An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Malays Fam Physician

- v.17(1); 2022 Mar 28

Case scenario: Management of major depressive disorder in primary care based on the updated Malaysian clinical practice guidelines

Uma visvalingam.

MBBS (MAHE), Master of Medicine (Psychiatry) (UKM), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Putrajaya, Putrajaya, Malaysia

Umi Adzlin Silim

MD (UKM), M. Med (Psychiatry) (UKM), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Serdang, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Ahmad Zahari Muhammad Muhsin

MB., BCh., BAO (UCD, Ireland), M. Psych Med (Malaya), Department of Psychological Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Firdaus Abdul Gani

MBBS (Malaya) M.Med (Psy) (USM) CMIA (NIOSH), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah, Temerloh, Pahang, Malaysia

Noormazita Mislan

MB, BCh, BAO (Ireland), M Med. (Psychiatry) (UKM), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Tuanku Ja'afar, Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Noor Izuana Redzuan

MBBS (Malaya), Dr in Psychiatry (UKM), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Raja Permaisuri Bainun, Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia

Peter Kuan Hoe Low

MB, BCh, BAO (Ireland), M.Psych Med (UM), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Sing Yee Tan

MBBS (Malaya), M.Med (Family Med) (UM), Klinik Kesihatan Jenjarom, Jenjarom Selangor, Malaysia

Masseni Abd Aziz

MD (USM) M Med (Fammed) USM, Klinik Kesihatan Umbai, Merlimau, Melaka, Malaysia

Aida Syarinaz Ahmad Adlan

MBBS (Malaya), M. Psych Med (UM), PostGrad. Dip. (Dynamic Psychotherapy) (Mcgill University), Department of Psychological Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya Kuala, Lumpur, Malaysia

Suzaily Wahab

MD (UKM), MMed Psych (UKM), Hospital Canselor Tuanku Muhriz UKM, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Aida Farhana Suhaimi

B. Psych (Adelaide), M. Psych (Clin. Psych) (Tasmania), PhD (Psychological Medicine) (UPM), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Putrajaya, Putrajaya, Malaysia

Nurul Syakilah Embok Raub

BPharm (Hons) (CUCMS), MPH (Malaya), Pharmacy Enforcement Branch, Selangor Health State Department, Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Siti Mariam Mohtar

BPharm (UniSA), Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Section (MaHTAS), Ministry of Health Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia

Mohd Aminuddin Mohd Yusof

MD (UKM), MPH (Epidemiology) (Malaya), Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Section (MaHTAS), Ministry of Health Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia, Email: moc.oohay@rd2ma

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common but complex illness that is frequently presented in the primary care setting. Managing this disorder in primary care can be difficult, and many patients are underdiagnosed and/or undertreated. The Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) on the Management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (2nd ed.), published in 2019, covers screening, diagnosis, treatment and referral (which frequently pose a challenge in the primary care setting) while minimising variation in clinical practice.

Introduction

MDD is one of the most common mental illnesses encountered in primary care. It presents with a combination of symptoms that may complicate its management.

This mental disorder requires specific treatment approaches and is projected to be the leading cause of the disease burden in 2030. 1 Patients experiencing this ailment are at elevated risk for early mortality from physical disorders and suicide. 2 In Malaysia in particular, MDD contributes to 6.9% of total Years Living with Disability. 3

Ensuring full functional recovery and prevention of relapse makes remission the targeted outcome for treatment of MDD. In contrast, nonremission of depressive symptoms in MDD can impact functionality 4 and subsequently amplify the economic burden that the illness imposes.

About the new edition

The highlights of the updated CPG MDD (2nd ed.) are as follows:

- emphasis on psychosocial and psychological interventions, particularly for mild to moderate MDD

- inclusion of all second-generation antidepressants as the first-line pharmacotherapy

- introduction of new emerging treatments, ie. intravenous ketamine for acute phase and intranasal esketamine for next-step treatment/treatment-resistant MDD

- improvement in pre-treatment screening and monitoring of treatment

- integration of mental health into other health services with emphasis on collaborative care

- addition of 2 new chapters on special populations (pregnancy and postpartum, chronic medical illness) and table on safety profile of pharmacotherapy in pregnancy and breastfeeding

- comprehensive, holistic biopsychosocial-spiritual approaches addressing psychospirituality

Details of the evidence supporting the above statements can be found in Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Major Depressive Disorder (2nd ed.) 2019, available on the following websites: http://www.moh.gov.my (Ministry of Health Malaysia) and http://www.acadmed.org.my (Academy of Medicine). Corresponding organisation: CPG Secretariat, Health Technology Assessment Section, Medical Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia; contactable at ym.vog.hom@aisyalamath .

Statement of intent

This is a support tool for implementation of CPG Management of Major Depressive Disorder (2nd ed.).

Healthcare providers are advised of their responsibility to implement this evidence-based CPG in their local context. Such implementation will lead to capacity building to ensure better accessibility of psychosocial and psychological services. More options in pharmacotherapy facilitate flexibility in prescribing antidepressants among clinicians. Further integration of mental health into other health services, upscaling of mental health service development in perinatal and medical services, and enhancement of collaborative care will incorporate holistic approaches into care.

Case Scenario

Tini is a female college student aged 24 years old. She comes to the health clinic accompanied by a friend and complains of several symptoms that she has experienced over the past 4 weeks. She reports:

- difficulty falling asleep, feeling tired after waking up in the morning and experiencing headaches

- difficulty staying focused during classes. These symptoms have led to deterioration in her study and prompted her to seek advice from the doctor.

Will you screen her for depression?

Yes, because the patient presents with multiple vague symptoms and sleep disturbance. 5 (Refer to Subchapter 2.1, page 3 in CPG.)

What tools are used to screen for depression?

Screening tools for depression are:

- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

- Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS)

- Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

- Whooley Questions

Screening for depression using Whooley Questions in primary care may be considered in people at risk. 5

( Refer to Subchapter 2.1, pages 3 and 4 in CPG. )

- “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?”

- “During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

The doctor decides to use Whooley Questions, and Tini answers “yes” to both questions.

How would you proceed from here to further assess for depression?

Assessment of depression consists of:

- detailed history taking (Refer to Subchapter 2.2, page 4 in CPG.)

- mental state examination (MSE), including evaluation of symptom severity, presence of psychotic symptoms and risk of harm to self and others

- physical examination to rule out organic causes

- investigations where indicated — biological and psychosocial investigations

Upon further assessment, Tini reveals that she feels overwhelmingly sad. She is frequently tearful and reports feeling excessively guilty, blaming herself for not performing well enough in her studies. Her postings on social media have been revolving around themes of self-defeat. Despite feeling low, she still strives to attend classes and complete her assignments. However, her academic performance has exhibited a marked deterioration. There is no history to suggest hypomanic, manic or psychotic symptoms. She denies using any illicit substances or alcohol. Her menstrual cycle is normal and does not correspond to her mood changes.

MSE reveals a young lady who appears to be in distress. Rapport is easily established, but her eyes are downcast. Her speech is relevant, with low tone. She describes her mood as sad; she is tearful while talking about her poor results, with appropriate affect. She harbours multiple unhelpful thoughts, eg. “I’m a failure” and “I’m useless”. She exhibits no suicidal ideations, delusions or hallucinations. Her concentration is poor, and insight is partial.

Physical examination reveals no recent selfharm scars, and examination of other systems is unremarkable. Biological investigations such as full blood count and thyroid function test are within normal range. Corroborative history is taken from accompanying person to verify the symptoms.

How would you arrive at the diagnosis and severity?

Diagnosis of depression can be made using the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) or the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). 5 (Refer to Appendix 3 and 4, pages 73-76 in CPG.) 6 , 7

In the last 2 weeks, Tini has been experiencing:

- poor concentration

- excessive guilt

These symptoms have caused marked impairment in her academic functioning. Thus, she is diagnosed as having MDD with mild to moderate severity in acute phase and can be treated in primary care.

