What is Claim? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Claim definition.

A claim (KLAYM) in literature is a statement in which a writer presents an assertion as truthful to substantiate an argument. A claim may function as a single argument by itself, or it may be one of multiple claims made to support a larger argument.

Nonfiction writers use claims to state their own views or the views of others, while fiction writers and playwrights use claims to present the views of their characters or narrators. Claims are more than opinions; you can back a claim up with evidence, while an opinion is simply something you feel is truthful or accurate.

The literary definition of the word claim —as maintaining something to be true—was first utilized in the 1860s, though the Century Dictionary of 1895 called it an “inelegant” term. The word comes from the Latin clamare , meaning “to cry, shout, or call out.”

Types of Claims

There are several types of claims. These are some of the most common that appear in literature:

An evaluative claim, or value judgement, assesses an idea from either an ethical or aesthetic viewpoint.

An ethical evaluative claim comments on the morality or principles—or lack thereof—of a person, idea, or action. For example, in East of Eden , John Steinbeck writes, “As a child may be born without an arm, so one may be born without kindness or the potential of conscience.” This is a value judgement about the lack of ethics that plague the character of Cathy.

An aesthetic evaluative claim judges the artistic merits of the claim subject. Critics often make these types of claims when writing reviews and analyses of creative works.

Interpretative

An interpretative claim explains or illuminates the overall argument the writer is attempting to make. On a basic level, a simple book report is a type of interpretative claim; you present your own understanding of the text, how it conveys meaning, and your interpretation of the larger points the author makes.

A factual claim argues an accepted truth about reality. Verifiable information can support these claims. In A Quick Guide to Cancer Epidemiology , authors Paolo Boffetta, Stefania Boccia, and Carlo La Vecchia write, “Tobacco smoking is the main single cause of human cancer worldwide and the largest cause of death and disease.” This is a factual claim backed up by years of research and scientific evidence.

A policy claim tries to compel a reader—usually, a politician or governing body—to take a specific action or change a law or viewpoint. These types of claims are common in politically and socially focused nonfiction. For instance, in the book Dead Man Walking , Sister Helen Prejean reflects on her friendship with a death-row inmate and other pivotal events that shaped her opposition to the death penalty; the book relies on policy claims to challenge the government’s position on capital punishment.

The Function of Claims

The purpose of a claim is to convince a reader of something. The reader may not initially agree with the statement the author makes or may require more information to reach their own conclusion, and claims point them in the direction of a specific answer. If a reader already agrees with an author’s claim, the information presented only underscores the reader’s conviction and supports their viewpoint. All kinds of literature depend on claims to keep stories engaging, add complexity and depth to characterizations , and establish the author’s unique perspective on the subjects addressed.

Claims in Rhetoric

A claim in rhetoric is a statement that the speaker asks the audience to accept. A claim, by nature, is arguable, meaning listeners could conceivably object to the claim the speaker makes. Rhetorical claims reside somewhere between opinions and widely accepted truths. They are more substantial than mere beliefs, but they typically aren’t universally understood as facts.

Claims Outside of Literature

The advertising and marketing worlds rely heavily on claims to sell products and services. Claims are largely concerned with persuasion , convincing target audiences to respond in certain ways, so they go hand in hand with advertising. For instance, Trident gum once used the factual claim that “four out of five dentists recommended sugarless gum for their patients who chew gum,” which compelled viewers to purchase Trident.

Claims are also common in academia. A professor might use a claim to explain a subject in more detail. A student undertaking an academic writing assignment will utilize a claim as the main argument of their essay or a series of claims to back up a larger argument.

Public speakers often use claims to persuade and inspire audiences. They typically make dramatic claims to rouse emotion in the listener and paint vivid mental imagery , all in service of a greater argument. In Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, for instance, King imagines a bleak future if Black Americans do not obtain basic civil rights and liberties:

One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

Examples of Claims in Literature

1. Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

Lee’s classic novel charts Scout Finch’s coming of age amid racial tensions in the Deep South. Scout’s father, Atticus, makes the claim that killing a mockingbird is a sin, a claim that Scout’s friend Miss Maudie further substantiates:

“Remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” That was the only time I ever heard Atticus say it was a sin to do something, and I asked Miss Maudie about it.

“Your father’s right,” she said. “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy . . . but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

This is an evaluative claim, as it highlights an ethical argument suggesting that mockingbirds only contribute good to the world and do not deserve killing.

2. Roxane Gay, “The Solace of Preparing Fried Foods and Other Quaint Remembrances from 1960s Mississippi: Thoughts on The Help ”

Gay’s 2011 essay, which originally appeared on The Rumpus and was later included in her essay collection Bad Feminist , includes numerous evaluative claims about the aesthetic value of the movie The Help :

The Help is billed as inspirational, charming and heart warming. That’s true if your heart is warmed by narrow, condescending, mostly racist depictions of black people in 1960s Mississippi, overly sympathetic depictions of the white women who employed the help , the excessive, inaccurate use of dialect, and the glaring omissions with regards to the stirring Civil Rights Movement in which, as Martha Southgate points out, in Entertainment Weekly , “…white people were the help,” and were “the architects, visionaries, prime movers, and most of the on-the-ground laborers of the civil rights movement were African-American.” The Help , I have decided, is science fiction, creating an alternate universe to the one we live in.

Gay also offers interpretative claims by discussing the key events in the movie and how the filmmakers present these events.

3. Maggie Smith, “Good Bones”

In her 2016 poem, Smith grapples with how she will present a broken world to her children and how she will inspire them to improve it:

…Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children. I am trying

to sell them the world. Any decent realtor,

walking you through a real sh*thole, chirps on

about good bones: This place could be beautiful,

right? You could make this place beautiful.

Smith makes several evaluative claims of an ethical nature, such as the world being “half-terrible” and the existence of strangers “who would break you.” She also makes a factual claim in the simple statement that “Life is short”; though lifespans grow with each passing generation, in the grand scheme of planetary time, life is, indeed, short.

Further Resources on Claims

The Odegaard Writing & Research Center at the University of Washington examines claims and counterclaims in academic writing .

Jeffrey Schrank delves into the language of advertising claims .

W.W. Norton offers insights into interpretative versus evaluative claims in literary essays .

Related Terms

- Characterization

- Perspective

What Is a Claim in an Essay? Read This Before Writing

What is a claim in an essay?

