Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 15 April 2021

A unified model of the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder

- Paola Magioncalda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4985-4819 1 , 2 , 3 na1 &

- Matteo Martino ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3783-707X 1 , 2 na1

Molecular Psychiatry volume 27 , pages 202–211 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5424 Accesses

27 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Bipolar disorder

- Neuroscience

This work provides an overview of the most consistent alterations in bipolar disorder (BD), attempting to unify them in an internally coherent working model of the pathophysiology of BD. Data on immune-inflammatory changes, structural brain abnormalities (in gray and white matter), and functional brain alterations (from neurotransmitter signaling to intrinsic brain activity) in BD were reviewed. Based on the reported data, (1) we hypothesized that the core pathological alteration in BD is a damage of the limbic network that results in alterations of neurotransmitter signaling. Although heterogeneous conditions can lead to such damage, we supposed that the main pathophysiological mechanism is traceable to an immune/inflammatory-mediated alteration of white matter involving the limbic network connections, which destabilizes the neurotransmitter signaling, such as dopamine and serotonin signaling. Then, (2) we suggested that changes in such neurotransmitter signaling (potentially triggered by heterogeneous stressors onto a structurally-damaged limbic network) lead to phasic (and often recurrent) reconfigurations of intrinsic brain activity, from abnormal subcortical–cortical coupling to changes in network activity. We suggested that the resulting dysbalance between networks, such as sensorimotor networks, salience network, and default-mode network, clinically manifest in combined alterations of psychomotricity, affectivity, and thought during the manic and depressive phases of BD. Finally, (3) we supposed that an additional contribution of gray matter alterations and related cognitive deterioration characterize a clinical–biological subgroup of BD. This model may provide a general framework for integrating the current data on BD and suggests novel specific hypotheses, prompting for a better understanding of the pathophysiology of BD.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

Joanna Moncrieff, Ruth E. Cooper, … Mark A. Horowitz

Emotions and brain function are altered up to one month after a single high dose of psilocybin

Frederick S. Barrett, Manoj K. Doss, … Roland R. Griffiths

A systems identification approach using Bayes factors to deconstruct the brain bases of emotion regulation

Ke Bo, Thomas E. Kraynak, … Tor D. Wager

A.P.A. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. 5th ed. (DSM-5). Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Kraepelin E. Clinical psychiatry. London: Macmillan; 1902.

Savitz JB, Rauch SL, Drevets WC. Clinical application of brain imaging for the diagnosis of mood disorders: the current state of play. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:528–39.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Savitz J, Drevets WC. Bipolar and major depressive disorder: neuroimaging the developmental-degenerative divide. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:699–771.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mechawar N, Savitz J. Neuropathology of mood disorders: do we see the stigmata of inflammation? Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e946.

Nikolaus S, Antke C, Muller HW. In vivo imaging of synaptic function in the central nervous system: II. Mental and affective disorders. Behav Brain Res. 2009;204:32–66.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:483–506.

Northoff G, Hirjak D, Wolf RC, Magioncalda P, Martino M. All roads lead to the motor cortex: psychomotor mechanisms and their biochemical modulation in psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:92–102.

Martino M, Magioncalda P. Tracing the psychopathology of bipolar disorder to the functional architecture of intrinsic brain activity and its neurotransmitter modulation: a three-dimensional model. Mol Psychiatry. 2021; [Online ahead of print].

Irwin M, Smith TL, Gillin JC. Low natural killer cytotoxicity in major depression. Life Sci. 1987;41:2127–33.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Maes M, Bosmans E, Suy E, Minner B, Raus J. Impaired lymphocyte stimulation by mitogens in severely depressed patients. A complex interface with HPA-axis hyperfunction, noradrenergic activity and the ageing process. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:793–8.

Anderson G, Maes M. Bipolar disorder: role of immune-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative and nitrosative stress and tryptophan catabolites. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:8.

Reus GZ, Fries GR, Stertz L, Badawy M, Passos IC, Barichello T, et al. The role of inflammation and microglial activation in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Neuroscience. 2015;300:141–54.

Kupka RW, Hillegers MH, Nolen WA, Breunis N, Drexhage HA. Immunological aspects of bipolar disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2000;12:86–90.

Barbosa IG, Machado-Vieira R, Soares JC, Teixeira AL. The immunology of bipolar disorder. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014;21:117–22.

Sayana P, Colpo GD, Simoes LR, Giridharan VV, Teixeira AL, Quevedo J, et al. A systematic review of evidence for the role of inflammatory biomarkers in bipolar patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;92:160–82.

Article Google Scholar

Fernandes BS, Steiner J, Molendijk ML, Dodd S, Nardin P, Goncalves CA, et al. C-reactive protein concentrations across the mood spectrum in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:1147–56.

Tsai SY, Chung KH, Chen PH. Levels of interleukin-6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein reflecting mania severity in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:708–9.

Barbosa IG, Rocha NP, Assis F, Vieira EL, Soares JC, Bauer ME, et al. Monocyte and lymphocyte activation in bipolar disorder: a new piece in the puzzle of immune dysfunction in mood disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18:pyu021.

Breunis MN, Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Suppes T, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, et al. High numbers of circulating activated T cells and raised levels of serum IL-2 receptor in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:157–65.

Tsai SY, Chen KP, Yang YY, Chen CC, Lee JC, Singh VK, et al. Activation of indices of cell-mediated immunity in bipolar mania. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:989–94.

do Prado CH, Rizzo LB, Wieck A, Lopes RP, Teixeira AL, Grassi-Oliveira R, et al. Reduced regulatory T cells are associated with higher levels of Th1/TH17 cytokines and activated MAPK in type 1 bipolar disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:667–76.

Brambilla P, Bellani M, Isola M, Bergami A, Marinelli V, Dusi N, et al. Increased M1/decreased M2 signature and signs of Th1/Th2 shift in chronic patients with bipolar disorder, but not in those with schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e406.

Kohler O, Sylvia LG, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Thase M, Shelton RC, et al. White blood cell count correlates with mood symptom severity and specific mood symptoms in bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51:355–65.

Wu W, Zheng YL, Tian LP, Lai JB, Hu CC, Zhang P, et al. Circulating T lymphocyte subsets, cytokines, and immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with bipolar II or major depression: a preliminary study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40530.

Magioncalda P, Martino M, Tardito S, Sterlini B, Conio B, Marozzi V, et al. White matter microstructure alterations correlate with terminally differentiated CD8+ effector T cell depletion in the peripheral blood in mania: Combined DTI and immunological investigation in the different phases of bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;73:192–204.

Kempton MJ, Geddes JR, Ettinger U, Williams SC, Grasby PM. Meta-analysis, database, and meta-regression of 98 structural imaging studies in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1017–32.

Birur B, Kraguljac NV, Shelton RC, Lahti AC. Brain structure, function, and neurochemistry in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder-a systematic review of the magnetic resonance neuroimaging literature. NPJ Schizophr. 2017;3:15.

Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Gray matter, white matter, brain, and intracranial volumes in first-episode bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:807–14.

Bora E, Fornito A, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Voxelwise meta-analysis of gray matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:1097–105.

Lim CS, Baldessarini RJ, Vieta E, Yucel M, Bora E, Sim K. Longitudinal neuroimaging and neuropsychological changes in bipolar disorder patients: review of the evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:418–35.

Hibar DP, Westlye LT, Doan NT, Jahanshad N, Cheung JW, Ching CRK, et al. Cortical abnormalities in bipolar disorder: an MRI analysis of 6503 individuals from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:932–42.

Mahon K, Burdick KE, Szeszko PR. A role for white matter abnormalities in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:533–54.

Sexton CE, Mackay CE, Ebmeier KP. A systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:814–23.

Vederine FE, Wessa M, Leboyer M, Houenou J. A meta-analysis of whole-brain diffusion tensor imaging studies in bipolar disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1820–6.

Nortje G, Stein DJ, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D, Horn N. Systematic review and voxel-based meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:192–200.

Wise T, Radua J, Nortje G, Cleare AJ, Young AH, Arnone D. Voxel-based meta-analytical evidence of structural disconnectivity in major depression and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:293–302.

Heng S, Song AW, Sim K. White matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder: insights from diffusion tensor imaging studies. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:639–54.

Favre P, Pauling M, Stout J, Hozer F, Sarrazin S, Abe C, et al. Widespread white matter microstructural abnormalities in bipolar disorder: evidence from mega- and meta-analyses across 3033 individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:2285–93.

Magioncalda P, Martino M, Conio B, Piaggio N, Teodorescu R, Escelsior A, et al. Patterns of microstructural white matter abnormalities and their impact on cognitive dysfunction in the various phases of type I bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:39–50.

Martino M, Magioncalda P, Saiote C, Conio B, Escelsior A, Rocchi G, et al. Abnormal functional-structural cingulum connectivity in mania: combined functional magnetic resonance imaging-diffusion tensor imaging investigation in different phases of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134:339–49.

Savitz JB, Price JL, Drevets WC. Neuropathological and neuromorphometric abnormalities in bipolar disorder: view from the medial prefrontal cortical network. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;42:132–47.