Severity according to DSM-5

- Five or more symptoms are present, which cause distress but are manageable

- Result in minor impairment in social or occupational functioning

- Symptom presentation and functional impairment between 2 severities

- Most of the symptoms are present with marked impairment in functioning

What can be offered to this patient?

Psychosocial interventions and psychotherapy with or without pharmacotherapy. 5 (Refer to Algorithm 1. Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder, page xii in CPG)

ALGORITHM 1. TREATMENT OF MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Psychosocial interventions include the following:

- symptoms and course of depression

- biopsychosocial model of aetiology

- pharmacotherapy for acute phase and maintenance

- drug side effects and complications

- importance of medication adherence

- early signs of recurrence

- management of relapse and recurrence

- counselling/non-directive supportive therapy - aims to guide the person in decision-making and allow to ventilate their emotions

- relaxation - a method to help a person attain a state of calmness, eg. breathing exercise, progressive muscle relaxation, relaxation imagery

- peer intervention - eg. peer support group

- exercise - activity of 45-60 minutes per session, up to 3 times per week, and prescribed for 10-12 weeks

(Refer to subchapter 4.1.1, pages 9-12 in CPG.)

However, the doctor may choose to start antidepressant medication as an initial measure in some situations, for example:

- past history of moderate to severe depression

- patient’s preference

- previous response to antidepressants

- lack of response to non-pharmacotherapy interventions

What are the types of psychotherapy that can be offered in mild to moderate MDD, and what factors should be considered before starting psychotherapy?

Psychotherapy for the treatment of MDD has been shown to reduce psychological distress and improve recovery through the therapeutic relationship between the therapist and the patient.

In mild to moderate MDD, psychosocial intervention and psychotherapy should be offered, based on resource availability, and may include but are not restricted to the following 5 :

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- Interpersonal therapy

- Problem-solving therapy

- Behavioural therapy

- Internet-based CBT

The type of psychotherapy offered to the patient will depend on various factors, including 5 :

- patient preference and attitude

- nature of depression

- availability of trained therapist

- therapeutic alliance

- availability of therapy

(Refer to Subchapter 4.1.1, page 17 in CPG.)

After shared-decision making, Tini receives psychosocial intervention, that includes:

- psychoeducation

- non-directive supportive therapy

- lifestyle modification, e.g. restoring healthy sleep hygiene and adopting healthy eating habits

- relaxation, e.g. progressive muscle relaxation, imagery and breathing technique

Tini will benefit from CBT due to her multiple unhelpful thoughts, for example, “I’m a failure” and “I’m useless”.

CBT helps improve understanding of the impact of a person’s unhelpful thoughts on current behaviour and functioning through cognitive restructuring and a behavioural approach. By learning to correctly identify these negative thinking patterns, Tini can then challenge such thoughts repeatedly to replace disordered thinking with more rational, balanced and healthy thinking. However, she is not able to commit to regular sessions of CBT due to a demanding academic schedule and upcoming final examination. After further discussion, Tini opts for pharmacotherapy.

What are the options for pharmacotherapy?

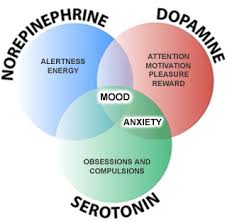

The choice of antidepressant medication will depend on various factors, including efficacy and tolerability, patient profile and comorbidities, concomitant medications and drug-drug interactions, cost and availability, as well as the patient’s preference. Taking into account efficacy and side effect profiles, most second-generation antidepressants, namely selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs), melatonergic agonist and serotonergic antagonist, noradrenaline/dopamine-reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) and a multimodal antidepressants may be considered as the initial treatment medication, while the older antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) may be subsequently considered for a later choice. 5 (Refer to Subchapter 4.1.2, page 18 in CPG.)

Since Tini is being seen at a health clinic, the widely available SSRIs are sertraline and fluvoxamine. Sertraline has fewer gastrointestinal side effects and drug interactions compared with fluvoxamine. TCAs are not the treatment of choice due to prominent side effects. Tini is put on tablet sertraline 50 mg daily and educated on the anticipated onset of response and possible side effects. Short-term and low dose benzodiazepine, eg. alprazolam or lorazepam, may be offered as an adjunct to treat her insomnia. (Refer to Subchapter 4.1.2, page 24 in CPG.) Tini is given tablet lorazepam 0.5 mg at night for 2 weeks. She is asked to come in for a follow-up.

What is her follow-up and monitoring plan?

The following should be done:

(Refer to Appendix 8, page 81 in CPG.)

- Titrate up by 50 mg within 1-2 weeks (but may be done earlier based on clinical judgement)

- Monitor biological parameters if indicated (Refer to Table 5. Ongoing monitoring during treatment of MDD, page 57 in CPG.)

During follow-up at 2 weeks, she is noted to show partial response despite being compliant with good tolerability. She is not experienceing nausea, diarrhoea, headache, constipation, dry mouth or somnolence. She reports being less tearful. Her sleep and ability to focus have improved. Tini has started engaging in regular exercise and practises relaxation, especially before sleep. Tablet sertraline is optimised to 100 mg daily, while tablet lorazepam is reduced to 0.5 mg PRN.

Tini is reviewed again within 4 weeks; during this subsequent follow-up, she achieves full remission. Tablet lorazepam is stopped. She is then advised to continue tablet sertraline for at least 6-9 months in maintenance phase. The aim in this phase is to prevent relapse and recurrence of MDD. In view of her young age, no comorbidities and good tolerability, repeated electrolyte monitoring is not indicated.

(Refer to Algorithm 2. Pharmacotherapy for Major Depressive Disorder, page xiii in CPG.)

ALGORITHM 2. PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Mental Health Case Study: Understanding Depression through a Real-life Example

Imagine feeling an unrelenting heaviness weighing down on your chest. Every breath becomes a struggle as a cloud of sadness engulfs your every thought. Your energy levels plummet, leaving you physically and emotionally drained. This is the reality for millions of people worldwide who suffer from depression, a complex and debilitating mental health condition.

Understanding depression is crucial in order to provide effective support and treatment for those affected. While textbooks and research papers provide valuable insights, sometimes the best way to truly comprehend the depths of this condition is through real-life case studies. These stories bring depression to life, shedding light on its impact on individuals and society as a whole.

In this article, we will delve into the world of mental health case studies, using a real-life example to explore the intricacies of depression. We will examine the symptoms, prevalence, and consequences of this all-encompassing condition. Furthermore, we will discuss the significance of case studies in mental health research, including their ability to provide detailed information about individual experiences and contribute to the development of treatment strategies.

Through an in-depth analysis of a selected case study, we will gain insight into the journey of an individual facing depression. We will explore their background, symptoms, and initial diagnosis. Additionally, we will examine the various treatment options available and assess the effectiveness of the chosen approach.

By delving into this real-life example, we will not only gain a better understanding of depression as a mental health condition, but we will also uncover valuable lessons that can aid in the treatment and support of those who are affected. So, let us embark on this enlightening journey, using the power of case studies to bring understanding and empathy to those who need it most.

Understanding Depression

Depression is a complex and multifaceted mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide. To comprehend the impact of depression, it is essential to explore its defining characteristics, prevalence, and consequences on individuals and society as a whole.

Defining depression and its symptoms

Depression is more than just feeling sad or experiencing a low mood. It is a serious mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest in activities that were once enjoyable. Individuals with depression often experience a range of symptoms that can significantly impact their daily lives. These symptoms include:

1. Persistent feelings of sadness or emptiness. 2. Fatigue and decreased energy levels. 3. Significant changes in appetite and weight. 4. Difficulty concentrating or making decisions. 5. Insomnia or excessive sleep. 6. feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or hopelessness. 7. Loss of interest or pleasure in activities.

Exploring the prevalence of depression worldwide

Depression knows no boundaries and affects individuals from all walks of life. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 264 million people globally suffer from depression. This makes depression one of the most common mental health conditions worldwide. Additionally, the WHO highlights that depression is more prevalent among females than males.

The impact of depression is not limited to individuals alone. It also has significant social and economic consequences. Depression can lead to impaired productivity, increased healthcare costs, and strain on relationships, contributing to a significant burden on families, communities, and society at large.

