Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

IV. Types of Argumentation

4.3 Basic Structure and Content of Argument

Amanda Lloyd; Emilie Zickel; Robin Jeffrey; and Terri Pantuso

When you are tasked with crafting an argumentative essay, it is likely that you will be expected to craft your argument based upon a given number of sources–all of which should support your topic in some way. Your instructor might provide these sources for you, ask you to locate these sources, or provide you with some sources and ask you to find others. Whether or not you are asked to do additional research, an argumentative essay should contain the following basic components.

Claim: What Do You Want the Reader to Believe?

In an argument paper, the thesis is often called a claim . This claim is a statement in which you take a stand on a debatable issue. A strong, debatable claim has at least one valid counterargument, an opposite or alternative point of view that is as sensible as the position that you take in your claim. In your thesis statement, you should clearly and specifically state the position you will convince your audience to adopt. One way to accomplish this is via either a closed or open thesis statement.

A closed thesis statement includes sub-claims or reasons why you choose to support your claim.

Example of Closed Thesis Statement

The city of Houston has displayed a commitment to attracting new residents by making improvements to its walkability, city centers, and green spaces.

In this instance, walkability, city centers, and green spaces are the sub-claims, or reasons, why you would make the claim that Houston is attracting new residents.

An open thesis statement does not include sub-claims and might be more appropriate when your argument is less easy to prove with two or three easily-defined sub-claims.

Example of Open Thesis Statement

The city of Houston is a vibrant metropolis due to its walkability, city centers, and green spaces.

The choice between an open or a closed thesis statement often depends upon the complexity of your argument. Another possible construction would be to start with a research question and see where your sources take you.

A research question approach might ask a large question that will be narrowed down with further investigation.

Example of Research Question Approach

What has the city of Houston done to attract new residents and/or make the city more accessible?

As you research the question, you may find that your original premise is invalid or incomplete. The advantage to starting with a research question is that it allows for your writing to develop more organically according to the latest research. When in doubt about how to structure your thesis statement, seek the advice of your instructor or a writing center consultant.

A Note on Context: What Background Information About the Topic Does Your Audience Need?

Before you get into defending your claim, you will need to place your topic (and argument) into context by including relevant background material. Remember, your audience is relying on you for vital information such as definitions, historical placement, and controversial positions. This background material might appear in either your introductory paragraph(s) or your body paragraphs. How and where to incorporate background material depends a lot upon your topic, assignment, evidence, and audience. In most cases, kairos, or an opportune moment, factors heavily in the ways in which your argument may be received.

Evidence or Grounds: What Makes Your Reasoning Valid?

To validate the thinking that you put forward in your claim and sub-claims, you need to demonstrate that your reasoning is based on more than just your personal opinion. Evidence, sometimes referred to as grounds, can take the form of research studies or scholarship, expert opinions, personal examples, observations made by yourself or others, or specific instances that make your reasoning seem sound and believable. Evidence only works if it directly supports your reasoning — and sometimes you must explain how the evidence supports your reasoning (do not assume that a reader can see the connection between evidence and reason that you see).

Warrants: Why Should a Reader Accept Your Claim?

A warrant is the rationale the writer provides to show that the evidence properly supports the claim with each element working towards a similar goal. Think of warrants as the glue that holds an argument together and ensures that all pieces work together coherently.

An important way to ensure you are properly supplying warrants within your argument is to use topic sentences for each paragraph and linking sentences within that connect the particular claim directly back to the thesis. Ensuring that there are linking sentences in each paragraph will help to create consistency within your essay. Remember, the thesis statement is the driving force of organization in your essay, so each paragraph needs to have a specific purpose (topic sentence) in proving or explaining your thesis. Linking sentences complete this task within the body of each paragraph and create cohesion. These linking sentences will often appear after your textual evidence in a paragraph.

Counterargument: But What About Other Perspectives?

Later in this section, we have included an essay by Steven Krause who offers a thorough explanation of what counterargument is (and how to respond to it). In summary, a strong arguer should not be afraid to consider perspectives that either challenge or completely oppose his or her own claim. When you respectfully and thoroughly discuss perspectives or research that counters your own claim or even weaknesses in your own argument, you are showing yourself to be an ethical arguer. The following are some things of which counter arguments may consist:

- summarizing opposing views;

- explaining how and where you actually agree with some opposing views;

- acknowledging weaknesses or holes in your own argument.

You have to be careful and clear that you are not conveying to a reader that you are rejecting your own claim. It is important to indicate that you are merely open to considering alternative viewpoints. Being open in this way shows that you are an ethical arguer – you are considering many viewpoints.

Types of Counterarguments

Counterarguments can take various forms and serve a range of purposes such as:

- Could someone disagree with your claim? If so, why? Explain this opposing perspective in your own argument, and then respond to it.

- Could someone draw a different conclusion from any of the facts or examples you present? If so, what is that different conclusion? Explain this different conclusion and then respond to it.

- Could a reader question any of your assumptions or claims? If so, which ones would they question? Explain and then respond.

- Could a reader offer a different explanation of an issue? If so, what might their explanation be? Describe this different explanation, and then respond to it.

- Is there any evidence out there that could weaken your position? If so, what is it? Cite and discuss this evidence and then respond to it.

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, that does not necessarily mean that you have a weak argument. It means ideally, and as long as your argument is logical and valid, that you have a counterargument. Good arguments can and do have counterarguments; it is important to discuss them. But you must also discuss and then respond to those counterarguments.

Response to Counterargument: I See That, But…

Just as it is important to include counterargument to show that you are fair-minded and balanced, you must respond to the counterargument so that a reader clearly sees that you are not agreeing with the counterargument and thus abandoning or somehow undermining your own claim. Failure to include the response to counterargument can confuse the reader. There are several ways to respond to a counterargument such as:

- Concede to a specific point or idea from the counterargument by explaining why that point or idea has validity. However, you must then be sure to return to your own claim, and explain why even that concession does not lead you to completely accept or support the counterargument;

- Reject the counterargument if you find it to be incorrect, fallacious, or otherwise invalid;

- Explain why the counterargument perspective does not invalidate your own claim.

A Note About Where to Put the Counterargument

It is certainly possible to begin the argument section (after the background section) with your counterargument + response instead of placing it at the end of your essay. Some people prefer to have their counterargument first where they can address it and then spend the rest of their essay building their own case and supporting their own claim. However, it is just as valid to have the counterargument + response appear at the end of the paper after you have discussed all of your reasons.