Bellani M, Boschello F, Delvecchio G, Dusi N, Altamura CA, Ruggeri M, et al. DTI and myelin plasticity in bipolar disorder: integrating neuroimaging and neuropathological findings. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:21.

Benedetti F, Poletti S, Hoogenboezem TA, Mazza E, Ambree O, de Wit H, et al. Inflammatory cytokines influence measures of white matter integrity in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:1–9.

Savitz J. Musings on mania: A role for T-lymphocytes? Brain Behav Immun. 2018;73:151–2.

Pape K, Tamouza R, Leboyer M, Zipp F. Immunoneuropsychiatry—novel perspectives on brain disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:317–28.

Schiffer RB, Wineman NM, Weitkamp LR. Association between bipolar affective disorder and multiple sclerosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:94–5.

Perugi G, Quaranta G, Belletti S, Casalini F, Mosti N, Toni C, et al. General medical conditions in 347 bipolar disorder patients: clinical correlates of metabolic and autoimmune-allergic diseases. J Affect Disord. 2015;170:95–103.

Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and immune dysfunction: epidemiological findings, proposed pathophysiology and clinical implications. Brain Sci. 2017;7:144.

Turner AP, Alschuler KN, Hughes AJ, Beier M, Haselkorn JK, Sloan AP, et al. Mental health comorbidity in MS: depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:106.

Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, Stuve O, Trojano M, Sorensen PS, et al. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015;21:305–17.

Pender MP. CD8+ T-cell deficiency, epstein-barr virus infection, vitamin d deficiency, and steps to autoimmunity: a unifying hypothesis. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:189096.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Melzer N, Meuth SG, Wiendl H. CD8+ T cells and neuronal damage: direct and collateral mechanisms of cytotoxicity and impaired electrical excitability. FASEB J. 2009;23:3659–73.

Baecher-Allan C, Kaskow BJ, Weiner HL. Multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and immunotherapy. Neuron. 2018;97:742–68.

Roosendaal SD, Geurts JJ, Vrenken H, Hulst HE, Cover KS, Castelijns JA, et al. Regional DTI differences in multiple sclerosis patients. Neuroimage. 2009;44:1397–403.

Willing A, Friese MA. CD8-mediated inflammatory central nervous system disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:316–21.

Piaggio N, Schiavi S, Martino M, Bommarito G, Inglese M, Magioncalda P. Exploring mania-associated white matter injury by comparison with multiple sclerosis: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2018;281:78–84.

Martino M, Magioncalda P, El Mendili MM, Droby A, Paduri S, Schiavi S, et al. Depression is associated with disconnection of neurotransmitter-related nuclei in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2020; [Online ahead of print].

Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Katz LC, LaMantia AS, McNamara JO. The limbic system, in Neuroscience, 2nd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2001.

Yeo BT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–65.

Drevets WC, Savitz J, Trimble M. The subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorders. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:663–81.

Ongur D, Ferry AT, Price JL. Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:425–49.

Drevets WC, Ongur D, Price JL. Neuroimaging abnormalities in the subgenual prefrontal cortex: implications for the pathophysiology of familial mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:220–6.

Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:471–81.

Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR Jr., Todd RD, Reich T, Vannier M, et al. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. 1997;386:824–7.

Ongur D, Drevets WC, Price JL. Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13290–5.

Leow A, Ajilore O, Zhan L, Arienzo D, GadElkarim J, Zhang A, et al. Impaired inter-hemispheric integration in bipolar disorder revealed with brain network analyses. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:183–93.

O’Donoghue S, Holleran L, Cannon DM, McDonald C. Anatomical dysconnectivity in bipolar disorder compared with schizophrenia: a selective review of structural network analyses using diffusion MRI. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:217–28.

Belvederi Murri M, Prestia D, Mondelli V, Pariante C, Patti S, Olivieri B, et al. The HPA axis in bipolar disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:327–42.

Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45:651–60.

Pani L, Porcella A, Gessa GL. The role of stress in the pathophysiology of the dopaminergic system. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:14–21.

Lanfumey L, Mongeau R, Cohen-Salmon C, Hamon M. Corticosteroid-serotonin interactions in the neurobiological mechanisms of stress-related disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1174–84.

Bali A, Randhawa PK, Jaggi AS. Stress and opioids: role of opioids in modulating stress-related behavior and effect of stress on morphine conditioned place preference. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;51:138–50.

Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:243–51.

Elenkov IJ. Neurohormonal-cytokine interactions: implications for inflammation, common human diseases and well-being. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:40–51.

Zheng H, Ford BN, Bergamino M, Kuplicki R, Hunt PW, Bodurka J, et al. A hidden menace? Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with reduced cortical gray matter volume in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2020; [Online ahead of print].

Savitz J. The kynurenine pathway: a finger in every pie. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:131–47.

Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:22–34.

Myint AM, Kim YK. Network beyond IDO in psychiatric disorders: revisiting neurodegeneration hypothesis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;48:304–13.

Carlsson A, Waters N, Holm-Waters S, Tedroff J, Nilsson M, Carlsson ML. Interactions between monoamines, glutamate, and GABA in schizophrenia: new evidence. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:237–60.

Felger JC, Li Z, Haroon E, Woolwine BJ, Jung MY, Hu X, et al. Inflammation is associated with decreased functional connectivity within corticostriatal reward circuitry in depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1358–65.

Salomon RM, Cowan RL. Oscillatory serotonin function in depression. Synapse. 2013;67:801–20.

Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Lowe MJ, Dzemidzic M. Resting state corticolimbic connectivity abnormalities in unmedicated bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009;171:189–98.

Anticevic A, Cole MW, Repovs G, Murray JD, Brumbaugh MS, Winkler AM, et al. Characterizing thalamo-cortical disturbances in schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:3116–30.

Skatun KC, Kaufmann T, Brandt CL, Doan NT, Alnaes D, Tonnesen S, et al. Thalamo-cortical functional connectivity in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12:640–52.

Tu PC, Bai YM, Li CT, Chen MH, Lin WC, Chang WC, et al. Identification of common thalamocortical dysconnectivity in four major psychiatric disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:1143–51.

Martino M, Magioncalda P, Conio B, Capobianco L, Russo D, Adavastro G, et al. Abnormal functional relationship of sensorimotor network with neurotransmitter-related nuclei via subcortical-cortical loops in manic and depressive phases of bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:163–74.

Ongur D, Lundy M, Greenhouse I, Shinn AK, Menon V, Cohen BM, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;183:59–68.

Khadka S, Meda SA, Stevens MC, Glahn DC, Calhoun VD, Sweeney JA, et al. Is aberrant functional connectivity a psychosis endophenotype? A resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:458–66.

Magioncalda P, Martino M, Conio B, Escelsior A, Piaggio N, Presta A, et al. Functional connectivity and neuronal variability of resting state activity in bipolar disorder−reduction and decoupling in anterior cortical midline structures. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:666–82.

Doucet GE, Bassett DS, Yao N, Glahn DC, Frangou S. The role of intrinsic brain functional connectivity in vulnerability and resilience to bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1214–22.

Baker JT, Dillon DG, Patrick LM, Roffman JL, Brady RO Jr., Pizzagalli DA, et al. Functional connectomics of affective and psychotic pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:9050–9.

Vargas C, Lopez-Jaramillo C, Vieta E. A systematic literature review of resting state network-functional MRI in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:727–35.

Shiah IS, Yatham LN. Serotonin in mania and in the mechanism of action of mood stabilizers: a review of clinical studies. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:77–92.

Mosienko V, Beis D, Pasqualetti M, Waider J, Matthes S, Qadri F, et al. Life without brain serotonin: reevaluation of serotonin function with mice deficient in brain serotonin synthesis. Behav Brain Res. 2015;277:78–88.

Dalley JW, Roiser JP. Dopamine, serotonin and impulsivity. Neuroscience. 2012;215:42–58.

Winter C, von Rumohr A, Mundt A, Petrus D, Klein J, Lee T, et al. Lesions of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and in the ventral tegmental area enhance depressive-like behavior in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2007;184:133–41.

van Enkhuizen J, Geyer MA, Minassian A, Perry W, Henry BL, Young JW. Investigating the underlying mechanisms of aberrant behaviors in bipolar disorder from patients to models: rodent and human studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;58:4–18.

Cosgrove VE, Kelsoe JR, Suppes T. Toward a valid animal model of bipolar disorder: how the research domain criteria help bridge the clinical-basic science divide. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:62–70.

Altinay MI, Hulvershorn LA, Karne H, Beall EB, Anand A. Differential resting-state functional connectivity of striatal subregions in bipolar depression and hypomania. Brain Connect. 2016;6:255–65.

Brady RO Jr., Masters GA, Mathew IT, Margolis A, Cohen BM, Ongur D, et al. State dependent cortico-amygdala circuit dysfunction in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:79–87.

Brady RO Jr., Margolis A, Masters GA, Keshavan M, Ongur D. Bipolar mood state reflected in cortico-amygdala resting state connectivity: A cohort and longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:205–9.

Martino M, Magioncalda P, Huang Z, Conio B, Piaggio N, Duncan NW, et al. Contrasting variability patterns in the default mode and sensorimotor networks balance in bipolar depression and mania. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4824–9.

