Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Social Intelligence, Leadership, and Problem Solving

DOI link for Social Intelligence, Leadership, and Problem Solving

Get Citation

In this volume, M. Afzalur Rahim gathers ten contributions covering a diverse range of topics. These include Type III error in medical decision making, a theoretical model of social intelligence, a structural equations model of social intelligence, servant theory of leadership, entrepreneurial motives and orientations, stress and strain among self-employed and organizationally employed employees, a theory of communication nexus, foreign direct investment from emerging markets, operations and strategy of healthcare management, and knowledge recipients and knowledge transfer.international perspectives.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter | 14 pages, medical decision-making as argument: the role of the probability of implication, chapter | 24 pages, foundations of social intelligence: a conceptual model with implications for business performance, a model of leaders’ social intelligence, interpersonal justice, and creative performance, chapter 4 | 34 pages, servant leadership and psychological climate as moderators of job satisfaction–organizational citizenship behavior relationship, chapter 5 | 12 pages, entrepreneurship motives, entrepreneurial orientation, and duration of new french firms, chapter 6 | 16 pages, relationship between job-related stressors and job burnout: differences between self-employed and organization-employed professionals, chapter 7 | 20 pages, communicating in the 21st-century workplace, outward foreign direct investment activities and strategies by firms from emerging markets: management literature review from 2005 to 2010, healthcare management: operations and strategy, the relationships of knowledge recipients and knowledge transfer at japanese mncs based in china, chapter | 11 pages, book reviews.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

1st Edition

Social Intelligence, Leadership, and Problem Solving

- Taylor & Francis eBooks (Institutional Purchase) Opens in new tab or window

Description

In this volume, M. Afzalur Rahim gathers ten contributions covering a diverse range of topics. These include Type III error in medical decision making, a theoretical model of social intelligence, a structural equations model of social intelligence, servant theory of leadership, entrepreneurial motives and orientations, stress and strain among self-employed and organizationally employed employees, a theory of communication nexus, foreign direct investment from emerging markets, operations and strategy of healthcare management, and knowledge recipients and knowledge transfer.international perspectives.

Table of Contents

M. Afzalur Rahim

About VitalSource eBooks

VitalSource is a leading provider of eBooks.

- Access your materials anywhere, at anytime.

- Customer preferences like text size, font type, page color and more.

- Take annotations in line as you read.

Multiple eBook Copies

This eBook is already in your shopping cart. If you would like to replace it with a different purchasing option please remove the current eBook option from your cart.

Book Preview

The country you have selected will result in the following:

- Product pricing will be adjusted to match the corresponding currency.

- The title Perception will be removed from your cart because it is not available in this region.

Select your cookie preferences

We use cookies and similar tools that are necessary to enable you to make purchases, to enhance your shopping experiences and to provide our services, as detailed in our Cookie notice . We also use these cookies to understand how customers use our services (for example, by measuring site visits) so we can make improvements.

If you agree, we'll also use cookies to complement your shopping experience across the Amazon stores as described in our Cookie notice . Your choice applies to using first-party and third-party advertising cookies on this service. Cookies store or access standard device information such as a unique identifier. The 103 third parties who use cookies on this service do so for their purposes of displaying and measuring personalized ads, generating audience insights, and developing and improving products. Click "Decline" to reject, or "Customise" to make more detailed advertising choices, or learn more. You can change your choices at any time by visiting Cookie preferences , as described in the Cookie notice. To learn more about how and for what purposes Amazon uses personal information (such as Amazon Store order history), please visit our Privacy notice .

Search with any image

Unsupported image file format.

The image file size is too large..

Drag an image here

- Business, Finance & Law

- Management Skills

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet or computer – no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Social Intelligence, Leadership, and Problem Solving: 16 (Current Topics in Management) Hardcover – 15 Jan. 2013

In this volume, M. Afzalur Rahim gathers ten contributions covering a diverse range of topics. These include Type III error in medical decision making, a theoretical model of social intelligence, a structural equations model of social intelligence, servant theory of leadership, entrepreneurial motives and orientations, stress and strain among self-employed and organizationally employed employees, a theory of communication nexus, foreign direct investment from emerging markets, operations and strategy of healthcare management, and knowledge recipients and knowledge transfer.international perspectives.

- ISBN-10 1412851734

- ISBN-13 978-1412851732

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Transaction Publishers

- Publication date 15 Jan. 2013

- Language English

- Dimensions 15.88 x 1.91 x 23.5 cm

- Print length 212 pages

- See all details

Product description

-Ten papers explore topics in social intelligence, leadership, and problem solving. Papers discuss medical decision making as argument--the role of the probability of implication; foundations of social intelligence--a conceptual model with implications for business performance; a model of leaders' social intelligence, interpersonal justice, and creative performance; servant leadership and psychological climate as moderators of job satisfaction-organizational citizenship behavior relationship; entrepreneurship motives, entrepreneurial orientation, and duration of new French firms; relationship between job-related stressors and job burnout--differences between self-employed and organization-employed professionals; communication in the twenty-first-century workplace--a theory of communication nexus; outward foreign direct investment activities and strategies by firms from emerging markets--management literature review from 2005 to 2010; health care management--operations and strategy; and the relationships of knowledge recipients and knowledge transfer at Japanese multinational corporations based in China.-

-- Journal of Economic Literature

"Ten papers explore topics in social intelligence, leadership, and problem solving. Papers discuss medical decision making as argument--the role of the probability of implication; foundations of social intelligence--a conceptual model with implications for business performance; a model of leaders' social intelligence, interpersonal justice, and creative performance; servant leadership and psychological climate as moderators of job satisfaction-organizational citizenship behavior relationship; entrepreneurship motives, entrepreneurial orientation, and duration of new French firms; relationship between job-related stressors and job burnout--differences between self-employed and organization-employed professionals; communication in the twenty-first-century workplace--a theory of communication nexus; outward foreign direct investment activities and strategies by firms from emerging markets--management literature review from 2005 to 2010; health care management--operations and strategy; and the relationships of knowledge recipients and knowledge transfer at Japanese multinational corporations based in China."

--Journal of Economic Literature

About the Author

Product details.

- Publisher : Transaction Publishers; 1st edition (15 Jan. 2013)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 212 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1412851734

- ISBN-13 : 978-1412851732

- Dimensions : 15.88 x 1.91 x 23.5 cm

Customer reviews

| 5 star | 0% | |

| 4 star | 0% | |

| 3 star | 0% | |

| 2 star | 0% | |

| 1 star | 0% |

Our goal is to make sure that every review is trustworthy and useful. That's why we use both technology and human investigators to block fake reviews before customers ever see them. Learn more

We block Amazon accounts that violate our Community guidelines. We also block sellers who buy reviews and take legal actions against parties who provide these reviews. Learn how to report

No customer reviews

- UK Modern Slavery Statement

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell on Amazon Handmade

- Associates Programme

- Fulfilment by Amazon

- Seller Fulfilled Prime

- Advertise Your Products

- Independently Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Platinum Mastercard

- Amazon Classic Mastercard

- Amazon Money Store

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Payment Methods Help

- Shop with Points

- Top Up Your Account

- Top Up Your Account in Store

- COVID-19 and Amazon

- Track Packages or View Orders

- Delivery Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Amazon Mobile App

- Amazon Assistant

- Customer Service

- Accessibility

- Conditions of Use & Sale

- Privacy Notice

- Cookies Notice

- Interest-Based Ads Notice

Social Intelligence, Leadership, and Problem Solving

About this ebook, about the author, rate this ebook, reading information, continue the series.

