Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Teaching Research

Main navigation.

As part of PWR’s charge related to the WR 1 and WR 2 requirements, PWR 1 and PWR 2 classes (in collaboration with the library) teach first and second-year students research strategies that provide an introduction to important research practices that they will likely use in their coursework at Stanford and then in future academic and professional work.

This charge accepts as a premise that student research at Stanford still focuses in many disciplines on scholarly texts (journal articles and books), though given the evolving communication landscapes, many student research projects might draw on additional sources, such as websites, podcasts, born-digital texts, etc.

More specifically, in PWR 1, the learning objectives related to research are:

- Students will develop research skills, including the ability to craft a focused research question and to locate, analyze, and evaluate relevant sources, including both print-based and digital sources.

- Students will develop the ability, in research and in writing, to engage a range of sources and perspectives that illuminate a wider conversation about the topic

- (see the complete list of PWR 1 learning objectives here)

In PWR 2, the learning objectives related to research are:

- Students will continue to develop their ability to construct research-based arguments, including collecting, analyzing, and synthesizing data and scholarly and public articles and texts.

- (see the complete list of PWR 2 learning objectives here)

PWR 2, in particular, with its more advanced conversation about research-based arguments, is an appropriate site for inviting students to explore a range of research methods and sources.

In incorporating these research-focused objectives into the foundations of our PWR 1 and PWR 2 curricula, we intend to help students develop an understanding of and experience with research as a means of accessing and analyzing a wide range of sources that will orient them to scholarly and public conversations and ultimately help them create knowledge and contribute to those conversations. In short, we are helping to guide students to conducting research effectively in the context of an R1 university.

That said, PWR classes are not “sources and methods” classes, such as you might find in other departments and programs across campus that foreground specific disciplinary modes of research. As PWR courses teach students from across the disciplines, our goal is not to teach discipline-specific research methodologies. We can certainly encourage students to explore different methodologies and provide context for disciplinary conventions that they will encounter in greater depth later in their studies, but PWR courses are not charged with doing the work of Writing in the Major courses. Our charge is to provide them with an introduction to college-level research and to the ethics of research practice as well as a rhetorical perspective that will help them analyze a wide range of texts.

In keeping with this approach, PWR instructors should be mindful of how they scaffold and encourage research methods in their classrooms. As a program, we are committed to fostering student curiosity, intellectual growth, and purposeful agency in their research process. However, at times students might want to incorporate research methods into their PWR 1 or PWR 2 projects that either do not actually align with the type of project or question under consideration or that present ethical challenges. In most cases, the more problematic methods are associated with research on human subjects. For this reason, we ask instructors to adhere to certain guidelines in teaching research methodologies:

- Teaching strategy: if a student is interested in a topic related to vulnerable populations, steer them toward data sets or interviews conducted by others. That way they can still have access to some of the primary research on these individuals without conducting it themselves.

- Teaching strategy: Ask your students what they would gain from this sort of method that wouldn’t be gained from finding similar information – probably from a longer-term study with a larger sample size – in secondary research. Ask them to carefully consider and revise their research question to ensure that this methodology best supports generating a productive answer for that question.

- Teaching strategy: You might have students who want to conduct interviews or surveys complete the CITI training tutorial .

- Teaching strategy: Review drafts of all surveys and interview questions; if not everyone in your class is engaged in this sort of primary research, set up peer consultation groups or special out-of-class group conferences to promote feedback and revision, asking students in these groups to serve as beta-testers/focus groups about the survey and interview questions.

- Teaching strategy: Work with students to identify the target demographic and a sample size goal that is appropriate to the scope of the research, the research process timeline, and the resources available.

If you have any questions about a proposed student research topic or methods, please set up an appointment to talk with the Associate Director or one of the Directors for guidance as early in the research process as possible.

Additional resources to help students who are interested in conducting this sort of primary research will be available on Teaching Writing soon.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.1 The Purpose of Research Writing

Learning objectives.

- Identify reasons to research writing projects.

- Outline the steps of the research writing process.

Why was the Great Wall of China built? What have scientists learned about the possibility of life on Mars? What roles did women play in the American Revolution? How does the human brain create, store, and retrieve memories? Who invented the game of football, and how has it changed over the years?

You may know the answers to these questions off the top of your head. If you are like most people, however, you find answers to tough questions like these by searching the Internet, visiting the library, or asking others for information. To put it simply, you perform research.

