and does not accept the concepts of “natural”, static and invariable group or groups as it was treated by the apartheid’s regime.

This fact allowed the black population to start positioning themselves as the others in the cultural environment that was dominated by the white population. In South Africa, this tendency was shown in the creation of the organization under the name the “Black Consciousness Movement”. Helping black people in clearing the psychological inferiority complex which prevailed centuries over them in their political thinking and activity, and, especially, in their struggle against the domination of the white is mostly attributed to Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement.

The strategy of clearing of white domination and inequality, offered to the black population by Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement, was focused on the principle that carrying out any changes is possible only within the limits of the program developed by the black population. For this purpose, the black population should overcome the feeling of inferiority that was intentionally cultivated by the apartheid regime with the purpose of preserving the white domination in South Africa. “The racism we meet does not only exist on an individual basis; it is also institutionalized to make it look like the South African way of life” 6

It was in this climate that Steve Biko founded the SASO as an alternate to the existing student organizations NUSAS that was not very effective recently. The white leaders of NUSAS (National Union of South African Students) acknowledged that they faced limitations in resisting apartheid and trying to represent blacks as equals 7 . Thus, the black consciousness movement began with the formation of the SASO.

The SASO Manifesto adopted in July 1971, declared that Black Consciousness was “an attitude of mind, a way of life, in which the black man saw himself as self-defined and not as defined by others”. It required “group cohesion and solidarity” so that blacks could become increasingly aware of their collective economic and political power 8 .

Black Consciousness aimed at creating a social order dominated by a black way of life and thought, permeating a certain cultural blackness in all customs, tastes, values, religious and political principles, and all social relationships in their intellectual and moral connotation 9 . The black consciousness movement also brought to light the writings of African leaders that had been so far neglected, some of which included the works of Cheikh Anta Diop, Leopold Senghor on Negritude, Kenneth Kaunda on African humanism, and most importantly, Julius Nyerere on self-reliance and ujamaa or African socialism.

The evolving nature of the Black Consciousness Movement gave the struggle against apartheid a very dynamic front – by providing a conciliatory or revolutionary, a peaceful or violent, a bourgeois or socialist dimension to the confrontation between blacks and whites. By eschewing violence and emphasizing black cultural and psychological emancipation from white domination, the Black Consciousness Movement was initially the vehicle of a black philosophy of pride and self-affirmation invigorated by an ethic of “Christian Liberation”.

As the movement gradually came to recognize that it can be truly effective only if it addresses the real issues of class struggle and the fundamental role that the individual has in abolishing oppressive social structures, the Movement started focusing on the problem of the superstructure. As the most radical impact the black consciousness movement had on the resistance to Apartheid, the movement underlined that the black revolution which was made ineffective by the material structure can be rejuvenated only by the transformation of the black intellect. Thus, the revolution would occur only if the black mind stripped itself from submission to white hegemony and erected on its own foundations the principles of the new moral order.

While the intellectual elite stuck to the subtle points of BC ideology the common masses embraced the movement’s rhetoric in its emotional form, as a form of angry self-assertion 10 . Although the ideology was interpreted by angry youngsters as Black Consciousness and did not exactly resemble the set of complex ideas that had been elaborated by the movement’s leaders, the leaders felt that the expression of anger among the youth was a testimony to their success in inspiring blacks to assert themselves more openly 11 .

However, this anger soon led to the uprising in 1976 at Soweto, in a way that despite being a direct outcome of the movement, it marked the beginning of a decline in its mass influence.

After the 1976 unrest, there was considerable debate as to the ideology of the Black Consciousness Movement and whether the white should be included in the struggle of the black population. Some Black Consciousness leaders continued to advocate excluding whites from the pre-liberation struggle, until 1977, when Biko himself advocated greater cooperation with supportive white organizations. He stated: “We don’t have sufficient groups who can form coalitions with blacks — that is groups of whites — at the present moment. The more such groups will come up, the better to minimize the conflict”. 12 With this statement, Biko moved towards the concept of closer cooperation between white and black groups, which would later be the foundation of the UDF.

- Biko, I Write What I Like, p. 49.

- Lindsay Michie Eades, The End of Apartheid in South Africa (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999) p. 6.

- Lindsay Michie Eades, The End of Apartheid in South Africa (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999) p. 8.

- Lindsay Michie Eades, The End of Apartheid in South Africa (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999) p. 12.

- Biko, I Write What I Like, p. 88.

- Marx, Lessons of Struggle: South African Internal Opposition, 1960-1990. p. 52.

- Gerhart, Black Power in South Africa: The Evolution of an Ideology. p. 270.

- Fatton, Black Consciousness in South Africa: The Dialectics of Ideological Resistance to White Supremacy. p. 60.

- Marx, Lessons of Struggle: South African Internal Opposition, 1960-1990. p.65.

- Marx, Lessons of Struggle: South African Internal Opposition, 1960-1990. p. 65.

- Biko, I Write What I Like, p. 151.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, September 23). Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-consciousness-movement-vs-apartheid-in-south-africa/

"Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa." IvyPanda , 23 Sept. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/black-consciousness-movement-vs-apartheid-in-south-africa/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa'. 23 September.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa." September 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-consciousness-movement-vs-apartheid-in-south-africa/.

1. IvyPanda . "Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa." September 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-consciousness-movement-vs-apartheid-in-south-africa/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa." September 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-consciousness-movement-vs-apartheid-in-south-africa/.

