Home — Essay Samples — History — French and Indian War — The French and Indian War

The French and Indian War

- Categories: French and Indian War India

About this sample

Words: 459 |

Updated: 22 November, 2023

Words: 459 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Works Cited

- Elderfield, J. (1976). The "Wild Beasts": Fauvism and Its Affinities. Museum of Modern Art.

- Flam, J. (1990). Matisse on art. Phaidon Press.

- Freeman, J. (2015). The Fauve Landscape. Yale University Press.

- Gowing, L. (1957). Matisse. Penguin Books.

- Harrison, C., & Wood, P. (Eds.). (2003). Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Blackwell Publishing.

- Hofmann, W. (1988). Fauvism. Benedikt Taschen Verlag.

- Klein, M. (1991). Fauvism. Harry N. Abrams.

- Nerdinger, S. (Ed.). (2016). Matisse-Bonnard: Long Live Painting! Hatje Cantz Verlag.

- Rewald, J. (1978). Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Shanes, E. (2001). Henri Matisse: The Oasis of Matisse. Harry N. Abrams.

Video Version

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Geography & Travel

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 821 words

3 pages / 1308 words

2 pages / 961 words

2 pages / 779 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on French and Indian War

Throughout history there have been many feuds between various nations and tribes. When it comes to studying historical events, you will notice that some of these disputes turned into wars, several of which triggered other [...]

Following the defeat of the French and their Indian allies in the French & Indian War in 1763, very few people would have guessed a massive and destructive civil war would erupt between the colonies and the mother [...]

We always wonder why bad things happen, maybe the answer is right in front of us but we’re just too blind or na?ve to see it. Most would like to think that all people know the difference between right and wrong. The problem is [...]

One of the more impactful means by which the experience of war is recreated for a civilian audience is through the illustration of the human body, with lived experience and relevant literature illustrating war as an entity so [...]

The trials took place in colonial massachusetts. A few young girls were claiming to be possessed by the devil and suspicions began to grow. This caused many people to grow frantic and in order to settle this franticness, a [...]

Cotton was often considered the foundation of the Confederacy. The question this essay will examine is ‘To what extent did cotton affect the outbreak of the Civil War.’In order to properly address the demands of this questions, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

A Clash of Empires: The French and Indian War

Written by: Timothy J. Shannon, Gettysburg College

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the causes and effects of the Seven Years’ War (the French and Indian War)

Suggested Sequencing

Prior to reading this Narrative, students should read the Albany Plan of Union Narrative. This Narrative should be followed by the Wolfe at Quebec and the Peace of 1763 Narrative.

The French and Indian War was the climactic struggle between Great Britain and France for imperial control of North America. The war began in 1754, when a young Virginia militia officer named George Washington engaged in a skirmish with a party of French soldiers, and it ended six years later when the governor-general of New France surrendered to a British army at Montreal. The conflict was part of a much larger global struggle known as the Seven Years’ War that began in 1756 and ended in 1763 among Britain, France, and several other European nations. Although the French and Indian War was only one of several Anglo-French conflicts in North America, it was exceptional for its scale and its influence on the lives of American Indians and colonists.

Unlike many earlier Anglo-French wars, the French and Indian War originated in North America, in a remote region known as the Ohio country. In the early 1750s, this land became the center of a three-way contest among American Indians, the French, and the British. A loose confederacy of Indian nations dominated by the Delawares, Shawnees, and Senecas populated the Ohio country after migrating from other regions taken over by colonists. There they found a new homeland rich with natural resources, especially the animals that supplied the fur trade. British and French traders competed with each other for this business. The Indians generally preferred British trade goods, which were cheaper and more plentiful, but they had better relations with the French because of New France’s effective missionary work and diplomacy among Indian nations living along the Great Lakes. Regardless of their preference for the French or British, the Ohio Indians shared a common desire to keep European soldiers and settlers out of their territory.

Tensions in the Ohio country heated up in 1753, when the French sent troops to fortify the passage from Lake Erie to the Ohio River. This move was intended to cement the French claim to the region and to open a route through the interior of the continent that would connect the French colonies in Canada and Louisiana. Virginia and Pennsylvania had their own designs on the Ohio country. Fur traders from both colonies were active there, and both claimed the Ohio country by right of their original royal charters. Pennsylvania, which lacked a militia because of its Quaker origins, was slow to mobilize against the French, but Virginia acted more forcefully. Its governor, Robert Dinwiddie, was an investor in the Ohio Company, a group of entrepreneurs who hoped to profit by opening western lands to settlers. When he learned that the French were occupying the Ohio country, he sent twenty-one-year-old militia officer George Washington to drive them out.

In his first mission to the Ohio country in 1753, Washington delivered a diplomatic warning to the French, telling them they were encroaching on British territory. The French officers he met politely rebuffed him, and he was disturbed by the efforts he witnessed among the French to win over the Ohio Indians, including his own guide, an influential Seneca named Tanaghrisson. In spring 1754, Governor Dinwiddie sent Washington back to the Ohio country, this time with an army of two hundred militiamen and orders to defend Virginia’s claim to the Forks of the Ohio (modern Pittsburgh). For a guide, Washington again relied on Tanaghrisson, who led him to a party of French soldiers near the British encampment.

In an ill-advised surprise dawn attack, Washington and his men killed several French soldiers and wounded their commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. Washington believed he had prevented a French attack on his own men, but Jumonville insisted he had only been on a diplomatic mission, carrying a message from his commander at the French post Fort Duquesne. His protests were cut short when Tanaghrisson stepped forward and killed him with a tomahawk blow to his skull, a move likely intended to force the British into a more aggressive stance against the French.

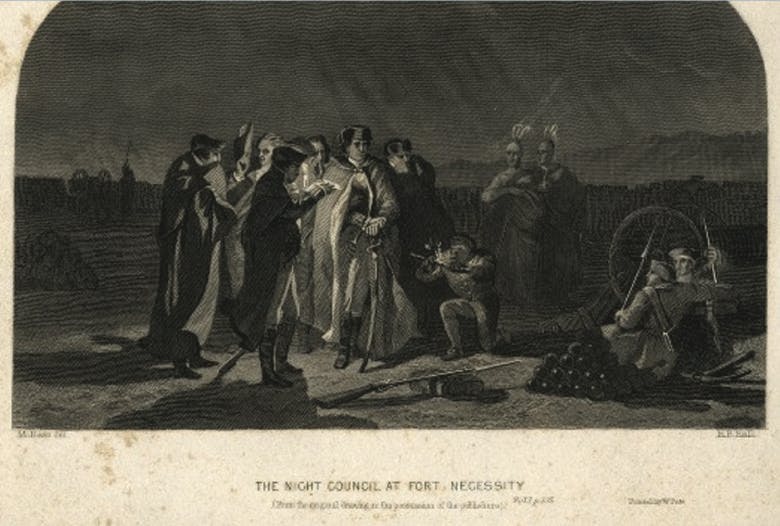

After Jumonville’s death, a shaken Washington had his men build a stockade that he named Fort Necessity, in anticipation of a counterattack from Fort Duquesne. A superior force of French soldiers and Indian warriors soon surrounded the outnumbered and inexperienced Americans. The French and Indians fired on the garrison from covered positions, demoralizing Washington’s men and exhausting his supplies. Washington decided his only option was to surrender, and he claimed he unwittingly signed articles of capitulation, written in French, that described him as responsible for the “assassination” of Jumonville. This inadvertent admission became the basis for the French declaration of war against Britain.

