How to Read a Scholarly Article

- Introduction

Article Text

- References/Works Cited

- 2. Sections of a Scholarly Article: Humanities Article

Sections of a Scholarly Journal Article About Scientific Research

Let's look at the different parts of a scholarly article that presents scientific research:

- Brief description of the article

- You can read this to decide whether you want to read the entire article.

Introduction:

- Description of the problem, or the research question, and why this study is being done

- Sometimes includes a short literature review

- The main part of an article is its body text.

- This is where the author analyzes the argument, research question, or problem. This section also includes analysis and criticism.

- The author may use headings to divide this part of the article into sections.

Scientific research articles may include these sections:

- Literature review (Discussion of other sources, such as books and articles, that informed the author(s) of this article)

- Methods (Description of the way the research study was set up and how data was collected)

- Results (Presentation of the research study results)

- Discussion (Discussion of whether the results of the study answer the research question)

You may see some of these same sections in articles that present humanities scholarship.

Conclusion:

- Wraps up the article.

- This section isn't always labeled.

- Description of how this article or research study contributes to or builds on the previous research of other scholars.

- Also includes ideas for future research others might do on this topic.

References/Works Cited:

List of resources (books, articles, etc.) cited in this article.

This example uses pages from this article: Sampson, L., Ettman, C., Abdalla, S., Colyer, E., Dukes, K., Lane, K., & Galea, S. (2021). Financial hardship and health risk behavior during COVID-19 in a large US national sample of women. SSM - Population Health, 13, 100734–100734 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100734

- << Previous: Home

- Next: 2. Sections of a Scholarly Article: Humanities Article >>

- Last Updated: Nov 28, 2023 2:22 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sjf.edu/scholarly-article

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Digital Health Device Collection

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

- Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

Scientific Writing: Sections of a Paper

- Sections of a Paper

- Common Grammar Mistakes Explained

- Citing Sources

Introduction

- Materials & Methods

Typically scientific journal articles have the following sections:

Materials & Methods

References used:

Kotsis, S.V. and Chung, K.C. (2010) A Guide for Writing in the Scientific Forum. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 126(5):1763-71. PubMed ID: 21042135

Van Way, C.W. (2007) Writing a Scientific Paper. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 22: 663-40. PubMed ID: 1804295

What to include:

- Background/Objectives: include the hypothesis

- Methods: Briefly explain the type of study, sample/population size and description, the design, and any particular techniques for data collection and analysis

- Results: Essential data, including statistically significant data (use # & %)

- Conclusions: Summarize interpretations of results and explain if hypothesis was supported or rejected

- Be concise!

- Emphasize the methods and results

- Do not copy the introduction

- Only include data that is included in the paper

- Write the abstract last

- Avoid jargon and ambiguity

- Should stand-alone

Additional resources: Fisher, W. E. (2005) Abstract Writing. Journal of Surgical Research. 128(2):162-4. PubMed ID: 16165161 Peh, W.C. and Ng, K.H. (2008) Abstract and keywords. Singapore Medical Journal. 49(9): 664-6. PubMed ID: 18830537

- How does your study fit into what has been done

- Explain evidence using limited # of references

- Why is it important

- How does it relate to previous research

- State hypothesis at the end

- Use present tense

- Be succinct

- Clearly state objectives

- Explain important work done

Additional resources: Annesley, T. M. (2010) "It was a cold and rainy night": set the scene with a good introduction. Clinical Chemistry. 56(5):708-13. PubMed ID: 20207764 Peh, W.C. and Ng, K.H. (2008) Writing the introduction. Singapore Medical Journal. 49(10):756-8. PubMed ID: 18946606

- What was done

- Include characteristics

- Describe recruitment, participation, withdrawal, etc.

- Type of study (RCT, cohort, case-controlled, etc.)

- Equipment used

- Measurements made

- Usually the final paragraph

- Include enough details so others can duplicate study

- Use past tense

- Be direct and precise

- Include any preliminary results

- Ask for help from a statistician to write description of statistical analysis

- Be systematic

Additional resources: Lallet, R. H. (2004) How to write the methods section of a research paper. Respiratory Care. 49(10): 1229-32. PubMed ID: 15447808 Ng, K.H. and Peh, W.C. (2008) Writing the materials and methods. Singapore Medical Journal. 49(11): 856-9. PubMed ID: 19037549

- Describe study sample demographics

- Include statistical significance and the statistical test used

- Use tables and figures when appropriate

- Present in a logical sequence

- Facts only - no citations or interpretations

- Should stand alone (not need written descriptions to be understood)

- Include title, legend, and axes labels

- Include raw numbers with percentages

- General phrases (significance, show trend, etc. should be used with caution)

- Data is plural ("Our data are" is correct, "Our data is" is in-correct)

Additional resources: Ng, K.H and Peh, W.C. (2008) Writing the results. Singapore Medical Journal. 49(12):967-9. PubMed ID: 19122944 Streiner, D.L. (2007) A shortcut to rejection: how not to write the results section of a paper. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 52(6):385-9. PubMed ID: 17696025

- Did you reject your null hypothesis?

- Include a focused review of literature in relation to results

- Explain meaning of statistical findings

- Explain importance/relevance

- Include all possible explanations

- Discuss possible limitations of study

- Suggest future work that could be done

- Use past tense to describe your study and present tense to describe established knowledge from literature

- Don't criticize other studies, contrast it with your work

- Don't make conclusions not supported by your results

- Stay focused and concise

- Include key, relevant references

- It is considered good manners to include an acknowledgements section

Additional resources: Annesley, T. M. (2010) The discussion section: your closing argument. Clinical Chemistry. 56(11):1671-4. PubMed ID: 20833779 Ng, K.H. and Peh, W.C. (2009) Writing the discussion. Singapore Medical Journal. 50(5):458-61. PubMed ID: 19495512

Tables & Figures: Durbin, C. G. (2004) Effective use of tables and figures in abstracts, presentations, and papers. Respiratory Care. 49(10): 1233-7. PubMed ID: 15447809 Ng, K. H. and Peh, W.C.G. (2009) Preparing effective tables. Singapore Medical Journal. (50)2: 117-9. PubMed ID: 19296024

Statistics: Ng, K. H. and Peh, W.C.G. (2009) Presenting the statistical results. Singapore Medical Journal. (50)1: 11-4. PubMed ID: 19224078

References: Peh, W.C.G. and Ng, K. H. (2009) Preparing the references. Singapore Medical Journal. (50)7: 11-4. PubMed ID: 19644619

Additional Resources

- More from Elsevier Elsevier's Research Academy is an online tutorial to help with writing books, journals, and grants. It also includes information on citing sources, peer reviewing, and ethics in publishing

- Research4Life Training Portal Research4Life provides downloadable instruction materials, including modules on authorship skills as well as other research related skills.

