Introductory essay

Written by the educators who created Leading Wisely, a brief look at the key facts, tough questions and big ideas in their field. Begin this TED Study with a fascinating read that gives context and clarity to the material.

Understanding management means understanding people. What motivates us to engage deeply and perform powerfully at work? How do we inspire that in teams? What are the best ways to organize ourselves to exploit opportunities and solve problems? These are critical questions for all leaders who share the goal of thriving in a global, digital, fast-paced future.

There are countless ways we can approach those topics, and diverse perspectives to consider—as is evident from the thousands of management manuals, podcasts, executive seminars and more. For example, among the TED Talks included in Leading Wisely, Itay Talgam shares a lyrical metaphor on the style of the great conductors, while Clay Shirky delivers a statistical deconstruction of the power of informal networks. It's precisely this enormous scope and variety that defines the reality of modern management and which makes it so fascinating, and so vital. Modern thinking on management — from teaching and research inside universities to the way the world's most revered businesses organize themselves — has continuously evolved throughout the 20th and early 21st century. What's more, the pace of this evolution is increasing: the TED Talks in this collection cover a number of topics that didn't even exist ten years ago! This means successful managers must learn quickly, forecast trends and execute wisely.

Division of labor and beyond: Management theory is born

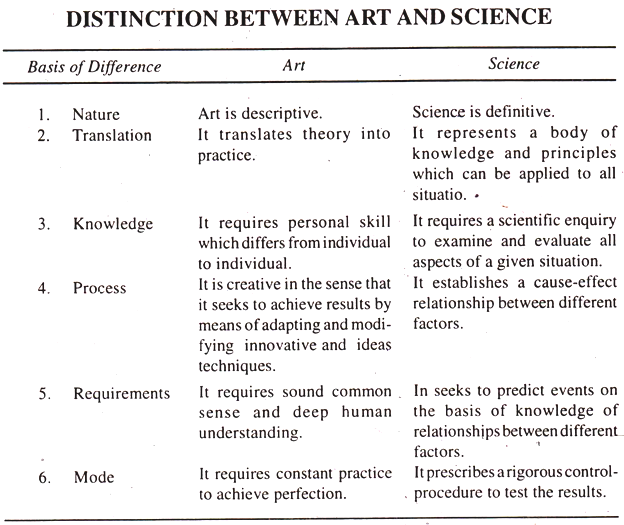

Industrialization shaped the work of the first management theorists in the US and Europe, where efforts to perfect new production processes gave management a practical focus and scientific method. Mining engineer Henri Fayol was one of the first to set out clear principles of management, which were formed through experiences organizing labor and machinery to extract coal in the most cost-efficient way. In the early decades of the 20th century Fayol identified six core principles of management: forecasting, planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, and controlling. A century later, these key principles still shape our ideas about management, even though we may implement them in more sophisticated ways.

In Fayol's time, managers enacted these six principles through authority and discipline, and the regimentation of that approach created as many problems as it did advantages. For example, perfecting production techniques through the division of labor involved a systematic breaking-down of production into repetitive, individual tasks, or 'piece work'. This formed the foundation of a new mass-production economy and significantly improved the standard of living for many workers and consumers--but the work was often tedious and didn't draw upon the worker's ideas or abilities in any meaningful way.

Fayol's contemporary, Henry Ford, provides the most famous example. In his quest to mass-produce an affordable automobile, Ford identified 84 specific steps required to assemble the Model T and hired Frederick Taylor, the creator of "scientific management," to conduct time and motion studies on the factory floor. In this way, Ford reasoned, he would know exactly how long it should take his workers to complete each of the 84 steps, and he could direct the exact motions each worker should use so that the assembly proceeded with maximum efficiency. Ford also reasoned that he could reduce the time spent on each task if his workers didn't have to move from one assembly to the next. So in 1913, inspired by a grain mill conveyor belt he'd seen, Ford introduced the first moving assembly line for factory production.

Only a year later, Ford surprised everyone when he announced that he would double wages and reduce working hours at his Detroit auto plant. Wall Street investors were dismayed. Media around the world reported Ford's announcement as a philanthropic gesture, or speculated that Ford was trying to create a bigger market for his Model T by creating a new middle-class American workforce. The reality? Ford realized he could lower turnover, and the costs of recruiting and training new employees, by offering better conditions and pay.

Beyond efficiency: Valuing people

When he raised wages and shortened the work day, Ford signaled that employee satisfaction was an essential element of successful management. There was a growing appetite to understand workers in this context and, more than that, to take a sociological or even anthropological viewpoint.

Although sociologists like Emile Durkheim had begun this work in the late 19th century, the backlash against division of labor gained momentum in the 1920s and '30s, when the horrors of the First World War fueled disillusionment with wide-scale mechanization. Many felt that workers were treated as machinery measured by volume of production alone.

In contrast, Elton Mayo highlighted the importance of social ties and a sense of belonging in the workplace. In Mayo's view, managers had to acknowledge these needs and listen to their employees, in order to make workers feel valued.

Mayo's ideas originated in part from his work at the Hawthorne General Electric Plant in Chicago, where he measured the effect of lighting levels on employees at the plant. Mayo found that simply taking an interest in the activities and opinions of staff produced a motivating effect—though when his work concluded and the plant returned to business as usual, productivity dropped.

Although Mayo championed a different kind of dynamic between managers and their subordinates in order to improve conditions and increase output, workers were given no real decision making power. Nevertheless, his work advanced management theory in a significant way, and decades later we can appreciate its influence on the people-oriented, more democratic operation of many modern companies like Semco. Its CEO, TED speaker Ricardo Semler, acknowledges that "it takes a leap of faith about losing control" to reorient a company so that it truly takes care of its people and treats them as its most important asset.

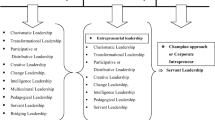

The new leader

As our conception of the workforce changed – from assembly lines of replaceable robots in the era of Fayol and Ford, to individuals with diverse talents to empower (and exploit) today — so has the role of the leader. The command-and-control approach – appropriate and effective in factory-like environments – has given way to newer, more nuanced approaches to leadership that lean more heavily on inspiration and persuasion.

Modern management theorist and TED speaker Simon Sinek believes that great leaders inspire action because they think, act and communicate from 'the inside out'—beginning with and focusing primarily on their core beliefs and values. Sinek suggests that people, whether they're your employees or customers, "don't buy what you do—they buy why you do it." Hiring people who understand and embrace these core beliefs and values, Sinek claims, means they don't work just for a paycheck—they work with "blood and sweat and tears."

When people see their work in this way, the rules and incentives that leaders have leaned on in the past to manage and motivate employees may be unnecessary. In fact, as TED speakers Dan Pink and Barry Schwartz observe, they may actually do harm. Pink shows through a series of surprising experiments that traditional carrot-and-stick motivators like bonuses and pay-for-performance plans can actually decrease creative thinking and employee engagement. What's more, according to Barry Schwartz, these incentives, coupled with an over-reliance on rigid procedures, "cause people to lose morale and the activity to lose morality." Schwartz believes that moral skill, moral will, and practical wisdom are absolutely essential if organizations want to deal with complex challenges in a smart and timely way.

The importance of innovation

Up to now, we've focused on how we organize resources—and in particular, human resources—to complete tasks and meet our goals. However, this alone doesn't equip managers to launch a successful startup to compete in a fast-moving global marketplace, or to keep pace with consumers' changing values, wants and needs. Innovation and marketing are central tenets of modern management, too. How do you harness market knowledge to position yourself as distinctive and essential, and to predict what people will want and use? How can you empower team members to come up with ingenious and elegant ideas?

In an earlier era, innovation often occurred in the first stage of production, which involved creating the product blueprint; innovation may also have altered the production process in order to bring costs down. But today, organizations increasingly aspire toward innovation at all stages, in order to compete and to thrive.

To enable innovation, leaders encourage a diversity of perspectives and empower employees to contribute in unconventional, 'left-field' ways; quite often, this plays out in ways that contradict the chain of command and strict discipline which characterized early management theory. For example, some companies formalize the freedom to experiment with 'left-field' ideas in programs like Google's "20% time" and Apple's "Blue Sky" program; these provide contractual 'free time' for employees to work on their own projects, which the company may later adopt and launch. (It's worth noting that this idea goes as far back as Edison, who encouraged a young Henry Ford to play around with combustion engines in his spare time while Ford worked at Edison's light bulb manufacturing plant.)

Ideas from everywhere: The new "crowd-sourced" workforce and on-call experts

Along with enabling creativity within their teams, in recent years, forward-looking organizations have become more sophisticated in harnessing participation from the public. Through social media platforms, open-source development environments and other collaborative tools, we're increasingly able to amass ideas from around the globe, and from people traditionally considered 'consumers' rather than the 'producers' of our organizations' goods and services.

This signals a profound reversal from Henry Ford's earlier efforts to gather people under one roof around a specific task; rather, as TED speaker Clay Shirky notes, we're now able to take the question or task to the people—who may not be 'employees' as we've traditionally thought of them, and who may never meet us face-to-face in our offices. Shirky predicts that in the coming decades, loosely coordinated groups will be increasingly influential and that "one arena at a time, one institution at a time" more rigidly managed organizations will move towards different and more open methods of management.

The technology that enables crowdsourced solutions also allows leaders to tap 'expert' knowledge from around the world. We have instant access to advice from thought leaders and consultants when we're overwhelmed by the array of information and the pace of innovation in today's world—but then managers must discern what's most helpful to achieve the organization's goals, filtering out what is and isn't useful. What's more, we need to be judicious about when and how we call in the experts: in her TED Talk, Noreena Hertz argues that the constant urge to defer to experts is damaging our ability to think independently and solve our own problems. Indeed, as you make your way through the talks in this TED Study, you'll need to decide for yourself what best applies to you and your team.

All work and no play: The need for balance

Today's technology enables managers and their teams to be connected to the office 24/7, if we want to be, and organizations can draw on workforces from all over the world, at short notice. This creates amazing opportunities and thorny problems for managers. For example, how should a manager interact with employees who may be scattered on several continents, working for multiple employers on several simultaneous projects?

Technology companies developed ways to manage the 'scrum' of work and organize loose networks of employees and stakeholders, in order to coordinate a wide range of activities. Outside the tech sector, these concepts are becoming increasingly central to modern management.

Even in a more standard office environment, the challenges of prioritizing and maintaining efficiency have multiplied. The stereotypical modern open-plan office with its endless meetings and distractions can make the idea of single-minded, creative problem solving seem impossible, as Jason Fried notes in his TED Talk "Why work doesn't happen at work."

It would be difficult to explore the evolution of management without also considering the evolution of work itself. How much work do we actually want to do? And how much are we able to do, before it starts to adversely affect our lives and the organizations we work for?

Striking the right balance between our professional and personal lives is becoming easier and more difficult. For example, our ability to connect to the office 24/7 provides flexibility, but it also means managers and their teams may be tempted—or expected—to put in more hours than ever before. TED speaker Nigel Marsh suggests that workers need to set and enforce their own, individual boundaries, but he doesn't let their employers off the hook: managerial (and organizational) duty of care must come into play. This is a huge societal issue, one that's measured by national governments and critical to our individual health and happiness. But it's not solely an altruistic appeal—for organizations with an eye on productivity, employee engagement and retention, it's simply smart business.

Facebook COO and TED speaker Sheryl Sandberg is particularly interested in the challenges that many women face as they advance in their professions and become wives and mothers. Although many fathers undoubtedly feel these pressures as well, Sandberg notes that by and large it's women who are dropping out of the workforce, and this means that women are all too often conspicuously absent from the top levels of governments, corporations and other organizations. Sandberg asks managers to consider what messages they're sending to the young women in their organizations, and to create ways for all people to engage fully at work so that we benefit from their diverse and valuable perspectives.

Sandberg is candid about her own struggles with work-life balance, and her example is also interesting because it touches on so many of the other issues that we've raised in this introductory essay. Facebook is a company of 7,000 employees working across 15 countries, constantly striving to meet the needs of its more than one billion users and figuring out how to harness the power of that global network. It must continuously innovate to maintain its leadership position as social media proliferate at an amazing rate. Executives like Sandberg must nurture the talent and creative thinking of team members who fuel that innovation—or risk losing them to others who may offer more appealing opportunities.

Get started

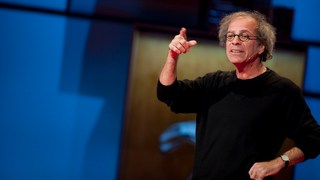

Let's begin Leading Wisely with TED speaker Itay Talgam, who uses a musical metaphor to illuminate the evolution of management and describe different leadership styles in "Lead like the great conductors".

Itay Talgam

Lead like the great conductors, relevant talks.

Simon Sinek

How great leaders inspire action.

The puzzle of motivation

Barry Schwartz

Our loss of wisdom.

Noreena Hertz

How to use experts -- and when not to.

Clay Shirky

Institutions vs. collaboration.

Sheryl Sandberg

Why we have too few women leaders.

Nigel Marsh

How to make work-life balance work.

Jason Fried

Why work doesn't happen at work.

Chip Conley

Measuring what makes life worthwhile.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Management History

Introduction, introductory works.

- Reference Resources

- The Importance of History

- Before Common Era

- Early Common Era

- The Fifteenth–Eighteenth Centuries

- The Industrial Revolution

- Scientific Management and Frederick Taylor

- Other Contributors to Scientific Management

- The Human Side

- Organization Theory

- Theory Integration

- Complexity Revealed

- Developments

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Approaches to Social Responsibility

- Certified B Corporations and Benefit Corporations

- Human Resource Management

- Management In Antiquity

- Management Research during World War II

- Organization Culture

- Organization Development and Change

- Organizational Responsibility

- Research Methods

- Stakeholders

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Corporate Globalization

- Organization Design

- Organizational Learning and Knowledge Transfer

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Management History by David D. Van Fleet LAST REVIEWED: 01 March 2023 LAST MODIFIED: 29 June 2015 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199846740-0008

Although management and attempts to improve it are as old as civilization, the systematic study of management is only just more than one hundred years old. “Management history” refers primarily to the history of management thought as it has developed during that time, although some work covers the practice of management all the way back to Antiquity. Because the events, organizations, economic and social conditions, and even interested scholars are frequently the same, management history overlaps to some extent with related history fields, most notably business history, economic history, and accounting history. Management history utilizes the tools and methods of traditional historical analysis as well as drawing insights from business disciplines and the social sciences. This article includes, first, initial coverage of source material (introductory works, reference sources, and journals), and then presents reasons why history is important and provides a rough chronological presentation of major works for those interested in learning more about management history, from the early practice of management to the evolution of management thought as it has developed during the past one-hundred-plus years.

Some early management books are available online so that students and other scholars can read them in the original form, including Taylor 2010 (cited under Scientific Management and Frederick Taylor ), Sheldon 1924 (cited under Organization Theory ), and Gilbreth 2010 (cited under Other Contributors to Scientific Management ). Many early articles on management may be found in Miner 1995 and Bedeian 2011 . Wren and Bedeian 2008 is the most important management history book, and it is the one most widely used as a primary source in courses on management history. George 1972 , though an older work, is sometimes also recommended.

Bedeian, Arthur G., ed. The Evolution of Management Thought: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management . 4 vols. London: Routledge, 2011.

More than one hundred articles covering more than a century of management literature; a must-read for any serious student of management history.

George, Claude S., Jr. The History of Management Thought . 2d ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1972.

A short, older overview of the development of management thinking that is still useful for the author’s insights.

Miner, John B., ed. Administrative and Management Theory . Aldershot, UK: Dartmouth, 1995.

Numerous articles spanning more than seventy-five years are collected here. Readers get an intimate feel for the evolution of management theory through reading these original articles.

Wren, Daniel A., and Arthur G. Bedeian. The Evolution of Management Thought . 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008.

A highly readable summary of major milestones in the development of management thought. Presented within the context of the times, the stories of major figures in the field are told.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Management »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abusive Supervision

- Adverse Impact and Equal Employment Opportunity Analytics

- Alliance Portfolios

- Alternative Work Arrangements

- Applied Political Risk Analysis

- Assessment Centers: Theory, Practice and Research

- Attributions

- Authentic Leadership

- Bayesian Statistics

- Behavior, Organizational

- Behavioral Approach to Leadership

- Behavioral Theory of the Firm

- Between Organizations, Social Networks in and

- Brokerage in Networks

- Business and Human Rights

- Career Studies

- Career Transitions and Job Mobility

- Charismatic and Innovative Team Leadership By and For Mill...

- Charismatic and Transformational Leadership

- Compensation, Rewards, Remuneration

- Competitive Dynamics

- Competitive Heterogeneity

- Competitive Intensity

- Computational Modeling

- Conditional Reasoning

- Conflict Management

- Considerate Leadership

- Corporate Philanthropy

- Corporate Social Performance

- Corporate Venture Capital

- Counterproductive Work Behavior (CWB)

- Cross-Cultural Communication

- Cross-Cultural Management

- Cultural Intelligence

- Culture, Organization

- Data Analytic Methods

- Decision Making

- Dynamic Capabilities

- Emotional Labor

- Employee Aging

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Ownership

- Employee Voice

- Empowerment, Psychological

- Entrepreneurial Firms

- Entrepreneurial Orientation

- Entrepreneurship

- Entrepreneurship, Corporate

- Entrepreneurship, Women’s

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Faking in Personnel Selection

- Family Business, Managing

- Financial Markets in Organization Theory and Economic Soci...

- Findings, Reporting Research

- Firm Bribery

- First-Mover Advantage

- Fit, Person-Environment

- Forecasting

- Founding Teams

- Global Leadership

- Global Talent Management

- Goal Setting

- Grounded Theory

- Hofstedes Cultural Dimensions

- Human Capital Resource Pipelines

- Human Resource Management, Strategic

- Human Resources, Global

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Work Psychology

- Humility in Management

- Impression Management at Work

- Influence Strategies/Tactics in the Workplace

- Information Economics

- Innovative Behavior

- Intelligence, Emotional

- International Economic Development and SMEs

- International Economic Systems

- International Strategic Alliances

- Job Analysis and Competency Modeling

- Job Crafting

- Job Satisfaction

- Judgment and Decision Making in Teams

- Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration within and across Firm...

- Leader-Member Exchange

- Leadership Development

- Leadership Development and Organizational Change, Coaching...

- Leadership, Ethical

- Leadership, Global and Comparative

- Leadership, Strategic

- Learning by Doing in Organizational Activities

- Management History

- Managerial and Organizational Cognition

- Managerial Discretion

- Meaningful Work

- Multinational Corporations and Emerging Markets

- Neo-institutional Theory

- Neuroscience, Organizational

- New Ventures

- Organization Design, Global

- Organization Research, Ethnography in

- Organizational Adaptation

- Organizational Ambidexterity

- Organizational Behavior, Emotions in

- Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCBs)

- Organizational Climate

- Organizational Control

- Organizational Corruption

- Organizational Hybridity

- Organizational Identity

- Organizational Justice

- Organizational Legitimacy

- Organizational Networks

- Organizational Paradox

- Organizational Performance, Personality Theory and

- Organizational Surveys, Driving Change Through

- Organizations, Big Data in

- Organizations, Gender in

- Organizations, Identity Work in

- Organizations, Political Ideology in

- Organizations, Social Identity Processes in

- Overqualification

- Paternalistic Leadership

- Pay for Skills, Knowledge, and Competencies

- People Analytics

- Performance Appraisal

- Performance Feedback Theory

- Planning And Goal Setting

- Proactive Work Behavior

- Psychological Contracts

- Psychological Safety

- Real Options Theory

- Recruitment

- Regional Entrepreneurship

- Reputation, Organizational Image and

- Research, Ethics in

- Research, Longitudinal

- Research Methods, Qualitative

- Resource Redeployment

- Resource-Dependence Theory

- Response Surface Analysis, Polynomial Regression and

- Role of Time in Organizational Studies

- Safety, Work Place

- Selection, Applicant Reactions to

- Self-Determination Theory for Work Motivation

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy In Management

- Self-Management and Personal Agency

- Sensemaking in and around Organizations

- Service Management

- Shared Team Leadership

- Social Cognitive Theory

- Social Evaluation: Status and Reputation

- Social Movement Theory

- Social Ties and Network Structure

- Socialization

- Sports Settings in Management Research

- Status in Organizations

- Strategic Alliances

- Strategic Human Capital

- Strategy and Cognition

- Strategy Implementation

- Structural Contingency Theory/Information Processing Theor...

- Team Composition

- Team Conflict

- Team Design Characteristics

- Team Learning

- Team Mental Models

- Team Newcomers

- Team Performance

- Team Processes

- Teams, Global

- Technology and Innovation Management

- Technology, Organizational Assessment and

- the Workplace, Millennials in

- Theory X and Theory Y

- Time and Motion Studies

- Training and Development

- Training Evaluation

- Trust in Organizational Contexts

- Unobtrusive Measures

- Virtual Teams

- Whistle-Blowing

- Work and Family: An Organizational Science Overview

- Work Contexts, Nonverbal Communication in

- Work, Mindfulness at

- Workplace Aggression and Violence

- Workplace Coaching

- Workplace Commitment

- Workplace Gossip

- Workplace Meetings

- Workplace, Spiritual Leadership in the

- World War II, Management Research during

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 The History of Management

Learning Objectives

The purpose of this chapter is to:

- 1) Give you an overview of the evolution of management thought and theory.

- 2) Provide an understanding of management in the context of the modern-day world in which we reside.

The History of Management

The concept of management has been around for thousands of years. According to Pindur, Rogers, and Kim (1995), elemental approaches to management go back at least 3000 years before the birth of Christ, a time in which records of business dealings were first recorded by Middle Eastern priests. Socrates, around 400 BC, stated that management was a competency distinctly separate from possessing technical skills and knowledge (Higgins, 1991). The Romans, famous for their legions of warriors led by Centurions, provided accountability through the hierarchy of authority. The Roman Catholic Church was organized along the lines of specific territories, a chain of command, and job descriptions. During the Middle Ages, a 1,000 year period roughly from 476 AD through 1450 AD, guilds, a collection of artisans and merchants provided goods, made by hand, ranging from bread to armor and swords for the Crusades. A hierarchy of control and power, similar to that of the Catholic Church, existed in which authority rested with the masters and trickled down to the journeymen and apprentices. These craftsmen were, in essence, small businesses producing products with varying degrees of quality, low rates of productivity, and little need for managerial control beyond that of the owner or master artisan.

The Industrial Revolution, a time from the late 1700s through the 1800s, was a period of great upheaval and massive change in the way people lived and worked. Before this time, most people made their living farming or working and resided in rural communities. With the invention of the steam engine, numerous innovations occurred, including the automated movement of coal from underground mines, powering factories that now mass-produced goods previously made by hand, and railroad locomotives that could move products and materials across nations in a timely and efficient manner. Factories needed workers who, in turn, required direction and organization. As these facilities became more substantial and productive, the need for managing and coordination became an essential factor. Think of Henry Ford, the man who developed a moving assembly line to produce his automobiles. In the early 1900s, cars were put together by craftsmen who would modify components to fit their product. With the advent of standardized parts in 1908, followed by Ford’s revolutionary assembly line introduced in 1913, the time required to build a Model T fell from days to just a few hours (Klaess, 2020). From a managerial standpoint, skilled craftsmen were no longer necessary to build automobiles. The use of lower-cost labor and the increased production yielded by moving production lines called for the need to guide and manage these massive operations (Wilson, 2015). To take advantage of new technologies, a different approach to organizational structure and management was required.

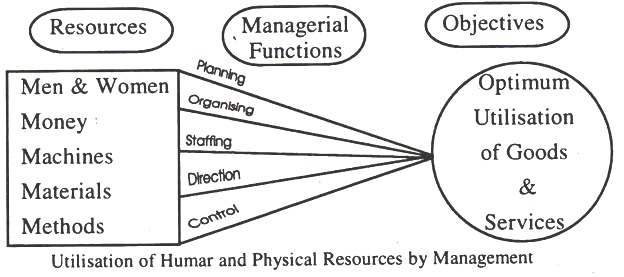

The Scientific Era – Measuring Human Capital

With the emergence of new technologies came demands for increased productivity and efficiency. The desire to understand how to best conduct business centered on the idea of work processes. That is, managers wanted to study how the work was performed and the impact on productivity. The idea was to optimize the way the work was done. One of the chief architects of measuring human output was Frederick Taylor. Taylor felt that increasing efficiency and reducing costs were the primary objectives of management. Taylor’s theories centered on a formula that calculated the number of units produced in a specific time frame (DiFranceso and Berman, 2000). Taylor conducted time studies to determine how many units could be produced by a worker in so many minutes. He used a stopwatch, weight measurement scale, and tape measure to compute how far materials moved and how many steps workers undertook in the completion of their tasks (Wren and Bedeian, 2009). Examine the image below – one can imagine Frederick Taylor standing nearby, measuring just how many steps were required by each worker to hoist a sheet of metal from the pile, walk it to the machine, perform the task, and repeat, countless times a day. Beyond Taylor, other management theorists including Frank and Lilian Gilbreth, Harrington Emerson, and others expanded the concept of management reasoning with the goal of efficiency and consistency, all in the name of optimizing output . It made little difference whether the organization manufactured automobiles, mined coal, or made steel, the most efficient use of labor to maximize productivity was the goal.

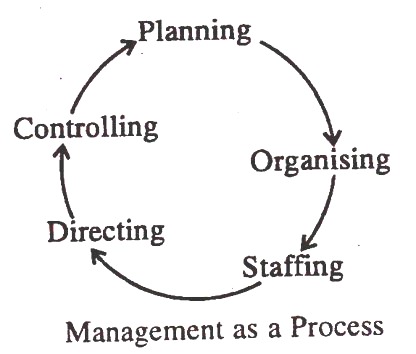

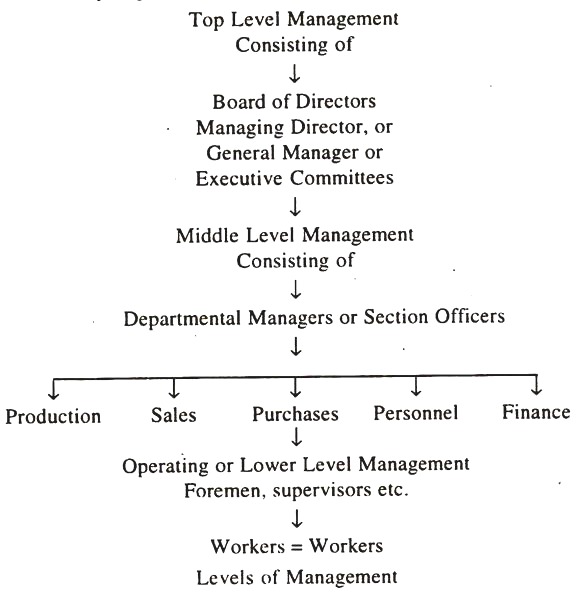

The necessity to manage not just worker output but to link the entire organization toward a common objective began to emerge. Management, out of necessity, had to organize multiple complex processes for increasingly large industries. Henri Fayol, a Frenchman, is credited with developing the management concepts of planning, organizing, coordination, command, and control (Fayol, 1949), which were the precursors of today’s four basic management principles of planning, organizing, leading, and controlling.

Employees and the Organization

With the increased demand for production brought about by scientific measurement, conflict between labor and management was inevitable. The personnel department, forerunner of today’s human resources department, emerged as a method to slow down the demand for unions, initiate training programs to reduce employee turnover, and to acknowledge workers’ needs beyond the factory floor. The idea that to increase productivity, management should factor the needs of their employees by developing work that was interesting and rewarding burst on the scene (Nixon, 2003) and began to be part of management thinking. Numerous management theorists were starting to consider the human factor. Two giants credited with moving management thought in the direction of understanding worker needs were Douglas McGregor and Frederick Herzberg. McGregor’s Theory X factor was management’s assumption that workers disliked work, were lazy, lacked self-motivation, and therefore had to be persuaded by threats, punishment, or intimidation to exert the appropriate effort. His Theory Y factor was the opposite. McGregor felt that it was management’s job to develop work that gave the employees a feeling of self-actualization and worth. He argued that with more enlightened management practices, including providing clear goals to the employees and giving them the freedom to achieve those goals, the organization’s objectives and those of the employees could simultaneously be achieved (Koplelman, Prottas, & Davis, 2008).

Frederick Herzberg added considerably to management thinking on employee behavior with his theory of worker motivation. Herzberg contended that most management driven motivational efforts, including increased wages, better benefits, and more vacation time, ultimately failed because while they may reduce certain factors of job dissatisfaction (the things workers disliked about their jobs), they did not increase job satisfaction. Herzberg felt that these were two distinctly different management problems. Job satisfaction flowed from a sense of achievement, the work itself, a feeling of accomplishment, a chance for growth, and additional responsibility (Herzberg, 1968). One enduring outcome of Herzberg’s work was the idea that management could have a positive influence on employee job satisfaction, which, in turn, helped to achieve the organization’s goals and objectives.

The concept behind McGregor, Herzberg, and a host of other management theorists was to achieve managerial effectiveness by utilizing people more effectively. Previous management theories regarding employee motivation (thought to be directly correlated to increased productivity) emphasized control, specialized jobs, and gave little thought to employees’ intrinsic needs. Insights that considered the human factor by utilizing theories from psychology now became part of management thinking. Organizational changes suggested by management thinkers who saw a direct connection between improved work design, self-actualization, and challenging work began to take hold in more enlightened management theory.

The Modern Era

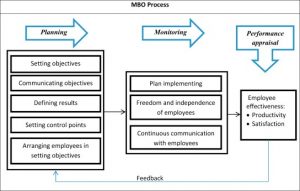

Koontz and O’Donnell (1955) defined management as “the function of getting things done through others (p. 3). One commanding figure stood above all others and is considered the father of modern management (Edersheim, (2007). That individual was Peter Drucker. Drucker, an author, educator, and management consultant is widely credited with developing the concept of Managing By Objective or MBO (Wren & Bedeian, 2009). Management by Objective is the process of defining specific objectives necessary to achieve the organization’s goals. The beauty of the MBO concept was that it provided employees a clear view of their organization’s objectives and defined their individual responsibilities. For example, let’s examine a company’s sales department. One of the firm’s organizational goals might be to grow sales (sometimes referred to as revenue) by 5% the next fiscal year. The first step, in consultation with the appropriate people in the sales department, would be to determine if that 5% goal is realistic and attainable. If so, the 5% sales growth objective is shared with the entire sales department and individuals are assigned specific targets. Let’s assume this is a regional firm that has seven sales representatives. Each sales rep is charged with a specific goal that, when combined with their colleagues, rolls up to the 5% sales increase. The role of management is now to support, monitor, and evaluate performance. Should a problem arise, it is management’s responsibility to take corrective action. If the 5% sales objective is met or exceeded, rewards can be shared. This MBO cycle applies to every department within an organization, large or small, and never-ending.

The MBO Process

Drucker’s contributions to modern management thinking went far beyond the MBO concept. Throughout his long life, Drucker argued that the singular role of business was to create a customer and that marketing and innovation were its two essential functions. Consider the Apple iPhone. From that single innovation came thousands of jobs in manufacturing plants, iPhone sales in stores around the globe, and profits returned to Apple, enabling them to continue the innovation process. Another lasting Drucker observation was that too many businesses failed to ask the question “what business are we in?” (Drucker, 2008, p. 103). On more than one occasion, a company has faltered, even gone out of business, after failing to recognize that their industry was changing or trying to expand into new markets beyond their core competency. Consider the fate of Blockbuster, Kodak, Blackberry, or Yahoo.

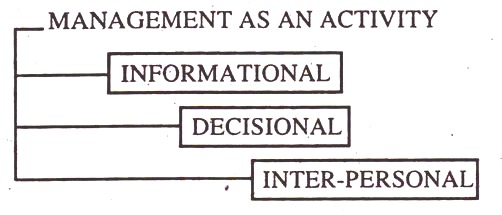

Management theories continued to evolve with additional concepts being put forth by other innovative thinkers. Henry Mintzberg is remembered for blowing holes in the idea that managers were iconic individuals lounging in their offices, sitting back and contemplating big-picture ideas. Mintzberg observed that management was hard work. Managers were on the move attending meetings, managing crises, and interacting with internal and external contacts. Further, depending on the exact nature of their role, managers fulfilled multiple duties including that of spokesperson, leader, resource allocator, and negotiator (Mintzberg, 1973). In the 1970s, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman traveled the globe exploring the current best management practices of the time. Their book, In Search of Excellence, spelled out what worked in terms of managing organizations. Perhaps the most relevant finding was their assertion that culture counts. They found that the best managed companies had a culture that promoted transparency, openly shared information, and effectively managed communication up and down the organizational hierarchy (Allison, 2014). The well managed companies Peterson and Waterman found were built in large part on the earlier managerial ideas of McGregor and Herzberg. Top-notch organizations succeeded by providing meaningful work and positive affirmation of their employees’ worth.

Others made lasting contributions to modern management thinking. Steven Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Successful People , Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline , and Jim Collins and Jerry Porras’s Built to Last are among a pantheon of bestselling books on management principles. Among the iconic thinkers of this era was Michael Porter. Porter, a professor at the Harvard Business School, is widely credited with taking the concept of strategic reasoning to another level. Porter tackled the question of how organizations could effectively compete and achieve a long-term competitive advantage. He contended that there were just three ways a firm could gain such advantage: 1) a cost-based leadership – become the lowest cost producer, 2) valued-added leadership – offer a differentiated product or service for which a customer is willing to pay a premium price, and 3) focus – compete in a niche market with laser-like fixation (Dess & Davis, 1984). Name a company that fits these profiles: How about Walmart for low-cost leadership. For value-added leadership, many think of Apple. Focus leadership is a bit more challenging. What about Whole Foods before being acquired by Amazon? Porter’s thinking on competition and competitive advantage has become timeless principles of strategic management still used today. Perhaps Porter’s most significant contribution to modern management thinking is the connection between a firm’s choice of strategy and its financial performance. Should an organization fail to select and properly execute one of the three basic strategies, it faces the grave danger of being stuck in the middle – its prices are too high to compete based on price or its products lack features unique enough to entice customers to pay a premium price. Consider the fate of Sears and Roebuck, J.C. Penny, K-Mart, and Radio Shack, organizations that failed to navigate the evolving nature of their businesses.

The 21st Century

Managers in the 21st century must confront challenges their counterparts of even a few years ago could hardly imagine. The ever-growing wave of technology, the impact of artificial intelligence, the evolving nature of globalization, and the push-pull tug of war between the firm’s stakeholder and shareholder interests are chief among the demands today’s managers will face.

Much has been written about the exponential growth of technology. It has been reported that today’s iPhone has more than 100,000 times the computing power of the computer that helped land a man on the moon (Kendall, 2019). Management today has to grapple with the explosion of data now available to facilitate business decisions. Data analytics, the examination of data sets, provides information to help managers better understand customer behavior, customer wants and needs, personalize the delivery of marketing messages, and track visits to online web sites. Developing an understanding of how to use data analytics without getting bogged down will be a significant challenge for the 21st century manager. Collecting, organizing, utilizing data in a logical, timely, and cost-effective manner is creating an entirely new paradigm of managerial competence. In addition to data analytics, cybersecurity, drones, and virtual reality are new, exciting technologies and offer unprecedented change to the way business is conducted. Each of these opportunities requires a new degree of managerial competence which, in turn, creates opportunities for the modern-day manager.

Artificial Intelligence

Will robots replace workers? To be sure, this has already happened to some degree in many industries. However, while some jobs will be lost to AI, a host of others will emerge, requiring a new level of management expertise. AI has the ability to eliminate mundane tasks and free managers to focus on the crux of their job. Human skills such as empathy, teaching and coaching employees, focusing on people development and freeing time for creative thinking will become increasingly important as AI continues to develop as a critically important tool for today’s manager.

Globalization

Globalization has been defined as the interdependence of the world’s economies and has been on a steady march forward since the end of World War II. As markets mature, more countries are moving from the emerging ranks and fostering a growing middle class of consumers. This rising new class has the purchasing power to acquire goods and services previously unattainable, and companies around the globe have expanded outside their national borders to meet those demands. Managing in the era of globalization brought a new set of challenges. Adapting to new cultures, navigating the puzzle of different laws, tariffs, import/export regulations, human resource issues, logistics, marketing messages, supply chain management, currency, foreign investment, and government intervention are among the demands facing the 21st century global manager. Despite these enormous challenges, trade among the world’s nations has grown at an unprecedented rate. World trade jumped from around 20% of world GDP in 1960 to almost 60% in 2017.

Trade as a Percent of Global GDP

Despite its stupendous growth, globalization has its share of critics. Chief among them is that globalization has heightened the disparity between the haves and the have-nots in society. Opponents of globalization argue that in many cases, jobs have been lost to developing nations with lower prevailing wage rates. Additionally, inequality has worsened with the wealthiest consuming a disproportionate percent of the world’s resources (Collins, 2015). Proponents counter that on the macro level, globalization creates more jobs than are lost, more people are lifted out of poverty, and expansion globally enables companies to become more competitive on the world stage.

Since the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in 2016 and Great Britain’s decision to exit the European Union, the concept of nationalism has manifested in many nations around the globe. Traditional obstacles to expanding outside one’s home country plus a host of new difficulties such as unplanned trade barriers, blocked acquisitions, and heightened scrutiny from regulators have added to the burdens of managing in the 21st century. The stage has been set for a new generation of managers with the skills to deal with this new, complex business environment. In the 20th century, the old command and control model of management may have worked. However, today, with technology, artificial intelligence, globalization, nationalism, and multiple other hurdles, organizations will continue the move toward a flatter, more agile organizational structure run by managers with the appropriate 21st century skills.

Stakeholder versus Shareholder

What is a stakeholder in a business, and what is a shareholder? The difference is important. Banton (2020) noted that shareholders, by owning even a single share of stock, has a stake in the company. The shareholder first view was put forth by the economist Milton Friedman (1962) who stated that “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud” (p. 133). In other words, maximize profits so long as the pursuit of profit is done so legally and ethically. An alternate view is that a stakeholder has a clear interest in how the company performs, and this interest may stem from reasons other than the increase in the value of their share(s) of stock. Edward Freeman (1999), a philosopher and academic advanced his stakeholder theory contending that the idea was the success of an organization relied on its ability to manage a complex web of relationships with several different stakeholders. These stakeholders could be an employee, a customer, an investor, a supplier, the community in which the firm operates, and the government that collects taxes and stipulates the rules and regulations by which the company must operate. Which theory is correct? According to Emiliani (2001), businesses in the United States typically followed the shareholder model, while in other countries, firms tend to follow the stakeholder model. Events in the past decade have created a shift toward the shareholder model in the United States. The financial crisis of 2008/2009, global warming, the debate between globalization and nationalism, the push for green energy, a spate of natural disasters, and the world-wide impact of health crises such as AIDS, Ebola, the SARS virus and the Coronavirus have fostered a move toward a redefinition of the purpose of a corporation. In the coming decades, those companies that thrive and grow will be the ones that invest in their people, society, and the communities in which they operate. The managers of the 21st century must build on the work of those that proceeded them. Managers in the 21st century would do well if they heeded the words famously used by Isaac Newton who said “If I have seen a little further, it is because I stand on the shoulders of giants” (Harel, 2012).

Critical Thinking Questions

In what way has the role of manager changed in the past twenty years?

With the historical perspective of management in mind, reflect on changes you foresee in the manager’s role in the next 20 years?

Reflect on some of the significant issues you have witnessed in the past few years. Among thoughts to consider are global warming, green energy, global health crisis, globalization, nationalism, national debt, or an issue of your choosing. What role do you see business and management playing in effectively dealing with that specific issue?

How to Answer the Critical Thinking Questions

For each of these answers you should provide three elements.

- General Answer. Give a general response to what the question is asking, or make your argument to what the question is asking.

- Outside Resource. Provide a quotation from a source outside of this textbook. This can be an academic article, news story, or popular press. This should be something that supports your argument. Use the sandwich technique explained below and cite your source in APA in text and then a list of full text citations at the end of the homework assignment of all three sources used.

- Personal Story. Provide a personal story that illustrates the point as well. This should be a personal experience you had, and not a hypothetical. Talk about a time from your personal, professional, family, or school life. Use the sandwich technique for this as well, which is explained below.

Use the sandwich technique:

For the outside resource and the personal story you should use the sandwich technique. Good writing is not just about how to include these materials, but about how to make them flow into what you are saying and really support your argument. The sandwich technique allows us to do that. It goes like this:

Step 1: Provide a sentence that sets up your outside resource by answering who, what, when, or where this source is referring to.

Step 2: Provide the quoted material or story.

Step 3: Tell the reader why this is relevant to the argument you are making.

Allison, S. (2014). An essential book for founders and CEOs: In Search of Excellence. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/scottallison/2014/01/27/an-essential-book-for-founders-and-ceos-in-search-of-excellence/#5a48e7da6c11

Banton, C. (2020). Shareholder vs. stakeholder: An overview. Investopedia. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/08/difference-between-a-shareholder-and-a-stakeholder.asp

Collins, M. (2015). The pros and cons of globalization. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikecollins/2015/05/06/the-pros-and-cons-of-globalization/#609d7a53ccce

Dess, G.G., & Davis, P.S. (1984). Generic strategies as determinants of strategic group membership and organizational performance. The Academy of Management , (27)3, 467-488.

Difrancesco, J.M. & Berman, S.J. (2000). Human productivity: The new American frontier. National Productivity Review. Summer 2000. 29-36.

Drucker, P. F. (2008 ) Management – Revised Edition . New York: Collins Business.

Edersheim, E. (2007). The Definitive Drucker. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Emiliani, M.L. (2001). A mathematical logic approach to the shareholder vs stakeholder debate. Management Decision . (39)8, 618-622.

Fayol, H. (1949). General and Industrial Management . London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons (translated by Constance Storrs).

Freeman, E.R. 91999). Divergent stakeholder theory. The Academy of Management Review , (24)2, pp. 213-236.

Friedman, M, (1962). Capitalism and Freedom , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harel, D. (2012). Standing on the shoulders of a giant. ICALP (International Colloquium on Automation). 16-22. Retrieved from http://www.wisdom.weizmann.ac.il/~/dharel/papers/Standing%20on%20Shoulders.pdf

Herzberg, F. (1968). One more time: How do you motivate employees ? Harvard Business Review, January-February. pp 53-62.

Higgins, J.M. (1991). The Management Challenge: An Introduction to Management . New York: Macmillan

Kendall, G. (2019). Your mobile phone vs. Apollo 11’s guidance computer. Real Clear Science. Retrieved from https://www.realclearscience.com/articles/2019/07/02/your_mobile_phone_vs_apollo_11s_guidance_computer_111026.html

Klaess, J. (2020). The history and future of the assembly line . Tulip . Retrieved from https://tulip.co/blog/manufacturing/assembly-line-history-future/

Koontz, H., & O’Donnell, C. (1955). Principles of Management: An Analysis of Managerial Functions . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kopelman, R.E., Prottas, D.J., & Davis, A.l. (2008). Douglas McGregor’s Theory X and Y: Toward a construct-valid measure. Journal of Managerial Issues , (XX02, 255-271.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The Nature of Managerial Work. In S. Crainer (Ed.). The Ultimate Business Library (pp. 174). West Sussex, UK: Capstone Publishing.

Nixon, L. (2003). Management theories – An historical perspective. Business Date, (11)4, 5-7.

Pindur, W., Rogers, S.E., & Kim, P.S. (1995). The history of management: a global perspective. Journal of Management History , (1) 1, 59-77.

Wilson J.M. (2015). Ford’s development and use of the assembly line, 1908-1927. In Bowden and Lamond (Eds.), Management History. It’s Global Past and Present (71-92). Charlotte, NC: Information Age, Publishing, Inc.

Wren, D.A., & Bedeian, A.G. (2009). The Evolution of Management Thought. Hoboken, NJ. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, NJ

The Four Functions of Management Copyright © 2020 by Dr. Robert Lloyd and Dr. Wayne Aho is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Management →

- 02 Apr 2024

- What Do You Think?

What's Enough to Make Us Happy?

Experts say happiness is often derived by a combination of good health, financial wellbeing, and solid relationships with family and friends. But are we forgetting to take stock of whether we have enough of these things? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Research & Ideas

Employees Out Sick? Inside One Company's Creative Approach to Staying Productive

Regular absenteeism can hobble output and even bring down a business. But fostering a collaborative culture that brings managers together can help companies weather surges of sick days and no-shows. Research by Jorge Tamayo shows how.

- 12 Mar 2024

Publish or Perish: What the Research Says About Productivity in Academia

Universities tend to evaluate professors based on their research output, but does that measure reflect the realities of higher ed? A study of 4,300 professors by Kyle Myers, Karim Lakhani, and colleagues probes the time demands, risk appetite, and compensation of faculty.

- 29 Feb 2024

Beyond Goals: David Beckham's Playbook for Mobilizing Star Talent

Reach soccer's pinnacle. Become a global brand. Buy a team. Sign Lionel Messi. David Beckham makes success look as easy as his epic free kicks. But leveraging world-class talent takes discipline and deft decision-making, as case studies by Anita Elberse reveal. What could other businesses learn from his ascent?

- 16 Feb 2024

Is Your Workplace Biased Against Introverts?

Extroverts are more likely to express their passion outwardly, giving them a leg up when it comes to raises and promotions, according to research by Jon Jachimowicz. Introverts are just as motivated and excited about their work, but show it differently. How can managers challenge their assumptions?

- 05 Feb 2024

The Middle Manager of the Future: More Coaching, Less Commanding

Skilled middle managers foster collaboration, inspire employees, and link important functions at companies. An analysis of more than 35 million job postings by Letian Zhang paints a counterintuitive picture of today's midlevel manager. Could these roles provide an innovation edge?

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

Aggressive cost cutting and rocky leadership changes have eroded the culture at Boeing, a company once admired for its engineering rigor, says Bill George. What will it take to repair the reputational damage wrought by years of crises involving its 737 MAX?

- 16 Jan 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How SolarWinds Responded to the 2020 SUNBURST Cyberattack

In December of 2020, SolarWinds learned that they had fallen victim to hackers. Unknown actors had inserted malware called SUNBURST into a software update, potentially granting hackers access to thousands of its customers’ data, including government agencies across the globe and the US military. General Counsel Jason Bliss needed to orchestrate the company’s response without knowing how many of its 300,000 customers had been affected, or how severely. What’s more, the existing CEO was scheduled to step down and incoming CEO Sudhakar Ramakrishna had yet to come on board. Bliss needed to immediately communicate the company’s action plan with customers and the media. In this episode of Cold Call, Professor Frank Nagle discusses SolarWinds’ response to this supply chain attack in the case, “SolarWinds Confronts SUNBURST.”

- 02 Jan 2024

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 12 Dec 2023

COVID Tested Global Supply Chains. Here’s How They’ve Adapted

A global supply chain reshuffling is underway as companies seek to diversify their distribution networks in response to pandemic-related shocks, says research by Laura Alfaro. What do these shifts mean for American businesses and buyers?

- 05 Dec 2023

What Founders Get Wrong about Sales and Marketing

Which sales candidate is a startup’s ideal first hire? What marketing channels are best to invest in? How aggressively should an executive team align sales with customer success? Senior Lecturer Mark Roberge discusses how early-stage founders, sales leaders, and marketing executives can address these challenges as they grow their ventures in the case, “Entrepreneurial Sales and Marketing Vignettes.”

.jpg)

- 31 Oct 2023

Checking Your Ethics: Would You Speak Up in These 3 Sticky Situations?

Would you complain about a client who verbally abuses their staff? Would you admit to cutting corners on your work? The answers aren't always clear, says David Fubini, who tackles tricky scenarios in a series of case studies and offers his advice from the field.

- 12 Sep 2023

Can Remote Surgeries Digitally Transform Operating Rooms?

Launched in 2016, Proximie was a platform that enabled clinicians, proctors, and medical device company personnel to be virtually present in operating rooms, where they would use mixed reality and digital audio and visual tools to communicate with, mentor, assist, and observe those performing medical procedures. The goal was to improve patient outcomes. The company had grown quickly, and its technology had been used in tens of thousands of procedures in more than 50 countries and 500 hospitals. It had raised close to $50 million in equity financing and was now entering strategic partnerships to broaden its reach. Nadine Hachach-Haram, founder and CEO of Proximie, aspired for Proximie to become a platform that powered every operating room in the world, but she had to carefully consider the company’s partnership and data strategies in order to scale. What approach would position the company best for the next stage of growth? Harvard Business School associate professor Ariel Stern discusses creating value in health care through a digital transformation of operating rooms in her case, “Proximie: Using XR Technology to Create Borderless Operating Rooms.”

- 28 Aug 2023

The Clock Is Ticking: 3 Ways to Manage Your Time Better

Life is short. Are you using your time wisely? Leslie Perlow, Arthur Brooks, and DJ DiDonna offer time management advice to help you work smarter and live happier.

- 15 Aug 2023

Ryan Serhant: How to Manage Your Time for Happiness

Real estate entrepreneur, television star, husband, and father Ryan Serhant is incredibly busy and successful. He starts his days at 4:00 am and often doesn’t end them until 11:00 pm. But, it wasn’t always like that. In 2020, just a few months after the US began to shut down in order to prevent the spread of the Covid-19 virus, Serhant had time to reflect on his career as a real estate broker in New York City, wondering if the period of selling real estate at record highs was over. He considered whether he should stay at his current real estate brokerage or launch his own brokerage during a pandemic? Each option had very different implications for his time and flexibility. Professor Ashley Whillans and her co-author Hawken Lord (MBA 2023) discuss Serhant’s time management techniques and consider the lessons we can all learn about making time our most valuable commodity in the case, “Ryan Serhant: Time Management for Repeatable Success.”

- 08 Aug 2023

The Rise of Employee Analytics: Productivity Dream or Micromanagement Nightmare?

"People analytics"—using employee data to make management decisions—could soon transform the workplace and hiring, but implementation will be critical, says Jeffrey Polzer. After all, do managers really need to know about employees' every keystroke?

- 01 Aug 2023

Can Business Transform Primary Health Care Across Africa?

mPharma, headquartered in Ghana, is trying to create the largest pan-African health care company. Their mission is to provide primary care and a reliable and fairly priced supply of drugs in the nine African countries where they operate. Co-founder and CEO Gregory Rockson needs to decide which component of strategy to prioritize in the next three years. His options include launching a telemedicine program, expanding his pharmacies across the continent, and creating a new payment program to cover the cost of common medications. Rockson cares deeply about health equity, but his venture capital-financed company also must be profitable. Which option should he focus on expanding? Harvard Business School Professor Regina Herzlinger and case protagonist Gregory Rockson discuss the important role business plays in improving health care in the case, “mPharma: Scaling Access to Affordable Primary Care in Africa.”

- 05 Jul 2023

How Unilever Is Preparing for the Future of Work

Launched in 2016, Unilever’s Future of Work initiative aimed to accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization and prepare its workforce for a digitalized and highly automated era. But despite its success over the last three years, the program still faces significant challenges in its implementation. How should Unilever, one of the world's largest consumer goods companies, best prepare and upscale its workforce for the future? How should Unilever adapt and accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization? Is it even possible to lead a systematic, agile workforce transformation across several geographies while accounting for local context? Harvard Business School professor and faculty co-chair of the Managing the Future of Work Project William Kerr and Patrick Hull, Unilever’s vice president of global learning and future of work, discuss how rapid advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automation are changing the nature of work in the case, “Unilever's Response to the Future of Work.”

How Are Middle Managers Falling Down Most Often on Employee Inclusion?

Companies are struggling to retain employees from underrepresented groups, many of whom don't feel heard in the workplace. What do managers need to do to build truly inclusive teams? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 20 Jun 2023

Elon Musk’s Twitter Takeover: Lessons in Strategic Change

In late October 2022, Elon Musk officially took Twitter private and became the company’s majority shareholder, finally ending a months-long acquisition saga. He appointed himself CEO and brought in his own team to clean house. Musk needed to take decisive steps to succeed against the major opposition to his leadership from both inside and outside the company. Twitter employees circulated an open letter protesting expected layoffs, advertising agencies advised their clients to pause spending on Twitter, and EU officials considered a broader Twitter ban. What short-term actions should Musk take to stabilize the situation, and how should he approach long-term strategy to turn around Twitter? Harvard Business School assistant professor Andy Wu and co-author Goran Calic, associate professor at McMaster University’s DeGroote School of Business, discuss Twitter as a microcosm for the future of media and information in their case, “Twitter Turnaround and Elon Musk.”

An Essay about a Philosophical Attitude in Management and Organization Studies Based on Parrhesia

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2023

- Volume 22 , pages 587–618, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jesus Rodriguez-Pomeda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5341-4042 1

1514 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Management and organization studies (MOS) scholarship is at a crossroads. The grand challenges (such as the climate emergency) humankind must face today require an improved contribution from all knowledge fields. The number of academics who criticize the lack of influence and social impact of MOS has recently grown. The scientific field structure of MOS is based on its members’ accumulation of symbolic capital. This structure hinders speaking truth to the elite dominating neoliberal society. Our literature review suggested that a deeper interaction between MOS and philosophy could aid in improving the social impact of MOS. Specifically, an attitude by MOS scholars based on parrhesia (παρρησíα, to speak truth to power) could revitalize the field through heterodox approaches and, consequently, allow them to utter sound criticisms of the capitalist system. Parrhesia would lead MOS scholars towards a convergence of ethics and politics. We investigate whether daring to speak inconvenient truths to the powerful (some peers in the field and some individuals and corporations in society) can be a straightforward tool for revitalizing MOS. Boosting a candid philosophy-MOS interaction requires the fulfilment of three objectives: practical dialogue between these fields, reconsideration of the fields’ structures based on symbolic capital, and a post-disciplinary approach to philosophy. That fulfilment implies the delimitation of the MOS-philosophy interaction, a respectful mutual framework, mutual curiosity, and moving from prescriptive theoretical reflection towards more socially useful MOS. Ethical betterment through parrhesia could be the key to surpassing MOS stagnation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Implementation: A Review and a Research Agenda Towards an Integrative Framework

Tahniyath Fatima & Said Elbanna

A critical analysis of Elon Musk’s leadership in Tesla motors

Md. Rahat Khan

A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility

Mauricio Andrés Latapí Agudelo, Lára Jóhannsdóttir & Brynhildur Davídsdóttir

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Management and organization studies (MOS) suffer from a growing disconnection with the great contemporary problems voiced by many authors who advocate a new academic practice for increasing the discipline’s social impact. MOS do not quickly adapt to emerging social needs. Like other disciplines, MOS are structured as a scientific field. Some egocentric academic interests pursue the accumulation of symbolic capital by each academic (Bourdieu 1975 , 1984 ). The field is hierarchized based on the symbolic capital each scholar possesses. Those occupying high positions in the field are legitimized to establish research agendas and distribute resources. The “Matthew effect” (Merton 1968 , 1988 ) reinforces the power of these people, further increasing their symbolic capital.

Therefore, rebalancing the ethical and political approaches of MOS academics would mitigate the centralized control of scientific activity related to the stagnation of MOS. The aim would be “to rebuild an environment in which the selfless search for truth and knowledge is once again enshrined as the central purpose of academic life” (Tourish 2019 : 251). The truth (and its practice) appears at the confluence between ethics and politics. Consequently, parrhesia can contribute to overcoming the limitations representing established practices and ideas in every scientific field (including MOS). Moreover, parrhesia, in deviating from the doxa, can spread innovative ideas. Indeed, parrhesia requires courage to produce ideas that challenge the status quo.

Remarkably, the power exercised by scientific authorities is projected through their control over publications in academic journals. They define the prevalent metrics of symbolic capital (and, consequently, those determining the scientific authority of each academic) based on the number of publications and citations in high-ranked journals. Consequently, the current problem of MOS has an external manifestation (decrease in its social impact compared to other fields in a world defined by the so-called “grand challenges”) and an internal one (scientific sclerotization preventing adequate reaction to external changes). In this essay, we propose a revitalization of MOS by spreading an ethical attitude based on parrhesia among its academics. The aim is to develop an internal dynamic for MOS that guarantees the search for truth, democratizes the field, and allows it to recover lost scientific rigour. Therefore, MOS scholars should reconsider their attitudes and scientific procedures.

Such attitudes and procedures have—on occasion—several flaws, such as “questionable research practices” (QRPs), including data fraud, plagiarism, self-plagiarism, p-hacking (inappropriate null hypothesis analysis), and HARKing (hypothesizing after test results are known) (Tourish 2019 ). Certain consequences of some of these defects have been observed since the late 1950s: greater fragmentation of the field together with an exaggerated emphasis on research methodology involving the exclusion of validity or relevance (Starbuck 2003 : 442).

MOS could thus use the talent of all their members (not only those with the highest scientific authority) to effectively contribute (along with other fields) to overcoming the “grand challenges”. “Grand challenges” are “formulations of global problems that can be plausibly addressed through coordinated and collaborative effort.” (George et al. 2016 : 1880). Considering the huge damaging effects of inadequate treatment of these challenges, it is advisable to adopt a prudent, precautionary approach to them. Additionally, some of those challenges (such as the climate emergency) will affect further generations.Thus, careful ethical considerations by present generations will avoid irreversible effects for newcomers.

Such a contribution requires MOS members to behave outwardly as parrhesiastes; this implies the same courage in defending the truth as they must use inwardly. The reason is clear: the “grand challenges” derive from the neoliberal economic system currently dominating the world and run by an elite (individuals and corporations) acting exclusively in their own interests. Therefore, parrhesia represents a link between the ethics of MOS academics and the political spheres in which they operate (within the scientific field and externally in society overall).

Consequently, revitalizing the philosophical perspective at the origins of MOS (Jones and ten Bos, 2007a ; Mir and Greenwood, 2022 )would allow its scholars to integrate its ethical premises more deeply with the political effects of their work. The philosophical perspective is not new in MOS since these studies have been considering ideas from epistemology or ethics, among other fields. However, ironically, ethics has been considered more as an object of study within organizational activities than as a crucial element in reflecting on the development of the scientific field.

MOS researchers’ freedom and responsibility reinforce the crucial importance of their professional ethics (Tsui and McKiernan 2022 ). A scientific practice based on deeper integration of ethics and politics would improve the contribution of MOS to solving the problems afflicting contemporary societies. Therefore, an ethic of speaking the truth, even if this means confronting the powerful, would help stop any temptation to complacency. Indeed, MOS academics are responsible for criticizing everything that delays the advancement of knowledge, both in an epistemological sense and in social practice.

In addition to the presence of philosophy in the origins of MOS, the need to revitalize the philosophical attitude of MOS academics is explained by two other arguments: all scientific activity has ontological, ethical, and epistemological roots, and, like any activity developed in society, it has political consequences.

In our view, increasing the interaction between MOS and philosophy activities would require—among others—achieving three objectives: exploring a practical dialogue between philosophers and MOS scholars, reconsidering the dynamics of symbolic capital accumulation in both fields, and facilitating the transmission of ideas from the philosophy through its “de-disciplination” (Frodeman 2013 ).

Firstly, through a practical dialogue with contemporary philosophers (especially those concerned with social ontology), MOS authors could benefit from a richer and deeper perspective on contemporary humans and societies. After a short review of the present MOS situation in Sect. 2, we address the four premises for building such a dialogue in the following sections of this essay.

Secondly, overcoming the current dynamics of symbolic capital accumulation in MOS could increase interactions among its scholars (regardless of each other’s symbolic capital) on a more egalitarian and candid basis. This increase (in quantity and quality) in interactions between all types of MOS scholars would probably generate new ideas and scientific approaches. Thus, the relevance and social utility of MOS would grow.

The “de-disciplining” of philosophy concerns philosophers. An interesting effort originates from the so-called “field philosophy”: an engagement with “our common lives” driven by improvisation, non-standard methodologies, working within interdisciplinary teams, focusing on the specificities of actual problems, and adjusting rigour and results to the team partners’ requirements (Brister and Frodeman, eds., 2020 ).

In this regard, for Frodeman ( 2013 : 1935):

Philosophy, and the humanities generally, should never have become disciplines. (…). A merely disciplined philosophy, where philosophers primarily work with and write for other philosophers, is in the end no philosophy at all.

Adopting a philosophical approach in a sufficiently large group of MOS scholars could lead them to use practices such as parrhesia, which externalize ethical reflection towards a political framework.

This call to renew the ethical commitment of MOS scholars also includes recovering and updating the discipline’s philosophical roots since this ethical commitment requires rethinking the discipline’s ontological and epistemological dimensions. Determining what the existing organizations are, how they interact with new societies, and how to understand them is essential in the current critical moment.