- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Life and personality

- Religious scandal and the coup of the oligarchs

- The perceived fragility of Athenian democracy

- The Athenian ideal of free speech

- Plato’s Apology

- The impression created by Aristophanes

- The human resistance to self-reflection

- Socrates’ criticism of democracy

- Socrates’ radical reconception of piety

- The danger posed by Socrates

- Socrates versus Plato

- The legacy of Socrates

Who was Socrates?

What did socrates teach, how do we know what socrates thought, why did athens condemn socrates to death, why didn’t socrates try to escape his death sentence.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia - Socrates

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Socrates

- PBS LearningMedia - Socrates and the Early Senate | The Greeks

- Ancient Origins - Socrates: The Father of Western Philosophy

- World History Encyclopedia - Biography of Socrates

- The Open University - The Life of Socrates

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Socrates (469–399 BC)

- Age of the Sage - Transmitting the Wisdoms of the Ages - Biography of Socrates

- Florida State College at Jacksonville Pressbooks - Philosophy in the Humanities - Socrates

- Humanities LibreTexts - The Life of Socrates

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Biography of Socrates

- Socrates - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Socrates - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

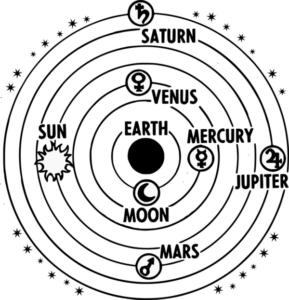

- Table Of Contents

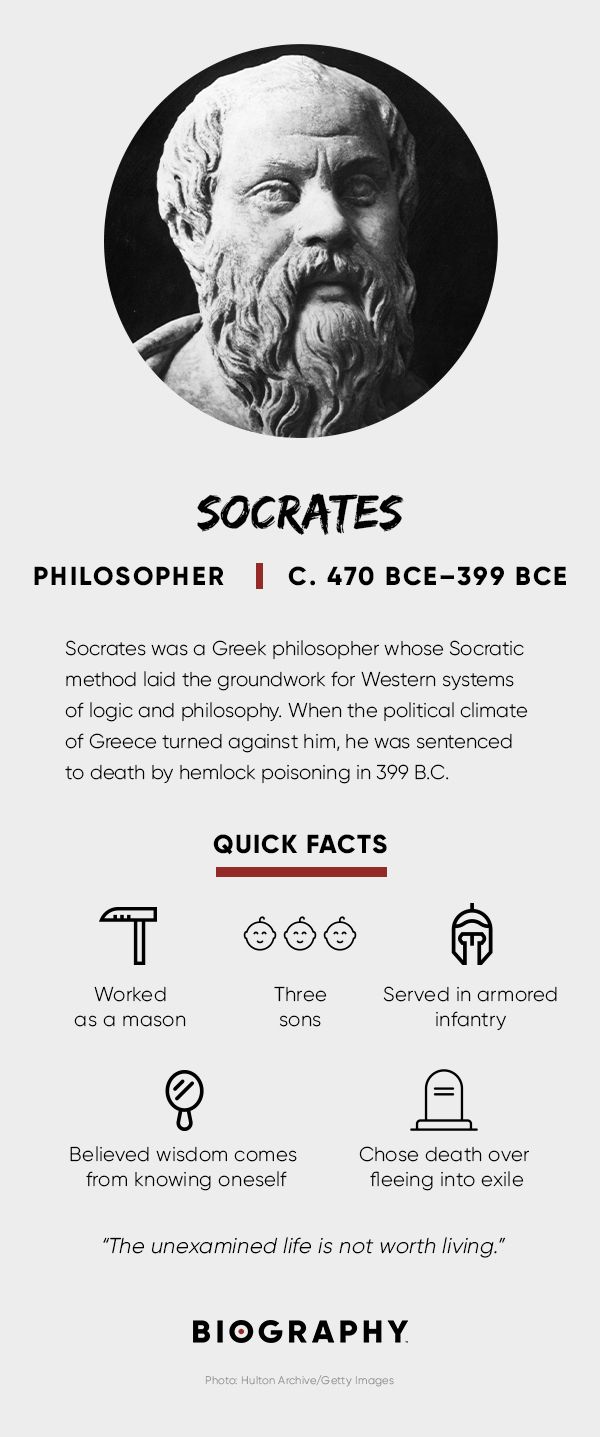

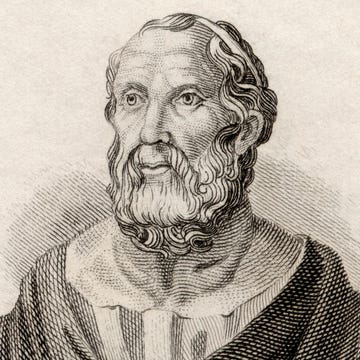

Socrates was an ancient Greek philosopher, one of the three greatest figures of the ancient period of Western philosophy (the others were Plato and Aristotle ), who lived in Athens in the 5th century BCE. A legendary figure even in his own time, he was admired by his followers for his integrity, his self-mastery, his profound philosophical insight, and his great argumentative skill. He was the first Greek philosopher to seriously explore questions of ethics . His influence on the subsequent course of ancient philosophy was so great that the cosmologically oriented philosophers who generally preceded him are conventionally referred to as the “ pre-Socratics .”

