Definition of Concession

Concession is a literary device used in argumentative writing, where one acknowledges a point made by one’s opponent. It allows for different opinions and approaches toward an issue, indicating an understanding of what causes the actual debate or controversy. It demonstrates that the writer is a mature thinker, and has considered the issue from all angles.

Concession writing style also shows that the writer is a logical and fair-minded person, able to realize that every argument has several sides to consider before it is presented. This type of writing can be considered strong as it finds common ground between the writer and his opponent.

Concession Examples

Example #1:.

“Dad, I know taking a trip to another country with my friends may be expensive and unsafe, but I have studied so hard the past year and I think I deserve a vacation. You already know how responsible I have been all my life; I don’t think there will be any problem.”

The above statement is an example of concession writing. It demonstrates the negative aspects of traveling as a young group of boys, but argues against this with the fact that this particular boy has always been a responsible person and is not likely to get into trouble.

Example #2:

“I agree that many students act and lie about being sick, so that they can avoid school for whatever reason. However, most students who do not come to school are actually sick. Being sick, they should be focusing on getting better, not worrying about school and grades just because some students take advantage of the absentee policy.”

This statement also shows the concession form of writing where the writer agrees that some students do lie about being sick, and that the writer is able to understand this issue. At the same time, the writer argues as to why students who are actually sick suffer because of those irresponsible students.

Example #3:

“An individual does have his own right to freedom, but medical evidence proves that second-hand smoke is harmful. Nobody has the right to harm the health of another, and smoking does just that.”

Using concession, the writer has noted that everybody has freedom rights, but argues about the fact that nobody has the right to harm another person’s health, no matter what the case is.

Example #4:

“It is true that issues may sometimes become polarized and debated heatedly. Certainly, there is a need for matters of public concern to be discussed rationally. But that does not mean that such concerns should not be expressed and investigated. After all, improper interference with academic freedom was found to have taken place. And the allegations raised by doctors are ones which deserve further inquiry.”

The above statement demonstrates the concession writing technique, where the writer agrees that debating on issues can turn into a heated argument, but that does not mean the issues should stop being discussed and investigated. Using concession, the writer has considered the different viewpoints of the issue, and then stated his argument.

Example #5: Politics and the English Language (By George Orwell)

“I said earlier that the decadence of our language is probably curable. Those who deny this would argue, if they produced an argument at all, that language merely reflects existing social conditions, and that we cannot influence its development by any direct tinkering with words or constructions. So far as the general tone or spirit of language goes, this may be true, but it is not true in detail.”

This is another example of concession writing showing that the writer is a fair person who has thought about the issue before giving his opinion. The writer agrees with the fact that we cannot do anything to develop the language. However it is not true if we go into details, Orwell says, because writers influence it too.

Function of Concession

Concession writing acknowledges that there are many different views to a story . This type of writing allows for different opinions that can or could be made toward an issue. It also shows that all points, positive as well as negative, have been considered before an argument is put forward. Presenting the other side and then arguing against it with valid points can make it a very strong piece of writing. Acknowledging the other side demonstrates respect for the other opinion. The concession writing technique is also known used as a method of persuasion and reasoning.

Post navigation

What is Concession? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Concession definition.

A concession (kuhn-SEH-shun) in literature is a point yielded to an opposing perspective during an argument. It allows a writer to acknowledge that information presented by an opponent has some amount of validity and should be considered.

Concessions show that a writer doesn’t have tunnel vision when it comes to their subject; instead, they possess a well-rounded, mature perspective that considers other viewpoints. At the same time, a concession doesn’t mean the opponent’s entire argument is correct. It only denotes that one point is legitimate, while the rest of the argument remains faulty or weak.

The word concession comes from the Latin concedere , meaning “to give way.”

Where Concessions Are Used

Concessions are common features of argumentative writing. Essays, academic papers, and other nonfiction writing employ concessions so the reader has a better idea of the dissenting view and the author’s willingness to consider alternative positions. The author will typically grant a concession and immediately qualify it with a but or yet .

Take this excerpt from a 1901 essay by Mark Twain, in which he writes about the government’s decision to fly the American flag during the Philippine-American War:

I was not properly reared, and had the illusion that a flag was a thing which must be sacredly guarded against shameful uses and unclean contacts, lest it suffer pollution; and so when it was sent out to the Philippines to float over a wanton war and a robbing expedition I supposed it was polluted, and in an ignorant moment I said so. But I stand corrected. I concede and acknowledge that it was only the government that sent it on such an errand that was polluted. Let us compromise on that. I am glad to have it that way. For our flag could not well stand pollution, never having been used to it, but it is different with the administration.

Using but in the final sentence lets Twain concede that those who disagree with him are correct that the flag itself is not polluted or even intrinsically pollutable—though the presidential administration at the time is both. Thanks to his concession, Twain can admit to his prior error while making a larger statement about political corruption—and exercise his trademark wit.

Concessions appear in fiction, poetry , and plays as well. They make for compelling storytelling devices that often reveal truths about the character or speaker or the work itself. Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie opens with Tom making a concession:

Yes, I have tricks in my pocket, I have things up my sleeve. But I am the opposite of a stage magician. He gives you illusion that has the appearance of truth. I give you truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.

Tom freely admits the will contain illusion while confessing—with the word but —that he is no magician and no dishonesty will occur. The illusion, he says, will only amplify the truth it conceals.

Concessions in Politics and Rhetoric

Concessions are utilized in speeches and debates to inform or persuade listeners of certain facts or ideas. For instance, in his famous Gettysburg Address , Abraham Lincoln said:

The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here.

Lincoln conceded that the world may forget his words, but it will always remember the sacrifices of the soldiers who gave up their lives.

A concession speech is a slightly different type of concession. It is a public speech in which a losing candidate yields to a winning candidate after the results of a vote are determined or, at least, foreseeable given the current vote count. This is from Hillary Clinton’s 2016 concession speech:

I know how disappointed you feel because I feel it too, and so do tens of millions of Americans who invested their hopes and dreams in this effort. This is painful and it will be for a long time, but I want you to remember this. Our campaign was never about one person or even one election, it was about the country we love and about building an America that’s hopeful, inclusive and big-hearted.

Clinton acknowledges that her loss is a personally painful event for many people but that her campaign always had a larger focus on a more united and compassionate America. By doing this, she reminds listeners to continue the hard work of progress and not get bogged down in personal defeat.

These speeches, however, may not include individual concessions at all. The overall speech itself is the concession: the forfeiting of the race and the recognition of the winner.

Concessions vs Rebuttals

Concessions are not rebuttals . Concessions affirm and agree with someone else’s argument, while rebuttals directly challenge someone else’s argument. Put another way, concessions are allowances, while rebuttals are counterarguments. A concession admits that an opposing side has a valid point, and a rebuttal sets out to prove that the opposing side’s point is not valid.

The Function of Concessions

A concession’s primary function is to show common ground between two opposing ideas. In a debate or a written work on a particularly contentious topic, a concession demonstrates a fair approach to the subject—one that isn’t so fanatical that it’s illogical or absurd.

There is also a tactical component involved in concessions. The writer or speaker’s use of concessions paints them as a level-headed, reasonable person who can hear different sides of an issue. This will often make the audience take them more seriously and be more open to what they have to say.

Further Resources on Concessions

The Odegaard Writing & Research Center at the University of Washington delves into concessions and counterarguments in academic writing .

