How to Write a Thesis, According to Umberto Eco

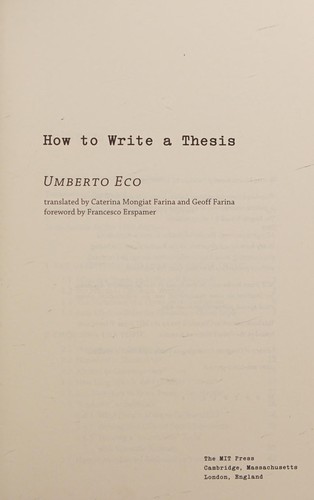

In 1977, three years before Umberto Eco’s groundbreaking novel “ The Name of the Rose ” catapulted him to international fame, the illustrious semiotician published a funny and unpretentious guide for his favorite audience: teachers and their students. Now translated into 17 languages (it finally appeared in English in 2015), “How to Write a Thesis” delivers not just practical advice for writing a thesis — from choosing the right topic (monograph or survey? ancient or contemporary?) to note-taking and mastering the final draft — but meaningful lessons that equip writers for a lifetime outside the walls of the classroom. “Your thesis is like your first love” Eco muses. “It will be difficult to forget. In the end, it will represent your first serious and rigorous academic work, and this is no small thing.”

“Full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it,” praised one critic, “the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own.” An excerpt from that chapter can be read below.

Once we have decided to whom to write (to humanity, not to the advisor), we must decide how to write, and this is quite a difficult question. If there were exhaustive rules, we would all be great writers. I could at least recommend that you rewrite your thesis many times, or that you take on other writing projects before embarking on your thesis, because writing is also a question of training. In any case, I will provide some general suggestions:

You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write,

The pianist Wittgenstein, brother of the well-known philosopher who wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicusthat today many consider the masterpiece of contemporary philosophy, happened to have Ravel write for him a concerto for the left hand, since he had lost the right one in the war.

Write instead,

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Since Paul was maimed of his right hand, the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the famous philosopher, author of the Tractatus. The pianist had lost his right hand in the war. For this reason the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

Do not write,

The Irish writer had renounced family, country, and church, and stuck to his plans. It can hardly be said of him that he was a politically committed writer, even if some have mentioned Fabian and “socialist” inclinations with respect to him. When World War II erupted, he tended to deliberately ignore the tragedy that shook Europe, and he was preoccupied solely with the writing of his last work.

Rather write,

Joyce had renounced family, country, and church. He stuck to his plans. We cannot say that Joyce was a “politically committed” writer even if some have gone so far as describing a Fabian and “socialist” Joyce. When World War II erupted, Joyce deliberately ignored the tragedy that shook Europe. His sole preoccupation was the writing of Finnegans Wake.

Even if it seems “literary,” please do not write,

When Stockhausen speaks of “clusters,” he does not have in mind Schoenberg’s series, or Webern’s series. If confronted, the German musician would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the series has ended. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. On the other hand Webern followed the strict principles of the author of A Survivor from Warsaw. Now, the author of Mantra goes well beyond. And as for the former, it is necessary to distinguish between the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio agrees: it is not possible to consider this author as a dogmatic serialist.

You will notice that, at some point, you can no longer tell who is who. In addition, defining an author through one of his works is logically incorrect. It is true that lesser critics refer to Alessandro Manzoni simply as “the author of the Betrothed,” perhaps for fear of repeating his name too many times. (This is something manuals on formal writing apparently advise against.) But the author of The Betrothed is not the biographical character Manzoni in his totality. In fact, in a certain context we could say that there is a notable difference between the author of The Betrothed and the author of Adelchi , even if they are one and the same biographically speaking and according to their birth certificate. For this reason, I would rewrite the above passage as follows:

When Stockhausen speaks of a “cluster,” he does not have in mind either the series of Schoenberg or that of Webern. If confronted, Stockhausen would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the end of the series. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. Webern, by contrast, followed the strict principles of Schoenberg, but Stockhausen goes well beyond. And even for Webern, it is necessary to distinguish among the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio also asserts that it is not possible to think of Webern as a dogmatic serialist.

You are not e. e. cummings. Cummings was an American avant-garde poet who is known for having signed his name with lower-case initials. Naturally he used commas and periods with great thriftiness, he broke his lines into small pieces, and in short he did all the things that an avant-garde poet can and should do. But you are not an avant-garde poet. Not even if your thesis is on avant-garde poetry. If you write a thesis on Caravaggio, are you then a painter? And if you write a thesis on the style of the futurists, please do not write as a futurist writes. This is important advice because nowadays many tend to write “alternative” theses, in which the rules of critical discourse are not respected. But the language of the thesis is a metalanguage , that is, a language that speaks of other languages. A psychiatrist who describes the mentally ill does not express himself in the manner of his patients. I am not saying that it is wrong to express oneself in the manner of the so-called mentally ill. In fact, you could reasonably argue that they are the only ones who express themselves the way one should. But here you have two choices: either you do not write a thesis, and you manifest your desire to break with tradition by refusing to earn your degree, perhaps learning to play the guitar instead; or you write your thesis, but then you must explain to everyone why the language of the mentally ill is not a “crazy” language, and to do it you must use a metalanguage intelligible to all. The pseudo-poet who writes his thesis in poetry is a pitiful writer (and probably a bad poet). From Dante to Eliot and from Eliot to Sanguineti, when avant-garde poets wanted to talk about their poetry, they wrote in clear prose. And when Marx wanted to talk about workers, he did not write as a worker of his time, but as a philosopher. Then, when he wrote The Communist Manifesto with Engels in 1848, he used a fragmented journalistic style that was provocative and quite effective. Yet again, The Communist Manifesto is not written in the style of Capital, a text addressed to economists and politicians. Do not pretend to be Dante by saying that the poetic fury “dictates deep within,” and that you cannot surrender to the flat and pedestrian metalanguage of literary criticism. Are you a poet? Then do not pursue a university degree. Twentieth-century Italian poet Eugenio Montale does not have a degree, and he is a great poet nonetheless. His contemporary Carlo Emilio Gadda (who held a degree in engineering) wrote fiction in a unique style, full of dialects and stylistic idiosyncrasies; but when he wrote a manual for radio news writers, he wrote a clever, sharp, and lucid “recipe book” full of clear and accessible prose. And when Montale writes a critical article, he writes so that all can understand him, including those who do not understand his poems.

Begin new paragraphs often. Do so when logically necessary, and when the pace of the text requires it, but the more you do it, the better.