Socrates professed not to teach anything (and indeed not to know anything important) but only to seek answers to urgent human questions (e.g., “What is virtue?” and “What is justice?”) and to help others do the same. His style of philosophizing was to engage in public conversations about some human excellence and, through skillful questioning, to show that his interlocutors did not know what they were talking about. Despite the negative results of these encounters, Socrates did hold some broad positive views, including that virtue is a form of knowledge and that “care of the soul” (the cultivation of virtue) is the most important human obligation.

Socrates wrote nothing. All that is known about him has been inferred from accounts by members of his circle—primarily Plato and Xenophon —as well as by Plato’s student Aristotle , who acquired his knowledge of Socrates through his teacher. The most vivid portraits of Socrates exist in Plato’s dialogues, in most of which the principal speaker is “Socrates.” However, the views expressed by the character are not consistent across the dialogues, and in some dialogues the character expresses views that are clearly Plato’s own. Scholars continue to disagree about which of the dialogues convey the views of the historical Socrates and which use the character simply as a mouthpiece for Plato’s philosophy.

Socrates was widely hated in Athens, mainly because he regularly embarrassed people by making them appear ignorant and foolish. He was also an outspoken critic of democracy , which Athenians cherished, and he was associated with some members of the Thirty Tyrants , who briefly overthrew Athens’s democratic government in 404–403 BCE. He was arguably guilty of the crimes with which he was charged, impiety and corrupting the youth, because he did reject the city’s gods and he did inspire disrespect for authority among his youthful followers (though that was not his intention). He was accordingly convicted and sentenced to death by poison.

Socrates could have saved himself. He chose to go to trial rather than enter voluntary exile. In his defense speech, he rebutted some but not all elements of the charges and famously declared that "the unexamined life is not worth living." After being convicted, he could have proposed a reasonable penalty short of death but initially refused. He finally rejected an offer of escape as inconsistent with his commitment never to do wrong (escaping would show disrespect for the laws and harm the reputations of his family and friends).

Trusted Britannica articles, summarized using artificial intelligence, to provide a quicker and simpler reading experience. This is a beta feature. Please verify important information in our full article.

This summary was created from our Britannica article using AI. Please verify important information in our full article.

Socrates (born c. 470 bce , Athens [Greece]—died 399 bce , Athens) was an ancient Greek philosopher whose way of life, character, and thought exerted a profound influence on Classical antiquity and Western philosophy .

Socrates was a widely recognized and controversial figure in his native Athens, so much so that he was frequently mocked in the plays of comic dramatists. (The Clouds of Aristophanes , produced in 423, is the best-known example.) Although Socrates himself wrote nothing, he is depicted in conversation in compositions by a small circle of his admirers— Plato and Xenophon first among them. He is portrayed in these works as a man of great insight, integrity , self-mastery, and argumentative skill. The impact of his life was all the greater because of the way in which it ended: at age 70, he was brought to trial on a charge of impiety and sentenced to death by poisoning (the poison probably being hemlock ) by a jury of his fellow citizens. Plato’s Apology of Socrates purports to be the speech Socrates gave at his trial in response to the accusations made against him (Greek apologia means “defense”). Its powerful advocacy of the examined life and its condemnation of Athenian democracy have made it one of the central documents of Western thought and culture .

Philosophical and literary sources

While Socrates was alive, he was, as noted, the object of comic ridicule, but most of the plays that make reference to him are entirely lost or exist only in fragmentary form— Clouds being the chief exception. Although Socrates is the central figure of this play, it was not Aristophanes’ purpose to give a balanced and accurate portrait of him (comedy never aspires to this) but rather to use him to represent certain intellectual trends in contemporary Athens—the study of language and nature and, as Aristophanes implies, the amoralism and atheism that accompany these pursuits. The value of the play as a reliable source of knowledge about Socrates is thrown further into doubt by the fact that, in Plato’s Apology , Socrates himself rejects it as a fabrication. This aspect of the trial will be discussed more fully below.

Soon after Socrates’ death, several members of his circle preserved and praised his memory by writing works that represent him in his most characteristic activity—conversation. His interlocutors in these (typically adversarial) exchanges included people he happened to meet, devoted followers, prominent political figures, and leading thinkers of the day. Many of these “Socratic discourses,” as Aristotle calls them in his Poetics , are no longer extant; there are only brief remnants of the conversations written by Antisthenes , Aeschines , Phaedo , and Eucleides. But those composed by Plato and Xenophon survive in their entirety. What knowledge we have of Socrates must therefore depend primarily on one or the other (or both, when their portraits coincide) of these sources. (Plato and Xenophon also wrote separate accounts, each entitled Apology of Socrates , of Socrates’ trial.) Most scholars, however, do not believe that every Socratic discourse of Xenophon and Plato was intended as a historical report of what the real Socrates said, word-for-word, on some occasion. What can reasonably be claimed about at least some of these dialogues is that they convey the gist of the questions Socrates asked, the ways in which he typically responded to the answers he received, and the general philosophical orientation that emerged from these conversations.