Business Insider has a list of the 10 most memorable concession speeches in United States history .

Dr. Matt Kuefler offers insights into writing concession paragraphs and where you should place them within an essay.

Related Terms

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, concession definition.

A concession is something yielded to an opponent during an argument, such as a point or a fact. Concessions often occur during formal arguments and counterarguments, such as in debates or academic writing. A writer or debater may agree with one aspect of his or her opponent’s ideas and yet disagree with the rest. The writer will allow this one aspect to be true, while proving how the rest is wrong. Conceding certain points can have certain tactical benefits, such as showing how some aspects of the opponent’s arguments are fallacious.

The word concession comes from the Latin word concessionem , which has the same definition of concession, i.e., “allowing or conceding.”

Common Examples of Concession

We can find examples of concessions in debates easily. Usually the person making an argument will state a concession, then follow that with “but” to show how an opponent may be making a misguided argument. Other concessions may start with the phrase “it is true that…” or “certainly.” Here are some concession examples in bold:

- Inequality of wealth is not a new concept. The gap between the super-rich tycoons of today and the poorest employee is not as great as a century ago, given the benefits the government provides. But that does not make it acceptable.

- It is true that issues may sometimes become polarized and debated heatedly. Certainly, there is a need for matters of public concern to be discussed rationally. But that does not mean that such concerns should not be expressed and investigated.

- It is too early to say whether these reforms will prove successful. But the fruits of the policies can perhaps be seen in the fact that the fall in this year’s exam pass rate is negligible compared with last year.

- Piracy and cost-free use of copyright materials deliver short-term gains to users. But if we fail to safeguard the rightful interests of authors, singers and film-makers, all will suffer as they become less resourceful in exploiting their creativity.

We can also find examples of concessions in political debates, such as in Governor John Kasich’s remarks at a 2015 GOP debate:

Our unemployment is half of what it was. Our fracking industry, energy industry may have contributed 20,000 , but if Mr. Trump understood that the real jobs come in the downstream, not in the upstream, but in the downstream. And that’s where we’re going to get our jobs.

Significance of Concession in Literature

Concession examples are somewhat more difficult to find in literature than in other forms of writing, such as academic writing or journalism. This is because authors of literary works don’t usually make arguments that are as explicit as in these other forms of writing. However, some authors will create characters who make concessions to each other in conversation or arguments. Authors also may choose to write concessions to the audience as if guessing what the audience is thinking about a certain situation and writing in response to those assumptions. These are often the more interesting concession examples, as they set up a perceived dialogue between author and reader that, although it is actually one-way, seems to include and challenge the reader.

Examples of Concession in Literature

PORTIA: The quality of mercy is not strain’d, It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven Upon the place beneath: it is twice blest; It blesseth him that gives and him that takes: ‘Tis mightiest in the mightiest: it becomes The throned monarch better than his crown; His sceptre shows the force of temporal power, The attribute to awe and majesty, Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings; But mercy is above this sceptred sway; It is enthroned in the hearts of kings, It is an attribute to God himself; And earthly power doth then show likest God’s When mercy seasons justice.

( The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare)

In this famous courtroom scene from William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice , the character of Portia has dressed up as a lawyer and gives a well-known speech about mercy. As part of this monologue, Portia makes the concession that a monarch’s sceptre “shows the force of temporal power,” and that is leads to “dread and fear of kings.” She clearly understands where a king’s power comes from. Yet she believes—and argues—that mercy is an even more impressive thing for a leader to wield. This is because leaders don’t necessarily need to show mercy, and in so doing they show the power of their character. Portia strengthens her argument for mercy by acknowledging that which is usually attributed as the mightiest aspect of a ruler.

She has committed no crime, she has merely broken a rigid and time-honored code of our society, a code so severe that whoever breaks it is hounded from our midst as unfit to live with. She is the victim of cruel poverty and ignorance, but I cannot pity her: she is white.

( To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee)

The above excerpt is another courtroom scene, this time from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird . Atticus Finch is arguing the case for his defendant Tom Robinson. He tries to turn the accusation back against Mayella Ewell, the girl who originally accused Tom Robinson of a crime. In this closing speech, Atticus concedes the point that Mayella has not committed a crime in falsely accusing Tom. Atticus also makes the concession that Mayella herself is a victim, though not of the crime on trial; she is a victim of poverty. Yet Atticus affirms that these concessions aren’t enough either to sympathize with what she has done or even what she has undergone. The fact that she is white automatically gives her privileges and thus makes her accusation against an innocent black man all the more inexcusable.

TOM: Yes, I have tricks in my pocket, I have things up my sleeve. But I am the opposite of a stage magician. He gives you illusion that has the appearance of truth. I give you truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.

( The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams)

Tennessee Williams’s play The Glass Menagerie contains an interesting example of concession right in the very opening lines. The main character and narrator of the play, Tom, addresses the audience directly in his first few lines. He acknowledges that the guise of a play might make everything seem more fictional, and makes the concession that he has “tricks in [his] pocket” and “things up [his] sleeve.” Yet he avers that behind all the tricks, there is much truth in this play. This is an example of a concession directed at the assumptions of the audience that Tom and Tennessee Williams are working against.

Test Your Knowledge of Concession

1. Which of the following statements is the best concession definition? A. A rebuttal against something the author disagrees with. B. An allowance of a common point with an opponent. C. A demonstration of the fallacy in an opponent’s argument. [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #1″] Answer: B is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

2. Why might an author choose to use an example of a concession? A. To address what the readers might be thinking and answer this with the author’s own ideas. B. To convince the reader that the author is the only one with the right point of view. C. To convince the reader that he or she is completely wrong. [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #2″] Answer: A is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

3. Which of the following statements is not an example of concession from a debate between President Barack Obama and Governor Mitt Romney in 2012? A.

OBAMA: And to the [your credit, Romney], you supported us going into Libya and the coalition that we organized. But when it came time to making sure that Gadhafi did not stay in power, that he was captured, Governor, your suggestion was that this was mission creep, that this was mission muddle.

ROMNEY: I congratulate [Obama] on — on taking out Osama bin Laden and going after the leadership in al-Qaeda. But we can’t kill our way out of this mess.

ROMNEY: With the Arab Spring, came a great deal of hope that there would be a change towards more moderation, and opportunity for greater participation on the part of women in public life, and in economic life in the Middle East. But instead, we’ve seen in nation after nation, a number of disturbing events.

[spoiler title=”Answer to Question #3″] Answer: C is the correct answer. Though Romney uses “but,” which could often signal that someone has just made a concession, he is pointing out the failures of policy rather than agreeing with anything that was done.[/spoiler]

Please log in to save materials. Log in

- Concessions

- Counterarguments

- ESL Writing

The Argumentative Essay: The Language of Concession and Counterargument

Explanations and exercises about the use of counterarguments and concessions in argumentative essays.

The Argumentative Essay: The Language of Concession and Counterargument

We have already analyzed the structure of an argumentative essays (also known as a persuasive essay), and have read samples of this kind of essay. In this session we will review the purpose and structure of an argumentative essay, and will focus on practicing the grammar of sentences that present our argument while acknowledging that there is an opposing view point. In other words, we will focus on the grammar of concession and counterargument.

Purpose and structure of an argumentative essay

Take a few minutes to refresh your knowledge about the purpose and structure of argumentative / persuasive essays.

