What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Essays are brief, non-fiction compositions that describe, clarify, argue, or analyze a subject. Students might encounter essay assignments in any school subject and at any level of school, from a personal experience "vacation" essay in middle school to a complex analysis of a scientific process in graduate school. Components of an essay include an introduction , thesis statement , body, and conclusion.

Writing an Introduction

The beginning of an essay can seem daunting. Sometimes, writers can start their essay in the middle or at the end, rather than at the beginning, and work backward. The process depends on each individual and takes practice to figure out what works best for them. Regardless of where students start, it is recommended that the introduction begins with an attention grabber or an example that hooks the reader in within the very first sentence.

The introduction should accomplish a few written sentences that leads the reader into the main point or argument of the essay, also known as a thesis statement. Typically, the thesis statement is the very last sentence of an introduction, but this is not a rule set in stone, despite it wrapping things up nicely. Before moving on from the introduction, readers should have a good idea of what is to follow in the essay, and they should not be confused as to what the essay is about. Finally, the length of an introduction varies and can be anywhere from one to several paragraphs depending on the size of the essay as a whole.

Creating a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a sentence that states the main idea of the essay. The function of a thesis statement is to help manage the ideas within the essay. Different from a mere topic, the thesis statement is an argument, option, or judgment that the author of the essay makes about the topic of the essay.

A good thesis statement combines several ideas into just one or two sentences. It also includes the topic of the essay and makes clear what the author's position is in regard to the topic. Typically found at the beginning of a paper, the thesis statement is often placed in the introduction, toward the end of the first paragraph or so.

Developing a thesis statement means deciding on the point of view within the topic, and stating this argument clearly becomes part of the sentence which forms it. Writing a strong thesis statement should summarize the topic and bring clarity to the reader.

For informative essays, an informative thesis should be declared. In an argumentative or narrative essay, a persuasive thesis, or opinion, should be determined. For instance, the difference looks like this:

- Informative Thesis Example: To create a great essay, the writer must form a solid introduction, thesis statement, body, and conclusion.

- Persuasive Thesis Example: Essays surrounded around opinions and arguments are so much more fun than informative essays because they are more dynamic, fluid, and teach you a lot about the author.

Developing Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs of an essay include a group of sentences that relate to a specific topic or idea around the main point of the essay. It is important to write and organize two to three full body paragraphs to properly develop it.

Before writing, authors may choose to outline the two to three main arguments that will support their thesis statement. For each of those main ideas, there will be supporting points to drive them home. Elaborating on the ideas and supporting specific points will develop a full body paragraph. A good paragraph describes the main point, is full of meaning, and has crystal clear sentences that avoid universal statements.

Ending an Essay With a Conclusion

A conclusion is an end or finish of an essay. Often, the conclusion includes a judgment or decision that is reached through the reasoning described throughout the essay. The conclusion is an opportunity to wrap up the essay by reviewing the main points discussed that drives home the point or argument stated in the thesis statement.

The conclusion may also include a takeaway for the reader, such as a question or thought to take with them after reading. A good conclusion may also invoke a vivid image, include a quotation, or have a call to action for readers.

- How To Write an Essay

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

- How to Structure an Essay

- How to Help Your 4th Grader Write a Biography

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- Unity in Composition

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- An Essay Revision Checklist

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- The Five Steps of Writing an Essay

How to write an essay

Part of English Writing skills

Did you know?

The word essay comes from the French word 'essayer' close Sorry, something went wrong Check your connection, refresh the page and try again. meaning ‘to try’ or ‘to attempt’. A French writer called Michel de Montaigne invented the essay in Europe as his ‘attempt’ to write about himself and his thoughts.

Introduction to how to write an essay

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

An essay is a piece of non-fiction writing with a clear structure : an introduction, paragraphs with evidence and a conclusion. Writing an essay is an important skill in English and allows you to show your knowledge and understanding of the texts you read and study.

It is important to plan your essay before you start writing so that you write clearly and thoughtfully about the essay topic. Evidence , in the form of quotations and examples, is the foundation of an effective essay and provides proof for your points.

Video about planning an essay

Learn how to plan, structure and use evidence in your essays

Why do we write essays?

The purpose of an essay is to show your understanding, views or opinions in response to an essay question, and to persuade the reader that what you are writing makes sense and can be backed up with evidence. In a literature essay, this usually means looking closely at a text (for example, a novel, poem or play) and responding to it with your ideas.

Essays can focus on a particular section of a text, for example, a particular chapter or scene, or ask a big picture question to make you think deeply about a character, idea or theme throughout the whole text.

Often essays are questions, for example, ‘How does the character Jonas change in the novel, The Giver by Lois Lowry?’ or they can be written using command words to tell you what to do, for example ‘Examine how the character Jonas changes in the novel, The Giver by Lois Lowry.’

It is important to look carefully at the essay question or title so that you keep your essay focused and relevant. If the essay tells you to compare two specific poems, you shouldn’t just talk about the two poems separately and you shouldn’t bring in lots of other poems.

Writing skills

- count 7 of 7

Writing skills - tone & style

- count 1 of 7

Writing Skills - sentences

- count 2 of 7

- Words with Friends Cheat

- Wordle Solver

- Word Unscrambler

- Scrabble Dictionary

- Anagram Solver

- Wordscapes Answers

Make Our Dictionary Yours

Sign up for our weekly newsletters and get:

- Grammar and writing tips

- Fun language articles

- #WordOfTheDay and quizzes

By signing in, you agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy .

We'll see you in your inbox soon.

5 Main Parts of an Essay: An Easy Guide to a Solid Structure

- DESCRIPTION Student working on his computer, sitting outdoors

- SOURCE Deagreez / iStock / Getty Images Plus

- PERMISSION Used under Getty Images license

You might think of essays as boring assignments for explaining the themes in Huckleberry Finn or breaking down the characters in The Great Gatsby , but the essay is one of the most timeless forms in all of literature. It’s a genre that includes deep readings of texts, personal essays, and journalistic reports. Before you get to any of that, you need to figure out the basic parts of the essay.

What Are the Parts of an Essay?

You can think of any essay as consisting of three parts: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. You might see some small variations, but for the most part, that is the structure of any essay.

Take the five-paragraph essay as a simple example. With that form, you get one introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph. That’s five paragraphs, but three parts.

What Are the Main Parts of an Essay Printable 2022

Like a good word burger: how to write the three parts of an essay.