- Coursera: Science Writing Coursera provides a wide variety of online courses for continuing education. You can search around for various courses on scientific writing or academic writing, and they're available to audit for free.

- << Previous: Lit Review

- Next: Grammar/Language >>

- Last Updated: Mar 20, 2024 2:34 PM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/scientificwriting

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

Writing the Five Principal Sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion

- First Online: 12 October 2013

Cite this chapter

- Karen Englander 2

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Education ((BRIEFSEDUCAT))

4595 Accesses

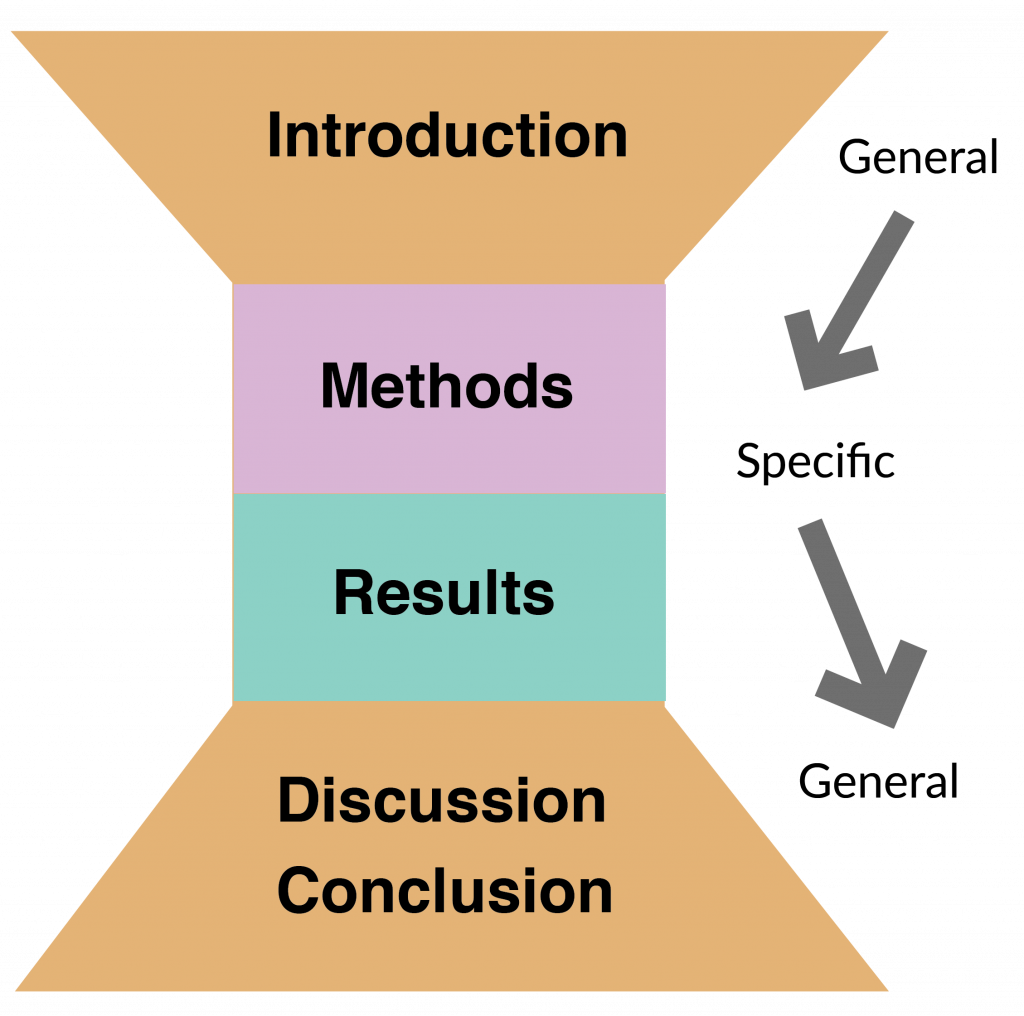

The five-part structure of research papers (Introduction, Method, Results and Discussion plus Abstract) serves as the conceptual basis for the content. The structure can be considered an “hourglass” or a “conversation” with predictable elements. Each section of the paper has its own common internal structure and linguistic features. The structures and features are explained with examples from published papers in a range of scientific disciplines. Exceptions to the four-part structure are also discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Cargill, M., & O’Connor, P. (2009). Writing scientific research articles . West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Google Scholar

Cooper, E. A., Piazza, E. A., & Banks, M. S. (2012). The perceptual basis of common photographic practice. Journal of Vision, 12 (5), 1–14.

Article Google Scholar

Esquer Mendez, J. L., Hernández Rodríguez, M., & Bückle Ramirez, L. F. (2010). Thermal tolerance and compatibility zones as a tool to establish the optimum culture condition of the halibut Paralichthys californicus (Ayres, 1859). Aquaculture Research, 41 (7), 1015–1021.

Glassman-Deal, H. (2010). Science research writing: For non-native speakers of English . London: Imperial College Press.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Penrose, A. M., & Katz, S. B. (2001). Writing in the sciences: Exploring conventions of scientific discourse . New York: Longman.

Pérez-Flores, M. A., Antonio-Carpio, R. G., Enrique Gómez-Treviño, E., & Ferguson, I. (2011). 3D inversion of control source LIN electromagnetic data. Unpublished manuscript.

Rodríguez-Santiago, M. A., & Rosales-Casián, J. A. (2011). Parasite structure of the Ocean Whitefish Caulolatilus princeps from Baja California, México (East Pacific). Helgoland Marine Research, 65 (2), 197–202.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. M., & Feak, C. (2004). Academic writing for graduate students: Essential tasks and skills (2nd ed.). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Languages, Literatures and Linguistics, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada

Karen Englander

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Karen Englander .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Englander, K. (2014). Writing the Five Principal Sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion. In: Writing and Publishing Science Research Papers in English. SpringerBriefs in Education. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7714-9_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7714-9_8

Published : 12 October 2013

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-007-7713-2

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-7714-9

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Library Instruction

Structure of typical research article.

