Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

Published on 5 April 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 20 March 2023.

An observational study is used to answer a research question based purely on what the researcher observes. There is no interference or manipulation of the research subjects, and no control and treatment groups .

These studies are often qualitative in nature and can be used for both exploratory and explanatory research purposes. While quantitative observational studies exist, they are less common.

Observational studies are generally used in hard science, medical, and social science fields. This is often due to ethical or practical concerns that prevent the researcher from conducting a traditional experiment . However, the lack of control and treatment groups means that forming inferences is difficult, and there is a risk of confounding variables impacting your analysis.

Table of contents

Types of observation, types of observational studies, observational study example, advantages and disadvantages of observational studies, observational study vs experiment, frequently asked questions.

There are many types of observation, and it can be challenging to tell the difference between them. Here are some of the most common types to help you choose the best one for your observational study.

| The researcher observes how the participants respond to their environment in ‘real-life’ settings but does not influence their behavior in any way | Observing monkeys in a zoo enclosure | |

| Also occurs in ‘real-life’ settings, but here, the researcher immerses themselves in the participant group over a period of time | Spending a few months in a hospital with patients suffering from a particular illness | |

| Utilising coding and a strict observational schedule, researchers observe participants in order to count how often a particular phenomenon occurs | Counting the number of times children laugh in a classroom | |

| Hinges on the fact that the participants do not know they are being observed | Observing interactions in public spaces, like bus rides or parks | |

| Involves counting or numerical data | Observations related to age, weight, or height | |

| Involves ‘five senses’: sight, sound, smell, taste, or hearing | Observations related to colors, sounds, or music | |

| Investigates a person or group of people over time, with the idea that close investigation can later be to other people or groups | Observing a child or group of children over the course of their time in elementary school | |

| Utilises primary sources from libraries, archives, or other repositories to investigate a research question | Analysing US Census data or telephone records |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

There are three main types of observational studies: cohort studies, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies.

Cohort studies

Cohort studies are more longitudinal in nature, as they follow a group of participants over a period of time. Members of the cohort are selected because of a shared characteristic, such as smoking, and they are often observed over a period of years.

Case–control studies

Case–control studies bring together two groups, a case study group and a control group . The case study group has a particular attribute while the control group does not. The two groups are then compared, to see if the case group exhibits a particular characteristic more than the control group.

For example, if you compared smokers (the case study group) with non-smokers (the control group), you could observe whether the smokers had more instances of lung disease than the non-smokers.

Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies analyse a population of study at a specific point in time.

This often involves narrowing previously collected data to one point in time to test the prevalence of a theory—for example, analysing how many people were diagnosed with lung disease in March of a given year. It can also be a one-time observation, such as spending one day in the lung disease wing of a hospital.

Observational studies are usually quite straightforward to design and conduct. Sometimes all you need is a notebook and pen! As you design your study, you can follow these steps.

Step 1: Identify your research topic and objectives

The first step is to determine what you’re interested in observing and why. Observational studies are a great fit if you are unable to do an experiment for ethical or practical reasons, or if your research topic hinges on natural behaviors.

Step 2: Choose your observation type and technique

In terms of technique, there are a few things to consider:

- Are you determining what you want to observe beforehand, or going in open-minded?

- Is there another research method that would make sense in tandem with an observational study?

- If yes, make sure you conduct a covert observation.

- If not, think about whether observing from afar or actively participating in your observation is a better fit.

- How can you preempt confounding variables that could impact your analysis?

- You could observe the children playing at the playground in a naturalistic observation.

- You could spend a month at a day care in your town conducting participant observation, immersing yourself in the day-to-day life of the children.

- You could conduct covert observation behind a wall or glass, where the children can’t see you.

Overall, it is crucial to stay organised. Devise a shorthand for your notes, or perhaps design templates that you can fill in. Since these observations occur in real time, you won’t get a second chance with the same data.

Step 3: Set up your observational study

Before conducting your observations, there are a few things to attend to:

- Plan ahead: If you’re interested in day cares, you’ll need to call a few in your area to plan a visit. They may not all allow observation, or consent from parents may be needed, so give yourself enough time to set everything up.

- Determine your note-taking method: Observational studies often rely on note-taking because other methods, like video or audio recording, run the risk of changing participant behavior.

- Get informed consent from your participants (or their parents) if you want to record: Ultimately, even though it may make your analysis easier, the challenges posed by recording participants often make pen-and-paper a better choice.

Step 4: Conduct your observation

After you’ve chosen a type of observation, decided on your technique, and chosen a time and place, it’s time to conduct your observation.

Here, you can split them into case and control groups. The children with siblings have a characteristic you are interested in (siblings), while the children in the control group do not.

When conducting observational studies, be very careful of confounding or ‘lurking’ variables. In the example above, you observed children as they were dropped off, gauging whether or not they were upset. However, there are a variety of other factors that could be at play here (e.g., illness).

Step 5: Analyse your data

After you finish your observation, immediately record your initial thoughts and impressions, as well as follow-up questions or any issues you perceived during the observation. If you audio- or video-recorded your observations, you can transcribe them.

Your analysis can take an inductive or deductive approach :

- If you conducted your observations in a more open-ended way, an inductive approach allows your data to determine your themes.

- If you had specific hypotheses prior to conducting your observations, a deductive approach analyses whether your data confirm those themes or ideas you had previously.

Next, you can conduct your thematic or content analysis . Due to the open-ended nature of observational studies, the best fit is likely thematic analysis.

Step 6: Discuss avenues for future research

Observational studies are generally exploratory in nature, and they often aren’t strong enough to yield standalone conclusions due to their very high susceptibility to observer bias and confounding variables. For this reason, observational studies can only show association, not causation .

If you are excited about the preliminary conclusions you’ve drawn and wish to proceed with your topic, you may need to change to a different research method , such as an experiment.

- Observational studies can provide information about difficult-to-analyse topics in a low-cost, efficient manner.

- They allow you to study subjects that cannot be randomised safely, efficiently, or ethically .

- They are often quite straightforward to conduct, since you just observe participant behavior as it happens or utilise preexisting data.

- They’re often invaluable in informing later, larger-scale clinical trials or experiments.

Disadvantages

- Observational studies struggle to stand on their own as a reliable research method. There is a high risk of observer bias and undetected confounding variables.

- They lack conclusive results, typically are not externally valid or generalisable, and can usually only form a basis for further research.

- They cannot make statements about the safety or efficacy of the intervention or treatment they study, only observe reactions to it. Therefore, they offer less satisfying results than other methods.

The key difference between observational studies and experiments is that a properly conducted observational study will never attempt to influence responses, while experimental designs by definition have some sort of treatment condition applied to a portion of participants.

However, there may be times when it’s impossible, dangerous, or impractical to influence the behavior of your participants. This can be the case in medical studies, where it is unethical or cruel to withhold potentially life-saving intervention, or in longitudinal analyses where you don’t have the ability to follow your group over the course of their lifetime.

An observational study may be the right fit for your research if random assignment of participants to control and treatment groups is impossible or highly difficult. However, the issues observational studies raise in terms of validity , confounding variables, and conclusiveness can mean that an experiment is more reliable.

