Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 31 December 2022

The severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bullying victimization, mental health indicators and quality of life

- June T. Forsberg 1 &

- Steinar Thorvaldsen 2

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 22634 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4379 Accesses

7 Citations

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Children and adolescents have been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of this study was to explore the prevalence of traditional and digital bullying and mental health problems a year into the pandemic. Further, how anxiety level, loneliness, and self-perceived school functioning have influenced the quality of life. A comprehensive questionnaire was administered (N = 1239) in the city of Tromsø and compared to a similar data collection (N = 972) conducted in the same schools in 2017. The main findings were increased prevalence in bullying, more mental health problems and significantly reduced quality of life compared to before the pandemic. Implications and the importance of implementing anti-bullying and psychosocial measures after the pandemic are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

The association between psychosocial factors, protective factors, and its associated triggers with psychological distress among Bolivian adolescents

Passakorn Suanrueang, Karl Peltzer, … Lyen Krenz Yap

The impact of resilience as a protective factor on Health-Related Quality of Life’s psychological dimensions among adolescents who experience peer victimization

Ángela de Lourdes Martín-Pérez, Inés Morán-Sánchez & Juan José Gascón-Cánovas

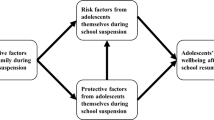

Understanding protective and risk factors affecting adolescents’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic

Min Lan, Qianqian Pan, … Nancy Wai Ying Law

Introduction

On March 12, 2020, the day after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the spread of SARS-CoV-2 as a pandemic, Norway and several other countries around the world locked down large parts of society in attempt to limit the spread of the virus. The lockdown has been referred to as the most drastic action carried out in Norway since World War II 1 . The measures that were taken included isolation and quarantine regulations, comprehensive social distancing, and total lockdown of schools, public offices and services, and leisure activities for a period of 2 months. The lockdown led to concerns about the impact on children and adolescents’ well-being, quality of life (QoL), and possible mental health consequences, and researchers all over the world engaged in comprehensive work to document possible negative impacts 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 . The concerns were found to be legitimate. In Europe, children and adolescents reported reduced QoL, higher anxiety levels, more depression symptoms, loneliness, and behavioral problems in several studies, already after the first 3 months of the pandemic 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 .

Ravens-Sieberer et al. 6 also found that two-thirds of their participants reported to be highly burdened by the pandemic. A specific burden was the reduced ability to socialize with friends and peers. For children and adolescents are socialization and positive relations with peers of high importance for general well-being 9 , QoL 10 , development of social skills 11 , and the ability to form positive relations when they grow up 12 . In addition, these relations are protective factors against the negative impact of stress 13 and mental health problems 14 , 15 . On the other hand, problems with peers predict an increased risk of developing mental health issues and behavioral problems both during childhood, adolescence, and later in life 12 .

The reduced ability to socialize increased the prevalence of loneliness within all age ranges, and the pandemic has also been referred to as “the loneliness pandemic” in the literature 16 . Loneliness is associated with reduced QoL 17 and is found to predict mental health problems and psychiatric impact, such as depression symptoms, social anxiety, paranoia, and suicide attempts. During the lockdown, the adolescents who felt lonely also reported that they experienced more mental health problems 8 , 18 , 19 . Without support from family, friends, and clinical measures (if necessary), have mental health symptoms the tendency to increase with age and into adulthood. The importance of follow-up and support for vulnerable young people after the pandemic is therefore highlighted in the literature 8 .

When the second virus wave hit Norway during the fall of 2020, was the city of Tromsø obliged to reinforce lockdown in some parts of society 1 . In attempt to spare children and adolescents for the negative psychosocial consequences of lockdown, the schools were kept open. However, strict infection control measures were employed, which had severe influence on the daily routines at the schools. The measures were implemented as a traffic light model, with three levels of measures (red, yellow, and green). Avoidance of all physical contact was practiced at all three levels. In levels yellow and red, the pupils were divided into cohorts (different cohort sizes depending on the level of measure) and practiced both social and physical movement restrictions. When a pupil tested positive for COVID-19, the rest of the cohort was placed in quarantine, and homeschooling was initiated for 10 days. The traffic light model was maintained throughout the second and third virus waves, until the end of May 2021 20 , and the level of measure implemented was under continuous consideration depending on the extent of virus spread at each school 21 . In Tromsø, level yellow was maintained for most of the time during this period. Although the traffic light model was important to limit the spread of the virus in the schools, it has also been a disturbing and negative factor for the academic, psychosocial, and institutional environment at school. The quality of the overall school climate is an important predictor for children’s and adolescents’ ability to function at school 22 .

Bullying during the pandemic

Bullying victimization refers to repeated acts where a person is exposed to intentional negative actions, such as verbal, physical, and/or relational aggression, or harassment, by a peer or a group of peers in real life or online 23 , 24 . A well-established time frame in the literature for conceptualizing these repeated negative acts as bullying, is if a person report that it happens “two or three times per month or more often” 24 , 25 , 26 . A recent national report shows that 6% of adolescents in Norway report that they are being bullied at school, and 3% report digital bullying 27 . Being bullied by peers has a major negative impact on psychosocial well-being and school functioning, and it is considered one of the most stressful life events that young people can be exposed to 12 , 28 , 29 , 30 . Bullying is often divided into four categories: (I) direct physical bullying (e.g., physical attacks), (II) direct verbal bullying (threats, insults, or name calling), (III) indirect verbal/social bullying (social exclusion or spreading of rumors), and (IV) cyberbullying/digital bullying or harassment (threatening messages, posting of pictures from vulnerable situations, exclusion from social media). The first three categories can be considered traditional bullying, whereas digital bullying is a phenomenon that emerged as a result of the technological era and is relatively new in the research field. Therefore, the negative impact of digital bullying compared to traditional bullying has been a focus in several studies in recent decades 23 , 25 , 26 . The literature reports that being harassed on digital platforms or being a victim of cyberbullying is associated with the same mental health problems and psychosocial consequences as traditional bullying 31 . During the pandemic, technological tools and digital social platforms were highlighted as measures to reduce loneliness 32 , but, unfortunately, there has also been documented an increased prevalence of digital bullying 33 , 34 .

In the work of documenting the prevalence of bullying during the pandemic, the literature is inconclusive. Vaillancourt et al. 35 explored both bullying at school and digital bullying before and 6–8 months into the pandemic. They found that the participants reported more bullying of all forms before the pandemic, except for digital bullying, where the differences were less pronounced. The conclusion of the study was that the pandemic in general seems to have had a positive effect on bullying rates. Armitage 36 , on the other hand, raises a major concern that bullying may have substantially increased during the pandemic, due to less focus on anti-bullying measures and more opportunities for digital bullying. Further, he states that there is an urgent need to determine the impact of the pandemic on the prevalence of all forms of bullying and for implementation of measures and interventions to reduce the negative impact on children and adolescents’ health.

Objectives of the present study

The aims of this study were to investigate the impact of COVID-19, a year into the pandemic, on bullying; emotional, behavioral, and peer problems; and QoL among children living in Northern Norway. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored these factors at this stage in the pandemic. The research tasks were as follows:

Explore the prevalence of traditional and digital bullying during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic.

Explore whether emotional, behavioral, and peer problems increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic.

Explore how anxiety level, loneliness, and self-perceived school functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the subjective feeling of life quality.