More by M. Afzalur Rahim

Social Intelligence, Leadership, and Problem Solving

By m. afzalur rahim.

- 0 Want to read

- 0 Currently reading

- 0 Have read

My Reading Lists:

Use this Work

Create a new list

My book notes.

My private notes about this edition:

Check nearby libraries

- Library.link

Buy this book

This edition doesn't have a description yet. Can you add one ?

Showing 7 featured editions. View all 7 editions?

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

Add another edition?

Book Details

The physical object, community reviews (0).

- Created February 27, 2022

Wikipedia citation

Copy and paste this code into your Wikipedia page. Need help?

| Created by | Imported from . |

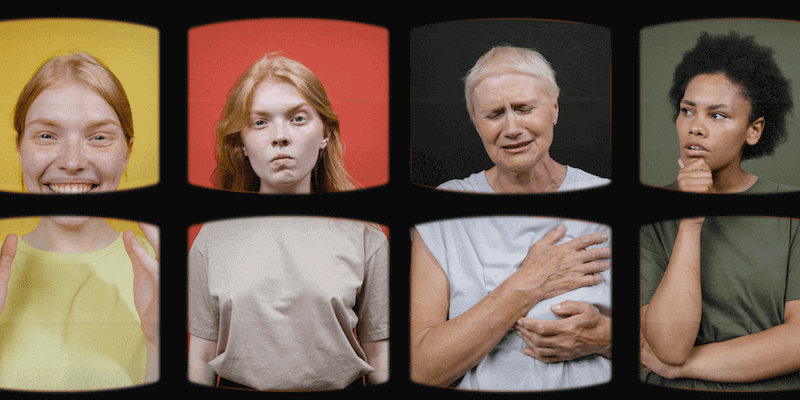

Social Intelligence: Building Strong Workplace Relationships as a Leader

What is social intelligence, and why it matters in the workplace, understanding the characteristics of socially intelligent leaders, the link between social intelligence and effective leadership, developing social intelligence in the workplace, improving social intelligence as a leader or manager, empathy and understanding team members, clear communication skills, positive attitude and outlook.

- Mastering Leadership: How to Inspire a Team Effectively

- How to Handle Defensive Behavior in the Workplace? 7 Tips for Managers

- The Role of a Technical Leader: Driving Success in Tech Projects

- Understanding The Role Of Team Dynamics To Make A Healthy Work Environment

- How Lack Of Trust In The Workplace Can Destroy The Work Culture

- Mastering Leadership Team Development Techniques

- How Can You Prevent A Negative Conversation At Work From Escalating?

- New manager assimilation: Why it’s Important and 10 Key Questions

- Top 6 Roles of virtual Training Badges for Motivation in digital era

- 5 Secrets To Ace Project Manager Training

Improved Team Collaboration and Performance

Better conflict resolution, increased employee engagement and satisfaction.

Active Listening Techniques

Cultural awareness and sensitivity, encouraging open communication and feedback, identifying personal biases and blind spots, seeking feedback and self-reflection, investing in training and coaching, take a free active listening assessment to become a socially intelligent leader..

Active listening helps managers navigate work environments effectively. Assess your skills today to become a pro.

What are the types of social intelligence?

How do you show social intelligence, what are the 5 characteristics of social intelligence.

Other Related Blogs

Emotional Intelligence In Communication: 5 Ways Smart Leaders Act

Iq vs eq in the workplace: how to use both together, 11 transferable skills examples: understand why it is important with example, top 8 essential skills for cultural dexterity in a globalized world.

Search with any image

Unsupported image file format.

Image file size is too large..

Drag an image here

- Business & Money

- Business Culture

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Social Intelligence, Leadership, and Problem Solving (Current Topics in Management) 1st Edition

In this volume, M. Afzalur Rahim gathers ten contributions covering a diverse range of topics. These include Type III error in medical decision making, a theoretical model of social intelligence, a structural equations model of social intelligence, servant theory of leadership, entrepreneurial motives and orientations, stress and strain among self-employed and organizationally employed employees, a theory of communication nexus, foreign direct investment from emerging markets, operations and strategy of healthcare management, and knowledge recipients and knowledge transfer.international perspectives.

- ISBN-10 1138514683

- ISBN-13 978-1138514683

- Edition 1st

- Publication date July 26, 2017

- Language English

- Dimensions 5.98 x 0.48 x 9.02 inches

- Print length 212 pages

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Routledge; 1st edition (July 26, 2017)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 212 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1138514683

- ISBN-13 : 978-1138514683

- Item Weight : 16 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.98 x 0.48 x 9.02 inches

Customer reviews

| 5 star | 0% | |

| 4 star | 0% | |

| 3 star | 0% | |

| 2 star | 0% | |

| 1 star | 0% |

Our goal is to make sure every review is trustworthy and useful. That's why we use both technology and human investigators to block fake reviews before customers ever see them. Learn more

We block Amazon accounts that violate our community guidelines. We also block sellers who buy reviews and take legal actions against parties who provide these reviews. Learn how to report

No customer reviews

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Amazon Assistant

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Social Intelligence: What It Is and Why We Need It More than Ever Before

- First Online: 26 January 2020

Cite this chapter

- Robert J. Sternberg 3 &

- Avery Siying Li 3

3074 Accesses

2 Citations

In this chapter, we discuss social intelligence and why it is of crucial importance to the world today. We open by defining social intelligence. Then we discuss whether social intelligence should be separated from general intelligence. Then we discuss the role of nonverbal communication in social intelligence. Finally, we discuss how social intelligence fits into a broader notion of adaptive intelligence. We conclude that, in the twenty-first century, the major problems the world is facing will be solved not merely by exercise of cognitive intelligence but by exercise of social intelligence and related constructs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Look Toward the Future of Social Attention Research

GRASP agents: social first, intelligent later

The future of social cognition: paradigms, concepts and experiments.

Ambady, N., & Gray, H. M. (2002). On being sad and, mistaken: Mood effects on the accuracy of thin-slice judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 , 947–996.

Article Google Scholar

Azuma, H., & Kashiwagi, K. (1987). Descriptions for an intelligent person: A Japanese study. Japanese Psychological Research, 29 , 17–26.

Barker, L. L., & Collins, N. B. (1970). Nonverbal and kinesic research. In P. Emmert & W. D. Brooks (Eds.), Methods of research in communication (pp. 343–371). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Google Scholar

Barnes, M. L., & Sternberg, R. J. (1989). Social intelligence and decoding of nonverbal cues. Intelligence, 13 , 263–287.

Baron-Cohen, S., Ring, H. A., Wheelwright, S., Bullmore, E. T., Brammer, M. J., Simmons, A., & Williams, S. R. (1999). Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: An fMRI study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 11 , 1891–1898.

Bellinger, D. (in press). Environment and intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Binet, A., & Simon, T. (1916). The development of intelligence in children: The Binet-Simon Scale. (E. S. Kite, Trans.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. [1905 for the original French version].

