- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Being Black In America

Being black in america: 'we have a place in this world too'.

Maquita Peters

In response to several high-profile deaths of African Americans in recent months, some black people are saying that enough is enough. Clockwise from top left: Michael Martin, Tunisian Burks, Sam Tyler, Alexander Pittman, the Rev. Carol Thomas Cissel, Brandon Winston, Donna Ghanney and Mark Turner. NPR hide caption

In response to several high-profile deaths of African Americans in recent months, some black people are saying that enough is enough. Clockwise from top left: Michael Martin, Tunisian Burks, Sam Tyler, Alexander Pittman, the Rev. Carol Thomas Cissel, Brandon Winston, Donna Ghanney and Mark Turner.

Editor's note: NPR will be continuing this conversation about Being Black in America online and on air.

As protests continue around the country against systemic racism and police brutality, black Americans describe fear, anger and a weariness about tragic killings that are becoming all too familiar.

"I feel helpless. Utterly helpless," said Jason Ellington of Union, N.J. "Black people for generations have been reminding the world that we as a people matter — through protests, sit-ins, boycotts and the like. We tried to be peaceful in our attempts. But as white supremacy reminds us, their importance — their relevance — comes with a healthy dose of violence and utter disrespect for people of color like me."

County Officials Rule George Floyd Death Was A Homicide

For more than a week, tens of thousands of people have thronged cities nationwide, staging protests. The demonstrations were triggered by the death of 46-year-old George Floyd while in police custody in Minneapolis on Memorial Day. Floyd, a black man, died while a white police officer knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes.

The protests also reflect outrage over the shooting death of 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery while he was jogging through a Glynn County, Ga., neighborhood in February. Three white men were arrested in connection with his death, which was caught on video. Tensions also have flared in response to the death of Breonna Taylor , a 26-year-old black woman who was shot and killed in her apartment by police in Louisville, Ky., in March.

Jason Ellington, a 41-year-old marketing professional, says he is angry — and also feels helpless. Jason Ellington hide caption

Some protests have become violent , marred by looting, clashes with police and countless arrests, and several state officials have enacted curfews. This amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen a disproportionate number of deaths among African Americans, exacerbating challenges in these uncertain times for a people often racially profiled and long oppressed.

Cities are burning. Not just with fires but with anger.

Black people say they are frustrated. Fearful. Fatigued.

"I'm not going to lie — I am angry," said Ellington, a 41-year-old marketing professional who has a 10-year-old daughter. "As a black man in America, it is already hard enough that we have to fight within ourselves to become a better person, but there are countless forces working outside of ourselves that are also working against us and have been for generations."

Ellington is one of nearly 200 people who shared with NPR what it's like to be black in America right now.

Nicholas Gibbs of Spring, Texas, is particularly concerned about his two toddler sons growing up.

"To be black in America, you have to endure white supremacy. You have to fear the police. To be American, you have the luxury of saying, 'They should have complied!' To be black in America, you have to hope someone recorded your compliance because you may no longer be around to defend yourself," the 39-year-old said.

Alexander Pittman, who lives in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., said there's a huge amount of anxiety on a daily basis regarding any contact with police even if you are doing nothing wrong or illegal, because you know it could escalate out of control.

"Being a black man in America, you know you live by a different set of rules," Pittman said.

He recounted what happened to him a few years ago when he'd just moved to Hollywood, Fla., and went out one evening to walk his dog, Marley.

Code Switch

Ta-nehisi coates looks at the physical toll of being black in america.

"I was confronted by several Hollywood police officers. I was also roughed up and detained before being let go," the 32-year-old said, adding that no charges were filed against him.

As dad to a 4-year-old and a public school teacher, Pittman said he tries to have real conversations with his students and son about the role that race has played in the U.S. historically — and today.

"It's hard, because on one hand I don't believe in riots, looting and violence, but on the other hand, when is enough, enough? We need real, tangible policing reform on a national level, and that has largely been ignored."

The Rev. Carol Thomas Cissel says being black in America is about playing her part to help alleviate racial inequality. Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Centre County hide caption

Many black mothers in America expressed fear for the boys and men in their lives.

"I'm weary of living in a constant state of anxiety and fear because I have black and brown men in my life: my son, brothers, friends, grandson, son-in-law and father. I'm bone tired of existing in a system that tells me every damn day that me and my people do not matter," said the Rev. Carol Thomas Cissel of State College, Pa.

A mother, minister and grandmother, Cissel said her "DNA will continue to scream in agony" because black men and boys are not safe in America.

"I will try to hold the pain and soul wounds of my people. I will mourn because I know wishes, words or rituals cannot keep my son and grandson alive."

Jami Vassar, a 34-year-old fourth-generation military veteran from Aberdeen, N.C., can relate. As a mom of two teenage sons, she worries about their well-being and tries to keep them close.

"They are my gentle giants, but they are big black boys, and I have to remind them that the world doesn't see them as kids and there is real danger just for existing," she said.

Vassar said although she comes from a family of proud Americans who boast a long line of service to the country, the world sees them as black first. Just last week while driving with her younger son, she said he expressed fears about getting pulled over. He'll be getting his driver's license soon.

"I had to tell him I'm afraid when I get pulled over. My family has served in every war since War World I. They served before African Americans could vote, and we continue to serve even though we are not always seen as equals. It hurts," she said.

Arbery Shooting Sparks Racism, Corruption Questions About Georgia County

Another mom, Edith Jennings of Holyoke, Mass., said she too worries about her two adult sons. Last week on an unusually balmy spring day in New England, while driving through a small area with one of them, they noticed two young white men standing by their bicycles, laughing and talking to each other.

"My son, who is 28 years old and now a new father of his own son, said, 'It must be nice to wake up in the morning and feel safe, to not be afraid to go out and do what you have to do for the day, to hang out with your friends, not be afraid of the police. I wonder what that is like.' When I heard that, I was almost in tears," Jennings said.

Having grown up in the 1960s and '70s and remembering a story her mom told about watching the Ku Klux Klan burning crosses in her yard, Jennings said she never expected to have to deal with such racial issues when she had her own kids.

"Now here we are in the 21st century and I have a 2-month-old grandson, and I wonder if he, as a young black man, will survive in America. I feel like black men and women are an endangered species here in America. That's what's it like being black in America now!"

Protesters in Miami hold signs during a rally Sunday in response to the recent death of George Floyd. Ricardo Arduengo/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Protesters in Miami hold signs during a rally Sunday in response to the recent death of George Floyd.

Donna Ghanney of Brooklyn, N.Y., grew up during the same era as Jennings. She recalls white men standing on the corner and calling out the N-word as she passed by.

"All you had to be was a person of color to feel the hatred when you went near a white man. A feeling of fear, oppression, being disliked, having no rights, and the fear of being killed with a lie trailing behind the death," she said.

Other mothers shared their concern that nothing will change.

"People are tired of empty protests that fail to deliver change. Some care more about dogs than the lives of black and brown people in America," said Nicole Green of Melbourne, Fla., who said her childhood memories are filled with relatives being pulled over or being harassed by police.

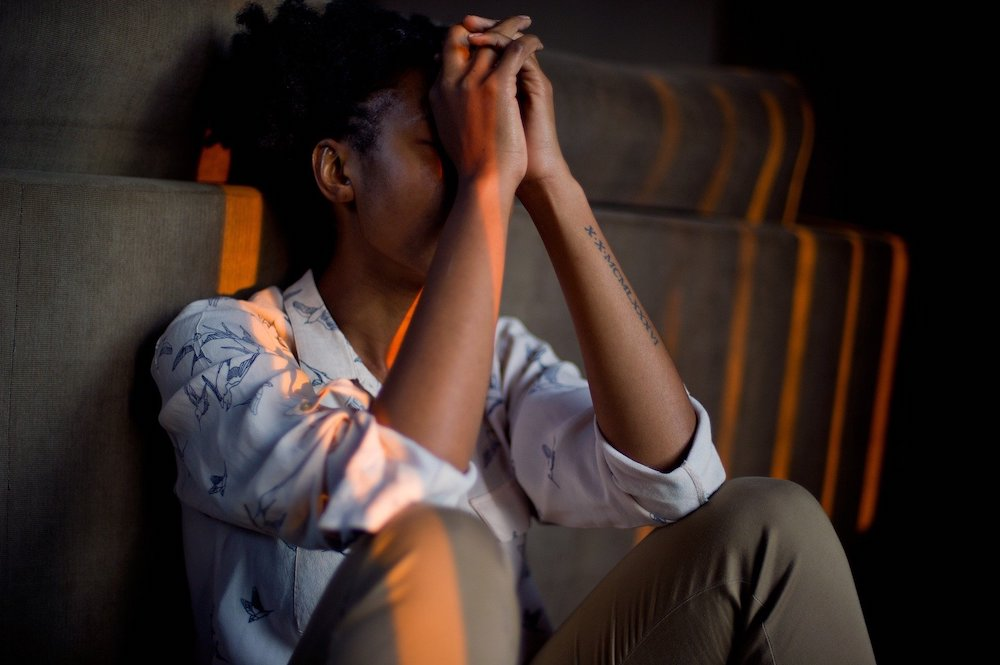

Free Browning said the situation in the country is disheartening, particularly for a person who suffers from anxiety and depression.

