Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Covid19

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

11 min read

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

200+ Persuasive Essay Topics to Help You Out

Learn How to Create a Persuasive Essay Outline

30+ Free Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

Crafting a Convincing Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Learn to Write Persuasive Essay About Business With Examples and Tips

Check Out 12 Persuasive Essay About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you looking to write a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic?

Writing a compelling and informative essay about this global crisis can be challenging. It requires researching the latest information, understanding the facts, and presenting your argument persuasively.

But don’t worry! with some guidance from experts, you’ll be able to write an effective and persuasive essay about Covid-19.

In this blog post, we’ll outline the basics of writing a persuasive essay . We’ll provide clear examples, helpful tips, and essential information for crafting your own persuasive piece on Covid-19.

Read on to get started on your essay.

- 1. Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 2. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

- 3. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

- 4. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

- 5. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

- 6. Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

- 7. Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 8. Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Here are the steps to help you write a persuasive essay on this topic, along with an example essay:

Step 1: Choose a Specific Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement should clearly state your position on a specific aspect of COVID-19. It should be debatable and clear. For example:

Step 2: Research and Gather Information

Collect reliable and up-to-date information from reputable sources to support your thesis statement. This may include statistics, expert opinions, and scientific studies. For instance:

- COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness data

- Information on vaccine mandates in different countries

- Expert statements from health organizations like the WHO or CDC

Step 3: Outline Your Essay

Create a clear and organized outline to structure your essay. A persuasive essay typically follows this structure:

- Introduction

- Background Information

- Body Paragraphs (with supporting evidence)

- Counterarguments (addressing opposing views)

Step 4: Write the Introduction

In the introduction, grab your reader's attention and present your thesis statement. For example:

Step 5: Provide Background Information

Offer context and background information to help your readers understand the issue better. For instance:

Step 6: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should present a single point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis statement. Use clear topic sentences, evidence, and analysis. Here's an example:

Step 7: Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and refute them with strong counterarguments. This demonstrates that you've considered different perspectives. For example:

Step 8: Write the Conclusion

Summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement in the conclusion. End with a strong call to action or thought-provoking statement. For instance:

Step 9: Revise and Proofread

Edit your essay for clarity, coherence, grammar, and spelling errors. Ensure that your argument flows logically.

Step 10: Cite Your Sources

Include proper citations and a bibliography page to give credit to your sources.

Remember to adjust your approach and arguments based on your target audience and the specific angle you want to take in your persuasive essay about COVID-19.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

When writing a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s important to consider how you want to present your argument. To help you get started, here are some example essays for you to read:

Check out some more PDF examples below:

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Pandemic

Sample Of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 In The Philippines - Example

If you're in search of a compelling persuasive essay on business, don't miss out on our “ persuasive essay about business ” blog!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

Covid19 vaccines are one of the ways to prevent the spread of Covid-19, but they have been a source of controversy. Different sides argue about the benefits or dangers of the new vaccines. Whatever your point of view is, writing a persuasive essay about it is a good way of organizing your thoughts and persuading others.

A persuasive essay about the Covid-19 vaccine could consider the benefits of getting vaccinated as well as the potential side effects.

Below are some examples of persuasive essays on getting vaccinated for Covid-19.

Covid19 Vaccine Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay on Covid Vaccines

Interested in thought-provoking discussions on abortion? Read our persuasive essay about abortion blog to eplore arguments!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

Covid19 has drastically changed the way people interact in schools, markets, and workplaces. In short, it has affected all aspects of life. However, people have started to learn to live with Covid19.

Writing a persuasive essay about it shouldn't be stressful. Read the sample essay below to get idea for your own essay about Covid19 integration.

Persuasive Essay About Working From Home During Covid19

Searching for the topic of Online Education? Our persuasive essay about online education is a must-read.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

Covid-19 has been an ever-evolving issue, with new developments and discoveries being made on a daily basis.

Writing an argumentative essay about such an issue is both interesting and challenging. It allows you to evaluate different aspects of the pandemic, as well as consider potential solutions.

Here are some examples of argumentative essays on Covid19.

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 Sample

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 With Introduction Body and Conclusion

Looking for a persuasive take on the topic of smoking? You'll find it all related arguments in out Persuasive Essay About Smoking blog!

Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

Do you need to prepare a speech about Covid19 and need examples? We have them for you!

Persuasive speeches about Covid-19 can provide the audience with valuable insights on how to best handle the pandemic. They can be used to advocate for specific changes in policies or simply raise awareness about the virus.

Check out some examples of persuasive speeches on Covid-19:

Persuasive Speech About Covid-19 Example

Persuasive Speech About Vaccine For Covid-19

You can also read persuasive essay examples on other topics to master your persuasive techniques!

Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19 requires a thoughtful approach to present your arguments effectively.

Here are some tips to help you craft a compelling persuasive essay on this topic:

Choose a Specific Angle

Start by narrowing down your focus. COVID-19 is a broad topic, so selecting a specific aspect or issue related to it will make your essay more persuasive and manageable. For example, you could focus on vaccination, public health measures, the economic impact, or misinformation.

Provide Credible Sources

Support your arguments with credible sources such as scientific studies, government reports, and reputable news outlets. Reliable sources enhance the credibility of your essay.

Use Persuasive Language

Employ persuasive techniques, such as ethos (establishing credibility), pathos (appealing to emotions), and logos (using logic and evidence). Use vivid examples and anecdotes to make your points relatable.

Organize Your Essay

Structure your essay involves creating a persuasive essay outline and establishing a logical flow from one point to the next. Each paragraph should focus on a single point, and transitions between paragraphs should be smooth and logical.

Emphasize Benefits

Highlight the benefits of your proposed actions or viewpoints. Explain how your suggestions can improve public health, safety, or well-being. Make it clear why your audience should support your position.

