Case Examples

Examples of recommended interventions in the treatment of depression across the lifespan.

Children/Adolescents

A 15-year-old Puerto Rican female

The adolescent was previously diagnosed with major depressive disorder and treated intermittently with supportive psychotherapy and antidepressants. Her more recent episodes related to her parents’ marital problems and her academic/social difficulties at school. She was treated using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Chafey, M.I.J., Bernal, G., & Rossello, J. (2009). Clinical Case Study: CBT for Depression in A Puerto Rican Adolescent. Challenges and Variability in Treatment Response. Depression and Anxiety , 26, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20457

Sam, a 15-year-old adolescent

Sam was team captain of his soccer team, but an unexpected fight with another teammate prompted his parents to meet with a clinical psychologist. Sam was diagnosed with major depressive disorder after showing an increase in symptoms over the previous three months. Several recent challenges in his family and romantic life led the therapist to recommend interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A).

Hall, E.B., & Mufson, L. (2009). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A): A Case Illustration. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38 (4), 582-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410902976338

© Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA, https://sccap53.org/, reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA.

General Adults

Mark, a 43-year-old male

Mark had a history of depression and sought treatment after his second marriage ended. His depression was characterized as being “controlled by a pattern of interpersonal avoidance.” The behavior/activation therapist asked Mark to complete an activity record to help steer the treatment sessions.

Dimidjian, S., Martell, C.R., Addis, M.E., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2008). Chapter 8: Behavioral activation for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 343-362). New York: Guilford Press.

Reprinted with permission from Guilford Press.

Denise, a 59-year-old widow

Denise is described as having “nonchronic depression” which appeared most recently at the onset of her husband’s diagnosis with brain cancer. Her symptoms were loneliness, difficulty coping with daily life, and sadness. Treatment included filling out a weekly activity log and identifying/reconstructing automatic thoughts.

Young, J.E., Rygh, J.L., Weinberger, A.D., & Beck, A.T. (2008). Chapter 6: Cognitive therapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 278-287). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Nancy, a 25-year-old single, white female

Nancy described herself as being “trapped by her relationships.” Her intake interview confirmed symptoms of major depressive disorder and the clinician recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Persons, J.B., Davidson, J. & Tompkins, M.A. (2001). A Case Example: Nancy. In Essential Components of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy For Depression (pp. 205-242). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10389-007

While APA owns the rights to this text, some exhibits are property of the San Francisco Bay Area Center for Cognitive Therapy, which has granted the APA permission for use.

Luke, a 34-year-old male graduate student

Luke is described as having treatment-resistant depression and while not suicidal, hoped that a fatal illness would take his life or that he would just disappear. His treatment involved mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which helps participants become aware of and recharacterize their overwhelming negative thoughts. It involves regular practice of mindfulness techniques and exercises as one component of therapy.

Sipe, W.E.B., & Eisendrath, S.J. (2014). Chapter 3 — Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy For Treatment-Resistant Depression. In R.A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches (2nd ed., pp. 66-70). San Diego: Academic Press.

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Sara, a 35-year-old married female

Sara was referred to treatment after having a stillbirth. Sara showed symptoms of grief, or complicated bereavement, and was diagnosed with major depression, recurrent. The clinician recommended interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for a duration of 12 weeks.

Bleiberg, K.L., & Markowitz, J.C. (2008). Chapter 7: Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 315-323). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Peggy, a 52-year-old white, Italian-American widow

Peggy had a history of chronic depression, which flared during her husband’s illness and ultimate death. Guilt was a driving factor of her depressive symptoms, which lasted six months after his death. The clinician treated Peggy with psychodynamic therapy over a period of two years.

Bishop, J., & Lane , R.C. (2003). Psychodynamic Treatment of a Case of Grief Superimposed On Melancholia. Clinical Case Studies , 2(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650102239085

Several case examples of supportive therapy

Winston, A., Rosenthal, R.N., & Pinsker, H. (2004). Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing.

Older Adults

Several case examples of interpersonal psychotherapy & pharmacotherapy

Miller, M. D., Wolfson, L., Frank, E., Cornes, C., Silberman, R., Ehrenpreis, L.…Reynolds, C. F., III. (1998). Using Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) in a Combined Psychotherapy/Medication Research Protocol with Depressed Elders: A Descriptive Report With Case Vignettes. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research , 7(1), 47-55.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Healthcare (Basel)

Emotions, Feelings, and Experiences of Social Workers While Attending to Vulnerable Groups: A Qualitative Approach

María dolores ruiz-fernández.

1 Department of Nursing, Physiotherapy and Medicine, University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain; se.lau@757frm (M.D.R.-F.); moc.liamg@iicor92 (R.O.-A.); [email protected] (J.M.H.-P.); se.lau@nanrefc (C.F.-S.)

Rocío Ortiz-Amo

Elena andina-díaz.

2 Department of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of León, 24071 León, Spain

3 SALBIS Research Group, University of León, 24071 León, Spain

4 EYCC Research Group, University of Alicante, 03690 Alicante, Spain

Isabel María Fernández-Medina

José manuel hernández-padilla.

5 Adult, Child and Midwifery Department, School of Health and Education, Middlesex University, London NW4 4BT, UK

Cayetano Fernández-Sola

6 Faculty of Health Sciences, University Autónoma of Chile, Temuco 3580000, Chile

Ángela María Ortega-Galán

7 Department of Nursing, University of Huelva, 21007 Huelva, Spain; moc.liamg@69agetroalegna

Associated Data

Not applicable.

Social workers in the community setting are in constant contact with the suffering experienced by the most vulnerable individual. Social interventions are complex and affect social workers’ emotional well-being. The aim of this study was to identify the emotions, feelings, and experiences social workers have while attending to individuals in situations of vulnerability and hardship. A qualitative methodology based on hermeneutic phenomenology was used. Six interviews and two focus group sessions were conducted with social workers from the community social services and health services of the Andalusian Public Health System in the province of Almería (Spain). Atlas.ti 8.0 software was used for discourse analysis. The professionals highlighted the vulnerability of certain groups, such as the elderly and minors, people with serious mental problems, and people with scarce or no economic resources. Daily contact with situations of suffering generates a variety of feelings and emotions (anger, sadness, fear, concern). Therefore, more attention should be paid to working with the emotions of social workers who are exposed to tense and threatening situations. Peer support, talking, and discussions of experiences are pointed out as relevant by all social workers. Receiving training and support (in formal settings) in order to learn how to deal with vulnerable groups could be positive for their work and their professional and personal quality of life.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), vulnerability is the degree to which a population, individual, or organization is unable to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from the impacts of disasters [ 1 ]. The concept of vulnerability refers to those sectors or groups of the population that, due to their age, sex, marital status, or ethnic origin, are in a risky condition that prevents them from accessing development and better welfare conditions [ 2 ]. These people are suffering or undergoing a painful experience [ 3 ] and turn to social services for a solution [ 4 , 5 ]. The care they receive may come from community social services [ 6 ] or, more specifically, from integrated social services in the health field [ 7 ].

Social workers are the frontline professionals of social services [ 8 ], that is, the first professionals in charge of meeting the demands of users upon arrival at care services [ 9 ]. They therefore play a fundamental role in the care trajectory of individuals in situations of need and social vulnerability [ 10 ].

