Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

Published on July 12, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on November 20, 2023.

Research objectives describe what your research is trying to achieve and explain why you are pursuing it. They summarize the approach and purpose of your project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement . They should:

- Establish the scope and depth of your project

- Contribute to your research design

- Indicate how your project will contribute to existing knowledge

Table of contents

What is a research objective, why are research objectives important, how to write research aims and objectives, smart research objectives, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research objectives.

Research objectives describe what your research project intends to accomplish. They should guide every step of the research process , including how you collect data , build your argument , and develop your conclusions .

Your research objectives may evolve slightly as your research progresses, but they should always line up with the research carried out and the actual content of your paper.

Research aims

A distinction is often made between research objectives and research aims.

A research aim typically refers to a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear at the end of your problem statement, before your research objectives.

Your research objectives are more specific than your research aim and indicate the particular focus and approach of your project. Though you will only have one research aim, you will likely have several research objectives.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Research objectives are important because they:

- Establish the scope and depth of your project: This helps you avoid unnecessary research. It also means that your research methods and conclusions can easily be evaluated .

- Contribute to your research design: When you know what your objectives are, you have a clearer idea of what methods are most appropriate for your research.

- Indicate how your project will contribute to extant research: They allow you to display your knowledge of up-to-date research, employ or build on current research methods, and attempt to contribute to recent debates.

Once you’ve established a research problem you want to address, you need to decide how you will address it. This is where your research aim and objectives come in.

Step 1: Decide on a general aim

Your research aim should reflect your research problem and should be relatively broad.

Step 2: Decide on specific objectives

Break down your aim into a limited number of steps that will help you resolve your research problem. What specific aspects of the problem do you want to examine or understand?

Step 3: Formulate your aims and objectives

Once you’ve established your research aim and objectives, you need to explain them clearly and concisely to the reader.

You’ll lay out your aims and objectives at the end of your problem statement, which appears in your introduction. Frame them as clear declarative statements, and use appropriate verbs to accurately characterize the work that you will carry out.

The acronym “SMART” is commonly used in relation to research objectives. It states that your objectives should be:

- Specific: Make sure your objectives aren’t overly vague. Your research needs to be clearly defined in order to get useful results.

- Measurable: Know how you’ll measure whether your objectives have been achieved.

- Achievable: Your objectives may be challenging, but they should be feasible. Make sure that relevant groundwork has been done on your topic or that relevant primary or secondary sources exist. Also ensure that you have access to relevant research facilities (labs, library resources , research databases , etc.).

- Relevant: Make sure that they directly address the research problem you want to work on and that they contribute to the current state of research in your field.

- Time-based: Set clear deadlines for objectives to ensure that the project stays on track.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

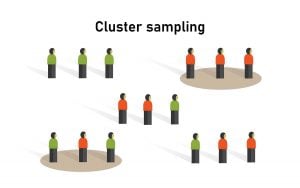

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Research objectives describe what you intend your research project to accomplish.

They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement .

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

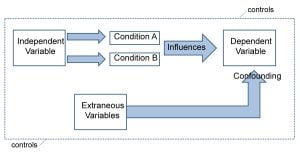

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, November 20). Research Objectives | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-objectives/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- How it works

Published by Nicolas at March 21st, 2024 , Revised On March 12, 2024

The Ultimate Guide To Research Methodology

Research methodology is a crucial aspect of any investigative process, serving as the blueprint for the entire research journey. If you are stuck in the methodology section of your research paper , then this blog will guide you on what is a research methodology, its types and how to successfully conduct one.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Methodology?

Research methodology can be defined as the systematic framework that guides researchers in designing, conducting, and analyzing their investigations. It encompasses a structured set of processes, techniques, and tools employed to gather and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of the research findings.

Research methodology is not confined to a singular approach; rather, it encapsulates a diverse range of methods tailored to the specific requirements of the research objectives.

Here is why Research methodology is important in academic and professional settings.

Facilitating Rigorous Inquiry

Research methodology forms the backbone of rigorous inquiry. It provides a structured approach that aids researchers in formulating precise thesis statements , selecting appropriate methodologies, and executing systematic investigations. This, in turn, enhances the quality and credibility of the research outcomes.

Ensuring Reproducibility And Reliability

In both academic and professional contexts, the ability to reproduce research outcomes is paramount. A well-defined research methodology establishes clear procedures, making it possible for others to replicate the study. This not only validates the findings but also contributes to the cumulative nature of knowledge.

Guiding Decision-Making Processes

In professional settings, decisions often hinge on reliable data and insights. Research methodology equips professionals with the tools to gather pertinent information, analyze it rigorously, and derive meaningful conclusions.

This informed decision-making is instrumental in achieving organizational goals and staying ahead in competitive environments.

Contributing To Academic Excellence

For academic researchers, adherence to robust research methodology is a hallmark of excellence. Institutions value research that adheres to high standards of methodology, fostering a culture of academic rigour and intellectual integrity. Furthermore, it prepares students with critical skills applicable beyond academia.

Enhancing Problem-Solving Abilities

Research methodology instills a problem-solving mindset by encouraging researchers to approach challenges systematically. It equips individuals with the skills to dissect complex issues, formulate hypotheses , and devise effective strategies for investigation.

Understanding Research Methodology

In the pursuit of knowledge and discovery, understanding the fundamentals of research methodology is paramount.

Basics Of Research

Research, in its essence, is a systematic and organized process of inquiry aimed at expanding our understanding of a particular subject or phenomenon. It involves the exploration of existing knowledge, the formulation of hypotheses, and the collection and analysis of data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Research is a dynamic and iterative process that contributes to the continuous evolution of knowledge in various disciplines.

Types of Research

Research takes on various forms, each tailored to the nature of the inquiry. Broadly classified, research can be categorized into two main types:

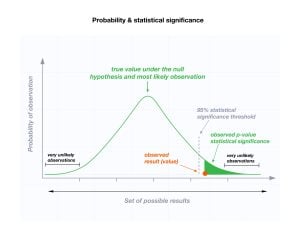

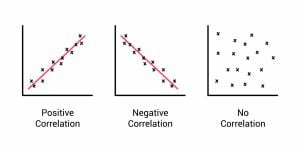

- Quantitative Research: This type involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to identify patterns, relationships, and statistical significance. It is particularly useful for testing hypotheses and making predictions.