The Purpose of Persuasive Writing

The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince, motivate, or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion. The act of trying to persuade automatically implies more than one opinion on the subject can be argued.

The idea of an argument often conjures up images of two people yelling and screaming in anger. In writing, however, an argument is very different. An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue in writing is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way. Written arguments often fail when they employ ranting rather than reasoning.

Most of us feel inclined to try to win the arguments we engage in. On some level, we all want to be right, and we want others to see the error of their ways. More times than not, however, arguments in which both sides try to win end up producing losers all around. The more productive approach is to persuade your audience to consider your opinion as a valid one, not simply the right one.

The Structure of a Persuasive Essay

The following five features make up the structure of a persuasive essay:

- Introduction and thesis

- Opposing and qualifying ideas

- Strong evidence in support of claim

- Style and tone of language

- A compelling conclusion

Creating an Introduction and a thesis

The persuasive essay begins with an engaging introduction that presents the general topic. The thesis typically appears somewhere in the introduction and states the writer’s point of view.

Avoid forming a thesis based on a negative claim. For example, “The hourly minimum wage is not high enough for the average worker to live on.” This is probably a true statement, but persuasive arguments should make a positive case. That is, the thesis statement should focus on how the hourly minimum wage is low or insufficient.

Acknowledging Opposing Ideas and Limits to Your Argument

Because an argument implies differing points of view on the subject, you must be sure to acknowledge those opposing ideas. Avoiding ideas that conflict with your own gives the reader the impression that you may be uncertain, fearful, or unaware of opposing ideas. Thus it is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

Try to address opposing arguments earlier rather than later in your essay. Rhetorically speaking, ordering your positive arguments last allows you to better address ideas that conflict with your own, so you can spend the rest of the essay countering those arguments. This way, you leave your reader thinking about your argument rather than someone else’s. You have the last word.

Acknowledging points of view different from your own also has the effect of fostering more credibility between you and the audience. They know from the outset that you are aware of opposing ideas and that you are not afraid to give them space.

It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish. In effect, you are conceding early on that your argument is not the ultimate authority on a given topic. Such humility can go a long way toward earning credibility and trust with an audience. Audience members will know from the beginning that you are a reasonable writer, and audience members will trust your argument as a result. For example, in the following concessionary statement, the writer advocates for stricter gun control laws, but she admits it will not solve all of our problems with crime:

Although tougher gun control laws are a powerful first step in decreasing violence in our streets, such legislation alone cannot end these problems since guns are not the only problem we face.

Such a concession will be welcome by those who might disagree with this writer’s argument in the first place. To effectively persuade their readers, writers need to be modest in their goals and humble in their approach to get readers to listen to the ideas.

Text above adapted from: Writing for Success – Open Textbook (umn.edu) Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Argument, Concession/Acknowledgment and Refutation

We have already seen that as a writer of an argumentative essay, you do not just want to present your arguments for or against a certain issue. You need to convince or persuade your readers that your opinion is the valid one. You convince readers by presenting your points of view, by presenting points of view that oppose yours, and by showing why the points of view different from yours are not as valid as yours. These three elements of an argumentative essay are known as argument (your point of view), concession/acknowledgement/counterargument (admission that there is an opposing point of view to yours) and refutation (showing why the counterargument is not valid). Acknowledging points of view different from yours and refuting them makes your own argument stronger. It shows that you have thought about all the sides of the issue instead of thinking only about your own views.

Identifying argument, counterargument, concession and refutation

We will now look at sentences from paragraphs which are part of an argumentative essay and identify these parts. Read the four sentences in each group and decide if each sentence is the argument, the counterargument, the acknowledgement / concession or the refutation. Circle your choice.

Schools need to replace paper books with e-books.

argument counterargument acknowledgement refutation

Others believe students will get bad eyesight if they read computer screens instead of paper books.

There is some truth to this statement.

However, e-books are much cheaper than paper books.

The best way to learn a foreign language is to visit a foreign country.

Some think watching movies in the foreign language is the best way to learn a language.

Even though people will learn some of the foreign language this way,

it cannot be better than actually living in the country and speaking with the people every day.

Exercise above adapted from: More Practice Recognizing Counterarguments, Acknowledgements, and Refutations. Clyde Hindman. Canvas Commons. Public domain.

More Practice Recognizing Counterarguments, Acknowledgements, and Refutations | Canvas Commons (instructure.com)

Sentence structure: Argument and Concession

Read the following sentences about the issue of cell phone use in college classrooms. Notice the connectors used between the independent and the dependent clauses.

Although cell phones are convenient, they isolate people.

dependent clause independent clause

Cell phones isolate people, even though they are convenient.

independent clause dependent clause

In the sentences above, the argument is “cell phones isolate people”. The counterargument is “cell phones are convenient” and the acknowledgment/concession is expressed by the use of although / even though to make the concession of the opposing argument.

In addition, and most importantly, notice the following:

Which clause contains the writer’s argument? Which clause contains the concession?

The writer’s position is contained in the independent clause and the concession is contained in the dependent clause. This helps the writer to highlight their argument by putting it in the clause that stands on its own and leaving the dependent clause for the concession.

Notice that it doesn’t matter if the independent clause is at the beginning or at the end of the sentence. In both cases, the argument is “cell phones isolate people.”

Notice the difference between these two sentences:

Cell phones are convenient, even though they isolate people.

independent clause dependent clause

Cell phones isolate people, even though they are convenient.

independent clause dependent clause

This pair of sentences shows how the structure of the sentence reflects the point of view of the writer. The argument in the first sentence is that cell phones are convenient. The writer feels this is the important aspect, and thus places it in the independent clause. In the dependent clause, the writer concedes that cell phones isolate people. In contrast, in the second sentence the argument is that cell phones isolate people. The writer feels this is the important aspect and therefore puts this idea in the independent clause. The writer of this sentence concedes that cell phones are convenient, and this concession appears in the dependent clause.

Read the following pairs of sentences and say which sentence in the pair has a positive attitude towards technology in our lives.

A

- Although technology has brought unexpected problems to society, it has become an instrument of progress.

- Technology has brought unexpected problems to society, even though it has become an instrument of progress.

B

- Technology is an instrument of social change, even though there are affordability issues.

- There are affordability issues with technology, even though it is it is an instrument of social change.

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Maria Antonini de Pino – Evergreen Valley College, San Jose, California, USA

LIST OF SOURCES (in order of appearance)

- Text adapted from: Writing for Success – Open Textbook (umn.edu)

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

- Exercise adapted from: More Practice Recognizing Counterarguments, Acknowledgements, and Refutations. Clyde Hindman. Canvas Commons. Public domain.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.8: Writing Concession and Counterargument

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 123878

- Gabriel Winer & Elizabeth Wadell

- Berkeley City College & Laney College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Reading about multiple perspectives

When we read an article or a book, we might imagine we are listening to the voice of the author: one voice (or maybe two or a few voices if there are multiple authors). That one voice is always speaking from a particular point of view, from within a particular culture, and from inside a time period. The author is also not speaking alone, to an empty room. As we read, we can also imagine we are listening to that speaker take their turn in a huge and timeless discussion with thousands of participants, in which the speakers build on and evaluate each others' ideas and argue with each other. Each new study, article, or book adds facts, ideas, and layers of meaning to the discussion. This exchange of ideas, with each new contribution referencing past texts, has been called "the Great Conversation."

Traditionally, many people talk about this "Great Conversation" as something that happens in the Liberal Arts disciplines of Western (European and American) universities: subjects like philosophy, literature, history, the social sciences, and the arts. Scholars discuss competing explanations for a historical event, or the meaning of a line in a poem, or whether a government policy is fair. But great conversations about truth, meaning, and justice also happen around the world and outside of formal academic discourse. They take place on Twitter and TikTok, in movies, in popular magazines, and in street protests, such as the one in Figure 5.8.1. Many texts you read in college classes are taking their turn in this imaginary discussion: they argue for their position, and explain and respond to other perspectives on the topic.

Let's look at an example:

Noticing multiple perspectives

Notice this!

As you read this article, ask yourself

- What is the writers' thesis?

- What other positions do they explain and then fight back against?

- Where are the places where the writers shift perspectives?

- Which connecting words signal the change?

Reading from an online magazine: ‘ Plastic-free ’ fashion is not as clean or green as it seems

We have all become more aware of the environmental impact of our clothing choices. The fashion industry has seen a rise in “green”, “eco” and “sustainable” clothing. This includes an increase in the use of natural fibres, such as wool, hemp, and cotton, as synthetic fabrics, like polyester, acrylic and nylon, have been vilified by some.

However, the push to go “natural” obscures a more complex picture.

Natural fibres in fashion garments are products of multiple transformation processes, most of which are reliant on intensive manufacturing as well as advanced chemical manipulation. While they are presumed to biodegrade, the extent to which they do has been contested by a handful of studies. Natural fibres can be preserved over centuries and even millennia in certain environments. Where fibres are found to degrade they may release chemicals, for example from dyes, into the environment.

When they have been found in environmental samples, natural textile fibres are often present in comparable concentrations than their plastic alternatives. Yet, very little is known of their environmental impact. Therefore, until they do biodegrade, natural fibres will present the same physical threat as plastic fibres. And, unlike plastic fibres, the interactions between natural fibres and common chemical pollutants and pathogens are not fully understood.

Fashion’s environmental footprint

It is within this scientific context that fashion’s marketing of alternative fibre use is problematic. However well-intentioned, moves to find alternatives to plastic fibres pose real risks of exacerbating the unknown environmental impacts of non-plastic particles.

To assert that all these problems can be resolved by buying “natural” simplifies the environmental crisis we face. To promote different fibre use without fully understanding its environmental ramifications suggests a disingenuous engagement with environmental action. It incites “superficial green” purchasing that exploits a culture of plastic anxiety. Their message is clear: buy differently, buy “better”, but don’t stop buying.

Yet the “better” and “alternative” fashion products are not without complex social and environmental injustices. Cotton, for example, is widely grown in countries with little legislation protecting the environment and human health.

The drying up of the Aral Sea in central Asia, formally the fourth largest lake in the world, is associated with the irrigation of cotton fields that dry up the rivers that feed it. This has decimated biodiversity and devastated the region’s fishing industry. The processing of natural fibres into garments is also a major source of chemical pollution, where factory wastewaters are discharged into freshwater systems, often with little or no treatment.

Organic cotton and Woolmark wool are perhaps the most well-known natural fabrics being used. Their certified fibres represent a welcomed material change, introducing to the marketplace new fibres that have codified, improved production standards. However, they still contribute fibrous particles into the environment over their lifetime.

More generally, fashion’s systemic low pay, deadly working conditions, and extreme environmental degradation demonstrate that too often our affordable fashion purchases come at a higher price to somebody and somewhere.

Slow down fast fashion

It is clear then that a radical change to our purchasing habits is required to address fashion’s environmental crisis. A crisis that is not defined by plastic pollution alone.

We must reassess and change our attitudes towards our clothing and reform the whole lifecycle of our garments. This means making differently, buying less and buying second hand. It also means owning for longer, repurposing, remaking and mending.

Fashion’s role in the plastic pollution problem has contributed to emotive headlines, in which purchasing plastic-fibred clothing has become highly moralised. In buying plastic-fibred garments, consumers are framed complicit in poisoning the oceans and food supply. These limited discourses shift accountability onto the consumer to “buy natural”. However, they do little to equally challenge the environmental and social ills of these natural fibres and the retailers’ responsibilities to them.

Thomas Stanton , PhD researcher in the Geography and Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, University of Nottingham and Kieran Phelan , PhD Researcher in economic geography, University of Nottingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

When you write a paper, you are contributing to this "Great Conversation," and you also have to make these same moves. In an argumentative paper, you argue for your own perspective and support your main idea with evidence from other writers who agree with you. However, another important part of your job is to explain other points of view on the topic and respond to them with counterargument and/or concession.

Writing about multiple perspectives

Which perspectives should i include.

Sometimes, if you are writing about a controversial topic with clear opposite sides, it will be easy to identify different perspectives. It's like a debate. Here's an example:

- Thesis: The government should strengthen regulations on water pollution from factories.

- Opposite perspective: Opponents of this plan argue that regulations are not an effective way to reduce pollution.

But "multiple perspectives" doesn't always mean "opposite perspectives." The big questions we think deeply about often lead to more complicated discussions. If you have a more nuanced thesis, it might be harder to think of what the other perspectives are. Here's an example:

- Thesis: Although labor conditions in sweatshops are clearly human rights violations that demand international action, boycotts are actually not the most effective strategy to improve the situation.

- Exploring another perspective: It's true that labor conditions are terrible; workers, sometimes children, work long hours in dangerous factories for low pay.

- Exploring another perspective: Admittedly, many human rights advocates have called for boycotts.

- Exploring another perspective: Granted, boycotts have sometimes been an effective tool for reducing worker exploitation in other industries.

As you research and draft your paper, ask yourself—and your sources—these questions:

- Who? Are they credible sources?

- Why? Is there anything valid about their position? Is it based on values that you (and probably your reader) reject?

- What evidence do they use? Is it solid? Does it actually support their position?

- Is their position logical? Did they use any logical fallacies?

- Is there any factual evidence that seems to contradict my idea?

- What is a problem or concern with my idea? What are some drawbacks?

- What are the limits to my idea?

- What is an exception to my idea?

- What are some possible bad consequences that could result from my idea or plan?

- Why will my idea or plan be hard to do?

- If my idea or plan is so great, why isn't everyone already doing it?

How do multiple perspectives make an argument stronger?

Wait—why would you want to talk about the positions of people who think you're wrong? Wouldn't that weaken your argument?

Actually, no. Carefully explaining the other sides of the topic builds both ethos and logos. Imagine your reader reading your paper, taking in your reasons for why your thesis is true, and saying to themselves, "But what about this problem?" or "I heard that was a bad idea because..." You are communicating to your reader: "See? In case you don't believe me, I already thought about the other sides. Here's what my opponents say, and here's why I'm still right!"

Where do multiple perspectives go in a paper?

In journalistic articles like "‘ Plastic-free ’ Fashion is Not as Clean or Green as it Seems," writers often jump back and forth between perspectives throughout the text. A customary U.S. college argumentative essay typically includes one or more separate body paragraphs dedicated to explaining and responding to perspectives besides your own. Depending on the logic of your ideas, the order of your body paragraphs might follow one of these patterns:

- other perspectives come first, before your regular body paragraphs, to take on readers' possible doubts and objections and get them out of the way before explaining more about your reasons.

- other perspectives come last, after you have made your main case and before your conclusion.

- other perspectives go before or after the particular regular body paragraph they relate to.

Your introduction should also touch on the existence of these other perspectives, and your thesis statement may also directly address them, but you do not need to list every specific perspective in the introduction.

What goes in this special kind of body paragraph?

You start these paragraphs by stating another perspective. Then you explain that idea with specific detail (and often text evidence). Then you respond to that idea in a way that strengthens your overall argument. You may respond to the other positions with one of these two strategies, or a combination of both:

- counterargument : the other position is wrong (this is also called refutation)

- concession : the other position is a little bit true, but overall I'm still right

The key to keeping it all clear is to use connecting words to show which side you are focusing on and when you are changing sides.

Table 5.8.1 provides ideas and possible language to write a paragraph naming, explaining, and responding to other perspectives:

The models in Figure 5.8.2 are expressing two perspectives with their T-shirt slogans.

Concession/counterargument in action

Let's look at an example of a concession/counterargument paragraph in a student essay:

Here is a concession/counterargument paragraph from the student essay. The overall thesis of the whole essay is this:

Although some defend the fast fashion industry’s aesthetic and economic contributions, it has devastating impacts on labor rights and the environment, and needs serious regulations by all nations to stop the damage.

Read the paragraph and look for the following elements:

- What other position do they explain and then fight back against?

- Where are the places where the writer shifts perspectives?

Which parts are counterarguments, and which are concessions?

Despite the clear injustices of garment production, some argue that the fashion industry provides work to people with few better choices in developing countries. According to reporter Stephanie Vatz, companies began outsourcing clothing manufacturing jobs in the 1970s, and by 2013, only two percent of clothing was made in the U.S. The same lack of labor protections that allows terrible working conditions in developing countries also guarantees low labor costs that motivate U.S. companies to relocate their factory sources. Benjamin Powell, the director of the Free Market Institute, justifies sweatshop labor, insisting that this model is "part of the process that raises living standards and leads to better working conditions and development over time (qtd. in Ozdamar-Ertekin 3). This argument is compelling from a distance, but even if it may be true to some degree when we look at the history of economic development, it disregards the humanity of the garment workers. These people continue to work long hours in brutal conditions, generating huge profits for the factory and retail owners. Saying that their lives could be even worse without this exploitation is actually just an excuse for greed.

For suggested answers, see 5.12: Analyzing Arguments Answer Key

Licenses and attributions

Authored by Gabriel Winer, Berkeley City College. License: CC BY NC.

Student essay paragraph from "Deadly Fashion" authored by Maroua Abdelghani and Ruri Tamimoto. License: CC BY NC

CC Licensed Content: Previously Published

"‘ Plastic-free ’ Fashion is Not as Clean or Green as it Seems" is republished from The Conversation , licensed under CC-BY-ND .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Argument, Counterargument, & Refutation

In academic writing, we often use an Argument essay structure. Argument essays have these familiar components, just like other types of essays:

- Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

But Argument essays also contain these particular elements:

- Debatable thesis statement in the Introduction

- Argument – paragraphs which show support for the author’s thesis (for example: reasons, evidence, data, statistics)

- Counterargument – at least one paragraph which explains the opposite point of view

- Concession – a sentence or two acknowledging that there could be some truth to the Counterargument

- Refutation (also called Rebuttal) – sentences which explain why the Counterargument is not as strong as the original Argument

Consult Introductions & Titles for more on writing debatable thesis statements and Paragraphs ~ Developing Support for more about developing your Argument.

Imagine that you are writing about vaping. After reading several articles and talking with friends about vaping, you decide that you are strongly opposed to it.

Which working thesis statement would be better?

- Vaping should be illegal because it can lead to serious health problems.

Many students do not like vaping.

Because the first option provides a debatable position, it is a better starting point for an Argument essay.

Next, you would need to draft several paragraphs to explain your position. These paragraphs could include facts that you learned in your research, such as statistics about vapers’ health problems, the cost of vaping, its effects on youth, its harmful effects on people nearby, and so on, as an appeal to logos . If you have a personal story about the effects of vaping, you might include that as well, either in a Body Paragraph or in your Introduction, as an appeal to pathos .

A strong Argument essay would not be complete with only your reasons in support of your position. You should also include a Counterargument, which will show your readers that you have carefully researched and considered both sides of your topic. This shows that you are taking a measured, scholarly approach to the topic – not an overly-emotional approach, or an approach which considers only one side. This helps to establish your ethos as the author. It shows your readers that you are thinking clearly and deeply about the topic, and your Concession (“this may be true”) acknowledges that you understand other opinions are possible.

Here are some ways to introduce a Counterargument:

- Some people believe that vaping is not as harmful as smoking cigarettes.

- Critics argue that vaping is safer than conventional cigarettes.

- On the other hand, one study has shown that vaping can help people quit smoking cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then go on to explain more about this position; you would give evidence here from your research about the point of view that opposes your own opinion.

Here are some ways to begin a Concession and Refutation:

- While this may be true for some adults, the risks of vaping for adolescents outweigh its benefits.

- Although these critics may have been correct before, new evidence shows that vaping is, in some cases, even more harmful than smoking.

- This may have been accurate for adults wishing to quit smoking; however, there are other methods available to help people stop using cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then continue your Refutation by explaining more reasons why the Counterargument is weak. This also serves to explain why your original Argument is strong. This is a good opportunity to prove to your readers that your original Argument is the most worthy, and to persuade them to agree with you.

Activity ~ Practice with Counterarguments, Concessions, and Refutations

A. Examine the following thesis statements with a partner. Is each one debatable?

B. Write your own Counterargument, Concession, and Refutation for each thesis statement.

Thesis Statements:

- Online classes are a better option than face-to-face classes for college students who have full-time jobs.

- Students who engage in cyberbullying should be expelled from school.

- Unvaccinated children pose risks to those around them.

- Governments should be allowed to regulate internet access within their countries.

Is this chapter:

…too easy, or you would like more detail? Read “ Further Your Understanding: Refutation and Rebuttal ” from Lumen’s Writing Skills Lab.

Note: links open in new tabs.

reasoning, logic

emotion, feeling, beliefs

moral character, credibility, trust, authority

goes against; believes the opposite of something

ENGLISH 087: Academic Advanced Writing Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Hutchison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Paragraphs: Concession

Transitions : although it is true that, certainly, despite, granted that, however, indeed, granted, I admit that, in fact, in spite of, it may appear that, naturally, nevertheless, of course, once in a while, sometimes, still, yet

Example : Mason (2007) and Holmes (2009) vehemently disagree on the fundamental components of primary school education. Despite this strong disagreement, the scholars do agree on the overall importance of formal education for all young children.

Explanation : In these two sentences, the author is highlighting a disagreement between the two scholars. The author begins the second sentence with the transition phrase, "Despite this strong disagreement," however, to make a concession that Mason and Holmes do agree on the importance of formal education for young children.

Transitions Video Playlist

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Academic Paragraphs: Introduction to Paragraphs and the MEAL Plan (video transcript)

- Academic Paragraphs: Types of Transitions Part 1: Transitions Between Paragraphs (video transcript)

- Academic Paragraphs: Types of Transitions Part 2: Transitions Within Paragraphs (video transcript)

- Academic Paragraphs: Appropriate Use of Explicit Transitions (video transcript)

- Engaging Writing: Incorporating Transitions (video transcript)

- Engaging Writing: Examples of Incorporating Transitions (video transcript)

- Previous Page: Chronology

- Next Page: Contradict

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Consider the following thesis for a short paper that analyzes different approaches to stopping climate change:

Climate activism that focuses on personal actions such as recycling obscures the need for systemic change that will be required to slow carbon emissions.

The author of this thesis is promising to make the case that personal actions not only will not solve the climate problem but may actually make the problem more difficult to solve. In order to make a convincing argument, the author will need to consider how thoughtful people might disagree with this claim. In this case, the author might anticipate the following counterarguments:

- By encouraging personal actions, climate activists may raise awareness of the problem and encourage people to support larger systemic change.

- Personal actions on a global level would actually make a difference.

- Personal actions may not make a difference, but they will not obscure the need for systemic solutions.

- Personal actions cannot be put into one category and must be differentiated.

In order to make a convincing argument, the author of this essay may need to address these potential counterarguments. But you don’t need to address every possible counterargument. Rather, you should engage counterarguments when doing so allows you to strengthen your own argument by explaining how it holds up in relation to other arguments.

How to address counterarguments

Once you have considered the potential counterarguments, you will need to figure out how to address them in your essay. In general, to address a counterargument, you’ll need to take the following steps.

- State the counterargument and explain why a reasonable reader could raise that counterargument.

- Counter the counterargument. How you grapple with a counterargument will depend on what you think it means for your argument. You may explain why your argument is still convincing, even in light of this other position. You may point to a flaw in the counterargument. You may concede that the counterargument gets something right but then explain why it does not undermine your argument. You may explain why the counterargument is not relevant. You may refine your own argument in response to the counterargument.

- Consider the language you are using to address the counterargument. Words like but or however signal to the reader that you are refuting the counterargument. Words like nevertheless or still signal to the reader that your argument is not diminished by the counterargument.

Here’s an example of a paragraph in which a counterargument is raised and addressed.

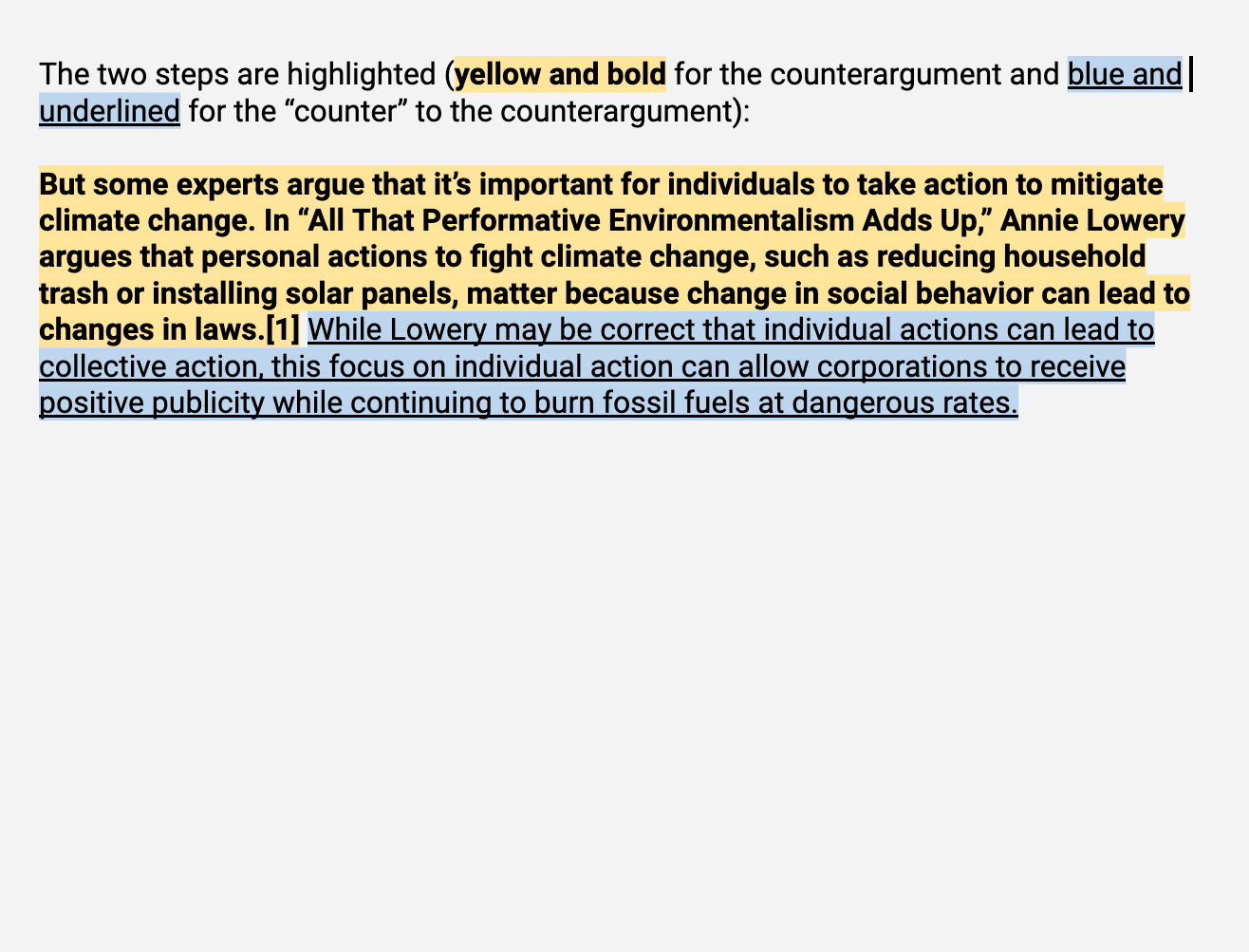

Image version

The two steps are marked with counterargument and “counter” to the counterargument: COUNTERARGUMENT/ But some experts argue that it’s important for individuals to take action to mitigate climate change. In “All That Performative Environmentalism Adds Up,” Annie Lowery argues that personal actions to fight climate change, such as reducing household trash or installing solar panels, matter because change in social behavior can lead to changes in laws. [1]

COUNTER TO THE COUNTERARGUMENT/ While Lowery may be correct that individual actions can lead to collective action, this focus on individual action can allow corporations to receive positive publicity while continuing to burn fossil fuels at dangerous rates.

Where to address counterarguments

There is no one right place for a counterargument—where you raise a particular counterargument will depend on how it fits in with the rest of your argument. The most common spots are the following:

- Before your conclusion This is a common and effective spot for a counterargument because it’s a chance to address anything that you think a reader might still be concerned about after you’ve made your main argument. Don’t put a counterargument in your conclusion, however. At that point, you won’t have the space to address it, and readers may come away confused—or less convinced by your argument.

- Before your thesis Often, your thesis will actually be a counterargument to someone else’s argument. In other words, you will be making your argument because someone else has made an argument that you disagree with. In those cases, you may want to offer that counterargument before you state your thesis to show your readers what’s at stake—someone else has made an unconvincing argument, and you are now going to make a better one.

- After your introduction In some cases, you may want to respond to a counterargument early in your essay, before you get too far into your argument. This is a good option when you think readers may need to understand why the counterargument is not as strong as your argument before you can even launch your own ideas. You might do this in the paragraph right after your thesis.

