Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing Strong Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These OWL resources will help you develop and refine the arguments in your writing.

The thesis statement or main claim must be debatable

An argumentative or persuasive piece of writing must begin with a debatable thesis or claim. In other words, the thesis must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions on. If your thesis is something that is generally agreed upon or accepted as fact then there is no reason to try to persuade people.

Example of a non-debatable thesis statement:

This thesis statement is not debatable. First, the word pollution implies that something is bad or negative in some way. Furthermore, all studies agree that pollution is a problem; they simply disagree on the impact it will have or the scope of the problem. No one could reasonably argue that pollution is unambiguously good.

Example of a debatable thesis statement:

This is an example of a debatable thesis because reasonable people could disagree with it. Some people might think that this is how we should spend the nation's money. Others might feel that we should be spending more money on education. Still others could argue that corporations, not the government, should be paying to limit pollution.

Another example of a debatable thesis statement:

In this example there is also room for disagreement between rational individuals. Some citizens might think focusing on recycling programs rather than private automobiles is the most effective strategy.

The thesis needs to be narrow

Although the scope of your paper might seem overwhelming at the start, generally the narrower the thesis the more effective your argument will be. Your thesis or claim must be supported by evidence. The broader your claim is, the more evidence you will need to convince readers that your position is right.

Example of a thesis that is too broad:

There are several reasons this statement is too broad to argue. First, what is included in the category "drugs"? Is the author talking about illegal drug use, recreational drug use (which might include alcohol and cigarettes), or all uses of medication in general? Second, in what ways are drugs detrimental? Is drug use causing deaths (and is the author equating deaths from overdoses and deaths from drug related violence)? Is drug use changing the moral climate or causing the economy to decline? Finally, what does the author mean by "society"? Is the author referring only to America or to the global population? Does the author make any distinction between the effects on children and adults? There are just too many questions that the claim leaves open. The author could not cover all of the topics listed above, yet the generality of the claim leaves all of these possibilities open to debate.

Example of a narrow or focused thesis:

In this example the topic of drugs has been narrowed down to illegal drugs and the detriment has been narrowed down to gang violence. This is a much more manageable topic.

We could narrow each debatable thesis from the previous examples in the following way:

Narrowed debatable thesis 1:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just the amount of money used but also how the money could actually help to control pollution.

Narrowed debatable thesis 2:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just what the focus of a national anti-pollution campaign should be but also why this is the appropriate focus.

Qualifiers such as " typically ," " generally ," " usually ," or " on average " also help to limit the scope of your claim by allowing for the almost inevitable exception to the rule.

Types of claims

Claims typically fall into one of four categories. Thinking about how you want to approach your topic, or, in other words, what type of claim you want to make, is one way to focus your thesis on one particular aspect of your broader topic.

Claims of fact or definition: These claims argue about what the definition of something is or whether something is a settled fact. Example:

Claims of cause and effect: These claims argue that one person, thing, or event caused another thing or event to occur. Example:

Claims about value: These are claims made of what something is worth, whether we value it or not, how we would rate or categorize something. Example:

Claims about solutions or policies: These are claims that argue for or against a certain solution or policy approach to a problem. Example:

Which type of claim is right for your argument? Which type of thesis or claim you use for your argument will depend on your position and knowledge of the topic, your audience, and the context of your paper. You might want to think about where you imagine your audience to be on this topic and pinpoint where you think the biggest difference in viewpoints might be. Even if you start with one type of claim you probably will be using several within the paper. Regardless of the type of claim you choose to utilize it is key to identify the controversy or debate you are addressing and to define your position early on in the paper.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.3.6: Qualify Your Claim, Argumentation and the Toulmin Method

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 74460

Argumentation and the Toulmin Method

Read this article to review the Toulmin method and qualifiers. Do you need to qualify your claim to avoid overgeneralization (assertions that are too broad)?

Argumentation

When teaching argumentation, it is important to show practical methods, as this is often an area that confuses students. By showing pragmatic approaches to structuring an argument, students can better articulate their thoughts. Moreover, the skill of argumentation can be applied to other assignments as well, such as the research paper, cause and effect, and compare and contrast.

The Toulmin Method

This is the statement the arguer wants the audience to believe. Claims such as "abortion should be protected by the constitution", "marijuana should be legal for medicinal purposes", and "the drinking age should be lowered", are examples of often over-used freshmen argument claims. The claim can serve as a thesis, and it is an essential starting point for any argument paper.

The grounds, or data, of an argument emphasizes the arguer's ethos (or credibility). It is imperative to an argument that the grounds be well founded, noncontroversial, and supportive. Claims supported with solid grounds become much stronger. For example, in an argument about lowering the drinking age, saying "my parents told me drinking is bad for you", is much less effective than saying, "scientists predict .5 percent of one's brain cells are lost every time he/she binge drinks".

This links the two previous steps. It creates the bridge between the claim and the grounds. Sometimes the warrant is implicit, unstated, or combined with the grounds.

4. Qualifier

This modifies the strength of an argument. Based on what kind of qualifier you choose, your argument becomes more or less believable. For example, the qualifier, "all people who drink become alcoholics", is so strong of a claim that it becomes unbelievable. Here, if the qualifier is toned-down, the statement becomes more believable: "Some people who drink become alcoholics".

5. Rebuttal

It is often important to include and possibly debunk rebuttal arguments. For example, saying "despite scientists claim about the effects of drinking on the brain, it has been shown to be no less damaging than using a cell phone", shows that you can anticipate your critics.

UC Davis Graduate Studies

Acing your qualifying examination, strategies for a successful qe.

The qualifying exam can be one of the most uncertain, stressful, and time consuming aspects of graduate education. The exam may include a written component in addition to the oral component and follows a format according to the specific requirements of the graduate program.

Although the content and structure of qualifying examinations varies by discipline, this information focuses on strategies for success valuable to graduate students in all departments. This is also a resource for graduate student advisors as they help graduate students prepare for this important milestone.

Understand the QE

Understanding the format and process of the QE is imperative to success. You should determine:

- How much time does the exam usually take?

- What is the format of the exam?

- How is your performance assessed?

Ask your major professor and QE Chair for input. Your graduate program coordinator can also provide advice on how the QE is typically scheduled and organized for your program.

Review the Doctoral Qualifying Examination webpage and the QE Regulations to learn how the QE is evaluated and what the results mean.