The basic structure of a typical research paper includes Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Each section addresses a different objective.

- the problem they intend to address -- in other words, the research question -- in the Introduction ;

- what they did to answer the question in Methodology ;

- what they observed in Results ; and

- what they think the results mean in Discussion .

A substantial study will sometimes include a literature review section which discusses previous works on the topic. The basic structure is outlined below:

- Author and author's professional affiliation is identified

- Introduction

- Literature review section (a discussion about what other scholars have written on the topic)

- Methodology section (methods of data gathering are explained)

- Discussion section

- Conclusions

- Reference list with citations (sources of information used in the article)

Thanks for helping us improve csumb.edu. Spot a broken link, typo, or didn't find something where you expected to? Let us know. We'll use your feedback to improve this page, and the site overall.

Journal Article Basics

- What, Why, & Where

- Peer Review

What is an abstract?

Publication, introduction, charts, graphs, etc., article text, methods or methodology.

- Identification

- Reading an Article

- Types of Articles

Knowing about the different sections of a scholarly article and the type of information presented in each section, will make it easier to understand what the article is about. Also, reading specific parts or sections of an article can help save you time as you decide whether an article is relevant.

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article [NCSU Interactive Tutorial] Excellent interactive tool for learning about the sections of a scholarly article.

The title of a scholarly article is generally (but not always) an extremely brief summary of the article's contents. It will usually contain technical terms related to the research presented.

Authors and their credentials will be provided in a scholarly article. Credentials may appear with the authors' names, as in this example, or they may appear as a footnote or an endnote to the article. The authors' credentials are provided to establish the authority of the authors, and also to provide a point of contact for the research presented in the article. For this reason, authors' e-mail addresses are usually provided in recent articles.

On the first page of an article you will usually find the journal title, volume/issue numbers, if applicable, and page numbers of the article. This information is necessary for you to write a citation of the article for your paper.

The information is not always neatly outlined at the bottom of the first page; it may be spread across the header and footer of the first page, or across the headers or footers of opposite pages, and for some online versions of articles, it may not be present at all.

The abstract is a brief summary of the contents of the article, usually under 250 words. It will contain a description of the problem and problem setting; an outline of the study, experiment, or argument; and a summary of the conclusions or findings. It is provided so that readers examining the article can decide quickly whether the article meets their needs.

The introduction to a scholarly article describes the topic or problem the authors researched. The authors will present the thesis of their argument or the goal of their research. The introduction may also discuss the relevance or importance of the research question.

An overview of related research and findings, called a literature review, may appear in the introduction, though the literature review may be in its own section.

Scholarly articles frequently contain charts, graphs, equations, and statistical data related to the research. Pictures are rare unless they relate directly to the research presented in the article.

The body of an article is usually presented in sections, including an introduction , a literature review , one or more sections describing and analyzing the argument, experiment or study.

Scientific research articles typically include separate sections addressing the methods and results of the experiment, and a discussion of the research findings.

Articles typically close with a conclusion summarizing the findings.

The parts of the article may or may not be labeled, and two or more sections may be combined in a single part of the text. The text itself is typically highly technical, and assumes a familiarity with the topic. Jargon, abbreviations, and technical terms are used without definition.

The methods section of a scholarly article generally outlines the experimental design, the materials, and the methods (procedures) of the experiment.

The results section of a scholarly article is generally devoted to discussing the type of analysis conducted regarding the data as well as the results.

A scholarly article will end with a conclusion, where the authors summarize the results of their research. The authors may also discuss how their findings relate to other scholarship, or encourage other researchers to extend or follow up on their work.

The discussion of a scholarly article generally includes a description of how the study contributes to the existing body of research, an analysis of the research questions and hypotheses, and a discussion of the research in connection to the real world.

Most scholarly articles contain many references to publications by other authors. You will find these references scattered throughout the text of the article, as footnotes at the bottom of the page, or endnotes at the end of the article.

Most papers provide a list of references at the end of the paper. Each reference listed there corresponds to one of the citations provided in the body of the paper. You can use this list of references to find additional scholarly articles and books on your topic.

- << Previous: Peer Review

- Next: Identification >>

- Last Updated: Feb 16, 2024 2:37 PM

- URL: https://libguides.pittcc.edu/journal-articles

The Sections of a Research Article

If you’ve ever read or written almost any type of academic document, you might have noticed that they start with introductions and end with conclusions. However, research articles – as a genre – have other consistent sections as well. The complete list of sections for research articles include the following:

- Introduction

- Discussion/Conclusion

A common acronym for teaching the sections of a research article is IMRD/C. In this book, we will focus heavily on helping you understand each of those IMRD/C sections’ various pieces, including their communicative goals and strategies you can use to achieve those goals. We will also use a visual of an hourglass to demonstrate this IMRD/C organizational structure.

We hope that this graphic along with the explanations and examples in Chapters 3-6 will allow you to deepen your understanding of research writing and become a more successful author.

Preparing to Publish Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Huffman; Elena Cotos; and Kimberly Becker is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Subject Research

- Structure of Scholarly Articles and Peer Review

- Structure of a Biomedical Research Article

Structure of Scholarly Articles and Peer Review: Structure of a Biomedical Research Article

Created by health science librarians.

Title, Authors, Sources of Support and Acknowledgments

Structured abstract, introduction, results and discussion, international committee of medical journal editors (icmje).

- Compare Types of Journals

- Peer Review

Medical research articles tend to be structured in similar ways. This standard structure helps assure that research is reported with the information readers need to critically appraise the research process and results.

This guide to the structure of a biomedical research article was informed by the description of standard manuscript sections found in the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Recommendations chapter on Manuscript Preparation: Preparing for Submission .

If you are writing an article for submisson to a particular journal be sure to obtain that journal's instructions for authors for specific guidelines.

Example Article: Lyons EJ, Tate DF, Ward DS, Wang X. Energy intake and expenditure during sedentary screen time and motion-controlled video gaming. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Aug;96(2):234-9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.028423. Epub 2012 Jul 3. PubMed PMID: 22760571; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3396440. (Free full text available)

Article title: Should provide a succinct description of the purpose of the article using words that will help it be accurately retrieved by search engines.