Brothers, L., Ring, B., & Kling, A. (1990). Responses of neurons in the macaque amygdala to complex social stimuli. Behavioral Brain Research, 41 , 199–213.

Burgoon, J. K., Buller, D. B., & Woodall, W. G. (1996). Nonverbal communication: The unspoken dialog . New York: Harper & Row.

Chesebro, J. L. (2014). Professional communication at work: Interpersonal strategies for career success . New York: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Damasio, A., Tranel, D., & Damasio, H. (1990). Individuals with sociopathic behavior caused by frontal lobe damage fail to respond autonomically to socially charged stimuli. Behavioral Brain Research, 14 , 81–94.

Dasen, P. (1984). The cross-cultural study of intelligence: Piaget and the Baoule. International Journal of Psychology, 19 , 407–434.

Dewey, J. (1909). Moral principles in education . New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Dimberg, U., Thunberg, M., & Elmehed, K. (2000). Unconscious facial reactions to emotional facial expressions. Psychological Science, 11 , 86–89.

Duncan, S. D., Jr. (1969). Nonverbal communication. Psychological Bulletin, 72 , 118–137.

Flynn, J. R. (1984). The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychological Bulletin, 95 , 29–51.

Flynn, J. R., & Sternberg, R. J. (in press). Environmental effects on intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Human intelligence: An introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Frensch, P. A., & Sternberg, R. J. (1989). Expertise and intelligent thinking: When is it worse to know better? In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of human intelligence (Vol. 5, pp. 157–188). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences . New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2011). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences (rev.) . New York: Basic Books.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence . New York, NY: Bantam.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships . New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Gorman, C. K. (2011). Avoiding mixed messages: Understand the impact of body language. Strategic Communication Management, 15 (4), 32–35.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography. Intelligence, 24 , 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(97)90011-8

Green, B. F. (1981). A primer of testing. American Psychologist, 36 , 1001–1011.

Grewal, D., Roggeveen, A. L., Puccinelli, N. M., & Spence, C. (2014). Retail atmospherics and in-store nonverbal cues: An introduction. Psychology and Marketing, 31 (7), 469–471.

Grigorenko, E. L., Geissler, P. W., Prince, R., Okatcha, F., Nokes, C., Kenny, D. A., … Sternberg, R. J. (2001). The organization of Luo conceptions of intelligence: A study of implicit theories in a Kenyan village. International Journal of Behavior Development, 25 , 367–378.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Guilford, J. P., & Hoepfner, R. (1971). The analysis of intelligence . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hall, J. A., Coats, E. J., & Smith LeBeau, L. (2005). Nonverbal behavior and the vertical dimension of social relations: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 131 , 898–924.

Hall, J. A., Horgan, T. G., & Murphy, N. A. (2019). Nonverbal communication. Annual Review of Psychology, 70 , 271–294.

Hall, J. A., Rosenthal, R., Archer, D., DiMatteo, M. R., & Rogers, P. L. (1977). Nonverbal skills in the classroom. Theory Into Practice, 16 (3), 162–166.

Harper, R. G., Wiens, A. N., & Matarazzo, J. D. (1978). Nonverbal communication: The state of the art . Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Hedlund, J. (in press). Practical intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hedlund, J., Forsythe, G. B., Horvath, J. A., Williams, W. M., Snook, S., & Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Identifying and assessing tacit knowledge: Understanding the practical intelligence of military leaders. Leadership Quarterly, 14 , 117–140.

Hedlund, J., Wilt, J. M., Nebel, K. R., Ashford, S. J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2006). Assessing practical intelligence in business school admissions: A supplement to the Graduate Management Admissions Test. Learning and Individual Differences, 16 , 101–127.

Hogan, K. (2008). The secret language of business: How to read anyone in 3 seconds or less . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Horvath, J. A., Forsythe, G. B., Bullis, R. C., Sweeney, P. J., Williams, W. M., McNally, J. A., … Sternberg, R. J. (1999). Experience, knowledge, and military leadership. In R. J. Sternberg & J. A. Horvath (Eds.), Tacit knowledge in professional practice (pp. 39–71). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Humphrey, N. K. (1976). The social function of intellect. In P. Bateson & R. Hinde (Eds.), Growing points in ethology . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karmiloff-Smith, A., Grant, J., Bellugi, U., & Baron-Cohen, S. (1995). Is there a social module? Language, face-processing and theory of mind in William’s Syndrome and autism, in press. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 7 , 196–208.

Keating, D. K. (1978). A search for social intelligence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 70 , 218–233.

Kihlstrom, J. F., & Cantor, N. (2000). Social intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 359–379). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Kihlstrom, J. F., & Cantor, N. (2011). Social intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence (pp. 564–581). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kihlstrom, J. F., & Cantor, N. (in press). Social intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Klin, A., Saulnier, C. A., Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., Volkmar, F. R., & Lord, C. (2006). Social and communication abilities and disabilities in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: The Vineland and the ADOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37 (4), 748–759.

Knapp, M. L. (1972). The field of nonverbal communication: An overview. In C. J. Stewart & B. Kendall (Eds.), On speech communication: An Anthology of contemporary writings and messages (pp. 107–161). New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Kudesia, R. S., & Elfenbein, H. A. (2013). Nonverbal communication in the workplace . In Nonverbal Communication: Handbooks of Communication Science (pp. 805–831). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter.

Marlowe, H. A. (1986). Social intelligence: Evidence for multidimensionality and construct independence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78 (1), 52–58.

Marlowe, H. A., & Bedell, J. R. (1982). Social intelligence: Further evidence for the independence of the construct. Psychological Reports, 51 , 461–462.

O’Sullivan, M., Guilford, J. P., & deMille, R. (1965). The measurement of social intelligence. Psychological Laboratory Report, Los Angeles, University of Southern California , No. 34.

Perkins, P. S. (2008). The art and science of communication: Tools for effective communication in the workplace . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Polanyi, M. (1976). Tacit knowledge. In M. Marx & F. Goodson (Eds.), Theories in contemporary psychology (pp. 330–344). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Poyatos, F. (1974). The challenge of “total body communication” as an interdisciplinary field of integrative research . Paper presented at the meeting of the International Congress of Semiotic Sciences, Milan.

Puccinelli, N. M., Motyka, S., & Grewal, D. (2010). Can you trust a customer’s expression? Insights into nonverbal communication in the retail context. Psychology and Marketing, 27 (10), 964–988.

Reusch, J., & Kees, W. (1972). Nonverbal communication: Notes on the visual perception of human relations (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Riggio, R. E., Messamer, J., & Throckmorton, B. (1991). Social and academic intelligence: conceptually distinct but overlapping constructs. Personality and Individual Differences, 12 (7), 695–702.

Romney, D. M., & Pyryt, M. C. (1999). Guilford’s concept of social intelligence revisited. High Ability Studies, 10 (2), 137–142.

Ruzgis, P. M., & Grigorenko, E. L. (1994). Cultural meaning systems, intelligence and personality. In R. J. Sternberg & P. Ruzgis (Eds.), Personality and intelligence (pp. 248–270). New York: Cambridge.

Sackett, P. R., Shewach, O. R., & Dahlke, J. A. (in press). The predictive value of general intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Human intelligence: An introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Serpell, R. (1974). Aspects of intelligence in a developing country. African Social Research, No., 17 , 576–596.