Know your examiners

The members of your QE committee will determine if you are ready to advance to candidacy. Learn about their background and research interests. Take a class with them if possible. Try to determine the following:

- What is your committee member’s academic training? Where and in what departments did they receive their degrees?

- What topics do your examiners write about? What are their publications? In what journals do they publish papers?

After you have thoroughly researched your committee members, and have verified they are suitable and applicable for your committee, you should meet with them. Try to meet with them in person at least once before the exam, as this will let you get to know their style of questions and their personality. When you meet with them ask the following questions:

- What is their philosophy towards the examination?

- Is there a particular topic area they expect to cover during the examination?

- What types of questions do they usually ask?

Talk to fellow graduate students about their QE experiences, especially those who have had the same committee members.

This information will help put you at ease with your examiners, and can help you anticipate possible questions they may ask. Think of the QE as an exchange of information with your senior colleagues rather than a test.

Prepare early and systematically

What to study varies according to your program and research field, but some strategies apply to all students. Organize the topics you will study from general to specific as this is often how your exam questions will progress, and it is the best way to re-learn material.

Ideally, you should begin your systematic studying six months in advance. However, do not stress if you only have a couple months. As long as you are systematic in your preparation, you will be in good shape.

- Review the basics of your field. You can achieve this by reviewing your past lower division courses. You can use old notes, textbooks, exams and lab write ups. Focus on the main themes and concepts. You may think that you have forgotten everything, but it will begin to come back to you.

- Review the specifics of your field. This means reviewing the material covered in any of your upper division or graduate level courses. Again, focus on the major themes and concepts. However, if there are details that relate to your research or your field of study, study those as well.

- Prepare and practice your dissertation research proposal. Often your dissertation proposal is formulated under guidance from your major professor. This includes a thorough literature review, research objectives and hypotheses, methodology, and expected results. The exam candidate is at an advantage here because at your QE, you will (or should be) the expert on your research topic. Therefore, any questions that your committee has about your research proposal you will be able to answer.

- A great strategy for practicing your dissertation research proposal is to explain your research to others. Begin with those in your department, because they will be able to give you scientifically based critiques. The greatest test of your ability to clearly explain your research is to present it to people outside of your field of study. This could include your friends in and outside of academia, and family members. The more you talk about your research and answer questions, the more prepared and confident you will be for your QE.

- Prepare your "how I came to be here" speech. Again, all programs are different and you should consult with your major professor and committee chair to see if this applies to you, but most QEs begin with a "how I came to be here" speech.

- Your committee may ask, “How did you come to be before us today?” or “Why did you decide to get your Ph.D?”, or “Why did you choose your topic of study?” There is no wrong answer to these questions. This gives you a chance to tell the committee about yourself, perhaps things they never knew before. You also should think of this speech as a platform for you to plant seeds for further questions from your committee members. Information you provide may prompt additional questions from them, so be sure to mention things you would be happy to discuss further.

- Prepare for anticipated questions. After you review the general and specific topics in your field, interview and meet with your committee members, and prepare your research proposal, you will have covered all of the potential topics in play for your QE. Now, you should begin to generate anticipated questions.

- Set up a practice qualifying exam. Enlist the help of your colleagues, fellow graduate students who have already passed their QE, or even friends or family. Present to them your "how I came to be here" speech and your research proposal. One of them should keep time for you, so you can adjust the length of your speech and proposal accordingly. Have them ask you several of your “anticipated questions” and questions they create. Ask them for critiques on your speech, volume and body language… anything you could work on before your oral exam. Try to conduct your mock exam in the same room you will hold your QE to become comfortable in the location.

- Review recent journals. As the date of your qualifying exam approaches, be sure to read the latest editions of the most important research journals in your field and subfield. Your committee members often read these same journals and they may draw some of their questions from recent articles.

Reduce your stress

If you have prepared systematically, you are in great shape and should be confident you are well prepared to succeed in your qualifying examination. If your stress levels are severe, seek additional resources .

- Schedule your exam at a time and location convenient for you. Talk to your committee several months in advance about scheduling a time, and they may be more flexible in accommodating your needs.

- How will you respond to off-the-wall questions? Expect you will receive a few unanticipated questions and create a response plan. Perhaps you can ask your committee member to repeat or clarify the question. Take a few moments to think about it. Restate the question out loud so you can make sure you understood the question as it was asked. Then go for it! You are prepared to answer.

- “I don't have that information at this time. However, I would obtain that information from…”

- “That is a good question and I am not sure about the answer. However, I would find the answer by…”

- “I am not sure what the answer is, but if I was to make a hypothesis based on my knowledge it would be….”

- Reconfirm the date, time, and location of the QE with all your committee members. This way you can touch base one last time before the big day.

- Visit the exam room and check that the keys fit, the lighting and any equipment are all functional and ready to go.

Have an exam day plan

The morning of your exam:

- Ensure you have reliable transportation to the exam location and account for unforeseen delays.

- Bring some water - you're going to do lots of talking. You are not expected to bring refreshments for the committee.

- Arrive at the exam room before your exam is scheduled to begin. Open the door, turn on the lights, and set up any audio visual equipment you may need.

During your exam:

- Know the time constraints of the exam. Use your watch and pace yourself accordingly. Speak slowly, and clearly. Do not cut off your examiners when they are speaking.

- At the end of the examination, be sure to thank all of your examiners politely for their time, consideration and effort.

After your exam:

- The committee will review and determine the result of your exam

- They will notify you of their decision – a unanimous, pass, not pass, or fail; or a split decision.

- If you passed – Congratulations, you’re ready to advance to candidacy! If you didn’t pass, the committee will provide feedback and a timeline/format for completing the second exam if applicable.

- Don't be discouraged if you don't pass the first time. Your committee may have identified an area or two on which you need to gain more knowledge. Don’t look at a "no pass" as a "vote of no confidence." It’s the responsibility of your committee to make sure that you’re ready to advance to candidacy.

For more information on the QE process and the meaning of the various results, consult the UC Davis Qualifying Exam Regulations .

The gathered information was part of a Professors for the Future student project and uses exam preparation material from Dr. Louis Grivetti, Department of Nutrition.