All research tasks also explored gender differences and differences between age groups. Based on Barlett et al. 33 , Shin & Choi 34 and Vaillancourt et al. 35 we hypothesized reduced traditional bullying and increased digital bullying during the pandemic compared to before. Further, we expected to find increased scores in emotional problems, behavioral problems, and peer problems 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 . We also expected to find reduced QoL due to anxiety 4 , loneliness 17 , and self-perceived school functioning 22 during the pandemic.

The analysis presented in this article is part of the project Well-being in Tromsø (WiT) (org. title: Trivsel i Tromsø) of UiT the Arctic University of Norway. WiT collected data on bullying, harassment, mental health, and QoL once a year during the period of 2012–2018 and WiT-2 in 2021, in the same school and the same grades. Although the WiT project is longitudinal, no longitudinal analyses of the same children was carried out in the present study.

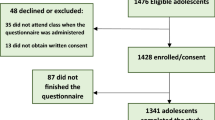

The data that describe the pandemic group were collected in April 2021, a year into the pandemic (N = 1239: 573 females and 666 males). The data that describe the pre-pandemic group were collected in the spring of 2017 (N = 972: 452 females and 520 males). Data from 2017 were chosen instead of data from 2018 due to better quality and higher response rate (65% and 48%, respectively).

Participants, design, and procedure

A total of 2,211 school children (1,025 females and 1,186 males) between grades 4 and 10 (ages 9–15) were included in the analysis for the present study. The participants were split into three different age groups: grades 4 + 5 (middle school grades/age 9–10 years old) (N = 741: 355 females and 386 males); grades 6 + 7 (upper school grades/age 11–12 years old) (N = 757: 348 females and 409 males); and grades 8–10 (junior high grades/age 13–15 years old) (N = 713: 322 females and 391 males). The response rates were 85% for the pandemic group and 65% for the pre-pandemic group. There were no significant differences between genders ( p = 0.25) or age groups ( p = 0.87) in the pandemic and pre- pandemic groups.

A cross-sectional comparative design with two groups (pandemic group and pre-pandemic group) was employed for all analysis in this study. The procedure was similar for both groups, but with some points of distinction. The study was presented and proposed to the school leaders in the WiT project, which agreed that the study could be conducted in their schools (N = 6). Thereafter were the teaching staff at each school invited to meetings of 30 min (physical meetings in 2017 and digital meetings in 2021) were the purpose of the study and procedure were presented, and the teachers could ask questions they might have. Further, study information was forwarded to the parents via a digital information channel (Transponder). In the pre-pandemic group, was personal information collected; therefore, required approval by the Regional Ethical Committee for Medical Research, REK-Nord, and written consent by the parents. In the pandemic group were no personal data collected, and participation was anonymous; therefore, no ethical was required.

The data collection was carried out digitally in the classrooms using Questback (pre-pandemic group) and Nettskjema (pandemic group). Both Questback and Nettskjema is commercial tools developed for use in a wide range of investigations and has good reputation for data security. However, due to changes in UiT license agreements, Questback was replaced with Nettskjema between the data collections. Before the pupils filled out the questionnaires they were informed of the purpose of the study and some basic research ethical principles, i.e., that participation is voluntarily, and that all data are kept safe and only accessible for the researchers. In the pre-pandemic group this information was provided by the teachers. In the pandemic group did the researchers prepare a short video where the purpose and ethics were presented. Since participation was anonymous in this group, this was also emphasized in the video. The data collections were carried out over a period of 2 months during the spring of 2017 and 2021.

WiT uses several measures to gain information on school children’s self-perceived understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on bullying (both traditional and digital); emotional, behavioral, and peer problems; and the subjective feeling of life quality. A comprehensive questionnaire was carried out that included several sets of measures. Bullying, the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), and KINDL® (description below) were employed as measures for all participants included in this study. The COVID categories were employed in the pandemic group only. All items and categories in the questionnaire are presented in Online Appendix 1 .

Bullying was measured with 15 items for traditional bullying 25 , 26 and explored verbal (five items), social (six items), and physical bullying (four items). Further, digital bullying was measured with eight items from Menesini et al. 23 . The items employed a five-point Likert scale (1 = “never”, 2 = “only once or twice”, 3 = “two or three times a month”, 4 = “about once per week”, and 5 = “several times a week). The time frame was set for the past 3 months. The cut-off point for being bullied was set to “two or three times a month” or more often 24 , 25 , 26 . Cronbach’s alpha for the different scales is consistent, with high reliability (verbal α = 0.84, social α = 0.85, physical α = 0.86, and digital α = 0.87). Prevalence of bullying was measured with two items (I am being bullied during the school day and I am being bullied outside of school), and max scores were calculated for traditional bullying, digital bullying, and both.

Strength and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ)

The SDQ 37 , 38 is comprised of five scales of five items each that assess emotional problems (α = 0.66), conduct problems (α = 0.60), hyperactivity (α = 0.67), peer problems (α = 0.41), and prosocial skills (α = 0.66). The reliability is below the cut-off of 0.7 for obtaining acceptable reliability for all five scales, but the SDQ has been a widely used tool since it was developed 39 , 40 . The items are scored on a three-point Likert scale (“not true”, “somewhat true”, “certainly true”). The time frame was set for the past 3 months. “Somewhat true” is always scored as 1, but the scoring of “not true” and “certainly true” varies depending on whether the item is positively or negatively worded. For each of the five scales, the score can range from 0 to 10, if all items are completed. The total difficulties scale (α = 0.80) is generated by summing scores from all the scales, except the prosocial scale. The result score for the total difficulties scale can range from 0 to 40 and is counted as missing if one of the component scales is missing. The prosocial scale was not included in any analysis for the present study.

KINDL® 41 , 42 measures experienced QoL and consist of a 24-item scale (α = 0.84) that measures six different dimensions (subscales) of QoL: experienced physical health (α = 0.63), emotional well-being (α = 0.68), self-esteem (α = 0.75), relationship to family (α = 0.76), relationship to friends (α = 0.74), and relationship to school (α = 0.64). Every question asks about the previous week’s experiences and is scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “never”, 2 = “rarely”, 3 = “sometimes”, 4 = “often”, and 5 = “always”). Ten of the QoL items have reverse-order scaling, meaning that a higher item score implies poorer QoL, and these item scores were reversed. Mean item scores are calculated for all the subscales. Correlations with comparable QoL scales have shown acceptable reliability as well as satisfactory discriminant validity 43 .

COVID categories

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was measured with three categories that were developed for this study: anxiety (three items: Have you been worrying about the virus? | Do you think about the virus even when you don’t mean to? | Have you been afraid to be infected when you are at school? | α = 0.76), loneliness (two items: Have you been with your friends as much as you have wanted to? | Have you been lonely? | α = 0.73), and school functioning (three items: Have you been able to concentrate on your schoolwork? | Did you manage to concentrate when there was homeschooling? | Have you been able to do your best with your schoolwork? | α = 0.73). The items were scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “never”, 2 = “rarely”, 3 = “sometimes”, 4 = “often”, and 5 = “always”). Four items have reverse-order scaling, meaning that a higher item score implies poorer circumstances.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 28.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL. USA). Reliability for all measurement scales was explored with Cronbach`s alpha. For the first research task, the prevalence of traditional and digital bullying was explored with frequency statistics. Differences in prevalence between the pandemic group and the pre-pandemic group and differences between genders were tested with a chi-square test. Differences in prevalence between age groups was explored with analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant effects were followed up with contrast analysis, and the least significant difference (LSD) adjustment was chosen for the multiple comparisons. Effect sizes were estimated by Cohen’s d-value, with Cohen’s conventions: 0.2 = small effect, 0.5 = medium effect, and 0.8 = large effect 44 . Cohen’s d expresses the standardized difference between two means.