This engraving by an unknown artist depicts an evening council of George Washington at Fort Necessity. Take a closer look at the details the artist includes. Who is attending the council? What resources are available to Washington and his men?

In 1755, the British returned to the Ohio country, this time with an army of regulars and colonists commanded by General Edward Braddock, whom Washington served as an aide-de-camp. Braddock intended to lay siege to Fort Duquesne and then move north to attack the French at Fort Niagara, which guarded the passage from Canada to the Ohio country. Encumbered by artillery and a supply train, Braddock’s troops slowly cut a road through dense wilderness from Fort Cumberland on the Potomac River toward Fort Duquesne. After crossing the Monongahela River on the morning of July 9, Braddock’s army collided with a French and Indian force that took advantage of high ground and cover provided by the surrounding forest to rain their fire on the British. Braddock suffered a fatal wound and Washington narrowly escaped death himself. The destruction of Braddock’s army left the Ohio country firmly in control of the French. Indians allied with the French launched a devastating war against settlements along the Appalachian frontier from Pennsylvania to Virginia.

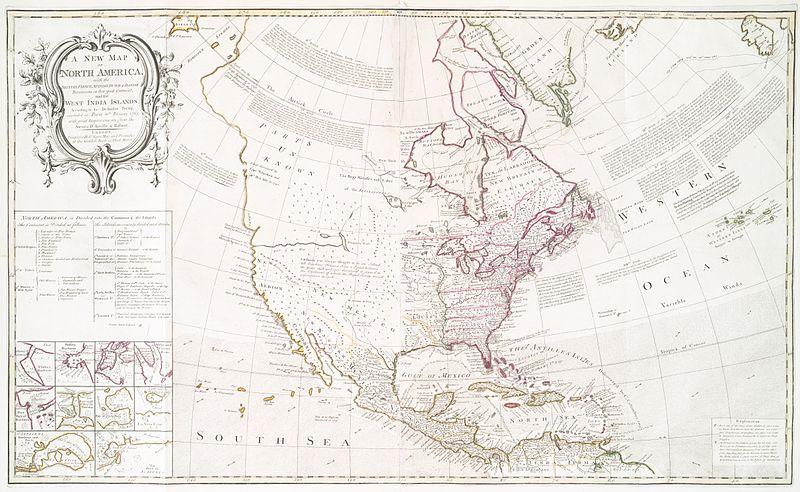

This map depicts the events of the French and Indian War. How much did the war affect the relative strength of Great Britain and France in North America? (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

For the next three years, the British struggled to regain their position in the Ohio country. Promoted to colonel of a regiment of Virginia soldiers, Washington worked feverishly to build fortifications and restore security along the frontier. Like many other colonial Americans, he disliked the British policy that gave seniority to British army officers over American officers, regardless of their respective ranks. In 1758, he worked closely with British General John Forbes as Forbes planned a new expedition into the Ohio country. Washington wanted Forbes to follow Braddock’s route west, but Forbes decided instead to cut a new road west from the Susquehanna River. This route favored Pennsylvania’s claim to the Ohio country, and Washington resented Forbes for it.

In November 1758, Forbes’s army forced the French to abandon Fort Duquesne, but Washington took little pleasure in the victory and soon returned to his home at Mount Vernon to resume his civilian life. Over the course of five years, he had learned much about military leadership and frontier warfare, but his ambitions to become a commissioned officer in the British regular army had been thwarted more often than helped by his British superiors. He had also lost several battles in the early part of the war, but nonetheless, he emerged as a war hero with a growing continental reputation.

Shortly after Forbes’s victory, the British built Fort Pitt on the ruins of Fort Duquesne. This act, along with the British occupation of other French posts in the Great Lakes region, angered the Ohio Indians because they had been promised in 1758 that the British would evacuate their homelands after the war was won. The Indians were now entirely dependent on the British for their trade goods, and the roads built by Braddock and Forbes became routes for settlers to move into the region.

Violence erupted in 1763 when Indians throughout the Great Lakes attacked western British posts and settlements. This conflict, named Pontiac’s War after the Ottawa chief who led the siege of Detroit, caused the British to issue the Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited land sales and settlement west of the Appalachians and kept soldiers stationed on the frontier to restore peace between Indians and colonists. That policy compounded the frustrations of colonists such as George Washington, who believed the Crown was denying them access to the lands they had helped conquer and had been promised as a bounty for their war service. Britain had won the French and Indian War and driven the French out of North America, but as a result, its empire suffered internal tensions that were to lead to revolution. Great Britain also amassed a massive war debt during the conflict and expected the colonies to begin paying more taxes as a share of their defense.

Review Questions

1. To provide defense against a French counterattack, George Washington built a fort called

- Fort Necessity

- Fort Ticonderoga

- Fort Duquesne

- Valley Forge

2. Despite its name, the French and Indian War was fought between

- the French and Indians

- the French and the Spanish

- the French and the Dutch along with their respective American Indian allies

- the French and the British along with their respective American Indian allies

3. George Washington had his first experience of military authority when leading a group of soldiers from

- Pennsylvania

- Massachusetts

4. Another name for the French and Indian War is

- King George’s War

- the Glorious Revolution

- the War of Spanish Succession

- the Seven Years’ War

5. What natural resource was so abundant in the Ohio River Valley that the American Indians, the French, and the British all desired it?

- Fur-bearing animals

6. Why did the French send troops to secure the Ohio country in 1753?

- To connect their imperial strongholds in Canada and Louisiana

- To negotiate a treaty with the Indians

- To build forts to protect French settlers

- To clear the land for farming

Free Response Questions

- Explain the extent to which the French and Indian War was an imperial conflict, as well as a frontier conflict.

- Explain how the French and Indian War changed the relationship between the British and the American colonists.

AP Practice Questions

“[30 September 1759] Cold weather is coming on apace, which will make us look round about us and put [on] our winter clothing, and we shall stand in need of good liquors [in order] to keep our spirits on cold winter’s days. And we, being here within stone walls, are not likely to get liquors or clothes at this time of the year; and although we be Englishmen born, we are debarred [denied] Englishmen’s liberty. Therefore we now see what it is to be under martial law and to be with the [British] regulars who are but little better than slaves to their officers. And when I get out of their [power] I shall take care of how I get in again. . . . 31 [October]. And so now our time has come to an end according to enlistment, but we are not yet [allowed to go] home. . . November 1. The regiments was ordered out . . . to hear what the colonel had to say to them as our time was out and we all swore that we would do no more duty here. So it was a day of much confusion with the regiment.”

Massachusetts soldier’s diary, 1759

1. Which of the following best describes the point of view of the soldier based on the excerpt provided?

- He is dedicated to the cause of the British in the war.

- He resents that he has not received the benefits of Englishmen’s liberty.