6 Effective Tips on How to Ace Your PhD Qualifying Exam

It’s probably not your first day at the university and you are still exploring the campus, determining which place would be your “nook”. Just as you do, you find a place to sit and it then feels surreal as you reminisce, “How did I get here?”—from determining your areas of interest for research to finding the university that offers a suitable program, from drafting personal statements to finally receiving the acceptance letter. And as you are looking into oblivion surrounded by these thoughts, you feel content and just as you breathe a sigh of relief, you hear muttering sounds from some students passing by. What do you hear? — “…something…something…Qualifying exam!”. And that’s when reality strikes you! Although you are in the program now, you must prove your candidacy for it by passing the PhD qualifying exam.

Table of Contents

What is a PhD Qualifying Exam?

In simpler words, a PhD qualifying exam is one of the requirements that determine whether or not the PhD student has successfully completed the first phase of the program and if they should be recommended for admission to candidacy for PhD. It is also referred to as the PhD candidacy exam and is probably one of the most arduous times for doctoral students. Furthermore, it is imperative for all doctoral students to prove their preparedness and capabilities to apply and synthesize the skills and knowledge during the graduate program by appearing for the qualifying exam. An integral part of the qualifying examination is a research proposal submitted to the examining committee at least two weeks before the examination.

What is the Purpose of a PhD Qualifying Exam?

A PhD student is someone who enrolls in a doctoral degree program. Typically, a PhD program requires students to complete a certain number of credits in coursework and successfully pass qualifying exams, which is followed by the dissertation writing and defense. The purpose of a PhD qualifying exam is to evaluate whether the student has adequate knowledge of the discipline and whether the student is eligible of conducting original research .

This qualifying exam is a bridge that transforms a PhD student into a PhD candidate. The difference between a PhD student and a PhD candidate is that the student is still working through the coursework and is yet to begin the dissertation process, and thus do not qualify to present and defend their dissertation to receive their doctorate. This period of transition means there is no more coursework to complete or classes to take; it is a self-defined structure of work from now with guidance from your supervisors at regular intervals.

What is the Format of the PhD Qualifying Exam?

Just as no two research projects can be alike, so cannot the qualifying exams for two different students. Thus, rather than asking your seniors about the questions that they were asked, a better approach is to understand the format and the process of the qualifying exam.

Typically, a PhD qualifying exam is conducted in two phases: a written exam and an oral exam.

1. Written Qualifying Exam

After completing your coursework, the written qualifying exam is the first one that you must take. The aim of this exam is to assess your ability to incorporate your learnings from all of the different classes you took in the program to formulate research questions and solve your research problems. Ideally, each of your committee members will test you separately on this.

2. Oral Qualifying Exam

The oral qualifying exam is undertaken after completion of the written part. Its purpose is to evaluate your thought process and ability to conduct the research required to complete a PhD . Additionally, some universities require you to present your research proposal and defend it during your oral qualifying exam.

During the oral exam, each professor from your committee will ask few questions related to your research proposal and your answers from the written exam. Sometimes, the committee members may also ask you to draw your answers on the board, especially if it’s an equation, a molecular structure, mechanism, or a diagram.

4 Possible Outcomes of the Qualifying Exam

“what if i fail my qualifying exam”- the petrifying thought.

Though this is the rarest situation that PhD students face, its possibility cannot be neglected. While the final result is based on what your committee members decide, they often give you a chance to retake the exam and meet certain conditions. However, if you fail the exam by unanimous decision of all committee members who oppose you from taking the reexam, you may have to leave the program and opt for another field of study or university.

But why should you be worried? You’ve got these nifty tips to crack your PhD qualifying exam!

Tips to Ace the PhD Qualifying Exam

Don’t you want to excel at your qualifying exam? Here are some things you should know!

1. Know Your Qualifying Exam Committee

- Identify the area of expertise of each committee member.

- Consult your seniors and other grad students who have worked with them and are currently working with them or have taken classes from them, or best—have had them for their own qualifying exam.

- Try to anticipate the pattern of their questions they are likely to follow and prepare your answers accordingly. However, do not spend too much time on this. It is likely, that your research proposal may give rise to a different line of questioning.

2. Know Your Subject

- Hit the library and stay updated with recent research in your field.

- Acquaint yourself with knowledge of your subject matter, as that’s what you’ll be tested on the most.

3. Know What is Expected of You

- Schedule a meeting with your committee members in advance, at least twice before appearing for your qualifying exam.

- Initiate a conversation about what you are expected to cover for the exam.

- Be an attentive listener and make note of their points as they speak.

- Ask them relevant questions so that you don’t get back to your room with doubts.

4. Know Your Plan

- Start with managing your time

- Organize your data and start writing the research proposal .

- Do not overcommit. Allot yourself 1–2 months of intense studying prior to the exam to master all the background and general knowledge you may need.

- Make your notes including textual as well as graphical content for quick revision.

- Request your supervisor or seniors to quiz you and critique your presentation. Work optimistically on their constructive suggestions.

5. Know the Challenges

- Presenting your proposal may at times be quite daunting. Hence, practice giving mock presentations during lab meetings or even in front of your mirror.

- Be prepared for technical as well as analytical questions.

6. Know the Do’s and Avoid the Don’ts

- While presenting, follow a narrative approach to keep the committee interested in your research.

- Explain your research briefly and add details as you are asked.

- Don’t overwhelm the examining committee with irrelevant details.

- Ensure that it’s a stimulating discussion among peers.

- Dress professionally and stay composed.

- More importantly, take a good night’s sleep before your exam day.

Final Thoughts

As my research advisor would say, “There’s only one step that keeps you away or brings you closer to your goal. It’s for you to choose the direction!” Similarly, the PhD qualifying exam is that one step you take to reach closer to the hallowed status of “Doctor”. So follow these nifty tips and share them with your friends and colleagues for we know what the future of research holds for us. Let us know the challenges you faced while preparing for your qualifying exam. How was it different from the experiences of your colleagues? You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to different aspects of research writing and publishing answered by our team that comprises subject-matter experts, eminent researchers, and publication experts.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

- AI in Academia

Disclosing the Use of Generative AI: Best practices for authors in manuscript preparation

The rapid proliferation of generative and other AI-based tools in research writing has ignited an…

Intersectionality in Academia: Dealing with diverse perspectives

Meritocracy and Diversity in Science: Increasing inclusivity in STEM education

Avoiding the AI Trap: Pitfalls of relying on ChatGPT for PhD applications

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

Published on September 7, 2022 by Tegan George and Shona McCombes. Revised on November 21, 2023.