Zuo XN, Di Martino A, Kelly C, Shehzad ZE, Gee DG, Klein DF, et al. The oscillating brain: complex and reliable. NeuroImage. 2010;49:1432–45.

Zhang J, Magioncalda P, Huang Z, Tan Z, Hu X, Hu Z, et al. Altered global signal topography and its different regional localization in motor cortex and hippocampus in mania and depression. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:902–10.

Russo D, Martino M, Magioncalda P, Inglese M, Amore M, Northoff G. Opposing changes in the functional architecture of large-scale networks in bipolar mania and depression. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:971–80.

Brady RO Jr., Tandon N, Masters GA, Margolis A, Cohen BM, Keshavan M, et al. Differential brain network activity across mood states in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:367–76.

Lee I, Nielsen K, Nawaz U, Hall MH, Ongur D, Keshavan M, et al. Diverse pathophysiological processes converge on network disruption in mania. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:115–23.

Spielberg JM, Beall EB, Hulvershorn LA, Altinay M, Karne H, Anand A. Resting state brain network disturbances related to hypomania and depression in medication-free bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:3016–24.

Liu CH, Li F, Li SF, Wang YJ, Tie CL, Wu HY, et al. Abnormal baseline brain activity in bipolar depression: a resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203:175–9.

Liu CH, Ma X, Li F, Wang YJ, Tie CL, Li SF, et al. Regional homogeneity within the default mode network in bipolar depression: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e48181.

Wang Y, Wang J, Jia Y, Zhong S, Zhong M, Sun Y, et al. Topologically convergent and divergent functional connectivity patterns in unmedicated unipolar depression and bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1165.

Syan SK, Smith M, Frey BN, Remtulla R, Kapczinski F, Hall GBC, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity in individuals with bipolar disorder during clinical remission: a systematic review. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2018;43:298–316.

Conio B, Martino M, Magioncalda P, Escelsior A, Inglese M, Amore M, et al. Opposite effects of dopamine and serotonin on resting-state networks: review and implications for psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:82–93.

Floreani A, Leung PS, Gershwin ME. Environmental basis of autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:287–300.

Rocchi G, Sterlini B, Tardito S, Inglese M, Corradi A, Filaci G, et al. Opioidergic system and functional architecture of intrinsic brain activity: implications for psychiatric disorders. Neuroscientist. 2020;26:343–58.

Horrobin DF, Lieb J. A biochemical basis for the actions of lithium on behaviour and on immunity: relapsing and remitting disorders of inflammation and immunity such as multiple sclerosis or recurrent herpes as manic-depression of the immune system. Med Hypotheses. 1981;7:891–905.

Zuo XN, Xu T, Milham MP. Harnessing reliability for neuroscience research. Nat Hum Behav. 2019;3:768–71.

Gong ZQ, Gao P, Jiang C, Xing XX, Dong HM, White T, et al. DREAM: a toolbox to decode rhythms of the brain system. Neuroinformatics. 2021; [Online ahead of print].

Dong HM, Castellanos FX, Yang N, Zhang Z, Zhou Q, He Y, et al. Charting brain growth in tandem with brain templates at school age. Sci Bull. 2020;65:1924–34.

Download references

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Paola Magioncalda, Matteo Martino

Authors and Affiliations

Graduate Institute of Mind Brain and Consciousness, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

Paola Magioncalda & Matteo Martino

Brain and Consciousness Research Center, Taipei Medical University - Shuang Ho Hospital, New Taipei City, Taiwan

Department of Psychiatry, Taipei Medical University - Shuang Ho Hospital, New Taipei City, Taiwan

- Paola Magioncalda

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Paola Magioncalda or Matteo Martino .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary_material, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Magioncalda, P., Martino, M. A unified model of the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 27 , 202–211 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01091-4

Download citation

Received : 07 December 2020

Revised : 17 March 2021

Accepted : 29 March 2021

Published : 15 April 2021

Issue Date : January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01091-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Motor performance and functional connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and supplementary motor cortex in bipolar and unipolar depression.

- Lara E. Marten

- Aditya Singh

- Roberto Goya-Maldonado

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2024)

Prefrontal, parietal, and limbic condition-dependent differences in bipolar disorder: a large-scale meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies

- Maya C. Schumer

- Henry W. Chase

- Mary L. Phillips

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

Circulating cytotoxic immune cell composition, activation status and toxins expression associate with white matter microstructure in bipolar disorder

- Veronica Aggio

- Lorena Fabbella

- Francesco Benedetti

Scientific Reports (2023)

A three-dimensional model of neural activity and phenomenal-behavioral patterns

- Matteo Martino

Mania-related effects on structural brain changes in bipolar disorder – a narrative review of the evidence

- Christoph Abé

- Benny Liberg

- Mikael Landén

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- Spring 2024 | VOL. 22, NO. 2 Autism Across the Lifespan CURRENT ISSUE pp.147-262

- Winter 2024 | VOL. 22, NO. 1 Reproductive Psychiatry: Postpartum Depression is Only the Tip of the Iceberg pp.1-142

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Abstracts for B ipolar D isorder

Given space limitations and varying reprint permission policies, not all of the influential publications the editors considered reprinting in this issue could be included. This section contains abstracts from additional articles the editors deemed well worth reviewing.

Clinical Course of Children and Adolescents with Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Ivengar S, Keller M

Archives of General Psychiatry February 2006 ; 63(2):175–183

Context: Despite the high morbidity associated with bipolar disorder (BP), few studies have prospectively studied the course of this illness in youth. Objective: To assess the longitudinal course of BP spectrum disorders (BP-I, BP-II, and not otherwise specified [BP-NOS]) in children and adolescents. Design: Subjects were interviewed, on average, every 9 months for an average of 2 years using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. Setting: Outpatient and inpatient units at 3 university centers. Participants: Two hundred sixty-three children and adolescents (mean age, 13 years) with BP-I (n = 152), BP-II (n = 19), and BP-NOS (n = 92). Main Outcome Measures: Rates of recovery and recurrence, weeks with syndromal or subsyndromal mood symptoms, changes in symptoms and polarity, and predictors of outcome. Results: Approximately 70% of subjects with BP recovered from their index episode, and 50% had at least 1 syndromal recurrence, particularly depressive episodes. Analyses of weekly mood symptoms showed that 60% of the follow-up time, subjects had syndromal or subsyndromal symptoms with numerous changes in symptoms and shifts of polarity, and 3% of the time, psychosis. Twenty percent of BP-II subjects converted to BP-I, and 25% of BP-NOS subjects converted to BP-I or BP-II. Early-onset BP, BP-NOS, long duration of mood symptoms, low socioeconomic status, and psychosis were associated with poorer outcomes and rapid mood changes. Secondary analyses comparing BP-I youths with BP-I adults showed that youths significantly more time symptomatic and had more mixed/cycling episodes, mood symptom changes, and polarity switches. Conclusions: Youths with BP spectrum disorders showed a continuum of BP symptom severity from subsyndromal to full syndromal with frequent mood fluctuations. Results of this study provide preliminary validation for BP-NOS.

Genetic Variation of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in Bipolar Disorder: Case-control Study of Over 3000 Individuals From the UK

Green EK, Raybould R, Macqregor S, Hyde S, Young AH, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Kirov G, Jones L, Jones I, Craddock N

The British Journal of Psychiatry January 2006 ; 188:21–25

Background: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) influences neuronal survival, proliferation and plasticity. Three family-based studies have shown association of the common Valine (Val) allele of the Val66Met polymorphism of the BDNF gene with susceptibility to bipolar disorder. Aims: To replicate this finding. Method: We genotyped the Val66Met polymorphism in our UK White bipolar case-control sample (n = 3062). Results: We found no overall evidence of allele or genotype association. However, we found association with disease status in the subset of 131 individuals that had experienced rapid cycling at some time (P = 0.004). We found a similar association on re-analysis of our previously reported family-based association sample (P < 0.03, one-tailed test). Conclusions: Variation at the Val66Met polymorphism of BDNF does not play a major role in influencing susceptibility to bipolar disorder as a whole, but is associated with susceptibility to the rapid-cycling subset of the disorder.

Relationship of Mania Symptomatology to Maintenance Treatment Response with Divalproex, Lithium, or Placebo

Bowden CL, Collins MA, McElrov SL, Calabrese JR, Swann AC, Weisler RH, Wozniak PJ

Neuropsychopharmacology October 2005 ; 30(10):1932–1939

Euphoric and mixed (dysphoric) manic symptoms have different response patterns to divalproex and lithium in acute mania treatment, but have not been studied in relationship to maintenance treatment outcomes. We examined the impact of initial euphoric or dysphoric manic symptomatology on maintenance outcome. Randomized maintenance treatment with divalproex, lithium, or placebo was provided for 372 bipolar I patients, who met improvement criteria during open phase treatment for an index manic episode. The current analysis grouped patients according to the index manic episode subtype (euphoric or dysphoric), and evaluated the impact on maintenance treatment outcome. The rate of early discontinuation due to intolerance during maintenance treatment was higher for initially dysphoric patients (N = 249) than euphoric patients (N = 123; 15.7 vs 7.3%, respectively; p = 0.032). Both lithium (23.2%) and divalproex (17.1%) were associated with more premature discontinuations due to intolerance than placebo (4.8%; p = 0.003 and 0.02, respectively) in the initially dysphoric patients. Among initially euphoric patients, treatment with lithium was associated with significantly more premature discontinuations due to intolerance compared to placebo (18.2 vs 0%; p = 0.03), and divalproex was significantly (p = 0.05) more effective than lithium, but not placebo in delaying time to a depressive episode. Initial euphoric mania appeared to predispose to better outcomes on indices of depression and overall function with divalproex maintenance than with either placebo or lithium. Dysphoric mania appeared to predispose patients to more side effects when treated with either divalproex or lithium during maintenance therapy.