In this article, you’ll find the essay claim definition, characteristics, types, and examples. Let’s learn where to use claims and how to write them.

Get ready for up-to-date and practical information only!

What Is a Claim in Writing?

A claim is the core argument defining an essay’s goal and direction. (1) It’s assertive, debatable, and supported by evidence. Also, it is complex, specific, and detailed.

Also known as a thesis, a claim is a little different from statements and opinions. Keep reading to reveal the nuances.

Claims vs. statements vs. opinions

Where to use claims.

To answer the “What is claim in writing?”, it’s critical to understand that this definition isn’t only for high school or college essays. Below are the types of writing with claims:

- Argumentative articles. Consider a controversial issue, proving it with evidence throughout your paper.

- Literary analysis. Build a claim about a book , and use evidence from it to support your claim.

- Research papers. Present a hypothesis and provide evidence to confirm or refute it.

- Speeches. State a claim and persuade the audience that you’re right.

- Persuasive essays and memos. State a thesis and use fact-based evidence to back it up..

What can you use as evidence in essays?

- Facts and other data from relevant and respectful resources (no Wikipedia or other sources like this)

- Primary research

- Secondary research (science magazines’ articles, literature reviews, etc.)

- Personal observation

- Expert quotes (opinions)

- Info from expert interviews

How to Write a Claim in Essays

Two points to consider when making a claim in a college paper:

First, remember that a claim may have counterarguments. You’ll need to respond to them to make your argument stronger. Use transition words like “despite,” “yet,” “although,” and others to show those counterclaims.

Second, good claims are more complex than simple “I’m right” statements. Be ready to explain your claim, answering the “So what?” question.

And now, to details:

Types of claims in an essay (2)

Writing a claim: details to consider.

What makes a good claim? Three characteristics (3):

- It’s assertive. (You have a strong position about a topic.)

- It’s specific. (Your assertion is as precise as possible.)

- It’s provable. (You can prove your position with evidence.)

When writing a claim, avoid generalizations, questions, and cliches. Also, don’t state the obvious.

- Poor claim: Pollution is bad for the environment.

- Good claim: At least 25% of the federal budget should be spent upgrading businesses to clean technologies and researching renewable energy sources to control or cut pollution.

How to start a claim in an essay?

Answer the essay prompt. Use an active voice when writing a claim for readers to understand your point. Here is the basic formula:

When writing, avoid:

- First-person statements

- Emotional appeal

- Cluttering your claim with several ideas; focus on one instead

How long should a claim be in an essay?

1-2 sentences. A claim is your essay’s thesis: Write it in the first paragraph (intro), presenting a topic and your position about it.

Examples of Claims

Below are a few claim examples depending on the type. I asked our expert writers to provide some for you to better understand how to write it.

Feel free to use them for inspiration, or don’t hesitate to “steal” if they appear relevant to your essay topic. Also, remember that you can always ask our writers to assist with a claim for your papers.

Final Words

Now that you know what is a claim in an essay, I hope you don’t find it super challenging to write anymore. It’s like writing a thesis statement; make it assertive, specific, and provable.

If you still have questions or doubts, ask Writing-Help writers for support. They’ll help you build an A-worthy claim for an essay.

References:

- https://www.pvcc.edu/files/making_a_claim.pdf

- https://lsa.umich.edu/content/dam/sweetland-assets/sweetland-documents/teachingresources/TeachingArgumentation/Supplement2_%20SixCommonTypesofClaim.pdf

- https://students.tippie.uiowa.edu/sites/students.tippie.uiowa.edu/files/2022-05/effective_claims.pdf

- Essay samples

- Essay writing

- Writing tips

Recent Posts

- Writing the “Why Should Abortion Be Made Legal” Essay: Sample and Tips

- 3 Examples of Enduring Issue Essays to Write Yours Like a Pro

- Writing Essay on Friendship: 3 Samples to Get Inspired

- How to Structure a Leadership Essay (Samples to Consider)

- What Is Nursing Essay, and How to Write It Like a Pro

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

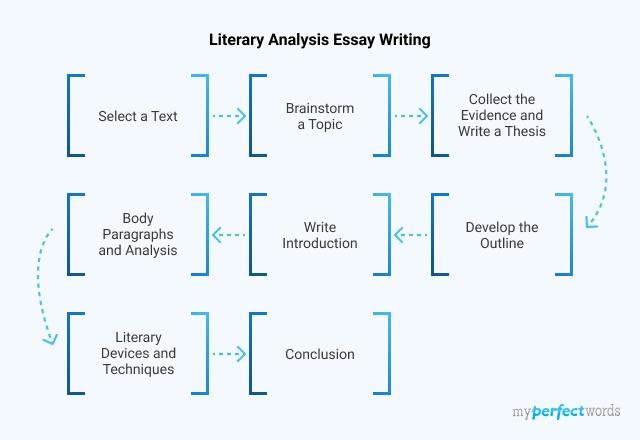

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.

You may, of course, modify the template that is presented here. Your instructor might favour a somewhat different approach to literary analysis. Its essence, though, will be your understanding and interpretation of the theme of the poem, story, or play and the skill with which the author shapes the elements of literature—plot, character, form, diction, setting, point of view—to support the theme.

Academic Writing Tips : How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper. Authored by: eHow. Located at: https://youtu.be/8adKfLwIrVk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

BC Open Textbooks: English Literature Victorians and Moderns: https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/back-matter/appendix-5-writing-an-analysis-of-a-poem-story-and-play/

Literary Analysis

The challenges of writing about english literature.

Writing begins with the act of reading . While this statement is true for most college papers, strong English papers tend to be the product of highly attentive reading (and rereading). When your instructors ask you to do a “close reading,” they are asking you to read not only for content, but also for structures and patterns. When you perform a close reading, then, you observe how form and content interact. In some cases, form reinforces content: for example, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, where the speaker invites God’s “force” “to break, blow, burn and make [him] new.” Here, the stressed monosyllables of the verbs “break,” “blow” and “burn” evoke aurally the force that the speaker invites from God. In other cases, form raises questions about content: for example, a repeated denial of guilt will likely raise questions about the speaker’s professed innocence. When you close read, take an inductive approach. Start by observing particular details in the text, such as a repeated image or word, an unexpected development, or even a contradiction. Often, a detail–such as a repeated image–can help you to identify a question about the text that warrants further examination. So annotate details that strike you as you read. Some of those details will eventually help you to work towards a thesis. And don’t worry if a detail seems trivial. If you can make a case about how an apparently trivial detail reveals something significant about the text, then your paper will have a thought-provoking thesis to argue.