The number of service users with very complex demands is quite high [ 11 ]. As a result, in daily practice, social work professionals find themselves in constant contact with individuals who are experiencing considerable social challenges [ 12 , 13 ]. Professionals are confronted with the task of promoting equality and well-being for individuals [ 14 ]. However, the interventions carried out with users are based on the traditional social intervention model of social services [ 15 ]. This strategy provides material and/or financial resources to users, which could help them to escape from that particular situation [ 16 ]. In this case, this means that the actual implementation of this model would be carried out to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the resources available to the state in question [ 17 ].

Professionals witness the suffering and despair of those most in need [ 18 , 19 ]. This situation triggers professionals’ emotions and feelings, the first being understood as the automatic and uncontrollable response to a stimulus and the feelings being the conscious evaluation of the emotion or experience suffered by the individual [ 20 ]. It is quite common that the demands made are greater than the resources available to manage them or that they need to be met faster than is possible due to the administrative procedures involved [ 21 ]. In addition, the vulnerability of some groups must be added to this context [ 22 ]. According to WHO, children, the elderly, and people who are ill are particularly vulnerable. Poverty is a major contributor to vulnerability [ 23 ]. In this sense, different studies establish that minors and the elderly are among the most vulnerable populations [ 24 ]. Thus, the occupational and professional commitment to these groups of individuals becomes even greater [ 25 ].

These repeated working conditions, alongside the contact with the person’s suffering, have repercussions on the professionals’ well-being [ 26 , 27 , 28 ], causing stress, emotional discomfort, and even vicarious trauma, defined as “those emotions and behaviours resulting from the interaction with traumatic events experienced by others” [ 29 , 30 ]. This is known as the cost of the emotional impact of caring [ 31 , 32 ], that is, the price professionals pay in the process of helping people in situations of intense suffering or trauma. According to the stress process models, some of the resources that potentially serve as a protective barrier include social support, the repertoire of confrontations, and some self-concepts such as self-esteem [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. Other protective resources with the ability to significantly reduce the harmful consequences of existing stressors are the mastery and control of existing circumstances and mutual support among the professionals themselves [ 36 , 37 ].

According to the reviewed literature, research on social work has traditionally focused on professional performance and how this performance affects intervention subjects. However, there are fewer studies on the impact that the suffering of users has on social workers [ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. In recent years, there has been an increase in research, from a quantitative paradigm, in order to describe the working conditions of this group of professionals and their professional needs [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Despite this, research from a qualitative paradigm, from the perspective of social workers themselves, is still scarce. In particular, it reflects the emotional situation they experience in the development of their work, and seeks to delve into the experiences, the consequences, and what they would need, in order to continue helping in a sustainable way [ 45 , 46 , 47 ].

Bearing this in mind, the main objective of this research was to identify the social workers’ emotions, feelings, and experiences while attending to individuals in situations of vulnerability and hardship. Specifically, two secondary objectives were raised: to learn about the situations causing discomfort and suffering, as well as about the consequences of the same on the social workers themselves, and to inquire about the needs and resources of professionals so as to meet the demands of their work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. approach.

In the present study, a qualitative design based on a phenomenological–hermeneutic approach was used. According to Van Manen [ 48 ], this approach allows the study of non-conceptualized experiences lived by people, as well as the meaning of these experiences. Thus, it was possible to perform an in-depth analysis of the daily work experiences of social workers in community social services and health services. Their feelings and perceptions about the implementation of social interventions involving vulnerable groups of individuals were explored and interpreted.

2.2. Recruitment and Sampling

Participants in the study were the social workers at the community social services and health services of the Andalusian Public Health System in the province of Almería (Spain). Community social services in Andalusia are distributed as follows: In the capitals and cities of more than 20,000 inhabitants, the municipalities carry out the management of these services. In cities with less than 20,000 inhabitants, the provincial council carries out the management. Specifically, in Almeria city, there are 4 community social services centers managed by the city council. Regarding the Andalusian Health Service, in the capital city of Almería, there are 13 health centers (6 of these are centers with a full-time social worker). We selected social workers employed at three community social services centers in Almeria and social workers employed at the six health centers.

A total of 20 social workers participated. Of these, 11 worked in community social services centers and 9 worked in the Andalusian Health Service.

The inclusion criteria were the following: holding a stable position as a social work professional in community social services and/or the Andalusian Health Service, having a professional career or experience of no less than eight years, and regularly providing assistance to individuals in need of social services. The following professionals were excluded: professionals with temporary employment contracts or little work experience (less than eight years), professionals in managerial positions, professionals who had no contact with people in vulnerable situations, and professionals who had any psychological impairment that made it difficult for them to provide information.

Convenience sampling was the sampling method used. To recruit as many participants as possible, a snowball sampling procedure was used: a professional was contacted, who, in turn, would contact other professionals willing to participate [ 49 ]. First, the director of an urban community social services center was contacted by telephone. The study was explained to her, and a brief summary of the study, along with authorization from the Ethics and Research Commission, was sent to her via email. Subsequently, the director of the center informed her colleagues of the study and invited them to participate. Finally, the director contacted other directors of other centers, who then followed the same procedure.

The social workers at the health centers were contacted by a mental health social worker and a case manager nurse working at an urban health center. Both professionals were responsible for providing the health and social care workers with information about the study. Once they agreed to participate in the research, the participants were contacted to arrange a meeting.

When selecting participants, gender diversity was sought, although there were few male social workers among the centers’ staff. In Spain, the social work profession is predominantly female, so the sample (a larger number of women) could be considered representative. Equal representation of health and community social workers was also sought.

2.3. Data Collection

In-depth interviews and focus groups were the information-gathering techniques used. Two focus group sessions (with a total of seven people in each group) and six in-depth interviews were carried out. The two focus groups were conducted by a researcher and a collaborator, who had received specific training by specialists. The discourses were taped for transcription.

First, two focus group sessions were held in February 2019. One focus group session was held in the meeting room of an urban community social services center, and the other focus group was held in the multipurpose room of a social services center in the province of Almería (Spain). The groups comprised professionals working in both services (community and health services) to ensure that professionals from both sectors were included in each focus group. The researcher led the group, while the collaborator wrote down in a field notebook those observations that could be useful in subsequent analysis. The session began with an exercise that prompted discussion and dialogue among the members of the group: “Describe your day-to-day work experiences with individuals in vulnerable situations.” Finally, the conclusions were summarized, and the members were thanked for their participation. Each session lasted approximately 90 min.

Second, in-depth interviews were conducted by the researcher of this study in the professionals’ offices. Three interviews were undertaken with community services social workers and a further three with health and social care workers during the month of March 2019. None of them had participated before in the focus groups. In these interviews, those dimensions that had not been sufficiently explored in the focus groups were addressed. A list of interview questions was not used. Only an opening question was asked: “Tell me about your daily work. How does attending to individuals in situations of vulnerability on a daily basis affect you?” This question facilitated the participants’ discussion. The interviewer took all the necessary notes in a field notebook. The interviews lasted approximately one hour.

In the opinion of the researchers, the two focus groups and the six in-depth interviews were sufficient to achieve data saturation. The possibility of conducting one focus group session in the urban area and the other in a rural municipality was considered in order to identify the differences between community social services in the capital of the province and community social services in a rural setting. Furthermore, both focus groups included not only community social services professionals but also health services professionals in order to have discourses from both types of workers in the two settings studied. Once the focus group sessions were completed, in-depth interviews were conducted to investigate the emerging issues in the focus groups in order to obtain additional data.