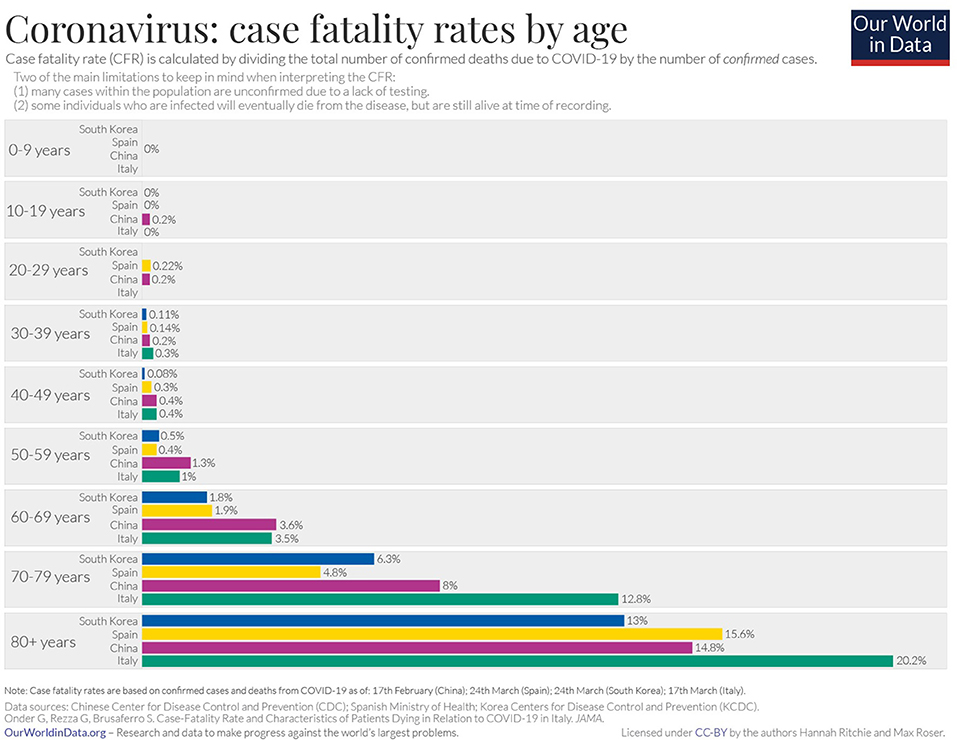

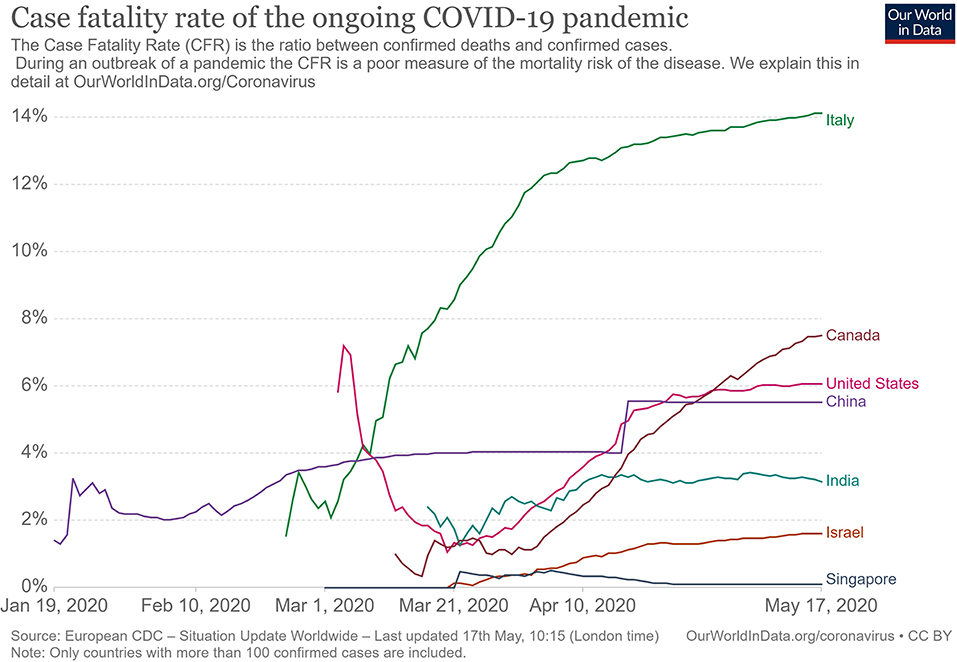

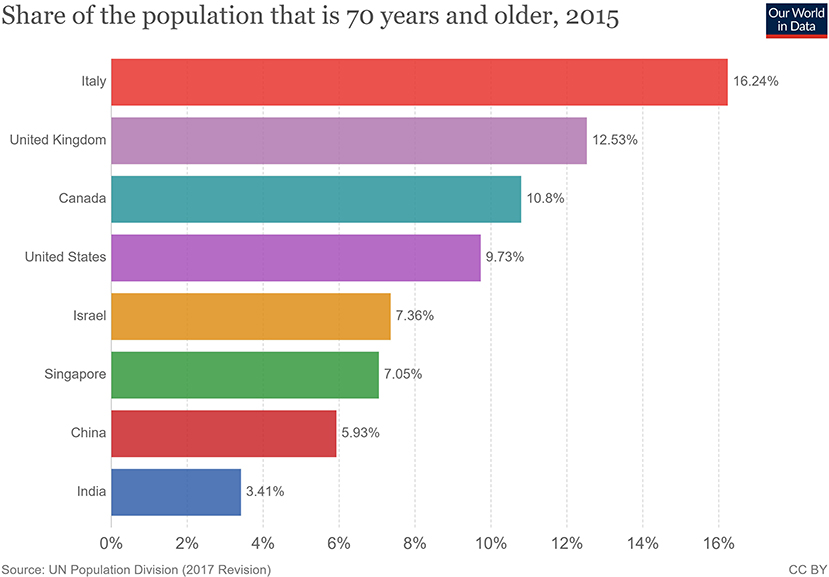

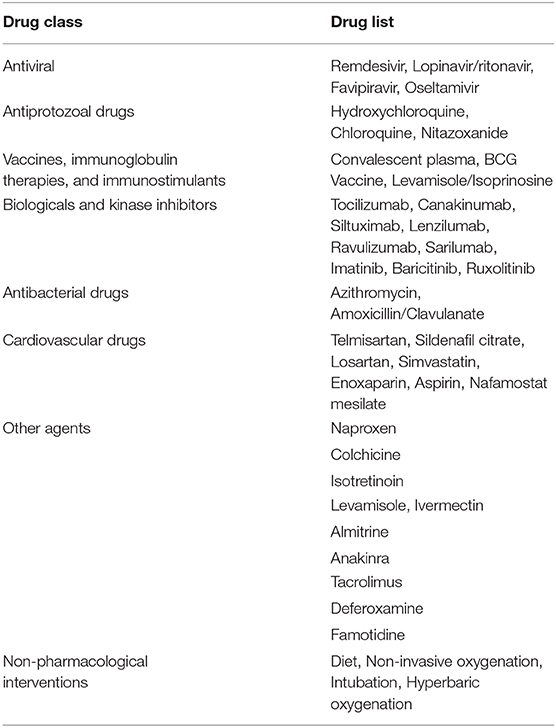

Use Visuals -H3

Incorporate graphs, charts, and statistics when applicable. Visual aids can reinforce your arguments and make complex data more accessible to your readers.

Call to Action

End your essay with a strong call to action. Encourage your readers to take a specific step or consider your viewpoint. Make it clear what you want them to do or think after reading your essay.

Revise and Edit

Proofread your essay for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Make sure your arguments are well-structured and that your writing flows smoothly.

Seek Feedback

Have someone else read your essay to get feedback. They may offer valuable insights and help you identify areas where your persuasive techniques can be improved.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Here are some persuasive essay topics on COVID-19:

- The Importance of Vaccination Mandates for COVID-19 Control

- Balancing Public Health and Personal Freedom During a Pandemic

- The Economic Impact of Lockdowns vs. Public Health Benefits

- The Role of Misinformation in Fueling Vaccine Hesitancy

- Remote Learning vs. In-Person Education: What's Best for Students?

- The Ethics of Vaccine Distribution: Prioritizing Vulnerable Populations

- The Mental Health Crisis Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems

- Global Cooperation vs. Vaccine Nationalism in Fighting the Pandemic

- The Future of Telemedicine: Expanding Healthcare Access Post-COVID-19

In search of more inspiring topics for your next persuasive essay? Our persuasive essay topics blog has plenty of ideas!

To sum it up,

You have read good sample essays and got some helpful tips. You now have the tools you needed to write a persuasive essay about Covid-19. So don't let the doubts stop you, start writing!

If you need professional writing help, don't worry! We've got that for you as well.

MyPerfectWords.com is a professional persuasive essay writing service that can help you craft an excellent persuasive essay on Covid-19. Our experienced essay writer will create a well-structured, insightful paper in no time!

So don't hesitate and place your ' write my essay online ' request today!

Frequently Asked Questions

Are there any ethical considerations when writing a persuasive essay about covid-19.

Yes, there are ethical considerations when writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19. It's essential to ensure the information is accurate, not contribute to misinformation, and be sensitive to the pandemic's impact on individuals and communities. Additionally, respecting diverse viewpoints and emphasizing public health benefits can promote ethical communication.

What impact does COVID-19 have on society?

The impact of COVID-19 on society is far-reaching. It has led to job and economic losses, an increase in stress and mental health disorders, and changes in education systems. It has also had a negative effect on social interactions, as people have been asked to limit their contact with others.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Federal vs. private parent student loans.