Common Types of English Papers Many assignments will ask you to analyze a single text. Others, however, will ask you to read two or more texts in relation to each other, or to consider a text in light of claims made by other scholars and critics. For most assignments, close reading will be central to your paper. While some assignment guidelines will suggest topics and spell out expectations in detail, others will offer little more than a page limit. Approaching the writing process in the absence of assigned topics can be daunting, but remember that you have resources: in section, you will probably have encountered some examples of close reading; in lecture, you will have encountered some of the course’s central questions and claims. The paper is a chance for you to extend a claim offered in lecture, or to analyze a passage neglected in lecture. In either case, your analysis should do more than recapitulate claims aired in lecture and section. Because different instructors have different goals for an assignment, you should always ask your professor or TF if you have questions. These general guidelines should apply in most cases:

- A close reading of a single text: Depending on the length of the text, you will need to be more or less selective about what you choose to consider. In the case of a sonnet, you will probably have enough room to analyze the text more thoroughly than you would in the case of a novel, for example, though even here you will probably not analyze every single detail. By contrast, in the case of a novel, you might analyze a repeated scene, image, or object (for example, scenes of train travel, images of decay, or objects such as or typewriters). Alternately, you might analyze a perplexing scene (such as a novel’s ending, albeit probably in relation to an earlier moment in the novel). But even when analyzing shorter works, you will need to be selective. Although you might notice numerous interesting details as you read, not all of those details will help you to organize a focused argument about the text. For example, if you are focusing on depictions of sensory experience in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” you probably do not need to analyze the image of a homeless Ruth in stanza 7, unless this image helps you to develop your case about sensory experience in the poem.

- A theoretically-informed close reading. In some courses, you will be asked to analyze a poem, a play, or a novel by using a critical theory (psychoanalytic, postcolonial, gender, etc). For example, you might use Kristeva’s theory of abjection to analyze mother-daughter relations in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. Critical theories provide focus for your analysis; if “abjection” is the guiding concept for your paper, you should focus on the scenes in the novel that are most relevant to the concept.

- A historically-informed close reading. In courses with a historicist orientation, you might use less self-consciously literary documents, such as newspapers or devotional manuals, to develop your analysis of a literary work. For example, to analyze how Robinson Crusoe makes sense of his island experiences, you might use Puritan tracts that narrate events in terms of how God organizes them. The tracts could help you to show not only how Robinson Crusoe draws on Puritan narrative conventions, but also—more significantly—how the novel revises those conventions.

- A comparison of two texts When analyzing two texts, you might look for unexpected contrasts between apparently similar texts, or unexpected similarities between apparently dissimilar texts, or for how one text revises or transforms the other. Keep in mind that not all of the similarities, differences, and transformations you identify will be relevant to an argument about the relationship between the two texts. As you work towards a thesis, you will need to decide which of those similarities, differences, or transformations to focus on. Moreover, unless instructed otherwise, you do not need to allot equal space to each text (unless this 50/50 allocation serves your thesis well, of course). Often you will find that one text helps to develop your analysis of another text. For example, you might analyze the transformation of Ariel’s song from The Tempest in T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land. Insofar as this analysis is interested in the afterlife of Ariel’s song in a later poem, you would likely allot more space to analyzing allusions to Ariel’s song in The Waste Land (after initially establishing the song’s significance in Shakespeare’s play, of course).

- A response paper A response paper is a great opportunity to practice your close reading skills without having to develop an entire argument. In most cases, a solid approach is to select a rich passage that rewards analysis (for example, one that depicts an important scene or a recurring image) and close read it. While response papers are a flexible genre, they are not invitations for impressionistic accounts of whether you liked the work or a particular character. Instead, you might use your close reading to raise a question about the text—to open up further investigation, rather than to supply a solution.

- A research paper. In most cases, you will receive guidance from the professor on the scope of the research paper. It is likely that you will be expected to consult sources other than the assigned readings. Hollis is your best bet for book titles, and the MLA bibliography (available through e-resources) for articles. When reading articles, make sure that they have been peer reviewed; you might also ask your TF to recommend reputable journals in the field.

Harvard College Writing Program: https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/files/hwp/files/bg_writing_english.pdf

In the same way that we talk with our friends about the latest episode of Game of Thrones or newest Marvel movie, scholars communicate their ideas and interpretations of literature through written literary analysis essays. Literary analysis essays make us better readers of literature.

Only through careful reading and well-argued analysis can we reach new understandings and interpretations of texts that are sometimes hundreds of years old. Literary analysis brings new meaning and can shed new light on texts. Building from careful reading and selecting a topic that you are genuinely interested in, your argument supports how you read and understand a text. Using examples from the text you are discussing in the form of textual evidence further supports your reading. Well-researched literary analysis also includes information about what other scholars have written about a specific text or topic.

Literary analysis helps us to refine our ideas, question what we think we know, and often generates new knowledge about literature. Literary analysis essays allow you to discuss your own interpretation of a given text through careful examination of the choices the original author made in the text.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Claim Definition

A statement essentially arguable, but used as a primary point to support or prove an argument is called a claim. If somebody gives an argument to support his position, it is called “making a claim.” Different reasons are usually presented to prove why a certain point should be accepted as logical. A general model is given below to explain the steps followed in making a claim:

Premise 1 Premise 2 Premise 3 … Premise N Therefore, Conclusion

In this model, the symbol and the dots before it signify that the number of premises used for proving an argument may vary. The word “therefore” shows that the conclusion will be restating the main argument, which was being supported all the way through.

With the help of a claim, one can express a particular stance on an issue that is controversial, so as to verify it as a logically sound idea. In case of a complex idea, it is always wise to start by classifying the statements you are about to put forward. Many times, the claims you make stay unnoticed because of the complex sentence structure; specifically, where the claims and their grounds are intertwined. However, a rhetorical performance, such as a speech or an essay , is typically made up of a single central claim, and most of the content contains several supporting arguments for that central claim.

