8 David Foster Wallace Essays You Can Read Online

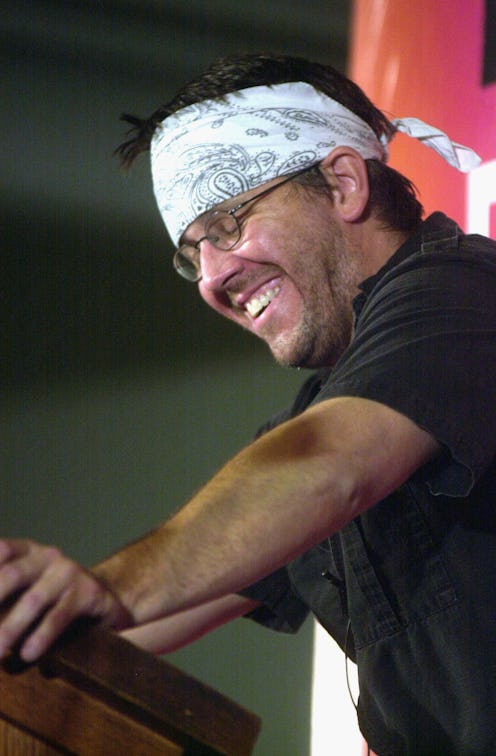

If you've talked to me for more than five minutes, you probably know that I'm a huge fan of author and essayist David Foster Wallace . In my opinion, he's one of the most fascinating writers and thinkers that has ever lived, and he possessed an almost supernatural ability to articulate the human experience.

Listen, you don't have to be a pretentious white dude to fall for DFW. I know that stigma is out there, but it's just not true. David Foster Wallace's writing will appeal to anyone who likes to think deeply about the human experience. He really likes to dig into the meat of a moment — from describing state fair roller coaster rides to examining the mind of a detoxing addict. His explorations of the human consciousness are incredibly astute, and I've always felt as thought DFW was actually mapping out my own consciousness.

Contrary to what some may think, the way to become a DFW fan is not to immediately read Infinite Jest . I love Infinite Jest. It's one of my favorite books of all-time. But it is also over 1,000 pages long and extremely difficult to read. It took me seven months to read it for the first time. That's a lot to ask of yourself as a reader.

My recommendation is to start with David Foster Wallace's essays . They are pure gold. I discovered DFW when I was in college, and I would spend hours skiving off my homework to read anything I could get my hands on. Most of what I read I got for free on the Internet.

So, here's your guide to David Foster Wallace on the web. Once you've blown through these, pick up a copy of Consider the Lobster or A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again .

1. "This is Water" Commencement Speech

Technically this is a speech, but it will seriously revolutionize the way you think about the world and how you interact with it. You can listen to Wallace deliver it at Kenyon College , or you can read this transcript . Or, hey, do both.

2. "Consider the Lobster"

This is a classic. When he goes to the Maine Lobster Festival to do a report for Gourmet , DFW ends up taking his readers along for a deep, cerebral ride. Asking questions like "Do lobsters feel pain?" Wallace turns the whole celebration into a profound breakdown on the meaning of consciousness. (Don't forget to read the footnotes!)

2. "Ticket to the Fair"

Another episode of Wallace turning journalism into something more. Harper 's sent DFW to report on the state fair, and he emerged with this masterpiece. The Harper's subtitle says it all: "Wherein our reporter gorges himself on corn dogs, gapes at terrifying rides, savors the odor of pigs, exchanges unpleasantries with tattooed carnies, and admires the loveliness of cows."

3. "Federer as Religious Experience"

DFW was obviously obsessed with tennis, but you don't have to like or know anything about the sport to be drawn in by his writing. In this essay, originally published in the sports section of The New York Times , Wallace delivers a profile on Roger Federer that soon turns into a discussion of beauty with regard to athleticism. It's hypnotizing to read.

4. "Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise"

Later published as "A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again" in the collection of the same name, this essay is the result of Harper's sending Wallace on a luxury cruise. Wallace describes how the cruise sends him into a depressive spiral, detailing the oddities that make up the strange atmosphere of an environment designed for ultimate "fun."

5. "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction"

This is definitely in the running for my favorite DFW essay. (It's so hard to choose.) Fiction writers! Television! Voyeurism! Loneliness! Basically everything I love comes together in this piece as Wallace dives into a deep exploration of how humans find ways to look at each other. Though it's a little long, it's endlessly fascinating.

6. "String Theory"

"You are invited to try to imagine what it would be like to be among the hundred best in the world at something. At anything. I have tried to imagine; it's hard."

Originally published in Esquire , this article takes you deep into the intricate world of professional tennis. Wallace uses tennis (and specifically tennis player Michael Joyce) as a vehicle to explore the ideas of success, identity, and what it means to be a professional athlete.

7. "9/11: The View from the Midwest"

Written in the days following 9/11, this article details DFW and his community's struggle to come to terms with the attack.

8. "Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage "

If you're a language nerd like me, you'll really dig this one. A self-proclaimed "snoot" about grammar, Wallace dives into the world of dictionaries, exploring all of the implications of how language is used, how we understand and define grammar, and how the "Democratic Spirit" fits into the tumultuous realms of English.

Images: cocoparisienne /Pixabay; werner22brigette /Pixabay; StartupStockPhotos /Pixabay; PublicDomainPIctures /Pixabay

December 28, 2017

Best Article Movies & TV

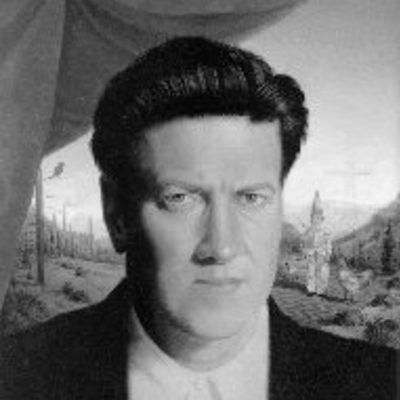

David Lynch Keeps His Head

A visit to the set of Lost Highway , minus an actual interview with the director.

David Foster Wallace Premiere Sep 1996 45 min Permalink

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, david foster wallace on david lynch.

The apparent suicide of David Foster Wallace, shockingly sad and disturbing as the sudden death of Heath Ledger earlier this year, has me revisiting my memories of his writing. I know him from his short stories and nonfiction -- never tackled " Infinite Jest ," even though I bought it in hardback when it was first published. I won't put off reading it much longer.

From Premiere magazine, September, 1996: " David Lynch Keeps His Head," anthologized in " A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments ":

13. WHAT EXACTLY DAVID LYNCH SEEMS TO WANT FROM YOU MOVIES ARE AN authoritarian medium. They vulnerabilize you and then dominate you. Part of the magic of going to a movie is surrendering to it, letting it dominate you....

