- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Plagiarism in Research — The Complete Guide [eBook]

Table of Contents

Plagiarism can be described as the not-so-subtle art of stealing an already existing work, violating the principles of academic integrity and fairness. Well, there's no denying that we see further by standing on the shoulders of giants, and when it comes to constructing a research prose, we often need to look at the world through their lens. However, in this process, many students and researchers, knowingly or otherwise, resort to plagiarism.

In many instances, plagiarism is intentional, whether through direct copying or paraphrasing. Unfortunately, there are also times when it happens unintentionally. Regardless of the intent, plagiarism goes against the ethos of the scientific world and is considered a severe moral and disciplinary offense.

The good news is that you can avoid plagiarism and even work around it. So, if you're keen on publishing unplagiarized papers and maintaining academic integrity, you've come to the right place.

With this comprehensive ebook on plagiarism, we intend to help you understand what constitutes plagiarism in research, why it happens, plagiarism concepts and types, how you can prevent it, and much more.

What is plagiarism?

Plagiarism is defined as representing a part of or the entirety of someone else's work as your own. Whether published or unpublished, this could be ideas, text verbatim, infographics, etc. It is no different in the academic writing, either. However, it is not considered plagiarism if most of your work is original and the referred part is diligently cited.

The degree of plagiarism can vary from discipline to discipline. Like in mathematics or engineering, there are times when you have to copy and paste entire equations or proofs, which can take a significant chunk of your paper. Again, that is not constituted plagiarism, provided there's an analysis or rebuttal to it.

That said, there are some objective parameters defining plagiarism. Get to know them, and your life as a researcher will be much smoother.

Common types of plagiarism

Plagiarism often creeps into academic works in various forms, from complete plagiarism to accidental plagiarism.

The types of plagiarism varies depending on the two critical aspects — the writer's intention and the degree to which the prose is plagiarized. These aspects help institutions and publishers define plagiarism types more accurately.

The agreed-upon forms of plagiarism that occur in research writing include:

1. Global or Complete Plagiarism

Global or Complete plagiarism is inarguably the most severe form of plagiarism — It is as good as stealing. It happens when an author blatantly copies somebody else's work in its entirety and passes it on as their own.

Since complete plagiarism is always committed deliberately and disguises the ownership of the work, it is directly recognized under copyright violation and can lead to intellectual property abuse and legal battles. That, along with irredeemable repercussions like a damaged reputation, getting expelled, or losing your job.

2. Verbatim or Direct Plagiarism

Verbatim or direct plagiarism happens when you copy a part of someone else's work, word-to-word, without providing adequate credits or attributions. The ideas, structure, and diction in your work would match the original author's work. Even if you were to change a few words or the position of sentences here and there, the final result remains the same.

The best way to avoid this is to minimize copy-pasting entire paragraphs and use it only when the situation calls for it. And when you do so, use quotation marks and in-text citations, crediting the original source.

3. Source-based Plagiarism

Source-based plagiarism results from an author trying to mislead or disguise the natural source of their work. Say you write a paper, giving enough citations, but when the editor or peer reviewers try to cross-check your references, they find a dead end or incorrect information. Another instance is when you use both primary and secondary data to support your argument but only cite the former with no reference for the latter.

In both cases, the information provided is either irrelevant or misleading. You may have cited it, but it does not support the text completely.

Similarly, another type of plagiarism is called data manipulation and counterfeiting . Data Manipulation is creating your own data and results. In contrast, data counterfeiting is skipping or adultering the key findings to suit your expected outcomes.

Using misinformed sources in a research study constitutes grave violations and offenses. Particularly in the medical field, it can lead to legal issues such as wrong data presentation. Its interpretation can lead to false clinical trials, which can have grave consequences.

4. Paraphrasing Plagiarism

Paraphrasing plagiarism is one of the more common types of plagiarism. It refers to when an author copies ideas, thoughts, and inferences, rephrases sentences, and then claims ownership.

Compared to verbatim, paraphrasing plagiarism involves changing words, sentences, semantics or translating texts. The general idea or the topic of the thesis, however, remains the same and as clever as it may seem, it is straightforward to detect.

More often authors commit paraphrasing by reading a few sources and writing them in their own words without due citation. This can lead the reader to believe that the idea was the author's own when it wasn’t.

5. Mosaic or Patchwork Plagiarism

One of the more mischievous ways to abstain from writing original work is mosaic plagiarism. Patchwork or mosaic plagiarism occurs when an author stitches together a research paper by lending pieces from multiple sources and weaving them as their creation. Sure, the author can add a few new words and phrases, but the meat of the paper is stolen.

It’s common for authors to refer to various sources during the research. But to patch them together and form a new paper from them is wrong.

Mosaic plagiarism can be difficult to detect, so authors, too confident in themselves, often resort to it. However, these days, there are plenty of online tools like Turnitin, Enago, and EasyBib that identify patchwork and correctly point to the sources from which you have borrowed.

6. Ghostwriting

Outside of the academic world, ghostwriting is entirely acceptable. Leaders do it, politicians do it, and artists do it. In academia, however, ghostwriting is a breach of conduct that tarnishes the integrity of a student or a researcher.

Ghostwriting is the act of using an unacknowledged person’s assistance to complete a paper. This happens in two ways — when an author has their paper’s foundation laid out but pays someone else to write, edit, and proofread. The other is when they pay someone to write the whole article from scratch.

In either case, it’s utterly unacceptable since the whole point of a paper is to exhibit an author's original thoughts presented by them. Ghostwriting, thus, raises a serious question about the academic capabilities of an author.

7. Self-plagiarism

This may surprise many, but rehashing previous works, even if they are your own, is also considered plagiarism. The biggest reason why self-plagiarism is a fallacy is because you’re trying to claim credit for something that you have already received credit for.

Authors often borrow their past data or experiment results, use them in their current work, and present them as brand new. Some may even plagiarize old published works' ideas, cues, or phrases.

The degree to which self-plagiarism is still under debate depends on the volume of work that has been copied. Additionally, many academic and non-academic journals have devised a fixed ratio on what percentage of self-plagiarism is acceptable. Unless you have made a proper declaration through citations and quotation marks about old data usage, it will fall under the scope of self-plagiarism.

8. Accidental Plagiarism

Apart from the intentional forms of plagiarism, there’s also accidental plagiarism. As the name suggests, it happens inadvertently. Unwitting paraphrasing, missing in-text or end-of-text citations, or not using quotation blocks falls under the same criteria.

While writing your academic papers, you have to stay cautious to avoid accidental plagiarism. The best way to do this is by going through your article thoroughly. Proofread as if your life depended on it, and check whether you’ve given citations where required.

Why is it important to avoid research plagiarism?

As a scholar, you must be aware that the sole purpose of any article or academic writing is to present an original idea to its readers. When the prose is plagiarized, it removes any credibility from the author, discredits the source, and leaves the reader misinformed which goes against the ethos of academic institutions.

Here are the few reasons why you should avoid research plagiarism:

Critical analysis is important

While writing research papers, an author must dive deep into finding various sources, like scholarly articles, especially peer-reviewed ones. You are expected to examine the sources keenly to understand the gaps in the chosen topic and formulate your research questions.

Crafting critical questions related to the field of study is essential as it displays your understanding and the analysis you employed to decipher the problems in the chosen topic. When you do this, your chances of being published improve, and it’s also good for your long-term career growth.

Streamlined scholarly communication

An extended form of scholarly communication is established when you respond and craft your academic work based on what others have previously done in a particular domain. By appropriately using others' work, i.e., through citations, you acknowledge the tasks done before you and how they helped shape your work. Moreover, citations expand the doorway for readers to learn more about a topic from the beginning to the current state. Plagiarism prevents this.

