- Join Newsletter

- Artist Gallery

- Get Started

It’s super easy to build a gorgeous artist website. No code. No credit card.

Use artweb's website builder today.

- Art And Culture

- Carol Burns

- December 1, 2022

What is Beauty in Art? And Does it Still Matter?

What is beauty in art? It’s an eternal question which tests our ideas of history, culture, geography, politics, race, religion, time and place. But the question remains: should art be beautiful? And if it should, what does beauty in art mean?

For those who gaze on artwork, “beautiful” is often one of the most common adjectives you will hear. But does beauty in art matter? And is it something an artist should aspire to?

What is the definition of beauty?

Without resorting to a dictionary, we can define beauty as a quality that attracts us. A visual feast. Something that brings joy or piques interest. A visual and emotional appreciation. But we can be as drawn to ugliness as we are to beauty. Think of a crooked tree next to a perfectly symmetrical one. It’s the warped and twisted branches that leave us contemplating the majesty of nature.

And, yes, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Culture influences the eye when it comes to defining beauty.

Our concept of beauty changes across history and time zones. There is no all-encompassing theory which can contain the vast complexities and richness of our view of beauty, any more than there is a grand unifying theory of anything.

So, what is beauty? That which we find alluring, aesthetic, foreign, pleasurable, sexual, covetous, inspirational, aspirational, divine, otherworldly and transcendent.

What is beauty in art?

The subject of beauty has always been a thorny one for many artists and critics to wrestle with. It’s in part due to the difficulty of defining beauty. But it also reflects evolving attitudes over time to the place of the role beauty should occupy in our public and private lives and how – and whether – art should embody these rarefied qualities.

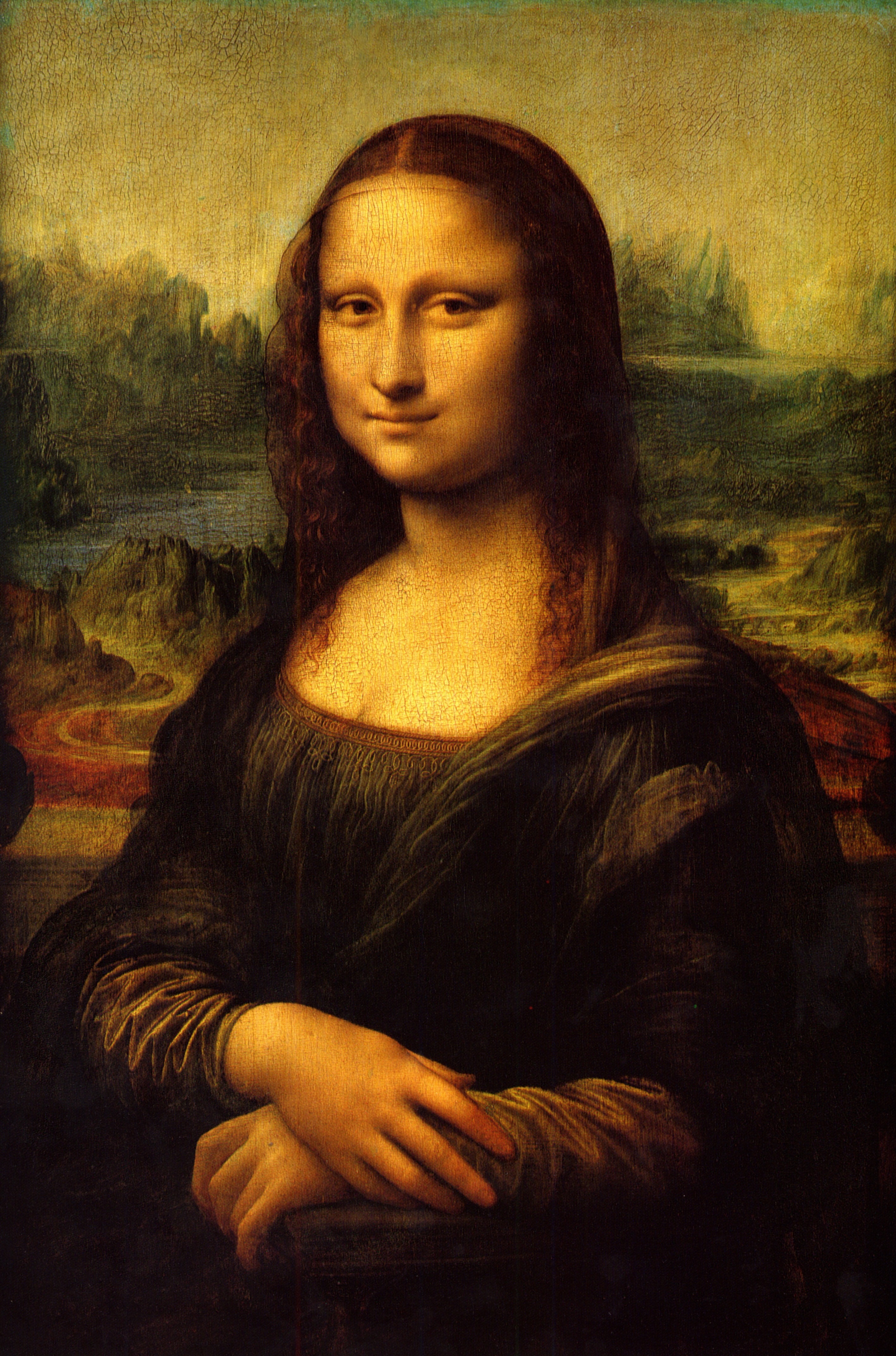

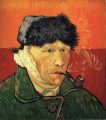

We are all routinely affected by everyday beauty: a stunning sunset, a person, or, of course, a work of art. These works will often reflect versions of everyday beauty: a landscape or the human form . But abstract art and 3D art often achieve beauty through color and texture. You are just as likely to hear someone talk of beauty standing in front of a Barbara Hepworth sculpture or a Mark Rothko painting as you are a work by J.W. Turner or Monet.

Is the beautiful inherently complex and contradictory?

But artwork is not one thing or another. Consider Casper David Friedrich’s romantic rendering of Two Men Contemplating the Moon . It’s a luminous composition with two gentle figures communing with nature. Yet there is something slightly gothic about the scene. Nature seems alive and brooding. The tree could be the “whomping willow” from Harry Potter. This painting allegedly inspired Samuel Beckett’s tragi-comic masterpiece Waiting for Godot . A play with the devastating line: “They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.” Is all of this then beauty?

Is a skull (the ultimate memento mori ) a beautiful object when painted beautifully? Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God is a platinum cast of an 18th-century human skull encrusted with 8,601 flawless diamonds and costs $50 million. Does the investment of money make beautiful artworks ugly and vulgar by its association? What about the medium? Mark Quinn’s Self is a self-portrait of the artist, using his blood set in frozen silicone, while Chris Ofili favors elephant dung as a medium.

In recent decades, these artists and their curators have contributed to a cultural conversation about whether cultural relativism fosters a “cult of ugliness” in contemporary art.

A short history of beauty in art

To consider where beauty stands in today’s art, let’s look to historical assessments of beauty in art.

For instance, the man hailed by many as the “father of art history,” Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-68), composed his History of Ancient Art long after the art of classical antiquity that he sought to study had been largely destroyed. That absence forced him to rely on the written records of ancient travelers and historians.

Despite this, Winckelmann fervently believed that beauty was not intrinsic to the work of art, but arose from a collaboration between the work and the viewer. His texts reveal a passion for beauty as a characteristic emerging from prolonged contemplation and reflection. These include his assessment that “the first view of beautiful statues is… like the first glance over the open sea; we gaze on it bewildered, and with undistinguishing eyes, but after we have contemplated it repeatedly the soul becomes more tranquil and the eye more quiet, and capable of separating the whole into its particulars.”