...The sitting in the dark, the looking up, the tranced distance from the screen, the being able to see the people on the screen without being seen by the people on the screen, the people on the screen being so much bigger than you: prettier than you, more compelling than you, etc. Film's overwhelming power isn't news. But different kinds of movies use this power in different ways. Art film is essentially teleological; it tries in various ways to "wake the audience up" or render us more "conscious." (This kind of agenda can easily degenerate into pretentiousness and self-righteousness and condescending horsetwaddle, but the agenda itself is large-hearted and fine.) Commercial film doesn't seem like it cares much about the audience's instruction or enlightenment. Commercial film's goal is to "entertain," which usually means enabling various fantasies that allow the moviegoer to pretend he's somebody else and that life is somehow bigger and more coherent and more compelling and attractive and in general just way more entertaining than a moviegoer's life really is. You could say that a commercial movie doesn't try to wake people up but rather to make their sleep so comfortable and their dreams so pleasant that they will fork over money to experience it -- the fantasy-for-money transaction is a commercial movie's basic point. An art film's point is usually more intellectual or aesthetic, and you usually have to do some interpretative work to get it, so that when you pay to see an art film you're actually paying to work (whereas the only work you have to do w/r/t most commercial film is whatever work you did to afford the price of the ticket). David Lynch's movies are often described as occupying a kind of middle ground between art film and commercial film. But what they really occupy is a whole third kind of territory. Most of Lynch's best films don't really have much of a point, and in lots of ways they seem to resist the film-interpretative process by which movies' (certainly avant-garde movies') central points are understood. [...] You almost never from a Lynch movie get the sense that the point is to "entertain" you, and never that the point is to get you to fork over money to see it. This is one of the unsettling things about a Lynch movie: You don't feel like you're entering into any of the standard unspoken and/or unconscious contracts you normally enter into with other kinds of movies. This is unsettling because in the absence of such an unconscious contract we lose some of the psychic protections we normally (and necessarily) bring to bear on a medium as powerful as film. That is, if we know on some level what a movie wants from us, we can erect certain internal defenses that let us choose how much of ourselves we give away to it. The absence of point or recognizable agenda in Lynch's films, though, strips these subliminal defenses and lets Lynch get inside your head in a way movies normally don't. This is why his best films' effects are often so emotional and nightmarish. (We're defenseless in our dreams too.) This may in fact be Lynch's true and only agenda - just to get inside your head. He seems to care more about penetrating your head than about what he does once he's in there. Is this good art? It's hard to say. It seems - once again - either ingenuous or psychopathic. It sure is different, anyway. 13(A). WHY THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF WHAT LYNCH WANTS FROM YOU MIGHT BE A GOOD THING IF YOU THINK about the outrageous kinds of moral manipulation we suffer at the hands of most contemporary directors²³, it will be easier to convince you that something in Lynch's own clinically detached filmmaking is not only refreshing but redemptive. It's not that Lynch is somehow "above" being manipulative; it's more like he's just not interested. Lynch's movies are about images and stories that are in his head and that he wants to see made external and complexly "real." His loyalties are fierce and passionate and entirely to himself. [...] - - - 23 Wholly random examples: Think of the way " Mississippi Burning " fumbled at our consciences like a freshman at a coed's brassiere, or of " Dances with Wolves " crude smug reversal of old westerns' 'White equals good and Indian equals bad' equation. Or just think of movies like " Fatal Attraction " and " Unlawful Entry " and "Die Hards" I through III and " Copycat ," etc., in which we're so relentlessly set up to approve the villains' bloody punishment in the climax that we might as well be wearing togas. - - -

I wonder what David Foster Wallace would say about these passages from his assessment of Lynch today. Or, more precisely, last week, when he still could have. I love his wry, perceptive take on the difference between "art films" and "commercial movies," and I appreciate what he says about Lynch even as I'd like to know more about the language he uses.

I used to describe Lynch similarly, as someone who tries to put what's in his head directly onto the screen with as little mediation as possible. (In that sense, he's a Surrealist.) But as " Mulholland Dr. " (2001) and " Inland Empire " make abundantly clear (and this is probably the only thing they make abundantly clear -- which I mean as a compliment), he doesn't necessarily know what's in his head before he's finished creating the movie. He says he dreamed the ending of "Mullholland Dr." after the network turned it down as a TV pilot. And he celebrated the freedom of using low-definition video for "Inland Empire" because he said it allowed him to go deeper inside the scenes with the actors -- while they were happening -- and to discover more than he had imagined.

That sense of discovery is, I think, particularly apparent in "Mullholland Dr." and " Inland Empire " (and "Eraserhead"), and what helps make them his most rewarding and challenging movies -- and " Twin Peaks " his greatest achievement. Too much of " Blue Velvet " felt to me like it was not so much "manipulative" as pre-programmed, and its occasional reassuring winks to the audience too much like comic-relief cliches -- as if Lynch were hedging his bets, hinting that he wasn't entirely serious even if (I hope) he was.

At this moment, however, I am appreciating Lynch through Wallace's eyes. Read this 1996 Lynch piece alongside the 2005 commencement speech I quoted from below , and you can get some idea of why Lynch's definition-resisting films spoke to him so profoundly.

Latest blog posts

Cannes 2024: Ghost Trail, Block Pass

At the Movies, It’s Hard Out There for a Hit Man

Far, Far Away: How to Get People Going to Movies Again

Cannes 2024: Christmas Eve in Miller's Point, Eephus, To A Land Unknown

Latest reviews.

The Dead Don't Hurt

Matt zoller seitz.

Young Woman and the Sea

Christy lemire.

Brian Tallerico

What You Wish For

Glenn kenny.

Robot Dreams

In a Violent Nature

Clint worthington.

- Death & Grief

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -32% $13.59 $ 13 . 59 FREE delivery Sunday, June 9 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select your preferred free shipping option

- Drop off and leave!

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $9.32 $ 9 . 32 FREE delivery June 15 - 20 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Krak Dogz Distribution

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments Paperback – February 2, 1998

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 368 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Back Bay Books

- Publication date February 2, 1998

- Dimensions 5.95 x 1 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0316925284

- ISBN-13 978-0316925280

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

About the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., a supposedly fun thing i'll never do again, back bay books.

1990 Continues... Excerpted from A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again by David Foster Wallace Copyright © 1998 by David Foster Wallace. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Product details

- Publisher : Back Bay Books; Reprint edition (February 2, 1998)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 368 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0316925284

- ISBN-13 : 978-0316925280

- Item Weight : 12.8 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.95 x 1 x 9.25 inches

- #51 in Essays (Books)

- #69 in Humor Essays (Books)

- #74 in Author Biographies

About the author

David foster wallace.

David Foster Wallace wrote the acclaimed novels Infinite Jest and The Broom of the System and the story collections Oblivion, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, and Girl With Curious Hair. His nonfiction includes the essay collections Consider the Lobster and A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again, and the full-length work Everything and More. He died in 2008.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Literature/Film Quarterly

“this muddy both ness”: the absorbed adaptation of david lynch by david foster wallace.

C harting the various influences on an artist is a tricky game, and in many ways a losing one: even if one succeeds at the difficult task of proving one artist’s influence on another, the question of what difference the influence makes persists. Discussions of influence run the gamut from being little more than a parlor game of spot-the-reference to diminishing the work of the influenced artist to something wholly derivative of the artist(s) who inspired it. The more open an artist is about their influences, the more critics tend to reference them in their discourse as well, which can limit scholarship to boundaries drawn by the artist themselves.

Two postmodern artists whose relationships to their various influences have received sustained critical attention are the filmmaker David Lynch and the novelist David Foster Wallace. Lynch’s work, despite being the product of a wholly original talent, is frequently discussed in terms of how it has been influenced by filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock and Billy Wilder, artists such as Francis Bacon and Salvador Dalí, and theorists such as Jacques Lacan and Laura Mulvey. 1 David Foster Wallace’s professional writing career essentially began with him fending off comparisons between his debut novel The Broom of the System and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 , and in interviews and essays Wallace himself would often consciously situate his fiction as a response to his literary and philosophical ancestors such as John Barth, Don DeLillo, Richard Rorty, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. 2 However, out of all the investigations into Lynch and Wallace and their influences, little sustained attention has been devoted to how their work might be related, even though Wallace openly and ardently acknowledges Lynch’s influence on him in his essay “David Lynch Keeps His Head.” 3

The abundance of academic work about Wallace’s many influences may make the need for another superfluous. However, as far-flung and farfetched as the works commonly accepted by scholars as influences on Wallace may be, they are all textual, verbal, printed matter. This fact is not surprising: Wallace is, after all, a writer deeply engaged with contemporary literature and one who published numerous essays and interviews discussing his place in literary history. But his work is also heavily concerned with visual culture, though when scholars speak of Wallace’s relationship to visual culture, they tend to echo Wallace’s derisive comments about television from his essay “ E Unibus Pluram : Television and U.S. Fiction.” This tendency to echo Wallace’s all-too-common disdain for lowest-common-denominator programming (rather than his praise of quality television programs such as Cheers , Hill Street Blues , and Twin Peaks ) obscures the extent to which one of the strongest influences on Wallace as an artist was not a literary figure but a visual one.

