- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Decision-Making and Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

Identifying and Structuring Problems

Investigating Ideas and Solutions

Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Making decisions and solving problems are two key areas in life, whether you are at home or at work. Whatever you’re doing, and wherever you are, you are faced with countless decisions and problems, both small and large, every day.

Many decisions and problems are so small that we may not even notice them. Even small decisions, however, can be overwhelming to some people. They may come to a halt as they consider their dilemma and try to decide what to do.

Small and Large Decisions

In your day-to-day life you're likely to encounter numerous 'small decisions', including, for example:

Tea or coffee?

What shall I have in my sandwich? Or should I have a salad instead today?

What shall I wear today?

Larger decisions may occur less frequently but may include:

Should we repaint the kitchen? If so, what colour?

Should we relocate?

Should I propose to my partner? Do I really want to spend the rest of my life with him/her?

These decisions, and others like them, may take considerable time and effort to make.

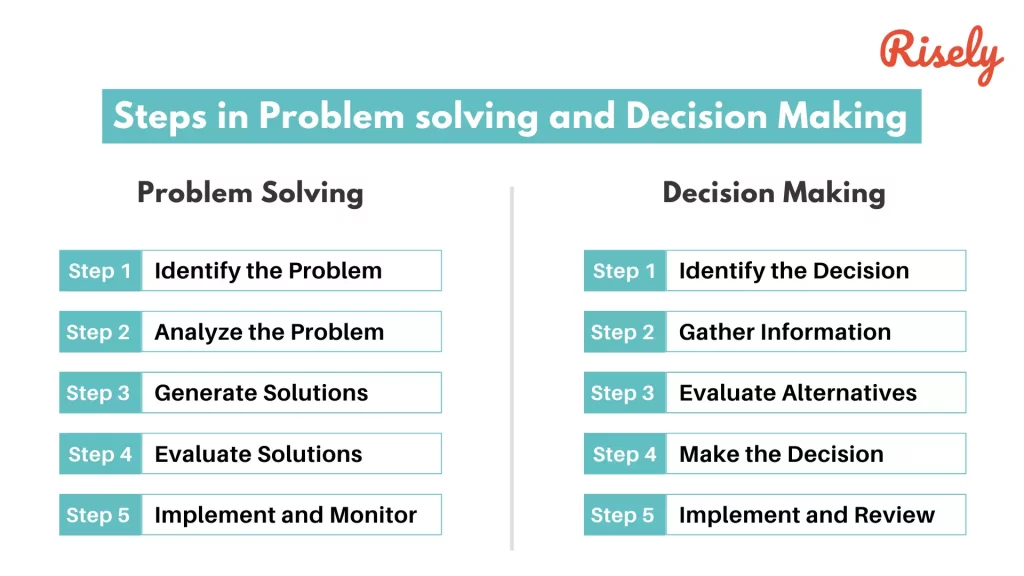

The relationship between decision-making and problem-solving is complex. Decision-making is perhaps best thought of as a key part of problem-solving: one part of the overall process.

Our approach at Skills You Need is to set out a framework to help guide you through the decision-making process. You won’t always need to use the whole framework, or even use it at all, but you may find it useful if you are a bit ‘stuck’ and need something to help you make a difficult decision.

Decision Making

Effective Decision-Making

This page provides information about ways of making a decision, including basing it on logic or emotion (‘gut feeling’). It also explains what can stop you making an effective decision, including too much or too little information, and not really caring about the outcome.

A Decision-Making Framework

This page sets out one possible framework for decision-making.

The framework described is quite extensive, and may seem quite formal. But it is also a helpful process to run through in a briefer form, for smaller problems, as it will help you to make sure that you really do have all the information that you need.

Problem Solving

Introduction to Problem-Solving

This page provides a general introduction to the idea of problem-solving. It explores the idea of goals (things that you want to achieve) and barriers (things that may prevent you from achieving your goals), and explains the problem-solving process at a broad level.

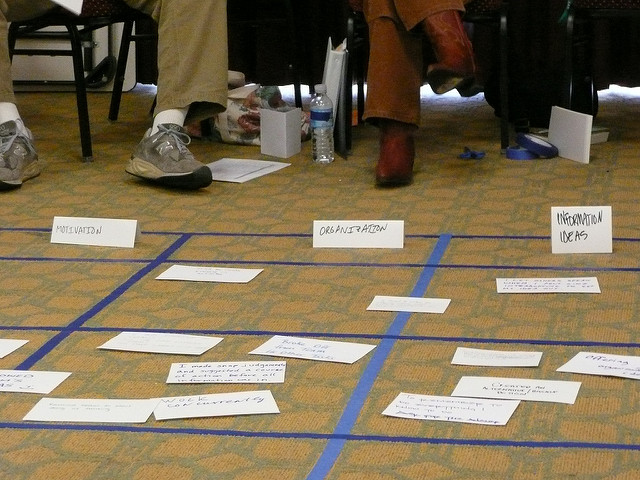

The first stage in solving any problem is to identify it, and then break it down into its component parts. Even the biggest, most intractable-seeming problems, can become much more manageable if they are broken down into smaller parts. This page provides some advice about techniques you can use to do so.

Sometimes, the possible options to address your problem are obvious. At other times, you may need to involve others, or think more laterally to find alternatives. This page explains some principles, and some tools and techniques to help you do so.

Having generated solutions, you need to decide which one to take, which is where decision-making meets problem-solving. But once decided, there is another step: to deliver on your decision, and then see if your chosen solution works. This page helps you through this process.

‘Social’ problems are those that we encounter in everyday life, including money trouble, problems with other people, health problems and crime. These problems, like any others, are best solved using a framework to identify the problem, work out the options for addressing it, and then deciding which option to use.

This page provides more information about the key skills needed for practical problem-solving in real life.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Interpersonal Skills eBooks.

Develop your interpersonal skills with our series of eBooks. Learn about and improve your communication skills, tackle conflict resolution, mediate in difficult situations, and develop your emotional intelligence.

Guiding you through the key skills needed in life

As always at Skills You Need, our approach to these key skills is to provide practical ways to manage the process, and to develop your skills.

Neither problem-solving nor decision-making is an intrinsically difficult process and we hope you will find our pages useful in developing your skills.

Start with: Decision Making Problem Solving

See also: Improving Communication Interpersonal Communication Skills Building Confidence

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

This is how effective teams navigate the decision-making process

Zero Magic 8 Balls required.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Flipping a coin. Throwing a dart at a board. Pulling a slip of paper out of a hat.

Sure, they’re all ways to make a choice. But they all hinge on random chance rather than analysis, reflection, and strategy — you know, the things you actually need to make the big, meaty decisions that have major impacts.

So, set down that Magic 8 Ball and back away slowly. Let’s walk through the standard framework for decision-making that will help you and your team pinpoint the problem, consider your options, and make your most informed selection. Here’s a closer look at each of the seven steps of the decision-making process, and how to approach each one.

Step 1: Identify the decision

Most of us are eager to tie on our superhero capes and jump into problem-solving mode — especially if our team is depending on a solution. But you can’t solve a problem until you have a full grasp on what it actually is .

This first step focuses on getting the lay of the land when it comes to your decision. What specific problem are you trying to solve? What goal are you trying to achieve?

How to do it:

- Use the 5 whys analysis to go beyond surface-level symptoms and understand the root cause of a problem.

- Try problem framing to dig deep on the ins and outs of whatever problem your team is fixing. The point is to define the problem, not solve it.

⚠️ Watch out for: Decision fatigue , which is the tendency to make worse decisions as a result of needing to make too many of them. Making choices is mentally taxing , which is why it’s helpful to pinpoint one decision at a time.

2. Gather information

Your team probably has a few hunches and best guesses, but those can lead to knee-jerk reactions. Take care to invest adequate time and research into your decision.

This step is when you build your case, so to speak. Collect relevant information — that could be data, customer stories, information about past projects, feedback, or whatever else seems pertinent. You’ll use that to make decisions that are informed, rather than impulsive.

- Host a team mindmapping session to freely explore ideas and make connections between them. It can help you identify what information will best support the process.

- Create a project poster to define your goals and also determine what information you already know and what you still need to find out.

⚠️ Watch out for: Information bias , or the tendency to seek out information even if it won’t impact your action. We have the tendency to think more information is always better, but pulling together a bunch of facts and insights that aren’t applicable may cloud your judgment rather than offer clarity.

3. Identify alternatives

Use divergent thinking to generate fresh ideas in your next brainstorm

Blame the popularity of the coin toss, but making a decision often feels like choosing between only two options. Do you want heads or tails? Door number one or door number two? In reality, your options aren’t usually so cut and dried. Take advantage of this opportunity to get creative and brainstorm all sorts of routes or solutions. There’s no need to box yourselves in.

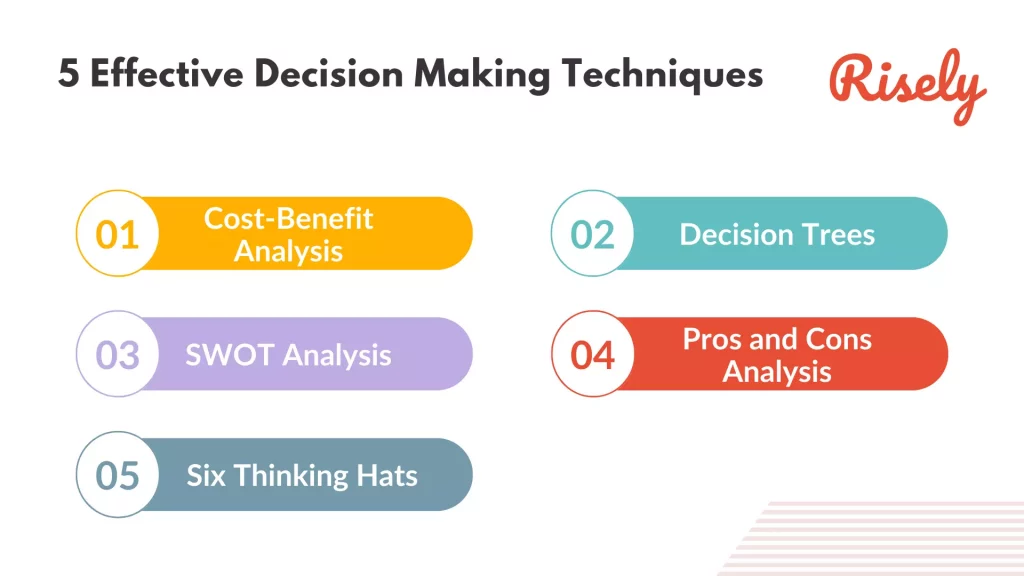

- Use the Six Thinking Hats technique to explore the problem or goal from all sides: information, emotions and instinct, risks, benefits, and creativity. It can help you and your team break away from your typical roles or mindsets and think more freely.

- Try brainwriting so team members can write down their ideas independently before sharing with the group. Research shows that this quiet, lone thinking time can boost psychological safety and generate more creative suggestions .

⚠️ Watch out for: Groupthink , which is the tendency of a group to make non-optimal decisions in the interest of conformity. People don’t want to rock the boat, so they don’t speak up.

4. Consider the evidence

Armed with your list of alternatives, it’s time to take a closer look and determine which ones could be worth pursuing. You and your team should ask questions like “How will this solution address the problem or achieve the goal?” and “What are the pros and cons of this option?”

Be honest with your answers (and back them up with the information you already collected when you can). Remind the team that this isn’t about advocating for their own suggestions to “win” — it’s about whittling your options down to the best decision.

How to do it:

- Use a SWOT analysis to dig into the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the options you’re seriously considering.

- Run a project trade-off analysis to understand what constraints (such as time, scope, or cost) the team is most willing to compromise on if needed.

⚠️ Watch out for: Extinction by instinct , which is the urge to make a decision just to get it over with. You didn’t come this far to settle for a “good enough” option!

5. Choose among the alternatives

This is it — it’s the big moment when you and the team actually make the decision. You’ve identified all possible options, considered the supporting evidence, and are ready to choose how you’ll move forward.

However, bear in mind that there’s still a surprising amount of room for flexibility here. Maybe you’ll modify an alternative or combine a few suggested solutions together to land on the best fit for your problem and your team.

- Use the DACI framework (that stands for “driver, approver, contributor, informed”) to understand who ultimately has the final say in decisions. The decision-making process can be collaborative, but eventually someone needs to be empowered to make the final call.

- Try a simple voting method for decisions that are more democratized. You’ll simply tally your team’s votes and go with the majority.

⚠️ Watch out for: Analysis paralysis , which is when you overthink something to such a great degree that you feel overwhelmed and freeze when it’s time to actually make a choice.

6. Take action

Making a big decision takes a hefty amount of work, but it’s only the first part of the process — now you need to actually implement it.

It’s tempting to think that decisions will work themselves out once they’re made. But particularly in a team setting, it’s crucial to invest just as much thought and planning into communicating the decision and successfully rolling it out.

- Create a stakeholder communications plan to determine how you’ll keep various people — direct team members, company leaders, customers, or whoever else has an active interest in your decision — in the loop on your progress.

- Define the goals, signals, and measures of your decision so you’ll have an easier time aligning the team around the next steps and determining whether or not they’re successful.

⚠️Watch out for: Self-doubt, or the tendency to question whether or not you’re making the right move. While we’re hardwired for doubt , now isn’t the time to be a skeptic about your decision. You and the team have done the work, so trust the process.

7. Review your decision

9 retrospective techniques that won’t bore your team to tears

As the decision itself starts to shake out, it’s time to take a look in the rearview mirror and reflect on how things went.

Did your decision work out the way you and the team hoped? What happened? Examine both the good and the bad. What should you keep in mind if and when you need to make this sort of decision again?

- Do a 4 L’s retrospective to talk through what you and the team loved, loathed, learned, and longed for as a result of that decision.

- Celebrate any wins (yes, even the small ones ) related to that decision. It gives morale a good kick in the pants and can also help make future decisions feel a little less intimidating.

⚠️ Watch out for: Hindsight bias , or the tendency to look back on events with the knowledge you have now and beat yourself up for not knowing better at the time. Even with careful thought and planning, some decisions don’t work out — but you can only operate with the information you have at the time.

Making smart decisions about the decision-making process

You’re probably picking up on the fact that the decision-making process is fairly comprehensive. And the truth is that the model is likely overkill for the small and inconsequential decisions you or your team members need to make.

Deciding whether you should order tacos or sandwiches for your team offsite doesn’t warrant this much discussion and elbow grease. But figuring out which major project to prioritize next? That requires some careful and collaborative thought.

It all comes back to the concept of satisficing versus maximizing , which are two different perspectives on decision making. Here’s the gist:

- Maximizers aim to get the very best out of every single decision.

- Satisficers are willing to settle for “good enough” rather than obsessing over achieving the best outcome.

One of those isn’t necessarily better than the other — and, in fact, they both have their time and place.

A major decision with far-reaching impacts deserves some fixation and perfectionism. However, hemming and hawing over trivial choices ( “Should we start our team meeting with casual small talk or a structured icebreaker?” ) will only cause added stress, frustration, and slowdowns.

As with anything else, it’s worth thinking about the potential impacts to determine just how much deliberation and precision a decision actually requires.

Decision-making is one of those things that’s part art and part science. You’ll likely have some gut feelings and instincts that are worth taking into account. But those should also be complemented with plenty of evidence, evaluation, and collaboration.

The decision-making process is a framework that helps you strike that balance. Follow the seven steps and you and your team can feel confident in the decisions you make — while leaving the darts and coins where they belong.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Problem-Solving Strategies and Obstacles

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

JGI / Jamie Grill / Getty Images

- Application

- Improvement

From deciding what to eat for dinner to considering whether it's the right time to buy a house, problem-solving is a large part of our daily lives. Learn some of the problem-solving strategies that exist and how to use them in real life, along with ways to overcome obstacles that are making it harder to resolve the issues you face.

What Is Problem-Solving?

In cognitive psychology , the term 'problem-solving' refers to the mental process that people go through to discover, analyze, and solve problems.

A problem exists when there is a goal that we want to achieve but the process by which we will achieve it is not obvious to us. Put another way, there is something that we want to occur in our life, yet we are not immediately certain how to make it happen.

Maybe you want a better relationship with your spouse or another family member but you're not sure how to improve it. Or you want to start a business but are unsure what steps to take. Problem-solving helps you figure out how to achieve these desires.

The problem-solving process involves:

- Discovery of the problem

- Deciding to tackle the issue

- Seeking to understand the problem more fully

- Researching available options or solutions

- Taking action to resolve the issue

Before problem-solving can occur, it is important to first understand the exact nature of the problem itself. If your understanding of the issue is faulty, your attempts to resolve it will also be incorrect or flawed.

Problem-Solving Mental Processes

Several mental processes are at work during problem-solving. Among them are:

- Perceptually recognizing the problem

- Representing the problem in memory

- Considering relevant information that applies to the problem

- Identifying different aspects of the problem

- Labeling and describing the problem

Problem-Solving Strategies

There are many ways to go about solving a problem. Some of these strategies might be used on their own, or you may decide to employ multiple approaches when working to figure out and fix a problem.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that, by following certain "rules" produces a solution. Algorithms are commonly used in mathematics to solve division or multiplication problems. But they can be used in other fields as well.

In psychology, algorithms can be used to help identify individuals with a greater risk of mental health issues. For instance, research suggests that certain algorithms might help us recognize children with an elevated risk of suicide or self-harm.

One benefit of algorithms is that they guarantee an accurate answer. However, they aren't always the best approach to problem-solving, in part because detecting patterns can be incredibly time-consuming.

There are also concerns when machine learning is involved—also known as artificial intelligence (AI)—such as whether they can accurately predict human behaviors.

Heuristics are shortcut strategies that people can use to solve a problem at hand. These "rule of thumb" approaches allow you to simplify complex problems, reducing the total number of possible solutions to a more manageable set.

If you find yourself sitting in a traffic jam, for example, you may quickly consider other routes, taking one to get moving once again. When shopping for a new car, you might think back to a prior experience when negotiating got you a lower price, then employ the same tactics.

While heuristics may be helpful when facing smaller issues, major decisions shouldn't necessarily be made using a shortcut approach. Heuristics also don't guarantee an effective solution, such as when trying to drive around a traffic jam only to find yourself on an equally crowded route.

Trial and Error

A trial-and-error approach to problem-solving involves trying a number of potential solutions to a particular issue, then ruling out those that do not work. If you're not sure whether to buy a shirt in blue or green, for instance, you may try on each before deciding which one to purchase.

This can be a good strategy to use if you have a limited number of solutions available. But if there are many different choices available, narrowing down the possible options using another problem-solving technique can be helpful before attempting trial and error.

In some cases, the solution to a problem can appear as a sudden insight. You are facing an issue in a relationship or your career when, out of nowhere, the solution appears in your mind and you know exactly what to do.

Insight can occur when the problem in front of you is similar to an issue that you've dealt with in the past. Although, you may not recognize what is occurring since the underlying mental processes that lead to insight often happen outside of conscious awareness .

Research indicates that insight is most likely to occur during times when you are alone—such as when going on a walk by yourself, when you're in the shower, or when lying in bed after waking up.

How to Apply Problem-Solving Strategies in Real Life

If you're facing a problem, you can implement one or more of these strategies to find a potential solution. Here's how to use them in real life:

- Create a flow chart . If you have time, you can take advantage of the algorithm approach to problem-solving by sitting down and making a flow chart of each potential solution, its consequences, and what happens next.

- Recall your past experiences . When a problem needs to be solved fairly quickly, heuristics may be a better approach. Think back to when you faced a similar issue, then use your knowledge and experience to choose the best option possible.

- Start trying potential solutions . If your options are limited, start trying them one by one to see which solution is best for achieving your desired goal. If a particular solution doesn't work, move on to the next.

- Take some time alone . Since insight is often achieved when you're alone, carve out time to be by yourself for a while. The answer to your problem may come to you, seemingly out of the blue, if you spend some time away from others.

Obstacles to Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is not a flawless process as there are a number of obstacles that can interfere with our ability to solve a problem quickly and efficiently. These obstacles include:

- Assumptions: When dealing with a problem, people can make assumptions about the constraints and obstacles that prevent certain solutions. Thus, they may not even try some potential options.

- Functional fixedness : This term refers to the tendency to view problems only in their customary manner. Functional fixedness prevents people from fully seeing all of the different options that might be available to find a solution.

- Irrelevant or misleading information: When trying to solve a problem, it's important to distinguish between information that is relevant to the issue and irrelevant data that can lead to faulty solutions. The more complex the problem, the easier it is to focus on misleading or irrelevant information.

- Mental set: A mental set is a tendency to only use solutions that have worked in the past rather than looking for alternative ideas. A mental set can work as a heuristic, making it a useful problem-solving tool. However, mental sets can also lead to inflexibility, making it more difficult to find effective solutions.

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

In the end, if your goal is to become a better problem-solver, it's helpful to remember that this is a process. Thus, if you want to improve your problem-solving skills, following these steps can help lead you to your solution:

- Recognize that a problem exists . If you are facing a problem, there are generally signs. For instance, if you have a mental illness , you may experience excessive fear or sadness, mood changes, and changes in sleeping or eating habits. Recognizing these signs can help you realize that an issue exists.

- Decide to solve the problem . Make a conscious decision to solve the issue at hand. Commit to yourself that you will go through the steps necessary to find a solution.

- Seek to fully understand the issue . Analyze the problem you face, looking at it from all sides. If your problem is relationship-related, for instance, ask yourself how the other person may be interpreting the issue. You might also consider how your actions might be contributing to the situation.

- Research potential options . Using the problem-solving strategies mentioned, research potential solutions. Make a list of options, then consider each one individually. What are some pros and cons of taking the available routes? What would you need to do to make them happen?

- Take action . Select the best solution possible and take action. Action is one of the steps required for change . So, go through the motions needed to resolve the issue.

- Try another option, if needed . If the solution you chose didn't work, don't give up. Either go through the problem-solving process again or simply try another option.

You can find a way to solve your problems as long as you keep working toward this goal—even if the best solution is simply to let go because no other good solution exists.

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

Dunbar K. Problem solving . A Companion to Cognitive Science . 2017. doi:10.1002/9781405164535.ch20

Stewart SL, Celebre A, Hirdes JP, Poss JW. Risk of suicide and self-harm in kids: The development of an algorithm to identify high-risk individuals within the children's mental health system . Child Psychiat Human Develop . 2020;51:913-924. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-00968-9

Rosenbusch H, Soldner F, Evans AM, Zeelenberg M. Supervised machine learning methods in psychology: A practical introduction with annotated R code . Soc Personal Psychol Compass . 2021;15(2):e12579. doi:10.1111/spc3.12579

Mishra S. Decision-making under risk: Integrating perspectives from biology, economics, and psychology . Personal Soc Psychol Rev . 2014;18(3):280-307. doi:10.1177/1088868314530517

Csikszentmihalyi M, Sawyer K. Creative insight: The social dimension of a solitary moment . In: The Systems Model of Creativity . 2015:73-98. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7_7

Chrysikou EG, Motyka K, Nigro C, Yang SI, Thompson-Schill SL. Functional fixedness in creative thinking tasks depends on stimulus modality . Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts . 2016;10(4):425‐435. doi:10.1037/aca0000050

Huang F, Tang S, Hu Z. Unconditional perseveration of the short-term mental set in chunk decomposition . Front Psychol . 2018;9:2568. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02568

National Alliance on Mental Illness. Warning signs and symptoms .

Mayer RE. Thinking, problem solving, cognition, 2nd ed .

Schooler JW, Ohlsson S, Brooks K. Thoughts beyond words: When language overshadows insight. J Experiment Psychol: General . 1993;122:166-183. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.2.166

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 4 min read

The Problem-Solving Process

Looking at the basic problem-solving process to help keep you on the right track.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Problem-solving is an important part of planning and decision-making. The process has much in common with the decision-making process, and in the case of complex decisions, can form part of the process itself.

We face and solve problems every day, in a variety of guises and of differing complexity. Some, such as the resolution of a serious complaint, require a significant amount of time, thought and investigation. Others, such as a printer running out of paper, are so quickly resolved they barely register as a problem at all.

Despite the everyday occurrence of problems, many people lack confidence when it comes to solving them, and as a result may chose to stay with the status quo rather than tackle the issue. Broken down into steps, however, the problem-solving process is very simple. While there are many tools and techniques available to help us solve problems, the outline process remains the same.

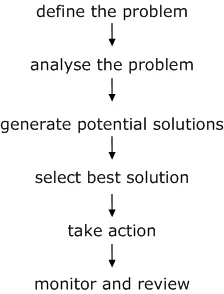

The main stages of problem-solving are outlined below, though not all are required for every problem that needs to be solved.

1. Define the Problem

Clarify the problem before trying to solve it. A common mistake with problem-solving is to react to what the problem appears to be, rather than what it actually is. Write down a simple statement of the problem, and then underline the key words. Be certain there are no hidden assumptions in the key words you have underlined. One way of doing this is to use a synonym to replace the key words. For example, ‘We need to encourage higher productivity ’ might become ‘We need to promote superior output ’ which has a different meaning.

2. Analyze the Problem

Ask yourself, and others, the following questions.

- Where is the problem occurring?

- When is it occurring?

- Why is it happening?

Be careful not to jump to ‘who is causing the problem?’. When stressed and faced with a problem it is all too easy to assign blame. This, however, can cause negative feeling and does not help to solve the problem. As an example, if an employee is underperforming, the root of the problem might lie in a number of areas, such as lack of training, workplace bullying or management style. To assign immediate blame to the employee would not therefore resolve the underlying issue.

Once the answers to the where, when and why have been determined, the following questions should also be asked:

- Where can further information be found?

- Is this information correct, up-to-date and unbiased?

- What does this information mean in terms of the available options?

3. Generate Potential Solutions

When generating potential solutions it can be a good idea to have a mixture of ‘right brain’ and ‘left brain’ thinkers. In other words, some people who think laterally and some who think logically. This provides a balance in terms of generating the widest possible variety of solutions while also being realistic about what can be achieved. There are many tools and techniques which can help produce solutions, including thinking about the problem from a number of different perspectives, and brainstorming, where a team or individual write as many possibilities as they can think of to encourage lateral thinking and generate a broad range of potential solutions.

4. Select Best Solution

When selecting the best solution, consider:

- Is this a long-term solution, or a ‘quick fix’?

- Is the solution achievable in terms of available resources and time?

- Are there any risks associated with the chosen solution?

- Could the solution, in itself, lead to other problems?

This stage in particular demonstrates why problem-solving and decision-making are so closely related.

5. Take Action

In order to implement the chosen solution effectively, consider the following:

- What will the situation look like when the problem is resolved?

- What needs to be done to implement the solution? Are there systems or processes that need to be adjusted?

- What will be the success indicators?

- What are the timescales for the implementation? Does the scale of the problem/implementation require a project plan?

- Who is responsible?

Once the answers to all the above questions are written down, they can form the basis of an action plan.

6. Monitor and Review

One of the most important factors in successful problem-solving is continual observation and feedback. Use the success indicators in the action plan to monitor progress on a regular basis. Is everything as expected? Is everything on schedule? Keep an eye on priorities and timelines to prevent them from slipping.

If the indicators are not being met, or if timescales are slipping, consider what can be done. Was the plan realistic? If so, are sufficient resources being made available? Are these resources targeting the correct part of the plan? Or does the plan need to be amended? Regular review and discussion of the action plan is important so small adjustments can be made on a regular basis to help keep everything on track.

Once all the indicators have been met and the problem has been resolved, consider what steps can now be taken to prevent this type of problem recurring? It may be that the chosen solution already prevents a recurrence, however if an interim or partial solution has been chosen it is important not to lose momentum.

Problems, by their very nature, will not always fit neatly into a structured problem-solving process. This process, therefore, is designed as a framework which can be adapted to individual needs and nature.

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

7 Reasons Why Change Fails

Why Change Can Fail

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Top tips for tackling problem behavior.

Tips to tackle instances of problem behavior effectively

Defeat Procrastination for Good

Saying "goodbye" to procrastination

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

How to manage defensive people.

Lowering Defenses by Building Trust

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

How to Enhance Your Decision-Making Skills as a Leader

- 14 Mar 2024

As a leader, you make countless decisions—from whom to hire and which projects to prioritize to where to make budget cuts.

If you’re a new leader, acclimating to being a decision-maker can be challenging. Luckily, like other vital business skills, you can learn how to make better decisions through education and practice.

Here’s a primer on why decision-making skills are crucial to leadership and six ways to enhance yours.

Access your free e-book today.

Why Are Decision-Making Skills Important?

While decision-making is built into most leaders’ job descriptions, it’s a common pain point. According to a 2023 Oracle study , 85 percent of business leaders report suffering from “decision distress”—regretting, feeling guilty about, or questioning a decision they made in the past year.

When distressed by difficult decisions, it can be easy to succumb to common pitfalls , such as:

- Defaulting to consensus

- Not offering alternatives to your proposed solution

- Mistaking opinions for facts

- Losing sight of purpose

- Truncating debate

By defaulting to the “easy answer” or avoiding working through a decision, you can end up with outcomes that are stagnant at best and disastrous at worst.

Yet, decision-making is a skill you can sharpen in your leadership toolkit. Here are six ways to do so.

6 Ways to Enhance Your Leadership Decision-Making Skills

1. involve your team.

One common pitfall of leadership is thinking you must make every decision yourself. While you may have the final judgment call, enlisting others to work through challenging decisions can be helpful.

Asking for peers’ input can open your mind to new perspectives. For instance, if you ask your direct reports to brainstorm ways to improve your production process’s efficiency, chances are that they’ll have some ideas you didn’t think of.

If a decision is more private—such as whether to promote one employee over another—consider consulting fellow organizational leaders to approach it from multiple angles.

Another reason to involve your team in the decision-making process is to achieve buy-in. Your decision will likely impact each member, whether it’s about a new or reprioritized strategic initiative. By helping decide how to solve the challenge, your employees are more likely to feel a sense of ownership and empowerment during the execution phase.

Related: How to Get Employee Buy-In to Execute Your Strategic Initiatives

2. Understand Your Responsibilities to Stakeholders

When facing a decision, remember your responsibilities to stakeholders. In the online course Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability —offered as a Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB) program elective or individually—Harvard Business School Professor Nien-hê Hsieh outlines your three types of responsibilities as a leader: legal, economic, and ethical .

Hsieh also identifies four stakeholder groups—customers, employees, investors, and society—that you must balance your obligations to when making decisions.

For example, you have the following responsibilities to customers and employees:

- Well-being: What’s ultimately good for the person

- Rights: Entitlement to receive certain treatment

- Duties: A moral obligation to behave in a specific way

- Best practices: Aspirational standards not required by law or cultural norms

“Many of the decisions you face will not have a single right answer,” Hsieh says in the course. “Sometimes, the most viable answer may come with negative effects. In such cases, the decision is not black and white. As a result, many call them ‘gray-area decisions.’”

As a starting point for tackling gray-area decisions, identify your stakeholders and your responsibilities to each.

Related: How to Choose Your CLIMB Electives

3. Consider Value-Based Strategy

If you make decisions that impact your organization’s strategy, consider how to create value. Often, the best decision provides the most value to the most stakeholders.

The online course Business Strategy —one of seven courses comprising CLIMB's New Leaders learning path—presents the value stick as a visual representation of a value-based strategy's components.

By toggling each, you can envision how strategic decisions impact the value you provide to different shareholders.

For instance, if you choose to lower price, customer delight increases. If you lower the cost of goods, you increase value for your firm but decrease it for suppliers.

This kind of framework enables you to consider strategic decisions’ impact and pursue the most favorable outcome.

4. Familiarize Yourself with Financial Statements

Any organizational leadership decision you make is bound to have financial implications. Building your decision-making skills to become familiar and comfortable with your firm’s finances is crucial.

The three financial statements you should know are:

- The balance sheet , which provides a snapshot of your company’s financial health for a given period

- The income statement , which gives an overview of income and expenses during a set period and is useful for comparing metrics over time

- The cash flow statement , which details cash inflows and outflows for a specific period and demonstrates your business’s ability to operate in the short and long term

In addition to gauging your organization’s financial health, learn how to create and adhere to your team or department’s budget to ensure decisions align with resource availability and help your team stay on track toward goals.

By sharpening your finance skills , you can gain confidence and back your decisions with financial information.

5. Leverage Data

Beyond financial information, consider other types of data when making decisions. That data can come in the form of progress toward goals or marketing key performance indicators (KPIs) , such as time spent on your website or number of repeat purchases. Whatever the decision, find metrics that provide insight into it.

For instance, if you need to prioritize your team’s initiatives, you can use existing data about projects’ outcomes and timelines to estimate return on investment .

By leveraging available data, you can support your decisions with facts and forecast their impact.

Related: The Advantages of Data-Driven Decision-Making

6. Learn from Other Leaders

Finally, don’t underestimate the power of learning from other leaders. You can do so by networking within your field or industry and creating a group of peers to bounce ideas off of.

One way to build that group is by taking an online course. Some programs, including CLIMB , have peer learning teams built into them. Each term, you’re sorted into a new team based on your time zone, availability, and gender. Throughout your educational experience, you collaborate with your peers to synthesize learnings and work toward a capstone project—helping you gain new perspectives on how to approach problem-solving and decision-making.

In addition to learning from peers during your program, you can network before and after it. The HBS Online Community is open to all business professionals and a resource where you can give and receive support, connect over topics you care about, and collaborate toward a greater cause.

When searching for courses, prioritize those featuring real-world examples . For instance, HBS Online’s courses feature business leaders explaining situations they’ve encountered in their careers. After learning the details of their dilemmas, you’re prompted to consider how you’d handle them. Afterward, the leaders explain what they did and the insights they gained.

By listening to, connecting with, and learning from other leaders, you can discover new ways to approach your decisions.

Gaining Confidence as a Leader

Taking an online leadership course can help you gain confidence in your decision-making skills. In a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners said they have more confidence making business decisions, and 90 percent report feeling more self-assured at work.

If you want to improve your skills, consider a comprehensive business program like CLIMB .

It features three courses on foundational topics:

- Finance and accounting

And three courses on cutting-edge leadership skills:

- Dynamic Teaming

- Personal Branding

- Leading in the Digital World

Additionally, you select an open elective of your choice from HBS Online’s course catalog .

Through education and practice, you can build your skills and boost your confidence in making winning decisions for your organization.

Are you ready to level up your leadership skills? Explore our yearlong Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB) program , which comprises seven courses for leading in the modern business world. Download the CLIMB brochure to learn about its curriculum, admissions requirements, and benefits.

About the Author

.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:42px;color:#F5F4F3;}@media (max-width: 1120px){.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:12px;}} AI that works. Coming June 5, Asana redefines work management—again. .css-1ixh9fn{display:inline-block;}@media (max-width: 480px){.css-1ixh9fn{display:block;margin-top:12px;}} .css-1uaoevr-heading-6{font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-1uaoevr-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} .css-ora5nu-heading-6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:start;-ms-flex-pack:start;-webkit-justify-content:flex-start;justify-content:flex-start;color:#0D0E10;-webkit-transition:all 0.3s;transition:all 0.3s;position:relative;font-size:16px;line-height:28px;padding:0;font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{border-bottom:0;color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover path{fill:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div{border-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div:before{border-left-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active{border-bottom:0;background-color:#EBE8E8;color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active path{fill:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div{border-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div:before{border-left-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} Get early access .css-1k6cidy{width:11px;height:11px;margin-left:8px;}.css-1k6cidy path{fill:currentColor;}

- Product overview

- All features

- App integrations

CAPABILITIES

- project icon Project management

- Project views

- Custom fields

- Status updates

- goal icon Goals and reporting

- Reporting dashboards

- workflow icon Workflows and automation

- portfolio icon Resource management

- Time tracking

- my-task icon Admin and security

- Admin console

- asana-intelligence icon Asana Intelligence

- list icon Personal

- premium icon Starter

- briefcase icon Advanced

- Goal management

- Organizational planning

- Campaign management

- Creative production

- Marketing strategic planning

- Request tracking

- Resource planning

- Project intake

- View all uses arrow-right icon

- Project plans

- Team goals & objectives

- Team continuity

- Meeting agenda

- View all templates arrow-right icon

- Work management resources Discover best practices, watch webinars, get insights

- What's new Learn about the latest and greatest from Asana

- Customer stories See how the world's best organizations drive work innovation with Asana

- Help Center Get lots of tips, tricks, and advice to get the most from Asana

- Asana Academy Sign up for interactive courses and webinars to learn Asana

- Developers Learn more about building apps on the Asana platform

- Community programs Connect with and learn from Asana customers around the world

- Events Find out about upcoming events near you

- Partners Learn more about our partner programs

- Support Need help? Contact the Asana support team

- Asana for nonprofits Get more information on our nonprofit discount program, and apply.

Featured Reads

- Leadership |

- 7 important steps in the decision makin ...

7 important steps in the decision making process

The decision making process is a method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and making a final choice with the goal of making the best decision possible. In this article, we detail the step-by-step process on how to make a good decision and explain different decision making methodologies.

We make decisions every day. Take the bus to work or call a car? Chocolate or vanilla ice cream? Whole milk or two percent?

There's an entire process that goes into making those tiny decisions, and while these are simple, easy choices, how do we end up making more challenging decisions?

At work, decisions aren't as simple as choosing what kind of milk you want in your latte in the morning. That’s why understanding the decision making process is so important.

What is the decision making process?

The decision making process is the method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and, ultimately, making a final choice.

Decision-making tools for agile businesses

In this ebook, learn how to equip employees to make better decisions—so your business can pivot, adapt, and tackle challenges more effectively than your competition.

The 7 steps of the decision making process

Step 1: identify the decision that needs to be made.

When you're identifying the decision, ask yourself a few questions:

What is the problem that needs to be solved?

What is the goal you plan to achieve by implementing this decision?

How will you measure success?

These questions are all common goal setting techniques that will ultimately help you come up with possible solutions. When the problem is clearly defined, you then have more information to come up with the best decision to solve the problem.

Step 2: Gather relevant information

Gathering information related to the decision being made is an important step to making an informed decision. Does your team have any historical data as it relates to this issue? Has anybody attempted to solve this problem before?

It's also important to look for information outside of your team or company. Effective decision making requires information from many different sources. Find external resources, whether it’s doing market research, working with a consultant, or talking with colleagues at a different company who have relevant experience. Gathering information helps your team identify different solutions to your problem.

Step 3: Identify alternative solutions

This step requires you to look for many different solutions for the problem at hand. Finding more than one possible alternative is important when it comes to business decision-making, because different stakeholders may have different needs depending on their role. For example, if a company is looking for a work management tool, the design team may have different needs than a development team. Choosing only one solution right off the bat might not be the right course of action.

Step 4: Weigh the evidence

This is when you take all of the different solutions you’ve come up with and analyze how they would address your initial problem. Your team begins identifying the pros and cons of each option, and eliminating alternatives from those choices.

There are a few common ways your team can analyze and weigh the evidence of options:

Pros and cons list

SWOT analysis

Decision matrix

Step 5: Choose among the alternatives

The next step is to make your final decision. Consider all of the information you've collected and how this decision may affect each stakeholder.

Sometimes the right decision is not one of the alternatives, but a blend of a few different alternatives. Effective decision-making involves creative problem solving and thinking out of the box, so don't limit you or your teams to clear-cut options.

One of the key values at Asana is to reject false tradeoffs. Choosing just one decision can mean losing benefits in others. If you can, try and find options that go beyond just the alternatives presented.

Step 6: Take action

Once the final decision maker gives the green light, it's time to put the solution into action. Take the time to create an implementation plan so that your team is on the same page for next steps. Then it’s time to put your plan into action and monitor progress to determine whether or not this decision was a good one.

Step 7: Review your decision and its impact (both good and bad)

Once you’ve made a decision, you can monitor the success metrics you outlined in step 1. This is how you determine whether or not this solution meets your team's criteria of success.

Here are a few questions to consider when reviewing your decision:

Did it solve the problem your team identified in step 1?

Did this decision impact your team in a positive or negative way?

Which stakeholders benefited from this decision? Which stakeholders were impacted negatively?

If this solution was not the best alternative, your team might benefit from using an iterative form of project management. This enables your team to quickly adapt to changes, and make the best decisions with the resources they have.

Types of decision making models

While most decision making models revolve around the same seven steps, here are a few different methodologies to help you make a good decision.

Rational decision making models

This type of decision making model is the most common type that you'll see. It's logical and sequential. The seven steps listed above are an example of the rational decision making model.

When your decision has a big impact on your team and you need to maximize outcomes, this is the type of decision making process you should use. It requires you to consider a wide range of viewpoints with little bias so you can make the best decision possible.

Intuitive decision making models

This type of decision making model is dictated not by information or data, but by gut instincts. This form of decision making requires previous experience and pattern recognition to form strong instincts.

This type of decision making is often made by decision makers who have a lot of experience with similar kinds of problems. They have already had proven success with the solution they're looking to implement.

Creative decision making model

The creative decision making model involves collecting information and insights about a problem and coming up with potential ideas for a solution, similar to the rational decision making model.

The difference here is that instead of identifying the pros and cons of each alternative, the decision maker enters a period in which they try not to actively think about the solution at all. The goal is to have their subconscious take over and lead them to the right decision, similar to the intuitive decision making model.

This situation is best used in an iterative process so that teams can test their solutions and adapt as things change.

Track key decisions with a work management tool

Tracking key decisions can be challenging when not documented correctly. Learn more about how a work management tool like Asana can help your team track key decisions, collaborate with teammates, and stay on top of progress all in one place.

Related resources

Grant management: A nonprofit’s guide

Fix these common onboarding challenges to boost productivity

How Asana uses work management for organizational planning

Understanding dependencies in project management

Problem Solving And Decision Making: 10 Hacks That Managers Love

Understanding problem solving & decision making, why are problem solving and decision making skills essential in the workplace, five techniques for effective problem solving, five techniques for effective decision making, frequently asked questions.

Other Related Blogs

- Improved efficiency and productivity: Employees with strong problem solving and decision making skills are better equipped to identify and solve issues that may arise in their work. This leads to improved efficiency and productivity as they can complete their work more timely and effectively.

- Improved customer satisfaction: Problem solving and decision making skills also help employees address any concerns or issues customers may have. This leads to enhanced customer satisfaction as customers feel their needs are being addressed and their problems are resolved.

- Effective teamwork: When working in teams, problem solving and decision making skills are essential for effective collaboration . Groups that can effectively identify and solve problems together are more likely to successfully achieve their goals.

- Innovation: Effective problem-solving and decision-making skills are also crucial for driving innovation in the workplace. Employees who think creatively and develop new solutions to problems are more likely to develop innovative ideas to move the business forward.

- Risk management: Problem solving and decision making skills are also crucial for managing risk in the workplace. By identifying potential risks and developing strategies to mitigate them, employees can help minimize the negative impact of risks on the business.

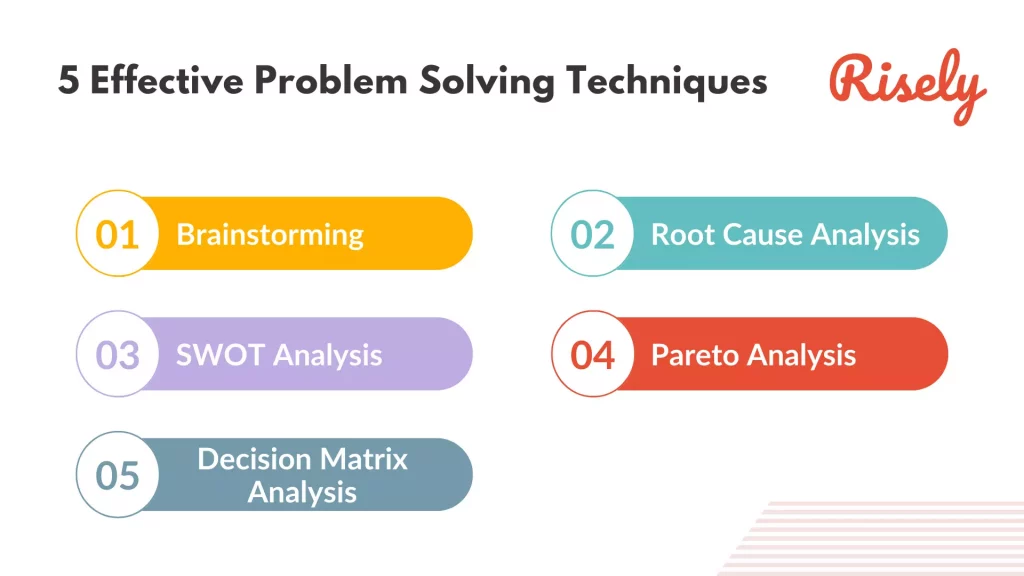

- Brainstorming: Brainstorming is a technique for generating creative ideas and solutions to problems. In a brainstorming session, a group of people share their thoughts and build on each other’s suggestions. The goal is to generate a large number of ideas in a short amount of time. For example, a team of engineers could use brainstorming to develop new ideas for improving the efficiency of a manufacturing process.

- Root Cause Analysis: Root cause analysis is a technique for identifying the underlying cause of a problem. It involves asking “why” questions to uncover the root cause of the problem. Once the root cause is identified, steps can be taken to address it. For example, a hospital could use root cause analysis to investigate why patient falls occur and identify the root cause, such as inadequate staffing or poor lighting.

- SWOT Analysis: SWOT analysis is a technique for evaluating the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to a problem or situation. It involves assessing internal and external factors that could impact the problem and identifying ways to leverage strengths and opportunities while minimizing weaknesses and threats. For example, a small business could use SWOT analysis to evaluate its market position and identify opportunities to expand its product line or improve its marketing.

- Pareto Analysis: Pareto analysis is a technique for identifying the most critical problems to address. It involves ranking problems by impact and frequency and first focusing on the most significant issues. For example, a software development team could use Pareto analysis to prioritize bugs and issues to fix based on their impact on the user experience.

- Decision Matrix Analysis: Decision matrix analysis evaluates alternatives and selects the best course of action. It involves creating a matrix to compare options based on criteria and weighting factors and selecting the option with the highest score. For example, a manager could use decision matrix analysis to evaluate different software vendors based on criteria such as price, features, and support and select the vendor with the best overall score.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Cost-benefit analysis is a technique for evaluating the costs and benefits of different options. It involves comparing each option’s expected costs and benefits and selecting the one with the highest net benefit. For example, a company could use cost-benefit analysis to evaluate a new product line’s potential return on investment.

- Decision Trees: Decision trees are a visual representation of the decision-making process. They involve mapping out different options and their potential outcomes and probabilities. This helps to identify the best course of action based on the likelihood of different outcomes. For example, a farmer could use a decision tree to choose crops to plant based on the expected weather patterns.

- SWOT Analysis: SWOT analysis can also be used for decision making. By identifying the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of different options, a decision maker can evaluate each option’s potential risks and benefits. For example, a business owner could use SWOT analysis to assess the potential risks and benefits of expanding into a new market.

- Pros and Cons Analysis: Pros and cons analysis lists the advantages and disadvantages of different options. It involves weighing the pros and cons of each option to determine the best course of action. For example, an individual could use a pros and cons analysis to decide whether to take a job offer.

- Six Thinking Hats: The six thinking hats technique is a way to think about a problem from different perspectives. It involves using six different “hats” to consider various aspects of the decision. The hats include white (facts and figures), red (emotions and feelings), black (risks and drawbacks), yellow (benefits and opportunities), green (creativity and new ideas), and blue (overview and control). For example, a team could use the six thinking hats technique to evaluate different options for a marketing campaign.

Aastha Bensla

Aastha, a passionate industrial psychologist, writer, and counselor, brings her unique expertise to Risely. With specialized knowledge in industrial psychology, Aastha offers a fresh perspective on personal and professional development. Her broad experience as an industrial psychologist enables her to accurately understand and solve problems for managers and leaders with an empathetic approach.

How strong are your decision making skills?

Find out now with the help of Risely’s free assessment for leaders and team managers.

How are problem solving and decision making related?

What is a good example of decision-making, what are the steps in problem-solving and decision-making.

Best Decision Coaches To Guide You Toward Great Choices

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, 9 tips to master the art of delegation for managers, how to develop the 8 conceptual skills every manager needs.

12 SMART Goals Examples for Better Decision Making

Making decisions can be arduous, especially when faced with many options. But setting SMART goals could make this process more manageable. The SMART method provides structure and organization, enabling you to focus on the most critical tasks.

This post will discuss some examples of SMART goals for decision making. By establishing these goals, you’ll make better-informed decisions that lead to success.

Table of Contents

What is a SMART Goal?

The SMART system is your best friend when setting effective goals. If you didn’t already know, SMART stands for specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based.

Need more clarity? SMART goals are:

- Specific: We all have aspirations of success, but without a plan, we’re likely to get nowhere. When making decisions that lead us closer to our goals, the more detailed they are, the higher our chances of achieving them.

- Measurable: Having measurable goals is critical for success; you can accurately assess your progress with them. Otherwise, you may be spinning your wheels instead of achieving your desired outcomes.

- Attainable: Make sure you are being realistic when setting goals. Establishing unrealistic expectations may lead to unnecessary stress and disappointment. Goal-setters need to create achievable benchmarks for themselves that can be met promptly.

- Relevant: Developing relevant goals is the cornerstone of success in any field. It will help you stay motivated and laser-focused on reaching your desired results.

- Time-based: Setting a specific timeline will ensure you can focus on your goals and move forward steadily. You’ll be able to stay accountable on the path to better decision making.

Decision making is an essential skill everyone needs to attain their goals and succeed. Fulfilling these 5 SMART components will help you do everything necessary to make sound judgments in your professional and personal lives.

Here are 12 examples of SMART goals for effective decision making:

1. Don’t Dwell on Mistakes

“Rather than dwelling on mistakes made in the past, I will focus on finding solutions and learning from those experiences by the end of three months. This will help me stay focused on making the best decisions possible to move forward.”

Specific: The aim is to learn from mistakes rather than dwelling on them.

Measurable: Keep track of how often you find yourself dwelling on past mistakes and compare it to the number of times you focus on solutions.

Attainable: Developing an attitude that focuses on solutions is an achievable goal within the given timeline.

Relevant: Learning from mistakes is key to making better decisions in the future.

Time-based: You want to achieve this goal by the end of three months.

2. Use a Decision Journal

“To improve my decision-making process, I’ll create and use a journal to track my decisions for 8 months. I want to determine why I made that choice and consider any implications it might have in the future.”

Specific: The goal is clearly defined in terms of what needs to be done and when.

Measurable: Track the number of decisions you make and review the entries in your journal.

Attainable: Creating and using a journal can be done within the timeline given.

Relevant: This goal relates to the decision-making process and can allow you to gain greater insight into your choices.

Time-based: There is an 8-month deadline for goal achievement.

3. Take Time Out

“I will take 15 minutes to assess any decision before committing to it for the four months ahead. This allows the opportunity to evaluate an action’s potential outcomes and implications before following through.”

Specific: This goal is explicit as it guides you to take 15 minutes before making any decisions.

Measurable: The person should measure the time taken to assess their decisions.

Attainable: Fifteen minutes is a feasible time frame for assessing the potential implications of an action.

Relevant: This is pertinent as it will help the person better understand their decisions and make sound choices.

Time-based: The goal should be achieved within four months.

4. Get Feedback From Others

“I will expand my network of contacts and resources by talking with at least three people outside my immediate department for advice on my major decisions within three months. I want to get multiple perspectives and ideas for critical matters.”

Specific: The statement indicates who the person should be talking to and how often they should do it.

Measurable: Count how many conversations have taken place.

Attainable: It’s relatively easy to reach out and start a conversation with someone, so this goal is possible.

Relevant: Getting diverse perspectives when making decisions can be beneficial and help to ensure better outcomes.

Time-based: Three months is the time frame for this particular target.

5. Consider the Consequences

“I’ll take a moment to consider the potential consequences of my decisions before committing by the end of two months. This will benefit everyone involved and not create any negative repercussions.”

Specific: This goal outlines a particular behavior that needs to be changed.

Measurable: Track how often you have taken the time to consider potential consequences.

Attainable: Anybody can accomplish this with enough focus and effort.

Relevant: This is relevant to decision making because it teaches you to think before acting.

Time-based: The goal should be achieved by the end of two months.

6. Narrow Your Options

“I will narrow down my options during the decision-making process by listing the pros and cons of each option within two weeks. I want to avoid being overwhelmed by too many choices and focus on the most pertinent information.”

Specific: The goal states what needs to be done and the timeline for completion.

Measurable: You can determine how much time it takes to narrow down your options.

Attainable: This is a realistic goal because it is possible to limit the number of choices you have to make.

Relevant: Narrowing down options is essential for making informed decisions quickly and efficiently.

Time-based: There is a two-week deadline for accomplishing this goal.

7. Learn to Say No

“I’ll practice saying no to non-essential tasks and requests that don’t align with my objectives. I will also review the criteria for making decisions so that I’m only saying yes to important and necessary tasks.”

Specific: You will practice saying no to requests that aren’t in line with your objectives.

Measurable: Individuals can measure their success by the number of times they refuse tasks and requests.

Attainable: Saying no is a realistic goal to set and complete.

Relevant: This goal relates to decision making as it helps an individual prioritize and focus on essential tasks.

Time-based: This is a continual goal the person should aim to do daily.

8. Control Your Emotions

“I will work on controlling my emotions by taking 5-minute breaks when needed and actively recognizing when I become overwhelmed. By the end of four months, I will be able to remain calm and professional during stressful life situations.”

Specific: The aim is to take 5-minute breaks when needed and actively recognize when emotions become overwhelming.

Measurable: Assess how effectively you can control your emotions during stressful situations.

Attainable: This goal is achievable with regular breaks and practice.

Relevant: Being able to control emotions is vital for decision making, so this goal is highly relevant.

Time-based: You should anticipate goal achievement after four months.

9. Learn From the Past

“I’ll actively review past decisions and outcomes from current operations to identify patterns that could be useful for future decision making. By the end of 6 months, I will have developed a process to capture key learnings from the past and use them in future planning.”

Specific: This goal focuses on reviewing past decisions and outcomes to identify patterns that can be used in the future.

Measurable: You could measure the number of decisions and outcomes you review each month.

Attainable: Reviewing past decisions is something that can be done regularly.

Relevant: Gathering information from the past can help you make smarter decisions in the future.

Time-based: There is an end date of 6 months for the goal.

10. Ask Good Questions

“I will become more inquisitive and analytical by asking at least one meaningful question in each meeting, presentation, or class I attend. For the next 5 months, I’ll try to make a habit of questioning rash assumptions and developing better solutions.”

Specific: You want to make it a habit of asking meaningful questions.

Measurable: Track the number of questions you ask in each meeting, presentation, or class.

Attainable: Assuming that you make the necessary commitment , this goal is achievable.

Relevant: This relates to your primary objective of becoming more inquisitive and analytical.

Time-based: You should expect to see success after 5 months.

11. Do Not Multitask

“To better focus my attention on individual tasks and increase productivity, I will practice not multitasking for the following three months. I’ll focus on one task at a time instead of juggling too many things at once.”

Specific: The SMART statement is well-defined. The individual will practice not multitasking for three months.

Measurable: They can focus on one task at a time and track progress.

Attainable: This realistic goal is achievable with the right amount of dedication.

Relevant: Multitasking may increase the risk of making mistakes , which must be avoided during decision making.

Time-based: The person has three months to reach this certain goal.

12. Avoid Overanalyzing

“I will avoid overanalyzing or endlessly studying data over the course of 5 months. I’ll strive to make wise decisions swiftly, with the understanding that I can adjust my course of action if needed in response to new information.”

Specific: This goal describes what needs to be done (avoid overanalyzing) and the time frame (5 months).

Measurable: You could count the number of decisions you make within a certain period.

Attainable: This goal is doable if you practice making decisions without overanalyzing the data.

Relevant: Making wise and timely decisions is essential to almost everyone.

Time-based: Goal completion is expected within 5 months.

Final Thoughts

The SMART framework is a fantastic tool for making better decisions and reaching success. They are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-based, which makes them easy to understand and follow.

SMART goals can also bring clarity to a decision by focusing on the outcome you want to achieve. Whether setting personal or professional objectives, applying SMART will help you reach your goals faster and more effectively.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

7 Strategies for Better Group Decision-Making

- Torben Emmerling

- Duncan Rooders

What we’ve learned from behavioral science.

There are upsides and downsides to making decisions in a group. The main risks include falling into groupthink or other biases that will distort the process and the ultimate outcome. But bringing more minds together to solve a problem has its advantages. To make use of those upsides and increase the chances your team will land on a successful solution, the authors recommend using seven strategies, which have been backed by behavioral science research: Keep the group small, especially when you need to make an important decision. Bring a diverse group together. Appoint a devil’s advocate. Collect opinions independently. Provide a safe space to speak up. Don’t over-rely on experts. And share collective responsibility for the outcome.

When you have a tough business problem to solve, you likely bring it to a group. After all, more minds are better than one, right? Not necessarily. Larger pools of knowledge are by no means a guarantee of better outcomes. Because of an over-reliance on hierarchy, an instinct to prevent dissent, and a desire to preserve harmony, many groups fall into groupthink .

- Torben Emmerling is the founder and managing partner of Affective Advisory and the author of the D.R.I.V.E.® framework for behavioral insights in strategy and public policy. He is a founding member and nonexecutive director on the board of the Global Association of Applied Behavioural Scientists ( GAABS ) and a seasoned lecturer, keynote speaker, and author in behavioral science and applied consumer psychology.