Among the compositions of Xenophon , the one that gives the fullest portrait of Socrates is Memorabilia . The first two chapters of Book I of this work are especially important, because they explicitly undertake a refutation of the charges made against Socrates at his trial; they are therefore a valuable supplement to Xenophon’s Apology , which is devoted entirely to the same purpose. The portrait of Socrates that Xenophon gives in Books III and IV of Memorabilia seems, in certain passages, to be heavily influenced by his reading of some of Plato’s dialogues, and so the evidentiary value of at least this portion of the work is diminished. Xenophon’s Symposium is a depiction of Socrates in conversation with his friends at a drinking party (it is perhaps inspired by a work of Plato of the same name and character) and is regarded by some scholars as a valuable re-creation of Socrates’ thought and way of life. Xenophon’s Oeconomicus (literally: “estate manager”), a Socratic conversation concerning household organization and the skills needed by the independent farmer, is Xenophon’s attempt to bring the qualities he admired in Socrates to bear upon the subject of overseeing one’s property. It is unlikely to have been intended as a report of one of Socrates’ conversations.

Socrates of Athens (l. c. 470/469-399 BCE) is among the most famous figures in world history for his contributions to the development of ancient Greek philosophy which provided the foundation for all of Western Philosophy . He is, in fact, known as the "Father of Western Philosophy" for this reason.

He was originally a sculptor who seems to have also had a number of other occupations, including soldier, before he was told by the Oracle at Delphi that he was the wisest man in the world. In an effort to prove the oracle wrong, he embarked on a new career of questioning those who were said to be wise and, in doing so, proved the oracle correct: Socrates was the wisest man in the world because he did not claim to know anything of importance.

His most famous student was Plato (l. c. 424/423-348/347 BCE) who would honor his name through the establishment of a school in Athens (Plato's Academy) and, more so, through the philosophical dialogues he wrote featuring Socrates as the central character. Whether Plato's dialogues accurately represent Socrates' teachings continues to be debated but a definitive answer is unlikely to be reached. Plato's best known student was Aristotle of Stagira (l. 384-322 BCE) who would then tutor Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) and establish his own school. By this progression, Greek philosophy, as first developed by Socrates, was spread throughout the known world during, and after, Alexander 's conquests.

Socrates' historicity has never been challenged but what, precisely, he taught is as elusive as the philophical tenets of Pythagoras or the later teachings of Jesus in that none of these figures wrote anything themselves. Although Socrates is generally regarded as initiating the discipline of philosophy in the West, most of what we know of him comes from Plato and, less so, from another of his students, Xenophon (l. 430-c.354 BCE). There have also been efforts made to reconstruct his philosophic vision based on the many other schools, besides Plato's, which his students founded but these are too varied to define the original teachings which inspired them.

The "Socrates" who has come down to the present day from antiquity could largely be a philosophical construct of Plato and, according to the historian Diogenes Laertius (l. c. 180 - 240 CE), many of Plato's contemporaries accused him of re-imagining Socrates in his own image in order to further Plato's own interpretation of his master's message. However that may be, Socrates' influence would establish the schools which led to the formulation of Western Philosophy and the underlying cultural understanding of Western civilization .

Early Life and Career

Socrates was born c. 469/470 BCE to the sculptor Sophronicus and the mid-wife Phaenarete. He studied music , gymnastics, and grammar in his youth (the common subjects of study for a young Greek) and followed his father's profession as a sculptor. Tradition holds that he was an exceptional artist and his statue of the Graces , on the road to the Acropolis , is said to have been admired into the 2nd century CE. Socrates served with distinction in the army and, at the Battle of Potidaea, saved the life of the General Alcibiades .

He married Xanthippe, an upper-class woman, around the age of fifty and had three sons by her. According to contemporary writers such as Xenophon, these boys were incredibly dull and nothing like their father. Socrates seems to have lived a fairly normal life until he was told by the Oracle at Delphi that he was the wisest of men. His challenge to the oracle's claim set him the course that would establish him as a philosopher and the founder of Western Philosophy.

The Oracle and Socrates

When he was middle-aged, Socrates' friend Chaerephon asked the famous Oracle at Delphi if there was anyone wiser than Socrates, to which the Oracle answered, "None." Bewildered by this answer and hoping to prove the Oracle wrong, Socrates went about questioning people who were held to be 'wise' in their own estimation and that of others. He found, to his dismay, "that the men whose reputation for wisdom stood highest were nearly the most lacking in it, while others who were looked down on as common people were much more intelligent" (Plato, Apology , 22).

The youth of Athens delighted in watching Socrates question their elders in the market and, soon, he had a following of young men who, because of his example and his teachings, would go on to abandon their early aspirations and devote themselves to philosophy (from the Greek 'Philo', love, and 'Sophia', wisdom - literally 'the love of wisdom'). Among these were Antisthenes of Athens (l. c. 445-365 BCE), founder of the Cynic school, Aristippus of Cyrene (l. c. 435-356 BCE), founder of the Cyrenaic school), Xenophon, whose writings would influence Zeno of Citium , (l.c. 336-265 BCE) founder of the Stoic school, and, most famously, Plato (the main source of our information of Socrates in his Dialogues ) among many others. Every major philosophical school mentioned by ancient writers following Socrates' death was founded by one of his followers.

Socratic Schools

The diversity of these schools is testimony to Socrates' wide ranging influence and, more importantly, the diversity of interpretations of his teachings. The philosophical concepts taught by Antisthenes and Aristippus could not be more different, in that the former taught that the good life was only realized by self-control and self-abnegation, while the latter claimed a life of pleasure was the only path worth pursuing.