I submit that the similarities between David Lynch and David Foster Wallace are more than anecdotal and that ignoring Lynch’s influence on Wallace limits one’s understanding of Wallace’s work and themes. In fact, “influence” is too light a term for the degree to which Wallace absorbs Lynch’s work into his fiction. Wallace may never have formally adapted any of Lynch’s films into fiction, but I believe that it would be useful and illuminating to view many of his mature works of fiction as adaptations of Lynch’s style and themes that graft Lynch’s cinematic sensibility onto Wallace’s literary project. Examining Wallace’s fiction through the lens of adaptation studies shows how many of Wallace’s signature concerns and stylistic tropes originate in Lynch’s work. The grotesque figures, hideous men, and cycles of abuse and trauma intruding upon mundane slices of Americana that run throughout works such as Infinite Jest , Brief Interviews with Hideous Men , Oblivion , and The Pale King can be found earlier in Lynch’s work such as Blue Velvet , Twin Peaks , Lost Highway ,and Mulholland Drive . Lynch's work functions as a template for Wallace's fiction and suggests that Lynch may be the most important influence on Wallace as a commercial artist, most notably in the masterful ways in which Lynch smuggles avant-garde, experimental material into commercial entertainment. Wallace looked to Lynch as a role model for how an artist could create deeply personal, idiosyncratic work in the public eye without falling victim to the compromises brought on by self-consciousness or the market. In addition to reanimating the conversation around Wallace’s main themes, reading Wallace’s relationship to Lynch as adaptive in nature demonstrates the kind of open approach to adaptation studies that these artists find generative in and advocate for in their art. Perhaps, in looking at their relationship more closely, adaptation scholars will discover the same generative energy to explore the more subtle and organic ways that artists work with and adapt the raw material of another artist for their own creative purposes.

Absorbed Adaptation

Several adaptation theorists have laid the groundwork that makes my reading of Wallace adapting Lynch possible. John Bryant argues for viewing every creative text as fluid, part of “a cultural event transcending media” that is “both an individual and social process involving moments of solitary inspiration but also collaboration with readers” (47, 48). Bryant’s fluid text functions as a revision of a preexisting text and can be created by not only authors themselves and their publishers and editors but even by “readers and audiences, who reshape the originating work to reflect their own desires for the text, themselves, and their culture” (48). These “revising readers,” as Bryant calls them, “generate new versions of the text and thereby re-author the work, giving it new meaning in new contexts,” perhaps even expressing or defining the intentions of the source text’s author better than the author did themselves (48). The most useful aspect of approaching adaptation theory in this manner is that it “refuses to privilege the original source material over the reappearance” or seek to enforce a hierarchy of value among art forms that has made the adaptive dialogue Wallace engages in with Lynch invisible to critics (Luter 5). Wallace represents one of Bryant’s “revising readers” who “reshape[s]” David Lynch’s work to “generate new versions” of his sensibility in “new contexts,” thus allowing Lynch’s concerns to reappear in a new time and place for a new audience. Bryant defines this “symbiosis of writing and reading” as “adaptive revision”: Wallace appropriates Lynch via an intertextual form of “quotation, allusion, and plagiarism” that borrows heavily from Lynch’s work while still allowing his work and Lynch’s to maintain their “distinct textual identities” (49, 48, 50, 49). Wallace’s work is autonomous while simultaneously participating in and engaging with Lynch’s work on a dialogic, genetic level that runs deeper than mere inspiration. Adapting Lynch is not derivative but generative for Wallace: it transforms his career and proves critical to the development of his signature aesthetic. Wallace is not unique in this respect but rather emblematic of an adaptive mode that deserves further exploration. The work of filmmakers such as Jim Jarmusch ( Dead Man , Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai , and Paterson ) or authors such as Dana Spiotta ( Eat the Document and Innocents and Others ) and Steve Erickson ( Zeroville ) seem particularly ripe with potential for this kind of study. Matthew Luter insightfully examines DeLillo’s adaptation of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film Weekend (and DeLillo’s reworking of that material across several works) to show how his fiction engages with Godard’s politics and film style but also how, in the hands of DeLillo, “film-to-page adaptations and cinematic intertexuality are every bit as valid as more traditional literary techniques” (3). “The basic idea of Weekend in DeLillo doesn’t look so much like Weekend anymore,” Luter writes; rather, DeLillo’s adaptation confirms several arguments in adaptation theory: his adaptation of Godard (and his multiple reworkings of that adaptation) demonstrates that “no version of any text […] comes to be understood as its definitive rendering” (3). Likewise, the basic idea of David Lynch may not look as Lynchian in the fiction of David Foster Wallace, but Wallace’s imaginative adaptation of Lynch’s sensibility to his own acts as what Bryant would call a “liberation” for Wallace as a writer searching for an aesthetically authentic way to express himself (50).

A concept by Jonathan Rosenbaum captures what is at work in Wallace’s adaptation of Lynch more precisely than Bryant’s “fluid text” and Luter’s “film-to-page adaptation.” Rosenbaum compares David Cronenberg’s work adapting William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch to that of the Method actor. As Cronenberg does with Burroughs, Wallace adopts the Method actor’s “manner of working inside rather than outside” of his source text to create art that contains elements “recognizable” as Lynchian but “fully transformed” by Wallace (209, 217). For Rosenbaum, in this kind of adaptation, the adapted text does not evolve or grow out of its source but instead constitutes “an overlap and/or interface of these two personalities” (219). It is both an adaptation and a wholly original entity. He calls Cronenberg’s incorporation of “certain principles and texts from Burroughs into [his] particular cosmology and style” “absorption” (218). I would classify what Wallace does with Lynch’s work as an absorbed adaptation. Like Cronenberg, Wallace absorbs Lynch’s “cosmology and style” to create work; however, by not adapting Lynch directly, Wallace’s work surpasses Cronenberg’s absorbed adaptation of Burroughs in its originality and autonomy.

The Avant-Garde Ghost in the Commercial Machine

The significance of Lynch’s influence on Wallace is so plainly stated as to be easily underestimated: Wallace says that Lynch’s films “affected the way [he] see[s] and organize[s] the world” (Wallace, “David Lynch” 162). He even recalls the day he saw Blue Velvet : March 30, 1986 (200). At the time, Wallace was an MFA student in Arizona, where he and his peers were engaged in an aesthetic battle pitting their own “experimental” writing against the stodgy realism of their professors. According to Wallace, Blue Velvet demonstrated to him how flawed he was to believe realist and experimental work were mutually exclusive. As avant-garde and weird as Lynch’s style is, Blue Velvet remains grounded in realism and well-rounded characters, which allows Lynch to employ avant-garde techniques without seeming “solipsistic and pretentious and self-conscious and masturbatory and bad” but “true” to “the way the U.S. present acted on our nerve endings” (200, 201). The film for Wallace was “something crucial that couldn’t be analyzed or reduced to a system of codes or aesthetic principles or workshop techniques” (201). In essence, Blue Velvet ends the battle between Wallace and his teachers by synthesizing their positions, showing that neither held the secret to effective aesthetic representation. Seeing differently led to Wallace creating differently, and Wallace composes most of his work after this epiphanic encounter with Blue Velvet . His fiction grows even more Lynchian after writing “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” his account of his visit to the set of Lost Highway .In the parlance of adaptation studies, Blue Velvet represented “a new communicative situation” for Wallace that “recontextualize[d]” artistic creation for him in a manner that permitted him to “generate new versions” from a “liberat[ed]” perspective (Casetti 82; Bryant 48, 50).

