5 ways to strengthen our health systems for the future

New possibilities are emerging to ensure stronger, more resilient health systems for the future. Image: REUTERS/Ajeng Dinar Ulfiana

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Genya Dana

Kelly mccain, matthew oliver.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Global Health is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, healthy futures.

Listen to the article

- Health systems around the world have been hit hard by the pandemic, with 90% of countries reporting disruptions to essential health services.

- As we get back on track, new possibilities are emerging to address a wide range of health issues.

- Through data and technology, along with the co-creation of health services with communities and new entrants in the health and healthcare field, we have the potential to transform healthcare for the future.

In September 2019, a group of experts working together as part of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) published a report stating that the world was grossly unprepared for a lethal respiratory pathogen pandemic like what the world faced in 1918 with influenza. The cost to the modern economy of such a pandemic, they reported, could be up to $3 trillion.

The GPMB’s estimates, it turned out, were far too conservative.

The IMF in October 2021 projected that the cost to the global economy of the COVID-19 pandemic, until 2024, would be around $ 12.5 trillion . The Economist described the economic impact as “incalculable”. The toll on human health is greater still.

Health systems face enormous challenges as they seek to recover from the pandemic. Efforts to eliminate HIV, TB, malaria and hepatitis have been set back decades, while 23 million children missed basic vaccines in 2020, an increase of nearly 20% on the previous year. Waiting times for diagnosis and treatment of cancer have spiralled in many parts of the world. Further out, an aging global population means that by 2050, 1 in 6 individuals will be over the age of 65 , making a resilient health system all the more critical.

How can we possibly hope to deal with any one of these seemingly intractable challenges – let alone find solutions to them all?

5 common themes for the future of health systems

The World Economic Forum’s Health and Healthcare Platform works with stakeholders from private industry, governments, academics, civil society and patient advocates on a wide range of health issues from hepatitis and tuberculosis , to cancer and diabetes , and a number of cross-cutting initiatives. Across the breadth of these issues, we see five common themes that we believe have the potential to transform how healthcare works in the future, and ensure for stronger, more resilient health systems globally.

1. There’s a new appreciation of the importance of health.

Late last year, Dr. Tedros Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), said: “The time has come for a new narrative that sees health not as a cost, but an investment that is the foundation of productive, resilient and stable economies.”

That is exactly what we have seen from our partners. On an unprecedented scale, companies want to be engaged in matters relating to health. From the C-suite down deep into supply chains, there is a recognition that health underpins wealth – and nearly everyone is keen to play a part. We’ve seen new partnerships brokered outside of the health and healthcare industry, such as DP World – a leader in global end-to-end supply chain logistics headquartered in the United Arab Emirates – partnering with UNICEF to support the global distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and critical immunization supplies in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

2. Improving the health system means supporting the local community.

The pandemic saw health services delivered in the community in an unprecedented way through the deployment of mobile testing units and pop-up vaccination centres. In the US, the YMCA partnered with CVS Health to establish vaccination sites in communities in six cities without pharmacy access to help ensure more equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. This trend will continue, making access to care easier, more local (including in workplaces ) and more affordable, in addition to freeing up critical resources within health systems to manage emergent care.

3. The global health workforce needs care, too.

COVID-19 exacerbated the global shortage of healthcare workers and the challenges they face. In the US alone, nearly 1 in 5 healthcare workers quit their jobs during the pandemic. With women representing 70% of the healthcare workforce, gender-based policies are needed to protect and support them. We must replace aging healthcare workforces, and care for our healthcare professionals traumatized by the pandemic. Healthcare should be reimagined based on the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic – and healthcare workers should be leading health policy work.

4. Deployment of novel technologies in the health system is critical.

A range of new technologies are starting to reach mainstream use, promising to make care more equitable and cheaper. From a collaboration by Pfizer, BioNTech and Zipline for long-range drone delivery of COVID-19 vaccines requiring ultra-cold-chain in Ghana, to the use of AI to diagnose lung conditions via X-ray, to the breakthrough use of mRNA technology and the promise it represents in fighting other challenging health conditions , exciting novel technologies can make care cheaper, more effective and more equitable.