Dermatology Precautions and Slower Titration Yield Low Incidence of Lamotrigine Treatment-emergent Rash

Ketter TA, Wang PW, Chandler RA, Alarcon AM, Becker OV, Nowakowska C, O’Keeffe CM, Schumacher MR

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry May 2005 ; 66(5):642–645

Objective: To assess treatment-emergent rash incidence when using dermatology precautions (limited antigen exposure) and slower titration during lamotrigine initiation. Method: We assessed rash incidence in 100 patients with DSM-IV bipolar disorder instructed, for their first 3 months taking lamotrigine, to avoid other new medicines and new foods, cosmetics, conditioners, deodorants, detergents, and fabric softeners, as well as sunburn and exposure to poison ivy/oak. Lamotrigine was not started within 2 weeks of a rash, viral syndrome, or vaccination. In addition, lamotrigine was titrated more slowly than in the prescribing information. Patients were monitored for rash and clinical phenomena using the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder Clinical Monitoring Form. Descriptive statistics were compiled. Results: No patient had serious rash. Benign rash occurred in 5 patients (5%) and resolved uneventfully in 3 patients discontinuing and 2 patients continuing lamotrigine. Two patients with rash were found to be not adherent to dermatology precautions. Therefore, among the remaining patients, only 3/98 (3.1%) had benign rashes. Conclusion: The observed rate of benign rash was lower than the 10% incidence in other clinical studies. The design of this study confounds efforts to determine the relative contributions of slower titration versus dermatology precautions to the low rate of rash. Systematic studies are needed to confirm these preliminary findings, which suggest that adhering to dermatology precautions with slower titration may yield a low incidence of rash with lamotrigine.

Two-year Outcomes for Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy in Individuals with Bipolar I Disorder

Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, Fagiolini AM, Grochocinski V, Houck P, Scott J, Thompson W, Monk T

Archives of General Psychiatry September 2005 ; 62(9):996–1004

Context: Numerous studies have pointed to the failure of prophylaxis with pharmacotherapy alone in the treatment of bipolar I disorder. Recent investigations have demonstrated benefits from the addition of psychoeducation or psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in this population. Objective: To compare 2 psychosocial interventions: interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) and an intensive clinical management (ICM) approach in the treatment of bipolar I disorder. Design: Randomized controlled trial involving 4 treatment strategies: acute and maintenance IPSRT (IPSRT/IPSRT), acute and maintenance ICM (ICM/ICM), acute IPSRT followed by maintenance ICM (IPSRT/ICM), or acute ICM followed by maintenance IPSRT (ICM/IPSRT). The preventive maintenance phase lasted 2 years. Setting: Research clinic in a university medical center. Participants: One hundred seventy-five acutely ill individuals with bipolar I disorder recruited from inpatient and outpatient settings, clinical referral, public presentations about bipolar disorder, and other public information activities. Interventions: Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, an adaptation of Klerman and Weissman’s interpersonal psychotherapy to which a social rhythm regulation component has been added, and ICM. Main Outcome Measures: Time to stabilization in the acute phase and time to recurrence in the maintenance phase. Results: We observed no difference between the treatment strategies in time to stabilization. After controlling for covariates of survival time, we found that participants assigned to IPSRT in the acute treatment phase survived longer without a new affective episode (P = .01), irrespective of maintenance treatment assignment. Participants in the IPSRT group had higher regularity of social rhythms at the end of acute treatment (P<.001). Ability to increase regularity of social rhythms during acute treatment was associated with reduced likelihood of recurrence during the maintenance phase (P = .05). Conclusion: Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy appears to add to the clinical armamentarium for the management of bipolar I disorder, particularly with respect to prophylaxis of new episodes.

A Placebo-controlled 18-month Trial of Lamotrigine and Lithium Maintenance Treatment in Recently Manic or Hypomanic Patients with Bipolar I Disorder

Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Asghar SA, Hompland M, Montgomery P, Earl N, Smoot TM, DeVeaugh-Geiss J; Lamictal 606 Study Group

Archives of General Psychiatry April 2003 ; 60(4):392–400

Background: Lamotrigine has been shown to be an effective treatment for bipolar depression and rapid cycling in placebo-controlled clinical trials. This double-blind, placebo-controlled study was conducted to assess the efficacy and tolerability of lamotrigine and lithium compared with placebo for the prevention of relapse or recurrence of mood episodes in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Methods: After an 8- to 16-week open-label phase during which treatment with lamotrigine was initiated and other psychotropic drug regimens were discontinued, patients were randomized to lamotrigine (100–400 mg daily), lithium (0.8–1.1 mEq/L), or placebo as double-blind maintenance treatment for as long as 18 months. Results: Of 349 patients who met screening criteria and entered the open-label phase, 175 met stabilization criteria and were randomized to double-blind maintenance treatment (lamotrigine, 59 patients; lithium, 46 patients; and placebo, 70 patients). Both lamotrigine and lithium were superior to placebo at prolonging the time to intervention for any mood episode (lamotrigine vs placebo, P = .02; lithium vs placebo, P = .006). Lamotrigine was superior to placebo at prolonging the time to a depressive episode (P = .02). Lithium was superior to placebo at prolonging the time to a manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode (P = .006). The most common adverse event reported for lamotrigine was headache. Conclusions: Both lamotrigine and lithium were superior to placebo for the prevention of relapse or recurrence of mood episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder who had recently experienced a manic or hypomanic episode. The results indicate that lamotrigine is an effective, well-tolerated maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder, particularly for prophylaxis of depression.

A Randomized Trial on the Efficacy of Group Psychoeducation in the Prophylaxis of Recurrences in Bipolar Patients whose Disease is in Remission

Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Torrent C, Comes M, Corbella B, Parramon G, Corominas J

Archives of General Psychiatry April 2003 ; 60(4):402–407

Background: Studies on individual psychotherapy indicate that some interventions may reduce the number of recurrences in bipolar patients. However, there has been a lack of structured, well-designed, blinded, controlled studies demonstrating the efficacy of group psychoeducation to prevent recurrences in patients with bipolar I and II disorder. Methods: One hundred twenty bipolar I and II outpatients in remission (Young Mania Rating Scale score <6, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score <8) for at least 6 months prior to inclusion in the study, who were receiving standard pharmacologic treatment, were included in a controlled trial. Subjects were matched for age and sex and randomized to receive, in addition to standard psychiatric care, 21 sessions of group psychoeducation or 21 sessions of nonstructured group meetings. Subjects were assessed monthly during the 21-week treatment period and throughout the 2-year follow-up. Results: Group psychoeducation significantly reduced the number of relapsed patients and the number of recurrences per patient, and increased the time to depressive, manic, hypomanic, and mixed recurrences. The number and length of hospitalizations per patient were also lower in patients who received psychoeducation. Conclusion: Group psychoeducation is an efficacious intervention to prevent recurrence in pharmacologically treated patients with bipolar I and II disorder.

A Randomized Controlled Study of Cognitive Therapy for Relapse Prevention for Bipolar Affective Disorder: Outcome of the First Year

Lam DH, Watkins ER, Hayward P, Bright J, Wright K, Kerr N, Parr-Davis G, Sham P

Archives of General Psychiatry February 2003 ; 60(2):145–152

Background: Despite the use of mood stabilizers, a significant proportion of patients with bipolar affective disorder experience frequent relapses. A pilot study of cognitive therapy (CT) specifically designed to prevent relapses for bipolar affective disorder showed encouraging results when used in conjunction with mood stabilizers. This article reports the outcome of a randomized controlled study of CT to help prevent relapses and promote social functioning. Methods: We randomized 103 patients with bipolar 1 disorder according to the DSM-IV, who experienced frequent relapses despite the prescription of commonly used mood stabilizers, into a CT group or control group. Both the control and CT groups received mood stabilizers and regular psychiatric follow-up. In addition, the CT group received an average of 14 sessions of CT during the first 6 months and 2 booster sessions in the second 6 months. Results: During the 12-month period, the CT group had significantly fewer bipolar episodes, days in a bipolar episode, and number of admissions for this type of episode. The CT group also had significantly higher social functioning. During these 12 months, the CT group showed less mood symptoms on the monthly mood questionnaires. Furthermore, there was significantly less fluctuation in manic symptoms in the CT group. The CT group also coped better with manic prodromes at 12 months. Conclusion: Our findings support the conclusion that CT specifically designed for relapse prevention in bipolar affective disorder is a useful tool in conjunction with mood stabilizers.