Whether you are a scientist, an artist, a paralegal, or a parent, you probably perform research in your everyday life. When your boss, your instructor, or a family member asks you a question that you do not know the answer to, you locate relevant information, analyze your findings, and share your results. Locating, analyzing, and sharing information are key steps in the research process, and in this chapter, you will learn more about each step. By developing your research writing skills, you will prepare yourself to answer any question no matter how challenging.

Reasons for Research

When you perform research, you are essentially trying to solve a mystery—you want to know how something works or why something happened. In other words, you want to answer a question that you (and other people) have about the world. This is one of the most basic reasons for performing research.

But the research process does not end when you have solved your mystery. Imagine what would happen if a detective collected enough evidence to solve a criminal case, but she never shared her solution with the authorities. Presenting what you have learned from research can be just as important as performing the research. Research results can be presented in a variety of ways, but one of the most popular—and effective—presentation forms is the research paper . A research paper presents an original thesis, or purpose statement, about a topic and develops that thesis with information gathered from a variety of sources.

If you are curious about the possibility of life on Mars, for example, you might choose to research the topic. What will you do, though, when your research is complete? You will need a way to put your thoughts together in a logical, coherent manner. You may want to use the facts you have learned to create a narrative or to support an argument. And you may want to show the results of your research to your friends, your teachers, or even the editors of magazines and journals. Writing a research paper is an ideal way to organize thoughts, craft narratives or make arguments based on research, and share your newfound knowledge with the world.

Write a paragraph about a time when you used research in your everyday life. Did you look for the cheapest way to travel from Houston to Denver? Did you search for a way to remove gum from the bottom of your shoe? In your paragraph, explain what you wanted to research, how you performed the research, and what you learned as a result.

Research Writing and the Academic Paper

No matter what field of study you are interested in, you will most likely be asked to write a research paper during your academic career. For example, a student in an art history course might write a research paper about an artist’s work. Similarly, a student in a psychology course might write a research paper about current findings in childhood development.

Having to write a research paper may feel intimidating at first. After all, researching and writing a long paper requires a lot of time, effort, and organization. However, writing a research paper can also be a great opportunity to explore a topic that is particularly interesting to you. The research process allows you to gain expertise on a topic of your choice, and the writing process helps you remember what you have learned and understand it on a deeper level.

Research Writing at Work

Knowing how to write a good research paper is a valuable skill that will serve you well throughout your career. Whether you are developing a new product, studying the best way to perform a procedure, or learning about challenges and opportunities in your field of employment, you will use research techniques to guide your exploration. You may even need to create a written report of your findings. And because effective communication is essential to any company, employers seek to hire people who can write clearly and professionally.

Writing at Work

Take a few minutes to think about each of the following careers. How might each of these professionals use researching and research writing skills on the job?

- Medical laboratory technician

- Small business owner

- Information technology professional

- Freelance magazine writer

A medical laboratory technician or information technology professional might do research to learn about the latest technological developments in either of these fields. A small business owner might conduct research to learn about the latest trends in his or her industry. A freelance magazine writer may need to research a given topic to write an informed, up-to-date article.

Think about the job of your dreams. How might you use research writing skills to perform that job? Create a list of ways in which strong researching, organizing, writing, and critical thinking skills could help you succeed at your dream job. How might these skills help you obtain that job?

Steps of the Research Writing Process

How does a research paper grow from a folder of brainstormed notes to a polished final draft? No two projects are identical, but most projects follow a series of six basic steps.

These are the steps in the research writing process:

- Choose a topic.

- Plan and schedule time to research and write.

- Conduct research.

- Organize research and ideas.

- Draft your paper.

- Revise and edit your paper.

Each of these steps will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. For now, though, we will take a brief look at what each step involves.

Step 1: Choosing a Topic

As you may recall from Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , to narrow the focus of your topic, you may try freewriting exercises, such as brainstorming. You may also need to ask a specific research question —a broad, open-ended question that will guide your research—as well as propose a possible answer, or a working thesis . You may use your research question and your working thesis to create a research proposal . In a research proposal, you present your main research question, any related subquestions you plan to explore, and your working thesis.

Step 2: Planning and Scheduling

Before you start researching your topic, take time to plan your researching and writing schedule. Research projects can take days, weeks, or even months to complete. Creating a schedule is a good way to ensure that you do not end up being overwhelmed by all the work you have to do as the deadline approaches.

During this step of the process, it is also a good idea to plan the resources and organizational tools you will use to keep yourself on track throughout the project. Flowcharts, calendars, and checklists can all help you stick to your schedule. See Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.2 “Steps in Developing a Research Proposal” for an example of a research schedule.