Credibility in originality

Originality is invaluable in the research community. From your thesis topic and fresh methodology to new data, conclusion, and tone of writing, the more original your paper is, the more people are intrigued by it. And as long as your paper is backed by credible sources, it further solidifies your academic integrity. Plagiarism can hinder these.

How does plagiarism happen?

Even though plagiarism is a cardinal sin and plagiarized academic writing is consistently rejected, it still happens. So the question is, what makes people resort to plagiarism?

Some of the reasons why authors choose the plagiarism include:

- Lack of knowledge about plagiarism

- Accidentally copying a work

- Forgetting to cite a source

- Desire to excel among peers

- A false belief that no one will catch them

- No interest in academic work and just taking that as an assignment

- Using shortcuts in the form of self-plagiarism

- Fear of failing

Whatever the reason an author may have, plagiarism can never be justified. It is seen as an unfair advantage and disrespect to those who have put in the blood, sweat, and tears into doing their due diligence. Additionally, remember that readers, universities, or publishers are only interested in your genuine ideas, and your evaluation, as an author, is done based on that.

Related Article: Citation Machine Alternatives — Top citation tools 2023

Consequences of plagiarism

We have reiterated enough that plagiarism is objectionable and has consequences. But what exactly are the consequences? Well, that depends on who the author is and the type of plagiarism.

For minor offenses like accidental plagiarism or missing citations, a slap on the wrist in the form of feedback from the editor or peers is the norm. For major cases, let’s take a look:

For students

- Poor grades

Even if you are a first-timer, your professor may choose to fail you, which can have a detrimental effect on your scores.

- Failing a course

It is not rare for professors to fail Ph.D. and graduate students when caught plagiarizing. Not only does this hurt your academics, but it also extends the duration of your study by a year.

- Disciplinary action

Every university or academic institution has strict policies and regulations regarding plagiarism. If caught, an author may have to face the academic review committee to decide their future. The results seen in general cases range from poor grades, failure for a year, or being banished from any academic or research-related work.

- Expulsion from the university

A university may resort to expulsion only in the worst of cases, like copyright violation or Intellectual Property theft.

- Tarnished academic reputation

This just might be the most consequential of all scenarios. It takes a lifetime to build a great impression but a few seconds to tarnish it. Many academics lose their peers' trust and find it hard to recover. Moreover, background checks for future jobs or fellowships become a nightmare.

For universities

A university is built on reputation. Letting plagiarism slide is the quickest way to tarnish its reputation. This leads to lesser interest from top talent and publishers and trouble finding grant money.

Prospective students turning away from a university means losing out on tuition money. This further drives experienced faculty away. And the cycle continues.

For researchers

- Legal battles

Since it falls under copyright infringement, researchers may face legal battles if their academic work is believed to be plagiarized. There is no shortage of case studies, like those of Doris Kearns Goodwin or Mark Chabedi, where authors, without permission, used another person's work and claimed it to be their own. In all these instances, they faced legal issues that led to fines, barred from writing and research, and sometimes, imprisonment even.

- Professional reputation

Publishers and journals will not engage authors with a past of plagiarism to produce content under their brand name. Also, if the author is a professor or a fellow, it can lead to contract termination.

How to avoid plagiarism in research?

The simplest way to avoid plagiarism would be to put in the work. Do original research, collect new data, and derive new conclusions. If you use references, keep track of each and every single one and cite them in your paper.

To ensure that your academic writing or research paper is unique and free from any type of plagiarism, incorporate the following tips:

- Pay adequate attention to your references

Writing a paper requires extraordinary research. So, it’s understandable when researchers sometimes lose track of their references. This often leads to accidental plagiarism.

So, instead of falling into this trap, maintain lists or take notes of your reference while doing your research. This will help you when you’re writing your citations.

- Find credible sources

Always refer to credible sources, whether a paper, a conference proceeding or an infographic. These will present unbiased evidence and accurate experimentation results with facts backing the evidence presented by your paper.

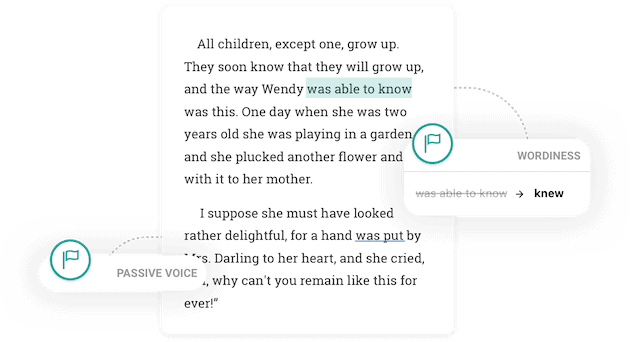

- Proper use of paraphrasing, quotations, and citations

It’s borderline impossible to avoid using direct references in your paper, especially if you’re providing a critical analysis or a rebuttal to an already existing article. So, to avoid getting prosecuted, use quotation marks when using a text verbatim.

In case you’re paraphrasing, use citations so that everyone knows that it’s not your idea. Credit the original author and a secondary source, if any. Publishers usually have guidelines about how to cite. There are many different styles like APA, MLA, Chicago, etc. Be on top of what your publisher demands.

Usually, it is observed that readers or the audience have a greater inclination towards paraphrasing than the quotes, especially if it is bulky sections. The reason is obvious: paraphrasing displays your understanding of the original work's meaning and interpretation, uniquely suiting the current state of affairs.

- Review and recheck your work multiple times

Before submitting the final, you must subject your work to scrutiny. Multiple times at that. The more you do it, the less your chances of falling under accidental plagiarism. To ensure that your final work does not constitute any types of plagiarism, ensure that:

- There are no misplaced or missed citations

- The paraphrased text does not closely resemble the original text

- You don’t have any wrongful references

- You’re not missing quotation marks or failing to provide the author's credentials after quotation marks

- You use a plagiarism checker

More on how to avoid plagiarism .

On top of these, read your university or your publisher’s policies. All of them have their sets of rules about what’s acceptable and what’s not. They also define the punishment for any offense, factoring in its degree.

- Use Online Tools

After receiving your article, most universities, publishers, and other institutions will run it through plagiarism checkers, including AI detectors , to detect all types of plagiarism. These plagiarism checkers function based on drawing similarities between your article and previously published works present in their database. If found similar, your paper is deemed plagiarized.

You can always save yourself from embarrassment by staying a step ahead. Use a plagiarism checker before you submit your paper. Using plagiarism checker tools, you can quickly identify if you have committed plagiarism. Then, no one except you will know about it, and you will have a chance to correct yourself.

Best Plagiarism Checkers in 2023

Plagiarism checkers are an incredibly convenient tool for improving academic writing. Therefore, here are some of the best plagiarism checkers for academic writing.

Turnitin's iThenticate

This is one of the best plagiarism checker for your academic paper and a good fit for academic writers, researchers, and scholars.

Turnitin’s iThenticare claims to cross-check your paper against 99 billion+ current and archived web pages, 1.8 billion student papers, and best-in-class scholarly content from top publishers in every major discipline and dozens of languages.

The iThenticate plagiarism checker is now available on SciSpace. ( Instructions on how to use it .)