Author information: Includes the author names and the institution(s) where each author was affiliated at the time the research was conducted. Full contact information is provided for the corresponding author.

Source(s) of support: Specific information about grant funding or source of equipment, drugs, etc. obtained to support the research.

Acknowledgments: This section may found at the end of the article and is used to name people who contributed to the paper, but not fully enough to be named as an author. It may also include more information about the authors' specific roles.

The structure of quantitative research articles is derived from the scientifc process and includes sections covering introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRaD). The actual labels for the various parts may vary between journals.

Abstract: A structured abstract reports a summary of each of the IMRaD sections. Enough information should be included to provide the purpose of the research; an outline of methods used; results with data; and conclusions that highlight the findings.

The introduction provides background information about what is known from previous related research, citing the relevant studies, and points out the gap in previous research that is being addressed by the new study. Often, many of the references cited in a paper are in the introduction. The purpose of the research should be clearly stated in this section.

The sample paper's introduction links television watching to increased energy intake and obesity, notes that several studies have shown a similar link with video gaming, and states no study was identified that compared television and video gaming. Eighteen of the thirty-one references used in the paper are cited in the introduction. The final paragraph of the introduction has two sentences that clearly state the purpose and the hypothesized expected outcome of the study.

The methods section clearly explains how the study was conducted. The ICMJE recommends that this section include information about how participants were selected, detailed demographics about who the participants were, and explanations of why any particular populations were included or excluded from the study. The details of how the study was conducted should be described with enough detail that the study could be replicated. Selected statistical methods should be reported in enough detail that readers can evaluate their appropriateness to the data being gathered.

The sample paper’s methods section includes subsections covering: recruitment; procedures used for each study subgroup (TV, VG, motion-controlled VG); what snacks and beverages were used and how they were made available; how energy intake and energy expenditure were measured; how the data was analyzed and the specific statistical analysis and secondary analysis that was used.

The results section reports the data gathered and the statistical analysis of the data. Tables and / or graphs are often used to clearly and compactly present the data.

The results section of the sample paper has two subsections and two tables. One subsection and related table shows the analysis of participant characteristics, The other subsection and table covers the analysis of energy intake, expenditure, and surplus.

In order to critically appraise the quality of the study you need to be able to understand the statistical analysis of the data. Two articles that help with this task are:

- Greenhalgh Trisha. How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests BMJ 1997; 315:364

- Greenhalgh Trisha. How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: “Significant” relations and their pitfalls BMJ 1997; 315:422

Another aid to critically reading a paper is to see if it has been included and evaluated in a systematic review. Try searching for the article you are reading in Google Scholar and seeing if the cited references include a systematic review. The sample paper was critically reviewed in:

- Marsh S, Ni Mhurchu C, Maddison R. The non-advertising effects of screen-based sedentary activities on acute eating behaviours in children, adolescents, and young adults. A systematic review. Appetite. 2013 Dec;71:259-73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.08.017. Epub 2013 Aug 31. PubMed Abstract . Full-text for UNC-CH .

The discussion section clearly states the primary findings of the study, poses explanations for the findings and any conclusions that can be drawn from them. It may also include the author’s assessment of limitations in the research as conducted and suggestions for further research that is needed.

The structure of biomedical research articles has been standardized across different journals at least in part due to the work of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. This group first published the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals in 1978.

The Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly work in Medical Journals (2013) is the most recent update of ICMJE's work.

- Next: Compare Types of Journals >>

- Last Updated: Aug 14, 2023 12:15 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/scholarly-articles

Search & Find

- E-Research by Discipline

- More Search & Find

Places & Spaces

- Places to Study

- Book a Study Room

- Printers, Scanners, & Computers

- More Places & Spaces

- Borrowing & Circulation

- Request a Title for Purchase

- Schedule Instruction Session

- More Services

Support & Guides

- Course Reserves

- Research Guides

- Citing & Writing

- More Support & Guides

- Mission Statement

- Diversity Statement

- Staff Directory

- Job Opportunities

- Give to the Libraries

- News & Exhibits

- Reckoning Initiative

- More About Us

- Search This Site

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

- Give Us Your Feedback

- 208 Raleigh Street CB #3916

- Chapel Hill, NC 27515-8890

- 919-962-1053

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

- Research Guides

Reading for Research: Social Sciences

Structure of a research article.

- Structural Read

Guide Acknowledgements

How to Read a Scholarly Article from the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University

Strategic Reading for Research from the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University

Bridging the Gap between Faculty Expectation and the Student Experience: Teaching Students toAnnotate and Synthesize Sources

Librarian for Sociology, Environmental Sociology, MHS and Public Policy Studies

Academic writing has features that vary only slightly across the different disciplines. Knowing these elements and the purpose of each serves help you to read and understand academic texts efficiently and effectively, and then apply what you read to your paper or project.

Social Science (and Science) original research articles generally follow IMRD: Introduction- Methods-Results-Discussion

Introduction

- Introduces topic of article

- Presents the "Research Gap"/Statement of Problem article will address

- How research presented in the article will solve the problem presented in research gap.

- Literature Review. presenting and evaluating previous scholarship on a topic. Sometimes, this is separate section of the article.

Method & Results

- How research was done, including analysis and measurements.

- Sometimes labeled as "Research Design"

- What answers were found

- Interpretation of Results (What Does It Mean? Why is it important?)

- Implications for the Field, how the study contributes to the existing field of knowledge

- Suggestions for further research

- Sometimes called Conclusion

You might also see IBC: Introduction - Body - Conclusion

- Identify the subject

- State the thesis

- Describe why thesis is important to the field (this may be in the form of a literature review or general prose)

Body

- Presents Evidence/Counter Evidence

- Integrate other writings (i.e. evidence) to support argument

- Discuss why others may disagree (counter-evidence) and why argument is still valid

- Summary of argument

- Evaluation of argument by pointing out its implications and/or limitations

- Anticipate and address possible counter-claims

- Suggest future directions of research

- Next: Structural Read >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2024 10:44 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/readingforresearch

- SpringerLink shop

Structuring your manuscript

Once you have completed your experiments it is time write it up into a coherent and concise paper which tells the story of your research. Researchers are busy people and so it is imperative that research articles are quick and easy to read. For this reason papers generally follow a standard structure which allows readers to easily find the information they are looking for. In the next part of the course we will discuss the standard structure and what to include in each section.