Step 3: Conducting Research

When going about your research, you will likely use a variety of sources—anything from books and periodicals to video presentations and in-person interviews.

Your sources will include both primary sources and secondary sources . Primary sources provide firsthand information or raw data. For example, surveys, in-person interviews, and historical documents are primary sources. Secondary sources, such as biographies, literary reviews, or magazine articles, include some analysis or interpretation of the information presented. As you conduct research, you will take detailed, careful notes about your discoveries. You will also evaluate the reliability of each source you find.

Step 4: Organizing Research and the Writer’s Ideas

When your research is complete, you will organize your findings and decide which sources to cite in your paper. You will also have an opportunity to evaluate the evidence you have collected and determine whether it supports your thesis, or the focus of your paper. You may decide to adjust your thesis or conduct additional research to ensure that your thesis is well supported.

Remember, your working thesis is not set in stone. You can and should change your working thesis throughout the research writing process if the evidence you find does not support your original thesis. Never try to force evidence to fit your argument. For example, your working thesis is “Mars cannot support life-forms.” Yet, a week into researching your topic, you find an article in the New York Times detailing new findings of bacteria under the Martian surface. Instead of trying to argue that bacteria are not life forms, you might instead alter your thesis to “Mars cannot support complex life-forms.”

Step 5: Drafting Your Paper

Now you are ready to combine your research findings with your critical analysis of the results in a rough draft. You will incorporate source materials into your paper and discuss each source thoughtfully in relation to your thesis or purpose statement.

When you cite your reference sources, it is important to pay close attention to standard conventions for citing sources in order to avoid plagiarism , or the practice of using someone else’s words without acknowledging the source. Later in this chapter, you will learn how to incorporate sources in your paper and avoid some of the most common pitfalls of attributing information.

Step 6: Revising and Editing Your Paper

In the final step of the research writing process, you will revise and polish your paper. You might reorganize your paper’s structure or revise for unity and cohesion, ensuring that each element in your paper flows into the next logically and naturally. You will also make sure that your paper uses an appropriate and consistent tone.

Once you feel confident in the strength of your writing, you will edit your paper for proper spelling, grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting. When you complete this final step, you will have transformed a simple idea or question into a thoroughly researched and well-written paper you can be proud of!

Review the steps of the research writing process. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In which steps of the research writing process are you allowed to change your thesis?

- In step 2, which types of information should you include in your project schedule?

- What might happen if you eliminated step 4 from the research writing process?

Key Takeaways

- People undertake research projects throughout their academic and professional careers in order to answer specific questions, share their findings with others, increase their understanding of challenging topics, and strengthen their researching, writing, and analytical skills.

- The research writing process generally comprises six steps: choosing a topic, scheduling and planning time for research and writing, conducting research, organizing research and ideas, drafting a paper, and revising and editing the paper.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Writing Your Research Proposal

5 Essentials You Need To Keep In Mind

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

Writing a high-quality research proposal that “sells” your study and wins the favour (and approval) of your university is no small task. In this post, we’ll share five critical dos and don’ts to help you navigate the proposal writing process.

This post is based on an extract from our online course , Research Proposal Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the process of developing an A-grade proposal, step by step, with plain-language explanations and loads of examples. If it’s your first time writing a research proposal, you definitely want to check that out.

Overview: 5 Proposal Writing Essentials

- Understand your university’s requirements and restrictions

- Have a clearly articulated research problem

- Clearly communicate the feasibility of your research

- Pay very close attention to ethics policies

- Focus on writing critically and concisely

1. Understand the rules of the game

All too often, we see students going through all the effort of finding a unique and valuable topic and drafting a meaty proposal, only to realise that they’ve missed some critical information regarding their university’s requirements.

Every university is different, but they all have some sort of requirements or expectations regarding what students can and can’t research. For example:

- Restrictions regarding the topic area that can be research

- Restrictions regarding data sources – for example, primary or secondary

- Requirements regarding methodology – for example, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods-based research

- And most notably, there can be varying expectations regarding topic originality – does your topic need to be super original or not?

The key takeaway here is that you need to thoroughly read through any briefing documents provided by your university. Also, take a look at past dissertations or theses from your program to get a feel for what the norms are . Long story short, make sure you understand the rules of the game before you start playing.