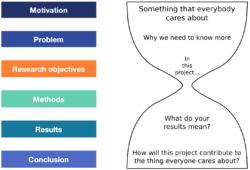

The introduction is the first section of your thesis or dissertation , appearing right after the table of contents . Your introduction draws your reader in, setting the stage for your research with a clear focus, purpose, and direction on a relevant topic .

Your introduction should include:

- Your topic, in context: what does your reader need to know to understand your thesis dissertation?

- Your focus and scope: what specific aspect of the topic will you address?

- The relevance of your research: how does your work fit into existing studies on your topic?

- Your questions and objectives: what does your research aim to find out, and how?

- An overview of your structure: what does each section contribute to the overall aim?

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to start your introduction, topic and context, focus and scope, relevance and importance, questions and objectives, overview of the structure, thesis introduction example, introduction checklist, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about introductions.

Although your introduction kicks off your dissertation, it doesn’t have to be the first thing you write — in fact, it’s often one of the very last parts to be completed (just before your abstract ).

It’s a good idea to write a rough draft of your introduction as you begin your research, to help guide you. If you wrote a research proposal , consider using this as a template, as it contains many of the same elements. However, be sure to revise your introduction throughout the writing process, making sure it matches the content of your ensuing sections.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Begin by introducing your dissertation topic and giving any necessary background information. It’s important to contextualize your research and generate interest. Aim to show why your topic is timely or important. You may want to mention a relevant news item, academic debate, or practical problem.

After a brief introduction to your general area of interest, narrow your focus and define the scope of your research.

You can narrow this down in many ways, such as by:

- Geographical area

- Time period

- Demographics or communities

- Themes or aspects of the topic

It’s essential to share your motivation for doing this research, as well as how it relates to existing work on your topic. Further, you should also mention what new insights you expect it will contribute.

Start by giving a brief overview of the current state of research. You should definitely cite the most relevant literature, but remember that you will conduct a more in-depth survey of relevant sources in the literature review section, so there’s no need to go too in-depth in the introduction.

Depending on your field, the importance of your research might focus on its practical application (e.g., in policy or management) or on advancing scholarly understanding of the topic (e.g., by developing theories or adding new empirical data). In many cases, it will do both.

Ultimately, your introduction should explain how your thesis or dissertation:

- Helps solve a practical or theoretical problem

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Builds on existing research

- Proposes a new understanding of your topic

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Perhaps the most important part of your introduction is your questions and objectives, as it sets up the expectations for the rest of your thesis or dissertation. How you formulate your research questions and research objectives will depend on your discipline, topic, and focus, but you should always clearly state the central aim of your research.

If your research aims to test hypotheses , you can formulate them here. Your introduction is also a good place for a conceptual framework that suggests relationships between variables .

- Conduct surveys to collect data on students’ levels of knowledge, understanding, and positive/negative perceptions of government policy.

- Determine whether attitudes to climate policy are associated with variables such as age, gender, region, and social class.

- Conduct interviews to gain qualitative insights into students’ perspectives and actions in relation to climate policy.

To help guide your reader, end your introduction with an outline of the structure of the thesis or dissertation to follow. Share a brief summary of each chapter, clearly showing how each contributes to your central aims. However, be careful to keep this overview concise: 1-2 sentences should be enough.

I. Introduction

Human language consists of a set of vowels and consonants which are combined to form words. During the speech production process, thoughts are converted into spoken utterances to convey a message. The appropriate words and their meanings are selected in the mental lexicon (Dell & Burger, 1997). This pre-verbal message is then grammatically coded, during which a syntactic representation of the utterance is built.

Speech, language, and voice disorders affect the vocal cords, nerves, muscles, and brain structures, which result in a distorted language reception or speech production (Sataloff & Hawkshaw, 2014). The symptoms vary from adding superfluous words and taking pauses to hoarseness of the voice, depending on the type of disorder (Dodd, 2005). However, distortions of the speech may also occur as a result of a disease that seems unrelated to speech, such as multiple sclerosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

This study aims to determine which acoustic parameters are suitable for the automatic detection of exacerbations in patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by investigating which aspects of speech differ between COPD patients and healthy speakers and which aspects differ between COPD patients in exacerbation and stable COPD patients.

Checklist: Introduction

I have introduced my research topic in an engaging way.

I have provided necessary context to help the reader understand my topic.

I have clearly specified the focus of my research.

I have shown the relevance and importance of the dissertation topic .

I have clearly stated the problem or question that my research addresses.

I have outlined the specific objectives of the research .

I have provided an overview of the dissertation’s structure .

You've written a strong introduction for your thesis or dissertation. Use the other checklists to continue improving your dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

Research objectives describe what you intend your research project to accomplish.

They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement .

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. & McCombes, S. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/introduction-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to write an abstract | steps & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- University of Baltimore Facebook Page

- University of Baltimore Twitter Page

- University of Baltimore LinkedIn Page

- University of Baltimore Instagram Page

- University of Baltimore YouTube Page

- Request Info

- Yale Gordon College of Arts and Sciences

Qualifying Exam and Dissertation Guidelines

Qualifying exam.

Download the Qualifying Exam and Dissertation Guidelines as a .pdf.

Rationale and Criteria

The Qualifying Examination determines whether a doctoral student is ready to begin the dissertation, the final phase of degree work. Students demonstrate their readiness through written and oral responses to questions they develop in consultation with an examining committee. Success is judged by three criteria:

- Intellectual fitness: Is the student prepared to undertake research and/or development at an advanced professional level?

- Conceptual framework: Is the student conversant with research, theory, and commentary in professional or scholarly areas related to the proposed project? Does the project’s design reflect an adequate grasp of knowledge in the field?

- Project design: Is the proposed doctoral project well conceived? Are the proposed methods appropriate? Is it practical? Will it make a demonstrable contribution to the student’s profession, community, or discipline?

The Qualifying Examination entails four tasks:

- Putting together an examining committee (which will also serve as dissertation committee)

- Proposing and refining examination questions

- Writing responses to the approved questions (Written Examination)

- Meeting with the examining committee to discuss the written responses (Oral Examination)

Students may take the Qualifying Examination after completing 24 credits of coursework. These courses should include all required core courses and must include the Proseminar. Students should schedule their examinations for the summer following Proseminar.

- Summer: Students must begin their exam in the first two weeks of June. Your questions must be approved by your committee by June 1, and a copy submitted to the program director. Your exam must be submitted to your committee eight calendar weeks later.

Students should allow at least 12 weeks for completing the four steps of the examination process. Oral examinations will typically be scheduled about two weeks after the written exam is turned in to the examining committee.