2.4. Analysis

Giorgi’s method of analysis [ 50 ], which involves creating a series of categories and subcategories, was used to analyze the information from both the in-depth interviews and the focus groups. This procedure was carried out in several phases. The first one was an in-depth reading of all the discourses, which had already been transcribed verbatim. The second phase involved a second reading and the division of the data into parts. The basis of the division into parts is meaning discrimination, which presupposes the prior assumption of a disciplinary perspective (social work, in this case). These meaning discriminations constitute parts known as meaning units. The meaning units were examined, tested, and redefined so that the disciplinary value of each unit could be more explicit. These meaning units were then grouped into broader categories according to their shared characteristics and the disciplinary value. In the last phase, the contents of each of the categories were interpreted and analyzed based on the phenomenon or experience lived.

The theoretical–methodological approach was adequate to achieve the objectives of the study. The data obtained were relevant in the context and in other contexts, when compared to the literature.

As for the validity of the results of the analysis, contrast through triangulation was used to control for potential biases resulting from the heterogeneity of the data and the informants’ different points of view. To make a contrast between the differences and similarities conveyed in the discourses, the techniques of focus groups and in-depth interviews were used. In terms of triangulation between subjects, informants were selected from different settings and fields of work to diversify the information present in the discourses regarding the participants’ work experiences in these services. Two researchers began the analysis after the first interview in order to constantly verify that it was in line with the study’s objectives and in order to be prepared in case any change in the research design was needed (it was not). The main categories that researchers identified in the analysis were shared with the participants (by email) to confirm the discourses. In the participants’ discourses where contradictory information was detected, this moment was used to clarify it. The analysis was shared with the rest of the team to ratify the categories. At the same time, an external researcher (with expertise in the subject) validated the analysis.

Reflexivity and a self-critical attitude were maintained throughout the process by all the researchers. To avoid influencing data collection, sample recruitment, and location, the researchers only knew the topic in a superficial manner (as health professionals) and it was not their usual work/subject matter of research.

Atlas.ti 8.0 software (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used to analyze the discourses.

2.5. Ethical Aspects

This research obtained all the necessary authorization from the corresponding Research and Ethics Committee of the University of Almería, Spain (EFM-11/19). Previously, participants had been informed verbally and in writing of the purpose of the study, and their informed consent had been obtained in writing in a dedicated document. The confidentiality and anonymity of participants were preserved throughout this research, in compliance with the bioethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [ 51 ]. The data from the discourses were safeguarded and protected in accordance with the Spanish regulations in force regarding the official protection of personal data, i.e., the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, of the 5th of December, on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights [ 52 ].

The study population comprised 20 professionals: 11 professionals working in community social services and 9 professionals working in the Andalusian Health Service, with a mean age of 46.35 (SD = 7.36) years and with a mean work experience of 24.16 (SD = 7.87) years. Table 1 shows a summary of the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample of professionals who participated in this research.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants.

| Variables | Focus Group ( = 14) | In-Depth Interviews ( = 6) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 12 | 6 |

| Male | 2 | - |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 10 | 5 |

| Single | 3 | 1 |

| Others | 1 | - |

| Work experience (years) | - | |

| 10–20 | 1 | 1 |

| 20–30 | 3 | 5 |

| 30–40 | 9 | 1 |

| >40 | 1 | |

| Area of work | ||

| Community Services | 8 | 3 |

| Health Services | 6 | 3 |

An analysis of the discourses was performed with the information gathered from the focus groups (FGs) and from the in-depth interviews (IDIs). Three categories with nine subcategories emerged from this analysis. All categories and subcategories were encompassed by a broader category relating to the social workers’ experience ( Table 2 ).

Categories and subcategories emerging from the study.

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Working with vulnerable groups | |

| Emotions emerging from working with vulnerable groups | |

| Need for spaces for self-care |

3.1. Working with Vulnerable Groups

In day-to-day practice, health and social care workers serve users with very different demands. The characteristics of the population visited by social services are highly varied. Certain settings and realities experienced by users are perceived by social workers as generators of further personal suffering or dismay. Moreover, the traditional social intervention model adopted by social services causes chronic frustration and professional burnout. The main element identified by the informants as a generator of further suffering in the person of the social worker was the intervention work carried out with vulnerable groups.

3.1.1. Minors and the Elderly

Two of the vulnerable groups that had an impact on participants were minors and the elderly, as they are fragile and innocent groups.

You can’t avoid being touched by the toughest situations, such as those involving minors or the elderly [who are] on their own… (IDIs, P3).

…then, well, that… what I always say when there are cases and cases, when you see the despair of a daughter because her mother is ill and the resources she needs do not arrive… There are cases that have an impact, and that no matter how professional you are, you can’t help it, of course not! Because I’m also a person… (FGs1, P11).

My weak point, so to speak, is the elderly, especially those who are alone… Many needs arise, and sometimes they cannot be met, and I cannot help but take work home with me… (FGs2, P17).

There are users who inevitably impact your situation, or groups such as minors who are still fragile and innocent… And, you find cases where these minors have a rather difficult context and that touches your heart… (IDIs, P5).

3.1.2. People with Serious Mental Problems

Another group mentioned by participants was people with serious mental problems. The fact of thinking that nobody understands them, that nobody believes them, that they are in danger, that they feel threatened, generates a lot of suffering.

…above all, patients with serious mental disorders, when they’re having delusions and hallucinations… and it’s so upsetting to think that nobody understands them, that nobody believes them, that they are in danger, that they feel threatened, and that causes me a lot of suffering, and to that, we must add the social aspect, when they see that the life project they had just like everybody else, their dreams… all is shattered… (IDIs, P5).

3.1.3. People with Scarce or a Lack of Economic Resources

There are also situations of poverty that become permanent for some people and that professionals attend to repeatedly. People with scarce or a lack of economic resources find themselves in very complex situations, and figuring out a way out of these situations has become almost impossible for them, so they visit social workers in a state of desperation, seeking help.

…these are people who come to my office in great distress because they don’t have the most basic things to eat. I mean, they can’t even pay for water [bills]; they can’t afford the most basic items. Besides, these are chronic situations; they no longer know how to get out of that labyrinth (IDIs, P3).

There are families with real hardships; they do not even have a snack for their children to eat at school, and they’ve had it for a long time, and that distresses them so much that they come looking for you again and again… (FGs1, P9).

We have many users who are poor, but really poor; they do not even have the most basic needs covered… (IDIs, P4).

The fight against poverty that leads to social exclusion must be prioritized. We have seen families with children, families who have suffered evictions, people who have reached a situation of poverty without the possibility of any intervention, and who are constantly visiting you out of desperation… (FGs2, P20).

3.2. Emotions Emerging from Working with Vulnerable Groups

Daily contact with situations of suffering can generate a variety of feelings and emotions among health and social care workers. The need arising in professionals to help users who find themselves in a complex situation is evident. However, sometimes social workers encounter a different reality, and aid does not arrive as expected, thus generating various emotions in them.

The most common emotions expressed by professionals, when facing users’ serious situations or when the outcome is not as expected, included anger, sadness, fear, and concern.

3.2.1. Anger

In relation to anger, participants commented on how seeing injustice, because things are not done as they should be, for example, made them feel helpless, and that helplessness generates anger.

…and many times, you feel angry and helpless; of course you feel that [way], and whoever says they don’t is lying, because we [usually] see very tough situations… (FGs2, P14).