It has been said that Socrates' greatest contribution to philosophy was to move intellectual pursuits away from the focus on `physical science ' (as pursued by the so-called Pre-Socratic Philosophers such as Thales , Anaximander , Anaximenes , and others) and into the abstract realm of ethics and morality. No matter the diversity of the schools which claimed to carry on his teachings, they all emphasized some form of morality as their foundational tenet. That the `morality' espoused by one school was often condemned by another, again bears witness to the very different interpretations of Socrates' central message.

While scholars have traditionally relied upon Plato's Dialogues as a source of information on the historical Socrates, Plato's contemporaries claimed he used a character he called `Socrates' as a mouth-piece for his own philosophical views. Notable among these critics was, allegedly, Phaedo, a fellow student of Plato whose name is famous from one of Plato's most influential dialogues (and whose writings are now lost) and Xenophon, whose Memorablia presents a different view of Socrates than that presented by Plato.

Socrates and his Vision

However his teachings were interpreted, it seems clear that Socrates' main focus was on how to live a good and virtuous life. The claim atrributed to him by Plato that "an unexamined life is not worth living" ( Apology , 38b) seems historically accurate, in that it is clear he inspired his followers to think for themselves instead of following the dictates of society and the accepted superstitions concerning the gods and how one should behave.

While there are differences between Plato's and Xenophon's depictions of Socrates, both present a man who cared nothing for class distinctions or `proper behavior' and who spoke as easily with women , servants, and slaves as with those of the higher classes.

In ancient Athens, individual behavior was maintained by a concept known as `Eusebia' which is often translated into English as `piety' but more closely resembles `duty' or `loyalty to a course'. In refusing to conform to the social propieties proscribed by Eusebia, Socrates angered many of the more important men of the city who could, rightly, accuse him of breaking the law by violating these customs.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Socrates' Trial

In 399 BCE Socrates was charged with impiety by Meletus the poet, Anytus the tanner, and Lycon the orator who sought the death penalty in the case. The accusation read: “Socrates is guilty, firstly, of denying the gods recognized by the state and introducing new divinities, and, secondly, of corrupting the young.” It has been suggested that this charge was both personally and politically motivated as Athens was trying to purge itself of those associated with the scourge of the Thirty Tyrants of Athens who had only recently been overthrown.

Socrates' relationship to this regime was through his former student, Critias , who was considered the worst of the tyrants and was thought to have been corrupted by Socrates. It has also been suggested, based in part on interpretations of Plato's dialogue of the Meno , that Anytus blamed Socrates for corrupting his son. Anytus, it seems, had been grooming his son for a life in politics until the boy became interested in Socrates' teachings and abandoned political pursuits. As Socrates' accusers had Critias as an example of how the philosopher corrupted youth, even if they never used that evidence in court, the precedent appears to have been known to the jury.

The speechwriter usually presented the defendant as a good man who had been wronged by a false accusation, and this is the sort of defense the court would have expected from Socrates. Instead of the defense filled with self-justification and pleas for his life, however, Socrates defied the Athenian court, proclaiming his innocence and casting himself in the role of Athens' 'gadfly' - a benefactor to them all who, at his own expense, kept them awake and aware. In his Apology, Plato has Socrates say:

If you put me to death, you will not easily find another who, if I may use a ludicrous comparison, clings to the state as a sort of gadfly to a horse that is large and well-bred but rather sluggish because of its size, so that it needs to be aroused. It seems to me that the god has attached me like that to the state, for I am constantly alighting upon you at every point to arouse, persuade, and reporach each of you all day long. (Apology 30e)

Plato makes it clear in his work that the charges against Socrates hold little weight but also emphasizes Socrates' disregard for the feelings of the jury and court protocol. Socrates is presented as refusing professional counsel in the form of a speech-writer and, further, refusing to conform to the expected behavior of a defendant on trial for a capital crime. Socrates, according to Plato, had no fear of death, proclaiming to the court:

To fear death, my friends, is only to think ourselves wise without really being wise, for it is to think that we know what we do not know. For no one knows whether death may not be the greatest good tha can happen to man. But men fear it as if they knew quite well that it was the greatest of evils. (Apology 29a)

Following this passage, Plato gives Socrates' famous philosophical stand in which the old master defiantly states that he must choose service to the divine over conformity to his society and its expectations. Socrates famously confronts his fellow citizens with honesty, saying:

Men of Athens, I honor and love you; but I shall obey God rather than you and, while I have life and strength, I shall never cease from the practice and teaching of philosophy, exhorting anyone whom I meet after my manner, and convincing him saying: O my friend, why do you who are a citizen of the great and mighty and wise city of Athens care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honor and reputation and so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all? Are you not Ashamed of this? And if the person with whom I am arguing says: Yes, but I do care; I do not depart or let him go at once; I interrogate and examine and cross-examine him, and if I think that he has no virtue, but only says that he has, I reproach him with undervaluing the greater, and overvaluing the less. And this I should say to everyone whom I meet, young and old, citizen and alien, but especially to the citizens, inasmuch as they are my brethren. For this is the command of God, as I would have you know: and I believe that to this day no greater good has ever happened in the state than my service to the God. For I do nothing but go about persuading you all, old and young alike, not to take thought for your persons and your properties, but first and chiefly to care about the greatest improvement of the soul. I tell you that virtue is not given by money, but that from virtue come money and every other good of man, public as well as private. This is my teaching, and if this is the doctrine which corrupts the youth, my influence is ruinous indeed. But if anyone says that this is not my teaching, he is speaking an untruth. Wherefore, O men of Athens, I say to you, do as Anytus bids or not as Anytus bids, and either acquit me or not; but whatever you do, know that I shall never alter my ways, not even if I have to die many times. (29d-30c)

When it came time for Socrates to suggest a penalty to be imposed rather than death, he suggested he should be maintained in honor with free meals in the Prytaneum, a place reserved for heroes of the Olympic games . This would have been considered a serious insult to the honor of the Prytaneum and that of the city of Athens. Accused criminals on trial for their life were expected to beg for the mercy of the court, not presume to heroic accolades.