The journey to find beauty in the unfamiliar

Of no less relevance to today’s art lovers than to Winckelmann’s 18th century counterparts, he noted that he had “imposed upon myself the rule of not turning back until I had discovered some beauty.” He urged students to approach works of Greek art “favorably prepossessed… for, being fully assured of finding much that is beautiful, they will seek for it, and a portion of it will be made visible to them.”

Did the Conquistadores value pre-Colombian art in the same way as they valued Velasquez? What is more beautiful: Velasquez’s Portrait of Innocent X , or Francis Bacon’s homage to Velasquez (his favorite painter), one of his “screaming popes” terrorized and contorted in an existential hell? Look at those purples in Bacon’s pope’s vestments and how beautiful they are.

Would the Hellenistic mindset have found beauty in Moai statues? Did those artists in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century only discover a crude, untamed ugliness in those incredible artifacts plundered from the peoples of Africa?

For centuries, European and American art neglected Winckelmann’s insights on beauty. Instead of recognizing and celebrating the exquisite beauty in the arts of Africa, Asia, Latin American and the Pacific, these works were simply plagiarized and manipulated, while the inspiration was erased and denied.

What other artists think of beauty

Even putting aside JJ Winckelmann’s call for a sustained search for beauty even in those artworks that may not seem to yield it, there is plenty of reason for optimism about the role of beauty – or the lack of it – in the art of today.

Beauty has, for one thing, re-entered the critical conversation in recent decades. The Dutch artist Marlene Dumas (born 1953), for example, has mused that “one cannot paint a picture of or make an image of a woman and not deal with the concept of beauty.”

Fellow artist Agnes Martin (1912-2004), meanwhile, signaled her appreciation of beauty as existing in the present moment of the viewer’s judgement, when she declared in her 1989 essay “Beauty Is the Mystery of Life”: “When a beautiful rose dies, beauty does not die because it is not really in the rose. Beauty is an awareness in the mind. It is a mental and emotional response that we make.”

What do critics say about beauty?

As wordsmiths, art critics can often describe beauty better than us mere artists. Drawing these battle lines are such critics as JJ Charlesworth and Jonathan Jones. The former has reasoned that “beauty is one of those ideas that over the past 100 years or so has been slowly downgraded when it comes to considering the value of art … if anything, we [now] regard humanity as pretty ugly.” Jones, meanwhile, has suggested that “ the rejection of beauty as a creative ideal began not with modernism , but when modern art started believing its own press.”

And I finish with the controversial example of Immersion (Piss Christ) . This photo of a cheap plastic crucifix submerged in artist Andres Serrano’s own urine caused huge criticism, not least causing him to lose a valuable tax-funded art prize. But critic Lucy R. Lippard describes it as mysterious and beautiful. The controversy continues (In October 2022 the work sold for £130,000).

The beauty in ugliness and the ugliness in beauty

Do we still think of people with disabilities or deformities as unable to be beautiful? If I paint someone with a skin disease is it an ugly portrait? Is it degenerate art? Or shocking art? Or is it a dignified portrait of a beautiful soul, who appears a little different, physically speaking, to many others. Does your nude self-portrait conform to ideas of the body perfect?

There can also be a beauty in ugliness and an ugliness in beauty. Think Giacometti’s skeletal figures, or the grand drippings of paint in Pollock. What of Warhol’s Death and Disaster series? What of Goya’s Disasters of War ? Are Jeff Koon’s slick balloon dogs beautiful or ugly? Are they profound, or merely gaudy baubles for the rich to dump on their perfectly manicured lawns?

There are moments in many artworks which we may consider ugly and parts which we may consider beautiful. Perhaps the subject matter is unpleasant, but it is rendered beautifully in the medium of choice. A great example is Salvator Rosa’s painting in the National Gallery in London, Witches at their Incantations . It is a macabre scene of human desecration, yet the reds in the painting are some of the most beautiful you will ever see.

Regardless, the iconic artworks of recent decades shows us that beauty in art is by no means long gone. For example, Irish artist Mary Duffy’s evocations of statues like the Venus de Milo reveal the beauty of her own body. Equally, Greek artist Jannis Kounellis’ (1936-2017) juxtaposes fragmentary casts of ancient sculpture within a modern doorway for 1980s Untitled to explore concepts from identity to the immortality of art.

Should your work be beautiful?

So does beauty in art really matter? To use the firmest of clichés: beauty is fleeting. We would countenance today a cultural, moral, political and social attitude very different from those held by people in the past. That would take precedence across the globe.

Once, capturing beauty was a key part of an artist’s role , but what about today?

The young will not tolerate the same prejudicial attitudes towards race, culture, gender and sexuality, for instance, as their forbearers did. In the most progressive of circles today, black is as beautiful as white. Is there anyone more beautiful than Beyonce? A transgender woman is as beautiful as a cis-gender woman. Is there anyone more beautiful than Monroe Bergdorf ?

They are all as worthy of revelation, contemplation and celebration as each other. The hierarchical of the past are the heterarchical of the future. All are created equally beautiful.

Is beauty a myth or is it real? Is it identifiable, quantifiable, qualifiedly, marketable and saleable. Billionaires purchase it in abundance. Does it make them more beautiful for doing so?

In the end, beauty in art is a fluttering of the eye, a shivering of the skin, a shudder in the intellect. It is that moment when the soul swoons, or the heart sinks, in being, or elation, or wanderlust. A brief instant in collaboration with the senses: a glimpse of melancholy, or pulse of nostalgia. It is a movement, a pause, a glimpse, a beat. It is everything and it is nothing. A moment when we appreciate it all and then contemplate none of it. Beauty is fleeting, regardless, defiant, vulgar and aloof. It is worth knowing once and worth dying for twice.

As an artist, we all have our own ideas of beauty and how to render that on canvas. Perhaps the only question worth asking is do you want beauty in your work?

Related posts:

Ready to Grow Your Art Business?

Join our bi-weekly newsletter to receive exclusive access to the free tools, discounts and marketing tips that help 66,000 artists sell more art., recent posts, the best international art competitions 2023, what the judges say: how to win art competitions, email marketing for artists: a beginner’s guide, art as a second career, how to price your artwork and increase its value, the best painting competitions for artists, search our blog, create your website, join our artists newsletter.

A monthly newsletter of what’s hot on Artweb, made by Artists for Artists.

Ready to have your own art website today, but don’t know where to start?

Artweb’s got you covered.

No coding, no stress, so you can spend more time on your art, not your website.

Sell Online With Zero Commissions.

Just for Artists

Join thousands of artists who subscribe to The Artists Newsletter .

Just wanted to say what a fantastic support/info system you run. I've just read the newsletter regarding image copyright law and it's very informative... thanks!"

Friday essay: in defence of beauty in art

Senior Lecturer, Art History and Visual Culture, Australian National University

Disclosure statement

Robert Wellington receives funding from Australian Research Council. Material in this article was first presented as the Australian National University 2017 Last Lecture.

Australian National University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Art critics and historians have a difficult time dealing with beauty. We are trained from early on that the analysis of a work of art relies on proof, those things that we can point to as evidence. The problem with beauty is that it’s almost impossible to describe. To describe the beauty of an object is like trying to explain why something’s funny — when it’s put into words, the moment is lost.

Works of art need not be beautiful for us to consider them important. We need only think of Marcel Duchamp’s “readymade” urinal that he flipped on its side, signed with a false name, and submitted to the exhibition of the newly founded Society of Independent Artists in New York in 1917. We’d have a hard time considering this object beautiful, but it is widely accepted to be one of most important works of Western art from the last century.

To call something beautiful is not a critical assertion, so it’s deemed of little value to an argument that attempts to understand the morals, politics, and ideals of human cultures past and present. To call something beautiful is not the same as calling it an important work of art. As a philosopher might say, beauty is not a necessary condition of the art object.

And yet, it is often the beauty we perceive in works of art from the past or from another culture that makes them so compelling. When we recognise the beauty of an object made or selected by another person we understand that maker/selector as a feeling subject who shared with us an ineffable aesthetic experience. When we find something beautiful we become aware of our mutual humanity.