…sometimes I get angry; other times I get sad… It’s a constant state of alertness. That’s my natural state, [and it has been] for some time now (FGs1, P12).

When you see injustice, I feel tremendous anger; it makes me very angry that things are not done as they should… or that the response to a user is not what he needs (IDIs, P6).

There are days when you get very angry or upset about certain situations that we have to deal with… (IDIs, P2).

3.2.2. Sadness

The fact of witnessing difficult times that other people go through, or the despair they experience, generates sadness in social workers.

…I feel like… how can I put it into words?… in a pyramid of dissatisfaction, in the sense that, you know, although you do everything you can, [you see] the outcome in the very long term, and then, in the meantime, you see those people here every day… (IDIs, P2).

…other times I have feelings of sadness… (FGs2, P19).

It is inevitable to feel sad on many occasions, when users are desperate and the answers do not come… (IDIs, P1).

Sometimes there are cases, people, who are in a difficult moment of their lives, and when they share their story with you, you feel a lot of sadness, although you cannot transmit it to them, but inside, you get sad… (FSs2, P18).

3.2.3. Fear

In some cases, some participants even mentioned the word “fear,” although they did not delve into that emotion.

…powerlessness, frustration, or even fear… (FGs2, P17).

…and so, it scares me… (FGs2, P15)

There are situations where you feel fear… (IDIs, P3)

3.2.4. Concern

Social workers disclosed that there are situations they cannot possibly stop thinking about, such as people who find themselves in very serious circumstances. These are extraordinary cases that social workers keep thinking about, even after their working hours, because, according to their accounts, some issues inevitably haunt them owing to their significance or complexity. The emotion that emerged related to this was concern about the problems of the users.

…but there are times and situations, quite exceptional ones, that I can’t help remembering; you definitely remember them… There are situations that I still do take home with me, although I’ve been [working this job] for many years, and you have to learn not to take [these situations] with you. Two, three…? or more [of these situations] a year, at least (FGs1, P13).

I guess situations stop shocking you with the passage of time, or you see it differently… But that does not mean that there are no cases that do not affect me, or that I [don’t] take them home, flitting around in my head… and you mull over them, or even after some time, you would remember that nothing could be done, you see that family member on the street and you remember. There are always situations that affect you…I don’t know… (IDIs, P1).

…I take problems home with me because [first] we’re people and then we’re professionals, and you’re there [trying to] figure out how to solve that situation… (FGs 1, P12).

Social workers identify the need and the urgency of some situations for some vulnerable groups. Not being able to respond adequately, because sometimes resolving a demand takes time, generates discomfort and concern among professionals.

…although you do everything you can, [you see] the outcome in the very long term… (IDIs, P2).

…when urgent cases arise and you can’t resolve them with the same urgency…you go home thinking “[hopefully] nothing [bad] happens by tomorrow,” and, well, you don’t even know if that’ll be resolved the next day (FGs2, P20).

…and when the user leaves, I think, what if by the time it’s resolved it’s too late…? And I know it’s not my fault, but I’m the one who’s facing the music… (FGs 2, P18).

…because I have cases [i.e., users] that you attend to and you tell them, “Come back tomorrow to finish this,” or that they have to wait for such-and-such… (FGs2, P18).

3.3. Need for Spaces for Self-Care

Health and social care workers recognized that working with vulnerable groups causes them many negative emotions, as we have previously described. They said that they feel the need to express and share those feelings.

3.3.1. Mutual Support

They end up developing more informal strategies, such as mutual support. Sharing complex cases and learning from the experience of other professionals and their way of dealing with different situations are two of the most valued strategies according to the discourses. Peer support, talking, and discussions of experiences are highlighted and widely accepted by all social workers. They agree that talking to peers and team support are essential to address certain cases or avoid being affected by them in one way or another. Sharing experiences with peers who have undergone similar situations is described as an informal therapy that social workers use to cope with daily work.

…we support each other here and help each other quite a lot; the director is always there… and that makes a big difference. Maybe peer support is a useful tool to deal with the most vulnerable situations, or so that the most complex cases don’t affect you that much (IDIs, P6).

…[having a] good relationship with my peers always helps; for me that’s my therapy (FGs2, P15).

Sharing experiences with colleagues is a mechanism that comes in handy so as to manage all these situations of frustration or in order to consider what [other] alternatives may exist, in addition to the ones you already know (IDIs, P4).

…we are like a kind of group therapy, and [I have] wonderful colleagues; we support each other, really, at least in my experience (FGs 2, P13).

If there is a case that worries me, she always asks me the first one, always, and I feel very supported. Also, in this office, [which] is shared with another colleague, if you arrive from a bad day, especially tired from so many kilometers, we can share how the day has gone and we can let off steam between us (IDIs, P4).

The truth is that relationships with colleagues are very good, and you find support, and of course that matters; just talking and venting our feelings already help (IDIs, P1).

…I have colleagues who may have [many] more years of experience or who have already undergone a similar case and similar experiences. It’s always good that they give you, like, their insight (FGs1, P12).

3.3.2. Formal Spaces to Work Emotions

Professionals talk about the benefits of peer support and report that it exists and is real. However, they also emphatically express the need for training and support in formal settings to learn how to deal with certain cases or not to bring those situations to their personal lives. They recognize the need to develop other types of skills to help them manage their own suffering and dissatisfaction in structured spaces dedicated to training, and emotional support. Receiving training and support in formal spaces can be positive. Working with emotions could favor their work and their professional and personal quality of life. Informants demand that social workers be cared for so that their work, which is in contact with suffering, is sustainable, without becoming exhausted or burned out.

…from the upper management, they have to think about the professionals; we lack the tools to face the current situations we are experiencing… (FGs2, P15).

Yeah, why not? Spaces to work on emotional education or other types of therapies and teachings so as to care for professionals, [and] formal spaces to talk to peers. These can be things that greatly facilitate and favor the work of social workers and their professional and personal quality of life. Psychologists and others to be within our reach… All professionals need their own space, and I think that in the long run it may prove useful, so why not? (IDIs, P1).

I believe that emotional education and self-care must be present… emotional education must always be present, on a professional and [a] personal level. Spaces where we can formally work with our colleagues… (FGs2, P12).

…maybe it would be good to have a structured space for the self-care of professionals (FGs1, P13).

A space to take care of oneself would be great, spending time with each other while learning to work with emotions (IDIs, P5).

4. Discussion

Social workers constantly provide care to people in vulnerable situations with complex demands. This scenario causes suffering in professionals.

In the literature consulted, social workers are portrayed as resource providers [ 17 ], that is, as mere intermediaries between the group of individuals with needs and the resources that the state decides to allocate. As a result, neither deadlines nor requirements depend on social workers themselves [ 53 ]. The professionals in our study and those in previous studies [ 54 ] agree that the bureaucratic processes faced by users represent obstacles for social workers as well, who have the feeling of not stepping in on time.

Social services users are very varied. The needs of each individual are different, and not all of these needs are equally demanding [ 9 ]. Among the plethora of cases, some groups are more vulnerable than others [ 38 ]. In concordance with our research, other studies have also shown that minors and the elderly are considered to be among the most vulnerable populations [ 24 ]. In addition, health and social care workers point out that individuals with mental illnesses [ 22 ] and individuals who are in a chronic situation from which they cannot get out are groups at greater risk [ 55 , 56 ].