For the second research task, emotional problems, behavioral problems, and peer problems between the pandemic group and the pre-pandemic group were explored with descriptive statistics and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Gender and age groups were included as covariates in the analysis. Significant effects were followed up with LSD adjustments. Wilks’s lambda was conducted to determine if there were differences between the groups in these combinations of dependent variables.

For the third research task, the COVID categories (anxiety, loneliness, and self-perceived school functioning) were explored as dependent variables in three separate linear multiple regression analyses. The KINDL subscales and total sum scale were included as independent variables. However, self-esteem (β = 0) was excluded as a variable in all three regression models. Correlations between all the dependent and independent variables were also explored. Pearson’s r-coefficient was used to express the strength of correlation between two variables. Typically, values of ± 0.1 represent a small effect, ± 0.3 a medium effect, and ± 0.5 a large effect 44 . A significant p -value of 0.05 was set for all analyses in this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written information about the project was provided to the students and parents, and the parents gave consent for their children to participate. Both the students and parents were able to withdraw consent at any time and require that collected data would be deleted. The authors were the only ones with access to the data during the data collections. Data collection 2021: No personal data were collected; therefore, no ethical approval was required. Data collection 2017: Personal information was collected; The project was approved by Regional Ethical Committee for Medical Research, REK-Nord. However, no personal data from the data collection in 2017 was included in this study.

A contract was made between UiT the Arctic University of Norway and the school leaders at each contributing school. The contract described area of responsibility and assignments for the school leaders, teachers, and researchers during the project period.

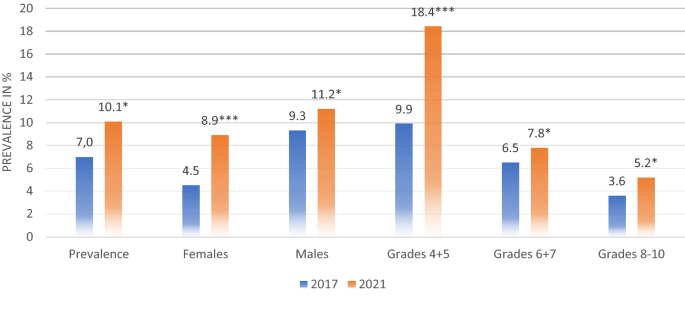

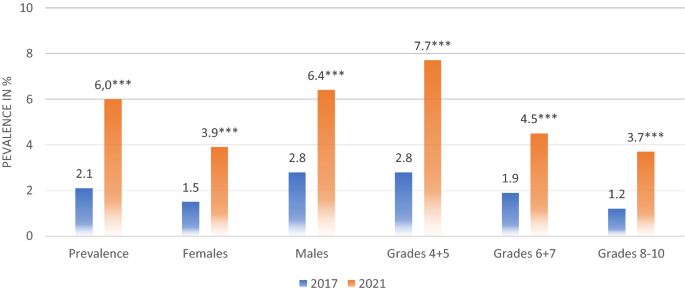

Prevalence of traditional and digital bullying

Before the pandemic, 7.0% (68/972) of the participants reported that they experienced traditional bullying and 2.1% (20/972) reported digital bullying two to three times per month or more. 8.1% (79/972) reported either traditional bullying, digital bullying, or both. During the pandemic, the prevalence was found to be significantly increased to 10.1% (125/1239) for traditional bullying (X 2 = 9.47, df = 4, p < 0.05) and 6.0% (74/1239) for digital bullying (X 2 = 16.18, df = 4, p < 0.01). 11.9% (148/1239) reported that they experienced either traditional bullying, digital bullying, or both. This is significantly higher than before the pandemic (X 2 = 14.26, df = 4, p < 0.01).

Before the pandemic, there was a significant gender difference (X 2 = 11.69, df = 4, p < 0.05) in traditional bullying.4.5% (20/452) of the females and 9.3% (48/520) of the males reported traditional bullying. In digital bullying there was 1.5% (7/452) of the females and 2.8% (13/520) of the males that reported being bullied, thus there was no gender difference (X 2 = 3.64, df = 4, p = 0.46). During the pandemic, 8.9% (51/573) of the females and 11.2% (74/666) of the males reported traditional bullying. Moreover, 3.9% (22/573) of the females and 6.4% (52/666) of the males reported digital bullying. There was no significant gender difference in either traditional or digital bullying during the pandemic (X 2 = 2.54, df = 4, p = 0.64; X 2 = 8.52, df = 4, p = 0.07, respectively).

Before the pandemic, 9.9% (35/354) of the children in grades 4 + 5 reported traditional bullying. Further, 6.5% (24/370) in grades 6 + 7 and 3.6% (9/248) in grades 8–10 reported the same. There was a significant difference between the age groups (F [4,967] = 6.24, p < 0.001). Moreover, 2.8% (10/354) of the children in grades 4 + 5, 1.9% (7/370) in grades 6 + 7, and 1.2% (3/248) of the children in grades 8–10 reported digital bullying. There was a significant difference between age groups also in digital bullying (F [4,967] = 2.62, p < 0.05). During the pandemic, 18.4% (71/387) of the children in grades 4 + 5, 7.8% (30/387) in grades 6 + 7, and 5.2% (24/465) in grades 8–10 reported traditional bullying. There was an effect of age group (F [4,1234] = 14.36, p < 0.001), and grades 4 + 5 reported significantly more bullying compared to grades 8–10 ( p < 0.001) and grades 6 + 7 ( p < 0.001). Moreover, 7.7% (30/387) of the children in grades 4 + 5, 4.5% (17/387) in grades 6 + 7, and 3.7% (17/465) in grades 8–10 reported digital bullying. There was also an effect of age group on digital bullying (F [4, 1234] = 7.24, p < 0.001), and grades 4 + 5 reported significantly more bullying compared to the other age groups ( p < 0.001). An overview of the prevalence of traditional and digital bullying is presented in Figs. 1 and 2 .

Prevalence of traditional bullying. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Prevalence of digital bullying. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Emotional, behavioral, and peer problems

An effect of group was found in three of the four difficulties scales and for total difficulties (emotional problems: F (1,2209) = 91.58, p < 0.001; conduct problems: F (1,2209) = 8.69, p < 0.01; peer problems: F (1,2209) = 45.19, p < 0.001; total difficulties: F (1,2209) = 11.73, p < 0.001; Λ: F = (5,2203) = 1510.96, p < 0.001. The mean was higher in all these scales in the pandemic group compared to the pre-pandemic group. Gender was found to be a significant covariate in emotional problems: F = 30.87, p < 0.001; hyperactivity: F = 12.20, p < 0.001; and total difficulties: F = 44.02, p < 0.001 (Λ: F = 58.81, p < 0.001). Females reported significantly higher means in these three scales compared to males in both groups.

Age group was found to be a significant covariate in emotional problems: F = 59., p < 0.001; peer problems: F = 4.11, p < 0.05; and total difficulties: F = 22.77, p < 0.001 (Λ: F = 15.80, p < 0.001). Emotional problems were found to increase significantly with each age group ( p < 0.001), and the problems were significantly higher in the pandemic group compared to the pre-pandemic group ( p < 0.001). Peer problems were reported to be significantly higher in grades 4 + 5 in the pre-pandemic group compared to the other age groups ( p < 0.05). In the pandemic group, peer problems were found to be significantly higher in grades 8–10 ( p < 0.05). In total difficulties, grades 4 + 5 and grades 8–10 reported significantly higher scores than grades 6 + 7 in the pre-pandemic group. In the pandemic group, the score increased significantly with age ( p < 0.001). An overview of all scale scores (mean and standard deviation (SD) and Cohens d ) is presented in Table 1 .