Types of Claim

There are many types of claim used in literature, and all of them have their own significance. The type that we will be discussing here has great importance in writing and reading about literature because it is used frequently to build arguments. It is called evaluative claim .

Evaluative claims involve the assessment or judgment of the ideas in the original piece. They have been divided further into two types: ethical judgment and aesthetic judgment. As the name implies, aesthetic judgment revolves around deciding whether or not a piece of writing fulfills artistic standards.

You can easily find evaluative claim examples in book reviews. This type is about assessing an argument, or the entire essay on ethical, social, political, and philosophical grounds, and determining whether an idea is wise, good, commendable, and valid. The evaluative and interpretive claims typically consist of well-versed viewpoints. Where interpretive claims strive to explain or clarify the views communicated in and by the text, evaluative claims study the validity of those views by drawing comparison between them and the writer’s own opinions.

Claim Examples

Interpretive claims, example #1: animal farm (by george orwell).

The great thing about Animal Farm by George Orwell is that it has presented all animals equal in the eyes of the laws framed by them. They framed Ten Commandments when they expelled Mr. Jones from Manor Farm, and this rule, “ All animals are equal ,” became a shibboleth for them.

This interpretive claim presents an argument about the exploration of the meanings, and the evidence that is given within quotation marks has been interpreted as well.

Similarly, “To be or not to be…” is an evidence of the excessive thinking of Prince Hamlet in the play Hamlet , written by William Shakespeare . If a person interprets the play, he has evidence to support his claim. Papers on literary analysis are treasure troves of examples of claim.

Evaluative Claims

Example #2: animal farm (by george orwell).

As the majority of the animals were in the process of framing rules, it was understood that, although rats and several other animals were not present, whatsoever had four legs is an animal, and therefore is equal to any other animal. Hence, a general rule was framed that whatever walks on four legs is good. Later on, birds (having two wings and two legs) and other non-four-legged animals were also considered as animals. Therefore, all are equal.

Now this argument clearly shows the judgment given at the end, but it is after evaluation of the whole situation presented in the novel . This is called evaluative claim.

Function of Claim

The role of claims in writing any narrative or script is essential. If used correctly, they can strengthen the argument of your standpoint. The distinction between different types of claim can be highly confusing, and sometimes complicated. For instance, a composition that claims that Vogel’s play gives out a socially and ethically impolite message about abuse, can also assert that the play is aesthetically flawed. A composition that goes on developing and advocating an interpretive claim about another script shows that it at least deserves philosophical or aesthetical interpretation. On the other hand, developing an evaluative claim about a composition always remains in need of a certain level of interpretation.

Hence, the dissimilarities are subtle, and can only be identified after close and profound observation; but all things considered, they are important. Thus, lest it is suggested you do otherwise, you must always leave the evaluative claims for conclusions, and make your essay an interpretive claim.

Post navigation

Literary Analysis Essay Writing

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline - A Step By Step Guide

People also read

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay - A Step-by-Step Guide

Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics & Ideas

Have you ever felt stuck, looking at a blank page, wondering what a literary analysis essay is? You are not sure how to analyze a complicated book or story?

Writing a literary analysis essay can be tough, even for people who really love books. The hard part is not only understanding the deeper meaning of the story but also organizing your thoughts and arguments in a clear way.

But don't worry!

In this easy-to-follow guide, we will talk about a key tool: The Literary Analysis Essay Outline.

We'll provide you with the knowledge and tricks you need to structure your analysis the right way. In the end, you'll have the essential skills to understand and structure your literature analysis better. So, let’s dive in!

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

- 1. How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

- 2. Literary Analysis Essay Format

- 3. Literary Analysis Essay Outline Example

- 4. Literary Analysis Essay Topics

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

An outline is a structure that you decide to give to your writing to make the audience understand your viewpoint clearly. When a writer gathers information on a topic, it needs to be organized to make sense.

When writing a literary analysis essay, its outline is as important as any part of it. For the text’s clarity and readability, an outline is drafted in the essay’s planning phase.

According to the basic essay outline, the following are the elements included in drafting an outline for the essay:

- Introduction

- Thesis statement

- Body paragraphs

A detailed description of the literary analysis outline is provided in the following section.

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction

An introduction section is the first part of the essay. The introductory paragraph or paragraphs provide an insight into the topic and prepares the readers about the literary work.

A literary analysis essay introduction is based on three major elements:

Hook Statement: A hook statement is the opening sentence of the introduction. This statement is used to grab people’s attention. A catchy hook will make the introductory paragraph interesting for the readers, encouraging them to read the entire essay.

For example, in a literary analysis essay, “ Island Of Fear,” the writer used the following hook statement:

“As humans, we all fear something, and we deal with those fears in ways that match our personalities.”

Background Information: Providing background information about the chosen literature work in the introduction is essential. Present information related to the author, title, and theme discussed in the original text.

Moreover, include other elements to discuss, such as characters, setting, and the plot. For example:

“ In Lord of the Flies, William Golding shows the fears of Jack, Ralph, and Piggy and chooses specific ways for each to deal with his fears.”

Thesis Statement: A thesis statement is the writer’s main claim over the chosen piece of literature.

A thesis statement allows your reader to expect the purpose of your writing. The main objective of writing a thesis statement is to provide your subject and opinion on the essay.

For example, the thesis statement in the “Island of Fear” is:

“...Therefore, each of the three boys reacts to fear in his own unique way.”

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Literary Analysis Essay Body Paragraphs

In body paragraphs, you dig deep into the text, show your insights, and build your argument.

In this section, we'll break down how to structure and write these paragraphs effectively:

Topic sentence: A topic sentence is an opening sentence of the paragraph. The points that will support the main thesis statement are individually presented in each section.

For example:

“The first boy, Jack, believes that a beast truly does exist…”

Evidence: To support the claim made in the topic sentence, evidence is provided. The evidence is taken from the selected piece of work to make the reasoning strong and logical.

“...He is afraid and admits it; however, he deals with his fear of aggressive violence. He chooses to hunt for the beast, arms himself with a spear, and practice killing it: “We’re strong—we hunt! If there’s a beast, we’ll hunt it down! We’ll close in and beat and beat and beat—!”(91).”

Analysis: A literary essay is a kind of essay that requires a writer to provide his analysis as well.

The purpose of providing the writer’s analysis is to tell the readers about the meaning of the evidence.