As shown in this research, the emotions generated in professionals who are in constant contact with situations of suffering with a high emotional impact, such as the aforementioned, originate deep frustration, anger, and dissatisfaction, as well as sadness, fear, and concern. This is in consonance with the literature consulted, which also reports the great effect that working daily with the intense suffering of users has on social workers, along with a potentially poor response [ 26 , 27 , 57 , 58 ]. In fact, some studies conceptualize emotion as both a potential resource and a risk for social workers’ professional judgment and practice [ 59 ].

The social workers in our study considered that the most complex interventions with vulnerable people inevitably make it difficult for them to switch off from work. This aspect is consistent with other studies in which social workers had difficulties when switching off from work after attending to groups with complicated needs [ 55 , 60 ]. With regard to the reported resources for self-care, mutual support is virtually the only helping tool available to these professionals. In previous studies, professionals referred to social support as a key element [ 13 , 27 , 43 ] but did not specifically mention mutual peer support. Social workers ask for training and support in the face of complex social interventions, as proposed by different research studies that underline the importance of taking care, preparing, training, and supporting social workers in this regard [ 61 , 62 ]. Therefore, more attention should be paid to working with the emotions of social workers who are exposed to tense and threatening situations [ 63 , 64 ]. In this way, for instance, reflexivity strategies in order to build and rebuild emotions in social workers could be useful [ 65 ]. Receiving training and support in formal spaces, as social workers described in this study, could be positive for their work and their professional and personal quality of life.

As for the limitations of this study, we considered the possibility that the researchers’ personal positions on the matter may have introduced bias into the results. To control for bias, reflexivity and a self-critical attitude were maintained throughout the process by all the researchers. To avoid influencing data collection, sample recruitment, and location, the researchers only knew the topic in a superficial manner (as health professionals) and it was not their usual work/subject matter of research. We relied on the ultimate motivation for our work, which is to acquire knowledge to improve, rather than to demonstrate. Nevertheless, we have set out to conduct a release exercise to clarify our own assumptions and put them into perspective when designing our research.

Regarding future lines of research, a study with the methods combined regarding the quality of professional life of social workers should be conducted in order to identify related factors and to assess the levels of compassion fatigue. In addition, research should be undertaken on the concept of compassion among social workers and its relationship to suffering. Finally, interventions should be carried out with social work professionals to develop compassion as a protective element against compassion fatigue.

5. Conclusions

Social workers experience high levels of emotional discomfort when carrying out their work, which is exacerbated when the populations they attend to are particularly vulnerable groups, such as children, the elderly, individuals with mental health problems, or people with scarce or a lack of economic resources. The traditional hegemonic intervention model that lies within the structure of social services in this context results in all social work efforts revolving around the allocation of available resources, which are generally scarce. All aspects of the individual have been eliminated from the repertoire of interventions according to the comprehensive support approach. In this new model of care, based mainly on providing support to individuals, the professionals themselves are the main tools and resources. In the future, this will further enhance the role of social workers when supporting people experiencing social exclusion, poverty, and marginalization. More attention should be paid to working with the emotions of social workers who are exposed to tense and threatening situations. Peer support, talking, and discussions of experiences are highlighted as relevant to deal with their work. Receiving training and support (in formal spaces) in order to learn how to deal with vulnerable groups could be positive for their work and their professional and personal quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Health Sciences Research Group CTS-451 and the Health Research Center (CEINSA) of the University of Almería (Spain) for its support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.R.-F., E.A.-D., Á.M.O.-G. and R.O.-A.; methodology, R.O.-A. and E.A.-D.; validation, C.F.-S., I.M.F.-M. and J.M.H.-P.; formal analysis, Á.M.O.-G.; investigation, R.O.-A.; data curation, M.D.R.-F. and R.O.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, Á.M.O.-G. and R.O.-A.; writing—review and editing, M.D.R.-F. and E.A.-D.; visualization and supervision, C.F.-S., I.M.F.-M. and J.M.H.-P.; and funding acquisition, M.D.R.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by the University of Almería (project TRFE-SI-2019/010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Almería (protocol code EFM-11/19, 11/03/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Social Work Practice with Carers

Case Study 2: Josef

Download the whole case study as a PDF file

Josef is 16 and lives with his mother, Dorota, who was diagnosed with Bipolar disorder seven years ago. Josef was born in England. His parents are Polish and his father sees him infrequently.

This case study looks at the impact of caring for someone with a mental health problem and of being a young carer , in particular the impact on education and future employment .

When you have looked at the materials for the case study and considered these topics, you can use the critical reflection tool and the action planning tool to consider your own practice.

- One-page profile

Support plan

Transcript (.pdf, 48KB)

Name : Josef Mazur

Gender : Male

Ethnicity : White European

Download resource as a PDF file

First language : English/ Polish

Religion : Roman Catholic

Josef lives in a small town with his mother Dorota who is 39. Dorota was diagnosed with Bi-polar disorder seven years ago after she was admitted to hospital. She is currently unable to work. Josef’s father, Stefan, lives in the same town and he sees him every few weeks. Josef was born in England. His parents are Polish and he speaks Polish at home.

Josef is doing a foundation art course at college. Dorota is quite isolated because she often finds it difficult to leave the house. Dorota takes medication and had regular visits from the Community Psychiatric Nurse when she was diagnosed and support from the Community Mental Health team to sort out her finances. Josef does the shopping and collects prescriptions. He also helps with letters and forms because Dorota doesn’t understand all the English. Dorota gets worried when Josef is out. When Dorota is feeling depressed, Josef stays at home with her. When Dorota is heading for a high, she tries to take Josef to do ‘exciting stuff’ as she calls it. She also spends a lot of money and is very restless.

Josef worries about his mother’s moods. He is worried about her not being happy and concerned at the money she spends when she is in a high mood state. Josef struggles to manage his day around his mother’s demands and to sleep when she is high. Josef has not told anyone about the support he gives to his mother. He is embarrassed by some of the things she does and is teased by his friends, and he does not think of himself as a carer. Josef has recently had trouble keeping up with course work and attendance. He has been invited to a meeting with his tutor to formally review attendance and is worried he will get kicked out. Josef has some friends but he doesn’t have anyone he can confide in. His father doesn’t speak to his mother.

Josef sees some information on line about having a parent with a mental health problem. He sends a contact form to ask for information. Someone rings him and he agrees to come into the young carers’ team and talk to the social worker. You have completed the assessment form with Josef in his words and then done a support plan with him.