The impact of COVID-19 variables on subjective life quality

Anxiety was found to significantly correlate in a negative direction with all QoL subscales. All correlations were represented by Pearson’s r below—0.3. The results from the multiple regression model indicated that the independent variables combined explained 8.6% of the variance (R 2 = 0.086, F [6,1232] = 19.39, p < 0.001). All QoL subscales were found to be significant predictors.

Loneliness was found to significantly correlate in a positive direction with all QoL subscales. All correlations were represented by Pearson’s r above 0.3. Emotional well-being (r = 0.59, p < 0.001), relationship to friends (r = 0.51, p < 0.001), and total QoL (r = 0.58, p < 0.001) were found to be highly correlated with loneliness. The results from the regression model indicated that the independent variables combined explained 39.4% of the variance (R 2 = 0.394, F [6,1232] = 133.47, p < 0.001). Emotional well-being (β = 0.37, p < 0.001) and relationship to friends (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) were found to be significant predictors alone.

School functioning

School functioning was found to significantly correlate in a negative direction with all QoL subscales. The results from the regression model indicated that the independent variables combined explained 33.9% of the variance (R 2 = 0.339, F [6,1232] = 105.23, p < 0.001). Relationship to family (β = − 0.07, p < 0.05), relationship to friends (β = 0.13, p < 0.01), relationship to school (β = − 0.22, p < 0.001), and total QoL (β = − 0.48, p < 0.001) were found to be significant predictors alone. The results from the correlations and regression analysis are presented in Table 2 . The correlations between the COVID-19 variables are presented in Table 3 .

This study aimed to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of traditional and digital bullying; emotional, behavioral, and peer problems; and QoL among children living in Northern Norway 1 year into the pandemic. Earlier studies, conducted during the first 3 months of the pandemic, are consistent in showing increased mental health problems and reduced QoL 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 16 . The studies that have explored bullying during the pandemic report more inconsistent results 35 , 36 .

The prevalence of bullying during the pandemic was found to be 10.1% for traditional bullying and 6.0% for digital bullying. There were a significantly increased prevalence in both traditional and digital bullying during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic, which was only partly what was hypothesized. The prevalence from this study is higher than the recent national report from Bakken 27 , who reported 6% and 3%, respectively. This may be because this study measured prevalence both during the school day and outside of school combined. Bakken 27 further reported that the prevalence of bullying was one percentage point lower than the year before. This corresponds with the findings of Vaillancourt et al. 35 , and it suggests that the prevalence of bullying reduced during the pandemic on a national level, which is also documented internationally. The current study, on the other hand, shows the opposite prevalence pattern in the city of Tromsø. This indicates that local differences are relevant on the impact of the pandemic on bullying and that consistent results may be difficult to obtain.

The increased prevalence of digital bullying that was found in this study is consistent with other findings from the pandemic 33 , 34 , and the results are concerning due to the known negative impact 31 . The overall findings on the prevalence of both traditional and digital bullying highlight the importance of implementing and maintaining anti-bullying measures on both national and local levels after the pandemic. Local requirements between areas and schools should be considered and emphasized.

In the pre-pandemic group, there were more males who reported being bullied (both traditional and digital) compared to females. During the pandemic there were no gender differences. The highest prevalence in both traditional and digital bullying was in grades 4 + 5. This is the period when most of the children reported being bullied. Further, the prevalence decreased through grades 6 + 7 and grades 8–10. The same prevalence pattern for the age groups was found in both the pandemic group and the pre- pandemic group. These patterns are also consistent with what other studies have documented 45 .

During the WiT project period (2012–2018), the participating schools placed high priority on anti-bullying measures and activities to increase well-being and life quality for the children at school. The activities were employed locally, by the school leaders, and were different for each school. Some of the schools had anti-bullying discussions and projects within each class. Some schools were mapping areas around the schools were bullying often took place and the teachers were asked to pay extra attention in these areas during their outdoor inspection time. Some of the schools arranged anti-bullying seminars for the teachers, where the parents also were involved. Results from analysis of the entire WiT project period suggested that the prevalence of both traditional and digital bullying decreased year by year. In the first year of the study 10.4% reported being bullied either traditional or digital 46 . In 2017 the prevalence had dropped to 8.1%. Thus, the prevalence of either traditional or digital bullying was higher during the pandemic, at 11.9%, compared to the entire WiT project period.

Previous studies have shown that increased presence and supervision from teachers and other school personnel reduced the prevalence of bullying during the school day 24 . During the pandemic, were school personnel assigned several more areas of responsibility than normal to maintain the infection control measures, such as hygiene measures, ensuring social distance between cohorts, follow-up of vulnerable and chronically ill pupils, and adapting and carrying out pedagogical measures and curriculum in a homeschool format 47 . Due to the isolation and quarantine regulations, the abrasion on the teachers have been sufficiently increased resulting in more absence and sick leave 48 . The shortage of teachers, also called the teacher crisis, left few resources or capacity to ensure a protective social environment for children and adolescents at school. As a result, the normal preventive measures against bullying may not have been maintained, giving the pupils more opportunities to bully.

In line with earlier studies, increased mental health problems were found in the present study as well. The problems included increased emotional symptoms, conduct problems, and peer problems. Hyperactivity has also been reported as an increased behavioral problem during the pandemic 7 , but in this study there was found no difference in the hyperactivity scale between the groups. In general, the females reported more difficulties than males, which also corresponds with earlier findings during the pandemic 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 . Females are more likely to develop a linear decrease in negative mental health problems, such as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder, whereas males are more stable 49 . Age group was also found to be a significant covariate in this study. Emotional symptoms increased with age, which is also in line with what was expected 50 . Peer problems were found to be highest in grades 4 + 5, which was also the age group where most children reported being bullied.

Already before the pandemic outbreak did a range of studies document an increase of emotional problems, clinical diagnostics, and treatment of children and adolescent psychiatric disorders in high-income countries over the past decade. Evidence from low- and middle-income countries are limited 51 . In Norway has the prevalence of self-reported mental health difficulties and registered psychiatric diagnosis increased among children and adolescence since 2010. A report from 2018 described increased emotional and behavioral difficulties each year, especially among females. The most common difficulties are anxiety, depressive, and eating disorder symptoms, but also increased academic performance pressure. In 2010, 7% of children and adolescence in Norway were registered with a psychiatric diagnosis in the primary health care sector in Norway. In 2020 this was increased to 10% and all difficulties tend to increase with age 52 . For example, Bakken 50 report that at age 13 did 5% of males and 13% of females report that they were often bothered by depressive symptoms. At age 18, this was increased to 13% for males and 32% for females.

There are several known risk factors, besides gender, for developing emotional, behavioral and peer problems. Children and adolescents from families with low socioeconomic status, that have a difficult relationship with their parents, have adverse childhood experiences, or have few friends or poor peer relationships, report low well-being at school and/or are victims of bullying have increased risk of reporting mental health difficulties (51). The same risk factors have been associated with increased difficulties during the pandemic 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 16 , 27 and highlight who are in most need of psychosocial support after the pandemic.