2. Have a clearly articulated research problem

As we’ve explained many times on this blog, all good research starts with a strong research problem – without a problem, you don’t have a clear justification for your research. Therefore, it’s essential that you have clarity regarding the research problem you’re going to address before you start drafting your proposal. From the research problem , the research gap emerges and from the research gap, your research aims , objectives and research questions emerge. These then guide your entire dissertation from start to end.

Needless to say, all of this starts with the literature – in other words, you have to spend time reading the existing literature to understand the current state of knowledge. You can’t skip this all-important step. All too often, we see students make the mistake of trying to write up a proposal without having a clear understanding of the current state of the literature, which is just a recipe for disaster. You’ve got to take the time to understand what’s already been done before you can propose doing something new.

3. Demonstrate the feasibility of your research

One of the key concerns that reviewers or assessors have when deciding to approve or reject a research proposal is the practicality/feasibility of the proposed research , given the student’s resources (which are usually pretty limited). You can have a brilliant research topic that’s super original and valuable, but if there is any question about whether the project is something that you can realistically pull off, you’re going to run into issues when it comes to getting your proposal accepted.

So, what does this mean for you?

First, you need to make sure that the research topic you’ve chosen and the methodology you’re planning to use is 100% safe in terms of feasibility . In other words, you need to be super certain that you can actually pull off this study. Of greatest importance here is the data collection and analysis aspect – in other words, will you be able to get access to the data you need, and will you be able to analyse it?

Second, assuming you’re 100% confident that you can pull the research off, you need to clearly communicate that in your research proposal. To do this, you need to proactively think about all the concerns the reviewer or supervisor might have and ensure that you clearly address these in your proposal. Remember, the proposal is a one-way communication – you get one shot (per submission) to make your case, and there’s generally no Q&A opportunity . So, make it clear what you’ll be doing, what the potential risks are and how you’ll manage those risks to ensure that your study goes according to plan.

If you have the word count available, it’s a good idea to present a project plan , ideally using something like a Gantt chart. You can also consider presenting a risk register , where you detail the potential risks, their likelihood and impact, and your mitigation and response actions – this will show the assessor that you’ve really thought through the practicalities of your proposed project. If you want to learn more about project plans and risk registers, we cover these in detail in our proposal writing course, Research Proposal Bootcamp , and we also provide templates that you can use.

Need a helping hand?

4. Pay close attention to ethics policies

This one’s a biggy – and it can often be a dream crusher for students with lofty research ideas. If there’s one thing that will sink your research proposal faster than anything else, it’s non-compliance with your university’s research ethics policy . This is simply a non-negotiable, so don’t waste your time thinking you can convince your institution otherwise. If your proposed research runs against any aspect of your institution’s ethics policies, it’s a no-go.

The ethics requirements for dissertations can vary depending on the field of study, institution, and country, so we can’t give you a list of things you need to do, but some common requirements that you should be aware of include things like:

- Informed consent – in other words, getting permission/consent from your study’s participants and allowing them to opt out at any point

- Privacy and confidentiality – in other words, ensuring that you manage the data securely and respect people’s privacy

- If your research involves animals (as opposed to people), you’ll need to explain how you’ll ensure ethical treatment, how you’ll reduce harm or distress, etc.

One more thing to keep in mind is that certain types of research may be acceptable from an ethics perspective, but will require additional levels of approval . For example, if you’re planning to study any sort of vulnerable population (e.g., children, the elderly, people with mental health conditions, etc.), this may be allowed in principle but requires additional ethical scrutiny. This often involves some sort of review board or committee, which slows things down quite a bit. Situations like this aren’t proposal killers, but they can create a much more rigid environment , so you need to consider whether that works for you, given your timeline.

5. Write critically and concisely

The final item on the list is more generic but just as important to the success of your research proposal – that is, writing critically and concisely .

All too often, students fall short in terms of critical writing and end up writing in a very descriptive manner instead. We’ve got a detailed blog post and video explaining the difference between these two types of writing, so we won’t go into detail here. However, the simplest way to distinguish between the two types of writing is that descriptive writing focuses on the what , while analytical writing draws out the “so what” – in other words, what’s the impact and relevance of each point that you’re making to the bigger issue at hand.

In the case of a research proposal, the core task at hand is to convince the reader that your planned research deserves a chance . To do this, you need to show the reviewer that your research will (amongst other things) be original , valuable and practical . So, when you’re writing, you need to keep this core objective front of mind and write with purpose, taking every opportunity to link what you’re writing about to that core purpose of the proposal.