Students may not register for doctoral project credits until they have passed the qualifying exam.

Examining Committee

Examination questions.

At the beginning of the process the student should draft between 5-8 substantial questions relating to the proposed doctoral project and its social, professional and conceptual background.

Questions should be informed by the focus and larger social context of the intended dissertation, as well as by the student’s continuing reading and research, both in and out of courses. A question should be neither too broad (e.g., “What has been the impact of information technology on the publishing industry over the last 10 years?”) nor too narrowly concerned with details of the project (e.g., “Describe six aspects of the navigation system that will make [a particular website] a success”). Previous written examinations are on file with Professor Kathryn Summers; consult them for examples.

The student will send the initial draft questions to the examining committee for comment. This comment period will normally take 2-3 weeks, after which the examining committee will prepare a revised set of final questions. Questions may be altered, eliminated or consolidated by the examining committee.

At the end of the drafting process the student should have no fewer than three and no more than five working questions.

Written Examination

The student will prepare thorough responses to the approved questions. Answers take the form of substantial scholarly essays each between 2,500-4,000 words. The overall scope of the written examination will thus fall between 10,000-20,000 words.

In their written answers students should draw productively on reading and research they have done during coursework and project development. Source citations in the written examination should be given in American Psychological Association (APA) style. Students should include a list of works cited in APA style with the written examination.

Oral Examination

The oral part of the Qualifying Examination will be scheduled for two and a half hours, but will normally take between 90 minutes and two hours. Having read and reflected on the student’s written answers, the committee will engage the student in critical discussion of the document. The student is expected to show good grounding in relevant knowledge domains, acute understanding of the proposed project and its foundations and adequate intellectual preparation for carrying out the project.

Ordinarily students will be notified of results directly after the Oral Examination; however, the examination committee may deliberate for up to one week if necessary. Three results are possible: pass, fail or partial fail.

Students who pass should immediately prepare for adviser and committee a plan and timetable for completing remaining course requirements and the doctoral project. In some cases these plans may be discussed on the occasion of the Oral Examination.

If some aspects of a student’s performance in the Written or Oral Examinations are not satisfactory, the result will be a fail or partial fail. The examining committee will ask the student to submit revised answers to one or more of the written questions. Timetable for these revisions will be set by the committee, but the time limit is generally one month. If the resubmission is not found acceptable, then the student will receive a second mark of fail and may not continue in the doctoral program. However, the student may apply for the Graduate Certificate in User Experience (UX) Design.

Dissertation Guidelines

Dissertation timeline, the semester before you register for proseminar (idia 810).

Meet with your adviser or the professor assigned to teach Proseminar to informally discuss your thesis topic. Once you have informal approval, complete the Thesis Proposal Form. You will then be given permission to register for Proseminar.

The semester after Proseminar

You should take your qualifying exam. See D.S. Qualifying Exam for more information.

During semesters you are registered for dissertation hours

Weekly emails or short online meetings: you are required to meet weekly with your adviser documenting your dissertation progress. Your adviser may authorize weekly emails rather than online meetings.

Continuous Enrollment: You must register for a total of 12 D.S. project credits. You can register for a minimum of one credit per semester and for a maximum of six credits a semester. Once you have completed your 12 D.S. project credits, you are required to register for one credit of continuous enrollment IDIA 898 every fall or spring semester until graduation. You should continue to meet online weekly with your adviser.

During your final semester of dissertation

- Apply for graduation with the Office of the University Registrar at the beginning of the semester in which you plan to graduate.

- Turn in a complete draft of the dissertation to your adviser by Oct. 1 (or March 1 for spring).

- Submit a revised and approved version of your project to your full committee by Nov. 1 (or April 1 for spring). A decision will be made at this time whether or not to approve your participation in the graduation ceremony for the fall (your adviser must notify the program director).

- With the approval of your committee, schedule your project defense to occur before Dec. 1 (or May 1 for spring). The defense should not occur until the project is presumptively ready for approval.

- The final project must be signed by the committee and submitted to the library for binding within less than 60 days from the date of the graduation ceremony.

Literature Review for Dissertation

Purpose of a literature review A literature review forms an essential element of most thesis and dissertation work because it allows the author to complete two essential rhetorical tasks:

- to establish what is already known in a specialized field (and thus to bolster the credibility of the lit review’s author)

- to provide the basis for a new hypothesis or area to be researched.

Along the way, you should also accomplish the following:

- See what has and has not been investigated.

- Develop general explanations for observed variations in a behavior or phenomenon.

- Identify potential relationships between concepts and to identify researchable hypotheses.

- Learn how others have defined and measured key concepts.

- Identify data sources that other researchers have used.

- Discover how your research project is related to the work of others.

Pull your sources from Google, Google Scholar, the ACM Digital Library, the ASIS&T digital library, ERIC, DAAI and PsycINFO. Other databases may also be useful. Most of these databases are available through the Robert L. Bogomolny Library .

The ability to find, understand and evaluate best practices from industry and academic research is one of the abilities that can set you apart from other practitioners, so this is an important skill. The idea is to harness the best of what others have learned and done in support of your own project.

Structure of literature review Like all essays, a literature review should have an introduction and a conclusion. The material should be organized around subtopics that explore a field’s structure. In other words, avoid organizing the lit review as a string of summaries of each article. Instead, find overall themes that will help you and your reader understand the field of inquiry better. You are summarizing, synthesizing and providing critical analysis of the information you have collected.

Institutional Review Board Approval

With the literature review complete, you must request approval from the Institutional Review Board before conducting the user research piece of your dissertation. Your adviser must sign your request for approval. You can find the latest information on the UBalt Institutional Review Board website .

Dissertation Formatting and Submission

Schools and colleges.

- College of Public Affairs

- Merrick School of Business

- School of Law

- Robert L. Bogomolny Library

- Law Library

Quick Links

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Support

- Accreditation

- Basic Needs

- Building Hours

- Consumer Information

- Course Schedule

- Covid-19 Info

- Institutional Effectiveness

- Jobs at UBalt

- Mission and Strategic Plan

- MPX Quick Facts

- Policy Guide

- Privacy Statement

- Sexual Misconduct

- Shared Governance

- Social Media

- UBalt Campus Safety

HOW TO WRITE A THESIS: Steps by step guide

Introduction

In the academic world, one of the hallmark rites signifying mastery of a course or academic area is the writing of a thesis . Essentially a thesis is a typewritten work, usually 50 to 350 pages in length depending on institutions, discipline, and educational level which is often aimed at addressing a particular problem in a given field.