The impact of anxiety, loneliness, and self-perceived school functioning on subjective life quality

Since mental health difficulties among children and adolescents were increasing already before the pandemic, it is important to highlight specific variables that has predicted reduced QoL during the pandemic. Increased anxiety, loneliness, and reduced QoL has been found in several studies from the pandemic 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 16 . In the present study we found that both anxiety (specifically about the spread of the virus) and loneliness due to reduced ability to socialize with friend, predicted reduced subjective QoL. Loneliness predicted reduced life quality in emotional well-being and relationship to friends, whereas anxiety predicted reduction in all the KINLD subscales.

Self-perceived school functioning was also found to be a strong predictor of reduced life quality in relationship to friends, family, school, and total QoL. To the best of our knowledge, this is not documented in other studies. Further, a medium correlation between loneliness and school functioning was also documented, which highlights the importance of support and perceived social well-being to function in school. Wang and Degol 22 discussed the quality of interpersonal relationships, such as consistency, frequency, and nature of the relationships formed at school: pupil–teacher relationship, peer relationships, the relationship with the school staff, and the school–home relationship. Positive interpersonal relationships are important for school well-being, academic functioning, and performance. Connectedness, in terms of feeling acceptance, inclusion, belonging, and safety (both physical and emotional) in the school environment, is another important factor that may have been compromised during the pandemic.

Limitations of the study

There are some limitations of the present study that need to be taken into consideration. First, the pre-pandemic group included data from 2017, when ideally the data should have been collected just before the outbreak of the pandemic. As discussed above, an increase of emotional problems was already documented before the pandemic. There may be other factors, in addition to the pandemic, that have influenced the prevalence of bullying and increased emotional, behavioral, and peer problems among the children and adolescents in this study that we have not accounted for.

There are also several biases associated with self-report data and since this study is purely based on self-report measures, we must acknowledge these limitations. First, there is a possibility that participants may have made answers that is more socially accepted among their peers rather than being truthful. All though this bias was addressed in the video that the participants watch before the data collection, there is a possibility that the data can have some degree of inaccuracy anyway. Second, the age range of the participants can be of concern because younger children can have problems in assessing themselves accurately or can have difficulties understanding the questions or how to respond to a self-report measure. This bias is addressed by using validated tools for the targeted age range, and during the data collection there was a teacher present that could help clarify possible confusions in the measure. There are several studies that indicate that children from 5 years of age can provide reliable and sound self-report 53 , 54 , 55 , however we do acknowledge that this is a possible limitation of the data.

Another limitation is that there are also a few differences in the data collection procedures between the pandemic group and the pre- pandemic group. The data from 2021 were collected anonymously, while the data from 2017 were collected from children providing their personal information; therefore, the data required written consent from one of the parents, and data lacking this consent had to be deleted from the material. There are studies that highlight the importance of anonymity to ensure reliable and honest reports on sensitive information such as mental health indicators, peer problems and victimization 56 . This indicate that the participants in the pre- pandemic group may to some degree have under-reported the severity of their mental health issues and peer problems.

The change in response rates between the groups (85% for the pandemic data versus 65% for the pre- pandemic data) may also introduce a bias into the measurements. Furthermore, the results may not be generalizable to all Norwegian children or adolescents, as the study was targeted to a single district in Northern Norway (Tromsø) and lacks the diversity of children and adolescents from across the country. However, the inconsistency in the literature on the prevalence of bullying suggests that results are difficult to generalize.

This study documented increased prevalence of traditional and digital bullying and increased emotional, behavioral, and per problems among school children in Northern Norway during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before. Most of the findings were in line with what was hypothesized, except for the increased prevalence in traditional bullying, which we hypothesized would be reduced. Further, anxiety, loneliness, and self-perceived school functioning were found to predict reduced subjective QoL. To the best of our knowledge, the ability to concentrate at school (both at school and during home-schooling) has not been documented as a predictor for reduced life quality in any other studies that have documented the impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescents.

Implications of this study

The present study suggests systematically providing psychosocial and anti-bullying measures in schools after the pandemic. In Norway, children had a saying during the pandemic: “It will get well” (org. Alt blir bra). However, the findings from this study suggest that it will not get well by itself. In Norway, school owners are required by law to organize a healthy environment that secures and protects all children and adolescents with a safe physical and psychosocial environment 57 . Thus, we advise that both local and national government administrations and school owners implement systematic evidence-based psychosocial measures, increase the focus on the school climate and strengthen the teacher staff with more resources, such as a dedicated psychological adviser that can serve both pupils and teachers. Further, it would be beneficial to enhance and strengthen education on the negative impact of bullying, the impact of mental health issues on school functioning, and the prevention of mental health problems among children and adolescents. Teachers should aim to emotionally support their pupils, as well as provide educational support. Emotional support is especially important for pupils at risk of being vulnerable. Further research is necessary to investigate the implementation and effect of psychosocial and anti-bullying measures in schools. It would also be beneficial to include the experiences of children, parents, teachers, and school leaders to provide a comprehensive illustration of the need for and implementation of psychosocial measures.

The severe findings of increased bullying victimization in this study are an important contribution to a literature that report inconsistent findings 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 . Further, this study support earlier findings of increased emotional difficulties and reduced QoL during the lock-down period 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , and document that this is also the case a year into the pandemic. Self-perceived school functioning has also been identified as an important predictor for QoL, which is a new finding to the existing literature. The methodology and approach of this study has added new perspectives and information on how children and adolescents have been affected by the pandemic.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

NOU 2021: 6. Myndighetenes håndtering av koronapandemien. in Departementenes sikkerhets- og serviceorganisasjon, Teknisk redaksjon. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2021-6/id2844388 (2021).

Golberstein, E., Wen, H. & Miller, B. F. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 174 , 819–820 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Goncalves, A. P. et al. Preliminary findings on the association between mental health indicators and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archiv. Psychiatry Psychother. 22 , 10–19 (2020).

Hafstad, G. S., Sætren, S. S., Wentzel-Larsen, T. & Augusti, E.-M. Adolescents’ symptoms of anxiety and depression before and during the Covid-19 outbreak—A prospective population-based study of teenagers in Norway. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 5 , 1–8 (2021).

Google Scholar

Luijten, M. A. J. et al. The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and social health of children and adolescents. Qual. Life Res. 30 , 2795–2804 (2021).

Ravens-Sieberer, U. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31 , 879–889 (2022).

Xie, X. et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province China. JAMA Pediatr. 174 (9), 898–900 (2020).

Cooper, K. et al. Loneliness, social relationships, and mental health in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 289 (15), 98–104 (2021).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A. & Hafner, E. Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 29 (6), 624–645 (2010).

Bukowski, W. M. & Sandberg, D. Peer relationships and quality of life. Acta Paediatr. 428 , 108–109 (1999).

Dunn, J. Siblings, friends, and the development of social understanding. In Relationship as Development Contexts: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology (eds Collins, A. W. & Lauritsen, B.) 263–279 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999).

Parker, J. G. & Asher, S. R. Peer relationship and later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children at risk?. PsycholBull. 102 , 357–389 (1987).

CAS Google Scholar

McMahon, G., Creaven, A. M. & Gallagher, S. Stressful life events and adolescent well-being: the role of parent and peer relationships. Stress Health 36 , 299–310 (2020).

Helsen, M., Vollenbergh, W. & Meeus, W. Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescent. J. Youth Adolesc. 29 , 319–335 (2000).

Link, B. G. & Phelan, J. Social conditions and fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 35 , 80–94 (1995).

Palgi, Y. et al. The loneliness pandemic: loneliness and other concomitants of depression, anxiety, and their comorbidity during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affec. Disord. 275 (1), 109–111 (2020).

Mikkelsen, H. T. et al. Health-related quality of life is strongly associated with self-efficacy, self-esteem, loneliness, and stress in 14–15-year-old adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18 (352), 1–17 (2020).