Overview of IMRaD structure

IMRaD refers to the standard structure of the body of research manuscripts (after the Title and Abstract):

- I ntroduction

- M aterials and Methods

- D iscussion and Conclusions

Not all journals use these section titles in this order, but most published articles have a structure similar to IMRaD. This standard structure:

- Gives a logical flow to the content

- Makes journal manuscripts consistent and easy to read

- Provides a “map” so that readers can quickly find content of interest in any manuscript

- Reminds authors what content should be included in an article

Provides all content needed for the work to be replicated and reproduced Although the sections of the journal manuscript are published in the order: Title, Abstract, Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion, this is not the best order for writing the sections of a manuscript. One recommended strategy is to write your manuscript in the following order:

1. Materials and Methods

These can be written first, as you are doing your experiments and collecting the results.

3. Introduction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Write these sections next, once you have had a chance to analyse your results, have a sense of their impact and have decided on the journal you think best suits the work

7. Abstract

Write your Title and Abstract last as these are based on all the other sections.

Following this order will help you write a logical and consistent manuscript.

Use the different sections of a manuscript to ‘tell a story’ about your research and its implications.

Back │ Next

Reading a Scholarly Article

- Parts of a Scholarly Article

- How to Read a Scholarly Article

- Additional Library Tutorials This link opens in a new window

Need Help? Ask Us!

Sources consulted.

Anatomy of a Scholarly Article: NCSU Libraries . (2009, July 13). https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/scholarly-articles/

Evelyn, S. (2021). LibGuides: Evaluating Information: How to Read a Scholarly Article . https://libguides.brown.edu/evaluate/ Read

Rempel, H. (2021). LibGuides: FW 107: Orientation to Fisheries and Wildlife: 5. The Anatomy of a Scholarly Article . https://guides.library.oregonstate.edu/ c.php?g=286038&p=1905154

- Next: How to Read a Scholarly Article >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 12:42 PM

- URL: https://libguides.wku.edu/reading_scholarly_articles

How to Read an Academic Journal Article

- What Is in an Academic Journal

- Anatomy of a Journal Article

- How to Read an Article

Anatomy of a Primary/Original Journal Article

Nearly all primary source journal articles (reporting the results of authors' own research) in the sciences, and most in the social sciences, follow the standard format below. Arts and humanities articles are more variable in specific formats, but in general they are at least roughly similar; even if they are not divided and labeled in the same manner, they will address these same points:

Introduction – What question was asked? Methods – How was it answered? Results – What was the answer? Conclusion – What does the answer mean?

Knowing the structure of a typical article helps you quickly skim to find and focus on what you need at different stages in your research process, which can save you a lot of time and effort.

For an example, let's take a detailed look at this article on college students and sleep .

Journal Title - The title of the journal that published the article, as well as the volume and issue number and date of publication.

Article Title and Authors - The title is usually a concise statement of the topic of the article, and often contains key technical or specific terms. The authors' institutional affiliations are often listed, sometimes including contact information.

Article Info - There is often a section saying when the article was initially submitted, then resubmitted and accepted after revisions. Sometimes it includes a list of keywords the author selected to describe the article and make it findable via search engines.

Abstract - A brief summation of the article, usually including the purpose of the study, main findings, conclusions, and significance of the results.

Introduction - Overview of the contents of the article, explaining the purpose of the study (e.g., the hypothesis being tested, or the question the study seeks to answer) and putting it in context of other research done. Often this will include a literature review - a summary of other work done on the topic, to which this article is adding new findings - but sometimes a literature review is in a section of its own.

Methods - The specific methodologies – study design, procedures, measurement instruments, data collection, etc. – used to conduct the study.

Results - Detailed outcomes of the study, often including charts, graphs, or tables of data.

Discussion of results – Analysis and interpretation of the results, explaining what conclusions can be drawn (e.g., was the hypothesis confirmed, or were the study’s questions answered). This section also places the results in the wider research context outlined in the introduction, and addresses implications for future research.

Limitations and Questions - This could be integrated into the Discussion or Conclusion, a subsection of Discussion (as in this example) or Conclusion, or a separate section. This addresses what the results do not and cannot say, and points to remaining questions unanswered or new questions raised by the findings.

Conclusion - A concise summary of the main findings and significance of the study.

References - A list of all the publications and other sources cited in the article.

Acknowledgments, Appendices, etc. - More recent articles usually disclose sources of funding or possible conflicts of interest (funding or affiliations that may influence the author’s interpretations). Some related data, images, etc., may be included in an appendix.

- << Previous: What Is in an Academic Journal

- Next: How to Read an Article >>

- Last Updated: Oct 27, 2023 11:59 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/readanarticle

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2024

Systematic review on the frequency and quality of reporting patient and public involvement in patient safety research

- Sahar Hammoud ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4682-9001 1 ,

- Laith Alsabek 1 , 2 ,

- Lisa Rogers 1 &

- Eilish McAuliffe 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 532 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

212 Accesses

Metrics details

In recent years, patient and public involvement (PPI) in research has significantly increased; however, the reporting of PPI remains poor. The Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) was developed to enhance the quality and consistency of PPI reporting. The objective of this systematic review is to identify the frequency and quality of PPI reporting in patient safety (PS) research using the GRIPP2 checklist.

Searches were performed in Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL from 2018 to December, 2023. Studies on PPI in PS research were included. We included empirical qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, and case studies. Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals in English were included. The quality of PPI reporting was assessed using the short form of the (GRIPP2-SF) checklist.

A total of 8561 studies were retrieved from database searches, updates, and reference checks, of which 82 met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review. Major PS topics were related to medication safety, general PS, and fall prevention. Patient representatives, advocates, patient advisory groups, patients, service users, and health consumers were the most involved. The main involvement across the studies was in commenting on or developing research materials. Only 6.1% ( n = 5) of the studies reported PPI as per the GRIPP2 checklist. Regarding the quality of reporting following the GRIPP2-SF criteria, our findings show sub-optimal reporting mainly due to failures in: critically reflecting on PPI in the study; reporting the aim of PPI in the study; and reporting the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall.