While a thesis is inadequate to address all the problems in a given field, it is succinct enough to address a specialized aspect of the problem by taking a stance or making a claim on what the resolution of the problem should be. Writing a thesis can be a very daunting task because most times it is the first complex research undertaking for the student. The lack of research and writing skills to write a thesis coupled with fear and a limited time frame are factors that makes the writing of a thesis daunting. However, commitment to excellence on the part of the student combined with some of the techniques and methods that will be discussed below gives a fair chance that the student will be able to deliver an excellent thesis regardless of the subject area, the depth of the research specialization and the daunting amount of materials that must be comprehended(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

Contact us now if you need help with writing your thesis. Check out our services

Visit our facebookpage

What is a thesis?

A thesis is a statement, theory, argument, proposal or proposition, which is put forward as a premise to be maintained or proved. It explains the stand someone takes on an issue and how the person intends to justify the stand. It is always better to pick a topic that will be able to render professional help, a topic that you will be happy to talk about with anybody, a topic you have personal interest and passion for, because when writing a thesis gets frustrating personal interest, happiness and passion coupled with the professional help it will be easier to write a great thesis (see you through the thesis). One has to source for a lot of information concerning the topic one is writing a thesis on in order to know the important question, because for you to take a good stand on an issue you have to study the evidence first.

Qualities of a good thesis

A good thesis has the following qualities

- A good thesis must solve an existing problem in the society, organisation, government among others.

- A good thesis should be contestable, it should propose a point that is arguable which people can agree with or disagree.

- It is specific, clear and focused.

- A good thesis does not use general terms and abstractions.

- The claims of a good thesis should be definable and arguable.

- It anticipates the counter-argument s

- It does not use unclear language

- It avoids the first person. (“In my opinion”)

- A strong thesis should be able to take a stand and not just taking a stand but should be able to justify the stand that is taken, so that the reader will be tempted to ask questions like how or why.

- The thesis should be arguable, contestable, focused, specific, and clear. Make your thesis clear, strong and easy to find.

- The conclusion of a thesis should be based on evidence.

Steps in writing a Thesis

- First, think about good topics and theories that you can write before writing the thesis, then pick a topic. The topic or thesis statement is derived from a review of existing literature in the area of study that the researcher wants to explore. This route is taken when the unknowns in an area of study are not yet defined. Some areas of study have existing problems yearning to be solved and the drafting of the thesis topic or statement revolves around a selection of one of these problems.

- Once you have a good thesis, put it down and draw an outline . The outline is like a map of the whole thesis and it covers more commonly the introduction, literature review, discussion of methodology, discussion of results and the thesis’ conclusions and recommendations. The outline might differ from one institution to another but the one described in the preceding sentence is what is more commonly obtainable. It is imperative at this point to note that the outline drew still requires other mini- outlines for each of the sections mentioned. The outlines and mini- outlines provide a graphical over- view of the whole project and can also be used in allocating the word- count for each section and sub- section based on the overall word- count requirement of the thesis(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

- Literature search. Remember to draw a good outline you need to do literature search to familiarize yourself with the concepts and the works of others. Similarly, to achieve this, you need to read as much material that contains necessary information as you can. There will always be a counter argument for everything so anticipate it because it will help shape your thesis. Read everything you can–academic research, trade literature, and information in the popular press and on the Internet(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

- After getting all the information you need, the knowledge you gathered should help in suggesting the aim of your thesis.

Remember; a thesis is not supposed to be a question or a list, thesis should specific and as clear as possible. The claims of a thesis should be definable and also arguable.

- Then collecting and analyzing data, after data analysis, the result of the analysis should be written and discussed, followed by summary, conclusion, recommendations, list of references and the appendices

- The last step is editing of the thesis and proper spell checking.

Structure of a Thesis

A conventional thesis has five chapters – chapter 1-5 which will be discussed in detail below. However, it is important to state that a thesis is not limited to any chapter or section as the case may be. In fact, a thesis can be five, six, seven or even eight chapters. What determines the number of chapters in a thesis includes institution rules/ guideline, researcher choice, supervisor choice, programme or educational level. In fact, most PhD thesis are usually more than 5 chapters(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

Preliminaries Pages: The preliminaries are the cover page, the title page, the table of contents page, and the abstract.

The introduction: The introduction is the first section and it provides as the name implies an introduction to the thesis. The introduction contains such aspects as the background to the study which provides information on the topic in the context of what is happening in the world as related to the topic. It also discusses the relevance of the topic to society, policies formulated success and failure. The introduction also contains the statement of the problem which is essentially a succinct description of the problem that the thesis want to solve and what the trend will be if the problem is not solved. The concluding part of the statement of problem ends with an outline of the research questions. These are the questions which when answered helps in achieving the aim of the thesis. The third section is the outline of research objectives. Conventionally research objectives re a conversion the research questions into an active statement form. Other parts of the introduction are a discussion of hypotheses (if any), the significance of the study, delimitations, proposed methodology and a discussion of the structure of the study(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The main body includes the following; the literature review, methodology, research results and discussion of the result, the summary, conclusion and recommendations, the list of references and the appendices.

The literature review : The literature review is often the most voluminous aspects of a thesis because it reviews past empirical and theoretical literature about the problem being studied. This section starts by discussing the concepts relevant to the problem as indicated in the topic, the relationship between the concepts and what discoveries have being made on topic based on the choice of methodologies. The validity of the studies reviewed are questioned and findings are compared in order to get a comprehensive picture of the problem. The literature review also discusses the theories and theoretical frameworks that are relevant to the problem, the gaps that are evident in literature and how the thesis being written helps in resolving some of the gaps.