The Long-term Natural History of the Weekly Symptomatic Status of Bipolar I Disorder

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB

Archives of General Psychiatry June 2002 ; 59(6):530–537

Background: To our knowledge, this is the first prospective natural history study of weekly symptomatic status of patients with bipolar I disorder (BP-I) during long-term follow-up. Methods: Analyses are based on ongoing prospective follow-up of 146 patients with Research Diagnostic Criteria BP-I, who entered the National Institute of Mental Health (Bethesda, Md) Collaborative Depression Study from 1978 through 1981. Weekly affective symptom status ratings were analyzed by polarity and severity, ranging from asymptomatic, to subthreshold levels, to full-blown major depression and mania. Percentages of follow-up weeks at each level as well as number of shifts in symptom status and polarity during the entire follow-up period were examined. Finally, 2 new measures of chronicity were evaluated in relation to previously identified predictors of chronicity for BP-I. Results: Patients with BP-I were symptomatically ill 47.3% of weeks throughout a mean of 12.8 years of follow-up. Depressive symptoms (31.9% of total follow-up weeks) predominated over manic/hypomanic symptoms (8.9% of weeks) or cycling/mixed symptoms (5.9% of weeks). Subsyndromal, minor depressive, and hypomanic symptoms combined were nearly 3 times more frequent than syndromal-level major depressive and manic symptoms (29.9% vs 11.2% of weeks, respectively). Patients with BP-I changed symptom status an average of 6 times per year and polarity more than 3 times per year. Longer intake episodes and those with depression-only or cycling polarity predicted greater chronicity during long-term follow-up, as did comorbid drug-use disorder. Conclusions: The longitudinal weekly symptomatic course of BP-I is chronic. Overall, the symptomatic structure is primarily depressive rather than manic, and subsyndromal and minor affective symptoms predominate. Symptom severity levels fluctuate, often within the same patient over time. Bipolar I disorder is expressed as a dimensional illness featuring the full range (spectrum) of affective symptom severity and polarity.

- Cited by None

- Search by keyword

- Search by citation

Page 1 of 8

Longitudinal studies of bipolar patients and their families: translating findings to advance individualized risk prediction, treatment and research

Bipolar disorder is a broad diagnostic construct associated with significant phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity challenging progress in clinical practice and discovery research. Prospective studies of well-c...

- View Full Text

Sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of current rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: a multicenter Chinese study

Rapid cycling bipolar disorder (RCBD), characterized by four or more episodes per year, is a complex subtype of bipolar disorder (BD) with poorly understood characteristics.

Type of cycle, temperament and childhood trauma are associated with lithium response in patients with bipolar disorders

Lithium stands as the gold standard in treating bipolar disorders (BD). Despite numerous clinical factors being associated with a favorable response to lithium, comprehensive studies examining the collective i...

How effective are mood stabilizers in treating bipolar patients comorbid with cPTSD? Results from an observational study

Multiple traumatic experiences, particularly in childhood, may predict and be a risk factor for the development of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (cPTSD). Unfortunately, individuals with bipolar disord...

Perceived loneliness and social support in bipolar disorder: relation to suicidal ideation and attempts

The suicide rate in bipolar disorder (BD) is among the highest across all psychiatric disorders. Identifying modifiable variables that relate to suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) in BD may inform preventi...

Effectiveness of ultra-long-term lithium treatment: relevant factors and case series

The phenomenon of preventing the recurrences of mood disorders by the long-term lithium administration was discovered sixty years ago. Such a property of lithium has been unequivocally confirmed in subsequent ...

Prevention of suicidal behavior with lithium treatment in patients with recurrent mood disorders

Suicidal behavior is more prevalent in bipolar disorders than in other psychiatric illnesses. In the last thirty years evidence has emerged to indicate that long-term treatment of bipolar disorder patients wit...

Correlations between multimodal neuroimaging and peripheral inflammation in different subtypes and mood states of bipolar disorder: a systematic review

Systemic inflammation-immune dysregulation and brain abnormalities are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder (BD). However, the connections between peripheral inflammation and the brai...

Lithium: how low can you go?

Why is lithium [not] the drug of choice for bipolar disorder a controversy between science and clinical practice.

During over half a century, science has shown that lithium is the most efficacious treatment for bipolar disorder but despite this, its prescription has consistently declined internationally during recent deca...

Biomarkers for neurodegeneration impact cognitive function: a longitudinal 1-year case–control study of patients with bipolar disorder and healthy control individuals

Abnormalities in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-amyloid-beta (Aβ)42, CSF-Aβ40, CSF-Aβ38, CSF-soluble amyloid precursor proteins α and β, CSF-total-tau, CSF-phosphorylated-tau, CSF-neurofilament light protein (NF-L)...

Cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder in people with bipolar disorder: a case series

Social anxiety disorder increases the likelihood of unfavourable outcomes in people with bipolar disorder. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the first-line treatment for social anxiety disorder. However, ...

Lithium prescription trends in psychiatric inpatient care 2014 to 2021: data from a Bavarian drug surveillance project

Lithium (Li) remains one of the most valuable treatment options for mood disorders. However, current knowledge about prescription practices in Germany is limited. The objective of this study is to estimate the...

Lifetime risk of severe kidney disease in lithium-treated patients: a retrospective study

Lithium is an essential psychopharmaceutical, yet side effects and concerns about severe renal function impairment limit its usage.

Factors associated with suicide attempts in the antecedent illness trajectory of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia

Factors associated with suicide attempts during the antecedent illness trajectory of bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia (SZ) are poorly understood.

Behavioral lateralization in bipolar disorders: a systematic review

Bipolar disorder (BD) is often seen as a bridge between schizophrenia and depression in terms of symptomatology and etiology. Interestingly, hemispheric asymmetries as well as behavioral lateralization are shi...

High lithium concentration at delivery is a potential risk factor for adverse outcomes in breastfed infants: a retrospective cohort study

Neonatal effects of late intrauterine and early postpartum exposure to lithium through mother’s own milk are scarcely studied. It is unclear whether described symptoms in breastfed neonates are caused by place...

Key questions on the long term renal effects of lithium: a review of pertinent data

For over half a century, it has been widely known that lithium is the most efficacious maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder. Despite thorough research on the long-term effects of lithium on renal functio...

Controversies regarding lithium-associated weight gain: case–control study of real-world drug safety data

The impact of long-term lithium treatment on weight gain has been a controversial topic with conflicting evidence. We aim to assess reporting of weight gain associated with lithium and other mood stabilizers c...

Differential diagnosis of unipolar versus bipolar depression by GSK3 levels in peripheral blood: a pilot experimental study

The differential diagnosis of patients presenting for the first time with a depressive episode into unipolar disorder versus bipolar disorder is crucial to establish the correct pharmacological therapy (antide...

Supra-second interval timing in bipolar disorder: examining the role of disorder sub-type, mood, and medication status

Widely reported by bipolar disorder (BD) patients, cognitive symptoms, including deficits in executive function, memory, attention, and timing are under-studied. Work suggests that individuals with BD show imp...

Association between childhood trauma, cognition, and psychosocial function in a large sample of partially or fully remitted patients with bipolar disorder and healthy participants

Childhood trauma (CT) are frequently reported by patients with bipolar disorder (BD), but it is unclear whether and how CT contribute to patients’ cognitive and psychosocial impairments. We aimed to examine th...

Countering the declining use of lithium therapy: a call to arms

For over half a century, it has been widely known that lithium is the most efficacious treatment for bipolar disorder. Yet, despite this, its prescription has consistently declined over this same period of tim...

Paediatric bipolar disorder: an age-old problem

Nrx-101 (d-cycloserine plus lurasidone) vs. lurasidone for the maintenance of initial stabilization after ketamine in patients with severe bipolar depression with acute suicidal ideation and behavior: a randomized prospective phase 2 trial.

We tested the hypothesis that, after initial improvement with intravenous ketamine in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) with severe depression and acute suicidal thinking or behavior, a fixed-dose combinatio...

The IBER study: a feasibility randomised controlled trial of imagery based emotion regulation for the treatment of anxiety in bipolar disorder

Intrusive mental imagery is associated with anxiety and mood instability within bipolar disorder and therefore represents a novel treatment target. Imagery Based Emotion Regulation (IBER) is a brief structured...

Mitochondrial genetic variants associated with bipolar disorder and Schizophrenia in a Japanese population

Bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia (SZ) are complex psychotic disorders (PSY), with both environmental and genetic factors including possible maternal inheritance playing a role. Some studies have investi...

Differential characteristics of bipolar I and II disorders: a retrospective, cross-sectional evaluation of clinical features, illness course, and response to treatment

The distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II disorder and its treatment implications have been a matter of ongoing debate. The aim of this study was to examine differences between patients with bipolar I a...

Neonatal admission after lithium use in pregnant women with bipolar disorders: a retrospective cohort study

Lithium is the preferred treatment for pregnant women with bipolar disorders (BD), as it is most effective in preventing postpartum relapse. Although it has been prescribed during pregnancy for decades, the sa...

Rates and associations of relapse over 5 years of 2649 people with bipolar disorder: a retrospective UK cohort study

Evidence regarding the rate of relapse in people with bipolar disorder (BD), particularly from the UK, is lacking. This study aimed to evaluate the rate and associations of clinician-defined relapse over 5 yea...