Solmi, M. et al. Factors associated with loneliness: an umbrella review of observational studies. J. Affec. Disord. 271 (15), 131–138 (2020).

Wickens, C. M. et al. Loneliness in the COVID-19 pandemic: association with age, gender, and their interaction. J. Psychiatr. Res. 136 , 103–108 (2021).

NOU 2022: 5. Myndighetenes håndtering av koronapandemien—del 2. in Departementenes sikkerhets- og serviceorganisasjon, Teknisk redaksjon. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2022-5/id2910055 (2022).

Folkehelseinstituttet. Koronavirus (SARS-Cov-2)—fakta, råd og tiltak. https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/coronavirus/?chapter=89992 (2022a).

Wang, M.-T. & Degol, J. L. School climate: a review of the construct, measurement, and impact on students’ outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28 , 315–352 (2015).

Menesini, E., Nocentini, A. & Calussi, P. The measurement of cyberbullying: dimensional structure and relative item severity and discrimination. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 14 (5), 267–274 (2011).

Olweus, D. School bullying: development and some important challenges. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9 , 751–780 (2013).

Aurora, T. Measuring bullying with the ‘Life in School’ checklist. Pasto Care Educ. 12 (3), 11–15 (1994).

Rønning, J. A., Handegaard, B. H. & Sourander, A. Self-perceived peer harassment in a community sample of Norwegian school children. Child Abuse Negl. 28 (10), 1067–1079 (2004).

Bakken, A. Ungdata 2021. Nasjonale resultater. OsloMet. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2767874 (2021).

Branwhite, T. Bullying and student distress: Beneath the tip of the iceberg. Educ. Psychol. 14 (1), 59–71 (1994).

Due, P. et al. Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: international comprehensive cross-sectional study in 28 countries. Eur. J. Public Health 15 (2), 128–132 (2015).

Juvonen, J. & Graham, S. Bullying in schools: the power of bullies and the plight or victims. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65 , 159–158 (2014).

Kwan, I. et al. Cyberbullying and children and young people’s mental health: a systematic map of systematic reviews. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23 (2), 72–82 (2020).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Shah, S. G. S., Nogueras, D., van Woerden, H. C. & Kiparoglou, V. The COVID-19 pandemic: a pandemic of lockdown loneliness and the role of digital technology. J. Med. Internet Res. 22 (11), 1–7 (2020).

Barlett, C. P., Simmers, M. M., Roth, B. & Gentile, D. Comparing cyberbullying prevalence and process before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Psychol. 161 (4), 408–418 (2021).

Shin, S. Y. & Choi, Y. J. Comparison of cyberbullying before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 , 1–11 (2021).

Vaillancourt, T. et al. School bullying before and during COVID-19: results from a population-based randomized design. Aggress Behav. 47 (5), 557–569 (2021).

Armitage, R. Bullying during COVID-19: the impact on child and adolescent health. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 71 (704), 122 (2021).

Goodman, R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 40 (20), 1337–1345 (2001).

Heyerdahl, S. SDQ—Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire: en orientering om et nytt spørreskjema for kartlegging av mental helse hos barn og unge, brukt I UNGHUBRO OPPHED og TROFINN. Nor. Epidemiol. 13 (1), 127–135 (2003).

Fogarty, A., Wood, C. E., Giallo, R., Kaufman, J. & Hansen, M. Factors promoting emotional-behavioral resilience and adjustment in children exposed to intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Aust. J. Psychol. 71 (4), 375–389 (2019).

Stone, L. L., Otten, R., Engeles, R. C. M. E., Vermulst, A. A. & Janssens, J. M. A. M. Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strength and difficulties questionnaire for 4–12-year-olds: a review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 13 , 254–274 (2010).

Ravens-Sieberer, U. & Bullinger, M. Assessing health related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content-analysis results. Qual Life Res. 7 (5), 399–407 (1998).

Ravens-Sieberer, U. & Bullinger, M. News from the KINDL-Questionnaire—a new version for adelescents. Qual Life Res. 7 , 653 (1998).

Jozefiak, T., Larsson, B. & Wichstrøm, L. Changes in quality of life among Norwegian school children: a 6-month follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7 , 7 (2009).

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. Research methods in education 8th edn. (Routledge, 2018).

Sentse, M., Kretschmer, T. & Salmivalli, C. The longitudinal interplay between bullying, victimization, and social status: age-related and gender differences. Soc. Dev. 24 (3), 659–677 (2015).

Thorvaldsen, S., Stenseth, A.-M., Egeberg, G., Pettersen, G. O. & Rønning, J. A. Cyber harassment and quality of life1. In Digital Expectations and Experiences in Education (ed. Elstad, E.) 163–182 (SensePublishers, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-648-4_10 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Utdanningsdirektoratet. in Infection control guidelines for upper secondary schools . https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/sikkerhet-og-beredskap/informasjon-om-koronaviruset/smittevernveileder/infection-control-gudielines-for-upper-secondary-schools/ (2021).

Statistisk sentralbyrå. in Sykefravær . http://www.ssb.no/ (2022).

Ohannessian, C. M., Milan, S. & Vannucci, A. Gender differences in anxiety trajectories from middle to late adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 46 , 826–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0619-7 (2017).

Bakken, A. Ungdata 2018. Nasjonale resultater. in OsloMet. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12199/5128 (2018).

Collishaw, S. Annual research review: secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 56 (3), 370–393 (2015).

Folkehelseinstituttet. in Folkehelserapporten—Helsetilstanden i Norge . https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/hin/ (2022b).

Conijn, J. M., Smits, N. & Hartman, E. E. Determining at what age children provide sound self-reports: an illustration of the validity-index approach. Assess 27 (7), 1604–1618 (2020).

Riley, A. W. Evidence that school-age children can self-report on their health. Ambul. Pediatry 4 (4), 371–376 (2004).

Varni, J. W., Limbers, C. A. & Burwinkle, T. M. How young can children reliably and validly self-report their health-related quality of life? An analysis of 8591 children across age groups with the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 5 (1), 1–13 (2007).

Langhinrichsen-Rohlin, J., Arata, C., O`Brien, N., Bowes, D. & Klibert, J. Sensitive research with adolescents: Just how upsetting are self-report surveys anyway?. Violence Vict 21 (4), 410–424 (2006).

Opplæringslova. Lov om grunnskolen og den videregående opplæringa (LOV-1998-07-17-61). in Lovdata . https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1998-07-17-61 (1998).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Universitetsskoleprosjektet in Tromsø and “Well-being in Tromsø” (WiT) that welcomed the project “WiT-2, the Covid-19 edition” during a difficult period for the schools. Special thanks to the contributing schools: Bjerkaker, Fagereng, Gyllenborg, Sommerlyst, Storelva, and Workinmarka. Thanks also to the school leaders who organized and made room for the teachers to meet with us and conduct the data collections, and thanks to all teachers, parents, and pupils for contributing to this study. All contributions are invaluable.

Open access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway (incl University Hospital of North Norway).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Regional Center for Child and Adolescent Mental Health (RKBU North), UiT, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsö, Norway

June T. Forsberg

Department of Education, UiT, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsö, Norway

Steinar Thorvaldsen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.T.F.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, review & editing, resources, project administration, project leader for “Well-being in Tromsø 2021”. S.T.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation of analysis, writing—review & editing, resources, project leader for “Well-being in Tromsø 2012–2018”.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to June T. Forsberg .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Forsberg, J.T., Thorvaldsen, S. The severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bullying victimization, mental health indicators and quality of life. Sci Rep 12 , 22634 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27274-9

Download citation

Received : 28 June 2022

Accepted : 29 December 2022

Published : 31 December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27274-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Social anxiety and bullying victimization in children and early adolescents: the role of developmental period and immigrant status.