If you’re able to randomise your participants safely and your research question is definitely causal in nature, consider using an experiment.

An observational study could be a good fit for your research if your research question is based on things you observe. If you have ethical, logistical, or practical concerns that make an experimental design challenging, consider an observational study. Remember that in an observational study, it is critical that there be no interference or manipulation of the research subjects. Since it’s not an experiment, there are no control or treatment groups either.

The key difference between observational studies and experiments is that, done correctly, an observational study will never influence the responses or behaviours of participants. Experimental designs will have a treatment condition applied to at least a portion of participants.

Exploratory research explores the main aspects of a new or barely researched question.

Explanatory research explains the causes and effects of an already widely researched question.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

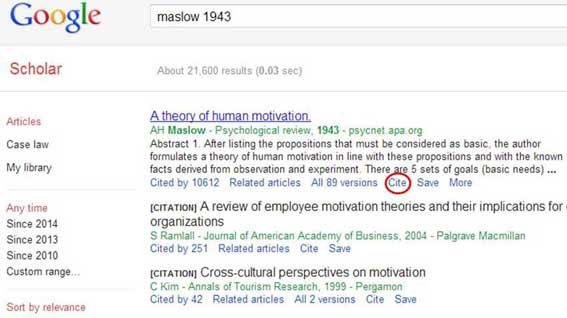

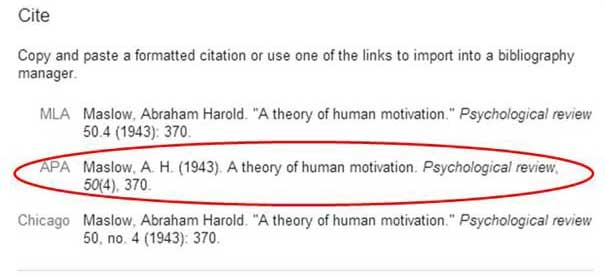

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2023, March 20). What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/observational-study/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The purpose of a field report in the social sciences is to describe the deliberate observation of people, places, and/or events and to analyze what has been observed in order to identify and categorize common themes in relation to the research problem underpinning the study. The content represents the researcher's interpretation of meaning found in data that has been gathered during one or more observational events.

Flick, Uwe. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection . London: SAGE Publications, 2018; Lofland, John, David Snow, Leon Anderson, and Lyn H. Lofland. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2022; Baker, Lynda. "Observation: A Complex Research Method." Library Trends 55 (Summer 2006): 171-189.; Kellehear, Allan. The Unobtrusive Researcher: A Guide to Methods . New York: Routledge, 2020.

How to Approach Writing a Field Report

How to Begin

Field reports are most often assigned in disciplines of the applied social sciences [e.g., social work, anthropology, gerontology, criminal justice, education, law, the health care services] where it is important to build a bridge of relevancy between the theoretical concepts learned in the classroom and the practice of actually doing the work you are being taught to do. Field reports are also common in certain science disciplines [e.g., geology] but these reports are organized differently and serve a different purpose than what is described below.

Professors will assign a field report with the intention of improving your understanding of key theoretical concepts by applying methods of careful and structured observation of, and reflection about, people, places, or phenomena existing in their natural settings. Field reports facilitate the development of data collection techniques and observation skills and they help you to understand how theory applies to real world situations. Field reports are also an opportunity to obtain evidence through methods of observing professional practice that contribute to or challenge existing theories.

We are all observers of people, their interactions, places, and events; however, your responsibility when writing a field report is to conduct research based on data generated by the act of designing a specific study, deliberate observation, synthesis of key findings, and interpretation of their meaning.

When writing a field report you need to:

- Systematically observe and accurately record the varying aspects of a situation . Always approach your field study with a detailed protocol about what you will observe, where you should conduct your observations, and the method by which you will collect and record your data.

- Continuously analyze your observations . Always look for the meaning underlying the actions you observe. Ask yourself: What's going on here? What does this observed activity mean? What else does this relate to? Note that this is an on-going process of reflection and analysis taking place for the duration of your field research.

- Keep the report’s aims in mind while you are observing . Recording what you observe should not be done randomly or haphazardly; you must be focused and pay attention to details. Enter the observation site [i.e., "field"] with a clear plan about what you are intending to observe and record in relation to the research problem while, at the same time, being prepared to adapt to changing circumstances as they may arise.

- Consciously observe, record, and analyze what you hear and see in the context of a theoretical framework . This is what separates data gatherings from reporting. The theoretical framework guiding your field research should determine what, when, and how you observe and act as the foundation from which you interpret your findings in relation to the underlying assumptions embedded in the theoretical framework .

Techniques to Record Your Observations Although there is no limit to the type of data gathering techniques you can use, these are the most frequently used methods:

Note Taking This is the most common and easiest method of recording your observations. Tips for taking notes include: organizing some shorthand symbols beforehand so that recording basic or repeated actions does not impede your ability to observe, using many small paragraphs, which reflect changes in activities, who is talking, etc., and, leaving space on the page so you can write down additional thoughts and ideas about what’s being observed, any theoretical insights, and notes to yourself that are set aside for further investigation. See drop-down tab for additional information about note-taking.

Photography With the advent of smart phones, an almost unlimited number of high quality photographs can be taken of the objects, events, and people observed during a field study. Photographs can help capture an important moment in time as well as document details about the space where your observation takes place. Taking a photograph can save you time in documenting the details of a space that would otherwise require extensive note taking. However, be aware that flash photography could undermine your ability to observe unobtrusively so assess the lighting in your observation space; if it's too dark, you may need to rely on taking notes. Also, you should reject the idea that photographs represent some sort of "window into the world" because this assumption creates the risk of over-interpreting what they show. As with any product of data gathering, you are the sole instrument of interpretation and meaning-making, not the object itself. Video and Audio Recordings Video or audio recording your observations has the positive effect of giving you an unfiltered record of the observation event. It also facilitates repeated analysis of your observations. This can be particularly helpful as you gather additional information or insights during your research. However, these techniques have the negative effect of increasing how intrusive you are as an observer and will often not be practical or even allowed under certain circumstances [e.g., interaction between a doctor and a patient] and in certain organizational settings [e.g., a courtroom]. Illustrations/Drawings This does not refer to an artistic endeavor but, rather, refers to the possible need, for example, to draw a map of the observation setting or illustrating objects in relation to people's behavior. This can also take the form of rough tables, charts, or graphs documenting the frequency and type of activities observed. These can be subsequently placed in a more readable format when you write your field report. To save time, draft a table [i.e., columns and rows] on a separate piece of paper before an observation if you know you will be entering data in that way.

NOTE: You may consider using a laptop or other electronic device to record your notes as you observe, but keep in mind the possibility that the clicking of keys while you type or noises from your device can be obtrusive, whereas writing your notes on paper is relatively quiet and unobtrusive. Always assess your presence in the setting where you're gathering the data so as to minimize your impact on the subject or phenomenon being studied.