Exploratory study of ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation and age of onset of bipolar disorder

Sunlight contains ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation that triggers the production of vitamin D by skin. Vitamin D has widespread effects on brain function in both developing and adult brains. However, many people l...

Characteristics of rapid cycling in 1261 bipolar disorder patients

Rapid-cycling (RC; ≥ 4 episodes/year) in bipolar disorder (BD) has been recognized since the 1970s and associated with inferior treatment response. However, associations of single years of RC with overall cycl...

Clinicians’ preferences and attitudes towards the use of lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders around the world: a survey from the ISBD Lithium task force

Lithium has long been considered the gold-standard pharmacological treatment for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders (BD) which is supported by a wide body of evidence. Prior research has shown a st...

Phenotype fingerprinting of bipolar disorder prodrome

Detecting prodromal symptoms of bipolar disorder (BD) has garnered significant attention in recent research, as early intervention could potentially improve therapeutic efficacy and improve patient outcomes. T...

Predictors of adherence to electronic self-monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder: a contactless study using Growth Mixture Models

Several studies have reported on the feasibility of electronic (e-)monitoring using computers or smartphones in patients with mental disorders, including bipolar disorder (BD). While studies on e-monitoring ha...

Racial differences in the major clinical symptom domains of bipolar disorder

Across clinical settings, black individuals are disproportionately less likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder compared to schizophrenia, a traditionally more severe and chronic disorder with lower expec...

Methylomic biomarkers of lithium response in bipolar disorder: a clinical utility study

Response to lithium (Li) is highly variable in bipolar disorders (BD). Despite decades of research, no clinical predictor(s) of response to Li prophylaxis have been consistently identified. Recently, we develo...

A compelling need to empirically validate bipolar depression

Structured physical exercise for bipolar depression: an open-label, proof-of concept study.

Physical exercise (PE) is a recommended lifestyle intervention for different mental disorders and has shown specific positive therapeutic effects in unipolar depressive disorder. Considering the similar sympto...

Experiences that matter in bipolar disorder: a qualitative study using the capability, comfort and calm framework

When assessing the value of an intervention in bipolar disorder, researchers and clinicians often focus on metrics that quantify improvements to core diagnostic symptoms (e.g., mania). Providers often overlook...

Emotion regulation in bipolar disorder type-I: multivariate analysis of fMRI data

Bipolar disorder type-I (BD-I) patients are known to show emotion regulation abnormalities. In a previous fMRI study using an explicit emotion regulation paradigm, we compared responses from 19 BD-I patients a...

Lithium levels and lifestyle in patients with bipolar disorder: a new tool for self-management

Patients should get actively involved in the management of their illness. The aim of this study was to assess the influence of lifestyle factors, including sleep, diet, and physical activity, on lithium levels...

Reduced parenting stress following a prevention program decreases internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder

Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (OBD) are at risk for developing mental disorders, and the literature suggests that parenting stress may represent an important risk factor linking parental psychopat...

Stigma in people living with bipolar disorder and their families: a systematic review

Stigma affects different life aspects in people living with bipolar disorder and their families. This study aimed to examining the experience of stigma and evaluating predictors, consequences and strategies to...

Lithium use in childhood and adolescence, peripartum, and old age: an umbrella review

Lithium is one of the most consistently effective treatment for mood disorders. However, patients may show a high level of heterogeneity in treatment response across the lifespan. In particular, the benefits o...

Risk of childhood trauma exposure and severity of bipolar disorder in Colombia

Bipolar disorder (BD) is higher in developing countries. Childhood trauma exposure is a common environmental risk factor in Colombia and might be associated with a more severe course of bipolar disorder in Low...

A systematic review on the effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy for improving mood symptoms in bipolar disorders

Evidence-based psychotherapies available to treat patients with bipolar disorders (BD) are limited. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) may target several common symptoms of BD. We conducted a systematic review...

Bipolar disorder and sexuality: a preliminary qualitative pilot study

Individuals with mental health disorders have a higher risk of sexual problems impacting intimate relations and quality of life. For individuals with bipolar disorder (BD) the mood shifts might to a particular...

Long-term lithium therapy and risk of chronic kidney disease, hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcemia: a cohort study

Lithium is well recognized as the first-line maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder (BD). However, besides therapeutic benefits attributed to lithium therapy, the associated side effects including endocrin...

The association of genetic variation in CACNA1C with resting-state functional connectivity in youth bipolar disorder

CACNA1C rs1006737 A allele, identified as a genetic risk variant for bipolar disorder (BD), is associated with anomalous functional connectivity in adults with and without BD. Studies have yet to investigate the ...

- Editorial Board

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

- ISSN: 2194-7511 (electronic)

- Open access

- Published: 18 April 2024

A bibliometric and visual analysis of cognitive function in bipolar disorder from 2012 to 2022

- Xiaohong Cui 4 , 5 na1 ,

- Tailian Xue 1 na1 ,

- Zhiyong Zhang 1 ,

- Hong Yang 2 &

- Yan Ren 3

Annals of General Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 13 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

43 Accesses

Metrics details

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic psychiatric disorder that combines hypomania or mania and depression. The study aims to investigate the research areas associated with cognitive function in bipolar disorder and identify current research hotspots and frontier areas in this field.

Methodology

Publications related to cognitive function in BD from 2012 to 2022 were searched on the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) database. VOSviewer, CiteSpace, and Scimago Graphica were used to conduct this bibliometric analysis.

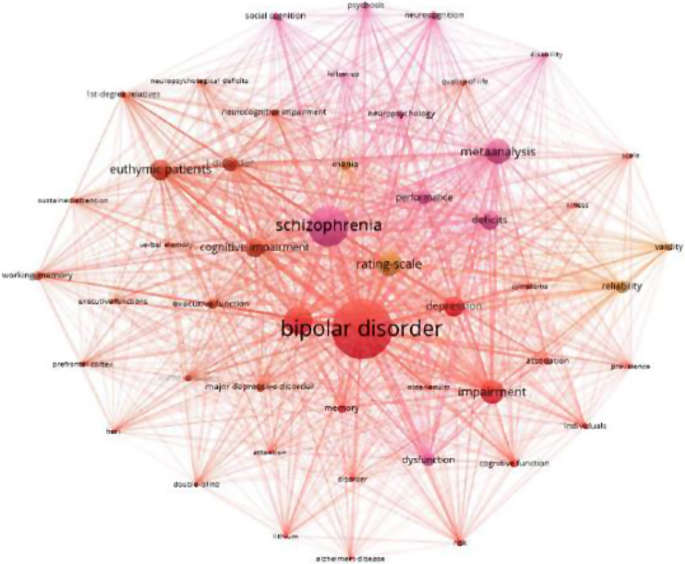

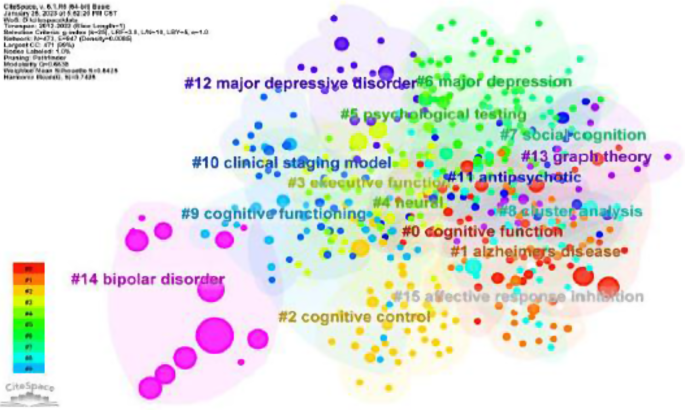

A total of 989 articles on cognitive function in BD were included in this review. These articles were mainly from the United States, China, Canada, Spain and the United Kingdom. Our results showed that the journal “ Journal of Affective Disorders ” published the most articles. Apart from “Biploar disorder” and “cognitive function”, the terms “Schizophrenia”, “Meta analysis”, “Rating scale” were also the most frequently used keywords. The research on cognitive function in bipolar disorder primarily focused on the following aspects: subgroup, individual, validation and pathophysiology.

Conclusions

The current concerns and hotspots in the filed are: “neurocognitive impairment”, “subgroup”, “1st degree relative”, “mania”, “individual” and “validation”. Future research is likely to focus on the following four themes: “Studies of the bipolar disorder and cognitive subgroups”, “intra-individual variability”, “Validation of cognitive function tool” and “Combined with pathology or other fields”.

Bipolar disorder presents a complex clinical presentation. It is characterized by alternating episodes of mania and depression, and is a serious mental health problem with a high rate of disability and difficult to cure [ 1 ]. The phenotypic manifestations of BD include not only core abnormalities in mood regulation, but also cognitive impairments, sleep/wake disturbances, and a high prevalence of comorbidities in both internal medicine and psychiatry. Cognitive function, also known as neurocognitive function, refers to the ability of the human brain to process information, including memory, executive function, space, time, language comprehension and expression. The current cognitive dysfunction in patients with bipolar disorder primarily affects memory, attention, executive function and so on [ 2 ].