Conviction and Aftermath

Socrates was convicted and sentenced to death (Xenophon tells us that he wished for such an outcome and Plato's account of the trial in his Apology would seem to confirm this). The last days of Socrates are chronicled in Plato's Euthyphro, Apology, Crito and Phaedo , the last dialogue depicting the day of his death (by drinking hemlock) surrounded by his friends in his jail cell in Athens and, as Plato puts it, "Such was the end of our friend, a man, I think, who was the wisest and justest, and the best man I have ever known" ( Phaedo , 118). Socrates' influence was felt immediately in the actions of his disciples as they formed their own interpretations of his life, teachings, and death, and set about forming their own philosophical schools and writing about their experiences with their teacher. Of all these writings we have only the works of Plato, Xenophon, a comic image by Aristophanes , and later works by Aristotle to tell us anything about Socrates' life. He, himself, wrote nothing, but his words and actions in the search for and defense of Truth changed the world and his example still inspires people today.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Baird, F.E. Philosophic Classics, Volume I Ancient Philosophy. Pearson, 2010.

- Diogenes Laertius. The Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Harvard University Press, 2005.

- Freeman, K. Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers. Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Kaufmann, W. Philosophic Classics. Prentice Hall College Div, 2010.

- Plato. The Collected Dialogues of Plato. Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Robinson, J. M. An Introduction to Early Greek Philosophy. Houghton Mifflin School, 2000.

- Waterfield, R. The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and the Sophists. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Xenophon. Conversations of Socrates. Penguin Classics, 2000.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

Who was socrates, what is socrates best known for, what were the legal charges brought against socrates, why did socrates choose to die when he could have escaped, related content.

Aristippus of Cyrene

The Life of Aristippus in Diogenes Laertius

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Oxford University Press (2023) |

| , published by Routledge (2017) |

| , published by Penguin Classics (1990) |

| , published by Harvard University Press (1998) |

| , published by Princeton University Press (2005) |

External Links

Cite this work.

Mark, J. J. (2009, September 02). Socrates . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/socrates/

Chicago Style

Mark, Joshua J.. " Socrates ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified September 02, 2009. https://www.worldhistory.org/socrates/.

Mark, Joshua J.. " Socrates ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 02 Sep 2009. Web. 21 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Joshua J. Mark , published on 02 September 2009. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

6 (page 105) p. 105 Conclusion

- Published: October 2000

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

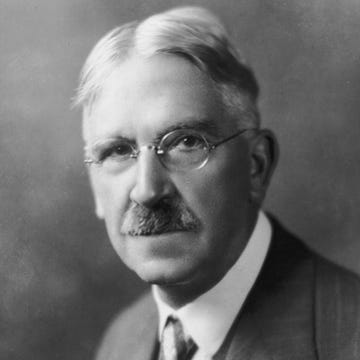

The Conclusion argues that the historical importance of Socrates, unquestionable though it is, does not exhaust his significance, even for a secular, non-ideological age. As well as a historical person and a literary persona, Socrates is an exemplary figure, who challenges, encourages, and inspires. The Socratic method of challenging students to examine their beliefs, to revise them in the light of argument, and to arrive at answers through critical reflection on the information presented goes far beyond pedagogical strategy. ‘The unexamined life is not worth living for a human being’ expresses a central human value: the willingness to rethink one's own assumptions, thereby rejecting the tendency to complacent dogmatism.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 13, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Viewed by many as the founding figure of Western philosophy, Socrates (469-399 B.C.) is at once the most exemplary and the strangest of the Greek philosophers. He grew up during the golden age of Pericles’ Athens, served with distinction as a soldier, but became best known as a questioner of everything and everyone. His style of teaching—immortalized as the Socratic method—involved not conveying knowledge, but rather asking question after clarifying question until his students arrived at their own understanding.

Socrates wrote nothing himself, so all that is known about him is filtered through the writings of a few contemporaries and followers, most notably his student Plato. Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth of Athens and sentenced to death. Choosing not to flee, he spent his final days in the company of his friends before drinking the executioner’s cup of poisonous hemlock.

Socrates: Early Years

Socrates was born and lived nearly his entire life in Athens. His father Sophroniscus was a stonemason and his mother, Phaenarete, was a midwife. As a youth, he showed an appetite for learning. Plato describes him eagerly acquiring the writings of the leading contemporary philosopher Anaxagoras and says he was taught rhetoric by Aspasia , the talented mistress of the great Athenian leader Pericles .

Did you know? Although he never outright rejected the standard Athenian view of religion, Socrates' beliefs were nonconformist. He often referred to God rather than the gods, and reported being guided by an inner divine voice .

His family apparently had the moderate wealth required to launch Socrates’ career as a hoplite (foot soldier). As an infantryman, Socrates showed great physical endurance and courage, rescuing the future Athenian leader Alcibiades during the siege of Potidaea in 432 B.C.