Write everything that comes into your head , but only in the first draft. You may notice that you get carried away with your inspiration, and you lose track of the center of your topic. In this case, you can remove the parenthetical sentences and the digressions, or you can put each in a note or an appendix. Your thesis exists to prove the hypothesis that you devised at the outset, not to show the breadth of your knowledge.

Use the advisor as a guinea pig. You must ensure that the advisor reads the first chapters (and eventually, all the chapters) far in advance of the deadline. His reactions may be useful to you. If the advisor is busy (or lazy), ask a friend. Ask if he understands what you are writing. Do not play the solitary genius.

Do not insist on beginning with the first chapter . Perhaps you have more documentation on chapter 4. Start there, with the nonchalance of someone who has already worked out the previous chapters. You will gain confidence. Naturally your working table of contents will anchor you, and will serve as a hypothesis that guides you.

Do not use ellipsis and exclamation points, and do not explain ironies . It is possible to use language that is referential or language that is figurative . By referential language, I mean a language that is recognized by all, in which all things are called by their most common name, and that does not lend itself to misunderstandings. “The Venice-Milan train” indicates in a referential way the same object that “The Arrow of the Lagoon” indicates figuratively. This example illustrates that “everyday” communication is possible with partially figurative language. Ideally, a critical essay or a scholarly text should be written referentially (with all terms well defined and univocal), but it can also be useful to use metaphor, irony, or litotes. Here is a referential text, followed by its transcription in figurative terms that are at least tolerable:

[ Referential version :] Krasnapolsky is not a very sharp critic of Danieli’s work. His interpretation draws meaning from the author’s text that the author probably did not intend. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky sees a symbolic expression that alludes to poetic activity. One should not trust Ritz’s critical acumen, and one should also distrust Krasnapolsky. Hilton observes that, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he adds, “Truly, two perfect critics.”

[ Figurative version :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the sharpest critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is putting words into Danieli’s mouth. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets it as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky plays the symbolism card and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight, but Krasnapolsky should also be handled with care. As Hilton observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon. Truly, two perfect critics.”

You can see that the figurative version uses various rhetorical devices. First of all, the litotes: saying that you are not convinced that someone is a sharp critic means that you are convinced that he is not a sharp critic. Also, the statement “Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight” means that he is a modest critic. Then there are the metaphors : putting words into someone’s mouth, and playing the symbolism card. The tourist brochure and the Lenten sermon are two similes , while the observation that the two authors are perfect critics is an example of irony : saying one thing to signify its opposite.

Now, we either use rhetorical figures effectively, or we do not use them at all. If we use them it is because we presume our reader is capable of catching them, and because we believe that we will appear more incisive and convincing. In this case, we should not be ashamed of them, and we should not explain them . If we think that our reader is an idiot, we should not use rhetorical figures, but if we use them and feel the need to explain them, we are essentially calling the reader an idiot. In turn, he will take revenge by calling the author an idiot. Here is how a timid writer might intervene to neutralize and excuse the rhetorical figures he uses:

[ Figurative version with reservations :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the “sharpest” critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is “putting words into Danieli’s mouth.” Consider Danieli’s line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky “plays the symbolism card” and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a “prodigy of critical insight,” but Krasnapolsky should also be “handled with care”! As Hilton ironically observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a vacation brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he defines them (again with irony!) as two models of critical perfection. But all joking aside …

I am convinced that nobody could be so intellectually petit bourgeois as to conceive a passage so studded with shyness and apologetic little smiles. Of course I exaggerated in this example, and here I say that I exaggerated because it is didactically important that the parody be understood as such. In fact, many bad habits of the amateur writer are condensed into this third example. First of all, the use of quotation marks to warn the reader, “Pay attention because I am about to say something big!” Puerile. Quotation marks are generally only used to designate a direct quotation or the title of an essay or short work; to indicate that a term is jargon or slang; or that a term is being discussed in the text as a word, rather than used functionally within the sentence. Secondly, the use of the exclamation point to emphasize a statement. This is not appropriate in a critical essay. If you check the book you are reading, you will notice that I have used the exclamation mark only once or twice. It is allowed once or twice, if the purpose is to make the reader jump in his seat and call his attention to a vehement statement like, “Pay attention, never make this mistake!” But it is a good rule to speak softly. The effect will be stronger if you simply say important things. Finally, the author of the third passage draws attention to the ironies, and apologizes for using them (even if they are someone else’s). Surely, if you think that Hilton’s irony is too subtle, you can write, “Hilton states with subtle irony that we are in the presence of two perfect critics.” But the irony must be really subtle to merit such a statement. In the quoted text, after Hilton has mentioned the vacation brochure and the Lenten sermon, the irony was already evident and needed no further explanation. The same applies to the statement, “But all joking aside.” Sometimes a statement like this can be useful to abruptly change the tone of the argument, but only if you were really joking before. In this case, the author was not joking. He was attempting to use irony and metaphor, but these are serious rhetorical devices and not jokes.

You may observe that, more than once in this book, I have expressed a paradox and then warned that it was a paradox. For example, in section 2.6.1, I proposed the existence of the mythical centaur for the purpose of explaining the concept of scientific research. But I warned you of this paradox not because I thought you would have believed this proposition. On the contrary, I warned you because I was afraid that you would have doubted too much, and hence dismissed the paradox. Therefore I insisted that, despite its paradoxical form, my statement contained an important truth: that research must clearly define its object so that others can identify it, even if this object is mythical. And I made this absolutely clear because this is a didactic book in which I care more that everyone understands what I want to say than about a beautiful literary style. Had I been writing an essay, I would have pronounced the paradox without denouncing it later.

Always define a term when you introduce it for the first time . If you do not know the definition of a term, avoid using it. If it is one of the principal terms of your thesis and you are not able to define it, call it quits. You have chosen the wrong thesis (or, if you were planning to pursue further research, the wrong career).

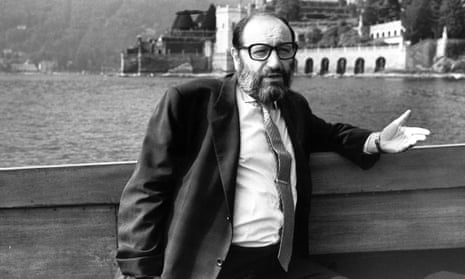

Umberto Eco was an Italian novelist, literary critic, philosopher, semiotician, and university professor. This article is excerpted from his book “ How to Write a Thesis .”

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

How to write a thesis

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

979 Previews

55 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station14.cebu on December 20, 2022

How to Write a Thesis

By umberto eco translated by caterina mongiat farina and geoff farina, category: self-improvement & inspiration.