A good essay is much like a good burger (or a sandwich, but we’re a burger society here). Your intro and conclusion are the buns sandwiching the patty, cheese, and other good toppings of the body paragraphs.

What Is an Introduction Paragraph?

“Hello! My name is Seymour. It’s nice to meet you.” That might seem like a simple, non-essay introduction, but it has all the basic components of what you want in an introduction paragraph . You start with the hook. Your hook is the first sentence of your entire essay, so you want to grab people’s attention (or hook them) immediately.

From there, you have sentences that lead the reader directly to the thesis sentence . Your thesis is possibly the most important part of your entire essay. It’s the entire raison d'être . It’s what you’re arguing or trying to accomplish with your essay as a whole.

Kaboom! That, the sound of the entire universe forming in an instant, giving rise to apples, toenails, and what we know today as the humble five-paragraph essay. Since that fortuitous moment, the five-paragraph essay has become the favorite assignment among English teachers, to the bemusement of students. Although many educators, professionals, and youths have valid criticisms about the form, the five-paragraph essay is an important component of developing writing skills and critical thought.

What Is a Body Paragraph?

The body paragraphs are the main part of your essay burger. Each body paragraph presents an idea that supports your thesis. This can include evidence from a literary source, details that build out your thesis, or explanations for your reasoning.

The first sentence of each body paragraph is known as the topic sentence . You can kind of think of it like a smaller part of your thesis sentence. It’s the main idea that you want to discuss in that specific body paragraph. The rest of the body paragraph is made up of supporting sentences, which support that topic sentence.

While many are critical of the five-paragraph essay’s rigid form, that rigidity is part of what makes it so advantageous. Every five-paragraph essay is an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion paragraph, and they will always have that structure. With such a stable form, a writer truly only needs to worry about the contents of the essay, putting all the focus on the actual writing and ideas, not the organization.

What Is a Concluding Paragraph?

A burger needs a solid, sturdy bottom bun. Otherwise, the burger would fall apart. The same holds for a conclusion. A good conclusion holds the essay together, while offering a unique finishing touch to the whole thing.

The conclusion is at once the easiest and hardest part of the essay. It’s easy in that it mostly involves restating your thesis and much of what you already discussed. The hard part is thinking outside of the essay and considering how your thesis applies to components of real life.

In conclusion, the five-paragraph essay is a useful and effective form for teaching students how to write and develop their critical thinking skills. It’s not without its setbacks, but it’s a simple form that can give way to other ways of writing. Longer research papers are essentially five-paragraph essays with more body paragraphs, while short fiction and creative writing require similar critical thought and writing acumen. Even if you don’t write, five-paragraph essays can teach you how to use your voice and express your ideas.

Explore Essay Examples

Understanding each part of an essay is essential to writing one, but seeing actual essay examples in the wild can take you from essay noob to essay expert. Look at specific types of essays, and see if you can pick out the different parts in each one — from thesis statements to hooks and concluding sentences.

- Argumentative Essay Examples

- About Me Essay Examples

- Descriptive Essay Examples

- Examples of Insightful Literary Analysis Essays

- Narrative Essay Examples

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

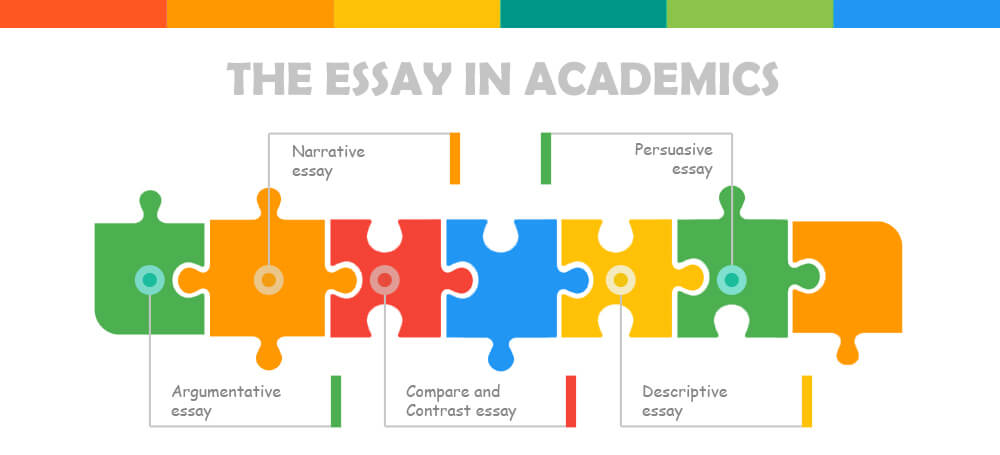

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Conclusions

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of conclusions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you evaluate conclusions you’ve drafted, and suggest approaches to avoid.

About conclusions

Introductions and conclusions can be difficult to write, but they’re worth investing time in. They can have a significant influence on a reader’s experience of your paper.

Just as your introduction acts as a bridge that transports your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. Such a conclusion will help them see why all your analysis and information should matter to them after they put the paper down.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to synthesize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final impression and to end on a positive note.

Your conclusion can go beyond the confines of the assignment. The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings.

Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate your topic in personally relevant ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest your reader, but also enrich your reader’s life in some way. It is your gift to the reader.

Strategies for writing an effective conclusion

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion:

- Play the “So What” Game. If you’re stuck and feel like your conclusion isn’t saying anything new or interesting, ask a friend to read it with you. Whenever you make a statement from your conclusion, ask the friend to say, “So what?” or “Why should anybody care?” Then ponder that question and answer it. Here’s how it might go: You: Basically, I’m just saying that education was important to Douglass. Friend: So what? You: Well, it was important because it was a key to him feeling like a free and equal citizen. Friend: Why should anybody care? You: That’s important because plantation owners tried to keep slaves from being educated so that they could maintain control. When Douglass obtained an education, he undermined that control personally. You can also use this strategy on your own, asking yourself “So What?” as you develop your ideas or your draft.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize. Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help them to apply your info and ideas to their own life or to see the broader implications.

- Point to broader implications. For example, if your paper examines the Greensboro sit-ins or another event in the Civil Rights Movement, you could point out its impact on the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. A paper about the style of writer Virginia Woolf could point to her influence on other writers or on later feminists.

Strategies to avoid

- Beginning with an unnecessary, overused phrase such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “in closing.” Although these phrases can work in speeches, they come across as wooden and trite in writing.