Back to Summary

Josef Mazur

What others like and admire about me

Good at football

Finished Arkham Asylum on expert level

What is important to me

Mum being well and happy

Seeing my dad

Being an artist

Seeing my friends

How best to support me

Tell me how to help mum better

Don’t talk down to me

Talk to me 1 to 1

Let me know who to contact if I am worried about something

Work out how I can have some time on my own so I can do my college work and see my friends

Don’t tell mum and my friends

Date chronology completed : 7 March 2016

Date chronology shared with person: 7 March 2016

| 1997 | Josef’s mother and father moved to England from Poznan. | Both worked at the warehouse – Father still works there. |

| 11.11.1999 | Josef born. | Mother worked for some of the time that Josef was young. |

| 2006 | Josef reports that his mother and father started arguing about this time because of money and Josef’s mother not looking after household tasks. | Josef started doing household tasks e.g. cleaning, washing and ironing. |

| 2008 | Josef reports that his mother didn’t get out of bed for a few months. | Josef managed the household during this period. |

| October 2008 | Josef reports that his mother spent lots of money in catalogues and didn’t sleep. She was admitted to hospital. | Mother was in hospital for 6 weeks and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Josef began looking after his mother’s medication and says that he started to ‘keep an eye on her.’ |

| May 2010 | Josef’s father moved out to live with his friend Kat. Josef stayed with his mother. | Josef reports that his mother was ‘really sad for a while and then she went round and shouted at them.’ Mother started on different medication and had regular visits from the Community Psychiatric Nurse. Josef said that the CPN told him about his mum’s illness and to let him know if he needed any help but he was managing ok. Josef saw his father every week for a few years and then it was more like every month. Father does not visit Josef or speak to his mother. |

| 2013/14 | Josef reports that his mother got into a lot of debt and they had eviction letters. | Josef’s father paid some of the bills and his mother was referred by the Community Mental Health Team for advice from CAB and started getting benefits. Josef started doing the correspondence. |

| 2015 | Josef left school and went to college. | Josef got an A (art), 4 Cs and 3 Ds GCSE. He says that he ‘would have done better but I didn’t do much work.’ |

| 26 Feb 2016 | Josef got a letter from his tutor at college saying he had to go to a formal review about attendance. | Josef saw information on-line about having a parent with a mental health problem and asked for some information. |

| 2 March 2016 | Phone call from young carer’s team to Josef. | Josef agreed to come in for an assessment. |

| 4 March 2016 | Social worker meets with Josef. | Carer’s assessment and support plan completed. |

| 7 March 2016 | Paperwork completed. | Sent to Josef. |

Young Carers Assessment

Do you look after or care for someone at home?

The questions in this paper are designed to help you think about your caring role and what support you might need to make your life a little easier or help you make time for more fun stuff.

Please feel free to make notes, draw pictures or use the form however is best for you.

What will happen to this booklet?

This is your booklet and it is your way to tell an adult who you trust about your caring at home. This will help you and the adult find ways to make your life and your caring role easier.

The adult who works with you on your booklet might be able to help you with everything you need. If they can’t, they might know other people who can.

Our Agreement

- I will share this booklet with people if I think they can help you or your family

- I will let you know who I share this with, unless I am worried about your safety, about crime or cannot contact you

- Only I or someone from my team will share this booklet

- I will make sure this booklet is stored securely

- Some details from this booklet might be used for monitoring purposes, which is how we check that we are working with everyone we should be

Signed: ___________________________________

Young person:

- I know that this booklet might get shared with other people who can help me and my family so that I don’t have to explain it all over again

- I understand what my worker will do with this booklet and the information in it (written above).

Signed: ____________________________________

Name : Josef Mazur Address : 1 Green Avenue, Churchville, ZZ1 Z11 Telephone: 012345 123456 Email: [email protected] Gender : Male Date of birth : 11.11.1999 Age: 16 School : Green College, Churchville Ethnicity : White European First language : English/ Polish Religion : Baptised Roman Catholic GP : Dr Amp, Hill Surgery

The best way to get in touch with me is:

Do you need any support with communication?

*Josef is bilingual – English and Polish. He speaks English at school and with his friends, and Polish at home. Josef was happy to have this assessment in English, however, another time he may want to have a Polish interpreter. It will be important to ensure that Josef is able to use the words he feels best express himself.

About the person/ people I care for

I look after my mum who has bipolar disorder. Mum doesn’t work and doesn’t really leave the house unless she is heading for a high. When Mum is sad she just stays at home. When she is getting hyper then she wants to do exciting stuff and she spends lots of money and she doesn’t sleep.

Do you wish you knew more about their illness?

Do you live with the person you care for?

What I do as a carer It depends on if my mum has a bad day or not. When she is depressed she likes me to stay home with her and when she is getting hyper then she wants me to go out with her. If she has new meds then I like to be around. Mum doesn’t understand English very well (she is from Poland) so I do all the letters. I help out at home and help her with getting her medication.

Tell us what an average week is like for you, what kind of things do you usually do?

Monday to Friday

Get up, get breakfast, make sure mum has her pills, tell her to get up and remind her if she’s got something to do.

If mum hasn’t been to bed then encourage her to sleep a bit and set an alarm

College – keep phone on in case mum needs to call – she usually does to ask me to get something or check when I’m coming home

Go home – go to shops on the way

Remind mum about tablets, make tea and pudding for both of us as well as cleaning the house and fitting tea in-between, ironing, hoovering, hanging out and bringing in washing

Do college work when mum goes to bed if not too tired

More chores

Do proper shop

Get prescription

See my friends, do college work

Sunday – do paper round

Physical things I do….

(for example cooking, cleaning, medication, shopping, dressing, lifting, carrying, caring in the night, making doctors appointments, bathing, paying bills, caring for brothers & sisters)

I do all the housework and shopping and cooking and get medication

Things I find difficult

Emotional support I provide…. (please tell us about the things you do to support the person you care for with their feelings; this might include, reassuring them, stopping them from getting angry, looking after them if they have been drinking alcohol or taking drugs, keeping an eye on them, helping them to relax)

If mum is stressed I stay with her

If mum is depressed I have to keep things calm and try to lighten the mood

She likes me to be around

When mum is heading for a high wants to go to theme parks or book holidays and we can’t afford it

I worry that mum might end up in hospital again

Mum gets cross if I go out

Other support

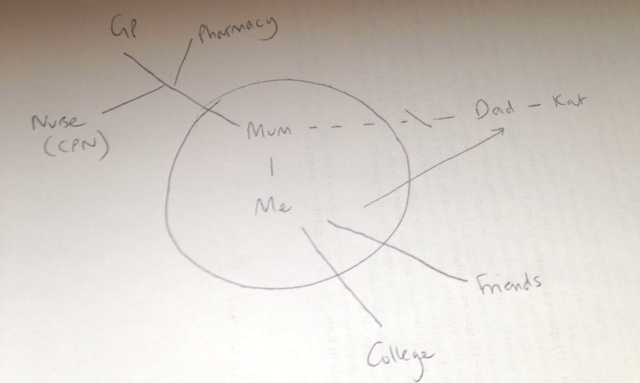

Please tell us about any other support the person you care for already has in place like a doctor or nurse, or other family or friends.

The GP sees mum sometimes. She has a nurse who she can call if things get bad.

Mum’s medication comes from Morrison’s pharmacy.

Dad lives nearby but he doesn’t talk to mum.

Mum doesn’t really have any friends.

Do you ever have to stop the person you care for from trying to harm themselves or others?

Some things I need help with

Sorting out bills and having more time for myself

I would like mum to have more support and to have some friends and things to do

On a normal week, what are the best bits? What do you enjoy the most? (eg, seeing friends, playing sports, your favourite lessons at school)

Seeing friends

When mum is up and smiling

Playing football

On a normal week, what are the worst bits? What do you enjoy the least? (eg cleaning up, particular lessons at school, things you find boring or upsetting)

Nagging mum to get up

Reading letters

Missing class

Mum shouting

Friends laugh because I have to go home but they don’t have to do anything

What things do you like to do in your spare time?

Do you feel you have enough time to spend with your friends or family doing things you enjoy, most weeks?

Do you have enough time for yourself to do the things you enjoy, most weeks? (for example, spending time with friends, hobbies, sports)

Are there things that you would like to do, but can’t because of your role as a carer?

Can you say what some of these things are?