Mar 06, 2015 | ISBN 9780262527132 | 5-3/8 x 8 --> | ISBN 9780262527132 --> Buy

Feb 27, 2015 | ISBN 9780262328760 | 5-3/8 x 8 --> | ISBN 9780262328760 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Mar 06, 2015 | ISBN 9780262527132

Feb 27, 2015 | ISBN 9780262328760

Buy the Ebook:

- Barnes & Noble

- Books A Million

- Google Play Store

About How to Write a Thesis

The wise and witty guide to researching and writing a thesis, by the bestselling author of The Name of the Rose —now published in English for the first time. Learn the art of the thesis from a giant of Italian literature and philosophy—from choosing a topic to organizing a work schedule to writing the final draft. By the time Umberto Eco published his best-selling novel The Name of the Rose , he was one of Italy’s most celebrated intellectuals, a distinguished academic, and the author of influential works on semiotics. Some years before that, Eco published a little book for his students, in which he offered useful advice on all the steps involved in researching and writing a thesis. Since then, it has been translated into 17 languages—and is now for the first time presented in English. Eco’s approach is anything but dry and academic. He not only offers practical advice but also considers larger questions about the value of the thesis-writing exercise in six different parts: • The Definition and Purpose of a Thesis • Choosing the Topic • Conducting the Research • The Work Plan and the Index Cards • Writing the Thesis • The Final Draft Eco advises students how to avoid “thesis neurosis” and he answers the important question “Must You Read Books?” He reminds students “You are not Proust” and “Write everything that comes into your head, but only in the first draft.” Of course, there was no Internet in 1977, but Eco’s index card research system offers important lessons about critical thinking and information curating for students of today who may be burdened by Big Data. Irreverent and often hilarious, How to Write a Thesis is unlike any other writing manual and belongs on the bookshelves of students, teachers, writers, and Eco fans everywhere.

Product Details

Category: self-improvement & inspiration, you may also like.

Write Great Fiction – Plot & Structure

Authority and Freedom

How to Write a Letter

Writing for Story

The Writer’s Practice

Writer’s Digest Guide to Magazine Article Writing

The Elements of Eloquence

Writing Fantasy & Science Fiction

Writing & Selling Short Stories & Personal Essays

Music Theory, 3E

How to Write a Thesis is full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it, illustrated with lucid examples and—significantly—explanations of why, by one of the great researchers and writers in the post-war humanities … Best of all, the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own.

How to Write a Thesis remains valuable after all this time largely thanks to the spirit of Eco’s advice. It is witty but sober, genial but demanding—and remarkably uncynical about the rewards of the thesis, both for the person writing it and for the enterprise of scholarship itself…. Some of Eco’s advice is, if anything, even more valuable now, given the ubiquity and seeming omniscience of our digital tools…. Eco’s humor never detracts from his serious intent. And anyway, even the sardonic pointers on cheating are instructive in their way.

Eco is a first-rate storyteller and unpretentious instructor who thrives on describing the twists and turns of research projects as well as how to avoid accusations of plagiarism.

The book’s enduring appeal—the reason it might interest someone whose life no longer demands the writing of anything longer than an e-mail—has little to do with the rigors of undergraduate honors requirements. Instead, it’s about what, in Eco’s rhapsodic and often funny book, the thesis represents: a magical process of self-realization, a kind of careful, curious engagement with the world that need not end in one’s early twenties. ‘Your thesis,’ Eco foretells, ‘is like your first love: it will be difficult to forget.’ By mastering the demands and protocols of the fusty old thesis, Eco passionately demonstrates, we become equipped for a world outside ourselves—a world of ideas, philosophies, and debates.

Well beyond the completion of the thesis, Eco’s manual makes for pleasant reading and is deserving of a place on the desks of scholars and professional writers. Even sections such as that recommending the combinatory system of handwritten index cards, while outdated in the digital age, can propose a helpful exercise in critical thinking, and add a certain vintage appeal to the book.

How to Write a Thesis has become a classic.

Visit other sites in the Penguin Random House Network

Raise kids who love to read

Today's Top Books

Want to know what people are actually reading right now?

An online magazine for today’s home cook

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Guide to Thesis Writing That Is a Guide to Life

“How to Write a Thesis,” by Umberto Eco, first appeared on Italian bookshelves in 1977. For Eco, the playful philosopher and novelist best known for his work on semiotics, there was a practical reason for writing it. Up until 1999, a thesis of original research was required of every student pursuing the Italian equivalent of a bachelor’s degree. Collecting his thoughts on the thesis process would save him the trouble of reciting the same advice to students each year. Since its publication, “How to Write a Thesis” has gone through twenty-three editions in Italy and has been translated into at least seventeen languages. Its first English edition is only now available, in a translation by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina.

We in the English-speaking world have survived thirty-seven years without “How to Write a Thesis.” Why bother with it now? After all, Eco wrote his thesis-writing manual before the advent of widespread word processing and the Internet. There are long passages devoted to quaint technologies such as note cards and address books, careful strategies for how to overcome the limitations of your local library. But the book’s enduring appeal—the reason it might interest someone whose life no longer demands the writing of anything longer than an e-mail—has little to do with the rigors of undergraduate honors requirements. Instead, it’s about what, in Eco’s rhapsodic and often funny book, the thesis represents: a magical process of self-realization, a kind of careful, curious engagement with the world that need not end in one’s early twenties. “Your thesis,” Eco foretells, “is like your first love: it will be difficult to forget.” By mastering the demands and protocols of the fusty old thesis, Eco passionately demonstrates, we become equipped for a world outside ourselves—a world of ideas, philosophies, and debates.

Eco’s career has been defined by a desire to share the rarefied concerns of academia with a broader reading public. He wrote a novel that enacted literary theory (“The Name of the Rose”) and a children’s book about atoms conscientiously objecting to their fate as war machines (“The Bomb and the General”). “How to Write a Thesis” is sparked by the wish to give any student with the desire and a respect for the process the tools for producing a rigorous and meaningful piece of writing. “A more just society,” Eco writes at the book’s outset, would be one where anyone with “true aspirations” would be supported by the state, regardless of their background or resources. Our society does not quite work that way. It is the students of privilege, the beneficiaries of the best training available, who tend to initiate and then breeze through the thesis process.

Eco walks students through the craft and rewards of sustained research, the nuances of outlining, different systems for collating one’s research notes, what to do if—per Eco’s invocation of thesis-as-first-love—you fear that someone’s made all these moves before. There are broad strategies for laying out the project’s “center” and “periphery” as well as philosophical asides about originality and attribution. “Work on a contemporary author as if he were ancient, and an ancient one as if he were contemporary,” Eco wisely advises. “You will have more fun and write a better thesis.” Other suggestions may strike the modern student as anachronistic, such as the novel idea of using an address book to keep a log of one’s sources.