- Nicolò Maria Iannello

- Simona Caravita

- Marina Camodeca

Journal of Youth and Adolescence (2024)

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Bullying Victimization and Emotional Symptoms: A Longitudinal Study on Natives and Students With Immigrant Backgrounds

- Maria Chiara Basilici

- Benedetta Emanuela Palladino

- Ersilia Menesini

International Journal of Bullying Prevention (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization Prevalence among Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Campania, Luigi Vanvitelli, 81100 Caserta, Italy.

- 2 Department of Humanities, University of Foggia, 71121 Foggia, Italy.

- PMID: 37239552

- PMCID: PMC10218135

- DOI: 10.3390/ijerph20105825

In light of the alarming results emerging from some studies and reports on the significant increase in aggressive online behaviors among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, the current research aimed at providing a more detailed evaluation of the investigations focusing on the cyberbullying prevalence rates published between 2020 and 2023. To this purpose, systematic searches were conducted on four databases (Web of Science, APA PsycInfo, Scopus and Google Scholar), and following PRISMA guidelines, 16 studies were included and qualitatively reviewed. Although studies were characterized by a large variety in cyberbullying operationalization and measurement, and by different methodologies used for data collection, the prevalence rates of the involvement in cyberbullying and/or cybervictimization generally revealed opposite trends: an increase in many Asian countries and Australia and a decrease in Western countries. The findings were also discussed by considering the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, some suggestions were provided to policy makers for promoting prevention and intervention anti-cyberbullying programs in school contexts.

Keywords: COVID-19; adolescents; children; cyberbullying; cybervictimization; prevalence; systematic review.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- COVID-19* / epidemiology

- Crime Victims*

- Cyberbullying*

Grants and funding

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Psychiatry

Prevalence and related risks of cyberbullying and its effects on adolescent

Gassem gohal.

1 Pediatric Department, Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Ahmad Alqassim

2 Family and Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Ebtihal Eltyeb

Ahmed rayyani.

3 Medical Intern, Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Bassam Hakami

Abdullah al faqih, abdullah hakami, almuhannad qadri, mohamed mahfouz, associated data.

The authors ensure that the data supporting the results of this study are available within the article. The raw data for the study will be obtainable from the corresponding author upon reasonable demand.

Cyberbullying is becoming common in inflicting harm on others, especially among adolescents. This study aims to assess the prevalence of cyberbullying, determine the risk factors, and assess the association between cyberbullying and the psychological status of adolescents facing this problem in the Jazan region, Saudi Arabia.

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 355 students, aged between 12–18 years, through a validated online questionnaire to investigate the prevalence and risk factors of cyberbullying and assess psychological effects based on cyberbullying questionnaire and Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) questions.

The participants in this study numbered 355; 68% of participants were females compared to 32% were males. Approximately 20% of the participants spend more than 12 h daily on the Internet, and the estimated overall prevalence of cyberbullying was 42.8%, with the male prevalence slightly higher than females. In addition, 26.3% of the participants were significantly affected in their academic Performance due to cyberbullying. Approximately 20% of all participants considered leaving their schools, 19.7% considered ceasing their Internet use, and 21.1% considered harming themselves due to the consequences of cyberbullying. There are essential links between the frequency of harassment, the effect on academic Performance, and being a cyber victim.

Conclusions

Cyberbullying showed a high prevalence among adolescents in the Jazan region with significant associated psychological effects. There is an urgency for collaboration between the authorities and the community to protect adolescents from this harmful occurrence.

Introduction

Cyberbullying is an intentional, repeated act of harm toward others through electronic tools; however, there is no consensus to define it [ 1 – 3 ]. With the surge in information and data sharing in the emerging digital world, a new era of socialization through digital tools, and the popularization of social media, cyberbullying has become more frequent than ever and occurs when there is inadequate adult supervision [ 4 , 5 ]. A large study that looked at the incidence of cyberbullying among adolescents in England found a prevalence of 17.9%, while one study conducted in Saudi Arabia found a prevalence of 20.97% [ 6 , 7 ]. Cyberbullying can take many forms, including sending angry, rude, or offensive messages; intimidating, cruel, and possibly false information about a person to others; sharing sensitive or private information (outing); and exclusion, which involves purposefully leaving someone out of an online group [ 8 ]. Cyberbullying is influenced by age, sex, parent–child relationships, and time spent on the Internet [ 9 , 10 ]. Although some studies have found that cyberbullying continues to increase in late adolescence, others found that cyberbullying tends to peak at 14 and 15 years old before decreasing through the remaining years of adolescence [ 11 – 13 ].

The COVID-19 epidemic has impacted the prevalence of cyberbullying since social isolation regulations have reduced face-to-face interaction, leading to a significant rise in the use of social networking sites and online activity. As a result, there was a higher chance of experiencing cyberbullying [ 14 ].

Unlike traditional Bullying, which usually only occurs in school and is mitigated at home, victims of cyberbullying can be contacted anytime and anywhere. Parents and teachers are seen as saviors in cases of traditional Bullying. Simultaneously, in cyberbullying, children tend to be reluctant to tell adults for fear of losing access to their phones and computers, so they usually hide the cyberbullying incident [ 15 ]. Reports show that cyberbullying is a form of harm not easily avoided by the victim. In addition, in the cyber form of Bullying, identification of the victim and the perpetrator is generally challenging compared to traditional Bullying; this makes an accurate estimation of the problem widely contested [ 16 , 17 ].

There is growing evidence that is cyberbullying causes more significant levels of depression, anxiety, and loneliness than traditional forms of Bullying. A meta-analysis examining the association between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents indicates that cyberbullying is more intensely related to suicidal ideation than traditional Bullying [ 18 ]. Moreover, the significant problem is that cyberbullying impacts adolescent due to its persistence and recurrence. A recent report in Saudi Arabia indicated a growing rise in cyberbullying in secondary schools and higher education, from 18% to approximately 27% [ 19 ]. In primary schools and kindergartens in Saudi Arabia, we were not surprised to find evidence that children were unaware that cyberbullying is illegal. Although the study showed an adequate awareness of the problem in our country, Saudi Arabia, there were relatively significant misconceptions [ 20 ].

Adolescents' emotional responses to cyberbullying vary in severity and quality. However, anger, sadness, concern, anxiety, fear, and depression are most common among adolescent cyber victims [ 21 ]. Moreover, cyberbullying may limit students' academic Performance and cause higher absenteeism rates [ 22 ]. Consequently, this study aims to assess the prevalence of cyberbullying, determine the risk factors, and establish the association between cyberbullying and the psychological status of adolescents. We believe our study will be an extension of and significantly add to the literature regarding the nature and extent of cyberbullying in the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia.

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out in the Jazan region, a province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It is located on the tropical Red Sea coast of southwestern Saudi Arabia.

Design and participants

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out in the Jazan region, a province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It is located on the tropical Red Sea coast of southwestern Saudi Arabia. The study targeted adolescents (12–18 years old) who use the Internet to communicate in the Jazan region. The main inclusion criteria are adolescents between 12–18 years who use the Internet and agree to participate; however, it excludes adolescents not matching the inclusion criteria or those refusing to participate in the study. If participants were under 16, the parent and/or legal guardian should be notified. A sample of participants was estimated for this study, and the ideal sample size was calculated to be 385 using the Cochran formula, n = (z) 2 p (1 – p) / d 2 . Where: p = prevalence of cyberbullying 50%, z = a 95% confidence interval, d = error of not more than 5%. A convenience sample was used to recruit the study participants. A self-administrated online questionnaire was used to collect the study information from May to December 2021.