- Stating the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion.

- Introducing a new idea or subtopic in your conclusion.

- Ending with a rephrased thesis statement without any substantive changes.

- Making sentimental, emotional appeals that are out of character with the rest of an analytical paper.

- Including evidence (quotations, statistics, etc.) that should be in the body of the paper.

Four kinds of ineffective conclusions

- The “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” Conclusion. This conclusion just restates the thesis and is usually painfully short. It does not push the ideas forward. People write this kind of conclusion when they can’t think of anything else to say. Example: In conclusion, Frederick Douglass was, as we have seen, a pioneer in American education, proving that education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

- The “Sherlock Holmes” Conclusion. Sometimes writers will state the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion. You might be tempted to use this strategy if you don’t want to give everything away too early in your paper. You may think it would be more dramatic to keep the reader in the dark until the end and then “wow” them with your main idea, as in a Sherlock Holmes mystery. The reader, however, does not expect a mystery, but an analytical discussion of your topic in an academic style, with the main argument (thesis) stated up front. Example: (After a paper that lists numerous incidents from the book but never says what these incidents reveal about Douglass and his views on education): So, as the evidence above demonstrates, Douglass saw education as a way to undermine the slaveholders’ power and also an important step toward freedom.

- The “America the Beautiful”/”I Am Woman”/”We Shall Overcome” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion usually draws on emotion to make its appeal, but while this emotion and even sentimentality may be very heartfelt, it is usually out of character with the rest of an analytical paper. A more sophisticated commentary, rather than emotional praise, would be a more fitting tribute to the topic. Example: Because of the efforts of fine Americans like Frederick Douglass, countless others have seen the shining beacon of light that is education. His example was a torch that lit the way for others. Frederick Douglass was truly an American hero.

- The “Grab Bag” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion includes extra information that the writer found or thought of but couldn’t integrate into the main paper. You may find it hard to leave out details that you discovered after hours of research and thought, but adding random facts and bits of evidence at the end of an otherwise-well-organized essay can just create confusion. Example: In addition to being an educational pioneer, Frederick Douglass provides an interesting case study for masculinity in the American South. He also offers historians an interesting glimpse into slave resistance when he confronts Covey, the overseer. His relationships with female relatives reveal the importance of family in the slave community.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Douglass, Frederick. 1995. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. New York: Dover.

Hamilton College. n.d. “Conclusions.” Writing Center. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://www.hamilton.edu//academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/conclusions .

Holewa, Randa. 2004. “Strategies for Writing a Conclusion.” LEO: Literacy Education Online. Last updated February 19, 2004. https://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/conclude.html.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Paragraph Structure: A Short Guide

The function of paragraphs, the structure of paragraphs, paragraphs on the page.

- Troubleshooting, conclusions and further reading

Your essay is a journey through your argument or discussion. Your paragraphs are stepping stones in that journey, and they build up your argument, point by point.

Paragraphs have several functions. These include:

- Breaking the text into manageable units, so that the reader can clearly see the main sections

- Organising ideas: each paragraph should have just one main idea within it

- Providing a narrative flow through the document, as one idea links to the next

You can think of paragraphs as mini essays, discussing a single idea. They will vary depending on your academic discipline and the nature of your essay, but here is a good basic paragraph structure:

- Introduce your point: the first sentence of a paragraph should signpost the point to be made, using phrases such as: 'An alternative perspective to consider is'...or 'Another key issue is...'

- Elaborate: on the point you have introduced, making sure the argument that you are trying to put forward is clear.

- Evidence: provide the evidence that supports the point you are making.

- Comment: on the evidence. Criticise, analyse or engage with the evidence. How does it support your point?

- Conclude: your point and indicate what it means for your overall argument.

You should differentiate your paragraphs by indenting them or leaving extra line space in between. Check whether your academic school has a style preference for this. Whichever style you choose, ensure that you apply consistently. Make sure your paragraphs are not too long or too short. Page-long paragraphs indicate that you are trying to make too many points in one paragraph, or perhaps not writing concisely enough. One-sentence paragraphs suggest you are not developing your points properly, and will be pounced on by the marker.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Troubleshooting, conclusions and further reading >>

- Last Updated: Nov 20, 2023 1:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bham.ac.uk/asc/paragraphs

What is the purpose of an academic essay introduction?

This is the first of four chapters about Introductory Paragraphs . To complete this reader, read each chapter carefully and then unlock and complete our materials to check your understanding.

– Introduce the overall purpose of an essay introduction

– Break the purpose down into five key areas

– Describe each of the five areas in some detail

Chapter 1: What is the purpose of an academic essay introduction?

Chapter 2: What are the elements of an effective essay introduction?

Chapter 3: What are some possible introductory paragraph structures?

Chapter 4: What academic language may be useful in an introduction?

Before you begin reading...

- video and audio texts

- knowledge checks and quizzes

- skills practices, tasks and assignments

When writing an academic essay , it’s important to not only understand that there are separate sections of an essay – such as an introduction , a body and a conclusion , but to be able to recognise and utilise the possible elements and structures of each section that (when used correctly) should increase the chances of academic success. The following four chapters have therefore been created to outline and exemplify the overall purpose, individual elements, possible structures and useful language which are often recommended to university-level students who are writing essay introductions.

The first and most important aspect when writing an introduction is to understand the purpose of this essay section. Being familiar with the relationship between the writer, the reader and the introduction should help a writer to use this dynamic to their advantage. With such purpose in mind, we’ve isolated five aspects below that you should consider when planning your introduction:

1. Introducing the Topic

First and foremost, the key purpose of an essay introduction is to introduce the topic of that essay to the reader. Is your essay a compare and contrast or persuasive essay for example, and is the topic about language learning or economic stability? It’s important to let the reader (or your tutor) know exactly what they’re about to read as soon as possible, and then stick closely to that that topic throughout your essay . A good introduction should maintain a theme and remind the reader of that theme at various stages in the essay.

2. Contextualising the Topic

Not only is it important to introduce the focus of the essay , but one major purpose of an introduction is to provide the reader with the basic information they’ll need to understand the essay topic. Don’t forget that your reader may have never encountered such a topic before, and may therefore not have the general or subject-specific knowledge necessary to begin reading more deeply about that subject. Consider carefully which aspects of the topic are the most important for both the reader and for your essay argumentation, and then make sure to include and explain those in clear and concise language.