But there are also old-fashioned approaches that seem more useful than ever: he recommends, for instance, a system of sortable index cards to explore a project’s potential trajectories. Moments like these make “How to Write a Thesis” feel like an instruction manual for finding one’s center in a dizzying era of information overload. Consider Eco’s caution against “the alibi of photocopies”: “A student makes hundreds of pages of photocopies and takes them home, and the manual labor he exercises in doing so gives him the impression that he possesses the work. Owning the photocopies exempts the student from actually reading them. This sort of vertigo of accumulation, a neocapitalism of information, happens to many.” Many of us suffer from an accelerated version of this nowadays, as we effortlessly bookmark links or save articles to Instapaper, satisfied with our aspiration to hoard all this new information, unsure if we will ever get around to actually dealing with it. (Eco’s not-entirely-helpful solution: read everything as soon as possible.)

But the most alluring aspect of Eco’s book is the way he imagines the community that results from any honest intellectual endeavor—the conversations you enter into across time and space, across age or hierarchy, in the spirit of free-flowing, democratic conversation. He cautions students against losing themselves down a narcissistic rabbit hole: you are not a “defrauded genius” simply because someone else has happened upon the same set of research questions. “You must overcome any shyness and have a conversation with the librarian,” he writes, “because he can offer you reliable advice that will save you much time. You must consider that the librarian (if not overworked or neurotic) is happy when he can demonstrate two things: the quality of his memory and erudition and the richness of his library, especially if it is small. The more isolated and disregarded the library, the more the librarian is consumed with sorrow for its underestimation.”

Eco captures a basic set of experiences and anxieties familiar to anyone who has written a thesis, from finding a mentor (“How to Avoid Being Exploited By Your Advisor”) to fighting through episodes of self-doubt. Ultimately, it’s the process and struggle that make a thesis a formative experience. When everything else you learned in college is marooned in the past—when you happen upon an old notebook and wonder what you spent all your time doing, since you have no recollection whatsoever of a senior-year postmodernism seminar—it is the thesis that remains, providing the once-mastered scholarly foundation that continues to authorize, decades-later, barroom observations about the late-career works of William Faulker or the Hotelling effect. (Full disclosure: I doubt that anyone on Earth can rival my mastery of John Travolta’s White Man’s Burden, owing to an idyllic Berkeley spring spent studying awful movies about race.)

In his foreword to Eco’s book, the scholar Francesco Erspamer contends that “How to Write a Thesis” continues to resonate with readers because it gets at “the very essence of the humanities.” There are certainly reasons to believe that the current crisis of the humanities owes partly to the poor job they do of explaining and justifying themselves. As critics continue to assail the prohibitive cost and possible uselessness of college—and at a time when anything that takes more than a few minutes to skim is called a “longread”—it’s understandable that devoting a small chunk of one’s frisky twenties to writing a thesis can seem a waste of time, outlandishly quaint, maybe even selfish. And, as higher education continues to bend to the logic of consumption and marketable skills, platitudes about pursuing knowledge for its own sake can seem certifiably bananas. Even from the perspective of the collegiate bureaucracy, the thesis is useful primarily as another mode of assessment, a benchmark of student achievement that’s legible and quantifiable. It’s also a great parting reminder to parents that your senior learned and achieved something.

But “How to Write a Thesis” is ultimately about much more than the leisurely pursuits of college students. Writing and research manuals such as “The Elements of Style,” “The Craft of Research,” and Turabian offer a vision of our best selves. They are exacting and exhaustive, full of protocols and standards that might seem pretentious, even strange. Acknowledging these rules, Eco would argue, allows the average person entry into a veritable universe of argument and discussion. “How to Write a Thesis,” then, isn’t just about fulfilling a degree requirement. It’s also about engaging difference and attempting a project that is seemingly impossible, humbly reckoning with “the knowledge that anyone can teach us something.” It models a kind of self-actualization, a belief in the integrity of one’s own voice.

A thesis represents an investment with an uncertain return, mostly because its life-changing aspects have to do with process. Maybe it’s the last time your most harebrained ideas will be taken seriously. Everyone deserves to feel this way. This is especially true given the stories from many college campuses about the comparatively lower number of women, first-generation students, and students of color who pursue optional thesis work. For these students, part of the challenge involves taking oneself seriously enough to ask for an unfamiliar and potentially path-altering kind of mentorship.

It’s worth thinking through Eco’s evocation of a “just society.” We might even think of the thesis, as Eco envisions it, as a formal version of the open-mindedness, care, rigor, and gusto with which we should greet every new day. It’s about committing oneself to a task that seems big and impossible. In the end, you won’t remember much beyond those final all-nighters, the gauche inside joke that sullies an acknowledgments page that only four human beings will ever read, the awkward photograph with your advisor at graduation. All that remains might be the sensation of handing your thesis to someone in the departmental office and then walking into a possibility-rich, almost-summer afternoon. It will be difficult to forget.

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mary Norris

By Joshua Rothman

By Benjamin Kunkel

By Willing Davidson

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

How to Write a Thesis, by Umberto Eco

This guide gets right to the heart of the virtues that make a scholar, robert eaglestone discovers.

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

These seem to be very bad times for graduate research students in the arts and humanities, the intended audience for this book. The job market is not great; funding is scarce; casualisation, which might appear to serve grad students but actually exploits them, proceeds apace; the smooth, high walls of the ivory tower seem ever more exclusive and imposing; the groves of academe (odd, I’ve always thought, to have groves inside a tower) ever more remote. Even from the pages of Times Higher Education , our little world’s local paper, opinion pieces declare that, to prevent them getting “exalted notions of themselves” (forfend!), researchers in the arts and humanities should realise that they are simply “trainspotters in their field” about whom no one cares (wait: trainspotters in a…field?). Instead of doing research, it’s argued, they should simply teach, concentrating, as Jorge of Burgos demands, in Umberto Eco’s bestselling 1980 novel The Name of the Rose , on “the preservation of knowledge” or at best “a continuous and sublime recapitulation” of what is known.

Into this bleak picture comes the first English translation of Eco’s How to Write a Thesis , continuously in print in Italy since 1977. That was a long time ago in academia, and, at first sight, lots of this book looks just useless, rooted in its historic and specific Italian context. Who uses index cards any more? (I mean, I used to, but I wrote my PhD on a computer with no hard drive, using 5¼-inch diskettes, when the internet was still for swapping equations at Cern or firing nukes at Russia.) Who has typists copy up their thesis? The sections on using libraries and research sources sound like an account of a lost, antediluvian culture.