Through the 420s, Socrates was deployed for several battles in the Peloponnesian War , but also spent enough time in Athens to become known and beloved by the city’s youth. In 423 he was introduced to the broader public as a caricature in Aristophanes’ play “Clouds,” which depicted him as an unkempt buffoon whose philosophy amounted to teaching rhetorical tricks for getting out of debt.

Philosophy of Socrates

Although many of Aristophanes’ criticisms seem unfair, Socrates cut a strange figure in Athens, going about barefoot, long-haired and unwashed in a society with incredibly refined standards of beauty. It didn’t help that he was by all accounts physically ugly, with an upturned nose and bulging eyes.

Despite his intellect and connections, he rejected the sort of fame and power that Athenians were expected to strive for. His lifestyle—and eventually his death—embodied his spirit of questioning every assumption about virtue, wisdom and the good life.

Two of his younger students, the historian Xenophon and the philosopher Plato, recorded the most significant accounts of Socrates’ life and philosophy. For both, the Socrates that appears bears the mark of the writer. Thus, Xenophon’s Socrates is more straightforward, willing to offer advice rather than simply asking more questions. In Plato’s later works, Socrates speaks with what seem to be largely Plato’s ideas.

In the earliest of Plato’s “Dialogues”—considered by historians to be the most accurate portrayal—Socrates rarely reveals any opinions of his own as he brilliantly helps his interlocutors dissect their thoughts and motives in Socratic dialogue, a form of literature in which two or more characters (in this case, one of them Socrates) discuss moral and philosophical issues.

One of the greatest paradoxes that Socrates helped his students explore was whether weakness of will—doing wrong when you genuinely knew what was right—ever truly existed. He seemed to think otherwise: people only did wrong when at the moment the perceived benefits seemed to outweigh the costs. Thus the development of personal ethics is a matter of mastering what he called “the art of measurement,” correcting the distortions that skew one’s analyses of benefit and cost.

Socrates was also deeply interested in understanding the limits of human knowledge. When he was told that the Oracle at Delphi had declared that he was the wisest man in Athens, Socrates balked until he realized that, although he knew nothing, he was (unlike his fellow citizens) keenly aware of his own ignorance.

Trial and Death of Socrates

Socrates avoided political involvement where he could and counted friends on all sides of the fierce power struggles following the end of the Peloponnesian War. In 406 B.C. his name was drawn to serve in Athens’ assembly, or ekklesia, one of the three branches of ancient Greek democracy known as demokratia.

Socrates became the lone opponent of an illegal proposal to try a group of Athens’ top generals for failing to recover their dead from a battle against Sparta (the generals were executed once Socrates’ assembly service ended). Three years later, when a tyrannical Athenian government ordered Socrates to participate in the arrest and execution of Leon of Salamis, he refused—an act of civil disobedience that Martin Luther King Jr. would cite in his “ Letter from a Birmingham Jail .”

The tyrants were forced from power before they could punish Socrates, but in 399 he was indicted for failing to honor the Athenian gods and for corrupting the young. Although some historians suggest that there may have been political machinations behind the trial, he was condemned on the basis of his thought and teaching. In his “The Apology of Socrates,” Plato recounts him mounting a spirited defense of his virtue before the jury but calmly accepting their verdict. It was in court that Socrates allegedly uttered the now-famous phrase, “the unexamined life is not worth living.”

His execution was delayed for 30 days due to a religious festival, during which the philosopher’s distraught friends tried unsuccessfully to convince him to escape from Athens. On his last day, Plato says, he “appeared both happy in manner and words as he died nobly and without fear.” He drank the cup of brewed hemlock his executioner handed him, walked around until his legs grew numb and then lay down, surrounded by his friends, and waited for the poison to reach his heart.

The Socratic Legacy

Socrates is unique among the great philosophers in that he is portrayed and remembered as a quasi-saint or religious figure. Indeed, nearly every school of ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, from the Skeptics to the Stoics to the Cynics, desired to claim him as one of their own (only the Epicurians dismissed him, calling him “the Athenian buffoon”).

Since all that is known of his philosophy is based on the writing of others, the Socratic problem, or Socratic question–reconstructing the philosopher’s beliefs in full and exploring any contradictions in second-hand accounts of them–remains an open question facing scholars today.

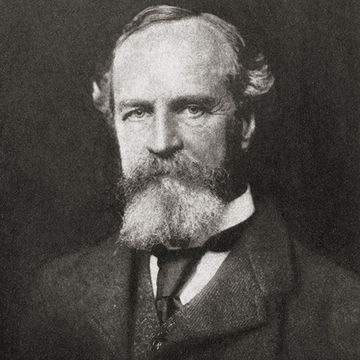

Socrates and his followers expanded the purpose of philosophy from trying to understand the outside world to trying to tease apart one’s inner values. His passion for definitions and hair-splitting questions inspired the development of formal logic and systematic ethics from the time of Aristotle through the Renaissance and into the modern era.

Moreover, Socrates’ life became an exemplar of the difficulty and the importance of living (and if necessary dying) according to one’s well-examined beliefs. In his 1791 autobiography Benjamin Franklin reduced this notion to a single line: “Humility: Imitate Jesus and Socrates.”

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Enable JavaScript and refresh the page to view the Center for Hellenic Studies website.

See how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Bibliographies

The ci poetry project, the last words of socrates at the place where he died.

