- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

- 4 minute read

- 129.7K views

Table of Contents

A research paper presentation is often used at conferences and in other settings where you have an opportunity to share your research, and get feedback from your colleagues. Although it may seem as simple as summarizing your research and sharing your knowledge, successful research paper PowerPoint presentation examples show us that there’s a little bit more than that involved.

In this article, we’ll highlight how to make a PowerPoint presentation from a research paper, and what to include (as well as what NOT to include). We’ll also touch on how to present a research paper at a conference.

Purpose of a Research Paper Presentation

The purpose of presenting your paper at a conference or forum is different from the purpose of conducting your research and writing up your paper. In this setting, you want to highlight your work instead of including every detail of your research. Likewise, a presentation is an excellent opportunity to get direct feedback from your colleagues in the field. But, perhaps the main reason for presenting your research is to spark interest in your work, and entice the audience to read your research paper.

So, yes, your presentation should summarize your work, but it needs to do so in a way that encourages your audience to seek out your work, and share their interest in your work with others. It’s not enough just to present your research dryly, to get information out there. More important is to encourage engagement with you, your research, and your work.

Tips for Creating Your Research Paper Presentation

In addition to basic PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, think about the following when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Know your audience : First and foremost, who are you presenting to? Students? Experts in your field? Potential funders? Non-experts? The truth is that your audience will probably have a bit of a mix of all of the above. So, make sure you keep that in mind as you prepare your presentation.

Know more about: Discover the Target Audience .

- Your audience is human : In other words, they may be tired, they might be wondering why they’re there, and they will, at some point, be tuning out. So, take steps to help them stay interested in your presentation. You can do that by utilizing effective visuals, summarize your conclusions early, and keep your research easy to understand.

- Running outline : It’s not IF your audience will drift off, or get lost…it’s WHEN. Keep a running outline, either within the presentation or via a handout. Use visual and verbal clues to highlight where you are in the presentation.

- Where does your research fit in? You should know of work related to your research, but you don’t have to cite every example. In addition, keep references in your presentation to the end, or in the handout. Your audience is there to hear about your work.

- Plan B : Anticipate possible questions for your presentation, and prepare slides that answer those specific questions in more detail, but have them at the END of your presentation. You can then jump to them, IF needed.

What Makes a PowerPoint Presentation Effective?

You’ve probably attended a presentation where the presenter reads off of their PowerPoint outline, word for word. Or where the presentation is busy, disorganized, or includes too much information. Here are some simple tips for creating an effective PowerPoint Presentation.

- Less is more: You want to give enough information to make your audience want to read your paper. So include details, but not too many, and avoid too many formulas and technical jargon.

- Clean and professional : Avoid excessive colors, distracting backgrounds, font changes, animations, and too many words. Instead of whole paragraphs, bullet points with just a few words to summarize and highlight are best.

- Know your real-estate : Each slide has a limited amount of space. Use it wisely. Typically one, no more than two points per slide. Balance each slide visually. Utilize illustrations when needed; not extraneously.

- Keep things visual : Remember, a PowerPoint presentation is a powerful tool to present things visually. Use visual graphs over tables and scientific illustrations over long text. Keep your visuals clean and professional, just like any text you include in your presentation.

Know more about our Scientific Illustrations Services .

Another key to an effective presentation is to practice, practice, and then practice some more. When you’re done with your PowerPoint, go through it with friends and colleagues to see if you need to add (or delete excessive) information. Double and triple check for typos and errors. Know the presentation inside and out, so when you’re in front of your audience, you’ll feel confident and comfortable.

How to Present a Research Paper

If your PowerPoint presentation is solid, and you’ve practiced your presentation, that’s half the battle. Follow the basic advice to keep your audience engaged and interested by making eye contact, encouraging questions, and presenting your information with enthusiasm.

We encourage you to read our articles on how to present a scientific journal article and tips on giving good scientific presentations .

Language Editing Plus

Improve the flow and writing of your research paper with Language Editing Plus. This service includes unlimited editing, manuscript formatting for the journal of your choice, reference check and even a customized cover letter. Learn more here , and get started today!

- Manuscript Preparation

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

You may also like.

What is a Good H-index?

What is a Corresponding Author?