The ethical approval for this study was obtained from The Institute Review Board (IRB) of Jazan University (Letter v.1 2019 dated 08/04/2021). Informed consent was acquired from all participants and was attached to the beginning of the form and mandatory to be read and checked before the participant proceeded to the first part of the questionnaire. For the participants under 16, informed consent was obtained from a parent and legal guardian.

Procedure of data collection and study measures

An Arabic self-administrated online questionnaire was used for this research. This anonymous online survey instrument was based on (Google Forms). The study team distributed the questionnaire to the participants through school teachers. The research team prepared the study questionnaire and chose the relevant cyberbullying scale questions from similar studies [ 5 , 6 ]. The questionnaire was translated by two bilingual professionals to ensure the accuracy and appropriateness of the instrument wording. A panel of experts then discussed and assessed the validity and suitability of the instrument for use on adolescents. The panel also added and edited a few questions to accommodate the local culture of Saudi students. It was validated with a pilot study that included 20 participants. The questionnaire was divided into three main sections. The first part of the questionnaire contains the basic participant information, including gender, age, nationality, school grade, residence, and information about family members and the mother's occupation and education. The mother's level of education was considered as it found that mothers' low levels of education specifically had a detrimental impact on the cyberbullying process [ 23 ]. The second section explores the participant's definition of cyberbullying, questions regarding exposure to cyberbullying as a victim or by bullying another person, and questions considering the possible risk factors behind cyberbullying. The last section explores how cyberbullying affects adolescents psychologically based on the standardized questionnaire Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5). MHI-5 is a well-known, valid, reliable, and brief international instrument for assessing mental health in children and adolescents (such as satisfaction, interest in, and enjoyment of life) and negative aspects (such as anxiety and depression) [ 24 ]. It is composed of five questions, as shown in Table Table1. 1 . There are six options available for each question, ranging from "all the time" (1 point) to "none of the time" (6 points); therefore, the adolescent's score varies between five and 30. These questions assess both negative and positive qualities of mental health, as well as questions about anxiety and depression. By adding all the item scores and converting this score to a scale ranging from 0 to 100, the final MHI-5 score is determined, with lower scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The value for which the sum of sensitivity and specificity was utilized to establish the ideal cut-off score for MHI-5 in many similar studies was reviewed to reach an optimal conclusion. Therefore, we considered all cut-off values with associated sensitivities and specificities of various MHI-5 cut-off points previously employed among adolescents in similar studies and compared them to conclude that MHI-5 = 70 as our cut points. So the presence of depressive symptoms is considered with an MHI-5 cut-off score of ≤ 70 [ 25 ].

Factor Analysis of the Arabic Version of the Mental Health Inventory – 5 (MHI-5) ( n = 355)

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy = 0.700

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, Chi-Square = 739.84 p < 0.001

The Questionnaires were initially prepared in English and then translated into Arabic. A native speaker with fluency in English (with experience in translation) converted the questionnaire from the initial English version into Arabic. Then, we performed a pilot study among 20 participants to ensure the readability and understandability of the questionnaire questions. We also assessed the internal consistency of the questionnaire based on Cronbach’s alpha, which produced an acceptable value of 0.672. The internal consistency for Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) was reported at 0.557. In order to assess the factor structure of the Arabic-translated version of the (MHI-5) questionnaire, a factor analysis was conducted. The factor loading of the instrument is shown in Table Table1. 1 . Using principal component analysis and the varimax rotation method, we found a one-component solution explaining 56.766% of the total variance. All items loaded on the first factor ranged from (0.688 to 0.824), which confirms that a single factor has explained all the items of the scale. In addition, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was found significant ( p < 0.001).

Data presentation & statistical analysis

Simple tabulation frequencies were used to give a general overview of the data. The prevalence of cyberbullying was presented using 95% C.I.s, and the Chi-squared test was performed to determine the associations between individual categorical variables and Mental Health. The univariate and multivariate logistic regression model was derived, and unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (C.I.s) were calculated. A P -value of 0.05 or less was used as the cut-off level for statistical significance. The statistical analysis was completed using SPSS ver. 25.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) software.

The distributed survey targeted approximately 385 students, but the precise number of respondents to the questionnaire was 355 (92% response rate), with 68% of female students responding, compared to 32% of male students. More than half of the respondents were secondary school students, with a nearly equal mix of respondents living in cities and rural areas. Table Table2 2 demonstrates that 20% of the participants spend more than 12 h daily on the Internet and electronic gadgets, while only 13% spend less than two hours.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation

As demonstrated in Table Table3, 3 , the total prevalence of cyberbullying was estimated to be 42.8%, with male prevalence somewhat higher than female prevalence. Additional variables, such as the number of hours spent on the Internet, did not affect the prevalence. Table Table4 4 shows the pattern and experience of being cyberbullied across mental health levels, as measured by the MHI-5.

Prevalence of cyberbullying among adolescents in the Jazan region

# p -value is based on Pearson's Chi-square test, Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval

Pattern and experience of being cyberbullied among adolescents according to a mental health level based on MHI-5

# p -value is based on Pearson's Chi-square test, Abbreviations: MHI-5 = the Mental Health Inventory-5

Academic Performance was significantly affected due to cyberbullying in 26.3% of the participants. Furthermore, approximately 20% of all participants considered leaving their schools for this reason. Moreover, 19.7% of the participants thought of stopping using the Internet and electronic devices, while 21.1% considered harming themselves due to the effects of cyberbullying. Regarding associations between various variables and psychological effects using the MHI-5, there are significant associations between whether the participant has been a cyber victim before (cOR 2.8), the frequency of harassment (cOR 1.9), academic Performance (cOR 6.5), and considering leaving school as a result of being a cyber victim (cOR 3.0). In addition, by using univariate logistic regression analysis, there are significant associations between the psychological effects and the participant's thoughts of getting rid of a bully (cOR 2.8), thinking to stop using electronic devices (cOR 3.0), and considering hurting themselves as the result of cyberbullying (cOR 6.4). In addition, the use of the multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that frequency of harassment was the only statistically significant predictor of mental health among adolescents (aOR 2.8). Other variables continue to have higher (aORs) but without statistical significance. All these results are demonstrated in Table Table4 4 .

Cyberbullying prevalence rates among adolescents vary widely worldwide, ranging from 10% to more than 70% in many studies. This variation results from certain factors, specifically gender involvement, as a decisive influencing factor [ 26 , 27 ]. Our study found a prevalence of 42.8% (95% confidence interval (CI): 37.7–48), which is higher than the median reported prevalence of cyberbullying of 23.0% in a scoping review that included 36 studies conducted in the United States in adolescents aged 12 to 18 years old [ 28 ]. A systematic review found that cyberbullying ranged from 6.5% to 35.4% [ 3 ]. These two studies gathered data before the COVID-19 pandemic. When compared to recent studies, it was found that cyberbullying increased dramatically during the COVID-19 era [ 29 , 30 ]. Subsequently, with the massive mandate of world online communication in teaching and learning, young adolescents faced a large amount of cyberspace exposure with all risk-related inquiries. Psychological distress due to COVID-19 and spending far more time on the Internet are vital factors in this problem, which might be a reasonable explanation for our results.