2015.03.27 | By Gregory Nagy

§0. In H24H 24 §45, I quote and analyze the passage in Plato’s Phaedo 117a–118a where Socrates dies. His last words, as transmitted by Plato, are directed at all those who have followed Socrates—and who have had the unforgettable experience of engaging in dialogue with him. Calling out to one of those followers, Crito, who was a native son of the same neighborhood where Socrates was born, he says to his comrade: don’t forget to sacrifice a rooster to Asklepios . I will quote the whole passage in a minute. But first, we need to ask: who is this Asklepios? As I explain in H24H 20 §§29–33, he was a hero whose father was the god Apollo himself, and, like his divine father, Asklepios had special powers of healing. More than that, Asklepios also had the power of bringing the dead back to life. That is why he was killed by the immortals, since mortals must stay mortal. But Asklepios, even after death, retained his power to bring the dead back to life.

§1. So, what does Socrates mean when he asks his followers, in his dying words, not to forget to sacrifice a rooster to Asklepios?

§2. On 16 March 2015, the group participating in the 2015 Harvard Spring Break travel study program visited the site where Socrates died—and where he said what he said about sacrificing a rooster to Asklepios. On the surface, this site is nothing much to write home about. All we can see at the site is the foundation stones of the State Prison where Socrates was held prisoner and where he was forced to drink the hemlock in the year 399 BCE. But I feel deeply that, just by visiting the site, our group managed to connect with a sublime experience. We were making contact with a place linked forever with the very last words of one of the greatest thinkers in world history.

§3. I now quote my own translation of Plato’s Phaedo 117a–118a, which situates these last words of Socrates:

“Go,” said he [= Socrates], “and do as I say.” Crito, when he heard this, signaled with a nod to the boy servant who was standing nearby, and the servant went in, remaining for some time, and then came out with the man who was going to administer the poison [ pharmakon ]. He was carrying a cup that contained it, ground into the drink. When Socrates saw the man he said: “You, my good man, since you are experienced in these matters, should tell me what needs to be done.” The man answered: “You need to drink it, that’s all. Then walk around until you feel a heaviness | 117b in your legs. Then lie down. This way, the poison will do its thing.” While the man was saying this, he handed the cup to Socrates. And Socrates took it in a cheerful way, not flinching or getting pale or grimacing. Then looking at the man from beneath his brows, like a bull—that was the way he used to look at people—he said: “What do you say about my pouring a libation out of this cup to someone? Is it allowed or not?” The man answered: “What we grind is measured out, Socrates, as the right dose for drinking.” “I understand,” he said, | 117c “but surely it is allowed and even proper to pray to the gods so that my transfer of dwelling [ met-oikēsis ] from this world [ enthende ] to that world [ ekeîse ] should be fortunate. So, that is what I too am now praying for. Let it be this way.” And, while he was saying this, he took the cup to his lips and, quite readily and cheerfully, he drank down the whole dose. Up to this point, most of us had been able to control fairly well our urge to let our tears flow; but now when we saw him drinking the poison, and then saw him finish the drink, we could no longer hold back, and, in my case, quite against my own will, my own tears were now pouring out in a flood. So, I covered my face and had a good cry. You see, I was not crying for him, | 117d but at the thought of my own bad fortune in having lost such a comrade [ hetairos ]. Crito, even before me, found himself unable to hold back his tears: so he got up and moved away. And Apollodorus, who had been weeping all along, now started to cry in a loud voice, expressing his frustration. So, he made everyone else break down and cry—except for Socrates himself. And he said: “What are you all doing? I am so surprised at you. I had sent away the women mainly because I did not want them | 117e to lose control in this way. You see, I have heard that a man should come to his end [ teleutân ] in a way that calls for measured speaking [ euphēmeîn ]. So, you must have composure [ hēsukhiā ], and you must endure.” When we heard that, we were ashamed, and held back our tears. He meanwhile was walking around until, as he said, his legs began to get heavy, and then he lay on his back—that is what the man had told him to do. Then that same man who had given him the poison [ pharmakon ] took hold of him, now and then checking on his feet and legs; and after a while he pressed his foot hard and asked him if he could feel it; and he said that he couldn’t; and then he pressed his shins, | 118a and so on, moving further up, thus demonstrating for us that he was cold and stiff. Then he [= Socrates] took hold of his own feet and legs, saying that when the poison reaches his heart, then he will be gone. He was beginning to get cold around the abdomen. Then he uncovered his face, for he had covered himself up, and said— this was the last thing he uttered— “Crito, I owe the sacrifice of a rooster to Asklepios; will you pay that debt and not neglect to do so?” “I will make it so,” said Crito, “and, tell me, is there anything else?” When Crito asked this question, no answer came back anymore from Socrates. In a short while, he stirred. Then the man uncovered his face. His eyes were set in a dead stare. Seeing this, Crito closed his mouth and his eyes. Such was the end [ teleutē ], Echecrates, of our comrade [ hetairos ]. And we may say about him that he was in his time the best [ aristos ] of all men we ever encountered—and the most intelligent [ phronimos ] and most just [ dikaios ].