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

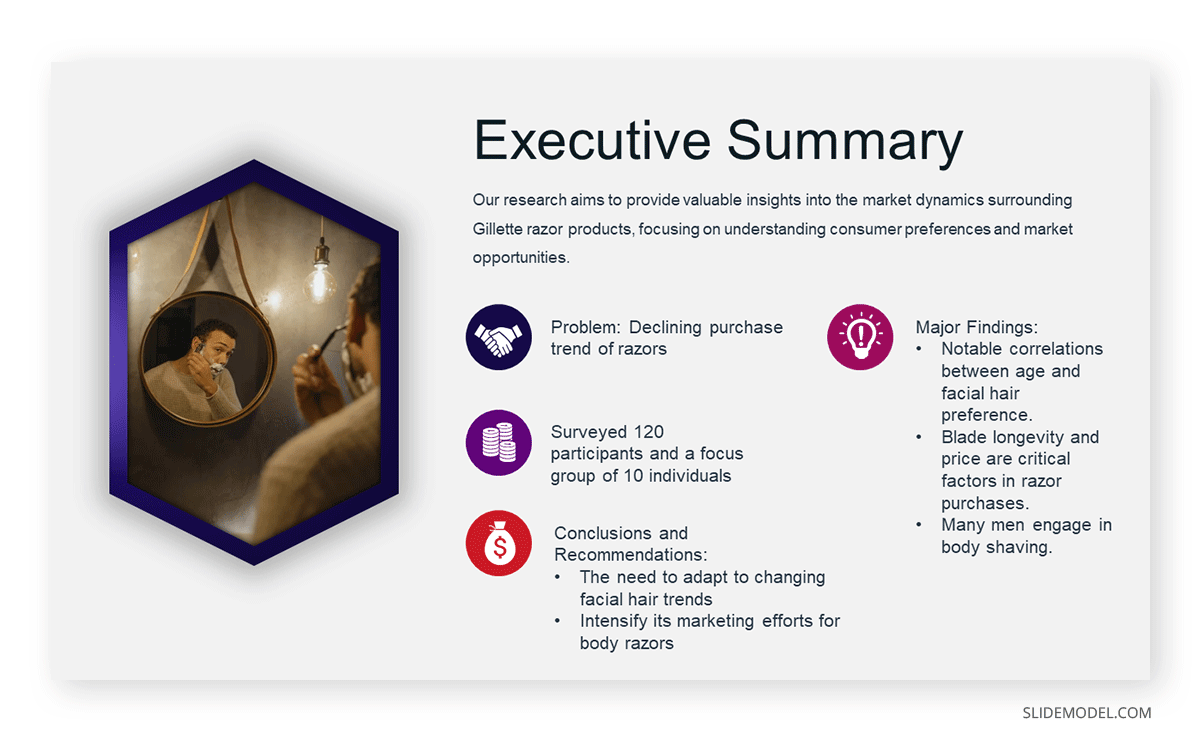

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

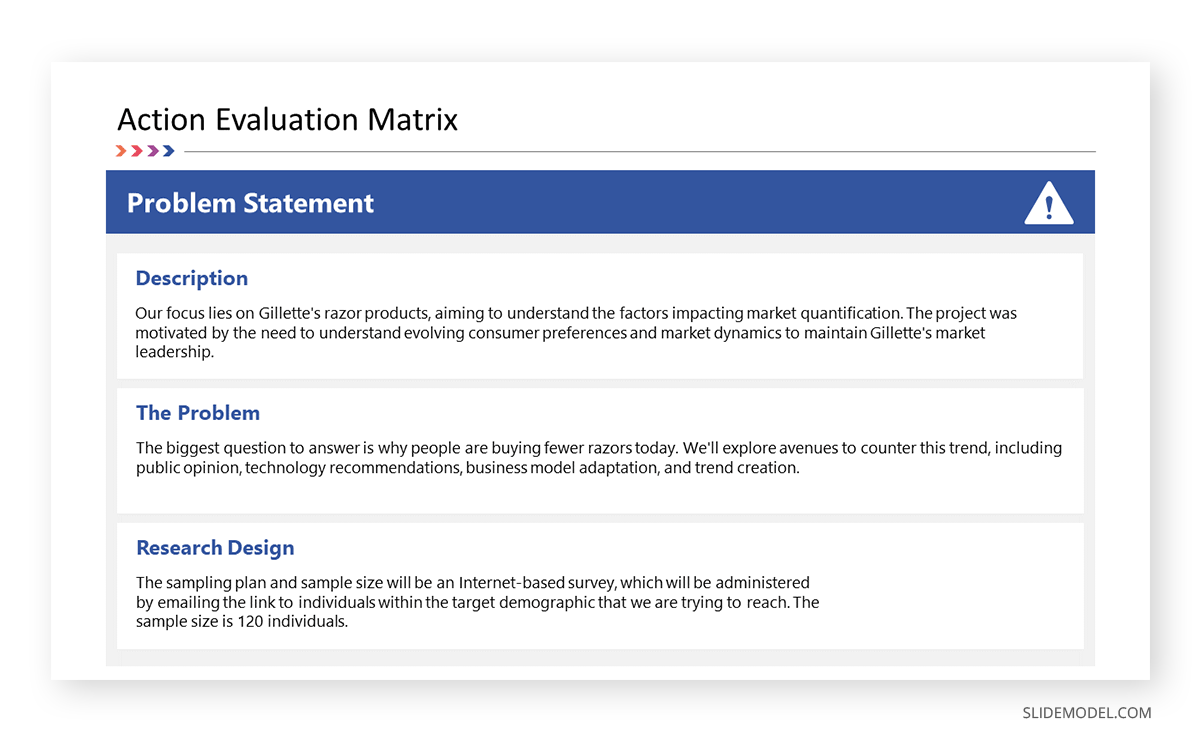

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

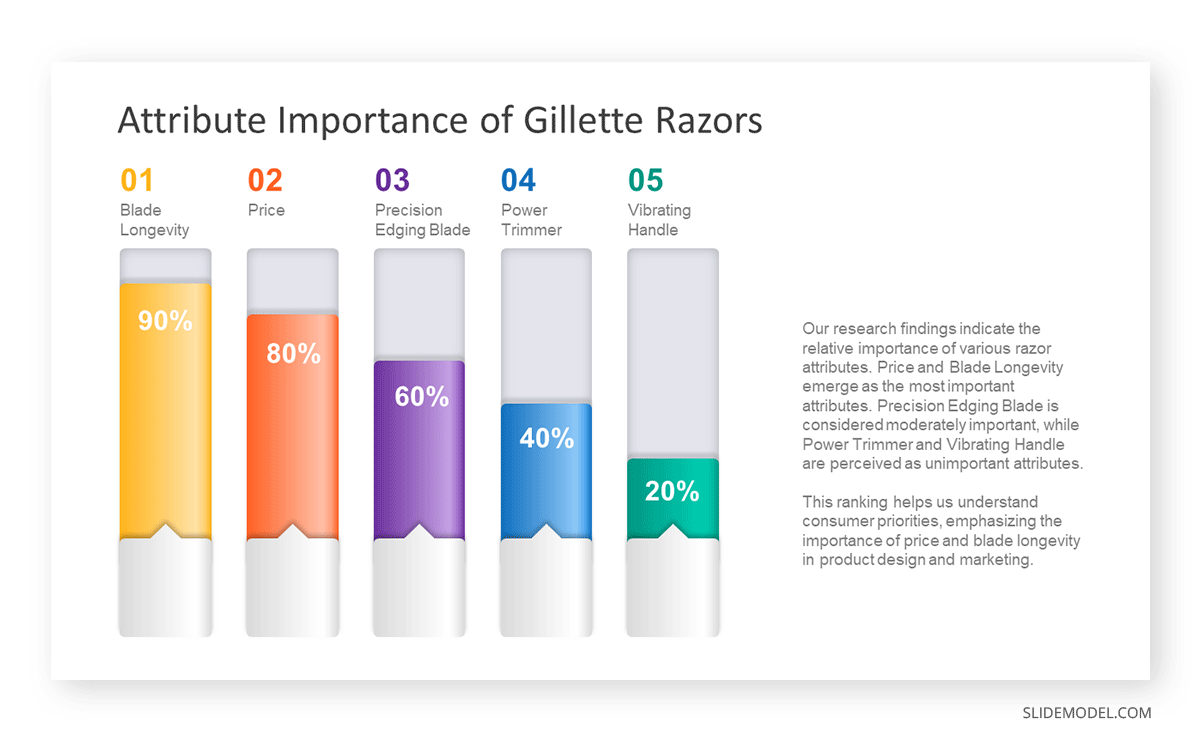

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

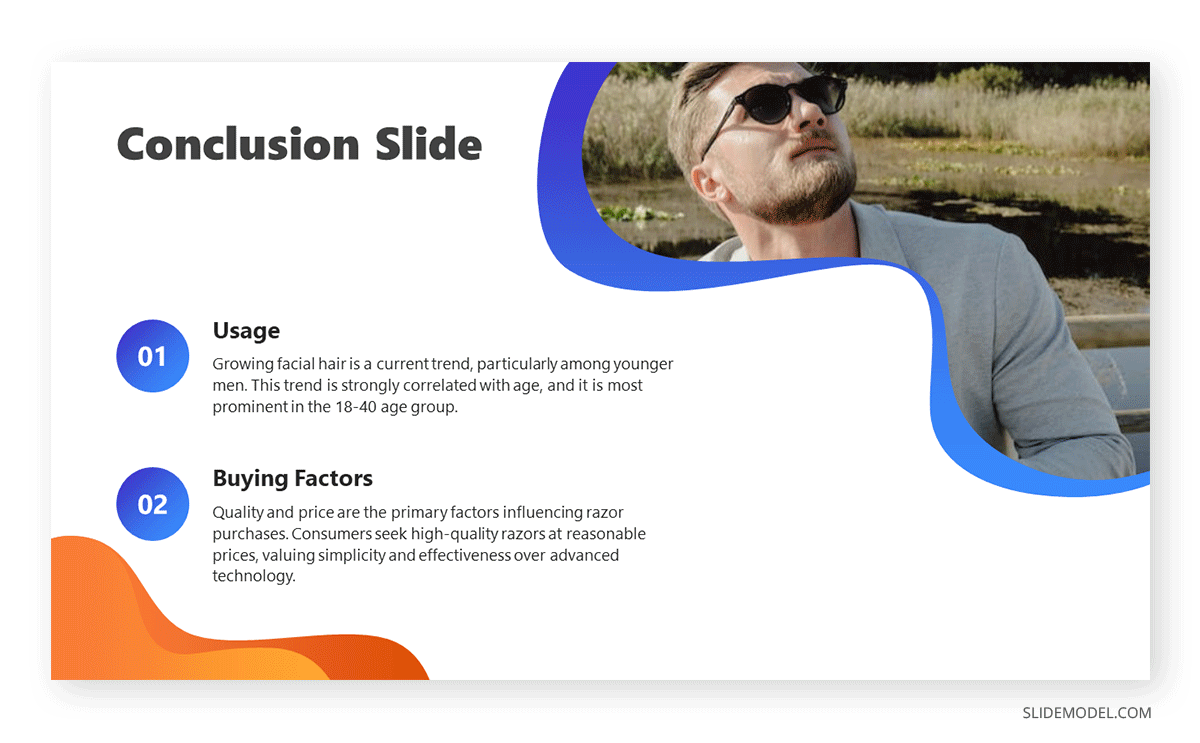

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

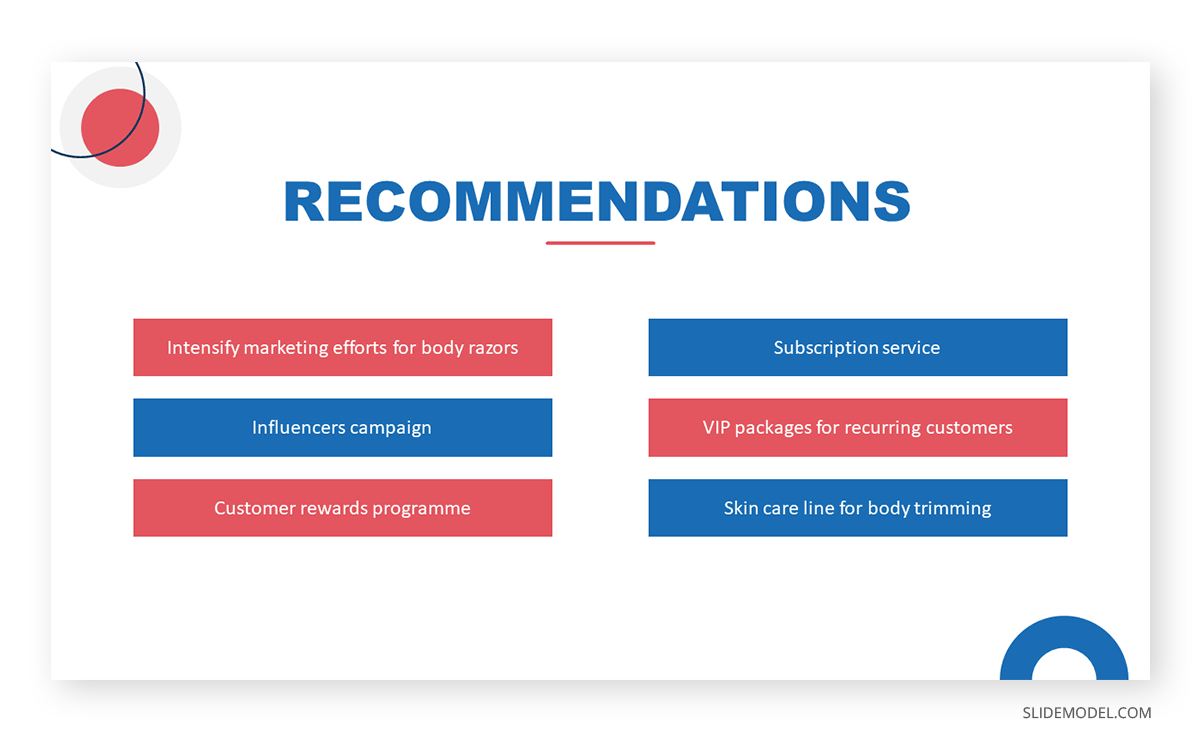

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation.

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image.” Website Name, Day Mo. Year, URL. Accessed Day Mo. Year.

Work cited page

A work cited page or reference list should follow after the last slide of your presentation. The list should be alphabetized by the author’s last name and initials followed by the year of publication, the title of the book or article, the place of publication, and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. New York, NY: ABC Publications.

When citing a document from a website, add the source URL after the title of the book or article instead of the place of publication and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. Retrieved from https://www.smith.com/climate-change-and-biodiversity.