What is perhaps most revelatory for Wallace here is that this epiphany comes in the package of a relatively mainstream film. Blue Velvet may have been an independent production, but it was financed by megaproducer Dino DeLaurentis and went on to receive multiple Oscar nominations in an era where it was rare for indie films even to be acknowledged by the Academy. David Lynch may be one of the most experimental and avant-garde American narrative filmmakers, but his work has reached a tremendous audience, making him and his sensibility as “American” as Lumberton or Twin Peaks. From Blue Velvet onward, Lynch works within the Hollywood system but makes films that continually disrupt conventional narrative cinema by smuggling avant-garde experimentation into traditional Hollywood structures (see Figure 1), and his success in doing this has largely served as the model followed by filmmakers of the independent cinema boom of the 1980s and 1990s (Sheen and Davison 2; Rombes 71). Despite his admiration of the experimental and avant-garde, Wallace sought mainstream success and viewed Lynch as the artist capable of “broker[ing] a new marriage between art and commerce in U.S. movies, opening formula-frozen Hollywood to some of the eccentricity and vigor of art film” (Wallace, “David Lynch” 149). Lynch and Wallace achieve this balance in their best work: their art is fragmented but features three-dimensional characters, non-linear but “in the service of human emotion, and with the same motives” (Pitari 156).

Artifice’s Sincere Core

One of the most prominent lines of inquiry into Wallace’s work examines how his fiction rejects ironic postmodern gamesmanship in favor of a more sincere engagement with the reader. These readings of Wallace take as their starting point what Adam Kelly has called the “essay-interview nexus”: Wallace’s essay “ E Unibus Pluram : Television and U.S. Fiction” and his interview with Larry McCaffery, both originally published in The Review of Contemporary Fiction in 1993. Wallace closes “ E Unibus ” with an oft-quoted paragraph that many interpret as Wallace’s manifesto for a new kind of fiction in which “the next real literary ‘rebels’” will “back away from ironic watching,” “eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue,” and “have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles” and “risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama” (81). By freeing themselves from irony-laden image fiction, Wallace’s literary rebels will gain greater access to the kind of genuine feeling that slick commercial postmodernism has used irony to shield itself from and, in doing so, liberate readers to rediscover the value of living with affect rather than ironic detachment.

Critics generally accept this rejection of postmodern irony in “ E Unibus ”as Wallace’s unique contribution to American fiction, but this reading overlooks how much his postironic project is indebted to David Lynch. Blue Velvet provides Wallace with the roadmap for “how to recover sincerity without losing the critical edge that irony provides” (Rombes 75). Blue Velvet ’s “Robins of Love” scene typifies how complex Lynch’s understanding and use of irony really are. The scene takes place the day after Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) spies on Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) brutally assaulting Dorothy Valens (Isabella Rossellini). In the scene, Jeffrey asks Sandy (Laura Dern) “Why are there [bad] people like Frank? Why is there so much trouble in this world?” Sandy responds by telling Jeffrey about a dream she had in which “for the longest time there was this darkness” in the world “because there weren’t any robins.” “The robins,” she says “represented love”; however, the dream suddenly changed when “thousands of robins were set free” and “brought this blinding light of love” to the earth, which Sandy concludes means “there is trouble until the robins come.” As she delivers this speech with intense emotion (see Figure 2), Angelo Badalamenti’s score swells with yearning toward a hopeful crescendo. The scene teeters on the edge of parodying melodramatic sentimentality; however, Lynch earnestly endorses Sandy’s vision: the film even ends with a shot of a robin perched on a branch, a dark, evil-looking bug (similar to the beetles in the film’s opening sequence) trapped in its beak. Such a speech and scene may appear ridiculous to a knowing viewer, but Lynch’s film implies that such hopeful earnestness may be the only defense against the vile and sadistic cynicism of Frank Booth. Scenes like this run throughout Lynch’s filmography, and they, even more than Wallace, bravely “risk the yawn, the rolled eyes” from critics and audience members who view “ironic self-consciousness [as] the one and only universally recognized badge of sophistication” (Wallace, “ E Unibus ” 81;“David Lynch” 199, 198). This knowing earnestness makes Lynch’s work both more formally accomplished and emotionally engaging than its hiply jaded ironic counterparts.

The divisive reactions to Lynch’s films demonstrate how complex his understanding of irony is in practice. Nicholas Rombes outlines how some critics see his work as “a canonical representative” of postmodern irony, others argue that it “confounds the orthodoxies of postmodern irony,” while others view Lynch as being complicit in reactionary Reaganite values (62, 70). Rombes effectively pushes back against claims that Lynch’s films act as “send-up[s] of misplaced innocence” or “subversive expose[s] of a kind of sham past,” arguing for viewing Lynch’s sensibility as “sincerity-in-irony”: “Lynch’s work offers a glimpse of what possibly lies ahead, after postmodernism. Lynch’s films fully enact, rather than reflect, the postmodern […] but with none of the high seriousness of modernism, nor the ironic, ‘in-crowd’ detachment of postmodernism” (75). Lynch enacts sincerity-in-irony via a self-conscious film style that exposes cinema as simultaneously “empty and full” (Nieland 107). For example, the Club Silencio scene in Mulholland Drive starts with the emcee announcing to the audience that “there is no band” and every sound they will hear at the club “is a tape recording” (see Figure 3). After this statement, Rebekah Del Rio takes the stage and performs an incredibly moving Spanish-language rendition of Roy Orbison’s “Crying” (see Figure 4). She is so overcome during the performance that she collapses; however, her impassioned vocals continue because they are, as the emcee previously announced, a tape recording that she has been lip-synching to the entire time. Lynch foregrounds cinema’s artifice in this scene to grant Mulholland Drive ’s viewers permission to be affected by Del Rio’s performance openly and unironically. Del Rio’s collapse shocks them, even though it merely confirms what they had just been told. With such an open admission of artifice up-front, Lynch takes the defensive “it’s only a movie” pose away from the audience, and George Toles suggests that the audience “is secretly pleased to have [their skepticism] taken away, and to be suddenly at the mercy of a sincerity hatched at the very core of artifice” (11).

In acknowledging and validating the viewer’s skepticism, Lynch defuses it and illustrates the real power of cinema: it is entirely artificial, but the audience’s awareness of that artifice enables outpourings of genuine emotion on both sides of the screen. Lynch’s ironic overtures disarm cynical viewers, luring them into the very emotional engagement that they thought they were too sophisticated to succumb to. Lynch courts viewers’ desire for “ironic kitsch consumption” only to guide them past their comforting ironic defenses toward “a less self-conscious emotional involvement” with the characters and the material (Ayers 103). Lynch’s “happy ending is not a knowing wink at happy endings, but rather a sincere invitation to an actual happy ending” (Rombes 72). Thus, the most intense conflict in Lynch’s films occurs between the audience and the film because audiences must acknowledge how culture has conditioned them to interpret intense outpourings of sincere emotion, such as Sandy’s dream of robins or Sarah Palmer’s reaction to Laura’s death in Twin Peaks (see Figure 5), as ironic, phony, or sentimental (65).

Wallace’s absorbed adaptation of Lynch’s sincerity-in-irony appears most prominently in his later story collections, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men and Oblivion . These texts constitute what Francesco Casetti calls a “reappearance” of Lynch’s material and sensibility that stands as “a new discursive event” that, while firmly grounded in its own context, contains traces of a previous one to create “a new communicative situation” that “recontextualize[s]” the text (82). Like Lynch, the self-reflexive narratives that shape many of these stories become gateways to finding genuinely felt emotion in an artificial world, not defenses against it (Hainge 149). Halfway through his 1999 story “Octet,” the “pseudopomo” gimmick of a pop quiz structure that has organized the first half of the story gives way to a more urgent interrogation of the purpose of postmodern trickery, authorial interpolation, and self-awareness when the narrative voice of the story addresses the reader directly and asks the reader to imagine themselves as a Fiction-Writer attempting to write a story comprised of a series of pop quizzes that is not turning out the way they wanted it to. This interrogation builds in intensity (and recursivity) until the narrator places the reader and writer in the same position, both “quivering in the mud of the trench,” both “fundamentally lost and confused and frightened and unsure about whether to trust even your most fundamental intuitions about urgency and sameness and whether other people deep inside experience things in anything like the same way you do” (159, 160). “The Soul is Not a Smithy” depicts a traumatized elementary school student constructing a narrative to mentally escape the fact that his substitute teacher has taken his class hostage, only to have details from the terror unfolding around him seep into these fantasies. The story’s ending masterfully applies the folly of such narrative repression to the entire nation via an American history pageant in which America’s violent past gets glamorized through a sugarcoated lens of “aluminum foil bayonets” and “papier mâché bulwarks” that is eerily reminiscent of Lynch’s celebrated opening to Blue Velvet (see Figure 6) (113). Like that opening sequence, the pageant in “Smithy” reveals how these repressive tendencies are not just the habits of one schoolboy or town but of an entire country, thus alerting the reader to how they have been conditioned to repress horrors around them by masking these events in narratives of their own imagination. Fiction then becomes both an escape from a horrifying reality and a manifestation of that reality. Viewing the ending of “Smithy” as a “reappearance” of Lynch’s thematic material places both works in a new context that only intensifies their communicative power. Wallace’s absorbed reshaping of Lynch’s aesthetic and thematic concerns suggests adaptation is a broader creative endeavor with more permeable boundaries than generally thought.