- Anywhere that makes sense As you draft an essay, you should always keep your readers in mind and think about where a thoughtful reader might disagree with you or raise an objection to an assertion or interpretation of evidence that you are offering. In those spots, you can introduce that potential objection and explain why it does not change your argument. If you think it does affect your argument, you can acknowledge that and explain why your argument is still strong.

[1] Annie Lowery, “All that Performative Environmentalism Adds Up.” The Atlantic . August 31, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/08/your-tote-bag-can-mak…

- picture_as_pdf Counterargument

How to Write a Conclusion for an Argumentative Essay: All Tips

Table of contents

- 1 What to Write in the Conclusion for an Argumentative Essay

- 2.1 Know how to structure your paper

- 3 How to Start the Conclusion of an Essay?

- 4.1 Example 1

- 4.2 Example 2

- 4.3 Example 3

- 4.4 Examples 4, 5

- 5 How to Finish an Argumentative Project Conclusion Paragraph

Want to write a perfect conclusion for your paper but don’t know how? Everyone has been there, and it’s never easy. It is the final part of your writing, so by the time you reach it, you have no energy and can’t focus.

Still, the conclusion part is crucial for the success of every paper. You have to give the final answer to the audience by restating your thesis and noting your claims and findings. If you think you can’t write one, you’d better buy an argumentative essay online and solve your problems.

In this article, you will find everything you need to know about a conclusion to an argumentative essay and how to write it.

What to Write in the Conclusion for an Argumentative Essay

To write a conclusion argumentative essay, you first need to recall all the key points of your writing. The college argumentative essay outline you have written can significantly assist you in this. After you have noted these points, you should restate your rephrased thesis and findings.

Except for those basic points, knowing how to conclude an argumentative essay also requires a few more things:

The first thing to pay attention to is your tone of writing. Make sure it is authoritative yet calm and informative. This way, you will assure readers that your work is essential for the case.

Next is your first sentence. How you start your conclusion does matter. You need to state what you did and why. That will remind the readers once again about what they have read.

After you write it, you will need to point out the key findings of your writing. You must note the important evidence you have written about in your paper. Keep it brief and connect them to your text conclusion.

The last step is to finish the conclusion of your argumentative essay in a meaningful way. Ensure a positive final sentence to make the reader reflect on your work and make them act.

Thus, writing a conclusion for an argumentative essay is a complex process. It can be not easy to come up with a good conclusion on your own, so don’t hesitate to seek essay assistance if you need it. Once again, no matter what kind of conclusion you write, it is crucial to have a good one. That goes even for argumentative essays, where you can write everything straight as it is. You can be assertive and direct without considering whether the reader will like your argument. Still, you must keep a good transition between the sections and stick to the basic structure and rules.

Author Note: Make sure not to present any new arguments or claims in the conclusion. This section of your paper is your final opinion. Writing further details, ideas, or irrelevant findings can ruin the text.

How to Format the Conclusion of an Argumentative Essay?

To format a conclusion, you have to follow a well-established standard. The best argumentative essay conclusion example includes a “lead” (opening statement). Then point out one vital factor from your paragraph. Usually, one point per paragraph, no more, or it will get too bulky. Finally, add an appropriate finale that will serve as a smooth exit of the whole paper, the final sentence.

By using the standard format, you will have an easier time when you have to write an argumentative essay conclusion. You can focus on the facts and tailor them to appeal to readers. That will re-convince them about your point for the case.

Here we can add that the final sentence should not always be smooth and friendly. When your conclusion tone is assertive, write the final part of the finale as a call to action—an attempt to affect the reader and make them want to research. To find out more about the matter or even take a stand with their own opinion.

Know how to structure your paper

- 12-point Times New Roman

- 0″ between paragraphs

- 1″ margin all around

- double-spaced (275 words/page) / single-spaced (550 words/page)

- 0.5″ first line of a paragraph

Knowing the exact way to structure a conclusion in an argumentative essay is crucial. Someone may say that it is not important. But this is one of the first things people pay attention to. So, you have to format the paper and its main points properly. In any assignment, the style of the text adheres to strict requirements. Usually, you can find them by asking your professor or checking the educational institution’s website.

In that sense, you must stick to proper formatting when writing a perfect argumentative essay . To get the best grade, you have to use the recommended formatting style , which can be APA, AP, or other. So remember, following the proper structure and formatting can make the critical points of your work stand out. As a result, your paper will look better, and your paper results will score higher.

Writing a perfect conclusion for your paper can be difficult, especially when you have no energy and can’t focus. Fortunately, PapersOwl.com is here to help. Our experienced writers can provide you with an excellent conclusion for your paper so that you can confidently submit it.

How to Start the Conclusion of an Essay?

A conclusion to an argumentative essay must go through various steps. The foremost will be the entry sentence. Then, restate your main idea and critical points from your writing. You can add a question or two, but it depends on the flow of your text. Note how it reads and make sure everything sounds smooth, and the transition is flawless.

Note: You should check your outline for significant findings or arguments. Do that before starting with the first sentence of your conclusion. Make sure not to miss important facts or add new ones by mistake.

Essay Conclusion Examples

If you are still trying to figure out what your conclusion should look like, check below. We have prepared how-to-end argumentative essay examples . These can give you an idea about the structure and format of your paper’s final point.

In this particular sample, the case is about global warming. So, the essay’s conclusion has to give a compelling reason why the reader and the public should act and prevent the issue. You must remember that what you write depends on the type of paper and should be unique.

“Throughout our text, we pointed out findings about the impact of global warming. Nature cannot sustain itself in the ever-changing climate. The ice caps melt, and the shorelines deteriorate, thus causing the extinction of both flora and fauna. Due to the persisting crisis, we must take action and use the best methods to protect the future of our planet.”

Some papers involve public policies and morals. In such cases, you must write in a tone that will feel morally right but will support and justify your arguments. Usually, you write such papers when your topic is pointing towards persuasion. Below, you can see an argumentative essay conclusion example for such texts.

“As time goes on, technology has changed how we, as a society, receive and use information. Media’s influence has been increasing throughout the social applications we use daily. The said impacts public opinion, as we can see from the participants in our study group. Most have stated that their primary information source is social media. These media get large funds from private entities to filter your content. This way, you see their ideas and become part of their audience. If you like your news free of filtering and want truthful information, you must act now and ensure your rights.”

- Free unlimited checks

- All common file formats

- Accurate results

- Intuitive interface

At one point or another, you will get an assignment to help with your career objectives. Usually, it is connected to your writing as you have to research specific matters. For example, bring out your point of view and make conclusions. You can quickly implement such tasks in essays like the argumentative one. Thus, you have to be ready to write a conclusion of an argumentative essay that can fit well and is decisive.

“Often, when you get the opportunity to launch a new business, you must grab it. Plan business meetings, solve the x, y, and z obstacles, and speed up the process. Business is about profit, producing more revenue, and creating an easily manageable structure. If you choose to act on a different undertaking, there will be risks a or b, which can lead to overstepping the estimated budgets.”

Examples 4, 5

As seen, the conclusion of an argumentative essay can depend on your moral choices. In other cases, on a figure of speech and even sensitivity towards an issue. So, some good argumentative essay topics need an emotional appeal to the reader.