The second aspect in relation to writing is to write concisely . All too often, students ramble on and use far more word count than is necessary. Part of the problem here is that their writing is just too descriptive (the previous point) and part of the issue is just a lack of editing .

The keyword here is editing – in other words, you don’t need to write the most concise version possible on your first try – if anything, we encourage you to just thought vomit as much as you can in the initial stages of writing. Once you’ve got everything down on paper, then you can get down to editing and trimming down your writing . You need to get comfortable with this process of iteration and revision with everything you write – don’t try to write the perfect first draft. First, get the thoughts out of your head and onto the paper , then edit. This is a habit that will serve you well beyond your proposal, into your actual dissertation or thesis.

Wrapping Up

To recap, the five essentials to keep in mind when writing up your research proposal include:

If you want to learn more about how to craft a top-notch research proposal, be sure to check out our online course for a comprehensive, step-by-step guide. Alternatively, if you’d like to get hands-on help developing your proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey, step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

Thanks alot, I am really getting you right with focus on how to approach my research work soon, Insha Allah, God blessed you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Search Close search bar

- Open menu Close menu

The role of research in teacher education: Reviewing the evidence

Report 01 Jan 2014 1 Comments

- Education and learning

While many might assume that research should make some contribution to high quality teacher education, BERA and RSA ask precisely what that contribution should be: to initial teacher education, to teachers’ continuing professional development and to school improvement. They also ask how different teacher education systems currently engage with research and what international evidence there is that linking research and teacher education is effective.

Engage with our research

At a time when virtually every government around the world is asking how it can improve the quality of its teaching force,the British Educational Research Association (BERA) and the RSA have come together to consider what contribution research can make to that improvement.

High quality teaching is now widely acknowledged to be the most important school-level factor influencing student achievement. This in turn has focused attention on the importance of teacher education, from initial training and induction for beginning teachers, to on-going professional development to help update teachers’ knowledge, deepen their understanding and advance their skills as expert practitioners. Policy-makers around the world have approached the task of teacher preparation and professional development in different ways, reflecting their distinctive values, beliefs and assumptions about the nature of professional knowledge and how and where such learning takes place.

At a time when teacher education is under active development across the four nations of the United Kingdom, an important question for all those seeking to improve the quality of teaching and learning is how to boost the use of research to inform the design, structure and content of teacher education programmes.

The Inquiry aims to shape debate, inform policy and influence practice by investigating the contribution of research in teacher education and examining the potential benefits of research-based skills and knowledge for improving school performance and student outcomes.

There are four main ways that research can contribute to programmes of teacher education:

- The content of such programmes may be informed by research-based knowledge and scholarship, emanating from a range of academic disciplines and epistemological traditions.

- Research can be used to inform the design and structure of teacher education programmes.

- Teachers and teacher educators can be equipped to engage with and be discerning consumers of research.

- Teachers and teacher educators may be equipped to conduct their own research, individually and collectively, to investigate the impact of particular interventions or to explore the positive and negative effects of educational practice.

At present, there are pockets of excellent practice in teacher education in different parts of the UK, including some established models and some innovative new programmes based on the model of ‘research-informed clinical practice’. However, in each of the four nations there is not yet a coherent and systematic approach to professional learning from the beginning of teacher training and sustained throughout teachers’ working lives.

There has been a strong focus on the use of data to inform teaching and instruction over the past 20 years. There now needs to be a sustained emphasis on creating ‘research-rich’ and ‘evidence-rich’ (rather than simply ‘data-rich’) schools and classrooms. Teachers need to be equipped to interrogate data and evidence from different sources, rather than just describing the data or trends in attainment.

The priority for all stakeholders (Government, national agencies, schools, universities and teachers’ organisations) should be to work together to create a national strategy for teacher education and professional learning that reflects the principles of ‘research-informed clinical practice’. Rather than privileging one type of institutional approach, these principles should be applied to all institutional settings and organisations where teacher education and professional learning takes place.

Further consideration needs to be given to the best ways of developing such a strategy, in consultation with all the relevant partners.

Contributors

Join the discussion

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

intrestung info

Page 0 of 1

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Importance of Research Proposals in academic writing – with example

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Definition

- 3 Bachelor/Master Thesis

- 4 Examples of A Research Proposal

- 5 In a Nutshell

The research proposal example is a complex task that requires an understanding of multiple skills. The paper aims to deliver a brief overview of the research you will conduct. The research proposal example explains the main reasons why your research will be useful to the reader and to society in general. The research proposal example contains the main idea , the reason why you are doing the research , and the methodology you will use. A great research proposal example is especially important if you hope to get funding for your research.