Conclusions

Our review shows a low frequency of PPI reporting in PS research using the GRIPP2 checklist. Furthermore, it reveals a sub-optimal quality in PPI reporting following GRIPP2-SF items. Researchers, funders, publishers, and journals need to promote consistent and transparent PPI reporting following internationally developed reporting guidelines such as the GRIPP2. Evidence-based guidelines for reporting PPI should be encouraged and supported as it helps future researchers to plan and report PPI more effectively.

Trial registration

The review protocol is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023450715).

Peer Review reports

Patient safety (PS) is defined as “the absence of preventable harm to a patient and reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with healthcare to an acceptable minimum” [ 1 ]. It is estimated that one in 10 patients are harmed in healthcare settings due to unsafe care, resulting in over three million deaths annually [ 2 ]. More than 50% of adverse events are preventable, and half of these events are related to medications [ 3 , 4 ]. There are various types of adverse events that patients can experience such as medication errors, patient falls, healthcare-associated infections, diagnostic errors, pressure ulcers, unsafe surgical procedures, patient misidentification, and others [ 1 ].

Over the last few decades, the approach of PS management has shifted toward actively involving patients and their families in managing PS. This innovative approach has surpassed the traditional model where healthcare providers were the sole managers of PS [ 5 ]. Recent research has shown that patients have a vital role in promoting their safety and decreasing the occurrence of adverse events [ 6 ]. Hence, there is a growing recognition of patient and family involvement as a promising method to enhance PS [ 7 ]. This approach includes involving patients in PS policy development, research, and shared decision making [ 1 ].

In the last decade, research involving patients and the public has significantly increased. In the United Kingdom (U.K), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has played a critical role in providing strategic and infrastructure support to integrate Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) throughout publicly funded research [ 8 ]. This has established a context where PPI is recognised as an essential element in research [ 9 ]. In Ireland, the national government agency responsible for the management and delivery of all public health and social services; the National Health Service Executive (HSE) emphasise the importance of PPI in research and provide guidance for researchers on how to involve patients and public in all parts of the research cycle and knowledge translation process [ 10 ]. Similar initiatives are also developing among other European countries, North America, and Australia. However, despite this significant expansion of PPI research, the reporting of PPI in research articles continues to be sub-optimal, inconsistent, and lacks essential information on the context, process, and impact of PPI [ 9 ]. To address this problem, the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP) was developed in 2011 following the EQUATOR methodology to enhance the quality, consistency, and transparency of PPI reporting. Additionally, to provide guidance for researchers, patients, and the public to advance the quality of the international PPI evidence-base [ 11 ]. The first GRIPP checklist was a significant start in producing higher-quality PPI reporting; however, it was developed following a systematic review, and did not include any input from the international PPI research community. Given the importance of reaching consensus in generating current reporting guidelines, a second version of the GRIPP checklist (GRIPP2) was developed to tackle this problem by involving the international PPI community in its development [ 9 ]. There are two versions of the GRIPP2 checklist, a long form (GRIPP2-LF) for studies with PPI as the primary focus, and a short form (GRIPP2-SF) for studies with PPI as secondary or tertiary focus.

Since the publication of the GRIPP2 checklist, several systematic reviews have been conducted to assess the quality of PPI reporting on various topics. For instance, Bergin et al. in their review to investigate the nature and impact of PPI in cancer research, reported a sub-optimal quality of PPI reporting using the GRIPP2-SF, mainly due to failure to address PPI challenges [ 12 ]. Similarly, Owyang et al. in their systematic review to assess the prevalence, extent, and quality of PPI in orthopaedic practice, described a poor PPI reporting following the GRIPP2-SF checklist criteria [ 13 ]. While a few systematic reviews have been conducted to assess theories, strategies, types of interventions, and barriers and enablers of PPI in PS [ 5 , 14 , 15 , 16 ], no previous review has assessed the quality of PPI reporting in PS research. Thus, our systematic review aims to address this knowledge gap. The objective of this review is to identify the frequency PPI reporting in PS research using the GRIPP2 checklist from 2018 (the year after GRIPP2 was published) and the quality of reporting following the GRIPP2-SF. The GRIPP2 checklist was chosen as the benchmark as it is the first international, evidence-based, community consensus informed guideline for the reporting of PPI in research and more specifically in health and social care research [ 9 ]. Additionally, it is the most recent report-focused framework and the most recommended by several leading journals [ 17 ].

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to plan and report this review [ 18 ]. The review protocol was published on PROSPERO the International Database of Prospectively Registered Systematic Reviews in August 2023 (CRD42023450715).

Search strategy

For this review, we used the PICo framework to define the key elements in our research. These included articles on patients and public (P-Population) involvement (I- phenomenon of Interest) in PS (C-context). Details are presented in Table 1 . Four databases were searched including Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL to identify papers on PPI in PS research. A systematic search strategy was initially developed using MEDLINE. MeSH terms and keywords relevant to specific categories (e.g., patient safety) were combined using the “OR” Boolean term (i.e. patient safety OR adverse event OR medical error OR surgical error) and categories were then combined using the “AND” Boolean term. (i.e. “patient and public involvement” AND “patient safety”). The search strategy was adapted for the other three databases. Full search strategies are provided in Supplementary file 1 . The search was conducted on July 27th, 2023, and was limited to papers published from 2018. As the GRIPP2 tool was published in 2017, this limit ensured the retrieval of relevant studies. An alert system was set on the four databases to receive all new published studies until December 2023, prior to the final analysis. The search was conducted without restrictions on study type, research design, and language. To reduce selection bias, hand searching was carried out on the reference lists of all the eligible articles in the later stages of the review. This was done by the first author. The search strategy was developed by the first author and confirmed by the research team and a Librarian. The database search was conducted by the first author.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies on PPI in PS research with a focus on health/healthcare were included in this review. We defined PPI as active involvement which is in line with the NIHR INVOLVE definition as “research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them” [ 19 ]. This includes any PPI including, being a co-applicant on a research project or grant application, identifying research priorities, being a member of an advisory or steering group, participating in developing research materials or giving feedback on them, conducting interviews with study participants, participating in recruitment, data collection, data analysis, drafting manuscripts and/or dissemination of results. Accordingly, we excluded studies where patients or the public were only involved as research participants.

We defined patients and public to include patients, relatives, carers, caregivers and community, which is also in line with the NIHR PPI involvement in National Health Service [ 19 ].

Patient safety included topics on medication safety, adverse events, communication, safety culture, diagnostic errors, and others. A full list of the used terms for PPI and PS is provided in Supplementary file 1 . Regarding the research type and design, we included empirical qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, and case studies. Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals and in English were included.

Any article that did not meet the inclusion criteria was excluded. Studies not reporting outcomes were excluded. Furthermore, review papers, conference abstracts, letters to editor, commentary, viewpoints, and short communications were excluded. Finally, papers published prior to 2018 were excluded.

Study selection

The selection of eligible studies was done by the first and the second authors independently, starting with title and abstracts screening to eliminate papers that failed to meet our inclusion criteria. Then, full text screening was conducted to decide on the final included papers in this review. Covidence, an online data management system supported the review process, ensuring reviewers were blinded to each other’s decisions. Disagreements between reviewers were discussed first, in cases where the disagreement was not resolved, the fourth author was consulted.

Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction sheet was developed using excel then piloted, discussed with the research team and modified as appropriate. The following data were extracted: citation and year of publication, objective of the study, country, PS topic, design, setting, PPI participants, PPI stages (identifying research priorities, being a member of an advisory or steering group, etc.…), frequency of PPI reporting as per the GRIPP2 checklist, and the availability of a plain language summary. Additionally, data against the five items of GRIPP2-SF (aim of PPI in the study, methods used for PPI, outcomes of PPI including the results and the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall, and reflections on PPI) were extracted. To avoid multiple publication bias and missing outcomes, data extraction was done by the first and the second authors independently and then compared. Disagreements between reviewers were first discussed, and then resolved by the third and fourth authors if needed.

Quality assessment

The quality of PPI reporting was assessed using GRIPP2-SF developed by Staniszewska et al. [ 9 ] as it is developed to improve the quality, consistency, and reporting of PPI in social and healthcare research. Additionally the GRIPP2-SF is suitable for all studies regardless of whether PPI is the primary, secondary, or tertiary focus, whereas the GRIPP2-LF is not suitable for studies where PPI serves as a secondary or tertiary focus. The checklist includes five items (mentioned above) that authors should include in their studies. It is important to mention that Staniszewska et al. noted that “while GRIPP2-SF aims to guide consistent reporting, it is not possible to be prescriptive about the exact content of each item, as the current evidence-base is not advanced enough to make this possible” ([ 9 ] p5). For that reason, we had to develop criteria for scoring the five reporting items. We used three scoring as Yes, No, and partial for each of the five items of the GRIPP2-SF. Yes, was given when authors presented PPI information on the item clearly in the paper. No, when no information was provided, and partial when the information partially met the item requirement. For example, as per GRIPP2-SF authors should provide a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study. In the example given by Staniszewska et al., information on patient/public partners and how many of them were provided, as well as the stages of the study they were involved in (i.e. refining the focus of the research questions, developing the search strategy, interpreting results). Thus, in our evaluation of the included studies, we gave a yes if information on PPI participants (i.e. patient partners, community partners, or family members etc..) and how many of them were involved was provided, and information on the stages or actions of their involvement in the study was provided. However, we gave a “partial” if information was not fully provided (i.e. information on patient/public partners and how many were involved in the study without describing in what stages or actions they were involved, and vice versa), and a “No” if no information was presented at all.

The quality of PPI reporting was done by the first and the second authors independently and then compared. Disagreements between reviewers were first discussed, and then resolved by the third and fourth author when needed.

Assessing the quality or risk of bias of the included studies was omitted, as the focus in this review was on appraising the quality of PPI reporting rather than assessing the quality of each research article.

Data synthesis

After data extraction, a table summarising the included studies was developed. Studies were compared according to the main outcomes of the review; frequency of PPI reporting following the GRIPP2 checklist and the quality of reporting as per GRIPP2-SF five items, and the availability of a plain language summary.

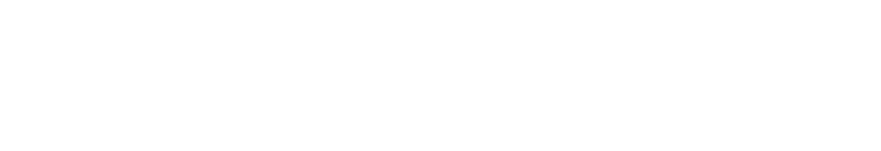

Search results and study selection

The database searches yielded a total of 8491 studies. First, 2496 were removed as duplicates. Then, after title and abstract screening, 5785 articles were excluded leaving 210 articles eligible for the full text review. After a careful examination, 68 of these studies were included in this review. A further 38 studies were identified from the alert system that was set on the four databases and 32 studies from the reference check of the included studies. Of these 70 articles, 56 were further excluded and 14 were added to the previous 68 included studies. Thus, 82 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. A summary of the database search results and the study selection process are presented in Fig. 1 .

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. The PRISMA flow diagram details the review search results and selection process

Overview of included studies

Details of the study characteristics including first author and year of publication, objective, country, study design, setting, PS topic, PPI participants and involvement stages are presented in Supplementary file 2 . The majority of the studies were conducted in the U.K ( n = 24) and the United States of America ( n = 18), with the remaining 39 conducted in other high income countries, the exception being one study in Haiti. A range of study designs were identified, the most common being qualitative ( n = 31), mixed methods ( n = 13), interventional ( n = 5), and quality improvement projects ( n = 4). Most PS topics concerned medication safety ( n = 17), PS in general (e.g., developing a PS survey or PS management application) ( n = 14), fall prevention ( n = 13), communication ( n = 11), and adverse events ( n = 10), with the remaining PS topics listed in Supplementary file 2 .

Patient representatives, advocates, and patient advisory groups ( n = 33) and patients, service users, and health consumers ( n = 32) were the main groups involved. The remaining, included community members/ organisations. Concerning PPI stages, the main involvement across the studies was in commenting on or developing research materials ( n = 74) including, patient leaflets, interventional tools, mobile applications, and survey instruments. Following this stage, involvement in data analysis, drafting manuscripts, and disseminating results ( n = 30), and being a member of a project advisory or steering group ( n = 18) were the most common PPI evident in included studies. Whereas the least involvement was in identifying research priorities ( n = 5), and being a co-applicant on a research project or grant application ( n = 6).

Regarding plain language summary, only one out of the 82 studies (1.22%) provided a plain language summary in their paper [ 20 ].

Frequency and quality of PPI reporting

The frequency of PPI reporting following the GRIPP2 checklist was 6.1%, where only five of the 82 included studies reported PPI in their papers following the GRIPP2 checklist. The quality of PPI reporting in those studies is presented in Table 2 . Of these five studies, one study (20%) did not report the aim of PPI in the study and one (20%) did not comment on the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall.

The quality of PPI reporting of the remaining 77 studies is presented in Table 3 . The aim of PPI in the study was reported in 62.3% of articles ( n = 48), while 3.9% ( n = 3) partially reported this. A clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study was reported in 79.2% of papers ( n = 61) and partially in 20.8% ( n = 16). Concerning the outcomes, 81.8% of papers ( n = 63) reported the results of PPI in the study, while 10.4% ( n = 8) partially did. Of the 77 studies, 68.8% ( n = 53) reported the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall and 3.9% ( n = 3) partially reported this. Finally, 57.1% ( n = 44) of papers critically reflected on the things that went well and those that did not and 2.6% ( n = 2) partially reflected on this.

Summary of main findings

This systematic review assessed the frequency of reporting PPI in PS research using the GRIPP2 checklist and quality of reporting using the GRIPP2-SF. In total, 82 studies were included in this review. Major PS topics were related to medication safety, general PS, and fall prevention. Patient representatives, advocates, patient advisory groups, patients, service users, and health consumers were the most involved. The main involvement across the studies was in commenting on or developing research materials such as educational and interventional tools, survey instruments, and applications while the least was in identifying research priorities and being a co-applicant on a research project or grant application. Thus, significant effort is still needed to involve patients and the public in the earlier stages of the research process given the fundamental impact of PS on their lives.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A low frequency of reporting PPI in PS research following the GRIPP2 guidelines was revealed in this review, where only five of the 82 studies included mentioned that PPI was reported as per the GRIPP2 checklist. This is despite it being the most recent report-focused framework and the most recommended by several leading journals [ 17 ]. This was not surprising as similar results were reported in recent reviews in other healthcare topics. For instance, Musbahi et al. in their systematic review on PPI reporting in bariatric research reported that none of the 90 papers identified in their review mentioned or utilised the GRIPP2 checklist [ 102 ]. Similarly, a study on PPI in orthodontic research found that none of the 363 included articles reported PPI against the GRIPP2 checklist [ 103 ].

In relation to the quality of reporting following the GRIPP2-SF criteria, our findings show sub-optimal reporting within the 77 studies that did not use GRIPP2 as a guide/checklist to report their PPI. Similarly, Bergin et al. in their systematic review to investigate the nature and impact of PPI in cancer research concluded that substandard reporting was evident [ 12 ]. In our review, this was mainly due to failure to meet three criteria. First, the lowest percentage of reporting (57.1%, n = 44) was related to critical reflection on PPI in the study (i.e., what went well and what did not). In total, 31 studies (42.9%) did not provide any information on this, and two studies were scored as partial. The first study mentioned that only involving one patient was a limitation [ 27 ] and the other stated that including three patients in the design of the tool was a strength [ 83 ]. Both studies did not critically comment or reflect on these points so that future researchers are able to avoid such problems and enhance PPI opportunities. For instance, providing the reasons/challenges behind the exclusive inclusion of a single patient and explaining how this limits the study findings and conclusion would help future researchers to address these challenges. Likewise, commenting on why incorporating three patients in the design of the study tool could be seen as a strength would have been beneficial. This could be, fostering diverse perspectives and generating novel ideas for developing the tool. Similar to our findings, Bergin et al. in their systematic review reported that 40% of the studies failed to meet this criterion [ 12 ].

Second, only 48 out of 77 articles (62.3%) reported the aim of PPI in their study, which is unlike the results of Bergin et al. where most of the studies (93.1%) in their review met this criterion [ 12 ]. Of the 29 studies which did not meet this criterion in our review, few mentioned in their objective developing a consensus-based instrument [ 41 ], reaching a consensus on the patient-reported outcomes [ 32 ], obtaining international consensus on a set of core outcome measures [ 98 ], and facilitating a multi-stakeholder dialogue [ 71 ] yet, without indicating anything in relation to patients, patient representatives, community members, or any other PPI participants. Thus, the lack of reporting the aim of PPI was clearly evident in this review. Reporting the aim of PPI in the study is crucial for promoting transparency, methodological rigor, reproducibility, and impact assessment of the PPI.

Third, 68.8% ( n = 53) of the studies reported the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall including positive and negative effects if any. This was again similar to the findings of Bergin et al., where 38% of the studies did not meet this criterion mainly due to a failure to address PPI challenges in their respective studies [ 12 ]. Additionally, Owyang et al. in their review on the extent, and quality of PPI in orthopaedic practice, also described a poor reporting of PPI impact on research [ 13 ]. As per the GRIPP2 guidelines, both positive and negative effects of PPI on the study should be reported when applicable. Providing such information is essential as it enhances future research on PPI in terms of both practice and reporting.

Reporting a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study was acceptable, with 79.2% of the papers meeting this criterion. Most studies provided information in the methods section of their papers on the PPI participants, their number, stages of their involvement and how they were involved. Providing clear information on the methods used for PPI is vital to give the reader a clear understanding of the steps taken to involve patients, and for other researchers to replicate these methods in future research. Additionally, reporting the results of PPI in the study was also acceptable with 81.8% of the papers reporting the outcomes of PPI in the results section. Reporting the results of PPI is important for enhancing methodological transparency, providing a more accurate interpretation for the study findings, contributing to the overall accountability and credibility of the research, and informing decision making.

Out of the 82 studies included in this review, only one study provided a plain language summary. We understand that PS research or health and medical research in general is difficult for patients and the public to understand given their diverse health literacy and educational backgrounds. However, if we expect patients and the public to be involved in research then, it is crucial to translate this research that has a huge impact on their lives into an easily accessible format. Failing to translate the benefits that such research may have on patient and public lives may result in them underestimating the value of this research and losing interest in being involved in the planning or implementation of future research [ 103 ]. Thus, providing a plain language summary for research is one way to tackle this problem. To our knowledge, only a few health and social care journals (i.e. Cochrane and BMC Research Involvement and Engagement) necessitate a plain language summary as a submission requirement. Having this as a requirement for submission is crucial in bringing the importance of this issue to researchers’ attention.