Just before we throw this book away, or donate it to some dusty museum of intellectual life along with the doctoral theses and career hopes of our graduate students, let’s do what it is that we humanists are trained by our research to do: not just recapitulate what “we all know”, but – you remember – go a little slower, read a bit closer, look deeper, think more. It’s then that we can see the reasons for the publication of this book, in this clear and easily read translation by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina. Indeed, once some of the dust has been gently blown from the pages (and this itself is a useful research exercise), we realise that How to Write a Thesis is full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it, illustrated with lucid examples and – significantly – explanations of why , by one of the great researchers and writers in the post-war humanities.

Most of the advice is gloriously practical: how to organise your primary resources; lists of common academic abbreviations (of course, some are easily fig. ed. out: others are harder; cf., passim , etc); how to and why to narrow down a topic (because “the rigour of a thesis is more important than its scope”); why it’s not only normal but productive to keep revising the contents and structure of your thesis; how to avoid being exploited by your advisers; how to reference; why you should check the sources of other people’s quotations. More, too, in this dense book. Eco explores common traps: for example, the “alibi of photocopies” (and, we can add, scans, PDFs and so on) (“there are many things I do not know because I photocopied a text and then relaxed as if I had read it”). He stresses how “the capacity to identify problems, confront them methodically, and articulate them systematically in expository detail” in a thesis is vital for employment outside universities (“transparency about transferable skills”, ugh, we might say). And while index cards themselves may be antiquated, the idea behind having files for bibliography, quotations, what to read and ideas that strike you is not. Best of all, the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own. Do not photocopy or scan this section (it’s pp. 145-184, by the way).

While lots of the advice is hands-on (“begin new paragraphs often”), some is more metaphysical. Writing a thesis involves learning academic humility, the “knowledge that anyone can teach us something”. Eco illustrates this with a beautiful story of how a chance remark in a century-old book, badly written and full of preconceived ideas, by Vallet, an abbot, gave him a vital insight for his own thesis. And then, demonstrating the complex ways that work and intellectual inspiration are related, he tells of discovering years later, on returning to the book, that while the insight was not there on the page at all, somehow, as a student, he had himself taken it from the book: “is this not also what we ask from a teacher, to provoke us to invent ideas?” Conversely, Eco suggests that in writing, one should have a degree of pride: on “your specific topic, you are humanity’s functionary who speaks in the collective voice. Be humble and prudent before opening your mouth, but once you open it, be dignified and proud” (or, if this is too much, at least “do not whine and be complex-ridden, because it is annoying”). Most of all, undertake a thesis, he says, with gusto, with enjoyment: it is not a “meaningless ritual” but something more.

The “something more”, without Eco ever declaring it, is the true subject of the book: learning, through the concrete practicalities of writing a thesis, the virtues that research teaches us. The philosopher Bernard Williams argued that the “authority of academics” must be rooted in the virtues of accuracy and sincerity: academics “take care, and they do not lie”. It’s true that understanding how these virtues apply in the arts and humanities is more complicated than in some areas of university research, in part because, in our constant dialogue about humanity’s ever-changing self-understanding, terms such as “truth”, “sincerity” and “virtue” are part of the dialogue and not fixed points. But the virtues are there, and one way – one very good way – to learn them is by writing a thesis. So, How to Write a Thesis is really: how to be an academic.

This is part of the answer to those who think that focusing on research makes us bad teachers: at their very deepest roots, both research and teaching in universities rely not only on subject knowledge but on the virtues of sincerity and accuracy, taught through research. But there’s more: the paradox – brought into sharp focus by How to Write a Thesis – that even with a PhD, you never properly qualify. Even eminent professors remain, in a way, students for ever, with more to research, more to explore just over there . And the surprising fact is that the people who remember daily the experience of doing research, who know that despite their degrees, titles and fancy hats, they, too, are really only students: these are the best people to teach other students. Whisper it – it’s not politic to say it aloud – but that’s what makes universities special places. Our graduate students intuit this, so help them scale the tower’s walls (so as to toil in the incongruously situated groves) by giving them this book.

Robert Eaglestone is professor of contemporary literature and thought, Royal Holloway, University of London . In 2014 he won a National Teaching Fellowship Award.

How to Write a Thesis

By Umberto Eco Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina MIT Press, 256pp, £13.95 ISBN 9780262527132 Published 24 April 2015

First published in 1977, linguist and philosopher Umberto Eco’s Come si fa una tesi di laurea: le materie umanistiche is now in its 23rd edition in the original Italian. It has been translated into 17 languages, including Farsi, Russian and Chinese, and now finally into English as How to Write a Thesis .

Eco, who is president of the Scuola Superiore di Studi Umanistici at the University of Bologna , was born in 1932 in Alessandria in Piedmont, northern Italy. He studied medieval philosophy and literature at the University of Turin , where he would later lecture. His first book, Il problema estetico in San Tommaso (1956), drew on his own doctoral thesis.

In addition to the acclaim that has greeted his scholarly work, Eco’s fiction has brought him widespread popular recognition, most notably with The Name of the Rose (1980) and Foucault’s Pendulum (1988). His latest novel, Numero Zero , will be published in English in November.

He observed to the Harvard Crimson that he “started by considering myself a scholar who worked six days a week and wrote novels on Sundays. And I thought at the beginning that there was no relationship between my novels and my academic work. Then, reading critics, [I saw that] they found connections.”

Asked in a recent New York Times interview about his legacy, Eco said: “Every writer, every artist, every musician, scientist is profoundly interested in the survival of his or her work after their death. Otherwise they would be idiots.

“Do you believe that Raphael was not interested in what happened to his paintings after his death? It’s another side of the normal human desire to survive personally in some way…[it] is essential if you work on something creative to have this hope. Otherwise you are only a person doing something to make money, to have women and champagne.”

Eco’s dry wit has supplied countless well-loved quips. A number of them, in a variety of languages, have been obligingly assembled on the author’s own website .

Karen Shook

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Reader's comments (3)

You might also like.

Charity cases: Why UK universities are really going broke

The redundancies and course closures proposed at many struggling UK universities follow a decades-long drift away from the idea of higher education institutions as charities whose non-commercial public benefit needs to be supported by profit-making activity, argues Martin Mills

The UK’s three-year probations are needless and counterproductive

Keeping highly trained people on tenterhooks for so long undermines the conditions necessary for innovation, says a university manager

Research jobs growth ‘going gangbusters’ – but not in universities

Australian study finds good prospects for research degree graduates, so long as they look beyond academia

Featured jobs

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

How to Write a Thesis by Umberto Eco review – offering hope to harried slackers

Who better to help with essay neurosis than a venerable public intellectual and author?