- He will re-enlist at the first opportunity.

- He is comfortable that he has all the supplies he needs in the face of oncoming cold weather.

2. Which of the following most accurately describes the impact on the colonies of the conflict described?

- The colonies won their economic independence from England.

- The French gained permanent possession of the Ohio River Valley, ending English claims on the region.

- The English needed the colonies to help pay the cost of their defense and so increased taxation.

- The Great Awakening began to spread into the interior of North America.

Primary Sources

George Washington’s Letter to Governor Robert Dinwiddie: http://www.wvculture.org/history/frenchandindian/17560804washington.html

Virginia Gazette Advertisement: http://www.wvculture.org/history/frenchandindian/17550523virginiagazette.html

Suggested Resources

Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 . New York: Vintage, 2001.

Clary, David A. George Washington’s First War: His Early Military Adventures . New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011.

Preston, David L. Braddock’s Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Shannon, Timothy J. The Seven Years’ War in North America: A Brief History with Documents . Boston: Bedford, 2013.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

French and Indian War

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 29, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Also known as the Seven Years’ War, the French and Indian war marked another chapter in the long imperial struggle between Britain and France. When France’s expansion into the Ohio River valley brought repeated conflict with the claims of the British colonies, a series of battles led to the official British declaration of war in 1756. Boosted by the financing of future Prime Minister William Pitt, the British turned the tide with victories at Louisbourg, Fort Frontenac and the French-Canadian stronghold of Quebec. At the 1763 peace conference, the British received the territories of Canada from France and Florida from Spain, opening the Mississippi Valley to westward expansion.

Why Did the French and Indian War Start?

The Seven Years’ War (called the French and Indian War in the colonies) lasted from 1756 to 1763, forming a chapter in the imperial struggle between Britain and France called the Second Hundred Years’ War.

In the early 1750s, France’s expansion into the Ohio River valley repeatedly brought it into conflict with the claims of the British colonies, especially Virginia. In 1754, the French built Fort Duquesne where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers joined to form the Ohio River (in today’s Pittsburgh), making it a strategically important stronghold that the British repeatedly attacked.

During 1754 and 1755, the French won a string of victories, defeating in quick succession the young George Washington , Gen. Edward Braddock and Braddock’s successor, Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts.

In 1755, Governor Shirley, fearing that the French settlers in Nova Scotia (Acadia) would side with France in any military confrontation, expelled hundreds of them to other British colonies; many of the exiles suffered cruelly. Throughout this period, the British military effort was hampered by lack of interest at home, rivalries among the American colonies and France’s greater success in winning the support of the Indians.

In 1756 the British formally declared war (marking the official beginning of the Seven Years’ War), but their new commander in America, Lord Loudoun, faced the same problems as his predecessors and met with little success against the French and their Indian allies.

The tide turned in 1757 because William Pitt, the new British leader, saw the colonial conflicts as the key to building a vast British empire. Borrowing heavily to finance the war, he paid Prussia to fight in Europe and reimbursed the colonies for raising troops in North America.

British Victory in Canada

In July 1758, the British won their first great victory at Louisbourg, near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. A month later, they took Fort Frontenac at the western end of the river.

In November 1758, General John Forbes captured Fort Duquesne for the British after the French destroyed and abandoned it, and Fort Pitt—named after William Pitt—was built on the site, giving the British a key stronghold.

The British then closed in on Quebec, where Gen. James Wolfe won a spectacular victory in the Battle of Quebec on the Plains of Abraham in September of 1759 (though both he and the French commander, the Marquis de Montcalm, were fatally wounded).

With the fall of Montreal in September 1760, the French lost their last foothold in Canada. Soon, Spain joined France against England, and for the rest of the war Britain concentrated on seizing French and Spanish territories in other parts of the world.

The Treaty of Paris Ends the War

The French and Indian War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in February 1763. The British received Canada from France and Florida from Spain, but permitted France to keep its West Indian sugar islands and gave Louisiana to Spain. The arrangement strengthened the American colonies significantly by removing their European rivals to the north and south and opening the Mississippi Valley to westward expansion.

Impact of the Seven Years’ War on the American Revolution

The British crown borrowed heavily from British and Dutch bankers to bankroll the war, doubling British national debt. King George II argued that since the French and Indian War benefited the colonists by securing their borders, they should contribute to paying down the war debt.

To defend his newly won territory from future attacks, King George II also decided to install permanent British army units in the Americas, which required additional sources of revenue.

In 1765, parliament passed the Stamp Act to help pay down the war debt and finance the British army’s presence in the Americas. It was the first internal tax directly levied on American colonists by parliament and was met with strong resistance.

It was followed by the unpopular Townshend Acts and Tea Act , which further incensed colonists who believed there should be no taxation without representation. Britain’s increasingly militaristic response to colonial unrest would ultimately lead to the American Revolution .

Fifteen years after the Treaty of Paris, French bitterness over the loss of most of their colonial empire contributed to their intervention on the side of the colonists in the Revolutionary War.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The French and Indian War (1754-1763): Its Consequences

The surrender of Montreal on September 8, 1760, signaled an end to all major military operations between Britain in France in North America during the French and Indian War. Although the guns had fallen silent in Canada and the British colonies, it was still yet to be determined just how or when the Seven Years’ War, still raging throughout the world, would end. What resulted from this global conflict and the French and Indian War shaped the future of North America.

By 1762, the Seven Years’ War, fought in Europe, the Americas, West Africa, India, and the Philippines, had worn the opposing sides in the conflict down. The combatants (Britain, Prussia, and Hanover against France, Spain, Austria, Saxony, Sweden, and Russia) were ready for peace and a return to the status quo . Imperialist members of the British Parliament did not want to yield the territories gained during the war, but the other faction believed that it was necessary to return a number of France’s antebellum holdings in order to maintain a balance of power in Europe. This latter measure would not, however, include France’s North American territories and Spanish Florida.

On February 10, 1763, over two years after the fighting had ended in North America, hostilities officially ceased with the signing of the Treaty of Paris between Britain, France, and Spain. The fate of America’s future had been placed on a new trajectory, and as famously asserted by 19 th century historian, Francis Parkman, “half the continent had changed hands at the scratch of a pen.” France’s North American empire had vanished.

The treaty granted Britain Canada and all of France’s claims east of the Mississippi River. This did not, however, include New Orleans, which France was allowed to retain. British subjects were guaranteed free rights of navigation on the Mississippi as well. In Nova Scotia, Fortress Louisbourg remained in Britain’s hands. A colonial provincial expeditionary force had captured the stronghold in 1745 during King George’s War, and much to their chagrin, it was returned to the French as a provision of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle (1748). That would not be the case this time around. In the Caribbean, the islands of Saint Vincent, Dominica, Tobago, Grenada, and the Grenadines would remain in British hands. Another bug acquisition for His Majesty’s North American empire came from Spain in the form of Florida. In return, Havana was given back to the Spanish. This gave Britain total control of the Atlantic Seaboard from Newfoundland all the way down to the Mississippi Delta.