The impact of depression on individuals and society

Depression can have a profound and debilitating impact on individuals’ lives, affecting their physical, emotional, and social well-being. The persistent sadness and loss of interest can lead to difficulties in maintaining relationships, pursuing education or careers, and engaging in daily activities. Furthermore, depression increases the risk of developing other mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders or substance abuse.

On a societal level, depression poses numerous challenges. The economic burden of depression is significant, with costs associated with treatment, reduced productivity, and premature death. Moreover, the social stigma surrounding mental health can impede individuals from seeking help and accessing appropriate support systems.

Understanding the prevalence and consequences of depression is crucial for policymakers, healthcare professionals, and individuals alike. By recognizing the significant impact depression has on individuals and society, appropriate resources and interventions can be developed to mitigate its effects and improve the overall well-being of those affected.

The Significance of Case Studies in Mental Health Research

Case studies play a vital role in mental health research, providing valuable insights into individual experiences and contributing to the development of effective treatment strategies. Let us explore why case studies are considered invaluable in understanding and addressing mental health conditions.

Why case studies are valuable in mental health research

Case studies offer a unique opportunity to examine mental health conditions within the real-life context of individuals. Unlike large-scale studies that focus on statistical data, case studies provide a detailed examination of specific cases, allowing researchers to delve into the complexities of a particular condition or treatment approach. This micro-level analysis helps researchers gain a deeper understanding of the nuances and intricacies involved.

The role of case studies in providing detailed information about individual experiences

Through case studies, researchers can capture rich narratives and delve into the lived experiences of individuals facing mental health challenges. These stories help to humanize the condition and provide valuable insights that go beyond a list of symptoms or diagnostic criteria. By understanding the unique experiences, thoughts, and emotions of individuals, researchers can develop a more comprehensive understanding of mental health conditions and tailor interventions accordingly.

How case studies contribute to the development of treatment strategies

Case studies form a vital foundation for the development of effective treatment strategies. By examining a specific case in detail, researchers can identify patterns, factors influencing treatment outcomes, and areas where intervention may be particularly effective. Moreover, case studies foster an iterative approach to treatment development—an ongoing cycle of using data and experience to refine and improve interventions.

By examining multiple case studies, researchers can identify common themes and trends, leading to the development of evidence-based guidelines and best practices. This allows healthcare professionals to provide more targeted and personalized support to individuals facing mental health conditions.

Furthermore, case studies can shed light on potential limitations or challenges in existing treatment approaches. By thoroughly analyzing different cases, researchers can identify gaps in current treatments and focus on areas that require further exploration and innovation.

In summary, case studies are a vital component of mental health research, offering detailed insights into the lived experiences of individuals with mental health conditions. They provide a rich understanding of the complexities of these conditions and contribute to the development of effective treatment strategies. By leveraging the power of case studies, researchers can move closer to improving the lives of individuals facing mental health challenges.

Examining a Real-life Case Study of Depression

In order to gain a deeper understanding of depression, let us now turn our attention to a real-life case study. By exploring the journey of an individual navigating through depression, we can gain valuable insights into the complexities and challenges associated with this mental health condition.

Introduction to the selected case study

In this case study, we will focus on Jane, a 32-year-old woman who has been struggling with depression for the past two years. Jane’s case offers a compelling narrative that highlights the various aspects of depression, including its onset, symptoms, and the treatment journey.

Background information on the individual facing depression

Before the onset of depression, Jane led a fulfilling and successful life. She had a promising career, a supportive network of friends and family, and engaged in hobbies that brought her joy. However, a series of life stressors, including a demanding job, a breakup, and the loss of a loved one, began to take a toll on her mental well-being.

Jane’s background highlights a common phenomenon – depression can affect individuals from all walks of life, irrespective of their socio-economic status, age, or external circumstances. It serves as a reminder that no one is immune to mental health challenges.

Presentation of symptoms and initial diagnosis

Jane began noticing a shift in her mood, characterized by persistent feelings of sadness and a lack of interest in activities she once enjoyed. She experienced disruptions in her sleep patterns, appetite changes, and a general sense of hopelessness. Recognizing the severity of her symptoms, Jane sought help from a mental health professional who diagnosed her with major depressive disorder.

Jane’s case exemplifies the varied and complex symptoms associated with depression. While individuals may exhibit overlapping symptoms, the intensity and manifestation of those symptoms can vary greatly, underscoring the importance of personalized and tailored treatment approaches.

By examining this real-life case study of depression, we can gain an empathetic understanding of the challenges faced by individuals experiencing this mental health condition. Through Jane’s journey, we will uncover the treatment options available for depression and analyze the effectiveness of the chosen approach. The case study will allow us to explore the nuances of depression and provide valuable insights into the treatment landscape for this prevalent mental health condition.

The Treatment Journey

When it comes to treating depression, there are various options available, ranging from therapy to medication. In this section, we will provide an overview of the treatment options for depression and analyze the treatment plan implemented in the real-life case study.

Overview of the treatment options available for depression

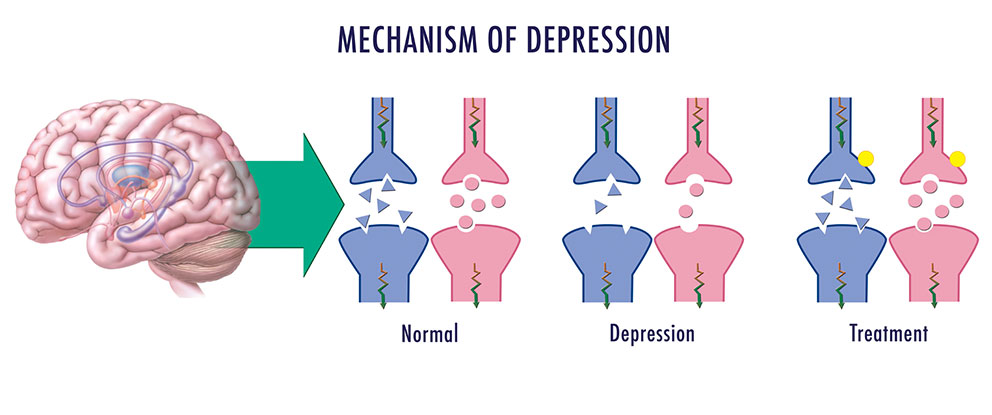

Treatment for depression typically involves a combination of approaches tailored to the individual’s needs. The two primary treatment modalities for depression are psychotherapy (talk therapy) and medication. Psychotherapy aims to help individuals explore their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, while medication can help alleviate symptoms by restoring chemical imbalances in the brain.

Common forms of psychotherapy used in the treatment of depression include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and psychodynamic therapy. These therapeutic approaches focus on addressing negative thought patterns, improving relationship dynamics, and gaining insight into underlying psychological factors contributing to depression.

In cases where medication is utilized, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed. These medications help rebalance serotonin levels in the brain, which are often disrupted in individuals with depression. Other classes of antidepressant medications, such as serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), may be considered in specific cases.

Exploring the treatment plan implemented in the case study

In Jane’s case, a comprehensive treatment plan was developed with the intention of addressing her specific needs and symptoms. Recognizing the severity of her depression, Jane’s healthcare team recommended a combination of talk therapy and medication.

Jane began attending weekly sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with a licensed therapist. This form of therapy aimed to help Jane identify and challenge negative thought patterns, develop coping strategies, and cultivate more adaptive behaviors. The therapeutic relationship provided Jane with a safe space to explore and process her emotions, ultimately helping her regain a sense of control over her life.

In conjunction with therapy, Jane’s healthcare provider prescribed an SSRI medication to assist in managing her symptoms. The medication was carefully selected based on Jane’s specific symptoms and medical history, and regular follow-up appointments were scheduled to monitor her response to the medication and adjust the dosage if necessary.

Analyzing the effectiveness of the treatment approach

The effectiveness of treatment for depression varies from person to person, and it often requires a period of trial and adjustment to find the most suitable intervention. In Jane’s case, the combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication proved to be beneficial. Over time, she reported a reduction in her depressive symptoms, an improvement in her overall mood, and increased ability to engage in activities she once enjoyed.