What is important to remember is that wherever you place your counterargument, you should:

- Explain what the counter perspectives are;

- Describe them thoroughly;

- Cite authors who have these counter perspectives;

- Quote them and summarize their thinking.

- Make it clear to the reader of your argument why you concede to certain points of the counterargument or why you reject them;

- Make it clear that you do not accept the counterargument, even though you understand it;

- Be sure to use transitional phrases that make this clear to your reader.

Responding to Counterarguments

You do not need to attempt to do all of these things as a way to respond. Instead, choose the response strategy that makes the most sense to you for the counterargument that you find:

- “However, this information does not apply to our topic because…”

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains different evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the evidence that the counterarguer presents;

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains a different interpretation of evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the interpretation of the evidence that your opponent (counterarguer) presents.

If the counterargument is an acknowledgement of evidence that threatens to weaken your argument, you must explain why and how that evidence does not, in fact, invalidate your claim.

It is important to use transitional phrases in your paper to alert readers when you’re about to present a counterargument. It’s usually best to put this phrase at the beginning of a paragraph such as:

- Researchers have challenged these claims with…

- Critics argue that this view…

- Some readers may point to…

- A perspective that challenges the idea that…

Transitional phrases will again be useful to highlight your shift from counterargument to response:

- Indeed, some of those points are valid. However, . . .

- While I agree that . . . , it is more important to consider . . .

- These are all compelling points. Still, other information suggests that . .

- While I understand . . . , I cannot accept the evidence because . . . [1]

In the section that follows, the Toulmin method of argumentation is described and further clarifies the terms discussed in this section.

This section contains material from:

Amanda Lloyd and Emilie Zickel. “Basic Structure of Arguments.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing , by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/basic-argument-components/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Jeffrey, Robin. “Counterargument and Response.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing , by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/questions-for-thinking-about-counterarguments/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

OER credited the texts above includes:

Jeffrey, Robin. About Writing: A Guide . Portland, OR: Open Oregon Educational Resources. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- This section originally contained the following attribution: This page contains material from “About Writing: A Guide” by Robin Jeffrey, OpenOregon Educational Resources, Higher Education Coordination Commission: Office of Community Colleges and Workforce Development is licensed under CC BY 4.0. ↵

An arguable statement; a point that a writer, researcher, or speaker makes in order to prove their thesis.

The basic assumptions or understanding on which an argument is based or from which conclusions are drawn. A major premise is a statement of universal truth or common knowledge. A minor premise is a statement related to a major premise but concerns a specific situation.

The explanation, justification, or motivation for something; the reasons why something was done.

4.3 Basic Structure and Content of Argument Copyright © 2022 by Amanda Lloyd; Emilie Zickel; Robin Jeffrey; and Terri Pantuso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