The Uncomfortable Mirror

The self-reflexive fiction Wallace produces from Lynch’s self-reflexive cinema continually pushes out from the page to address, confront, and connect with the reader in the hopes of achieving literature’s transformative potential. Such work foregrounds and acknowledges its own artifice, alerts the audience to the presence of a creative consciousness controlling the text, and then uses that awareness to deconstruct the audience’s critical defenses and make them uncomfortably aware of their own position as spectators and subjects for the purpose of steering the reader to a more mindful and attentive state of awareness in their own lives. Paolo Pitari claims “there is no art, for Wallace and Lynch, without an active audience” (164). The interaction between audience and artist in their work enacts a kind of “magical thinking” where borders become porous and readers experience a “mediated intimacy” in which the “uncanny subject [is] never quite present to itself” but the work acts “as a kind of mediumistic host to the abstract transmission of psychic energies” between author and reader (Nieland 135). Such “abstract transmission[s] of psychic energies” can border on cruel confrontation because they often implicate the audience and the author equally. For Wallace, this dynamic is how Lynch asserts his presence in the text: he “get[s] inside your head” by offering an unobstructed view inside his own, which gives viewers a glimpse at “some of the very parts of [themselves they’ve] gone to the movies to try to forget about” (Wallace, “David Lynch” 171, 167). Elsewhere Wallace describes this confrontational approach to writing fiction when he describes a potent writer as “an architect who [can] hate enough to feel enough to love enough to perpetrate the kind of special cruelty only real lovers can inflict” (Wallace, “Westward” 332). Art’s uncomfortable mirror, for Wallace, constitutes a gesture of love because, rather than trying to please its audience by delivering the fleeting pleasure they want in the moment, the work presents them with what they need to move through the world as fuller, more compassionate human beings.

Wallace absorbs such ideas about confrontational fiction from iconic Lynchian scenes such as Frank forcing Jeffrey to watch him abuse Dorothy Valens in Blue Velvet (see Figure 7). The camera occupies Jeffrey’s position in the back seat of Frank’s car looking at Frank in the front, aligning the audience’s point of view with Jeffrey’s. The audience has been encouraged to identify with Jeffrey throughout the film, and now, like Jeffrey, they look on in fear and disgust, eager to escape, to look away. However, they cannot: the camera’s gaze, like Jeffery’s, remains fixed on Frank in perverse fascination and terror. Suddenly, Frank turns to Jeffrey, stares into the camera with wild eyes, and lustfully proclaims “You’re like me.” In the reverse shot, Jeffrey immediately looks down and away in shame (see Figure 8). Lynch’s camera placement, editing, and subtle rupture of the fourth wall fill an already dreadful scene with a shock of recognition because the camera forces the captive audience to accept that Frank’s statement applies as much to themselves as it does to Jeffrey Beaumont, perhaps even more so. After all, their watching is voluntary; no one is pinning them to their seat. This moment typifies the emotional impact of self-reflexive sincerity-in-irony in Lynch’s films that Wallace adapts most directly in Infinite Jest ’s critiques of passive entertainment consumption and Brief Interviews with Hideous Men ’s extended dissections of misogyny and rape culture.

According to Wallace’s reading of Lynch and his own absorbed adaptation of Lynch’s work, this effect cannot be achieved without immersing the audience in the mind of the creator. Inhabiting someone else’s consciousness is more than an authoritarian demonstration of control that seeks to “vulnerabilize” and “dominate”; rather, it forces audiences to peer out “through the tiny little keyhole” of themselves and confront that other people do in fact experience things in the same way that they do, even if they were not aware of it beforehand and would prefer not to acknowledge it upon discovery (Wallace, “David Lynch” 169; “Good Old Neon” 180). Lynch and Wallace’s audiences look at the screen and the page hoping to find a window offering a privileged look at another reality, only to see that window slowly changing into a mirror that reflects an unflinching look at intimate parts of themselves they have strived to ignore.

The Traumatic Authenticity of Artifice

The most sustained, effective, and traumatic of Lynch’s mirrors to reappear as “a new discursive event” in Wallace’s absorbed adaptation is also one of Lynch’s most archetypal characters: Twin Peak s’ Laura Palmer (see Figure 9). Wallace, acting as one of John Bryant’s “revising readers,” overpopulates his fiction with beautiful, high-achieving characters who, like Laura Palmer, are “radiant on the surface but dying inside” because they are tormented by the fear that their beauty and achievement confirm their inherent, inescapable fraudulence (Rodley 184). These “reshape[d]” characters first appear after Wallace’s transformative encounter with Lynch in early stories such as “My Appearance.” After Lynch introduces the world to Laura Palmer, versions of this character occur with increasing frequency in Wallace through “quotation, allusion, and plagiarism” in works such as Infinite Jest (Hal Incandenza, the other students at Enfield Tennis Academy, Prettiest Girl of All Time Joelle van Dyne), Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (“The Depressed Person,” “The Devil is a Busy Man,” “Octet”), on to Oblivion and his posthumous novel The Pale King , both of which feature Wallace adapting the Laura Palmer character to his own authorial persona.

Stephen Burn describes Wallace’s prose as “double-voiced” in that it is imbued with “the quality of ‘ both ness,’” and Paolo Pitari cites this “ both ness” as representative of the “divided consciousnesses that Wallace sees in Lynch’s work” and adapts his own fiction (Burn 61, 72; Pitari 163). Laura Palmer embodies this split consciousness and serves as the source material for many of Wallace’s most engaging split protagonists. As the Twin Peaks saga goes on, audiences see how Laura Palmer’s status as “the cultural image of desire” alienates her from herself and the world (Nochimson, Passion 174). Embodying an abstract, depersonalized cultural ideal—the blond, high-achieving, self-sacrificing homecoming queen—creates “a fundamental emptiness” at the center of Laura Palmer (McGowan 131). Not only can others not see her pain, but they cannot see that her pain comes from an absence, the emptiness that arises from being an object in the eyes of others. Fire Walk with Me intensifies her split consciousness further when viewers discover that Laura’s erratic, dissociative behavior originates in sexual trauma and incest (see Figure 10). The disappointment that some Twin Peaks fans experience watching Fire Walk with Me derives from the realization that not only does Laura Palmer fail to live up to the fantasy and mystery they have imposed upon her as viewers, but that all she reveals “is that she has nothing to reveal,” except perhaps that “the object at the center of our most profound cultural fantasy has an emptiness where the fantasy posits a fullness” (McGowan 133, 132).