It is important to note that the treatment journey for depression is not always linear, and setbacks and challenges may occur along the way. Each individual responds differently to treatment, and adjustments might be necessary to optimize outcomes. Continuous communication between the individual and their healthcare team is crucial to addressing any concerns, monitoring progress, and adapting the treatment plan as needed.

By analyzing the treatment approach in the real-life case study, we gain insights into the various treatment options available for depression and how they can be tailored to meet individual needs. The combination of psychotherapy and medication offers a holistic approach, addressing both psychological and biological aspects of depression.

The Outcome and Lessons Learned

After undergoing treatment for depression, it is essential to assess the outcome and draw valuable lessons from the case study. In this section, we will discuss the progress made by the individual in the case study, examine the challenges faced during the treatment process, and identify key lessons learned.

Discussing the progress made by the individual in the case study

Throughout the treatment process, Jane experienced significant progress in managing her depression. She reported a reduction in depressive symptoms, improved mood, and a renewed sense of hope and purpose in her life. Jane’s active participation in therapy, combined with the appropriate use of medication, played a crucial role in her progress.

Furthermore, Jane’s support network of family and friends played a significant role in her recovery. Their understanding, empathy, and support provided a solid foundation for her journey towards improved mental well-being. This highlights the importance of social support in the treatment and management of depression.

Examining the challenges faced during the treatment process

Despite the progress made, Jane faced several challenges during her treatment journey. Adhering to the treatment plan consistently proved to be difficult at times, as she encountered setbacks and moments of self-doubt. Additionally, managing the side effects of the medication required careful monitoring and adjustments to find the right balance.

Moreover, the stigma associated with mental health continued to be a challenge for Jane. Overcoming societal misconceptions and seeking help required courage and resilience. The case study underscores the need for increased awareness, education, and advocacy to address the stigma surrounding mental health conditions.

Identifying the key lessons learned from the case study

The case study offers valuable lessons that can inform the treatment and support of individuals with depression:

1. Holistic Approach: The combination of psychotherapy and medication proved to be effective in addressing the psychological and biological aspects of depression. This highlights the need for a holistic and personalized treatment approach.

2. Importance of Support: Having a strong support system can significantly impact an individual’s ability to navigate through depression. Family, friends, and healthcare professionals play a vital role in providing empathy, understanding, and encouragement.

3. Individualized Treatment: Depression manifests differently in each individual, emphasizing the importance of tailoring treatment plans to meet individual needs. Personalized interventions are more likely to lead to positive outcomes.

4. Overcoming Stigma: Addressing the stigma associated with mental health conditions is crucial for individuals to seek timely help and access the support they need. Educating society about mental health is essential to create a more supportive and inclusive environment.

By drawing lessons from this real-life case study, we gain insights that can improve the understanding and treatment of depression. Recognizing the progress made, understanding the challenges faced, and implementing the lessons learned can contribute to more effective interventions and support systems for individuals facing depression.In conclusion, this article has explored the significance of mental health case studies in understanding and addressing depression, focusing on a real-life example. By delving into case studies, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of depression and the profound impact it has on individuals and society.

Through our examination of the selected case study, we have learned valuable lessons about the nature of depression and its treatment. We have seen how the combination of psychotherapy and medication can provide a holistic approach, addressing both psychological and biological factors. Furthermore, the importance of social support and the role of a strong network in an individual’s recovery journey cannot be overstated.

Additionally, we have identified challenges faced during the treatment process, such as adherence to the treatment plan and managing medication side effects. These challenges highlight the need for ongoing monitoring, adjustments, and open communication between individuals and their healthcare providers.

The case study has also emphasized the impact of stigma on individuals seeking help for depression. Addressing societal misconceptions and promoting mental health awareness is essential to create a more supportive environment for those affected by depression and other mental health conditions.

Overall, this article reinforces the significance of case studies in advancing our understanding of mental health conditions and developing effective treatment strategies. Through real-life examples, we gain a more comprehensive and empathetic perspective on depression, enabling us to provide better support and care for individuals facing this mental health challenge.

As we conclude, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of continued research and exploration of mental health case studies. The more we learn from individual experiences, the better equipped we become to address the diverse needs of those affected by mental health conditions. By fostering a culture of understanding, support, and advocacy, we can strive towards a future where individuals with depression receive the care and compassion they deserve.

Similar Posts

Auvelity: Understanding the Link Between Auvelity and Depression

Auvelity: Understanding the Link Between Auvelity and Depression Imagine waking up every day with a heavy cloud weighing down on your mind, making it difficult to find joy, motivation, or even the will to get out…

Understanding Bipolar Seizure Symptoms: A Comprehensive Guide

Imagine living with two conditions that can cause extreme mood swings and unpredictable seizures. It may sound overwhelming, but for individuals with both bipolar disorder and epilepsy, it is a reality they face every day. Bipolar…

Understanding the Relationship Between PMDD and BPD: Common Misdiagnosis as Bipolar Disorder

Do you ever feel like your emotions are on a rollercoaster, leaving you unsure of what to expect from one day to the next? If so, you may be familiar with the challenges of dealing with…

Living with a Bipolar Husband: Finding Support and Understanding in Forums

Living with a Bipolar Husband: Finding Support and Understanding in Forums Navigating the challenges of bipolar disorder within a relationship can be an emotional rollercoaster, both for the individual living with the condition and their partner….

Can Low Testosterone Cause Anxiety? Exploring the Link and Related Effects

Imagine waking up every day with a sense of unease, your heart racing and your mind clouded with worry. This state of perpetual anxiety can be both mentally and physically exhausting, making even the simplest tasks…

How Much Money Do You Get for Bipolar Disability: A Guide to Understanding Bipolar Disability Benefits

Living with bipolar disorder can be a challenging journey. The highs and lows, the constant battle with your own mind, and the impact it has on your daily life can leave you feeling exhausted. But did…

- Fundamentals of Bipolar Disorder

Fundamentals of Major Depressive Disorder

- Fundamentals of Schizophrenia

- Fundamentals Certificate Program

- Clinical Article Summaries

- Events Calendar

- Interactive Case Study

- Psychopharmacology

- Test Your Knowledge

- Psychiatric Scale NPsychlopedia

- Psychotherapy NPsychlopedia

- Caregiver Resources

- Educate Your Patient

- Quick Guides

- Clinical Insights

- NP Spotlight

- Peer Exchanges

Top results

Patient case navigator: major depressive disorder.

Introduction

Learning Objectives

- How to perform a structured psychiatric interview

- Standardized psychiatric rating scales appropriate for patients with depressive symptoms

- Common barriers to adequate treatment response

- How to assess and monitor patients for treatment side effects and adequate treatment response

Watch the video:

History and Examination

Medical History

Examination

History of Present Illness

Eric is a 60-year-old man who presents to his primary care nurse practitioner, Tina, with irritability, excessive sleeping, and a lack of interest in his usual hobbies, such as attending baseball games and going to the movies with his wife. He also has been spending much time at home alone, watching television, rather than spending time with his friends or wife, as he usually does. Eric recently retired from his job as a general contractor remodeling people’s kitchens and bathrooms. He enjoyed his job very much and felt a sense of pride in helping people make their homes more functional and attractive. However, his job was very physical, and at times stressful, so Eric felt it was time to retire and find something new with which to occupy his time.

Eric was diagnosed with hypothyroidism 5 years ago and has been on medication ever since. Annual lab tests indicate his thyroid levels have remained within the normal range for the past few years. He also has mild hypertension, which is well-controlled at an adequate dose.

Psychosocial History

Eric reports that he has several close friends and that he got along well with people at work. He denies a history of substance misuse and reports that he occasionally drinks a glass of wine with dinner. He does not smoke. Eric describes his marriage as “very good.” He is also close with his adult daughter and enjoys spending time with his 2 grandchildren.