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

14 Colleges With Great Food Options

Sarah Wood May 8, 2024

Colleges With Religious Affiliations

Anayat Durrani May 8, 2024

Protests Threaten Campus Graduations

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 6, 2024

Protesting on Campus: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 6, 2024

Lawmakers Ramp Up Response to Unrest

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 3, 2024

University Commencements Must Go On

Eric J. Gertler May 3, 2024

Where Astronauts Went to College

Cole Claybourn May 3, 2024

College Admitted Student Days

Jarek Rutz May 3, 2024

Universities, the Police and Protests

John J. Sloan III May 2, 2024

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

8 Lessons We Can Learn From the COVID-19 Pandemic

BY KATHY KATELLA May 14, 2021

Note: Information in this article was accurate at the time of original publication. Because information about COVID-19 changes rapidly, we encourage you to visit the websites of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and your state and local government for the latest information.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed life as we know it—and it may have changed us individually as well, from our morning routines to our life goals and priorities. Many say the world has changed forever. But this coming year, if the vaccines drive down infections and variants are kept at bay, life could return to some form of normal. At that point, what will we glean from the past year? Are there silver linings or lessons learned?

“Humanity's memory is short, and what is not ever-present fades quickly,” says Manisha Juthani, MD , a Yale Medicine infectious diseases specialist. The bubonic plague, for example, ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages—resurfacing again and again—but once it was under control, people started to forget about it, she says. “So, I would say one major lesson from a public health or infectious disease perspective is that it’s important to remember and recognize our history. This is a period we must remember.”

We asked our Yale Medicine experts to weigh in on what they think are lessons worth remembering, including those that might help us survive a future virus or nurture a resilience that could help with life in general.

Lesson 1: Masks are useful tools

What happened: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) relaxed its masking guidance for those who have been fully vaccinated. But when the pandemic began, it necessitated a global effort to ensure that everyone practiced behaviors to keep themselves healthy and safe—and keep others healthy as well. This included the widespread wearing of masks indoors and outside.

What we’ve learned: Not everyone practiced preventive measures such as mask wearing, maintaining a 6-foot distance, and washing hands frequently. But, Dr. Juthani says, “I do think many people have learned a whole lot about respiratory pathogens and viruses, and how they spread from one person to another, and that sort of old-school common sense—you know, if you don’t feel well—whether it’s COVID-19 or not—you don’t go to the party. You stay home.”

Masks are a case in point. They are a key COVID-19 prevention strategy because they provide a barrier that can keep respiratory droplets from spreading. Mask-wearing became more common across East Asia after the 2003 SARS outbreak in that part of the world. “There are many East Asian cultures where the practice is still that if you have a cold or a runny nose, you put on a mask,” Dr. Juthani says.

She hopes attitudes in the U.S. will shift in that direction after COVID-19. “I have heard from a number of people who are amazed that we've had no flu this year—and they know masks are one of the reasons,” she says. “They’ve told me, ‘When the winter comes around, if I'm going out to the grocery store, I may just put on a mask.’”

Lesson 2: Telehealth might become the new normal

What happened: Doctors and patients who have used telehealth (technology that allows them to conduct medical care remotely), found it can work well for certain appointments, ranging from cardiology check-ups to therapy for a mental health condition. Many patients who needed a medical test have also discovered it may be possible to substitute a home version.

What we’ve learned: While there are still problems for which you need to see a doctor in person, the pandemic introduced a new urgency to what had been a gradual switchover to platforms like Zoom for remote patient visits.

More doctors also encouraged patients to track their blood pressure at home , and to use at-home equipment for such purposes as diagnosing sleep apnea and even testing for colon cancer . Doctors also can fine-tune cochlear implants remotely .

“It happened very quickly,” says Sharon Stoll, DO, a neurologist. One group that has benefitted is patients who live far away, sometimes in other parts of the country—or even the world, she says. “I always like to see my patients at least twice a year. Now, we can see each other in person once a year, and if issues come up, we can schedule a telehealth visit in-between,” Dr. Stoll says. “This way I may hear about an issue before it becomes a problem, because my patients have easier access to me, and I have easier access to them.”

Meanwhile, insurers are becoming more likely to cover telehealth, Dr. Stoll adds. “That is a silver lining that will hopefully continue.”

Lesson 3: Vaccines are powerful tools

What happened: Given the recent positive results from vaccine trials, once again vaccines are proving to be powerful for preventing disease.

What we’ve learned: Vaccines really are worth getting, says Dr. Stoll, who had COVID-19 and experienced lingering symptoms, including chronic headaches . “I have lots of conversations—and sometimes arguments—with people about vaccines,” she says. Some don’t like the idea of side effects. “I had vaccine side effects and I’ve had COVID-19 side effects, and I say nothing compares to the actual illness. Unfortunately, I speak from experience.”

Dr. Juthani hopes the COVID-19 vaccine spotlight will motivate people to keep up with all of their vaccines, including childhood and adult vaccines for such diseases as measles , chicken pox, shingles , and other viruses. She says people have told her they got the flu vaccine this year after skipping it in previous years. (The CDC has reported distributing an exceptionally high number of doses this past season.)

But, she cautions that a vaccine is not a magic bullet—and points out that scientists can’t always produce one that works. “As advanced as science is, there have been multiple failed efforts to develop a vaccine against the HIV virus,” she says. “This time, we were lucky that we were able build on the strengths that we've learned from many other vaccine development strategies to develop multiple vaccines for COVID-19 .”

Lesson 4: Everyone is not treated equally, especially in a pandemic

What happened: COVID-19 magnified disparities that have long been an issue for a variety of people.

What we’ve learned: Racial and ethnic minority groups especially have had disproportionately higher rates of hospitalization for COVID-19 than non-Hispanic white people in every age group, and many other groups faced higher levels of risk or stress. These groups ranged from working mothers who also have primary responsibility for children, to people who have essential jobs, to those who live in rural areas where there is less access to health care.

“One thing that has been recognized is that when people were told to work from home, you needed to have a job that you could do in your house on a computer,” says Dr. Juthani. “Many people who were well off were able do that, but they still needed to have food, which requires grocery store workers and truck drivers. Nursing home residents still needed certified nursing assistants coming to work every day to care for them and to bathe them.”

As far as racial inequities, Dr. Juthani cites President Biden’s appointment of Yale Medicine’s Marcella Nunez-Smith, MD, MHS , as inaugural chair of a federal COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. “Hopefully the new focus is a first step,” Dr. Juthani says.

Lesson 5: We need to take mental health seriously

What happened: There was a rise in reported mental health problems that have been described as “a second pandemic,” highlighting mental health as an issue that needs to be addressed.

What we’ve learned: Arman Fesharaki-Zadeh, MD, PhD , a behavioral neurologist and neuropsychiatrist, believes the number of mental health disorders that were on the rise before the pandemic is surging as people grapple with such matters as juggling work and childcare, job loss, isolation, and losing a loved one to COVID-19.

The CDC reports that the percentage of adults who reported symptoms of anxiety of depression in the past 7 days increased from 36.4 to 41.5 % from August 2020 to February 2021. Other reports show that having COVID-19 may contribute, too, with its lingering or long COVID symptoms, which can include “foggy mind,” anxiety , depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder .

“We’re seeing these problems in our clinical setting very, very often,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “By virtue of necessity, we can no longer ignore this. We're seeing these folks, and we have to take them seriously.”

Lesson 6: We have the capacity for resilience

What happened: While everyone’s situation is different (and some people have experienced tremendous difficulties), many have seen that it’s possible to be resilient in a crisis.

What we’ve learned: People have practiced self-care in a multitude of ways during the pandemic as they were forced to adjust to new work schedules, change their gym routines, and cut back on socializing. Many started seeking out new strategies to counter the stress.

“I absolutely believe in the concept of resilience, because we have this effective reservoir inherent in all of us—be it the product of evolution, or our ancestors going through catastrophes, including wars, famines, and plagues,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think inherently, we have the means to deal with crisis. The fact that you and I are speaking right now is the result of our ancestors surviving hardship. I think resilience is part of our psyche. It's part of our DNA, essentially.”

Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh believes that even small changes are highly effective tools for creating resilience. The changes he suggests may sound like the same old advice: exercise more, eat healthy food, cut back on alcohol, start a meditation practice, keep up with friends and family. “But this is evidence-based advice—there has been research behind every one of these measures,” he says.