Snyderman, M., & Rothman, S. (1987). Survey of expert opinion on intelligence and aptitude testing. American Psychologist, 42 (2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.42.2.137

Spearman, C. (1927). The abilities of man . New York: Macmillan.

Sternberg, R. J. (1990). Metaphors of mind . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). The triarchic theory of intelligence. In D. P. Flanagan, J. L. Genshaft, & P. L. Harrison (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (pp. 92–104). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (2000). Implicit theories of intelligence as exemplar stories of success: Why intelligence test validity is in the eye of the beholder. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 6 (1), 159–167.

Sternberg, R. J. (2009). The Rainbow and Kaleidoscope Projects: A new psychological approach to undergraduate admissions. European Psychologist, 14 , 279–287.

Sternberg, R. J. (2010). College admissions for the 21st century . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (2019). Introduction to the Cambridge Handbook of Wisdom: Race to Samarra: The critical importance of wisdom in the world today. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Glueck (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of wisdom (pp. 3–9). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (in press-a). Adaptive intelligence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (in press-b). The augmented theory of successful intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence (2nd ed.) . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.) (in press-c). Cambridge handbook of intelligence (2nd ed.) . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., Conway, B. E., Ketron, J. L., & Bernstein, M. (1981). People’s conceptions of intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41 , 37–55.

Sternberg, R. J., & Dobson, D. M. (1987). Resolving interpersonal conflicts: An analysis of stylistic consistency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 , 794–812.

Sternberg, R. J., Forsythe, G. B., Hedlund, J., Horvath, J., Snook, S., Williams, W. M., … Grigorenko, E. L. (2000). Practical intelligence in everyday life . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., & Hedlund, J. (2002). Practical intelligence, g, and work psychology. Human Performance, 15 (1/2), 143–160.

Sternberg, R. J., & Kaufman, S. B. (Eds.). (2011). Cambridge handbook of intelligence . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., Nokes, K., Geissler, P. W., Prince, R., Okatcha, F., Bundy, D. A., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2001). The relationship between academic and practical intelligence: A case study in Kenya. Intelligence, 29 , 401–418.

Sternberg, R. J., & Smith, C. (1985). Social intelligence and decoding skills in nonverbal communication. Social Cognition , ( 2 ), 168–192.

Sternberg, R. J., & Soriano, L. J. (1984). Styles of conflict resolution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47 , 115–126.

Sternberg, R. J., Wong, C. H., & Sternberg, K. (2019). The relation of tests of scientific reasoning to each other and to tests of fluid intelligence. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Stricker, L. J. (1982). Interpersonal competence instrument: Development and preliminary findings. Applied Psychological Measurement, 6 , 69–81.

Sundaram, D. S., & Webster, C. (2000). The role of nonverbal communication in service encounters. Journal of Service Marketing, 14 (5), 378–391.

Super, C. M., & Harkness, S. (1982). The development of affect in infancy and early childhood. In D. Wagnet & H. Stevenson (Eds.), Cultural perspectives on child development (pp. 1–19). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Thorndike, E. L. (1920). The assessment of social intelligence. Psychotherapy, 27 , 445–457.

Tranel, D., & Hyman, B. T. (1990). Neuropsychological correlates of bilateral amygdala damage. Archives of Neurology, 47 (3), 349–355.

Wagner, R. K. (2011). Practical intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg & S. B. Kaufman (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence (pp. 550–563). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Walker, R. E., & Foley, J. M. (1973). Social intelligence: Its history and measurement. Psychological Report, 33 , 839–864.

Washburn, P. V., & Hakel, M. D. (1973). Visual cues and verbal content as influences on impressions formed after simulated employment interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 58 , 137–141.

Wechsler, D. (1944). The measurement of adult intelligence . Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Wechsler, D. (1958). The measurement and appraisal of adult intelligence (4th ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Wedeck, J. (1947). The relationship between personality and “psychological ability”. British Journal of Psychology, 37 , 133–151.

Yang, S., & Sternberg, R. J. (1997a). Conceptions of intelligence in ancient Chinese philosophy. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 17 , 101–119.

Yang, S., & Sternberg, R. J. (1997b). Taiwanese Chinese people’s conceptions of intelligence. Intelligence, 25 , 21–36.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Human Development, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Robert J. Sternberg & Avery Siying Li

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert J. Sternberg .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Robert J. Sternberg

Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Psychology, The University of Niš, Niš, Serbia

Aleksandra Kostić

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Sternberg, R.J., Li, A.S. (2020). Social Intelligence: What It Is and Why We Need It More than Ever Before. In: Sternberg, R.J., Kostić, A. (eds) Social Intelligence and Nonverbal Communication. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34964-6_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34964-6_1

Published : 26 January 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-34963-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-34964-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, a process model of social intelligence and problem-solving style for conflict management.

International Journal of Conflict Management

ISSN : 1044-4068

Article publication date: 17 May 2018

Issue publication date: 13 August 2018

This study aims to explore the relationship between social intelligence (SI) and problem-solving (PS) style of handling conflict.

Design/methodology/approach

Data on SI and PS were collected with questionnaires from 406 faculty members, and the data were averaged by departments. This resulted in a sample of 43 departments, and all the data analyses were performed with this sample of 43. SI is defined as the ability to be aware of relevant social situations, to handle situational challenges effectively, to understand others’ concerns and feelings and to build and maintain positive relationships in social settings.

Data analyses with LISREL at the department level suggest that SI is positively associated with PS.

Research limitations/implications

Data were collected from only one public university in the USA, which might limit the generalizability of the results. The department chairs need to acquire the four components of SI to improve faculty members’ PS. This will hopefully lead to constructive management of many faculty–department chair conflicts.

Originality/value

One of the strengths of this study is that the measures of endogenous and exogenous variables were analyzed at the department level, not individual level. This study contributed to our understanding of the relationships of situational awareness, situational response, cognitive empathy and social skills with each other and to PS.

- Problem solving

- Intelligence

- Social intelligence

Rahim, A. , Civelek, I. and Liang, F.H. (2018), "A process model of social intelligence and problem-solving style for conflict management", International Journal of Conflict Management , Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 487-499. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-06-2017-0055

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Seven Ways to Be an Emotionally Intelligent Leader

David, a school counselor, took a deep breath when he saw a missed call from his principal. As he touched the screen to call back, he braced for the “bark and the bite” he was accustomed to hearing from Principal Carrie.

This time was different.

In fact, he told us he was stunned when the voice that picked up sounded kind, even cheerful. He couldn’t believe it. After years of working together, he had grown to dread interactions with Principal Carrie, as had most of his colleagues. But this was clearly a different version of her. Who was this new principal, and what had she done with Carrie?

Carrie was finishing up a year of engagement in emotionally intelligent leadership coaching—a program designed to enhance leaders’ well-being through education and training in social and emotional skills.

Recent research from the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence supports the notion that emotionally intelligent school leadership predicts educator well-being, and we know that well-being and emotional intelligence skills are necessary for effective leadership, especially in times of crisis—from higher job satisfaction to lower emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions. Indeed, even when leaders, especially in education, have little to no control over their environment, they have control over their own behavior and can still cultivate a culture of healthy relationships and emotionally intelligent responses to uncontrollable circumstances. School leaders who have decided to invest in their own emotional intelligence and well-being consistently report interactions like the one between David and Carrie.

