The What: Defining a research project

During Academic Writing Month 2018, TAA hosted a series of #AcWriChat TweetChat events focused on the five W’s of academic writing. Throughout the series we explored The What: Defining a research project ; The Where: Constructing an effective writing environment ; The When: Setting realistic timeframes for your research ; The Who: Finding key sources in the existing literature ; and The Why: Explaining the significance of your research . This series of posts brings together the discussions and resources from those events. Let’s start with The What: Defining a research project .

Before moving forward on any academic writing effort, it is important to understand what the research project is intended to understand and document. In order to accomplish this, it’s also important to understand what a research project is. This is where we began our discussion of the five W’s of academic writing.

Q1: What constitutes a research project?

According to a Rutgers University resource titled, Definition of a research project and specifications for fulfilling the requirement , “A research project is a scientific endeavor to answer a research question.” Specifically, projects may take the form of “case series, case control study, cohort study, randomized, controlled trial, survey, or secondary data analysis such as decision analysis, cost effectiveness analysis or meta-analysis”.

Hampshire College offers that “Research is a process of systematic inquiry that entails collection of data; documentation of critical information; and analysis and interpretation of that data/information, in accordance with suitable methodologies set by specific professional fields and academic disciplines.” in their online resource titled, What is research? The resource also states that “Research is conducted to evaluate the validity of a hypothesis or an interpretive framework; to assemble a body of substantive knowledge and findings for sharing them in appropriate manners; and to generate questions for further inquiries.”

TweetChat participant @TheInfoSherpa , who is currently “investigating whether publishing in a predatory journal constitutes blatant research misconduct, inappropriate conduct, or questionable conduct,” summarized these ideas stating, “At its simplest, a research project is a project which seeks to answer a well-defined question or set of related questions about a specific topic.” TAA staff member, Eric Schmieder, added to the discussion that“a research project is a process by which answers to a significant question are attempted to be answered through exploration or experimentation.”

In a learning module focused on research and the application of the Scientific Method, the Office of Research Integrity within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services states that “Research is a process to discover new knowledge…. No matter what topic is being studied, the value of the research depends on how well it is designed and done.”

Wenyi Ho of Penn State University states that “Research is a systematic inquiry to describe, explain, predict and control the observed phenomenon.” in an online resource which further shares four types of knowledge that research contributes to education, four types of research based on different purposes, and five stages of conducting a research study. Further understanding of research in definition, purpose, and typical research practices can be found in this Study.com video resource .

Now that we have a foundational understanding of what constitutes a research project, we shift the discussion to several questions about defining specific research topics.

Q2: When considering topics for a new research project, where do you start?

A guide from the University of Michigan-Flint on selecting a topic states, “Be aware that selecting a good topic may not be easy. It must be narrow and focused enough to be interesting, yet broad enough to find adequate information.”

Schmieder responded to the chat question with his approach.“I often start with an idea or question of interest to me and then begin searching for existing research on the topic to determine what has been done already.”

@TheInfoSherpa added, “Start with the research. Ask a librarian for help. The last thing you want to do is design a study thst someone’s already done.”

The Utah State University Libraries shared a video that “helps you find a research topic that is relevant and interesting to you!”

Q2a: What strategies do you use to stay current on research in your discipline?

The California State University Chancellor’s Doctoral Incentive Program Community Commons resource offers four suggestions for staying current in your field:

- Become an effective consumer of research

- Read key publications

- Attend key gatherings

- Develop a network of colleagues

Schmieder and @TheInfoSherpa discussed ways to use databases for this purpose. Schmieder identified using “journal database searches for publications in the past few months on topics of interest” as a way to stay current as a consumer of research.

@TheInfoSherpa added, “It’s so easy to set up an alert in your favorite database. I do this for specific topics, and all the latest research gets delivered right to my inbox. Again, your academic or public #librarian can help you with this.” To which Schmieder replied, “Alerts are such useful advancements in technology for sorting through the myriad of material available online. Great advice!”

In an open access article, Keeping Up to Date: An Academic Researcher’s Information Journey , researchers Pontis, et. al. “examined how researchers stay up to date, using the information journey model as a framework for analysis and investigating which dimensions influence information behaviors.” As a result of their study, “Five key dimensions that influence information behaviors were identified: level of seniority, information sources, state of the project, level of familiarity, and how well defined the relevant community is.”

Q3: When defining a research topic, do you tend to start with a broad idea or a specific research question?

In a collection of notes on where to start by Don Davis at Columbia University, Davis tells us “First, there is no ‘Right Topic.’”, adding that “Much more important is to find something that is important and genuinely interests you.”

Schmieder shared in the chat event, “I tend to get lost in the details while trying to save the world – not sure really where I start though. :O)” @TheInfoSherpa added, “Depends on the project. The important thing is being able to realize when your topic is too broad or too narrow and may need tweaking. I use the five Ws or PICO(T) to adjust my topic if it’s too broad or too narrow.”

In an online resource , The Writing Center at George Mason University identifies the following six steps to developing a research question, noting significance in that “the specificity of a well-developed research question helps writers avoid the ‘all-about’ paper and work toward supporting a specific, arguable thesis.”

- Choose an interesting general topic

- Do some preliminary research on your general topic

- Consider your audience

- Start asking questions

- Evaluate your question

- Begin your research

USC Libraries’ research guides offer eight strategies for narrowing the research topic : Aspect, Components, Methodology, Place, Relationship, Time, Type, or a Combination of the above.

Q4: What factors help to determine the realistic scope a research topic?

The scope of a research topic refers to the actual amount of research conducted as part of the study. Often the search strategies used in understanding previous research and knowledge on a topic will impact the scope of the current study. A resource from Indiana University offers both an activity for narrowing the search strategy when finding too much information on a topic and an activity for broadening the search strategy when too little information is found.

The Mayfield Handbook of Technical & Scientific Writing identifies scope as an element to be included in the problem statement. Further when discussing problem statements, this resource states, “If you are focusing on a problem, be sure to define and state it specifically enough that you can write about it. Avoid trying to investigate or write about multiple problems or about broad or overly ambitious problems. Vague problem definition leads to unsuccessful proposals and vague, unmanageable documents. Naming a topic is not the same as defining a problem.”

Schmieder identified in the chat several considerations when determining the scope of a research topic, namely “Time, money, interest and commitment, impact to self and others.” @TheInfoSherpa reiterated their use of PICO(T) stating, “PICO(T) is used in the health sciences, but it can be used to identify a manageable scope” and sharing a link to a Georgia Gwinnett College Research Guide on PICOT Questions .