George Toles notes that Lynch inflicts the “greatest torments [on] those most deeply enfolded in artifice,” proving that “the fact of a character’s conspicuous fabrication is no safeguard against real hurt” (4). Wallace dramatizes this jarring dynamic best in his story “Good Old Neon,” adapting the relationship the viewer has with Laura Palmer to the one David Wallace has with Neal, the story’s apparent narrator, who, like Laura, has a “neon aura around him all the time” (Wallace, “Good Old Neon” 180). Despite all his accolades, Neal defines himself as a fraud with “no true inner self,” who is “trapped in a false way of being,” surrounded by other people too “pliable and credulous” to detect his emptiness and pain (Wallace, “Good Old Neon” 160, 145, 154). Like Laura Palmer, the reader’s identification with Neal comes from confronting his emptiness, and Wallace, like Lynch, allows readers to inhabit “the impossible perspective of the absent object” (McGowan 134). Neal is, as yoga instructor Master Gurpreet calls him, “the statue”: a monument to some higher ideal, but lifeless, inert, and impenetrable (Wallace, “Good Old Neon” 159). Like Laura, Neal cannot even experience his suffering as real because being “a fair-haired boy […] on the fast track” who is also deeply unhappy despite his accomplishments is “such a cliché” (142). In fact, Neal decides to end his life after seeing his pain reduced to a punchline on a sitcom: his turmoil is so commonplace as to be “the butt of a joke” for a mass audience (169). As it does to Laura, the culture alienates Neal from his own alienation, and their mutual tragedy is the inability of the people around them to comprehend that one can be both “impressive and authentically at ease in the world” and a “dithering, pathetically self-conscious outline or ghost of a person” (180, 181). Characters like Laura and Neal allow Wallace and Lynch to sincerely demonstrate both the reality within the fake and the fakery within the real, allowing these characters to testify to the authenticity of feelings of artifice and fraudulence, asserting that feeling like a fake in a materialistic culture consumed by the appearance of achievement is perhaps the most real feeling of all.

Neal, as Wallace says of Laura Palmer, “is both ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ and yet also neither: [he’s] complex, contradictory, real” (Wallace, “David Lynch” 211). “Good Old Neon” ends with Wallace pushing Laura Palmer’s split consciousness beyond a single character when the story shifts its point of view to reveal that Neal’s entire monologue may in fact be entirely in the mind of David Wallace, who peers “through the tiny little keyhole of himself, to imagine what all must have happened to lead up to [Neal’s] death” by suicide (180). This point-of-view shift resembles the final act of Mulholland Drive , which reveals Betty to be as much a projection of Diane’s fragmented psyche as Neal is a projection of David Wallace’s thoughts about himself; however, Wallace’s absorbed adaptation of Lynch broadens the effect of this split from the characters in the work outward to the author and, by extension, the reader, thus dissolving all remaining boundaries to create a space of intense identification born out of the conflict between one’s outer “neon aura” and one’s inner turmoil.

The fact that such fluidity occurs in Wallace and Lynch at the levels of form and content invites adaptation scholars to pursue the “fluid relationships” among media works described in Linda Hutcheon’s “continuum model” of adaptation more vigorously (171). By “revisit[ing],” “(re)-interpret[ing],” and “(re)-creat[ing]” a figure such as Laura Palmer, Wallace’s “double-voiced” both ness illuminates not only Laura Palmer and Neal but Lynch’s and Wallace’s porous approaches to their art (Hutcheon 172). Wallace posits that Lynch’s both ness makes viewers reject him and his work because “it require[s] of us an empathetic confrontation with the exact same muddy both ness in ourselves and our intimates that makes the real world of moral selves so tense and uncomfortable” (211). From Twin Peaks onward, Lynch’s work investigates the cascade of contradictions that constitute selfhood, and Wallace adapts and extends Lynch’s exploration of contradictory selfhood in Oblivion to show how both ness becomes the human condition (Rombes 75). Oblivion , Fire Walk with Me , Lost Highway , Mulholland Drive , and Inland Empire depict tortured souls who “[suffer] personhood as tragedy”; their becoming aware of themselves and their realities becomes a traumatic experience, a nightmare from which they cannot awaken (Nieland 99). Wallace shares Lynch’s increasing concern with trauma’s effect on consciousness, and he adapts it in Oblivion to suggest that consciousness is trauma and that “language is the vortex of the clash between culture and the subconscious” (Nochimson, Passion 202). “Inside and outside are distinctions that no longer hold” in Lynch and Wallace; Lynch externalizes the pressures normality imposes on a person as forces abusing a body and as spaces opening up to allow those forces in, while Wallace in Oblivion depicts these pressures as being so all-consuming internally as to prevent characters from ever seeing through “the tiny little keyhole” of themselves (Nochimson, Passion 176). Both echo Robert Stam’s understanding of a literary text as “an open structure” that can “be reworked by a boundless context” because each demonstrates how a text is but “an intersection” of “variations on [anonymous] formulae, conscious and unconscious quotations, and conflations and intersections of other texts” (57, 64).

Filling the Hole of Language

The differences between Lynch’s and Wallace’s chosen media can be felt most in the main point of thematic divergence between the two artists: In his absorbed adaptation of Lynch from film to fiction, Wallace is far less optimistic. Lynch’s characters frequently achieve a kind of victory or transcendence, however measured, over the forces that torment them. The endings to Eraserhead , Blue Velvet , Wild at Heart , Fire Walk with Me , and Inland Empire each offer “tiny instant[s]” where their protagonists “feel suddenly connected to something larger and much more of the complete picture” (see Figure 11) (Wallace, “Good Old Neon” 149; Nochimson “All I Need” 179). In Wallace’s fiction, characters frequently wind up trapped within their own heads, unable to communicate or be understood. Neal may speak at great length in “Good Old Neon,” both to the reader and to various therapists, holy men, and life coaches in the story, but he uses language to construct barriers between himself and others, to the extent that every utterance moves him further away from connection. This failure to communicate stems from Neal’s fundamental distrust of language: he claims that “try[ing] to convey to other people what we’re thinking and to find out what they’re thinking [is] a charade […] What goes on inside is just too fast and huge and all interconnected for words to do more than barely sketch the outlines of at most one tiny little part of it at any given instant” (Wallace, “Good Old Neon” 151). Wallace does not locate a clear “exit from the linguistic labyrinth”; if one does exist, it does not present itself as “richly available to us” in his fiction (Nochimson, Passion 4).

In this regard, Lynch parts ways with his ironic postmodern counterparts such as Quentin Tarantino or the Coen Brothers and rejects the notion of “culture as a kind of solipsism, language as a kind of chimera, and meaning as a phantom” (Nochimson, Passion 19). Instead, his self-reflexive sincerity-in-irony envisions a transcendent, enlightened state that exists beyond language but is accessible through cinema. Lynch can present a more optimistic view of communication than Wallace because, as a filmmaker, he has more languages at his disposal than Wallace does as a fiction writer. As Robert Stam explains, film is “both a synesthetic and a synthetic art,” a “multitrack medium” (as opposed to fiction’s single-track) that “can play not only with words” but images, sounds, motion, etc., making it open “to all types of collective representation” (61, 56, 61). Martha Nochimson describes Lynch’s cinematic language in incredibly open, fluid terms, showing how a multitrack language like cinema can generate genuine, sustained moments of empathy and transcendence:

“eye and picture are in each other , as they move together. Lynch has internalized […] a sense of narrative image that holds the possibility, not of the doomed quest for an illusory holy grail, but of empathy—among people, and between people and the universe. His belief in the image as a possible bridge to the real does not depend on any abstract framework but rather on a visceral sense of the essential truth of an empathetic—not solipsistic—relationship with art” ( Passion 9).

Wallace’s single-track fiction can imagine and gesture toward but never realize such a dynamic. The multitrack work of images, music, and sounds in Lynch’s cinema succeeds because it is “not English anymore, it’s not getting squeezed through any hole” (Wallace, “Good Old Neon” 179).

The final lines of “Good Old Neon” and Mulholland Drive , “Not another word” and “Silencio,” may appear to be literal copies of each other; however, while “not another word” signals the termination of fiction’s ability to communicate, “Silencio” does not “silence” cinema’s communicative potential (see Figure 12). Lynch’s belief in the real possibility of transcendence follows from the fact that cinema is not dependent upon the verbal; if anything, especially in Lynch’s heavily psychological cinema, its origins are pre-verbal and can continue to peer out through the “tiny little keyhole” of the camera without having to worry about “squeezing” what it sees through the hole of language. Wallace’s absorbed “film-to-page adaptation” of Lynch offers a convincing rebuttal to the commonly held belief among fans and scholars alike that film limits the possibilities offered by a literary text.