Take, for example, the extraordinary painting Yam awely by Emily Kam Kngwarry in our national collection. Like so many Indigenous Australians, Kngwarry has evoked her deep spiritual and cultural connection to the lands that we share through some of the most intensely beautiful objects made by human hands.

In her work we can trace the lines of the brush, the wet-on-wet blend of colours intuitively selected, the place of the artist’s body as she moved about the canvas to complete her design. We can uncover her choices—the mix of predetermination and instinct of a maker in the flow of creation.

It is not our cultural differences that strike me when I look at this painting. I know that a complex set of ideas, stories, and experiences have informed its maker. But what captures me is beyond reason. It cannot be put into words. My felt response to this work does not answer questions of particular cultures or histories. It is more universal than that. I am aware of a beautiful object offered up by its maker, who surely felt the beauty of her creation just as I do.

Let me be clear. I am not saying that works of art ought to be beautiful. What I want to defend is our felt experience of beauty as way of knowing and navigating the world around us.

The aesthete as radical

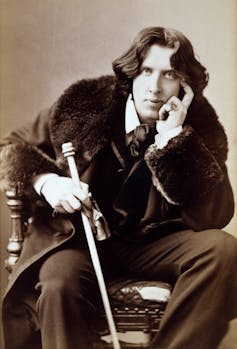

The aesthete — a much maligned figure of late-19th and early-20th century provides a fascinating insight on this topic. Aesthetes have had a bad rap. To call someone an aesthete is almost an insult. It suggests that they are frivolous, vain, privileged, and affected. But I would like to reposition aesthetes as radical, transgressive figures, who challenged the very foundations of the conservative culture in which they lived, though an all-consuming love of beautiful things.

Oscar Wilde was, perhaps, the consummate Aesthete - famed as much for his wit as for his foppish dress and his love of peacock feathers, sun flowers and objets d’art. His often-quoted comment “I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china” has been noted as a perfect summary of the aesthete’s vacuous nature.

For Wilde and his followers, the work of art — whether it be a poem, a book, a play, a piece of music, a painting, a dinner plate, or a carpet — should only be judged on the grounds of beauty. They considered it an utterly vulgar idea that art should serve any other purpose.

Over time, the term “aesthete” began to take on new meanings as a euphemism for the effete Oxford intellectual. Men like Wilde were an open threat to acceptable gender norms—the pursuit of beauty, both in the adoration of beautiful things, and in the pursuit of personal appearances, was deemed unmanly. It had long been held that men and women approached the world differently. Men were rational and intellectual; women emotional and irrational.

These unfortunate stereotypes are very familiar to us, and they play both ways. When a woman is confident and intellectual she is sometimes deemed unfeminine. When she is emotional and empathic, she is at risk of being called hysterical. Likewise, a man who works in the beauty industry — a make-up artist, fashion designer, hairdresser, or interior designer — might be mocked for being effete and superficial. We only need to look to the tasteless comments made about Prime Minister Julia Gillard and her partner Tim Mathieson to see evidence of that today.

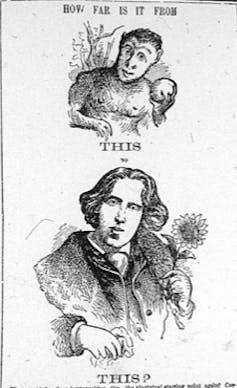

By the 1880s, many caricatures were published of a flamboyant Wilde as a cultivated aesthete. One cartoon from the Washington Post lampooned the aesthete with a reference to Charles Darwin’s controversial theory of evolution. How far is the aesthete from the ape, it asked. Here the pun relies on a comparison made between the irrational ape — Darwin’s original human — and Wilde the frivolous aesthete.

The aesthete was a dangerous combination of male privilege, class privilege, and female sensibility. The queerness of aesthetes like Wilde was dangerously transgressive, and the pursuit of beauty provided a zone in which to challenge the heteronormative foundations of conservative society, just as Darwin’s radical theories had challenged Christian beliefs of the origins of humankind.

Wilde’s legacy was continued by a new generation of young aristocrats at a time of cultural crises between the two World Wars. The Bright Young Things, as they were called, were the last bloom of a dying plant — the last generation of British aristocrats to lead a life of unfettered leisure before so many were cut down in their prime by the war that permanently altered the economic structure of Britain.

Stephen Tennant was the brightest of the Bright Young Things. He was the youngest son of a Scottish peer, a delicate and sickly child whose recurrent bouts of lung disease lent him a thin, delicate, consumptive and romantic appearance.

Stephen was immortalised as the character of Lord Sebastian Flyte in Evelyn Waugh’s masterpiece, Brideshead Revisited. Waugh’s character of the frivolous Oxford Aesthete who carries around his teddy bear, Aloysius, and dotes on his Nanny, borrows these characteristics from Stephen — who kept a plush monkey as a constant companion right up until his death.

Waugh’s book is a powerful meditation on art, beauty and faith. The narrator, Charles Ryder, is thought to have been loosely based on Tennant’s close friend, the painter/illustrator Rex Whistler, the aesthete-artist who tragically died on his first day of engagement in the Second World War.

Through the character of Charles, Waugh grapples with the dilemma of beauty vs erudition. Visiting Brideshead, the magnificent country estate of Sebastian’s family, Charles is keen to learn its history and to train his eye. He asks his host, “Is the dome by Inigo Jones, too? It looks later.” Sebastian replies: “Oh, Charles, don’t be such a tourist. What does it matter when it was built, if it’s pretty?” Sebastian gives the aesthete’s response, that a work of art or architecture should be judged on aesthetic merit alone.

I’m not suggesting that we should all drop what we’re doing and quit our jobs to pursue an uncompromising pursuit of beauty. But I do think we can learn something from the aesthete’s approach to life.

Aesthetes like Wilde and Tennant, cushioned by their privilege, transgressed the accepted norms of their gender to pursue a life not governed by reason but by feeling. This is a radical challenge to our logocentric society; a challenge to a world that often privileges a rational (masculine) perspective that fails to account for our deeply felt experience of the world around us.

How, then, to judge works of art?

How, then, should the art critic proceed today when beauty counts for so little in the judgement of works of art?

The unsettling times in which we live lead us to question the ethics of aesthetics. What happens when we find an object beautiful that was produced by a person or in a culture that we judge to be immoral or unjust?

I often encounter this problem with works of art produced for the French court in the 17th and 18th century – the period I study.

Last year, when I took a group through the exhibition Versailles: Treasures from the Palace at the National Gallery of Australia, one student was particularly repulsed by Sèvres porcelain made for members of the Court of French king Louis XV . For her, it was impossible to like those dishes and bowls, because she felt they represented the extraordinary inequity of Old Regime France – these exquisitely refined objects were produced at the expense of the suffering poor, she thought.

I suppose that might be true, but I can’t help it – I find this porcelain irresistibly beautiful.

The vibrant bleu-celeste glaze, the playful rhythm of ribbons and garlands of flowers, those delicate renderings painted by hand with the tiniest of brushes. It is the beauty of such objects that compels me to learn more about them.

When it was first made, Sèvres porcelain demonstrated the union of science and art. We are meant to marvel at the chemistry and artistry required to transform minerals, metal and clay into a sparkling profusion of decoration. This porcelain was the material embodiment of France as an advanced and flourishing nation.

You might well argue that the politics of 18th-century porcelain is bad. But our instinctual perception of beauty precedes the reasoned judgement of art.

The artists and makers at the Sèvres factory were responding to the human capacity to perceive beauty. These objects were designed to engage our aesthetic sensibilities.

Works of art don’t have to be beautiful, but we must acknowledge that aesthetic judgement plays a large part in the reception of art. Beauty might not be an objective quality in the work of art, nor is it a rational way for us to argue for the cultural importance of an object. It’s not something we can teach, and perhaps it’s not something you can learn.