At age 33, Eric experienced a period of depressed mood after losing his job. During that time, he had problems getting out of bed in the morning because he felt hopeless and sad, stopped socializing with friends, and lost about 4 lbs of body weight in 4 weeks without intentionally dieting. He sought treatment from his primary care physician, who referred him to a psychiatrist for medication and a psychologist for outpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Eric worked with his psychiatrist and tried 4 different selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) before he ultimately found one that seemed to work for him. He and his psychiatrist decided together that he could stop taking the medication after 1 year because his mood had improved and stabilized. He saw his therapist once weekly for approximately 2.5 years and reports that CBT also helped improve his mood and functioning.

Family History

Eric reports that, throughout his life, his mother had “very low periods” when she seemed extremely sad and had trouble functioning. However, she never sought treatment for these episodes.

Eric’s physical examination indicates he is generally healthy for his age. His vital signs are all within the normal range, and the mental status examination indicates he is fully oriented and alert. Eric’s appearance is that of an older man. His affect is flat, and he has trouble making eye contact, often staring at the floor instead.

Patient Interview

Quiz #1: initial presentation and diagnosis, dsm-5 diagnostic criteria for mdd.

MDE Diagnostic Criteria

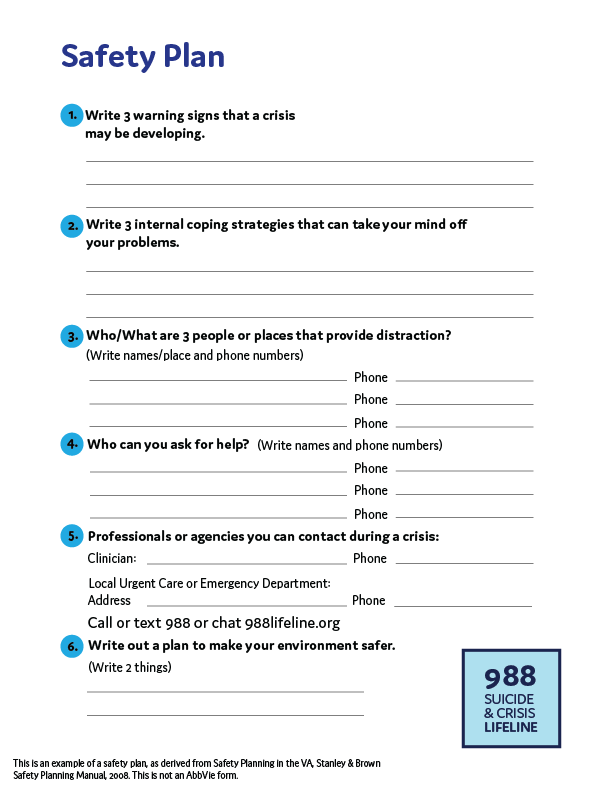

Safety Plan

Major Depressive Episode (MDE)

A. Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous function; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report or observation made by others

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day

- Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain, or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day

- Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day

- Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day

- Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide

B. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of function

C. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- It is important to thoroughly review each of these 9 symptoms with your patients when assessing them for MDD.

- Clinical rating scales can help identify which patients require more in-depth screening for depression.

Quiz #2: DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for MDD

Scales for mdd.

PHQ-9 Scale Scoring

QIDS Scale Scoring

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? (Use "✓" to indicate your answer) | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3. Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4. Feeling tired or having little energy | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5. Poor appetite or overeating | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6. Feeling bad about yourself - or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7. Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8. Moving or speaking slowly that other people could have noticed? Or the opposite - being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more that usual | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 9. Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| For Office Coding: | 0 | + | + | + |

| = | Total Score: | _____ |

| If you checked off any problems, how difficult have those problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not difficult at all | Somewhat difficult | Very difficult | Extremely difficult |

This scale was developed by Drs Robert L. Spitzer, Janet B.W. Williams, Kurt Kroenke, and colleagues with an educational grant from Pfizer inc. No permission required.

Scoring Criteria

| 0-4 | No depression |

| 5-9 | Mild depression |

| 10-14 | Moderate depression |

| 15-19 | Moderately severe depression |

| 20-27 | Severe depression |

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:509-521.

The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS)

- The QIDS is a 16-item, multiple-choice questionnaire in which depressive symptoms are rated on a 0-3 scale according to severity

- Items are derived from the 9 diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder used in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV), including sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, poor concentration or decision-making, self-outlook, suicidal ideation, lack of energy, sleep disturbance, appetite change, and psychomotor agitation

- Although the QIDS was initially developed based on DSM-IV criteria, the scale is also compatible with the DSM-5. The core criteria for MDD are consistent across these editions

Rush AJ, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573-583.

| 0-5 | Normal |

| 6-10 | Mild |

| 11-15 | Moderate |

| 16-20 | Severe |

| ≥ 21 | Very Severe |

Bernstein IH, et al. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(2):138-146.

Quiz #3: Scales for MDD

Treatment initiation and monitoring.

APA Guidelines

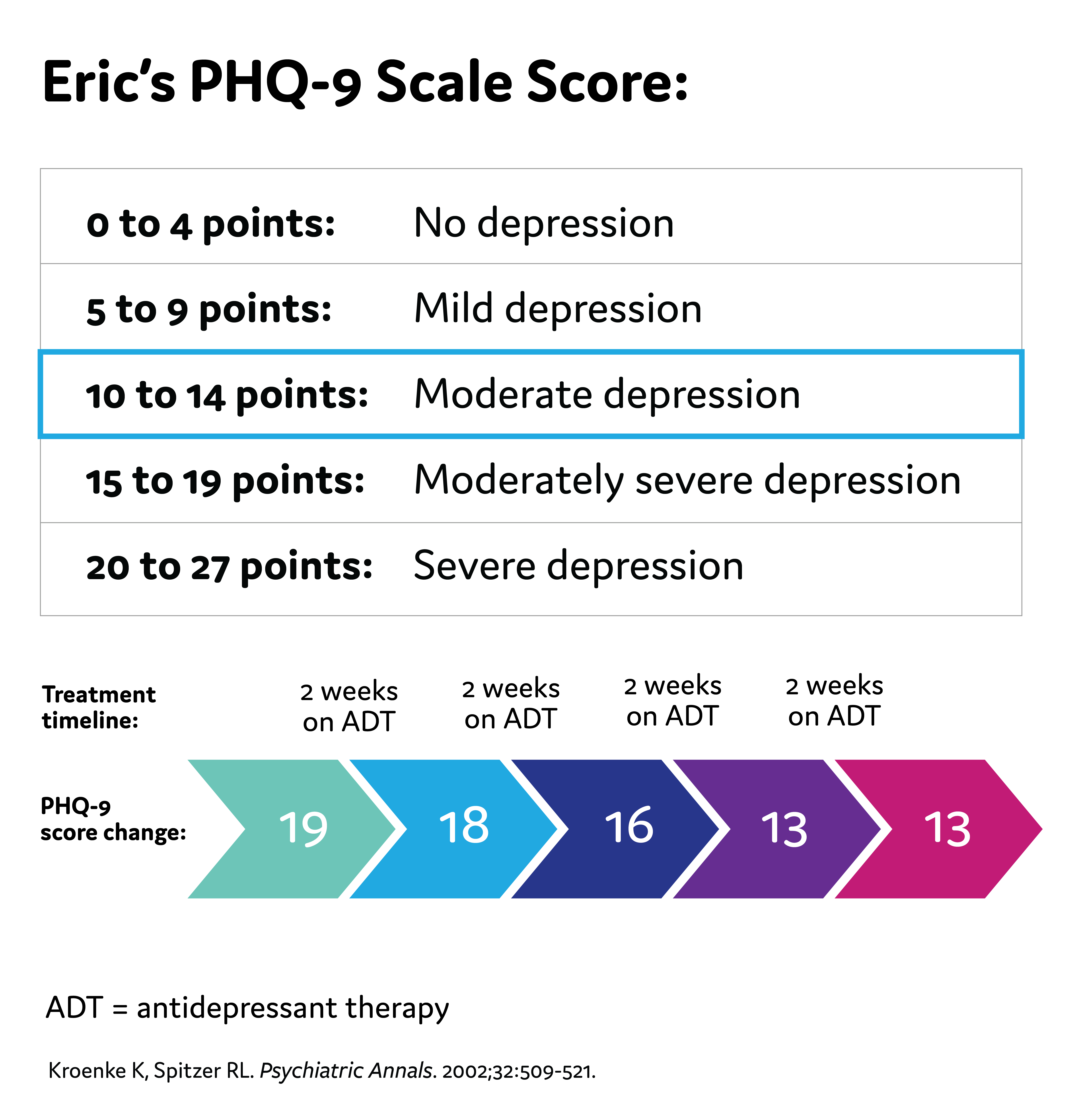

Eric's PHQ-9 Score

Treatment Options

American Psychiatric Association (APA) Guidelines for Treatment of MDD

1-2 weeks: Improvement from pharmacologic therapy can be seen as early as 1-2 weeks after starting treatment