But doing so is no easy feat. Carrie came to us as many school leaders have in recent years: chronically stressed, overwhelmed, and exhausted. The job she loved was feeling increasingly unsustainable. Her distress was also affecting her colleagues, to the detriment of teachers and students alike. Carrie had been in education for nearly 25 years, but it was the last four years that had shaken the sustainability of her career. And who could blame her?

Ever-shifting rules, regulations, and ripple effects of the pandemic brought demands on school staff and leadership to a peak, straining an already turbulent educational landscape. Monitoring COVID-19 absences, distributing laptops in bulk, adapting curriculum for uncharted virtual territory, and consoling frightened, grieving students and families suddenly became daily tasks for which school leaders were held accountable.

Those new responsibilities added to pre-existing pressures and crises that they were already navigating daily, such as teacher turnover, inequitable funding, politicization of learning material, mental health, school safety, standardized testing, and, of course, the overwhelming influence of social media, artificial intelligence, and technology. Altogether, these factors created a web of uncertainties and challenges so great for even the most effective, seasoned leader to sustain.

So, where does that leave school leaders like Carrie?

While she could not fix, on a day-to-day basis, the systemic problems that made her job so stressful, Carrie could invest in her well-being by regularly practicing emotion regulation techniques and modeling these behaviors for others, like practicing reframing and turning moments of harsh criticism to compassion. While she could not eliminate the stress, she could be more committed to getting more sleep, cutting down on sugar, and walking 10 minutes a day—activities that will positively affect mental and physical well-being. It is crucial that school leaders have the tools to realistically assess what they can and can’t do to create greater well-being and leader effectiveness.

And this is just what Carrie did—and all school leaders can do—using strategies provided in our new book, Emotional Intelligence for School Leaders . We offer tips for harnessing a healthier you and, in turn, healthier relationships. It’s this emotionally intelligent leadership that will help you to not just survive but thrive in the ever-demanding landscape of education.

Check in with your emotions regularly—and honor them. Before rushing into the hectic schedule of each day, pencil in time to sit and reflect on how you feel. Your emotions give you important information . They are not something to simply ignore or push away. Your emotions will inevitably influence your conversations, behaviors, and relationships whether you notice it or not (recall David’s long-held impression of Carrie). Prior to a meeting, event, or other obligation, prioritize a few minutes to honor and assess your own well-being. This could be through silent reflection, journaling, or even apps on your phone like How We Feel , a handheld journal that helps you name, track, and better understand your emotions.

Regulate your emotions. Checking in with your emotions is one crucial piece of the emotional intelligence puzzle; you have to be able to name it to tame it. Regulating, or managing, those emotions is another. While feeling joyful or proud may not require strategies to help you stay grounded, feeling angry or burned out certainly do—and you may experience all of these emotions on any given school day. Identify strategies that are sustainable and beneficial for managing your big emotions in challenging moments, such as mindful breathing, meditation, or pausing your schedule to take a walk outside before a demanding situation overwhelms you. Such practices don’t actually take up much time—just a few minutes—but the benefits are evergreen.

Establish clear boundaries and stick to them. We know how hard this one can be. In an environment that constantly asks you to say “yes,” we challenge you to say “no” more often . This can look like rescheduling a meeting (or canceling it if it “could’ve been an email”) or extending a deadline for your colleagues so everyone has some breathing room. Leaning on emotion regulation techniques above, identify circumstances that are most emotionally taxing for you, which tasks you can delegate to others (don’t be afraid to ask for help!), and where you can reallocate your energy for better use.

Listen with empathy and without judgment. School leaders cannot afford to be “too busy” to listen to each other and elicit feedback in school settings. Active listening builds trust. The moment we are too overbooked to engage in authentic conversation with colleagues, we can quickly lose our emotional regulation, our boundaries, and our purpose. It’s a slippery slope to devolving into unhealthy, transactional relationships. Even in the most strenuous circumstances, aim to be an emotion scientist —curious about your own and others’ emotions—and a learner, not just a responder in times of crisis.

Reflect often. It is critical that school leaders create safe spaces or practices dedicated to self-care through self-reflection. Some leaders pipe in music to create a meditative environment throughout school hallways, others close their doors to give themselves space when needed. Some take a five-minute walking meditation outside the school. We have seen more and more leaders embrace personal/professional coaching to create regular time to reflect on actions taken, decisions to be made, and emotional responses. Because leadership entails co-regulation, reflection leads to opportunities for strengthening your own emotion regulation muscles as well as co-regulating with others.

Nurture your relationships. The people you work with will enhance your mood or squash it. And you can enhance or squash theirs . Aim to be the enhancer by greeting people with a smile, asking them how they are feeling and taking time to listen to the answer, creating opportunities for everyone’s voice to be heard, giving others a shoutout when they achieve, and remembering to be a curious emotion scientist. Investing time and energy in your relationships will make all the difference in building trust and motivation needed for others to wholeheartedly join you in making your vision a reality.

Model for others. Emotions are social and contagious components of life. When you prioritize your own emotional well-being, boundaries, and interpersonal relationships, it shows and it rubs off on others. Just as annoyance or frustration from your morning meeting can spill into your afternoon check-in, so can your balance, appreciation, or gratitude. In using the techniques we’ve discussed, you simultaneously model for others what emotional intelligence looks like in practice to the benefit of your students, staff, and self.

About the Authors

Robin Stern

Robin Stern, Ph.D. , is the cofounder and senior advisor to the director, Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, and is a licensed psychoanalyst with 30 years of experience. She is the co-developer of RULER (an acronym for the five key emotion skills of recognizing, understanding, labeling, expressing, and regulating emotions), an evidence-based approach to social and emotional learning that has been adopted by over 4,500 schools across the United States and in 27 other countries.

Janet Patti

Janet Patti, Ed.D. , is the cofounder and chief executive officer of Star Factor Coaching, a leadership development organization grounded in the latest science and practice of emotional intelligence.

Krista Smith

Krista Smith, MAT , is an incoming master of nonprofit leadership student at the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy and Practice. She has worked at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence as a postgraduate associate and is a former high school special education teacher in South Side Chicago.

You May Also Enjoy

How to Cultivate Humble Leadership

Five Ways to Support the Well-Being of School Leaders

Three Reasons for Leaders to Cultivate Intellectual Humility

Six Self-Care Practices for School Leaders

How to Become a Scientist of Your Own Emotions

Is Attention the Secret to Emotional Intelligence?

Addressing employee burnout: Are you solving the right problem?

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated and exacerbated long-standing corporate challenges to employee health and well-being , and in particular employee mental health. 1 When used in this article, “mental health” is a term inclusive of positive mental health and the full range of mental, substance use, and neurological conditions. This has resulted in reports of rapidly rising rates of burnout 2 When used in this article, “burnout” and “burnout symptoms” refer to work-driven burnout symptoms (per sidebar “What is burnout?”). around the world (see sidebar “What is burnout?”).

About the authors

This article is a collaborative effort by Jacqueline Brassey , Erica Coe , Martin Dewhurst, Kana Enomoto , Renata Giarola, Brad Herbig, and Barbara Jeffery , representing the views of the McKinsey Health Institute.