The loss of Canada, economically, did not greatly harm France. It had proved to be a money hole that cost the country more to maintain than it actually returned in profit. The sugar islands in the West Indies were much more lucrative, and to France’s pleasure, Britain returned Martinique and Guadeloupe. Although His Most Christian Majesty’s influence in North America had receded, France did retain a tiny foothold in Newfoundland for fishing. Britain allowed the French to keep its rights to cod in the Grand Banks, as well as the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon off the southern coast.

The inhabitants of the British colonies in North America were jubilant upon hearing the results of the Treaty of Paris. For nearly a century they had lived in fear of the French colonists and their Native American allies to the north and west. Now France’s influence on the continent had been expelled and they could hope to live out their lives in peace and autonomously without relying on Britain’s protection.

The consequences of the French and Indian War would do more to drive a wedge in between Britain and her colonists more so than any other event up to that point in history. During the Seven Years’ War, Britain’s national debt nearly doubled, and the colonies would shoulder a good portion of the burden of paying it off. In the years that followed, taxes were imposed on necessities that the colonists considered part of everyday life—tea, molasses, paper products, etc.... Though proud Englishmen, the colonists viewed themselves as partners in the British Empire, not subjects . King George III did not see it this way. These measures were met with various degrees of opposition and served as the kindling that would eventually contribute to igniting the fires of revolution.

That tinder that would eventually be lit the following decade also came in the form of the land west of the Appalachian Mountains, which had been heavily fought over during the war. As British traders moved westward over the mountains, disputes erupted between them and the Native Americans (previously allied with French) who inhabited the region. Overpriced goods did not appeal to the Native Americans, and almost immediately tensions arose. For many in the British military and the colonies, this land had been conquered and rested within His Majesty’s dominion. Therefore, the territory west of the Appalachians was not viewed as shared or Native land—it was rightfully open for British trade and settlement. The Native Americans did not respond accordingly.

What transpired next has gone down in history as Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763-1764) and involved members of the Seneca, Ottawa, Huron, Delaware, and Miami tribes. The various uprisings and uncoordinated attacks against British forts, outposts, and settlements in the Ohio River Valley and

along the Great Lakes that occurred, ravaged the frontier. Although a handful of forts fell, two key strongholds, Forts Detroit and Pitt, did not capitulate. In an attempt to quell the rebellion against British authority, the Proclamation of 1763 was issued. The French settlements north of New York and New England were consolidated into the colony of Quebec, and Florida was divided into two separate colonies. Any land that did not fall within the boundaries of these colonies, which would be governed by English Law, was granted to the Native Americans. Pontiac’s Rebellion eventually came to an end.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 further alienated the British colonists. Many sought to settle the west, and even Pennsylvania and Virginia had already claimed lands in the region. The proclamation prohibited the colonies from further issuing any grants. Only representatives of the Crown could negotiate land purchases with the Native Americans. Just as France had boxed the colonies into a stretch along the east coast, now George III was doing the same.

The French and Indian War had initially been a major success for the thirteen colonies, but its consequences soured the victory. Taxes imposed to pay for a massive national debt, a constant struggle with Native Americans over borders and territories, and the prohibition of expansion to the west fueled an ever-increasing “American” identity. As the years following the French and Indian War drug on, the colonists—already 3,000 miles away from Britain—grew further and further apart from the mother country.

Further Reading:

- Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754 - 1766 : Fred Anderson

- Bloody Mohawk: The French and Indian War & American Revolution on New York's Frontier : Richard J. Berleth

- The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America : Walter R. Borneman

- The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies 1760-1785 : Don Cook

- A Few Acres Of Snow: The Saga Of The French And Indian Wars : Robert Leckie

- Braddock's Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution : David Preston

On the Precipice

Who Were the Sons and Daughters of Liberty?

Jumonville Glen

You may also like.

- Modern History

The French and Indian War: The conflict that set the stage for the American Revolution

The French and Indian War, spanning from 1754 to 1763, was a momentous conflict that forever altered the landscape of North America.

Not merely a territorial battle between the British and the French, this war was a complex clash involving a diverse cast of Native American tribes, each allying with one side or the other based on their own strategic interests.

As part of the larger global conflict known as the Seven Years' War, the French and Indian War has been aptly dubbed the "true first world war".

It began as a local dispute over land ownership in the Ohio River Valley, but quickly escalated into a fierce and bloody struggle.

At stake was not only the vast, resource-rich wilderness, but also the balance of power in North America and, to a larger extent, the world.

The colonisation of North America by Europeans

In the centuries leading up to the French and Indian War, the vast expanse of North America had been a stage for the struggle of empires.

While various Native American tribes had lived there for thousands of years, the 15th and 16th centuries saw an influx of European explorers and settlers, drawn to the New World by tales of abundant resources and potential wealth.

Two of the most powerful colonizers were Britain and France, each establishing a series of colonies along the eastern seaboard.

While the British colonies thrived mainly on agriculture and trade, the French developed a robust fur trade in the north, especially in the region known as New France, which encompassed parts of what is now Canada and the midwestern United States.

The different economic, political, and religious objectives of these colonies created a volatile mixture of competition and suspicion.

Native American tribes, diverse in culture and language, were inevitably drawn into these colonial struggles. Some tribes allied with the French, like the Huron and the Algonquin, who were integral to their fur trade.

Others, like the Iroquois Confederacy, maintained a more complicated relationship with the British, marked by both trade partnerships and territorial disputes.

By the mid-18th century, the tension between these European powers had begun to strain under the weight of expanding colonial ambitions, particularly in the resource-rich Ohio River Valley.

As British and French settlers encroached on lands that Native Americans considered theirs, tribal alliances shifted, and rivalries intensified.

What caused the French and Indian War?

The French and Indian War was ignited by a combination of economic, political, and territorial disputes between the British and French colonial powers, further complicated by their alliances with various Native American tribes.

One of the main catalysts was the struggle over the Ohio River Valley, a vast territory teeming with fur-bearing animals and fertile land that promised wealth and growth.

Both the French, who had established a network of forts in the region, and the British, who had issued land grants to companies like the Ohio Company of Virginia, claimed the region.

As both sides began to enforce their claims, the area became a tinderbox ready to ignite.

Meanwhile, the fur trade, a significant part of the colonial economy, exacerbated these territorial disputes.

Both the British and French sought control over the fur trade routes and alliances with the Native American tribes who were integral to the fur trade industry.

Tribes were often drawn into the disputes, as their alliances with the European powers often depended on the tribes' own strategic and economic interests.

Religious and political differences also played a part. The largely Protestant British colonies and the predominantly Catholic New France had long-standing tensions rooted in the religious conflicts of Europe.

These religious differences were further inflamed by political rivalries, as both the British and French monarchies sought to expand their global influence.

Finally, the war was a product of escalating tensions in the larger global context. The French and Indian War was, in fact, the North American theater of the Seven Years' War, a worldwide conflict involving several European powers.

The disputes in North America were a reflection of the broader rivalries and power struggles playing out on the global stage.

The key players in the war

The course of the French and Indian War was significantly influenced by a host of major figures from both European powers as well as Native American tribes.

Their decisions and actions would shape the conflict and its aftermath, leaving a lasting imprint on North American history.