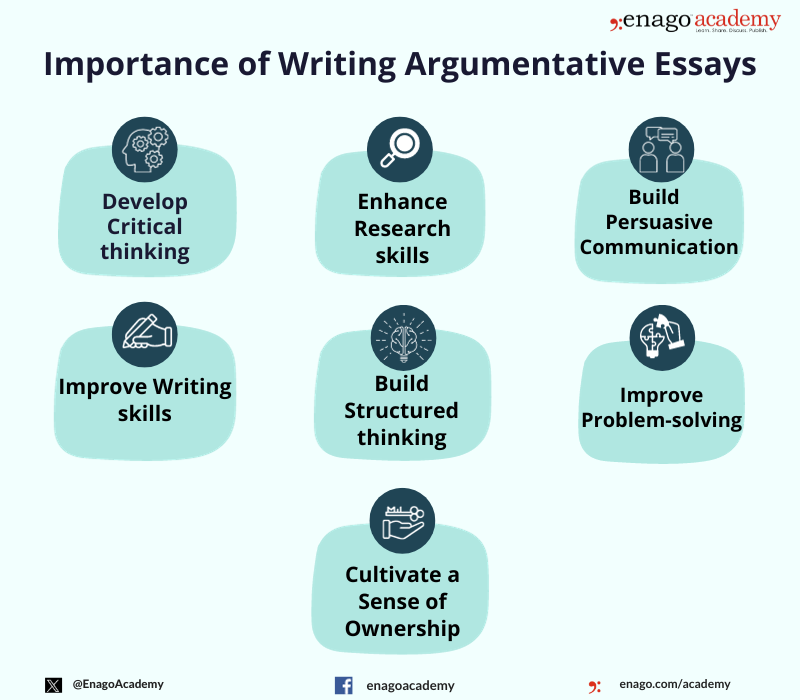

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

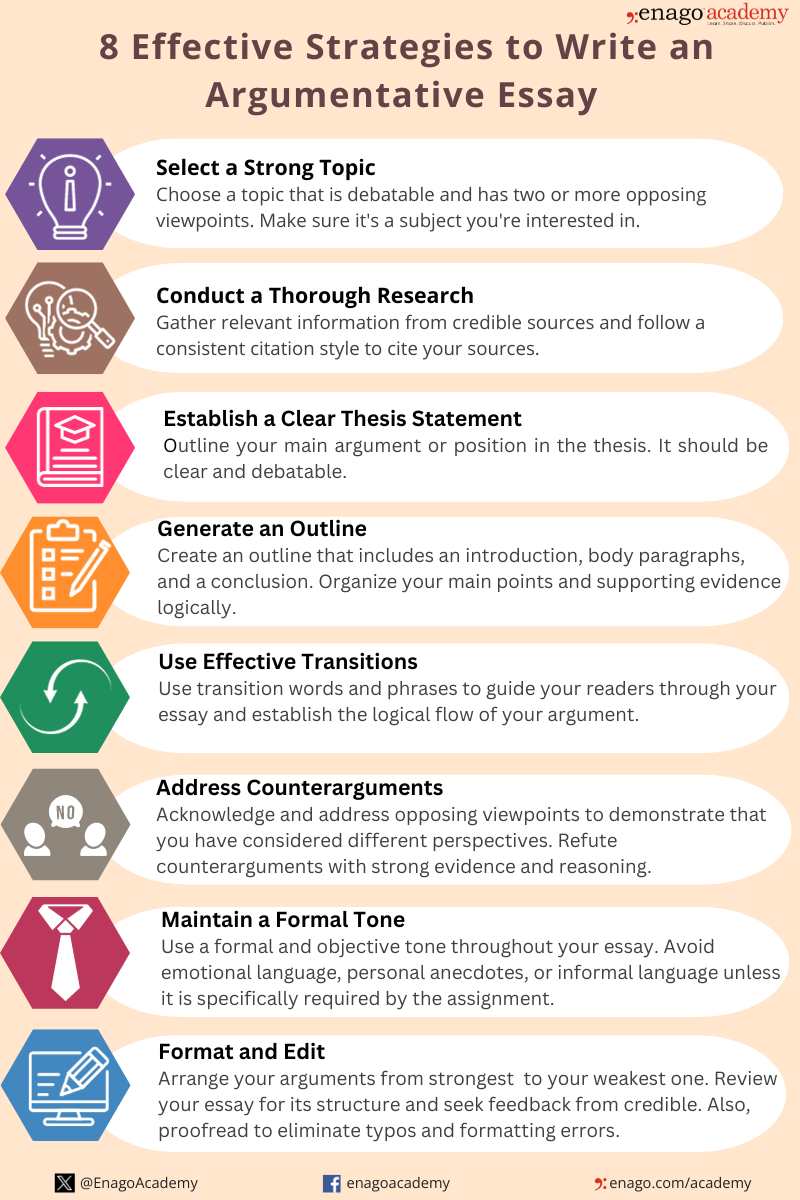

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

The pressure to “publish or perish” is a well-known reality for academics, striking fear into…

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Using AI for Journal Selection — Simplifying your academic publishing journey in the smart way

Strategic journal selection plays a pivotal role in maximizing the impact of one’s scholarly work.…

- Career Corner

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without…

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Argumentative Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is an argumentative essay?

The argumentative essay is a genre of writing that requires the student to investigate a topic; collect, generate, and evaluate evidence; and establish a position on the topic in a concise manner.

Please note : Some confusion may occur between the argumentative essay and the expository essay. These two genres are similar, but the argumentative essay differs from the expository essay in the amount of pre-writing (invention) and research involved. The argumentative essay is commonly assigned as a capstone or final project in first year writing or advanced composition courses and involves lengthy, detailed research. Expository essays involve less research and are shorter in length. Expository essays are often used for in-class writing exercises or tests, such as the GED or GRE.

Argumentative essay assignments generally call for extensive research of literature or previously published material. Argumentative assignments may also require empirical research where the student collects data through interviews, surveys, observations, or experiments. Detailed research allows the student to learn about the topic and to understand different points of view regarding the topic so that she/he may choose a position and support it with the evidence collected during research. Regardless of the amount or type of research involved, argumentative essays must establish a clear thesis and follow sound reasoning.

The structure of the argumentative essay is held together by the following.

- A clear, concise, and defined thesis statement that occurs in the first paragraph of the essay.

In the first paragraph of an argument essay, students should set the context by reviewing the topic in a general way. Next the author should explain why the topic is important ( exigence ) or why readers should care about the issue. Lastly, students should present the thesis statement. It is essential that this thesis statement be appropriately narrowed to follow the guidelines set forth in the assignment. If the student does not master this portion of the essay, it will be quite difficult to compose an effective or persuasive essay.

- Clear and logical transitions between the introduction, body, and conclusion.

Transitions are the mortar that holds the foundation of the essay together. Without logical progression of thought, the reader is unable to follow the essay’s argument, and the structure will collapse. Transitions should wrap up the idea from the previous section and introduce the idea that is to follow in the next section.

- Body paragraphs that include evidential support.

Each paragraph should be limited to the discussion of one general idea. This will allow for clarity and direction throughout the essay. In addition, such conciseness creates an ease of readability for one’s audience. It is important to note that each paragraph in the body of the essay must have some logical connection to the thesis statement in the opening paragraph. Some paragraphs will directly support the thesis statement with evidence collected during research. It is also important to explain how and why the evidence supports the thesis ( warrant ).

However, argumentative essays should also consider and explain differing points of view regarding the topic. Depending on the length of the assignment, students should dedicate one or two paragraphs of an argumentative essay to discussing conflicting opinions on the topic. Rather than explaining how these differing opinions are wrong outright, students should note how opinions that do not align with their thesis might not be well informed or how they might be out of date.

- Evidential support (whether factual, logical, statistical, or anecdotal).

The argumentative essay requires well-researched, accurate, detailed, and current information to support the thesis statement and consider other points of view. Some factual, logical, statistical, or anecdotal evidence should support the thesis. However, students must consider multiple points of view when collecting evidence. As noted in the paragraph above, a successful and well-rounded argumentative essay will also discuss opinions not aligning with the thesis. It is unethical to exclude evidence that may not support the thesis. It is not the student’s job to point out how other positions are wrong outright, but rather to explain how other positions may not be well informed or up to date on the topic.

- A conclusion that does not simply restate the thesis, but readdresses it in light of the evidence provided.

It is at this point of the essay that students may begin to struggle. This is the portion of the essay that will leave the most immediate impression on the mind of the reader. Therefore, it must be effective and logical. Do not introduce any new information into the conclusion; rather, synthesize the information presented in the body of the essay. Restate why the topic is important, review the main points, and review your thesis. You may also want to include a short discussion of more research that should be completed in light of your work.

A complete argument

Perhaps it is helpful to think of an essay in terms of a conversation or debate with a classmate. If I were to discuss the cause of World War II and its current effect on those who lived through the tumultuous time, there would be a beginning, middle, and end to the conversation. In fact, if I were to end the argument in the middle of my second point, questions would arise concerning the current effects on those who lived through the conflict. Therefore, the argumentative essay must be complete, and logically so, leaving no doubt as to its intent or argument.

The five-paragraph essay

A common method for writing an argumentative essay is the five-paragraph approach. This is, however, by no means the only formula for writing such essays. If it sounds straightforward, that is because it is; in fact, the method consists of (a) an introductory paragraph (b) three evidentiary body paragraphs that may include discussion of opposing views and (c) a conclusion.

Longer argumentative essays

Complex issues and detailed research call for complex and detailed essays. Argumentative essays discussing a number of research sources or empirical research will most certainly be longer than five paragraphs. Authors may have to discuss the context surrounding the topic, sources of information and their credibility, as well as a number of different opinions on the issue before concluding the essay. Many of these factors will be determined by the assignment.

Search form

A for and against essay.

Look at the essay and do the exercises to improve your writing skills.

Instructions

Do the preparation exercise first. Then do the other exercises.

Preparation

Check your understanding: multiple selection

Check your writing: reordering - essay structure, check your writing: typing - linking words, worksheets and downloads.

What are your views on reality TV? Are these types of shows popular in your country?