But when it comes down to it, our ability to perceive beauty is often what makes a work of art compelling. It is a feeling that reveals a pure moment of humanity that we share with the maker, transcending time and place.

- Indigenous art

- Friday essay

- Oscar Wilde

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Student Wellbeing Officer

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Question of the Month

What is art and/or what is beauty, the following answers to this artful question each win a random book..

Art is something we do, a verb. Art is an expression of our thoughts, emotions, intuitions, and desires, but it is even more personal than that: it’s about sharing the way we experience the world, which for many is an extension of personality. It is the communication of intimate concepts that cannot be faithfully portrayed by words alone. And because words alone are not enough, we must find some other vehicle to carry our intent. But the content that we instill on or in our chosen media is not in itself the art. Art is to be found in how the media is used, the way in which the content is expressed.

What then is beauty? Beauty is much more than cosmetic: it is not about prettiness. There are plenty of pretty pictures available at the neighborhood home furnishing store; but these we might not refer to as beautiful; and it is not difficult to find works of artistic expression that we might agree are beautiful that are not necessarily pretty. Beauty is rather a measure of affect, a measure of emotion. In the context of art, beauty is the gauge of successful communication between participants – the conveyance of a concept between the artist and the perceiver. Beautiful art is successful in portraying the artist’s most profound intended emotions, the desired concepts, whether they be pretty and bright, or dark and sinister. But neither the artist nor the observer can be certain of successful communication in the end. So beauty in art is eternally subjective.

Wm. Joseph Nieters, Lake Ozark, Missouri

Works of art may elicit a sense of wonder or cynicism, hope or despair, adoration or spite; the work of art may be direct or complex, subtle or explicit, intelligible or obscure; and the subjects and approaches to the creation of art are bounded only by the imagination of the artist. Consequently, I believe that defining art based upon its content is a doomed enterprise.

Now a theme in aesthetics, the study of art, is the claim that there is a detachment or distance between works of art and the flow of everyday life. Thus, works of art rise like islands from a current of more pragmatic concerns. When you step out of a river and onto an island, you’ve reached your destination. Similarly, the aesthetic attitude requires you to treat artistic experience as an end-in-itself : art asks us to arrive empty of preconceptions and attend to the way in which we experience the work of art. And although a person can have an ‘aesthetic experience’ of a natural scene, flavor or texture, art is different in that it is produced . Therefore, art is the intentional communication of an experience as an end-in-itself . The content of that experience in its cultural context may determine whether the artwork is popular or ridiculed, significant or trivial, but it is art either way.

One of the initial reactions to this approach may be that it seems overly broad. An older brother who sneaks up behind his younger sibling and shouts “Booo!” can be said to be creating art. But isn’t the difference between this and a Freddy Krueger movie just one of degree? On the other hand, my definition would exclude graphics used in advertising or political propaganda, as they are created as a means to an end and not for their own sakes. Furthermore, ‘communication’ is not the best word for what I have in mind because it implies an unwarranted intention about the content represented. Aesthetic responses are often underdetermined by the artist’s intentions.

Mike Mallory, Everett, WA

The fundamental difference between art and beauty is that art is about who has produced it, whereas beauty depends on who’s looking.

Of course there are standards of beauty – that which is seen as ‘traditionally’ beautiful. The game changers – the square pegs, so to speak – are those who saw traditional standards of beauty and decided specifically to go against them, perhaps just to prove a point. Take Picasso, Munch, Schoenberg, to name just three. They have made a stand against these norms in their art. Otherwise their art is like all other art: its only function is to be experienced, appraised, and understood (or not).

Art is a means to state an opinion or a feeling, or else to create a different view of the world, whether it be inspired by the work of other people or something invented that’s entirely new. Beauty is whatever aspect of that or anything else that makes an individual feel positive or grateful. Beauty alone is not art, but art can be made of, about or for beautiful things. Beauty can be found in a snowy mountain scene: art is the photograph of it shown to family, the oil interpretation of it hung in a gallery, or the music score recreating the scene in crotchets and quavers.

However, art is not necessarily positive: it can be deliberately hurtful or displeasing: it can make you think about or consider things that you would rather not. But if it evokes an emotion in you, then it is art.

Chiara Leonardi, Reading, Berks

Art is a way of grasping the world. Not merely the physical world, which is what science attempts to do; but the whole world, and specifically, the human world, the world of society and spiritual experience.

Art emerged around 50,000 years ago, long before cities and civilisation, yet in forms to which we can still directly relate. The wall paintings in the Lascaux caves, which so startled Picasso, have been carbon-dated at around 17,000 years old. Now, following the invention of photography and the devastating attack made by Duchamp on the self-appointed Art Establishment [see Brief Lives this issue], art cannot be simply defined on the basis of concrete tests like ‘fidelity of representation’ or vague abstract concepts like ‘beauty’. So how can we define art in terms applying to both cave-dwellers and modern city sophisticates? To do this we need to ask: What does art do ? And the answer is surely that it provokes an emotional, rather than a simply cognitive response. One way of approaching the problem of defining art, then, could be to say: Art consists of shareable ideas that have a shareable emotional impact. Art need not produce beautiful objects or events, since a great piece of art could validly arouse emotions other than those aroused by beauty, such as terror, anxiety, or laughter. Yet to derive an acceptable philosophical theory of art from this understanding means tackling the concept of ‘emotion’ head on, and philosophers have been notoriously reluctant to do this. But not all of them: Robert Solomon’s book The Passions (1993) has made an excellent start, and this seems to me to be the way to go.

It won’t be easy. Poor old Richard Rorty was jumped on from a very great height when all he said was that literature, poetry, patriotism, love and stuff like that were philosophically important. Art is vitally important to maintaining broad standards in civilisation. Its pedigree long predates philosophy, which is only 3,000 years old, and science, which is a mere 500 years old. Art deserves much more attention from philosophers.

Alistair MacFarlane, Gwynedd

Some years ago I went looking for art. To begin my journey I went to an art gallery. At that stage art to me was whatever I found in an art gallery. I found paintings, mostly, and because they were in the gallery I recognised them as art. A particular Rothko painting was one colour and large. I observed a further piece that did not have an obvious label. It was also of one colour – white – and gigantically large, occupying one complete wall of the very high and spacious room and standing on small roller wheels. On closer inspection I saw that it was a moveable wall, not a piece of art. Why could one piece of work be considered ‘art’ and the other not?

The answer to the question could, perhaps, be found in the criteria of Berys Gaut to decide if some artefact is, indeed, art – that art pieces function only as pieces of art, just as their creators intended.

But were they beautiful? Did they evoke an emotional response in me? Beauty is frequently associated with art. There is sometimes an expectation of encountering a ‘beautiful’ object when going to see a work of art, be it painting, sculpture, book or performance. Of course, that expectation quickly changes as one widens the range of installations encountered. The classic example is Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a rather un-beautiful urinal.

Can we define beauty? Let me try by suggesting that beauty is the capacity of an artefact to evoke a pleasurable emotional response. This might be categorised as the ‘like’ response.

I definitely did not like Fountain at the initial level of appreciation. There was skill, of course, in its construction. But what was the skill in its presentation as art?

So I began to reach a definition of art. A work of art is that which asks a question which a non-art object such as a wall does not: What am I? What am I communicating? The responses, both of the creator artist and of the recipient audience, vary, but they invariably involve a judgement, a response to the invitation to answer. The answer, too, goes towards deciphering that deeper question – the ‘Who am I?’ which goes towards defining humanity.

Neil Hallinan, Maynooth, Co. Kildare

‘Art’ is where we make meaning beyond language. Art consists in the making of meaning through intelligent agency, eliciting an aesthetic response. It’s a means of communication where language is not sufficient to explain or describe its content. Art can render visible and known what was previously unspoken. Because what art expresses and evokes is in part ineffable, we find it difficult to define and delineate it. It is known through the experience of the audience as well as the intention and expression of the artist. The meaning is made by all the participants, and so can never be fully known. It is multifarious and on-going. Even a disagreement is a tension which is itself an expression of something.