See friends after college

Go out at the weekend

Time to myself at home

It can feel a bit lonely

I’d like my mum to be like a normal mum

School/ College Do you think being your caring role makes school/college more difficult for you in any way?

If you ticked YES, please tell us what things are made difficult and what things might help you.

Things I find difficult at school/ college

Sometimes I get stressed about college and end up doing college work really late at night – I get a bit angry when I’m stressed

I don’t get all my college work done and I miss days

I am tired a lot of the time

Things I need help with…

I am really worried they will kick me out because I am behind and I miss class. I have to meet my tutor about it.

Do your teachers know about your caring role?

Are you happy for your teachers and other staff at school/college to know about your caring role?

Do you think that being a carer will make it more difficult for you to find or keep a job?

Why do you think being a carer is/ will make finding a job more difficult?

I haven’t thought about it. I don’t know if I’ll be able to finish my course and do art and then I won’t be able to be an artist.

Who will look after mum?

What would make it easier for you to find a job after school/college?

Finishing my course

Mum being ok

How I feel about life…

Do you feel confident both in school and outside of school?

Somewhere in the middle

In your life in general, how happy do you feel?

Quite unhappy

In your life in general, how safe do you feel?

How healthy do you feel at the moment?

Quite healthy

Being heard

Do you think people listen to what you are saying and how you are feeling?

If you said no, can you tell us who you feel isn’t listening or understanding you sometimes (eg, you parents, your teachers, your friends, professionals)

I haven’t told anyone

I can’t talk to mum

My friends laugh at me because I don’t go out

Do you think you are included in important decisions about you and your life? (eg, where you live, where you go to school etc)

Do you think that you’re free to make your own choices about what you do and who you spend your time with?

Not often enough

Is there anybody who knows about the caring you’re doing at the moment?

If so, who?

I told dad but he can’t do anything

Would you like someone to talk to?

Supporting me Some things that would make my life easier, help me with my caring or make me feel better

I don’t know

Fix mum’s brain

People to help me if I’m worried and they can do something about it

Not getting kicked out of college

Free time – time on my own to calm down and do work or have time to myself

Time to go out with my friends

Get some friends for mum

I don’t want my mum to get into trouble

Who can I turn to for advice or support?

I would like to be able to talk to someone without mum or friends knowing

Would you like a break from your caring role?

How easy is it to see a Doctor if you need to?

To be used by social care assessors to consider and record measures which can be taken to assist the carer with their caring role to reduce the significant impact of any needs. This should include networks of support, community services and the persons own strengths. To be eligible the carer must have significant difficulty achieving 1 or more outcomes without support; it is the assessors’ professional judgement that unless this need is met there will be a significant impact on the carer’s wellbeing. Social care funding will only be made available to meet eligible outcomes that cannot be met in any other way, i.e. social care funding is only available to meet unmet eligible needs.

Date assessment completed : 7 March 2016

Social care assessor conclusion

Josef provides daily support to his mum, Dorota, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder seven years ago. Josef helps Dorota with managing correspondence, medication and all household tasks including shopping. When Dorota has a low mood, Josef provides support and encouragement to get up. When Dorota has a high mood, Josef helps to calm her and prevent her spending lots of money. Josef reports that Dorota has some input from community health services but there is no other support. Josef’s dad is not involved though Josef sees him sometimes, and there are no friends who can support Dorota.

Josef is a great support to his mum and is a loving son. He wants to make sure his mum is ok. However, caring for his mum is impacting: on Josef’s health because he is tired and stressed; on his emotional wellbeing as he can get angry and anxious; on his relationship with his mother and his friends; and on his education. Josef is at risk of leaving college. Josef wants to be able to support his mum better. He also needs time for himself, to develop and to relax, and to plan his future.

Eligibility decision : Eligible for support

What’s happening next : Create support plan

Completed by Name : Role : Organisation :

Name: Josef Mazur

Address 1 Green Avenue, Churchville, ZZ1 Z11

Telephone 012345 123456

Email [email protected]

Gender: Male

Date of birth: 11.11.1999 Age: 16

School Green College, Churchville

Ethnicity White European

First language English/ Polish

Religion Baptised Roman Catholic

GP Dr Amp, Hill Surgery

My relationship to this person son

Name Dorota Mazur

Gender Female

Date of birth 12.6.79 Age 36

First language Polish

Religion Roman Catholic

Support plan completed by

Organisation

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

Date of support plan: 7 March 2016

This plan will be reviewed on: 7 September 2016

Signing this form

Please ensure you read the statement below in bold, then sign and date the form.

I understand that completing this form will lead to a computer record being made which will be treated confidentially. The council will hold this information for the purpose of providing information, advice and support to meet my needs. To be able to do this the information may be shared with relevant NHS Agencies and providers of carers’ services. This will also help reduce the number of times I am asked for the same information.

If I have given details about someone else, I will make sure that they know about this.

I understand that the information I provide on this form will only be shared as allowed by the Data Protection Act.

Josef has given consent to share this support plan with the CPN but does not want it to be shared with his mum.

Mental health

The social work role with carers in adult mental health services has been described as: intervening and showing professional leadership and skill in situations characterised by high levels of social, family and interpersonal complexity, risk and ambiguity (Allen 2014). Social work with carers of people with mental health needs, is dependent on good practice with the Mental Capacity Act where practitioner knowledge and understanding has been found to be variable (Iliffe et al 2015).

- Carers Trust (2015) Mental Health Act 1983 – Revised Code of Practice Briefing

- Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

- Mind, Talking about mental health

- Tool 1: Triangle of care: self-assessment for mental health professionals – Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England Second Edition (page 23 Self-assessment tool for organisations)

Mental capacity, confidentiality and consent

Social work with carers of people with mental health needs, is dependent on good practice with the Mental Capacity Act where practitioner knowledge and understanding has been found to be variable (Iliffe et al 2015). Research highlights important issues about involvement, consent and confidentiality in working with carers (RiPfA 2016, SCIE 2015, Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland 2013).

- Beddow, A., Cooper, M., Morriss, L., (2015) A CPD curriculum guide for social workers on the application of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 . Department of Health

- Bogg, D. and Chamberlain, S. (2015) Mental Capacity Act 2005 in Practice Learning Materials for Adult Social Workers . Department of Health

- Department of Health (2015) Best Interest Assessor Capabilities , The College of Social Work

- RiPfA Good Decision Making Practitioner Handbook

- SCIE Mental Capacity Act resource

- Tool 2: Making good decisions, capacity tool (page 70-71 in good decision making handbook)

Young carers

A young carer is defined as a person under 18 who provides or intends to provide care for another person. The concept of care includes practical or emotional support. It is the case that this definition excludes children providing care as part of contracted work or as voluntary work. However, the local authority can ignore this and carry out a young carer’s need assessment if they think it would be appropriate. Young carers, young adult carers and their families now have stronger rights to be identified, offered information, receive an assessment and be supported using a whole-family approach (Carers Trust 2015).

- SCIE (2015) Young carer transition in practice under the Care Act 2014

- SCIE (2015) Care Act: Transition from children’s to adult services – early and comprehensive identification

- Carers Trust (2015) Rights for young carers and young adult carers in the Children and Families Act

- Carers Trust (2015) Know your Rights: Support for Young Carers and Young Adult Carers in England

- The Children’s Society (2015) Hidden from view: The experiences of young carers in England

- DfE (2011) Improving support for young carers – family focused approaches

- ADASS and ADCS (2015) No wrong doors: working together to support young carers and their families

- Carers Trust, Supporting Young Carers and their Families: Examples of Practice

- Refugee toolkit webpage: Children and informal interpreting

- SCIE (2010) Supporting carers: the cared for person

- SCIE (2015) Care Act Transition from children’s to adults’ services – Video diaries

- Tool 3: Young carers’ rights – The Children’s Society (2014) The Know Your Rights pack for young carers in England!

