7.3 Problem-Solving

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

The study of human and animal problem solving processes has provided much insight toward the understanding of our conscious experience and led to advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Essentially much of cognitive science today represents studies of how we consciously and unconsciously make decisions and solve problems. For instance, when encountered with a large amount of information, how do we go about making decisions about the most efficient way of sorting and analyzing all the information in order to find what you are looking for as in visual search paradigms in cognitive psychology. Or in a situation where a piece of machinery is not working properly, how do we go about organizing how to address the issue and understand what the cause of the problem might be. How do we sort the procedures that will be needed and focus attention on what is important in order to solve problems efficiently. Within this section we will discuss some of these issues and examine processes related to human, animal and computer problem solving.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When people are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

Problems themselves can be classified into two different categories known as ill-defined and well-defined problems (Schacter, 2009). Ill-defined problems represent issues that do not have clear goals, solution paths, or expected solutions whereas well-defined problems have specific goals, clearly defined solutions, and clear expected solutions. Problem solving often incorporates pragmatics (logical reasoning) and semantics (interpretation of meanings behind the problem), and also in many cases require abstract thinking and creativity in order to find novel solutions. Within psychology, problem solving refers to a motivational drive for reading a definite “goal” from a present situation or condition that is either not moving toward that goal, is distant from it, or requires more complex logical analysis for finding a missing description of conditions or steps toward that goal. Processes relating to problem solving include problem finding also known as problem analysis, problem shaping where the organization of the problem occurs, generating alternative strategies, implementation of attempted solutions, and verification of the selected solution. Various methods of studying problem solving exist within the field of psychology including introspection, behavior analysis and behaviorism, simulation, computer modeling, and experimentation.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them (table below). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error. The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

Further problem solving strategies have been identified (listed below) that incorporate flexible and creative thinking in order to reach solutions efficiently.

Additional Problem Solving Strategies :

- Abstraction – refers to solving the problem within a model of the situation before applying it to reality.

- Analogy – is using a solution that solves a similar problem.

- Brainstorming – refers to collecting an analyzing a large amount of solutions, especially within a group of people, to combine the solutions and developing them until an optimal solution is reached.

- Divide and conquer – breaking down large complex problems into smaller more manageable problems.

- Hypothesis testing – method used in experimentation where an assumption about what would happen in response to manipulating an independent variable is made, and analysis of the affects of the manipulation are made and compared to the original hypothesis.

- Lateral thinking – approaching problems indirectly and creatively by viewing the problem in a new and unusual light.

- Means-ends analysis – choosing and analyzing an action at a series of smaller steps to move closer to the goal.

- Method of focal objects – putting seemingly non-matching characteristics of different procedures together to make something new that will get you closer to the goal.

- Morphological analysis – analyzing the outputs of and interactions of many pieces that together make up a whole system.

- Proof – trying to prove that a problem cannot be solved. Where the proof fails becomes the starting point or solving the problem.

- Reduction – adapting the problem to be as similar problems where a solution exists.

- Research – using existing knowledge or solutions to similar problems to solve the problem.

- Root cause analysis – trying to identify the cause of the problem.

The strategies listed above outline a short summary of methods we use in working toward solutions and also demonstrate how the mind works when being faced with barriers preventing goals to be reached.

One example of means-end analysis can be found by using the Tower of Hanoi paradigm . This paradigm can be modeled as a word problems as demonstrated by the Missionary-Cannibal Problem :

Missionary-Cannibal Problem

Three missionaries and three cannibals are on one side of a river and need to cross to the other side. The only means of crossing is a boat, and the boat can only hold two people at a time. Your goal is to devise a set of moves that will transport all six of the people across the river, being in mind the following constraint: The number of cannibals can never exceed the number of missionaries in any location. Remember that someone will have to also row that boat back across each time.

Hint : At one point in your solution, you will have to send more people back to the original side than you just sent to the destination.

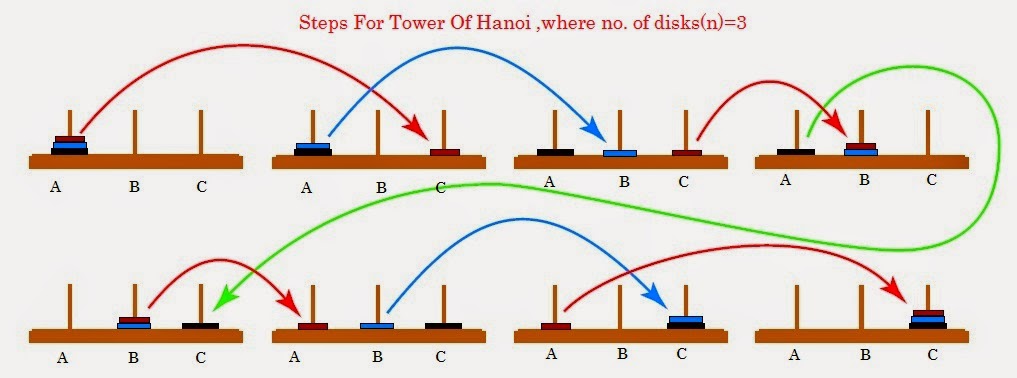

The actual Tower of Hanoi problem consists of three rods sitting vertically on a base with a number of disks of different sizes that can slide onto any rod. The puzzle starts with the disks in a neat stack in ascending order of size on one rod, the smallest at the top making a conical shape. The objective of the puzzle is to move the entire stack to another rod obeying the following rules:

- 1. Only one disk can be moved at a time.

- 2. Each move consists of taking the upper disk from one of the stacks and placing it on top of another stack or on an empty rod.

- 3. No disc may be placed on top of a smaller disk.

Figure 7.02. Steps for solving the Tower of Hanoi in the minimum number of moves when there are 3 disks.

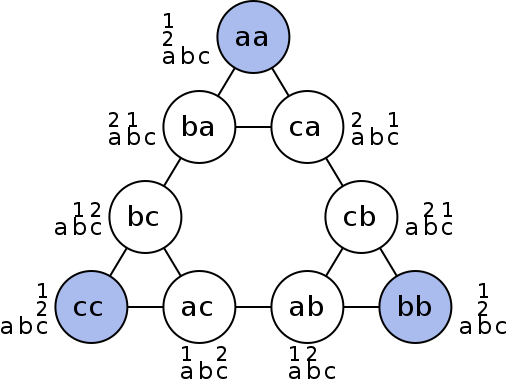

Figure 7.03. Graphical representation of nodes (circles) and moves (lines) of Tower of Hanoi.

The Tower of Hanoi is a frequently used psychological technique to study problem solving and procedure analysis. A variation of the Tower of Hanoi known as the Tower of London has been developed which has been an important tool in the neuropsychological diagnosis of executive function disorders and their treatment.

GESTALT PSYCHOLOGY AND PROBLEM SOLVING

As you may recall from the sensation and perception chapter, Gestalt psychology describes whole patterns, forms and configurations of perception and cognition such as closure, good continuation, and figure-ground. In addition to patterns of perception, Wolfgang Kohler, a German Gestalt psychologist traveled to the Spanish island of Tenerife in order to study animals behavior and problem solving in the anthropoid ape.

As an interesting side note to Kohler’s studies of chimp problem solving, Dr. Ronald Ley, professor of psychology at State University of New York provides evidence in his book A Whisper of Espionage (1990) suggesting that while collecting data for what would later be his book The Mentality of Apes (1925) on Tenerife in the Canary Islands between 1914 and 1920, Kohler was additionally an active spy for the German government alerting Germany to ships that were sailing around the Canary Islands. Ley suggests his investigations in England, Germany and elsewhere in Europe confirm that Kohler had served in the German military by building, maintaining and operating a concealed radio that contributed to Germany’s war effort acting as a strategic outpost in the Canary Islands that could monitor naval military activity approaching the north African coast.

While trapped on the island over the course of World War 1, Kohler applied Gestalt principles to animal perception in order to understand how they solve problems. He recognized that the apes on the islands also perceive relations between stimuli and the environment in Gestalt patterns and understand these patterns as wholes as opposed to pieces that make up a whole. Kohler based his theories of animal intelligence on the ability to understand relations between stimuli, and spent much of his time while trapped on the island investigation what he described as insight , the sudden perception of useful or proper relations. In order to study insight in animals, Kohler would present problems to chimpanzee’s by hanging some banana’s or some kind of food so it was suspended higher than the apes could reach. Within the room, Kohler would arrange a variety of boxes, sticks or other tools the chimpanzees could use by combining in patterns or organizing in a way that would allow them to obtain the food (Kohler & Winter, 1925).

While viewing the chimpanzee’s, Kohler noticed one chimp that was more efficient at solving problems than some of the others. The chimp, named Sultan, was able to use long poles to reach through bars and organize objects in specific patterns to obtain food or other desirables that were originally out of reach. In order to study insight within these chimps, Kohler would remove objects from the room to systematically make the food more difficult to obtain. As the story goes, after removing many of the objects Sultan was used to using to obtain the food, he sat down ad sulked for a while, and then suddenly got up going over to two poles lying on the ground. Without hesitation Sultan put one pole inside the end of the other creating a longer pole that he could use to obtain the food demonstrating an ideal example of what Kohler described as insight. In another situation, Sultan discovered how to stand on a box to reach a banana that was suspended from the rafters illustrating Sultan’s perception of relations and the importance of insight in problem solving.

Grande (another chimp in the group studied by Kohler) builds a three-box structure to reach the bananas, while Sultan watches from the ground. Insight , sometimes referred to as an “Ah-ha” experience, was the term Kohler used for the sudden perception of useful relations among objects during problem solving (Kohler, 1927; Radvansky & Ashcraft, 2013).

Solving puzzles.

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below (see figure) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

How long did it take you to solve this sudoku puzzle? (You can see the answer at the end of this section.)

Here is another popular type of puzzle (figure below) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

Did you figure it out? (The answer is at the end of this section.) Once you understand how to crack this puzzle, you won’t forget.

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below (figure below). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

What steps did you take to solve this puzzle? You can read the solution at the end of this section.

Pitfalls to problem solving.

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in the table below.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in the figure below? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in the figures above? Here are the answers.

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

References:

Openstax Psychology text by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett and Marion Perlmutter licensed under CC BY v4.0. https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology

Review Questions:

1. A specific formula for solving a problem is called ________.

a. an algorithm

b. a heuristic

c. a mental set

d. trial and error

2. Solving the Tower of Hanoi problem tends to utilize a ________ strategy of problem solving.

a. divide and conquer

b. means-end analysis

d. experiment

3. A mental shortcut in the form of a general problem-solving framework is called ________.

4. Which type of bias involves becoming fixated on a single trait of a problem?

a. anchoring bias

b. confirmation bias

c. representative bias

d. availability bias

5. Which type of bias involves relying on a false stereotype to make a decision?

6. Wolfgang Kohler analyzed behavior of chimpanzees by applying Gestalt principles to describe ________.

a. social adjustment

b. student load payment options

c. emotional learning

d. insight learning

7. ________ is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for.

a. functional fixedness

c. working memory

Critical Thinking Questions:

1. What is functional fixedness and how can overcoming it help you solve problems?

2. How does an algorithm save you time and energy when solving a problem?

Personal Application Question:

1. Which type of bias do you recognize in your own decision making processes? How has this bias affected how you’ve made decisions in the past and how can you use your awareness of it to improve your decisions making skills in the future?

anchoring bias

availability heuristic

confirmation bias

functional fixedness

hindsight bias

problem-solving strategy

representative bias

trial and error

working backwards

Answers to Exercises

algorithm: problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

anchoring bias: faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

availability heuristic: faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

confirmation bias: faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

functional fixedness: inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

heuristic: mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

hindsight bias: belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

mental set: continually using an old solution to a problem without results

problem-solving strategy: method for solving problems

representative bias: faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

trial and error: problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

working backwards: heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 4 min read

The Problem-Solving Process

Looking at the basic problem-solving process to help keep you on the right track.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Problem-solving is an important part of planning and decision-making. The process has much in common with the decision-making process, and in the case of complex decisions, can form part of the process itself.

We face and solve problems every day, in a variety of guises and of differing complexity. Some, such as the resolution of a serious complaint, require a significant amount of time, thought and investigation. Others, such as a printer running out of paper, are so quickly resolved they barely register as a problem at all.

Despite the everyday occurrence of problems, many people lack confidence when it comes to solving them, and as a result may chose to stay with the status quo rather than tackle the issue. Broken down into steps, however, the problem-solving process is very simple. While there are many tools and techniques available to help us solve problems, the outline process remains the same.

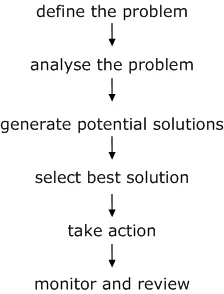

The main stages of problem-solving are outlined below, though not all are required for every problem that needs to be solved.

1. Define the Problem

Clarify the problem before trying to solve it. A common mistake with problem-solving is to react to what the problem appears to be, rather than what it actually is. Write down a simple statement of the problem, and then underline the key words. Be certain there are no hidden assumptions in the key words you have underlined. One way of doing this is to use a synonym to replace the key words. For example, ‘We need to encourage higher productivity ’ might become ‘We need to promote superior output ’ which has a different meaning.

2. Analyze the Problem

Ask yourself, and others, the following questions.

- Where is the problem occurring?

- When is it occurring?

- Why is it happening?

Be careful not to jump to ‘who is causing the problem?’. When stressed and faced with a problem it is all too easy to assign blame. This, however, can cause negative feeling and does not help to solve the problem. As an example, if an employee is underperforming, the root of the problem might lie in a number of areas, such as lack of training, workplace bullying or management style. To assign immediate blame to the employee would not therefore resolve the underlying issue.

Once the answers to the where, when and why have been determined, the following questions should also be asked:

- Where can further information be found?

- Is this information correct, up-to-date and unbiased?

- What does this information mean in terms of the available options?

3. Generate Potential Solutions

When generating potential solutions it can be a good idea to have a mixture of ‘right brain’ and ‘left brain’ thinkers. In other words, some people who think laterally and some who think logically. This provides a balance in terms of generating the widest possible variety of solutions while also being realistic about what can be achieved. There are many tools and techniques which can help produce solutions, including thinking about the problem from a number of different perspectives, and brainstorming, where a team or individual write as many possibilities as they can think of to encourage lateral thinking and generate a broad range of potential solutions.

4. Select Best Solution

When selecting the best solution, consider:

- Is this a long-term solution, or a ‘quick fix’?

- Is the solution achievable in terms of available resources and time?

- Are there any risks associated with the chosen solution?

- Could the solution, in itself, lead to other problems?

This stage in particular demonstrates why problem-solving and decision-making are so closely related.

5. Take Action

In order to implement the chosen solution effectively, consider the following:

- What will the situation look like when the problem is resolved?

- What needs to be done to implement the solution? Are there systems or processes that need to be adjusted?

- What will be the success indicators?

- What are the timescales for the implementation? Does the scale of the problem/implementation require a project plan?

- Who is responsible?

Once the answers to all the above questions are written down, they can form the basis of an action plan.

6. Monitor and Review

One of the most important factors in successful problem-solving is continual observation and feedback. Use the success indicators in the action plan to monitor progress on a regular basis. Is everything as expected? Is everything on schedule? Keep an eye on priorities and timelines to prevent them from slipping.

If the indicators are not being met, or if timescales are slipping, consider what can be done. Was the plan realistic? If so, are sufficient resources being made available? Are these resources targeting the correct part of the plan? Or does the plan need to be amended? Regular review and discussion of the action plan is important so small adjustments can be made on a regular basis to help keep everything on track.

Once all the indicators have been met and the problem has been resolved, consider what steps can now be taken to prevent this type of problem recurring? It may be that the chosen solution already prevents a recurrence, however if an interim or partial solution has been chosen it is important not to lose momentum.

Problems, by their very nature, will not always fit neatly into a structured problem-solving process. This process, therefore, is designed as a framework which can be adapted to individual needs and nature.

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Tips for Dealing with Customers Effectively

Pain Points Podcast - Procrastination

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Pain points podcast - starting a new job.

How to Hit the Ground Running!

Ten Dos and Don'ts of Career Conversations

How to talk to team members about their career aspirations.

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Finance management.

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Which of the following is the process of generating potential solutions and deciding on the best one? True or False: Successful problem solving involves looking at the outcome of the situation and learning from the process. Fill in the blank: _______ is the ability to think clearly and rationally. Which of the following is NOT recommended as a ...

Finding a suitable solution for issues can be accomplished by following the basic four-step problem-solving process and methodology outlined below. Step. Characteristics. 1. Define the problem. Differentiate fact from opinion. Specify underlying causes. Consult each faction involved for information. State the problem specifically.

Additional Problem Solving Strategies:. Abstraction - refers to solving the problem within a model of the situation before applying it to reality.; Analogy - is using a solution that solves a similar problem.; Brainstorming - refers to collecting an analyzing a large amount of solutions, especially within a group of people, to combine the solutions and developing them until an optimal ...

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue. The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything ...

The Problem-Solving Process. Problem-solving is an important part of planning and decision-making. The process has much in common with the decision-making process, and in the case of complex decisions, can form part of the process itself. We face and solve problems every day, in a variety of guises and of differing complexity.

In general, effective problem-solving strategies include the following steps: Define the problem. Come up with alternative solutions. Decide on a solution. Implement the solution. Problem-solving ...

By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we're solving, what are the components of the problem that we're solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we've learned back into a compelling story.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles: 1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking. Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these ...

Computer Science. Computer Science questions and answers. which of the following is true about problem solving? a) recognizing problems involves stating goals and objectives. b) analyzing the problem involves characterizing the possible decisions. c) decision making involves translating the results of the model in the organization.

which of the following is true about problem solving? a) recognizing problems involves stating goals and objectives. b) analyzing the problem involves characterizing the possible decisions. c) decision making involves translating the results of the model in the organization. d) structuring the problem involves identifying constraints.

The true statement about solving problems is: Knowing how to find workable solutions to problems can help you stay on track to meet your goals.. Effective problem-solving skills are invaluable in both personal and professional life.They allow individuals to tackle a wide range of issues, whether simple or complex, expected or unexpected.. A competent problem solver can analyze situations ...

Kaplan and Simon's experiment presented different versions of the mutilated checkerboard problem. The main purpose of their experiment was to demonstrate that a. people often have to backtrack within the problem space to arrive at an answer to a problem b. the way the problem is represented can influence the ease of problem solving c. people arrive at the solution to an insight problem ...

Which of the following is true of algorithms and heuristics used for solving real-life problems? Multiple Choice Heuristics guarantee a solution to a problem. Algorithms are faster than heuristics. Heuristics are shortcut strategies. Algorithms lead to different answers to a given problem.

Which of the following statements is true about problem - solving? The first step of the problem - solving process is problem disaggreg.ation. There are six steps of problem - solving in the bulletproof problem - solving framework. Good problem - solving is a process, not a quick mental calculation or a logical deduction.

1.) Which of the following statements is true about problem-solving? Good problem-solving is a process, not a quick mental calculation or a logical deduction. The first step of the problem-solving process is problem disaggregation. The process of problem-solving is over once your analysis is complete. There are six steps of problem-solving in ...

Which of the following is true about solutions in problem solving?A solution should not have any possible alternatives.A solution's continuing impact must be determined.A solution's success must not be measured.A solution should be discussed during the first step of problem solving.