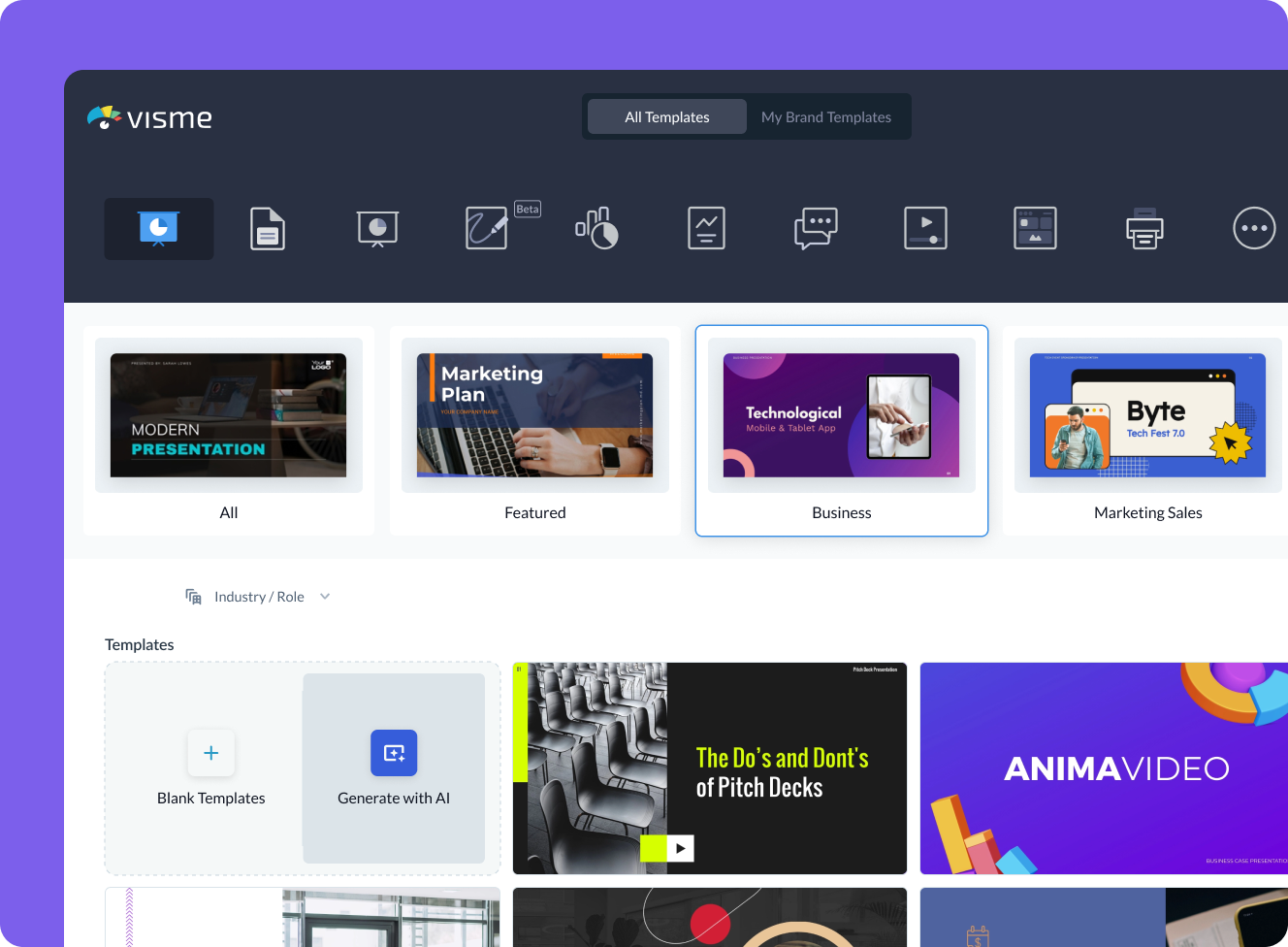

1. Research Project Presentation PowerPoint Template

A slide deck containing 18 different slides intended to take off the weight of how to make a research presentation. With tons of visual aids, presenters can reference existing research on similar projects to this one – or link another research presentation example – provide an accurate data analysis, disclose the methodology used, and much more.

Use This Template

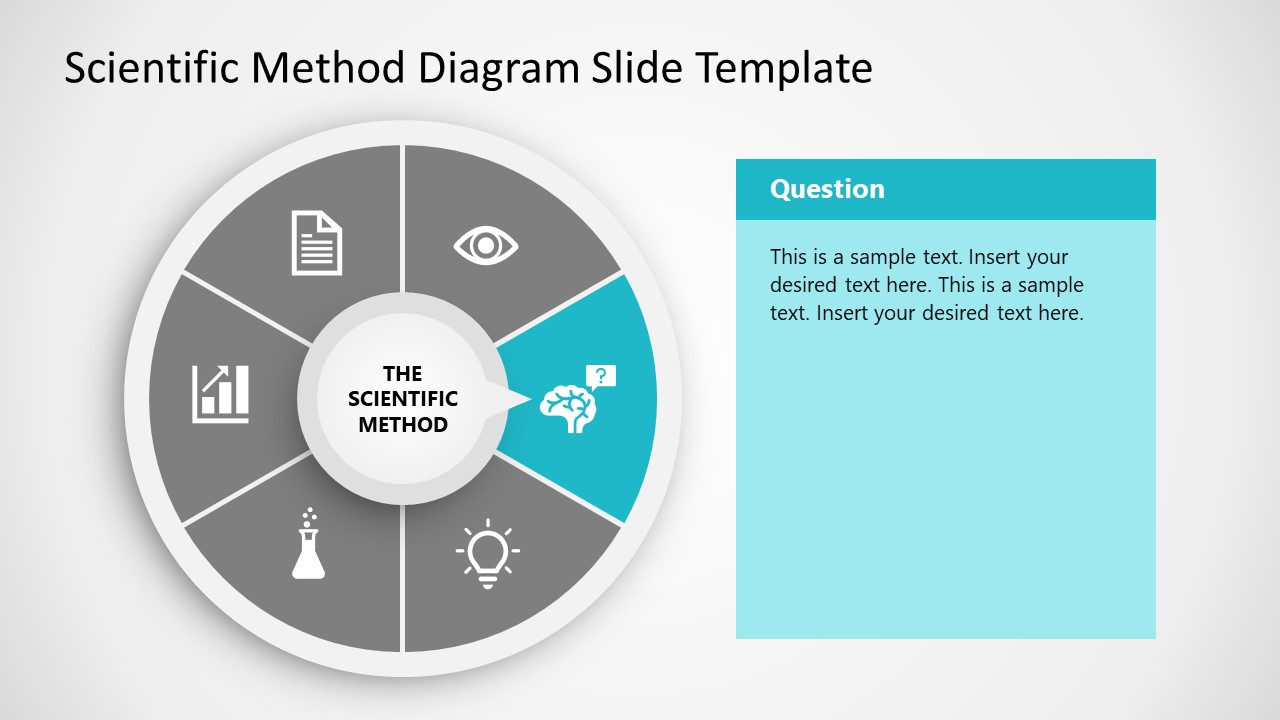

2. Research Presentation Scientific Method Diagram PowerPoint Template

Whenever you intend to raise questions, expose the methodology you used for your research, or even suggest a scientific method approach for future analysis, this circular wheel diagram is a perfect fit for any presentation study.