In recent years, there has been increasing attention on cognitive functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. For example, a study has shown that individuals with bipolar disorder experience cognitive impairments during periods of remission as well as during acute episodes of depression or mania. Cognitive impairment is associated with multiple factors, including age of onset, duration of remission, and cognitive impairment, which are also intrinsic phenotypes of the disease [ 3 ]. Different diseases cause varying degrees of cognitive impairment. Patients with schizophrenia exhibit comprehensive cognitive decline, while those with bipolar disorder primarily experience impairment in memory, attention, and executive function, especially during acute episodes. The classification of bipolar disorder also corresponds to different areas of cognitive impairment. The impact of medication treatment on the cognitive function of bipolar disorder patients is contradictory, requiring a combined approach with other therapeutic methods to improve patient cognition [ 4 ]. The assessment of cognitive function is also a research prominent topic in this field. The assessment of cognitive function in bipolar disorder includes both objective and subjective aspects. Various neuropsychological tests, such as the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) and Rapid Visual Information Processing (RVP) test, are used to assess objective cognitive function in individuals with bipolar disorder. Subjective cognitive function assessment can be performed using the Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ) [ 5 ]. In addition to the above assessment tools, the results of another study showed: for patients with BD in partial or full remission, the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP) and the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Scale (COBRA) are effective tools for screening objective and subjective cognitive impairments, respectively [ 6 ]. These findings indicate that we need to assess different aspects of cognitive impairment in patients using various scales. This will help us better understand their cognitive performance and provide assistance for clinical treatment.

Bibliometrics is the analysis of published information (books, journal articles, datasets, blogs) and associated metadata (abstracts, keywords, citations). It describes or shows the relationship between published works by using statistical data [ 7 ]. The characteristics of publications and the relationships between publications can be described by qualitative and quantitative analysis. Cognitive function is currently a hot topic of research in bipolar disorder, but there are no bibliometric articles yet, although there are many articles on cognitive function in bipolar disorder.

In this article, we use CiteSpace and VOSviewer software to review the research of cognitive function in bipolar disorder in the past 12 years (from 2012 to 2022) to learn the status of international research, the shift in research hotspots and emerging trends in this field.

Research methodology

Data sources and search strategy.

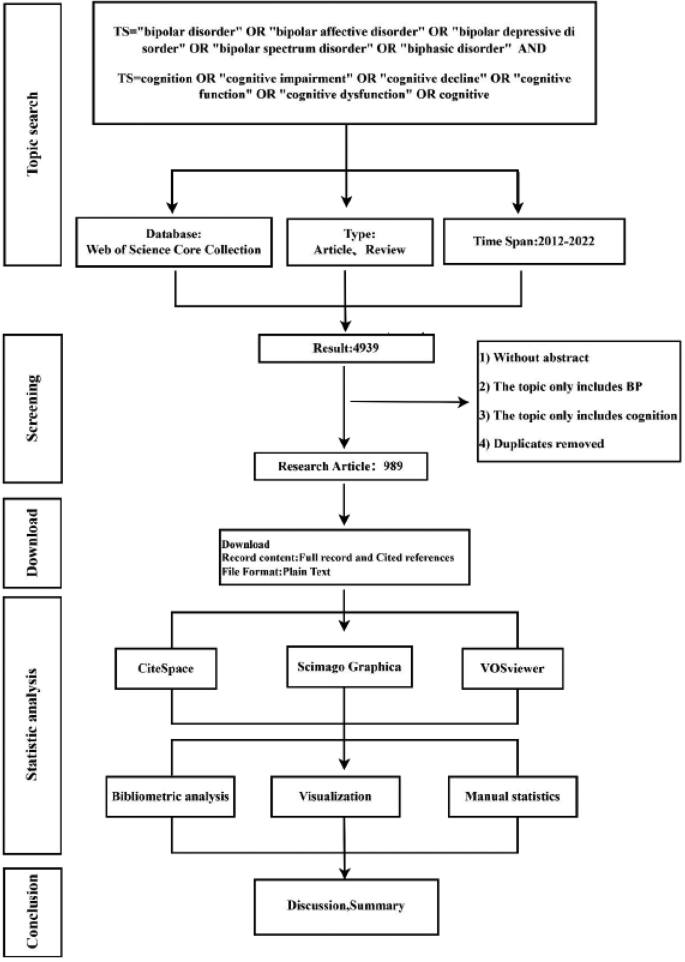

This study searched the related literature of cognitive function in bipolar disorder from the Web of Science (core collection) database, The reason for choosing WoSCC is that it is a high-quality digital literature resources database, suitable for the quantitative analysis of literature. The retrieval formula is TS="bipolar disorder” OR “bipolar affective disorder” OR “bipolar depressive disorder” OR “bipolar spectrum disorder” OR “biphasic disorder” AND TS = cognition OR “cognitive impairment” OR “cognitive decline” OR “cognitive function” OR “cognitive dysfunction” OR cognitive, selected over a period of 2012–2022, analyzed the type of literature as articles and reviews, and included the studies without regard to language. Through the analysis of the titles, abstracts and keywords of the article, a total of 4939 articles were searched, 1005 articles were preliminarily screened out, 989 articles were obtained (865 articles, 124 reviews) (Fig. 1 ).

Flow chart of scientometric analysis

Research tools

In this study, VOSviewer software (version 1.6.18) on WoSCC database is applied to conduct co-occurrence analysis, combined with Scimago Graphica software to achieve a country map visualization analysis. Using CiteSpace (version of 6.1.R6) software for the database author co-operation analysis, keyword cluster analysis, literature co-citations and keyword mutation analysis. VOSviewer application developed by Nees Jan van Eck and Ludo Waltman (Leiden University) in 2010, can be used for a variety of network analysis, including collaborative analysis, keyword co-occurrence analysis, citation and co-citation analysis, and bibliographic coupling. It can be used to conduct co-authorship analysis, keyword co-occurrence analysis, citation and co-citation analysis, and bibliographic coupling [ 8 ]. Citespace is a software developed by Professor Chaomei Chen of Drexel University (Philadelphia, USA) for the visual analysis of scientific references. With the software, we can generate a series of visual knowledge atlases to understand the research hotspots in the field, delve into the forefront of its development, and ascertain emerging trends [ 9 ].

The parameters used for co-occurrence analysis using VOSviewer are the default parameters for the software, and the parameters used in CiteSpace are as follows: time slices (2012–2022), number of years per slice (1), node types (author collaborations, co-citations, and keywords), pruning (pathfinder, pruning sliced network, pruning the merged network), g-index (k = 25, literature co-citations are k = 15).

Analysis of publication years

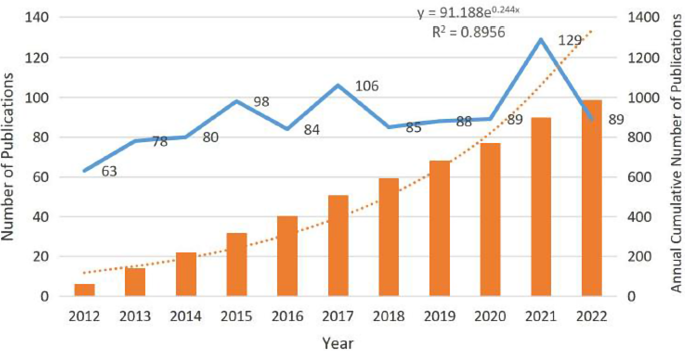

Distribution of publication from 2012 to 2022

There are a total of 989 articles were used in this study from 57 countries. Figure 2 shows the distribution of publication years for articles in the field of cognitive function in bipolar disorder. Overall, the volume of articles in this field is relatively balanced, with more than 60 articles published annually starting from 2012. The number of articles published in 2018–2020 remained relatively stable. The highest volume of articles was in 2021, with 129 articles published. The annual cumulative volume model aligns with the annual growth data y = 91.188e 0.244x (R 2 = 0.8956). This also shows that the field of cognitive function in bipolar disorder has garnered significant attention from scholars, with the development of society and technology, the study of cognition in the context of bipolar disorder has become an important and hot topic.

Analysis of author

By analyzing the authors of the literature cited in this paper, we aimed to gain insights into the prominent scholars and core strength within this research area. Famous scholar Price pointed out that, in the same subject, half of the papers are written by a group of high-productivity authors, and the number of authors in this group is approximately equal to the square root of the total number of authors [ 10 ].