A young George Washington emerged as one of the war's key figures, serving in the Virginia militia and taking part in several pivotal engagements.

His experiences during the war, especially his leadership and diplomacy with Native American tribes, would later prove vital during the American Revolution and his presidency.

For the British, General Edward Braddock was another significant figure. Although he died in the disastrous Battle of the Monongahela in 1755, his defeat highlighted the difficulties of European-style warfare in the wilderness of North America, which would influence future British military strategies.

On the French side, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm stands out as a major figure. As commander of the French forces in North America, Montcalm fought a series of battles against the British, including the crucial Battle of Quebec, where he lost his life but left a lasting legacy.

François Gaston de Lévis , Montcalm's second in command, also played a significant role.

After Montcalm's death, Lévis took over command and continued to resist British forces until the fall of Montreal in 1760.

Among the Native American leaders, Tanaghrisson , a leader of the Seneca tribe, was a notable figure.

Known as the "Half-King," he played a crucial role in the beginning of the war, including participating in the initial skirmishes with George Washington.

What happened during the war?

The French and Indian War, a conflict marked by fierce combat, diplomatic maneuvering, and shifting alliances, featured several key battles and events that shaped the course of the war.

The spark that ignited the war was the Battle of Fort Necessity in 1754. After a young George Washington and his forces skirmished with a French patrol in the region, the French counterattacked, leading to the construction and subsequent surrender of Fort Necessity by Washington's forces.

This encounter marked the beginning of hostilities and set the stage for larger conflicts.

The war turned in favor of the British with the Battle of Louisbourg in 1758. The British, led by General Jeffery Amherst, laid siege to the fortress of Louisbourg, a key French stronghold guarding the entrance to the St. Lawrence River.

The fall of Louisbourg marked a turning point in the war, giving the British control over the key waterways, cutting off French supply routes, and paving the way for an assault on Quebec.

The pivotal Battle of Quebec in 1759, known as the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, was perhaps the most significant battle of the war.

The British, led by General James Wolfe, launched a daring assault on Quebec, the capital of New France. Wolfe's forces defeated the French army commanded by Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, despite both commanders dying in the battle.

The British capture of Quebec signaled the beginning of the end for French rule in North America.

How the war ended: Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on February 10, 1763, marked the official end of the French and Indian War.

The agreement had profound consequences for the geopolitical landscape of North America, cementing Britain's status as the dominant colonial power and leading to significant territorial changes.

Negotiations for the treaty involved several European powers, including Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal, and stretched on for months.

As part of the treaty, France ceded nearly all its territories in North America to Britain, marking the end of French colonial rule in the region.

The vast territories that France surrendered included Canada and the lands east of the Mississippi River, with the exception of New Orleans, which France gave to Spain as compensation for Spain's loss of Florida to Britain.

The French retained control of a few small islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and were granted fishing rights off the coast of Newfoundland.

In addition, France managed to keep its Caribbean sugar islands, which were more profitable than its vast North American territories.

While Britain emerged as the clear victor, the Treaty of Paris was met with mixed reactions.

In the American colonies, the removal of the French threat led to increased colonial expansion and friction with Native American tribes.

In Britain, the costs of maintaining the newly acquired territories and military outposts led to increased taxation in the colonies, sowing the seeds of discontent that would eventually erupt into the American Revolution.

Why the French and Indian War was so significant

The French and Indian War had profound and wide-ranging impacts on the British colonies in North America.

It reshaped the political landscape, strained economic resources, and altered relationships both within the colonies and with Native American tribes.

Politically, the war marked a major shift in the balance of power in North America. With the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the French ceded most of their territories to the British, leaving Britain as the dominant colonial power in North America.

This newfound power, however, also brought increased responsibilities and challenges, including managing the vast western territories and maintaining peace with Native American tribes.

Economically, the war left the British empire with enormous war debts. To recover some of these costs, the British parliament passed a series of new taxes and tariffs on the American colonies, such as the Sugar Act and the Stamp Act.

These policies were met with fierce resistance from the colonists, who protested with slogans like "no taxation without representation."

These protests marked the beginning of a rift between the colonies and the British government, planting seeds of discontent that would eventually lead to the American Revolution.

The war also had a significant impact on relations between the colonies and Native American tribes.

Despite Britain's victory, Native American tribes, particularly those allied with the French, continued to resist British expansion into the western territories.

This resistance culminated in Pontiac's Rebellion in 1763, a widespread Native American uprising against British military presence in the Great Lakes region.

The uprising prompted the British government to issue the Proclamation of 1763, forbidding colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, further stoking colonial resentment.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The French and Indian War

By christopher gill, unit objective.

This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core State Standards–based teaching resources. These units were developed to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. Through a step-by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze any primary or secondary source material.

In this unit students will develop a thorough knowledge of the French and Indian War through several primary documents. These documents will teach the students about specific aspects of the French and Indian War and the complex nature of this major event in colonial and indigenous history. Students will demonstrate learning by combining prior knowledge and primary sources to dig deeper and discover more relevant information related to the coalitions and contentions that led to the violence of the French and Indian War.

This unit focuses on the conflict that took place in North America from 1754 to 1763 between the French and English and their respective powerful Native American allies. It is sometimes also referred to as the Seven Years’ War, but will be identified as the French and Indian War for this unit. The French and Indian War officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

This activity can be used in most US history classrooms. I would recommend that this lesson/unit in its current form be used in seventh through twelfth grades. The primary document analysis template ( In His Own Words ), reading and analysis template ( Document Analysis & Learning ), and document comparison template ( Making Connections & Detecting Differences ) can be used across many grade levels, from elementary to AP classes, if adapted with different documents or appropriate curriculum-level activities.

This activity should take between three and five class periods depending on the time allotted by the teacher for pre-activity curriculum-based learning, document analysis, and possible follow-up activities. If classroom time is an issue, various aspects of this unit can be used independently.

This lesson could work well in several different units of American history or civics. Themes related to the French and Indian War include: American Indian history, the age of exploration, European and Native American relations, colonial and Native American relations, colonization, the thirteen colonies, imperialism, land ownership, the Seven Years’ War, English and French colonial conflict, the Iroquois Confederacy, early conflicts between the colonies and England, causes of the American Revolution, differences between European and American Indian societies and cultures, and several other related topics. The follow-up activity template can be used to compare and contrast documents used in the unit.

Introduction

The age of exploration and the ensuing colonization of the Western Hemisphere brought long-standing conflicts into new and unfamiliar lands for European imperial nations. Whether peaceful or hostile, European contact directly changed the lives of the indigenous populations in the Americas forever.

Throughout the French and Indian War during the mid-eighteenth century, powerful indigenous nations fought against and allied with European powers for specific military, economic, political, and social purposes. For each faction, there were multiple motivations at play during these conflicts. Some of the major motivations behind the French and Indian War included, but were not limited to, protection of ancestral lands, acquisition of new territory and imperial power, and self-preservation. This unit will use primary documents to help students understand the complicated nature of defeating adversaries and building coalitions on the frontier during the French and Indian War.