ANOTHER NOTE: Techniques of deliberate observation and data gathering are not innate skills; they are skills that must be learned and practiced in order to achieve proficiency. Before your first observation, practice the technique you plan to use in a setting similar to your study site [e.g., take notes about how people choose to enter checkout lines at a grocery store if your research involves examining the choice patterns of unrelated people forced to queue in busy social settings]. When the act of data gathering counts, you'll be glad you practiced beforehand.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: An issue rarely discussed in the literature about conducting field research is whether you should move around the study site while observing or remaining situated in one place. Moving around can be intrusive, but it facilitates observing people's behavior from multiple vectors. However, if you remain in one place throughout the observation [or during each observation], you will eventually blend into the background and diminish the chance of unintentionally influencing people's behavior. If the site has a complex set of interactions or interdependent activities [e.g., a play ground], consider moving around; if the study site is relatively fixed [e.g., a classroom], then consider staying in one place while observing.

Examples of Things to Document While Observing

- Physical setting . The characteristics of an occupied space and the human use of the place where the observation(s) are being conducted.

- Objects and material culture . This refers to the presence, placement, and arrangement of objects that impact the behavior or actions of those being observed. If applicable, describe the cultural artifacts representing the beliefs [i.e., the values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions] of the individuals you are observing [e.g., the choice of particular types of clothing in the observation of family gatherings during culturally specific holidays].

- Use of language . Don't just observe but listen to what is being said, how is it being said, and the tone of conversations among participants.

- Behavior cycles . This refers to documenting when and who performs what behavior or task and how often they occur. Record at which stage this behavior is occurring within the setting.

- The order in which events unfold . Note sequential patterns of behavior or the moment when actions or events take place and their significance. Also, be prepared to note moments that diverge from these sequential patterns of behavior or actions.

- Physical characteristics of subjects. If relevant, document personal characteristics of individuals being observed. Note that, unless this data can be verified in interviews or from documentary evidence, you should only focus on characteristics that can be clearly observed [e.g., clothing, physical appearance, body language].

- Expressive body movements . This would include things like body posture or facial expressions. Note that it may be relevant to also assess whether expressive body movements support or contradict the language used in conversation [e.g., detecting sarcasm].

Brief notes about all of these examples contextualize your observations; however, your observation notes will be guided primarily by your theoretical framework, keeping in mind that your observations will feed into and potentially modify or alter these frameworks.

Sampling Techniques

Sampling refers to the process used to select a portion of the population for study . Qualitative research, of which observation is one method of data gathering, is generally based on non-probability and purposive sampling rather than probability or random approaches characteristic of quantitatively-driven studies. Sampling in observational research is flexible and often continues until no new themes emerge from the data, a point referred to as data saturation.

All sampling decisions are made for the explicit purpose of obtaining the richest possible source of information to answer the research questions. Decisions about sampling assumes you know what you want to observe, what behaviors are important to record, and what research problem you are addressing before you begin the study. These questions determine what sampling technique you should use, so be sure you have adequately answered them before selecting a sampling method.

Ways to sample when conducting an observation include:

- Ad Libitum Sampling -- this approach is not that different from what people do at the zoo; they observe whatever seems interesting at the moment. There is no organized system of recording the observations; you just note whatever seems relevant at the time. The advantage of this method is that you are often able to observe relatively rare or unusual behaviors that might be missed by more deliberately designed sampling methods. This method is also useful for obtaining preliminary observations that can be used to develop your final field study. Problems using this method include the possibility of inherent bias toward conspicuous behaviors or individuals, thereby missing mundane or repeated patterns of behavior, and that you may miss brief interactions in social settings.

- Behavior Sampling -- this involves watching the entire group of subjects and recording each occurrence of a specific behavior of interest and with reference to which individuals were involved. The method is useful in recording rare behaviors missed by other sampling methods and is often used in conjunction with focal or scan methods [see below]. However, sampling can be biased towards particular conspicuous behaviors.

- Continuous Recording -- provides a faithful record of behavior including frequencies, durations, and latencies [the time that elapses between a stimulus and the response to it]. This is a very demanding method because you are trying to record everything within the setting and, thus, measuring reliability may be sacrificed. In addition, durations and latencies are only reliable if subjects remain present throughout the collection of data. However, this method facilitates analyzing sequences of behaviors and ensures obtaining a wealth of data about the observation site and the people within it. The use of audio or video recording is most useful with this type of sampling.

- Focal Sampling -- this involves observing one individual for a specified amount of time and recording all instances of that individual's behavior. Usually you have a set of predetermined categories or types of behaviors that you are interested in observing [e.g., when a teacher walks around the classroom] and you keep track of the duration of those behaviors. This approach doesn't tend to bias one behavior over another and provides significant detail about a individual's behavior. However, with this method, you likely have to conduct a lot of focal samples before you have a good idea about how group members interact. It can also be difficult within certain settings to keep one individual in sight for the entire period of the observation without being intrusive.

- Instantaneous Sampling -- this is where observation sessions are divided into short intervals divided by sample points. At each sample point the observer records if predetermined behaviors of interest are taking place. This method is not effective for recording discrete events of short duration and, frequently, observers will want to record novel behaviors that occur slightly before or after the point of sampling, creating a sampling error. Though not exact, this method does give you an idea of durations and is relatively easy to do. It is also good for recording behavior patterns occurring at a specific instant, such as, movement or body positions.

- One-Zero Sampling -- this is very similar to instantaneous sampling, only the observer records if the behaviors of interest have occurred at any time during an interval instead of at the instant of the sampling point. The method is useful for capturing data on behavior patterns that start and stop repeatedly and rapidly, but that last only for a brief period of time. The disadvantage of this approach is that you get a dimensionless score for an entire recording session, so you only get one one data point for each recording session.

- Scan Sampling -- this method involves taking a census of the entire observed group at predetermined time periods and recording what each individual is doing at that moment. This is useful for obtaining group behavioral data and allows for data that are evenly representative across individuals and periods of time. On the other hand, this method may be biased towards more conspicuous behaviors and you may miss a lot of what is going on between observations, especially rare or unusual behaviors. It is also difficult to record more than a few individuals in a group setting without missing what each individual is doing at each predetermined moment in time [e.g., children sitting at a table during lunch at school]. The use of audio or video recording is useful with this type of sampling.

Alderks, Peter. Data Collection. Psychology 330 Course Documents. Animal Behavior Lab. University of Washington; Emerson, Robert M. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations . 2nd ed. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 2001; Emerson, Robert M. et al. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography . Paul Atkinson et al., eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), 352-368; Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Hazel, Spencer. "The Paradox from Within: Research Participants Doing-Being-Observed." Qualitative Research 16 (August 2016): 446-457; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports. Scribd Online Library; Presser, Jon and Dona Schwartz. “Photographs within the Sociological Research Process.” In Image-based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers . Jon Prosser, editor (London: Falmer Press, 1998), pp. 115-130; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing. UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports. Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

Structure and Writing Style

How you choose to format your field report is determined by the research problem, the theoretical framework that is driving your analysis, the observations that you make, and/or specific guidelines established by your professor. Since field reports do not have a standard format, it is worthwhile to determine from your professor what the preferred structure and organization should be before you begin to write. Note that field reports should be written in the past tense. With this in mind, most field reports in the social sciences include the following elements:

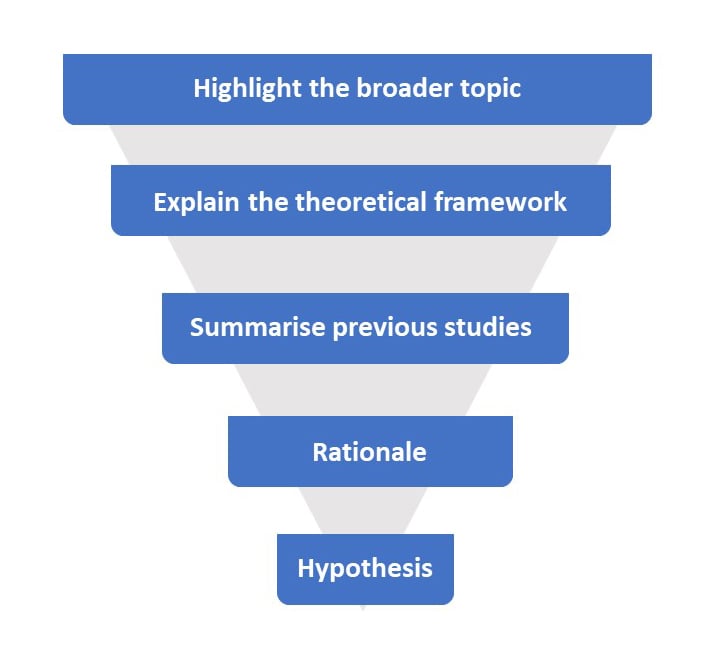

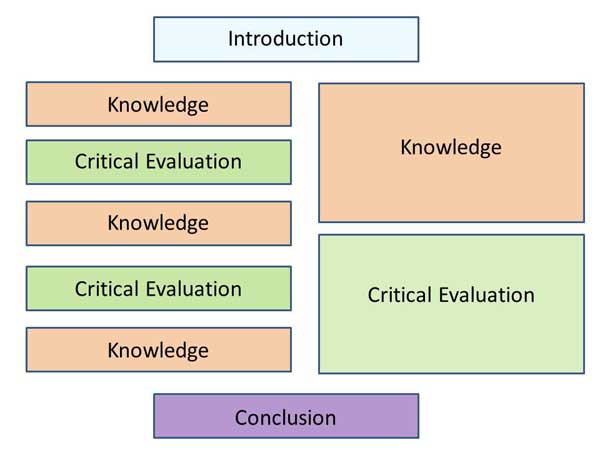

I. Introduction The introduction should describe the research problem, the specific objectives of your research, and the important theories or concepts underpinning your field study. The introduction should describe the nature of the organization or setting where you are conducting the observation, what type of observations you have conducted, what your focus was, when you observed, and the methods you used for collecting the data. Collectively, this descriptive information should support reasons why you chose the observation site and the people or events within it. You should also include a review of pertinent literature related to the research problem, particularly if similar methods were used in prior studies. Conclude your introduction with a statement about how the rest of the paper is organized.

II. Description of Activities

Your readers only knowledge and understanding of what happened will come from the description section of your report because they were not witnesses to the situation, people, or events that you are writing about. Given this, it is crucial that you provide sufficient details to place the analysis that will follow into proper context; don't make the mistake of providing a description without context. The description section of a field report is similar to a well written piece of journalism. Therefore, a useful approach to systematically describing the varying aspects of an observed situation is to answer the "Five W’s of Investigative Reporting." As Dubbels notes [p. 19], these are:

- What -- describe what you observed. Note the temporal, physical, and social boundaries you imposed to limit the observations you made. What were your general impressions of the situation you were observing. For example, as a student teacher, what is your impression of the application of iPads as a learning device in a history class; as a cultural anthropologist, what is your impression of women's participation in a Native American religious ritual?

- Where -- provide background information about the setting of your observation and, if necessary, note important material objects that are present that help contextualize the observation [e.g., arrangement of computers in relation to student engagement with the teacher].

- When -- record factual data about the day and the beginning and ending time of each observation. Note that it may also be necessary to include background information or key events which impact upon the situation you were observing [e.g., observing the ability of teachers to re-engage students after coming back from an unannounced fire drill].

- Who -- note background and demographic information about the individuals being observed e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, and/or any other variables relevant to your study]. Record who is doing what and saying what, as well as, who is not doing or saying what. If relevant, be sure to record who was missing from the observation.

- Why -- why were you doing this? Describe the reasons for selecting particular situations to observe. Note why something happened. Also note why you may have included or excluded certain information.

III. Interpretation and Analysis

Always place the analysis and interpretations of your field observations within the larger context of the theoretical assumptions and issues you described in the introduction. Part of your responsibility in analyzing the data is to determine which observations are worthy of comment and interpretation, and which observations are more general in nature. It is your theoretical framework that allows you to make these decisions. You need to demonstrate to the reader that you are conducting the field work through the eyes of an informed viewer and from the perspective of a casual observer.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when analyzing your observations:

- What is the meaning of what you have observed?

- Why do you think what you observed happened? What evidence do you have for your reasoning?

- What events or behaviors were typical or widespread? If appropriate, what was unusual or out of the ordinary? How were they distributed among categories of people?

- Do you see any connections or patterns in what you observed?

- Why did the people you observed proceed with an action in the way that they did? What are the implications of this?

- Did the stated or implicit objectives of what you were observing match what was achieved?

- What were the relative merits of the behaviors you observed?

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the observations you recorded?

- Do you see connections between what you observed and the findings of similar studies identified from your review of the literature?

- How do your observations fit into the larger context of professional practice? In what ways have your observations possibly changed or affirmed your perceptions of professional practice?

- Have you learned anything from what you observed?

NOTE: Only base your interpretations on what you have actually observed. Do not speculate or manipulate your observational data to fit into your study's theoretical framework.

IV. Conclusion and Recommendations

The conclusion should briefly recap of the entire study, reiterating the importance or significance of your observations. Avoid including any new information. You should also state any recommendations you may have based on the results of your study. Be sure to describe any unanticipated problems you encountered and note the limitations of your study. The conclusion should not be more than two or three paragraphs.

V. Appendix

This is where you would place information that is not essential to explaining your findings, but that supports your analysis [especially repetitive or lengthy information], that validates your conclusions, or that contextualizes a related point that helps the reader understand the overall report. Examples of information that could be included in an appendix are figures/tables/charts/graphs of results, statistics, pictures, maps, drawings, or, if applicable, transcripts of interviews. There is no limit to what can be included in the appendix or its format [e.g., a DVD recording of the observation site], provided that it is relevant to the study's purpose and reference is made to it in the report. If information is placed in more than one appendix ["appendices"], the order in which they are organized is dictated by the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

VI. References

List all sources that you consulted and obtained information from while writing your field report. Note that field reports generally do not include further readings or an extended bibliography. However, consult with your professor concerning what your list of sources should be included and be sure to write them in the preferred citation style of your discipline or is preferred by your professor [i.e., APA, Chicago, MLA, etc.].