“...He also uses the fear of the beast to control and manipulate the other children. Because they fear the beast, they are more likely to listen to Jack and follow his orders...”

Transition words: Transition or connecting words are used to link ideas and points together to maintain a logical flow. Transition words that are often used in a literary analysis essay are:

- Furthermore

- Later in the story

- In contrast, etc.

“...Furthermore, Jack fears Ralph’s power over the group and Piggy’s rational thought. This is because he knows that both directly conflict with his thirst for absolute power...”

Concluding sentence: The last sentence of the body that gives a final statement on the topic sentence is the concluding sentence. It sums up the entire discussion held in that specific paragraph.

Here is a literary analysis paragraph example for you:

Literary Essay Example Pdf

Literary Analysis Essay Conclusion

The last section of the essay is the conclusion part where the writer ties all loose ends of the essay together. To write appropriate and correct concluding paragraphs, add the following information:

- State how your topic is related to the theme of the chosen work

- State how successfully the author delivered the message

- According to your perspective, provide a statement on the topic

- If required, present predictions

- Connect your conclusion to your introduction by restating the thesis statement.

- In the end, provide an opinion about the significance of the work.

For example,

“ In conclusion, William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies exposes the reader to three characters with different personalities and fears: Jack, Ralph, and Piggy. Each of the boys tries to conquer his fear in a different way. Fear is a natural emotion encountered by everyone, but each person deals with it in a way that best fits his/her individual personality.”

Literary Analysis Essay Outline (PDF)

Literary Analysis Essay Format

A literary analysis essay delves into the examination and interpretation of a literary work, exploring themes, characters, and literary devices.

Below is a guide outlining the format for a structured and effective literary analysis essay.

Formatting Guidelines

- Use a legible font (e.g., Times New Roman or Arial) and set the font size to 12 points.

- Double-space your essay, including the title, headings, and quotations.

- Set one-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Indent paragraphs by 1/2 inch or use the tab key.

- Page numbers, if required, should be in the header or footer and follow the specified formatting style.

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Example

To fully understand a concept in a writing world, literary analysis outline examples are important. This is to learn how a perfectly structured writing piece is drafted and how ideas are shaped to convey a message.

The following are the best literary analysis essay examples to help you draft a perfect essay.

Literary Analysis Essay Rubric (PDF)

High School Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline College (PDF)

Literary Analysis Essay Example Romeo & Juliet (PDF)

AP Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Middle School

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Are you seeking inspiration for your next literary analysis essay? Here is a list of literary analysis essay topics for you:

- The Theme of Alienation in "The Catcher in the Rye"

- The Motif of Darkness in Shakespeare's Tragedies

- The Psychological Complexity of Hamlet's Character

- Analyzing the Narrator's Unreliable Perspective in "The Tell-Tale Heart"

- The Role of Nature in William Wordsworth's Romantic Poetry

- The Representation of Social Class in "To Kill a Mockingbird"

- The Use of Irony in Mark Twain's "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn"

- The Impact of Holden's Red Hunting Hat in the Novel

- The Power of Setting in Gabriel García Márquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude"

- The Symbolism of the Conch Shell in William Golding's "Lord of the Flies"

Need more topics? Read our literary analysis essay topics blog!

All in all, writing a literary analysis essay can be tricky if it is your first attempt. Apart from analyzing the work, other elements like a topic and an accurate interpretation must draft this type of essay.

If you are in doubt to draft a perfect essay, get professional essay writing assistance from expert writers at MyPerfectWords.com.

We are a professional essay writing company that provides guidance and helps students to achieve their academic goals. Our qualified writers assist students by providing assistance at an affordable price.

So, why wait? Let us help you in achieving your academic goals!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Cathy has been been working as an author on our platform for over five years now. She has a Masters degree in mass communication and is well-versed in the art of writing. Cathy is a professional who takes her work seriously and is widely appreciated by clients for her excellent writing skills.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Reading Skills

Using textual evidence to support claims.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: November 1, 2023

What We Review

Introduction

When you’re making your point in an essay or a class debate, it’s super important to back it up with evidence from the text you’re discussing. Think of it like showing your work in math class; without that step, you’re just sharing an opinion that might not seem well-founded.

It’s not the most exciting thing to search for text evidence to incorporate into your writing. It takes work! Digging to find the right evidence, integrating it, citing it correctly, and explaining how it ultimately supports your claim is no simple task.

However, this process is an immensely powerful exercise in teaching students how to become effective communicators. High school is all about learning to juggle different kinds of reading – stories, factual articles, you name it – and making strong points about them. And this isn’t just for getting good grades. This skill will follow you to college and even to your future job, where being able to back up your ideas with solid facts will really matter.

What is Textual Evidence?

Alright, let’s break it down: What’s this thing called textual evidence? It’s pretty much any part of a book or article that you use to back up your points. It could be an exact line taken straight from the text (a direct quote), your own version of what the author said (a paraphrase), or even a boiled-down version of a big section (a summary). No matter how you slice it, the goal is the same: to support your argument.

In high school, you’ll often be asked to dig deep into books and write a literary analysis. This is just a fancy way of looking closely at a particular piece of the book, like the theme or how the characters change over time. Take, for example, if you’re asked to write about how Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird deals with racial discrimination.

You’d go on a sort of scavenger hunt through the novel, hunting for every bit that shows racial discrimination. Then, in your essay, you’ll bring out these examples to back up your point. Like, you might sum up the trial of Tom Robinson to show that even though there wasn’t enough evidence to prove he did anything wrong, he was still convicted. That’s a powerful piece of textual evidence to help explain the book’s message about the unfairness of racial prejudice.

Identifying Textual Evidence

Now let’s figure out how to spot the right textual evidence. When you need to back up your points, picking the right evidence from the text can be tricky. If you closely read the text, you’ll be in a way better position to choose the strongest evidence for your argument.

So, you’ve read closely and marked up the text with notes and highlights. When it’s time to write your essay, these annotations are like a treasure map. You don’t have to reread everything; just skim through your notes to see which bits connect to your point. Find a section that fits with what you’re saying? Great—now decide how to use it best in your essay. Sometimes you’ll use the exact words (a direct quote), and other times you’ll put it in your own words (paraphrase).