But we have to also be practical, he notes. “If you feel overwhelmed by doing too many things, you can set a modest goal with one new habit—it could be getting organized around your sleep. Once you’ve succeeded, move on to another one. Then you’re building momentum.”

Lesson 7: Community is essential—and technology is too

What happened: People who were part of a community during the pandemic realized the importance of human connection, and those who didn’t have that kind of support realized they need it.

What we’ve learned: Many of us have become aware of how much we need other people—many have managed to maintain their social connections, even if they had to use technology to keep in touch, Dr. Juthani says. “There's no doubt that it's not enough, but even that type of community has helped people.”

Even people who aren’t necessarily friends or family are important. Dr. Juthani recalled how she encouraged her mail carrier to sign up for the vaccine, soon learning that the woman’s mother and husband hadn’t gotten it either. “They are all vaccinated now,” Dr. Juthani says. “So, even by word of mouth, community is a way to make things happen.”

It’s important to note that some people are naturally introverted and may have enjoyed having more solitude when they were forced to stay at home—and they should feel comfortable with that, Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think one has to keep temperamental tendencies like this in mind.”

But loneliness has been found to suppress the immune system and be a precursor to some diseases, he adds. “Even for introverted folks, the smallest circle is preferable to no circle at all,” he says.

Lesson 8: Sometimes you need a dose of humility

What happened: Scientists and nonscientists alike learned that a virus can be more powerful than they are. This was evident in the way knowledge about the virus changed over time in the past year as scientific investigation of it evolved.

What we’ve learned: “As infectious disease doctors, we were resident experts at the beginning of the pandemic because we understand pathogens in general, and based on what we’ve seen in the past, we might say there are certain things that are likely to be true,” Dr. Juthani says. “But we’ve seen that we have to take these pathogens seriously. We know that COVID-19 is not the flu. All these strokes and clots, and the loss of smell and taste that have gone on for months are things that we could have never known or predicted. So, you have to have respect for the unknown and respect science, but also try to give scientists the benefit of the doubt,” she says.

“We have been doing the best we can with the knowledge we have, in the time that we have it,” Dr. Juthani says. “I think most of us have had to have the humility to sometimes say, ‘I don't know. We're learning as we go.’"

Information provided in Yale Medicine articles is for general informational purposes only. No content in the articles should ever be used as a substitute for medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Always seek the individual advice of your health care provider with any questions you have regarding a medical condition.

More news from Yale Medicine

The complexity of managing COVID-19: How important is good governance?

- Download the essay

Subscribe to Global Connection

Alaka m. basu , amb alaka m. basu professor, department of global development - cornell university, senior fellow - united nations foundation kaushik basu , and kaushik basu nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development @kaushikcbasu jose maria u. tapia jmut jose maria u. tapia student - cornell university.

November 17, 2020

- 13 min read

This essay is part of “ Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 world ,” a collection of 12 essays presenting new ideas to guide policies and shape debates in a post-COVID-19 world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacy of public health systems worldwide, casting a shadow that we could not have imagined even a year ago. As the fog of confusion lifts and we begin to understand the rudiments of how the virus behaves, the end of the pandemic is nowhere in sight. The number of cases and the deaths continue to rise. The latter breached the 1 million mark a few weeks ago and it looks likely now that, in terms of severity, this pandemic will surpass the Asian Flu of 1957-58 and the Hong Kong Flu of 1968-69.

Moreover, a parallel problem may well exceed the direct death toll from the virus. We are referring to the growing economic crises globally, and the prospect that these may hit emerging economies especially hard.

The economic fall-out is not entirely the direct outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic but a result of how we have responded to it—what measures governments took and how ordinary people, workers, and firms reacted to the crisis. The government activism to contain the virus that we saw this time exceeds that in previous such crises, which may have dampened the spread of the COVID-19 but has extracted a toll from the economy.

This essay takes stock of the policies adopted by governments in emerging economies, and what effect these governance strategies may have had, and then speculates about what the future is likely to look like and what we may do here on.

Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market.

It is becoming clear that the scramble among several emerging economies to imitate and outdo European and North American countries was a mistake. We get a glimpse of this by considering two nations continents apart, the economies of which have been among the hardest hit in the world, namely, Peru and India. During the second quarter of 2020, Peru saw an annual growth of -30.2 percent and India -23.9 percent. From the global Q2 data that have emerged thus far, Peru and India are among the four slowest growing economies in the world. Along with U.K and Tunisia these are the only nations that lost more than 20 percent of their GDP. 1

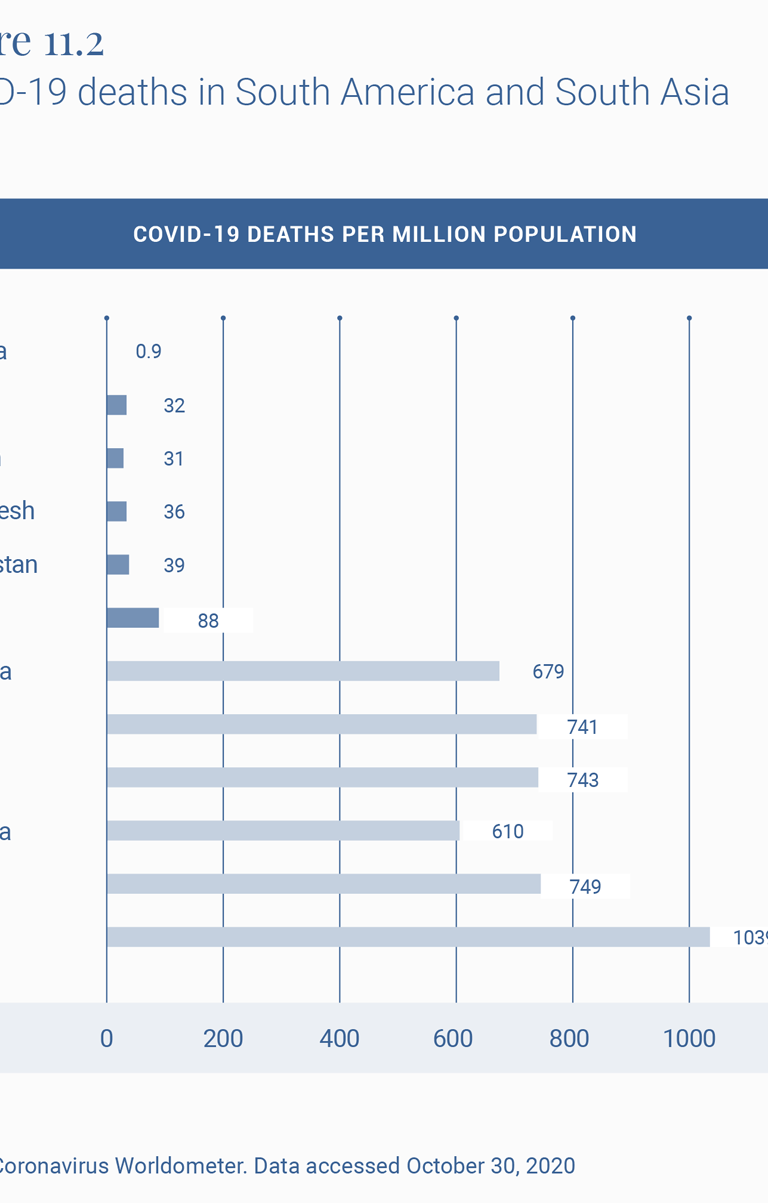

COVID-19-related mortality statistics, and, in particular, the Crude Mortality Rate (CMR), however imperfect, are the most telling indicator of the comparative scale of the pandemic in different countries. At first glance, from the end of October 2020, Peru, with 1039 COVID-19 deaths per million population looks bad by any standard and much worse than India with 88. Peru’s CMR is currently among the highest reported globally.