Sign up to our newsletter for LearnEnglish Teens

We will process your data to send you our newsletter and updates based on your consent. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the "unsubscribe" link at the bottom of every email. Read our privacy policy for more information.

Module 6: The Writing Process

Common essay structures, learning objectives.

- Examine the structure and organization of common types of essays

Suggested Essay Structure

What are we talking about when we talk about essay structures ? Depending on the assignment, you will need to utilize different ways to organize your essays. Some common layouts for essay organization are listed below, and if you are ever confused on which structure you should use for your assignment, ask your teacher for help.

Argumentative Essay

In an argumentative essay, you are asked to take a stance about an issue. One effective way to argue a point can be to present the opposing view first, usually in your introduction paragraph, then counter this view with stronger evidence in your essay. You can also explain your argument and claims, then address the opposing view at the end of your paper, or you could address opposing views one at a time, including the rebuttal throughout your paper.

Argumentative Essay: Block Format

- provides background information on topic

- states of your position on the topic (thesis)

- summarizes arguments

- Topic sentence outlining first claim

- Sentences giving explanations and providing evidence to support topic sentence

- Concluding sentence – link to next paragraph

- Topic sentence outlining second claim

- Sentences giving explanations and providing evidence to back topic sentence

- Topic sentence outlining any possible counterarguments

- Provide evidence to refute counterarguments

- Summary of the main points of the body

- Restatement of the position

Argumentative Essay: Rebuttal Throughout

This type of format works well for topics that have obvious pros and cons.

- Introduction and Thesis

- Topic sentence outlining first rebuttal

- Opposing Viewpoint

- Statistics and facts to support your side

- Summary of the main arguments and counterarguments

The Comparative Essay

Comparative essays compare , compare and contrast , or differentiate between things and concepts. In this structure, the similarities and/or differences between two or more items (for example, theories or models) are discussed paragraph by paragraph. Your assignment task may require you to make a recommendation about the suitability of the items you are comparing.

There are two basic formats for the compare/contrast essay: block or point-by-point. Block divides the essay in half with the first set of paragraphs covering one item, the other set of paragraphs covering the other item. Let’s take a look at an example about cameras. If the writer is contrasting a Nikon DSLR camera with a similar priced Canon DSLR camera, the first set of paragraphs would cover Nikon and the next set would cover Canon. In point-by-point, the writer would cover the two items alternating in each point of comparison (see examples in outlines below).

Comparative Essay: Block Method

- Introduction and thesis

- Image Quality

- Shutter Speed

- The Auto-focus System

Comparative Essay: Point-by-Point Method

- Introduction

- Nikon D7000

Cause and Effect Essay

Examples of cause and effect essays include questions that ask you to state or investigate the effects or outline the causes of the topic. This may be, for example, a historical event, the implementation of a policy, a medical condition, or a natural disaster. These essays may be structured in one of two ways: either the causes(s) of a situation may be discussed first followed by the effect(s), or the effect(s) could come first with the discussion working back to outline the cause(s). Sometimes with cause and effect essays, you are required to give an assessment of the overall effects of an event on a community, a workplace, an individual.

Cause and Effect Essay Format

- Background information on the situation under discussion

- Description of the situation

- Overview of the causes or effects to be outlined

- Topic sentence outlining first cause or effect

- Sentences giving explanations and providing evidence to support the topic sentence

- Concluding sentence – linking to the next paragraph

- Topic sentence outlining second cause or effect

- These follow the same structure for as many causes or effects as you need to outline

- Conclusion, prediction or recommendation

Mixed Structure Assignment

Finally, consider that some essay assignments may ask you to combine approaches. You will rarely follow the above outlines with exactness, but can use the outlines and templates of common rhetorical patterns to help shape your essay. Remember that the ultimate goal is to construct a smooth and coherent message with information that flows nicely from one paragraph to the next.

There are several different styles to choose from when constructing a mixed-structure essay. The table below gives an idea of what different roles paragraphs can play in a mixed-structure essay assignment.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.3 Organizing Your Writing

Learning objectives.

- Understand how and why organizational techniques help writers and readers stay focused.

- Assess how and when to use chronological order to organize an essay.

- Recognize how and when to use order of importance to organize an essay.

- Determine how and when to use spatial order to organize an essay.

The method of organization you choose for your essay is just as important as its content. Without a clear organizational pattern, your reader could become confused and lose interest. The way you structure your essay helps your readers draw connections between the body and the thesis, and the structure also keeps you focused as you plan and write the essay. Choosing your organizational pattern before you outline ensures that each body paragraph works to support and develop your thesis.

This section covers three ways to organize body paragraphs:

- Chronological order

- Order of importance

- Spatial order

When you begin to draft your essay, your ideas may seem to flow from your mind in a seemingly random manner. Your readers, who bring to the table different backgrounds, viewpoints, and ideas, need you to clearly organize these ideas in order to help process and accept them.

A solid organizational pattern gives your ideas a path that you can follow as you develop your draft. Knowing how you will organize your paragraphs allows you to better express and analyze your thoughts. Planning the structure of your essay before you choose supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and targeted research.

Chronological Order

In Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , you learned that chronological arrangement has the following purposes:

- To explain the history of an event or a topic

- To tell a story or relate an experience

- To explain how to do or to make something

- To explain the steps in a process

Chronological order is mostly used in expository writing , which is a form of writing that narrates, describes, informs, or explains a process. When using chronological order, arrange the events in the order that they actually happened, or will happen if you are giving instructions. This method requires you to use words such as first , second , then , after that , later , and finally . These transition words guide you and your reader through the paper as you expand your thesis.

For example, if you are writing an essay about the history of the airline industry, you would begin with its conception and detail the essential timeline events up until present day. You would follow the chain of events using words such as first , then , next , and so on.

Writing at Work

At some point in your career you may have to file a complaint with your human resources department. Using chronological order is a useful tool in describing the events that led up to your filing the grievance. You would logically lay out the events in the order that they occurred using the key transition words. The more logical your complaint, the more likely you will be well received and helped.

Choose an accomplishment you have achieved in your life. The important moment could be in sports, schooling, or extracurricular activities. On your own sheet of paper, list the steps you took to reach your goal. Try to be as specific as possible with the steps you took. Pay attention to using transition words to focus your writing.