Customize all of its elements to suit the demands of your presentation in just minutes.

3. Thesis Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

If your research presentation project belongs to academia, then this is the slide deck to pair that presentation. With a formal aesthetic and minimalistic style, this research presentation template focuses only on exposing your information as clearly as possible.

Use its included bar charts and graphs to introduce data, change the background of each slide to suit the topic of your presentation, and customize each of its elements to meet the requirements of your project with ease.

4. Animated Research Cards PowerPoint Template

Visualize ideas and their connection points with the help of this research card template for PowerPoint. This slide deck, for example, can help speakers talk about alternative concepts to what they are currently managing and its possible outcomes, among different other usages this versatile PPT template has. Zoom Animation effects make a smooth transition between cards (or ideas).

5. Research Presentation Slide Deck for PowerPoint

With a distinctive professional style, this research presentation PPT template helps business professionals and academics alike to introduce the findings of their work to team members or investors.

By accessing this template, you get the following slides:

- Introduction

- Problem Statement

- Research Questions

- Conceptual Research Framework (Concepts, Theories, Actors, & Constructs)

- Study design and methods

- Population & Sampling

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

Check it out today and craft a powerful research presentation out of it!

A successful research presentation in business is not just about presenting data; it’s about persuasion to take meaningful action. It’s the bridge that connects your research efforts to the strategic initiatives of your organization. To embark on this journey successfully, planning your presentation thoroughly is paramount, from designing your PowerPoint to the delivery.

Take a look and get inspiration from the sample research presentation slides above, put our tips to heart, and transform your research findings into a compelling call to action.

Like this article? Please share

Academics, Presentation Approaches, Research & Development Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Presentation Ideas • June 6th, 2024

10+ Outstanding PowerPoint Presentation Examples and Templates

Looking for inspiration before approaching your next slide design? If so, take a look at our selection of PowerPoint presentation examples.

Filed under Design • May 22nd, 2024

Exploring the 12 Different Types of Slides in PowerPoint

Become a better presenter by harnessing the power of the 12 different types of slides in presentation design.

Filed under Design • March 27th, 2024

How to Make a Presentation Graph

Detailed step-by-step instructions to master the art of how to make a presentation graph in PowerPoint and Google Slides. Check it out!