Art drives the development of a civilisation, both supporting the establishment and also preventing subversive messages from being silenced – art leads, mirrors and reveals change in politics and morality. Art plays a central part in the creation of culture, and is an outpouring of thought and ideas from it, and so it cannot be fully understood in isolation from its context. Paradoxically, however, art can communicate beyond language and time, appealing to our common humanity and linking disparate communities. Perhaps if wider audiences engaged with a greater variety of the world’s artistic traditions it could engender increased tolerance and mutual respect.

Another inescapable facet of art is that it is a commodity. This fact feeds the creative process, whether motivating the artist to form an item of monetary value, or to avoid creating one, or to artistically commodify the aesthetic experience. The commodification of art also affects who is considered qualified to create art, comment on it, and even define it, as those who benefit most strive to keep the value of ‘art objects’ high. These influences must feed into a culture’s understanding of what art is at any time, making thoughts about art culturally dependent. However, this commodification and the consequent closely-guarded role of the art critic also gives rise to a counter culture within art culture, often expressed through the creation of art that cannot be sold. The stratification of art by value and the resultant tension also adds to its meaning, and the meaning of art to society.

Catherine Bosley, Monk Soham, Suffolk

First of all we must recognize the obvious. ‘Art’ is a word, and words and concepts are organic and change their meaning through time. So in the olden days, art meant craft. It was something you could excel at through practise and hard work. You learnt how to paint or sculpt, and you learnt the special symbolism of your era. Through Romanticism and the birth of individualism, art came to mean originality. To do something new and never-heard-of defined the artist. His or her personality became essentially as important as the artwork itself. During the era of Modernism, the search for originality led artists to reevaluate art. What could art do? What could it represent? Could you paint movement (Cubism, Futurism)? Could you paint the non-material (Abstract Expressionism)? Fundamentally: could anything be regarded as art? A way of trying to solve this problem was to look beyond the work itself, and focus on the art world: art was that which the institution of art – artists, critics, art historians, etc – was prepared to regard as art, and which was made public through the institution, e.g. galleries. That’s Institutionalism – made famous through Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades.

Institutionalism has been the prevailing notion through the later part of the twentieth century, at least in academia, and I would say it still holds a firm grip on our conceptions. One example is the Swedish artist Anna Odell. Her film sequence Unknown woman 2009-349701 , for which she faked psychosis to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital, was widely debated, and by many was not regarded as art. But because it was debated by the art world, it succeeded in breaking into the art world, and is today regarded as art, and Odell is regarded an artist.

Of course there are those who try and break out of this hegemony, for example by refusing to play by the art world’s unwritten rules. Andy Warhol with his Factory was one, even though he is today totally embraced by the art world. Another example is Damien Hirst, who, much like Warhol, pays people to create the physical manifestations of his ideas. He doesn’t use galleries and other art world-approved arenas to advertise, and instead sells his objects directly to private individuals. This liberal approach to capitalism is one way of attacking the hegemony of the art world.

What does all this teach us about art? Probably that art is a fleeting and chimeric concept. We will always have art, but for the most part we will only really learn in retrospect what the art of our era was.

Tommy Törnsten, Linköping, Sweden

Art periods such as Classical, Byzantine, neo-Classical, Romantic, Modern and post-Modern reflect the changing nature of art in social and cultural contexts; and shifting values are evident in varying content, forms and styles. These changes are encompassed, more or less in sequence, by Imitationalist, Emotionalist, Expressivist, Formalist and Institutionalist theories of art. In The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1981), Arthur Danto claims a distinctiveness for art that inextricably links its instances with acts of observation, without which all that could exist are ‘material counterparts’ or ‘mere real things’ rather than artworks. Notwithstanding the competing theories, works of art can be seen to possess ‘family resemblances’ or ‘strands of resemblance’ linking very different instances as art. Identifying instances of art is relatively straightforward, but a definition of art that includes all possible cases is elusive. Consequently, art has been claimed to be an ‘open’ concept.

According to Raymond Williams’ Keywords (1976), capitalised ‘Art’ appears in general use in the nineteenth century, with ‘Fine Art’; whereas ‘art’ has a history of previous applications, such as in music, poetry, comedy, tragedy and dance; and we should also mention literature, media arts, even gardening, which for David Cooper in A Philosophy of Gardens (2006) can provide “epiphanies of co-dependence”. Art, then, is perhaps “anything presented for our aesthetic contemplation” – a phrase coined by John Davies, former tutor at the School of Art Education, Birmingham, in 1971 – although ‘anything’ may seem too inclusive. Gaining our aesthetic interest is at least a necessary requirement of art. Sufficiency for something to be art requires significance to art appreciators which endures as long as tokens or types of the artwork persist. Paradoxically, such significance is sometimes attributed to objects neither intended as art, nor especially intended to be perceived aesthetically – for instance, votive, devotional, commemorative or utilitarian artefacts. Furthermore, aesthetic interests can be eclipsed by dubious investment practices and social kudos. When combined with celebrity and harmful forms of narcissism, they can egregiously affect artistic authenticity. These interests can be overriding, and spawn products masquerading as art. Then it’s up to discerning observers to spot any Fads, Fakes and Fantasies (Sjoerd Hannema, 1970).

Colin Brookes, Loughborough, Leicestershire

For me art is nothing more and nothing less than the creative ability of individuals to express their understanding of some aspect of private or public life, like love, conflict, fear, or pain. As I read a war poem by Edward Thomas, enjoy a Mozart piano concerto, or contemplate a M.C. Escher drawing, I am often emotionally inspired by the moment and intellectually stimulated by the thought-process that follows. At this moment of discovery I humbly realize my views may be those shared by thousands, even millions across the globe. This is due in large part to the mass media’s ability to control and exploit our emotions. The commercial success of a performance or production becomes the metric by which art is now almost exclusively gauged: quality in art has been sadly reduced to equating great art with sale of books, number of views, or the downloading of recordings. Too bad if personal sensibilities about a particular piece of art are lost in the greater rush for immediate acceptance.

So where does that leave the subjective notion that beauty can still be found in art? If beauty is the outcome of a process by which art gives pleasure to our senses, then it should remain a matter of personal discernment, even if outside forces clamour to take control of it. In other words, nobody, including the art critic, should be able to tell the individual what is beautiful and what is not. The world of art is one of a constant tension between preserving individual tastes and promoting popular acceptance.

Ian Malcomson, Victoria, British Columbia

What we perceive as beautiful does not offend us on any level. It is a personal judgement, a subjective opinion. A memory from once we gazed upon something beautiful, a sight ever so pleasing to the senses or to the eye, oft time stays with us forever. I shall never forget walking into Balzac’s house in France: the scent of lilies was so overwhelming that I had a numinous moment. The intensity of the emotion evoked may not be possible to explain. I don’t feel it’s important to debate why I think a flower, painting, sunset or how the light streaming through a stained-glass window is beautiful. The power of the sights create an emotional reaction in me. I don’t expect or concern myself that others will agree with me or not. Can all agree that an act of kindness is beautiful?

A thing of beauty is a whole; elements coming together making it so. A single brush stroke of a painting does not alone create the impact of beauty, but all together, it becomes beautiful. A perfect flower is beautiful, when all of the petals together form its perfection; a pleasant, intoxicating scent is also part of the beauty.

In thinking about the question, ‘What is beauty?’, I’ve simply come away with the idea that I am the beholder whose eye it is in. Suffice it to say, my private assessment of what strikes me as beautiful is all I need to know.

Cheryl Anderson, Kenilworth, Illinois

Stendhal said, “Beauty is the promise of happiness”, but this didn’t get to the heart of the matter. Whose beauty are we talking about? Whose happiness?