The major importance of Literature review is that it specifies the gap in the existing knowledge (gap in literature). The source of the literature that is being reviewed should be specified. For instance; ‘It has been argued that if the rural youth are to be aware of their community development role they need to be educated’ Effiong, (1992). The author’s name can be at the beginning, end or in between the literature. The literature should be discussed and not just stated (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The methodology: The third section is a discussion of the research methodology adopted in the thesis and touches on aspects such as the research design, the area, population and sample that will be considered for the study as well as the sampling procedure. These aspects are discussed in terms of choice, method and rationale. This section also covers the sub- section of data collection, data analysis and measures of ensuring validity of study. It is the chapter 3. This chapter explains the method used in data collection and data analysis. It explains the methodology adopted and why it is the best method to be used, it also explains every step of data collection and analysis. The data used could be primary data or secondary data. While analysing the data, proper statistical tool should be used in order to fit the stated objectives of the thesis. The statistical tool could be; the spearman rank order correlation, chi square, analysis of variance (ANOVA) etc (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The findings and discussion of result : The next section is a discussion of findings based on the data collection instrumentation used and the objectives or hypotheses of study if any. It is the chapter 4. It is research results. This is the part that describes the research. It shows the result gotten from data that is collected and analysed. It discusses the result and how it relates to your profession.

Summary, Conclusion and Recommendation: This is normally the chapter 5. The last section discusses the summary of the study and the conclusions arrived at based on the findings discussed in the previous section. This section also presents any policy recommendations that the researcher wants to propose (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

References: It cite all ideas, concepts, text, data that are not your own. It is acceptable to put the initials of the individual authors behind their last names. The way single author is referenced is different from the way more than one author is referenced (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The appendices; it includes all data in the appendix. Reference data or materials that is not easily available. It includes tables and calculations, List of equipment used for an experiment or details of complicated procedures. If a large number of references are consulted but all are not cited, it may also be included in the appendix. The appendices also contain supportive or complementary information like the questionnaire, the interview schedule, tables and charts while the references section contain an ordered list of all literature, academic and contemporary cited in the thesis. Different schools have their own preferred referencing styles(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

Follow the following steps to achieve successful thesis writing

Start writing early. Do not delay writing until you have finished your project or research. Write complete and concise “Technical Reports” as and when you finish each nugget of work. This way, you will remember everything you did and document it accurately, when the work is still fresh in your mind. This is especially so if your work involves programming.

Spot errors early. A well-written “Technical Report” will force you to think about what you have done, before you move on to something else. If anything is amiss, you will detect it at once and can easily correct it, rather than have to re-visit the work later, when you may be pressured for time and have lost touch with it.

Write your thesis from the inside out. Begin with the chapters on your own experimental work. You will develop confidence in writing them because you know your own work better than anyone else. Once you have overcome the initial inertia, move on to the other chapters.

End with a bang, not a whimper. First things first, and save the best for last. First and last impressions persist. Arrange your chapters so that your first and last experimental chapters are sound and solid.

Write the Introduction after writing the Conclusions. The examiner will read the Introduction first, and then the Conclusions, to see if the promises made in the former are indeed fulfilled in the latter. Ensure that your introduction and Conclusions match.

“No man is an Island”. The critical review of the literature places your work in context. Usually, one third of the PhD thesis is about others’ work; two thirds, what you have done yourself. After a thorough and critical literature review, the PhD candidate must be able to identify the major researchers in the field and make a sound proposal for doctoral research. Estimate the time to write your thesis and then multiply it by three to get the correct estimate. Writing at one stretch is very demanding and it is all too easy to underestimate the time required for it; inflating your first estimate by a factor of three is more realistic.

Punctuating your thesis

Punctuation Good punctuation makes reading easy. The simplest way to find out where to punctuate is to read aloud what you have written. Each time you pause, you should add a punctuation symbol. There are four major pause symbols, arranged below in ascending order of “degree of pause”:

- Comma. Use the comma to indicate a short pause or to separate items in a list. A pair of commas may delimit the beginning and end of a subordinate clause or phrase. Sometimes, this is also done with a pair of “em dashes” which are printed like this:

- Semi-colon. The semi-colon signifies a longer pause than the comma. It separates segments of a sentence that are “further apart” in position, or meaning, but which are nevertheless related. If the ideas were “closer together”, a comma would have been used. It is also used to separate two clauses that may stand on their own but which are too closely related for a colon or full stop to intervene between them.

- Colon. The colon is used before one or more examples of a concept, and whenever items are to be listed in a visually separate fashion. The sentence that introduced the itemized list you are now reading ended in a colon. It may also be used to separate two fairly—but not totally—independent clauses in a sentence.

- Full stop or period. The full stop ends a sentence. If the sentence embodies a question or an exclamation, then, of course, it is ended with a question mark or exclamation mark, respectively. The full stop is also used to terminate abbreviations like etc., (for et cetera), e.g., (for exempli gratia), et al., (for et alia) etc., but not with abbreviations for SI units. The readability of your writing will improve greatly if you take the trouble to learn the basic rules of punctuation given above.

Don't forget to contact us for your thesis and other academic assistance

30 thoughts on “how to write a thesis: steps by step guide”.

wow.. thanks for sharing

Thanks for the article it’s very helpful

It’s very good

This is a great deal

Thank you much respect from here.

Thanks for the education.

thank you for the guide ,is very educating.

What can I say but THANK YOU. I will read your post many times in the future to clear my doubts.

Just came across this insightful article when about to start my PhD program. This is helpful thanks

Very informative website.

I’m really interested in your help. I’m doing my Master and this is my real challenge. I have given my thesis topic already.

chat with us on 09062671816

thanks so much and i will keep on reading till I get much more understanding.

thanks so much i will get in touch with you

Thanks for sharing…

Thanyou for sharing…

You can write my ms thesis

Pingback: My Site

There is perceptibly a bunch to realize about this. I assume you made some nice points in features also.

Loving the information on this web site, you have done great job on the blog posts.

Am happy to come across this web site, thanks a lot may God bless. In few months time I will be back.

anafranil prices

colchicine tablet brand name in india

can i buy colchicine without a prescription

synthroid over the counter online

Wow, marvelous blog format! How long have you been running a blog for? you make running a blog glance easy. The entire look of your site is wonderful, let alone the content!

thank you very much

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Qualitative Research 101: Interviewing

5 Common Mistakes To Avoid When Undertaking Interviews

By: David Phair (PhD) and Kerryn Warren (PhD) | March 2022

Undertaking interviews is potentially the most important step in the qualitative research process. If you don’t collect useful, useable data in your interviews, you’ll struggle through the rest of your dissertation or thesis. Having helped numerous students with their research over the years, we’ve noticed some common interviewing mistakes that first-time researchers make. In this post, we’ll discuss five costly interview-related mistakes and outline useful strategies to avoid making these.