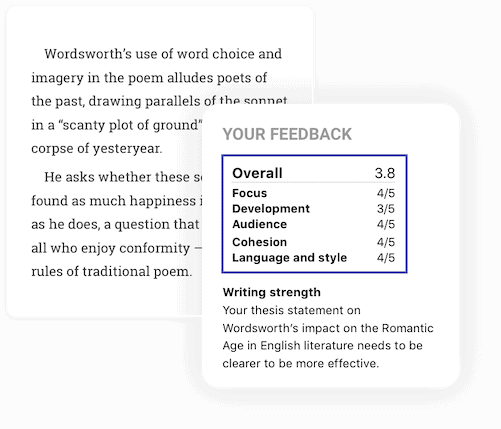

Grammarly serves as a one-stop solution for better writing. Through Grammarly, you can make your paper have fewer grammatical errors, better clarity, and, yes, be plagiarism-free.

Grammarly's plagiarism checker compares your paper to billions of web pages and existing papers online. It points out all the sentences which need a citation, giving you the original source as well. On top of this, Grammarly also rates your document for an originality score.

ProWritingAid

ProWritingAid is another AI writing assistant that offers a plethora of tools to better your document. One of its paid services include a ProWritingAid Plagiarism Checker that helps authors find out how much of their work is plagiarized.

Once you scan your document, the plagiarism checker gives you details like the percentage of non-original text, how much of that is quoted, and how much is not. It will also give you links so you can cite them as required.

EasyBib Plagiarism Checker

EasyBib Plagiarism Checker compares your writing sample with billions of available sources online to detect plagiarism at every level. You'll be notified which phrases are too similar to current research and literature, prompting a possible rewrite or additional citation.

Moreover, you'll get feedback on your paper's inconsistencies, such as changes in text, formatting, or style. These small details could suggest possible plagiarism within your assignment.

Plagiarism CheckerX

Working on the same principle of scanning and matching against various sources, the critical aspect of Plagiarism CheckerX is that you can download and use it whenever you wish. It is slightly faster than others and never stores your data, so you can stay assured of any data loss.

Compilatio Magister

Compilatio Magister is a plagiarism checker designed explicitly for teaching professionals. It lets you access turnkey educational resources, check for plagiarism against thousands of documents, and seek reliable and accurate analysis reports.

Quick Wrap Up

In the world of academia, the spectre of plagiarism lurks but fear not, for armed with awareness and right plagiarism checkers, you have the power to conquer this foe.

Even though plenty of students or researchers believe they can get away with it, it’s never the case. You owe it to yourself and everyone who has invested time and resources in you to publish original, plagiarism-free research work every time.

Throughout this eBook, we have explored the depths of plagiarism, unraveling its consequences and the importance of originality. Many universities have specific classes and workshops discussing plagiarism to create ample awareness of the subject. Thus, you should continue to be honourable in this regard and write papers from the heart.

Hey there! We encourage you to visit our SciSpace discover page to explore how our suite of products can make research workflows easier and allow you to spend more time advancing science.

With the best-in-class solution, you can manage everything from literature search and discovery to profile management, research writing, and much more.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to paraphrase without plagiarizing.

- Understand the original text completely.

- Write the idea in your own words without looking at the original text.

- Change the structure of sentences, not just individual words.

- Use synonyms wisely and ensure the context remains the same.

- Lastly, always cite the original source.

Even when paraphrasing, it's important to attribute ideas to the original author.

2. How to avoid plagiarism in research?

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism.

- Always give proper credit to the original authors when quoting or paraphrasing their work.

- Use plagiarism checker tools to ensure your work is original.

- Keep track of your sources throughout your research.

- Quote and paraphrase accurately.

3. Examples of plagiarism?

- Copying and pasting text directly from a source without quotation or citation.

- Paraphrasing someone else's work without correct citation.

- Presenting someone else's work or ideas as your own.

- Recycling or self-plagiarism, where you mention your previous work without citing it.

4. How much plagiarism is allowed in a research paper?

In the academic world, the goal is always to strive for 0% plagiarism. However, sometimes, minor plagiarism can occur unintentionally, such as when common phrases are matched in plagiarism software. Most institutions and publishers will allow a small percentage, typically under 10%, for such instances. Remember, this doesn't mean you can deliberately plagiarize 10% of your work.

5. What are the four types of plagiarism?

- Direct Plagiarism definition: This occurs when one directly copies someone else's work word-for-word without giving credit.

- Mosaic Plagiarism definition: This happens when someone borrows phrases from a source without using quotation marks, or finds synonyms for the author's language while keeping the same general structure and meaning.

- Accidental Plagiarism definition: This happens when a person neglects to cite their sources, or misquotes their sources, or unintentionally paraphrases a source by using similar words, groupings, or phrases without attribution.

- Self-Plagiarism definition: This happens when someone recycles their own work from a previous paper or study and presents it as new content without citing the original.

6. How much copying is considered plagiarism?

Any amount of copying can be considered plagiarism if you're presenting someone else's work as your own without attribution. Even a single sentence copied without proper citation can be seen as plagiarism. The key is to always give credit where it's due.

7. How to check plagiarism in a research paper?

There are numerous online tools and software that you can use to check plagiarism in a research paper. Some popular ones include Grammarly, and Copyscape. These tools compare your paper with millions of other documents on the web and databases to identify any matches. You can also use SciSpace paraphraser to rephrase the content and keep it unique.

You might also like

Plagiarism FAQs: 10 Most Commonly Asked Questions on Plagiarism in Research Answered

3 Common Mistakes in Research Publication, and How to Avoid Them

Academic Integrity Tutorial

- Examples of Plagiarism

- Le Moyne College Policy on Plagiarism

- Acceptable vs. Unacceptable

- What is a Citation?

- Why is Citing Important?

- When Do I Cite?

- How Do I Cite?

- Paraphrasing and Summarizing

- Practice Quiz

- Plagiarism and ChatGPT (Generative AI)

Real Life Examples of Plagiarism

Plagiarism has real and serious consequences, even when done unintentionally. Below are examples of people who were caught plagiarizing and the consequences they faced.

- Kaavya Viswanathan In 2006, Kaavya Viswanathan published a young adult book. It was later discovered that Viswanathan plagiarized heavily from books by Megan McCafferty, among others. Viswanathan claims that the plagiarism was unintentional. However, her book was recalled from stores and taken out of print and Viswanathan lost her contract for a second book.

- Jonah Lehrer Jonah Lehrer recently resigned as a writer for the New Yorker after he was caught self-plagiarizing on a number of occasions and fabricating quotes for a book.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin Doris Kearns Goodwin is a historian who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1995. It was later discovered that Goodwin plagiarized in her 1987 book, The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys. Once her plagiarism was discovered, Goodwin had to leave her position as a guest pundit on the PBS NewsHour program and resigned from the Pulitzer Board.

Here are some examples of Plagiarism:

- Turning in someone else's work as your own.

- Copying large pieces of text from a source without citing that source.

- Taking passages from multiple sources, piecing them together, and turning in the work as your own.

- Copying from a source but changing a few words and phrases to disguise plagiarism.

- Paraphrasing from a number of different sources without citing those sources.

- Turning in work that you did for another class without getting your professor's permission first.

- Buying an essay or paper and turning it in as your own work.

It is possible to cite sources but still plagiarize. Here are some examples:

- Mentioning an author or source within your paper without including a full citation in your bibliography.

- Citing a source with inaccurate information, making it impossible to find that source.

- Using a direct quote from a source, citing that source, but failing to put quotation marks around the copied text.

- Paraphrasing from multiple cited sources without including any original work.

Creative Commons License

- << Previous: What is Plagiarism?

- Next: Le Moyne College Policy on Plagiarism >>

- Last Updated: Sep 1, 2023 12:31 PM

- URL: https://resources.library.lemoyne.edu/guides/academicintegrity

- Utility Menu

fa3d988da6f218669ec27d6b6019a0cd

A publication of the harvard college writing program.

Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- The Honor Code

- What Constitutes Plagiarism?