By managing the scope of your research topic, you also define the limitations of your study. According to a USC Libraries’ Research Guide, “The limitations of the study are those characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from your research.” Accepting limitations help maintain a manageable scope moving forward with the project.

Q5/5a: Do you generally conduct research alone or with collaborative authors? What benefits/challenges do collaborators add to the research project?

Despite noting that the majority of his research efforts have been solo, Schmieder did identify benefits to collaboration including “brainstorming, division of labor, speed of execution” and challenges of developing a shared vision, defining roles and responsibilities for the collaborators, and accepting a level of dependence on the others in the group.

In a resource on group writing from The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, both advantages and pitfalls are discussed. Looking to the positive, this resource notes that “Writing in a group can have many benefits: multiple brains are better than one, both for generating ideas and for getting a job done.”

Yale University’s Office of the Provost has established, as part of its Academic Integrity policies, Guidance on Authorship in Scholarly or Scientific Publications to assist researchers in understanding authorship standards as well as attribution expectations.

In times when authorship turns sour , the University of California, San Francisco offers the following advice to reach a resolution among collaborative authors:

- Address emotional issues directly

- Elicit the problem author’s emotions

- Acknowledge the problem author’s emotions

- Express your own emotions as “I feel …”

- Set boundaries

- Try to find common ground

- Get agreement on process

- Involve a neutral third party

Q6: What other advice can you share about defining a research project?

Schmieder answered with question with personal advice to “Choose a topic of interest. If you aren’t interested in the topic, you will either not stay motivated to complete it or you will be miserable in the process and not produce the best results from your efforts.”

For further guidance and advice, the following resources may prove useful:

- 15 Steps to Good Research (Georgetown University Library)

- Advice for Researchers and Students (Tao Xie and University of Illinois)

- Develop a research statement for yourself (University of Pennsylvania)

Whatever your next research project, hopefully these tips and resources help you to define it in a way that leads to greater success and better writing.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Pharmacol Pharmacother

- v.4(2); Apr-Jun 2013

The critical steps for successful research: The research proposal and scientific writing: (A report on the pre-conference workshop held in conjunction with the 64 th annual conference of the Indian Pharmaceutical Congress-2012)

Pitchai balakumar.

Pharmacology Unit, Faculty of Pharmacy, AIMST University, Semeling, 08100 Bedong. Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia

Mohammed Naseeruddin Inamdar

1 Department of Pharmacology, Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

2 Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, USA

An interactive workshop on ‘The Critical Steps for Successful Research: The Research Proposal and Scientific Writing’ was conducted in conjunction with the 64 th Annual Conference of the Indian Pharmaceutical Congress-2012 at Chennai, India. In essence, research is performed to enlighten our understanding of a contemporary issue relevant to the needs of society. To accomplish this, a researcher begins search for a novel topic based on purpose, creativity, critical thinking, and logic. This leads to the fundamental pieces of the research endeavor: Question, objective, hypothesis, experimental tools to test the hypothesis, methodology, and data analysis. When correctly performed, research should produce new knowledge. The four cornerstones of good research are the well-formulated protocol or proposal that is well executed, analyzed, discussed and concluded. This recent workshop educated researchers in the critical steps involved in the development of a scientific idea to its successful execution and eventual publication.

INTRODUCTION

Creativity and critical thinking are of particular importance in scientific research. Basically, research is original investigation undertaken to gain knowledge and understand concepts in major subject areas of specialization, and includes the generation of ideas and information leading to new or substantially improved scientific insights with relevance to the needs of society. Hence, the primary objective of research is to produce new knowledge. Research is both theoretical and empirical. It is theoretical because the starting point of scientific research is the conceptualization of a research topic and development of a research question and hypothesis. Research is empirical (practical) because all of the planned studies involve a series of observations, measurements, and analyses of data that are all based on proper experimental design.[ 1 – 9 ]

The subject of this report is to inform readers of the proceedings from a recent workshop organized by the 64 th Annual conference of the ‘ Indian Pharmaceutical Congress ’ at SRM University, Chennai, India, from 05 to 06 December 2012. The objectives of the workshop titled ‘The Critical Steps for Successful Research: The Research Proposal and Scientific Writing,’ were to assist participants in developing a strong fundamental understanding of how best to develop a research or study protocol, and communicate those research findings in a conference setting or scientific journal. Completing any research project requires meticulous planning, experimental design and execution, and compilation and publication of findings in the form of a research paper. All of these are often unfamiliar to naïve researchers; thus, the purpose of this workshop was to teach participants to master the critical steps involved in the development of an idea to its execution and eventual publication of the results (See the last section for a list of learning objectives).

THE STRUCTURE OF THE WORKSHOP

The two-day workshop was formatted to include key lectures and interactive breakout sessions that focused on protocol development in six subject areas of the pharmaceutical sciences. This was followed by sessions on scientific writing. DAY 1 taught the basic concepts of scientific research, including: (1) how to formulate a topic for research and to describe the what, why , and how of the protocol, (2) biomedical literature search and review, (3) study designs, statistical concepts, and result analyses, and (4) publication ethics. DAY 2 educated the attendees on the basic elements and logistics of writing a scientific paper and thesis, and preparation of poster as well as oral presentations.

The final phase of the workshop was the ‘Panel Discussion,’ including ‘Feedback/Comments’ by participants. There were thirteen distinguished speakers from India and abroad. Approximately 120 post-graduate and pre-doctoral students, young faculty members, and scientists representing industries attended the workshop from different parts of the country. All participants received a printed copy of the workshop manual and supporting materials on statistical analyses of data.

THE BASIC CONCEPTS OF RESEARCH: THE KEY TO GETTING STARTED IN RESEARCH

A research project generally comprises four key components: (1) writing a protocol, (2) performing experiments, (3) tabulating and analyzing data, and (4) writing a thesis or manuscript for publication.

Fundamentals in the research process

A protocol, whether experimental or clinical, serves as a navigator that evolves from a basic outline of the study plan to become a qualified research or grant proposal. It provides the structural support for the research. Dr. G. Jagadeesh (US FDA), the first speaker of the session, spoke on ‘ Fundamentals in research process and cornerstones of a research project .’ He discussed at length the developmental and structural processes in preparing a research protocol. A systematic and step-by-step approach is necessary in planning a study. Without a well-designed protocol, there would be a little chance for successful completion of a research project or an experiment.