Overview: 5 Interviewing Mistakes

- Not having a clear interview strategy /plan

- Not having good interview techniques /skills

- Not securing a suitable location and equipment

- Not having a basic risk management plan

- Not keeping your “ golden thread ” front of mind

1. Not having a clear interview strategy

The first common mistake that we’ll look at is that of starting the interviewing process without having first come up with a clear interview strategy or plan of action. While it’s natural to be keen to get started engaging with your interviewees, a lack of planning can result in a mess of data and inconsistency between interviews.

There are several design choices to decide on and plan for before you start interviewing anyone. Some of the most important questions you need to ask yourself before conducting interviews include:

- What are the guiding research aims and research questions of my study?

- Will I use a structured, semi-structured or unstructured interview approach?

- How will I record the interviews (audio or video)?

- Who will be interviewed and by whom ?

- What ethics and data law considerations do I need to adhere to?

- How will I analyze my data?

Let’s take a quick look at some of these.

The core objective of the interviewing process is to generate useful data that will help you address your overall research aims. Therefore, your interviews need to be conducted in a way that directly links to your research aims, objectives and research questions (i.e. your “golden thread”). This means that you need to carefully consider the questions you’ll ask to ensure that they align with and feed into your golden thread. If any question doesn’t align with this, you may want to consider scrapping it.

Another important design choice is whether you’ll use an unstructured, semi-structured or structured interview approach . For semi-structured interviews, you will have a list of questions that you plan to ask and these questions will be open-ended in nature. You’ll also allow the discussion to digress from the core question set if something interesting comes up. This means that the type of information generated might differ a fair amount between interviews.

Contrasted to this, a structured approach to interviews is more rigid, where a specific set of closed questions is developed and asked for each interviewee in exactly the same order. Closed questions have a limited set of answers, that are often single-word answers. Therefore, you need to think about what you’re trying to achieve with your research project (i.e. your research aims) and decided on which approach would be best suited in your case.

It is also important to plan ahead with regards to who will be interviewed and how. You need to think about how you will approach the possible interviewees to get their cooperation, who will conduct the interviews, when to conduct the interviews and how to record the interviews. For each of these decisions, it’s also essential to make sure that all ethical considerations and data protection laws are taken into account.

Finally, you should think through how you plan to analyze the data (i.e., your qualitative analysis method) generated by the interviews. Different types of analysis rely on different types of data, so you need to ensure you’re asking the right types of questions and correctly guiding your respondents.

Simply put, you need to have a plan of action regarding the specifics of your interview approach before you start collecting data. If not, you’ll end up drifting in your approach from interview to interview, which will result in inconsistent, unusable data.

2. Not having good interview technique

While you’re generally not expected to become you to be an expert interviewer for a dissertation or thesis, it is important to practice good interview technique and develop basic interviewing skills .

Let’s go through some basics that will help the process along.

Firstly, before the interview , make sure you know your interview questions well and have a clear idea of what you want from the interview. Naturally, the specificity of your questions will depend on whether you’re taking a structured, semi-structured or unstructured approach, but you still need a consistent starting point . Ideally, you should develop an interview guide beforehand (more on this later) that details your core question and links these to the research aims, objectives and research questions.

Before you undertake any interviews, it’s a good idea to do a few mock interviews with friends or family members. This will help you get comfortable with the interviewer role, prepare for potentially unexpected answers and give you a good idea of how long the interview will take to conduct. In the interviewing process, you’re likely to encounter two kinds of challenging interviewees ; the two-word respondent and the respondent who meanders and babbles. Therefore, you should prepare yourself for both and come up with a plan to respond to each in a way that will allow the interview to continue productively.

To begin the formal interview , provide the person you are interviewing with an overview of your research. This will help to calm their nerves (and yours) and contextualize the interaction. Ultimately, you want the interviewee to feel comfortable and be willing to be open and honest with you, so it’s useful to start in a more casual, relaxed fashion and allow them to ask any questions they may have. From there, you can ease them into the rest of the questions.

As the interview progresses , avoid asking leading questions (i.e., questions that assume something about the interviewee or their response). Make sure that you speak clearly and slowly , using plain language and being ready to paraphrase questions if the person you are interviewing misunderstands. Be particularly careful with interviewing English second language speakers to ensure that you’re both on the same page.

Engage with the interviewee by listening to them carefully and acknowledging that you are listening to them by smiling or nodding. Show them that you’re interested in what they’re saying and thank them for their openness as appropriate. This will also encourage your interviewee to respond openly.

Need a helping hand?

3. Not securing a suitable location and quality equipment

Where you conduct your interviews and the equipment you use to record them both play an important role in how the process unfolds. Therefore, you need to think carefully about each of these variables before you start interviewing.

Poor location: A bad location can result in the quality of your interviews being compromised, interrupted, or cancelled. If you are conducting physical interviews, you’ll need a location that is quiet, safe, and welcoming . It’s very important that your location of choice is not prone to interruptions (the workplace office is generally problematic, for example) and has suitable facilities (such as water, a bathroom, and snacks).

If you are conducting online interviews , you need to consider a few other factors. Importantly, you need to make sure that both you and your respondent have access to a good, stable internet connection and electricity. Always check before the time that both of you know how to use the relevant software and it’s accessible (sometimes meeting platforms are blocked by workplace policies or firewalls). It’s also good to have alternatives in place (such as WhatsApp, Zoom, or Teams) to cater for these types of issues.

Poor equipment: Using poor-quality recording equipment or using equipment incorrectly means that you will have trouble transcribing, coding, and analyzing your interviews. This can be a major issue , as some of your interview data may go completely to waste if not recorded well. So, make sure that you use good-quality recording equipment and that you know how to use it correctly.

To avoid issues, you should always conduct test recordings before every interview to ensure that you can use the relevant equipment properly. It’s also a good idea to spot check each recording afterwards, just to make sure it was recorded as planned. If your equipment uses batteries, be sure to always carry a spare set.

4. Not having a basic risk management plan

Many possible issues can arise during the interview process. Not planning for these issues can mean that you are left with compromised data that might not be useful to you. Therefore, it’s important to map out some sort of risk management plan ahead of time, considering the potential risks, how you’ll minimize their probability and how you’ll manage them if they materialize.

Common potential issues related to the actual interview include cancellations (people pulling out), delays (such as getting stuck in traffic), language and accent differences (especially in the case of poor internet connections), issues with internet connections and power supply. Other issues can also occur in the interview itself. For example, the interviewee could drift off-topic, or you might encounter an interviewee who does not say much at all.