Many employers have responded by investing more into mental health and well-being than ever before. Across the globe, four in five HR leaders report that mental health and well-being is a top priority for their organization. 3 McKinsey Health Institute Employee Mental Health and Wellbeing Survey, 2022: n (employee) = 14,509; n (HR decision maker) = 1,389. Many companies offer a host of wellness benefits such as yoga, meditation app subscriptions, well-being days, and trainings on time management and productivity. In fact, it is estimated that nine in ten organizations around the world offer some form of wellness program. 4 Charlotte Lieberman, “What wellness programs don’t do for workers,” Harvard Business Review , August 14, 2019.

As laudable as these efforts are, we have found that many employers focus on individual-level interventions that remediate symptoms, rather than resolve the causes of employee burnout. 5 Anna-Lisa Eilerts et al., “Evidence of workplace interventions—A systematic review of systematic reviews,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 2019, Volume 16, Number 19. Employing these types of interventions may lead employers to overestimate the impact of their wellness programs and benefits 6 Katherine Baicker et al., “Effect of a workplace wellness program on employee health and economic outcomes: A randomized clinical trial,” JAMA , 2019, Volume 321, Number 15; erratum published in JAMA , April 17, 2019. and to underestimate the critical role of the workplace in reducing burnout and supporting employee mental health and well-being. 7 Pascale M. Le Blanc, et al., “Burnout interventions: An overview and illustration,” in Jonathan R. B. Halbesleben’s Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care , New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers, 2008; Peyman Adibi et al., “Interventions for physician burnout: A systematic review of systematic reviews,” International Journal of Preventive Medicine , July 2018, Volume 9, Number 1.

What is burnout?

According to the World Health Organization, burnout is an occupational phenomenon. It is driven by a chronic imbalance between job demands 1 Job demands are physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs—for example, work overload and expectations, interpersonal conflict, and job insecurity. Job resources are those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that may do any of the following: (a) be functional in achieving work goals; (b) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs; (c) stimulate personal growth and development such as feedback, job control, social support (Wilmar B. Schaufeli and Toon W. Taris, “A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health,” from Georg F. Bauer and Oliver Hämmig’s Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach , first edition, Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer, 2014). (for example, workload pressure and poor working environment) and job resources (for example, job autonomy and supportive work relationships). It is characterized by extreme tiredness, reduced ability to regulate cognitive and emotional processes, and mental distancing. Burnout has been demonstrated to be correlated with anxiety and depression, a potential predictor of broader mental health challenges. 2 Previous meta-analytic findings demonstrate moderate positive correlations of burnout with anxiety and depression—suggesting that anxiety and depression are related to burnout but represent different constructs (Katerina Georganta et al., “The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Frontiers in Psychology , March 2019, Volume 10, Article 284). When used in this article, burnout does not imply a clinical condition.

Research shows that, when asked about aspects of their jobs that undermine their mental health and well-being, 8 Paula Davis, Beating Burnout at Work: Why Teams Hold the Secret to Well-Being and Resilience , Philadelphia, PA: Wharton School Press, 2021. employees frequently cite the feeling of always being on call, unfair treatment, unreasonable workload, low autonomy, and lack of social support. 9 Jennifer Moss, The Burnout Epidemic: The Rise of Chronic Stress and How We Can Fix It , Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2021. Those are not challenges likely to be reversed with wellness programs. In fact, decades of research suggest that interventions targeting only individuals are far less likely to have a sustainable impact on employee health than systemic solutions, including organizational-level interventions. 10 Hanno Hoven et al., “Effects of organisational-level interventions at work on employees’ health: A systematic review,” BMC Public Health , 2014, Volume 14, Number 135.

Since many employers aren’t employing a systemic approach, many have weaker improvements in burnout and employee mental health and well-being than they would expect, given their investments.

Organizations pay a high price for failure to address workplace factors 11 Gunnar Aronsson et al., “A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms,” BMC Public Health , 2017, Volume 17, Article 264. that strongly correlate with burnout, 12 Sangeeta Agrawal and Ben Wigert, “Employee burnout, part 1: The 5 main causes,” Gallup, July 12, 2018. such as toxic behavior. 13 The high cost of a toxic workplace culture: How culture impacts the workforce — and the bottom line , Society for Human Resource Management, September 2019. A growing body of evidence, including our research in this report, sheds light on how burnout and its correlates may lead to costly organizational issues such as attrition. 14 Caio Brighenti et al., “Why every leader needs to worry about toxic culture,” MIT Sloan Management Review, March 16, 2022. Unprecedented levels of employee turnover—a global phenomenon we describe as the Great Attrition —make these costs more visible. Hidden costs to employers also include absenteeism, lower engagement, and decreased productivity. 15 Eric Garton, “Employee burnout is a problem with the company, not the person,” Harvard Business Review , April 6, 2017.

The McKinsey Health Institute: Join us!

The McKinsey Health Institute (MHI) is an enduring, non-profit-generating global entity within McKinsey. MHI strives to catalyze actions across continents, sectors, and communities to achieve material improvements in health, empowering people to lead their best possible lives. MHI is fostering a strong network of organizations committed to this aspiration, including employers globally who are committed to supporting the health of their workforce and broader communities.

MHI has a near-term focus on the urgent priority of mental health, with launch of a flagship initiative around employee mental health and well-being. By convening leading employers, MHI aims to collect global data, synthesize insights, and drive innovation at scale. Through collaboration, we can truly make a difference, learn together, and co-create solutions for workplaces to become enablers of health—in a way that is good for business, for employees, and for the communities in which they live.

To stay updated about MHI’s initiative on employee mental health and well-being sign up at McKinsey.com/mhi/contact-us .

In this article, we discuss findings of a recent McKinsey Health Institute (MHI) (see sidebar “The McKinsey Health Institute: Join us!”) global survey that sheds light on frequently overlooked workplace factors underlying employee mental health and well-being in organizations around the world. We conclude by teeing up eight questions for reflection along with recommendations on how organizations can address employee mental-health and well-being challenges by taking a systemic approach focused on changing the causes rather than the symptoms of poor outcomes. While there is no well-established playbook, we suggest employers can and should respond through interventions focused on prevention rather than remediation.

We are seeing persistent burnout challenges around the world

To better understand the disconnection between employer efforts and rising employee mental-health and well-being challenges (something we have observed since the start of the pandemic ), between February and April 2022 we conducted a global survey of nearly 15,000 employees and 1,000 HR decision makers in 15 countries. 16 Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The combined population of the selected countries correspond to approximately 70 percent of the global total.