Keep in mind that chronological order is most appropriate for the following purposes:

- Writing essays containing heavy research

- Writing essays with the aim of listing, explaining, or narrating

- Writing essays that analyze literary works such as poems, plays, or books

When using chronological order, your introduction should indicate the information you will cover and in what order, and the introduction should also establish the relevance of the information. Your body paragraphs should then provide clear divisions or steps in chronology. You can divide your paragraphs by time (such as decades, wars, or other historical events) or by the same structure of the work you are examining (such as a line-by-line explication of a poem).

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that describes a process you are familiar with and can do well. Assume that your reader is unfamiliar with the procedure. Remember to use the chronological key words, such as first , second , then , and finally .

Order of Importance

Recall from Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” that order of importance is best used for the following purposes:

- Persuading and convincing

- Ranking items by their importance, benefit, or significance

- Illustrating a situation, problem, or solution

Most essays move from the least to the most important point, and the paragraphs are arranged in an effort to build the essay’s strength. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to begin with your most important supporting point, such as in an essay that contains a thesis that is highly debatable. When writing a persuasive essay, it is best to begin with the most important point because it immediately captivates your readers and compels them to continue reading.

For example, if you were supporting your thesis that homework is detrimental to the education of high school students, you would want to present your most convincing argument first, and then move on to the less important points for your case.

Some key transitional words you should use with this method of organization are most importantly , almost as importantly , just as importantly , and finally .

During your career, you may be required to work on a team that devises a strategy for a specific goal of your company, such as increasing profits. When planning your strategy you should organize your steps in order of importance. This demonstrates the ability to prioritize and plan. Using the order of importance technique also shows that you can create a resolution with logical steps for accomplishing a common goal.

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that discusses a passion of yours. Your passion could be music, a particular sport, filmmaking, and so on. Your paragraph should be built upon the reasons why you feel so strongly. Briefly discuss your reasons in the order of least to greatest importance.

Spatial Order

As stated in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , spatial order is best used for the following purposes:

- Helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it

- Evoking a scene using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound)

- Writing a descriptive essay

Spatial order means that you explain or describe objects as they are arranged around you in your space, for example in a bedroom. As the writer, you create a picture for your reader, and their perspective is the viewpoint from which you describe what is around you.

The view must move in an orderly, logical progression, giving the reader clear directional signals to follow from place to place. The key to using this method is to choose a specific starting point and then guide the reader to follow your eye as it moves in an orderly trajectory from your starting point.

Pay attention to the following student’s description of her bedroom and how she guides the reader through the viewing process, foot by foot.

Attached to my bedroom wall is a small wooden rack dangling with red and turquoise necklaces that shimmer as you enter. Just to the right of the rack is my window, framed by billowy white curtains. The peace of such an image is a stark contrast to my desk, which sits to the right of the window, layered in textbooks, crumpled papers, coffee cups, and an overflowing ashtray. Turning my head to the right, I see a set of two bare windows that frame the trees outside the glass like a 3D painting. Below the windows is an oak chest from which blankets and scarves are protruding. Against the wall opposite the billowy curtains is an antique dresser, on top of which sits a jewelry box and a few picture frames. A tall mirror attached to the dresser takes up most of the wall, which is the color of lavender.

The paragraph incorporates two objectives you have learned in this chapter: using an implied topic sentence and applying spatial order. Often in a descriptive essay, the two work together.

The following are possible transition words to include when using spatial order:

- Just to the left or just to the right

- On the left or on the right

- Across from

- A little further down

- To the south, to the east, and so on

- A few yards away

- Turning left or turning right

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph using spatial order that describes your commute to work, school, or another location you visit often.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Key Takeaways

- The way you organize your body paragraphs ensures you and your readers stay focused on and draw connections to, your thesis statement.

- A strong organizational pattern allows you to articulate, analyze, and clarify your thoughts.

- Planning the organizational structure for your essay before you begin to search for supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and directed research.

- Chronological order is most commonly used in expository writing. It is useful for explaining the history of your subject, for telling a story, or for explaining a process.

- Order of importance is most appropriate in a persuasion paper as well as for essays in which you rank things, people, or events by their significance.

- Spatial order describes things as they are arranged in space and is best for helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it; it creates a dominant impression.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

18 Essays ~ Choosing the Best Structure

Questions to Ponder ~ Your Dream Home

With a small group, discuss your “dream home.” What does it look like? Where is it? What material is it made of? Who lives there? What is the environment like outside the house? Search for some images of homes that appeal to you.

Can you compare and contrast the homes you and your partners chose? Can you make an argument for why your choice is the best?

As you begin to write an essay, you will need to think about the best structure for your ideas. Building an essay is like building a house: you need to think about audience (who will live in the house?), purpose (what will they do in the house?) and context (what in the environment like around the house?).

When you write an essay, you need to make decisions about what kind of structure is best to express your ideas clearly, and to meet the requirements of the assignment. It helps to think about your audience, purpose, and context as you consider your options.

Traditional Essay Format

One useful essay structure is the traditional 5-paragraph format. This format is typically taught in U.S. high schools. A 5-paragraph essay starts with an Introduction, which includes a thesis statement. The thesis statement often includes 3 controls, which are the points the writer intends to develop in the essay.

After the Introduction, there are three Body Paragraphs, which each start with a topic sentence. Each topic sentence introduces one of the controls from the thesis.

Finally, the Conclusion paragraph re-states the original thesis and leaves the reader with a final thought.

This format can be very useful when you start to practice writing an American English essay. Depending on the assignment prompt and/or the context, a 5-paragraph essay may be a good choice for ENGL 087. For example, if you are writing a timed, in-class essay, the 5-paragraph structure may be very useful. Or, if the assignment prompt asks you to explain three causes of obesity, the 5-paragraph structure might work. In these cases, your essay and your classmates’ essays may have similar points, and they will have the same structure. The 5-paragraph format can also be useful in standardized writing situations like TOEFL and IELTS.

College Essay Formats

However, many college instructors will expect your writing to go beyond the 5-paragraph structure. College professors expect you to think critically about your topic, not just write facts about it. They also expect you to take a stand about the topic, and to conduct research to support your ideas. In these cases, your essay and your classmates’ essays will probably be very different, even if your opinions are similar. Your essay will explain your unique opinion and ideas about the topic, in your own style. This is what makes college writing so interesting – for both the writer and the readers.

A strong college essay does incorporate some of the features of a 5-paragraph essay. For instance, a good Introduction will help open your essay. A catchy “hook” at the beginning will grab your readers’ attention and make them interested in reading your essay. Next, some background information can be useful, to explain more about your topic. A clear thesis statement here is very helpful to your readers – in a U.S. classroom, readers do not want to “hunt” for your overall main idea. For ENGL 087, most essays will require a one-paragraph Introduction. Longer essays for your future classes may need a longer Introduction.