Alderks, Peter. Data Collection. Psychology 330 Course Documents. Animal Behavior Lab. University of Washington; Dubbels, Brock R. Exploring the Cognitive, Social, Cultural, and Psychological Aspects of Gaming and Simulations . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2018; Emerson, Robert M. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations . 2nd ed. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 2001; Emerson, Robert M. et al. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography . Paul Atkinson et al., eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), 352-368; Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports. Scribd Online Library; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing. UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports. Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Study

- Next: About Informed Consent >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Aust Prescr

- v.41(3); 2018 Jun

Observational studies and their utility for practice

Julia fm gilmartin-thomas.

2 Research Department of Practice and Policy, University College London, School of Pharmacy, London

1 Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne

Ingrid Hopper

Randomised controlled clinical trials are the best source of evidence for assessing the efficacy of drugs. Observational studies provide critical descriptive data and information on long-term efficacy and safety that clinical trials cannot provide, at generally much less expense.

Observational studies include case reports and case series, ecological studies, cross-sectional studies, case-control studies and cohort studies. New and ongoing developments in data and analytical technology, such as data linkage and propensity score matching, offer a promising future for observational studies. However, no study design or statistical method can account for confounders and bias in the way that randomised controlled trials can.

Clinical registries are gaining importance as a method to monitor and improve the quality of care in Australia. Although registries are a form of cohort study, clinical trials can be incorporated into them to exploit the routine follow-up of patients to capture relevant outcomes.

Introduction

Observational studies involve the study of participants without any forced change to their circumstances, that is, without any intervention. 1 Although the participants’ behaviour may change under observation, the intent of observational studies is to investigate the ‘natural’ state of risk factors, diseases or outcomes. For drug therapy, a group of people taking the drug can be compared to people not taking the drug.

The main types of observational studies used in health research, their purpose and main strengths and limitations are shown in the Table . 2 - 8

| Study type | Purpose | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case reports and case series | Descriptive Usually first report of a notable issue , | Easy to undertake Can provide detailed information to assist hypothesis generation | Not generalisible |

| Ecological studies | Descriptive Data at group/population level | Relatively easy to undertake Routinely collected data can be used | No data on individuals |

| Cross-sectional studies | Descriptive Profiling of a population or outcome of interest at a single time point | Relatively easy to undertake | Need for representative data |

| Case-control studies | Analytical Identify risk factors for a defined outcome (disease or condition) , | Can be used to explore rare outcomes | Limited to a single outcome |

| Cohort studies | Descriptive and analytical Estimate the incidence of outcomes of interest as well as their determinants , , | Longitudinal Can be used to study multiple outcomes and multiple risk factors | Relatively difficult and expensive |

Their purpose may be descriptive, analytical or both.

- Descriptive studies are primarily designed to describe the characteristics of a studied population.

- Analytical studies seek to address cause-and-effect questions.

Case reports and case series

Case reports and case series are strictly speaking not studies. However, they serve a useful role in describing new or notable events in detail. These events often warrant further formal investigation. Examples include reports of unexpected benefits or adverse events, such as a case report describing the use of high-dose quetiapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia after intolerance to clozapine developed 9 and a case report of a medication error involving lookalike packaging. 10

Ecological studies

Ecological studies are based on analysis of aggregated data at group levels (for example populations), and do not involve data on individuals. These data can be analysed descriptively, but not definitively for causation. Typical examples include studies that examine patterns of drug use over time. One example is the comparison of the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 inhibitors in Australia and Canada. 11 Sometimes ecological studies describe associations between drugs and outcomes, such as changes in the rates of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage after the introduction of COX-2 inhibitors. 12 However, because individual-level data are not presented, causality is at best only implied in ecological studies. The 'ecological fallacy' refers to the error of assuming that associations observed in ecological studies are causal when they are not.

Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies collect data at a single point in time for each single individual, but the actual data collection may take place over a period of time or on more than one occasion. There is no longitudinal follow-up of individuals. Cross-sectional studies represent the archetypal descriptive study. 1 Typically, they provide a profile of a population of interest, which may be broad, like the Australian Health Survey undertaken intermittently by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 13 or focused on specific populations, such as older Australians. 14

Case-control studies

Case-control studies focus on determining risk factors for an outcome of interest (such as a disease or a drug’s adverse effect) that has already occurred. 5

- those who already have the outcome (cases)

- those who do not have the outcome (controls), who are often matched to the cases to make them similar and reduce bias.

Second, data on previous exposure to selected risk factors are collected and compared to see if these risk factors are more (or less) common among cases versus controls. Case-control studies are useful for studying the risk factors of rare outcomes, as there is no need to wait for these to occur. Multiple risk factors can be studied, but each case-control study can involve only one outcome. 5 One example explored the relationship between the use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs (risk factor) and the risk of hospitalisation for bleeding (outcome) in older people with a history of stroke. 15 Another case-control study explored the risk factors for the development of flucloxacillin-associated jaundice (outcome). 16

Cohort studies

Cohort studies compare outcomes between or among subgroups of participants defined on the basis of whether or not they are exposed to a particular risk or protective factor (defined as an exposure). They provide information on how these exposures are associated with changes in the risk of particular downstream outcomes. Compared to case-control studies, cohort studies take individuals with exposures and look for outcomes, rather than taking those with outcomes and looking for exposures. Cohort studies are longitudinal, that is they involve follow-up of a cohort of participants over time. This follow-up can be prospective or retrospective. Retrospective cohort studies are those for which follow-up has already occurred. They are typically used to estimate the incidence of outcomes of interest, including the adverse effects of drugs.

Cohort studies provide a higher level of evidence of causality than case-control studies because temporality (the explicit time relationship between exposures and outcomes) is preserved. They also have the advantage of not being limited to a single outcome of interest. Their main disadvantage, compared to case-control studies, has been that longitudinal data are more expensive and time-consuming to collect. However, with the availability of electronic data, it has become easier to collect longitudinal data.

One prospective cohort study explored the relationship between the continuous use of antipsychotic drugs (exposure) and mortality (outcome) and hospitalisation (outcome) in older people. 17 In another older cohort, a retrospective study was used to explore the relationship between long-term treatment adherence (exposure) and hospital readmission (outcome). 18

Observational studies versus randomised controlled trials

Compared to randomised controlled trials, observational studies are relatively quick, inexpensive and easy to undertake. Observational studies can be much larger than randomised controlled trials so they can explore a rare outcome. They can be undertaken when a randomised controlled trial would be unethical. However, observational studies cannot control for bias and confounding to the extent that clinical trials can. Randomisation in clinical trials remains the best way to control for confounding by ensuring that potential confounders (such as age, sex and comorbidities) are evenly matched between the groups being compared. In observational studies, adjustment for potential confounders can be undertaken, but only for a limited number of confounders, and only those that are known. Randomisation in clinical trials also minimises selection bias, while blinding (masking) controls for information bias. Hence, for questions regarding drug efficacy, randomised controlled trials provide the most robust evidence.

New and upcoming developments

New methods of analysis and advances in technology are changing the way observational studies are performed.