3. Signifying Purpose

Once you’ve introduced and contextualised the essay topic, it would then be a good idea to inform the reader of the overall purpose of the essay. How is the topic of your essay significant, and why are you investigating it? How are you investigating that topic; will your essay be balanced, critical or descriptive? The better you can prepare your reader for the type and purpose of essay that they’re about to read, the more logical and easy-to-follow your essay should seem to the reader.

4. Indicating Opinion

At the same time as signifying purpose, the writer should probably also indicate their opinion about the topic – if one is necessary for the type of essay being written. By informing the reader early on whether you’re for or against the essay topic or are planning on evaluating both sides of the argument, you’ll better prepare the reader for predicting the content of the essay. After all, a reader that’s able to predict content will usually find that content more coherent and cohesive .

5. Outlining Structure

Finally, once the reader has been informed and educated about the topic and understands the topic’s importance and how the writer feels about it, the last purpose of an essay introduction is to clearly outline the structure of that essay. Which main ideas will come first, and how will those arguments be ordered? Will the counter argument be provided before the writer’s arguments, and how many body paragraphs will there probably be? By providing an outline for the reader, that reader will likely be better prepared for the contents of your essay.

Once you’ve considered the overall purpose of your essay and understand the purpose of an introductory section , the next step is to look at the specific introductory elements that can be used to your advantage.

To reference this reader:

Academic Marker (2022) About Introductory Paragraphs . Available at: https://academicmarker.com/essay-writing/introductory-paragraphs/about-introductory-paragraphs/ (Accessed: Date Month Year).

- Brandeis University Writing Resources

- University of Arizona

Downloadables

Once you’ve completed all four chapters about introductory paragraphs , you might also wish to download our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets to test your progress or print for your students. These professional PDF worksheets can be easily accessed for only a few Academic Marks .

Our about introductory paragraphs academic reader (including all four chapters about this topic) can be accessed here at the click of a button.

Gain unlimited access to our about introductory paragraphs beginner worksheet, with activities and answer keys designed to check a basic understanding of this reader’s chapters.

To check a confident understanding of this reader’s chapters, click on the button below to download our about introductory paragraphs intermediate worksheet with activities and answer keys.

Our about introductory paragraphs advanced worksheet with activities and answer keys has been created to check a sophisticated understanding of this chapter’s worksheets.

To save yourself 5 Marks , click on the button below to gain unlimited access to all of our about introductory paragraphs guidance and worksheets. The All-in-1 Pack includes every chapter in this reader, as well as our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets in one handy PDF.

Click on the button below to gain unlimited access to our about introductory paragraphs teacher’s PowerPoint, which should include everything you’d need to successfully introduce this topic.

Collect Academic Marks

- 100 Marks for joining

- 25 Marks for daily e-learning

- 100-200 for feedback/testimonials

- 100-500 for referring your colleages/friends

Ultimate Guide to Writing Your College Essay

Tips for writing an effective college essay.

College admissions essays are an important part of your college application and gives you the chance to show colleges and universities your character and experiences. This guide will give you tips to write an effective college essay.

Want free help with your college essay?

UPchieve connects you with knowledgeable and friendly college advisors—online, 24/7, and completely free. Get 1:1 help brainstorming topics, outlining your essay, revising a draft, or editing grammar.

Writing a strong college admissions essay

Learn about the elements of a solid admissions essay.

Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

Learn some of the most common mistakes made on college essays

Brainstorming tips for your college essay

Stuck on what to write your college essay about? Here are some exercises to help you get started.

How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

Learn how formal your college essay should be and get tips on how to bring out your natural voice.

Taking your college essay to the next level

Hear an admissions expert discuss the appropriate level of depth necessary in your college essay.

Student Stories

Student Story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

Get the perspective of a current college student on how he approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about personal identity

Get the perspective of a current college student on how she approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about community impact

Student story: admissions essay about a past mistake, how to write a college application essay, tips for writing an effective application essay, sample college essay 1 with feedback, sample college essay 2 with feedback.

This content is licensed by Khan Academy and is available for free at www.khanacademy.org.

Argumentative Essay

Definition of argumentative essay.

An argumentative essay is a type of essay that presents arguments about both sides of an issue. It could be that both sides are presented equally balanced, or it could be that one side is presented more forcefully than the other. It all depends on the writer, and what side he supports the most. The general structure of an argumentative essay follows this format:

- Introduction : Attention Grabber/ hook , Background Information , Thesis Statement

- Body : Three body paragraphs (three major arguments)

- Counterargument : An argument to refute earlier arguments and give weight to the actual position

- Conclusion : Rephrasing the thesis statement , major points, call to attention, or concluding remarks .

Models for Argumentative Essays

There are two major models besides this structure given above, which is called a classical model. Two other models are the Toulmin and Rogerian models.

Toulmin model is comprised of an introduction with a claim or thesis, followed by the presentation of data to support the claim. Warrants are then listed for the reasons to support the claim with backing and rebuttals. However, the Rogerian model asks to weigh two options, lists the strengths and weaknesses of both options, and gives a recommendation after an analysis.

Five Types of Argument Claims in Essay Writing

There are five major types of argument claims as given below.

- A claim of definition

- A claim about values

- A claim about the reason

- A claim about comparison

- A claim about policy or position

A writer makes a claim about these issues and answers the relevant questions about it with relevant data and evidence to support the claim.

Three Major Types of Argument and How to Apply Them

Classical argument.

This model of applying argument is also called the Aristotelian model developed by Aristotle. This type of essay introduces the claim, with the opinion of the writer about the claim, its both perspectives, supported by evidence, and provides a conclusion about the better perspective . This essay includes an introduction, a body having the argument and support, a counter-argument with support, and a conclusion.

Toulmin Argument

This model developed by Stephen Toulmin is based on the claim followed by grounds, warrant, backing, qualifier, and rebuttal . Its structure comprises, an introduction having the main claim, a body with facts and evidence, while its rebuttal comprises counter-arguments and a conclusion.

Rogerian Argument

The third model by Carl Rogers has different perspectives having proof to support and a conclusion based on all the available perspectives. Its structure comprises an introduction with a thesis, the opposite point of view and claim, a middle-ground for both or more perspectives, and a conclusion.

Four Steps to Outline and Argumentative Essay

There are four major steps to outlining an argumentative essay.