5. A new age of diagnostics has begun.

Before the pandemic, many who worked in diagnostics felt that their contributions were undervalued. Now, everyone understands the importance of testing, with “PCRs”, “lateral flows”, “antigens” and “antibodies” becoming part of daily language. At the outset of the pandemic, only two countries in Africa could screen for coronaviruses; now, nearly all can. This carries hope for finding the “missing millions” in HIV, TB, malaria and hepatitis. There’s a new focus on genomic sequencing and the importance of sentinel surveillance. The pandemic has also shown that health data can be collected in real-time from all over the world. With more, earlier testing, we can catch health conditions sooner and get better health outcomes.

The application of “precision medicine” to save and improve lives relies on good-quality, easily-accessible data on everything from our DNA to lifestyle and environmental factors. The opposite to a one-size-fits-all healthcare system, it has vast, untapped potential to transform the treatment and prediction of rare diseases—and disease in general.

But there is no global governance framework for such data and no common data portal. This is a problem that contributes to the premature deaths of hundreds of millions of rare-disease patients worldwide.

The World Economic Forum’s Breaking Barriers to Health Data Governance initiative is focused on creating, testing and growing a framework to support effective and responsible access – across borders – to sensitive health data for the treatment and diagnosis of rare diseases.

The data will be shared via a “federated data system”: a decentralized approach that allows different institutions to access each other’s data without that data ever leaving the organization it originated from. This is done via an application programming interface and strikes a balance between simply pooling data (posing security concerns) and limiting access completely.

The project is a collaboration between entities in the UK (Genomics England), Australia (Australian Genomics Health Alliance), Canada (Genomics4RD), and the US (Intermountain Healthcare).

COVID-19 has generated an opportunity for stakeholders – from the public and private sectors, to governments, to communities – to reimagine collaboration in the pursuit of more sustainable, equitable and resilient health systems. Through more strategic use of data and technology, along with the co-creation of health services with communities and new entrants in the health and healthcare field, we have the opportunity to enable our health and healthcare systems to learn, adapt and prepare for a future that is sure to come.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Forum Institutional .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Day 2 #SpecialMeeting24: Key insights and what to know

Gayle Markovitz

April 28, 2024

Day 1 #SpecialMeeting24: Key insights and what just happened

April 27, 2024

#SpecialMeeting24: What to know about the programme and who's coming

Mirek Dušek and Maroun Kairouz

Climate finance: What are debt-for-nature swaps and how can they help countries?

Kate Whiting

April 26, 2024

What to expect at the Special Meeting on Global Collaboration, Growth and Energy for Development

Spencer Feingold and Gayle Markovitz

April 19, 2024

From 'Quit-Tok' to proximity bias, here are 11 buzzwords from the world of hybrid work

April 17, 2024

All Content

10 strategies for delivering a great presentation.

- Justin Roesch, MD;

- Patrick A. Rendon, MD

It’s noon on Tuesday, and James, a new PGY-2 resident, begins his presentation on COPD. After five minutes, you notice half of the residents playing Words with Friends, the “ortho-bound” medical student talking with a buddy in the back, and the attendings looking on with innate skepticism.

Dr. Patrick A. Rendon

Your talk on atrial fibrillation is next month, and just watching James brings on palpitations of your own. So what do you do?

Introduction

Public speaking is a near certainty for most of us regardless of training stage. A well-executed presentation establishes the clinician as an institutional authority, adroitly educating anyone around you.

Dr. Justin Roesch

So how can you deliver that killer update on atrial fibrillation? Here, we provide you with 10 tips for preparing and delivering a great presentation.

Preparation

1. Consider the audience and what they already know. No matter how interesting we think we are, if we don’t present with the audience’s needs in mind, we might as well be talking to an empty room. Consider what the audience may or may not know about the topic; this allows you to decide whether to give a comprehensive didactic on atrial fibrillation for trainees or an anticoagulation update for cardiologists. Great presenters survey their audience early on with a question such as, “How many of you here know the results of the AFFIRM trial?” This allows you to make small alterations to meet the needs of your audience.