Leave a Reply

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

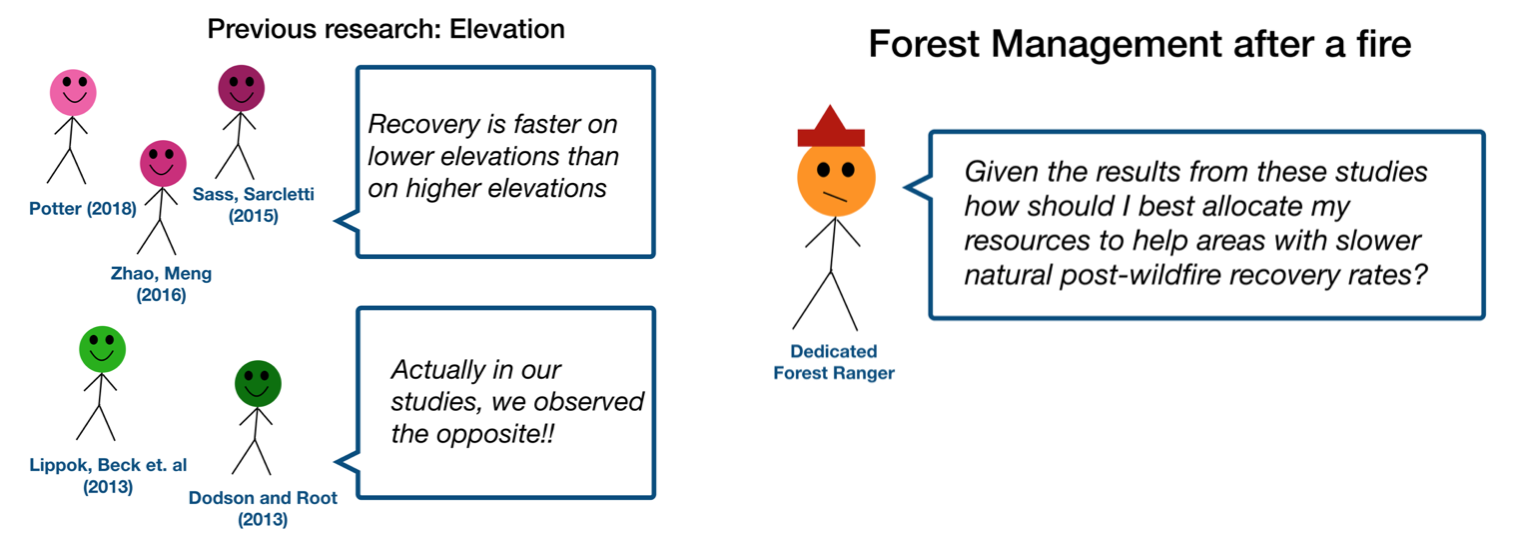

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

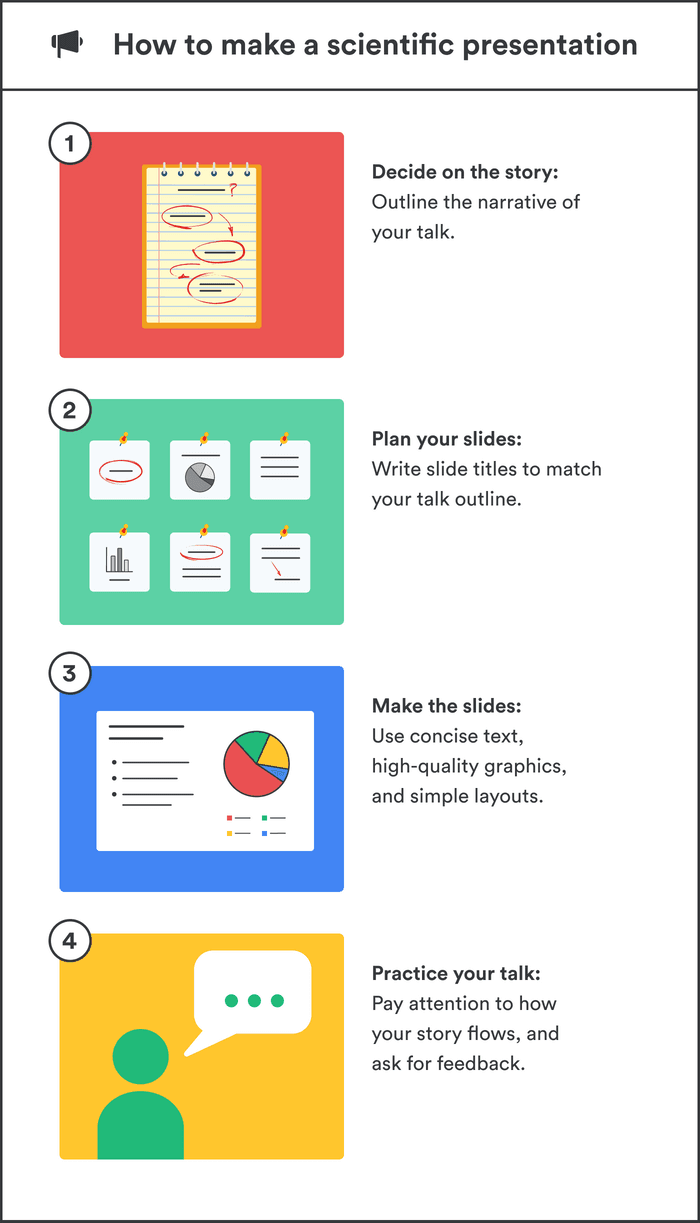

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

Introduction | Introduction - main idea behind all studies |

Methods | Methods of study 1 |

Results | Results of study 1 |

Summary (take-home message ) of study 1 | |

Transition to study 2 (can be a visual of your main idea that return to) | |

Brief introduction for study 2 | |

Methods of study 2 | |

Results of study 2 | |

Summary of study 2 | |

Transition to study 3 | |

Repeat format until done | |

Summary | Summary of all studies (return to your main idea) |

Conclusion | Conclusion |

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

6 Tips For Giving a Fabulous Academic Presentation

6-tips-for-giving-a-fabulous-academic-presentation.

Tanya Golash-Boza, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of California

January 11, 2022

One of the easiest ways to stand out at an academic conference is to give a fantastic presentation.

In this post, I will discuss a few simple techniques that can make your presentation stand out. Although, it does take time to make a good presentation, it is well worth the investment.

Tip #1: Use PowerPoint Judiciously

Images are powerful. Research shows that images help with memory and learning. Use this to your advantage by finding and using images that help you make your point. One trick I have learned is that you can use images that have blank space in them and you can put words in those images.

Here is one such example from a presentation I gave about immigration law enforcement.

PowerPoint is a great tool, so long as you use it effectively. Generally, this means using lots of visuals and relatively few words. Never use less than 24-point font. And, please, never put your presentation on the slides and read from the slides.

Tip #2: There is a formula to academic presentations. Use it.

Once you have become an expert at giving fabulous presentations, you can deviate from the formula. However, if you are new to presenting, you might want to follow it. This will vary slightly by field, however, I will give an example from my field – sociology – to give you an idea as to what the format should look like:

- Introduction/Overview/Hook

- Theoretical Framework/Research Question

- Methodology/Case Selection

- Background/Literature Review

- Discussion of Data/Results

Tip #3: The audience wants to hear about your research. Tell them.

One of the most common mistakes I see in people giving presentations is that they present only information I already know. This usually happens when they spend nearly all of the presentation going over the existing literature and giving background information on their particular case. You need only to discuss the literature with which you are directly engaging and contributing. Your background information should only include what is absolutely necessary. If you are giving a 15-minute presentation, by the 6 th minute, you need to be discussing your data or case study. At conferences, people are there to learn about your new and exciting research, not to hear a summary of old work.

Tip #4: Practice. Practice. Practice.

You should always practice your presentation in full before you deliver it. You might feel silly delivering your presentation to your cat or your toddler, but you need to do it and do it again. You need to practice to ensure that your presentation fits within the time parameters. Practicing also makes it flow better. You can’t practice too many times.

Tip #5: Keep To Your Time Limit

If you have ten minutes to present, prepare ten minutes of material. No more. Even if you only have seven minutes, you need to finish within the allotted time. If you write your presentation out, a general rule of thumb is two minutes per typed, double-spaced page. For a fifteen-minute talk, you should have no more than 7 double-spaced pages of material.

Tip #6: Don’t Read Your Presentation

Yes, I know that in some fields reading is the norm. But, can you honestly say that you find yourself engaged when listening to someone read their conference presentation? If you absolutely must read, I suggest you read in such a way that no one in the audience can tell you are reading. I have seen people do this successfully, and you can do it too if you write in a conversational tone, practice several times, and read your paper with emotion, conviction, and variation in tone.

What tips do you have for presenters? What is one of the best presentations you have seen? What made it so fantastic? Let us know in the comments below.

Want to learn more about the publishing process? The Wiley Researcher Academy is an online author training program designed to help researchers develop the skills and knowledge needed to be able to publish successfully. Learn more about Wiley Researcher Academy .

Image credit: Tanya Golash-Boza

Read the Mandarin version here .

Watch our Webinar to help you get published

Please enter your Email Address

Please enter valid email address

Please Enter your First Name

Please enter your Last Name

Please enter your Questions or Comments.

Please enter the Privacy

Please enter the Terms & Conditions

How research content supports academic integrity

Finding time to publish as a medical student: 6 tips for Success

Software to Improve Reliability of Research Image Data: Wiley, Lumina, and Researchers at Harvard Medical School Work Together on Solutions

Driving Research Outcomes: Wiley Partners with CiteAb

ISBN, ISSN, DOI: what they are and how to find them

Image Collections for Medical Practitioners with TDS Health

How do you Discover Content?

Writing for Publication for Nurses (Mandarin Edition)

Get Published - Your How to Webinar

Finding time to publish as a medical student: 6 tips for success

Related articles.

Learn how Wiley partners with plagiarism detection services to support academic integrity around the world

Medical student Nicole Foley shares her top tips for writing and getting your work published.

Wiley and Lumina are working together to support the efforts of researchers at Harvard Medical School to develop and test new machine learning tools and artificial intelligence (AI) software that can

Learn more about our relationship with a company that helps scientists identify the right products to use in their research

What is ISBN? ISSN? DOI? Learn about some of the unique identifiers for book and journal content.

Learn how medical practitioners can easily access and search visual assets from our article portfolio

Explore free-to-use services that can help you discover new content

Watch this webinar to help you learn how to get published.

How to Easily Access the Most Relevant Research: A Q&A With the Creator of Scitrus

Atypon launches Scitrus, a personalized web app that allows users to create a customized feed of the latest research.

Effectively and Efficiently Creating your Paper

FOR INDIVIDUALS

FOR INSTITUTIONS & BUSINESSES

WILEY NETWORK

ABOUT WILEY

Corporate Responsibility

Corporate Governance

Leadership Team

Cookie Preferences

Copyright @ 2000-2024 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., or related companies. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial technologies or similar technologies.