In academic writing, it is considered plagiarism to draw any idea or any language from someone else without adequately crediting that source in your paper. It doesn't matter whether the source is a published author, another student, a website without clear authorship, a website that sells academic papers, or any other person: Taking credit for anyone else's work is stealing, and it is unacceptable in all academic situations, whether you do it intentionally or by accident.

The ease with which you can find information of all kinds online means that you need to be extra vigilant about keeping track of where you are getting information and ideas and about giving proper credit to the authors of the sources you use. If you cut and paste from an electronic document into your notes and forget to clearly label the document in your notes, or if you draw information from a series of websites without taking careful notes, you may end up taking credit for ideas that aren't yours, whether you mean to or not.

It's important to remember that every website is a document with an author, and therefore every website must be cited properly in your paper. For example, while it may seem obvious to you that an idea drawn from Professor Steven Pinker's book The Language Instinct should only appear in your paper if you include a clear citation, it might be less clear that information you glean about language acquisition from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy website warrants a similar citation. Even though the authorship of this encyclopedia entry is less obvious than it might be if it were a print article (you need to scroll down the page to see the author's name, and if you don't do so you might mistakenly think an author isn't listed), you are still responsible for citing this material correctly. Similarly, if you consult a website that has no clear authorship, you are still responsible for citing the website as a source for your paper. The kind of source you use, or the absence of an author linked to that source, does not change the fact that you always need to cite your sources (see Evaluating Web Sources ).

Verbatim Plagiarism

If you copy language word for word from another source and use that language in your paper, you are plagiarizing verbatim . Even if you write down your own ideas in your own words and place them around text that you've drawn directly from a source, you must give credit to the author of the source material, either by placing the source material in quotation marks and providing a clear citation, or by paraphrasing the source material and providing a clear citation.

The passage below comes from Ellora Derenoncourt’s article, “Can You Move to Opportunity? Evidence from the Great Migration.”

Here is the article citation in APA style:

Derenoncourt, E. (2022). Can you move to opportunity? Evidence from the Great Migration. The American Economic Review , 112(2), 369–408. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20200002

Source material

Why did urban Black populations in the North increase so dramatically between 1940 and 1970? After a period of reduced mobility during the Great Depression, Black out-migration from the South resumed at an accelerated pace after 1940. Wartime jobs in the defense industry and in naval shipyards led to substantial Black migration to California and other Pacific states for the first time since the Migration began. Migration continued apace to midwestern cities in the 1950s and1960s, as the booming automobile industry attracted millions more Black southerners to the North, particularly to cities like Detroit or Cleveland. Of the six million Black migrants who left the South during the Great Migration, four million of them migrated between 1940 and 1970 alone.

Plagiarized version

While this student has written her own sentence introducing the topic, she has copied the italicized sentences directly from the source material. She has left out two sentences from Derenoncourt’s paragraph, but has reproduced the rest verbatim:

But things changed mid-century. After a period of reduced mobility during the Great Depression, Black out-migration from the South resumed at an accelerated pace after 1940. Wartime jobs in the defense industry and in naval shipyards led to substantial Black migration to California and other Pacific states for the first time since the Migration began. Migration continued apace to midwestern cities in the 1950s and1960s, as the booming automobile industry attracted millions more Black southerners to the North, particularly to cities like Detroit or Cleveland.

Acceptable version #1: Paraphrase with citation

In this version the student has paraphrased Derenoncourt’s passage, making it clear that these ideas come from a source by introducing the section with a clear signal phrase ("as Derenoncourt explains…") and citing the publication date, as APA style requires.

But things changed mid-century. In fact, as Derenoncourt (2022) explains, the wartime increase in jobs in both defense and naval shipyards marked the first time during the Great Migration that Black southerners went to California and other west coast states. After the war, the increase in jobs in the car industry led to Black southerners choosing cities in the midwest, including Detroit and Cleveland.

Acceptable version #2 : Direct quotation with citation or direct quotation and paraphrase with citation

If you quote directly from an author and cite the quoted material, you are giving credit to the author. But you should keep in mind that quoting long passages of text is only the best option if the particular language used by the author is important to your paper. Social scientists and STEM scholars rarely quote in their writing, paraphrasing their sources instead. If you are writing in the humanities, you should make sure that you only quote directly when you think it is important for your readers to see the original language.

In the example below, the student quotes part of the passage and paraphrases the rest.

But things changed mid-century. In fact, as Derenoncourt (2022) explains, “after a period of reduced mobility during the Great Depression, Black out-migration from the South resumed at an accelerated pace after 1940” (p. 379). Derenoncourt notes that after the war, the increase in jobs in the car industry led to Black southerners choosing cities in the midwest, including Detroit and Cleveland.

Mosaic Plagiarism

If you copy bits and pieces from a source (or several sources), changing a few words here and there without either adequately paraphrasing or quoting directly, the result is mosaic plagiarism . Even if you don't intend to copy the source, you may end up with this type of plagiarism as a result of careless note-taking and confusion over where your source's ideas end and your own ideas begin. You may think that you've paraphrased sufficiently or quoted relevant passages, but if you haven't taken careful notes along the way, or if you've cut and pasted from your sources, you can lose track of the boundaries between your own ideas and those of your sources. It's not enough to have good intentions and to cite some of the material you use. You are responsible for making clear distinctions between your ideas and the ideas of the scholars who have informed your work. If you keep track of the ideas that come from your sources and have a clear understanding of how your own ideas differ from those ideas, and you follow the correct citation style, you will avoid mosaic plagiarism.

Indeed, of the more than 3500 hours of instruction during medical school, an average of less than 60 hours are devoted to all of bioethics, health law and health economics combined . Most of the instruction is during the preclinical courses, leaving very little instructional time when students are experiencing bioethical or legal challenges during their hands-on, clinical training. More than 60 percent of the instructors in bioethics, health law, and health economics have not published since 1990 on the topic they are teaching.

--Persad, G.C., Elder, L., Sedig,L., Flores, L., & Emanuel, E. (2008). The current state of medical school education in bioethics, health law, and health economics. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 36 , 89-94.

Students can absorb the educational messages in medical dramas when they view them for entertainment. In fact, even though they were not created specifically for education, these programs can be seen as an entertainment-education tool [43, 44]. In entertainment-education shows, viewers are exposed to educational content in entertainment contexts, using visual language that is easy to understand and triggers emotional engagement [45]. The enhanced emotional engagement and cognitive development [5] and moral imagination make students more sensitive to training [22].

--Cambra-Badii, I., Moyano, E., Ortega, I., Josep-E Baños, & Sentí, M. (2021). TV medical dramas: Health sciences students’ viewing habits and potential for teaching issues related to bioethics and professionalism. BMC Medical Education, 21 , 1-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02947-7

Paragraph #1.

All of the ideas in this paragraph after the first sentence are drawn directly from Persad. But because the student has placed the citation mid-paragraph, the final two sentences wrongly appear to be the student’s own idea:

In order to advocate for the use of medical television shows in the medical education system, it is also important to look at the current bioethical curriculum. In the more than 3500 hours of training that students undergo in medical school, only about 60 hours are focused on bioethics, health law, and health economics (Persad et al, 2008). It is also problematic that students receive this training before they actually have spent time treating patients in the clinical setting. Most of these hours are taught by instructors without current publications in the field.

Paragraph #2.