Stating that Wallace’s work ought to be considered as an absorbed adaptation of Lynch’s work or even that David Lynch is a tremendous influence on David Foster Wallace does not limit Wallace’s work “to the single function of replicating” his source text, nor does it treat Wallace’s work as little more than “an intertext designed to be looked through, like a window on the source text” of Lynch (Leitch 17). Rather, this analysis has demonstrated the ways in which adaptation theory enriches one’s understanding of Lynch’s and Wallace’s larger project as artists and the ways in which their chosen media enhance the communicative power of their respective projects, especially during the 1990s when they were at their most active. Regarding Wallace as a revising reader engaged in an absorbed adaptation of Lynch broadens the scope of Wallace’s artistry because it allows one to appreciate the fluidity in his work both in form and content with greater depth than a more limited focus on his textual influences would allow. Further, acknowledging and investigating the depth of influence a filmmaker has on an author illuminates the extent to which contemporary authors attend to and are influenced by modern image culture. Wallace’s absorbed adaptation of Lynch can serve as a case study that opens adaptation studies to a new field of inquiry that accounts for richly original work such as Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch and Wallace’s fiction and more accurately engages with the ways in which fiction itself absorbs and represents the larger world of media.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Matthew Luter and Alexander Moran, who carefully read early drafts, suggested additional sources, and gave generous encouragement and substantive feedback. Jeffrey Severs chatted with me about the idea in between rounds of karaoke, and the first half of this paper is clearer because of it. I am also grateful to the anonymous reader who helped me clarify my arguments during the peer-review process.

1 While such examples are numerous, of particular interest are Todd McGowan’s The Impossible David Lynch , Alistair Mactaggart’s The Film Paintings of David Lynch ,Martha Nochimson’s The Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in Hollywood , and Justus Nieland’s David Lynch , which examines the influence of architecture and interior design on Lynch’s aesthetics. Room to Dream , Lynch’s unique biography-memoir written in collaboration with Kristine McKenna, also provides extended discussions of the influence these artists had on Lynch.

2 Tracking the varied influences on Wallace’s work constitutes its own cottage industry, but Wallace in part initiates this discussion in his seminal interview with Larry McCaffery in The Review of Contemporary Fiction , later published in full in Conversations with David Foster Wallace .

3 I must concede I am not the first person to discuss Lynch’s influence on Wallace. Dan Dixon presented a paper entitled “‘David Lynch is Interested in the Ear’: The Shared Focus of David Lynch and David Foster Wallace” at Illinois State University’s David Foster Wallace conference in 2015, in which he read “David Lynch Keeps His Head” as Wallace’s “artistic manifesto.” The popular online magazine Bright Wall/Dark Room published an essay by Daniel Carlson on Wallace and Lynch in the fall of 2017, and Paolo Pitari published a sustained analysis of Lynch’s influence on Infinite Jest in Camera-Stylo in 2017. While each piece has its merits, none captures the full scope of Wallace’s engagement with Lynch. Dixon’s presentation examines Wallace’s essay on Lynch primarily as a site to better understand Wallace’s views on artistic creation. Carlson uses Infinite Jest to discuss Lynch’s cinema as “anticonfluential” but does not refer at all to Wallace’s writing on Lynch. And Pitari’s essay maps the plot of Blue Velvet onto Infinite Jest , going so far as to argue that Lynch is “Wallace’s alter ego” and that “David Lynch Keeps His Head” should be considered part of the “essay-interview nexus,” which he proposes renaming the “essay-interview-essay” nexus (156).

Works Cited

Ayers, Sheli. "Twin Peaks, Weak Language and the Resurrection of Affect." The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions , Edited by Erica Sheen and Annette Davison, Wallflower, 2005, pp. 93-106.

Bryant, John. "Textual Identity and Adaptive Revision: Editing Adaptation as a Fluid Text." Adaptation Studies: New Challenges, New Directions , Edited by Jorgen Bruhn, Anne Gjelsvik, and Eirik Frisvold Hanssen, Bloomsbury, 2013, pp. 47-68.

Burn, Stephen J. “‘Webs of Nerves Pulsing and Firing’: Infinite Jest and the Science of Mind.” A Companion to David Foster Wallace Studies, edited by Marshall Boswell and Stephen J. Burn, Palgrave, 2013, pp. 59-86.

Carlson, Daniel. "David Lynch's Search for Meaning." Bright Wall/Dark Room , 51, 2017, www.brightwalldarkroom.com/2017/08/31/david-lynchs-search-for-meaning/. Accessed 23 March 2019.

Casetti, Francesco. "Adaptation and Mis-adaptations: Film, Literature, and Social Discourses." Translated by Alessandro Raengo, A Companion to Literature and Film , Edited by Robert Stam and Alessandro Raengo, Blackwell, 2004, pp. 81-91.

Dixon, Dan. “‘David Lynch is Interested in the Ear’: The Shared Focus of David Lynch and David Foster Wallace.” David Foster Wallace Conference, 28 May 2015, Marriott Hotel, Normal, IL.

Hainge, Greg. "Weird or Loopy? Specular Spaces, Feedback and Artifice in Lost Highway's Aesthetics of Sensation." The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions , Edited by Erica Sheen and Annette Davison, Wallflower, 2005, pp. 136-150.

Hutcheon, Linda, with Siobhan O'Flynn. A Theory of Adaptation . 2 nd ed., Routledge, 2013.

Kelly, Adam. “David Foster Wallace: The Death of the Author and the Birth of a Discipline.” IJAS Online , no. 2, 2010.

Leitch, Thomas M. Film Adaptation and Its Discontents: From Gone with the Wind to The Passion of the Christ. Johns Hopkins, 2007.

Luter, Matthew. " “ Weekend Warriors: DeLillo’s “The Uniforms,” Players , and Film-to-Page Reappearance”, Orbit: A Journal of American Literature , 4, 2, 2016.

McGowan, Todd. The Impossible David Lynch . Columbia, 2007.

Nieland, Justus. David Lynch . University of Illinois, 2012.

Nochimson, Martha P. "'All I Need is the Girl': The Life and Death of Creativity in Mulholland Drive." The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions , Edited by Erica Sheen and Annette Davison, Wallflower, 2005, pp. 165-181.

—. The Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in Hollywood .University of Texas Press, 1997.

Pitari, Paolo. "David Lynch's Influence on David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest." Camera Stylo , 12, 2017, pp. 153-165.

Rodley, Chris, ed. Lynch on Lynch . Faber and Faber, 1997.

Rombes, Nicholas. "Blue Velvet Underground: David Lynch's Post-Punk Poetics." The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions , Edited by Erica Sheen and Annette Davison, Wallflower, 2005, pp. 61-76.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Two Forms of Adaptation: Housekeeping and Naked Lunch ." Film Adaptation , Edited by James Naremore, Rutgers, 2000, pp. 206-220.

Sheen, Erica and Annette Davison. "American Dreams, Nightmare Visions." The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions , Edited by Erica Sheen and Annette Davison, Wallflower, 2005, pp. 1-4.

Stam, Robert. "Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation." Film Adaptation , Edited by James Naremore, Rutgers, 2000, pp. 54-76.

Toles, George. "Auditioning Betty in Mulholland Drive." Film Quarterly , 58, 1, 2004, pp. 2-13.

Wallace, David Foster. "David Lynch Keeps His Head." A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments , Back Bay, 1998, pp. 146-212.

—. "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U. S. Fiction." A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments , Back Bay, 1998, pp. 21-82.

—. "Good Old Neon." Oblivion: Stories , Back Bay, 2005, pp. 141-181.

—. "Octet." Brief Interviews with Hideous Men ,Back Bay, 2000, pp. 131-160.

—. "The Soul is Not a Smithy." Oblivion: Stories , Back Bay, 2005, pp. 67-113.

—. "Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way." Girl with Curious Hair , Norton, 1989, pp. 231-373.