After your Introduction paragraph, the Body Paragraphs will explain your main ideas. Use as many Body Paragraphs as you need to develop and explain your main ideas. Topic sentences can help main your main points clear. There is no “right” or “wrong” length for the Body Paragraphs; one guideline for college essays is to have paragraphs take two-thirds to three-fourths of a page, but they can be shorter or longer.

Your Conclusion paragraph should remind readers about your thesis. You should also leave your reader with a final thought, as in the traditional 5-paragraph essay. The kind of final thought will depend on the assignment prompt.

Here is a a general outline for a strong ENGL 087 essay. You can adapt this as you need to, depending on the assignment prompt:

I. Introduction

B. Background information

II. Body Paragraph

A. Topic sentence

1. supporting detail

2. supporting detail

(add as many supporting details as you need)

3. connection to next paragraph

III. (add as many Body Paragraphs as you need)

IV. Conclusion

A. reminder of thesis (re-state your thesis in a new way – do not just copy your original thesis here)

B. final thought (examples: call to action, opinion, rhetorical question, proposal, or prediction)

In some ways, this more open-ended college essay format is more challenging, because it does not provide a rigid structure for you to follow. But that is what makes it more interesting to write and to read: because it is not following a formula, you are free to develop and connect your ideas as you wish. You can build your “dream essay” without trying to fit ideas into a specific formula. It’s your choice as the author to decide which structure is the best for your purpose.

Is this chapter:

…about right, but you would like more examples? –> Read “ The Transition from High School to College Writing ” from the University of Toronto’s UC Writing Centre. Also see “ Types of Essays and Suggested Structures ” from Lumen’s Developmental English: Introduction to College Composition.

…too easy, or you would like more evidence for why the 5-paragraph format is not always effective? –> Read “ College Writing ” from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Writing Center and the module entitled “ Why It Matters: Beyond the 5-Paragraph Essay ” from Lumen’s Writing Skills Lab.

For more on the differences between 5-paragraph essays and less rigid structures, consult “ Formulaic vs. Organic Structure ” from Lumen’s Writing Skills Lab.

Note: links open in new tabs.

to think about

to have an opinion

ENGLISH 087: Academic Advanced Writing Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Hutchison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Modules 5 & 6 Writing Assignment: Writing an Argumentative Essay

As module five hopefully made clear, an argumentative essay is very similar to an example essay; it has a main point (a thesis statement) that makes a claim about a controversial issue (your subject matter), and you will support that claim with examples and specific details. You also likely will use emphatic order (building to your most important point, like arguing to a jury) to convince your reader of your position. The difference, as you now know after reading the module, is that argumentative essays require outside evidence, so you can’t just rely upon your personal experiences to provide examples to back up your points. Also, when writing an argumentative essay you must openly deal with the opposing point of view on your topic so that you don’t appear biased. This is because your writing to an undecided reader (in this case, your instructor) who is wary but curious and will question everything, so you want to appear fair and balanced even as you make sure to argue for your side of the issue.

If this kind of writing sounds like it requires a lot of work to get right, well, it is. Happily, since we know this is perhaps your first attempt at writing such a paper, we are going to make your life a bit easier by providing you with all of the outside sources you need to develop it. That’s right; you won’t have to do any outside research other than reading over the sources we provide (see step 4 of the writing process for links to the sources). Of course, you must still make sure to use those sources effectively in your actual essay and to cite them when appropriate! You also must provide a works cited or references page (depending upon whether you are using the MLA or APA format) at the end of the paper that lists the publishing information for whichever of these sources you decide to use. You should use at least two of the sources.

This assignment relies upon information provided in both modules five and six, so make sure you read over module six on citing academic sources before you get too far along. However, we wanted to give you the assignment now so that you have its requirements in the back of your mind as you learn about how to bring sources into your paper correctly.

With all of that out of the way, let’s get down to the assignment itself. Using the information in modules five and six as a guide, write a 2 to 4 page (500-1000 word) argumentative essay about the use of social media in contemporary society. You may either argue that it is beneficial to modern life or that it is destructive. To do so effectively, you must:

• explain the controversy over social media in your introduction (give necessary background information)

- present a clear thesis statement that announces your position on the issue

Step 1: Pre-Writing (Questioning, Freewriting, and Mapping)

- who is affected by it and in what ways/ for what reasons?

- when is it typically used? how often?

- where is it typically used?

You might use freewriting (the process of writing freely without worrying about grammar, spelling, and sentence structure) to generate ideas about social media, focusing on its benefits and negative traits, which will probably be easy to do since it is likely you use some form of it quite frequently.

Step 2: Focusing, Outlining, and Drafting

Once you’ve come up with the thesis (which should clearly take a side on the issue) and the examples and details that are going to help you prove it, you also need to consider the opposition’s point of view. In fact, you might want to go back and generate ideas for the opposing side in much the same way you did for your own side so that you better understand the opposition’s perspective. Ultimately you are required to discuss at least one of the opposing side’s points, so you need to have a good grasp of both positions.

Because this paper is complex, it is very, very important for you to organize your ideas in an outline. Perhaps more than any other essay in the course, an argumentative essay needs to be logical, and all of its components need to fit together in a way that is easy to understand for the reader. If an argument is not well organized, the reader will not find it to be credible and will likely remain unconvinced about the position the writer is taking. An outline will help ensure that you logically express your points while also explaining and perhaps refuting an opposing point-of-view.

As you fill out the outline, remember to choose an organizational plan before you start.

Here are two basic outlines to get you started. The first is the most common way to write an argumentative essay and proceeds by first addressing an opposing point of view in the first body paragraph and then providing all of your own points in favor of your position in the rest of the body paragraphs. You put the opposition first because you want to weigh your own ideas more heavily and you want the reader to finish the paper by thinking about your side, not the opposing side. The (perhaps more difficult) second outline follows a different strategy; each one of its body paragraphs addresses an opposing point and then uses evidence to show why it is wrong or misguided. This can be very convincing, but you must remember to clearly show why you disagree with the opposing point and then use evidence to back up your argument!

Note that you will either fill out the first or second outline, not both. As you know by now, the idea is to write out a quick summation of the different sections on the lines provided. When you go to write a full draft based on the outline you’ve chosen, you will add a hook at the beginning to flesh out your introduction (which should end in your thesis statement), and each of your general example sections will become body paragraphs. You will also need to add a conclusion explaining why your overall point is important.