- Tool 4: Vision and principles for adults’ and children’s services to work together

Young carers of parents with mental health problems

The Care Act places a duty on local authorities to assess young carers before they turn 18, so that they have the information they need to plan for their future. This is referred to as a transition assessment. Guidance, advocating a whole family approach, is available to social workers (LGA 2015, SCIE 2015, ADASS/ADCS 2011).

- SCIE (2012) At a glance 55: Think child, think parent, think family: Putting it into practice

- SCIE (2008) Research briefing 24: Experiences of children and young people caring for a parent with a mental health problem

- SCIE (2008) SCIE Research briefing 29: Black and minority ethnic parents with mental health problems and their children

- Carers Trust (2015) The Triangle of Care for Young Carers and Young Adult Carers: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals

- ADASS and ADCS (2011) Working together to improve outcomes for young carers in families affected by enduring parental mental illness or substance misuse

- Ofsted (2013) What about the children? Joint working between adult and children’s services when parents or carers have mental ill health and/or drug and alcohol problems

- Mental health foundation (2010) MyCare The challenges facing young carers of parents with a severe mental illness

- Children’s Commissioner (2012) Silent voices: supporting children and young people affected by parental alcohol misuse

- SCIE, Parental mental health and child welfare – a young person’s story

Tool 5: Family model for assessment

- Tool 6: Engaging young carers of parents with mental health problems or substance misuse

Young carers and education/ employment

Transition moments are highlighted in the research across the life course (Blythe 2010, Grant et al 2010). Complex transitions required smooth transfers, adequate support and dedicated professionals (Petch 2010). Understanding transition theory remains essential in social work practice (Crawford and Walker 2010). Partnership building expertise used by practitioners was seen as particular pertinent to transition for a young carer (Heyman 2013).

- TLAP (2013) Making it real for young carers

- Learning and Work Institute (2018) Barriers to employment for young adult carers

- Carers Trust (2014) Young Adult Carers at College and University

- Carers Trust (2013) Young Adult Carers at School: Experiences and Perceptions of Caring and Education

- Carers Trust (2014) Young Adult Carers and Employment

- Family Action (2012) BE BOTHERED! Making Education Count for Young Carers

Download The Triangle of Care as a PDF file

The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

The Triangle of Care is a therapeutic alliance between service user, staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports recovery and sustains wellbeing…

Download the Capacity Tool as a PDF file

Capacity Tool Good decision-making Practitioners’ Handbook

The Capacity tool on page 71 has been developed to take into account the lessons from research and the case CC v KK. In particular:

- that capacity assessors often do not clearly present the available options (especially those they find undesirable) to the person being assessed

- that capacity assessors often do not explore and enable a person’s own understanding and perception of the risks and advantages of different options

- that capacity assessors often do not reflect upon the extent to which their ‘protection imperative’ has influenced an assessment, which may lead them to conclude that a person’s tolerance of risks is evidence of incapacity.

The tool allows you to follow steps to ensure you support people as far as possible to make their own decisions and that you record what you have done.

Download Know your rights as a PDF file

Tool 3: Know Your Rights Young Carers in Focus

This pack aims to make you aware of your rights – your human rights, your legal rights, and your rights to access things like benefits, support and advice.

Need to know where to find things out in a hurry? Our pack has lots of links to useful and interesting resources that can help you – and help raise awareness about young carers’ issues!

Know Your Rights has been produced by Young Carers in Focus (YCiF), and funded by the Big Lottery Fund.

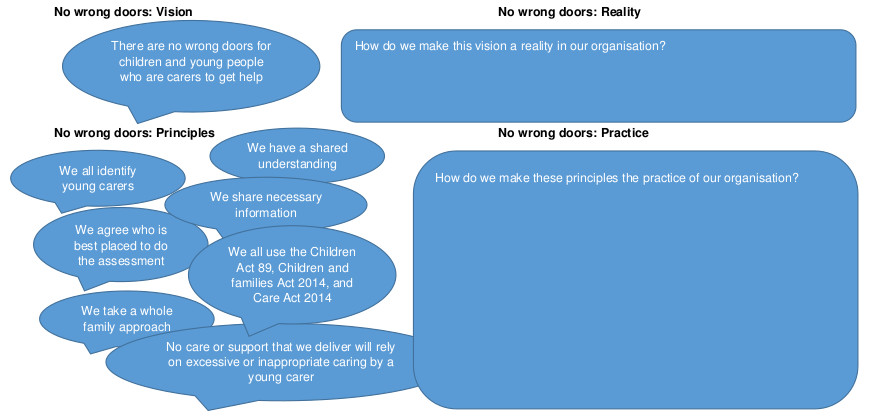

Tool 4: Vision and principles for adults’ and children’s services to work together to support young carers

Download the tool as a PDF file

You can use this tool to consider how well adults’ and children’s services work together, and how to improve this.

Click on the diagram to open full size in a new window

This is based on ADASS and ADCS (2015) No wrong doors : working together to support young carers and their families

Download the tool as a PDF file

You can use this tool to help you consider the whole family in an assessment or review.

What are the risk, stressors and vulnerability factors?

How is the child/ young person’s wellbeing affected?

How is the adult’s wellbeing affected?

What are the protective factors and available resources?

This tool is based on SCIE (2009) Think child, think parent, think family: a guide to parental mental health and child welfare

Tool 6: Engaging young carers

Young carers have told us these ten things are important. So we will do them.

- Introduce yourself. Tell us who you are and what your job is.

- Give us as much information as you can.

- Tell us what is wrong with our parents.

- Tell us what is going to happen next.

- Talk to us and listen to us. Remember it is not hard to speak to us we are not aliens.

- Ask us what we know and what we think. We live with our parents; we know how they have been behaving.

- Tell us it is not our fault. We can feel guilty if our mum or dad is ill. We need to know we are not to blame.

- Please don’t ignore us. Remember we are part of the family and we live there too.

- Keep on talking to us and keeping us informed. We need to know what is happening.

- Tell us if there is anyone we can talk to. Maybe it could be you.

- Equal opportunities

- Complaints procedure

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility

A sample case study: Mrs Brown

On this page, social work report, social work report: background, social work report: social history, social work report: current function, social work report: the current risks, social work report: attempts to trial least restrictive options, social work report: recommendation, medical report, medical report: background information, medical report: financial and legal affairs, medical report: general living circumstances.

This is a fictitious case that has been designed for educative purposes.

Mrs Beryl Brown URN102030 20 Hume Road, Melbourne, 3000 DOB: 01/11/33

Date of application: 20 August 2019

Mrs Beryl Brown (01/11/33) is an 85 year old woman who was admitted to the Hume Hospital by ambulance after being found by her youngest daughter lying in front of her toilet. Her daughter estimates that she may have been on the ground overnight. On admission, Mrs Brown was diagnosed with a right sided stroke, which has left her with moderate weakness in her left arm and leg. A diagnosis of vascular dementia was also made, which is overlaid on a pre-existing diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (2016). Please refer to the attached medical report for further details.