Research topic

The first and the foremost difficult task in research is to identify a topic for investigation. The research topic is the keystone of the entire scientific enterprise. It begins the project, drives the entire study, and is crucial for moving the project forward. It dictates the remaining elements of the study [ Table 1 ] and thus, it should not be too narrow or too broad or unfocused. Because of these potential pitfalls, it is essential that a good or novel scientific idea be based on a sound concept. Creativity, critical thinking, and logic are required to generate new concepts and ideas in solving a research problem. Creativity involves critical thinking and is associated with generating many ideas. Critical thinking is analytical, judgmental, and involves evaluating choices before making a decision.[ 4 ] Thus, critical thinking is convergent type thinking that narrows and refines those divergent ideas and finally settles to one idea for an in-depth study. The idea on which a research project is built should be novel, appropriate to achieve within the existing conditions, and useful to the society at large. Therefore, creativity and critical thinking assist biomedical scientists in research that results in funding support, novel discovery, and publication.[ 1 , 4 ]

Elements of a study protocol

Research question

The next most crucial aspect of a study protocol is identifying a research question. It should be a thought-provoking question. The question sets the framework. It emerges from the title, findings/results, and problems observed in previous studies. Thus, mastering the literature, attendance at conferences, and discussion in journal clubs/seminars are sources for developing research questions. Consider the following example in developing related research questions from the research topic.

Hepatoprotective activity of Terminalia arjuna and Apium graveolens on paracetamol-induced liver damage in albino rats.

How is paracetamol metabolized in the body? Does it involve P450 enzymes? How does paracetamol cause liver injury? What are the mechanisms by which drugs can alleviate liver damage? What biochemical parameters are indicative of liver injury? What major endogenous inflammatory molecules are involved in paracetamol-induced liver damage?

A research question is broken down into more precise objectives. The objectives lead to more precise methods and definition of key terms. The objectives should be SMART-Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-framed,[ 10 ] and should cover the entire breadth of the project. The objectives are sometimes organized into hierarchies: Primary, secondary, and exploratory; or simply general and specific. Study the following example:

To evaluate the safety and tolerability of single oral doses of compound X in normal volunteers.

To assess the pharmacokinetic profile of compound X following single oral doses.

To evaluate the incidence of peripheral edema reported as an adverse event.

The objectives and research questions are then formulated into a workable or testable hypothesis. The latter forces us to think carefully about what comparisons will be needed to answer the research question, and establishes the format for applying statistical tests to interpret the results. The hypothesis should link a process to an existing or postulated biologic pathway. A hypothesis is written in a form that can yield measurable results. Studies that utilize statistics to compare groups of data should have a hypothesis. Consider the following example:

- The hepatoprotective activity of Terminalia arjuna is superior to that of Apium graveolens against paracetamol-induced liver damage in albino rats.

All biological research, including discovery science, is hypothesis-driven. However, not all studies need be conducted with a hypothesis. For example, descriptive studies (e.g., describing characteristics of a plant, or a chemical compound) do not need a hypothesis.[ 1 ]

Relevance of the study

Another important section to be included in the protocol is ‘significance of the study.’ Its purpose is to justify the need for the research that is being proposed (e.g., development of a vaccine for a disease). In summary, the proposed study should demonstrate that it represents an advancement in understanding and that the eventual results will be meaningful, contribute to the field, and possibly even impact society.

Biomedical literature

A literature search may be defined as the process of examining published sources of information on a research or review topic, thesis, grant application, chemical, drug, disease, or clinical trial, etc. The quantity of information available in print or electronically (e.g., the internet) is immense and growing with time. A researcher should be familiar with the right kinds of databases and search engines to extract the needed information.[ 3 , 6 ]

Dr. P. Balakumar (Institute of Pharmacy, Rajendra Institute of Technology and Sciences, Sirsa, Haryana; currently, Faculty of Pharmacy, AIMST University, Malaysia) spoke on ‘ Biomedical literature: Searching, reviewing and referencing .’ He schematically explained the basis of scientific literature, designing a literature review, and searching literature. After an introduction to the genesis and diverse sources of scientific literature searches, the use of PubMed, one of the premier databases used for biomedical literature searches world-wide, was illustrated with examples and screenshots. Several companion databases and search engines are also used for finding information related to health sciences, and they include Embase, Web of Science, SciFinder, The Cochrane Library, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, Scopus, and Google Scholar.[ 3 ] Literature searches using alternative interfaces for PubMed such as GoPubMed, Quertle, PubFocus, Pubget, and BibliMed were discussed. The participants were additionally informed of databases on chemistry, drugs and drug targets, clinical trials, toxicology, and laboratory animals (reviewed in ref[ 3 ]).

Referencing and bibliography are essential in scientific writing and publication.[ 7 ] Referencing systems are broadly classified into two major types, such as Parenthetical and Notation systems. Parenthetical referencing is also known as Harvard style of referencing, while Vancouver referencing style and ‘Footnote’ or ‘Endnote’ are placed under Notation referencing systems. The participants were educated on each referencing system with examples.

Bibliography management

Dr. Raj Rajasekaran (University of California at San Diego, CA, USA) enlightened the audience on ‘ bibliography management ’ using reference management software programs such as Reference Manager ® , Endnote ® , and Zotero ® for creating and formatting bibliographies while writing a manuscript for publication. The discussion focused on the use of bibliography management software in avoiding common mistakes such as incomplete references. Important steps in bibliography management, such as creating reference libraries/databases, searching for references using PubMed/Google scholar, selecting and transferring selected references into a library, inserting citations into a research article and formatting bibliographies, were presented. A demonstration of Zotero®, a freely available reference management program, included the salient features of the software, adding references from PubMed using PubMed ID, inserting citations and formatting using different styles.

Writing experimental protocols

The workshop systematically instructed the participants in writing ‘ experimental protocols ’ in six disciplines of Pharmaceutical Sciences.: (1) Pharmaceutical Chemistry (presented by Dr. P. V. Bharatam, NIPER, Mohali, Punjab); (2) Pharmacology (presented by Dr. G. Jagadeesh and Dr. P. Balakumar); (3) Pharmaceutics (presented by Dr. Jayant Khandare, Piramal Life Sciences, Mumbai); (4) Pharmacy Practice (presented by Dr. Shobha Hiremath, Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Bengaluru); (5) Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry (presented by Dr. Salma Khanam, Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Bengaluru); and (6) Pharmaceutical Analysis (presented by Dr. Saranjit Singh, NIPER, Mohali, Punjab). The purpose of the research plan is to describe the what (Specific Aims/Objectives), why (Background and Significance), and how (Design and Methods) of the proposal.