Clinical registries

Clinical registries are essentially cohort studies, and are gaining importance as a method to monitor and improve the quality of care. 19 These registries systematically collect a uniform longitudinal dataset to evaluate specific outcomes for a population that is identified by a specific disease, condition or exposure. This allows for the identification of variations in clinical practice 20 and benchmarking across practitioners or institutions. These data can then be used to develop initiatives to improve evidence-based care and patient outcomes. 21

An example of a clinical registry in Australia is the Australian Rheumatology Association Database, 22 which collects data on the biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs used for inflammatory arthritis. Clinical data from treating specialists are combined with patient-reported quality of life data and linked to national databases such as Medicare and the National Death Index. This registry has provided insight into the safety and efficacy of drugs and their effect on quality of life. It was used by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee to assess cost-effectiveness of these drugs. 23

Another example is the Haemostasis Registry. It was used to determine the thromboembolic adverse effects of off-label use of recombinant factor VII. 24

Clinical registries can also be used to undertake clinical trials which are nested within the registry architecture. Patients within a registry are randomised to interventions and comparators of interest. Their outcome data are then collected as part of the routine operation of the registry. The key advantages are convenience, reduced costs and greater representativeness of registry populations as opposed to those of traditional clinical trials.

One of the first registry-based trials was nested within the SWEDEHEART registry. 25 This prospectively examined manual aspiration of thrombus at the time of percutaneous coronary intervention in over 7000 patients. 26 The primary endpoint of all-cause mortality was ascertained through linkage to another Swedish registry. The cost of the trial was estimated to be US$400 000, which was a fraction of the many millions that a randomised controlled trial would have cost.

Propensity score matching

Even without randomising people within cohorts, methods have emerged in recent years that allow for less biased comparisons of two or more subgroups. Propensity score matching is a way to assemble two or more groups for comparison so that they appear like they had been randomised to an intervention or a comparator. 27 In short, the method involves logistic regression analyses to determine the likelihood (propensity) of each person within a cohort being on the intervention, and then matching people who were on the intervention to those who were not on the basis of propensity scores. Outcomes are then compared between the groups. Propensity score analysis of a large cohort of patients with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis found that natalizumab was superior to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in terms of improved outcomes. 28

Data technology

Increasing sophistication in techniques for data collection will lead to ongoing improvements in the capacity to undertake observational studies (and also clinical trials). Data linkage already offers a convenient way to capture outcomes, including retrospectively. However, ethical considerations must be taken into account, such as the possibility that informed consent might be required before linking data. Machine learning will soon allow for easy analyses of unstructured text (such as free text entries in an electronic prescription). 29 Patient-reported outcome measures are important and in future will be greatly facilitated by standardised, secure hardware and software platforms that allow for their capture, processing and analyses.

While clinical trials remain the best source of evidence regarding the efficacy of drugs, observational studies provide critical descriptive data. Observational studies can also provide information on long-term efficacy and safety that is usually lacking in clinical trials. New and ongoing developments in data and analytical technology offer a promising future for observational studies in pharmaceutical research.

Conflict of interest: Julia Gilmartin-Thomas is a Dementia research development fellow with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) - Australian Research Council (ARC). Ingrid Hopper is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Observational Research: What is, Types, Pros & Cons + Example

Researchers can gather customer data in a variety of ways, including surveys, interviews, and research. But not all data can be collected by asking questions because customers might not be conscious of their behaviors.

It is when observational research comes in. This research is a way to learn about people by observing them in their natural environment. This kind of research helps researchers figure out how people act in different situations and what things in the environment affect their actions.

This blog will teach you about observational research, including types and observation methods. Let’s get started.

What is observational research?

Observational research is a broad term for various non-experimental studies in which behavior is carefully watched and recorded.

The goal of this research is to describe a variable or a set of variables. More broadly, the goal is to capture specific individual, group, or setting characteristics.

Since it is non-experimental and uncontrolled, we cannot draw causal research conclusions from it. The observational data collected in research studies is frequently qualitative observation , but it can also be quantitative or both (mixed methods).

Types of observational research

Conducting observational research can take many different forms. There are various types of this research. These types are classified below according to how much a researcher interferes with or controls the environment.

Naturalistic observation

Taking notes on what is seen is the simplest form of observational research. A researcher makes no interference in naturalistic observation. It’s just watching how people act in their natural environments.

Importantly, there is no attempt to modify factors in naturalistic observation, as there would be when comparing data between a control group and an experimental group.

Case studiesCase studies

A case study is a sort of observational research that focuses on a single phenomenon. It is a naturalistic observation because it captures data in the field. But case studies focus on a specific point of reference, like a person or event, while other studies may have a wider scope and try to record everything that happens in the researcher’s eyes.

For example, a case study of a single businessman might try to find out how that person deals with a certain disease’s ups and down or loss.

Participant observation

Participant observation is similar to naturalistic observation, except that the researcher is a part of the natural environment they are studying. In such research, the researcher is also interested in rituals or cultural practices that can only be evaluated by sharing experiences.

For example, anyone can learn the basic rules of table Tennis by going to a game or following a team. Participant observation, on the other hand, lets people take part directly to learn more about how the team works and how the players relate to each other.

It usually includes the researcher joining a group to watch behavior they couldn’t see from afar. Participant observation can gather much information, from the interactions with the people being observed to the researchers’ thoughts.

Controlled observation

A more systematic structured observation entails recording the behaviors of research participants in a remote place. Case-control studies are more like experiments than other types of research, but they still use observational research methods. When researchers want to find out what caused a certain event, they might use a case-control study.

Longitudinal observation

This observational research is one of the most difficult and time-consuming because it requires watching people or events for a long time. Researchers should consider longitudinal observations when their research involves variables that can only be seen over time.

After all, you can’t get a complete picture of things like learning to read or losing weight in a single observation. Longitudinal studies keep an eye on the same people or events over a long period of time and look for changes or patterns in behavior.