The workplace dimensions assessed in our survey included toxic workplace behavior, sustainable work, inclusivity and belonging, supportive growth environment, freedom from stigma, organizational commitment, leadership accountability, and access to resources. 17 The associations of all these factors with employee health and well-being have been extensively explored in the academic literature. That literature heavily informed the development of our survey instrument. We have psychometrically validated this survey across 15 countries including its cross-cultural factorial equivalence. For certain outcome measures we collaborated with academic experts who kindly offered us their validated scales including the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT), the Distress Screener, and the Adaptability Scale referenced below. Those dimensions were analyzed against four work-related outcomes—intent to leave, work engagement, job satisfaction, and organization advocacy—as well as four employee mental-health outcomes—symptoms of anxiety, burnout, depression, and distress. 18 Instruments used were the Burnout Assessment Tool (Steffie Desart et al., User manual - Burnout assessment tool [BAT ] , - Version 2.0, July 2020) (burnout symptoms); Distress Screener (4DSQ; JR Anema et al., “Validation study of a distress screener,” Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation , 2009, Volume 19) (distress); GAD-2 assessment (Priyanka Bhandari et al., “Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 [GAD-2] and GAD-7 in a primary care setting,” Cureus , May 20, 2021, Volume 12, Number 5) (anxiety symptoms); and the PHQ-2 assessment (Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9 & PHQ-2], American Psychological Association) (depression symptoms). Individual adaptability was also assessed 19 In this article, “adaptability” refers to the “affective adaptability” which is one sub-dimension of The Adaptability Scale instrument (Michel Meulders and Karen van Dam, “The adaptability scale: Development, internal consistency, and initial validity evidence,” European Journal of Psychological Assessment , 2020, Volume 37, Number 2). (see sidebar “What we measured”).

What we measured

Workplace factors assessed in our survey included:

- Toxic workplace behavior: Employees experience interpersonal behavior that leads them to feel unvalued, belittled, or unsafe, such as unfair or demeaning treatment, noninclusive behavior, sabotaging, cutthroat competition, abusive management, and unethical behavior from leaders or coworkers.

- Inclusivity and belonging: Organization systems, leaders, and peers foster a welcoming and fair environment for all employees to be themselves, find connection, and meaningfully contribute.

- Sustainable work: Organization and leaders promote work that enables a healthy balance between work and personal life, including a manageable workload and work schedule.

- Supportive growth environment: Managers care about employee opinions, well-being, and satisfaction and provide support and enable opportunities for growth.

- Freedom from stigma and discrimination: Freedom from the level of shame, prejudice, or discrimination employees perceive toward people with mental-health or substance-use conditions.

- Organizational accountability: Organization gathers feedback, tracks KPIs, aligns incentives, and measures progress against employee health goals.

- Leadership commitment: Leaders consider employee mental health a top priority, publicly committing to a clear strategy to improve employee mental health.

- Access to resources: Organization offers easy-to-use and accessible resources that fit individual employee needs related to mental health. 1 Including adaptability and resilience-related learning and development resources.

Health outcomes assessed in our survey included:

- Burnout symptoms: An employee’s experience of extreme tiredness, reduced ability to regulate cognitive and emotional processes, and mental distancing (Burnout Assessment Tool). 2 Burnout Assessment Tool, Steffie Desart et al., “User manual - Burnout assessment tool (BAT), - Version 2.0,” July 2020.

- Distress: An employee experiencing a negative stress response, often involving negative affect and physiological reactivity (4DSQ Distress Screener). 3 Distress screener, 4DSQ; JR Anema et al., “Validation study of a distress screener,” Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation , 2009, Volume 19.

- Depression symptoms: An employee having little interest or pleasure in doing things, and feeling down, depressed, or hopeless (PHQ-2 Screener). 4 Kurt Kroenke et al., “The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener,” Medical Care , November 2003, Volume 41, Issue 11.

- Anxiety symptoms: An employee’s feelings of nervousness, anxiousness, or being on edge, and not being able to stop or control worrying (GAD-2 Screener). 5 Kurt Kroenke et al., “Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection,” Annals of Internal Medicine , March 6, 2007, Volume 146, Issue 5.

Work-related outcomes assessed in our survey included:

- Intent to leave: An employee’s desire to leave the organization in which they are currently employed in the next three to six months.

- Work engagement: An employee’s positive motivational state of high energy combined with high levels of dedication and a strong focus on work.

- Organizational advocacy: An employee’s willingness to recommend or endorse their organization as a place to work to friends and relatives.

- Work satisfaction: An employee’s level of contentment or satisfaction with their current job.

Our survey pointed to a persistent disconnection between how employees and employers perceive mental health and well-being in organizations. We see an average 22 percent gap between employer and employee perceptions—with employers consistently rating workplace dimensions associated with mental health and well-being more favorably than employees. 20 Our survey did not link employers and employees’ responses. Therefore, these numbers are indicative of a potential gap that could be found within companies.

In this report—the first of a broader series on employee mental health from the McKinsey Health Institute—we will focus on burnout, its workplace correlates, and implications for leaders. On average, one in four employees surveyed report experiencing burnout symptoms. 21 Represents global average of respondents experiencing burnout symptoms (per items from Burnout Assessment Tool) sometimes, often, or always. These high rates were observed around the world and among various demographics (Exhibit 1), 22 Our survey findings demonstrate small but statistically significant differences between men and women, with women reporting higher rates of burnout symptoms (along with symptoms of distress, depression, and anxiety). Differences between demographic variables across countries will be discussed in our future publications. and are consistent with global trends. 23 Ashley Abramson, “Burnout and stress are everywhere,” Monitor on Psychology , January 1, 2022, Volume 53, Number 1.

So, what is behind pervasive burnout challenges worldwide? Our research suggests that employers are overlooking the role of the workplace in burnout and underinvesting in systemic solutions.

Employers tend to overlook the role of the workplace in driving employee mental health and well-being, engagement, and performance

In all 15 countries and across all dimensions assessed, toxic workplace behavior was the biggest predictor of burnout symptoms and intent to leave by a large margin 24 Measured as a function of predictive power of the dimensions assessed; predictive power was estimated based on share of outcome variability associated with each dimension; based on regression models applied to cross-sectional data (that is, measured at one point in time), rather than longitudinal data (that is, measured over time); causal relationships have not been established. —predicting more than 60 percent of the total global variance. For positive outcomes (including work engagement, job satisfaction, and organization advocacy), the impact of factors assessed was more distributed—with inclusivity and belonging, supportive growth environment, sustainable work, and freedom from stigma predicting most outcomes (Exhibit 2).

In all 15 countries and across all dimensions assessed, toxic workplace behavior had the biggest impact predicting burnout symptoms and intent to leave by a large margin.

The danger of toxic workplace behavior—and its impact on burnout and attrition

Across the 15 countries in the survey, toxic workplace behavior is the single largest predictor of negative employee outcomes, including burnout symptoms (see sidebar “What is toxic workplace behavior?”). One in four employees report experiencing high rates of toxic behavior at work. At a global level, high rates were observed across countries, demographic groups—including gender, organizational tenure, age, virtual/in-person work, manager and nonmanager roles—and industries. 25 Differences between demographic variables across countries will be discussed in our future articles.

What is toxic workplace behavior?

Toxic workplace behavior is interpersonal behavior that leads to employees feeling unvalued, belittled, or unsafe, such as unfair or demeaning treatment, non-inclusive behavior, sabotaging, cutthroat competition, abusive management, and unethical behavior from leaders or coworkers. Selected questions from this dimension include agreement with the statements “My manager ridicules me,” “I work with people who belittle my ideas,” and “My manager puts me down in front of others.”