2-4 weeks: Some patients may achieve improvement in 2-4 weeks

4-6 weeks: Short-term efficacy trials show antidepressant therapy appears to require 4-6 weeks to achieve maximum therapeutic effects

4-8 weeks: The APA recommends 4-8 weeks of adequate* treatment is needed before concluding that a patient is partially responsive or unresponsive to treatment *Adequate dose and duration Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

*Adequate dose and duration

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

Quiz #4: Treatment Initiation and Monitoring

Assessing for treatment challenges.

Treatment Challenges

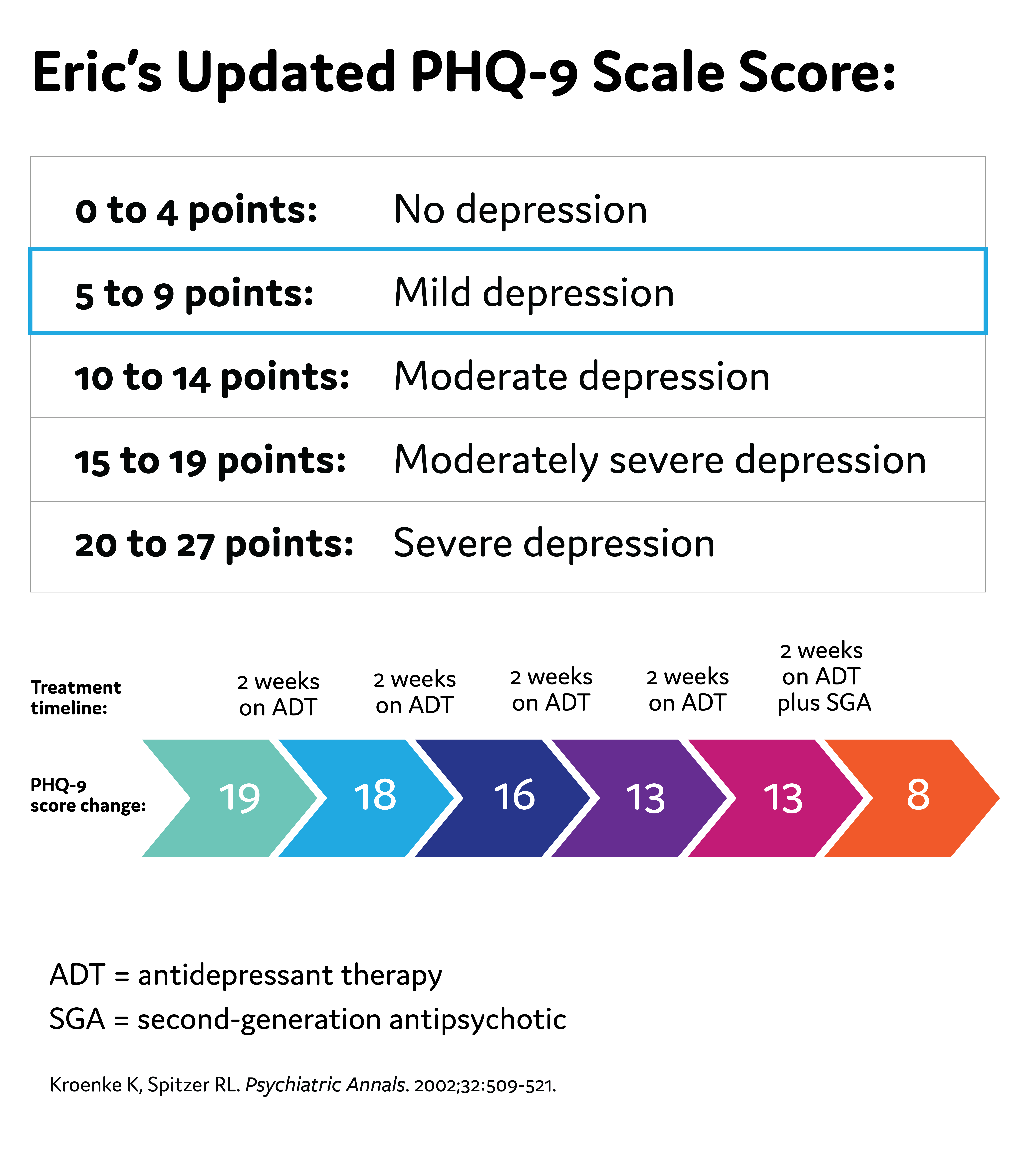

Eric's Updated PHQ-9 Score

Possible Challenges to Antidepressant Therapy

- Suboptimal efficacy due to the wrong dose, inadequate length of time on the medication, or the person's individual biology not being responsive to the medication

- Unpleasant side effects of antidepressants can occur, such as weight gain, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction

- Nonadherence to the antidepressant

- As a reminder, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends 4-8 weeks of adequate* treatment is needed before concluding that a patient is partially responsive or unresponsive to treatment

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

MDD Diagnosis

Clinical Probes

Treatment Assessment

Monitoring Considerations

Factors to Consider When Making a MDD Diagnosis

- Take a thorough patient history

- Previous or current depressive episodes

- Previous or current manic or hypomanic episodes

- Family history of MDD, bipolar disorder

- Medical comorbidities

- Consider a broad differential diagnosis

Clinical Queries That Aid in Diagnosing Major Depressive Episodes

| DSM-5 Criteria | Clinical Queries |

|---|---|

| 1. Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day | 1. Have you been experiencing persistent feelings of low mood, sadness, or hopelessness? |

| 2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities most of the day, nearly every day | 2. Have you noticed a decrease in interest or pleasure in activities that you once enjoyed? |

| 3. Significant change in weight or appetite | 3. Have your eating habits changed, either with a decrease or increase in appetite? |

| 4. Insomnia or hypersomnia | 4. Have you noticed and changes in your sleep patterns? |

| 5. Psychomotor agitation or retardation | 5. Have you felt unusually restless or fidgety, or slower than usual in your movements or speech? |

| 6. Fatigue or loss of energy | 6. Have you been feeling more tired and consistently low on energy? |

| 7. Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt | 7. Have you been struggling with feelings of low self-worth? |

| 8. Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness | 8. Are you finding it difficult to concentrate or think clearly? |

| 9. Recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation | 9. Have you been having thoughts about death or harming yourself? |

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 2. Kroenke K, et al. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

APA Practice Guidelines on Treatment Assessment

- Wait 4 to 8 weeks to assess treatment response to antidepressants

- In patients without adequate response, clinicians can consider changing or augmenting with a second medication

- Changes to treatment plans, such as augmenting with a second-generation antipsychotic medication, are reasonable if a patient does not have adequate improvement in 6 weeks

- Consistently follow-up with patients to assess treatment effects, adverse medication effects, and risk of self-harm

APA Practice Guidelines note that the frequency of monitoring should be based on:

- Symptom severity (including suicidal ideation)

- Co-occurring disorders (including general medical conditions)

- Treatment adherence

- Availability of social supports

- Frequency and severity of side effects with medication

Tina Matthews-Hayes is a paid consultant for Abbvie Medical Affairs and was compensated for her time.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Kapfhammer HP. Somatic symptoms in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2006;8(2):227-239.