Consider if a snake made art. What would it believe to be beautiful? What would it deign to make? Snakes have poor eyesight and detect the world largely through a chemosensory organ, the Jacobson’s organ, or through heat-sensing pits. Would a movie in its human form even make sense to a snake? So their art, their beauty, would be entirely alien to ours: it would not be visual, and even if they had songs they would be foreign; after all, snakes do not have ears, they sense vibrations. So fine art would be sensed, and songs would be felt, if it is even possible to conceive that idea.

From this perspective – a view low to the ground – we can see that beauty is truly in the eye of the beholder. It may cross our lips to speak of the nature of beauty in billowy language, but we do so entirely with a forked tongue if we do so seriously. The aesthetics of representing beauty ought not to fool us into thinking beauty, as some abstract concept, truly exists. It requires a viewer and a context, and the value we place on certain combinations of colors or sounds over others speaks of nothing more than preference. Our desire for pictures, moving or otherwise, is because our organs developed in such a way. A snake would have no use for the visual world.

I am thankful to have human art over snake art, but I would no doubt be amazed at serpentine art. It would require an intellectual sloughing of many conceptions we take for granted. For that, considering the possibility of this extreme thought is worthwhile: if snakes could write poetry, what would it be?

Derek Halm, Portland, Oregon

[A: Sssibilance and sussssuration – Ed.]

The questions, ‘What is art?’ and ‘What is beauty?’ are different types and shouldn’t be conflated.

With boring predictability, almost all contemporary discussers of art lapse into a ‘relative-off’, whereby they go to annoying lengths to demonstrate how open-minded they are and how ineluctably loose the concept of art is. If art is just whatever you want it to be, can we not just end the conversation there? It’s a done deal. I’ll throw playdough on to a canvas, and we can pretend to display our modern credentials of acceptance and insight. This just doesn’t work, and we all know it. If art is to mean anything , there has to be some working definition of what it is. If art can be anything to anybody at anytime, then there ends the discussion. What makes art special – and worth discussing – is that it stands above or outside everyday things, such as everyday food, paintwork, or sounds. Art comprises special or exceptional dishes, paintings, and music.

So what, then, is my definition of art? Briefly, I believe there must be at least two considerations to label something as ‘art’. The first is that there must be something recognizable in the way of ‘author-to-audience reception’. I mean to say, there must be the recognition that something was made for an audience of some kind to receive, discuss or enjoy. Implicit in this point is the evident recognizability of what the art actually is – in other words, the author doesn’t have to tell you it’s art when you otherwise wouldn’t have any idea. The second point is simply the recognition of skill: some obvious skill has to be involved in making art. This, in my view, would be the minimum requirements – or definition – of art. Even if you disagree with the particulars, some definition is required to make anything at all art. Otherwise, what are we even discussing? I’m breaking the mold and ask for brass tacks.

Brannon McConkey, Tennessee Author of Student of Life: Why Becoming Engaged in Life, Art, and Philosophy Can Lead to a Happier Existence

Human beings appear to have a compulsion to categorize, to organize and define. We seek to impose order on a welter of sense-impressions and memories, seeing regularities and patterns in repetitions and associations, always on the lookout for correlations, eager to determine cause and effect, so that we might give sense to what might otherwise seem random and inconsequential. However, particularly in the last century, we have also learned to take pleasure in the reflection of unstructured perceptions; our artistic ways of seeing and listening have expanded to encompass disharmony and irregularity. This has meant that culturally, an ever-widening gap has grown between the attitudes and opinions of the majority, who continue to define art in traditional ways, having to do with order, harmony, representation; and the minority, who look for originality, who try to see the world anew, and strive for difference, and whose critical practice is rooted in abstraction. In between there are many who abjure both extremes, and who both find and give pleasure both in defining a personal vision and in practising craftsmanship.

There will always be a challenge to traditional concepts of art from the shock of the new, and tensions around the appropriateness of our understanding. That is how things should be, as innovators push at the boundaries. At the same time, we will continue to take pleasure in the beauty of a mathematical equation, a finely-tuned machine, a successful scientific experiment, the technology of landing a probe on a comet, an accomplished poem, a striking portrait, the sound-world of a symphony. We apportion significance and meaning to what we find of value and wish to share with our fellows. Our art and our definitions of beauty reflect our human nature and the multiplicity of our creative efforts.

In the end, because of our individuality and our varied histories and traditions, our debates will always be inconclusive. If we are wise, we will look and listen with an open spirit, and sometimes with a wry smile, always celebrating the diversity of human imaginings and achievements.

David Howard, Church Stretton, Shropshire

Next Question of the Month

The next question is: What’s The More Important: Freedom, Justice, Happiness, Truth? Please give and justify your rankings in less than 400 words. The prize is a semi-random book from our book mountain. Subject lines should be marked ‘Question of the Month’, and must be received by 11th August. If you want a chance of getting a book, please include your physical address. Submission is permission to reproduce your answer physically and electronically.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.1: What Is Beauty, What Is Art?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 86949

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

8.1.1 What Is Beauty?

The term “beauty” is customarily associated with aesthetic experience and typically refers to an essential quality of something that arouses some type of reaction in the human observer — for example, pleasure, calm, elevation, or delight. Beauty is attributed to both natural phenomena (such as sunsets or mountains) as well as to human-made artifacts (such as paintings or symphonies). There have been numerous theories over the millennia of Western philosophical thought that attempt to define “beauty,” by either:

- attributing it to “essential qualities” within the natural phenomenon or artifact, or

- regarding it purely in terms of the experience of beauty by the human subject.

The former approach considers beauty objectively, as something that exists in its own right, intrinsically, in the “something” or art object, independently of being experienced. The latter strategy regards beauty subjectively, as something that occurs in the mind of the subject who perceives beauty — beauty is in the eyes of the beholder . In Aesthetics, objectivity versus subjectivity has been a matter of serious philosophical dispute not only with regard to the nature of beauty but it also comes up in connection with judging the relative merits of pieces of art, as we will see in the the topic on aesthetic judgement. Here we ask whether beauty itself exists in the object (the natural phenomenon or the artifact) or purely within the subjective experience of the object.

Objectivist Views

Some examples:

- In the view of Plato (427-347 BCE) , beauty resides in his domain of the Forms. Beauty is objective, it is not about the experience of the observer. Plato’s conception of “objectivity” is atypical. The world of Forms is “ideal” rather than material; Forms, and beauty, are non-physical ideas for Plato. Yet beauty is objective in that it is not a feature of the observer’s experience.

- Aristotle (384-322 BCE) too held an objective view of beauty, but one vastly different from Plato’s. Beauty resides in what is being observed and is defined by characteristics of the art object, such as symmetry, order, balance, and proportion. Such criteria hold, whether the object is natural or man-made.

While they hold differing conceptions of what “beauty” is, Plato and Aristotle do agree that it is a feature of the “object,” and not something in the mind of the beholder.

Subjectivist Views

- David Hume (1711-1776) argued that beauty does not lie in “things” but is entirely subjective, a matter of feelings and emotion. Beauty is in the mind of of the person beholding the object, and what is beautiful to one observer may not be so to another.

- Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) believed that aesthetic judgement is based on feelings, in particular, the feeling of pleasure. What brings pleasure is a matter of personal taste. Such judgements involve neither cognition nor logic, and are therefore subjective. Beauty is defined by judgement processes of the mind, it is not a feature of the thing judged to be beautiful.

A complication emerges with a purely subjective account of beauty, because the idea of beauty becomes meaningless if everything is merely a matter of taste or personal preference. If beauty is purely in the eye of the beholder, the idea of beauty has no value as an ideal comparable to truth or goodness. Controversies arise over matters of taste; people can have strong opinions regarding whether or not beauty is present, suggesting that perhaps there are some standards. Both Hume and Kant were aware of this problem. Each, in his own way, attempted to diminish it by lending a tone of objectivity to the idea of beauty.

- Hume proposed that great examples of good taste emerge, as do respected authorities. Such experts tend to have wide experience and knowledge, and subjective opinions among them tend to agree.