2. Visualize the stage and setting. Understanding the stage helps you anticipate and address barriers to learning. Imagine for a moment the difference in these two scenarios: a discussion of hyponatremia with a group of medical students at 4 p.m. in a dark room versus a discussion on principles of atrial fibrillation management at 11 a.m. in an auditorium. Both require interaction, although an auditorium-based presentation requires testing your audio-visual equipment in advance.

3. Determine your objectives. To determine your objectives, begin with the end in mind. If you were to visualize your audience members at the end of the talk, what would they know (knowledge), be able to do (behavior), or have a new outlook on (attitude)? The objectives will determine the content you deliver and the activities for learning. For a one-hour presentation, identifying three to five objectives is a good rule of thumb.

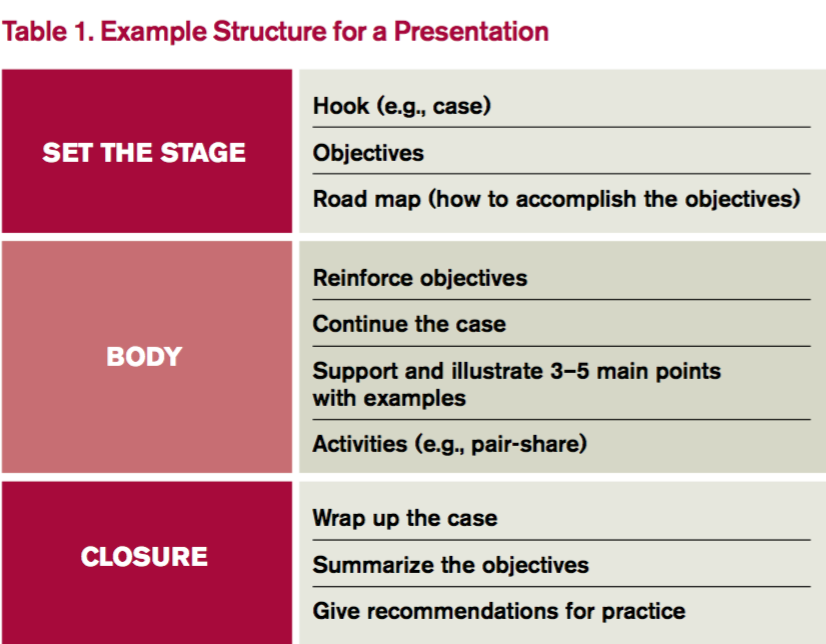

4. Build your presentation. Whether using PowerPoint, Prezi, or a white board, “build” the presentation from the objectives. Table 1 outlines one example format; Figure 1 outlines some best practices of PowerPoint.

Humans evolved to interpret visual imagery, not read text, so try to use pictures instead of bullet points. Consider first building slides with text and then using an internet search engine to convert words to pictures. For example, “atrial rate 200 bpm” is better displayed with an actual ECG.

5. Practice. Practicing helps you become more comfortable with the content itself as well as how to present that content. If you can, practice with a colleague and receive feedback to sharpen your material. No time to spare? Practice the introduction and any major point that you want to get across. Audiences decide within the first five minutes whether your talk is worth listening to before pulling out their cellphones to open up Facebook.

1. Confront nervousness. Many of us become nervous when speaking in front of an audience. To address this, it’s perfectly reasonable to rehearse a presentation at home or in a quiet call room ahead of time. If you feel extremely nervous, breathe deeply for five- to 10-second intervals. During the presentation itself, find friendly or familiar faces in the audience and look them in the eyes as you speak. This eases nerves and improves your technique.

Share:

Comment on this article cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Undergraduate Program

- Overview and Welcome

- How Do I Apply?

- Our Degrees

- Research and Internships

Improving the health system and providing better healthcare

- Adopting healthier lifestyles - more exercise, checkups, and health screenings

- Disaster preparedness

- Public Health Society (PHS)

Primary-care doctors, specialists, hospitals, community health clinics – all provide care to people in need. We can make big improvements in the health of the most vulnerable people in our communities by helping everyone get better access to healthcare, improving the quality of the care they receive and making sure it is provided at a reasonable price. But doing so is not easy, and requires addressing a number of challenging questions, including:

- Why does the structure of the U.S. health system contributes to increased health disparities and what can be done to reduce those disparities?