- Bobo WV. The diagnosis and management of bipolar I and II disorders: clinical practice update. Mayo Clin Proc . 2017;92(10):1532-1551.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med . 2001;16:606-613.

- Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms. Arthritis Care Res . 2011;63(S11):S454-S466. doi:10.1002/acr.20556

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), Clinician Rating (QIDS-C), and Self-Report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573-583.

- Brown ES, Murray M, Carmody TJ, et al. The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-report: a psychometric evaluation in patients with asthma and major depressive disorder. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(5):433-438. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60467-X

- Liu R, Wang F, Liu S, et al. Reliability and validity of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Report Scale in older adults with depressive symptoms. Front Psychiatry . 2021;12:686711. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.686711

- Bernstein IH, Rush AJ, Suppes T, et al. A psychometric evaluation of the clinician-rated Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-C16) in patients with bipolar disorder. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res . 2009;18(2):138-146. doi:10.1002/mpr.2855

- Bernstein IH, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Psychometric properties of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology in adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(4):185-194. doi:10.1002/mpr.321

- Kroenke K. Enhancing the clinical utility of depression screening. CMAJ . 2012;184(3):281-282.doi:10.1503/cmaj.112004

- Levinstein MR, Samuels BA. Mechanisms underlying the antidepressant response and treatment resistance. Front Behav Neurosci . 2014;8:208. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00208

- Haddad PM, Talbot PS, Anderson IM, McAllister-Williams RH. Managing inadequate antidepressant response in depressive illness. Br Med Bull. 2015;115(1):183-201. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldv03

This resource is intended for educational purposes only and is intended for US healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals should use independent medical judgment. All decisions regarding patient care must be handled by a healthcare professional and be made based on the unique needs of each patient.

This is not a diagnostic tool and is not intended to replace a clinical evaluation by a healthcare provider.

Reach out to your family or friends for help if you have thoughts of harming yourself or others, or call the National Suicide Prevention Helpline for information at 800-273-8255.

ABBV-US-00976-MC, V1.0 Approved 12/2023 AbbVie Medical Affairs

Recommended on NP Psych Navigator

Disease Primer

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most recognized mental disorders in the United States. Learn more about the prevalence, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of MDD here.

Clinical Article

State-Dependent Differences in Emotion Regulation Between Unmedicated Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder

Rive et al use functional MRI to look at some of the differences between patients with bipolar depression and major depressive disorder.

Unrecognized Bipolar Disorder in Patients With Depression Managed in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Daveney et al explore the characteristics of patients with mixed symptoms, as compared to those without mixed symptoms, in both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.

Welcome To NP Psych Navigator

This website is intended for healthcare professionals inside the United States. Please confirm that you are a healthcare professional inside the US.

You are now leaving NP Psych Navigator

Links to sites outside of NP Psych Navigator are provided as a resource to the viewer. AbbVie Inc accepts no responsibility for the content of non-AbbVie linked sites.

Redirect to:

- myCME Login

- Monthly CME eNewsletter

Live Events

Text-based cme, journal cme, self-study cme, major depressive disorder, brian barnett, md jeremy weleff, do, case report.

A 24-year-old female presents to the outpatient clinic with abdominal pain. She describes vague symptoms of gastrointestinal distress. A physical examination reveals no emergent clinical signs.

In talking with her, the patient suddenly becomes tearful. She reports sadness for the last month, inability to experience pleasure, and trouble staying asleep at night. She is notably fatigued, lacks appetite, and skipped work multiple times in the last week, which is unusual for her. She ended a long-term romantic relationship during this period and notes that, “no one would want to be with me anyway.” She denies alcohol or drug use. She denies suicidal thoughts but notes that she is thinking more about death lately and increasingly feels that life may not be worth living.

Her only medication is an oral contraceptive pill. Past medical evaluations that included basic lab tests have shown no abnormalities.

What is the most likely clinical diagnosis?

- Hypothyroidism

- Alcohol use disorder

- Adjustment disorder with depressed mood

- Personality disorder

- Major depressive disorder

Correct! Answer:

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common psychiatric illnesses and a common diagnosis in primary care clinics. Point prevalence of depression ranges around 5% (with considerable variation among countries), and it commonly ranks among the top conditions and causes considerable burden of disease. 1 Despite this, the rates of correct recognition of depression in primary care are only around 47%, with even fewer patients receiving adequate treatment or reaching remission. 2,3

The patient in this scenario meets at least six of the criteria for MDD — depressed mood, anhedonia, insomnia, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, and recurrent thoughts of death. Importantly, during the past 2 weeks, she has at least one of the core diagnostic symptoms: depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure (anhedonia). Symptoms should also cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning and not be caused by another psychiatric disorder. The full diagnostic criteria for MDD are listed on Table 1. 4

Another important diagnostic consideration is that the episode should not be attributable to the physiological effects of substance use or another medical condition. A complete medical workup for common mimics of depression and ruling out concurrent alcohol or drug use is key to diagnostic precision. Alcohol and drug use and withdrawal syndromes can mimic symptoms of depression, and treatment for these conditions requires much different steps than the treatment of MDD. The patient in this scenario didn’t present with any concerns for these diagnostic considerations. Because the patient meets criteria for a major depressive disorder, this cannot be classified as an adjustment disorder, which is milder.

| A. | Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least 1 of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Which of the following best describes risk factor(s) for the development of MDD?

There are several risk factors for depression to consider when gathering clinical evidence to support (or suggest against) a diagnosis of MDD (Table 2). 4 A family history of depression in first-degree family members is thought to increase risk of MDD by 2- to 4-fold 5 and should always be obtained during the initial assessment of a patient with concerns of depression. Trauma and adverse childhood events are thought to be linked to increased incidence of many psychiatric illnesses, and they cause an earlier age of symptom onset, increased symptom severity, and worsened treatment responses in MDD. 6,7

What is another component of the patient’s history that should always be assessed during an initial clinical encounter for depression?

As always, diagnostic precision is a key to appropriate treatment and improved outcomes in depression care. Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder I/II comes with considerable risk as rates of suicide with bipolar disorder are possibly 15 times greater than baseline, and suicide is one of the leading causes of death in this population. Clinical overlap between MDD and bipolar disorder is significant, as 90% of patients with a history of mania/bipolar I go on to have recurrent mood episodes. Approximately 60% of manic episodes occur before a major depressive episode, making questions about manic episodes a valuable tool for accurate diagnosis. In addition, the first-line treatments of bipolar depression are mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics rather than classic antidepressants. 4,8 A family history of bipolar disorder is thought to lead to an average 10-fold increased risk among adult relatives of individuals with bipolar disorders, making it one of the largest risk factors. Mania or hypomania that emerges during antidepressant treatment (eg, psychotropic medication, electroconvulsive therapy) should raise strong and immediate concern for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder rather than MDD. Traditionally, the introduction of antidepressants — first noticed with older tricyclic antidepressants and later with other classes such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors — in someone with bipolar disorder could precipitate mania. Although that remains an important treatment consideration, the incidence of this occurrence and the possible neurobiological causes is not clear. Mania is a psychiatric emergency that requires immediate psychiatric consultation and/or psychiatric admission. Patients who are manic often do not perceive that they are ill and will sometimes engage in uncharacteristically dangerous behaviors that can lead to interactions with police or other problems with serious potential for harm (eg, gambling, serious financial difficulties, physical assaults, suicide). Prominent delusions or psychotic symptoms can also put these patients at risk of harming themselves or others. The following define mania/hypomania:

An episode should not be attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (eg, drug of abuse, medication, other treatment) or another medical condition. By definition, during the period of mood disturbance and increased energy or activity, three (or more) of the following symptoms (four if the mood is only irritable) are present to a significant degree and represent a noticeable change from usual behavior:

For mania, the mood disturbance is sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning, or to necessitate hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, or if there are psychotic features. For hypomania, the episode is associated with an unequivocal change in functioning that is uncharacteristic of the individual when not symptomatic, but it does not cause marked impairment in functioning or lead to psychiatric admission. If the presence of psychotic features during hypomania emerges, then the diagnosis is then changed to mania (and subsequently bipolar I). Which of the following conditions should be on the differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with concerns about depression?