- Qualitative Research: Qualitative research focuses on understanding the depth and details of a phenomenon through non-numerical data. It often involves methods such as interviews, focus groups, and content analysis, providing rich insights into complex issues.

Components Of Research Methodology

To conduct effective research, one must go through the different components of research methodology. These components form the scaffolding that supports the entire research process, ensuring its coherence and validity.

Research Design

Research design serves as the blueprint for the entire research project. It outlines the overall structure and strategy for conducting the study. The three primary types of research design are:

- Exploratory Research: Aimed at gaining insights and familiarity with the topic, often used in the early stages of research.

- Descriptive Research: Involves portraying an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon, answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Explanatory Research: Seeks to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how.’

Data Collection Methods

Choosing the right data collection methods is crucial for obtaining reliable and relevant information. Common methods include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Employed to gather information from a large number of respondents through standardized questions.

- Interviews: In-depth conversations with participants, offering qualitative insights.

- Observation: Systematic watching and recording of behaviour, events, or processes in their natural setting.

Data Analysis Techniques

Once data is collected, analysis becomes imperative to derive meaningful conclusions. Different methodologies exist for quantitative and qualitative data:

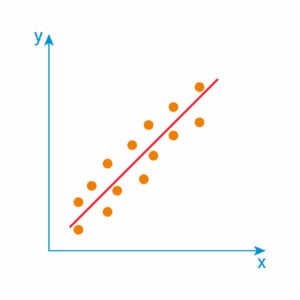

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Involves statistical techniques such as descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and regression analysis to interpret numerical data.

- Qualitative Data Analysis: Methods like content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory are employed to extract patterns, themes, and meanings from non-numerical data.

The research paper we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Choosing a Research Method

Selecting an appropriate research method is a critical decision in the research process. It determines the approach, tools, and techniques that will be used to answer the research questions.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data, providing a structured and objective approach to understanding and explaining phenomena.

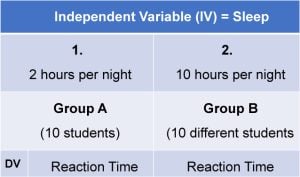

Experimental Research

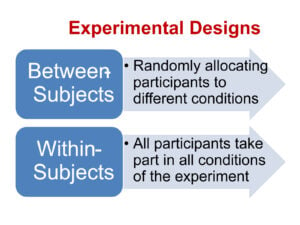

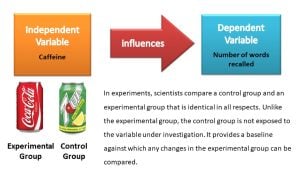

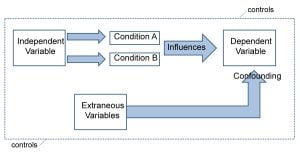

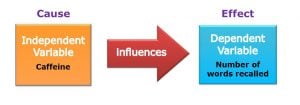

Experimental research involves manipulating variables to observe the effect on another variable under controlled conditions. It aims to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Key Characteristics:

- Controlled Environment: Experiments are conducted in a controlled setting to minimize external influences.

- Random Assignment: Participants are randomly assigned to different experimental conditions.

- Quantitative Data: Data collected is numerical, allowing for statistical analysis.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies and psychology to test hypotheses and identify causal relationships.

Survey Research

Survey research gathers information from a sample of individuals through standardized questionnaires or interviews. It aims to collect data on opinions, attitudes, and behaviours.

- Structured Instruments: Surveys use structured instruments, such as questionnaires, to collect data.

- Large Sample Size: Surveys often target a large and diverse group of participants.

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Responses are quantified for statistical analysis.

Applications: Widely employed in social sciences, marketing, and public opinion research to understand trends and preferences.

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research seeks to portray an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon. It focuses on answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Observation and Data Collection: This involves observing and documenting without manipulating variables.

- Objective Description: Aim to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: T his can include both types of data, depending on the research focus.

Applications: Useful in situations where researchers want to understand and describe a phenomenon without altering it, common in social sciences and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research emphasizes exploring and understanding the depth and complexity of phenomena through non-numerical data.

A case study is an in-depth exploration of a particular person, group, event, or situation. It involves detailed, context-rich analysis.

- Rich Data Collection: Uses various data sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents.

- Contextual Understanding: Aims to understand the context and unique characteristics of the case.

- Holistic Approach: Examines the case in its entirety.

Applications: Common in social sciences, psychology, and business to investigate complex and specific instances.

Ethnography

Ethnography involves immersing the researcher in the culture or community being studied to gain a deep understanding of their behaviours, beliefs, and practices.

- Participant Observation: Researchers actively participate in the community or setting.

- Holistic Perspective: Focuses on the interconnectedness of cultural elements.

- Qualitative Data: In-depth narratives and descriptions are central to ethnographic studies.

Applications: Widely used in anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies to explore and document cultural practices.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory aims to develop theories grounded in the data itself. It involves systematic data collection and analysis to construct theories from the ground up.

- Constant Comparison: Data is continually compared and analyzed during the research process.

- Inductive Reasoning: Theories emerge from the data rather than being imposed on it.

- Iterative Process: The research design evolves as the study progresses.

Applications: Commonly applied in sociology, nursing, and management studies to generate theories from empirical data.

Research design is the structural framework that outlines the systematic process and plan for conducting a study. It serves as the blueprint, guiding researchers on how to collect, analyze, and interpret data.

Exploratory, Descriptive, And Explanatory Designs

Exploratory design.

Exploratory research design is employed when a researcher aims to explore a relatively unknown subject or gain insights into a complex phenomenon.

- Flexibility: Allows for flexibility in data collection and analysis.

- Open-Ended Questions: Uses open-ended questions to gather a broad range of information.

- Preliminary Nature: Often used in the initial stages of research to formulate hypotheses.

Applications: Valuable in the early stages of investigation, especially when the researcher seeks a deeper understanding of a subject before formalizing research questions.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research design focuses on portraying an accurate profile of a situation, group, or phenomenon.

- Structured Data Collection: Involves systematic and structured data collection methods.

- Objective Presentation: Aims to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: Can incorporate both types of data, depending on the research objectives.

Applications: Widely used in social sciences, marketing, and educational research to provide detailed and objective descriptions.

Explanatory Design

Explanatory research design aims to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind observed relationships.