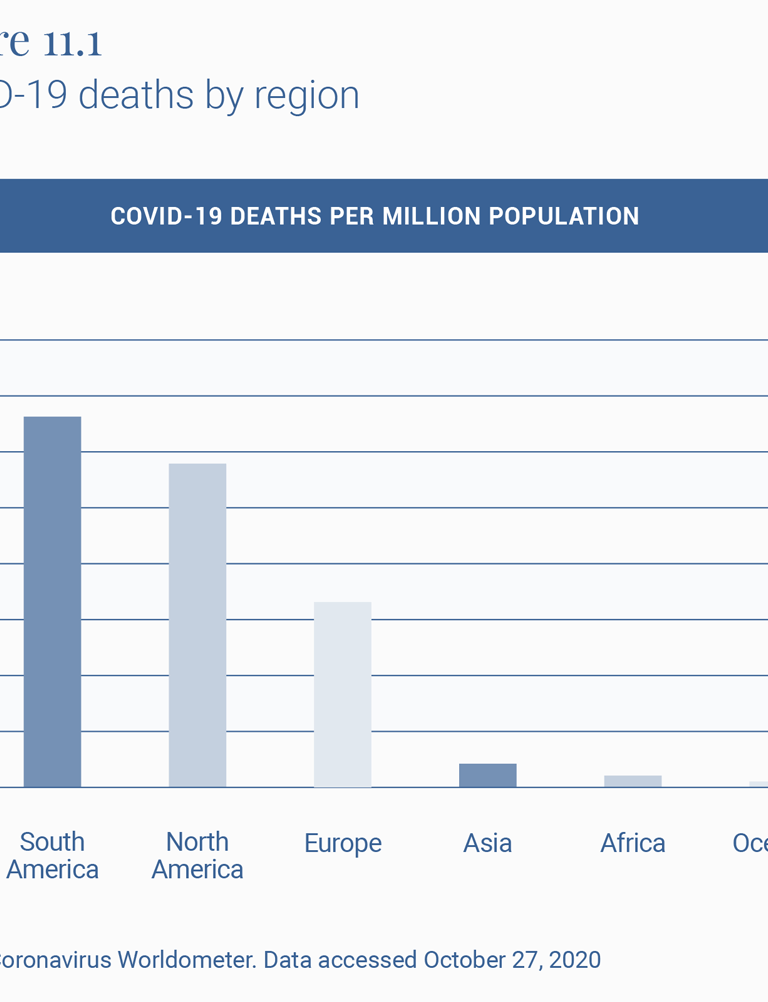

However, both Peru and India need to be placed in regional perspective. For reasons that are likely to do with the history of past diseases, there are striking regional differences in the lethality of the virus (Figure 11.1). South America is worse hit than any other world region, and Asia and Africa seem to have got it relatively lightly, in contrast to Europe and America. The stark regional difference cries out for more epidemiological analysis. But even as we await that, these are differences that cannot be ignored.

To understand the effect of policy interventions, it is therefore important to look at how these countries fare within their own regions, which have had similar histories of illnesses and viruses (Figure 11.2). Both Peru and India do much worse than the neighbors with whom they largely share their social, economic, ecological and demographic features. Peru’s COVID-19 mortality rate per million population, or CMR, of 1039 is ahead of the second highest, Brazil at 749, and almost twice that of Argentina at 679.

Similarly, India at 88 compares well with Europe and the U.S., as does virtually all of Asia and Africa, but is doing much worse than its neighbors, with the second worst country in the region, Afghanistan, experiencing less than half the death rate of India.

The official Indian statement that up to 78,000 deaths 2 were averted by the lockdown has been criticized 3 for its assumptions. A more reasonable exercise is to estimate the excess deaths experienced by a country that breaks away from the pattern of its regional neighbors. So, for example, if India had experienced Afghanistan’s COVID-19 mortality rate, it would by now have had 54,112 deaths. And if it had the rate reported by Bangladesh, it would have had 49,950 deaths from COVID-19 today. In other words, more than half its current toll of some 122,099 COVID-19 deaths would have been avoided if it had experienced the same virus hit as its neighbors.

What might explain this outlier experience of COVID-19 CMRs and economic downslide in India and Peru? If the regional background conditions are broadly similar, one is left to ask if it is in fact the policy response that differed markedly and might account for these relatively poor outcomes.

Peru and India have performed poorly in terms of GDP growth rate in Q2 2020 among the countries displayed in Table 2, and given that both these countries are often treated as case studies of strong governance, this draws attention to the fact that there may be a dissonance between strong governance and good governance.

The turnaround for India has been especially surprising, given that until a few years ago it was among the three fastest growing economies in the world. The slowdown began in 2016, though the sharp downturn, sharper than virtually all other countries, occurred after the lockdown.

On the COVID-19 policy front, both India and Peru have become known for what the Oxford University’s COVID Policy Tracker 4 calls the “stringency” of the government’s response to the epidemic. At 8 pm on March 24, 2020, the Indian government announced, with four hours’ notice, a complete nationwide shutdown. Virtually all movement outside the perimeter of one’s home was officially sought to be brought to a standstill. Naturally, as described in several papers, such as that of Ray and Subramanian, 5 this meant that most economic life also came to a sudden standstill, which in turn meant that hundreds of millions of workers in the informal, as well as more marginally formal sectors, lost their livelihoods.

In addition, tens of millions of these workers, being migrant workers in places far-flung from their original homes, also lost their temporary homes and their savings with these lost livelihoods, so that the only safe space that beckoned them was their place of origin in small towns and villages often hundreds of miles away from their places of work.

After a few weeks of precarious living in their migrant destinations, they set off, on foot since trains and buses had been stopped, for these towns and villages, creating a “lockdown and scatter” that spread the virus from the city to the town and the town to the village. Indeed, “lockdown” is a bit of a misnomer for what happened in India, since over 20 million people did exactly the opposite of what one does in a lockdown. Thus India had a strange combination of lockdown some and scatter the rest, like in no other country. They spilled out and scattered in ways they would otherwise not do. It is not surprising that the infection, which was marginally present in rural areas (23 percent in April), now makes up some 54 percent of all cases in India. 6

In Peru too, the lockdown was sudden, nationwide, long drawn out and stringent. 7 Jobs were lost, financial aid was difficult to disburse, migrant workers were forced to return home, and the virus has now spread to all parts of the country with death rates from it surpassing almost every other part of the world.

As an aside, to think about ways of implementing lockdowns that are less stringent and geographically as well as functionally less total, an example from yet another continent is instructive. Ethiopia, with a COVID-19 death rate of 13 per million population seems to have bettered the already relatively low African rate of 31 in Table 1. 8

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability.

The way forward

We next move from the immediate crisis to the medium term. Where is the world headed and how should we deal with the new world? Arguably, that two sectors that will emerge larger and stronger in the post-pandemic world are: digital technology and outsourcing, and healthcare and pharmaceuticals.

The last 9 months of the pandemic have been a huge training ground for people in the use of digital technology—Zoom, WebEx, digital finance, and many others. This learning-by-doing exercise is likely to give a big boost to outsourcing, which has the potential to help countries like India, the Philippines, and South Africa.

Globalization may see a short-run retreat but, we believe, it will come back with a vengeance. Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market. This realization will make most countries reverse their knee-jerk anti-globalization; and the ones that do not will cease to be important global players. Either way, globalization will be back on track and with a much greater amount of outsourcing.

To return, more critically this time, to our earlier aside on Ethiopia, its historical and contemporary record on tampering with internet connectivity 9 in an attempt to muzzle inter-ethnic tensions and political dissent will not serve it well in such a post-pandemic scenario. This is a useful reminder for all emerging market economies.

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability. This could divert some demand from luxury goods to better health, and what is best described as “creative consumption”: art, music, and culture. 10 The former will mean much larger healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors.