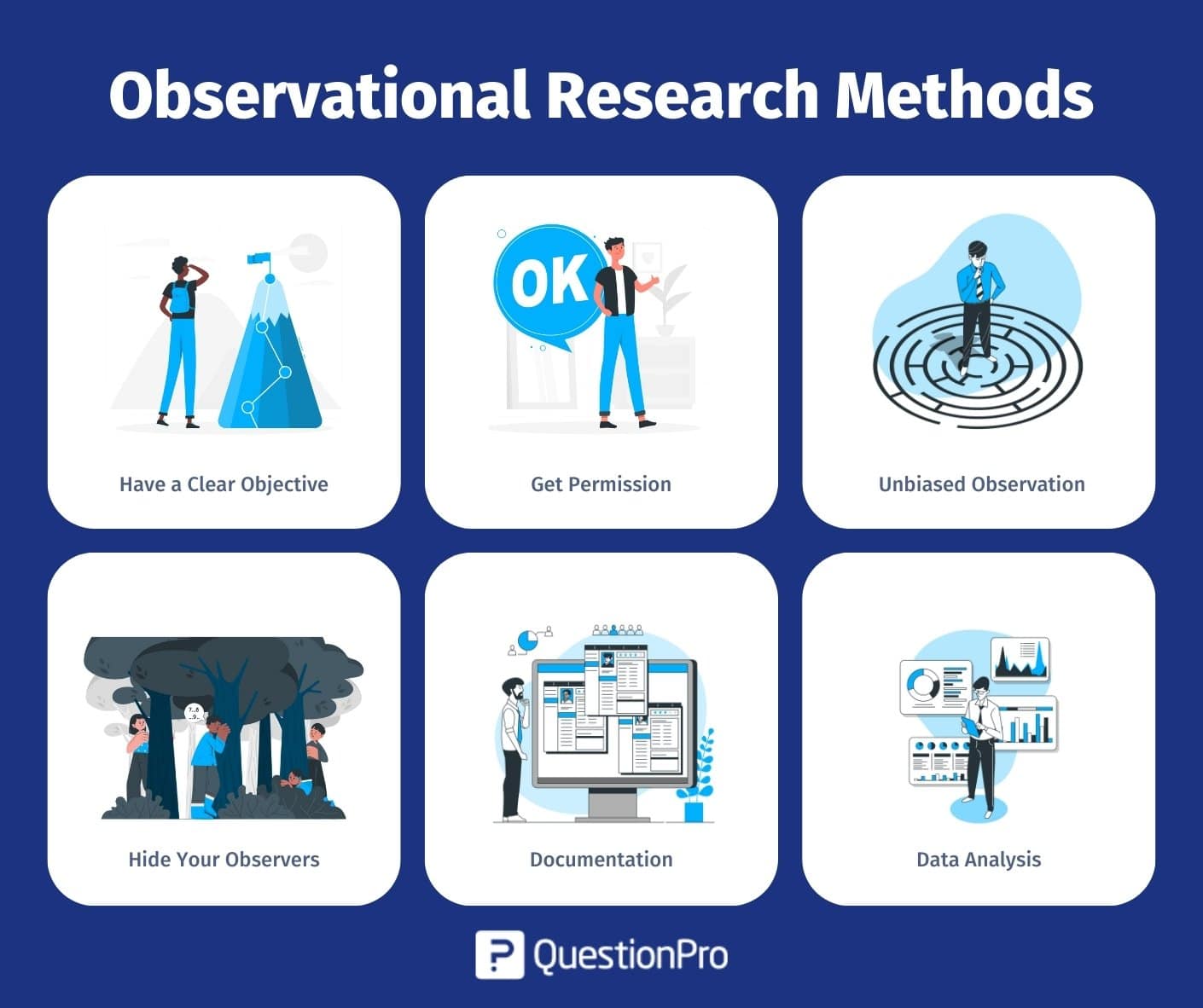

Observational research methods

When doing this research, there are a few observational methods to remember to ensure that the research is done correctly. Along with other research methods, let’s learn some key research methods of it:

Have a clear objective

For an observational study to be helpful, it needs to have a clear goal. It will help guide the observations and ensure they focus on the right things.

Get permission

Get permission from your participants. Getting explicit permission from the people you will be watching is essential. It means letting them know that they will be watched, the observation’s goal, and how their data will be used.

Unbiased observation

It is important to make sure the observations are fair and unbiased. It can be done by keeping detailed notes of what is seen and not putting any personal meaning on the data.

Hide your observers

In the observation method, keep your observers hidden. The participants should be unaware of the observers to avoid potential bias in their actions.

Documentation

It is important to document the observations clearly and straightforwardly. It will allow others to examine the information and confirm the observational research findings.

Data analysis

Data analysis is the last method. The researcher will analyze the collected data to draw conclusions or confirm a hypothesis.

Pros and cons of observational research

Observational studies are a great way to learn more about how your customers use different parts of your business. There are so many pros and cons of observational research. Let’s have a look at them.

- It provides a practical application for a hypothesis. In other words, it can help make research more complete.

- You can see people acting alone or in groups, such as customers. So, you can answer a number of questions about how people act as customers.

- There is a chance of researcher bias in observational research. Experts say that this can be a very big problem.

- Some human activities and behaviors can be difficult to understand. We are unable to see memories or attitudes. In other words, there are numerous situations in which observation alone is inadequate.

Example of observational research

The researcher observes customers buying products in a mall. Assuming the product is soap, the researcher will observe how long the customer takes to decide whether he likes the packaging or comes to the mall with his decision already made based on advertisements.

If the customer takes their time making a decision, the researcher will conclude that packaging and information on the package affect purchase behavior. If a customer makes a quick decision, the decision is likely predetermined.

As a result, the researcher will recommend more and better advertisements in this case. All of these findings were obtained through simple observational research.

How to conduct observational research with QuestionPro?

QuestionPro can help with observational research by providing tools to collect and analyze data. It can help in the following ways:

Define the research goals and question types you want to answer with your observational study . Use QuestionPro’s customizable survey templates and questions to do a survey that fits your research goals and gets the necessary information.

You can distribute the survey to your target audience using QuestionPro’s online platform or by sending a link to the survey.

With QuestionPro’s real-time data analysis and reporting features, you can collect and look at the data as people fill out the survey. Use the advanced analytics tools in QuestionPro to see and understand the data and find insights and trends.

If you need to, you can export the data from QuestionPro into the analysis tools you like to use. Draw conclusions from the collected and analyzed data and answer the research questions that were asked at the beginning of the research.

For a deeper understanding of human behaviors and decision-making processes, explore the realm of Behavioral Research .

To summarize, observational research is an effective strategy for collecting data and getting insights into real-world phenomena. When done right, this research can give helpful information and help people make decisions.

QuestionPro is a valuable tool that can help with observational research by letting you create online surveys, analyze data in real time, make surveys your own, keep your data safe, and use advanced analytics tools.

To do this research with QuestionPro, researchers need to define their research goals, do a survey that matches their goals, send the survey to participants, collect and analyze the data, visualize and explain the results, export data if needed, and draw conclusions from the data collected.

By keeping in mind what has been said above, researchers can use QuestionPro to help with their observational research and gain valuable data. Try out QuestionPro today!

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Observational research is a method in which researchers observe and systematically record behaviors, events, or phenomena without directly manipulating them.

There are three main types of observational research: naturalistic observation, participant observation, and structured observation.

Naturalistic observation involves observing subjects in their natural environment without any interference.

MORE LIKE THIS

QuestionPro Thrive: A Space to Visualize & Share the Future of Technology

Jun 18, 2024

Relationship NPS Fails to Understand Customer Experiences — Tuesday CX

CX Platform: Top 13 CX Platforms to Drive Customer Success

Jun 17, 2024

How to Know Whether Your Employee Initiatives are Working

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

What is an Observational Study: Definition & Examples

By Jim Frost 10 Comments

What is an Observational Study?

An observational study uses sample data to find correlations in situations where the researchers do not control the treatment, or independent variable, that relates to the primary research question. The definition of an observational study hinges on the notion that the researchers only observe subjects and do not assign them to the control and treatment groups. That’s the key difference between an observational study vs experiment. These studies are also known as quasi-experiments and correlational studies .

True experiments assign subject to the experimental groups where the researchers can manipulate the conditions. Unfortunately, random assignment is not always possible. For these cases, you can conduct an observational study.

In this post, learn about the types of observational studies, why they are susceptible to confounding variables, and how they compare to experiments. I’ll close this post by reviewing a published observational study about vitamin supplement usage.

Observational Study Definition

In an observational study, the researchers only observe the subjects and do not interfere or try to influence the outcomes. In other words, the researchers do not control the treatments or assign subjects to experimental groups. Instead, they observe and measure variables of interest and look for relationships between them. Usually, researchers conduct observational studies when it is difficult, impossible, or unethical to assign study participants to the experimental groups randomly. If you can’t randomly assign subjects to the treatment and control groups, then you observe the subjects in their self-selected states.