- Kant too was aware that subjective judgments of taste in art engender debates that do actually lead to agreement on questions of beauty. This is possible if aesthetic experience occurs with a disinterested attitude, unobstructed by personal feelings and preferences. We will return to Kant’s notion of “disinterest” in the section on “Aesthetic Experience and Judgement.”

A supplemental resource (bottom of page) provides further details on the subjectivity and objectivity of beauty.

The following TED talk by philosopher Denis Dutton (1944-2010) offers an unusual account of beauty, based on evolution. He argues that the concept of beauty evolved deep within our psyches for reasons related to survival.

A Darwinian theory of beauty . [CC-BY-NC-ND] Enjoy this 15-minute video!

Denis Dutton’s lecture ends with these words:

“Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? No, it’s deep in our minds. It’s a gift handed down from the intelligent skills and rich emotional lives of our most ancient ancestors. Our powerful reaction to images, to the expression of emotion in art, to the beauty of music, to the night sky, will be with us and our descendants for as long as the human race exists.”

Do you think a case can be made, based on Dutton’s Darwinian perspective, that the nature of beauty is objective? or subjective? Explain your position based on points made in the lecture, in 100-150 words.

Note: Submit your response to the appropriate Assignments folder.

8.1.2 Is “This” Art?

The question “what is art?” has engendered a myriad of diverse responses. At one end of the spectrum, aestheticians propose theories that demarcate the realm of art by excluding pieces that do not meet certain criteria; for example, some views stipulate a particular characteristic to be an essential element of anything considered to be art, or that conventions of art-world society apply to what can be considered art. On the other hand, there are views on aesthetics that claim that art cannot be defined, it defies definition — we just know it when we see it.

Do works of art have an essential characteristic?

Some main theories of art claim that works of art possess a defining and essential characteristic. As we will see in the section on aesthetic judgement, these same defining characteristics serve also as a critical factor for evaluating the merit of art objects. These are some examples of theories that define art in terms of an essential characteristic:

Representationalism: A work of art presents a reproduction, or imitation of something else that is real. (With Plato’s theory of Forms, art is representational; it is an approximation, though, and never a perfect one, of an ideal.) Representationalism is also referred to as “imitation.”

Formalism : Art is defined by exemplary arrangement of its elements. In the case of paintings, for example, this would involves effective use of components such as lines, shapes, perspective, light, colors, and symmetry. For music, a comparable but different set of elements would create form.

Functionalism: Art must serve a purpose. While functionalism is often taken to refer to practical purposes, some functionalist theories maintain that experiential purposes, such as conveying feeling, fulfill the requirement of functionality.

Emotionalism: Art must effectively evoke feeling or understanding in the subject viewing the art. (Some theorists regard the criterion of evoking emotion as a form a functionalism – it is art’s purpose.)

An objection to “essentialist” definitions of art is that not everything that embodies one of these characteristics is art. Seeing the essential characteristic as “necessary” rather than “sufficient,” helps to a certain extent. For example:

“ If this evokes emotion, then it is art” denotes sufficiency – a child’s tantrum might be art.

“ If this is art, then it is evokes emotion.” denotes necessity – emotion is a necessary component but not sufficient to make something “art.”

This reasoning helps resolve one objection to essentialist theories, but there is another flavor of objection to essentialism. Something besides one essential feature seems to be required to define art; it is not a simple matter. The fact that essential criteria do not necessarily exclude one another helps; some art embodies several of the features. However, the true usefulness of these essential features may be as judgment criteria, rather than defining factors.

Does art defy definition?

The family-resemblance, or cluster theory of art is a reaction to perceived failures of theories of art that attempt to define art by a common property. According to the family-resemblance view, an object may be designated as “art” if it has at least some of the features or properties typically ascribed to art. There is no single common property among art objects. Works of art have a family resemblance, overlapping similarities. The family resemblance concept was originally suggested by Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) in his work Philosophical Investigati ons (1953, 1958) where he addressed the problem of attributing a common characteristic to all things that go by one name. His examples included games. There are many types of games — board games, ball games, card games, etc. “…look and see whether there is anything common to all.—For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that.” (66) Given the widely diverse array of objects accepted as works of art, it followed that merging their nature under a common definition was inadequate.

Morris Weitz (1916-1981) was an American philosopher of aesthetics. He was critical of the many theories of art that attempt to define art by finding an essential feature possessed by all works of art. Wittgenstein’s family resemblance theory supported his view regarding anti-essentialism in art. In his view, “artwork” is an open concept, and there is a non-specific set, or “cluster,” of characteristics that may apply to the concept of artwork.

Compared to theories on the nature of art that designate an essential criterion, the family-resemblance (or cluster) theory offers the possibility of being more inclusive; work rejected by other theories can be considered art by family resemblance. A criticism to the cluster or family resemblance theory is that it is ahistorical; that is, the cluster of concepts used to define art does not hold over time. In addition to discussing this criticism of cluster theory, the following journal article provides an example of present-day scholarship on aesthetics.

Contemporary Aesthetics “ The Cluster Account of Art: A Historical Dilemma”: The Cluster Account of Art: A Historical Dilemma . [CC-BY-NC-ND]

Should art meet conventional standards?

Conventionalist theories of art are grounded in fundamental principles or agreements, explicit or implicit, of the art-world society. These theories for defining art set boundaries for what should and should not be included in the realm of art. Their effect is to exclude certain kinds of work, especially those that are progressive or experimental. Conventionalist theories include:

Historical Theories of Art: In order to be considered art, a work must bear some connection to existing works of art. At any given time, the art world includes work created up to that point, and new works must be similar or related to existing work. These theories invite an objection related to how the first art work became accepted. Proponents of these theories would respond that the definition also includes the “first” art.

Institutional theories of art : Art is whatever people in the ‘art world’ say it is. Those who have spent years in professional careers studying and savoring art and its history have an eye for fine distinction (or an “ear” perhaps if we are considering music.) Such theories are regarded as arbitrary or capricious by those who view beauty as purely subjective.

Conventionalist views define explicit boundaries for art. Such theories may exclude anything not intentionally created by a human “agent.” For example, natural phenomena are not art, nor are items such as paintings created by animals. (Search online for “paintings by elephants.” for example, if you are curious; this is not a course requirement.)

A supplemental resource (bottom of page) provides further investigation of definitions of art.

Supplemental Resources

Nature of Beauty

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP). Beauty . Read Section 1 on Objectivity and Subjectivity.

Art Definition

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP). The Definition of Art .

- 8.1 What Is Beauty, What Is Art?. Authored by : Kathy Eldred. Provided by : Pima Community College. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Beauty

Introduction, anthologies and reference works.

- The Sensuous and Desire

- Beauty and Art

- Beauty and Disinterest

- Beauty and Nature

- Beauty Contested

- Beauty Experienced

- Beauty and Evaluation

- Beauty and Aesthetic Form

- Beauty and Autonomy

- Beauty and the Form of Perfection

- Aesthetic Judgement and Community

- Beauty and Truth

- Beauty and Value Theory

- Beauty and Morality

- Beauty Naturalized

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Aesthetic Hedonism

- Analytic Approaches to Aesthetics

- Analytic Approaches to Pornography and Objectification

- Analytic Philosophy of Music

- Analytic Philosophy of Photography

- Art and Emotion

- Art and Morality

- Environmental Aesthetics

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Aesthetics

- History of Aesthetics

- Immanuel Kant: Aesthetics and Teleology

- Ontology of Art

- Susanne Langer

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Alfred North Whitehead

- Feminist Aesthetics

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Beauty by Jennifer A. McMahon LAST REVIEWED: 26 April 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 31 July 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396577-0038