The research plan should answer the following questions: (a) what do you intend to do; (b) what has already been done in general, and what have other researchers done in the field; (c) why is this worth doing; (d) how is it innovative; (e) what will this new work add to existing knowledge; and (f) how will the research be accomplished?

In general, the format used by the faculty in all subjects is shown in Table 2 .

Elements of a research protocol

Biostatistics

Biostatistics is a key component of biomedical research. Highly reputed journals like The Lancet, BMJ, Journal of the American Medical Association, and many other biomedical journals include biostatisticians on their editorial board or reviewers list. This indicates that a great importance is given for learning and correctly employing appropriate statistical methods in biomedical research. The post-lunch session on day 1 of the workshop was largely committed to discussion on ‘ Basic biostatistics .’ Dr. R. Raveendran (JIPMER, Puducherry) and Dr. Avijit Hazra (PGIMER, Kolkata) reviewed, in parallel sessions, descriptive statistics, probability concepts, sample size calculation, choosing a statistical test, confidence intervals, hypothesis testing and ‘ P ’ values, parametric and non-parametric statistical tests, including analysis of variance (ANOVA), t tests, Chi-square test, type I and type II errors, correlation and regression, and summary statistics. This was followed by a practice and demonstration session. Statistics CD, compiled by Dr. Raveendran, was distributed to the participants before the session began and was demonstrated live. Both speakers worked on a variety of problems that involved both clinical and experimental data. They discussed through examples the experimental designs encountered in a variety of studies and statistical analyses performed for different types of data. For the benefit of readers, we have summarized statistical tests applied frequently for different experimental designs and post-hoc tests [ Figure 1 ].

Conceptual framework for statistical analyses of data. Of the two kinds of variables, qualitative (categorical) and quantitative (numerical), qualitative variables (nominal or ordinal) are not normally distributed. Numerical data that come from normal distributions are analyzed using parametric tests, if not; the data are analyzed using non-parametric tests. The most popularly used Student's t -test compares the means of two populations, data for this test could be paired or unpaired. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) is used to compare the means of three or more independent populations that are normally distributed. Applying t test repeatedly in pair (multiple comparison), to compare the means of more than two populations, will increase the probability of type I error (false positive). In this case, for proper interpretation, we need to adjust the P values. Repeated measures ANOVA is used to compare the population means if more than two observations coming from same subject over time. The null hypothesis is rejected with a ‘ P ’ value of less than 0.05, and the difference in population means is considered to be statistically significant. Subsequently, appropriate post-hoc tests are used for pairwise comparisons of population means. Two-way or three-way ANOVA are considered if two (diet, dose) or three (diet, dose, strain) independent factors, respectively, are analyzed in an experiment (not described in the Figure). Categorical nominal unmatched variables (counts or frequencies) are analyzed by Chi-square test (not shown in the Figure)

Research and publication ethics

The legitimate pursuit of scientific creativity is unfortunately being marred by a simultaneous increase in scientific misconduct. A disproportionate share of allegations involves scientists of many countries, and even from respected laboratories. Misconduct destroys faith in science and scientists and creates a hierarchy of fraudsters. Investigating misconduct also steals valuable time and resources. In spite of these facts, most researchers are not aware of publication ethics.

Day 1 of the workshop ended with a presentation on ‘ research and publication ethics ’ by Dr. M. K. Unnikrishnan (College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal University, Manipal). He spoke on the essentials of publication ethics that included plagiarism (attempting to take credit of the work of others), self-plagiarism (multiple publications by an author on the same content of work with slightly different wordings), falsification (manipulation of research data and processes and omitting critical data or results), gift authorship (guest authorship), ghostwriting (someone other than the named author (s) makes a major contribution), salami publishing (publishing many papers, with minor differences, from the same study), and sabotage (distracting the research works of others to halt their research completion). Additionally, Dr. Unnikrishnan pointed out the ‘ Ingelfinger rule ’ of stipulating that a scientist must not submit the same original research in two different journals. He also advised the audience that authorship is not just credit for the work but also responsibility for scientific contents of a paper. Although some Indian Universities are instituting preventive measures (e.g., use of plagiarism detecting software, Shodhganga digital archiving of doctoral theses), Dr. Unnikrishnan argued for a great need to sensitize young researchers on the nature and implications of scientific misconduct. Finally, he discussed methods on how editors and peer reviewers should ethically conduct themselves while managing a manuscript for publication.

SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION: THE KEY TO SUCCESSFUL SELLING OF FINDINGS

Research outcomes are measured through quality publications. Scientists must not only ‘do’ science but must ‘write’ science. The story of the project must be told in a clear, simple language weaving in previous work done in the field, answering the research question, and addressing the hypothesis set forth at the beginning of the study. Scientific publication is an organic process of planning, researching, drafting, revising, and updating the current knowledge for future perspectives. Writing a research paper is no easier than the research itself. The lectures of Day 2 of the workshop dealt with the basic elements and logistics of writing a scientific paper.

An overview of paper structure and thesis writing

Dr. Amitabh Prakash (Adis, Auckland, New Zealand) spoke on ‘ Learning how to write a good scientific paper .’ His presentation described the essential components of an original research paper and thesis (e.g., introduction, methods, results, and discussion [IMRaD]) and provided guidance on the correct order, in which data should appear within these sections. The characteristics of a good abstract and title and the creation of appropriate key words were discussed. Dr. Prakash suggested that the ‘title of a paper’ might perhaps have a chance to make a good impression, and the title might be either indicative (title that gives the purpose of the study) or declarative (title that gives the study conclusion). He also suggested that an abstract is a succinct summary of a research paper, and it should be specific, clear, and concise, and should have IMRaD structure in brief, followed by key words. Selection of appropriate papers to be cited in the reference list was also discussed. Various unethical authorships were enumerated, and ‘The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship’ was explained ( http://www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html ; also see Table 1 in reference #9). The session highlighted the need for transparency in medical publication and provided a clear description of items that needed to be included in the ‘Disclosures’ section (e.g., sources of funding for the study and potential conflicts of interest of all authors, etc.) and ‘Acknowledgements’ section (e.g., writing assistance and input from all individuals who did not meet the authorship criteria). The final part of the presentation was devoted to thesis writing, and Dr. Prakash provided the audience with a list of common mistakes that are frequently encountered when writing a manuscript.