- Why does the U.S. system costs so much compared to the rest of the world and what can be done to lower costs?

- Why are there variations across hospitals and regions in the type and quality of care people receive, and what can we do to ensure everyone has access to quality services?

The field of h ealth services research (HSR) addresses all these issues. HSR examines how people get access to healthcare, how much care costs and what happens to patients as a result of this care.

The main goals of health services research are to identify the most effective ways to organize, manage, finance and deliver high-quality care; reduce medical errors; and improve patient safety (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2002). HSR tends to be multidisciplinary, and with researchers coming from a variety of disciplines, including:

- Clinical fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry and allied health

- Social and behavioral sciences

- Human factors engineering

- Epidemiology and biostatistics

- Multidisciplinary perspectives from healthcare policy, research, administration and management

Health services researchers investigate how various factors — including social forces, financing mechanisms, organizational processes and structures, evolving health technologies and individual behavior — act separately and together to affect the delivery of healthcare and, ultimately, the health and well being of people.

They pursue careers in many settings, including academia, professional organizations, health policy groups, clinical settings, and in federal, state and local agencies. Examples of topics explored by HSR include:

Additional Links

- Executive Leadership

- University Library

- School of Engineering

- School of Natural Sciences

- School of Social Sciences, Humanities & Arts

- Ernest & Julio Gallo Management Program

- Division of Graduate Education

- Division of Undergraduate Education

Administration

- Office of the Chancellor

- Office of Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost

- Equity, Justice and Inclusive Excellence

- External Relations

- Finance & Administration

- Physical Operations, Planning and Development

- Student Affairs

- Research and Economic Development

- Office of Information Technology

University of California, Merced 5200 North Lake Rd. Merced, CA 95343 Telephone: (209) 228-4400

- © 2024

- About UC Merced

- Privacy/Legal

- Site Feedback

- Accessibility

'Improve health systems' presentation slideshows

Improve health systems - powerpoint ppt presentation.

eHealth: Global perspective

eHealth: Global perspective. S. Yunkap Kwankam Coordinator eHealth World Health Organization, Geneva. Outline of presentation. Six point agenda and health system framework WHO eHealth priorities WHO collaboration mechanisms Conclusion.

514 views • 34 slides

View Improve health systems PowerPoint (PPT) presentations online in SlideServe. SlideServe has a very huge collection of Improve health systems PowerPoint presentations. You can view or download Improve health systems presentations for your school assignment or business presentation. Browse for the presentations on every topic that you want.

Public Health Systems & Best Practices

Protecting the public's health depends on strengthening the public health system and implementing proven strategies to improve health outcomes.

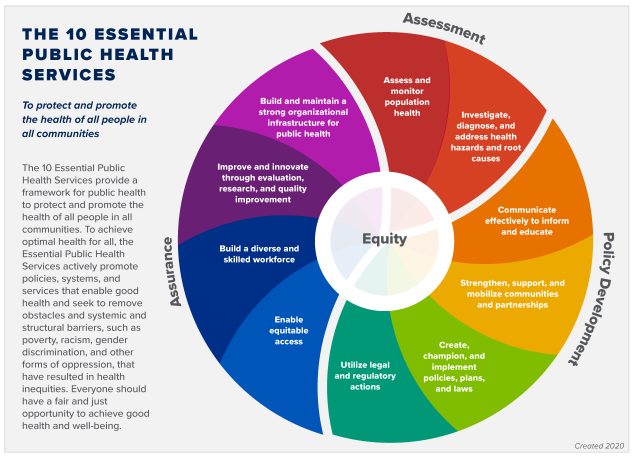

The 10 Essential Public Health Services (EPHS) describe the public health activities that all communities should undertake. On September 9, 2020, a revised EPHS framework and graphic was released. The revised EPHS is intended to bring the framework in line with current and future public health practice.

Social determinants of health describe conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes. Differences in these conditions lead to health inequities.

In partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, CDC is supporting the implementation of a national voluntary accreditation program for state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments.

- Accredited Health Departments

Public health governance varies from state to state, as do the relationships between state and regional or local agencies. Explore this page to determine how agencies collaborate to protect the public’s health in your state.

In public health settings, performance and quality tools are being promoted and supported as an opportunity to increase the effectiveness of public health agencies, systems, and services.

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- ACS Foundation

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- ACS Archives

- Careers at ACS

- Federal Legislation

- State Legislation

- Regulatory Issues

- Get Involved

- SurgeonsPAC

- About ACS Quality Programs

- Accreditation & Verification Programs

- Data & Registries

- Standards & Staging

- Membership & Community

- Practice Management

- Professional Growth

- News & Publications

- Information for Patients and Family

- Preparing for Your Surgery

- Recovering from Your Surgery

- Jobs for Surgeons

- Become a Member

- Media Center

Our top priority is providing value to members. Your Member Services team is here to ensure you maximize your ACS member benefits, participate in College activities, and engage with your ACS colleagues. It's all here.

- Membership Benefits

- Find a Surgeon

- Find a Hospital or Facility

- Quality Programs

- Education Programs

- Member Benefits

- Resources in Surgical Educ...

- RISE Articles

- Six Steps to Engage Reside...

Six Steps to Engage Residents in Quality Improvement Education

Neha R. Malhotra, MD; Ashley Vavra, MD; Robert E. Glasgow, MD; Brigitte K. Smith, MD

January 1, 2020

Health care systems are becoming increasingly complex and the United States continues to lag behind other industrialized nations in health outcomes relative to the amount spent. 1–2 We owe it to our patients to foster innovation and improve delivery of care. To do this, we must engage our students, residents, and fellows to understand, develop, and, ultimately, lead the movement to improve quality in health care.

This RISE article reviews the basic tenets of quality in health care and the importance of these concepts to the practice of surgery in the current health care system. We discuss barriers to effective quality improvement (QI) education, including the difference between QI and research. Finally, we outline key components for success when designing QI curricula for trainees so that they are prepared to work within complex systems of care and to make significant contributions to improving the quality of care they provide to their patients.

Establishing a Shared Mental Model of Health Care Quality

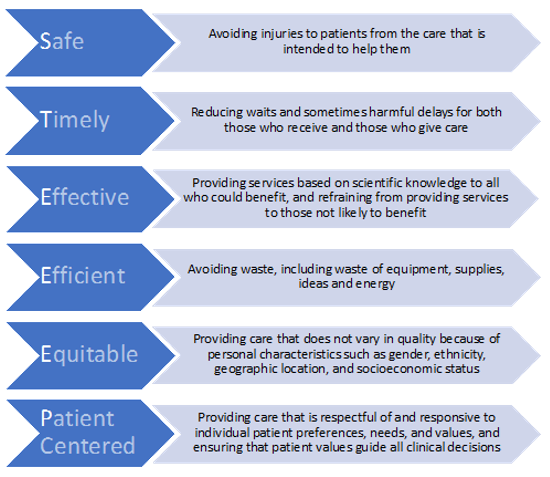

Twenty years ago, the Institute of Medicine’s landmark publication, Crossing the Quality Chasm , helped define critical disparities between the current and ideal state of quality health care in the United States (Figure 1). 2 Since then, health care practitioners are increasingly being evaluated based on the quality of care they provide. As a result, health care has evolved from quality assurance to QI, where defects are examined in order to implement change and prevent errors. 3 Surgeons today need to be capable of interventions that will achieve sustained improvement in the quality of surgical care. It is essential the principles of QI and health systems thinking be incorporated into training for students and residents. Effective educational programs in QI are needed to enable trainees to achieve competency targets and enter the workforce prepared to actively improve the quality of surgical care delivery in their own practice and local institution. 4–6

Challenges and Barriers

Developing effective approaches for teaching QI principles and methodology can be challenging. It is further complicated by the lack of consensus around the definition of quality and how QI differs from research. While both research and QI are essential to ensuring high-quality health care, there are several distinct features of QI that must be recognized and defined.