- Causal Relationships: Seeks to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Controlled Variables : Often involves controlling certain variables to isolate causal factors.

- Quantitative Analysis: Primarily relies on quantitative data analysis techniques.

Applications: Commonly employed in scientific studies and social sciences to delve into the underlying reasons behind observed patterns.

Cross-Sectional Vs. Longitudinal Designs

Cross-sectional design.

Cross-sectional designs collect data from participants at a single point in time.

- Snapshot View: Provides a snapshot of a population at a specific moment.

- Efficiency: More efficient in terms of time and resources.

- Limited Temporal Insights: Offers limited insights into changes over time.

Applications: Suitable for studying characteristics or behaviours that are stable or not expected to change rapidly.

Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal designs involve the collection of data from the same participants over an extended period.

- Temporal Sequence: Allows for the examination of changes over time.

- Causality Assessment: Facilitates the assessment of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Resource-Intensive: Requires more time and resources compared to cross-sectional designs.

Applications: Ideal for studying developmental processes, trends, or the impact of interventions over time.

Experimental Vs Non-experimental Designs

Experimental design.

Experimental designs involve manipulating variables under controlled conditions to observe the effect on another variable.

- Causality Inference: Enables the inference of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Quantitative Data: Primarily involves the collection and analysis of numerical data.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies, psychology, and medical research to establish causal relationships.

Non-Experimental Design

Non-experimental designs observe and describe phenomena without manipulating variables.

- Natural Settings: Data is often collected in natural settings without intervention.

- Descriptive or Correlational: Focuses on describing relationships or correlations between variables.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: This can involve either type of data, depending on the research approach.

Applications: Suitable for studying complex phenomena in real-world settings where manipulation may not be ethical or feasible.

Effective data collection is fundamental to the success of any research endeavour.

Designing Effective Surveys

Objective Design:

- Clearly define the research objectives to guide the survey design.

- Craft questions that align with the study’s goals and avoid ambiguity.

Structured Format:

- Use a structured format with standardized questions for consistency.

- Include a mix of closed-ended and open-ended questions for detailed insights.

Pilot Testing:

- Conduct pilot tests to identify and rectify potential issues with survey design.

- Ensure clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of questions.

Sampling Strategy:

- Develop a robust sampling strategy to ensure a representative participant group.

- Consider random sampling or stratified sampling based on the research goals.

Conducting Interviews

Establishing Rapport:

- Build rapport with participants to create a comfortable and open environment.

- Clearly communicate the purpose of the interview and the value of participants’ input.

Open-Ended Questions:

- Frame open-ended questions to encourage detailed responses.

- Allow participants to express their thoughts and perspectives freely.

Active Listening:

- Practice active listening to understand areas and gather rich data.

- Avoid interrupting and maintain a non-judgmental stance during the interview.

Ethical Considerations:

- Obtain informed consent and assure participants of confidentiality.

- Be transparent about the study’s purpose and potential implications.

Observation

1. participant observation.

Immersive Participation:

- Actively immerse yourself in the setting or group being observed.

- Develop a deep understanding of behaviours, interactions, and context.

Field Notes:

- Maintain detailed and reflective field notes during observations.

- Document observed patterns, unexpected events, and participant reactions.

Ethical Awareness:

- Be conscious of ethical considerations, ensuring respect for participants.

- Balance the role of observer and participant to minimize bias.

2. Non-participant Observation

Objective Observation:

- Maintain a more detached and objective stance during non-participant observation.

- Focus on recording behaviours, events, and patterns without direct involvement.

Data Reliability:

- Enhance the reliability of data by reducing observer bias.

- Develop clear observation protocols and guidelines.

Contextual Understanding:

- Strive for a thorough understanding of the observed context.

- Consider combining non-participant observation with other methods for triangulation.

Archival Research

1. using existing data.

Identifying Relevant Archives:

- Locate and access archives relevant to the research topic.

- Collaborate with institutions or repositories holding valuable data.

Data Verification:

- Verify the accuracy and reliability of archived data.

- Cross-reference with other sources to ensure data integrity.

Ethical Use:

- Adhere to ethical guidelines when using existing data.

- Respect copyright and intellectual property rights.

2. Challenges and Considerations

Incomplete or Inaccurate Archives:

- Address the possibility of incomplete or inaccurate archival records.

- Acknowledge limitations and uncertainties in the data.

Temporal Bias:

- Recognize potential temporal biases in archived data.

- Consider the historical context and changes that may impact interpretation.

Access Limitations:

- Address potential limitations in accessing certain archives.

- Seek alternative sources or collaborate with institutions to overcome barriers.

Common Challenges in Research Methodology

Conducting research is a complex and dynamic process, often accompanied by a myriad of challenges. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensure the reliability and validity of research findings.

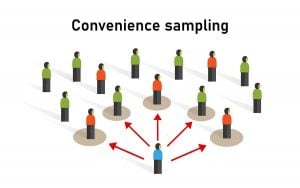

Sampling Issues

Sampling bias:.

- The presence of sampling bias can lead to an unrepresentative sample, affecting the generalizability of findings.

- Employ random sampling methods and ensure the inclusion of diverse participants to reduce bias.

Sample Size Determination:

- Determining an appropriate sample size is a delicate balance. Too small a sample may lack statistical power, while an excessively large sample may strain resources.

- Conduct a power analysis to determine the optimal sample size based on the research objectives and expected effect size.

Data Quality And Validity

Measurement error:.

- Inaccuracies in measurement tools or data collection methods can introduce measurement errors, impacting the validity of results.

- Pilot test instruments, calibrate equipment, and use standardized measures to enhance the reliability of data.

Construct Validity:

- Ensuring that the chosen measures accurately capture the intended constructs is a persistent challenge.

- Use established measurement instruments and employ multiple measures to assess the same construct for triangulation.

Time And Resource Constraints

Timeline pressures:.

- Limited timeframes can compromise the depth and thoroughness of the research process.

- Develop a realistic timeline, prioritize tasks, and communicate expectations with stakeholders to manage time constraints effectively.

Resource Availability:

- Inadequate resources, whether financial or human, can impede the execution of research activities.

- Seek external funding, collaborate with other researchers, and explore alternative methods that require fewer resources.

Managing Bias in Research

Selection bias:.

- Selecting participants in a way that systematically skews the sample can introduce selection bias.