"As a single mom of three and an Atlanta native, I'm angry, horrified, scared, hurt and uneasy. While I don't condone the destruction of many of the businesses here in Atlanta, I have lost my concern to care."

7 Shot At Louisville Protest Calling For Justice For Breonna Taylor

Others said being black in America can feel like being at war.

"I recently purchased two guns and plan on purchasing more," said 62-year-old Bruce Tomlin of Albuquerque, N.M.

Tomlin said he dealt with a lot of racial tension living for more than three decades in Texas. While he says Albuquerque is different, he travels often out of state as a truck driver. After watching the video of Arbery being shot, he said he wants to be able to defend himself.

"I feel every person of color in America should be armed. I feel that the current administration and the 1% are guiding us into a civil war," he said. "I also feel that it is open season on black males in particular. People of color are being eliminated by police and disease. I plan on fighting until the end."

Michael Martin of Chicago said he feels like there's nothing he can do to protect himself and his family.

"We can't go jogging without worrying about being lynched; we can't go bird-watching without having the police called on us. Our children can't go outside and play without us worrying about them being gunned down and labeled 'suspects.' We can't sleep in our own beds without being executed," he said. "The same rights and protections that our white peers are afforded are not afforded to us. We can't arm ourselves without being labeled thugs and shot."

Some people feel conflicted. Helpless. Ambivalent. Mentally drained.

"Last night I cried to my partner," said Glenn Smith of Brooklyn, N.Y. "I cried because I realized how proud I am to be an American, a New Yorker and a Brooklynite. I cried because in those feelings of pride, I'm faced with feelings of contradiction. Why are cops brutally killing people that look like me?"

An Avid Birder Talks About His Conflict In Central Park That Went Viral

Cheyenne Amaya of Woodbridge, Va., said police-involved deaths no longer surprise her.

"They are so a part of my normal life now that I feel a bit desensitized. I still have to continue to try to put a brave face on while feeling angry, hurt, sad, anxious and tired. It's been like this my whole life," she said. "We were taught at a young age to make ourselves appear less threatening and to always keep our hands up. It's tiring trying to live your life while constantly in fear of someone shooting you down or accusing you of something you didn't do."

Waddell Hamer of Indianapolis, who recently graduated with his master's degree in social work, said: "The mental health of blacks during this time is fragile. I know mine is. COVID, racism and poverty to name a few. How do I tend to the mental health of blacks during this time?"

Still, amid these myriad emotions expressed by black Americans, some spoke of hope.

Cissel, the minister from Pennsylvania, said that for "all my people to be safe, the racist fabric of this country must be ripped to shreds and rewoven."

She's ready to do her part.

"I will light a candle, hope it blossoms into a steady flame of peace and say these words aloud: 'We are included. We belong. We are here.' For, just like you — entitled by birthright, we have a place in this world too."

NPR would like to hear about your reaction to these incidents and your personal experience as a black person in America. Please share your story here or in the form below, and a reporter might contact you.

- George Floyd protests

- black people

- black lives matter

- African Americans

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Growing up black in America: here's my story of everyday racism

As a middle-class, light-skinned black man I am ‘better’ by American standards but there is no amount of assimilation that can shield you from racism in the US

I am a black man who has grown up in the United States. I know what it is like to feel the sting of discrimination. As a middle-class, light-skinned black man I also know that many others suffered (and continue to suffer) a lot worse than me. I grew up around a lot of white people. In elementary school, I remember being told that I was one of the “good ones” – not like the “bad ones” I was meant to understand; I was different.

I remember the way this kind of backhanded compliment stung me, but it took me a long time to understand why it hurt. In truth, though, the comment rings true. I am “good” by America’s standards, or at least “better”: my skin is light, most of the time I dress like a middle-class professional and my manner of speech betrays a large degree of assimilation in the white American mainstream (for example, I use phrases like “manner of speech”).

But as many others have learned, there is no amount of assimilation that can shield you from racism in this country. Throughout my life, something – the kink of my hair or my “attitude” – would mark me as inferior, worthy of ridicule, humiliation or ostracism. In elementary school I got the distinct impression that teachers didn’t like me. I got in trouble a lot, and one teacher actually wrote on my report card that I was “amoral”. In third grade, I had my first black teacher and the whole dynamic changed. Mrs Brooks decided it was OK if I squirmed in my chair. She taught us about discrimination and injustice and taught us to recite and interpret poetry from the black arts movement. (Thank you, Mrs Brooks!)

As I got older, I observed that my mother saw racism around every corner. She assumed that I would be the object of discrimination in school and maintained an intense, vigilant determination to protect me from it. She monitored everything about my treatment in school, ready to leap at the slightest slight. Sometimes I thought she went too far. I wasn’t chosen to give a speech to my middle school’s assembly, and so she inquired as to why I wasn’t chosen, and she insisted that I be given a shot. So, thanks to my mother raising a fuss I had to give a speech to my entire middle school. (Thank you, mom!)

In high school I started wondering, as teenagers do, how people go about finding romantic partners. From what I could tell in movies and television shows – my principal sources of information – you had to be a rich and white to be worthy of love. I was neither, so I was worried. Like many young black people, I internalized the idea that I would have be twice as good to get half as much respect. Much to my dismay, my blackness seemed to be the salient thing about me. One of my classmates had a gift for inventing creative ways to make fun of my kinky hair, and he got enough people laughing to send me home in tears for a good part of my freshman and sophomore years of high school.

One year, one of the few black students at my high school found a noose hanging in his locker one day. The culprit – a white student – was quickly discovered, and all he had to do to get out of trouble was issue a lame apology. I thought his punishment should have been more severe. I convinced my best friend to wear black armbands in school to protest. This act earned me no greater respect, and actually greater ridicule. Several of our teachers thought it was funny and even prompted our classmates to laugh at our expense: “Look at Jones,” one teacher said, “starting a revolution.” (Thank you, Mr I forget-your-name!)

Looking back, I realize that, apart from my black armband episode, my survival strategy was to make myself as non-threatening as possible. I became so well-practiced in the art of not offending racist white people that I ceased to become outraged by them, at least when they affected me directly. I knew how to enter a store, to make eye contact with someone who worked there, to smile and say hello as if to say: “Don’t worry, I’m not trying to steal anything.” Somehow – I suppose from being followed in stores frequently – I learned not to carry books into a bookstore, not to walk through a store with bags that were not sealed or zippered shut, and so on.

Now that I’m older, with a graying beard and significantly less hair on my head, I probably don’t need to keep up this routine, as I’m probably the cause of less suspicion, but the habit has stayed with me. While shopping, I still assume that I am suspect. I am a middle-aged man, and yet I still habitually enter the grocery store, the book store, the clothing store, etc looking for the first opportunity to reassure the employees that I’m not going to be a problem.

At some point, I figured out (at least, intellectually) that it doesn’t matter how “good” I am – my fate is bound up with all of those who are “bad”. There was a moment in my adulthood when I decided that the present order is intolerable and a new world is both possible and necessary. In the grand scheme of things, my experiences of everyday racism are not that important. I am neither the most privileged nor most oppressed. I know that there are people of all stripes who are trying to survive on this planet with fewer resources than I have.