A s a young scholar, Umberto Eco trained himself to complete everyday and academic tasks at speed; he quickened his pace between appointments, devoured pages at a glance, treated each tiny interstice of the working day as a chance to judge, reflect or compose. One imagines even his beard was a timesaving outgrowth of impatient ambition. Such deliberate habits in a writer suggest a sort of performance, and Eco has enjoyed showing interviewers around the three studies where he works: one each devoted to reading, typing and writing by hand. Such is his finicky pleasure in his own process that belated Anglophone readers should not be surprised that Eco once published a guide to researching and writing a dissertation. How to Write a Thesis has been in print in Italy, almost unchanged, since 1977. Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina, it is at once an eminently wise and useful manual, and a museum of dying or obsolete skills. Not to mention ancient office products.

How to Write a Thesis appeared when Eco was already established as semiotician, pop-culture analyst and author of books about the aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas and the medievalism of James Joyce . Three years later The Name of the Rose turned the public intellectual into a purveyor of ingenious if turgid fiction. Eco’s first novel and his student-writing guide have this in common: they imagine a hasty unlearned youth being led around the library by a middle-aged scholar-sleuth who may himself be on the wrong track. Eco sets out to instruct a student on the edge of panic, and he is more than a little sarcastic about how the tyro scholar may have arrived at this state of emergency: “Let us try to imagine the extreme situation of a working Italian student who has attended the university very little during his first three years of study.”

Many readers may recognise themselves – and teachers their students – in the harried slacker to whom How to Write a Thesis offers practical advice. Eco was writing in the context of an old and anomalous academic culture, faced in the 1970s with conflicting bureaucratic demands and potentially crippling (for students, for knowledge) economic circumstances. The laurea was then the terminal degree – how that phrase haunts the young researcher – at Italian universities, and involved a thesis which took the student several months, at worst years, of extra labour. Many candidates had written little or nothing as undergraduates, so balked at extended prose composition, let alone the rigours of a dissertation. Some simply could not afford the time, books or travel required to complete an ambitious piece of research. Others, distracted by the student militancy of the decade, found out too late that the radical’s skills of debate, polemic or protest were not exactly those required for dogged scholarship, or by a state system. To all these students, Eco’s little book offered some hope.

One of the admirable impulses behind How to Write a Thesis is this sense that Eco fully understands the many reasons for academic failure: from student poverty, through institutional obtuseness to the crushing “thesis neurosis” that afflicts the type – mea maxima culpa , as it happens – who “uses his thesis as an alibi to avoid other challenges in his life”. Eco is a generous and genial teacher, but he demands some strict choices at the outset. The student must commit to six months at least of sustained work, must give up the egotism that lights on madly ambitious thesis topics and arrogantly “creative” methods, and must practise instead a form of “academic humility”. Any subject, no matter how modest, may yield real knowledge; any writer (Eco is mostly discussing humanities research), however unfashionable or obscure, could turn out to hold the key. Much of How to Write a Thesis is consequently concerned with lowering expectations and limiting the amount of material the student will have to wrangle: “It is better to build a serious trading card collection from 1960 to the present day than to create a cursory art collection.”

That might sound a less than enthralling invitation to the vaulting Borgesian precincts of research and writing. But Eco is working on the principle, which almost every writer must learn, that the best intellectual fun is to be had getting lost with a map in your pocket. In 1977 that map was made of paper, and the editors of this new English edition have not disguised the complex analogue methods Eco recommends for marshalling notes and bibliographic entries. (This does happen to venerable writing manuals, with awkward results: I’ve seen an incompletely updated edition of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style , from the 1990s, that has the novice writer moving oddly between typewriter and computer.) At the heart of Eco’s process is the humble index card, on which the student is enjoined to record all the details of books and articles read, but also quotations, summaries and even initial forays into writing proper. Multiple stacks of index cards – Eco imagines the student hefting them around between libraries – form the substrate on which thought and composition are built. In what is surely a vastly optimistic aside, Eco remarks: “You will have an organised system to hand to someone who is working on a similar topic.”

Who knows how effective such advice can ever really be. As I write this, I can still put my hand to a pack of large white index cards I bought 20 years ago, in a fit of nearly fatal PhD anxiety, and never once used. Although the texture of the lost world Eco captures is almost moving now – the scribbled cards, the photocopies, the endless retyping of drafts – it is the state of mind he prescribes that matters, not the moraine of vintage technology that supports it. “The pattern of the thing precedes the thing,” Nabokov said about his own Bristol index cards and Blackwing pencils. You could subtract the last two words from the title of Eco’s book, because at its best it’s a primer in the architectural pleasures of any writing that aspires “to build an object that in principle will serve others”. If Eco is a less inspiring guide to the shape and finish of actual sentences – there are huffy passages about scholars who aspire to prose experiment – that is to be expected in a critic whose style is forever outshone by the likes of Barthes and Calvino . But all three are in love with plans and schemes, which are half of writing, and How to Write a Thesis is a schemer’s dream.

- Umberto Eco

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

How To Write a Thesis : A Witty, Irreverent & Highly Practical Guide Now Out in English">Umberto Eco’s How To Write a Thesis : A Witty, Irreverent & Highly Practical Guide Now Out in English

in Books , Education , Writing | March 23rd, 2015 5 Comments

Image by Università Reggio Calabria, released under a C BY-SA 3.0 license.

In general, the how-to book—whether on beekeeping, piano-playing, or wilderness survival—is a dubious object, always running the risk of boring readers into despairing apathy or hopelessly perplexing them with complexity. Instructional books abound, but few succeed in their mission of imparting theoretical wisdom or keen, practical skill. The best few I’ve encountered in my various roles have mostly done the former. In my days as an educator, I found abstract, discursive books like Robert Scholes’ Textual Power or poet and teacher Marie Ponsot’s lyrical Beat Not the Poor Desk infinitely more salutary than more down-to-earth books on the art of teaching. As a sometime writer of fiction, I’ve found Milan Kundera’s idiosyncratic The Art of the Novel —a book that might have been titled The Art of Kundera —a great deal more inspiring than any number of other well-meaning MFA-lite publications. And as a self-taught audio engineer, I’ve found a book called Zen and the Art of Mixing —a classic of the genre, even shorter on technical specifications than its namesake is on motorcycle maintenance—better than any other dense, diagram-filled manual.