The backbone of a study is description of results through Text, Tables, and Figures. Dr. S. B. Deshpande (Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India) spoke on ‘ Effective Presentation of Results .’ The Results section deals with the observations made by the authors and thus, is not hypothetical. This section is subdivided into three segments, that is, descriptive form of the Text, providing numerical data in Tables, and visualizing the observations in Graphs or Figures. All these are arranged in a sequential order to address the question hypothesized in the Introduction. The description in Text provides clear content of the findings highlighting the observations. It should not be the repetition of facts in tables or graphs. Tables are used to summarize or emphasize descriptive content in the text or to present the numerical data that are unrelated. Illustrations should be used when the evidence bearing on the conclusions of a paper cannot be adequately presented in a written description or in a Table. Tables or Figures should relate to each other logically in sequence and should be clear by themselves. Furthermore, the discussion is based entirely on these observations. Additionally, how the results are applied to further research in the field to advance our understanding of research questions was discussed.

Dr. Peush Sahni (All-India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi) spoke on effectively ‘ structuring the Discussion ’ for a research paper. The Discussion section deals with a systematic interpretation of study results within the available knowledge. He said the section should begin with the most important point relating to the subject studied, focusing on key issues, providing link sentences between paragraphs, and ensuring the flow of text. Points were made to avoid history, not repeat all the results, and provide limitations of the study. The strengths and novel findings of the study should be provided in the discussion, and it should open avenues for future research and new questions. The Discussion section should end with a conclusion stating the summary of key findings. Dr. Sahni gave an example from a published paper for writing a Discussion. In another presentation titled ‘ Writing an effective title and the abstract ,’ Dr. Sahni described the important components of a good title, such as, it should be simple, concise, informative, interesting and eye-catching, accurate and specific about the paper's content, and should state the subject in full indicating study design and animal species. Dr. Sahni explained structured (IMRaD) and unstructured abstracts and discussed a few selected examples with the audience.

Language and style in publication

The next lecture of Dr. Amitabh Prakash on ‘ Language and style in scientific writing: Importance of terseness, shortness and clarity in writing ’ focused on the actual sentence construction, language, grammar and punctuation in scientific manuscripts. His presentation emphasized the importance of brevity and clarity in the writing of manuscripts describing biomedical research. Starting with a guide to the appropriate construction of sentences and paragraphs, attendees were given a brief overview of the correct use of punctuation with interactive examples. Dr. Prakash discussed common errors in grammar and proactively sought audience participation in correcting some examples. Additional discussion was centered on discouraging the use of redundant and expendable words, jargon, and the use of adjectives with incomparable words. The session ended with a discussion of words and phrases that are commonly misused (e.g., data vs . datum, affect vs . effect, among vs . between, dose vs . dosage, and efficacy/efficacious vs . effective/effectiveness) in biomedical research manuscripts.

Working with journals

The appropriateness in selecting the journal for submission and acceptance of the manuscript should be determined by the experience of an author. The corresponding author must have a rationale in choosing the appropriate journal, and this depends upon the scope of the study and the quality of work performed. Dr. Amitabh Prakash spoke on ‘ Working with journals: Selecting a journal, cover letter, peer review process and impact factor ’ by instructing the audience in assessing the true value of a journal, understanding principles involved in the peer review processes, providing tips on making an initial approach to the editorial office, and drafting an appropriate cover letter to accompany the submission. His presentation defined the metrics that are most commonly used to measure journal quality (e.g., impact factor™, Eigenfactor™ score, Article Influence™ score, SCOPUS 2-year citation data, SCImago Journal Rank, h-Index, etc.) and guided attendees on the relative advantages and disadvantages of using each metric. Factors to consider when assessing journal quality were discussed, and the audience was educated on the ‘green’ and ‘gold’ open access publication models. Various peer review models (e.g., double-blind, single-blind, non-blind) were described together with the role of the journal editor in assessing manuscripts and selecting suitable reviewers. A typical checklist sent to referees was shared with the attendees, and clear guidance was provided on the best way to address referee feedback. The session concluded with a discussion of the potential drawbacks of the current peer review system.

Poster and oral presentations at conferences

Posters have become an increasingly popular mode of presentation at conferences, as it can accommodate more papers per meeting, has no time constraint, provides a better presenter-audience interaction, and allows one to select and attend papers of interest. In Figure 2 , we provide instructions, design, and layout in preparing a scientific poster. In the final presentation, Dr. Sahni provided the audience with step-by-step instructions on how to write and format posters for layout, content, font size, color, and graphics. Attendees were given specific guidance on the format of text on slides, the use of color, font type and size, and the use of illustrations and multimedia effects. Moreover, the importance of practical tips while delivering oral or poster presentation was provided to the audience, such as speak slowly and clearly, be informative, maintain eye contact, and listen to the questions from judges/audience carefully before coming up with an answer.

Guidelines and design to scientific poster presentation. The objective of scientific posters is to present laboratory work in scientific meetings. A poster is an excellent means of communicating scientific work, because it is a graphic representation of data. Posters should have focus points, and the intended message should be clearly conveyed through simple sections: Text, Tables, and Graphs. Posters should be clear, succinct, striking, and eye-catching. Colors should be used only where necessary. Use one font (Arial or Times New Roman) throughout. Fancy fonts should be avoided. All headings should have font size of 44, and be in bold capital letters. Size of Title may be a bit larger; subheading: Font size of 36, bold and caps. References and Acknowledgments, if any, should have font size of 24. Text should have font size between 24 and 30, in order to be legible from a distance of 3 to 6 feet. Do not use lengthy notes

PANEL DISCUSSION: FEEDBACK AND COMMENTS BY PARTICIPANTS

After all the presentations were made, Dr. Jagadeesh began a panel discussion that included all speakers. The discussion was aimed at what we do currently and could do in the future with respect to ‘developing a research question and then writing an effective thesis proposal/protocol followed by publication.’ Dr. Jagadeesh asked the following questions to the panelists, while receiving questions/suggestions from the participants and panelists.

- Does a Post-Graduate or Ph.D. student receive adequate training, either through an institutional course, a workshop of the present nature, or from the guide?

- Are these Post-Graduates self-taught (like most of us who learnt the hard way)?

- How are these guides trained? How do we train them to become more efficient mentors?

- Does a Post-Graduate or Ph.D. student struggle to find a method (s) to carry out studies? To what extent do seniors/guides help a post graduate overcome technical difficulties? How difficult is it for a student to find chemicals, reagents, instruments, and technical help in conducting studies?