All of the italicized ideas in this paragraph are either paraphrased or taken verbatim from Cambra-Badii, et al., but the student does not cite the source at all. As a result, readers will assume that the student has come up with these ideas himself:

Students can absorb the educational messages in medical dramas when they view them for entertainment. It doesn’t matter if the shows were designed for medical students; they can still be a tool for education. In these hybrid entertainment-education shows, viewers are exposed to educational content that triggers an emotional reaction. By allowing for this emotional, cognitive, and moral engagement, the shows make students more sensitive to training . There may be further applications to this type of education: the role of entertainment as a way of encouraging students to consider ethical situations could be extended to other professions, including law or even education.

The student has come up with the final idea in the paragraph (that this type of ethical training could apply to other professions), but because nothing in the paragraph is cited, it reads as if it is part of a whole paragraph of his own ideas, rather than the point that he is building to after using the ideas from the article without crediting the authors.

Acceptable version

In the first paragraph, the student uses signal phrases in nearly every sentence to reference the authors (“According to Persad et al.,” “As the researchers argue,” “They also note”), which makes it clear throughout the paragraph that all of the paragraph’s information has been drawn from Persad et al. The student also uses a clear APA in-text citation to point the reader to the original article. In the second paragraph, the student paraphrases and cites the source’s ideas and creates a clear boundary behind those ideas and his own, which appear in the final paragraph.

In order to advocate for the use of medical television shows in the medical education system, it is also important to look at the current bioethical curriculum. According to Persad et al. (2008), only about one percent of teaching time throughout the four years of medical school is spent on ethics. As the researchers argue, this presents a problem because the students are being taught about ethical issues before they have a chance to experience those issues themselves. They also note that more than sixty percent of instructors teaching bioethics to medical students have no recent publications in the subject.

The research suggests that medical dramas may be a promising source for discussions of medical ethics. Cambra-Badii et al. (2021) explain that even when watched for entertainment, medical shows can help viewers engage emotionally with the characters and may prime them to be more receptive to training in medical ethics. There may be further applications to this type of education: the role of entertainment as a way of encouraging students to consider ethical situations could be extended to other professions, including law or even education.

Inadequate Paraphrase

When you paraphrase, your task is to distill the source's ideas in your own words. It's not enough to change a few words here and there and leave the rest; instead, you must completely restate the ideas in the passage in your own words. If your own language is too close to the original, then you are plagiarizing, even if you do provide a citation.

In order to make sure that you are using your own words, it's a good idea to put away the source material while you write your paraphrase of it. This way, you will force yourself to distill the point you think the author is making and articulate it in a new way. Once you have done this, you should look back at the original and make sure that you have represented the source’s ideas accurately and that you have not used the same words or sentence structure. If you do want to use some of the author's words for emphasis or clarity, you must put those words in quotation marks and provide a citation.

The passage below comes from Michael Sandel’s article, “The Case Against Perfection.” Here’s the article citation in MLA style:

Sandel, Michael. “The Case Against Perfection.” The Atlantic , April 2004, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2004/04/the-case-against-pe... .

Though there is much to be said for this argument, I do not think the main problem with enhancement and genetic engineering is that they undermine effort and erode human agency. The deeper danger is that they represent a kind of hyperagency—a Promethean aspiration to remake nature, including human nature, to serve our purposes and satisfy our desires. The problem is not the drift to mechanism but the drive to mastery. And what the drive to mastery misses and may even destroy is an appreciation of the gifted character of human powers and achievements.

The version below is an inadequate paraphrase because the student has only cut or replaced a few words: “I do not think the main problem” became “the main problem is not”; “deeper danger” became “bigger problem”; “aspiration” became “desire”; “the gifted character of human powers and achievements” became “the gifts that make our achievements possible.”

The main problem with enhancement and genetic engineering is not that they undermine effort and erode human agency. The bigger problem is that they represent a kind of hyperagency—a Promethean desire to remake nature, including human nature, to serve our purposes and satisfy our desires. The problem is not the drift to mechanism but the drive to mastery. And what the drive to mastery misses and may even destroy is an appreciation of the gifts that make our achievements possible (Sandel).

Acceptable version #1: Adequate paraphrase with citation

In this version, the student communicates Sandel’s ideas but does not borrow language from Sandel. Because the student uses Sandel’s name in the first sentence and has consulted an online version of the article without page numbers, there is no need for a parenthetical citation.

Michael Sandel disagrees with the argument that genetic engineering is a problem because it replaces the need for humans to work hard and make their own choices. Instead, he argues that we should be more concerned that the decision to use genetic enhancement is motivated by a desire to take control of nature and bend it to our will instead of appreciating its gifts.

Acceptable version #2: Direct quotation with citation

In this version, the student uses Sandel’s words in quotation marks and provides a clear MLA in-text citation. In cases where you are going to talk about the exact language that an author uses, it is acceptable to quote longer passages of text. If you are not going to discuss the exact language, you should paraphrase rather than quoting extensively.

The author argues that “the main problem with enhancement and genetic engineering is not that they undermine effort and erode human agency,” but, rather that “they represent a kind of hyperagency—a Promethean desire to remake nature, including human nature, to serve our purposes and satisfy our desires. The problem is not the drift to mechanism but the drive to mastery. And what the drive to mastery misses and may even destroy is an appreciation of the gifts that make our achievements possible” (Sandel).

Uncited Paraphrase

When you use your own language to describe someone else's idea, that idea still belongs to the author of the original material. Therefore, it's not enough to paraphrase the source material responsibly; you also need to cite the source, even if you have changed the wording significantly. As with quoting, when you paraphrase you are offering your reader a glimpse of someone else's work on your chosen topic, and you should also provide enough information for your reader to trace that work back to its original form. The rule of thumb here is simple: Whenever you use ideas that you did not think up yourself, you need to give credit to the source in which you found them, whether you quote directly from that material or provide a responsible paraphrase.

The passage below comes from C. Thi Nguyen’s article, “Echo Chambers and Epistemic Bubbles.”

Here’s the citation for the article, in APA style:

Nguyen, C. (2020). Echo chambers and epistemic bubbles. Episteme, 17 (2), 141-161. doi:10.1017/epi.2018.32

Epistemic bubbles can easily form accidentally. But the most plausible explanation for the particular features of echo chambers is something more malicious. Echo chambers are excellent tools to maintain, reinforce, and expand power through epistemic control. Thus, it is likely (though not necessary) that echo chambers are set up intentionally, or at least maintained, for this functionality (Nguyen, 2020).

The student who wrote the paraphrase below has drawn these ideas directly from Nguyen’s article but has not credited the author. Although she paraphrased adequately, she is still responsible for citing Nguyen as the source of this information.

Echo chambers and epistemic bubbles have different origins. While epistemic bubbles can be created organically, it’s more likely that echo chambers will be formed by those who wish to keep or even grow their control over the information that people hear and understand.

In this version, the student eliminates any possible ambiguity about the source of the ideas in the paragraph. By using a signal phrase to name the author whenever the source of the ideas could be unclear, the student clearly attributes these ideas to Nguyen.

According to Nguyen (2020), echo chambers and epistemic bubbles have different origins. Nguyen argues that while epistemic bubbles can be created organically, it’s more likely that echo chambers will be formed by those who wish to keep or even grow their control over the information that people hear and understand.

Uncited Quotation

When you put source material in quotation marks in your essay, you are telling your reader that you have drawn that material from somewhere else. But it's not enough to indicate that the material in quotation marks is not the product of your own thinking or experimentation: You must also credit the author of that material and provide a trail for your reader to follow back to the original document. This way, your reader will know who did the original work and will also be able to go back and consult that work if they are interested in learning more about the topic. Citations should always go directly after quotations.

The passage below comes from Deirdre Mask’s nonfiction book, The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power.

Here is the MLA citation for the book:

Mask, Deirdre. The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2021.

In New York, even addresses are for sale. The city allows a developer, for the bargain price of $11,000 (as of 2019), to apply to change the street address to something more attractive.