This article gives a clear and simple guide to writing a research proposal. The research proposal example is an important part of beginning your research in college or university. If your supervisor does not approve it, you may not begin your research. Here is a detailed guide on how the process of coming up with a research proposal works.

What should a research proposal example include?

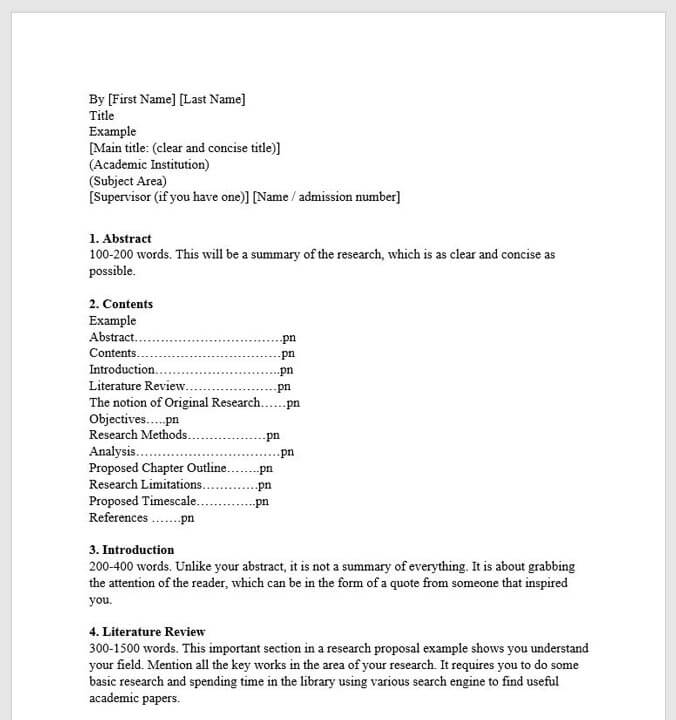

The research proposal example should include 7 main sections. You can find a detailed description of each section at our blog article about research proposal samples .

- Research overview

- Research context

- Research questions

- Research methods

- The significance of the research

It’s a clear outline of the topic/issues you’re going to cover in your thesis later on. While you may include other sections, these seven sections must always appear in the most basic research proposal examples.

What is the format of a research proposal?

During the first reading, your supervisors will most likely take a quick look at it to determine if it is worth going over or not. As such, you need to take full advantage of the title page and table of contents to include as much information as possible while also being mindful of whitespace. A great first impression is vital.

How long should the research proposal be?

Your research proposal example will typically be just 2500 words plus or minus a few hundred words. Having trouble getting started? Check out some tips for overcoming writer’s block .

Tip: The exact requirements and word count might change depending on the specific research body to which you are sending the research proposal. So be sure to double check.

Can the staff comment on a draft proposal?

Yes! The school recognizes that your research topic is still in development and you might need help to polish it up. It’s important that you take on all feedback- especially when it comes to refining your research questions . You will be able to contact your research supervisor who has the expertise to discuss your research proposal example and give you tips on how to make improvements to it.

What is the purpose of a research proposal example?

Your research proposal is the basis of your bachelor’s thesis and any other academic qualifying paper that you’re required to write. The main reason you write a research proposal example is to convince the reader of why your project is valuable and of your competence in that area. Your reader needs to be convinced that this is not yet another useless piece of writing, but a profound piece of research, which will serve a real-world purpose.

What tenses is a research proposal example written in?

A research proposal example is a piece of writing indicating what you intend to do at some point in the future. As such, the research proposal example is written in the present or future tense. For some more in-depth information about writing and structuring your research proposal sample , head over to our blog post.

Why is learning how to write a good research proposal an important skill?

Research proposal writing is an important skill to master. You will be writing research proposals throughout your professional career from your bachelor’s thesis to your PhD. With the right skills, you will be able to convince others about a new product you wish to launch or a service and why it is worth their time.

Bachelor/Master Thesis

How important is a proposal example for academic writing?

The main purpose of your research proposal example is to convince the reader why your project is important and your competence in the chosen area of research. Writing a research proposal can be easy if you have a good research proposal example. Many students face problems when trying to come up with it alone. This is why using a research proposal example is so important. Here are some of the benefits of using a research proposal example:

See how the overall structure looks like

A research proposal example will show you which parts you need to include in your research proposal. You will understand how each part should be organized and what information needs to be included.