- Introduction with background, claim, and thesis.

- Body with facts, definition, claim, cause and effect, or policy.

- The opposing point of view with pieces of evidence.

Examples of Argumentative Essay in Literature

Example #1: put a little science in your life by brian greene.

“When we consider the ubiquity of cellphones, iPods, personal computers and the Internet, it’s easy to see how science (and the technology to which it leads) is woven into the fabric of our day-to-day activities . When we benefit from CT scanners, M.R.I. devices, pacemakers and arterial stents, we can immediately appreciate how science affects the quality of our lives. When we assess the state of the world, and identify looming challenges like climate change, global pandemics, security threats and diminishing resources, we don’t hesitate in turning to science to gauge the problems and find solutions. And when we look at the wealth of opportunities hovering on the horizon—stem cells, genomic sequencing, personalized medicine, longevity research, nanoscience, brain-machine interface, quantum computers, space technology—we realize how crucial it is to cultivate a general public that can engage with scientific issues; there’s simply no other way that as a society we will be prepared to make informed decisions on a range of issues that will shape the future.”

These two paragraphs present an argument about two scientific fields — digital products and biotechnology. It has also given full supporting details with names.

Example #2: Boys Here, Girls There: Sure, If Equality’s the Goal by Karen Stabiner

“The first objections last week came from the National Organization for Women and the New York Civil Liberties Union, both of which opposed the opening of TYWLS in the fall of 1996. The two groups continue to insist—as though it were 1896 and they were arguing Plessy v. Ferguson—that separate can never be equal. I appreciate NOW ’s wariness of the Bush administration’s endorsement of single-sex public schools, since I am of the generation that still considers the label “feminist” to be a compliment—and many feminists still fear that any public acknowledgment of differences between the sexes will hinder their fight for equality .”

This paragraph by Karen Stabiner presents an objection to the argument of separation between public schools. It has been fully supported with evidence of the court case.

Example #3: The Flight from Conversation by Sherry Turkle

“We’ve become accustomed to a new way of being “ alone together.” Technology-enabled, we are able to be with one another, and also elsewhere, connected to wherever we want to be. We want to customize our lives. We want to move in and out of where we are because the thing we value most is control over where we focus our attention. We have gotten used to the idea of being in a tribe of one, loyal to our own party.”

This is an argument by Sherry Turkle, who beautifully presented it in the first person plural dialogues . However, it is clear that this is part of a greater argument instead of the essay.

Function of Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay presents both sides of an issue. However, it presents one side more positively or meticulously than the other one, so that readers could be swayed to the one the author intends. The major function of this type of essay is to present a case before the readers in a convincing manner, showing them the complete picture.

Synonyms of Argumentative Essay

Argumentative Essay synonyms are as follows: persuasive essays, research essays, analytical essays, or even some personal essays.

Related posts:

- Elements of an Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Definition Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Types of Essay

- Analytical Essay

- Cause and Effect Essay

- Critical Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Process Essay

- Explicatory Essay

- An Essay on Man: Epistle I

- Comparison and Contrast Essay

Post navigation

The Dynamic Exploring the Versatile Functions of Muscles

This essay about the multifaceted functions of the muscular system, likening it to a symphony orchestrating movement, stability, metabolism, and expression. From enabling locomotion and maintaining posture to regulating metabolism and facilitating communication, muscles are the unsung heroes of human existence. Through their intricate choreography, muscles transform intention into action with grace and precision, embodying the essence of vitality and resilience. By exploring the dynamic interplay of muscles in various aspects of life, this essay highlights the remarkable capabilities of the human body and underscores the importance of nurturing muscular health for overall well-being.

How it works

Human anatomy is akin to a complex orchestra, with each system harmonizing to orchestrate the symphony of life. Among these, the muscular system stands out as a virtuoso, its multifaceted roles contributing to the seamless rhythm of existence. From the balletic grace of a dancer’s leap to the resolute strength of a weightlifter’s lift, muscles are the maestros of movement, stability, and physiological equilibrium.

One of the paramount functions of the muscular system is locomotion, the graceful ballet of motion that defines human activity.

This orchestration is directed by skeletal muscles, meticulously synchronized to contract and relax, propelling us through space and time. Consider the fluidity of a sprinter’s stride or the delicate precision of a pianist’s fingers; it is the symphony of muscle contractions that choreographs these movements, transforming intention into action with unparalleled finesse.

Yet, beyond its role in locomotion, the muscular system serves as the guardian of stability and posture, ensuring that the human form stands tall amidst the ebb and flow of existence. Postural muscles, steadfast sentinels along the spinal column and pelvis, bear the weight of the body with unwavering strength, defying the pull of gravity. Moreover, the dynamic interplay of muscles around joints serves as a stabilizing force, maintaining equilibrium and preventing injury as we navigate the complexities of everyday life. From the graceful poise of a ballerina en pointe to the unwavering balance of a tightrope walker, it is the muscular system that anchors us to the earth, providing a stable foundation upon which life’s adventures unfold.

In addition to its mechanical prowess, the muscular system is a metabolic powerhouse, fueling the fires of energy production and thermoregulation within the body. Skeletal muscles, with their voracious appetite for fuel, serve as metabolic furnaces, burning calories even at rest. This metabolic activity not only sustains life but also regulates body temperature, generating warmth to fend off the chill of winter’s embrace. Furthermore, through the alchemy of exercise, muscles undergo transformation, sculpting a physique that is both strong and resilient, a testament to the body’s adaptive potential and enduring vitality.

Moreover, the muscular system is a conduit for expression, a canvas upon which emotions are painted and thoughts are articulated. Facial muscles, with their intricate choreography of smiles and frowns, convey a spectrum of emotions that transcend language and culture. Similarly, the muscles of the larynx and tongue perform a delicate dance of phonetics, weaving together the tapestry of speech and communication. Whether through a hearty laugh, a tender embrace, or the eloquence of spoken word, it is the muscular system that enables us to connect, communicate, and express the essence of our being.

In conclusion, the muscular system is a masterpiece of biological engineering, its myriad functions weaving a tapestry of movement, stability, metabolism, and expression that defines the human experience. Like a symphony in motion, muscles orchestrate the dance of life, transforming intention into action with effortless grace and precision. By nurturing the health and vitality of our muscles, we honor the symphony of existence, embracing the rhythms of life with gratitude, resilience, and boundless potential.