According to the Price’s Law, the minimum number of core authors in the field is m = 4.79, so authors with 5 or more posts (including 5) are positioned as core authors in the field, where they are active professionals. Table 1 shows the top five productivity authors with contributions in this area. Top of the list was Vieta E, professor and chair of psychiatry at the University of Barcelona, with the highest number of published articles (41). He spearheads research focused on investigating cognitive function, cognitive impairment, and clinical manifestations associated with bipolar disorder, leading the Bipolar Disorder and Depression Project in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

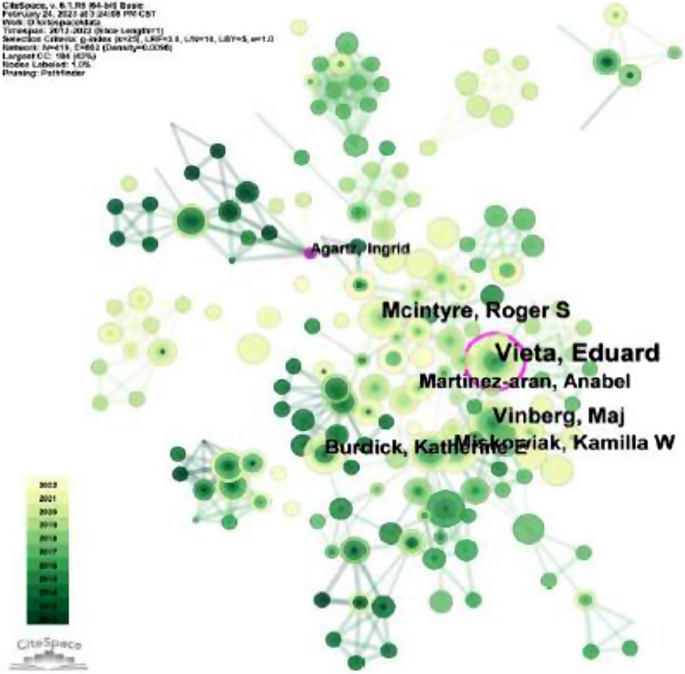

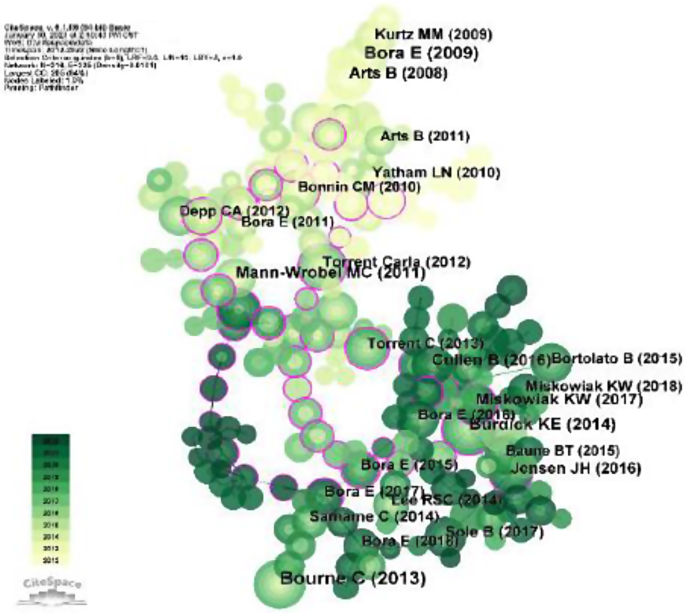

We then analyzed the author’s cooperation relationship. These studies published between 2012 and 2022, the year per slice for analysis is 1 year. The author cooperation network is shown in Fig. 3 (N = 419, E = 862). The circle size of the node represents the number of publications.

The centrality indicates that an author has a close cooperation relationship with other authors. According to Table 1 , the centrality of Vieta E is 0.14 (centrality > 0.1), indicating that the author has cooperation with multiple authors in the field, while the centrality of Vinberg M is 0.02. The author’s cooperation network graph also shows that Vinberg M is far away from other high-yielding authors, indicating that the author has less cooperation with other high-yielding authors in the research of cognitive function in bipolar disorder.

Author collaboration network analysis. The shorter the distance between two nodes the thicker the connection, indicating a higher level of collaboration between the two authors. Green nodes represent earlier published studies, while yellow nodes represent more recent studies

Analysis of the most productive journals

The analysis of the journals in literature shows that journals published in this field belong to the medical field except a few comprehensive journals in the past ten years. The top 10 most publication journals have shown in Table 2 . Journals with more than 60 published articles were Journal of Affective Disorders , Psychiatry Research and Bipolar Disorders , with 185, 72, and 66 articles, respectively. Among them, PLOS ONE is an open-source journal, with 20 citations, ranking 10th in the number of published journals.

Analyzing of journal citation founds that (Table 2 ) the most cited journals are the top medical journal “ Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica ”, with a total of 27 articles cited up to 47 times. It indicates that the journal publishes high-quality articles and is of widespread interest in the field of cognitive function in bipolar disorder. The contents published in this journal include: empirical studies, factor studies, and the influence of variable indicators on cognitive function in patients with bipolar disorder.

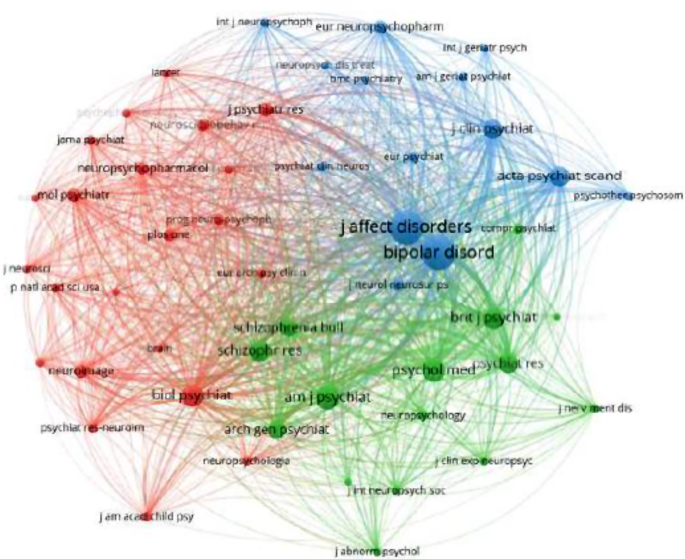

Furthermore, a visual analysis of the journal co-citation network reveals the presence of three clusters (Fig. 4 , in supplementary material). According to the subject of the co-citation literature clustering, it divided into three different themes. The top 3 most cited journals are Journal of Affective Disorders (3807 citations), Bipolar Disorders (2186 citations), and American Journal of Psychiatry (1284 citations). All three of these journals are in the JCR1. The most cited journal, Journal of Affective Disorders , which includes articles on affective disorder. It covers a wide range of subjects, including neuroimaging, cognitive neuroscience, genetics, molecular biology, etc. This is in line with the research focus on cognitive function in bipolar disorder.

Co-citation resource

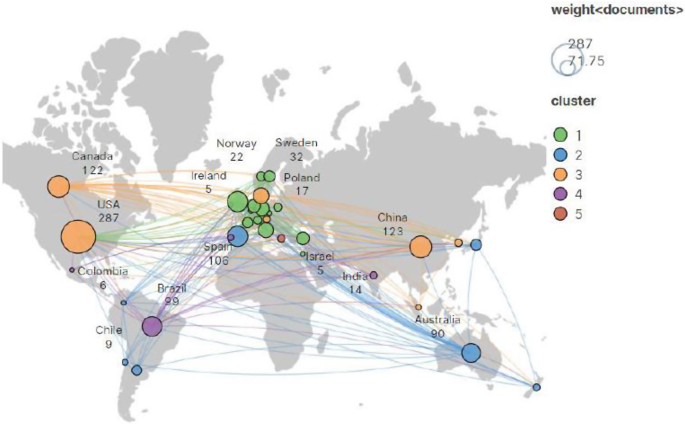

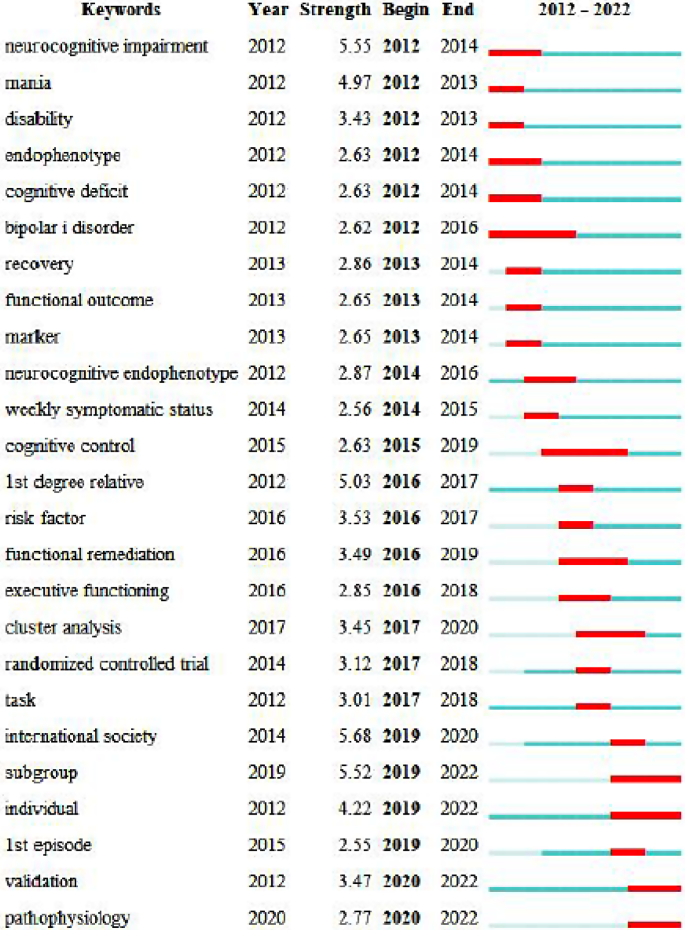

Analysis of the most productive countries/regions