How I wish, then, that as a onetime (longtime) grad student, I had had access to the English translation, just published this month, of Umberto Eco’s How to Write a Thesis , a guide to the production of scholarly work worth the name by the highly celebrated Italian novelist and intellectual. Written originally in Italian in 1977, before Eco’s name was well-known for such works of fiction as The Name of the Rose and Foucault’s Pendulum , How to Write Thesis is appropriately described by MIT Press as reading: “like a novel”: “opinionated… frequently irreverent, sometimes polemical, and often hilarious.”

For example, in the second part of his introduction, after a rather dry definition of the academic “thesis,” Eco dissuades a certain type of possible reader from his book, those students “who are forced to write a thesis so that they may graduate quickly and obtain the career advancement that originally motivated their university enrollment.” These students, he writes, some of whom “may be as old as 40” (gasp), “will ask for instructions on how to write a thesis in a month .” To them, he recommends two pieces of advice, in full knowledge that both are clearly “ illegal ”:

(a) Invest a reasonable amount of money in having a thesis written by a second party. (b) Copy a thesis that was written a few years prior for another institution. (It is better not to copy a book currently in print, even if it was written in a foreign language. If the professor is even minimally informed on the topic, he will be aware of the book’s existence.

Eco goes on to say that “even plagiarizing a thesis requires an intelligent research effort,” a caveat, I suppose, for those too thoughtless or lazy even to put the required effort into academic dishonesty.

Instead, he writes for “students who want to do rigorous work” and “want to write a thesis that will provide a certain intellectual satisfaction.” Eco doesn’t allow for the fact that these groups may not be mutually exclusive, but no matter. His style is loose and conversational, and the unseriousness of his dogmatic assertions belies the liberating tenor of his advice. For all of the fun Eco has discussing the whys and wherefores of academic writing, he also dispenses a wealth of practical hows, making his book a rarity among the small pool of readable How-tos. For example, Eco offers us “Four Obvious Rules for Choosing a Thesis Topic,” the very bedrock of a doctoral (or masters) project, on which said project truly stands or falls:

1. The topic should reflect your previous studies and experience. It should be related to your completed courses; your other research; and your political, cultural, or religious experience. 2. The necessary sources should be materially accessible. You should be near enough to the sources for convenient access, and you should have the permission you need to access them. 3. The necessary sources should be manageable. In other words, you should have the ability, experience, and background knowledge needed to understand the sources. 4. You should have some experience with the methodological framework that you will use in the thesis. For example, if your thesis topic requires you to analyze a Bach violin sonata, you should be versed in music theory and analysis.

Having suffered the throes of proposing, then actually writing, an academic thesis, I can say without reservation that, unlike Eco’s encouragement to plagiarism, these four rules are not only helpful, but necessary, and not nearly as obvious as they appear. Eco goes on in the following chapter, “Choosing the Topic,” to present many examples, general and specific, of how this is so.

Much of the remainder of Eco’s book—though written in as lively a style and shot through with witticisms and profundity—is gravely outdated in its minute descriptions of research methods and formatting and style guides. This is pre-internet, and technology has—sadly in many cases—made redundant much of the footwork he discusses. That said, his startling takes on such topics as “Must You Read Books?,” “Academic Humility,” “The Audience,” and “How to Write” again offer indispensable ways of thinking about scholarly work that one generally arrives at only, if at all, at the completion of a long, painful, and mostly bewildering course of writing and research.

FYI: You can download Eco’s book, How to Write a Thesis, as a free audiobook if you want to try out Audible.com’s no-risk, 30-day free trial program. Find details here .

Related Content:

The Books You Think Every Intelligent Person Should Read: Crime and Punishment, Moby-Dick & Beyond (Many Free Online)

“Lol My Thesis” Showcases Painfully Hilarious Attempts to Sum up Years of Academic Work in One Sentence

Steven Pinker Uses Theories from Evolutionary Biology to Explain Why Academic Writing is So Bad

Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School: Apply & Learn the Art of Guerilla Filmmaking & Lock-Picking

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (5) |

Related posts:

Comments (5), 5 comments so far.

Wish I’d had this when I was writing my dissertation.

Wow, it took 38 years… Second-hand paperback copies were available when I wrote my MA dissertation…

One remark: the “thesis” Eco is writing about in this book wasn’t the actual PhD thesis. In Italy in the late seventies you only had four-years all inclusive “Bachelor’s/Master’s/Phd’s” programs, ending with a thesis (“Tesi di laurea”). This presupposed that the final research work (product of about a year of labor) was potentially publishable… and in fact Eco published his thesis on Thomas’ aesthetics. This didn’t necessarily mean less quality, quite the opposite: try to think at the sentence “If the professor is even minimally informed on the topic, he will be aware of the book’s existence.” today!

So, the burning question — is the book available online, in English?

Patently a priori knowledge. That Eco invested time and effort in producing is a statement of his dire thoughts about the future of the human intellect in the digital/ nascent AI age.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Book lists by.

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

How to Write a Thesis

Umberto eco, trans. from the italian by caterina mongiat farina and geoff farina. mit, $19.95 trade paper (256p) isbn 978-0-262-52713-2.

Reviewed on: 01/12/2015

Genre: Nonfiction

Compact Disc - 979-8-200-55816-2

Compact Disc - 978-1-4690-0362-7

MP3 CD - 979-8-200-55817-9

- Apple Books

- Barnes & Noble

More By and About this Author chevron_right

How to write a thesis

By umberto eco , geoff farina , francesco erspamer , caterina mongiat farina , and sean pratt.

- ★ ★ ★ 3.00 ·

- 19 Want to read

- 4 Currently reading

- 1 Have read

Preview Book

My Reading Lists:

Use this Work

Create a new list

My book notes.

My private notes about this edition:

Check nearby libraries

- Library.link

Buy this book

"Eco's approach is anything but dry and academic. He not only offers practical advice but also considers larger questions about the value of the thesis-writing exercise. How to Write a Thesis is unlike any other writing manual. It reads like a novel. It is opinionated. It is frequently irreverent, sometimes polemical, and often hilarious. Eco advises students how to avoid "thesis neurosis" and he answers the important question "Must You Read Books?" He reminds students "You are not Proust" and "Write everything that comes into your head, but only in the first draft." Of course, there was no Internet in 1977, but Eco's index card research system offers important lessons about critical thinking and information curating for students of today who may be burdened by Big Data." -- Publisher's description.

Previews available in: English Spanish Italian

Showing 6 featured editions. View all 20 editions?

Add another edition?

Book Details

Edition notes.

Includes bibliographical references.

Classifications

The physical object, work description.

See work: https://openlibrary.org/works/OL14853066W

Community Reviews (0)

- Created July 18, 2019

- 9 revisions

Wikipedia citation

Copy and paste this code into your Wikipedia page. Need help ?