Cite this page

The Dynamic Exploring the Versatile Functions of Muscles. (2024, May 12). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-dynamic-exploring-the-versatile-functions-of-muscles/

"The Dynamic Exploring the Versatile Functions of Muscles." PapersOwl.com , 12 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-dynamic-exploring-the-versatile-functions-of-muscles/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Dynamic Exploring the Versatile Functions of Muscles . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-dynamic-exploring-the-versatile-functions-of-muscles/ [Accessed: 12 May. 2024]

"The Dynamic Exploring the Versatile Functions of Muscles." PapersOwl.com, May 12, 2024. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-dynamic-exploring-the-versatile-functions-of-muscles/

"The Dynamic Exploring the Versatile Functions of Muscles," PapersOwl.com , 12-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-dynamic-exploring-the-versatile-functions-of-muscles/. [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Dynamic Exploring the Versatile Functions of Muscles . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-dynamic-exploring-the-versatile-functions-of-muscles/ [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

America’s Colleges Are Reaping What They Sowed

Universities spent years saying that activism is not just welcome but encouraged on their campuses. Students took them at their word.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

N ick Wilson, a sophomore at Cornell University, came to Ithaca, New York, to refine his skills as an activist. Attracted by both Cornell’s labor-relations school and the university’s history of campus radicalism, he wrote his application essay about his involvement with a Democratic Socialists of America campaign to pass the Protecting the Right to Organize Act . When he arrived on campus, he witnessed any number of signs that Cornell shared his commitment to not just activism but also militant protest, taking note of a plaque commemorating the armed occupation of Willard Straight Hall in 1969.

Cornell positively romanticizes that event: The university library has published a “ Willard Straight Hall Occupation Study Guide ,” and the office of the dean of students once co-sponsored a panel on the protest. The school has repeatedly screened a documentary about the occupation, Agents of Change . The school’s official newspaper, published by the university media-relations office, ran a series of articles honoring the 40th anniversary, in 2009, and in 2019, Cornell held a yearlong celebration for the 50th, complete with a commemorative walk, a dedication ceremony, and a public conversation with some of the occupiers. “ Occupation Anniversary Inspires Continued Progress ,” the Cornell Chronicle headline read.

As Wilson has discovered firsthand, however, the school’s hagiographical odes to prior protests have not prevented it from cracking down on pro-Palestine protests in the present. Now that he has been suspended for the very thing he told Cornell he came there to learn how to do—radical political organizing—he is left reflecting on the school’s hypocrisies. That the theme of this school year at Cornell is “Freedom of Expression” adds a layer of grim humor to the affair.

Evan Mandery: University of hypocrisy

University leaders are in a bind. “These protests are really dynamic situations that can change from minute to minute,” Stephen Solomon, who teaches First Amendment law and is the director of NYU’s First Amendment Watch—an organization devoted to free speech—told me. “But the obligation of universities is to make the distinction between speech protected by the First Amendment and speech that is not.” Some of the speech and tactics protesters are employing may not be protected under the First Amendment, while much of it plainly is. The challenge universities are confronting is not just the law but also their own rhetoric. Many universities at the center of the ongoing police crackdowns have long sought to portray themselves as bastions of activism and free thought. Cornell is one of many universities that champion their legacy of student activism when convenient, only to bring the hammer down on present-day activists when it’s not. The same colleges that appeal to students such as Wilson by promoting opportunities for engagement and activism are now suspending them. And they’re calling the cops.

The police activity we are seeing universities level against their own students does not just scuff the carefully cultivated progressive reputations of elite private universities such as Columbia, Emory University, and NYU, or the equally manicured free-speech bona fides of red-state public schools such as Indiana University and the University of Texas at Austin. It also exposes what these universities have become in the 21st century. Administrators have spent much of the recent past recruiting social-justice-minded students and faculty to their campuses under the implicit, and often explicit, promise that activism is not just welcome but encouraged. Now the leaders of those universities are shocked to find that their charges and employees believed them. And rather than try to understand their role in cultivating this morass, the Ivory Tower’s bigwigs have decided to apply their boot heels to the throats of those under their care.

I spoke with 30 students, professors, and administrators from eight schools—a mix of public and private institutions across the United States—to get a sense of the disconnect between these institutions’ marketing of activism and their treatment of protesters. A number of people asked to remain anonymous. Some were untenured faculty or administrators concerned about repercussions from, or for, their institutions. Others were directly involved in organizing protests and were wary of being harassed. Several incoming students I spoke with were worried about being punished by their school before they even arrived. Despite a variety of ideological commitments and often conflicting views on the protests, many of those I interviewed were “shocked but not surprised”—a phrase that came up time and again—by the hypocrisy exhibited by the universities with which they were affiliated. (I reached out to Columbia, NYU, Cornell, and Emory for comment on the disconnect between their championing of past protests and their crackdowns on the current protesters. Representatives from Columbia, Cornell, and Emory pointed me to previous public statements. NYU did not respond.)

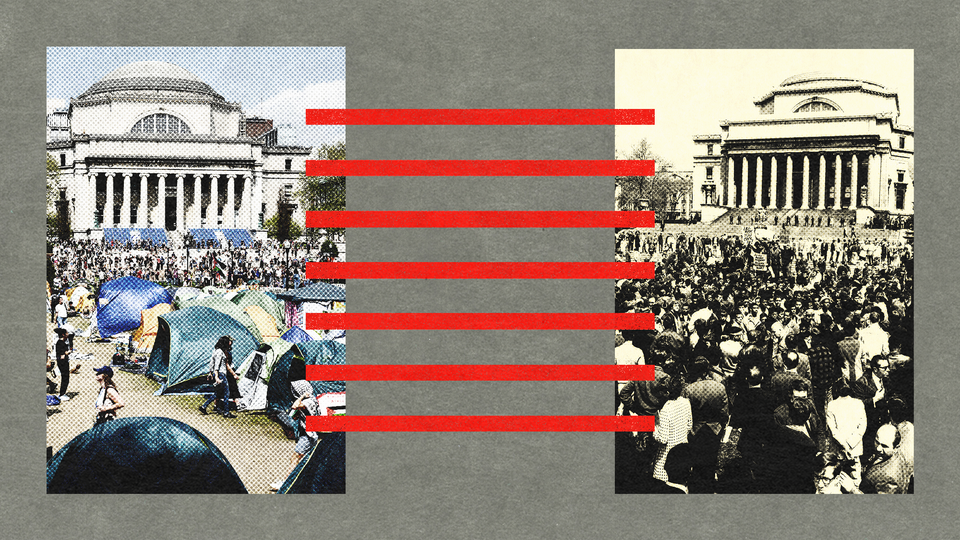

The sense that Columbia trades on the legacy of the Vietnam protests that rocked campus in 1968 was widespread among the students I spoke with. Indeed, the university honors its activist past both directly and indirectly, through library archives , an online exhibit , an official “Columbia 1968” X account , no shortage of anniversary articles in Columbia Magazine , and a current course titled simply “Columbia 1968.” The university is sometimes referred to by alumni and aspirants as the “Protest Ivy.” One incoming student told me that he applied to the school in part because of an admissions page that prominently listed community organizers and activists among its “distinguished alumni.”