Remember that these outlines are just suggestions, and you can include as many examples and body paragraphs as you want as long as you stay within the assignment’s length requirements:

Basic Argumentative Pattern I. Thesis Statement:

ii. Opposing Point: a. Evidence for

b. Evidence against (refute the point!)

iii. General Point #1: a. Evidence: b. Evidence:

iv. General Point #2: a. Evidence: b. Evidence:

v. General Point #3: a. Evidence: b. Evidence:

Alternative Argumentative Pattern I. Thesis Statement:

iii. Opposing Point: a. Evidence for

Post your “Argumentative Essay Outline” to the discussion board so that your instructor can give you some feedback before you begin drafting. You can either attach it to a thread as a Word file or just type it into the thread itself.

After you’ve finished outlining and received some feedback, you are ready to draft the actual paper.

As you’re drafting, remember that you have to accurately cite the sources inside your paper whenever information comes from one of them; this is called in-text citation. Module six explains how to do this, so read it over thoroughly.

Step 3: Revising, Editing, and Proofreading

Once your draft is finished, step away from it for at least a few hours so you can approach it with fresh eyes. It is also a very good idea to email it to a friend or fellow classmate or otherwise present it to a tutor or trusted family member to get feedback. Remember, writing doesn’t happen in a vacuum; it is meant to be read by an audience, and a writer can’t anticipate all of the potential issues an outside reader might have with an essay’s structure or language.

Whatever the case, after getting some feedback, read your essay over and consider what you might alter to make it clearer or more exciting.

Consider the following questions:

- Does the introduction provide a hook and explain the general controversy being discussed?

- Does the essay clearly take a position on the issue in a thesis statement?

the question, “what is important about all of this?” and/or “what should the

- Are there any fragments, run-on sentences, or comma splices?

Step 4: Making Your Works Cited or References Page

author’s name) is what you must tell the reader about when you cite it in the text. Regardless, make sure to put your list together at some point in the process. For our purposes you can classify each of these sources as a “page on a website” (what the MLA calls such sources) or a “nonperiodical web document” (what the APA calls such sources).

For the MLA, the information for this kind of works cited entry is as follows:

Author last name, Author first name. “Article Name.” Website title, date published, full URL (web address).

For the APA, the information for this kind of references page entry is as follows:

Author last name, First Initial. (date published). Article name. Retrieved from full URL (web address).

Look at the sample papers at the end of modules five and six to see examples of these pages. Format your papers according to the one that uses either the MLA or APA (whichever formatting style you are using for your own paper)

Here are the links to and the basic citation information for the provided sources:

Positive Effects of Social Media

Title: “Is it time for science to embrace cat videos?”

Author name: George Vlahakis Website Title: futurity.org Date Published: 17 June 2015 Source URL: http://www.futurity.org/cat-videos-943852/

Title: “#Snowing: How Tweets Can Make Winter Driving Safer”

Author Name: Cory Nealon Website Title: futurity.org Date Published: 2 December 2015 Source URL: http://www.futurity.org/twitter-weather-traffic-1060902-2/

Negative Effects of Social Media

Title: “Using Lots of Social Media Accounts Linked to Anxiety”

Author: Allison Hydzik Date Published: 19 December 2016 Source URL: http://www.futurity.org/social-media-depression-anxiety-1320622-2/

Title: “People Who Obsessively Check Social Media Get Less Sleep”

Author: Allison Hydzik Date Published: 16 January 2016 Source URL: http://www.futurity.org/social-media-sleep-1095922/

Step 5: Evaluation

After completing these steps, submit the essay to the instructor, who will evaluate it according to the grading criteria. (1)

English Composition I Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Testimonial

- Web Stories

Learning Home

Not Now! Will rate later

For and against Essays

Structure of ‘for and against’ Essay

The ‘for and against’ essay can be organized as follows:

Strategies to write a ‘for and against’ essay

- Language skills: Avoid using stereotyped phrases or expressions in your essay, especially in introductory and concluding paragraphs. E.g.: in modern society, in the current climate, throughout history, etc. Some of the words and phrases that can be used: To introduce points in favour/against: One point of view in favour of/against is that .. Some experts/scientists advocate/support/oppose the view that.. To point out opposing arguments: Opponents of this idea claim that .. Others oppose this viewpoint .. Some people may disagree with this idea. To state your conclusion: In my opinion .. Achieving a balance between X and Y would .. In conclusion, I firmly believe that .. On balance, I think it is unfair that .. To make contrasting points: On the other hand .. However.. It can be argued that .. Although..

- Decisive Interview, GD & Essay prep

- 100 Most Important Essay Topics for 2021

- Essay Writing for B-schools

- Top 100 Abstract Topics

- Essay Writing: Stepwise Approach

- Essay Writing: Grammar and Style

- Common Mistakes in Essay Writing

Precis Writing

- Actual Essay/ WAT topics

- Top Factual Essay Topics

- Essay Writing: Brainstorming Techniques

- Essay Writing: Sentence Structure

- Essay Writing: Do’s and Don’ts

- Evaluate your essay in terms of following parameters: Content: Make sure that appropriate transitional expressions are used to present reasons in favour of as well as against the topic. You should start the essay by stating the current situation. Argumentation: The arguments and justifications presented must be relevant to the given topic. Also, the concluding paragraph should include a balanced viewpoint of the topic. Essay Organization: The essay needs to be structured in a logical manner. Your personal opinion should be stated only in the concluding paragraph. Choice of words: Use opinion words (e.g. I think.., in my view, etc.) only in the concluding paragraph and not in the introductory or main body of the essay. Lastly, check your essay for any punctuation, grammatical or spelling mistakes.

Examples of ‘for and against’ Essay Topics:

- Money can buy happiness

- Smartphones- a blessing or curse?

- Online shopping

- Should euthanasia be illegal?

- Should death penalty be abolished?

- Home-schooling

- Animal rights and experimentation

- Group Discussions

- Personality

- Past Experiences

Most Popular Articles - PS

100 Essay Topics for 2024

Essay Writing/Written Ability Test (WAT) for B-schools

Case & Situation based Essay Topics

Argumentative Essays

Do's and Don'ts of Essay Writing

Opinion Essays

Descriptive Essays

Narrative Essays

Autobiographical Essay

Expository essay

Download our app.

- Learn on-the-go

- Unlimited Prep Resources

- Better Learning Experience

- Personalized Guidance

Get More Out of Your Exam Preparation - Try Our App!

How is an evaluative academic essay structured?