Philosophical interest in beauty began with the earliest recorded philosophers. Beauty was deemed to be an essential ingredient in a good life and so what it was, where it was to be found, and how it was to be included in a life were prime considerations. The way beauty has been conceived has been influenced by an author’s other philosophical commitments―metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical―and such commitments reflect the historical and cultural position of the author. For example, beauty is a manifestation of the divine on earth to which we respond with love and adoration; beauty is a harmony of the soul that we achieve through cultivating feeling in a rational and tempered way; beauty is an idea raised in us by certain objective features of the world; beauty is a sentiment that can nonetheless be cultivated to be appropriate to its object; beauty is the object of a judgement by which we exercise the social, comparative, and intersubjective elements of cognition, and so on. Such views on beauty not only reveal underlying philosophical commitments but also reflect positive contributions to understanding the nature of value and the relation between mind and world. One way to distinguish between beauty theories is according to the conception of the human being that they assume or imply, for example, where they fall on the continuum from determinism to free will, ungrounded notions of compatibilism notwithstanding. For example, theories at the latter end might carve out a sense of genuine innovation and creativity in human endeavors while at the other end of the spectrum authors may conceive of beauty as an environmental trigger for consumption, procreation, or preservation in the interests of the individual. Treating beauty experiences as in some respect intentional, characterizes beauty theory prior to the 20th century and since, mainly in historically inspired writing on beauty. However, treating beauty as affect or sensation has always had its representatives and is most visible today in evolutionary-inspired accounts of beauty (though not all evolutionary accounts fit this classification). Beauty theory falls under some combination of metaphysics, epistemology, meta-ethics, aesthetics, and psychology. Although during the 20th century beauty was more likely to be conceived as an evaluative concept for art, recent philosophical interest in beauty can again be seen to exercise arguments pertaining to metaphysics, epistemology, meta-ethics, philosophy of meaning, and language in addition to philosophy of art and environmental aesthetics. This work has been funded by an Australian Research Council Grant: DP150103143 (Taste and Community).

Anthologies on beauty that bring together writers who, while they may discuss art, do so in the main only to reveal our capacity for beauty, include the excellent selection of historical readings collected in the one-volume Hofstadter and Kuhns 1976 and the more culturally inclusive collection Cooper 1997 . Recent anthologies on beauty can take the form of a study of aesthetic value, such as in Schaper 1983 , or more specifically on the ethical dimension of aesthetic value, such as in Hagberg 2008 . Reference works in philosophical aesthetics today tend to focus on the philosophy of art and criticism. They typically include one chapter on beauty, and in this context Mothersill 2004 treats beauty as an evaluative category for art; and in keeping with this approach, Mothersill 2009 recommends a historically informed understanding of the concept beauty derived from Hegel. A recent trend toward environmental aesthetics brings us back to beauty as a property of the natural world, as in Zangwill 2003 , while McMahon 2005 responds to empirical trends by treating beauty as a value compatible with naturalization. The comprehensive entry “ Beauty ” in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics is divided into four parts. It begins with Stephen David Ross’s brief but excellent summary of the history of concepts that underpin beauty theory and philosophical aesthetics more broadly. It is followed by Nickolas Pappas’s dedicated section on classical concepts of beauty, and then Jan A. Aertsen’s section on medieval concepts of beauty. The entry concludes with Nicholas Riggle’s discussion of beauty and love, which introduces contemporary themes to the topic. Guyer 2014 analyzes historical trends in approaches to beauty theory in a way that sets up illuminating contrasts to contemporary perspectives.

“Beauty.” In Abhinavagupta–Byzantine Aesthetics . Vol. 1 of Encyclopedia of Aesthetics . 2d ed. Edited by Michael Kelly. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

In the course of setting out the historical foundations to the concept beauty, we are provided with an excellent summary of the key concepts that still dominate or underpin philosophical aesthetics, including pleasure, desire, the good, disinterest, taste, value, and love. Available at Oxford Art Online by subscription.

Cooper, David. Aesthetics: The Classic Readings . Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1997.

Introductions are provided to some of the classic readings on beauty followed by an extract from the relevant work. They are discussed in terms of their relevance to understanding art rather than value more generally.

Guyer, Paul. A History of Modern Aesthetics . 3 vols. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Guyer traces the development of key concepts in aesthetics, including beauty, within a context of broader scaled trends, such as aesthetics of truth in the ancient world, aesthetics of emotion and imagination in the 18th century, and aesthetics of meaning and significance in the 20th century.

Hagberg, Garry I., ed. Art and Ethical Criticism . Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

DOI: 10.1002/9781444302813

A series of papers on the ethical dimension of art, the authors draw out the ethical significance of a particular art/literary/musical work or art form. It is worth noting that the lead essay by Paul Guyer argues that 18th-century writers on beauty did not hold any concepts incompatible with this approach.

Hofstadter, Albert, and Richard Kuhns, eds. Philosophies of Art and Beauty: Selected Readings in Aesthetics from Plato to Heidegger . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

Well-chosen readings from classic works, with commentary provided, marred occasionally by the editors’ anachronistic emphasis on art. The readings provide a good introduction to various conceptions of beauty as a general value.

McMahon, Jennifer A. “Beauty.” In Routledge Companion to Aesthetics . 2d ed. Edited by Berys Gaut and Dominic Lopes, 307–319. London and New York: Routledge, 2005.

A historical overview drawing out the contrast between sensuous- and formal/value-oriented approaches to beauty, culminating in the contrast between Freud’s pleasure principle and the constructivist approach of cognitive science.

Mothersill, Mary. “Beauty and the Critic’s Judgment: Remapping Aesthetics.” In The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics . Edited by Peter Kivy, 152–166. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

DOI: 10.1002/9780470756645

Setting out the change in focus in philosophical aesthetics between the 19th and 20th century, Mothersill then proceeds to analyze beauty with a view to its significance for understanding aesthetic value in relation to art.

Mothersill, Mary. “Beauty.” In A Companion to Aesthetics . 2d ed. Edited by Stephen Davies, Kathleen Higgins, Robert Hopkins, Robert Stecker, and David E. Cooper, 166–171. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Mothersill considers the contributions made by key historical figures before settling on Hegel’s historicism as providing the most helpful insight for the present context. Available online.

Schaper, Eva, ed. Pleasure, Preference and Value . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

A series of essays by prominent philosophers on the nature of aesthetic value, which are very useful as an introduction to the study of value theory, including essays on taste, pleasure, aesthetic interest, aesthetic realism, and aesthetic objectivity.

Zangwill, Nick. “Beauty.” In The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics . Edited by Jerrold Levinson, 325–343. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

An introduction to the tradition of analytic approaches to value theory, beauty is analyzed into its components and relationships, and its status considered in terms of subjectivity and objectivity.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Philosophy »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- A Priori Knowledge

- Abduction and Explanatory Reasoning

- Abstract Objects

- Addams, Jane

- Adorno, Theodor

- Aesthetics, Analytic Approaches to

- Aesthetics, Continental

- Aesthetics, Environmental

- Aesthetics, History of

- African Philosophy, Contemporary

- Alexander, Samuel

- Analytic/Synthetic Distinction

- Anarchism, Philosophical

- Animal Rights

- Anscombe, G. E. M.

- Anthropic Principle, The

- Anti-Natalism

- Applied Ethics

- Aquinas, Thomas

- Argument Mapping

- Art and Knowledge

- Astell, Mary

- Aurelius, Marcus

- Austin, J. L.

- Bacon, Francis

- Bayesianism

- Bergson, Henri

- Berkeley, George

- Biology, Philosophy of

- Bolzano, Bernard

- Boredom, Philosophy of

- British Idealism

- Buber, Martin

- Buddhist Philosophy

- Burge, Tyler

- Business Ethics

- Camus, Albert

- Canterbury, Anselm of

- Carnap, Rudolf

- Cavendish, Margaret

- Chemistry, Philosophy of

- Childhood, Philosophy of

- Chinese Philosophy

- Cognitive Ability

- Cognitive Phenomenology

- Cognitive Science, Philosophy of

- Coherentism

- Communitarianism

- Computational Science

- Computer Science, Philosophy of

- Computer Simulations

- Comte, Auguste

- Conceptual Role Semantics

- Conditionals