Joseph Slaughter, an English professor and the executive director of Columbia’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights, talked with his class about the 1968 protests after the recent arrests at the school. He said his students felt that the university had actively marketed its history to them. “Many, many, many of them said they were sold the story of 1968 as part of coming to Columbia,” he told me. “They talked about it as what the university presents to them as the long history and tradition of student activism. They described it as part of the brand.”

This message reaches students before they take their first college class. As pro-Palestine demonstrations began to raise tensions on campus last month, administrators were keen to cast these protests as part of Columbia’s proud culture of student activism. The aforementioned high-school senior who had been impressed by Columbia’s activist alumni attended the university’s admitted-students weekend just days before the April 18 NYPD roundup. During the event, the student said, an admissions official warned attendees that they may experience “disruptions” during their visit, but boasted that these were simply part of the school’s “long and robust history of student protest.”

Remarkably, after more than 100 students were arrested on the order of Columbia President Minouche Shafik—in which she overruled a unanimous vote by the university senate’s executive committee not to bring the NYPD to campus —university administrators were still pushing this message to new students and parents. An email sent on April 19 informed incoming students that “demonstration, political activism, and deep respect for freedom of expression have long been part of the fabric of our campus.” Another email sent on April 20 again promoted Columbia’s tradition of activism, protest, and support of free speech. “This can sometimes create moments of tension,” the email read, “but the rich dialogue and debate that accompany this tradition is central to our educational experience.”

Evelyn Douek and Genevieve Lakier: The hypocrisy underlying the campus-speech controversy

Another student who attended a different event for admitted students, this one on April 21, said that every administrator she heard speak paid lip service to the school’s long history of protest. Her own feelings about the pro-Palestine protests were mixed—she said she believes that a genocide is happening in Gaza and also that some elements of the protest are plainly anti-Semitic—but her feelings about Columbia’s decision to involve the police were unambiguous. “It’s reprehensible but exactly what an Ivy League institution would do in this situation. I don’t know why everyone is shocked,” she said, adding: “It makes me terrified to go there.”

Beth Massey, a veteran activist who participated in the 1968 protests, told me with a laugh, “They might want to tell us they’re progressive, but they’re doing the business of the ruling class.” She was not surprised by the harsh response to the current student encampment or by the fact that it lit the fuse on a nationwide protest movement. Massey had been drawn to the radical reputation of Columbia’s sister school, Barnard College, as an open-minded teenager from the segregated South: “I actually wanted to go to Barnard because they had a history of progressive struggle that had happened going all the way back into the ’40s.” And the barn-burning history that appealed to Massey in the late 1960s has continued to attract contemporary students, albeit with one key difference: Today, that radical history has become part of the way that Barnard and Columbia sell their $60,000-plus annual tuition.

Of course, Columbia is not alone. The same trends have also prevailed at NYU, which likes to crow about its own radical history and promises contemporary students “ a world of activism opportunities .” An article published on the university’s website in March—titled “Make a Difference Through Activism at NYU”—promises students “myriad chances to put your activism into action.” The article points to campus institutions that “provide students with resources and opportunities to spark activism and change both on campus and beyond.” The six years I spent as a graduate student at NYU gave me plenty of reasons to be cynical about the university and taught me to view all of this empty activism prattle as white noise. But even I was astounded to see a video of students and faculty set upon by the NYPD, arrested at the behest of President Linda Mills.

“Across the board, there is a heightened awareness of hypocrisy,” Mohamad Bazzi, a journalism professor at NYU, told me, noting that faculty were acutely conscious of the gap between the institution’s intensive commitment to DEI and the police crackdown. The university has recently made several “cluster hires”—centered on activism-oriented themes such as anti-racism, social justice, and indigeneity—that helped diversify the faculty. Some of those recent hires were among the people who spent a night zip-tied in a jail cell, arrested for the exact kind of activism that had made them attractive to NYU in the first place. And it wasn’t just faculty. The law students I spoke with were especially acerbic. After honing her activism skills at her undergraduate institution—another university that recently saw a violent police response to pro-Palestine protests—one law student said she came to NYU because she was drawn to its progressive reputation and its high percentage of prison-abolitionist faculty. This irony was not lost on her as the police descended on the encampment.

After Columbia students were arrested on April 18, students at NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study decided to cancel a planned art festival and instead use the time to make sandwiches as jail support for their detained uptown peers. The school took photos of the students layering cold cuts on bread and posted it to Gallatin’s official Instagram. These posts not only failed to mention that the students were working in support of the pro-Palestine protesters; the caption—“making sandwiches for those in need”—implied that the undergrads might be preparing meals for, say, the homeless.

The contradictions on display at Cornell, Columbia, and NYU are not limited to the state of New York. The police response at Emory, another university that brags about its tradition of student protest, was among the most disturbing I have seen. Faculty members I spoke with at the Atlanta school, including two who had been arrested—the philosophy professor Noëlle McAfee and the English and Indigenous-studies professor Emil’ Keme—recounted harrowing scenes: a student being knocked down, an elderly woman struggling to breathe after tear-gas exposure, a colleague with welts from rubber bullets. These images sharply contrast with the university’s progressive mythmaking, a process that was in place even before 2020’s “summer of racial reckoning” sent universities scrambling to shore up their activist credentials.