Rights & Permissions

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Presentations

How to Write a Seminar Paper

Last Updated: October 17, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 16 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 625,834 times.

A seminar paper is a work of original research that presents a specific thesis and is presented to a group of interested peers, usually in an academic setting. For example, it might serve as your cumulative assignment in a university course. Although seminar papers have specific purposes and guidelines in some places, such as law school, the general process and format is the same. The steps below will guide you through the research and writing process of how to write a seminar paper and provide tips for developing a well-received paper.

Getting Started

- an argument that makes an original contribution to the existing scholarship on your subject

- extensive research that supports your argument

- extensive footnotes or endnotes (depending on the documentation style you are using)

- Make sure that you understand how to cite your sources for the paper and how to use the documentation style your professor prefers, such as APA , MLA , or Chicago Style .

- Don’t feel bad if you have questions. It is better to ask and make sure that you understand than to do the assignment wrong and get a bad grade.

- Since it's best to break down a seminar paper into individual steps, creating a schedule is a good idea. You can adjust your schedule as needed.

- Do not attempt to research and write a seminar in just a few days. This type of paper requires extensive research, so you will need to plan ahead. Get started as early as possible. [3] X Research source

- Listing List all of the ideas that you have for your essay (good or bad) and then look over the list you have made and group similar ideas together. Expand those lists by adding more ideas or by using another prewriting activity. [5] X Research source

- Freewriting Write nonstop for about 10 minutes. Write whatever comes to mind and don’t edit yourself. When you are done, review what you have written and highlight or underline the most useful information. Repeat the freewriting exercise using the passages you underlined as a starting point. You can repeat this exercise multiple times to continue to refine and develop your ideas. [6] X Research source

- Clustering Write a brief explanation (phrase or short sentence) of the subject of your seminar paper on the center of a piece of paper and circle it. Then draw three or more lines extending from the circle. Write a corresponding idea at the end of each of these lines. Continue developing your cluster until you have explored as many connections as you can. [7] X Research source

- Questioning On a piece of paper, write out “Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?” Space the questions about two or three lines apart on the paper so that you can write your answers on these lines. Respond to each question in as much detail as you can. [8] X Research source

- For example, if you wanted to know more about the uses of religious relics in medieval England, you might start with something like “How were relics used in medieval England?” The information that you gather on this subject might lead you to develop a thesis about the role or importance of relics in medieval England.

- Keep your research question simple and focused. Use your research question to narrow your research. Once you start to gather information, it's okay to revise or tweak your research question to match the information you find. Similarly, you can always narrow your question a bit if you are turning up too much information.

Conducting Research

- Use your library’s databases, such as EBSCO or JSTOR, rather than a general internet search. University libraries subscribe to many databases. These databases provide you with free access to articles and other resources that you cannot usually gain access to by using a search engine. If you don't have access to these databases, you can try Google Scholar.

- Publication's credentials Consider the type of source, such as a peer-reviewed journal or book. Look for sources that are academically based and accepted by the research community. Additionally, your sources should be unbiased.

- Author's credentials Choose sources that include an author’s name and that provide credentials for that author. The credentials should indicate something about why this person is qualified to speak as an authority on the subject. For example, an article about a medical condition will be more trustworthy if the author is a medical doctor. If you find a source where no author is listed or the author does not have any credentials, then this source may not be trustworthy. [12] X Research source

- Citations Think about whether or not this author has adequately researched the topic. Check the author’s bibliography or works cited page. If the author has provided few or no sources, then this source may not be trustworthy. [13] X Research source

- Bias Think about whether or not this author has presented an objective, well-reasoned account of the topic. How often does the tone indicate a strong preference for one side of the argument? How often does the argument dismiss or disregard the opposition’s concerns or valid arguments? If these are regular occurrences in the source, then it may not be a good choice. [14] X Research source

- Publication date Think about whether or not this source presents the most up to date information on the subject. Noting the publication date is especially important for scientific subjects, since new technologies and techniques have made some earlier findings irrelevant. [15] X Research source

- Information provided in the source If you are still questioning the trustworthiness of this source, cross check some of the information provided against a trustworthy source. If the information that this author presents contradicts one of your trustworthy sources, then it might not be a good source to use in your paper.

- Give yourself plenty of time to read your sources and work to understand what they are saying. Ask your professor for clarification if something is unclear to you.

- Consider if it's easier for you to read and annotate your sources digitally or if you'd prefer to print them out and annotate by hand.

- Be careful to properly cite your sources when taking notes. Even accidental plagiarism may result in a failing grade on a paper.

Drafting Your Paper

- Make sure that your thesis presents an original point of view. Since seminar papers are advanced writing projects, be certain that your thesis presents a perspective that is advanced and original. [18] X Research source

- For example, if you conducted your research on the uses of relics in medieval England, your thesis might be, “Medieval English religious relics were often used in ways that are more pagan than Christian.”

- Organize your outline by essay part and then break those parts into subsections. For example, part 1 might be your introduction, which could then be broken into three sub-parts: a)opening sentence, b)context/background information c)thesis statement.

- For example, in a paper about medieval relics, you might open with a surprising example of how relics were used or a vivid description of an unusual relic.

- Keep in mind that your introduction should identify the main idea of your seminar paper and act as a preview to the rest of your paper.

- For example, in a paper about relics in medieval England, you might want to offer your readers examples of the types of relics and how they were used. What purpose did they serve? Where were they kept? Who was allowed to have relics? Why did people value relics?

- Keep in mind that your background information should be used to help your readers understand your point of view.

- Remember to use topic sentences to structure your paragraphs. Provide a claim at the beginning of each paragraph. Then, support your claim with at least one example from one of your sources. Remember to discuss each piece of evidence in detail so that your readers will understand the point that you are trying to make.

- For example, in a paper on medieval relics, you might include a heading titled “Uses of Relics” and subheadings titled “Religious Uses”, “Domestic Uses”, “Medical Uses”, etc.

- Synthesize what you have discussed . Put everything together for your readers and explain what other lessons might be gained from your argument. How might this discussion change the way others view your subject?

- Explain why your topic matters . Help your readers to see why this topic deserve their attention. How does this topic affect your readers? What are the broader implications of this topic? Why does your topic matter?

- Return to your opening discussion. If you offered an anecdote or a quote early in your paper, it might be helpful to revisit that opening discussion and explore how the information you have gathered implicates that discussion.

- Ask your professor what documentation style he or she prefers that you use if you are not sure.