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

The Surreal Filmmaking of David Lynch Explained in 9 Video Essays

in Film | December 14th, 2016 1 Comment

The internet is full of people who don’t understand David Lynch movies: some ask for appreciation assistance on Quora , others defend their distaste on Reddit , and others still simply declare both the filmmaker and his fans a lost cause . But the internet is also full of people who, whether they claim to understand them or not, genuinely love David Lynch movies, and some of them make video essays explaining, or at least shedding additional light on, just what makes the seemingly inscrutable likes of Eraserhead , Blue Velvet , Mulholland Drive , and the television series Twin Peaks (as well as Lynch’s less-acclaimed projects) such high cinematic achievements.

The latest, “David Lynch — The Elusive Subconscious,” comes from Lewis Bond’s Channel Criswell , the source for video essays on Andrei Tarkovsky , Yasujiro Ozu , Stanley Kubrick , Akira Kurosawa , and the horror genre previously featured here on Open Culture. It includes a clip of Charlie Rose asking Lynch himself the meaning of the word “Lynchian.” The director’s reply: “I haven’t got a clue. When you’re inside of it, you can’t see it.”

Bond looks for Lynchian by diving right in, finding how Lynch’s movies go about their signature work of “producing the unfamiliarity in that which was once familiar” by using just the right kinds of vagueness, ambiguity, incompleteness, inconsistency, unpredictability, and dualism in their images, sounds and stories to produce just the right kinds of doubt, fear, and distress in their characters and viewers alike.

A further definition of the Lynchian comes in “What is ‘Lynchian’?” by Fandor’s Kevin B. Lee, which adapts a section of film critic and Lynch scholar Dennis Lim’s David Lynch: The Man from Another Place . It, too, draws on an episode of Charlie Rose , though not any of Lynch’s appearances at the table but David Foster Wallace’s . “What the really great artists do is, they’re entirely themselves,” Wallace says in response to a question about his interest in Lynch’s work. “They’ve got their own vision, their own way of fracturing reality, and if it’s authentic and true, you will feel it in your nerve endings. And this is what Blue Velvet did for me.”

Wallace had appeared on the show ostensibly to promote his essay collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again , which contains the expanded version of “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” the 1996 Premiere magazine article that took him to the set of Lost Highway and on the intellectual mission of pinning down what, exactly, gives Lynch’s work at its best so much and so strange a power. Lee, via Lim, quotes Wallace’s working definition of “Lynchian,” which for many fans remains the best anyone has ever come up with: that it “refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.”

As one of the most visually oriented of all living filmmakers, Lynch expresses this particular kind of irony much less in words than in imagery, specifically the kind of imagery that viewers describe in terms of dreams — and not always the good kind. “Beautiful Nightmares: David Lynch’s Collective Dream” by Indiewire’s Nelson Carvajal gathers some of the elements of Lynch’s visions: the dancing, the picket-fence domesticity, the red curtains, the blondes, the creepy stares, the disfigurement, the voyeurism. “I grew up in the northwest, in a very, very beautiful world,” says Lynch, fairly summing up the experience of his own movies in the video’s only spoken words. “A lot of my life has been discovering this strange sickness. It’s got a fascination to me. I love the idea of going into something and discovering a world, being able to watch it and experience it. It’s a disturbing thing, because it’s a trip beneath a beautiful surface, but to a fairly uneasy interior.”

Several of Lynch’s techniques come in for more thorough analysis in a trilogy of video essays Andreas Halskov made for the Danish film-studies journal 16:9 . “Between Two Worlds” deals with the host of “competing moods, genres and tonalities” that manifest in each one of his films and produce “an ambivalent or uncanny experience on the part of the viewer.” “What’s the Frequency, David?” explores the presence in Lynch’s work of “noise and faulty wiring, hiccups and miscommunication,” and “electronic devices that don’t work,” all of which illustrate “the constant battle between the conscious and the unconscious world” so important to his stories. “Moving Pictures” identifies the influence of painters like René Magritte, Francis Bacon, Edward Hopper, Vilhelm Hammershøi, and Salvador Dalí on Lynch who, having started out as a painter himself, begins his films not with stories but images and builds them from there.

Whatever has influenced Lynch’s movies, Lynch’s movies have exerted plenty of influence of their own. Critic Pauline Kael called Lynch “the first popular surrealist,” and with that popularity has come an integration of his brand of surrealism into the wider cinematic zeitgeist. Jacob T. Swinney’s “Not Directed By David Lynch” cuts together five minutes’ worth of especially Lynchian moments from other directors’ movies over the past quarter-century, a formidable selection including Adrian Lyne’s Jacob’s Ladder , Darren Aronofsky’s Pi and Requiem for a Dream , Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko , Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible and Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin .

But while some filmmakers have consciously or unconsciously drawn inspiration from or paid homage to Lynch, other filmmakers have tried to cash in on the popularity of his style in much less creative ways. Or at least so argues “David Lynch’s Lost Highway as a Commentary on Other Directors” by Jeff Keeling, a video essay that puts Lynch’s 1997 neo-noir up against a few other pieces of film and television that came out in the years preceding it, especially the Oliver Stone-directed feature Natural Born Killers and the Oliver Stone-produced series Wild Palms . Pointing out the numerous ways in which Lynch references the too-direct borrowings that Stone and others had recently made from his own work, Keeling not unconvincingly frames Lost Highway as, among other things, a cinematic j’accuse .

Though poorly reviewed upon its original release, Lost Highway has put together a decent following in the nearly two decades since. But whatever acclaim it now draws can’t compare to the praise lavished upon Lynch’s 2001 television-pilot-turned-feature-film Mulholland Drive , which a BBC critics poll recently named the best movie of the 21st century so far . In “ Mulholland Drive: How Lynch Manipulates You,” Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, breaks down how it subverts the expectations we’ve developed through moviegoing itself, one of the storytelling strategies Lynch uses to make this particular tale of death, sex, Hollywood, the sudden loss of identity (and, needless to say, a platinum-haired ingenue, menacing heavies, and a mysterious dwarf) so very compelling indeed.

If, however, none of these video essays get you believing in Lynch as a creative genius, then you’ll surely enjoy a hearty laugh with Joe McClean’s “How to Make a David Lynch Film,” a short but elaborate satire of the tropes of Lynchianism presented as an instructional film — made in the style of Lynch’s beloved 1950s — inside the setting of Lost Highway . Its commandments, many of which overlap in one way or another with the points made in the analytical video essays higher above, include “Start by having dramatic pauses between every line of dialogue,” “There must be ominous music or sounds in every scene,” “When in doubt, add close-ups of lips and eyes,” and “There should be nudity for absolutely no reason.” (The video contains some potentially NSFW content, though only in service of parodying the NSFW content of Lynch’s movies themselves.)

“I watch David Lynch movies and I just don’t understand them,” writes McClean. “I decided I was going to try and figure them out so I stapled my eyes open and had a Lynch-a-thon. It didn’t help. I thought if I forced myself to watch, at some point it would just click and it would all make since. That never happened.” But perhaps he tried too hard to understand them, rather than not enough. Lynch, in the words of Lewis Bond, “intentionally misguides our perceptions through offering plots that embrace a subconscious manner of storytelling. Our expectations so often go unfulfilled in his movies because he shows that we expect so much from life, yet know so little.”

Related Content:

A Young David Lynch Talks About Eraserhead in One of His First Recorded Interviews (1979)

The Incredibly Strange Film Show : Revisit 1980s Documentaries on David Lynch, John Waters, Alejandro Jodorowsky & Other Filmmakers

David Lynch Presents the History of Surrealist Film (1987)

An Introduction to Jean-Luc Godard’s Innovative Filmmaking Through Five Video Essays

A Complete Collection of Wes Anderson Video Essays

Four Video Essays Explain the Mastery of Filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami (RIP)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer , the video series The City in Cinema , the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? , and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog . Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Faceboo k .

by Colin Marshall | Permalink | Comments (1) |

Related posts:

Comments (1), 1 comment so far.

This is still not all of it. Even though there are 9 video essays, most of them focus on the same areas. What about the story? The duplicity of the characters? The common red/blue scenareos?

I’d like to see something about the script of his movies, and how the internal structure of it is built. 2 separate stories overlapped in the same. Can both original stories be separated? Is that even important?

I think Lynch is a perfect example of how form is content.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft