- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

University News | 10.15.2019

Campus Survey: Sexual Assault, Harassment Remain Serious Problems

Results from the second campus survey of sexual misconduct show that sexual assault and harassment remain serious problems at institutions of higher education nationwide..

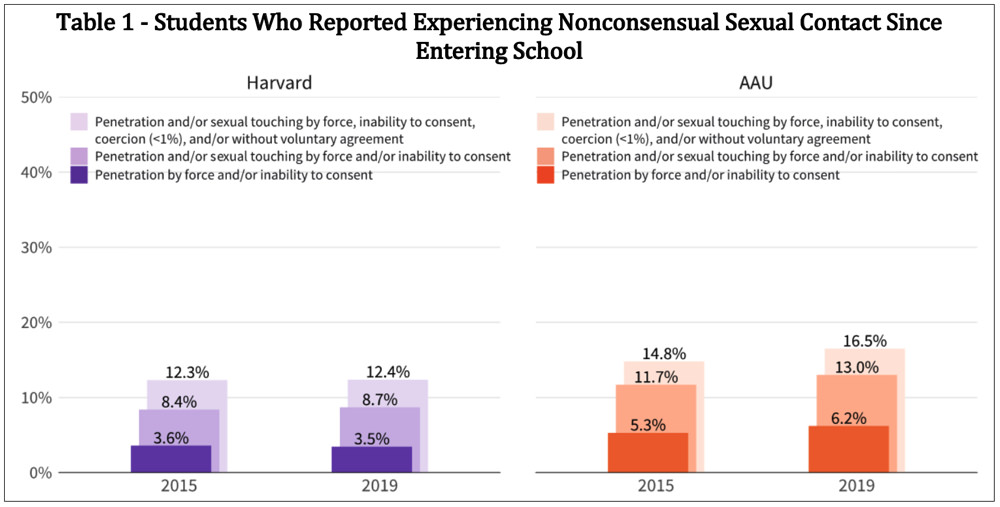

On October 15, Harvard released the results of a survey intended to estimate the prevalence of sexual assault and other sexual misconduct among its undergraduate, graduate, and professional-school students. The survey, conducted during the spring of 2019, reached about 23,000 students, of whom 36.1 percent (about 8,300) responded. The data—echoing those from the 32 other private and public Association of American Universities (AAU) institutions that participated in this year’s survey— show that sexual assault and harassment are a serious problem. At Harvard, the prevalence of sexual assault (12.4 percent) was essentially unchanged since a similar survey was conducted in 2015 .

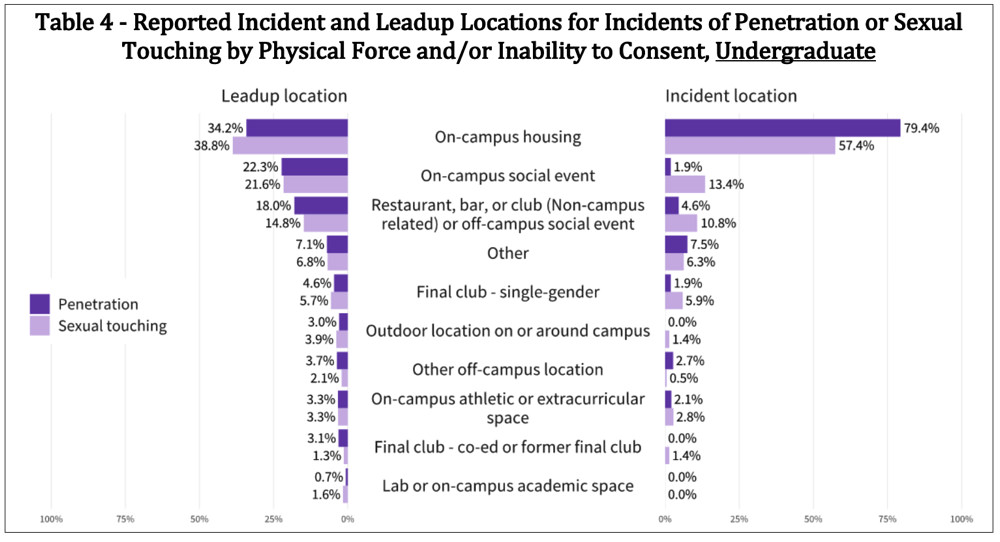

Among undergraduates, the vast majority of nonconsensual sexual contact is student to student (82.5 percent), takes place in on-campus housing (more than two-thirds overall, and 79.4 percent in incidents of penetration or sexual touching by physical force and/or inability to consent), and involves alcohol (75.6 percent). Rates among graduate students, who are less likely to live in on-campus housing, less likely to go out drinking with friends, and less likely to be single, are lower, but on-campus housing remains the modal location for sexual assault. Although the rates at which students disclose these incidents have been climbing rapidly (the rate of disclosure increased 56 percent in fiscal year 2018) the majority of students do not disclose incidents to the University, the survey showed—and the prevalence of nonconsensual sexual contact has been unaffected by rising disclosure rates. Among all AAU institutions that participated in both the 2015 and 2019 surveys, the prevalence of nonconsensual sexual contact has risen slightly overall.

The most significant change to the 2019 survey is that it introduces “incident level reporting” for cases of both sexual assault and sexual harassment: students who indicate that they have been victims of sexual assault, for example, are asked a series of additional questions, such as the nature of their relationship to the perpetrator, where they were during the time leading up to the incident, where they were when the incident occurred, the perpetrator’s relationship to the University, and whether they contacted any of the resources or support services available to them on campus (see table 4, above). With incident level reporting, the assertion made based on 2015 data that among undergraduates “about 15 percent of incidents took place in single-sex organizations that were not a fraternity or sorority”—final clubs—appears incorrect. Among Harvard College students, “on-campus social events” and “restaurants, bars and clubs” figure more prominently in both “leadup location” and “incident location,” behind on-campus housing.

Questions about sexual harassment, as opposed to assault, were changed in the 2019 survey, meaning that the data can’t be reliably compared to the data from the 2015. Harassment, however, remains a serious concern: 39.3 percent of respondents reported experiencing harassing behavior, and 17.7 percent reported that the harassment interfered with their academic or professional performance, limited their ability to participate in an academic program, or created an intimidating, hostile, or offensive social, academic, or work environment. As with allegations of assault, most harassment was perpetrated by other students.

Since the 2015 survey, Harvard has expanded its support services and educational outreach to its student communities. In 2016, the University hired Nicole Merhill as its Title IX officer, and specified that she spend 50 percent of her time designing prevention initiatives. Since then, 65,000 students, staff, and faculty members have participated in online training, and in-person training has been increasing rapidly, too (by 41 percent in the past year). Merhill has created two Title IX liaison groups, one for students and another for staff. And she has made a number of changes designed to increase the likelihood that students will disclose incidents of assault and harassment to University administrators, including expansion of its system of more than 50 Title IX coordinators. “Bystander” training, another initiative, seeks to increase the likelihood that students, faculty and staff will intervene if they see behavior that presages sexual assault. Most recently, Merhill established an online anonymous disclosure tool in response to student concerns that reporting an incident might lead to their losing control over the ensuing process. The new tool is designed to allow University affiliates to communicate with the University Title IX Office without revealing their identity until they are ready.

Nevertheless, most students who reported an incident of sexual assault did NOT seek out aid, whether from University Health Services, the office of BGLTQ student life, the mental-health counselors, the Title IX office, the Office for Dispute Resolution, the office of sexual assault prevention and response, Harvard chaplains, or student peer supports. The principal reason students gave for not reporting an incident was that it wasn’t serious enough. However, a majority reported that they did speak with friends and family about the event.

In written recommendations to President Lawrence S. Bacow, deputy provost Peggy Newell and Cahners-Rabb professor of business administration Kathleen L. McGinn, co-chairs of the Harvard 2019 AAU Student Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct, wrote that:

Knowledge of support services and belief in the fairness of University processes for investigating reports of nonconsensual sexual contact and sexual harassment have both risen since 2015, but less than half of our students feel very or extremely knowledgeable about support services on campus and less than half of our students believe that the outcome of University processes related to reports of sexual misconduct will be fair. In spite of heightened attention to nonconsensual sexual contact and sexual harassment in society, in the media, and at Harvard, only a minority of students experiencing nonconsensual sexual contact or sexual harassment access any of the resources available on campus…. The steady and high rate of nonconsensual sexual contact experienced by Harvard students calls for a cultural change across our community.

President Bacow, in a letter to the Harvard community , wrote that:

the data support the reality that sexual assault and sexual harassment remain a serious problem at Harvard, and at institutions of higher education across the country….We must do more to prevent sexual and gender-based harassment and assault, and to encourage people to come forward to share their experiences and their concerns with us. And we must not rest until every member of our community has confidence in their institution’s ability to support them. This responsibility starts with the University leadership, but we can only truly effect meaningful change with your ideas and your commitment….

“Initiatives like bystander training,” he continued, “send the message to students that sexual misconduct is not acceptable." He has therefore “asked the Title IX Office to oversee the expansion of more of these bystander intervention initiatives across the University.” But he noted that “A change in culture can only come about through shared efforts by the administration, faculty, staff, and students,” and he invited all members of the Harvard community to a conversation about the issues raised by the survey at the Science Center on October 17.

“One of my highest priorities,” he concluded, “is to create a community in which all of us can do our best work. To achieve this, we must seek to enhance our policies and procedures, and build out new resources, that are marked by our humanity, and which remind us to care for one another. But most importantly, we must recognize that we all have a role to play in ensuring that each of us who calls Harvard home feels welcome, and safe.”

You might also like

Slow and Steady

A Harvard Law School graduate completes marathons in all 50 states.

Claudine Gay in First Post-Presidency Appearance

At Morning Prayers, speaks of resilience and the unknown

The Dark History Behind Chocolate

A Harvard course on the politics and culture of food

Most popular

Harvard College Reinstitutes Mandatory Testing

Applicants for the class of 2029 must submit scores.

More to explore

Winthrop Bell

Brief life of a philosopher and spy: 1884-1965

Capturing the American South

Photographs at the Addison Gallery of American Art

The Happy Warrior Redux

Hubert Humphrey’s liberalism reconsidered

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.4 Violence against Women: Rape and Sexual Assault

Learning objectives.

- Describe the extent of rape and sexual assault.

- Explain why rape and sexual assault occur.

Susan Griffin (1971, p. 26) began a classic essay on rape in 1971 with this startling statement: “I have never been free of the fear of rape. From a very early age I, like most women, have thought of rape as a part of my natural environment—something to be feared and prayed against like fire or lightning. I never asked why men raped; I simply thought it one of the many mysteries of human nature.”

When we consider interpersonal violence of all kinds—homicide, assault, robbery, and rape and sexual assault—men are more likely than women to be victims of violence. While true, this fact obscures another fact: Women are far more likely than men to be raped and sexually assaulted. They are also much more likely to be portrayed as victims of pornographic violence on the Internet and in videos, magazines, and other outlets. Finally, women are more likely than men to be victims of domestic violence , or violence between spouses and others with intimate relationships. The gendered nature of these acts against women distinguishes them from the violence men suffer. Violence is directed against men not because they are men per se, but because of anger, jealousy, and the sociological reasons discussed in Chapter 8 “Crime and Criminal Justice” ’s treatment of deviance and crime. But rape and sexual assault, domestic violence, and pornographic violence are directed against women precisely because they are women. These acts are thus an extreme manifestation of the gender inequality women face in other areas of life. We discuss rape and sexual assault here but will leave domestic violence for Chapter 10 “The Changing Family” and pornography for Chapter 9 “Sexual Behavior” .

The Extent and Context of Rape and Sexual Assault

Our knowledge about the extent and context of rape and reasons for it comes from three sources: the FBI Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), both discussed in Chapter 8 “Crime and Criminal Justice” , and surveys of and interviews with women and men conducted by academic researchers. From these sources we have a fairly good if not perfect idea of how much rape occurs, the context in which it occurs, and the reasons for it. What do we know?

Up to one-third of US women experience a rape or sexual assault, including attempts, at least once in their lives.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

According to the UCR, which are compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from police reports, 88,767 reported rapes (including attempts, and defined as forced sexual intercourse) occurred in the United States in 2010 (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2011). Because women often do not tell police they were raped, the NCVS, which involves survey interviews of thousands of people nationwide, probably yields a better estimate of rape; the NCVS also measures sexual assaults in addition to rape, while the UCR measures only rape. According to the NCVS, 188,380 rapes and sexual assaults occurred in 2010 (Truman, 2011). Other research indicates that up to one-third of US women will experience a rape or sexual assault, including attempts, at least once in their lives (Barkan, 2012). A study of a random sample of 420 Toronto women involving intensive interviews yielded an even higher figure: Two-thirds said they had experienced at least one rape or sexual assault, including attempts. The researchers, Melanie Randall and Lori Haskell (1995, p. 22), concluded that “it is more common than not for a woman to have an experience of sexual assault during their lifetime.”

Studies of college students also find a high amount of rape and sexual assault. About 20–30 percent of women students in anonymous surveys report being raped or sexually assaulted (including attempts), usually by a male student they knew beforehand (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2000; Gross, Winslett, Roberts, & Gohm, 2006). Thus at a campus of 10,000 students of whom 5,000 are women, about 1,000–1,500 women will be raped or sexually assaulted over a period of four years, or about 10 per week in a four-year academic calendar. The Note 4.33 “People Making a Difference” box describes what one group of college students did to help reduce rape and sexual assault at their campus.

People Making a Difference

College Students Protest against Sexual Violence

Dickinson College is a small liberal-arts campus in the small town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. But in the fight against sexual violence, it loomed huge in March 2011, when up to 150 students conducted a nonviolent occupation of the college’s administrative building for three days to protest rape and sexual assault on their campus. While they read, ate, and slept inside the building, more than 250 other students held rallies outside, with the total number of protesters easily exceeding one-tenth of Dickinson’s student enrollment. The protesters held signs that said “Stop the silence, our safety is more important than your reputation” and “I value my body, you should value my rights.” One student told a reporter, “This is a pervasive problem. Almost every student will tell you they know somebody who’s experienced sexual violence or have experienced it themselves.”

Feeling that college officials had not done enough to help protect Dickinson’s women students, the students occupying the administrative building called on the college to set up an improved emergency system for reporting sexual assaults, to revamp its judicial system’s treatment of sexual assault cases, to create a sexual violence prevention program, and to develop a new sexual misconduct policy.

Rather than having police or security guards take the students from the administrative building and even arrest them, Dickinson officials negotiated with the students and finally agreed to their demands. Upon hearing this good news, the occupying students left the building on a Saturday morning, suffering from a lack of sleep and showers but cheered that they had won their demands. A college public relations official applauded the protesters, saying they “have indelibly left their mark on the college. We’re all very proud of them.” On this small campus in a small town in Pennsylvania, a few hundred college students had made a difference.

Sources: Jerving, 2011; Pitz, 2011

The public image of rape is of the proverbial stranger attacking a woman in an alleyway. While such rapes do occur, most rapes actually happen between people who know each other. A wide body of research finds that 60–80 percent of all rapes and sexual assaults are committed by someone the woman knows, including husbands, ex-husbands, boyfriends, and ex-boyfriends, and only 20–35 percent by strangers (Barkan, 2012). A woman is thus two to four times more likely to be raped by someone she knows than by a stranger.

In 2011, sexual assaults of hotel housekeepers made major headlines after the head of the International Monetary Fund was arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting a hotel housekeeper in New York City; the charges were later dropped because the prosecution worried about the housekeeper’s credibility despite forensic evidence supporting her claim. Still, in the wake of the arrest, news stories reported that hotel housekeepers sometimes encounter male guests who commit sexual assault, make explicit comments, or expose themselves. A hotel security expert said in one news story, “These problems happen with some regularity. They’re not rare, but they’re not common either.” A housekeeper recalled in the same story an incident when she was vacuuming when a male guest appeared: “[He] reached to try to kiss me behind my ear. I dropped my vacuum, and then he grabbed my body at the waist, and he was holding me close. It was very scary.” She ran out of the room when the guest let her leave but did not call the police. A hotel workers union official said housekeepers often refused to report sexual assault and other incidents to the police because they were afraid they would not be believed or that they would get fired if they did so (Greenhouse, 2011, p. B1).

Explaining Rape and Sexual Assault

Sociological explanations of rape fall into cultural and structural categories similar to those presented earlier for sexual harassment. Various “rape myths” in our culture support the absurd notion that women somehow enjoy being raped, want to be raped, or are “asking for it” (Franiuk, Seefelt, & Vandello, 2008). One of the most famous scenes in movie history occurs in the classic film Gone with the Wind , when Rhett Butler carries a struggling Scarlett O’Hara up the stairs. She is struggling because she does not want to have sex with him. The next scene shows Scarlett waking up the next morning with a satisfied, loving look on her face. The not-so-subtle message is that she enjoyed being raped (or, to be more charitable to the film, was just playing hard to get).

A related cultural belief is that women somehow ask or deserve to be raped by the way they dress or behave. If she dresses attractively or walks into a bar by herself, she wants to have sex, and if a rape occurs, well, then, what did she expect? In the award-winning film The Accused , based on a true story, actress Jodie Foster plays a woman who was raped by several men on top of a pool table in a bar. The film recounts how members of the public questioned why she was in the bar by herself if she did not want to have sex and blamed her for being raped.

A third cultural belief is that a man who is sexually active with a lot of women is a stud and thus someone admired by his male peers. Although this belief is less common in this day of AIDS and other STDs, it is still with us. A man with multiple sex partners continues to be the source of envy among many of his peers. At a minimum, men are still the ones who have to “make the first move” and then continue making more moves. There is a thin line between being sexually assertive and sexually aggressive (Kassing, Beesley, & Frey, 2005).

These three cultural beliefs—that women enjoy being forced to have sex, that they ask or deserve to be raped, and that men should be sexually assertive or even aggressive—combine to produce a cultural recipe for rape. Although most men do not rape, the cultural beliefs and myths just described help account for the rapes that do occur. Recognizing this, the contemporary women’s movement began attacking these myths back in the 1970s, and the public is much more conscious of the true nature of rape than a generation ago. That said, much of the public still accepts these cultural beliefs and myths, and prosecutors continue to find it difficult to win jury convictions in rape trials unless the woman who was raped had suffered visible injuries, had not known the man who raped her, and/or was not dressed attractively (Levine, 2006).

Structural explanations for rape emphasize the power differences between women and men similar to those outlined earlier for sexual harassment. In societies that are male dominated, rape and other violence against women is a likely outcome, as they allow men to demonstrate and maintain their power over women. Supporting this view, studies of preindustrial societies and of the fifty states of the United States find that rape is more common in societies where women have less economic and political power (Baron & Straus, 1989; Sanday, 1981). Poverty is also a predictor of rape; although rape in the United States transcends social class boundaries, it does seem more common among poorer segments of the population than among wealthier segments, as is true for other types of violence (Truman & Rand, 2010). Scholars think the higher rape rates among the poor stem from poor men trying to prove their “masculinity” by taking out their economic frustration on women (Martin, Vieraitis, & Britto, 2006).

Key Takeaways

- Up to one-third of US women experience a rape or sexual assault, including attempts, in their lifetime.

- Rape and sexual assault result from a combination of structural and cultural factors. In states and nations where women are more unequal, rape rates tend to be higher.

For Your Review

- What evidence and reasoning indicate that rape and sexual assault are not just the result of psychological problems affecting the men who engage in these crimes?

- Write a brief essay in which you critically evaluate the cultural beliefs that contribute to rape and sexual assault.

Barkan, S. E. (2012). Criminology: A sociological understanding (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Baron, L., & Straus, M. A. (1989). Four theories of rape in American society: A state-level analysis . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2011). Crime in the United States, 2010 . Washington, DC: Author.

Fisher, B. S., Cullen, F. T., & Turner, M. G. (2000). The sexual victimization of college women . Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Franiuk, R., Seefelt, J., & Vandello, J. (2008). Prevalence of rape myths in headlines and their effects on attitudes toward rape. Sex Roles, 58 (11/12), 790–801.

Greenhouse, S. (2011, May 21). Sexual affronts a known hotel hazard. New York Times , p. B1.

Griffin, S. (1971, September). Rape: The all-American crime. Ramparts, 10 , 26–35.

Gross, A. M., Winslett, A., Roberts, M., & Gohm, C. L. (2006). An examination of sexual violence against college women. Violence Against Women, 12 , 288–300.

Jerving, S. (2011, March 4). Pennsylvania students protest against sexual violence and administrators respond. The Nation . Retrieved from http://www.thenation.com/blog/159037/pennsylvania-students-protests-against-sexual-violence-and-administrators-respond .

Kassing, L. R., Beesley, D., & Frey, L. L. (2005). Gender role conflict, homophobia, age, and education as predictors of male rape myth acceptance. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 27 (4), 311–328.

Levine, K. L. (2006). The intimacy discount: Prosecutorial discretion, privacy, and equality in the statuory rape caseload. Emory Law Journal, 55 (4), 691–749.

Martin, K., Vieraitis, L. M., & Britto, S. (2006). Gender equality and women’s absolute status: A test of the feminist models of rape. Violence Against Women, 12 , 321–339.

Pitz, M. (2011, March 6). Dickinson College to change sexual assault policy after sit-in. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette . Retrieved from http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/11065/1130102-1130454.stm .

Randall, M., & Haskell, L. (1995). Sexual violence in women’s lives: Findings from the women’s safety project, a community-based survey. Violence Against Women, 1 , 6–31.

Sanday, P. R. (1981). The Socio-Cultural Context of Rape: A Cross-Cultural Study. Journal of Social Issues, 37 , 5–27.

Truman, J. L., & Rand, M. R. (2010). Criminal victimization, 2009 . Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Social Problems Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Sexual assault incidents among college undergraduates: Prevalence and factors associated with risk

Contributed equally to this work with: Claude A. Mellins, Kate Walsh, Aaron L. Sarvet, Melanie Wall, Leigh Reardon, Jennifer S. Hirsch

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Division of Gender, Sexuality and Health, Departments of Psychiatry and Sociomedical Sciences, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, Yeshiva University, New York, New York, United States of America, Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Biostatistics, Department of Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Division of Biostatistics, Department of Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York, United States of America, Department of Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ These authors also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliation Social Intervention Group, School of Social Work, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Youth, Family, and Community Studies, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina, United States of America

Roles Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Sociology, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Methodology

Roles Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

- Claude A. Mellins,

- Kate Walsh,

- Aaron L. Sarvet,

- Melanie Wall,

- Louisa Gilbert,

- John S. Santelli,

- Martie Thompson,

- Patrick A. Wilson,

- Shamus Khan,

- Published: November 8, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471

- Reader Comments

25 Jan 2018: The PLOS ONE Staff (2018) Correction: Sexual assault incidents among college undergraduates: Prevalence and factors associated with risk. PLOS ONE 13(1): e0192129. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192129 View correction

Sexual assault on college campuses is a public health issue. However varying research methodologies (e.g., different sexual assault definitions, measures, assessment timeframes) and low response rates hamper efforts to define the scope of the problem. To illuminate the complexity of campus sexual assault, we collected survey data from a large population-based random sample of undergraduate students from Columbia University and Barnard College in New York City, using evidence based methods to maximize response rates and sample representativeness, and behaviorally specific measures of sexual assault to accurately capture victimization rates. This paper focuses on student experiences of different types of sexual assault victimization, as well as sociodemographic, social, and risk environment correlates. Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and logistic regression were used to estimate prevalences and test associations. Since college entry, 22% of students reported experiencing at least one incident of sexual assault (defined as sexualized touching, attempted penetration [oral, anal, vaginal, other], or completed penetration). Women and gender nonconforming students reported the highest rates (28% and 38%, respectively), although men also reported sexual assault (12.5%). Across types of assault and gender groups, incapacitation due to alcohol and drug use and/or other factors was the perpetration method reported most frequently (> 50%); physical force (particularly for completed penetration in women) and verbal coercion were also commonly reported. Factors associated with increased risk for sexual assault included non-heterosexual identity, difficulty paying for basic necessities, fraternity/sorority membership, participation in more casual sexual encounters (“hook ups”) vs. exclusive/monogamous or no sexual relationships, binge drinking, and experiencing sexual assault before college. High rates of re-victimization during college were reported across gender groups. Our study is consistent with prevalence findings previously reported. Variation in types of assault and methods of perpetration experienced across gender groups highlight the need to develop prevention strategies tailored to specific risk groups.

Citation: Mellins CA, Walsh K, Sarvet AL, Wall M, Gilbert L, Santelli JS, et al. (2017) Sexual assault incidents among college undergraduates: Prevalence and factors associated with risk. PLoS ONE 12(11): e0186471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471

Editor: Hafiz T. A. Khan, University of West London, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: July 28, 2017; Accepted: October 2, 2017; Published: November 8, 2017

Copyright: © 2017 Mellins et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the study cannot be made available, beyond the aggregated data that are included in the paper, because of concerns related to participant confidentiality. Sharing the individual-level survey data would violate the terms of our agreement with research participants, and the Columbia University Medical Center IRB has confirmed that the potential for deductive identification and the risk of loss of confidentiality is too great to share the data, even if de-identified.

Funding: This research was funded by Columbia University through a donation from the Levine Family. The funder (Levine Family) had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Recent estimates of sexual assault victimization among college students in the United States (US) are as high as 20–25% [ 1 – 3 ], prompting universities to enhance or develop policies and programs to prevent sexual assault. However, a 2016 review [ 4 ] highlights the variation in sexual assault prevalence estimates (1.8% to 34%) which likely can be attributed to methodological differences across studies, including varying sexual assault definitions, sampling methods, assessment timeframes, and target populations [ 4 ]. Such differences can hamper efforts to understand the scope of the problem. Moreover, while accurate estimates of prevalence are crucial for calling attention to the population-health burden of sexual assault, knowing more about risk factors is critical for determining resource allocation and developing effective programs and policies for prevention.

Reasons for the variation in prevalence estimates include different definitions of sexual assault and assessment methods. Under the rubric of sexual assault, researchers have investigated experiences ranging from sexual harassment at school or work, to unwanted touching, including fondling on the street or dance floor, to either unwanted/non-consensual attempts at oral, anal or vaginal sexual intercourse (attempted penetrative sex), or completed penetrative sex [ 3 , 5 – 7 ]. Some studies have focused on a composite variable of multiple forms of unwanted/non-consensual sexual contact [ 8 , 9 ] while others focus on a single behavior, such as completed rape [ 10 ]. Some studies focus on acts perpetrated by a single method (e.g. incapacitation due to alcohol and drug use or other factors) [ 11 ], while others include a range of methods (e.g., physical force, verbal coercion, and incapacitation) [ 12 – 15 ]. In general, studies that ask about a wide range of acts and use behaviorally specific questions about types of sexual assault and methods of perpetration have yielded more accurate estimates [ 16 ]. Behavioral specificity avoids the pitfall of participants using their own sexual assault definitions and does not require the respondent to identify as a victim or survivor, which may lead to underreporting [ 10 , 17 – 19 ].

Although an increasing number of studies have used behaviorally specific methods and examined prevalence and predictors of sexual assault [ 20 , 21 ], they typically have used convenience samples. Only a few published studies have used population-based surveys and achieved response rates sufficient to mitigate some of the concerns of sample response bias [ 4 ]. US federal agencies have urged universities to implement standardized “campus climate surveys” to assess the prevalence and reporting of sexual violence [ 22 ]. Although these surveys have emphasized behavioral specificity, many have yielded low response rates (e.g., 25%) [ 23 ], particularly among men [ 24 ], creating potential for response bias in the obtained data. Population-based probability samples with behavioral specificity, good response rates, sufficiently large samples to examine risk for specific subgroups (e.g., sexual minority students), and detailed information on personal, social, or contextual risk factors (e.g., alcohol use) [ 22 , 23 ] are needed to more accurately define prevalence and inform evidence-based sexual assault prevention programs.

Existing evidence suggests that most sexual assault incidents are perpetrated against women [ 25 ]; however, few studies have examined college men as survivors of assault [ 26 – 28 ]. Furthermore, our understanding of how sexual orientation and gender identity relate to risk for sexual assault is limited, despite indications that lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB), and gender non-conforming (GNC) students are at high risk [ 29 – 31 ]. It is unclear if these groups are at higher risk for all types of sexual assault or if prevention programming should be tailored to address particular types of assault within these groups. Also, although women appear to be at highest risk for assault during freshman year [ 32 , 33 ], the dearth of studies with men or GNC students have limited conclusions about whether freshman year is also a risky period for them.

Additional factors associated with experiencing sexual assault in college students include being a racial/ethnic minority student (although there are mixed findings on race/ethnicity) [ 34 , 35 ], low financial status, and prior history of sexual assault [ 3 , 33 , 36 ]. Other risk factors include variables related to student social life, including being a freshman [ 24 ], participating in fraternities and sororities [ 19 , 37 , 38 ], binge drinking [ 1 , 39 ] and participating in “hook-up” culture [ 40 – 42 ]. Whether sexual assault is happening in the context of more casual, typically non-committal sexual relationships (“hook-ups”) [ 40 ] vs. steady intimate or monogamous relationships has important implications for prevention efforts.

To fill some of these knowledge gaps, we examined survey data collected from a large population-based random sample of undergraduate women, men, and GNC students at Columbia University (CU) and Barnard College (BC). The aims of this paper are to:

- Estimate the prevalence of types of sexual assault incidents involving a) sexualized touching, b) attempted penetrative (oral, anal or vaginal) sex, and c) completed penetrative sex since starting at CU/BC;

- Describe the methods of perpetration (e.g., incapacitation, physical force, verbal coercion) used; and

- Examine associations between key sociodemographic, social and romantic/sexual relationship factors and different types of sexual assault victimization, and how these associations differ by gender.

Materials and methods

This study used data from a population-representative survey that formed one component of the Sexual Health Initiative to Foster Transformation (SHIFT) study. SHIFT used mixed methods to examine risk and protective factors affecting sexual health and sexual violence among college undergraduates from two inter-related institutions, CU’s undergraduate schools (co-educational) and BC (women only), both located in New York City. SHIFT featured ethnographic research, the survey, and a daily diary study. Additionally, SHIFT focused on internal policy-translation work to inform institutionally-appropriate, multi-level approaches to prevention.

Participants

Survey participants were selected via stratified random sampling from the March 2016 population of 9,616 CU/BC undergraduate students ages 18–29 years. We utilized evidence-based methods to enhance response rates and sample representativeness [ 22 , 43 ]. Using administrative records of enrolled students, 2,500 students (2,000 from CU and 500 from BC) were invited via email to participate in a web-based survey. Of these 2,500 students, 1,671 (67%) consented to participate (see Procedures). Among those who consented to participate, 80.5% were from CU and 19.5% were from BC (see Table 1 below for demographic data on the CU/BC student population, the random sample of students contacted, the survey responders, and the current analytic sample).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.t001

SHIFT employed multiple procedures to assure protection of students involved in our study; these procedures also improve scientific rigor. The study was approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and we obtained a federal Certificate of Confidentiality to legally protect our data from subpoena. SHIFT also obtained a University waiver from reporting on individual sexual assaults, as reporting would obviate student privacy and willingness to participate. Students were offered information about referrals to health and mental health resources during the consent process and at the end of the survey, and such information was available from SHIFT via other communication channels. Finally, in reporting data we suppressed data from tables where there were less than 3 subjects in any cell to avoid the possibility of deductive identification of an individual student [ 44 ].

SHIFT used principles of Community Based Participatory Research regarding ongoing dialogue with University stakeholders on study development and implementation to maximize the quality of data and impact of research findings [ 45 ]. This included weekly meetings between SHIFT investigators and an Undergraduate Advisory Board, consisting of 13–18 students, reflecting the undergraduate student body’s diversity in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, year in school, and activities (e.g., fraternity/sorority membership). It also included regular meetings with an Institutional Advisory Board comprised of senior administrators, including CU’s Office of General Counsel, facilities, sexual violence response, student conduct, officials involved in gender-based misconduct concerns, athletics, a chaplain, mental health and counseling, residential life, student health, and student life.

Following both the Undergraduate Advisory Board’s recommendations and Dillman’s Tailored Design Method for maximizing survey response rates [ 43 ], multiple methods were used to advertise and recruit students. These included: a) email messages, both to generate interest and remind students who had been selected to participate, crafted to resonate with diverse student motives for participation (e.g., interest in sexual assault, compensation, community spirit, and achieving higher response rates than surveys at peer institutions), b) posting flyers, c) holding “study breaks,” in which students were given snacks and drinks, and d) tabling in public areas on campus.

Participants used a unique link to access the survey either at our on-campus research office where computers and snacks were provided (16% of participants) or at a location of their choosing (84% of participants) from March-May, 2016. Before beginning the survey, participants were asked to provide informed consent on an electronic form describing the study, confidentiality, compensation for time and effort, data handling procedures, and the right to refuse to answer any question. Students who completed the survey received $40 in compensation, given in cash to those who completed the survey in our on-campus research office or as an electronic gift card if completed elsewhere. Students were also entered into a lottery to win additional $200 electronic gift cards. This compensation was established based on feedback from student and institutional advisors and reviewed by our Institutional Review Board. It was judged to be sufficient to promote participation, and help ensure that we captured a representative sample, including students who might otherwise have to choose between paid opportunities and participating in our survey, but not great enough to feel coercive for low resource students. This amount of compensation is in line with other similar studies [ 46 ]. On average, the survey took 35–40 minutes to complete.

The SHIFT survey included behaviorally-specific measures of different types of sexual assault, perpetrated by different methods, as well as measures of key sociodemographic, social and sexual relationship factors, and risk environment characteristics. The majority of instruments had been validated previously with college- age students. The survey was administered in English using Qualtrics ( www.qualtrics.com ), providing a secure platform for online data collection.

Sexual assault.

Sexual assault was assessed with a slightly modified version of the revised Sexual Experiences Survey [ 16 ], the most widely used measure of sexual assault victimization with very good psychometric properties including internal consistency and validity previously published [ 17 , 47 ]. The Sexual Experiences Survey employs behaviorally specific questions to improve accuracy [ 18 ]. The scale includes questions on type of assault, including sexualized touching without penetration (touching, kissing, fondling, grabbing in a sexual way), attempted but not completed penetrative assault (oral, vaginal, anal or other type of penetration; herein referred to as attempted penetrative assault) and completed penetrative assault (herein referred to as penetrative assault). We used most of the Sexual Experiences Survey as is. However, with strong urging from our Undergraduate Advisory Board, we made a modification, combining the questions about different types of penetration (oral, vaginal, etc.) rather than asking about each kind separately. In the Sexual Experiences Survey, for each type of assault there are six methods of perpetration. Two of the types reflect verbal coercion: 1) “Telling lies, threatening to end the relationship, threatening to spread rumors about me, making promises I knew were untrue, or continually verbally pressuring me after I said I didn’t want to” (herein referred to as “lying/threats”), and 2) “Showing displeasure, criticizing my sexuality or attractiveness, getting angry but not using physical force, after I said I didn’t want to” (herein referred to as “criticism”). The remaining types included use of physical force, threats of physical harm, or incapacitation (“Taking advantage when I couldn’t say no because I was either too drunk, passed out, asleep or otherwise incapacitated”), and other. For each incident of sexual assault, participants could endorse multiple methods of perpetration. Participants were also asked to report whether these experiences occurred: a) during the current academic year (this was a second modification to the Sexual Experiences Survey) and/or b) since enrollment but prior to the current academic year. For this paper, data for the two time periods were combined, reflecting the entire period since starting CU/BC. See Fig 1 for a replica of the questionnaire.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.g001

Demographics.

Demographics included gender identity (male, female, trans-male/trans-female, gender queer/gender-non-conforming, other) [ 48 ], year in school (e.g., freshman, sophomore, junior, senior), age, US born (yes/no), lived in US less than five years (yes/no; proxy for recent international student status), transfer student (yes/no), low socioeconomic status (receipt of Pell grant-yes/no [need-based grants for low-income students, with eligibility dependent on family income]); how often participant has trouble paying for basic necessities (never, rarely, sometimes, often, all of the time), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic-Asian, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic/Latin-x, other [other included: American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, More than one Race/Ethnicity, Other]). Gender was categorized as follows: female, male and GNC (students who responded to gender identity question as anything other than male or female).

Fraternity/Sorority.

Fraternity/sorority membership (ever participated) was assessed with one question from a school activities checklist (yes/no). We report on Greek life participation here to engage with the substantial attention this has received as a risk factor.

Problematic drinking.

Problematic drinking during the last year was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [ 49 ], a widely used, well-validated standardized 10-item screening tool developed by the World Health Organization. Psychometrics have been established in numerous studies [ 50 – 52 ]. The AUDIT assesses alcohol consumption, drinking behaviors, and alcohol-related problems. Participants rate each question on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (daily or almost daily) for possible scores ranging from 0 to 40. The range of AUDIT scores represents varying levels of risk: 0–7 (low), 8–15 (risky or hazardous), 16–19 (high-risk or harmful), and 20 or greater (high-risk). We also examined one AUDIT item on binge drinking, defined as having 6+ drinks on one occasion at least monthly [ 49 ].

Sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation was assessed with one question with the following response options (students could select all that applied): asexual, pansexual, bisexual, queer, heterosexual and homosexual, as well as other [ 53 , 54 ]. Students were categorized into four mutually exclusive groups for analyses: heterosexual, bisexual, homosexual, and other which included asexual, pansexual, queer, or another identity not listed. Non-heterosexual students who indicated more than one orientation were assigned hierarchically to bisexual, homosexual, then other.

Romantic/sexual relationships.

Romantic/sexual relationships since enrollment at CU/BC were assessed with one question. Response choices included: none, steady or serious relationship, exclusive or monogamous relationship, hook-up-one time, and ongoing hook-up or friends with benefits. Students defined “hookup” for themselves. Students could check all that applied. This variable was trichotomized: at least one hook-up, only steady or exclusive/monogamous relationships, and no romantic/sexual relationships.

Pre-college sexual assault.

Students also were asked one yes/no question on whether they had experienced any unwanted sexual contact prior to enrolling at CU/BC.

Data analysis

To assess the representativeness of the sample, the distribution of demographic variables based on administrative records from CU and BC for the total University undergraduate population were compared to the random sample of students contacted, the survey responders, and the current analytic sample, which consists of students that responded to the questions about sexual assault. Demographics for survey responders are based on self-report from the survey. Cramer’s V effect size was used to assess the magnitude of the differences in demographic distributions between the CU/BC population and respondent sample where smaller values (i.e. Cramer’s V <0.10) indicate strong similarity [ 55 ].

Analyses were performed on each type of sexual assault as well as a combined “Any type of sexual assault” variable: yes/no experienced sexualized touching, attempted penetrative assault, and/or penetrative assault since CU/BC. Prevalence of each type of sexual assault was calculated by gender and year in school, with chi-square tests of difference used to compare prevalence between genders across each year in school versus freshman year. The total number of incidents of assault and the mean, median and standard deviation for number of incidents of assault per person reporting at least one assault were summarized. Among individuals who experienced any type of sexual assault, the proportions that experienced a particular method of perpetration (e.g. incapacitation, physical force) were calculated by type of sexual assault. Chi-square tests compared proportions between males and females for each perpetration method. The associations of each key correlate with the odds of experiencing any sexual assault were calculated and tested using logistic regression stratified by male/female gender. In addition, a multinomial regression with hierarchical categories (no assault, sexualized touching only, attempted penetrative assault [not completed], and penetrative assault [completed]) as the outcome was performed to examine if associations differed by type of sexual assault. To adjust for the fact that the sample comes from a finite population (i.e. CU/BC N = 5,765 women; N = 3,851 men), a standard finite population correction was implemented for standard error estimation using SAS Proc Surveylogistic. Given the low sample size of GNC students, they were excluded from some analyses. All analyses were conducted using SAS (v. 9.4).

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents demographic data on the full University, the randomly selected sample, the respondents and the analytic sample for this paper. Among students who consented to the survey (n = 1,671), 46 stopped the survey before the sexual assault questions and 33 refused to answer them resulting in an analytic sample of n = 1,592 (95% completion among responders). Demographic characteristics (i.e. gender [male, female], age, race/ethnicity, year in school, international status, and economic need [Pell grant status]) of the respondent sample were very similar (Cramer’s V effect size differences all <0.10 [ 55 ]) to the full CU/BC population ( Table 1 ) indicating that the responder and final analytic samples were representative of the student body population.

The analytic sample included 58% women, 40% men, and 2% GNC students (4 students refused to identify their gender) and was distributed evenly by year in school with most (92%) between18-23 years of age. Self-reported race/ethnicity was 43% white non-Hispanic, 23% Asian, 15% Hispanic/Latino, and 8% black non-Hispanic; 13% were transfer students, and the majority of the sample was born in the US (76%). Twenty-three percent of participants received Pell grants and 51% of students acknowledged at least sometimes having difficulty paying for basic necessities.

The majority of women (79%) and men (85%) identified as heterosexual. In terms of romantic/sexual relationships since starting CU/BC, 30.0% of women and 21.6% of men reported no relationships, 21.0% of women and 22.6% of men reported only steady/exclusive relationships with no hookups, and 49.0% of women and 55.7% of men reported at least one hook-up. Finally, 25.5% of women, 9.4% of men, and 47.0% of GNC students reported pre-college sexual assault.

Aim 1: Prevalence of sexual assault victimization at CU/BC

Overall rates by gender and school year..

Since starting CU/BC, 22.0% (350/1,592) of students reported experiencing at least one incident of any sexual assault across the three types (sexualized touching, attempted penetrative assault, and penetrative assault). Table 2 presents data on types of assault by gender and year in school. Women were over twice as likely as men to report any sexual assault (28.1% vs 12.5%). There was evidence of cumulative risk for experiencing sexual assault among women over four years of college, so that by junior and senior year, respectively, 29.7% and 36.4% of women reported experiencing any sexual assault, compared to 21.0% of freshman women who had only one year of possible exposure (p < .05). However, one-fifth (21.0%) of women who took the survey as freshman had experienced unwanted sexual contact, compared to 36.4% over 3+ years (seniors), suggesting that as others have found, the risk of assault is highest in freshman year.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.t002

Among men, one in eight indicated that they had been sexually assaulted since starting CU. Similar to women, the risk for sexual assault among men accumulated over the four years of college, with 15.6% of seniors vs 9.9% of freshman reporting a sexual assault since entering CU, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Although the numbers were small, GNC students reported the highest prevalence of sexual assault since starting CU/BC (38.5%; 10/26). Numbers were too small (n<3) to present stratified by year in school (see Table 2 ).

Types of sexual assault by gender ( Table 2 ).

The most prevalent form of sexual assault was sexualized touching; rates for women (23.6%) and GNC students (38.5%) were significantly higher than rates for men (11.0%; p < .05). Prevalence of attempted penetrative assault and penetrative assault were about half that of sexualized touching. Compared to men, women were three times as likely to report attempted penetrative assault (11.1% vs 3.8%) and over twice as likely to experience penetrative assault (13.6% vs 5.2%). Among GNC students, the majority reporting sexualized touching, with rates of the other two types too small to report.

Experiencing multiple sexual assaults ( Fig 2 ; S1 Table ).

Students could report multiple types of sexual assault incidents (i.e. sexualized touching, attempted penetrative, and penetrative assault) as well as multiple incidents experienced of each type. Overall, students reported a total of 1,007 incidents of sexual assault experienced since starting CU/BC. For the 350 students who indicated any sexual assault, the median number of incidents experienced was 3.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.g002

Among the 350 students reporting any sexual assault, Fig 2 presents different combinations of sexual assault experienced by students since CU/BC. Most prevalent, 38.0% reported experiencing only sexualized touching; 19.0% reported both sexualized touching and penetrative assault incidents; 17.0% experienced all three types of assault; and 12.0% sexualized touching and attempted penetrative assault.

Aim 2: Methods of perpetration (lying/threats, criticism, incapacitation, physical force, threats of harm, and other) by gender ( Table 3 )

Across types of assault, incapacitation was the method of perpetration reported most frequently (> 50%) in both men and women. For both women and men, approximately two-thirds of all penetrative assaults and about half of sexualized touching and attempted penetrative assaults involved incapacitation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.t003

Physical force was reported significantly more frequently by women than men (34.6% vs 12.7%) for any sexual assault. More specifically, compared to men, women were three times more likely to experience sexualized touching via physical force (32.1% vs. 10.0%), and six times more likely to experience penetrative assaults via physical force (33.3% vs 6.1%).

Lastly, a sizeable number of respondents reported verbal coercion (ranging from 21.0% to over 40.0% depending on type of assault). Criticism was cited by women at rates similar to physical force for both sexualized touching and penetrative assaults. Among men, both verbal coercion methods were cited most frequently after incapacitation for all three types of assault.

For GNC students, we examined rates of each perpetration method for only the composite variable any sexual assault (due to small numbers in any specific type of assault). Among those who experienced an assault, incapacitation was the most frequently mentioned method (50.0%), followed by criticism (40.0%).

Aim 3: Identify factors associated with sexual assault experiences

We examined the association between sexual assault (both any sexual assault [ Table 4 ] and each type of sexual assault [ Table 5 ]) and key demographic, sexual history and social activity factors. Results are stratified by gender (women/men).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.t004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.t005

Race/Ethnicity.

For both women and men, the prevalence of any sexual assault was similar for all race/ethnicity groups compared to non-Hispanic White students with one exception. Asian students (women and men) were less likely to experience any sexual assault than non-Hispanic White students. For women only, differences emerged by type of assault. Asian women compared to non-Hispanic White women were less likely to experience penetrative assault (OR = 0.35, CI: 0.19–0.62), but not attempted penetrative assault (OR = 0.56, CI: 0.25–1.26), nor sexualized touching only (OR = 1.00, CI: 0.59–1.69). Black women were found to have increased odds of touching only incidents compared to non-Hispanic White women (OR = 1.99, CI: 1.05–3.74). There were no other significant racial or ethnic differences.

Economic precarity.

Women who often or always had difficulty paying for basic necessities had increased odds of any sexual assault; for men the trend was similar but it did not reach statistical significance. Considering penetrative assault specifically, both men and women who often or always had difficulty paying for basic necessities had increased risk (women OR = 2.24, CI: 1.23–4.09; men OR = 3.07, CI: 1.04–9.07) compared to those who never had difficulty.

Transfer student.

Women transfer students were less likely to experience any sexual assault than non-transfer students. Closer inspection of type of assault revealed that this protective effect was seen for sexualized touching only (OR = 0.34, CI: 0.15–0.80), but not for penetrative (OR = 0.60, CI: 0.34–1.08), nor attempted penetrative (OR = 1.03, CI: 0.48–2.21) assault. There were no significant differences between men who were transfer students and those who were not.

For women, those who identified as bisexual and those who identified as some other sexual identity besides heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual (includes people endorsing exclusively one or a combination of: Asexual, Pansexual, Queer, or a sexual orientation not listed), were more likely to experience any sexual assault than heterosexual students. For penetrative assault specifically, this increased risk was only present for individuals with some other sexual identity (OR = 2.11, CI: 1.20–3.73). For men, those who identified as homosexual were more likely to experience any sexual assault than heterosexual male students. For penetrative assault specifically, those who identified as homosexual, bisexual, or some other sexual identity all had substantially increased risk compared to those with a heterosexual identity (OR = 4.74, CI: 2.10–10.71; OR = 3.39, CI: 1.03–11.16; OR = 4.74, CI:1.10–20.48, respectively).

Information about the gender of the perpetrator for different gender and sexual orientation groups was available for a subset of incidents (336/997). Among these events, 98.4% (3/184) of the heterosexual women indicated the perpetrator was a man, while 97.1% (33/34) of the bisexual women, 75% (3/4) of the homosexual women, and 88.9% (24/27) of the other sexual identity women indicated it was a man. For men who were assaulted, 84.9% (45/53) of the heterosexual men reported the perpetrator was a woman, while 0 of the homosexual men said the perpetrator was a woman. Numbers for bisexual men and other sexual identity men were too small to report separately, but combined showed that 5/8 (63.0%) of bisexual and other sexual identity men said the perpetrator was a woman. Of the GNC students reporting on a most-significant event, 77.8% (7/9) reported that they were assaulted by a male perpetrator (the numbers are too small to further examine by sexual orientation).

Lived in US less than 5 years.

There was no association found between living in the US for less than 5 years and any sexual assault, nor any specific type of sexual assault.

Relationship status.

Among both women and men, students who had at least one hook-up were more likely to have experienced any sexual assault than students who were in only steady/exclusive relationships since starting college. Among women who had engaged in at least one hook-up, this increased risk held for each type of sexual assault (penetrative: OR = 5.03, CI = 2.91–8.68, attempted penetrative: OR = 4.43, CI = 1.83–10.8, sexualized touching only: OR = 3.26, CI = 1.74–6.09), while among men the increased risk was found for sexualized touching only (OR = 13.33, CI = 2.09–85.08), but could not be estimated (due to small numbers) for completed penetrative assault. Women who did not have any romantic or sexual relationship since CU/BC were found to be less likely to experience penetrative assault than women who had a steady/exclusive relationships only (OR = 0.05, CI: 0.01–0.31).

Fraternity/Sorority membership.

Although a relative minority of students participated in fraternities (24.1%) or sororities (18.2%), for both men and women, those who participated were more likely to experience any sexual assault than those who did not. Examination of type of assault revealed that the effect is driven primarily by sexualized touching only which is significant in both women (OR = 1.63, CI: 1.00–2.67) and men (OR = 2.40, CI: 1.25–4.63) and not significantly increased for penetrative nor attempted penetrative assault.

Risky or hazardous drinking.

For both men and women, individuals who met criteria on the AUDIT for risky or hazardous drinking were more likely to experience any sexual assault than those who did not. When examining each type of assault separately, for men this increased risk was only significant for penetrative assault (OR = 4.07, CI: 2.01–8.21). For women, the increased risk of assault held for each type of assault—penetrative (OR = 6.04, CI: 4.10–8.90), attempted (OR = 3.38, CI: 1.84–6.19) and touching (OR = 2.33, CI: 1.42–3.81). We also looked at one AUDIT item specifically on binge drinking (6 or more drinks on a single occasion). Individuals who reported binge drinking at least monthly were more likely to experience any sexual assault than those who did not. When examining each type of assault separately, for men this increased risk was only significant for penetrative assault (OR = 2.15, CI: 1.12–4.15). For women, this increased risk was significant for penetrative assault (OR = 3.12, CI: 2.09–4.65), attempted assault (OR = 2.28, CI: 1.20–4.33), and touching (OR = 2.42, CI:1.50–3.91).

Pre-college assault ( Table 5 ).

Among both women and men, those who experienced pre-college assault were more likely to experience any sexual assault while at CU/BC. The increased risk held for penetrative assault in both women (OR = 3.01, CI: 2.07–4.37) and men (OR = 2.44, CI: 1.03–5.76). In women, the increased risk also held for attempted penetrative, but not touching only, whereas in men, the increased risk held for touching only, but not attempted penetrative sex.

The SHIFT survey, with a population-representative sample, good response rate and behaviorally-specific questions, found that 22.0% of students reported a sexual assault since starting college, which confirms previous studies of 1 in 4 or 1 in 5 prevalence estimates with national samples and a range of types of schools [ 23 , 24 ]. However, a key finding is that focusing only on the “1 in 4/ 1 in 5” rate of any sexual assault obscures much of the nuance concerning types of sexual assault as well as the differential group risk, as prevalence rates were unevenly distributed across gender and several other social and demographic factors.

Similar to other studies [ 4 , 24 ], women had much higher rates of experiencing any type of sexual assault compared to men (28.0% vs 12.0%). Moreover, our data suggest a cumulative risk for sexual assault experiences over four years of college with over one in three women experiencing an assault by senior year. However, our data also suggest that freshman year, particularly for women, is when the greatest percentage experience an assault. This supports other work on freshman year as a particularly critical time for prevention efforts, otherwise known as the “red zone” effect for women [ 32 ].

Importantly, our study confirms that GNC students are at heightened risk for sexual assault [ 23 ]. They had the highest proportion of sexual assaults, with 38.0% reporting at least one incident, the majority of which involved unwanted/non-consensual sexualized touching. These data should be interpreted very cautiously given the small number of GNC students. However, increasingly studies suggest that transgender and other GNC students have sexual health needs that may not be targeted by traditional programming [ 57 ]; thus, a better understanding of pathways to vulnerability among these students is of high importance.

Similarly, students who identified as a sexual orientation other than heterosexual were at increased risk for experiencing any sexual assault, with bisexual women or women who identified as “other” and men who identified as any non-heterosexual category at increased risk. Similar to GNC students, understanding the specific social and sexual health needs of LGB students, particularly as it relates to reducing sexual assault risk is critical to prevention efforts [ 58 ]. Factors such as stigma and discrimination, lack of communication, substance use, as well as a potential lack of tailored prevention programs may play a role. To our knowledge, there are no evidence-based college sexual assault prevention programs targeting LGB and GNC students. Our data suggest that the LGB and GNC experiences are not uniform; more research should be done within each of these groups to understand the mechanisms behind their potentially unique risk factors.

Our data also suggest that the 20–25% rate of any sexual assault obscures variation in assault experiences. Sexualized touching accounted for the highest percentage of acts across gender groups, with over one-third of participants reporting only sexualized touching incidents. Rates of attempted and completed penetrative sexual assault were about half the rate of sexualized touching. This finding does not minimize the importance of addressing unacceptably high rates of attempted penetrative and penetrative assault (14%-15%), but it does suggest the importance of specificity in prevention efforts. For GNC students, for example, the risk of assault was primarily for sexualized touching with very few reporting attempted penetrative assault or penetrative assault during their time at CU/BC. These elevated rates of unwanted sexual touching may be a combination of GNC students’ focus on their gendered sexual boundaries–and thus potentially greater awareness of when advances are unwanted–at a developmental moment when they are building non-traditional gender identities, as well as these students’ social vulnerability. Further investigation is warranted.

Moreover, there was variation in methods of perpetration reported by survivors of sexual assault. Incapacitation was the most common method reported across all gender groups for each type of assault, and female and male students who reported risky or hazardous drinking were at increased risk for experiencing any sexual assault, particularly penetrative assault. Across campuses in the US, hazardous drinking is a national problem with substantive negative health outcomes, risk for sexual assault being one of them [ 2 , 39 , 59 ]. Our data underline the potential of programs and policies to reduce substance use and limit its harms as one element of comprehensive sexual assault prevention; we found few evidence-based interventions that address both binge drinking and sexual assault prevention. Of course, any work addressing substance use as a driver of vulnerability must do so in a way that does not replicate victim-blaming.

However, similar to other studies with broad foci, incapacitation was not the only method of perpetration reported. For women, physical force, particularly for penetrative sex, was the second most frequently endorsed method. Verbal coercion, including criticism, lying and threats to end the relationship or spread rumors, was also employed at rates similar to physical force for women, and was the second most frequently endorsed category for men and GNC students. Prevention programs, such as the bystander interventions which are the focus of efforts on many campuses [ 60 ], often focus on incapacitation or physical force. These interventions tend to highlight situations where survivors (typically women) are vulnerable because they are under the influence of substances. In SHIFT, verbal coercion is also shown to be a powerful driver of assault; however, it typically does not receive as much attention as rape, which is legally defined as penetration due to physical force or incapacitation. If a survivor is verbally coerced into providing affirmative consent, the incident could be considered within consent guidelines of “yes means yes” but it may have been unwanted by the survivor [ 61 , 62 ]. Assertiveness interventions and those that focus on verbal consent practices may be useful for addressing this form of assault.

We also found high rates of re-victimization. As others have found, pre-college sexual assault was a key predictor for experiencing assault at CU/BC [ 33 , 36 ]. However, we also found high rates of repeat victimization since starting at CU/BC with a median of 3 incidents per person reporting any sexual assault since starting CU/BC, and the highest risk of repeat victimization in women and GNC students. These data underline the importance of prevention efforts that include care for survivors to reduce the enhanced vulnerability that has been shown in other populations of assault survivors [ 36 ]. Future studies should also seek to disaggregate the relationship between type of victimization (sexualized touching, attempted penetrative assault, penetrative assault) and repeat victimization.

This study also identified a number of variables associated with sexual assault, some similar to previous studies and others different. As noted, gender was a key correlate. While prevention efforts should respond to the population-level burden by focusing on the needs of women and GNC students, it is important to note that men were also at risk of sexual assault. In our study, nearly 1 in 8 men reported a sexual assault experience, a rate also found in the Online College Social Life survey [ 56 ], but higher than other studies [ 63 , 64 ]. Few programs target men, and issues around masculinity and gender roles may make it difficult for men to consider or report what has happened to them as sexual assault. Importantly, this study found that men who were members of fraternities were at higher risk for experiencing assault (specifically unwanted/nonconsensual sexualized touching) than those who were not members. This is consistent with previous findings, including the Online College Social Life survey [ 56 ], but is of particular note because research has identified men in fraternities as more likely to be perpetrators [ 64 ], but few, if any, studies have looked at fraternity members’ vulnerability to sexual assault. Our data suggest a need for further examination of the cultural and organizational dimensions of Greek life that produce this heightened risk of being assaulted for both men and women. However, it is important to note that we did not examine a range of other social and extracurricular groups which may have produced risk as well and thus a more full examination of student undergraduate life is needed.

One other key factor associated with assault was participation in “hook ups”. Both male and female students who reported hooking up were more likely to report experiencing sexual assault, compared to students who only had exclusive or monogamous relationships and those who had no sexual relationships. The role of hooking up on college campuses has received much attention in the popular press and in a number of books [ 65 , 66 ], but little has been written about its connection to sexual assault, although several recent studies are in line with ours about its role as a risk factor for experiencing sexual assault on college campuses [ 40 , 41 ]. Multiple mechanisms may be at work: students who participate in hookups may be having sex with more people, and thus face greater risk of assault due to greater exposure to sex with a potential perpetrator, but students who participate in hookups may also face increased vulnerability because many hookups involve “drunk” sex, or because hookups by definition involve sexual interactions between people who are not in a long-term intimate relationship, and thus whose bodies and social cues maybe unfamiliar to each other. Alternatively some aspects of hook-ups may be more or less risky than others and therefore continued study of different dimensions of these more casual relationships that can refer to a wide-range of behaviors is necessary.

Several demographic characteristics were not for the most part associated with sexual assault. We did not find racial or ethnic differences in sexual assault risk with primarily one exception, Asian male and female students were at less risk overall compared to white students. We also did not find transfer students to be at greater risk; female transfer students were actually at lower risk, potentially due to less exposure time, particularly during freshman year. International student status as indicated by having been in the US<5 years was also not associated with increased risk. However, this study highlights the role of economic factors that have received limited attention in the literature. Little is known about how economic insecurity may drive vulnerability, but issues of power, privilege, and control of alcohol and space all require further examination.