Many conditions can resemble MDD, so one should be attentive to its broad differential when considering MDD as a diagnosis. 4,9,10 Alcohol and many illicit substances can cause substance induced mood disorders, so screening patients for substance use is an important part of the workup. Additionally, some medications such as barbiturates, vigabatrin, topiramate, flunarizine, corticosteroids, mefloquine, efavirenz, and interferon-alpha can cause depression. Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a condition that occurs in response to an identifiable stressor within 3 months of the stressor’s onset. Adjustment disorder is characterized by marked distress that is out of proportion to the severity or intensity of the stressor and causes significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Adjustment disorder does not persist for more than 6 months after a stressor or its consequences terminate. If a patient develops enough symptoms to meet the criteria for MDD, they cannot be diagnosed with an adjustment disorder because the MDD diagnosis takes precedence. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) causes problems with concentration that can be similar to those produced by depression. ADHD is frequently misdiagnosed in people who have MDD. If a patient mentions attention problems, it is important to screen for ADHD as well as depression. Finally, the experience of sadness by itself does not constitute a psychiatric condition. It is only in the context of other symptoms recognized as part of MDD, along with impairment in function, that sadness becomes part of a psychiatric condition that should be treated. What is the first treatment step for mild MDD?

First-line treatments for individuals with mild depression include psychoeducation, self-management, and psychological treatments. Pharmacological treatments can be considered for mild depression in some situations, such as patient preference, previous improvement with antidepressants, or lack of response to other nonpharmacological interventions. 9,11 Assessment of severity and monitoring treatment response in depression care should incorporate the use of measurement-based outcomes (clinician-administered or patient-reported scales such as PHQ-9). The severity of MDD is determined by number of symptoms, symptom severity, depression scores on assessment tools, or by the practitioner’s clinical judgment of patient functioning. Of the following, which is the most appropriate first-line pharmacological treatment for moderate to severe MDD?

Table 3 shows the commonly used medications for first- and second-line treatment of moderate to severe MDD. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are generally well-tolerated, which makes them the preferred first-line treatment for moderate to severe depression. 9,11 It should be noted that most patients will require an increase in dose or a change in medication. This is best exemplified by the remission rates found in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, which were only 36.8% for the first treatment. 12 Thus, it is important for the practitioner to bring the patient to an adequate treatment dose before giving up on a medication. Common pitfalls in initiating treatment for MDD are inadequate dose adjustments, inadequate duration of medication trial (prescribe for at least 3 months at therapeutic dose), and diagnostic errors. There are a few additional considerations to make if there is suspicion for MDD with a specifier or other prominent clinical symptoms. These include the following:

Table 3: Commonly used first- and second-line pharmacological treatment of moderate and severe depression with treatment dose range.

NDRI = norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitor; SNRIs = serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors A patient with MDD presents with positive suicidal ideation, what is the next step in care?

Patients with MDD are at increased risk of completing suicide or engaging in other suicidal behavior. Patients with depression, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and anorexia nervosa generally have the highest suicide risks. 13 There are many critical clinical steps to mitigate the risks for completing suicide and many standardized clinical assessment tools that can aid in determining risk and identifying modifiable risk factors. 14-17

While there is ongoing debate about how accurate these tools are in predicting suicide, clinically their importance remains paramount, and their use is recommended by the U.S. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. 18 Using a standardized tool helps to identify important modifiable risk factors for suicide and to complete suicide risk documentation. Complete documentation of a risk assessment, as well as the steps that were taken to reduce risk, are key components of good clinical care and reducing liability risk. 19

Assessment of the nature of suicidal ideation — frequency, intensity, and characteristics of thoughts — as well as the presence of any planning or intent to suicide are the first steps. Suicide planning and intent generally require emergent psychiatric inpatient stabilization. Removing access to lethal means, treating underlying psychiatric disorders, and abstaining from alcohol and drug use are the three primary clinical targets in modifying suicide risk. In monitoring treatment response in depression, what is the definition of remission?

It is expected that symptom abatement should occur, generally, within the first 3 months of treatment with pharmacologic or psychological interventions. If the patient has an improvement in symptoms after 2 to 4 weeks, then treatment should continue for another 6 to 8 weeks. If the patient has remission of symptoms at that time, then the duration of antidepressant treatment is guided by the presence of risk factors for recurrence. If the patients has risk factors, then treatment should generally continue for 2 years or longer. Without risk factors, treatment should continue for approximately 6 to 9 months. Risk factors for recurrence that prompt longer antidepressant treatment include the following:

Other factors that contribute to lower rates of remission or recovery include multiple depressive episodes, younger age, episode severity, co-occurring personality disorders, presence of psychotic features, and prominent anxiety. The longer someone remains in remission, the lower the chances of recurrence. 9,11 Monitoring treatment response in depression should incorporate the use of clinician-administered or patient-reported scales. Assessment of symptom severity, severity scores, as well as functional improvement should be incorporated into routine clinical care. There are multiple well-validated scales to choose from and some examples are listed below. These scales provide quantification of symptoms and can be used to provide longitudinal comparison and evaluation of treatment. Many are quick to use in office and have become routine screening or severity tools in both clinical practice and research. Well-validated scales for monitoring treatment response in patients with depression include the following:

Which of the following is/are first- or second-line psychological treatment(s) for MDD?

All four of these psychological treatments are appropriate for managing a patient with MDD. 9,20 Table 4 shows their best use in clinical practice. Table 4. Common first and second line psychological treatments for MDD.

For a patient requesting the use of “alternative” or “complementary” treatment for their depression, which of the following treatments have sufficient evidence to be recommendation as first-line therapy for some forms of depression?

There are several alternative and complementary treatments that have evidence for use as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy for the treatment of MDD (Table 5).21 Although there is evidence that some of these can be used as monotherapy for mild depression, for moderate or severe depression these should generally only be used an adjunctive treatment to other well-established treatments. Table 5. First-line and adjunctive alternative and complementary treatments for MDD.

It should be noted that unless there is a specific patient request for alternative or complementary treatment options, or other contraindications to well-established antidepressant treatment, these should not be used or offered as initial treatment for moderate to severe depression or where other clinically significant symptoms (eg, suicidal ideation, severe impairment) are present. Providers should be reminded that various forms of psychotherapy are available to those patients that may have contraindications to standard antidepressant therapy and that they should utilize consultation to psychiatry if treatment complications, nonresponse to medication trials, and other questions occur.

That answer is incorrect. Please try again. Rowan Digital Works

Home > ETD > 958 Theses and DissertationsCase study of a client diagnosed with major depressive disorder. Barbara Ann Marie Allison , Rowan University Date ApprovedEmbargo period, document type, degree name. M.A. in Applied Psychology College of Science & Mathematics Cahill, Janet Depressed persons--Case studies; Depression, Mental--Diagnosis

The purpose of this study was to determine the best practice for a client diagnosed with major depressive disorder who was referred for treatment at a community mental health facility. The client was assessed, diagnosed, and a treatment plan was developed. Implemented treatment consisted of combined cognitive behavioral oriented psychotherapy and psychotropic medication. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) was used to assess changes in depressive symptoms. Results indicated a significant decline in depressive symptoms over the course of treatment. At the onset of treatment, the client's BDI scores were in the clinically depressed range, while at the conclusion of treatment they had decreased to the borderline range. The client self-reported an improvement in mood. A comparison between the client's current treatment and what might be considered "best" treatment is presented. Suggestions for treatment improvements are made, with a particular emphasis on concerns regarding a potential relapse. Recommended CitationAllison, Barbara Ann Marie, "Case study of a client diagnosed with major depressive disorder" (2005). Theses and Dissertations . 958. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/958 Since April 10, 2016 Included inPsychology Commons  Advanced Search

Author Corner

ISSN 2689-0690 Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement Privacy Copyright Ohio State nav barThe Ohio State University