- Analyses of data and interpretation: Most students struggle without adequate guidance.

- Thesis and publications frequently feature inadequate/incorrect statistical analyses and representation of data in tables/graphs. The student, their guide, and the reviewers all share equal responsibility.

- Who initiates and drafts the research paper? The Post-Graduate or their guide?

- What kind of assistance does a Post-Graduate get from the guide in finalizing a paper for publication?

- Does the guide insist that each Post-Graduate thesis yield at least one paper, and each Ph.D. thesis more than two papers, plus a review article?

The panelists and audience expressed a variety of views, but were unable to arrive at a decisive conclusion.

WHAT HAVE THE PARTICIPANTS LEARNED?

At the end of this fast-moving two-day workshop, the participants had opportunities in learning the following topics:

- Sequential steps in developing a study protocol, from choosing a research topic to developing research questions and a hypothesis.

- Study protocols on different topics in their subject of specialization

- Searching and reviewing the literature

- Appropriate statistical analyses in biomedical research

- Scientific ethics in publication

- Writing and understanding the components of a research paper (IMRaD)

- Recognizing the value of good title, running title, abstract, key words, etc

- Importance of Tables and Figures in the Results section, and their importance in describing findings

- Evidence-based Discussion in a research paper

- Language and style in writing a paper and expert tips on getting it published

- Presentation of research findings at a conference (oral and poster).

Overall, the workshop was deemed very helpful to participants. The participants rated the quality of workshop from “ satisfied ” to “ very satisfied .” A significant number of participants were of the opinion that the time allotted for each presentation was short and thus, be extended from the present two days to four days with adequate time to ask questions. In addition, a ‘hands-on’ session should be introduced for writing a proposal and manuscript. A large number of attendees expressed their desire to attend a similar workshop, if conducted, in the near future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully express our gratitude to the Organizing Committee, especially Professors K. Chinnasamy, B. G. Shivananda, N. Udupa, Jerad Suresh, Padma Parekh, A. P. Basavarajappa, Mr. S. V. Veerramani, Mr. J. Jayaseelan, and all volunteers of the SRM University. We thank Dr. Thomas Papoian (US FDA) for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The opinions expressed herein are those of Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Food and Drug Administration

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

What is Research: Definition, Methods, Types & Examples

The search for knowledge is closely linked to the object of study; that is, to the reconstruction of the facts that will provide an explanation to an observed event and that at first sight can be considered as a problem. It is very human to seek answers and satisfy our curiosity. Let’s talk about research.

Content Index

What is Research?

What are the characteristics of research.

- Comparative analysis chart

Qualitative methods

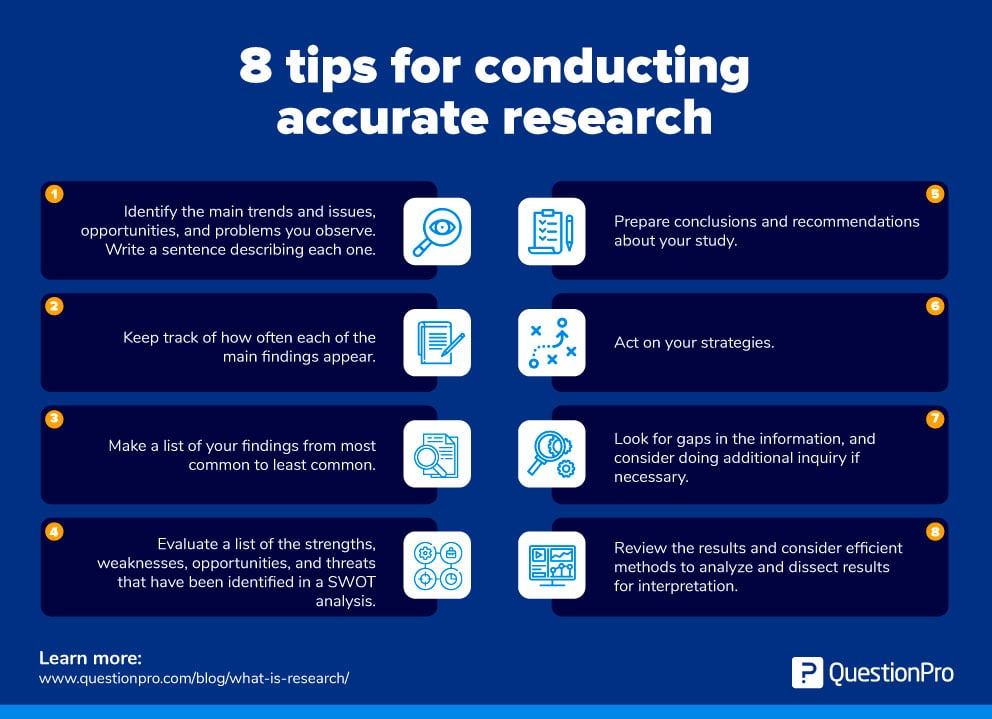

Quantitative methods, 8 tips for conducting accurate research.

Research is the careful consideration of study regarding a particular concern or research problem using scientific methods. According to the American sociologist Earl Robert Babbie, “research is a systematic inquiry to describe, explain, predict, and control the observed phenomenon. It involves inductive and deductive methods.”

Inductive methods analyze an observed event, while deductive methods verify the observed event. Inductive approaches are associated with qualitative research , and deductive methods are more commonly associated with quantitative analysis .

Research is conducted with a purpose to:

- Identify potential and new customers

- Understand existing customers

- Set pragmatic goals

- Develop productive market strategies

- Address business challenges

- Put together a business expansion plan

- Identify new business opportunities

- Good research follows a systematic approach to capture accurate data. Researchers need to practice ethics and a code of conduct while making observations or drawing conclusions.

- The analysis is based on logical reasoning and involves both inductive and deductive methods.

- Real-time data and knowledge is derived from actual observations in natural settings.

- There is an in-depth analysis of all data collected so that there are no anomalies associated with it.

- It creates a path for generating new questions. Existing data helps create more research opportunities.

- It is analytical and uses all the available data so that there is no ambiguity in inference.

- Accuracy is one of the most critical aspects of research. The information must be accurate and correct. For example, laboratories provide a controlled environment to collect data. Accuracy is measured in the instruments used, the calibrations of instruments or tools, and the experiment’s final result.

What is the purpose of research?