How to Write a Thesis

By: Umberto Eco

- Narrated by: Sean Pratt

- Length: 8 hrs and 15 mins

- 4.3 out of 5 stars 4.3 (94 ratings)

Failed to add items

Add to cart failed., add to wish list failed., remove from wishlist failed., adding to library failed, follow podcast failed, unfollow podcast failed.

$7.95 a month after 30 days. Cancel anytime.

Buy for $24.06

No default payment method selected.

We are sorry. we are not allowed to sell this product with the selected payment method, listeners also enjoyed....

The Name of the Rose

- By: Umberto Eco, William Weaver - translator

- Narrated by: Sean Barrett, Neville Jason, Nicholas Rowe

- Length: 21 hrs and 5 mins

- Overall 4.5 out of 5 stars 2,580

- Performance 4.5 out of 5 stars 2,308

- Story 4.5 out of 5 stars 2,310

The year is 1327. Franciscans in a wealthy Italian abbey are suspected of heresy, and Brother William of Baskerville arrives to investigate. But his delicate mission is suddenly overshadowed by seven bizarre deaths that take place in seven days and nights of apocalyptic terror. Brother William turns detective, and a uniquely deft one at that. His tools are the logic of Aristotle, the theology of Aquinas, the empirical insights of Roger Bacon-- all sharpened to a glistening edge by his wry humor and ferocious curiosity.

- 5 out of 5 stars

The meaning of the mystery & mystery of meaning

- By Ryan on 02-14-14

By: Umberto Eco , and others

A Novice Guide to How to Write a Thesis

- Quick Tips on How to Finish Your Thesis or Dissertation

By: Sharaf Mutahar Alkibsi

- Narrated by: Allen Wayne Logue

- Length: 3 hrs and 29 mins

- Overall 4 out of 5 stars 28

- Performance 4 out of 5 stars 25

- Story 4 out of 5 stars 25

The book would be most useful to students looking to start and finish their thesis or dissertation. Advisors may recommend this book for their students at the early stage of their research project or if they struggle at any stage. The book addresses the big picture of the research journey, and provides advice on how to manage the entire process. I have seen the best students get stuck. All they needed to triumph was a piece of advice.

great easy read for the novice!

- By DaMuirheads on 05-19-17

- Narrated by: George Guidall

- Length: 18 hrs and 53 mins

- Overall 4.5 out of 5 stars 277

- Performance 4.5 out of 5 stars 243

- Story 4.5 out of 5 stars 243

As Constantinople is being pillaged and burned in April 1204, a young man, Baudolino, manages to save a historian and a high court official from certain death at the hands of crusading warriors. Born a simple peasant, Baudolino has two gifts: his ability to learn languages and to lie. A young man, he is adopted by a foreign commander who sends him to university in Paris. After he allies with a group of fearless and adventurous fellow students, they go in search of a vast kingdom to the East.

- 4 out of 5 stars

For Umberto Eco fans, very good but not great

- By DFK on 07-09-17

Foucault's Pendulum

- Narrated by: Tim Curry

- Length: 6 hrs and 34 mins

- Overall 4 out of 5 stars 700

- Performance 4.5 out of 5 stars 532

- Story 4 out of 5 stars 524

One Colonel Ardenti, who has unnaturally black, brilliantined hair, a carefully groomed mustache, wears maroon socks, and who once served in the Foreign Legion, starts it all. He tells three Milan book editors that he has discovered a coded message about a Templar Plan, centuries old and involving Stonehenge, a plan to tap a mystic source of power far greater than atomic energy.

- 2 out of 5 stars

too much missing

- By Kenneth on 01-29-07

How to Write a Lot (2nd Edition)

- A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing

By: Paul J. Silvia PhD

- Narrated by: Chris Sorensen

- Length: 3 hrs and 42 mins

- Overall 4.5 out of 5 stars 76

- Performance 4.5 out of 5 stars 56

- Story 4.5 out of 5 stars 56

All academics need to write, but many struggle to finish their dissertations, articles, books, or grant proposals. Writing is hard work and can be difficult to wedge into a frenetic academic schedule. How can we write it all while still having a life? In this second edition of his popular guidebook, Paul Silvia offers fresh advice to help you overcome barriers to writing and use your time more productively.

Grad students read this book

- By Jen on 03-16-22

Six Walks in the Fictional Woods

- Narrated by: Nick Sullivan

- Length: 5 hrs and 4 mins

- Overall 4.5 out of 5 stars 86

- Performance 4 out of 5 stars 79

- Story 4.5 out of 5 stars 78

In this exhilarating book, we accompany Umberto Eco as he explores the intricacies of fictional form and method. Using examples ranging from fairy tales and Flaubert, Poe and Mickey Spillane, Eco draws us in by means of a novelist's techniques, making us his collaborators in the creation of his text and in the investigation of some of fiction's most basic mechanisms.

big ideas presented simply

- By Ashton on 01-31-14

Society of the Spectacle

By: Guy Debord

- Narrated by: Bruce T Harvey

- Length: 3 hrs and 43 mins

- Overall 4.5 out of 5 stars 161

- Performance 4.5 out of 5 stars 138

- Story 4.5 out of 5 stars 135

This is the "Das Kapital" of the 20th century - an essential text, and the main theoretical work of the Situationists. Few works of political and cultural theory have been as enduringly provocative. From its publication amid the social upheavals of the 1960s up to the present, the volatile theses of this book have decisively transformed debates on the shape of modernity, capitalism, and everyday life in the 21st century. This is the original translation by Fredy Perlman, kept in print continuously for the last 50 years, keeping the flame of personal and collective autonomy alive.

- By Rachel on 08-28-19

How to Take Smart Notes

- One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking - for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers

By: Sonke Ahrens

- Narrated by: Nigel Fyfe

- Length: 5 hrs and 53 mins

- Overall 4.5 out of 5 stars 280

- Performance 4.5 out of 5 stars 221

- Story 4.5 out of 5 stars 220

The key to good and efficient writing lies in the intelligent organization of ideas and notes. This book helps students, academics, and nonfiction writers to get more done, write intelligent texts, and learn for the long run. It teaches you how to take smart notes and ensure they bring you and your projects forward.

A mindblowing book everyone should read

- By Kenneth on 08-29-22

On the Shoulders of Giants

- By: Umberto Eco, Alastair McEwen

- Narrated by: Pete Cross

- Length: 9 hrs and 28 mins

- Overall 4.5 out of 5 stars 20

- Performance 4.5 out of 5 stars 18

- Story 4.5 out of 5 stars 19