It’s not enough for the student to indicate that these words come from a source; the source must be cited:

After all, “in New York, even addresses are for sale. The city allows a developer, for the bargain price of $11,000 (as of 2019), to apply to change the street address to something more attractive.”

Here, the student has cited the source of the quotation using an MLA in-text citation:

After all, “in New York, even addresses are for sale. The city allows a developer, for the bargain price of $11,000 (as of 2019), to apply to change the street address to something more attractive” (Mask 229).

Using Material from Another Student's Work

In some courses you will be allowed or encouraged to form study groups, to work together in class generating ideas, or to collaborate on your thinking in other ways. Even in those cases, it's imperative that you understand whether all of your writing must be done independently, or whether group authorship is permitted. Most often, even in courses that allow some collaborative discussion, the writing or calculations that you do must be your own. This doesn't mean that you shouldn't collect feedback on your writing from a classmate or a writing tutor; rather, it means that the argument you make (and the ideas you rely on to make it) should either be your own or you should give credit to the source of those ideas.

So what does this mean for the ideas that emerge from class discussion or peer review exercises? Unlike the ideas that your professor offers in lecture (you should always cite these), ideas that come up in the course of class discussion or peer review are collaborative, and often not just the product of one individual's thinking. If, however, you see a clear moment in discussion when a particular student comes up with an idea, you should cite that student. In any case, when your work is informed by class discussions, it's courteous and collegial to include a discursive footnote in your paper that lets your readers know about that discussion. So, for example, if you were writing a paper about the narrator in Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried and you came up with your idea during a discussion in class, you might place a footnote in your paper that states the following: "I am indebted to the members of my Expos 20 section for sparking my thoughts about the role of the narrator as Greek Chorus in Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried ."

It is important to note that collaboration policies can vary by course, even within the same department, and you are responsible for familiarizing yourself with each course's expectation about collaboration. Collaboration policies are often stated in the syllabus, but if you are not sure whether it is appropriate to collaborate on work for any course, you should always consult your instructor.

- The Exception: Common Knowledge

- Other Scenarios to Avoid

- Why Does it Matter if You Plagiarize?

- How to Avoid Plagiarism

- Harvard University Plagiarism Policy

PDFs for This Section

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Online Library and Citation Tools

Plagiarism in research

- Scientific Contribution

- Published: 04 July 2014

- Volume 18 , pages 91–101, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Gert Helgesson 1 &

- Stefan Eriksson 2

11k Accesses

45 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Plagiarism is a major problem for research. There are, however, divergent views on how to define plagiarism and on what makes plagiarism reprehensible. In this paper we explicate the concept of “plagiarism” and discuss plagiarism normatively in relation to research. We suggest that plagiarism should be understood as “someone using someone else’s intellectual product (such as texts, ideas, or results), thereby implying that it is their own” and argue that this is an adequate and fruitful definition. We discuss a number of circumstances that make plagiarism more or less grave and the plagiariser more or less blameworthy. As a result of our normative analysis, we suggest that what makes plagiarism reprehensible as such is that it distorts scientific credit. In addition, intentional plagiarism involves dishonesty. There are, furthermore, a number of potentially negative consequences of plagiarism.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Plagiarism in Philosophy Research

Only if the result of intellectual work is a novel idea about a way to process a certain task (a method) will it be possible to plagiarise by repeating the processes and not disclosing where the idea of doing it like that originated. Which is to say that (the idea of) a method may be plagiarised by using it and not disclosing that someone else came up with it, thereby implying that you invented it yourself.

It is, of course, not the writing that constitutes plagiarism in the context of ghost-writing, but the claim to have written or co-authored a text completely written by others.

It should be noted that it does not have to be the authors’ fault that a paper is misleading about who deserves credit. Leonard Fleck has brought to our attention instances of journals, unbeknown to the authors, having mistakenly removed references or quotation marks in the text, causing the text to give the impression that some phrases quoted from others are the authors’ own.

Our claims here regarding practices are based on anecdotic evidence only. However, based on our teaching about 500 doctoral students per year, and having heard this frequently in class, we believe this to be fairly common, or at least far from unique.

Anekwe, T.D. 2010. Profits and plagiarism: The case of medical ghostwriting. Bioethics 24(6): 267–272.

Article Google Scholar

Baždarić, K., L. Bilić-Zulle, G. Brumini, and M. Petrovečki. 2012. Prevalence of plagiarism in recent submissions to the Croatian Medical Journal. Science and Engineering Ethics 18: 223–239.

Brogan, M. 1992. Recycling ideas. College and Research Libraries 52(5): 453–464.

Bruton, S.V. 2014. Self-plagiarism and textual recycling: Legitimate forms of research misconduct. Accountability in Research: Policies and Quality Assurance 21(3): 176–197.

Brülde, B., and P.-A. Tengland. 2003. Hälsa och sjukdom: en begreppslig utredning (Health and disease: A conceptual inquiry) . Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Google Scholar

Butler, D. 2010. Journals step up plagiarism policing. Nature 466(7303): 167.

Chandrasoma, R., C. Thompson, and A. Pennycook. 2004. Beyond plagiarism: Transgressive and nontransgressive intertextuality. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 3(3): 171–193.

Couzin-Frankel, J., and J. Grom. 2009. Plagiarism sleuths. Science 324(5930): 1004–1007.

DeVoss, D., and A.C. Rosati. 2002. “It wasn’t me, was it?” Plagiarism and the web. Computers and Composition 19: 191–203.

Khan, B.A. 2011. Plagiarism: An academic theft. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation 1(4): 255.

Pecorari, D. 2012. Textual plagiarism: How should it be regarded? Office of Research Integrity Newsletter 20(3): 3,10.

Rathod, S.D. 2012. Plagiarism: the human solution. Office of Research Integrity Newsletter 20(3): 1,7.

Roig, M. 2006. Avoiding plagiarism, self-plagiarism, and other questionable writing practices: A guide to ethical writing. Office of Research Integrity 2006. www.cse.msu.edu/~alexliu/plagiarism.pdf .

Samuelson, P. 1994. Self-plagiarism or fair use. Communications of the ACM 37(8): 21–25.

Sox, H. C. 2012. Plagiarism in the digital age. Office of Research Integrity Newsletter 20(3): 1,6.

Sun, Y.C. 2012. Does text readability matter? A study of paraphrasing and plagiarism in English as a foreign language writing context. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 21(2): 296–306.

Titus, S.L., J.A. Wells, and L.J. Rhoades. 2008. Repairing research integrity. Nature 453(7198): 980–982.

Vitse, C.L., and G.A. Poland. 2012. Plagiarism, self-plagiarism, scientific misconduct and VACCINE: Protecting the science and the public. Vaccine 30(50): 7131–7133. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.053 .

Wager, L. 2011. How should editors respond to plagiarism? COPE discussion paper. 26th April, 2011. http://publicationethics.org/files/Discussion%20document.pdf .

Yilmaz, I. 2007. Plagiarism? No, we’re just borrowing better English. Nature 449(7163): 658.

Zhang, Y. 2010. Chinese journal finds 31% of submissions plagiarized. Nature 467(7312): 153.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants at seminars at Stockholm Centre for Healthcare Ethics, Centre for Research Ethics and Bioethics at Uppsala University, and at the International Bioethics retreat in Paris 2013 for valuable suggestions and constructive criticism of earlier versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Stockholm Centre for Healthcare Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, 171 77, Stockholm, Sweden

Gert Helgesson

Centre for Research Ethics and Bioethics, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Stefan Eriksson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gert Helgesson .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Helgesson, G., Eriksson, S. Plagiarism in research. Med Health Care and Philos 18 , 91–101 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-014-9583-8

Download citation

Published : 04 July 2014

Issue Date : February 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-014-9583-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Fabrication

- Intellectual contribution

- Scientific misconduct

- Scientific credit

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Plagiarism in research

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Stockholm Centre for Healthcare Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, 171 77, Stockholm, Sweden, [email protected].