But to take advantage of these new opportunities, nations will need to navigate the current predicament so that they have a viable economy once the pandemic passes. Thus it is important to be able to control the pandemic while keeping the economy open. There is some emerging literature 11 on this, but much more is needed. This is a governance challenge of a kind rarely faced, because the pandemic has disrupted normal markets and there is need, at least in the short run, for governments to step in to fill the caveat.

Emerging economies will have to devise novel governance strategies for doing this double duty of tamping down on new infections without strident controls on economic behavior and without blindly imitating Europe and America.

Here is an example. One interesting opportunity amidst this chaos is to tap into the “resource” of those who have already had COVID-19 and are immune, even if only in the short-term—we still have no definitive evidence on the length of acquired immunity. These people can be offered a high salary to work in sectors that require physical interaction with others. This will help keep supply chains unbroken. Normally, the market would have on its own caused such a salary increase but in this case, the main benefit of marshaling this labor force is on the aggregate economy and GDP and therefore is a classic case of positive externality, which the free market does not adequately reward. It is more a challenge of governance. As with most economic policy, this will need careful research and design before being implemented. We have to be aware that a policy like this will come with its risk of bribery and corruption. There is also the moral hazard challenge of poor people choosing to get COVID-19 in order to qualify for these special jobs. Safeguards will be needed against these risks. But we believe that any government that succeeds in implementing an intelligently-designed intervention to draw on this huge, under-utilized resource can have a big, positive impact on the economy 12 .

This is just one idea. We must innovate in different ways to survive the crisis and then have the ability to navigate the new world that will emerge, hopefully in the not too distant future.

Related Content

Emiliana Vegas, Rebecca Winthrop

Homi Kharas, John W. McArthur

Anthony F. Pipa, Max Bouchet

Note: We are grateful for financial support from Cornell University’s Hatfield Fund for the research associated with this paper. We also wish to express our gratitude to Homi Kharas for many suggestions and David Batcheck for generous editorial help.

- “GDP Annual Growth Rate – Forecast 2020-2022,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/forecast/gdp-annual-growth-rate.

- “Government Cites Various Statistical Models, Says Averted Between 1.4 Million-2.9 Million Cases Due To Lockdown,” Business World, May 23, 2020, www.businessworld.in/article/Government-Cites-Various-Statistical-Models-Says-Averted-Between-1-4-million-2-9-million-Cases-Due-To-Lockdown/23-05-2020-193002/.

- Suvrat Raju, “Did the Indian lockdown avert deaths?” medRxiv , July 5, 2020, https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr183813#A1.

- “COVID Policy Tracker,” Oxford University, https://github.com/OxCGRT/covid-policy-tracker t.

- Debraj Ray and S. Subramanian, “India’s Lockdown: An Interim Report,” NBER Working Paper, May 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27282.

- Gopika Gopakumar and Shayan Ghosh, “Rural recovery could slow down as cases rise, says Ghosh,” Mint, August 19, 2020, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/rural-recovery-could-slow-down-as-cases-rise-says-ghosh-11597801644015.html.

- Pierina Pighi Bel and Jake Horton, “Coronavirus: What’s happening in Peru?,” BBC, July 9, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-53150808.

- “No lockdown, few ventilators, but Ethiopia is beating Covid-19,” Financial Times, May 27, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/7c6327ca-a00b-11ea-b65d-489c67b0d85d.

- Cara Anna, “Ethiopia enters 3rd week of internet shutdown after unrest,” Washington Post, July 14, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/ethiopia-enters-3rd-week-of-internet-shutdown-after-unrest/2020/07/14/4699c400-c5d6-11ea-a825-8722004e4150_story.html.

- Patrick Kabanda, The Creative Wealth of Nations: Can the Arts Advance Development? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Guanlin Li et al, “Disease-dependent interaction policies to support health and economic outcomes during the COVID-19 epidemic,” medRxiv, August 2020, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.24.20180752v3.

- For helpful discussion concerning this idea, we are grateful to Turab Hussain, Daksh Walia and Mehr-un-Nisa, during a seminar of South Asian Economics Students’ Meet (SAESM).

Global Economy and Development

Tedros Adhanom-Ghebreyesus

May 9, 2024

Robin Brooks

Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Elyse Painter

May 8, 2024

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2021

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews

- Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento 1 , 2 ,

- Dónal P. O’Mathúna 3 , 4 ,

- Thilo Caspar von Groote 5 ,

- Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem 6 ,

- Ishanka Weerasekara 7 , 8 ,

- Ana Marusic 9 ,

- Livia Puljak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-6061 10 ,

- Vinicius Tassoni Civile 11 ,

- Irena Zakarija-Grkovic 9 ,

- Tina Poklepovic Pericic 9 ,

- Alvaro Nagib Atallah 11 ,

- Santino Filoso 12 ,

- Nicola Luigi Bragazzi 13 &

- Milena Soriano Marcolino 1

On behalf of the International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19)

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 21 , Article number: 525 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

29 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

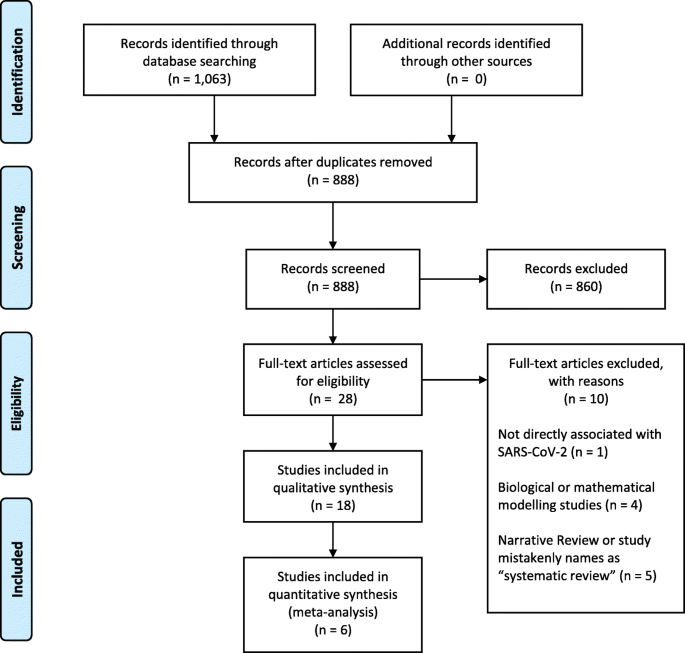

Navigating the rapidly growing body of scientific literature on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is challenging, and ongoing critical appraisal of this output is essential. We aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Nine databases (Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Sciences, PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research, LILACS, and Epistemonikos) were searched from December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020. Systematic reviews analyzing primary studies of COVID-19 were included. Two authors independently undertook screening, selection, extraction (data on clinical symptoms, prevalence, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, diagnostic test assessment, laboratory, and radiological findings), and quality assessment (AMSTAR 2). A meta-analysis was performed of the prevalence of clinical outcomes.

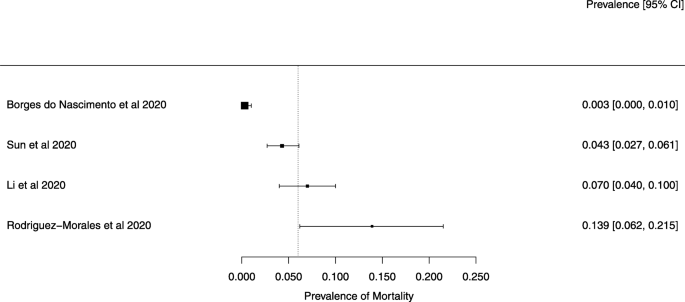

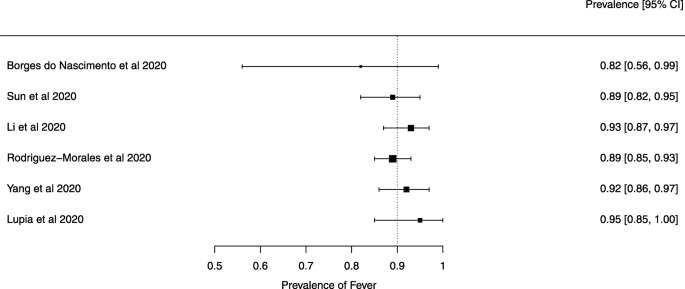

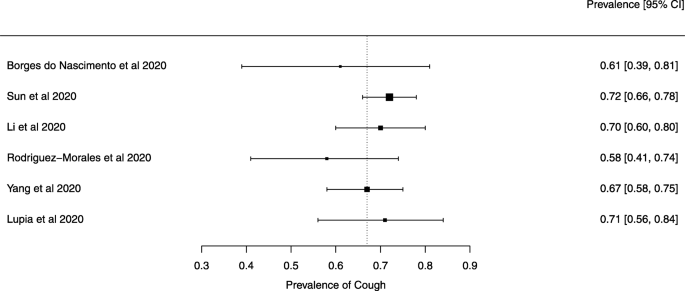

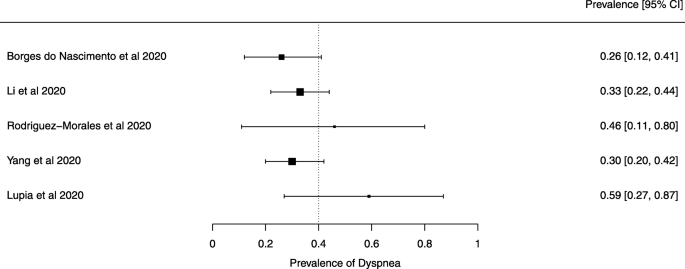

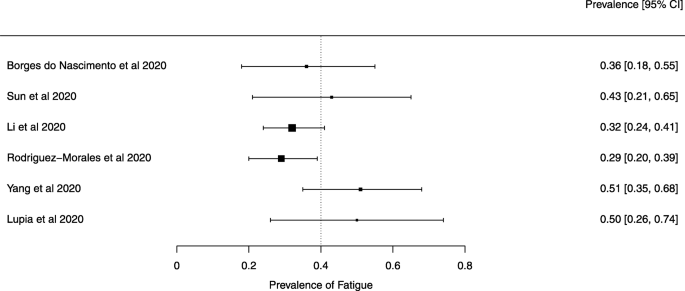

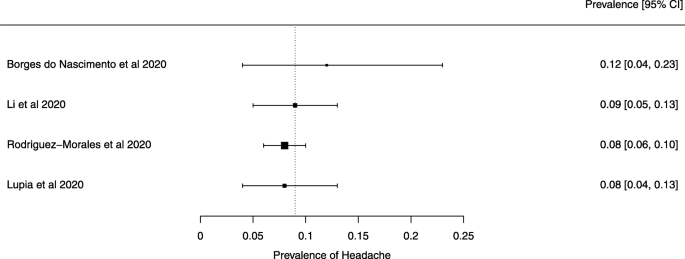

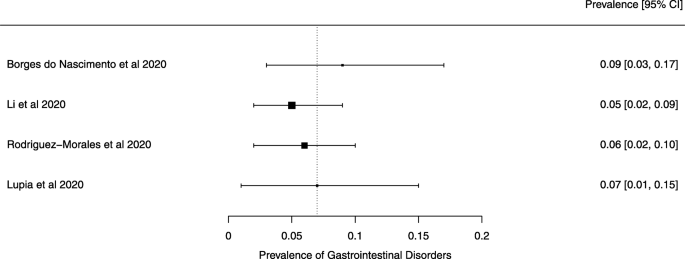

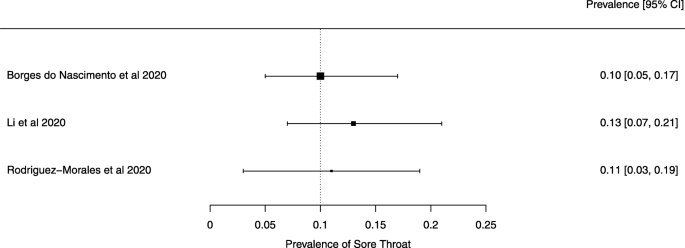

Eighteen systematic reviews were included; one was empty (did not identify any relevant study). Using AMSTAR 2, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low”. Identified symptoms of COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%) and gastrointestinal complaints (5–9%). Severe symptoms were more common in men. Elevated C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase, and slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, were commonly described. Thrombocytopenia and elevated levels of procalcitonin and cardiac troponin I were associated with severe disease. A frequent finding on chest imaging was uni- or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity. A single review investigated the impact of medication (chloroquine) but found no verifiable clinical data. All-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9%.

Conclusions

In this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic were of questionable usefulness. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards.

Peer Review reports

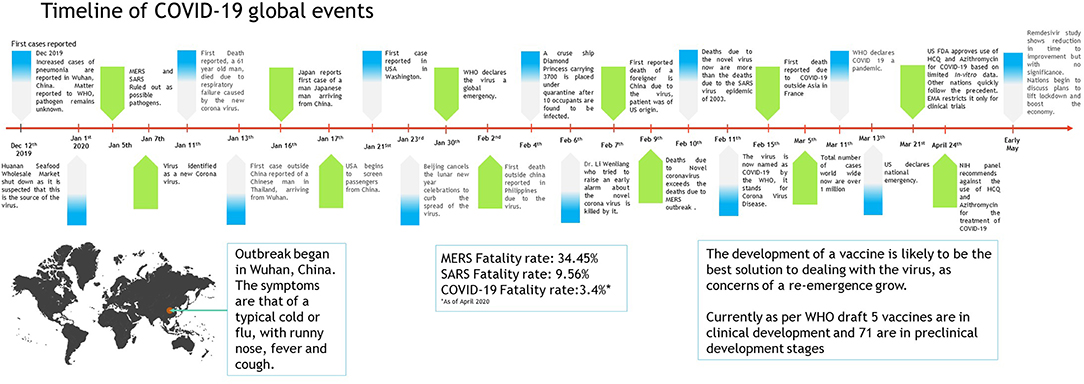

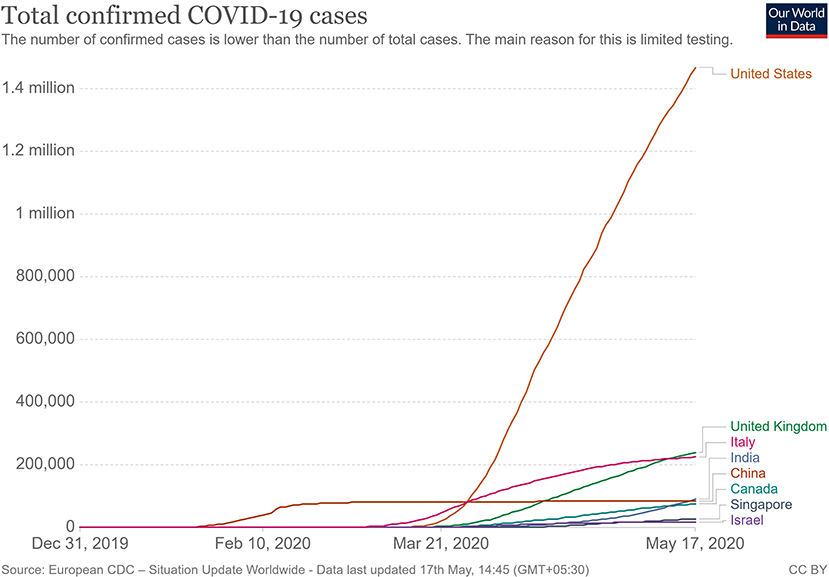

The spread of the “Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), the causal agent of COVID-19, was characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 and has triggered an international public health emergency [ 1 ]. The numbers of confirmed cases and deaths due to COVID-19 are rapidly escalating, counting in millions [ 2 ], causing massive economic strain, and escalating healthcare and public health expenses [ 3 , 4 ].