The documents and graphic organizers presented in this unit should be used as enrichment pieces to teach students about the French and Indian War. The primary sources will help students understand the viewpoints of some of the major players during the French and Indian War. They will show the historical circumstances that helped shape or destroy native and European alliances as well as the brutal and confusing nature of wilderness warfare during this period. These documents alone cannot fully tell the story of the causes, events, and aftermath of the entire war, but should serve as glimpses into the realities of the time.

- Primary Document Analysis: Canassatego – In His Own Words

- Graphic Organizer: Document Analysis and Learning

- Analyzing a Political Cartoon: Benjamin Franklin – "Join or Die"

- Primary Document Analysis: Robert Moses – In His Own Words

- Primary Document Analysis: Minavavana – In His Own Words

- Graphic Organizer: Making Connections – Document to Document

- Graphic Organizer: Detecting Differences – Document to Document

- Smartboard, ELMO, or overhead projector

The students will use the Primary Document Analysis activities to locate and cite specific vocabulary words.

Students will be using close-reading strategies to analyze excerpts from two speeches by Canassatego, chief of the Onondaga Nation and a diplomat for the Iroquois Confederacy. Students will demonstrate their understanding by "graffiting"/annotating the text; completing primary document analysis templates; participating in in-depth analysis of rhetoric and discourse, cooperative learning, and document-based questioning; and creating and responding to higher-order questions based on the text.

Sample questions:

- How do Chief Canassatego and his people feel about the land? Cite specific evidence from the document that helps support your answer.

- According to Chief Canassatego, what happens to the goods they are given for the land they sell? Cite specific evidence from the document that helps support your answer.

- How does this document portray the relationship between the Iroquois people and the colonists? Cite specific evidence from the document that helps support your answer.

- According to Chief Canassatego, what are the major problems that his people face? Cite specific evidence from the document that helps support your answer.

- How does Canassatego feel about the alliance between the tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy? Cite specific evidence from the document that helps support your answer.

- What advice does Canassatego give to the colonists? Cite specific evidence from the document that helps support your answer.

- Did the colonists eventually follow Chief Canassatego’s advice? Give specific evidence from your knowledge of American history.

The teacher will tell students that they will be analyzing a primary source by Canassatego, chief of the Onondaga Nation and a diplomat for the Iroquois Confederacy. Discuss with the students the importance of critically analyzing the specific words and sentiments expressed directly in the document.

The teacher should also tell students that this document is a representation of the relationships between the Iroquois Nation and the colonists, specifically in Pennsylvania. Chief Canassatego’s speeches took place several years before the French and Indian War but show the direct relationships and sometimes turbulent alliances among the Iroquois Confederation, the colonists in Pennsylvania, and the British Crown.

- Primary Document Analysis: Canassatego – In His Own Words . Source: Carl Van Doren, Indian Treaties Printed by Benjamin Franklin, 1736–1762 (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1938). First three paragraphs from "The Treaty Held with the Indians of the Six Nations, at Philadelphia, in July, 1742," p. 27; the last paragraph from "A Treaty with the Indians of the Six Nations, June 1744," p. 78. This book reprinting several pamphlets published by Benjamin Franklin can be found online at the Internet Archive at http://archive.org/details/indiantreatiespr00vand .

- Analyzing a Political Cartoon: Benjamin Franklin – "Join or Die" Source: Pennsylvania Gazette , May 9, 1754, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

- The teacher will have to be sure the students are appropriately prepared for this unit/lesson. Students should have a good understanding of pre-Columbian indigenous history, the age of exploration, wars of European colonialism around the world, cultural diffusion, imperialism, and other topics relevant to world and US history.

- The teacher will hand out Canassatego – In His Own Words . Make certain students understand that the text has been excerpted from two different speeches for this lesson. Explain the purpose and use of ellipses.

- Teacher will "share read" the Canassatego document with the class. In a shared read, the teacher will introduce the text to the students by beginning to read the document aloud. After a few sentences, the teacher will ask the students to join in reading the remainder of the document in unison. The teacher will continue reading along with the students and use the proper pronunciation and intonation as a model. The share-reading exercise ensures that students will become more familiar with the articulation and discourse of the document and helps English language learners and struggling readers. Share reading will also help students hear, see, and read aloud the major sentiments and the point of view presented in the document prior to their close-reading exercise.

- The teacher will pair students based on ability level for a Think, Pair, Share using Canassatego – In His Own Words. The student pairings can be assigned by the teacher based on the needs of the students and their levels. Each student in the pairing will focus on half of the document, which can be assigned by the teacher or selected by the students.

- Students will "close read" their portion of the text and fill in the organizers with relevant ideas, vocabulary, quotations, and meanings. The teacher should stress the importance of critically analyzing the specific words and sentiments expressed directly in the document.

- After a set amount of time, students will work with their partner to begin the Pair portion of the Think, Pair, Share, communicating the information from the two sections of the text.

- After a set amount of time, each student will present to the class at least one piece of information their partner shared with them during the Pair portion of the Think, Pair, Share. This information should be displayed on the Smartboard, ELMO, or overhead projector.

- The teacher should pose several higher-order questions (see examples in the Objective section of this lesson) to encourage a classroom discussion based on the text.

- The teacher will hand out Graphic Organizer: Document Analysis and Learning and, in pairs, the students will fill in the organizer using specific evidence from the document.

Extension (optional)

Students will use what they learned from Canassatego – In His Own Words to fill in the graphic organizer Document Analysis and Learning for homework, if it was not completed in class. Students will receive a copy of Benjamin Franklin – "Join or Die" to complete as homework. They should be informed they will need to use their homework for the next lesson.

Students will be using Benjamin Franklin’s "Join or Die" political cartoon and the diary of Robert Moses, a member of the New Hampshire militia during the French and Indian War, in this lesson. Students will demonstrate their understanding by "graffiting"/annotating the text; completing primary document analysis templates; participating in in-depth analysis of rhetoric and discourse, cooperative learning, and document-based questioning; and creating and responding to higher-order questions based on the text.

- What are some of the major symbols in Benjamin Franklin’s "Join or Die" cartoon and what do you think they mean? Cite specific evidence from the text that helps support your answer.

- Is the "Join or Die" political cartoon related to the words of Chief Canassatego? If so, how? Cite specific evidence from the text that helps support your answer.

- According to Robert Moses’s diary, what is it like fighting in the French and Indian War? Cite specific evidence from the text that helps support your answer.

- According to Robert Moses’s diary, what role are Native Americans playing in the French and Indian War? Cite specific evidence from the text that helps support your answer.

- When you read Robert Moses’s diary, what images pop into your head? Why? Cite specific evidence from the text that helps support your answer.

- If you compare Benjamin Franklin’ "Join or Die" and the excerpts from Robert Moses’s diary, are there any direct connections? Are there any differences? Cite specific evidence from the text that helps support your answer.

- What do you think the most interesting lines in the diary are? What did you find compelling about those lines? Cite specific evidence from the text that supports your answer.

The second lesson will connect Benjamin Franklin’s political cartoon "Join or Die" with excerpts from Robert Moses’s diary. These two documents have the common theme of colonial unity embedded within them. It may take the students time to find this thread because overall there are more differences than similarities between the documents.