Let’s say you’re looking at “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and you note where the Black community sits during Tom Robinson’s trial—in a separate balcony. This detail doesn’t come from someone’s mouth, but it’s a powerful snapshot of racial segregation, so you don’t need to quote anyone. On the flip side, when Atticus Finch nails it with his speech about the false belief that all Black people are not to be trusted, his exact words are gold. They directly show the theme of racial discrimination, so you’d definitely quote him directly in your essay.

Evaluating Textual Evidence

When you’re writing an essay for English class, you know the books and stories you study are solid sources. But what about when you’re on your own, searching online for that perfect piece of evidence to make your essay shine? It’s not always easy to know if what you find on the internet is reliable. Here’s a quick guide to judge if an online source is up to the mark:

- Who Wrote It: Check out who’s behind the article or webpage. What’s their background or education? Are they an expert? This matters because you want info from people who are trusted in their field.

- Fact-Check: Look at the info you find and cross-check it with other sources. If a website claims “To Kill a Mockingbird” is about how to catch birds, that’s a red flag—it’s way off from the book’s actual content.

- Look for Citations: Good authors back up their points with evidence, just like you’re doing in your essays. If the webpage or article lists its sources, that’s a sign the author has done their homework.

- Watch for Bias: It’s okay for sources to have a point of view , but you should know what that bias is. Understanding an author’s perspective helps you consider how their opinion might shape the information they present.

- Freshness: How recent is the information? Check when the article was written or last updated. While the latest isn’t always the greatest, especially for classic literature, it’s still good to know if the information is current.

Remember, picking the right evidence isn’t just about filling in quotes—it’s about building a case that what you’re saying is legit. And that means being choosy about where you get your facts from, especially online.

Incorporating Textual Evidence into Analysis

Got your claim and your evidence lined up? Great, now let’s talk about how to weave that into your essay without it sounding like a jumbled mess. Kick things off with a clear thesis statement. This is where you lay out your main argument and hint at how you will prove it.

Now, when chatting with friends, you probably introduce cool facts or stories with a casual “Hey, did you know…” or “For instance…” Use that same approach in your essay. Phrases like “For example” or “As [this character] states in the text…” are your friends here. They help you slide your evidence into your essay smoothly.

Don’t forget about those punctuation marks when you’re using direct quotes; they’re like traffic signals for your reader, so they don’t get lost. And whether you’re quoting directly, paraphrasing, or summarizing, always pop an in-text citation in there to give credit where it’s due. It’s like saying, “Hey, don’t just take my word for it; here’s where I got it from.”

Finally, don’t just drop a quote and run. Follow it up with a clear explanation. This is where you tie your evidence back to your claim, showing how it backs up your argument. Think of it as the grand finale of your evidence presentation—it makes your case convincing.

Textual Evidence in Action: Dissecting Discrimination in To Kill a Mockingbird

Below is an example from an essay on racial discrimination in To Kill a Mockingbird that uses these conventions.

“In Harper Lee’s novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, the theme of racial discrimination is revealed through the events of Tom Robinson’s trial, from the threats he received at the jail, to Atticus’ charge to the jury, and finally, in the trial’s unjust verdict. For example, in Chapter 15, Tom Robinson is being held at the local jail, and Atticus Finch takes it upon himself to guard Tom’s cell. Finch’s decision is not unwarranted, as several cars pulled up to the jail, men got out of their cars, and these men surrounded Atticus (Lee 127). Finch knew that these men racially discriminated against Tom and intended violence against him as a Black man, and Finch was determined to protect Tom and ensure that Tom was granted a chance at a fair trial.”

Common Pitfalls and Mistakes

When it comes to writing a killer literary analysis, there are a few traps students tend to fall into. For starters, getting citations wrong or skipping them altogether is a big no-no. Luckily, resources like the Purdue OWL website are there to help you nail the citation game.

Another slip-up is making your evidence say too much or too little. Imagine saying, “Some mad guys chatted with Atticus at the jail and bounced.” That’s way too vague and doesn’t do the job of explaining how it supports your point. Plus, it kind of twists what actually happened in “To Kill a Mockingbird”.

Picking evidence that doesn’t fit your claim is another common blunder. Say you’re talking about racism, and you bring up how the people of Maycomb don’t trust the Ewells. If you’re using that to show racial discrimination, you’re off track because their mistrust is about the Ewells’ nasty reputation, not their race.

What is the best way to sidestep these errors? Make sure you really get the text. That means reading closely and carefully so that when it’s time to write, you choose the best bits of the book that really back up your argument.

Wrapping it up, when you’re making a point about what you’ve read, it’s crucial to back it up with solid text evidence. You’ve got to be on the ball with picking out the right parts of the text, judging which online sources are legit, and mixing your evidence into your argument just right. Learning to stand up for your ideas with clear writing and confident talking is a game-changer. It’s all about getting your point across with evidence that packs a punch. That’s how you go from just saying something to really proving it—and that’s a skill that’ll take you places – in school and beyond.

Practice Makes Perfect

To truly hone your skills in analyzing and supporting arguments with textual evidence, regular practice is key—and that’s where Albert comes into play. It’s not just about reading; it’s about engaging with a range of texts to sharpen your analytical tools.

If you’re just starting out, our Short Readings course is ideal. It uses brief passages to solidify those vital reading skills.

Another option for practice is our Leveled Readings course, where you’ll find a range of Lexile® leveled passages that all revolve around essential questions. This ensures that everyone is engaged, no matter their reading level. Click here for more information about the Lexile® framework!

Albert.io isn’t just about the practice—it’s about practicing smart. With a user-friendly interface and feedback that actually teaches you something, it’s your go-to for mastering close reading and getting to grips with complex texts. When it comes to backing up your points with the right evidence, you’ll be doing it with confidence and flair.

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.2: The Writing Process for Literary Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 118961

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Why Follow the Writing Process?

Even the most talented writers rarely get a piece right in their first draft. What's more, few writers create a first draft through a single, sustained effort. Instead, the best writers understand that writing is a process: it takes time; sustained attention; and a willingness to change, expand, and even delete words as one writes. Good writing also takes a willingness to seek feedback from peers and mentors and to accept and use the advice they give. In this book, we will refer to and model the writing process , showing how student writers like yourself worked toward compelling papers about literary works. Watch the video below where author Salman Rushdie talks about some misconceptions new writers sometimes have about what it takes to write effectively. Though he is discussing novels specifically, the same concepts apply to literary essays.

The following are a few famous writers' pieces of advice when it comes to following the writing process:

- "For me and most of the other writers I know, writing is not rapturous. In fact, the only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts"—Anne Lamott

- "The key to writing is concentration, not inspiration"—Salman Rushdie

- "By the time I am nearing the end of a story, the first part will have been reread and altered and corrected at least one hundred and fifty times. I am suspicious of both facility and speed. Good writing is essentially rewriting. I am positive of this." —Roald Dahl (Vander Hook)

- "I don't write easily or rapidly. My first draft usually has only a few elements worth keeping. I have to find what those are and build from them and throw out what doesn't work, or what simply is not alive." —Susan Sontag (Lee)

Take it from the writing experts: following the writing process is the key to writing success. Following this process can be liberatory in the sense that you don't have to feel an immense pressure to write brilliantly. The best writing takes time, incremental effort, and resilience.

As I often tell my students:

"There is no such thing as bad writers, only writers who give up too soon. There is no such thing as bad writing, just writing in need of revision." This means anyone can write a strong essay if they follow the writing process!

Your process

- How do you typically approach writing assignments in your classes? When do you start working? Do you employ any prewriting techniques?

- Have you ever been given the chance to revise your writing after receiving feedback from your peers or your instructor? How did the act of revising change your relationship to your paper?

Good writing takes, above all, planning and organization. If you wait until the night before a written assignment is due to begin, your hurrying will supersede the necessary steps of prewriting, researching, outlining, drafting, revising, seeking feedback, and re-revising. Those stages look something like this:

The Writing Process Steps

First, read the work of literature you plan to write about. This may seem like an obvious step, but some students think they can write an effective essay by just reading the SparkNotes or Shmoop. While some students may be able to get away with writing a passing essay this way, most cannot. Besides, by completing the readings, you actually learn!

Many of the questions and activities peppered throughout sections of this book will be prewriting activities. We'll ask you to reflect on your reading, to make connections between your experiences and our text, and to jot down ideas spurred by your engagement with the theories presented here. It's from activities like these that writers often get their ideas for writing. The more engaged you are as a reader, the more engaged you'll be when the time comes to write.

Researching

This book will also help you start the research process, in which you hone in on those aspects of a given literary text that interest you and seek out a deeper understanding of those aspects. Literary researchers read not only literary texts but also the work of other literary scholars and even sources that are indirectly related to literature, such as primary historical documents and biographies. In other words, they seek a wide range of texts that can supplement their understanding of the story, poem, play, or other text they want to write about. As you research, you should keep prewriting, keeping a record of what you agree with, what you disagree with, and what you feel needs further exploration in the texts you read.

To write well, you should have a plan. As you write, that plan may change while you learn more about your topic and begin to fully understand your own ideas. However, papers are easier to tackle when you first sketch out the broad outline of your ideas, a general arc or path you want your paper to follow. Committing those ideas to paper will help you see how different ideas relate to one another (or don't relate to one another). Don't be afraid to revise your outline — play around with the sequence of your ideas and evidence until you find the most logical progression.

The most important way to improve your writing is to start writing! Because you’re treating writing as a process, it's not important that every word you type be perfectly chosen, or that every sentence be exquisitely crafted. When you're drafting, the most important thing is that you get words on paper. Follow your outline and write. If ideas come to you as you're writing, but do not quite fit in that section of the paper, make note of it! You don't have to use it, but few things are more frustrating than forgetting an idea that might work perfectly for your paper.

After you've committed words to paper (or, more accurately, to your computer screen), you can go back and shape them more deliberately through revision . Cognitive research has shown that a significant portion of reading is actually remembering. As a result, if you read your work immediately after writing it, you probably won't notice any of the potential problems with it. Your brain will "fill in the gaps" of poor grammar, misspelling, or faulty reasoning. Because of this, you should give yourself some time in between drafting and revising—the more time the better. As you revise, try to approach your text as your readers will. Ask yourself skeptical questions (e.g., Are there clear connections between the different claims I'm making in this paper? Do I provide enough evidence to convince someone to believe my claims?). Revisions can often be substantial: you may need to rearrange your points, delete significant portions of what you've written, or rewrite sentences and paragraphs to better reflect the ideas you have developed while writing. Don't be afraid to cut the parts of your paper that aren't working, even if you like a particular fact or anecdote. Don't be afraid to, as they say, "Kill your darlings." Everything in your paper should, on some level, work towards the purpose of your claim. Most importantly, you should revise your introduction several times. Writers often work into their strongest ideas, which then appear in their conclusions but not (if they do not revise) their introductions. Make sure that your introduction reflects the more nuanced claims that appear in the body and conclusion of your paper.

Seeking Feedback

Even after years of practice revising your writing, you'll never be able to see it in an entirely objective light. To really improve your writing, you need feedback from others who can identify where your ideas are not as clear as they should be. You can seek feedback in a number of ways: you can make an appointment in your college's writing center, you can participate in class peer-review workshops, or you can talk to your instructor during his or her office hours. If you will have a chance to revise your paper after your instructor grades it, his or her comments on that graded draft should be considered essential feedback as you revise.

Re-revising

Once you've garnered feedback on your writing, you should use that feedback to revise your paper yet again. You should not, however, simply make every change that your colleagues or instructor recommended. You should think about the suggestions they've made and ensure that their suggestions will help you make the argument you want to make. You may decide to incorporate some suggestions and not others. Not all feedback is helpful or applicable. It takes some critical thinking to determine whether the feedback will improve the essay. When you treat writing as a process, it should become a genuine dialogue between you and your readers.

Finally, you will submit your paper to an audience for review. As college students, this primarily means the paper you turn in to your instructor for evaluation.

Writing Process Not Linear, But a Cycle

The preceding categories suggest that writing is a linear process — that is, that you will follow these steps in the following order:

prewriting→researching→outlining→drafting→revising→feedback→re-revising→publishing.

The reality of the writing process, however, is that as you write you shuttle back and forth in these stages. For example, as you begin writing your thesis paragraph, the beginning of your essay, you will write and revise many times before you are satisfied with your opening; once you have a complete draft, you will more than likely return to the introduction to revise it again to better match the contents of the completed essay. This shuttling highlights the recursive nature of the writing process and can be diagrammed as follows:

prewriting↔researching↔outlining↔drafting↔revising↔feedback↔re-revising↔publishing.

This is a good thing. If you are too rigid in your process, it's easier to get stuck on insisting an idea or claim that might not be working, rather than discovering one or coming to an informed, well-reasoned conclusion. Furthermore, you should be aware that each writer has a unique writing process: some will be diligent outliners, while others may discover ideas as they write. There is no right way to write (so to speak), but the key is the notion of process — all strong writers engage in the writing process and recognize the importance of feedback and revision in the process.

- Describe your current writing process.

- Do you normally engage in the stages listed previously?

- If not, why? If so, what part of the process do you find most helpful?

Share your process with the class to discover the variety of approaches writers take. Always be willing to try new methods of approaching the writing process. You might find a new tool or habit that works well for you!

Works Cited

Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . Random House, 1994.

Lee, Martin. Telling Stories: The Craft of Narrative and Writing Life . University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

Rushdie, Salman. "Inspiration is Nonsense." The Big Think, 2011. https://bigthink.com/videos/inspiration-is-nonsense

Vander Hook, Sue. Writing Notable Narrative Nonfiction . Lerner Publishing Group, 2016.

Contributors and Attributions

- Adapted from "What is the Writing Process?" from Creating Literary Analysis by Ryan Cordell and John Pennington, CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

Thesis Statements for a Literature Assignment

A thesis prepares the reader for what you are about to say. As such, your paper needs to be interesting in order for your thesis to be interesting. Your thesis needs to be interesting because it needs to capture a reader's attention. If a reader looks at your thesis and says "so what?", your thesis has failed to do its job, and chances are your paper has as well. Thus, make your thesis provocative and open to reasonable disagreement, but then write persuasively enough to sway those who might be disagree.

Keep in mind the following when formulating a thesis:

- A Thesis Should Not State the Obvious

- Use Literary Terms in Thesis With Care

- A Thesis Should be Balanced

- A Thesis Can be a Blueprint

Avoid the Obvious

Bland: Dorothy Parker's "Résumé" uses images of suicide to make her point about living.

This is bland because it's obvious and incontestable. A reader looks at it and says, "so what?"

However, consider this alternative:

Dorothy Parker's "Résumé" doesn't celebrate life, but rather scorns those who would fake or attempt suicide just to get attention.

The first thesis merely describes something about the poem; the second tells the reader what the writer thinks the poem is about--it offers a reading or interpretation. The paper would need to support that reading and would very likely examine the way Parker uses images of suicide to make the point the writer claims.

Use Literary Terms in Thesis Only to Make Larger Points

Poems and novels generally use rhyme, meter, imagery, simile, metaphor, stanzas, characters, themes, settings and so on. While these terms are important for you to use in your analysis and your arguments, that they exist in the work you are writing about should not be the main point of your thesis. Unless the poet or novelist uses these elements in some unexpected way to shape the work's meaning, it's generally a good idea not to draw attention to the use of literary devices in thesis statements because an intelligent reader expects a poem or novel to use literary of these elements. Therefore, a thesis that only says a work uses literary devices isn't a good thesis because all it is doing is stating the obvious, leading the reader to say, "so what?"

However, you can use literary terms in a thesis if the purpose is to explain how the terms contribute to the work's meaning or understanding. Here's an example of thesis statement that does call attention to literary devices because they are central to the paper's argument. Literary terms are placed in italics.

Don Marquis introduced Archy and Mehitabel in his Sun Dial column by combining the conventions of free verse poetry with newspaper prose so intimately that in "the coming of Archy," the entire column represents a complete poem and not a free verse poem preceded by a prose introduction .

Note the difference between this thesis and the first bland thesis on the Parker poem. This thesis does more than say certain literary devices exist in the poem; it argues that they exist in a specific relationship to one another and makes a fairly startling claim, one that many would disagree with and one that the writer will need to persuade her readers on.

Keep Your Thesis Balanced

Keep the thesis balanced. If it's too general, it becomes vague; if it's too specific, it cannot be developed. If it's merely descriptive (like the bland example above), it gives the reader no compelling reason to go on. The thesis should be dramatic, have some tension in it, and should need to be proved (another reason for avoiding the obvious).

Too general: Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote many poems with love as the theme. Too specific: Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" in <insert date> after <insert event from her life>. Too descriptive: Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" is a sonnet with two parts; the first six lines propose a view of love and the next eight complicate that view. With tension and which will need proving: Despite her avowal on the importance of love, and despite her belief that she would not sell her love, the speaker in Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" remains unconvinced and bitter, as if she is trying to trick herself into believing that love really does matter for more than the one night she is in some lover's arms.

Your Thesis Can Be A Blueprint

A thesis can be used as roadmap or blueprint for your paper:

In "Résumé," Dorothy Parker subverts the idea of what a résumé is--accomplishments and experiences--with an ironic tone, silly images of suicide, and witty rhymes to point out the banality of life for those who remain too disengaged from it.

Note that while this thesis refers to particular poetic devices, it does so in a way that gets beyond merely saying there are poetic devices in the poem and then merely describing them. It makes a claim as to how and why the poet uses tone, imagery and rhyme.

Readers would expect you to argue that Parker subverts the idea of the résumé to critique bored (and boring) people; they would expect your argument to do so by analyzing her use of tone, imagery and rhyme in that order.

Carbone, Nick. (1997). Thesis Statements for a Literature Assignment. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=51

English Composition 1

Developing effective arguments with claims, evidence, and warrants.

There are three major elements to persuasive writing and argumentation: claims, evidence, and warrants. Each is explained below.

- Thoreau believed that preoccupation with insignificant events caused nineteenth-century Americans to overlook what is important in life.

- Thoreau felt that technology was the primary cause of distress for nineteenth-century Americans.

- Thoreau thought that we should follow the ways of nature to lead more fulfilling lives.

- Thoreau felt that each individual has the responsibility to understand and reject the "shams and delusions" that are too often accepted as truths.

- Thoreau demonstrated his misanthropy (hatred of human beings) in his essay and saw no choice but to abandon civilization.

Notice how we could argue over the truth of the statements presented above. This fact alone should help you determine if you are presenting a claim. A claim, by its very nature, includes the possibility of at least two different, sometimes opposing, points of view. After all, there would be no reason to argue for a belief or interpretation if the subject of the belief or interpretation provided for only one possible point of view.