The research community has responded by publishing an impressive number of scientific reports related to COVID-19. The world was alerted to the new disease at the beginning of 2020 [ 1 ], and by mid-March 2020, more than 2000 articles had been published on COVID-19 in scholarly journals, with 25% of them containing original data [ 5 ]. The living map of COVID-19 evidence, curated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), contained more than 40,000 records by February 2021 [ 6 ]. More than 100,000 records on PubMed were labeled as “SARS-CoV-2 literature, sequence, and clinical content” by February 2021 [ 7 ].

Due to publication speed, the research community has voiced concerns regarding the quality and reproducibility of evidence produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, warning of the potential damaging approach of “publish first, retract later” [ 8 ]. It appears that these concerns are not unfounded, as it has been reported that COVID-19 articles were overrepresented in the pool of retracted articles in 2020 [ 9 ]. These concerns about inadequate evidence are of major importance because they can lead to poor clinical practice and inappropriate policies [ 10 ].

Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of today’s evidence-informed decision-making. By synthesizing all relevant evidence regarding a particular topic, systematic reviews reflect the current scientific knowledge. Systematic reviews are considered to be at the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence and should be used to make informed decisions. However, with high numbers of systematic reviews of different scope and methodological quality being published, overviews of multiple systematic reviews that assess their methodological quality are essential [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. An overview of systematic reviews helps identify and organize the literature and highlights areas of priority in decision-making.

In this overview of systematic reviews, we aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Methodology

Research question.

This overview’s primary objective was to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews that assessed any type of primary clinical data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Our research question was purposefully broad because we wanted to analyze as many systematic reviews as possible that were available early following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Study design

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews. The idea for this overview originated in a protocol for a systematic review submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020170623), which indicated a plan to conduct an overview.

Overviews of systematic reviews use explicit and systematic methods for searching and identifying multiple systematic reviews addressing related research questions in the same field to extract and analyze evidence across important outcomes. Overviews of systematic reviews are in principle similar to systematic reviews of interventions, but the unit of analysis is a systematic review [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

We used the overview methodology instead of other evidence synthesis methods to allow us to collate and appraise multiple systematic reviews on this topic, and to extract and analyze their results across relevant topics [ 17 ]. The overview and meta-analysis of systematic reviews allowed us to investigate the methodological quality of included studies, summarize results, and identify specific areas of available or limited evidence, thereby strengthening the current understanding of this novel disease and guiding future research [ 13 ].

A reporting guideline for overviews of reviews is currently under development, i.e., Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) [ 18 ]. As the PRIOR checklist is still not published, this study was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 statement [ 19 ]. The methodology used in this review was adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and also followed established methodological considerations for analyzing existing systematic reviews [ 14 ].

Approval of a research ethics committee was not necessary as the study analyzed only publicly available articles.

Eligibility criteria

Systematic reviews were included if they analyzed primary data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 as confirmed by RT-PCR or another pre-specified diagnostic technique. Eligible reviews covered all topics related to COVID-19 including, but not limited to, those that reported clinical symptoms, diagnostic methods, therapeutic interventions, laboratory findings, or radiological results. Both full manuscripts and abbreviated versions, such as letters, were eligible.

No restrictions were imposed on the design of the primary studies included within the systematic reviews, the last search date, whether the review included meta-analyses or language. Reviews related to SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses were eligible, but from those reviews, we analyzed only data related to SARS-CoV-2.

No consensus definition exists for a systematic review [ 20 ], and debates continue about the defining characteristics of a systematic review [ 21 ]. Cochrane’s guidance for overviews of reviews recommends setting pre-established criteria for making decisions around inclusion [ 14 ]. That is supported by a recent scoping review about guidance for overviews of systematic reviews [ 22 ].

Thus, for this study, we defined a systematic review as a research report which searched for primary research studies on a specific topic using an explicit search strategy, had a detailed description of the methods with explicit inclusion criteria provided, and provided a summary of the included studies either in narrative or quantitative format (such as a meta-analysis). Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews were considered eligible for inclusion, with or without meta-analysis, and regardless of the study design, language restriction and methodology of the included primary studies. To be eligible for inclusion, reviews had to be clearly analyzing data related to SARS-CoV-2 (associated or not with other viruses). We excluded narrative reviews without those characteristics as these are less likely to be replicable and are more prone to bias.

Scoping reviews and rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview if they met our pre-defined inclusion criteria noted above. We included reviews that addressed SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses if they reported separate data regarding SARS-CoV-2.

Information sources

Nine databases were searched for eligible records published between December 1, 2019, and March 24, 2020: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Sciences, LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), and Epistemonikos.

The comprehensive search strategy for each database is provided in Additional file 1 and was designed and conducted in collaboration with an information specialist. All retrieved records were primarily processed in EndNote, where duplicates were removed, and records were then imported into the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. In addition to database searches, we screened reference lists of reviews included after screening records retrieved via databases.

Study selection

All searches, screening of titles and abstracts, and record selection, were performed independently by two investigators using the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. Articles deemed potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text screening carried out independently by two investigators. Discrepancies at all stages were resolved by consensus. During the screening, records published in languages other than English were translated by a native/fluent speaker.

Data collection process

We custom designed a data extraction table for this study, which was piloted by two authors independently. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third researcher.

We extracted the following data: article identification data (authors’ name and journal of publication), search period, number of databases searched, population or settings considered, main results and outcomes observed, and number of participants. From Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), we extracted journal rank (quartile) and Journal Impact Factor (JIF).

We categorized the following as primary outcomes: all-cause mortality, need for and length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospitalization (in days), admission to intensive care unit (yes/no), and length of stay in the intensive care unit.

The following outcomes were categorized as exploratory: diagnostic methods used for detection of the virus, male to female ratio, clinical symptoms, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, laboratory findings (full blood count, liver enzymes, C-reactive protein, d-dimer, albumin, lipid profile, serum electrolytes, blood vitamin levels, glucose levels, and any other important biomarkers), and radiological findings (using radiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound).

We also collected data on reporting guidelines and requirements for the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses from journal websites where included reviews were published.

Quality assessment in individual reviews

Two researchers independently assessed the reviews’ quality using the “A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2)”. We acknowledge that the AMSTAR 2 was created as “a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both” [ 24 ]. However, since AMSTAR 2 was designed for systematic reviews of intervention trials, and we included additional types of systematic reviews, we adjusted some AMSTAR 2 ratings and reported these in Additional file 2 .

Adherence to each item was rated as follows: yes, partial yes, no, or not applicable (such as when a meta-analysis was not conducted). The overall confidence in the results of the review is rated as “critically low”, “low”, “moderate” or “high”, according to the AMSTAR 2 guidance based on seven critical domains, which are items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 as defined by AMSTAR 2 authors [ 24 ]. We reported our adherence ratings for transparency of our decision with accompanying explanations, for each item, in each included review.

One of the included systematic reviews was conducted by some members of this author team [ 25 ]. This review was initially assessed independently by two authors who were not co-authors of that review to prevent the risk of bias in assessing this study.

Synthesis of results

For data synthesis, we prepared a table summarizing each systematic review. Graphs illustrating the mortality rate and clinical symptoms were created. We then prepared a narrative summary of the methods, findings, study strengths, and limitations.

For analysis of the prevalence of clinical outcomes, we extracted data on the number of events and the total number of patients to perform proportional meta-analysis using RStudio© software, with the “meta” package (version 4.9–6), using the “metaprop” function for reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, excluding case studies because of the absence of variance. For reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, we presented pooled results of proportions with their respective confidence intervals (95%) by the inverse variance method with a random-effects model, using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for τ 2 . We adjusted data using Freeman-Tukey double arcosen transformation. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for individual studies. We created forest plots using the RStudio© software, with the “metafor” package (version 2.1–0) and “forest” function.

Managing overlapping systematic reviews