There are several other major reasons to use Robert Moses’s diary: it describes the chaos and brutal nature of the French and Indian War as well as the role that Native American allies played for both the English and the French during the war.

The teacher should discuss with the students the importance of critically analyzing the specific words and sentiments expressed directly in the document.

- Primary Document Analysis: Robert Moses – In His Own Words . Source: Robert Moses, Diary, July 12–September 15, 1755. . The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04944 . The full text of the diary is provided as a pdf for the teacher’s reference.

Procedure (Instruction and Assessment)

- The teacher and students will review the homework from the first day’s lesson, Analyzing a Political Cartoon: Benjamin Franklin – "Join or Die," or complete the analysis in class if it was not assigned as homework. Students and teacher should present their answers on the Smartboard, ELMO, or overhead projector.

- The teacher will hand out Robert Moses – In His Own Words . Make certain that students understand that the original text has been excerpted for this lesson. Explain the purpose and use of ellipses. Punctuation has been added and spelling has been modernized in these excerpts.

- Teacher will "share read" the Robert Moses document with the class.

- The teacher will pair students based on ability level for a Think, Pair, Share based on Robert Moses Diary – In His Own Words . Each student in the pairing will focus on half of the document, which can be assigned by the teacher or selected by the students.

- Students will "close read" and fill in the graphic organizers with relevant ideas, vocabulary, quotations, and meanings from their specifically assigned half of the document on their own. The teacher should stress the importance of critically analyzing the specific words and sentiments expressed directly in the document.

- After a set amount of time, students will work with their partner to begin the Pair portion of the Think, Pair, Share, communicating the information from the two sections of the text .

- After a set amount of time, each student will present at least one piece of information their partner shared with them during the Pair portion of the Think, Pair, Share. Students and teacher should be able to present their answers on the Smartboard, ELMO, or overhead projector.

Students will be using a statement made by Chippewa ( Anishinaabeg or Ojibwe ) chief Minavavana ( Mihnehwehna or Minweweh ), an ally of the French. Students will demonstrate their understanding by "graffiting"/annotating the text; completing primary document analysis templates; participating in in-depth analysis of rhetoric and discourse, cooperative learning, and document-based questioning; and creating and responding to higher order questions based on the text.

- How does Minavavana feel about the English defeating the French? What does the English victory mean to Minavavana? Cite specific examples from the text that support your answer.

- According to Minavavana, what must his warriors do even though the war may have ended? Cite specific evidence from the text that helps support your answer.

- According to Chief Minavavana, what are the two ways the "spirits of the slain" can be satisfied? Cite specific evidence from the text that will help support your answer.

- What does Chief Minavavana think of the king of England? The king of France? Cite specific evidence from the text that will help support your answer.

- How does Minavavana feel about the English fur trader Alexander Henry? Why do you think he feels this way? Cite specific evidence from the text that will support your answer.

In this lesson, students will explore the changing nature of the relationship between indigenous people and their European allies. In this document, Chippewa/Ojibwe Chief Minavavana reminds a visiting English trader, Alexander Henry, that his people may have defeated the French but will never defeat Minavavana’s people. The document shows the nature of the war, the allegiance that the Chippewa/Ojibwe people had with the French, the military culture of the Chippewa/Ojibwe people, the relationship between indigenous nations and fur traders, and the expansion of the English into French territory as the war came to an end.

- Primary Document Analysis: Minavavana – In His Own Words . Source: Alexander Henry, Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories, between the Years 1760 and 1776 (New York: I. Riley, 1809), 44–45. Complete publication is available on Google Books at http://books.google.com/books?id=WjnGWp-zufAC&source=gbs_navlinks_s .

- Graphic Organizer: Document Analysis and Learning

- The teacher will hand out Minavavana – In His Own Words. Make certain that students understand that the original text has been excerpted for this lesson. Explain the purpose and use of ellipses.

- The teacher will "share read" the Minavavana document with the class.

- The teacher will pair students based on ability level for a Think, Pair, Share based on Minavavana – In His Own Words. Each student in the pairing will focus on half of the document, which can be assigned by the teacher or selected by the students.

- Students will "close read" and fill in the graphic organizers with relevant ideas, vocabulary, quotations, and meanings from their half of the document on their own. The teacher should stress the importance of critically analyzing the specific words and sentiments expressed directly in the document.

- After a set amount of time, students will work with their partner to begin the Pair portion of the Think, Pair, Share, communicating the information from their own half of the document.

- After a set amount of time, each student will present at least one piece of information their partner shared with them during the Pair portion of the Think, Pair, Share. Students and teacher should present their answers on the Smartboard, ELMO, or overhead projector.

- The teacher should pose several higher-order questions to encourage a classroom discussion based on the text.

- The teacher will hand out Graphic Organizer: Document Analysis and Learning and, in pairs, the students will fill in the organizer using specific evidence from the document. This can be done in class or as homework.

Follow-Up Activities

- Students will analyze and compare the documents presented in the unit. Students will use Making Connections – Document to Document and Detecting Differences – Document to Document .

- Students will research and create a project where they must find and research at least four primary documents that are related to American Indian tribes and the American Revolution.

- Students will research and create a project where they must find and research at least four primary documents that show a direct correlation between the end of the French and Indian War and the beginning of turmoil between the colonies and England.

- Students will create a thesis statement for a DBQ essay and will use all of the documents from this unit to prove their thesis in a detailed DBQ essay.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Milestones: 1750–1775

French and indian war/seven years’ war, 1754–63.

The French and Indian War was the North American conflict in a larger imperial war between Great Britain and France known as the Seven Years’ War. The French and Indian War began in 1754 and ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. The war provided Great Britain enormous territorial gains in North America, but disputes over subsequent frontier policy and paying the war’s expenses led to colonial discontent, and ultimately to the American Revolution.

The French and Indian War resulted from ongoing frontier tensions in North America as both French and British imperial officials and colonists sought to extend each country’s sphere of influence in frontier regions. In North America, the war pitted France, French colonists, and their Native allies against Great Britain, the Anglo-American colonists, and the Iroquois Confederacy, which controlled most of upstate New York and parts of northern Pennsylvania. In 1753, prior to the outbreak of hostilities, Great Britain controlled the 13 colonies up to the Appalachian Mountains, but beyond lay New France, a very large, sparsely settled colony that stretched from Louisiana through the Mississippi Valley and Great Lakes to Canada. (See Incidents Leading up to the French and Indian War and Albany Plan )

The border between French and British possessions was not well defined, and one disputed territory was the upper Ohio River valley. The French had constructed a number of forts in this region in an attempt to strengthen their claim on the territory. British colonial forces, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Washington, attempted to expel the French in 1754, but were outnumbered and defeated by the French. When news of Washington’s failure reached British Prime Minister Thomas Pelham-Holles, Duke of Newcastle, he called for a quick undeclared retaliatory strike. However, his adversaries in the Cabinet outmaneuvered him by making the plans public, thus alerting the French Government and escalating a distant frontier skirmish into a full-scale war.