Understand the most important parts

A research proposal example contains the most important parts that must be included. You will understand which parts to include and how to include them.

Avoid common mistakes

A research proposal example is a great way to identify common mistakes that people make when writing research proposals. Amongst the mistakes is a failure to focus on the main problem of the research, failing to provide the required arguments in support of the proposal, and not using a given format.

Paper printing & binding

You are already done writing your research paper and need a high quality printing & binding service? Then you are right to choose BachelorPrint! Check out our 24-hour online printing service. For more information click the button below :

Examples of A Research Proposal

- Research Proposal Example 1

- Research Proposal Example 2

Research topic A working title that describes the content and direction of the project Project Description Background What is known and what is unknown in your chosen area of research.

Aims What you intend to know, demonstrate, test, investigate, examine? List the aims logically.

Methodology How do you intend to achieve your aims? What do you require? Are there barriers? Are there human or animal ethics involved? Is travel required? Expected outcomes, Why is this research important? What do expect from the research? What are the outcomes you expect? You need to show the research is original and worth looking into.

Timetable Indicate the timeframe of each broad stage of the research, including the data collection, literature review, production, modeling, review and analysis, testing, reporting, thesis writing, and submission date.

In a Nutshell

- Choose a realistic area of research

- Take time to go through a research proposal example

- Always speak to academic staff to provide you with guidance

- Do not plagiarize any research proposal example you find

- Think about the budgetary requirements when creating a research proposal

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

How to write a research proposal?

Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Devika Rani Duggappa

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

INTRODUCTION

A clean, well-thought-out proposal forms the backbone for the research itself and hence becomes the most important step in the process of conduct of research.[ 1 ] The objective of preparing a research proposal would be to obtain approvals from various committees including ethics committee [details under ‘Research methodology II’ section [ Table 1 ] in this issue of IJA) and to request for grants. However, there are very few universally accepted guidelines for preparation of a good quality research proposal. A search was performed with keywords such as research proposal, funding, qualitative and writing proposals using search engines, namely, PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus.

Five ‘C’s while writing a literature review

BASIC REQUIREMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

A proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new paradigm will it add to the literature, while specifying the question that the research will answer, establishing its significance, and the implications of the answer.[ 2 ] The proposal must be capable of convincing the evaluation committee about the credibility, achievability, practicality and reproducibility (repeatability) of the research design.[ 3 ] Four categories of audience with different expectations may be present in the evaluation committees, namely academic colleagues, policy-makers, practitioners and lay audiences who evaluate the research proposal. Tips for preparation of a good research proposal include; ‘be practical, be persuasive, make broader links, aim for crystal clarity and plan before you write’. A researcher must be balanced, with a realistic understanding of what can be achieved. Being persuasive implies that researcher must be able to convince other researchers, research funding agencies, educational institutions and supervisors that the research is worth getting approval. The aim of the researcher should be clearly stated in simple language that describes the research in a way that non-specialists can comprehend, without use of jargons. The proposal must not only demonstrate that it is based on an intelligent understanding of the existing literature but also show that the writer has thought about the time needed to conduct each stage of the research.[ 4 , 5 ]

CONTENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

The contents or formats of a research proposal vary depending on the requirements of evaluation committee and are generally provided by the evaluation committee or the institution.

In general, a cover page should contain the (i) title of the proposal, (ii) name and affiliation of the researcher (principal investigator) and co-investigators, (iii) institutional affiliation (degree of the investigator and the name of institution where the study will be performed), details of contact such as phone numbers, E-mail id's and lines for signatures of investigators.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations.[ 4 ]

Introduction

It is also sometimes termed as ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract’. Introduction is an initial pitch of an idea; it sets the scene and puts the research in context.[ 6 ] The introduction should be designed to create interest in the reader about the topic and proposal. It should convey to the reader, what you want to do, what necessitates the study and your passion for the topic.[ 7 ] Some questions that can be used to assess the significance of the study are: (i) Who has an interest in the domain of inquiry? (ii) What do we already know about the topic? (iii) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (iv) How will this research add to knowledge, practice and policy in this area? Some of the evaluation committees, expect the last two questions, elaborated under a separate heading of ‘background and significance’.[ 8 ] Introduction should also contain the hypothesis behind the research design. If hypothesis cannot be constructed, the line of inquiry to be used in the research must be indicated.