- Visit your school’s writing center for additional help with your works cited page and in-text citations.

Revising Your Paper

- What is your main point? How might you clarify your main point?

- Who is your audience? Have you considered their needs and expectations?

- What is your purpose? Have you accomplished your purpose with this paper?

- How effective is your evidence? How might your strengthen your evidence?

- Does every part of your paper relate back to your thesis? How might you improve these connections?

- Is anything confusing about your language or organization? How might your clarify your language or organization?

- Have you made any errors with grammar, punctuation, or spelling? How can you correct these errors?

- What might someone who disagrees with you say about your paper? How can you address these opposing arguments in your paper? [26] X Research source

Features of Seminar Papers and Sample Thesis Statements

Community Q&A

- Keep in mind that seminar papers differ by discipline. Although most seminar papers share certain features, your discipline may have some requirements or features that are unique. For example, a seminar paper written for a Chemistry course may require you to include original data from your experiments, whereas a seminar paper for an English course may require you to include a literature review. Check with your student handbook or check with your advisor to find out about special features for seminar papers in your program. Make sure that you ask your professor about his/her expectations before you get started as well. [27] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- When coming up with a specific thesis, begin by arguing something broad and then gradually grow more specific in the points you want to argue. Thanks Helpful 23 Not Helpful 11

- Choose a topic that interests you, rather than something that seems like it will interest others. It is much easier and more enjoyable to write about something you care about. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 1

- Do not be afraid to admit any shortcomings or difficulties with your argument. Your thesis will be made stronger if you openly identify unresolved or problematic areas rather than glossing over them. Thanks Helpful 13 Not Helpful 6

- Plagiarism is a serious offense in the academic world. If you plagiarize your paper you may fail the assignment and even the course altogether. Make sure that you fully understand what is and is not considered plagiarism before you write your paper. Ask your teacher if you have any concerns or questions about your school’s plagiarism policy. Thanks Helpful 7 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://umweltoekonomie.uni-hohenheim.de/fileadmin/einrichtungen/umweltoekonomie/1-Studium_Lehre/Materialien_und_Informationen/Guidelines_Seminar_Paper_NEW_14.10.15.pdf

- ↑ https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/how-to-ask-professor-feedback/

- ↑ http://www.law.georgetown.edu/library/research/guides/seminar_papers.cfm

- ↑ https://www.stcloudstate.edu/writeplace/_files/documents/writing%20process/choosing-and-narrowing-an-essay-topic.pdf

- ↑ http://writing.ku.edu/prewriting-strategies

- ↑ http://www.kuwi.europa-uni.de/en/lehrstuhl/vs/politik3/Hinweise_Seminararbeiten/haenglish.html

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/faq/reliable

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/673/1/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/thesis-statements/

- ↑ https://www.irsc.edu/students/academicsupportcenter/researchpaper/researchpaper.aspx?id=4294967433

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/2/58/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/beginning-academic-essay

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/589/02/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/561/05/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/ReverseOutlines.html

About This Article

To write a seminar paper, start by writing a clear and specific thesis that expresses your original point of view. Then, work on your introduction, which should give your readers relevant context about your topic and present your argument in a logical way. As you write, break up the body of your paper with headings and sub-headings that categorize each section of your paper. This will help readers follow your argument. Conclude your paper by synthesizing your argument and explaining why this topic matters. Be sure to cite all the sources you used in a bibliography. For advice on getting started on your seminar paper, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Mehammed A.

Dec 28, 2023

Did this article help you?

Patrick Topf

Jul 4, 2017

Flora Ballot

Oct 10, 2016

Igwe Uchenna

Jul 19, 2017

Saudiya Kassim Aliyu

Oct 11, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Home » Blog » How to Write a Seminar Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Write a Seminar Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

Table of Contents

Learn How to Write a Seminar Paper

Writing and planning a seminar paper can be quite a challenge for any student. For many students, it is unusual to deal scientifically with a question or research question. In addition, you must be able to identify the overall problem and then derive specific work steps.

In this article, we would like to show you how to successfully plan and write a seminar paper. It’s not that difficult at all. If you have already dealt with the topic thoroughly, you are already on the right track. In addition to the content, the formal aspect of the work, namely the layout, should not be disregarded.

What is a seminar paper?

You write a seminar paper over a long period. As a result, this type of work is a headache for many students. With an exam, you learn at short notice and therefore you do not have to deal with the topic for a long time. When planning and preparing a seminar paper, you will have to deal with the work and the problem every day. Planning a seminar paper alone takes a lot of time. You must find a suitable topic. Furthermore, you must find a scientific problem that you want to solve with your seminar paper. Then you must research the literature operate and create a plan for the processing of all work steps so that you can submit your work on time. The curious thing is that planning your work will take you a lot more time than writing your work. If you have planned your term paper correctly from the beginning, then writing will only take up a fraction of the total time. Writing a seminar paper is exhausting. Therefore, you will also learn important key competencies and skills that you will need later in your job. During the planning and writing of your thesis, you will acquire the following important skills:

- You will acquire techniques of scientific work. This includes literature research, indirect and direct quotations, and dealing with a scientific problem over a longer period.

- You will acquire the relevant specialist vocabulary.

- You will understand the topic and be able to find a solution.

Tips for planning a seminar paper

You should not underestimate the planning of a seminar paper. Believe it or not, it represents the bulk of your work. Planning takes the most time. But if you do this correctly, the writing process will be very easy for you. In the following, we will show you what you need to consider when planning.

Find a seminar paper topic

It is not that easy to find a topic for the seminar paper. If your lecturer does not specify a topic, then you are on your own. In general, it would be good if you look again at all the topics, contents, and discussion points of the seminar. This gives you a basis for finding your topic. You should also proceed in such a way that you structure and prioritize the ideas found in a brainstorming session. But you must find a topic that interests you.

Literature research seminar paper

Now we come to the literature research. You should always have the goal in mind to back up you’re reasoning with sources. Finally, you can search for suitable sources for your work in the following places:

- The library: There is hardly a better place at the university to look for literature. In a library, you will not only find books but also electronic media that you can use for research. For example, you can use the OPAC (Online Public Access Catalog). In this way, you will ensure an excellent overview of the available literature on your topic.

- Electronic journal directory: The electronic journal directory allows you to search for magazines or specialist journals. Scientific journals are often seen as sources. They are often written in sophisticated language and deal with current and practical cases.

- Internet: The Internet is also a convenient way to find suitable sources. You can use the services of Google Scholar and Google Books. It can also happen from time to time that some books are not fully illustrated on these services. You will find a good overview of the sources that you need here. The tables of contents also give you a good reference point for your further research.

Discussion of the topic of a seminar paper