- PMID: 24993050

- DOI: 10.1007/s11019-014-9583-8

Plagiarism is a major problem for research. There are, however, divergent views on how to define plagiarism and on what makes plagiarism reprehensible. In this paper we explicate the concept of "plagiarism" and discuss plagiarism normatively in relation to research. We suggest that plagiarism should be understood as "someone using someone else's intellectual product (such as texts, ideas, or results), thereby implying that it is their own" and argue that this is an adequate and fruitful definition. We discuss a number of circumstances that make plagiarism more or less grave and the plagiariser more or less blameworthy. As a result of our normative analysis, we suggest that what makes plagiarism reprehensible as such is that it distorts scientific credit. In addition, intentional plagiarism involves dishonesty. There are, furthermore, a number of potentially negative consequences of plagiarism.

- Ethical Analysis

- Ethics, Research*

- Plagiarism*

How to Avoid Plagiarism in Research Papers (Part 1)

Writing a research paper poses challenges in gathering literature and providing evidence for making your paper stronger. Drawing upon previously established ideas and values and adding pertinent information in your paper are necessary steps, but these need to be done with caution without falling into the trap of plagiarism . In order to understand how to avoid plagiarism , it is important to know the different types of plagiarism that exist.

What is Plagiarism in Research?

Plagiarism is the unethical practice of using words or ideas (either planned or accidental) of another author/researcher or your own previous works without proper acknowledgment. Considered as a serious academic and intellectual offense, plagiarism can result in highly negative consequences such as paper retractions and loss of author credibility and reputation. It is currently a grave problem in academic publishing and a major reason for paper retractions .

It is thus imperative for researchers to increase their understanding about plagiarism. In some cultures, academic traditions and nuances may not insist on authentication by citing the source of words or ideas. However, this form of validation is a prerequisite in the global academic code of conduct. Non-native English speakers face a higher challenge of communicating their technical content in English as well as complying with ethical rules. The digital age too affects plagiarism. Researchers have easy access to material and data on the internet which makes it easy to copy and paste information.

Related: Conducting literature survey and wish to learn more about scientific misconduct? Check out this resourceful infographic today!

How Can You Avoid Plagiarism in a Research Paper?

Guard yourself against plagiarism, however accidental it may be. Here are some guidelines to avoid plagiarism.

1. Paraphrase your content

- Do not copy–paste the text verbatim from the reference paper. Instead, restate the idea in your own words.

- Understand the idea(s) of the reference source well in order to paraphrase correctly.

- Examples on good paraphrasing can be found here ( https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/QPA_paraphrase.html )

2. Use Quotations

Use quotes to indicate that the text has been taken from another paper. The quotes should be exactly the way they appear in the paper you take them from.

3. Cite your Sources – Identify what does and does not need to be cited

- The best way to avoid the misconduct of plagiarism is by self-checking your documents using plagiarism checker tools.

- Any words or ideas that are not your own but taken from another paper need to be cited .

- Cite Your Own Material—If you are using content from your previous paper, you must cite yourself. Using material you have published before without citation is called self-plagiarism .

- The scientific evidence you gathered after performing your tests should not be cited.

- Facts or common knowledge need not be cited. If unsure, include a reference.

4. Maintain records of the sources you refer to

- Maintain records of the sources you refer to. Use citation software like EndNote or Reference Manager to manage the citations used for the paper

- Use multiple references for the background information/literature survey. For example, rather than referencing a review, the individual papers should be referred to and cited.

5. Use plagiarism checkers

You can use various plagiarism detection tools such as iThenticate or HelioBLAST (formerly eTBLAST) to see how much of your paper is plagiarised .

Tip: While it is perfectly fine to survey previously published work, it is not alright to paraphrase the same with extensive similarity. Most of the plagiarism occurs in the literature review section of any document (manuscript, thesis, etc.). Therefore, if you read the original work carefully, try to understand the context, take good notes, and then express it to your target audience in your own language (without forgetting to cite the original source), then you will never be accused with plagiarism (at least for the literature review section).

Caution: The above statement is valid only for the literature review section of your document. You should NEVER EVER use someone else’s original results and pass them off as yours!

What strategies do you adopt to maintain content originality? What advice would you share with your peers? Please feel free to comment in the section below.

If you would like to know more about patchwriting, quoting, paraphrasing and more, read the next article in this series!

Nice!! This article gives ideas to avoid plagiarism in a research paper and it is important in a research paper.

the article is very useful to me as a starter in research…thanks a lot!

it’s educative. what a wonderful article to me, it serves as a road map to avoid plagiarism in paper writing. thanks, keep your good works on.

I think this is very important topic before I can proceed with my M.A

it is easy to follow and understand

Nice!! These articles provide clear instructions on how to avoid plagiarism in research papers along with helpful tips.

Amazing and knowledgeable notes on plagiarism

Very helpful and educative, I have easily understood everything. Thank you so much.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Language & Grammar

- Reporting Research

Best Plagiarism Checker Tool for Researchers — Top 4 to choose from!

While common writing issues like language enhancement, punctuation errors, grammatical errors, etc. can be dealt…

How to Use Synonyms Effectively in a Sentence? — A way to avoid plagiarism!

Do you remember those school days when memorizing synonyms and antonyms played a major role…

- Manuscripts & Grants

Reliable and Affordable Plagiarism Detector for Students in 2022

Did you know? Our senior has received a rejection from a reputed journal! The journal…

- Publishing Research

- Submitting Manuscripts

3 Effective Tips to Make the Most Out of Your iThenticate Similarity Report

This guest post is drafted by an expert from iThenticate, a plagiarism checker trusted by the world’s…

How Can Researchers Avoid Plagiarism While Ensuring the Originality of Their Manuscript?

How Can Researchers Avoid Plagiarism While Ensuring the Originality of Their…

Is Your Reputation Safe? How to Ensure You’re Passing a Spotless Manuscript to Your…

Should the Academic Community Trust Plagiarism Detectors?

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Training videos | Faqs

Plagiarism in Research – Definition, Types, Examples and Consequences

Plagiarism | Plagiarism Checkers | Paraphrasing Techniques | Scholarly Paraphraser

In this blog, we will discuss plagiarism in detail, its consequences, and techniques to avoid it. We will also look at different types of plagiarism using practical examples.

1. What is considered plagiarism?

Plagiarism occurs when you use someone else’s work without acknowledging the original author. Plagiarism is regarded as stealing and often leads to serious consequences and harsh punishment. This is usually found in several areas, especially academic writing, where concepts and statements are derived from an origin without proper citing.

2. What are the consequences of plagiarism?

Damage to student image: Schools usually include the ethics of their students in their academic records. Students who are found guilty of plagiarism are usually suspended or expelled from the schools, thereby causing the student not to be able to get into another school.

Damage to professional image: A lot of people, including journalists, freelancers, and writing professionals, are usually impacted by the effect of plagiarism all their life. This has led many professionals to lose their jobs or get retrenched at their workplaces. Furthermore, this dent tends to go with them throughout their career, making it difficult to secure another job.

3. Why do students plagiarize?

Following are some reasons why students plagiarize or cheat:

4. What are the different types of plagiarism?

5. what are some common examples of plagiarism, 6. a practical example of plagiarism in a paper.

Let’s look at some examples of Plagiarism.