So I come back to my question about the meaning of the last words of Socrates, when he says, in his dying words: don’t forget to sacrifice a rooster to Asklepios . As I begin to formulate an answer, I must repeat something that I have already highlighted. It is the fact that the hero Asklepios was believed to have special powers of healing—even the power of bringing the dead back to life. As I point out in H24H 24§46, some interpret the final instruction of Socrates to mean simply that death is a cure for life. I disagree. After sacrificing a rooster at day’s end, sacrificers will sleep the sleep of incubation and then, the morning after the sacrifice, they will wake up to hear other roosters crowing. So, the words of Socrates here are referring to rituals of overnight incubation in the hero cults of Asklepios.

§4. On 18 March 2015, the group participating in the 2015 Harvard Spring Break travel study program visited a site where such rituals of overnight incubation actually took place: the site was Epidaurus. This small city was famous for its hero cult of Asklepios. The space that was sacred to Asklepios, as our group had a chance to witness, is enormous, and the enormity is a sure sign of the intense veneration received by Asklepios as the hero who, even though he is dead, has the superhuman power to rescue you from death. The mystical logic of worshipping the dead Asklepios is that he died for humanity: he died because he had the power to bring humans back to life.

§5. So, Asklepios is the model for keeping the voice of the rooster alive. And, for Socrates, Asklepios can become the model for keeping the word alive.

§6. In H24H 24§47, I follow through on analyzing this idea of keeping the word from dying, of keeping the word alive. That living word, I argue, is dialogue. We can see it when Socrates says that the only thing worth crying about is the death of the word. I am about to quote another passage from Plato’s Phaedo , and again I will use my own translation. But before I quote the passage, here is the context: well before Socrates is forced to drink the hemlock, his followers are already mourning his impending death, and Socrates reacts to their sadness by telling them that the only thing that would be worth mourning is not his death but the death of the conversation he started with them. Calling out to one of his followers, Phaedo, Socrates tells him (Plato, Phaedo 89b):

“Tomorrow, Phaedo, you will perhaps be cutting off these beautiful locks of yours [as a sign of mourning]?” “Yes, Socrates,” I [= Phaedo] replied, “I guess I will.” He shot back: “No you will not, if you listen to me.” “So, what will I do?” I [= Phaedo] said. He replied: “Not tomorrow but today I will cut off my own hair and you too will cut off these locks of yours—if our argument [ logos ] comes to an end [ teleutân ] for us and we cannot bring it back to life again [ ana-biōsasthai ].

What matters for Socrates, as I argue in H24H 24§48, is the resurrection of the ‘argument’ or logos , which means literally ‘word’, even if death may be the necessary pharmakon or ‘poison’ for leaving the everyday life and for entering the everlasting cycle of resurrecting the word.

§7. In the 2015 book Masterpieces of Metonymy (MoM), published both online and in print , I study in Part One a traditional custom that prevailed in Plato’s Academy at Athens for centuries after the death of Socrates. Their custom was to celebrate the birthday of Socrates on the sixth day of the month Thargelion, which by their reckoning coincided with his death day. And they celebrated by engaging in Socratic dialogue, which for them was the logos that was resurrected every time people engage in Socratic dialogue. I go on to say in MoM 1 §§146–147:

For Plato and for Plato’s Socrates, the word logos refers to the living ‘word’ of dialogue in the context of philosophical argumentation. When Socrates in Plato’s Phaedo (89b) tells his followers who are mourning his impending death that they should worry not about his death but about the death of the logos— if this logos cannot be resurrected or ‘brought back to life’ ( ana-biōsasthai )—he is speaking of the dialogic argumentation supporting the idea that the psūkhē or ‘soul’ is immortal. In this context, the logos itself is the ‘argument’.

For Plato’s Socrates, it is less important that his psūkhē or ‘soul’ must be immortal, and it is vitally more important that the logos itself must remain immortal—or, at least, that the logos must be brought back to life. And that is because the logos itself, as I say, is the ‘argument’ that comes to life in dialogic argumentation.

Here is the way I would sum up, then, what Socrates means as he speaks his last words. When the sun goes down and you check in for sacred incubation at the precinct of Asklepios, you sacrifice a rooster to this hero who, even in death, has the power to bring you back to life. As you drift off to sleep at the place of incubation, the voice of that rooster is no longer heard. He is dead, and you are asleep. But then, as the sun comes up, you wake up to the voice of a new rooster signaling that morning is here, and this voice will be for you a sign that says: the word that died has come back to life again. Asklepios has once again shown his sacred power. The word is resurrected. The conversation may now continue.

Continue Reading

Reverse orpheus, reverse eurydice, by rowan ricardo phillips, the song of nikaia, by rachel hadas, thoughts on classical studies in the 21st century united states.

Socrates was an ancient Greek philosopher considered to be the main source of Western thought. He was condemned to death for his Socratic method of questioning.

Who Was Socrates?

When the political climate of Greece turned against him, Socrates was sentenced to death by hemlock poisoning in 399 B.C. He accepted this judgment rather than fleeing into exile.

Early Years

Born circa 470 B.C. in Athens, Greece, Socrates's life is chronicled through only a few sources: the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon and the plays of Aristophanes.

Because these writings had other purposes than reporting his life, it is likely none present a completely accurate picture. However, collectively, they provide a unique and vivid portrayal of Socrates's philosophy and personality.

Socrates was the son of Sophroniscus, an Athenian stonemason and sculptor, and Phaenarete, a midwife. Because he wasn't from a noble family, he probably received a basic Greek education and learned his father's craft at a young age. It's believed Socrates worked as mason for many years before he devoted his life to philosophy.