In 2018, Emory’s Campus Life office partnered with students and a design studio to begin work on an exhibit celebrating the university’s history of identity-based activism. Then, not long after George Floyd’s murder, the university’s library released a series of blog posts focusing on topics including “Black Student Activism at Emory,” “Protests and Movements,” “Voting Rights and Public Policy,” and “Authors and Artists as Activists.” That same year, the university announced its new Arts and Social Justice Fellows initiative, a program that “brings Atlanta artists into Emory classrooms to help students translate their learning into creative activism in the name of social justice.” In 2021, the university put on an exhibit celebrating its 1969 protests , in which “Black students marched, demonstrated, picketed, and ‘rapped’ on those institutions affecting the lives of workers and students at Emory.” Like Cornell’s and Columbia’s, Emory’s protests seem to age like fine wine: It takes half a century before the institution begins enjoying them.

N early every person I talked with believed that their universities’ responses were driven by donors, alumni, politicians, or some combination thereof. They did not believe that they were grounded in serious or reasonable concerns about the physical safety of students; in fact, most felt strongly that introducing police into the equation had made things far more dangerous for both pro-Palestine protesters and pro-Israel counterprotesters. Jeremi Suri, a historian at UT Austin—who told me he is not politically aligned with the protesters—recalls pleading with both the dean of students and the mounted state troopers to call off the charge. “It was like the Russian army had come onto campus,” Suri mused. “I was out there for 45 minutes to an hour. I’m very sensitive to anti-Semitism. Nothing anti-Semitic was said.” He added: “There was no reason not to let them shout until their voices went out.”

From the May 1930 issue: Hypocrisy–a defense

As one experienced senior administrator at a major research university told me, the conflagration we are witnessing shows how little many university presidents understand either their campus communities or the young people who populate them. “When I saw what Columbia was doing, my immediate thought was: They have not thought about day two ,” he said, laughing. “If you confront an 18-year-old activist, they don’t back down. They double down.” That’s what happened in 1968, and it’s happening again now. Early Tuesday morning, Columbia students occupied Hamilton Hall—the site of the 1968 occupation, which they rechristened Hind’s Hall in honor of a 6-year-old Palestinian girl killed in Gaza—in response to the university’s draconian handling of the protests. They explicitly tied these events to the university’s past, calling out its hypocrisy on Instagram: “This escalation is in line with the historical student movements of 1968 … which Columbia repressed then and celebrates today.” The university, for its part, responded now as it did then: Late on Tuesday, the NYPD swarmed the campus in an overnight raid that led to the arrest of dozens of students.

The students, professors, and administrators I’ve spoken with in recent days have made clear that this hypocrisy has not gone unnoticed and that the crackdown isn’t working, but making things worse. The campus resistance has expanded to include faculty and students who were originally more ambivalent about the protests and, in a number of cases, who support Israel. They are disturbed by what they rightly see as violations of free expression, the erosion of faculty governance, and the overreach of administrators. Above all, they’re fed up with the incandescent hypocrisy of institutions, hoisted with their own progressive petards, as the unstoppable force of years’ worth of self-righteous rhetoric and pseudo-radical posturing meets the immovable object of students who took them at their word.

In another video published by The Cornell Daily Sun , recorded only hours after he was suspended, Nick Wilson explained to a crowd of student protesters what had brought him to the school. “In high school, I discovered my passion, which was community organizing for a better world. I told Cornell University that’s why I wanted to be here,” he said, referencing his college essay. Then he paused for emphasis, looking around as his peers began to cheer. “And those fuckers admitted me.”

Please rotate your device

We don't support landscape mode yet. Please go back to portrait mode for the best experience

The new book of jobs: How India Inc. is navigating through a changing work environment

- Byline: Krishna Gopalan

- Producer: Arnav Das Sharma

Companies are scrambling to meet the demands of the disruptive post-pandemic business environment. They are creating new functions even as they confront a huge change in the composition of the workforce

For the past two years, Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL) has gone to business schools specifically looking for graduates inclined towards digital commerce. That’s nothing unusual, except that traditional sales and marketing functions have made way for new job descriptions. It indicates a changing India where many opportunities have forced companies regardless of size to look for talent but with a difference, and this comes forth in the BT -Taggd survey of The Best Companies to Work For in India this year.

Just what is the change? Today’s talent—and there’s plenty of that in India—is looking for a new set of challenges and new-age roles. For them, a sales and marketing job is passé. For instance, HUL has created the position of e-commerce manager. Large FMCG companies see around 10% of their revenues in the digital age coming from e-commerce channels, and even the most conservative estimates suggest the number could touch 30% by the end of the decade. Besides, every company recognises the need to have a closer look at their business. That has led to the creation of new positions, with clear job descriptions.

“All this is in line with the change we are bringing about in each of our businesses,” says Anuradha Razdan, Executive Director (HR) and CHRO, HUL & Unilever South Asia.

This process will test the mettle of the best companies as the workforce gets reoriented across levels.

“ At senior management levels, we are seeing a greater focus on reskilling with a robust understanding of tech. It is pushing them to focus a lot more on cognitive, EQ and leadership skills ” DEEPTI SAGAR Chief People and Experience Officer Deloitte India

Redefining Roles

This change is recent. Around a decade ago, any large organisation had a defined set of positions. There was a CFO, a CHRO, a CMO, a COO and, of course, a CEO. “Today, a Chief Data Officer or a Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) are realities,” says Aditya Narayan Mishra, MD & CEO of recruitment and staffing services firm CIEL HR. Apart from talent wanting new-age roles, they also see the need to specialise in one area, he adds.

Earlier, only a CTO would suffice; but in several companies there is a need for a CISO as well. “In a lot of industries, data protection is an important piece and a part of the overall boardroom agenda. A generalist may not fit the bill here in an age of such a specialised need,” explains Mishra.

Speaking of new-age sectors—such as companies in the tech space—finance is a key role. Mishra points out that these firms tend to have a Chief Accounting Officer as well as a CFO. “For these companies, fundraising is a big part of their overall business. A CFO may be very good with a treasury function, but this is a very different requirement.”

Likewise, a CHRO is now complemented by a Chief Talent Officer, who looks after the employer brand and areas related to talent management but will not oversee, say, issues related to payroll.

Digitisation has expedited the extent to which technology dominates business functions in a post-pandemic world. The consensus among experts is that what would have taken a decade to change, has happened in less than two years. The thrust on AI and its impact on our lives has been profound and the stage is set for an extremely dynamic future.

Deepti Sagar, Chief People and Experience Officer at consultancy Deloitte India, says job profiles across levels at her organisation are being driven by technological disruptions, economic advances, and a progressive business ecosystem.