Review of literature

It refers to all sources of scientific evidence pertaining to the topic in interest. In the present era of digitalisation and easy accessibility, there is an enormous amount of relevant data available, making it a challenge for the researcher to include all of it in his/her review.[ 9 ] It is crucial to structure this section intelligently so that the reader can grasp the argument related to your study in relation to that of other researchers, while still demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. It is preferable to summarise each article in a paragraph, highlighting the details pertinent to the topic of interest. The progression of review can move from the more general to the more focused studies, or a historical progression can be used to develop the story, without making it exhaustive.[ 1 ] Literature should include supporting data, disagreements and controversies. Five ‘C's may be kept in mind while writing a literature review[ 10 ] [ Table 1 ].

Aims and objectives

The research purpose (or goal or aim) gives a broad indication of what the researcher wishes to achieve in the research. The hypothesis to be tested can be the aim of the study. The objectives related to parameters or tools used to achieve the aim are generally categorised as primary and secondary objectives.

Research design and method

The objective here is to convince the reader that the overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the research problem and to impress upon the reader that the methodology/sources chosen are appropriate for the specific topic. It should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

In this section, the methods and sources used to conduct the research must be discussed, including specific references to sites, databases, key texts or authors that will be indispensable to the project. There should be specific mention about the methodological approaches to be undertaken to gather information, about the techniques to be used to analyse it and about the tests of external validity to which researcher is committed.[ 10 , 11 ]

The components of this section include the following:[ 4 ]

Population and sample

Population refers to all the elements (individuals, objects or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe,[ 12 ] and sample refers to subset of population which meets the inclusion criteria for enrolment into the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined. The details pertaining to sample size are discussed in the article “Sample size calculation: Basic priniciples” published in this issue of IJA.

Data collection

The researcher is expected to give a detailed account of the methodology adopted for collection of data, which include the time frame required for the research. The methodology should be tested for its validity and ensure that, in pursuit of achieving the results, the participant's life is not jeopardised. The author should anticipate and acknowledge any potential barrier and pitfall in carrying out the research design and explain plans to address them, thereby avoiding lacunae due to incomplete data collection. If the researcher is planning to acquire data through interviews or questionnaires, copy of the questions used for the same should be attached as an annexure with the proposal.

Rigor (soundness of the research)

This addresses the strength of the research with respect to its neutrality, consistency and applicability. Rigor must be reflected throughout the proposal.

It refers to the robustness of a research method against bias. The author should convey the measures taken to avoid bias, viz. blinding and randomisation, in an elaborate way, thus ensuring that the result obtained from the adopted method is purely as chance and not influenced by other confounding variables.

Consistency

Consistency considers whether the findings will be consistent if the inquiry was replicated with the same participants and in a similar context. This can be achieved by adopting standard and universally accepted methods and scales.

Applicability

Applicability refers to the degree to which the findings can be applied to different contexts and groups.[ 13 ]

Data analysis

This section deals with the reduction and reconstruction of data and its analysis including sample size calculation. The researcher is expected to explain the steps adopted for coding and sorting the data obtained. Various tests to be used to analyse the data for its robustness, significance should be clearly stated. Author should also mention the names of statistician and suitable software which will be used in due course of data analysis and their contribution to data analysis and sample calculation.[ 9 ]

Ethical considerations

Medical research introduces special moral and ethical problems that are not usually encountered by other researchers during data collection, and hence, the researcher should take special care in ensuring that ethical standards are met. Ethical considerations refer to the protection of the participants' rights (right to self-determination, right to privacy, right to autonomy and confidentiality, right to fair treatment and right to protection from discomfort and harm), obtaining informed consent and the institutional review process (ethical approval). The researcher needs to provide adequate information on each of these aspects.

Informed consent needs to be obtained from the participants (details discussed in further chapters), as well as the research site and the relevant authorities.

When the researcher prepares a research budget, he/she should predict and cost all aspects of the research and then add an additional allowance for unpredictable disasters, delays and rising costs. All items in the budget should be justified.

Appendices are documents that support the proposal and application. The appendices will be specific for each proposal but documents that are usually required include informed consent form, supporting documents, questionnaires, measurement tools and patient information of the study in layman's language.

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your proposal. Although the words ‘references and bibliography’ are different, they are used interchangeably. It refers to all references cited in the research proposal.

Successful, qualitative research proposals should communicate the researcher's knowledge of the field and method and convey the emergent nature of the qualitative design. The proposal should follow a discernible logic from the introduction to presentation of the appendices.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Privacy Policy