There are three main purposes:

- Exploratory: As the name suggests, researchers conduct exploratory studies to explore a group of questions. The answers and analytics may not offer a conclusion to the perceived problem. It is undertaken to handle new problem areas that haven’t been explored before. This exploratory data analysis process lays the foundation for more conclusive data collection and analysis.

LEARN ABOUT: Descriptive Analysis

- Descriptive: It focuses on expanding knowledge on current issues through a process of data collection. Descriptive research describe the behavior of a sample population. Only one variable is required to conduct the study. The three primary purposes of descriptive studies are describing, explaining, and validating the findings. For example, a study conducted to know if top-level management leaders in the 21st century possess the moral right to receive a considerable sum of money from the company profit.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

- Explanatory: Causal research or explanatory research is conducted to understand the impact of specific changes in existing standard procedures. Running experiments is the most popular form. For example, a study that is conducted to understand the effect of rebranding on customer loyalty.

Here is a comparative analysis chart for a better understanding:

| Approach used | Unstructured | Structured | Highly structured |

| Conducted through | Asking questions | Asking questions | By using hypotheses. |

| Time | Early stages of decision making | Later stages of decision making | Later stages of decision making |

It begins by asking the right questions and choosing an appropriate method to investigate the problem. After collecting answers to your questions, you can analyze the findings or observations to draw reasonable conclusions.

When it comes to customers and market studies, the more thorough your questions, the better the analysis. You get essential insights into brand perception and product needs by thoroughly collecting customer data through surveys and questionnaires . You can use this data to make smart decisions about your marketing strategies to position your business effectively.

To make sense of your study and get insights faster, it helps to use a research repository as a single source of truth in your organization and manage your research data in one centralized data repository .

Types of research methods and Examples

Research methods are broadly classified as Qualitative and Quantitative .

Both methods have distinctive properties and data collection methods .

Qualitative research is a method that collects data using conversational methods, usually open-ended questions . The responses collected are essentially non-numerical. This method helps a researcher understand what participants think and why they think in a particular way.

Types of qualitative methods include:

- One-to-one Interview

- Focus Groups

- Ethnographic studies

- Text Analysis

Quantitative methods deal with numbers and measurable forms . It uses a systematic way of investigating events or data. It answers questions to justify relationships with measurable variables to either explain, predict, or control a phenomenon.

Types of quantitative methods include:

- Survey research

- Descriptive research

- Correlational research

LEARN MORE: Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

Remember, it is only valuable and useful when it is valid, accurate, and reliable. Incorrect results can lead to customer churn and a decrease in sales.

It is essential to ensure that your data is:

- Valid – founded, logical, rigorous, and impartial.

- Accurate – free of errors and including required details.

- Reliable – other people who investigate in the same way can produce similar results.

- Timely – current and collected within an appropriate time frame.

- Complete – includes all the data you need to support your business decisions.

Gather insights

- Identify the main trends and issues, opportunities, and problems you observe. Write a sentence describing each one.

- Keep track of the frequency with which each of the main findings appears.

- Make a list of your findings from the most common to the least common.

- Evaluate a list of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats identified in a SWOT analysis .

- Prepare conclusions and recommendations about your study.

- Act on your strategies

- Look for gaps in the information, and consider doing additional inquiry if necessary

- Plan to review the results and consider efficient methods to analyze and interpret results.

Review your goals before making any conclusions about your study. Remember how the process you have completed and the data you have gathered help answer your questions. Ask yourself if what your analysis revealed facilitates the identification of your conclusions and recommendations.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR SOFTWARE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

When You Have Something Important to Say, You want to Shout it From the Rooftops

Jun 28, 2024

The Item I Failed to Leave Behind — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jun 25, 2024

Feedback Loop: What It Is, Types & How It Works?

Jun 21, 2024

QuestionPro Thrive: A Space to Visualize & Share the Future of Technology

Jun 18, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.

In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues.

Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 3: Review previous research

In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute.

Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research:

- Position 1 requires you to build on or extend a set of existing ideas; that means saying something like: ‘Person A has argued that X is true about gender; this implies Y, which has not yet been tested. My project will test Y, and if I find evidence to support it, that will change the way we understand gender.’

- Position 2 is to argue that there is a gap in existing knowledge, either because previous research has reached conflicting conclusions or has failed to consider something important. For example, one could say that research on middle schoolers and gender has been limited by being conducted primarily in coeducational environments, and that findings might differ dramatically if research were conducted in more schools where the student body was all-male or all-female.

Your overall goal in this step of the process is to show that your research will be part of a larger conversation: that is, how your project flows from what’s already known, and how it advances, extends or challenges that existing body of knowledge. That will be the contribution of your project, and it constitutes the motivation for your research.

Two things are worth mentioning about your search for sources of relevant previous research. First, you needn’t look only at studies on your precise topic. For example, if you want to study gender-identity formation in schools, you shouldn’t restrict yourself to studies of schools; the empirical setting (schools) is secondary to the larger social process that interests you (how people form gender identity). That process occurs in many different settings, so cast a wide net. Second, be sure to use legitimate sources – meaning publications that have been through some sort of vetting process, whether that involves peer review (as with academic journal articles you might find via Google Scholar) or editorial review (as you’d find in well-known mass media publications, such as The Economist or The Washington Post ). What you’ll want to avoid is using unvetted sources such as personal blogs or Wikipedia. Why? Because anybody can write anything in those forums, and there is no way to know – unless you’re already an expert – if the claims you find there are accurate. Often, they’re not.

Step 4: Choose your data and methods

Whatever your research question is, eventually you’ll need to consider which data source and analytical strategy are most likely to provide the answers you’re seeking. One starting point is to consider whether your question would be best addressed by qualitative data (such as interviews, observations or historical records), quantitative data (such as surveys or census records) or some combination of both. Your ideas about data sources will, in turn, suggest options for analytical methods.

You might need to collect your own data, or you might find everything you need readily available in an existing dataset someone else has created. A great place to start is with a research librarian: university libraries always have them and, at public universities, those librarians can work with the public, including people who aren’t affiliated with the university. If you don’t happen to have a public university and its library close at hand, an ordinary public library can still be a good place to start: the librarians are often well versed in accessing data sources that might be relevant to your study, such as the census, or historical archives, or the Survey of Consumer Finances.

Because your task at this point is to plan research, rather than conduct it, the purpose of this step is not to commit you irrevocably to a course of action. Instead, your goal here is to think through a feasible approach to answering your research question. You’ll need to find out, for example, whether the data you want exist; if not, do you have a realistic chance of gathering the data yourself, or would it be better to modify your research question? In terms of analysis, would your strategy require you to apply statistical methods? If so, do you have those skills? If not, do you have time to learn them, or money to hire a research assistant to run the analysis for you?

