Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on August 2, 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on March 18, 2024.

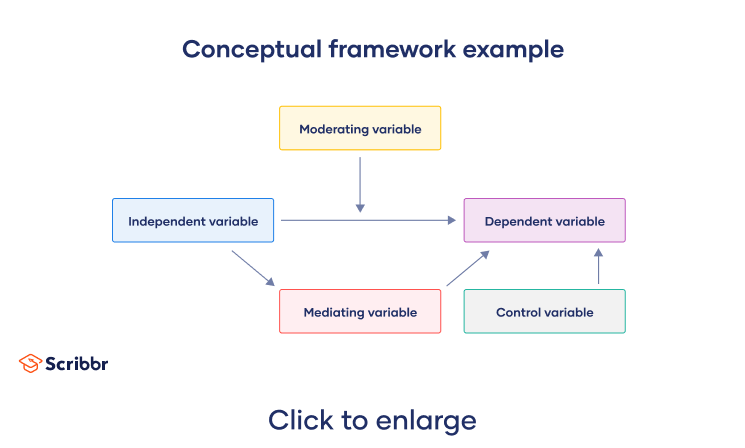

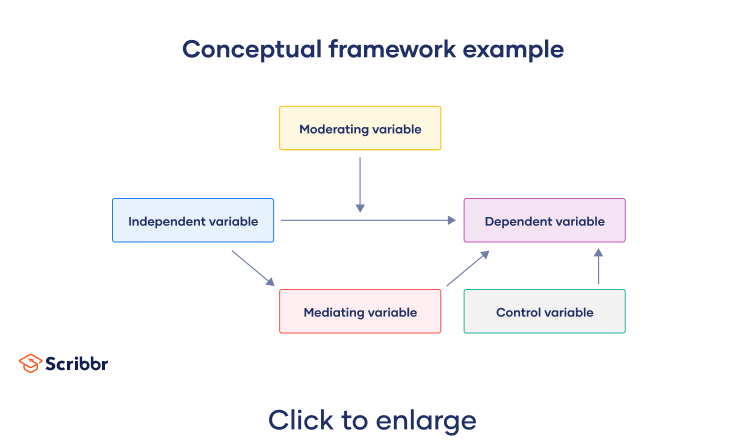

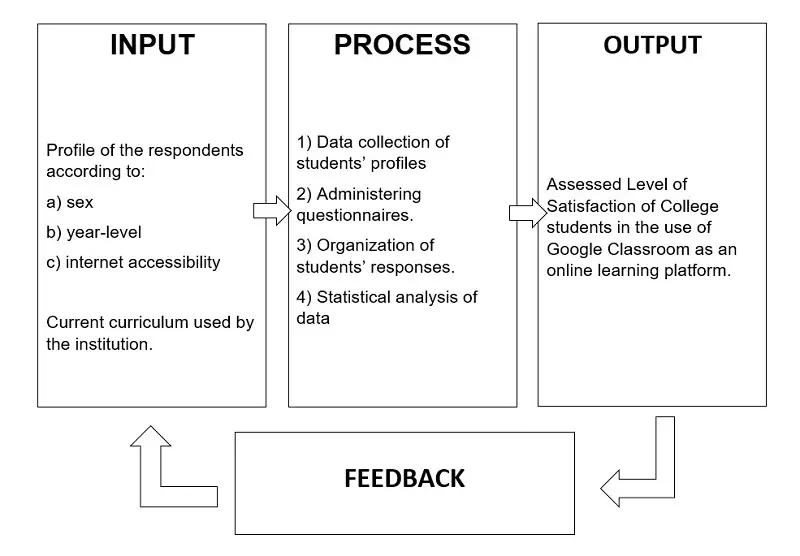

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualize your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

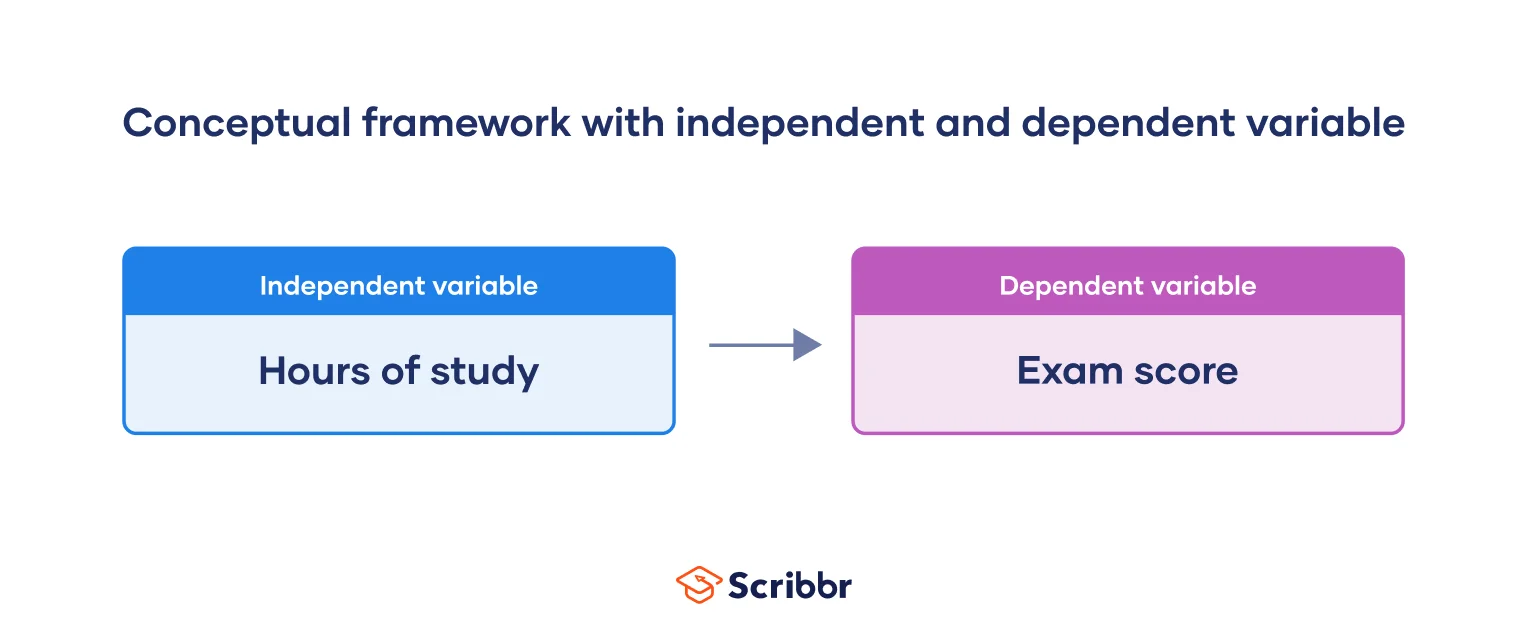

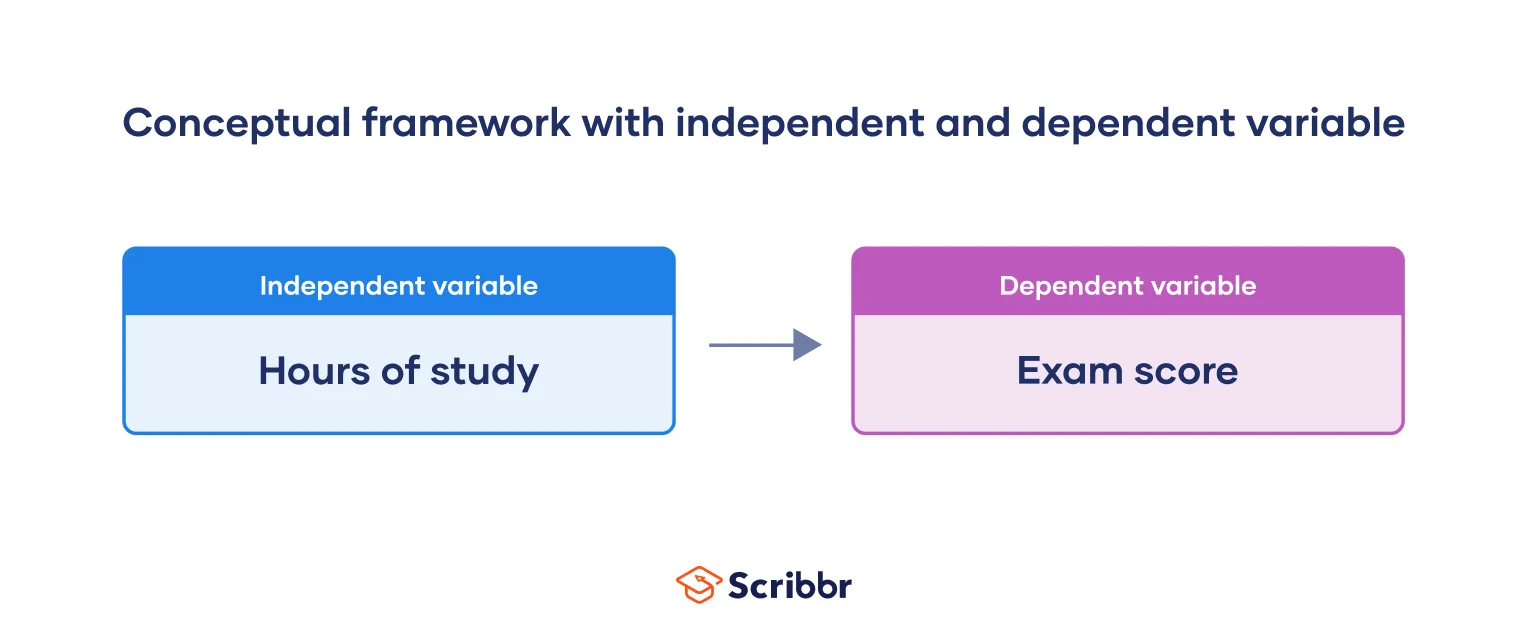

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, “hours of study,” is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, “exam score,” is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (“hours of study”).

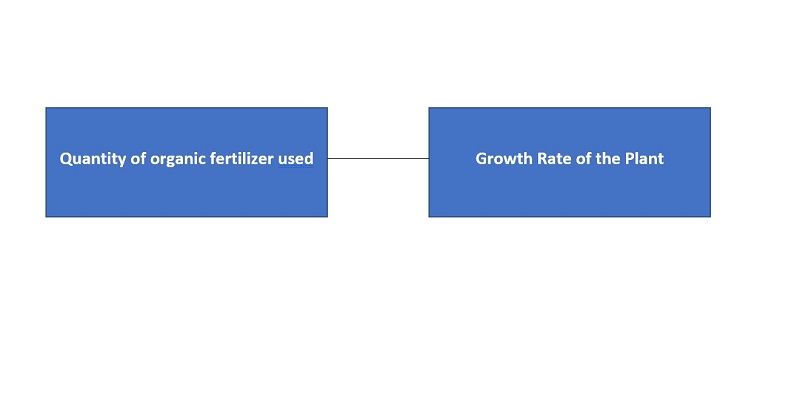

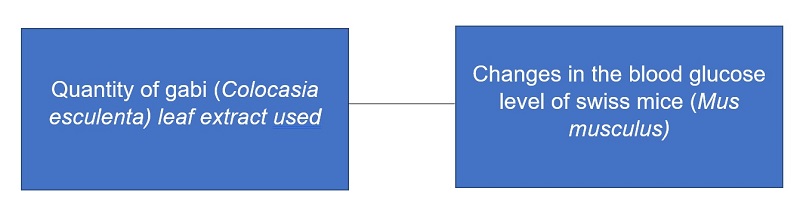

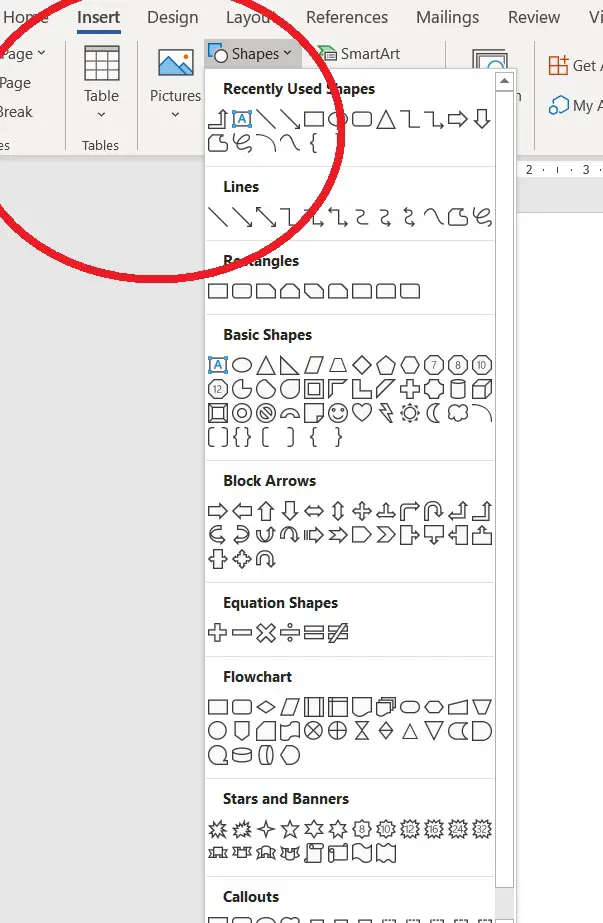

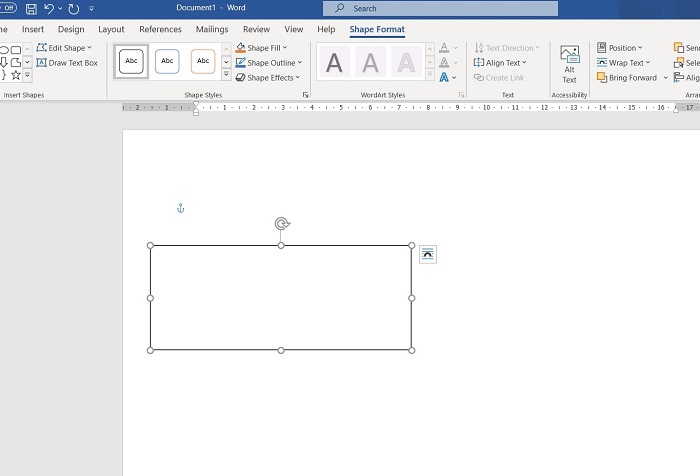

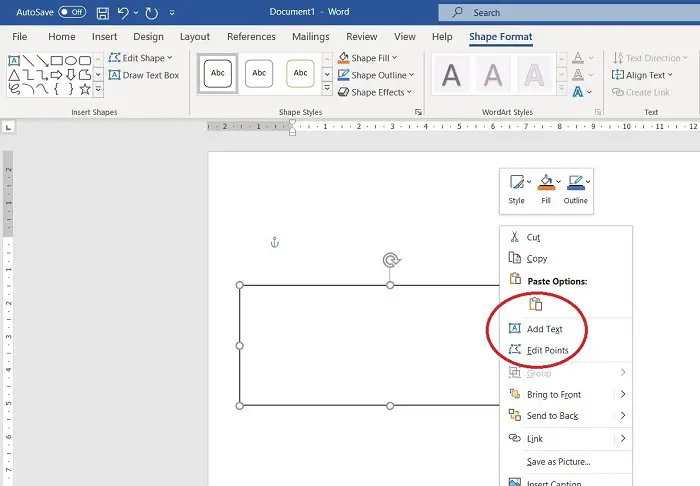

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualizing your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

We demonstrate this using basic design components of boxes and arrows. Here, each variable appears in a box. To indicate a causal relationship, each arrow should start from the independent variable (the cause) and point to the dependent variable (the effect).

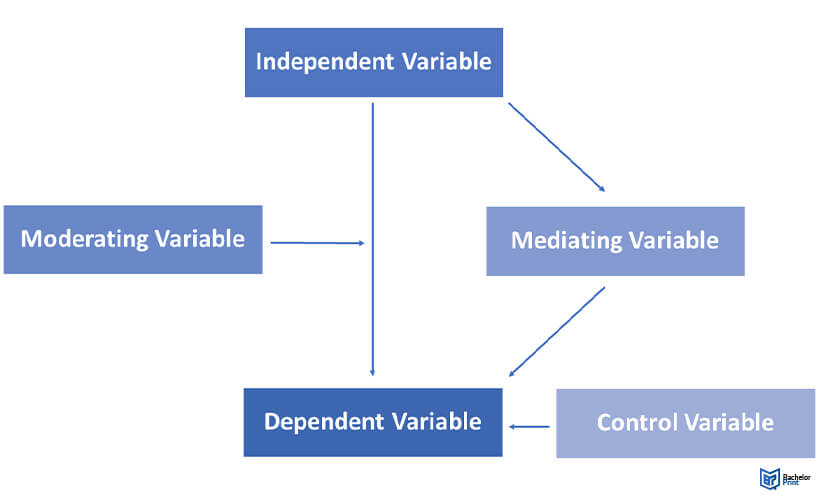

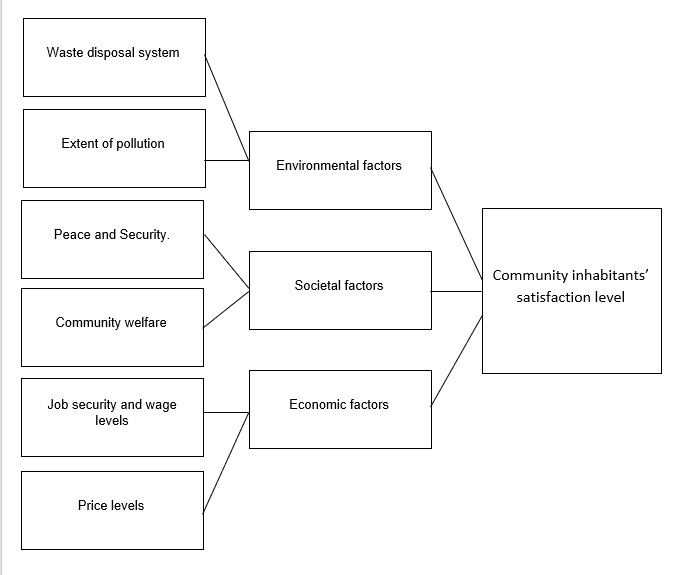

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

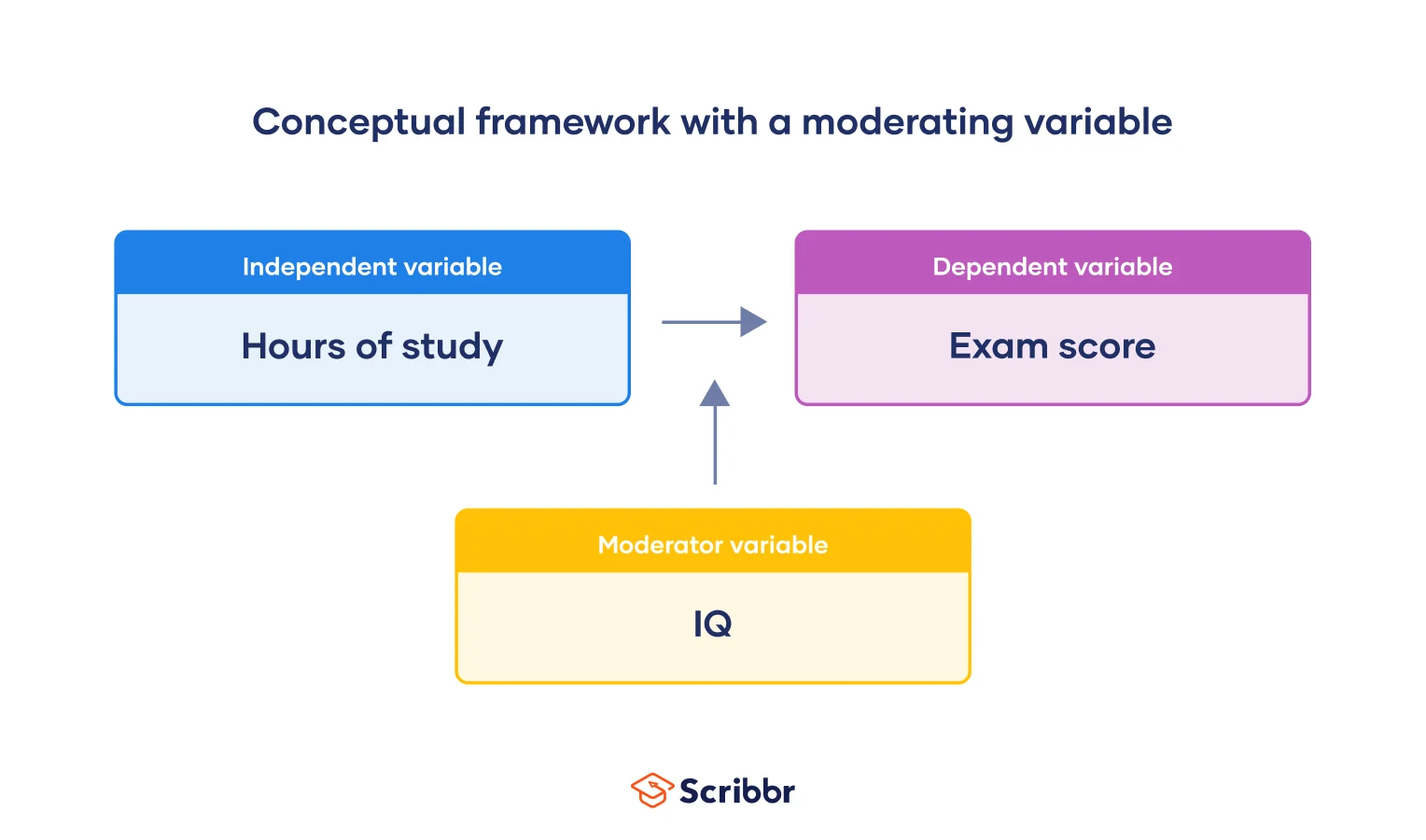

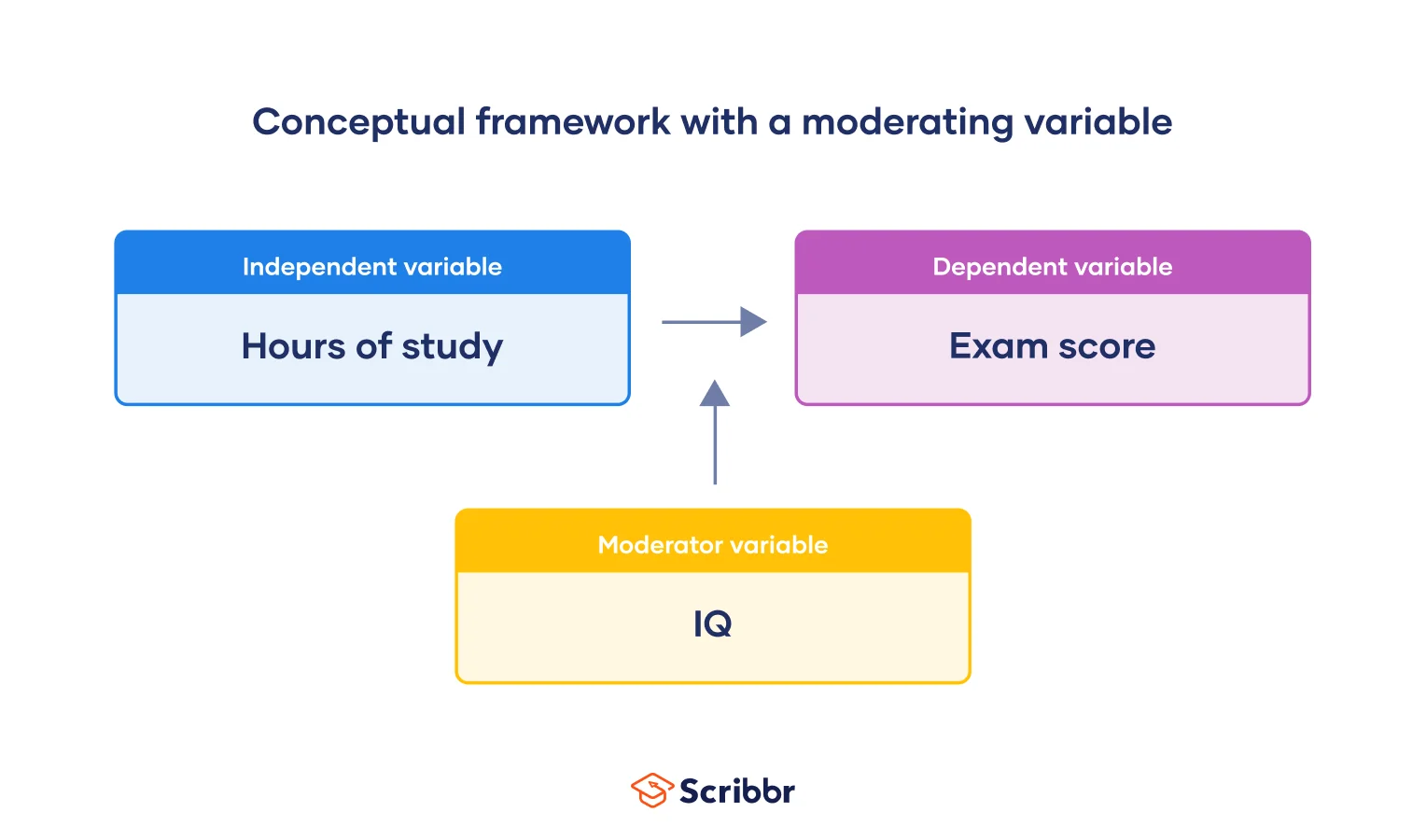

Moderating variables

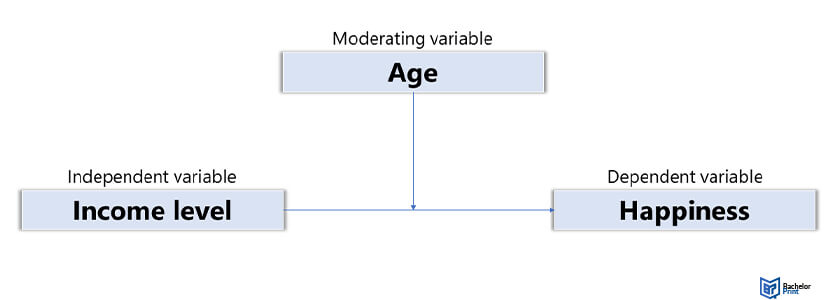

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the “effect” component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator “IQ.” Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable “hours of study” has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

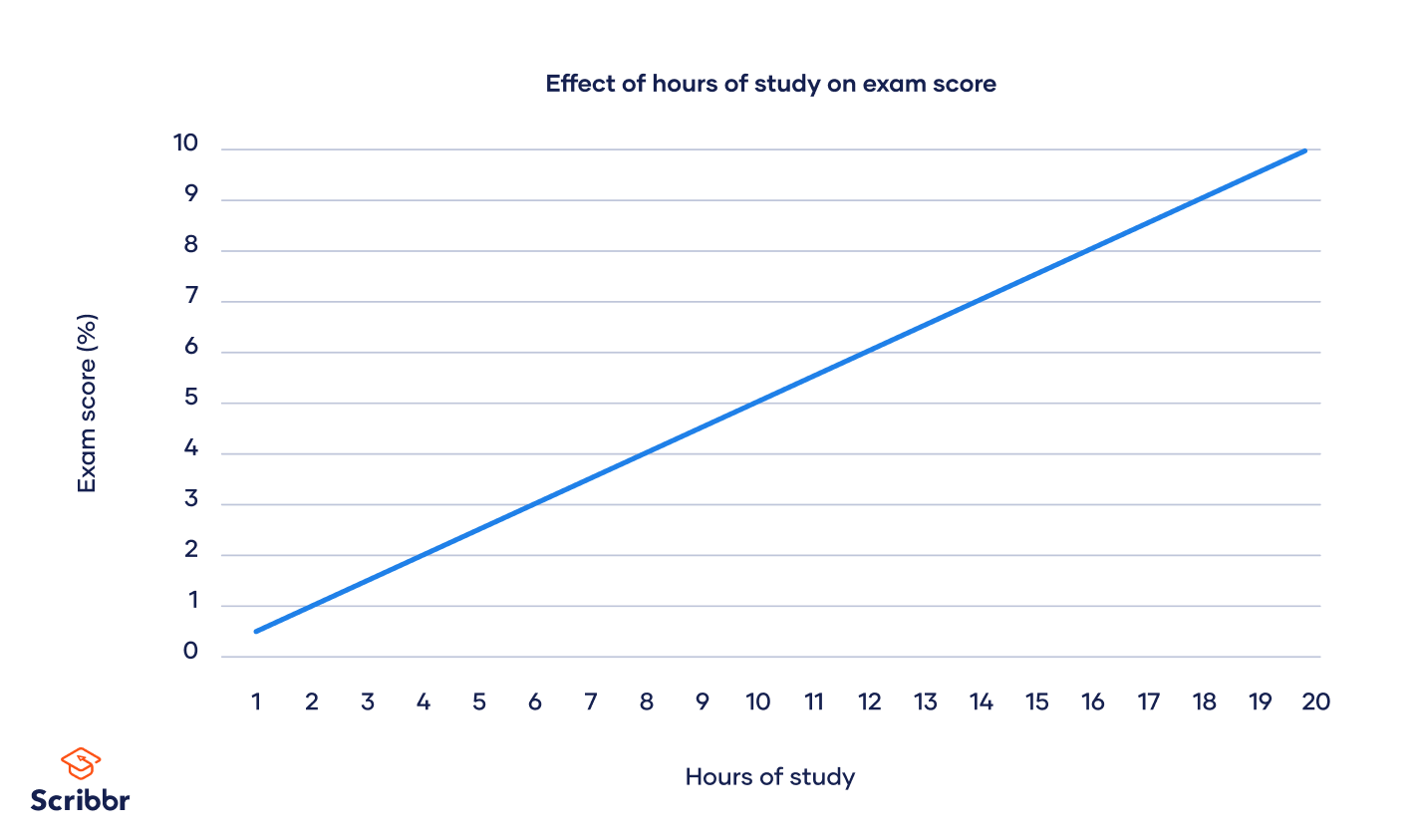

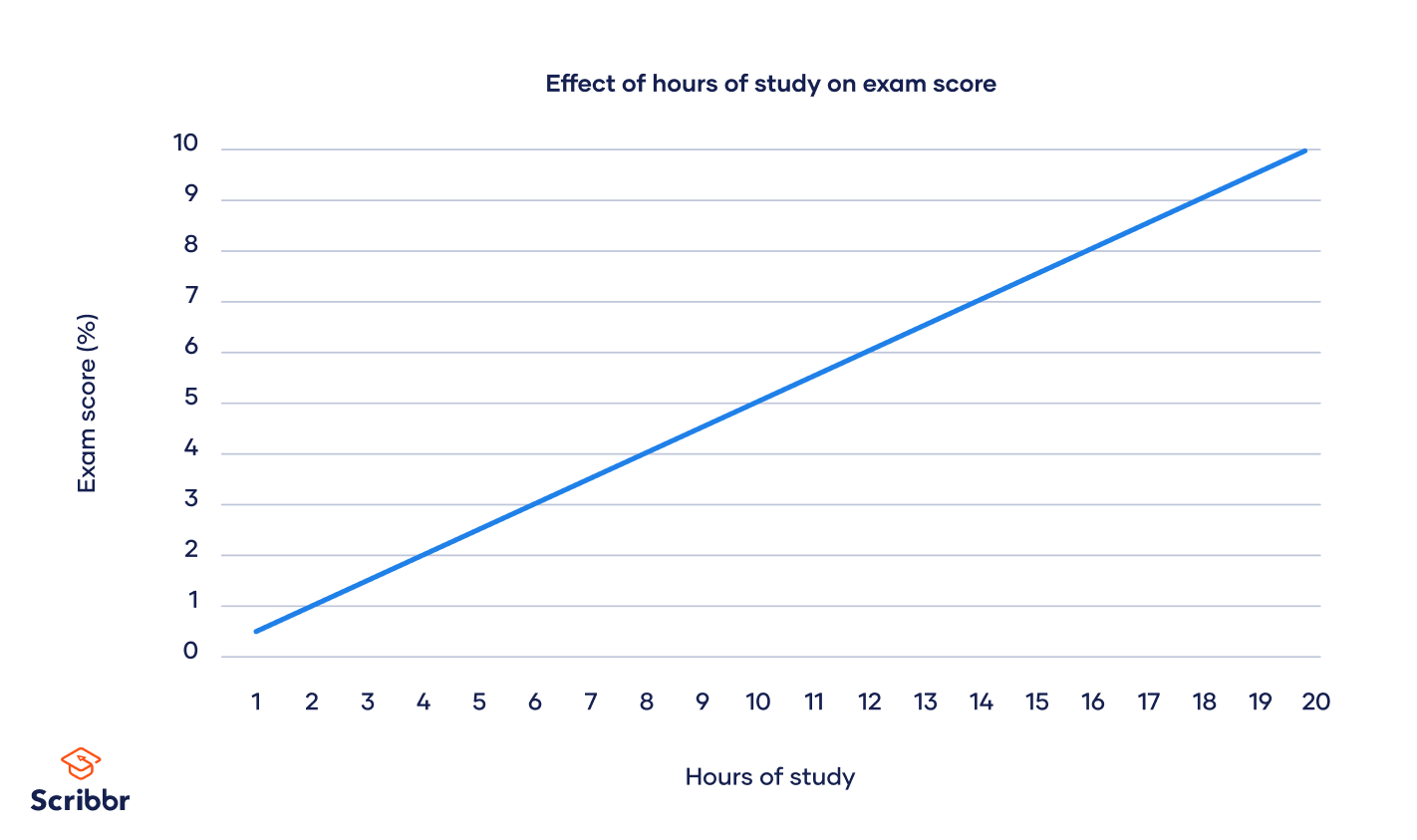

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

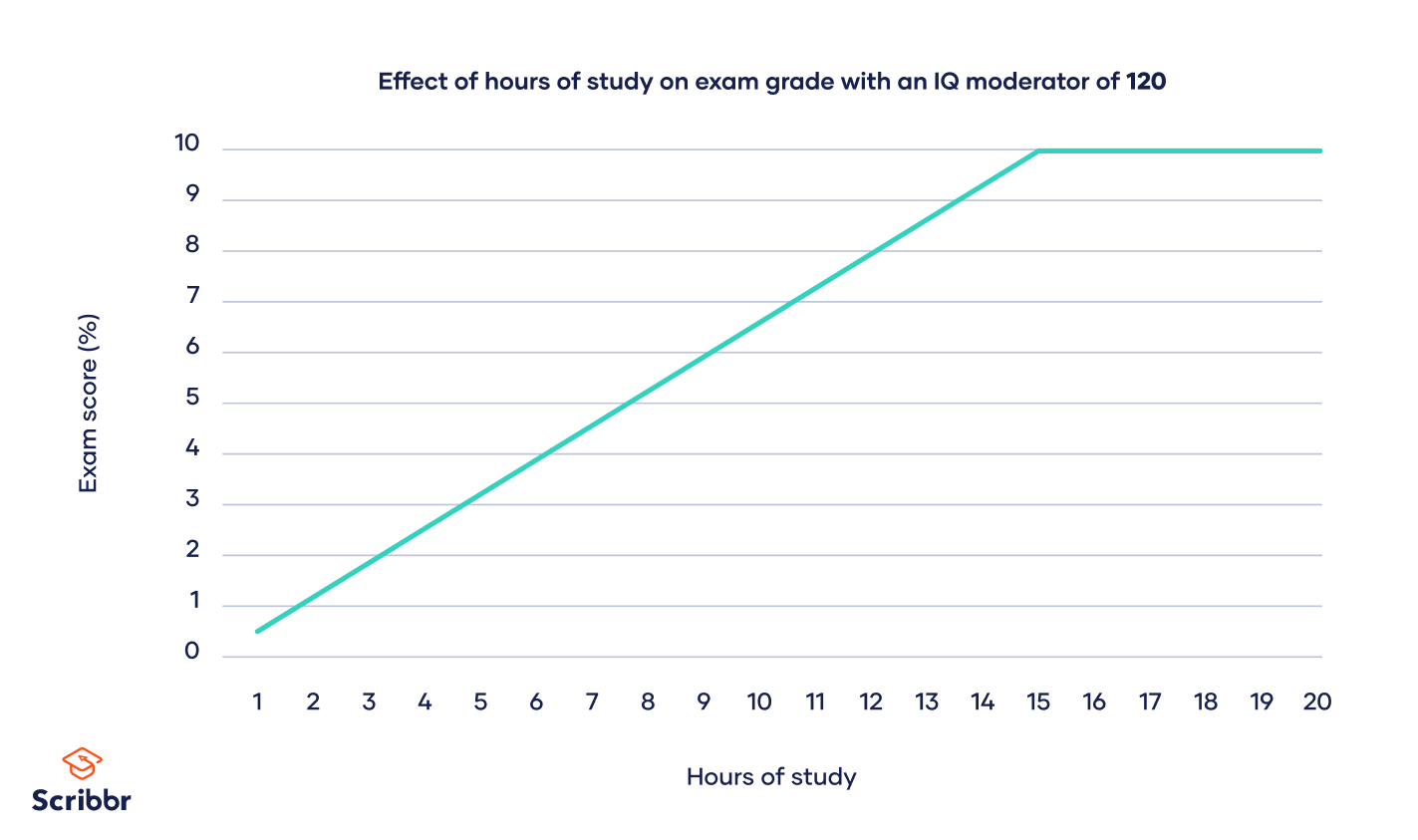

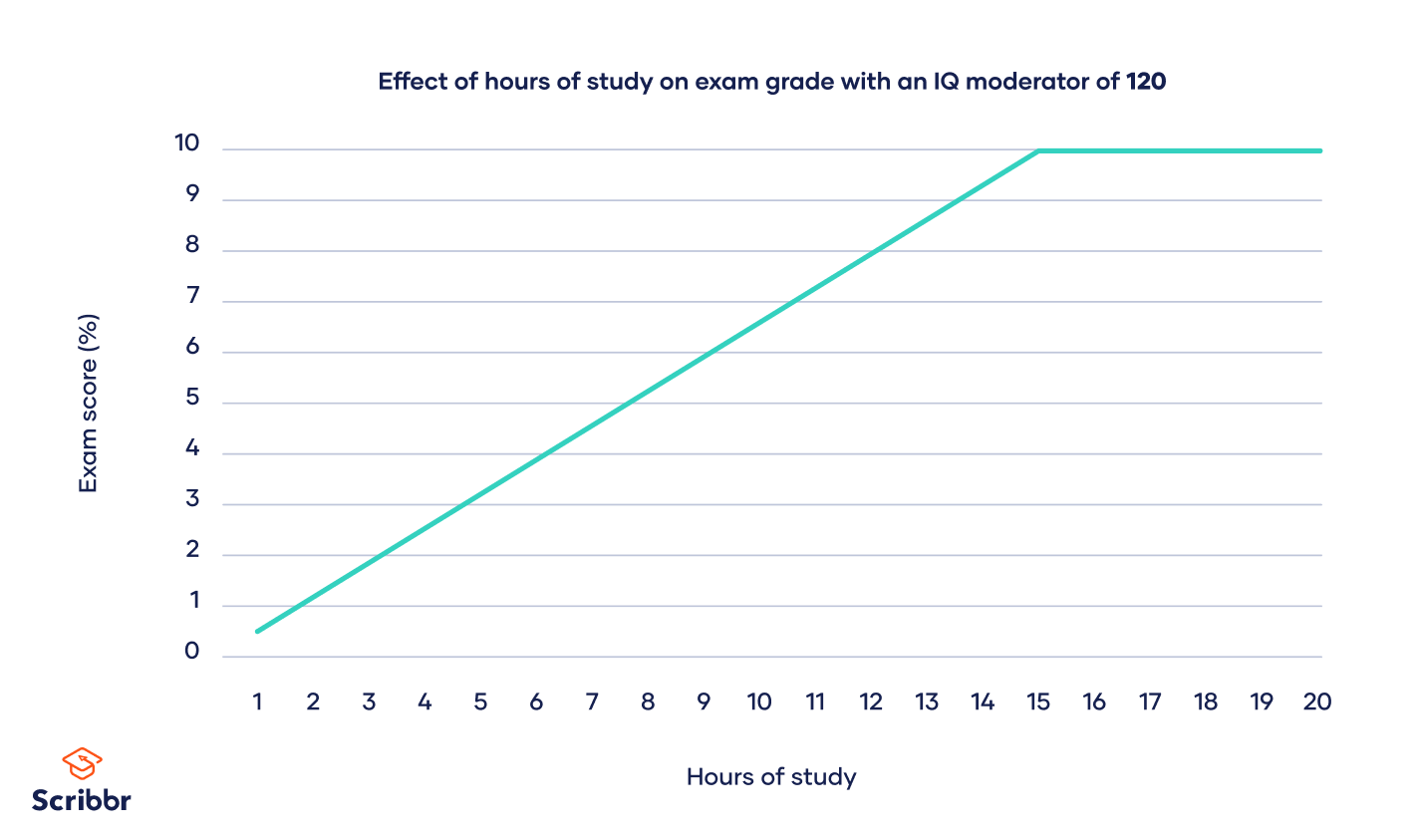

But the graph looks different when we add our “IQ” moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

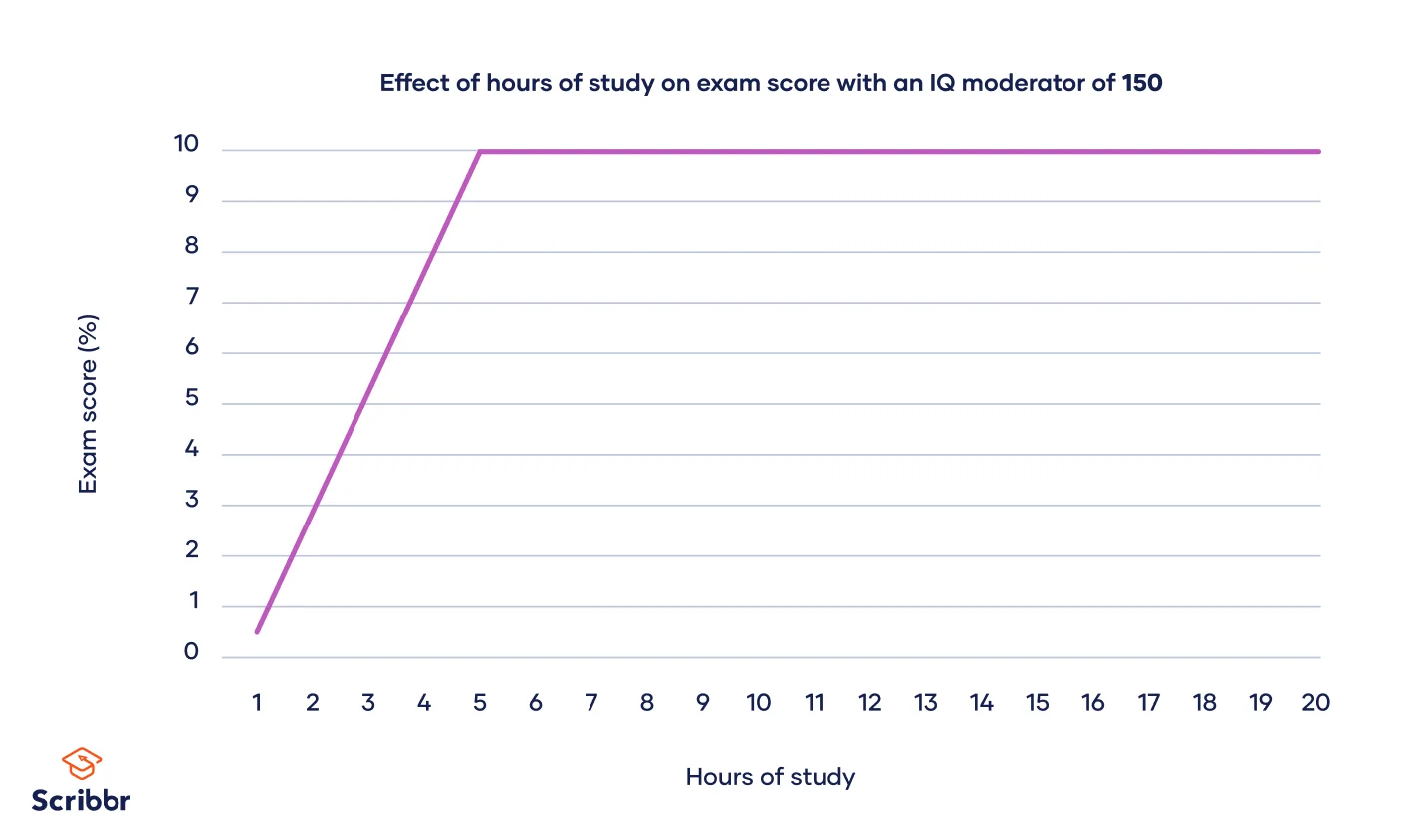

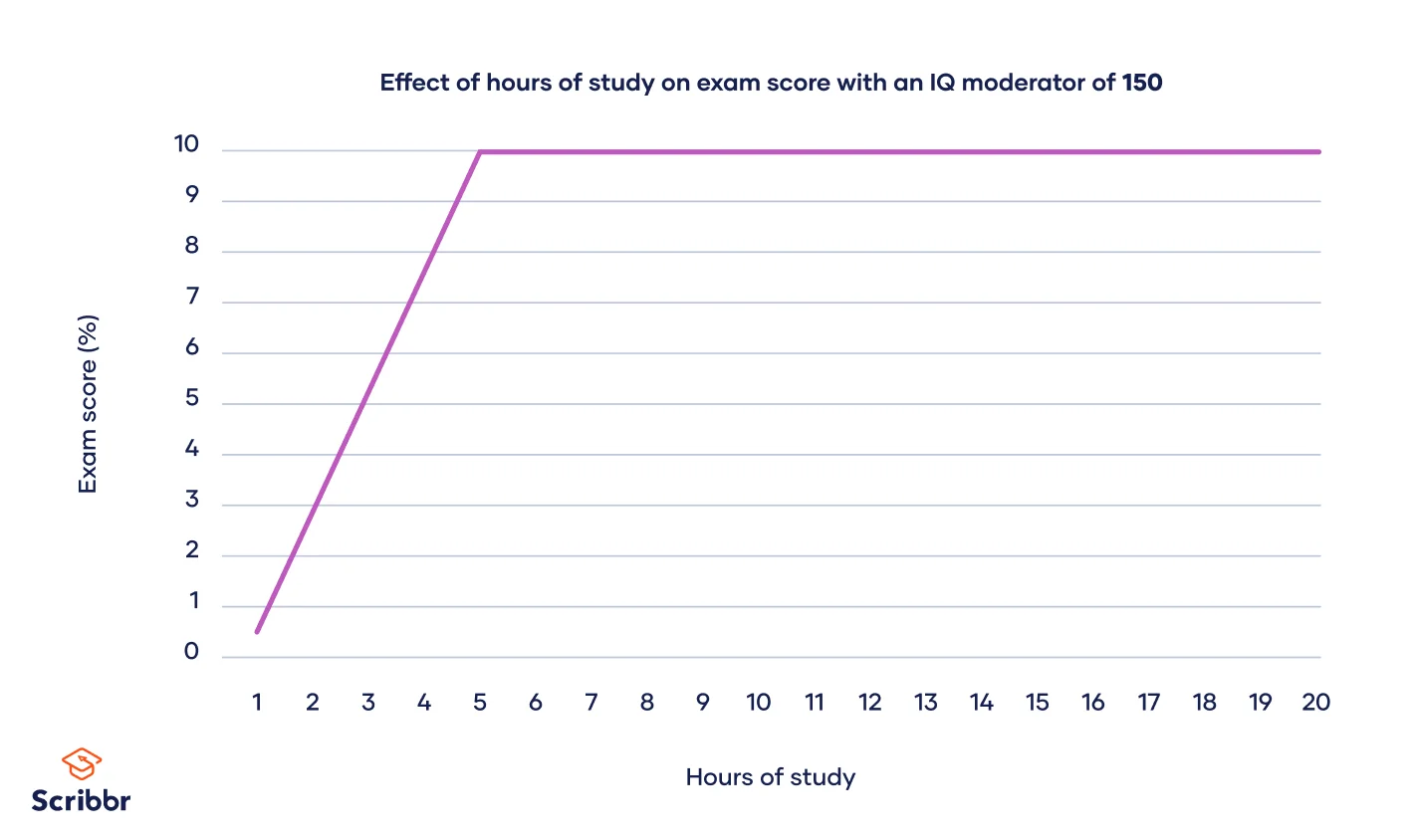

Below, the value of the “IQ” moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

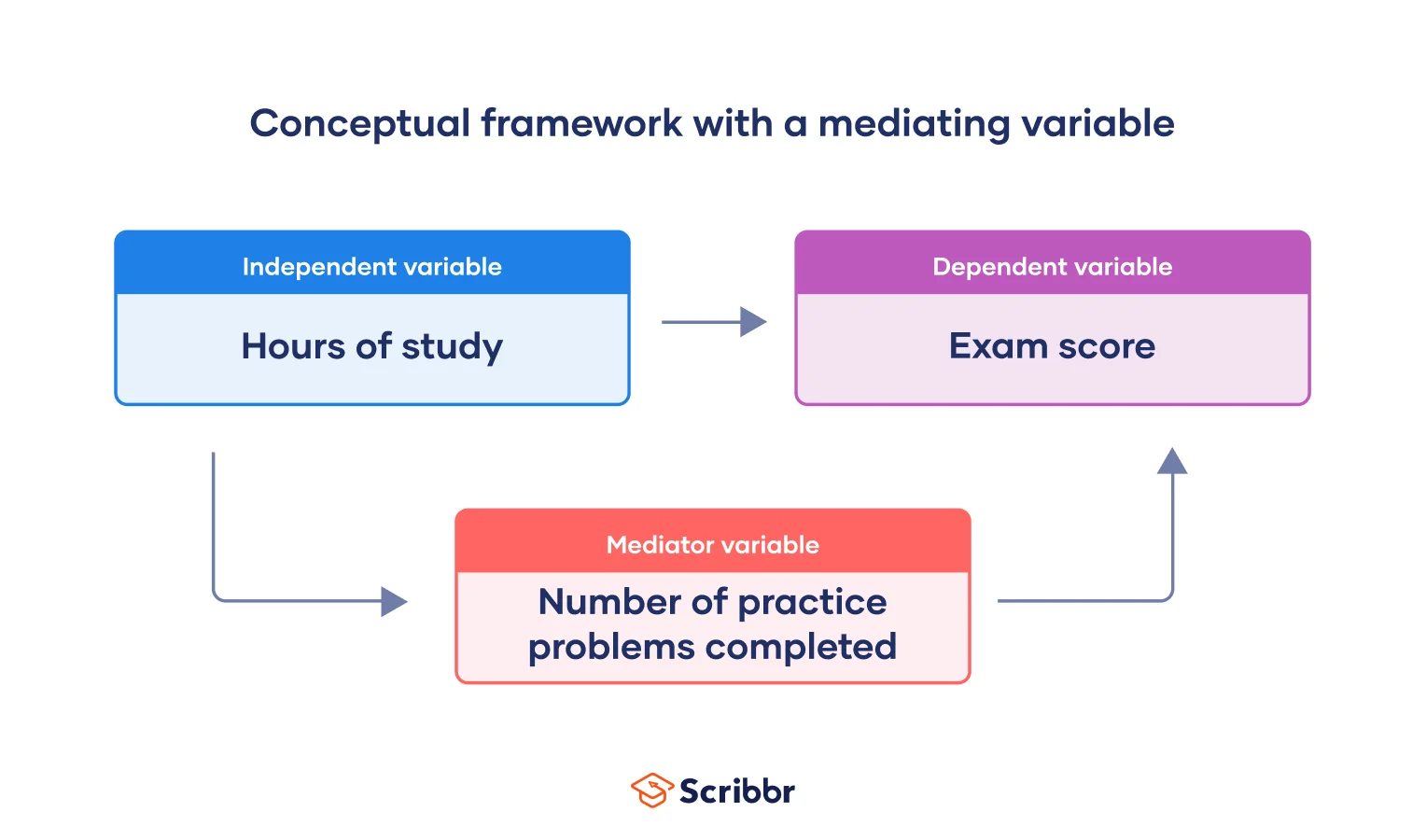

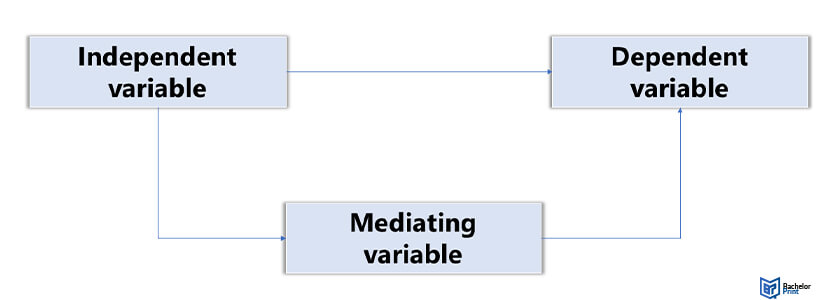

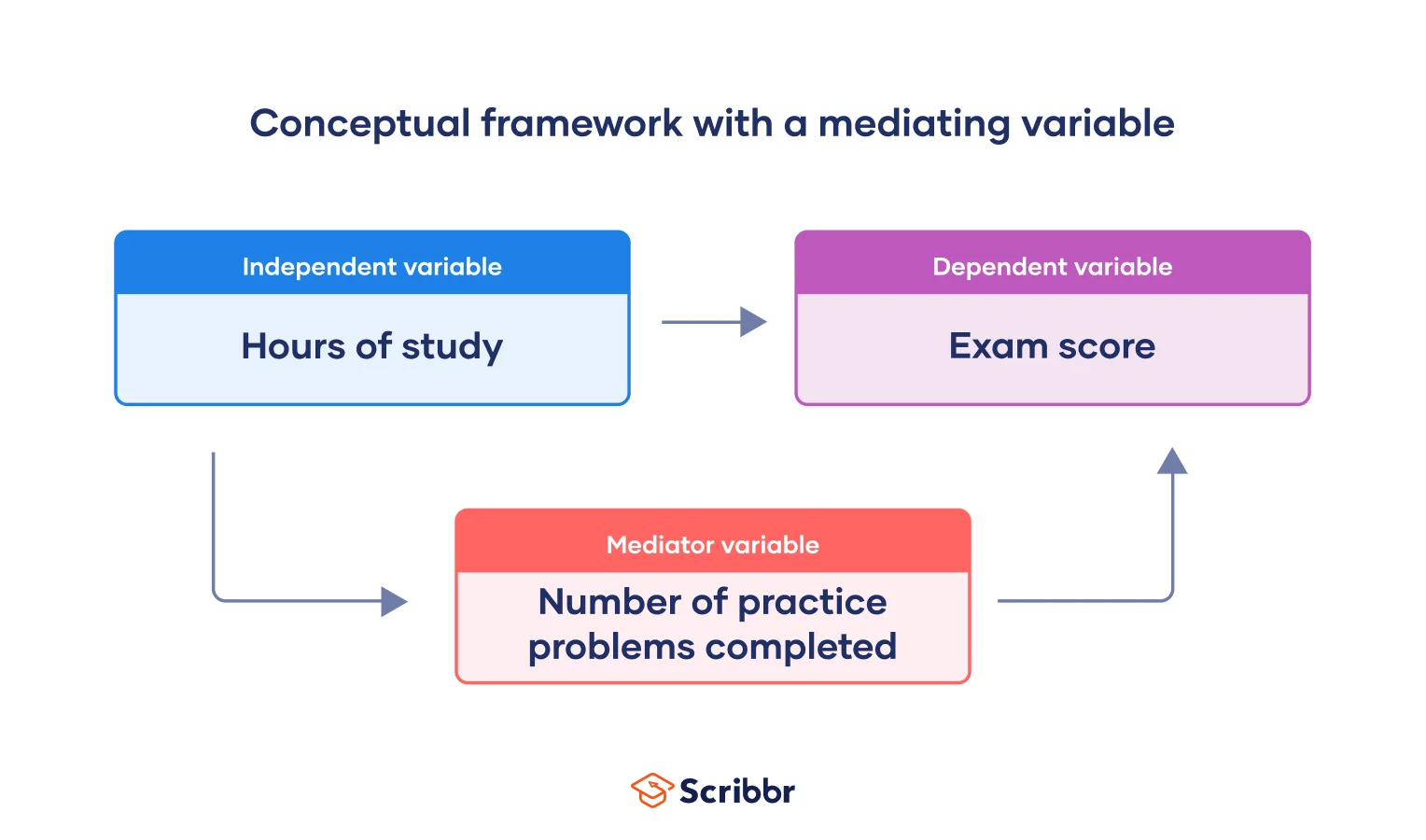

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs. mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

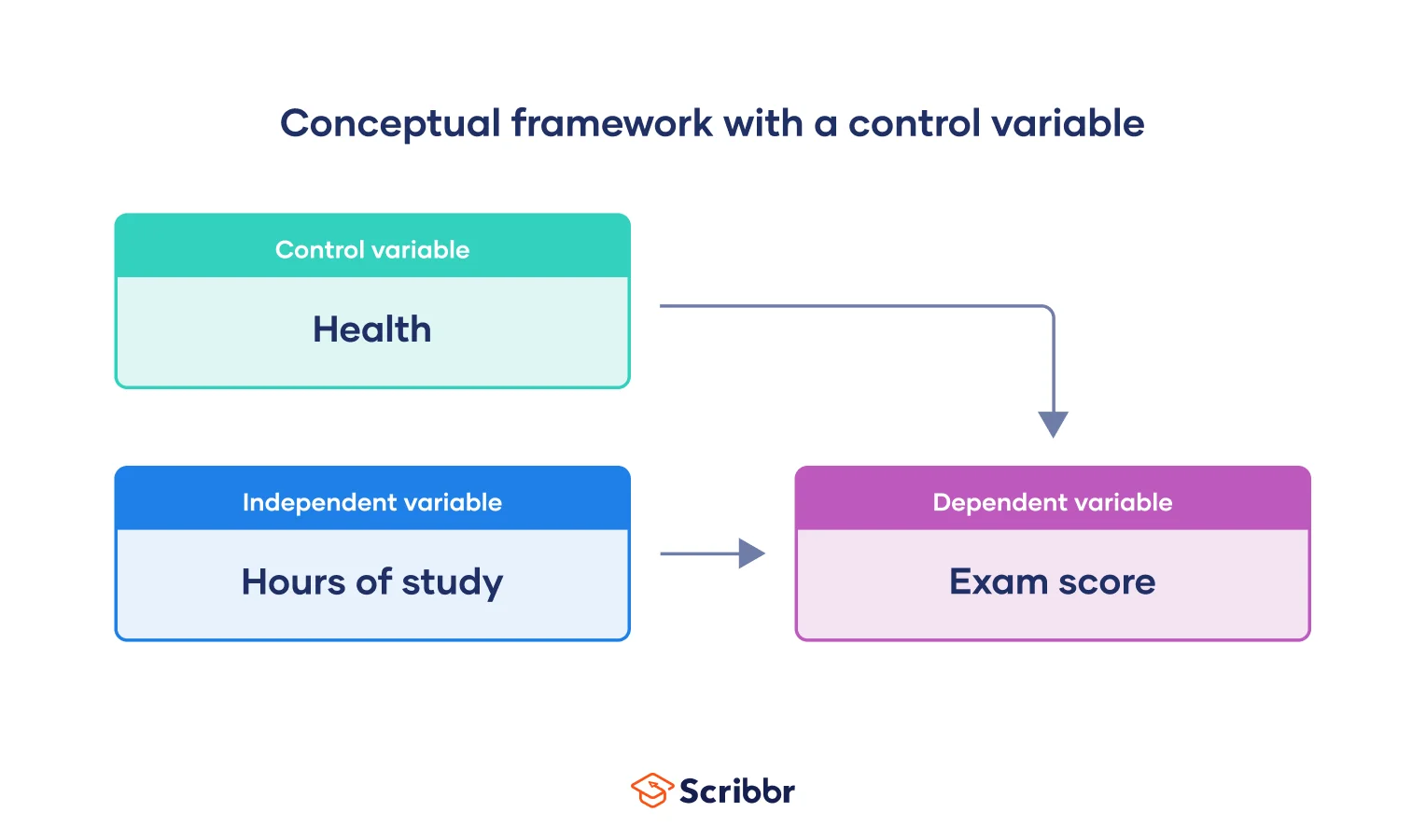

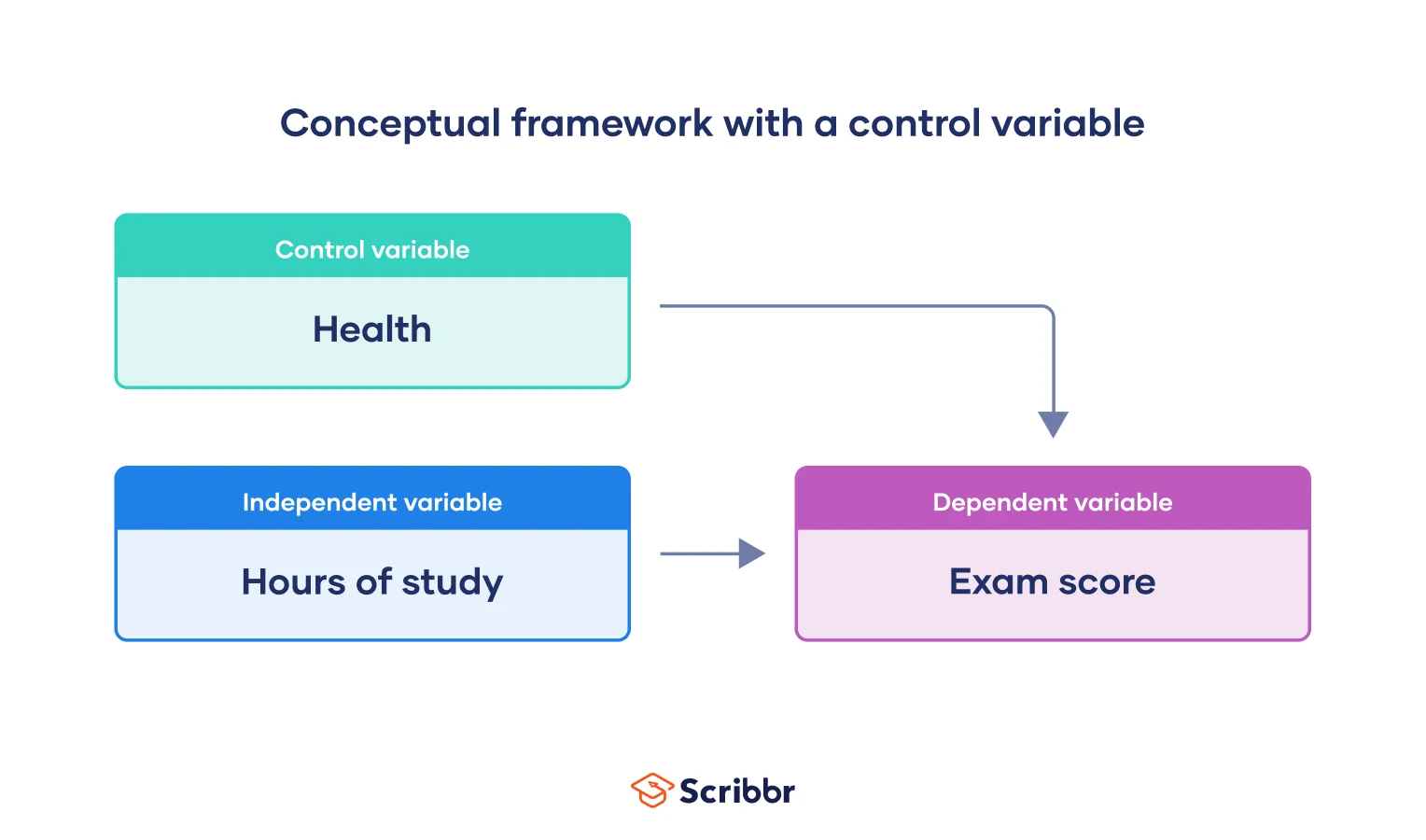

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

A confounding variable is closely related to both the independent and dependent variables in a study. An independent variable represents the supposed cause , while the dependent variable is the supposed effect . A confounding variable is a third variable that influences both the independent and dependent variables.

Failing to account for confounding variables can cause you to wrongly estimate the relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/conceptual-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Independent vs. dependent variables | definition & examples, mediator vs. moderator variables | differences & examples, control variables | what are they & why do they matter, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Inspiration

Three things to look forward to at Insight Out

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

What is a good example of a conceptual framework?

Last updated

18 April 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

A well-designed study doesn’t just happen. Researchers work hard to ensure the studies they conduct will be scientifically valid and will advance understanding in their field.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- The importance of a conceptual framework

The main purpose of a conceptual framework is to improve the quality of a research study. A conceptual framework achieves this by identifying important information about the topic and providing a clear roadmap for researchers to study it.

Through the process of developing this information, researchers will be able to improve the quality of their studies in a few key ways.

Clarify research goals and objectives

A conceptual framework helps researchers create a clear research goal. Research projects often become vague and lose their focus, which makes them less useful. However, a well-designed conceptual framework helps researchers maintain focus. It reinforces the project’s scope, ensuring it stays on track and produces meaningful results.

Provide a theoretical basis for the study

Forming a hypothesis requires knowledge of the key variables and their relationship to each other. Researchers need to identify these variables early on to create a conceptual framework. This ensures researchers have developed a strong understanding of the topic before finalizing the study design. It also helps them select the most appropriate research and analysis methods.

Guide the research design

As they develop their conceptual framework, researchers often uncover information that can help them further refine their work.

Here are some examples:

Confounding variables they hadn’t previously considered

Sources of bias they will have to take into account when designing the project

Whether or not the information they were going to study has already been covered—this allows them to pivot to a more meaningful goal that brings new and relevant information to their field

- Steps to develop a conceptual framework

There are four major steps researchers will follow to develop a conceptual framework. Each step will be described in detail in the sections that follow. You’ll also find examples of how each might be applied in a range of fields.

Step 1: Choose the research question

The first step in creating a conceptual framework is choosing a research question . The goal of this step is to create a question that’s specific and focused.

By developing a clear question, researchers can more easily identify the variables they will need to account for and keep their research focused. Without it, the next steps will be more difficult and less effective.

Here are some examples of good research questions in a few common fields:

Natural sciences: How does exposure to ultraviolet radiation affect the growth rate of a particular type of algae?

Health sciences: What is the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating depression in adolescents?

Business: What factors contribute to the success of small businesses in a particular industry?

Education: How does implementing technology in the classroom impact student learning outcomes?

Step 2: Select the independent and dependent variables

Once the research question has been chosen, it’s time to identify the dependent and independent variables .

The independent variable is the variable researchers think will affect the dependent variable . Without this information, researchers cannot develop a meaningful hypothesis or design a way to test it.

The dependent and independent variables for our example questions above are:

Natural sciences

Independent variable: exposure to ultraviolet radiation

Dependent variable: the growth rate of a particular type of algae

Health sciences

Independent variable: cognitive-behavioral therapy

Dependent variable: depression in adolescents

Independent variables: factors contributing to the business’s success

Dependent variable: sales, return on investment (ROI), or another concrete metric

Independent variable: implementation of technology in the classroom

Dependent variable: student learning outcomes, such as test scores, GPAs, or exam results

Step 3: Visualize the cause-and-effect relationship

This step is where researchers actually develop their hypothesis. They will predict how the independent variable will impact the dependent variable based on their knowledge of the field and their intuition.

With a hypothesis formed, researchers can more accurately determine what data to collect and how to analyze it. They will then visualize their hypothesis by creating a diagram. This visualization will serve as a framework to help guide their research.

The diagrams for our examples might be used as follows:

Natural sciences : how exposure to radiation affects the biological processes in the algae that contribute to its growth rate

Health sciences : how different aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy can affect how patients experience symptoms of depression

Business : how factors such as market demand, managerial expertise, and financial resources influence a business’s success

Education : how different types of technology interact with different aspects of the learning process and alter student learning outcomes

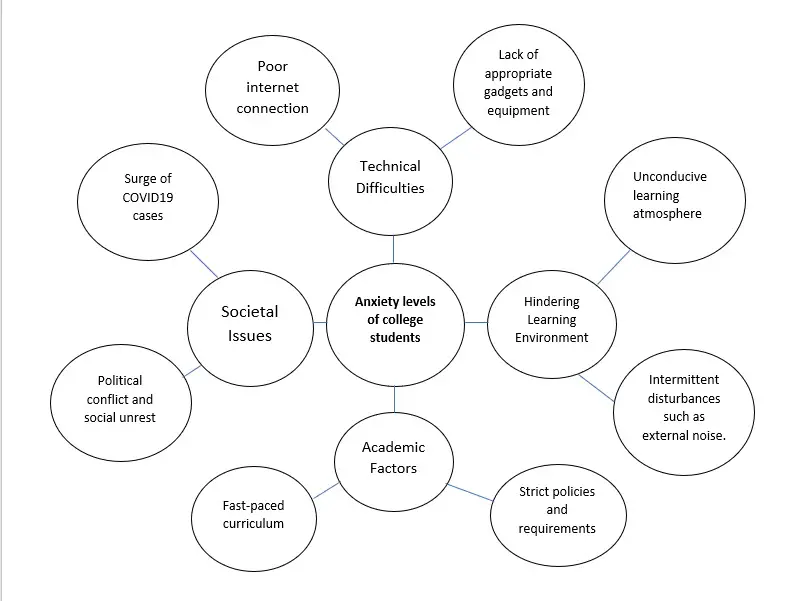

Step 4: Identify other influencing variables

The independent and dependent variables are only part of the equation. Moderating, mediating, and control variables are also important parts of a well-designed study. These variables can impact the relationship between the two main variables and must be accounted for.

A moderating variable is one that can change how the independent variable affects the dependent variable. A mediating variable explains the relationship between the two. Control variables are kept the same to eliminate their impact on the results. Examples of each are given below:

Moderating variable: water temperature (might impact how algae respond to radiation exposure)

Mediating variable: chlorophyll production (might explain how radiation exposure affects algae growth rate)

Control variable: nutrient levels in the water

Moderating variable: the severity of depression symptoms at baseline might impact how effective the therapy is for different adolescents

Mediating variable: social support might explain how cognitive-behavioral therapy leads to improvements in depression

Control variable: other forms of treatment received before or during the study

Moderating variable: the size of the business (might impact how different factors contribute to market share, sales, ROI, and other key success metrics)

Mediating variable: customer satisfaction (might explain how different factors impact business success)

Control variable: industry competition

Moderating variable: student age (might impact how effective technology is for different students)

Mediating variable: teacher training (might explain how technology leads to improvements in learning outcomes)

Control variable: student learning style

- Conceptual versus theoretical frameworks

Although they sound similar, conceptual and theoretical frameworks have different goals and are used in different contexts. Understanding which to use will help researchers craft better studies.

Conceptual frameworks describe a broad overview of the subject and outline key concepts, variables, and the relationships between them. They provide structure to studies that are more exploratory in nature, where the relationships between the variables are still being established. They are particularly helpful in studies that are complex or interdisciplinary because they help researchers better organize the factors involved in the study.

Theoretical frameworks, on the other hand, are used when the research question is more clearly defined and there’s an existing body of work to draw upon. They define the relationships between the variables and help researchers predict outcomes. They are particularly helpful when researchers want to refine the existing body of knowledge rather than establish it.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Conceptual Framework – How to Develop it for Research

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

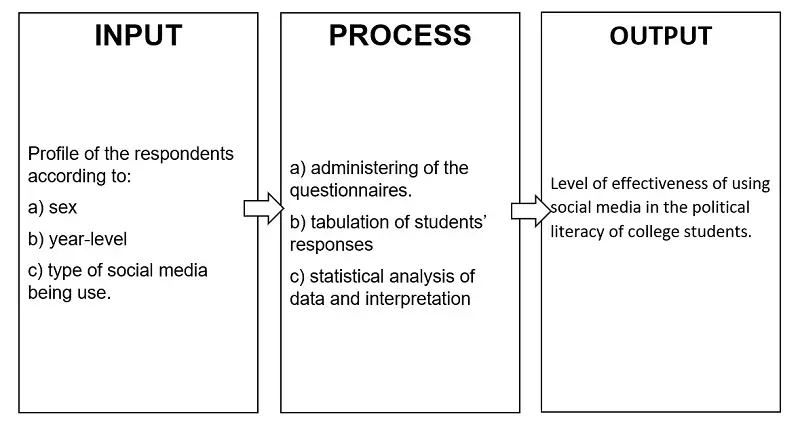

In academic writing, a conceptual framework serves as a key component of the research methodology , providing a schematic representation of the concepts and their proposed relationships. This tool not only guides data collection and interpretation but also clarifies the research question and hypothesis. The conceptual framework aims to make research conclusions more meaningful and generalizable. It outlines the purpose and the importance of the research topic .

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Conceptual Framework – In a Nutshell

- 2 Definition: Conceptual framework

- 3 Conceptual framework: Independent vs. Dependent variables

- 4 Conceptual framework: Moderating variables

- 5 Conceptual framework: Mediating variables

- 6 Conceptual framework: Control variables

Conceptual Framework – In a Nutshell

- The conceptual framework is a model used to show the relationship between the independent vs. dependent variables in a research problem .

- Researchers consider several variables in a conceptual framework, including control variables, mediating variables, and monitoring variables.

- It is important to identify control variables in a conceptual framework to minimize their effect on the findings of a study.

Definition: Conceptual framework

A conceptual framework is a visual model that illustrates the anticipated relationship between the cause and effect variables. It highlights the research goals and creates a layout of their relationship to form meaningful conclusions. The conceptual framework is usually drawn from the literature review during the early stages of research to form appropriate research questions .

Conceptual framework: Independent vs. Dependent variables

Researchers define independent vs. dependent variables to test for cause and effect when developing a conceptual framework.

Example of dependent vs. independent variables

You want to investigate whether drivers with more experience are involved in fewer accidents.

- Hypothesis: The more experience a driver has, the fewer accidents they are likely to be involved in .

- Independent variable: The years of experience

- Dependent variable: The expected cause and the number of accidents

Unlike above, causal relationships in a conceptual framework usually have more than one independent variable .

Conceptual framework: Moderating variables

Moderating variables influence the strength of the relationship between two variables in a conceptual framework. They are used to determine the external validity of the research conclusions based on their ability to strengthen, negate or otherwise affect the association between the independent vs. dependent variables.

Moderating variables are helpful in a conceptual framework because they illustrate the relationship between different variables in a research topic .

Income levels can predict general happiness, although the relationship may be stronger for younger people than for older workers. Age is the moderating variable in this conceptual framework.

Moderators can be divided into categorical variables such as religion, blood group, or race and quantitative variables like height, age, and income.

In our study of drivers’ experience and accidents, we can introduce age as the moderating variable. In this case, a driver’s age can influence the effect of years of experience on the number of accidents. The researcher expects that ‘age’ moderates the effect of experience on road safety.

Conceptual framework: Mediating variables

A conceptual framework also takes mediating variables into account. They illustrate the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable by showing how and why the effect occurs. A variable is considered a mediator if:

- It is caused by an independent variable.

- It affects the dependent variable.

- The statistical correlation between the dependent and the independent variable is more significant when it is considered than when it’s not.

Researchers use mediation analysis to test if a variable is a mediator using ANOVA and linear regression analysis. ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) tests the presence and strength of the statistical differences between the means calculated from several independent samples.

ANOVA: Determines the effects of age, gender, and disposable income on average consumer spending per month.

Linear regression: Predicts the value of a dependent variable based on the value of the independent variable.

The main aims of linear regression in a conceptual framework are to test the effectiveness of a group of predictor values in predicting a result and identifying the significant predictors of the outcome.

An individual’s body weight has a linear relationship with their weight. The researcher expects that as the height of the person increases, their weight increases. A set of observations can be plotted on a scatter plot to illustrate the strength of the correlation between the variables.

Conceptual framework: Control variables

Control variables are also considered in the conceptual framework. They define factors controlled by the researcher as it may affect the findings of a study even though it is of no interest to the researcher when designing a conceptual framework.

Control variables are used to improve the validity of a research study by reducing the effect of other variables outside the scope of the study. They help researchers to determine the relationship between the key variables under observation.

Control variables can be managed directly by keeping them constant, for instance choosing participants within the same age group. They can also be managed indirectly by using random samples to reduce their effect.

Example of control variables in the conceptual framework

In our study of driver’s experience and accident rates, the weather may affect the rate of accidents. However, our primary focus is not on the relationship between the weather and accident rates, although it may affect the findings of our study. Therefore, The ‘weather’ is added as a control variable in our conceptual framework.

If a researcher fails to control some variables, it may be difficult to prove that they did not affect the research outcome. Control variables are used in experimental research to guarantee that the observable results are exclusively caused by the experimental design.

Variables in a conceptual framework can be controlled by:

- Random assignment – Selecting random groups ensures there are no identifiable differences, which may skew your conclusions.

- Statistical controls – You can isolate the effects of the control variable by measuring and controlling it.

- Standardized procedures – Researchers should ensure the same methods are applied in all the groups in a study. Only the independent variables should be altered across groups to observe how they affect the dependent variable.

What is the conceptual framework in research?

It is an illustration of the relationship between variables in a study. It is used to form the hypothesis that guides the methods of research.

What are control variables?

Control variables are factors that are directly or indirectly controlled by the researchers. They are extraneous variables that may affect the observations in a study.

Where are conceptual frameworks used?

Conceptual frameworks are used in multiple social sciences and humanities. They help in formulating and investigating the research problem.

What is a moderating variable in a conceptual framework?

A moderating variable influences the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable. It is used to measure the impact of an additional variable on the dependent-independent variable relationship.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format.

Updated on August 28, 2023

What are frameworks in research?

Both theoretical and conceptual frameworks have a significant role in research. Frameworks are essential to bridge the gaps in research. They aid in clearly setting the goals, priorities, relationship between variables. Frameworks in research particularly help in chalking clear process details.

Theoretical frameworks largely work at the time when a theoretical roadmap has been laid about a certain topic and the research being undertaken by the researcher, carefully analyzes it, and works on similar lines to attain successful results.

It varies from a conceptual framework in terms of the preliminary work required to construct it. Though a conceptual framework is part of the theoretical framework in a larger sense, yet there are variations between them.

The following sections delve deeper into the characteristics of conceptual frameworks. This article will provide insight into constructing a concise, complete, and research-friendly conceptual framework for your project.

Definition of a conceptual framework

True research begins with setting empirical goals. Goals aid in presenting successful answers to the research questions at hand. It delineates a process wherein different aspects of the research are reflected upon, and coherence is established among them.

A conceptual framework is an underrated methodological approach that should be paid attention to before embarking on a research journey in any field, be it science, finance, history, psychology, etc.

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format. Your conceptual framework establishes a link between the dependent and independent variables, factors, and other ideologies affecting the structure of your research.

A critical facet a conceptual framework unveils is the relationship the researchers have with their research. It closely highlights the factors that play an instrumental role in decision-making, variable selection, data collection, assessment of results, and formulation of new theories.

Consequently, if you, the researcher, are at the forefront of your research battlefield, your conceptual framework is the most powerful arsenal in your pocket.

What should be included in a conceptual framework?

A conceptual framework includes the key process parameters, defining variables, and cause-and-effect relationships. To add to this, the primary focus while developing a conceptual framework should remain on the quality of questions being raised and addressed through the framework. This will not only ease the process of initiation, but also enable you to draw meaningful conclusions from the same.

A practical and advantageous approach involves selecting models and analyzing literature that is unconventional and not directly related to the topic. This helps the researcher design an illustrative framework that is multidisciplinary and simultaneously looks at a diverse range of phenomena. It also emboldens the roots of exploratory research.

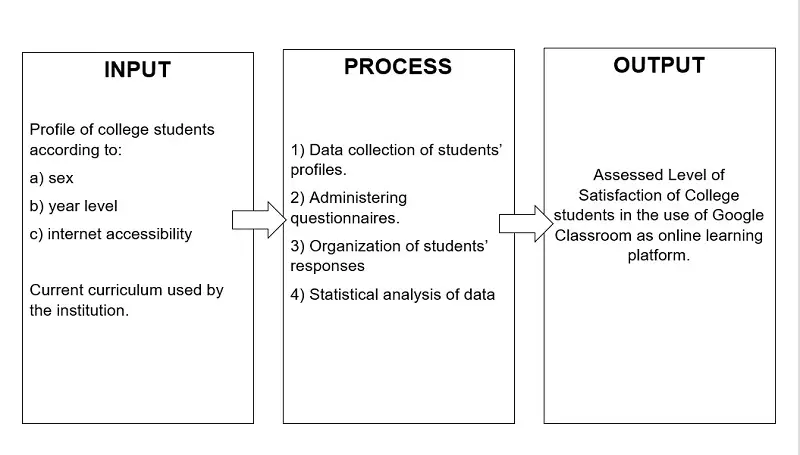

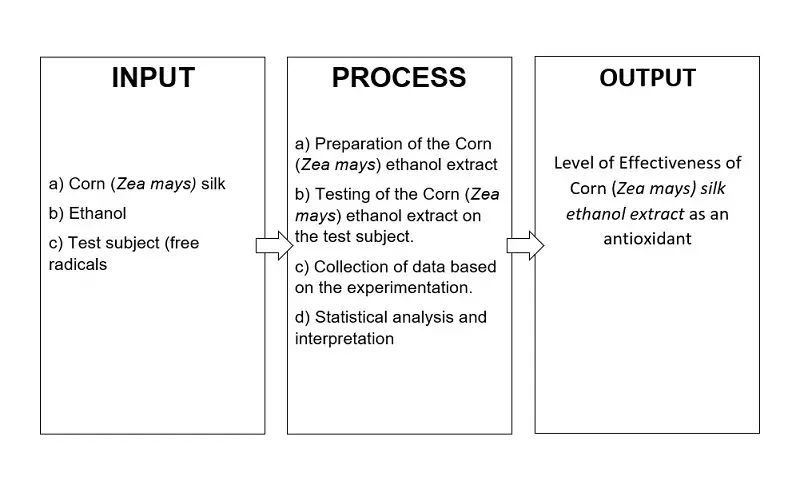

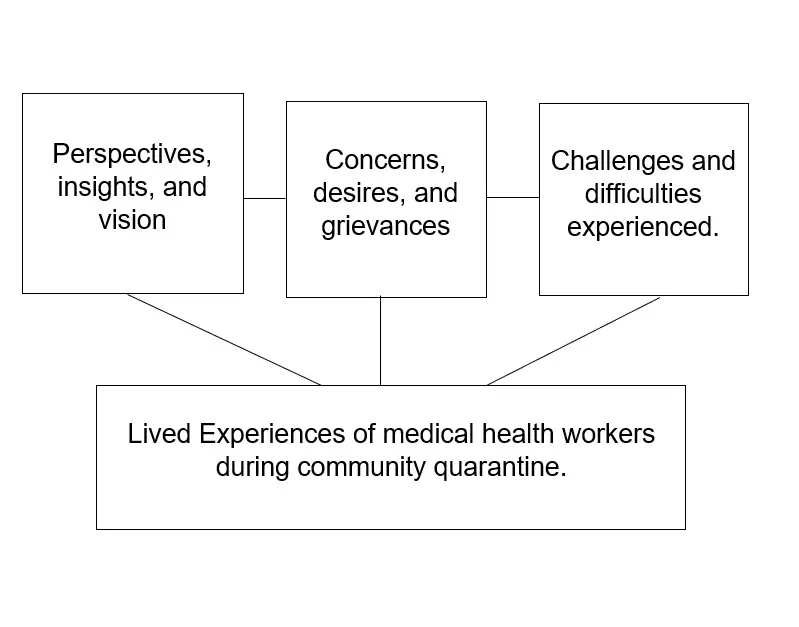

Fig. 1: Components of a conceptual framework

How to make a conceptual framework

The successful design of a conceptual framework includes:

- Selecting the appropriate research questions

- Defining the process variables (dependent, independent, and others)

- Determining the cause-and-effect relationships

This analytical tool begins with defining the most suitable set of questions that the research wishes to answer upon its conclusion. Following this, the different variety of variables is categorized. Lastly, the collected data is subjected to rigorous data analysis. Final results are compiled to establish links between the variables.

The variables drawn inside frames impact the overall quality of the research. If the framework involves arrows, it suggests correlational linkages among the variables. Lines, on the other hand, suggest that no significant correlation exists among them. Henceforth, the utilization of lines and arrows should be done taking into cognizance the meaning they both imply.

Example of a conceptual framework

To provide an idea about a conceptual framework, let’s examine the example of drug development research.

Say a new drug moiety A has to be launched in the market. For that, the baseline research begins with selecting the appropriate drug molecule. This is important because it:

- Provides the data for molecular docking studies to identify suitable target proteins

- Performs in vitro (a process taking place outside a living organism) and in vivo (a process taking place inside a living organism) analyzes

This assists in the screening of the molecules and a final selection leading to the most suitable target molecule. In this case, the choice of the drug molecule is an independent variable whereas, all the others, targets from molecular docking studies, and results from in vitro and in vivo analyses are dependent variables.

The outcomes revealed by the studies might be coherent or incoherent with the literature. In any case, an accurately designed conceptual framework will efficiently establish the cause-and-effect relationship and explain both perspectives satisfactorily.

If A has been chosen to be launched in the market, the conceptual framework will point towards the factors that have led to its selection. If A does not make it to the market, the key elements which did not work in its favor can be pinpointed by an accurate analysis of the conceptual framework.

Fig. 2: Concise example of a conceptual framework

Important takeaways

While conceptual frameworks are a great way of designing the research protocol, they might consist of some unforeseen loopholes. A review of the literature can sometimes provide a false impression of the collection of work done worldwide while in actuality, there might be research that is being undertaken on the same topic but is still under publication or review. Strong conceptual frameworks, therefore, are designed when all these aspects are taken into consideration and the researchers indulge in discussions with others working on similar grounds of research.

Conceptual frameworks may also sometimes lead to collecting and reviewing data that is not so relevant to the current research topic. The researchers must always be on the lookout for studies that are highly relevant to their topic of work and will be of impact if taken into consideration.

Another common practice associated with conceptual frameworks is their classification as merely descriptive qualitative tools and not actually a concrete build-up of ideas and critically analyzed literature and data which it is, in reality. Ideal conceptual frameworks always bring out their own set of new ideas after analysis of literature rather than simply depending on facts being already reported by other research groups.

So, the next time you set out to construct your conceptual framework or improvise on your previous one, be wary that concepts for your research are ideas that need to be worked upon. They are not simply a collection of literature from the previous research.

Final thoughts

Research is witnessing a boom in the methodical approaches being applied to it nowadays. In contrast to conventional research, researchers today are always looking for better techniques and methods to improve the quality of their research.

We strongly believe in the ideals of research that are not merely academic, but all-inclusive. We strongly encourage all our readers and researchers to do work that impacts society. Designing strong conceptual frameworks is an integral part of the process. It gives headway for systematic, empirical, and fruitful research.

Vridhi Sachdeva, MPharm

See our "Privacy Policy"

Get an overall assessment of the main focus of your study from AJE

Our Presubmission Review service will provide recommendations on the structure, organization, and the overall presentation of your research manuscript.

- Section 1: Home

- Narrowing Your Topic

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

Defining The Conceptual Framework

Making a conceptual framework, conceptual framework for dmft students, conceptual framework guide, example frameworks, additional framework resources.

- Student Experience Feedback Buttons

- Avoiding Common Mistakes

- Synthesis and Analysis in Writing Support This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative Research Questions This link opens in a new window

- Quantitative Research Questions This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative & Quantitative Research Support with the ASC This link opens in a new window

- Library Research Consultations This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: Research Process This link opens in a new window

- ASC Guide: Outlining and Annotating This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: RefWorks This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: Copyright Information This link opens in a new window

What is it?

- The researcher’s understanding/hypothesis/exploration of either an existing framework/model or how existing concepts come together to inform a particular problem. Shows the reader how different elements come together to facilitate research and a clear understanding of results.

- Informs the research questions/methodology (problem statement drives framework drives RQs drives methodology)

- A tool (linked concepts) to help facilitate the understanding of the relationship among concepts or variables in relation to the real-world. Each concept is linked to frame the project in question.

- Falls inside of a larger theoretical framework (theoretical framework = explains the why and how of a particular phenomenon within a particular body of literature).

- Can be a graphic or a narrative – but should always be explained and cited

- Can be made up of theories and concepts

What does it do?

- Explains or predicts the way key concepts/variables will come together to inform the problem/phenomenon

- Gives the study direction/parameters

- Helps the researcher organize ideas and clarify concepts

- Introduces your research and how it will advance your field of practice. A conceptual framework should include concepts applicable to the field of study. These can be in the field or neighboring fields – as long as important details are captured and the framework is relevant to the problem. (alignment)

What should be in it?

- Variables, concepts, theories, and/or parts of other existing frameworks

How to make a conceptual framework

- With a topic in mind, go to the body of literature and start identifying the key concepts used by other studies. Figure out what’s been done by other researchers, and what needs to be done (either find a specific call to action outlined in the literature or make sure your proposed problem has yet to be studied in your specific setting). Use what you find needs to be done to either support a pre-identified problem or craft a general problem for study. Only rely on scholarly sources for this part of your research.

- Begin to pull out variables, concepts, theories, and existing frameworks explained in the relevant literature.

- If you’re building a framework, start thinking about how some of those variables, concepts, theories, and facets of existing frameworks come together to shape your problem. The problem could be a situational condition that requires a scholar-practitioner approach, the result of a practical need, or an opportunity to further an applicational study, project, or research. Remember, if the answer to your specific problem exists, you don’t need to conduct the study.

- The actionable research you’d like to conduct will help shape what you include in your framework. Sketch the flow of your Applied Doctoral Project from start to finish and decide which variables are truly the best fit for your research.

- Create a graphic representation of your framework (this part is optional, but often helps readers understand the flow of your research) Even if you do a graphic, first write out how the variables could influence your Applied Doctoral Project and introduce your methodology. Remember to use APA formatting in separating the sections of your framework to create a clear understanding of the framework for your reader.

- As you move through your study, you may need to revise your framework.

- Note for qualitative/quantitative research: If doing qualitative, make sure your framework doesn’t include arrow lines, which could imply causal or correlational linkages.

- Conceptural and Theoretical Framework for DMFT Students This document is specific to DMFT students working on a conceptual or theoretical framework for their applied project.

- Conceptual Framework Guide Use this guide to determine the guiding framework for your applied dissertation research.

Let’s say I’ve just taken a job as manager of a failing restaurant. Throughout first week, I notice the few customers they have are leaving unsatisfied. I need to figure out why and turn the establishment into a thriving restaurant. I get permission from the owner to do a study to figure out exactly what we need to do to raise levels of customer satisfaction. Since I have a specific problem and want to make sure my research produces valid results, I go to the literature to find out what others are finding about customer satisfaction in the food service industry. This particular restaurant is vegan focused – and my search of the literature doesn’t say anything specific about how to increase customer service in a vegan atmosphere, so I know this research needs to be done.

I find out there are different types of satisfaction across other genres of the food service industry, and the one I’m interested in is cumulative customer satisfaction. I then decide based on what I’m seeing in the literature that my definition of customer satisfaction is the way perception, evaluation, and psychological reaction to perception and evaluation of both tangible and intangible elements of the dining experience come together to inform customer expectations. Essentially, customer expectations inform customer satisfaction.

I then find across the literature many variables could be significant in determining customer satisfaction. Because the following keep appearing, they are the ones I choose to include in my framework: price, service, branding (branched out to include physical environment and promotion), and taste. I also learn by reading the literature, satisfaction can vary between genders – so I want to make sure to also collect demographic information in my survey. Gender, age, profession, and number of children are a few demographic variables I understand would be helpful to include based on my extensive literature review.

Note: this is a quantitative study. I’m including all variables in this study, and the variables I am testing are my independent variables. Here I’m working to see how each of the independent variables influences (or not) my dependent variable, customer satisfaction. If you are interested in qualitative study, read on for an example of how to make the same framework qualitative in nature.

Also note: when you create your framework, you’ll need to cite each facet of your framework. Tell the reader where you got everything you’re including. Not only is it in compliance with APA formatting, but also it raises your credibility as a researcher. Once you’ve built the narrative around your framework, you may also want to create a visual for your reader.

See below for one example of how to illustrate your framework:

If you’re interested in a qualitative study, be sure to omit arrows and other notations inferring statistical analysis. The only time it would be inappropriate to include a framework in qualitative study is in a grounded theory study, which is not something you’ll do in an applied doctoral study.

A visual example of a qualitative framework is below:

Some additional helpful resources in constructing a conceptual framework for study:

- Problem Statement, Conceptual Framework, and Research Question. McGaghie, W. C.; Bordage, G.; and J. A. Shea (2001). Problem Statement, Conceptual Framework, and Research Question. Retrieved on January 5, 2015 from http://goo.gl/qLIUFg

- Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definitions, and Procedure

- https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/conceptual-framework/

- https://www.projectguru.in/developing-conceptual-framework-in-a-research-paper/

Conceptual Framework Research

A conceptual framework is a synthetization of interrelated components and variables which help in solving a real-world problem. It is the final lens used for viewing the deductive resolution of an identified issue (Imenda, 2014). The development of a conceptual framework begins with a deductive assumption that a problem exists, and the application of processes, procedures, functional approach, models, or theory may be used for problem resolution (Zackoff et al., 2019). The application of theory in traditional theoretical research is to understand, explain, and predict phenomena (Swanson, 2013). In applied research the application of theory in problem solving focuses on how theory in conjunction with practice (applied action) and procedures (functional approach) frames vision, thinking, and action towards problem resolution. The inclusion of theory in a conceptual framework is not focused on validation or devaluation of applied theories. A concise way of viewing the conceptual framework is a list of understood fact-based conditions that presents the researcher’s prescribed thinking for solving the identified problem. These conditions provide a methodological rationale of interrelated ideas and approaches for beginning, executing, and defining the outcome of problem resolution efforts (Leshem & Trafford, 2007).

The term conceptual framework and theoretical framework are often and erroneously used interchangeably (Grant & Osanloo, 2014). Just as with traditional research, a theory does not or cannot be expected to explain all phenomenal conditions, a conceptual framework is not a random identification of disparate ideas meant to incase a problem. Instead it is a means of identifying and constructing for the researcher and reader alike an epistemological mindset and a functional worldview approach to the identified problem.

Grant, C., & Osanloo, A. (2014). Understanding, Selecting, and Integrating a Theoretical Framework in Dissertation Research: Creating the Blueprint for Your “House. ” Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research, 4(2), 12–26

Imenda, S. (2014). Is There a Conceptual Difference between Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks? Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi/Journal of Social Sciences, 38(2), 185.

Leshem, S., & Trafford, V. (2007). Overlooking the conceptual framework. Innovations in Education & Teaching International, 44(1), 93–105. https://doi-org.proxy1.ncu.edu/10.1080/14703290601081407

Swanson, R. (2013). Theory building in applied disciplines . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Zackoff, M. W., Real, F. J., Klein, M. D., Abramson, E. L., Li, S.-T. T., & Gusic, M. E. (2019). Enhancing Educational Scholarship Through Conceptual Frameworks: A Challenge and Roadmap for Medical Educators . Academic Pediatrics, 19(2), 135–141. https://doi-org.proxy1.ncu.edu/10.1016/j.acap.2018.08.003

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Alignment

- Next: Avoiding Common Mistakes >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2023 12:28 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1013602

Research Process Guide

- Step 1 - Identifying and Developing a Topic

- Step 2 - Narrowing Your Topic

- Step 3 - Developing Research Questions

- Step 4 - Conducting a Literature Review

- Step 5 - Choosing a Conceptual or Theoretical Framework

- Step 6 - Determining Research Methodology

- Step 6a - Determining Research Methodology - Quantitative Research Methods

- Step 6b - Determining Research Methodology - Qualitative Design

- Step 7 - Considering Ethical Issues in Research with Human Subjects - Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Step 8 - Collecting Data

- Step 9 - Analyzing Data

- Step 10 - Interpreting Results

- Step 11 - Writing Up Results

Step 5: Choosing a Conceptual or Theoretical Framework

For all empirical research, you must choose a conceptual or theoretical framework to “frame” or “ground” your study. Theoretical and/or conceptual frameworks are often difficult to understand and challenging to choose which is the right one (s) for your research objective (Hatch, 2002). Truthfully, it is difficult to get a real understanding of what these frameworks are and how you are supposed to find what works for your study. The discussion of your framework is addressed in your Chapter 1, the introduction and then is further explored through in-depth discussion in your Chapter 2 literature review.

“Theory is supposed to help researchers of any persuasion clarify what they are up to and to help them to explain to others what they are up to” (Walcott, 1995, p. 189, as cited in Fallon, 2016). It is important to discuss in the beginning to help researchers “clarify what they are up to” and important at the writing stage to “help explain to others what they are up to” (Fallon, 2016).

What is the difference between the conceptual and the theoretical framework?

Often, the terms theoretical framework and conceptual framework are used interchangeably, which, in this author’s opinion, makes an already difficult to understand idea even more confusing. According to Imenda (2014) and Mensah et al. (2020), there is a very distinct difference between conceptual and theoretical frameworks, not only how they are defined but also, how and when they are used in empirical research.

Imenda (2014) contends that the framework “is the soul of every research project” (p.185). Essentially, it determines how the researcher formulates the research problem, goes about investigating the problem, and what meaning or significance the research lends to the data collected and analyzed investigating the problem.

Very generally, you would use a theoretical framework if you were conducting deductive research as you test a theory or theories. “A theoretical framework comprises the theories expressed by experts in the field into which you plan to research, which you draw upon to provide a theoretical coat hanger for your data analysis and interpretation of results” (Kivunja, 2018, p.45 ). Often this framework is based on established theories like, the Set Theory, evolution, the theory of matter or similar pre-existing generalizations like Newton’s law of motion (Imenda, 2014). A good theoretical framework should be linked to, and possibly emerge from your literature review.

Using a theoretical framework allows you to (Kivunja, 2018):

- Increase the credibility and validity of your research

- Interpret meaning found in data collection

- Evaluate solutions for solving your research problem

According to Mensah et al.(2020) the theoretical framework for your research is not a summary of your own thoughts about your research. Rather, it is a compilation of the thoughts of giants in your field, as they relate to your proposed research, as you understand those theories, and how you will use those theories to understand the data collected.

Additionally, Jabareen (2009) defines a conceptual framework as interlinked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon. “A conceptual framework is the total, logical orientation and associations of anything and everything that forms the underlying thinking, structures, plans and practices and implementation of your entire research project” (Kivunja, 2018, p. 45). You would largely use a conceptual framework when conducting inductive research, as it helps the researcher answer questions that are core to qualitative research, such as the nature of reality, the way things are and how things really work in a real world (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Some consideration of the following questions can help define your conceptual framework (Kinvunja, 2018):

- What do you want to do in your research? And why do you want to do it?

- How do you plan to do it?

- What meaning will you make of the data?

- Which worldview will you situate your study in? (i.e. Positivist? Interpretist? Constructivist?)

Examples of conceptual frameworks include the definitions a sociologist uses to describe a culture and the types of data an economist considers when evaluating a country’s industry. The conceptual framework consists of the ideas that are used to define research and evaluate data. Conceptual frameworks are often laid out at the beginning of a paper or an experiment description for a reader to understand the methods used (Mensah et al., 2020).

Writing it up

After choosing your framework is to articulate the theory or concept that grounds your study by defining it and demonstrating the rationale for this particular set of theories or concepts guiding your inquiry. Write up your theoretical perspective sections for your research plan following your choice of worldview/ research paradigm. For a quantitative study you are particularly interested in theory using the procedures for a causal analysis. For qualitative research, you should locate qualitative journal articles that use a priori theory (knowledge that is acquired not through experience) that is modified during the process of research (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Also, you should generate or develop a theory at the end of your study. For a mixed methods study which uses a transformative (critical theoretical lens) identify how the lens specifically shapes the research process.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2 018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

Fallon, M. (2016). Writing up quantitative research in the social and behavioral sciences. Sense. https://kean.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,url,cpid&custid=keaninf&db=nlebk&AN=1288374&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_C1

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2 (163-194), 105.

Hatch, J. A. ( 2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. SUNY Press.

Imenda, S. (2014). Is there a conceptual difference between theoretical and conceptual frameworks? Journal of Social Sciences, 38 (2), 185-195.

Jabareen, Y. (2009). Building a conceptual framework: Philosophy, definitions, and procedure. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8 (4), 49-62.

Kivunja, C. ( 2018, December 3). Distinguishing between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. The International Journal of Higher Education, 7 (6), 44-53. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1198682.pdf

Mensah, R. O., Agyemang, F., Acquah, A., Babah, P. A., & Dontoh, J. (2020). Discourses on conceptual and theoretical frameworks in research: Meaning and implications for researchers. Journal of African Interdisciplinary Studies, 4 (5), 53-64.

- Last Updated: Jun 29, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.kean.edu/ResearchProcessGuide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on 18 March 2024.

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualise your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, ‘hours of study’, is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, ‘exam score’, is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (‘hours of study’).

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualising your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

Moderating variables

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the ‘effect’ component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator ‘IQ’. Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable ‘hours of study’ has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

But the graph looks different when we add our ‘IQ’ moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

Below, the value of the ‘IQ’ moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

No. The value of a dependent variable depends on an independent variable, so a variable cannot be both independent and dependent at the same time. It must be either the cause or the effect, not both.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/conceptual-frameworks/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Mediator vs moderator variables | differences & examples, independent vs dependent variables | definition & examples, what are control variables | definition & examples.

Theoretical vs Conceptual Framework

What they are & how they’re different (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, sooner or later you’re bound to run into the terms theoretical framework and conceptual framework . These are closely related but distinctly different things (despite some people using them interchangeably) and it’s important to understand what each means. In this post, we’ll unpack both theoretical and conceptual frameworks in plain language along with practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Theoretical vs Conceptual

What is a theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, what is a conceptual framework, example of a conceptual framework.

- Theoretical vs conceptual: which one should I use?

A theoretical framework (also sometimes referred to as a foundation of theory) is essentially a set of concepts, definitions, and propositions that together form a structured, comprehensive view of a specific phenomenon.

In other words, a theoretical framework is a collection of existing theories, models and frameworks that provides a foundation of core knowledge – a “lay of the land”, so to speak, from which you can build a research study. For this reason, it’s usually presented fairly early within the literature review section of a dissertation, thesis or research paper .

Let’s look at an example to make the theoretical framework a little more tangible.

If your research aims involve understanding what factors contributed toward people trusting investment brokers, you’d need to first lay down some theory so that it’s crystal clear what exactly you mean by this. For example, you would need to define what you mean by “trust”, as there are many potential definitions of this concept. The same would be true for any other constructs or variables of interest.

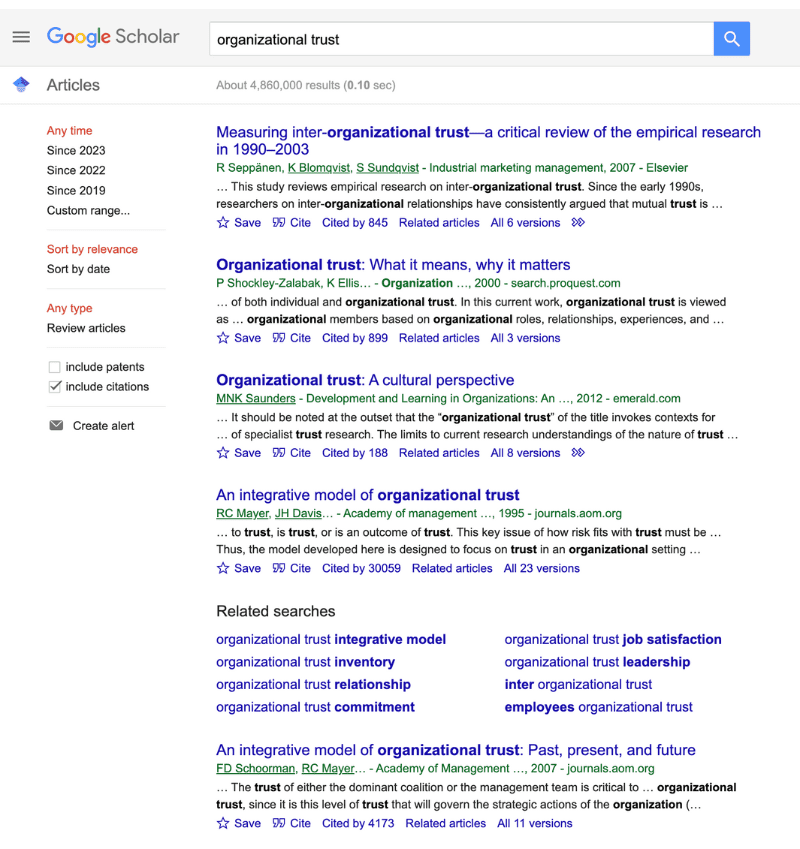

You’d also need to identify what existing theories have to say in relation to your research aim. In this case, you could discuss some of the key literature in relation to organisational trust. A quick search on Google Scholar using some well-considered keywords generally provides a good starting point.

Typically, you’ll present your theoretical framework in written form , although sometimes it will make sense to utilise some visuals to show how different theories relate to each other. Your theoretical framework may revolve around just one major theory , or it could comprise a collection of different interrelated theories and models. In some cases, there will be a lot to cover and in some cases, not. Regardless of size, the theoretical framework is a critical ingredient in any study.

Simply put, the theoretical framework is the core foundation of theory that you’ll build your research upon. As we’ve mentioned many times on the blog, good research is developed by standing on the shoulders of giants . It’s extremely unlikely that your research topic will be completely novel and that there’ll be absolutely no existing theory that relates to it. If that’s the case, the most likely explanation is that you just haven’t reviewed enough literature yet! So, make sure that you take the time to review and digest the seminal sources.

Need a helping hand?

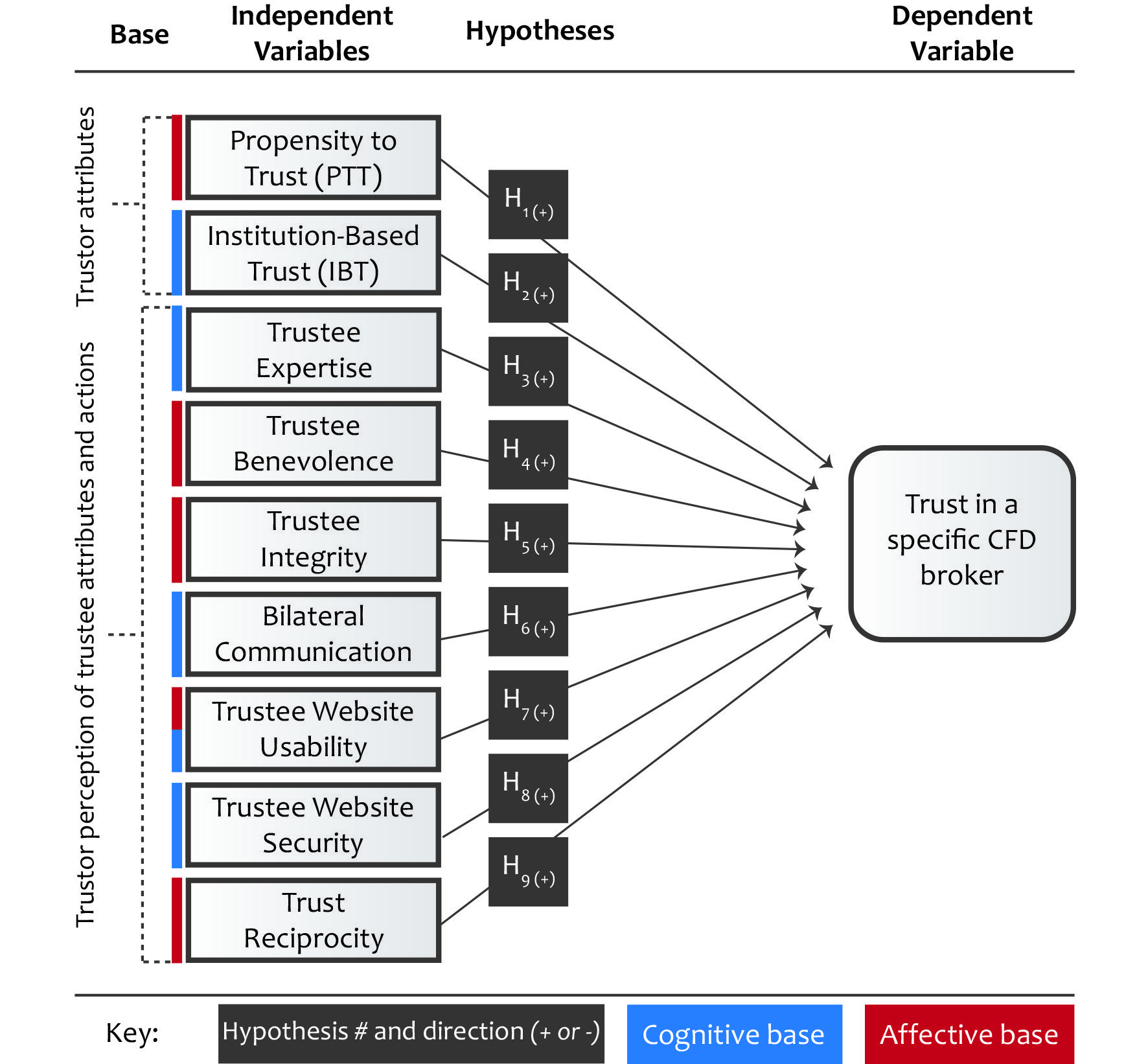

A conceptual framework is typically a visual representation (although it can also be written out) of the expected relationships and connections between various concepts, constructs or variables. In other words, a conceptual framework visualises how the researcher views and organises the various concepts and variables within their study. This is typically based on aspects drawn from the theoretical framework, so there is a relationship between the two.

Quite commonly, conceptual frameworks are used to visualise the potential causal relationships and pathways that the researcher expects to find, based on their understanding of both the theoretical literature and the existing empirical research . Therefore, the conceptual framework is often used to develop research questions and hypotheses .

Let’s look at an example of a conceptual framework to make it a little more tangible. You’ll notice that in this specific conceptual framework, the hypotheses are integrated into the visual, helping to connect the rest of the document to the framework.

As you can see, conceptual frameworks often make use of different shapes , lines and arrows to visualise the connections and relationships between different components and/or variables. Ultimately, the conceptual framework provides an opportunity for you to make explicit your understanding of how everything is connected . So, be sure to make use of all the visual aids you can – clean design, well-considered colours and concise text are your friends.

Theoretical framework vs conceptual framework

As you can see, the theoretical framework and the conceptual framework are closely related concepts, but they differ in terms of focus and purpose. The theoretical framework is used to lay down a foundation of theory on which your study will be built, whereas the conceptual framework visualises what you anticipate the relationships between concepts, constructs and variables may be, based on your understanding of the existing literature and the specific context and focus of your research. In other words, they’re different tools for different jobs , but they’re neighbours in the toolbox.

Naturally, the theoretical framework and the conceptual framework are not mutually exclusive . In fact, it’s quite likely that you’ll include both in your dissertation or thesis, especially if your research aims involve investigating relationships between variables. Of course, every research project is different and universities differ in terms of their expectations for dissertations and theses, so it’s always a good idea to have a look at past projects to get a feel for what the norms and expectations are at your specific institution.

Want to learn more about research terminology, methods and techniques? Be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog . Alternatively, if you’re looking for hands-on help, have a look at our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research process, step by step.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

17 Comments

Thank you for giving a valuable lesson

good thanks!

VERY INSIGHTFUL

thanks for given very interested understand about both theoritical and conceptual framework

I am researching teacher beliefs about inclusive education but not using a theoretical framework just conceptual frame using teacher beliefs, inclusive education and inclusive practices as my concepts

good, fantastic

great! thanks for the clarification. I am planning to use both for my implementation evaluation of EmONC service at primary health care facility level. its theoretical foundation rooted from the principles of implementation science.

This is a good one…now have a better understanding of Theoretical and Conceptual frameworks. Highly grateful

Very educating and fantastic,good to be part of you guys,I appreciate your enlightened concern.

Thanks for shedding light on these two t opics. Much clearer in my head now.

Simple and clear!

The differences between the two topics was well explained, thank you very much!

Thank you great insight

Superb. Thank you so much.

Hello Gradcoach! I’m excited with your fantastic educational videos which mainly focused on all over research process. I’m a student, I kindly ask and need your support. So, if it’s possible please send me the PDF format of all topic provided here, I put my email below, thank you!

I am really grateful I found this website. This is very helpful for an MPA student like myself.

I’m clear with these two terminologies now. Useful information. I appreciate it. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- MedEdPORTAL

Applying Conceptual and Theoretical Frameworks to Health Professions Education Research: An Introductory Workshop

Steven rougas.

1 Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and Medical Science and Director, Doctoring Program, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Andrea Berry

2 Executive Director of Faculty Life, University of Central Florida College of Medicine

S. Beth Bierer

3 Director of Assessment and Evaluation and Professor of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University

Rebecca D. Blanchard

4 Director of Faculty Development, OnlineMedEd, and Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School-Baystate

Anna T. Cianciolo

5 Associate Professor, Department of Medical Education, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

Jorie M. Colbert-Getz

6 Assistant Dean of Education Quality Improvement and Associate Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine

Heeyoung Han

7 Associate Professor and Director of Postdoctoral Program, Department of Medical Education, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

Kaitlin Lipner

8 Second-Year Resident, Department of Emergency Medicine, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Cayla R. Teal

9 Associate Dean for Assessment and Evaluation and Education Associate Professor of Population Health, University of Kansas School of Medicine

Associated Data

- Workshop Slides.pptx

- Facilitators’ Guide.docx

- Participant Worksheet.docx

- Workshop Evaluation.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Introduction

Literature suggests that the quality and rigor of health professions education (HPE) research can be elevated if the research is anchored in existing theories and frameworks. This critical skill is difficult for novice researchers to master. We created a workshop to introduce the practical application of theories and frameworks to HPE research.

We conducted two 60- to 75-minute workshops, one in 2019 at an in-person national conference and another in 2021 during an online national education conference. After a brief role-play introduction, participants applied a relevant theory to a case scenario in small groups, led by facilitators with expertise in HPE research. The workshop concluded with a presentation on applying the lessons learned when preparing a scholarly manuscript. We conducted a postworkshop survey to measure self-reported achievement of objectives.

Fifty-five individuals participated in the in-person workshop, and approximately 150 people completed the online workshop. Sixty participants (30%) completed the postworkshop survey across both workshops. As a result of participating in the workshop, 80% of participants (32) indicated they could distinguish between frameworks and theories, and 86% (32) could apply a conceptual or theoretical framework to a research question. Strengths of the workshop included the small-group activity, access to expert facilitators, and the materials provided.

The workshop has been well received by participants and fills a gap in the existing resources available to HPE researchers and mentors. It can be replicated in multiple settings to model the application of conceptual and theoretical frameworks to HPE research.

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, learners will be able to:

- 1. Describe conceptual and theoretical frameworks commonly used in health professions education research.

- 2. Examine how the selection of a framework affects research design.