- Employ randomization techniques, use stratified sampling, and transparently report participant recruitment methods.

Confirmation Bias:

- Researchers may unintentionally favour information that confirms their preconceived beliefs or hypotheses.

- Adopt a systematic and open-minded approach, use blinded study designs, and engage in peer review to mitigate confirmation bias.

Tips On How To Write A Research Methodology

Conducting successful research relies not only on the application of sound methodologies but also on strategic planning and effective collaboration. Here are some tips to enhance the success of your research methodology:

Tip 1. Clear Research Objectives

Well-defined research objectives guide the entire research process. Clearly articulate the purpose of your study, outlining specific research questions or hypotheses.

Tip 2. Comprehensive Literature Review

A thorough literature review provides a foundation for understanding existing knowledge and identifying gaps. Invest time in reviewing relevant literature to inform your research design and methodology.

Tip 3. Detailed Research Plan

A detailed plan serves as a roadmap, ensuring all aspects of the research are systematically addressed. Develop a detailed research plan outlining timelines, milestones, and tasks.

Tip 4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical practices are fundamental to maintaining the integrity of research. Address ethical considerations early, obtain necessary approvals, and ensure participant rights are safeguarded.

Tip 5. Stay Updated On Methodologies

Research methodologies evolve, and staying updated is essential for employing the most effective techniques. Engage in continuous learning by attending workshops, conferences, and reading recent publications.

Tip 6. Adaptability In Methods

Unforeseen challenges may arise during research, necessitating adaptability in methods. Be flexible and willing to modify your approach when needed, ensuring the integrity of the study.

Tip 7. Iterative Approach

Research is often an iterative process, and refining methods based on ongoing findings enhance the study’s robustness. Regularly review and refine your research design and methods as the study progresses.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the research methodology.

Research methodology is the systematic process of planning, executing, and evaluating scientific investigation. It encompasses the techniques, tools, and procedures used to collect, analyze, and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of research findings.

What are the methodologies in research?

Research methodologies include qualitative and quantitative approaches. Qualitative methods involve in-depth exploration of non-numerical data, while quantitative methods use statistical analysis to examine numerical data. Mixed methods combine both approaches for a comprehensive understanding of research questions.

How to write research methodology?

To write a research methodology, clearly outline the study’s design, data collection, and analysis procedures. Specify research tools, participants, and sampling methods. Justify choices and discuss limitations. Ensure clarity, coherence, and alignment with research objectives for a robust methodology section.

How to write the methodology section of a research paper?

In the methodology section of a research paper, describe the study’s design, data collection, and analysis methods. Detail procedures, tools, participants, and sampling. Justify choices, address ethical considerations, and explain how the methodology aligns with research objectives, ensuring clarity and rigour.

What is mixed research methodology?

Mixed research methodology combines both qualitative and quantitative research approaches within a single study. This approach aims to enhance the details and depth of research findings by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem or question.

You May Also Like

This blog comprehensively assigns what the cognitive failures questionnaire measures. Read more to get the complete information.

Discover Canadian doctoral dissertation format: structure, formatting, and word limits. Check your university guidelines.

If you are looking for research paper format, then this is your go-to guide, with proper guidelines, from title page to the appendices.

Ready to place an order?

USEFUL LINKS

Learning resources, company details.

- How It Works

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Methodology

Definition:

Research Methodology refers to the systematic and scientific approach used to conduct research, investigate problems, and gather data and information for a specific purpose. It involves the techniques and procedures used to identify, collect , analyze , and interpret data to answer research questions or solve research problems . Moreover, They are philosophical and theoretical frameworks that guide the research process.

Structure of Research Methodology

Research methodology formats can vary depending on the specific requirements of the research project, but the following is a basic example of a structure for a research methodology section:

I. Introduction

- Provide an overview of the research problem and the need for a research methodology section

- Outline the main research questions and objectives

II. Research Design

- Explain the research design chosen and why it is appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Discuss any alternative research designs considered and why they were not chosen

- Describe the research setting and participants (if applicable)

III. Data Collection Methods

- Describe the methods used to collect data (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations)

- Explain how the data collection methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or instruments used for data collection

IV. Data Analysis Methods

- Describe the methods used to analyze the data (e.g., statistical analysis, content analysis )

- Explain how the data analysis methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or software used for data analysis

V. Ethical Considerations

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise from the research and how they were addressed

- Explain how informed consent was obtained (if applicable)

- Detail any measures taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity

VI. Limitations

- Identify any potential limitations of the research methodology and how they may impact the results and conclusions

VII. Conclusion

- Summarize the key aspects of the research methodology section

- Explain how the research methodology addresses the research question(s) and objectives

Research Methodology Types

Types of Research Methodology are as follows:

Quantitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of numerical data using statistical methods. This type of research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Qualitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data such as words, images, and observations. This type of research is often used to explore complex phenomena, to gain an in-depth understanding of a particular topic, and to generate hypotheses.

Mixed-Methods Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that combines elements of both quantitative and qualitative research. This approach can be particularly useful for studies that aim to explore complex phenomena and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic.

Case Study Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves in-depth examination of a single case or a small number of cases. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and anthropology to gain a detailed understanding of a particular individual or group.

Action Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves a collaborative process between researchers and practitioners to identify and solve real-world problems. Action research is often used in education, healthcare, and social work.

Experimental Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the manipulation of one or more independent variables to observe their effects on a dependent variable. Experimental research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Survey Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection of data from a sample of individuals using questionnaires or interviews. Survey research is often used to study attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

Grounded Theory Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the development of theories based on the data collected during the research process. Grounded theory is often used in sociology and anthropology to generate theories about social phenomena.

Research Methodology Example

An Example of Research Methodology could be the following:

Research Methodology for Investigating the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Reducing Symptoms of Depression in Adults

Introduction:

The aim of this research is to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing symptoms of depression in adults. To achieve this objective, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) will be conducted using a mixed-methods approach.

Research Design:

The study will follow a pre-test and post-test design with two groups: an experimental group receiving CBT and a control group receiving no intervention. The study will also include a qualitative component, in which semi-structured interviews will be conducted with a subset of participants to explore their experiences of receiving CBT.

Participants:

Participants will be recruited from community mental health clinics in the local area. The sample will consist of 100 adults aged 18-65 years old who meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Participants will be randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group.

Intervention :

The experimental group will receive 12 weekly sessions of CBT, each lasting 60 minutes. The intervention will be delivered by licensed mental health professionals who have been trained in CBT. The control group will receive no intervention during the study period.

Data Collection:

Quantitative data will be collected through the use of standardized measures such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Data will be collected at baseline, immediately after the intervention, and at a 3-month follow-up. Qualitative data will be collected through semi-structured interviews with a subset of participants from the experimental group. The interviews will be conducted at the end of the intervention period, and will explore participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Data Analysis:

Quantitative data will be analyzed using descriptive statistics, t-tests, and mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVA) to assess the effectiveness of the intervention. Qualitative data will be analyzed using thematic analysis to identify common themes and patterns in participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Ethical Considerations:

This study will comply with ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. Participants will provide informed consent before participating in the study, and their privacy and confidentiality will be protected throughout the study. Any adverse events or reactions will be reported and managed appropriately.

Data Management:

All data collected will be kept confidential and stored securely using password-protected databases. Identifying information will be removed from qualitative data transcripts to ensure participants’ anonymity.

Limitations:

One potential limitation of this study is that it only focuses on one type of psychotherapy, CBT, and may not generalize to other types of therapy or interventions. Another limitation is that the study will only include participants from community mental health clinics, which may not be representative of the general population.

Conclusion:

This research aims to investigate the effectiveness of CBT in reducing symptoms of depression in adults. By using a randomized controlled trial and a mixed-methods approach, the study will provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between CBT and depression. The results of this study will have important implications for the development of effective treatments for depression in clinical settings.

How to Write Research Methodology

Writing a research methodology involves explaining the methods and techniques you used to conduct research, collect data, and analyze results. It’s an essential section of any research paper or thesis, as it helps readers understand the validity and reliability of your findings. Here are the steps to write a research methodology:

- Start by explaining your research question: Begin the methodology section by restating your research question and explaining why it’s important. This helps readers understand the purpose of your research and the rationale behind your methods.

- Describe your research design: Explain the overall approach you used to conduct research. This could be a qualitative or quantitative research design, experimental or non-experimental, case study or survey, etc. Discuss the advantages and limitations of the chosen design.

- Discuss your sample: Describe the participants or subjects you included in your study. Include details such as their demographics, sampling method, sample size, and any exclusion criteria used.

- Describe your data collection methods : Explain how you collected data from your participants. This could include surveys, interviews, observations, questionnaires, or experiments. Include details on how you obtained informed consent, how you administered the tools, and how you minimized the risk of bias.

- Explain your data analysis techniques: Describe the methods you used to analyze the data you collected. This could include statistical analysis, content analysis, thematic analysis, or discourse analysis. Explain how you dealt with missing data, outliers, and any other issues that arose during the analysis.

- Discuss the validity and reliability of your research : Explain how you ensured the validity and reliability of your study. This could include measures such as triangulation, member checking, peer review, or inter-coder reliability.

- Acknowledge any limitations of your research: Discuss any limitations of your study, including any potential threats to validity or generalizability. This helps readers understand the scope of your findings and how they might apply to other contexts.

- Provide a summary: End the methodology section by summarizing the methods and techniques you used to conduct your research. This provides a clear overview of your research methodology and helps readers understand the process you followed to arrive at your findings.

When to Write Research Methodology

Research methodology is typically written after the research proposal has been approved and before the actual research is conducted. It should be written prior to data collection and analysis, as it provides a clear roadmap for the research project.

The research methodology is an important section of any research paper or thesis, as it describes the methods and procedures that will be used to conduct the research. It should include details about the research design, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and any ethical considerations.

The methodology should be written in a clear and concise manner, and it should be based on established research practices and standards. It is important to provide enough detail so that the reader can understand how the research was conducted and evaluate the validity of the results.

Applications of Research Methodology

Here are some of the applications of research methodology:

- To identify the research problem: Research methodology is used to identify the research problem, which is the first step in conducting any research.

- To design the research: Research methodology helps in designing the research by selecting the appropriate research method, research design, and sampling technique.

- To collect data: Research methodology provides a systematic approach to collect data from primary and secondary sources.

- To analyze data: Research methodology helps in analyzing the collected data using various statistical and non-statistical techniques.

- To test hypotheses: Research methodology provides a framework for testing hypotheses and drawing conclusions based on the analysis of data.

- To generalize findings: Research methodology helps in generalizing the findings of the research to the target population.

- To develop theories : Research methodology is used to develop new theories and modify existing theories based on the findings of the research.

- To evaluate programs and policies : Research methodology is used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and policies by collecting data and analyzing it.

- To improve decision-making: Research methodology helps in making informed decisions by providing reliable and valid data.

Purpose of Research Methodology

Research methodology serves several important purposes, including:

- To guide the research process: Research methodology provides a systematic framework for conducting research. It helps researchers to plan their research, define their research questions, and select appropriate methods and techniques for collecting and analyzing data.

- To ensure research quality: Research methodology helps researchers to ensure that their research is rigorous, reliable, and valid. It provides guidelines for minimizing bias and error in data collection and analysis, and for ensuring that research findings are accurate and trustworthy.

- To replicate research: Research methodology provides a clear and detailed account of the research process, making it possible for other researchers to replicate the study and verify its findings.

- To advance knowledge: Research methodology enables researchers to generate new knowledge and to contribute to the body of knowledge in their field. It provides a means for testing hypotheses, exploring new ideas, and discovering new insights.

- To inform decision-making: Research methodology provides evidence-based information that can inform policy and decision-making in a variety of fields, including medicine, public health, education, and business.

Advantages of Research Methodology

Research methodology has several advantages that make it a valuable tool for conducting research in various fields. Here are some of the key advantages of research methodology:

- Systematic and structured approach : Research methodology provides a systematic and structured approach to conducting research, which ensures that the research is conducted in a rigorous and comprehensive manner.

- Objectivity : Research methodology aims to ensure objectivity in the research process, which means that the research findings are based on evidence and not influenced by personal bias or subjective opinions.

- Replicability : Research methodology ensures that research can be replicated by other researchers, which is essential for validating research findings and ensuring their accuracy.

- Reliability : Research methodology aims to ensure that the research findings are reliable, which means that they are consistent and can be depended upon.

- Validity : Research methodology ensures that the research findings are valid, which means that they accurately reflect the research question or hypothesis being tested.

- Efficiency : Research methodology provides a structured and efficient way of conducting research, which helps to save time and resources.

- Flexibility : Research methodology allows researchers to choose the most appropriate research methods and techniques based on the research question, data availability, and other relevant factors.

- Scope for innovation: Research methodology provides scope for innovation and creativity in designing research studies and developing new research techniques.

Research Methodology Vs Research Methods

About the author.

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is research methodology?

The basics of research methodology

Why do you need a research methodology, what needs to be included, why do you need to document your research method, what are the different types of research instruments, qualitative / quantitative / mixed research methodologies, how do you choose the best research methodology for you, frequently asked questions about research methodology, related articles.

When you’re working on your first piece of academic research, there are many different things to focus on, and it can be overwhelming to stay on top of everything. This is especially true of budding or inexperienced researchers.

If you’ve never put together a research proposal before or find yourself in a position where you need to explain your research methodology decisions, there are a few things you need to be aware of.

Once you understand the ins and outs, handling academic research in the future will be less intimidating. We break down the basics below:

A research methodology encompasses the way in which you intend to carry out your research. This includes how you plan to tackle things like collection methods, statistical analysis, participant observations, and more.

You can think of your research methodology as being a formula. One part will be how you plan on putting your research into practice, and another will be why you feel this is the best way to approach it. Your research methodology is ultimately a methodological and systematic plan to resolve your research problem.

In short, you are explaining how you will take your idea and turn it into a study, which in turn will produce valid and reliable results that are in accordance with the aims and objectives of your research. This is true whether your paper plans to make use of qualitative methods or quantitative methods.

The purpose of a research methodology is to explain the reasoning behind your approach to your research - you'll need to support your collection methods, methods of analysis, and other key points of your work.

Think of it like writing a plan or an outline for you what you intend to do.

When carrying out research, it can be easy to go off-track or depart from your standard methodology.

Tip: Having a methodology keeps you accountable and on track with your original aims and objectives, and gives you a suitable and sound plan to keep your project manageable, smooth, and effective.

With all that said, how do you write out your standard approach to a research methodology?

As a general plan, your methodology should include the following information:

- Your research method. You need to state whether you plan to use quantitative analysis, qualitative analysis, or mixed-method research methods. This will often be determined by what you hope to achieve with your research.

- Explain your reasoning. Why are you taking this methodological approach? Why is this particular methodology the best way to answer your research problem and achieve your objectives?

- Explain your instruments. This will mainly be about your collection methods. There are varying instruments to use such as interviews, physical surveys, questionnaires, for example. Your methodology will need to detail your reasoning in choosing a particular instrument for your research.

- What will you do with your results? How are you going to analyze the data once you have gathered it?

- Advise your reader. If there is anything in your research methodology that your reader might be unfamiliar with, you should explain it in more detail. For example, you should give any background information to your methods that might be relevant or provide your reasoning if you are conducting your research in a non-standard way.

- How will your sampling process go? What will your sampling procedure be and why? For example, if you will collect data by carrying out semi-structured or unstructured interviews, how will you choose your interviewees and how will you conduct the interviews themselves?

- Any practical limitations? You should discuss any limitations you foresee being an issue when you’re carrying out your research.

In any dissertation, thesis, or academic journal, you will always find a chapter dedicated to explaining the research methodology of the person who carried out the study, also referred to as the methodology section of the work.

A good research methodology will explain what you are going to do and why, while a poor methodology will lead to a messy or disorganized approach.

You should also be able to justify in this section your reasoning for why you intend to carry out your research in a particular way, especially if it might be a particularly unique method.

Having a sound methodology in place can also help you with the following:

- When another researcher at a later date wishes to try and replicate your research, they will need your explanations and guidelines.

- In the event that you receive any criticism or questioning on the research you carried out at a later point, you will be able to refer back to it and succinctly explain the how and why of your approach.

- It provides you with a plan to follow throughout your research. When you are drafting your methodology approach, you need to be sure that the method you are using is the right one for your goal. This will help you with both explaining and understanding your method.

- It affords you the opportunity to document from the outset what you intend to achieve with your research, from start to finish.

A research instrument is a tool you will use to help you collect, measure and analyze the data you use as part of your research.

The choice of research instrument will usually be yours to make as the researcher and will be whichever best suits your methodology.

There are many different research instruments you can use in collecting data for your research.

Generally, they can be grouped as follows:

- Interviews (either as a group or one-on-one). You can carry out interviews in many different ways. For example, your interview can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. The difference between them is how formal the set of questions is that is asked of the interviewee. In a group interview, you may choose to ask the interviewees to give you their opinions or perceptions on certain topics.

- Surveys (online or in-person). In survey research, you are posing questions in which you ask for a response from the person taking the survey. You may wish to have either free-answer questions such as essay-style questions, or you may wish to use closed questions such as multiple choice. You may even wish to make the survey a mixture of both.

- Focus Groups. Similar to the group interview above, you may wish to ask a focus group to discuss a particular topic or opinion while you make a note of the answers given.

- Observations. This is a good research instrument to use if you are looking into human behaviors. Different ways of researching this include studying the spontaneous behavior of participants in their everyday life, or something more structured. A structured observation is research conducted at a set time and place where researchers observe behavior as planned and agreed upon with participants.

These are the most common ways of carrying out research, but it is really dependent on your needs as a researcher and what approach you think is best to take.

It is also possible to combine a number of research instruments if this is necessary and appropriate in answering your research problem.

There are three different types of methodologies, and they are distinguished by whether they focus on words, numbers, or both.

➡️ Want to learn more about the differences between qualitative and quantitative research, and how to use both methods? Check out our guide for that!

If you've done your due diligence, you'll have an idea of which methodology approach is best suited to your research.

It’s likely that you will have carried out considerable reading and homework before you reach this point and you may have taken inspiration from other similar studies that have yielded good results.

Still, it is important to consider different options before setting your research in stone. Exploring different options available will help you to explain why the choice you ultimately make is preferable to other methods.

If proving your research problem requires you to gather large volumes of numerical data to test hypotheses, a quantitative research method is likely to provide you with the most usable results.

If instead you’re looking to try and learn more about people, and their perception of events, your methodology is more exploratory in nature and would therefore probably be better served using a qualitative research methodology.

It helps to always bring things back to the question: what do I want to achieve with my research?

Once you have conducted your research, you need to analyze it. Here are some helpful guides for qualitative data analysis:

➡️ How to do a content analysis

➡️ How to do a thematic analysis

➡️ How to do a rhetorical analysis

Research methodology refers to the techniques used to find and analyze information for a study, ensuring that the results are valid, reliable and that they address the research objective.

Data can typically be organized into four different categories or methods: observational, experimental, simulation, and derived.

Writing a methodology section is a process of introducing your methods and instruments, discussing your analysis, providing more background information, addressing your research limitations, and more.

Your research methodology section will need a clear research question and proposed research approach. You'll need to add a background, introduce your research question, write your methodology and add the works you cited during your data collecting phase.

The research methodology section of your study will indicate how valid your findings are and how well-informed your paper is. It also assists future researchers planning to use the same methodology, who want to cite your study or replicate it.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

A Comprehensive Guide to Methodology in Research

Table of Contents

Research methodology plays a crucial role in any study or investigation. It provides the framework for collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data, ensuring that the research is reliable, valid, and credible. Understanding the importance of research methodology is essential for conducting rigorous and meaningful research.

In this article, we'll explore the various aspects of research methodology, from its types to best practices, ensuring you have the knowledge needed to conduct impactful research.

What is Research Methodology?

Research methodology refers to the system of procedures, techniques, and tools used to carry out a research study. It encompasses the overall approach, including the research design, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and the interpretation of findings.

Research methodology plays a crucial role in the field of research, as it sets the foundation for any study. It provides researchers with a structured framework to ensure that their investigations are conducted in a systematic and organized manner. By following a well-defined methodology, researchers can ensure that their findings are reliable, valid, and meaningful.

When defining research methodology, one of the first steps is to identify the research problem. This involves clearly understanding the issue or topic that the study aims to address. By defining the research problem, researchers can narrow down their focus and determine the specific objectives they want to achieve through their study.

How to Define Research Methodology

Once the research problem is identified, researchers move on to defining the research questions. These questions serve as a guide for the study, helping researchers to gather relevant information and analyze it effectively. The research questions should be clear, concise, and aligned with the overall goals of the study.

After defining the research questions, researchers need to determine how data will be collected and analyzed. This involves selecting appropriate data collection methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The choice of data collection methods depends on various factors, including the nature of the research problem, the target population, and the available resources.

Once the data is collected, researchers need to analyze it using appropriate data analysis techniques. This may involve statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a combination of both, depending on the nature of the data and the research questions. The analysis of data helps researchers to draw meaningful conclusions and make informed decisions based on their findings.

Role of Methodology in Research

Methodology plays a crucial role in research, as it ensures that the study is conducted in a systematic and organized manner. It provides a clear roadmap for researchers to follow, ensuring that the research objectives are met effectively. By following a well-defined methodology, researchers can minimize bias, errors, and inconsistencies in their study, thus enhancing the reliability and validity of their findings.

In addition to providing a structured approach, research methodology also helps in establishing the reliability and validity of the study. Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the research findings, while validity refers to the accuracy and truthfulness of the findings. By using appropriate research methods and techniques, researchers can ensure that their study produces reliable and valid results, which can be used to make informed decisions and contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

Steps in Choosing the Right Research Methodology

Choosing the appropriate research methodology for your study is a critical step in ensuring the success of your research. Let's explore some steps to help you select the right research methodology:

Identifying the Research Problem

The first step in choosing the right research methodology is to clearly identify and define the research problem. Understanding the research problem will help you determine which methodology will best address your research questions and objectives.

Identifying the research problem involves a thorough examination of the existing literature in your field of study. This step allows you to gain a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge and identify any gaps that your research can fill. By identifying the research problem, you can ensure that your study contributes to the existing body of knowledge and addresses a significant research gap.

Once you have identified the research problem, you need to consider the scope of your study. Are you focusing on a specific population, geographic area, or time frame? Understanding the scope of your research will help you determine the appropriate research methodology to use.

Reviewing Previous Research

Before finalizing the research methodology, it is essential to review previous research conducted in the field. This will allow you to identify gaps, determine the most effective methodologies used in similar studies, and build upon existing knowledge.

Reviewing previous research involves conducting a systematic review of relevant literature. This process includes searching for and analyzing published studies, articles, and reports that are related to your research topic. By reviewing previous research, you can gain insights into the strengths and limitations of different methodologies and make informed decisions about which approach to adopt.

During the review process, it is important to critically evaluate the quality and reliability of the existing research. Consider factors such as the sample size, research design, data collection methods, and statistical analysis techniques used in previous studies. This evaluation will help you determine the most appropriate research methodology for your own study.

Formulating Research Questions

Once the research problem is identified, formulate specific and relevant research questions. These questions will guide your methodology selection process by helping you determine what type of data you need to collect and how to analyze it.

Formulating research questions involves breaking down the research problem into smaller, more manageable components. These questions should be clear, concise, and measurable. They should also align with the objectives of your study and provide a framework for data collection and analysis.

When formulating research questions, consider the different types of data that can be collected, such as qualitative or quantitative data. Depending on the nature of your research questions, you may need to employ different data collection methods, such as interviews, surveys, observations, or experiments. By carefully formulating research questions, you can ensure that your chosen methodology will enable you to collect the necessary data to answer your research questions effectively.

Implementing the Research Methodology

After choosing the appropriate research methodology, it is time to implement it. This stage involves collecting data using various techniques and analyzing the gathered information. Let's explore two crucial aspects of implementing the research methodology:

Data Collection Techniques

Data collection techniques depend on the chosen research methodology. They can include surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or document analysis. Selecting the most suitable data collection techniques will ensure accurate and relevant data for your study.

Data Analysis Methods

Data analysis is a critical part of the research process. It involves interpreting and making sense of the collected data to draw meaningful conclusions. Depending on the research methodology, data analysis methods can include statistical analysis, content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory.

Ensuring the Validity and Reliability of Your Research

In order to ensure the validity and reliability of your research findings, it is important to address these two key aspects:

Understanding Validity in Research

Validity refers to the accuracy and soundness of a research study. It is crucial to ensure that the research methods used effectively measure what they intend to measure. Researchers can enhance validity by using proper sampling techniques, carefully designing research instruments, and ensuring accurate data collection.

Ensuring Reliability in Your Study

Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the research results. It is important to ensure that the research methods and instruments used yield consistent and reproducible results. Researchers can enhance reliability by using standardized procedures, ensuring inter-rater reliability, and conducting pilot studies.

A comprehensive understanding of research methodology is essential for conducting high-quality research. By selecting the right research methodology, researchers can ensure that their studies are rigorous, reliable, and valid. It is crucial to follow the steps in choosing the appropriate methodology, implement the chosen methodology effectively, and address validity and reliability concerns throughout the research process. By doing so, researchers can contribute valuable insights and advances in their respective fields.

You might also like

AI for Meta Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Beyond Google Scholar: Why SciSpace is the best alternative

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is Research Methodology? Definition, Types, and Examples

Research methodology 1,2 is a structured and scientific approach used to collect, analyze, and interpret quantitative or qualitative data to answer research questions or test hypotheses. A research methodology is like a plan for carrying out research and helps keep researchers on track by limiting the scope of the research. Several aspects must be considered before selecting an appropriate research methodology, such as research limitations and ethical concerns that may affect your research.

The research methodology section in a scientific paper describes the different methodological choices made, such as the data collection and analysis methods, and why these choices were selected. The reasons should explain why the methods chosen are the most appropriate to answer the research question. A good research methodology also helps ensure the reliability and validity of the research findings. There are three types of research methodology—quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method, which can be chosen based on the research objectives.

What is research methodology ?

A research methodology describes the techniques and procedures used to identify and analyze information regarding a specific research topic. It is a process by which researchers design their study so that they can achieve their objectives using the selected research instruments. It includes all the important aspects of research, including research design, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and the overall framework within which the research is conducted. While these points can help you understand what is research methodology, you also need to know why it is important to pick the right methodology.

Why is research methodology important?

Having a good research methodology in place has the following advantages: 3

- Helps other researchers who may want to replicate your research; the explanations will be of benefit to them.

- You can easily answer any questions about your research if they arise at a later stage.

- A research methodology provides a framework and guidelines for researchers to clearly define research questions, hypotheses, and objectives.

- It helps researchers identify the most appropriate research design, sampling technique, and data collection and analysis methods.

- A sound research methodology helps researchers ensure that their findings are valid and reliable and free from biases and errors.

- It also helps ensure that ethical guidelines are followed while conducting research.

- A good research methodology helps researchers in planning their research efficiently, by ensuring optimum usage of their time and resources.

Writing the methods section of a research paper? Let Paperpal help you achieve perfection

Types of research methodology.

There are three types of research methodology based on the type of research and the data required. 1

- Quantitative research methodology focuses on measuring and testing numerical data. This approach is good for reaching a large number of people in a short amount of time. This type of research helps in testing the causal relationships between variables, making predictions, and generalizing results to wider populations.

- Qualitative research methodology examines the opinions, behaviors, and experiences of people. It collects and analyzes words and textual data. This research methodology requires fewer participants but is still more time consuming because the time spent per participant is quite large. This method is used in exploratory research where the research problem being investigated is not clearly defined.

- Mixed-method research methodology uses the characteristics of both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies in the same study. This method allows researchers to validate their findings, verify if the results observed using both methods are complementary, and explain any unexpected results obtained from one method by using the other method.

What are the types of sampling designs in research methodology?

Sampling 4 is an important part of a research methodology and involves selecting a representative sample of the population to conduct the study, making statistical inferences about them, and estimating the characteristics of the whole population based on these inferences. There are two types of sampling designs in research methodology—probability and nonprobability.

- Probability sampling

In this type of sampling design, a sample is chosen from a larger population using some form of random selection, that is, every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. The different types of probability sampling are:

- Systematic —sample members are chosen at regular intervals. It requires selecting a starting point for the sample and sample size determination that can be repeated at regular intervals. This type of sampling method has a predefined range; hence, it is the least time consuming.

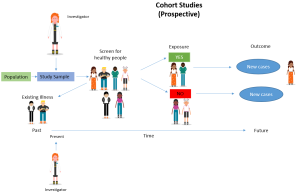

- Stratified —researchers divide the population into smaller groups that don’t overlap but represent the entire population. While sampling, these groups can be organized, and then a sample can be drawn from each group separately.

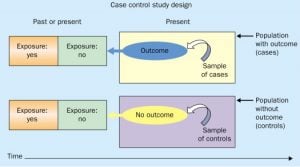

- Cluster —the population is divided into clusters based on demographic parameters like age, sex, location, etc.

- Convenience —selects participants who are most easily accessible to researchers due to geographical proximity, availability at a particular time, etc.

- Purposive —participants are selected at the researcher’s discretion. Researchers consider the purpose of the study and the understanding of the target audience.

- Snowball —already selected participants use their social networks to refer the researcher to other potential participants.

- Quota —while designing the study, the researchers decide how many people with which characteristics to include as participants. The characteristics help in choosing people most likely to provide insights into the subject.

What are data collection methods?

During research, data are collected using various methods depending on the research methodology being followed and the research methods being undertaken. Both qualitative and quantitative research have different data collection methods, as listed below.

Qualitative research 5

- One-on-one interviews: Helps the interviewers understand a respondent’s subjective opinion and experience pertaining to a specific topic or event

- Document study/literature review/record keeping: Researchers’ review of already existing written materials such as archives, annual reports, research articles, guidelines, policy documents, etc.

- Focus groups: Constructive discussions that usually include a small sample of about 6-10 people and a moderator, to understand the participants’ opinion on a given topic.

- Qualitative observation : Researchers collect data using their five senses (sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing).

Quantitative research 6

- Sampling: The most common type is probability sampling.

- Interviews: Commonly telephonic or done in-person.

- Observations: Structured observations are most commonly used in quantitative research. In this method, researchers make observations about specific behaviors of individuals in a structured setting.

- Document review: Reviewing existing research or documents to collect evidence for supporting the research.

- Surveys and questionnaires. Surveys can be administered both online and offline depending on the requirement and sample size.

Let Paperpal help you write the perfect research methods section. Start now!

What are data analysis methods.

The data collected using the various methods for qualitative and quantitative research need to be analyzed to generate meaningful conclusions. These data analysis methods 7 also differ between quantitative and qualitative research.