Please be aware that qualitative methods in particular are not the casual undertaking they might appear to be. Many people make the mistake of thinking that only quantitative data and methods are scientific and systematic, while qualitative methods are just a fancy way of saying: ‘I talked to some people, read some old newspapers, and drew my own conclusions.’ Nothing could be further from the truth. In the final section of this guide, you’ll find some links to resources that will provide more insight on standards and procedures governing qualitative research, but suffice it to say: there are rules about what constitutes legitimate evidence and valid analytical procedure for qualitative data, just as there are for quantitative data.

Circle back and consider revising your initial plans

As you work through these four steps in planning your project, it’s perfectly normal to circle back and revise. Research planning is rarely a linear process. It’s also common for new and unexpected avenues to suggest themselves. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen wrote in 1908 : ‘The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.’ That’s as true of research planning as it is of a completed project. Try to enjoy the horizons that open up for you in this process, rather than becoming overwhelmed; the four steps, along with the two exercises that follow, will help you focus your plan and make it manageable.

Key points – How to plan a research project

- Planning a research project is essential no matter your academic level or field of study. There is no one ‘best’ way to design research, but there are certain guidelines that can be helpfully applied across disciplines.

- Orient yourself to knowledge-creation. Make the shift from being a consumer of information to being a producer of information.

- Define your research question. Your question frames the rest of your project, sets the scope, and determines the kinds of answers you can find.

- Review previous research on your question. Survey the existing body of relevant knowledge to ensure that your research will be part of a larger conversation.

- Choose your data and methods. For instance, will you be collecting qualitative data, via interviews, or numerical data, via surveys?

- Circle back and consider revising your initial plans. Expect your research question in particular to undergo multiple rounds of refinement as you learn more about your topic.

Good research questions tend to beget more questions. This can be frustrating for those who want to get down to business right away. Try to make room for the unexpected: this is usually how knowledge advances. Many of the most significant discoveries in human history have been made by people who were looking for something else entirely. There are ways to structure your research planning process without over-constraining yourself; the two exercises below are a start, and you can find further methods in the Links and Books section.

The following exercise provides a structured process for advancing your research project planning. After completing it, you’ll be able to do the following:

- describe clearly and concisely the question you’ve chosen to study

- summarise the state of the art in knowledge about the question, and where your project could contribute new insight

- identify the best strategy for gathering and analysing relevant data

In other words, the following provides a systematic means to establish the building blocks of your research project.

Exercise 1: Definition of research question and sources

This exercise prompts you to select and clarify your general interest area, develop a research question, and investigate sources of information. The annotated bibliography will also help you refine your research question so that you can begin the second assignment, a description of the phenomenon you wish to study.

Jot down a few bullet points in response to these two questions, with the understanding that you’ll probably go back and modify your answers as you begin reading other studies relevant to your topic:

- What will be the general topic of your paper?

- What will be the specific topic of your paper?

b) Research question(s)

Use the following guidelines to frame a research question – or questions – that will drive your analysis. As with Part 1 above, you’ll probably find it necessary to change or refine your research question(s) as you complete future assignments.

- Your question should be phrased so that it can’t be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Your question should have more than one plausible answer.

- Your question should draw relationships between two or more concepts; framing the question in terms of How? or What? often works better than asking Why ?

c) Annotated bibliography

Most or all of your background information should come from two sources: scholarly books and journals, or reputable mass media sources. You might be able to access journal articles electronically through your library, using search engines such as JSTOR and Google Scholar. This can save you a great deal of time compared with going to the library in person to search periodicals. General news sources, such as those accessible through LexisNexis, are acceptable, but should be cited sparingly, since they don’t carry the same level of credibility as scholarly sources. As discussed above, unvetted sources such as blogs and Wikipedia should be avoided, because the quality of the information they provide is unreliable and often misleading.

To create an annotated bibliography, provide the following information for at least 10 sources relevant to your specific topic, using the format suggested below.

Name of author(s):

Publication date:

Title of book, chapter, or article:

If a chapter or article, title of journal or book where they appear:

Brief description of this work, including main findings and methods ( c 75 words):

Summary of how this work contributes to your project ( c 75 words):

Brief description of the implications of this work ( c 25 words):

Identify any gap or controversy in knowledge this work points up, and how your project could address those problems ( c 50 words):

Exercise 2: Towards an analysis

Develop a short statement ( c 250 words) about the kind of data that would be useful to address your research question, and how you’d analyse it. Some questions to consider in writing this statement include:

- What are the central concepts or variables in your project? Offer a brief definition of each.

- Do any data sources exist on those concepts or variables, or would you need to collect data?

- Of the analytical strategies you could apply to that data, which would be the most appropriate to answer your question? Which would be the most feasible for you? Consider at least two methods, noting their advantages or disadvantages for your project.

Links & books

One of the best texts ever written about planning and executing research comes from a source that might be unexpected: a 60-year-old work on urban planning by a self-trained scholar. The classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs (available complete and free of charge via this link ) is worth reading in its entirety just for the pleasure of it. But the final 20 pages – a concluding chapter titled ‘The Kind of Problem a City Is’ – are really about the process of thinking through and investigating a problem. Highly recommended as a window into the craft of research.

Jacobs’s text references an essay on advancing human knowledge by the mathematician Warren Weaver. At the time, Weaver was director of the Rockefeller Foundation, in charge of funding basic research in the natural and medical sciences. Although the essay is titled ‘A Quarter Century in the Natural Sciences’ (1960) and appears at first blush to be merely a summation of one man’s career, it turns out to be something much bigger and more interesting: a meditation on the history of human beings seeking answers to big questions about the world. Weaver goes back to the 17th century to trace the origins of systematic research thinking, with enthusiasm and vivid anecdotes that make the process come alive. The essay is worth reading in its entirety, and is available free of charge via this link .

For those seeking a more in-depth, professional-level discussion of the logic of research design, the political scientist Harvey Starr provides insight in a compact format in the article ‘Cumulation from Proper Specification: Theory, Logic, Research Design, and “Nice” Laws’ (2005). Starr reviews the ‘research triad’, consisting of the interlinked considerations of formulating a question, selecting relevant theories and applying appropriate methods. The full text of the article, published in the scholarly journal Conflict Management and Peace Science , is available, free of charge, via this link .