This is the third of four chapters about Evaluative Essays . To complete this reader, read each chapter carefully and then unlock and complete our materials to check your understanding.

– Introduce the possible structures of an evaluative essay

– Explain the block and point-by-point essay structures

– Provide an example introduction and body paragraph to help guide the reader

Chapter 1: What is an academic evaluative essay?

Chapter 2: How can I produce an effective evaluative essay?

Chapter 3: How is an evaluative academic essay structured?

Chapter 4: What is an example evaluative essay?

In Chapter 2 of this four-chapter reader, we discussed three important steps in the planning process of an evaluative essay that students should follow if they wish to ensure they’ve approached their topic in an effective and academic way. By using source materials , taking notes and creating tables of the most salient evaluative criteria, you should now have a clear set of arguments both for and against your topic and have formed a stance that includes your opinions and judgements. You should now therefore be ready to begin writing, and so this chapter focuses on the common essay structure of an evaluative essay . Please note that there is not one way of writing such an essay. The following structure is, however, commonly accepted to be clear, logical and well organised.

1. The Introduction

As with all academic essays , the introduction is the first paragraph that the reader will come into contact with, and so it’s therefore necessary to provide the reader with all the information they’ll need to contextualise and prepare them for the essay. To demonstrate an effectively written introduction, let’s first look at an example background information that contextualises our question from Chapter 1: ‘Evaluate the Impacts of Global Warming’.

The phenomenon that is often referred to as global warming was first coined in 1978 by climate scientist Alfred Sinclair. 1 Sinclair (1978 p. 95) announced to the world that the temperature of the Earth had increased by ‘half a degree in the last 30 years’. 2 Although it may not sound significant, this increase is more than the total increase of the previous 200,000 years (Mcleod, 1990). 3 The temperature has continued to rise since Sinclair’s announcement, which most scientists attribute to the significant increase in greenhouse gases that prevent solar radiation exiting the Earth’s atmosphere. 4 However, to what extent this phenomenon is going to negatively effect life on this planet is contested. 5

A logical set of background information to the topic of global warming would likely first introduce the broad topic and provide any key facts about it’s discovery and history to hook and engage the reader, as can be seen in sentences (1) and (2). After introducing the general topic (usually following a general-specific structure throughout the introduction ), the writer may then wish to include one or a number of optional elements, such as a focus on the significance of the topic (3), definitions of any key terminology or concepts (4), and perhaps a further narrowing of the topic focus in preparation of this essay’s thesis statement .

While the above elements may apply to any essay type , the next crucial step in constructing the introduction of an evaluative essay would be to include a thesis statement that outlines the specific focus and task of this essay, indicating also the writer’s stance and the criterion that will be presented and evaluated in the main body paragraphs in the form of an outline . What’s more, because it’s common in academic writing for an evaluative essay to present both counter-arguments and arguments (positive and negative criterion), perhaps the most common way of achieving all of these features within one thesis statement would be to follow a structure similar to the following:

Although some possible benefits may occur as a result of rising temperatures such as a localised increase in plant-life, this essay argues that global warming is having a mostly negative impact. 6 The majority of evidence indicates that the consequences of climate change are not only negatively impacting the global environment, but are increasing food and water scarcity and threatening the existence of the polar ice caps . 7

In sentence (6), the use of the dependent clause beginning with ‘although’ is one of the most effective ways for a student to include the counter-argument and argument and essay focus within a single sentence . In this case, the use of the word ‘possible’ acts as hedging language to weaken the claim that there are positives to global warming, while similarly the use of the word ‘mostly’ indicates acknowledgement that it’s not possible for the writer to be 100% confident in their stance . Finally, sentence (7), provides the outline of this essay’s body-paragraph main ideas . The outline signposts to the reader the main arguments of the essay in the same order that they will be presented in the body section .

2. The Body Section

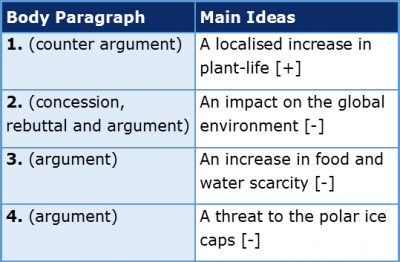

The aim of the body section of an evaluative essay is to coherently and concisely present convincing evidence both for and against the topic of the essay while maintaining the clarity of the overall writer stance . How the body section is structured may be quite varied, but judging by our outline as presented previously, our example essay on global warming follows what’s known as a block structure . As can be seen in the following table, a block structure usually deals first with the counter argument and then provides the main arguments of the essay in the subsequent body paragraphs

Please note here that to create a sophisticated argument, it’s also important for the writer to provide concession and rebuttal , in which certain aspects of the first paragraph’s counter argument are agreed with (conceded to) before a rebuttal of that same argument is provided in the form of opposing evidence.

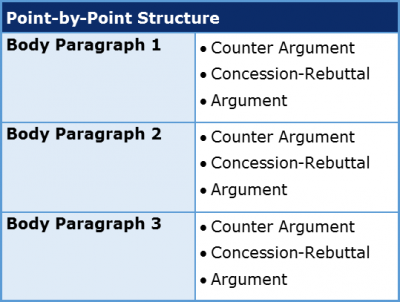

However, the block structure is not the only structure a student could follow for an evaluative essay body section. With a point-by-point structure, instead of simply providing one counter argument , a connected concession-rebuttal and argument and perhaps two additional arguments, the writer could provide counter argument, concession-rebuttal and argument for each of the essay’s main ideas, as is shown in the following structure:

Whichever structure you decide to follow or manipulate, it’s important in an evaluative essay that only one or (maximum) two main idea are explored within each paragraph. Having too many ideas and arguments will very likely weaken the claims made in that paragraph as there will be little room for a student to develop their argumentation or provide convincing supporting details .

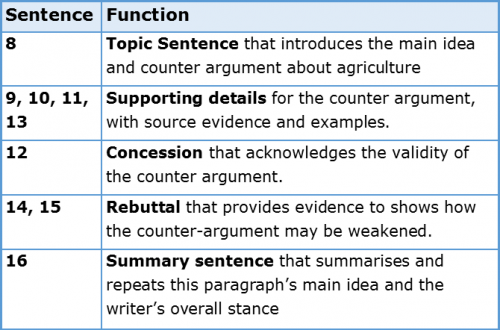

To make the body section of an evaluative essay somewhat clearer for you, we’ve deconstructed the first body paragraph from our example evaluative essay on global warming below: