Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

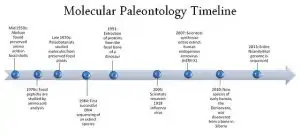

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Prev Med

How to Write a Systematic Review: A Narrative Review

Ali hasanpour dehkordi.

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran

Elaheh Mazaheri

1 Health Information Technology Research Center, Student Research Committee, Department of Medical Library and Information Sciences, School of Management and Medical Information Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Hanan A. Ibrahim

2 Department of International Relations, College of Law, Bayan University, Erbil, Kurdistan, Iraq

Sahar Dalvand

3 MSc in Biostatistics, Health Promotion Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Reza Ghanei Gheshlagh

4 Spiritual Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

In recent years, published systematic reviews in the world and in Iran have been increasing. These studies are an important resource to answer evidence-based clinical questions and assist health policy-makers and students who want to identify evidence gaps in published research. Systematic review studies, with or without meta-analysis, synthesize all available evidence from studies focused on the same research question. In this study, the steps for a systematic review such as research question design and identification, the search for qualified published studies, the extraction and synthesis of information that pertain to the research question, and interpretation of the results are presented in details. This will be helpful to all interested researchers.

A systematic review, as its name suggests, is a systematic way of collecting, evaluating, integrating, and presenting findings from several studies on a specific question or topic.[ 1 ] A systematic review is a research that, by identifying and combining evidence, is tailored to and answers the research question, based on an assessment of all relevant studies.[ 2 , 3 ] To identify assess and interpret available research, identify effective and ineffective health-care interventions, provide integrated documentation to help decision-making, and identify the gap between studies is one of the most important reasons for conducting systematic review studies.[ 4 ]

In the review studies, the latest scientific information about a particular topic is criticized. In these studies, the terms of review, systematic review, and meta-analysis are used instead. A systematic review is done in one of two methods, quantitative (meta-analysis) and qualitative. In a meta-analysis, the results of two or more studies for the evaluation of say health interventions are combined to measure the effect of treatment, while in the qualitative method, the findings of other studies are combined without using statistical methods.[ 5 ]

Since 1999, various guidelines, including the QUORUM, the MOOSE, the STROBE, the CONSORT, and the QUADAS, have been introduced for reporting meta-analyses. But recently the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement has gained widespread popularity.[ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ] The systematic review process based on the PRISMA statement includes four steps of how to formulate research questions, define the eligibility criteria, identify all relevant studies, extract and synthesize data, and deduce and present results (answers to research questions).[ 2 ]

Systematic Review Protocol

Systematic reviews start with a protocol. The protocol is a researcher road map that outlines the goals, methodology, and outcomes of the research. Many journals advise writers to use the PRISMA statement to write the protocol.[ 10 ] The PRISMA checklist includes 27 items related to the content of a systematic review and meta-analysis and includes abstracts, methods, results, discussions, and financial resources.[ 11 ] PRISMA helps writers improve their systematic review and meta-analysis report. Reviewers and editors of medical journals acknowledge that while PRISMA may not be used as a tool to assess the methodological quality, it does help them to publish a better study article [ Figure 1 ].[ 12 ]

Screening process and articles selection according to the PRISMA guidelines

The main step in designing the protocol is to define the main objectives of the study and provide some background information. Before starting a systematic review, it is important to assess that your study is not a duplicate; therefore, in search of published research, it is necessary to review PREOSPERO and the Cochrane Database of Systematic. Sometimes it is better to search, in four databases, related systematic reviews that have already been published (PubMed, Web of Sciences, Scopus, Cochrane), published systematic review protocols (PubMed, Web of Sciences, Scopus, Cochrane), systematic review protocols that have already been registered but have not been published (PROSPERO, Cochrane), and finally related published articles (PubMed, Web of Sciences, Scopus, Cochrane). The goal is to reduce duplicate research and keep up-to-date systematic reviews.[ 13 ]

Research questions

Writing a research question is the first step in systematic review that summarizes the main goal of the study.[ 14 ] The research question determines which types of studies should be included in the analysis (quantitative, qualitative, methodic mix, review overviews, or other studies). Sometimes a research question may be broken down into several more detailed questions.[ 15 ] The vague questions (such as: is walking helpful?) makes the researcher fail to be well focused on the collected studies or analyze them appropriately.[ 16 ] On the other hand, if the research question is rigid and restrictive (e.g., walking for 43 min and 3 times a week is better than walking for 38 min and 4 times a week?), there may not be enough studies in this area to answer this question and hence the generalizability of the findings to other populations will be reduced.[ 16 , 17 ] A good question in systematic review should include components that are PICOS style which include population (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), outcome (O), and setting (S).[ 18 ] Regarding the purpose of the study, control in clinical trials or pre-poststudies can replace C.[ 19 ]

Search and identify eligible texts

After clarifying the research question and before searching the databases, it is necessary to specify searching methods, articles screening, studies eligibility check, check of the references in eligible studies, data extraction, and data analysis. This helps researchers ensure that potential biases in the selection of potential studies are minimized.[ 14 , 17 ] It should also look at details such as which published and unpublished literature have been searched, how they were searched, by which mechanism they were searched, and what are the inclusion and exclusion criteria.[ 4 ] First, all studies are searched and collected according to predefined keywords; then the title, abstract, and the entire text are screened for relevance by the authors.[ 13 ] By screening articles based on their titles, researchers can quickly decide on whether to retain or remove an article. If more information is needed, the abstracts of the articles will also be reviewed. In the next step, the full text of the articles will be reviewed to identify the relevant articles, and the reason for the removal of excluded articles is reported.[ 20 ] Finally, it is recommended that the process of searching, selecting, and screening articles be reported as a flowchart.[ 21 ] By increasing research, finding up-to-date and relevant information has become more difficult.[ 22 ]

Currently, there is no specific guideline as to which databases should be searched, which database is the best, and how many should be searched; but overall, it is advisable to search broadly. Because no database covers all health topics, it is recommended to use several databases to search.[ 23 ] According to the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews scale (AMSTAR) at least two databases should be searched in systematic and meta-analysis, although more comprehensive and accurate results can be obtained by increasing the number of searched databases.[ 24 ] The type of database to be searched depends on the systematic review question. For example, in a clinical trial study, it is recommended that Cochrane, multi-regional clinical trial (mRCTs), and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform be searched.[ 25 ]

For example, MEDLINE, a product of the National Library of Medicine in the United States of America, focuses on peer-reviewed articles in biomedical and health issues, while Embase covers the broad field of pharmacology and summaries of conferences. CINAHL is a great resource for nursing and health research and PsycINFO is a great database for psychology, psychiatry, counseling, addiction, and behavioral problems. Also, national and regional databases can be used to search related articles.[ 26 , 27 ] In addition, the search for conferences and gray literature helps to resolve the file-drawn problem (negative studies that may not be published yet).[ 26 ] If a systematic review is carried out on articles in a particular country or region, the databases in that region or country should also be investigated. For example, Iranian researchers can use national databases such as Scientific Information Database and MagIran. Comprehensive search to identify the maximum number of existing studies leads to a minimization of the selection bias. In the search process, the available databases should be used as much as possible, since many databases are overlapping.[ 17 ] Searching 12 databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, GHL, VHL, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Clinical trials.gov, mRCTs, POPLINE, and SIGLE) covers all articles published in the field of medicine and health.[ 25 ] Some have suggested that references management software be used to search for more easy identification and removal of duplicate articles from several different databases.[ 20 ] At least one search strategy is presented in the article.[ 21 ]

Quality assessment

The methodological quality assessment of articles is a key step in systematic review that helps identify systemic errors (bias) in results and interpretations. In systematic review studies, unlike other review studies, qualitative assessment or risk of bias is required. There are currently several tools available to review the quality of the articles. The overall score of these tools may not provide sufficient information on the strengths and weaknesses of the studies.[ 28 ] At least two reviewers should independently evaluate the quality of the articles, and if there is any objection, the third author should be asked to examine the article or the two researchers agree on the discussion. Some believe that the study of the quality of studies should be done by removing the name of the journal, title, authors, and institutions in a Blinded fashion.[ 29 ]

There are several ways for quality assessment, such as Sack's quality assessment (1988),[ 30 ] overview quality assessment questionnaire (1991),[ 31 ] CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Program),[ 32 ] and AMSTAR (2007),[ 33 ] Besides, CASP,[ 34 ] the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,[ 35 ] and the Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information checklists.[ 30 , 36 ] However, it is worth mentioning that there is no single tool for assessing the quality of all types of reviews, but each is more applicable to some types of reviews. Often, the STROBE tool is used to check the quality of articles. It reviews the title and abstract (item 1), introduction (items 2 and 3), implementation method (items 4–12), findings (items 13–17), discussion (Items 18–21), and funding (item 22). Eighteen items are used to review all articles, but four items (6, 12, 14, and 15) apply in certain situations.[ 9 ] The quality of interventional articles is often evaluated by the JADAD tool, which consists of three sections of randomization (2 scores), blinding (2 scores), and patient count (1 scores).[ 29 ]

Data extraction

At this stage, the researchers extract the necessary information in the selected articles. Elamin believes that reviewing the titles and abstracts and data extraction is a key step in the review process, which is often carried out by two of the research team independently, and ultimately, the results are compared.[ 37 ] This step aimed to prevent selection bias and it is recommended that the chance of agreement between the two researchers (Kappa coefficient) be reported at the end.[ 26 ] Although data collection forms may differ in systematic reviews, they all have information such as first author, year of publication, sample size, target community, region, and outcome. The purpose of data synthesis is to collect the findings of eligible studies, evaluate the strengths of the findings of the studies, and summarize the results. In data synthesis, we can use different analysis frameworks such as meta-ethnography, meta-analysis, or thematic synthesis.[ 38 ] Finally, after quality assessment, data analysis is conducted. The first step in this section is to provide a descriptive evaluation of each study and present the findings in a tabular form. Reviewing this table can determine how to combine and analyze various studies.[ 28 ] The data synthesis approach depends on the nature of the research question and the nature of the initial research studies.[ 39 ] After reviewing the bias and the abstract of the data, it is decided that the synthesis is carried out quantitatively or qualitatively. In case of conceptual heterogeneity (systematic differences in the study design, population, and interventions), the generalizability of the findings will be reduced and the study will not be meta-analysis. The meta-analysis study allows the estimation of the effect size, which is reported as the odds ratio, relative risk, hazard ratio, prevalence, correlation, sensitivity, specificity, and incidence with a confidence interval.[ 26 ]

Estimation of the effect size in systematic review and meta-analysis studies varies according to the type of studies entered into the analysis. Unlike the mean, prevalence, or incidence index, in odds ratio, relative risk, and hazard ratio, it is necessary to combine logarithm and logarithmic standard error of these statistics [ Table 1 ].

Effect size in systematic review and meta-analysis

OR=Odds ratio; RR=Relative risk; RCT= Randomized controlled trial; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; PLR: positive likelihood ratio; NLR: negative likelihood ratio; DOR: diagnostic odds ratio

Interpreting and presenting results (answers to research questions)

A systematic review ends with the interpretation of results. At this stage, the results of the study are summarized and the conclusions are presented to improve clinical and therapeutic decision-making. A systematic review with or without meta-analysis provides the best evidence available in the hierarchy of evidence-based practice.[ 14 ] Using meta-analysis can provide explicit conclusions. Conceptually, meta-analysis is used to combine the results of two or more studies that are similar to the specific intervention and the similar outcomes. In meta-analysis, instead of the simple average of the results of various studies, the weighted average of studies is reported, meaning studies with larger sample sizes account for more weight. To combine the results of various studies, we can use two models of fixed and random effects. In the fixed-effect model, it is assumed that the parameters studied are constant in all studies, and in the random-effect model, the measured parameter is assumed to be distributed between the studies and each study has measured some of it. This model offers a more conservative estimate.[ 40 ]

Three types of homogeneity tests can be used: (1) forest plot, (2) Cochrane's Q test (Chi-squared), and (3) Higgins I 2 statistics. In the forest plot, more overlap between confidence intervals indicates more homogeneity. In the Q statistic, when the P value is less than 0.1, it indicates heterogeneity exists and a random-effect model should be used.[ 41 ] Various tests such as the I 2 index are used to determine heterogeneity, values between 0 and 100; the values below 25%, between 25% and 50%, and above 75% indicate low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively.[ 26 , 42 ] The results of the meta-analyzing study are presented graphically using the forest plot, which shows the statistical weight of each study with a 95% confidence interval and a standard error of the mean.[ 40 ]

The importance of meta-analyses and systematic reviews in providing evidence useful in making clinical and policy decisions is ever-increasing. Nevertheless, they are prone to publication bias that occurs when positive or significant results are preferred for publication.[ 43 ] Song maintains that studies reporting a certain direction of results or powerful correlations may be more likely to be published than the studies which do not.[ 44 ] In addition, when searching for meta-analyses, gray literature (e.g., dissertations, conference abstracts, or book chapters) and unpublished studies may be missed. Moreover, meta-analyses only based on published studies may exaggerate the estimates of effect sizes; as a result, patients may be exposed to harmful or ineffective treatment methods.[ 44 , 45 ] However, there are some tests that can help in detecting negative expected results that are not included in a review due to publication bias.[ 46 ] In addition, publication bias can be reduced through searching for data that are not published.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have certain advantages; some of the most important ones are as follows: examining differences in the findings of different studies, summarizing results from various studies, increased accuracy of estimating effects, increased statistical power, overcoming problems related to small sample sizes, resolving controversies from disagreeing studies, increased generalizability of results, determining the possible need for new studies, overcoming the limitations of narrative reviews, and making new hypotheses for further research.[ 47 , 48 ]

Despite the importance of systematic reviews, the author may face numerous problems in searching, screening, and synthesizing data during this process. A systematic review requires extensive access to databases and journals that can be costly for nonacademic researchers.[ 13 ] Also, in reviewing the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the inevitable mindsets of browsers may be involved and the criteria are interpreted differently from each other.[ 49 ] Lee refers to some disadvantages of these studies, the most significant ones are as follows: a research field cannot be summarized by one number, publication bias, heterogeneity, combining unrelated things, being vulnerable to subjectivity, failing to account for all confounders, comparing variables that are not comparable, just focusing on main effects, and possible inconsistency with results of randomized trials.[ 47 ] Different types of programs are available to perform meta-analysis. Some of the most commonly used statistical programs are general statistical packages, including SAS, SPSS, R, and Stata. Using flexible commands in these programs, meta-analyses can be easily run and the results can be readily plotted out. However, these statistical programs are often expensive. An alternative to using statistical packages is to use programs designed for meta-analysis, including Metawin, RevMan, and Comprehensive Meta-analysis. However, these programs may have limitations, including that they can accept few data formats and do not provide much opportunity to set the graphical display of findings. Another alternative is to use Microsoft Excel. Although it is not a free software, it is usually found in many computers.[ 20 , 50 ]

A systematic review study is a powerful and valuable tool for answering research questions, generating new hypotheses, and identifying areas where there is a lack of tangible knowledge. A systematic review study provides an excellent opportunity for researchers to improve critical assessment and evidence synthesis skills.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Strategies to Find Sources

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Strategies to Find Sources

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- How to Pick a Topic

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

The Research Process

![review of past research relevant to the paper brainly Interative Litearture Review Research Process image (Planning, Searching, Organizing, Analyzing and Writing [repeat at necessary]](https://libapps.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/64450/images/ResearchProcess.jpg)

Planning : Before searching for articles or books, brainstorm to develop keywords that better describe your research question.

Searching : While searching, take note of what other keywords are used to describe your topic, and use them to conduct additional searches

♠ Most articles include a keyword section

♠ Key concepts may change names throughout time so make sure to check for variations

Organizing : Start organizing your results by categories/key concepts or any organizing principle that make sense for you . This will help you later when you are ready to analyze your findings

Analyzing : While reading, start making notes of key concepts and commonalities and disagreement among the research articles you find.

♠ Create a spreadsheet to record what articles you are finding useful and why.

♠ Create fields to write summaries of articles or quotes for future citing and paraphrasing .

Writing : Synthesize your findings. Use your own voice to explain to your readers what you learned about the literature on your topic. What are its weaknesses and strengths? What is missing or ignored?

Repeat : At any given time of the process, you can go back to a previous step as necessary.

Advanced Searching

All databases have Help pages that explain the best way to search their product. When doing literature reviews, you will want to take advantage of these features since they can facilitate not only finding the articles that you really need but also controlling the number of results and how relevant they are for your search. The most common features available in the advanced search option of databases and library online catalogs are:

- Boolean Searching (AND, OR, NOT): Allows you to connect search terms in a way that can either limit or expand your search results

- Proximity Searching (N/# or W/#): Allows you to search for two or more words that occur within a specified number of words (or fewer) of each other in the database

- Limiters/Filters : These are options that let you control what type of document you want to search: article type, date, language, publication, etc.

- Question mark (?) or a pound sign (#) for wildcard: Used for retrieving alternate spellings of a word: colo?r will retrieve both the American spelling "color" as well as the British spelling "colour."

- Asterisk (*) for truncation: Used for retrieving multiple forms of a word: comput* retrieves computer, computers, computing, etc.

Want to keep track of updates to your searches? Create an account in the database to receive an alert when a new article is published that meets your search parameters!

- EBSCOhost Advanced Search Tutorial Tips for searching a platform that hosts many library databases

- Library's General Search Tips Check the Search tips to better used our library catalog and articles search system

- ProQuest Database Search Tips Tips for searching another platform that hosts library databases

There is no magic number regarding how many sources you are going to need for your literature review; it all depends on the topic and what type of the literature review you are doing:

► Are you working on an emerging topic? You are not likely to find many sources, which is good because you are trying to prove that this is a topic that needs more research. But, it is not enough to say that you found few or no articles on your topic in your field. You need to look broadly to other disciplines (also known as triangulation ) to see if your research topic has been studied from other perspectives as a way to validate the uniqueness of your research question.

► Are you working on something that has been studied extensively? Then you are going to find many sources and you will want to limit how far back you want to look. Use limiters to eliminate research that may be dated and opt to search for resources published within the last 5-10 years.

- << Previous: How to Pick a Topic

- Next: Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

5 Reasons the Literature Review Is Crucial to Your Paper

3-minute read

- 8th November 2016

People often treat writing the literature review in an academic paper as a formality. Usually, this means simply listing various studies vaguely related to their work and leaving it at that.

But this overlooks how important the literature review is to a well-written experimental report or research paper. As such, we thought we’d take a moment to go over what a literature review should do and why you should give it the attention it deserves.

What Is a Literature Review?

Common in the social and physical sciences, but also sometimes required in the humanities, a literature review is a summary of past research in your subject area.

Sometimes this is a standalone investigation of how an idea or field of inquiry has developed over time. However, more usually it’s the part of an academic paper, thesis or dissertation that sets out the background against which a study takes place.

There are several reasons why we do this.

Reason #1: To Demonstrate Understanding

In a college paper, you can use a literature review to demonstrate your understanding of the subject matter. This means identifying, summarizing and critically assessing past research that is relevant to your own work.

Reason #2: To Justify Your Research

The literature review also plays a big role in justifying your study and setting your research question . This is because examining past research allows you to identify gaps in the literature, which you can then attempt to fill or address with your own work.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Reason #3: Setting a Theoretical Framework

It can help to think of the literature review as the foundations for your study, since the rest of your work will build upon the ideas and existing research you discuss therein.

A crucial part of this is formulating a theoretical framework , which comprises the concepts and theories that your work is based upon and against which its success will be judged.

Reason #4: Developing a Methodology

Conducting a literature review before beginning research also lets you see how similar studies have been conducted in the past. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research, you can thus make sure you adopt the most appropriate methods, data sources and analytical techniques for your own work.

Reason #5: To Support Your Own Findings

The significance of any results you achieve will depend to some extent on how they compare to those reported in the existing literature. When you come to write up your findings, your literature review will therefore provide a crucial point of reference.

If your results replicate past research, for instance, you can say that your work supports existing theories. If your results are different, though, you’ll need to discuss why and whether the difference is important.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

What is a content editor.

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Welcome to 2024! Happy New Year!

Research Writing ~ How to Write a Research Paper

- Choosing A Topic

- Critical Thinking

- Domain Names

- Starting Your Research

- Writing Tips

- Parts of the Paper

- Edit & Rewrite

- Citations This link opens in a new window

Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea and how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of you topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose, focus, and structure for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writers viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of thesis statements from Purdue OWL. . .

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . . from The Writing Center at UNC-Chapel Hill More about summarizing. . . from the Center for Writing Studies at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction. Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.