The war did not begin well for the British. The British Government sent General Edward Braddock to the colonies as commander in chief of British North American forces, but he alienated potential Indian allies and colonial leaders failed to cooperate with him. On July 13, 1755, Braddock died after being mortally wounded in an ambush on a failed expedition to capture Fort Duquesne in present-day Pittsburgh. The war in North America settled into a stalemate for the next several years, while in Europe the French scored an important naval victory and captured the British possession of Minorca in the Mediterranean in 1756. However, after 1757 the war began to turn in favor of Great Britain. British forces defeated French forces in India, and in 1759 British armies invaded and conquered Canada.

Facing defeat in North America and a tenuous position in Europe, the French Government attempted to engage the British in peace negotiations, but British Minister William Pitt (the elder), Secretary for Southern Affairs, sought not only the French cession of Canada but also commercial concessions that the French Government found unacceptable. After these negotiations failed, Spanish King Charles III offered to come to the aid of his cousin, French King Louis XV, and their representatives signed an alliance known as the Family Compact on August 15, 1761. The terms of the agreement stated that Spain would declare war on Great Britain if the war did not end before May 1, 1762. Originally intended to pressure the British into a peace agreement, the Family Compact ultimately reinvigorated the French will to continue the war, and caused the British Government to declare war on Spain on January 4, 1762, after bitter infighting among King George III’s ministers.

Despite facing such a formidable alliance, British naval strength and Spanish ineffectiveness led to British success. British forces seized French Caribbean islands, Spanish Cuba, and the Philippines. Fighting in Europe ended after a failed Spanish invasion of British ally Portugal. By 1763, French and Spanish diplomats began to seek peace. In the resulting Treaty of Paris (1763), Great Britain secured significant territorial gains in North America, including all French territory east of the Mississippi river, as well as Spanish Florida, although the treaty returned Cuba to Spain.

Unfortunately for the British, the fruits of victory brought seeds of trouble with Great Britain’s American colonies. The war had been enormously expensive, and the British government’s attempts to impose taxes on colonists to help cover these expenses resulted in increasing colonial resentment of British attempts to expand imperial authority in the colonies. British attempts to limit western expansion by colonists and inadvertent provocation of a major Indian war further angered the British subjects living in the American colonies. These disputes ultimately spurred colonial rebellion, which eventually developed into a full-scale war for independence.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Ross Douthat

The War That Made Our World

By Ross Douthat

Opinion Columnist

Two hundred and sixty-six years ago this month, a column of British regulars commanded by Gen. Edward Braddock was cut to pieces by French soldiers and their Native American allies in the woods just outside today’s Pittsburgh. The defeat turned into a rout when Braddock was shot off his horse, leaving the retreat to be managed by a young colonial officer named George Washington, whose own previous foray into the region had lit the tinder for the war.

This was the beginning of the French and Indian War (also known, much less poetically, as the Seven Years’ War), which I thought as a boy was the most interesting war in all of history.

I had encountered it originally through a public television version of “The Last of the Mohicans,” but I soon found that the real conflict exceeded even James Fenimore Cooper’s romantic imagination: the complexity of forest warfare and the diversity of the combatants on both sides, colonial, European and Native; the majesty of the geographic setting, especially the lakes, mountains and defiles of upstate New York; the ridiculous melodrama of the culminating battle at Quebec, with a wee-hours cliff-scaling that led to a decisive showdown in which both commanders were mortally wounded, James Wolfe in victory and Louis-Joseph de Montcalm in defeat.

In school the war faded into the background of my history classes. In world history it was folded into the larger categories of colonial warfare and endless Anglo-French conflict; in American history it was treated mostly as a prelude to the real business of the American Revolution. (Not only Washington but also Ben Franklin and a long list of future Revolutionary-era officers, from Daniel Morgan to Charles Lee, played roles in Braddock’s doomed campaign.)

But returning to the 1750s as an adult reader of history — and as a columnist trying to offer constructive thoughts about the history wars in K-12 education — I think my childhood self was basically correct. The war that evicted the French from North America was not only incredibly fascinating but also one of history’s most important wars. Indeed, from a certain perspective, it was more important than the American War of Independence: The Revolution merely determined in what form Anglo-America would spread to embrace continental empire and global power, while the French and Indian War determined whether that continent-spanning America would come into being at all.

As a kid, I — a good patriotic American and stalwart New Englander — naturally rooted for the British and the American colonists, from their early string of setbacks at the hands of Montcalm and other canny French commanders through their eventual triumphant invasion of New France. It was particularly easy to identify with the neurasthenic Wolfe, the victor at Quebec, whose self-dramatization and battlefield martyrdom fit with a 9-year-old’s idea of generalship.

For an adult, though, reading books like Fred Anderson’s “Crucible of War,” the best 21st-century history of the conflict, or Alan Taylor’s “American Colonies” for the bigger picture of North American empire, it’s easy enough to end up rooting for the French.

First, because they were obvious underdogs — New France had less than a fifteenth of the population of the 13 colonies, it was constantly being cut off from its motherland by the British Navy, and it’s something of a miracle that it lasted for as long and won as many victories as it did.

But also because the French empire in North America represented an unusual model of European colonization: The combination of the smaller, scattered population, the harsher climate and the distinctive vision of figures like Samuel de Champlain and the French Jesuits all contributed to a friendlier relationship with Native American populations than obtained in the English colonies. (For a Francophilic supplement to Anderson and Taylor, I recommend David Hackett Fischer’s “Champlain’s Dream” and Kevin Starr’s “Continental Ambitions.”)

So a world where the French somehow held on to their territories might have been more Catholic (obviously a good thing) while offering more possibilities for Indigenous influence, power and survival than the world where England simply won the continent.

There’s a terribly poignant moment at the end of Anderson’s “Crucible,” when tribes of the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley, under the Ottawa leader Pontiac and others, begin to rise against the British shortly after the French retreated from North America. The British imagine that French agents must still be around stirring up trouble, but the reality is that the Native Americans still understand themselves to be in a relationship with the French king and imagine that their war can help bring France back to their aid. But no: They’re alone now with Anglo-America, and foredoomed.

Imagining an alternative timeline, a history in which New France endures and a more, well, “French and Indian” civilization takes shape in the Great Lakes region, isn’t exactly the stuff of the patriotic American education that I wrote about last weekend.

But it also makes a poor fit with contemporary progressive pieties, in which organized Christianity is a perpetual scapegoat for the mistreatment of Native peoples — since it was arguably the power of the church and the Catholic ancien régime in New France, relative to the greater egalitarianism, democracy and secular ambition in the English colonies, that helped foster a more humane relationship between the French colonizers and the Native American population.

Once you recognize that kind of deep historical complexity, you can go in two directions. Along one path lies a kind of cynicism about almost every aspect of the past, where the reader of history is encouraged to basically root for nobody, and the emphasis is always on the self-interest lying underneath every expression of idealism. The French might have modeled what seemed like a kindlier form of colonization, but they were only following their own self-interest as greedy traders and proselytizing Catholic zealots . The New England colonies might have pioneered what seemed like an impressive form of egalitarian democracy, but they achieved their wide distribution of property by ruthlessly crushing the Pequot and the Wampanoag.