- ‘Cry Freedom’ and ‘Come See the Paradise'

- Power and Politics in Films "Lawrence of Arabia" and "Cry Freedom"

- Lindsay Lohan and Theories of Personality

- Stress related to workplace conditions

- Lindsay Lohan's Personality Analysis

- Apartheid in South Africa

- Israeli Apartheid Ideology Towards Palestinians

- Impact of Apartheid on Education in South Africa

- Apartheid in South: Historical Lenses

- Post-Apartheid Restorative Justice Reconciliation

- Protest, Compliance, Institution, and Individual in Society

- Equality Within the Workforce Issues

- Gangsters in the 50s and Modern

- Women Against Globalization and Anti-Nuke Movement

- Langston Hughes: Artist Impact Analysis

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) The crowd at Steve Biko's funeral, SAHA Original Photograph Collection. On 12 September 1977, the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko died while in the custody of security police. The period leading up to his death, beginning with the June 1976 unrest, had seen some of the most turbulent events in South ...

The O'Malley Archives - Black Consciousness Movement (Mar. 29, 2024) Black Consciousness Movement (BCM), South African anti- apartheid movement that began in the late 1960s. Originating on university campuses, it espoused Black cultural pride and political solidarity while firmly denouncing white liberal inactivity.

The Rise of Black Consciousness. The Black Consciousness movement became one of the most influential anti-apartheid movements of the 1970s in South Africa. While many parts of the African continent gained independence, the apartheid state increased its repression of black liberation movements in the 1960s. In the latter part of the decade, the ...

The Black Consciousness Movement ... History. The Black Consciousness Movement started to develop during the late 1960s, and was led by Steve Biko, Mamphela Ramphele, and Barney Pityana ... This was a compilation of essays that were written by black people for black people.

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was an influential student movement in the 1970s in Apartheid South Africa. The Black Consciousness Movement promoted a new identity and politics of racial solidarity and became the voice and spirit of the anti-apartheid movement at a time when both the African National Congress and the Pan-Africanist Congress had been banned in the wake of the ...

This post is a winning entry in the LSE student writing competition Black Forgotten Heroes, launched by the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa. Born 18 December 1946, Steve Biko was a South African activist who pioneered the philosophy of Black Consciousness in the late 1960s. He later founded the South African Students Organisation (SASO) in ...

Steve Biko. Credit: South African History Online via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0. The philosophy of Black consciousness The Black Consciousness Mo vement centred on race as a determining fact or in the oppression of Black people in South Africa, in r esponse to racial oppression and the dehumanisation of Black people under Apar theid.

Abstract. Beginning with its roots in Bantu Education, this chapter sketches the rise and fall of Black Consciousness. Penfold summarises the diverse and complex influences behind this struggle ideology that was led by Steve Biko. Importantly, Penfold suggests that Black Consciousness must be fundamentally understood as a cultural movement.

Politically, the decade from 1960 to 1970 was a period of deafening silence among black South Africans. The freedom movements of the 1950s had been banned and their leaders imprisoned. In the late 1960s, new young leaders arose, bringing a fresh concept for organizing called "black consciousness.". Foremost among these activists was Steve Biko.

set up to control black students' minds, BC's founders recognized the importance of the mind of the oppressed."10 The segregation of black students at these universities created the conditions needed for a movement like Black Consciousness to emerge. Political scientist David Hirschmann explains, "In a very real sense the B.C. Movement

Mamphela Ramphele, a South African public figure and Biko's then-partner, admits that women did not matter as leaders in the movement and the focus was undeniably on the men even though Black women could be seen as doubly oppressed - by the apartheid system that also oppressed Black men, and by the Black men themselves (Yates, Gqola, and ...

The SASO, BCP & BPC Years. Stephen Bantu Biko was an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. A student leader, he later founded the Black Consciousness Movement which would empower and mobilize much of the urban black population. Since his death in police custody, he has been called a martyr of the anti-apartheid movement.

Biko's ideas became the major rallying point behind a pressure group that became known in South Africa as the BCM. From 17 years of age, up until his death on 12 September 1977, Biko had an illustrious political career spanning about 14 years. He came into the political limelight in 1963, the year that witnessed a rise in the Poqo-led unrest ...

Steve Biko. Credit: South African History Online via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0. The philosophy of Black consciousness. The Black Consciousness Movement centred on race as a determining factor in the oppression of Black people in South Africa, in response to racial oppression and the dehumanisation of Black people under Apartheid.

Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers) and Summary: The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-Apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Africanist Congress leadership after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960.

Black Consciousness ideology in South Africa, as articulated by Biko, sought the attainment of a radical egalitarian and nonracial society. Amongst some of the - espoused principles of the Black Consciousness Movement that defined South African youth politics in the 1970s, is that Black Consciousness emphasised values of black

The emergence of the Black Consciousness movement that swept across the country in the 1970s can best be explained in the context of the events from 1960 onwards. After the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, the National Party (NP) government, which was formed in 1947, intensified its repression to curb widespread civil unrest.

Grade 12: The Challenge of Black Consciousness to the Apartheid State (Essay) PPT. ... HSTORY T2 Gr. 12 Black Consciousness Essay . Free ... History Curriculum Advisors. Download. Type: pptx . Size: 11.68MB . Share this content. Grade 12: The Challenge of Black Consciousness to the Apartheid State (Essay) PPT ...

Introduction. 31 years ago, in September 1977, Bantu Stephen Biko, a young black activist, and a fighter against apartheid in South Africa have been killed in police torture chambers. Although he was only one of many young black figures of resistance who have become victims of the special forces of the police in South Africa, he ...