More than 70% of papers rejected by scientific journals are written by non-native English speakers. Source text: Statement from paper by Elan et al. (2017)

This piece of text shown above is from a paper written by ‘Smith et al’. Now, the authors have used this statement in their paper as shown below. They have done the right thing by citing the source at the end of the statement. The mistake here is that since they have used the exact text from the paper, they must enclose them in quotes. This will be considered plagiarism.

More than 70% of papers rejected by scientific journals are written by non-native English speakers. (Elan et al. , 2017) Incorrect: Unaltered text not it quotes and hence it will be considered plagiarism

So the correct way to do this will be to put the text in quotation marks and then reference the paper.

As Smith et al. (2017) state: “More than 70% of papers rejected by scientific journals are written by non-native English speakers”. Correct: Proper way to quote the paper

It is generally not advisable to use a lot of unaltered text from other papers and put them in quotes in your paper. You should only use the exact text from someone’s work if you think it is important to be precise. This can include things like a philosopher’s statement or definition of something. Most referees and supervisors expect you to understand the work and then write them in your own words. In the example below the authors have paraphrased the text and then cited the paper, this is how it should be done.

Manuscripts authored by non-native English speakers are rejected by scientific publications 70% of the time. (Smith et al., 2017) Correct: Text paraphrased and source cited (the recommended way)

7. What is self-plagiarism?

Self plagiarism occurs when you use a piece of text from your own published work in a new paper that you are writing. You might ask, what is the problem? It is my work and why can’t I use it again in a different paper? The problem is that once you publish your work, the copyright for the text belongs to the publisher, you cannot use the unaltered text from your old paper in your new paper. You have to paraphrase your text if you want to use the same content in your new paper.

Self-plagiarism even applies to figures, if you want to reuse a figure from your old paper in your new paper exactly as it is, you have to get permission from the publisher of your old paper. If the publisher does not give you permission, then you should modify it.

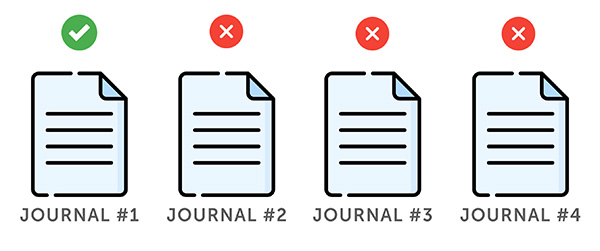

8. Simulateneous submission to multiple journals

Another serious type of self-plagiarism is submitting exactly the same paper to multiple journals. You cannot do this. When you submit your paper to a journal you will be signing an agreement that clearly states that “the work in question has not been published before and is not under submission at any other journal” . If you submit the same manuscript to multiple journals, then, it is a violation of the ethical standards of publishing. You must submit your paper to a journal first and wait for the outcome. If the paper gets rejected, then submit your paper to another journal. Keep repeating the process until you get your work published.

9. How do you avoid plagiarism?

There are numerous ways to avoid plagiarism in your academic and professional work. Below are the top hints to avoid plagiarism:

10. Frequently asked questions about plagiarism

Plagiarism is when you make use of someone else’s work without acknowledging that they own it.

There are numerous methods and citation formats you can use when referencing sources.

Several academic disciplines and publishers have developed a number of standards for citing sources, including IEEE, Havard, MLA, APA, and Chicago.

If you are unclear about the acceptable citation style for your research paper, consult your instructor or read the journal instructions. The proper format to employ while composing your Bibliography or List of Works Cited is provided by citation style guides.

The fundamental bibliographic data needed is the same regardless of your chosen citation style. Don’t forget to gather these data as your research advances.

- For books, include the following information: author, title, publisher, and year of publication.

- For journals, author, article title, journal title, volume, issue, date, page numbers, and doi or permalink are required.

- Author, page title, web address or URL, and access date are required for web page resources.

Finally, use a good referencing tool to manage your references and generate bibliography.

Here are some techniques for paraphrasing the text to avoid plagiarism.

- You read the text out loud and understand the meaning

- You write down your paraphrase

- Confirm that your writeup aligns with the original text.

You can also use academic paraphrasing tools to paraphrase your text and plagiarism detection tools to identify plagiarism in your text.

Yes! Self-plagiarism occurs when you make use of your previous write-up in a new one, but this can be avoided if the previous write-up is properly cited and paraphrased.

Similar Posts

Self-Plagiarism – Similarity Checker Tool to Avoid Academic Misconduct

In this blog, we explain the differences between self-plagiarism and plain plagiarism, and demonstrate the benefits of Ref-n-write’s similarity checker tool.

Plagiarism Checker and Plagiarism Detector Tools – A Review of Free and Paid Tools

In this blog, we review the most popular plagiarism checking tools available in the market from the perspective of cost and ease of use.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- 4 Share Facebook

- 7 Share Twitter

- 8 Share LinkedIn

- 5 Share Email

Free plagiarism checker by EasyBib

Check for plagiarism, grammar errors, and more.

- Expert Check

Check for accidental plagiarism

Avoid unintentional plagiarism. Check your work against billions of sources to ensure complete originality.

Find and fix grammar errors

Turn in your best work. Our smart proofreader catches even the smallest writing mistakes so you don't have to.

Get expert writing help

Improve the quality of your paper. Receive feedback on your main idea, writing mechanics, structure, conclusion, and more.

What students are saying about us

"Caught comma errors that I actually struggle with even after proofreading myself."

- Natasha J.

"I find the suggestions to be extremely helpful especially as they can instantly take you to that section in your paper for you to fix any and all issues related to the grammar or spelling error(s)."

- Catherine R.

Check for unintentional plagiarism

Easily check your paper for missing citations and accidental plagiarism with the EasyBib plagiarism checker. The EasyBib plagiarism checker:

- Scans your paper against billions of sources.

- Identifies text that may be flagged for plagiarism.

- Provides you with a plagiarism score.

You can submit your paper at any hour of the day and quickly receive a plagiarism report.

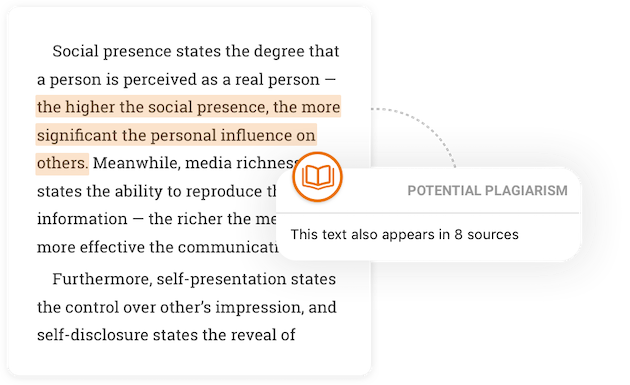

What is the EasyBib plagiarism checker?

Most basic plagiarism checkers review your work and calculate a percentage, meaning how much of your writing is indicative of original work. But, the EasyBib plagiarism checker goes way beyond a simple percentage. Any text that could be categorized as potential plagiarism is highlighted, allowing you time to review each warning and determine how to adjust it or how to cite it correctly.

You’ll even see the sources against which your writing is compared and the actual word for word breakdown. If you determine that a warning is unnecessary, you can waive the plagiarism check suggestion.

Plagiarism is unethical because it doesn’t credit those who created the original work; it violates intellectual property and serves to benefit the perpetrator. It is a severe enough academic offense, that many faculty members use their own plagiarism checking tool for their students’ work. With the EasyBib Plagiarism checker, you can stay one step ahead of your professors and catch citation mistakes and accidental plagiarism before you submit your work for grading.

Why use a plagiarism checker?