Good conclusion paragraph examples for an argumentative essay can be about any topic. They can be something like whether abortion is a fundamental right for women. In such essay cases, your moral perspective plays a considerable role. But, no matter your point, it is crucial to state your ideas without offending anyone else.

“The right to give birth or not is fundamental for women. They must have it ensured. Otherwise, they have no control or option in their social relationships. The analysis showcases how an unwanted pregnancy can influence and determine the life of a young woman and her child. So without guaranteed rights, women are forced to use dangerous methods to retake ownership of their body, and that must change.” “Life is not a choice given by someone. It is a fundamental right guaranteed by the law. In that sense, denying an unborn child’s right to life is identical to denying any other person’s rights. Furthermore, studies have long proven that life begins with its inception. Therefore, carrying out policies of pro-choice is like murder. With that in mind, saving the unborn by speaking out for them is like giving their rights a voice.”

How to Finish an Argumentative Project Conclusion Paragraph

How to end an argumentative essay? The answer is a strong finishing line. The final sentence is what will leave a deep impression on your reader. Usually, we finish it smoothly in a cordial tone. It must be in a way that will make the reader think about the case or take some action. In other cases, the call to action is intense. It could be smoother, but its main goal is to influence the audience to contemplate and act.

Taking into consideration the importance of the last sentence, you must write it correctly. Remember that its point is to move the reader, but at the same time to explain why. It should look like, “ If we don’t do it now, we won’t be able to act in the future. ” If your sentence cuts the flow of the whole text, it will not appeal to your reader. If you are having trouble crafting the perfect conclusion for your argumentative essay, you can always pay for essay help from a professional writer to get the job done right.

Now you understand how to write a conclusion for an argumentative essay, but remember to catch up on the whole paper flow and finish it in the same tone. Use the call to action sentence and exit your essay smoothly while giving the readers ideas and making them think about the case. If you can’t, please check our argumentative essay writing services , which can easily tackle the task. Note that by getting it done by a professional, you can learn from examples. Besides, the text can get done in a few hours.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Conceding and Refuting in English

- Pronunciation & Conversation

- Writing Skills

- Reading Comprehension

- Business English

- Resources for Teachers

- TESOL Diploma, Trinity College London

- M.A., Music Performance, Cologne University of Music

- B.A., Vocal Performance, Eastman School of Music

Conceding and refuting are important language functions in English. Here are a few short definitions:

Concede : Admit that another person is right about something.

Refute : Prove that someone else is wrong about something.

Often, speakers of English will concede a point, only to refute a larger issue:

- It's true that working can be tedious. However, without a job, you won't be able to pay the bills.

- While you might say that the weather has been really bad this winter, it's important to remember that we needed lots of snow in the mountains.

- I agree with you that we need to improve our sales figures. On the other hand, I don't feel we should change our overall strategy at this time.

It's common to concede and refute at work when discussing strategy or brainstorming. Conceding and refuting are also very common in all types of debates including political and social issues.

When trying to make your point, it's a good idea to first frame the argument. Next, concede a point if applicable. Finally, refute a larger issue.

Framing the Issue

Begin by introducing a general belief that you would like to refute. You can use general statements, or speak about specific people that you would like to refute. Here are some formulas to help you frame the issue:

Person or institution to be refuted + feel / think / believe / insist / that + opinion to be refuted

- Some people feel that there is not enough charity in the world.

- Peter insists that we haven’t invested enough in research and development.

- The board of directors believes that students should take more standardized tests.

Making the Concession:

Use the concession to show that you have understood the gist of your opponent’s argument. Using this form, you will show that while a specific point is true, the overall understanding is incorrect. You can begin with an independent clause using subordinators that show opposition:

While it’s true / sensible / evident / likely that + specific benefit of argument,

While it’s evident that our competition has outspent us on, ... While it’s sensible to measure students’ aptitudes, ...

Although / Even though / Though it's true that + opinion,

Although it's true that our strategy hasn't worked to date, ... Even though it’s true that the country is currently struggling economically, ...

An alternate form is to first concede by stating that you agree or can see the advantage of something in a single sentence. Use concession verbs such as:

I concede that / I agree that / I admit that

Refuting the Point

Now it’s time to make your point. If you've used a subordinator (while, although, etc.), use your best argument to finish the sentence:

it’s also true / sensible / evident that + refutation it’s more important / essential / vital that + refutation the bigger issue / point is that + refutation we must remember / take into consideration / conclude that + refutation

… it’s also evident that financial resources will always be limited. … the bigger point is that we do not have the resources to spend. … we must remember that standardized testing such as the TOEFL leads to rote learning.

If you've made a concession in a single sentence, use a linking word or phrase such as however, nevertheless, on the contrary, or above all to state your refutation:

However, we currently do not have that capability. Nevertheless, we've succeeded in attracting more customers to our stores. Above all, the people's will needs to be respected.

Making Your Point

Once you’ve refuted a point, continue to provide evidence to further back up your point of view.

It is clear / essential / of utmost importance that + (opinion) I feel / believe / think that + (opinion)

- I believe that charity can lead to dependence.

- I think that we need to focus more on our successful products rather than develop new, untested merchandise.

- It is clear that students are not expanding their minds through rote learning for tests.

Complete Refutations

Let’s take a look a few concessions and refutations in their completed form:

Students feel that homework is an unnecessary strain on their limited time. While it's true that some teachers assign too much homework, we must remember the wisdom in the saying "practice makes perfect." It is essential that information we learn is repeated to fully become useful knowledge.

Some people insist that profit is the only viable motivation for a corporation. I concede that a company must profit to stay in business. However, the larger issue is that employee satisfaction leads to improved interactions with clients. It is clear that employees who feel they are compensated fairly will consistently give their best.

More English Functions

Conceding and refuting are known as language functions. In other words, language which is used to achieve a specific purpose. You can learn more about a wide variety of language functions and how to use them in everyday English.

- Modifying Words and Phrases to Express Opinions

- Comparing and Contrasting in English

- Teaching Conversational Skills Tips and Strategies

- Subordinate Clauses: Concessive, Time, Place and Reason Clauses

- Text Organization

- Violence in the Media Needs To Be Regulated

- Compromise Role Play Lesson

- Phrases for Performing Well in Business Meetings

- Persuasive Writing: For and Against

- Adverb Placement in English

- The Challenge of Teaching Listening Skills

- Paragraph Writing

- Intermediate Level English Practice: Tenses and Vocabulary

- Men and Women: Equal at Last?

- How to Use the Preposition 'To'

- Sentence Connectors: Showing Opposition in Written English

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Rebuttal Sections

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

In order to present a fair and convincing message, you may need to anticipate, research, and outline some of the common positions (arguments) that dispute your thesis. If the situation (purpose) calls for you to do this, you will present and then refute these other positions in the rebuttal section of your essay.

It is important to consider other positions because in most cases, your primary audience will be fence-sitters. Fence-sitters are people who have not decided which side of the argument to support.

People who are on your side of the argument will not need a lot of information to align with your position. People who are completely against your argument—perhaps for ethical or religious reasons—will probably never align with your position no matter how much information you provide. Therefore, the audience you should consider most important are those people who haven't decided which side of the argument they will support—the fence-sitters.

In many cases, these fence-sitters have not decided which side to align with because they see value in both positions. Therefore, to not consider opposing positions to your own in a fair manner may alienate fence-sitters when they see that you are not addressing their concerns or discussion opposing positions at all.

Organizing your rebuttal section