I am consistently inspired by the words of the early 20th-century socialist Eugene V Debs (a white guy!) who famously told a judge, after being convicted of sedition: “Your Honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

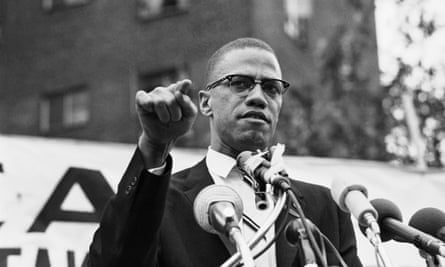

I am also inspired by the words of Malcolm X, who summarized the goals of the black movement as: “Human rights! Respect as human beings! That’s what American black masses want. That’s the true problem. The black masses want to not be shrunk from as though they are plague-ridden. They want not to be walled up in slums, in the ghettoes, like animals. They want to live in an open, free society where they can walk with their heads up, like men and women!”

Eugene Debs and Malcolm X are very different men from very different social contexts, and yet in my mind they are congruent.

Growing up in this country, my experience with everyday racism, although unique to my class and complexion, has nevertheless given me some access to the “second sight” that is a crucial part of black people’s gift to the world. To paraphrase WEB Du Bois, I believe that black history has a message for humanity. That message, to paraphrase activist Alicia Garza, is that the kind of equality black people need to be free is the kind of equality that will make everyone else free.

I write this as a black person who also knows the white American world. There is ignorance and prejudice there, but there is also pain, suffering and struggle. I am grateful to my parents and teachers who helped me to notice and name racism and discrimination. They have helped me to understand my personal experience and, just as importantly, to see beyond it. I have become convinced that black liberation is bound up with true human liberation. Look at me, with any luck, starting a revolution.

Brian Jones is an educator and activist in New York. He is the associate director of education at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

- Everyday racism in America

- Race in education

Most viewed

Our Favorite Essays by Black Writers About Race and Identity

Books & Culture

A personal and critical lens to blackness in america from our archives.

It’s fitting that two of the first three essays in this roundup are centered on examining the Black American experience as one of horror. In a year when radical right-wing activists are truly leaning in, we’ve already seen record numbers of anti-LGBTQ legislation, the very real possibility of the end of Roe v. Wade, and more fervent redlining measures to keep Black people (and other marginalized communities) from voting. Gun violence is at an all time high, in particular mass shootings.

Since the success of Jordan Peele’s runaway hit film Get Out , there has been a steady rise in films depicting the Black American experience for the fraught, nuanced, dangerous life that it can be. This narrative isn’t entirely new, but this is the first time these films have gained critical acclaim and commercial attention. The reason is simple. Whatever the cause—social media, an increasingly diverse population—America can’t run from itself anymore. Our entertainment is finally asking the question that Black people have been asking for generations: In America, who is the real boogeyman?

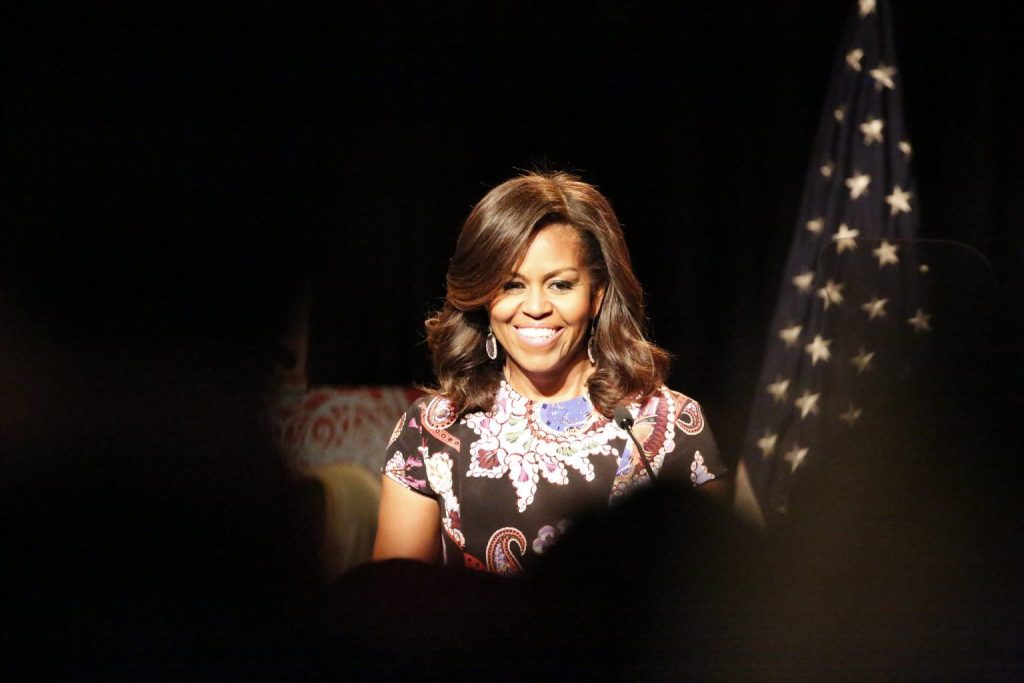

Naturally, the discourse and critical analyses must follow suit. But it doesn’t stop there: the essays on this list span far and wide when it comes to subject matter, critical lens, and personal narrative. There are essays about Black friendship, the radical nature of Black people taking rest, and the affirmation of Black women writing for themselves, telling their own stories. Icons like Michelle Obama, Toni Morrison, and Gayle Jones get a deep dive, and we learn that we should always have been listening to Octavia Butler. This Juneteenth, I hope you’re taking a moment to reflect, on America’s troubled legacy, and to celebrate the ways that Black people continue to thrive.

Modern Horror Is the Perfect Genre for Capturing the Black Experience

Cree Myles writes about the contemporary Black creators rewriting the horror genre and growing the canon:

“Racism is a horror and should be explored as such. White folks have made it clear that they don’t think that’s true. Someone else needs to tell the story.”

Modern Narratives of Black Love and Friendship Are Centering Iconic Trios

Darise Jeanbaptiste writes about how Insecure and Nobody’s Magic illustrate the intricacy of evolving Black relationships:

“The power of the triptych is that it offers three experiences in addition to the fourth, which emerges when all three are viewed or read together.”

I Was Surrounded by “Final Girls” in School, Knowing I’d Never Be One

Whitney Washington writes that the erasure of Black women in slasher films has larger implications about race in America:

“Long before the realities of American life, it was slasher movies that taught me how invisible, ignored, and ultimately expendable Black women are. There was no list of rules long enough to keep me safe from the insidiousness of white supremacy… More than anything, slasher movies showed me that my role was to always be a supporting character, risking my life to be the voice of reason ensuring that the white girl makes it to the finish line.”

“Palmares” Is An Example of What Grows When Black Women Choose Silence

Deesha Philyaw, author of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies , writes that Gayl Jones’ decades-long absence from public life illuminates the power of restorative quiet:

“These women’s silences should not be interpreted as a lack of understanding or awareness, but rather as an abundance of both, most especially the knowledge of what to keep close to the vest, and the implications for failing to do so. They know better than to explain themselves, their powers and their origins, their beliefs and reasons, their magic. These women are silent not because they don’t know anything. They are silent because they know better.”

Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” Showed Me How Race and Gender Are Intertwined

For the 50th anniversary of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye , Koritha Mitchell writes how the novel taught her that being a Black woman is more than just Blackness or womanhood:

“I didn’t have the gift of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of ‘intersectionality,’ but The Bluest Eye revealed how, in my presence, racism and sexism would always collide to produce negative experiences that others could dodge. It was not simply being Black or being dark-skinned that mattered; it was being those things while also being female.”

The Delicate Balancing Act of Black Women’s Memoir

Koritha Mitchell writes about how Michelle Obama’s Becoming illustrates larger tensions for Black women writing about themselves:

“In other words, when Black women remain enigmas while seeming to share so much, they create proxies at a distance from their psychic and spiritual realities because they are so rarely safe in public. Despite the release of her memoir, audiences will never be privy to who Michelle Obama actually knows herself to be, and that is more than appropriate.”

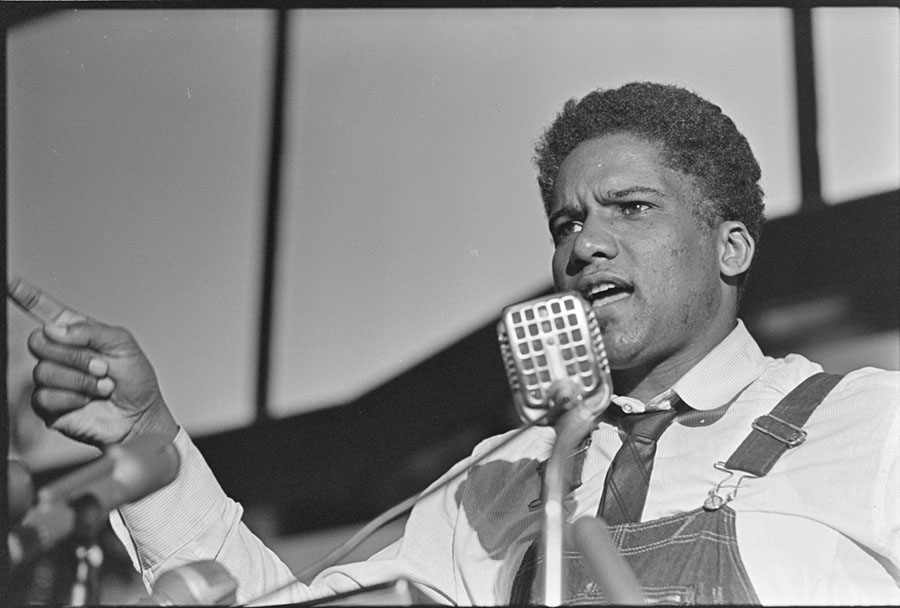

50 Years Later, the Demands of “The Black Manifesto” Are Still Unmet

Carla Bell writes about James Forman’s famous 1969 address, The Black Manifesto , and its contemporary resonances:

“But the Manifesto is as vital a roadmap in our marches and protests today as the day it was first delivered. We, black people in America, remain compelled by the power and purpose of The Black Manifesto, and we continue to demand our full rights as a people of this decadent society.”

You Should Have Been Listening to Octavia Butler This Whole Time

Alicia A. Wallace writes that Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower isn’t just a prescient dystopia—it’s a monument to the wisdom of Black women and girls:

Through her protagonist Lauren Olamina, Butler has been telling the world for decades that it was not going to last in its capitalist, racist, sexist, homophobic form for much longer. She showed us the way injustice would cause the earth to burn, and the importance of community building for survival and revolution. Through Parable of the Sowe r, we had a better future in our hands, but we did not listen.

The Book You Need to Fully Understand How Racism Operates in America

Darryl Robertson writes about Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning and its examination of the history of overt and covert bigotry:

“While How to Be an Antiracist is an informative and necessary read, it is his National Book Award-winning, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America that deserves extra attention. If we want to uproot the current racist system, it’s mandatory that we understand how racism was constructed. Stamped does just that.”

I Reject the Imaginary White Man Judging My Work

Tracey Michae’l Lewis-Giggetts turns to Black writers as inspiration for resisting white expectations:

“…it doesn’t only matter that I’m a Black woman telling my story. What matters is the lens through which I’m telling it. And sometimes, many times, that lens, if we’re not careful, can be tainted by the ever-present consciousness of Whiteness as the default.”

Toni Morrison Gave My Own Story Back to Me

The incomparable literary powerhouse showed Brandon Taylor how to stop letting white people dictate the shape of his narrative:

“That’s the magic of Toni Morrison. Once you read her, the world is never the same. It’s deeper, brighter, darker, more beautiful and terrible than you could ever imagine. Her work opens the world and ushers you out into it. She resurfaced the very texture and nature of my imagination and what I could conceive of as possible for writing and for art, for life.”

Art Must Engage With Black Vitality, Not Just Black Pain

Jennifer Baker writes that books like The Fire This Time give depth and nuance to a reflection of Blackness in America:

“These essays provided a deeper connection because Black pain was part of the story; Black identity, self-recognition, our own awareness brokered every page. Black pain was not the sole criterion for the anthology’s existence.”

When Black Characters Wear White Masks

Jennifer Baker writes that whiteface in literature isn’t a disavowal of Blackness, but a commentary on privilege:

“Whiteface stories interrogate the mentality that it’s better to be white while examining how societal gains as well as societal “norms” inflict this way of thinking on Black people. Being white isn’t better, but, for some of these characters, it seems a hell of a lot easier, or at least preferable to dealing with racism.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

Traveling South to Understand the Soul of America

Imani Perry examines how the history of slavery, racism, and activism in the South has shaped the entire country

Jun 17 - Deirdre Sugiuchi Read

More like this.

In “James,” Percival Everett Does More than Reimagine “Huck Finn”

The author discusses writing from the perspective of Jim and language as a tool of oppression

Mar 19 - Bareerah Ghani

The Stakes of Driving While Black Are Unconscionably High

"Wedding Season (A Nocturne for Sandra Bland)," excerpted from the essay collection "You Get What You Pay For"

Mar 12 - Morgan Parker

10 Memoirs and Essay Collections by Black Women

These contemporary books illuminate the realities of the world for Black women in America

Nov 29 - Alicia Simba

DON’T MISS OUT

Sign up for our newsletter to get submission announcements and stay on top of our best work.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Black History

Civil Rights Movement Timeline

The civil rights movement was an organized effort by black Americans to end racial discrimination and gain equal rights under the law. It began in the late 1940s and ended in the late 1960s.

Rosa Parks (1913—2005) helped initiate the civil rights movement in the United States when she refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery, Alabama bus in 1955. Her actions inspired the leaders of the local Black community to organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Black History Month

February is dedicated as Black History Month, honoring the triumphs and struggles of African Americans throughout U.S. history.

Black History Milestones: Timeline

Black history in the United States is a rich and varied chronicle of slavery and liberty, oppression and progress, segregation and achievement.

Coretta Scott King

After her husband became pastor, Coretta Scott King joined the choir at the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church. Hear two of her friends and members of the congregation remember Mrs. King’s legacy and her voice.

When Segregationists Bombed Martin Luther King Jr.’s House

On January 30, 1956, Martin Luther King Jr.’s house was bombed by segregationists in retaliation for the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Brown v. Board of Education

In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously strikes down segregation in public schools, sparking the Civil Rights movement.

How the Montgomery Bus Boycott Accelerated the Civil Rights Movement

For 382 days, almost the entire African-American population of Montgomery, Alabama, including leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, refused to ride on segregated buses, a turning point in the American civil rights movement.

The Black Explorer Who May Have Reached the North Pole First

In 1909 African American Matthew Henson trekked with explorer Robert Peary, reaching what they claimed was the North Pole. Who got there first?

How Madam C.J. Walker Became a Self-Made Millionaire

Despite Jim Crow oppression, Walker founded her own haircare company that helped thousands of African American women gain financial independence.

8 Black Inventors Who Made Daily Life Easier

Black innovators changed the way we live through their many innovations, from the traffic light to the ironing board.

Harlem Renaissance: Photos From the African American Cultural Explosion

From jazz and blues to poetry and prose to dance and theater, the Harlem Renaissance of the early 20th century was electric with creative expression by African American artists.

This Day in History

Martin Luther King Jr. writes “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”

Misty copeland becomes american ballet theater’s first black principal dancer, mae jemison becomes first black woman in space, harlem riot of 1935, rebecca lee crumpler becomes first black woman to earn a medical degree, first hbcu, lincoln university, chartered.

Cracking the Code of the Human Genome

A Smithsonian magazine special report

The Changing Definition of African-American

How the great influx of people from Africa and the Caribbean since 1965 is challenging what it means to be African-American

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-of-Mind-Jacob-Lawrence-Migration-Series-631.jpg)

Some years ago, I was interviewed on public radio about the meaning of the Emancipation Proclamation. I addressed the familiar themes of the origins of that great document: the changing nature of the Civil War, the Union army’s growing dependence on black labor, the intensifying opposition to slavery in the North and the interplay of military necessity and abolitionist idealism. I recalled the longstanding debate over the role of Abraham Lincoln, the Radicals in Congress, abolitionists in the North, the Union army in the field and slaves on the plantations of the South in the destruction of slavery and in the authorship of legal freedom. And I stated my long-held position that slaves played a critical role in securing their own freedom. The controversy over what was sometimes called “self-emancipation” had generated great heat among historians, and it still had life.

As I left the broadcast booth, a knot of black men and women—most of them technicians at the station—were talking about emancipation and its meaning. Once I was drawn into their discussion, I was surprised to learn that no one in the group was descended from anyone who had been freed by the proclamation or any other Civil War measure. Two had been born in Haiti, one in Jamaica, one in Britain, two in Ghana, and one, I believe, in Somalia. Others may have been the children of immigrants. While they seemed impressed—but not surprised—that slaves had played a part in breaking their own chains, and were interested in the events that had brought Lincoln to his decision during the summer of 1862, they insisted it had nothing to do with them. Simply put, it was not their history.

The conversation weighed upon me as I left the studio, and it has since. Much of the collective consciousness of black people in mainland North America—the belief of individual men and women that their own fate was linked to that of the group—has long been articulated through a common history, indeed a particular history: centuries of enslavement, freedom in the course of the Civil War, a great promise made amid the political turmoil of Reconstruction and a great promise broken, followed by disfranchisement, segregation and, finally, the long struggle for equality.

In commemorating this history—whether on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, during Black History Month or as current events warrant—African- Americans have rightly laid claim to a unique identity. Such celebrations—their memorialization of the past—are no different from those attached to the rituals of Vietnamese Tet celebrations or the Eastern Orthodox Nativity Fast, or the celebration of the birthdays of Christopher Columbus or Casimir Pulaski; social identity is ever rooted in history. But for African-Americans, their history has always been especially important because they were long denied a past.

And so the “not my history” disclaimer by people of African descent seemed particularly pointed—enough to compel me to look closely at how previous waves of black immigrants had addressed the connections between the history they carried from the Old World and the history they inherited in the New.

In 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, which became a critical marker in African-American history. Given opportunity, black Americans voted and stood for office in numbers not seen since the collapse of Reconstruction almost 100 years earlier. They soon occupied positions that had been the exclusive preserve of white men for more than half a century. By the beginning of the 21st century, black men and women had taken seats in the United States Senate and House of Representatives, as well as in state houses and municipalities throughout the nation. In 2009, a black man assumed the presidency of the United States. African-American life had been transformed.

Within months of passing the Voting Rights Act, Congress passed a new immigration law, replacing the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which had favored the admission of northern Europeans, with the Immigration and Nationality Act. The new law scrapped the rule of national origins and enshrined a first-come, first-served principle that made allowances for the recruitment of needed skills and the unification of divided families.

This was a radical change in policy, but few people expected it to have much practical effect. It “is not a revolutionary bill,” President Lyndon Johnson intoned. “It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives.”

But it has had a profound impact on American life. At the time it was passed, the foreign-born proportion of the American population had fallen to historic lows—about 5 percent—in large measure because of the old immigration restrictions. Not since the 1830s had the foreign-born made up such a tiny proportion of the American people. By 1965, the United States was no longer a nation of immigrants.

During the next four decades, forces set in motion by the Immigration and Nationality Act changed that. The number of immigrants entering the United States legally rose sharply, from some 3.3 million in the 1960s to 4.5 million in the 1970s. During the 1980s, a record 7.3 million people of foreign birth came legally to the United States to live. In the last third of the 20th century, America’s legally recognized foreign-born population tripled in size, equal to more than one American in ten. By the beginning of the 21st century, the United States was accepting foreign-born people at rates higher than at any time since the 1850s. The number of illegal immigrants added yet more to the total, as the United States was transformed into an immigrant society once again.

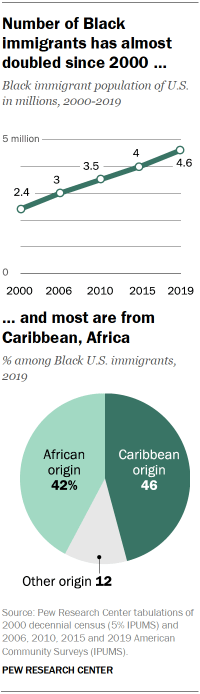

Black America was similarly transformed. Before 1965, black people of foreign birth residing in the United States were nearly invisible. According to the 1960 census, their percentage of the population was to the right of the decimal point. But after 1965, men and women of African descent entered the United States in ever-increasing numbers. During the 1990s, some 900,000 black immigrants came from the Caribbean; another 400,000 came from Africa; still others came from Europe and the Pacific rim. By the beginning of the 21st century, more people had come from Africa to live in the United States than during the centuries of the slave trade. At that point, nearly one in ten black Americans was an immigrant or the child of an immigrant.

African-American society has begun to reflect this change. In New York, the Roman Catholic diocese has added masses in Ashanti and Fante, while black men and women from various Caribbean islands march in the West Indian-American Carnival and the Dominican Day Parade. In Chicago, Cameroonians celebrate their nation’s independence day, while the DuSable Museum of African American History hosts a Nigerian Festival. Black immigrants have joined groups such as the Egbe Omo Yoruba (National Association of Yoruba Descendants in North America), the Association des Sénégalais d’Amérique and the Fédération des Associations Régionales Haïtiennes à l’Étranger rather than the NAACP or the Urban League.

To many of these men and women, Juneteenth celebrations—the commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States—are at best an afterthought. The new arrivals frequently echo the words of the men and women I met outside the radio broadcast booth. Some have struggled over the very appellation “African-American,” either shunning it—declaring themselves, for instance, Jamaican-Americans or Nigerian-Americans—or denying native black Americans’ claim to it on the ground that most of them had never been to Africa. At the same time, some old-time black residents refuse to recognize the new arrivals as true African-Americans. “I am African and I am an American citizen; am I not African-American?” a dark-skinned, Ethiopian-born Abdulaziz Kamus asked at a community meeting in suburban Maryland in 2004. To his surprise and dismay, the overwhelmingly black audience responded no. Such discord over the meaning of the African-American experience and who is (and isn’t) part of it is not new, but of late has grown more intense.

After devoting more than 30 years of my career as a historian to the study of the American past, I’ve concluded that African-American history might best be viewed as a series of great migrations, during which immigrants—at first forced and then free—transformed an alien place into a home, becoming deeply rooted in a land that once was foreign, even despised. After each migration, the newcomers created new understandings of the African-American experience and new definitions of blackness. Given the numbers of black immigrants arriving after 1965, and the diversity of their origins, it should be no surprise that the overarching narrative of African-American history has become a subject of contention.

That narrative, encapsulated in the title of John Hope Franklin’s classic text From Slavery to Freedom , has been reflected in everything from spirituals to sermons, from folk tales to TV docudramas. Like Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery , Alex Haley’s Roots and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, it retells the nightmare of enslavement, the exhilaration of emancipation, the betrayal of Reconstruction, the ordeal of disfranchisement and segregation, and the pervasive, omnipresent discrimination, along with the heroic and ultimately triumphant struggle against second-class citizenship.

This narrative retains incalculable value. It reminds men and women that a shared past binds them together, even when distance and different circumstances and experiences create diverse interests. It also integrates black people’s history into an American story of seemingly inevitable progress. While recognizing the realities of black poverty and inequality, it nevertheless depicts the trajectory of black life moving along what Dr. King referred to as the “arc of justice,” in which exploitation and coercion yield, reluctantly but inexorably, to fairness and freedom.

Yet this story has had less direct relevance for black immigrants. Although new arrivals quickly discover the racial inequalities of American life for themselves, many—fleeing from poverty of the sort rarely experienced even by the poorest of contemporary black Americans and tyranny unknown to even the most oppressed—are quick to embrace a society that offers them opportunities unknown in their homelands. While they have subjected themselves to exploitation by working long hours for little compensation and underconsuming to save for the future (just as their native-born counterparts have done), they often ignore the connection between their own travails and those of previous generations of African-Americans. But those travails are connected, for the migrations that are currently transforming African-American life are directly connected to those that have transformed black life in the past. The trans-Atlantic passage to the tobacco and rice plantations of the coastal South, the 19th-century movement to the cotton and sugar plantations of the Southern interior, the 20th-century shift to the industrializing cities of the North and the waves of arrivals after 1965 all reflect the changing demands of global capitalism and its appetite for labor.

New circumstances, it seems, require a new narrative. But it need not—and should not—deny or contradict the slavery-to-freedom story. As the more recent arrivals add their own chapters, the themes derived from these various migrations, both forced and free, grow in significance. They allow us to see the African-American experience afresh and sharpen our awareness that African-American history is, in the end, of one piece.

Ira Berlin teaches at the University of Maryland. His 1999 study of slavery in North America, Many Thousands Gone , received the Bancroft Prize.

Adapted from The Making of African America , by Ira Berlin. © 2010. With the permission of the publisher, Viking, a member of the Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Essay on African American

Students are often asked to write an essay on African American in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on African American

Who are african americans.

African Americans are people in the United States whose ancestors come from Africa. They may also be called Black Americans. Many African Americans were brought to America as slaves long ago. Today, they are an important part of American society, culture, and history.

History of African Americans

The history of African Americans is filled with struggles and victories. They were slaves in America for about 250 years. After slavery ended in 1865, they fought for equal rights. This fight is known as the Civil Rights Movement.

African American Culture

African American culture is rich and diverse. It includes music, dance, art, and food that have African roots. Jazz, blues, and hip-hop music were all created by African Americans. Their culture has greatly influenced American society.

Famous African Americans

There are many famous African Americans. Martin Luther King Jr. fought for equal rights. Barack Obama became the first African American president. Oprah Winfrey is a famous TV host. Their achievements inspire many people.

African Americans Today

Today, African Americans continue to contribute to American society. They are leaders, artists, scientists, athletes, and more. They face challenges, like racism, but they also celebrate their unique culture and history.

250 Words Essay on African American

African Americans are people in the United States who have ancestors from Africa. They are also called Black Americans or Afro-Americans. They are a big part of the population in the U.S. Many African Americans have made big contributions in different fields like science, arts, sports, and politics.

The history of African Americans started in the 16th century when Africans were brought to the U.S. as slaves. Slavery was a tough time for them. They had to work hard with no pay. They were not treated well. In 1865, slavery ended in the U.S. This was a big change for African Americans. But, they still faced many problems. They had to fight for their rights.

There are many famous African Americans. Martin Luther King Jr. was a leader who fought for the rights of African Americans. He gave a famous speech called “I Have a Dream”. Barack Obama is another famous African American. He was the first African American president of the U.S.

African Americans have a rich culture. They have their own music, dance, art, and food. Jazz and blues are types of music that were created by African Americans. Their culture has had a big effect on American culture.

In the end, African Americans have a rich history and culture. They have faced many challenges but have also achieved a lot. They have made the U.S. a better place with their contributions.

500 Words Essay on African American

African Americans are people in the United States who have roots in Africa. These people are often called “Black” and they form one of the largest ethnic groups in the country. Their ancestors were brought to America many years ago as slaves. Over time, they fought for their rights and freedom. Today, African Americans have made significant contributions to the culture, society, and history of the United States.

African American History

The history of African Americans is rich and complex. It starts from the 16th century when the first African slaves were brought to the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia. They were forced to work on plantations, growing crops like tobacco and cotton.

In the 19th century, a war was fought over slavery – the Civil War. After this war, slavery was ended with the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865. This was a big step towards freedom for African Americans. But, they still had to fight for equal rights. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement took place. African Americans, along with many others, protested against racial discrimination. They wanted equal treatment in schools, jobs, and public places. This movement led to laws that protected the rights of African Americans.

African American culture is a blend of African and American traditions. It is seen in music, food, language, and art. African Americans have had a big influence on music. They created jazz, blues, hip-hop, and R&B. Famous African American musicians include Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Michael Jackson.

In food, dishes like fried chicken, cornbread, and collard greens come from African American culture. They also have a unique style of speaking, known as African American Vernacular English. In art, African Americans have made beautiful paintings, sculptures, and films.

Today, African Americans are found in all walks of life. They are doctors, teachers, scientists, athletes, and politicians. They have achieved a lot, despite facing many challenges. Barack Obama, an African American, was elected as the President of the United States in 2008. This was a historic moment.

Yet, African Americans still face problems like racial discrimination and poverty. They are working hard to overcome these issues and continue to contribute in many ways to American society.

In conclusion, African Americans have a rich history and culture. They have faced many struggles but have also achieved a lot. They continue to shape the United States with their contributions and efforts. Their story is a vital part of American history.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Afghanistan

- Essay on Advertisement Boon Or Bane

- Essay on Need for Man Making Education

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Stanford scholars reflect on Black history in their lives and work

Humanities and social sciences scholars reflect on “Black history as American history” and its impact on their personal and professional lives.

As Black History Month comes to a close, Stanford faculty reflect on the crucial contributions of Black Americans that should be studied and celebrated not only during February but also throughout the year. Whether examining the impact of writers like Toni Morrison, Civil War-era abolitionists or present-day political activists in Georgia, scholars from the humanities and social sciences emphasize that the history of Black Americans is essential to understanding our nation and our world.

Below, scholars from the School of Humanities and Sciences talk about how an understanding of Black history has shaped them personally and is integral to their research and work.

Hakeem Jefferson (Image credit: Harrison Truong)

Hakeem Jefferson Assistant Professor, Political Science

This year’s Black History Month comes on the heels of a white supremacist insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. With this tragic event in mind, I am reminded that Black people have long served as the conscience of nations around the world in moments of crisis. I am reminded of brave abolitionists and freedom fighters and artists and everyday people who, with everything to lose, including life itself, have stood as vanguards and safekeepers of our democracy. And as a political scientist whose work tries to highlight the diversity and complexity of Black politics, I am reminded of Black activists and organizers in places like Georgia and Texas and Arizona who are working right now to make real the promise of democracy not just for Black people but also for all of us.

As a community of scholars, we have an opportunity to join these efforts, and this Black History Month offers us another opportunity to recommit ourselves to the cause of democracy – a cause Black people in this country have been advancing for generations and continue to advance today. The real question is whether we have the courage to stand with them.

Tomás Jiménez (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Tomás Jiménez Associate Professor, Sociology

Black history is American history. At each step in our nation’s development, Black Americans have led the call and shown by example how to live out the promise in our founding documents. Living up to that promise is an ongoing project. Taking up the challenge of that project requires reckoning with the ways that institutions and individuals have subjugated Black Americans through direct action, inaction or both. It also requires honoring the contributions of Black Americans to every aspect of American life, from politics and science, to art and spirituality.

It is well worth honoring the widely known individuals who have made those contributions. But we should also lift up individuals for whom there will never be a monument or plaque, but who have worked in every facet of American life to make our country a better place. They too made and continue to make Black history; to make American history.

Paula M. L. Moya (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Paula M. L. Moya Danily C. and Laura Louise Bell Professor in the Humanities Professor, English

I study literature written by people of African descent not just for its wisdom, profundity, sadness and humor, but also because not to do so would leave me ignorant of a crucial history that has contributed fundamentally to making our nation what it is.

Toni Morrison is, for me and so many others, a beacon of wisdom and truth. Her writings, along with those of Frantz Fanon, Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara and James Baldwin (among others), have taught me important lessons about how I, as a human being and also as a woman of color, can live with generosity in this challenging but beautiful world. I treasure their words, I carry them around in my heart and I use them to guide me as I make difficult decisions about who to care for and how to love even those who might not seek to love me back.

Patrick Phillips (Image credit: Marion Ettlinger)

Patrick Phillips Professor, English Interim Director, Creative Writing Program

I see the history of Black Americans as another name for real American history – for our full history as a nation. And I think more people are finally rejecting a whitewashed version of the past, designed to protect white people from ever facing the monumental crimes of our ancestors, and from ever acknowledging the central role of African Americans in building American prosperity.

I learned this firsthand when I was doing research for a book about my hometown’s long-hidden history of lynching, white-supremacist terror and land theft. It also chronicles the lives of heroic Black residents who, amid crushing injustice, built new lives in post-Emancipation Georgia.

As a white southerner, I see the study of Black history as an urgent corrective to white America’s long tradition of willful ignorance and complicit silence. For as James Baldwin said, “it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.”

Steven O. Roberts (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Steven O. Roberts Assistant Professor, Psychology

“History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.” —James Baldwin

We, as individuals and as a collective, cannot understand ourselves if we do not understand Black history. And the term itself is important to contextualize. Black history is U.S. history. It is human history. To understand Black history is to know the strength and resilience necessary to affirm one’s humanity, as affirmed by Malcolm and Queen Nzinga and many others. To understand Black history is to feel the heart and depth necessary to sing in soul, as sang by Aretha and Cooke and many others. To understand Black history is to understand what has been and what should be.

There ain’t no history like Black history, and I’m so honored to carry that history with me.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

David Brooks

How Racist Is America?

By David Brooks

Opinion Columnist

One question lingers amid all the debates about critical race theory: How racist is this land? Anybody with eyes to see and ears to hear knows about the oppression of the Native Americans, about slavery and Jim Crow. But does that mean that America is even now a white supremacist nation, that whiteness is a cancer that leads to oppression for other groups? Or is racism mostly a part of America’s past, something we’ve largely overcome?

There are many ways to answer these questions. The most important is by having honest conversations with the people directly affected. But another is by asking: How high are the barriers to opportunity for different groups? Do different groups have a fair shot at the American dream? This approach isn’t perfect, but at least it points us to empirical data rather than just theory and supposition.

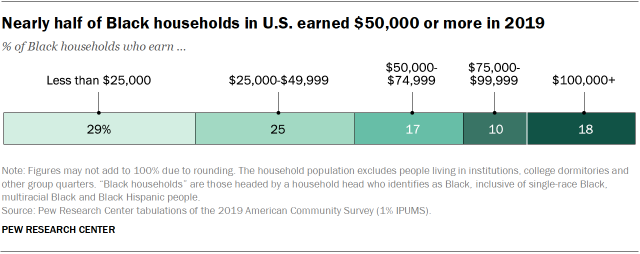

When we apply this lens to the African American experience we see that barriers to opportunity are still very high. The income gap separating white and Black families was basically as big in 2016 as it was in 1968 . The wealth gap separating white and Black households grew even bigger between those years. Black adults are over 16 times more likely to be in families with three generations of poverty than white adults.

Research shows the role racism plays in perpetuating these disparities. When, in 2004, researchers sent equally qualified white and Black applicants to job interviews in New York City, dressed them similarly and gave them similar things to say, Black applicants got half as many callbacks or job offers as whites.

When you look at the data about African Americans, the legacies of slavery and segregation and the effects of racism are everywhere. The phrase “systemic racism” aptly fits the reality you see — a set of structures, like redlining, that have a devastating effect on Black wealth and opportunities. Racism is not something we are gently moving past; it’s pervasive. It seems obvious that this reality should be taught in every school.

Does this mean that America is white supremacist, a shameful nation, that the American dream is just white privilege? Well, let’s take a look at the data for different immigrant groups. When you turn your gaze here, the barriers don’t seem as high. For example, as Bloomberg’s Noah Smith pointed out recently on his Substack page, Hispanic American incomes rose faster in recent years than those of any other major group in America. Forty-five percent of Hispanics who grew up in poverty made it to the middle class or higher , comparable to the mobility rate for whites.

Hispanics have lately made astounding gains in education. In 2000, more than 30 percent of Hispanics dropped out of high school. By 2016, only 10 percent did. In 1999, a third of Hispanics age 18 to 24 were in college; now, nearly half are. Hispanic college enrollment rates surpassed white enrollment rates in 2012.

The Hispanic experience in America is beginning to look similar to the experience of Irish Americans or Italian Americans or other past immigrant groups — a period of struggle followed by integration into the middle class.

A study by scholars from Princeton, Stanford and the University of California at Davis found that today’s children of immigrants are no slower to move up to the middle class than the children of immigrants 100 years ago. It almost doesn’t matter whether their parents came from countries from which immigrants are mainly fleeing misery and poverty, or from countries from which immigrants often arrive with marketable skills, children of poor immigrants have higher rates of upward mobility than the children of the native-born.

This economic success obviously does not mean immigrant groups do not face hardship, bias and exploitation. Almost every immigrant group in American history has faced that. It just means that education and mobility can help overcome some of the effects of this bias. According to that same study, immigrant groups are largely doing well because they come to places where opportunity is plentiful. They are not so much earning more than those around them, but earning more along with those around them.

Economic progress is one thing. What about cultural integration?

A landmark 2015 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found that the lives of immigrants and their children are converging with those of their native-born neighbors, in good ways and bad. This pattern applies to how well educated they are, where they live, what language they speak, how their health is and how they organize their families. A study by a Brown University sociologist, for example, found that Mexican immigrants are learning English at increasingly higher rates and growing less isolated from non-Mexican Americans.

Rising intermarriage rates are one product of this integration. According to a 2017 Pew Research Center report , about 29 percent of Asian American newlyweds are married to someone of a different race or ethnicity, along with 27 percent of Hispanic newlyweds. The intermarriage rates for white and Black people have roughly tripled since 1980. More than 35 percent of Americans say that one of their “close” kin is of a different race.

Blending identities is another sign of this integration. There was an idea going around a few years ago that America was about to become a majority-minority country. This would be true only if you rigidly divided Americans into white and (with one drop of nonwhite blood) nonwhite categories.

But real humans are very quick to adopt multiple and shifting racial identities. The researchers Richard Alba, Morris Levy and Dowell Myers suggest 52 percent of the people who self-categorize as nonwhite in the Census Bureau’s projections for America’s 2060 racial makeup will also think of themselves as white. Forty percent of those who self-categorized as white will also claim minority racial identity.

In an essay for The Atlantic, they conclude: “Speculating about whether America will have a white majority by the mid-21st century makes little sense, because the social meanings of white and nonwhite are rapidly shifting. The sharp distinction between these categories will apply to many fewer Americans.”

When you look at the data across groups, a few points stand out.

First, you can see why some people have issues with the phrase “people of color.” How could a category that covers a vast majority of all human beings have much meaning? The groups that the phrase attempts to bring together have different experiences and even face different kinds of bias. Perhaps this phrase covers over real identities instead of illuminating them.

Writing in GQ, Damon Young argues that the term “people of color” has become a linguistic gesture, “shorthand for white people uncomfortable with just saying ‘Black.’” In The New Yorker, E. Tammy Kim argues , “‘People of color,’ by grouping all nonwhites in the United States, if not the world, fails to capture the disproportionate per-capita harm to Blacks at the hands of the state.”

Second, it’s certainly time to dump the replacement theory that has been so popular with Tucker Carlson and the far right — the idea that all these foreigners are coming to take over the country. This is an idea that panics a lot of whites and helped elect Donald Trump, but it’s not true. In truth, immigrants blend with the current inhabitants, keeping parts of their earlier identities and adopting parts of their new identities. This has been happening for hundreds of years, and it is still happening. This kind of intermingling of groups is not replacing America; it is America.

Finally, it may not be accurate to say that America can be neatly divided into rival ethnic camps, locked in zero-sum conflict with each other. The real story is more about blending and fluidity. I’m just one guy with one (white) point of view. But my reading of the historical record suggests groups do well by mingling with everybody else while keeping some of their own distinct identities and cultures. “Integration without assimilation” is how Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks put it.

The interwoven reality of America defies simple binaries of white versus nonwhite. Over the last several years Raj Chetty and his team at Opportunity Insights have done much of the most celebrated work on income mobility. They find that, indeed, Black Americans and Native Americans have much lower rates of mobility because of historic discrimination.

But Chetty’s team emphasizes that these gaps are not immutable. If, for example, you use housing vouchers and other grants to help people move to high-opportunity neighborhoods with low poverty rates, low racial bias and more fathers in the neighborhoods, then you can help people of all races lead lives with higher incomes and lower rates of incarceration as adults.

The reality of America encompasses both the truth about structural racism and the truth that America is a land of opportunity for an astounding diversity of groups from around the world. There’s no way to simplify that complexity.

Last week I saw a young Black woman wearing a T-shirt that read, “I am my ancestors’ wildest dreams.” I took her message as a statement of defiance, pride, determination and hope. If you can keep discordant emotions like that in your head, you can get a feel for this discordant land.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

David Brooks has been a columnist with The Times since 2003. He is the author of “The Road to Character” and, most recently, “The Second Mountain.” @ nytdavidbrooks

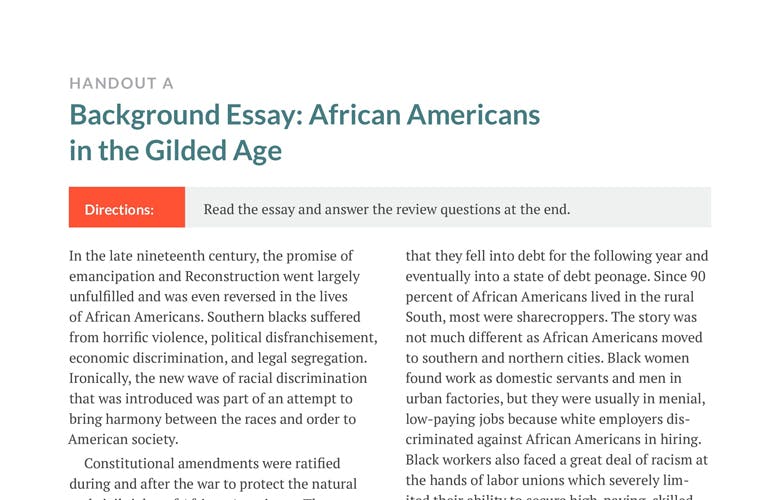

Handout A: Background Essay: African Americans in the Gilded Age

Background Essay: African Americans in the Gilded Age

Directions: Read the essay and answer the review questions at the end.

In the late nineteenth century, the promise of emancipation and Reconstruction went largely unfulfilled and was even reversed in the lives of African Americans. Southern blacks suffered from horrific violence, political disfranchisement, economic discrimination, and legal segregation. Ironically, the new wave of racial discrimination that was introduced was part of an attempt to bring harmony between the races and order to American society.

Constitutional amendments were ratified during and after the war to protect the natural and civil rights of African Americans. The Thirteenth Amendment forever banned slavery from the United States, the Fourteenth Amendment protected black citizenship, and the Fifteenth Amendment granted the right to vote to African-American males. In addition, a Freedmen’s Bureau was established to help the economic condition of former slaves, and Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in 1875.

Roadblocks to Equality

Despite these legal protections, the economic condition of African Americans significantly worsened in the last few decades of the nineteenth century. Poor southern black farmers were generally forced into sharecropping whereby they borrowed money to plant a year’s crop, using the future crop as collateral on the loan. Often, they owed so much of the resulting crop that they fell into debt for the following year and eventually into a state of debt peonage. Since 90 percent of African Americans lived in the rural South, most were sharecroppers. The story was not much different as African Americans moved to southern and northern cities. Black women found work as domestic servants and men in urban factories, but they were usually in menial, low-paying jobs because white employers discriminated against African Americans in hiring. Black workers also faced a great deal of racism at the hands of labor unions which severely limited their ability to secure high-paying, skilled jobs. While the Knights of Labor and United Mine Workers were open to blacks, the largest skilled-worker union, the American Federation of Labor, curtailed black membership, thereby limiting them to menial labor.

African Americans throughout the country suffered from violence and intimidation. The most infamous examples of violence were brutal lynchings, or executions without due process, by angry white mobs. These travesties resulted in hangings, burnings, shootings, and mutilations for between 100 and 200 blacks—especially black men falsely accused of raping white women—annually. Race riots broke out in southern and northern cities from New Orleans and Atlanta to New York and Evansville, Indiana, causing dozens of deaths and property damage.

Although African Americans were elected to Congress and state legislatures during Reconstruction, and enjoyed the constitutional right to vote, black civil rights were systematically stripped away in a campaign of disfranchisement. One method was to charge a poll tax to vote, which precious few black sharecroppers could afford to pay. Another strategy was the literacy test which few former slaves could pass. Furthermore, the white clerks at courthouses had already decided that any black applicant would fail, regardless of his true reading ability. Since both of those devices at times excluded poor whites as well, grandfather clauses were introduced to exempt from the literacy test anyone whose father or grandfather had the right to vote before the Civil War. Moreover, the Supreme Court declared the 1875 Civil Rights Act guaranteeing equal access to public facilities and transportation to be unconstitutional in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) because the law regulated the private discriminatory conduct of individuals rather than government discrimination.

Segregation

One of the most pervasive and visible signs of racism was the rise of informal and legal segregation, or separation of the races. In a wholesale violation of liberty and equality, southern state legislatures passed “Jim Crow” segregation laws that denied African Americans equal access to public facilities such as hotels, restaurants, parks, and swimming pools. Southern schools and public transportation had vastly inferior “separate but equal” facilities that left the black minority subject to unjust majority rule. Housing covenants and other devices kept blacks in separate neighborhoods from whites. African Americans in the North also suffered informal residential segregation and economic discrimination in jobs.

In one of its more infamous decisions, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation statutes were legal in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In Plessy, the Court decided that “separate, but equal” public facilities did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment or imply the inferiority of African Americans. Justice John Marshall Harlan was one of the two dissenters who wrote, “Our constitution is colorblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.”

Progressive and Race Relations

One of the great ironies of the series of reforms instituted in the early twentieth century known as the Progressive Era was that segregation and racism were deeply enshrined in the movement. Progressives were a group of reformers who believed that the industrialized, urbanized United States of the nineteenth century had outgrown its eighteenth-century Constitution. That Constitution did not give government, especially the federal government, enough power to deal with unprecedented problems. Many Progressives embraced Social Darwinism and eugenics which was part of the most advanced science and social science taught in universities and scientific circles. Social Darwinism ranked various groups, which its proponents considered “races,” according to certain characteristics and labelled Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic peoples as superior and Southeastern Europeans, Jews, Asians, Hispanics, and Africans as inferior races. Therefore, there was a supposed scientific basis for segregation as the “higher” races ruled the “lower.” Moreover, Progressives generally endorsed segregation as a means of achieving their central goal of social order and harmony between the races. There were notable exceptions, such as Jane Addams, black Progressives such as W.E.B. DuBois, and the Progressives of both races who founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), but Progressive ideology contributed to the growth of segregation.

Progressive Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson generally supported the segregationist order. While Roosevelt courageously invited African-American leader Booker T. Washington to dinner in the White House and condemned lynching, he discharged 170 black soldiers because of a race riot in Brownsville, Texas in 1906. Wilson had perhaps a worse record on civil rights as his administration fired many black federal employees and segregated federal departments.

Black Leadership

Several black leaders advanced the cause of black civil rights and helped organize African Americans to defend their interests through self help. The highly-educated journalist, Ida B. Wells, launched a crusade against lynching by exposing the savage practice. She also challenged segregation by refusing to change her seat on a train because it was in an area reserved for white women. Other African Americans unsuccessfully boycotted segregated streetcars in urban areas but utilized a method that would prove successful in the mid-twentieth century.

A debate took shape between two African-American leaders, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois. Washington was a former slave who founded the Tuskegee Institute for blacks in the 1880s and wrote Up from Slavery. He advocated that African Americans achieve racial equality slowly by patience and accommodation. Washington thought that blacks should be trained in industrial education and demonstrate the character virtues of hard work, thrift, and self-respect. They would therefore prove that they deserved equal rights and equal opportunity for social mobility. At the 1895 Atlanta Exposition, Washington delivered an address that posited, “In the long run it is the race or individual that exercises the most patience, forbearance, and self-control in the midst of trying conditions that wins…the respect of the world.”

DuBois, on the other hand, was a Harvard and Berlin-educated intellectual who believed that African Americans should win equality through a liberal arts education and fighting for political and civil equality. He wrote the Souls of Black Folk and laid out a vision whereby the “talented tenth” among African Americans would receive an excellent education and become the teachers and other professionals who would uplift fellow members of their race. He and other black leaders organized the Niagara Movement that fought segregation, lynching, and disfranchisement. In 1909 the movement’s leaders founded the NAACP, which fought for black equality and initiated a decades-long legal struggle to end segregation. DuBois edited its journal named The Crisis and wrote about issues affecting African Americans. He had the simple wish to “make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face.”

Wartime Changes