Observational Study vs Experiment

Randomized experiments provide better results than observational studies. Consequently, you should always use a randomized experiment whenever possible. However, if randomization is not possible, science should not come to a halt. After all, we still want to learn things, discover relationships, and make discoveries. For these cases, observational studies are a good alternative to a true experiment. Let’s compare the differences between an observational study vs. an experiment.

Random assignment in an experiment reduces systematic differences between experimental groups at the beginning of the study, which increases your confidence that the treatments caused any differences between groups you observe at the end of the study. In contrast, an observational study uses self-formed groups that can have pre-existing differences, which introduces the problem of confounding variables. More on that later!

In a randomized experiment, randomization tends to equalize confounders between groups and, thereby, prevents problems. In my post about random assignment , I describe that process as an elegant solution for confounding variables. You don’t need to measure or even know which variables are confounders, and randomization will still mitigate their effects. Additionally, you can use control variables in an experiment to keep the conditions as consistent as possible. For more detail about the differences, read Observational Study vs. Experiment .

|

| |

| Does not assign subjects to groups | Randomly assigns subjects to control and treatment groups |

| Does not control variables that can affect outcome | Administers treatments and controls influence of other variables |

| Correlational findings. Differences might be due to confounders rather than the treatment | More confident that treatments cause the differences in outcomes |

If you’re looking for a middle ground choice between observational studies vs experiments, consider using a quasi-experimental design. These methods don’t require you to randomly assign participants to the experimental groups and still allow you to draw better causal conclusions about an intervention than an observational study. Learn more about Quasi-Experimental Design Overview & Examples .

Related posts : Experimental Design: Definition and Examples , Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) , and Control Groups in Experiments

Observational Study Examples

Consider using an observational study when random assignment for an experiment is problematic. This approach allows us to proceed and draw conclusions about effects even though we can’t control the independent variables. The following observational study examples will help you understand when and why to use them.

For example, if you’re studying how depression affects performance of an activity, it’s impossible to assign subjects to the depression and control group randomly. However, you can have subjects with and without depression perform the activity and compare the results in an observational study.

Or imagine trying to assign subjects to cigarette smoking and non-smoking groups randomly?! However, you can observe people in both groups and assess the differences in health outcomes in an observational study.

Suppose you’re studying a treatment for a disease. Ideally, you recruit a group of patients who all have the disease, and then randomly assign them to the treatment and control group. However, it’s unethical to withhold the treatment, which rules out a control group. Instead, you can compare patients who voluntarily do not use the medicine to those who do use it.

In all these observational study examples, the researchers do not assign subjects to the experimental groups. Instead, they observe people who are already in these groups and compare the outcomes. Hence, the scientists must use an observational study vs. an experiment.

Types of Observational Studies

The observational study definition states that researchers only observe the outcomes and do not manipulate or control factors . Despite this limitation, there various types of observational studies.

The following experimental designs are three standard types of observational studies.

- Cohort Study : A longitudinal observational study that follows a group who share a defining characteristic. These studies frequently determine whether exposure to risk factor affects an outcome over time.

- Case-Control Study : A retrospective observational study that compares two existing groups—the case group with the condition and the control group without it. Researchers compare the groups looking for potential risk factors for the condition.

- Cross-Sectional Study : Takes a snapshot of a moment in time so researchers can understand the prevalence of outcomes and correlations between variables at that instant.

Qualitative research studies are usually observational in nature, but they collect non-numeric data and do not perform statistical analyses.

Retrospective studies must be observational.

Later in this post, we’ll closely examine a quantitative observational study example that assesses vitamin supplement consumption and how that affects the risk of death. It’s possible to use random assignment to place each subject in either the vitamin treatment group or the control group. However, the study assesses vitamin consumption in 40,000 participants over the course of two decades. It’s unrealistic to enforce the treatment and control protocols over such a long time for so many people!

Drawbacks of Observational Studies

While observational studies get around the inability to assign subjects randomly, this approach opens the door to the problem of confounding variables. A confounding variable, or confounder, correlates with both the experimental groups and the outcome variable. Because there is no random process that equalizes the experimental groups in an observational study, confounding variables can systematically differ between groups when the study begins. Consequently, confounders can be the actual cause for differences in outcome at the end of the study rather than the primary variable of interest. If an experiment does not account for confounding variables, confounders can bias the results and create spurious correlations .

Performing an observational study can decrease the internal validity of your study but increase the external validity. Learn more about internal and external validity .

Let’s see how this works. Imagine an observational study that compares people who take vitamin supplements to those who do not. People who use vitamin supplements voluntarily will tend to have other healthy habits that exist at the beginning of the study. These healthy habits are confounding variables. If there are differences in health outcomes at the end of the study, it’s possible that these healthy habits actually caused them rather than the vitamin consumption itself. In short, confounders confuse the results because they provide alternative explanations for the differences.

Despite the limitations, an observational study can be a valid approach. However, you must ensure that your research accounts for confounding variables. Fortunately, there are several methods for doing just that!

Learn more about Correlation vs. Causation: Understanding the Differences .

Accounting for Confounding Variables in an Observational Study

Because observational studies don’t use random assignment, confounders can be distributed disproportionately between conditions. Consequently, experimenters need to know which variables are confounders, measure them, and then use a method to account for them. It involves more work, and the additional measurements can increase the costs. And there’s always a chance that researchers will fail to identify a confounder, not account for it, and produce biased results. However, if randomization isn’t an option, then you probably need to consider an observational study.

Trait matching and statistically controlling confounders using multivariate procedures are two standard approaches for incorporating confounding variables.

Related post : Causation versus Correlation in Statistics

Matching in Observational Studies

Matching is a technique that involves selecting study participants with similar characteristics outside the variable of interest or treatment. Rather than using random assignment to equalize the experimental groups, the experimenters do it by matching observable characteristics. For every participant in the treatment group, the researchers find a participant with comparable traits to include in the control group. Matching subjects facilitates valid comparisons between those groups. The researchers use subject-area knowledge to identify characteristics that are critical to match.

For example, a vitamin supplement study using matching will select subjects who have similar health-related habits and attributes. The goal is that vitamin consumption will be the primary difference between the groups, which helps you attribute differences in health outcomes to vitamin consumption. However, the researchers are still observing participants who decide whether they consume supplements.

Matching has some drawbacks. The experimenters might not be aware of all the relevant characteristics they need to match. In other words, the groups might be different in an essential aspect that the researchers don’t recognize. For example, in the hypothetical vitamin study, there might be a healthy habit or attribute that affects the outcome that the researchers don’t measure and match. These unmatched characteristics might cause the observed differences in outcomes rather than vitamin consumption.

Learn more about Matched Pairs Design: Uses & Examples .

Using Multiple Regression in Observational Studies

Random assignment and matching use different methods to equalize the experimental groups in an observational study. However, statistical techniques, such as multiple regression analysis , don’t try to equalize the groups but instead use a model that accounts for confounding variables. These studies statistically control for confounding variables.