Toxic workplace behaviors are a major cost for employers—they are heavily implicated in burnout, which correlates with intent to leave and ultimately drives attrition. In our survey, employees who report experiencing high levels of toxic behavior 26 “High” represents individuals in the top quartile of responses and “low” represents individuals in the bottom quartile of responses. at work are eight times more likely to experience burnout symptoms (Exhibit 3). In turn, respondents experiencing burnout symptoms were six times more likely to report they intend to leave their employers in the next three to six months (consistent with recent data pointing to toxic culture as the single largest predictor of resignation during the Great Attrition, ten times more predictive than compensation alone 27 Charles Sull et al., “Toxic culture is driving the Great Resignation,” MIT Sloan Management Review, January 11, 2022. and associated with meaningful organizational costs 28 Rasmus Hougaard, “To stop the Great Resignation, we must fight dehumanization at work,” Potential Project, 2022. ). The opportunity for employers is clear. Studies show that intent to leave may correlate with two- to three-times higher 29 Bryan Bohman et al., “Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: A case study,” BMC Health Services Research , November 27, 2018, Volume 18, Number 1. rates of attrition; conservative estimates of the cost of replacing employees range from one-half to two times their annual salary. Even without accounting for costs associated with burnout—including organizational commitment 30 Michael Leiter and Christina Maslach, “The impact of interpersonal environment on burnout and organizational commitment,” Journal of Organizational Behavior , October 1988, Volume 9, Number 4. and higher rates of sick leave and absenteeism 31 Arnold B. Bakker et al., “Present but sick: A three-wave study on job demands, presenteeism and burnout,” Career Development International , 2009, Volume 14, Number 1. —the business case for addressing it is compelling. The alternative—not addressing it—can lead to a downward spiral in individual and organizational performance. 32 Arnold B. Bakker et al., “Present but sick: A three-wave study on job demands, presenteeism and burnout,” Career Development International , 2009, Volume 14, Number 1.

Individuals’ resilience and adaptability skills may help but do not compensate for the impact of a toxic workplace

Toxic behavior is not an easy challenge to address. Some employers may believe the solution is simply training people to become more resilient.

There is merit in investing in adaptability and resiliency skill building . Research indicates that employees who are more adaptable tend to have an edge in managing change and adversity. 33 Karen van Dam, “Employee adaptability to change at work: A multidimensional, resource-based framework,” from The Psychology of Organizational Change: Viewing Change from the Employee’s Perspective , Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2013; Jacqueline Brassey et al., Advancing Authentic Confidence Through Emotional Flexibility: An Evidence-Based Playbook of Insights, Practices and Tools to Shape Your Future , second edition, Morrisville, NC: Lulu Press, 2019; B+B Vakmedianet B.V. Zeist, Netherlands (to be published Q3 2022). We see that edge reflected in our survey findings: adaptability acts as a buffer 34 Estimated buffering effect illustrated in Exhibit 4. to the impact of damaging workplace factors (such as toxic behaviors), while magnifying the benefit of supportive workplace factors (such as a supportive growth environment) (Exhibit 4). In a recent study, employees engaging in adaptability training experienced three times more improvement in leadership dimensions and seven times more improvement in self-reported well-being than those in the control group. 35 McKinsey’s People and Organization Performance - Adaptability Learning Program; multirater surveys showed improvements in adaptability outcomes, including performance in role, sustainment of well-being, successfully adapting to unplanned circumstances and change, optimism, development of new knowledge and skills; well-being results were based on self-reported progress as a result of the program.

However, employers who see building resilience and adaptability skills in individuals as the sole solution to toxic behavior and burnout challenges are misguided. Here is why.

Individual skills cannot compensate for unsupportive workplace factors. When it comes to the effect of individual skills, leaders should be particularly cautious not to misinterpret “favorable” outcomes (for example, buffered impact of toxic behaviors across more adaptable employees) as absence of underlying workplace issues that should be addressed. 36 Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, “To prevent burnout, hire better bosses,” Harvard Business Review , August 23, 2019.

Also, while more adaptable employees are better equipped to work in poor environments, they are less likely to tolerate them. In our survey, employees with high adaptability were 60 percent more likely to report intent to leave their organization if they experienced high levels of toxic behavior at work than those with low adaptability (which may possibly relate to a higher level of self-confidence 37 Brassey et al. found that as a result of a learning program, employees who developed emotional flexibility skills, a concept related to affective adaptability but also strongly linked to connecting with purpose, developed a higher self-confidence over time; Jacqueline Brassey et al., “Emotional flexibility and general self-efficacy: A pilot training intervention study with knowledge workers,” PLOS ONE , October 14, 2020, Volume 15, Number 10. ). Therefore, relying on improving employee adaptability without addressing broader workplace factors puts employers at an even higher risk of losing some of its most resilient, adaptable employees.

Employees with high adaptability were 60 percent more likely to report intent to leave their organization if they experienced high levels of toxic behavior at work than those with low adaptability.

What this means for employers: Why organizations should take a systemic approach to improving employee mental health and well-being

We often think of employee mental health, well-being, and burnout as a personal problem. That’s why most companies have responded to symptoms by offering resources focused on individuals such as wellness programs.

However, the findings in our global survey and research are clear. Burnout is experienced by individuals, but the most powerful drivers of burnout are systemic organizational imbalances across job demands and job resources. So, employers can and should view high rates of burnout as a powerful warning sign that the organization—not the individuals in the workforce—needs to undergo meaningful systematic change.

Employers can and should view high rates of burnout as a powerful warning sign that the organization—not the individuals in the workforce—needs to undergo meaningful systematic change.

Taking a systemic approach means addressing both toxic workplace behavior and redesigning work to be inclusive, sustainable, and supportive of individual learning and growth, including leader and employee adaptability skills. It means rethinking organizational systems, processes, and incentives to redesign work, job expectations, and team environments.

As an employer, you can’t “yoga” your way out of these challenges. Employers who try to improve burnout without addressing toxic behavior are likely to fail. Our survey shows that improving all other organization factors assessed (without addressing toxic behavior) does not meaningfully improve reported levels of burnout symptoms. Yet, when toxic behavior levels are low, each additional intervention contributes to reducing negative outcomes and increasing positive ones.

The interactive graphic shows the estimated interplay between the drivers and outcomes, based on our survey data (Exhibit 5).

Taking a preventative, systemic approach—focused on addressing the roots of the problem (as opposed to remediating symptoms)—is hard. But the upside for employers is a far greater ability to attract and retain valuable talent over time.

The good news: Although there are no silver bullets, there are opportunities for leaders to drive material change

We see a parallel between the evolution of global supply chains and talent. Many companies optimized supply chains for “just in time” delivery, and talent was optimized to drive operational efficiency and effectiveness. As supply chains come under increasing pressure, many companies recognize the need to redesign and optimize supply chains for resilience and sustainability, and the need to take an end-to-end approach to the solutions. The same principles apply to talent.

We acknowledge that the factors associated with improving employee mental health and well-being (including organizational-, team-, and individual-level factors) are numerous and complex. And taking a whole-systems approach is not easy.

Would you like to learn more about the McKinsey Health Institute ?

Despite the growing momentum toward better employee mental health and well-being (across business and academic communities), we’re still early on the journey. We don’t yet have sufficient evidence to conclude which interventions work most effectively—or a complete understanding of why they work and how they affect return on investment.

That said, efforts to mobilize the organization to rethink work—in ways that are compatible with both employee and employer goals—are likely to pay off in the long term. To help spark that conversation in your organization, we offer eight targeted questions and example strategies with the potential to address some of the burnout-related challenges discussed in this article.

Do we treat employee mental health and well-being as a strategic priority?