QI vs Research: What’s the Difference?

Simply stated, QI involves improving processes of care, while research seeks to improve clinical evidence. The main goals of health services research (HSR) are to identify the most effective ways to organize, manage, finance, and deliver high-quality care, reduce medical errors, and improve patient safety. Similarly, outcomes research seeks to understand the factors in health care delivery that are primarily responsible for differential results, such as mortality or quality of life. 7

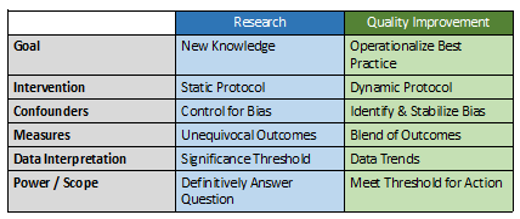

HSR and outcomes research share features common to all research: biases are carefully controlled for using randomization, unequivocal outcomes are measured and significance thresholds are set, classic biostatistics are utilized to analyze data at the end of the project, and the work is powered to definitively answer a question. QI, on the other hand, seeks to operationalize best practices with a series of small changes. Data need only be sufficient to meet confidence thresholds for action or decision, are analyzed in real-time, and trends influence next steps (Table 1).

Table 1. The differences between research and quality improvement

In order to design effective QI interventions, surgeons must be knowledgeable about the factors that influence the outcome of interest—the HSR and outcomes literature. QI interventions are based on knowledge generated from research, but the process of QI does not itself follow the tenets of research. Practice guidelines and standards derived from research often take years to reach implementation, while QI efforts are held to a more immediate and actionable time frame. For QI interventions to be successful, surgeons must also understand and apply principles of change management and team leadership. Change management is the science of preparing and supporting individuals and teams in the face of implementing new concepts, programs, and routines. Understanding these differences is a critical first step to help surgical educators set expectations for resident-led QI projects.

Barriers to Resident Engagement

Engaging residents in meaningful QI efforts is a significant challenge for surgical educators. Residents across specialties have struggled with overload and the challenge of adding yet another component to their curriculum, as well as lack of a shared vision for how to conduct QI and poor clarity of curricular content. 8 Residents have expressed frustration with contributing to improving local health care systems without feeling that their efforts are acknowledged or valued. Educators must address these barriers if QI curricula are to be successful.

Optimizing QI Education in Surgical Residencies

The conditions and contexts for learning are critical to the development and outcomes of QI curricula, as QI efforts occur within the clinical setting of increasingly complex health care systems. Conditions for learning include the content of the curriculum, instructional methods, learning sites, faculty, time, facilities, and health care teams and systems. Contexts for learning include faculty role-modeling, institutional values, culture and politics, and socio-political-economic forces. 9 The six tips that follow incorporate and address issues within this framework.

Establish a Formal Curriculum

While we acknowledge that many programs struggle with limited resources to expand existing curricula, the importance of establishing a complete curriculum, including goals, objectives, and assessment of learning outcomes, cannot be overstated. Residents across specialties have expressed confusion about what is being taught, what is expected of them for participation and outcomes, and the purpose of learning QI. 8 Providing clarity through a comprehensive curriculum is the first step to addressing these barriers. We have found that formalizing a program for learning QI skills helps to mitigate the sense that QI projects are simply checking a box. Rather, residents should know that they are learning a valuable skill set that they will use in their future practice. Additionally, our experience suggests residents are more likely to view QI curricula positively and engage in the when institutional and departmental leadership, program directors and other faculty show explicit support. The American College of Surgeons Quality in Training Initiative Primer is an excellent curricular resource that can be readily implemented within surgical residency programs. 10

Optimize Instructional Methods

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Open School online modules are a popular instructional method to deliver core content on QI to residents 11 ; however, for curricula on QI principles and their application to be effective, instructional methods must go beyond online modules. Experts in medical education and adult learning principles have suggested that a combination of didactic and experiential learning is the optimal approach to effective instruction in QI. 12 The didactic component of the curriculum should provide clarity on the concept of quality, identify differences between QI and research, and outline practical steps for leading QI initiatives. Online modules are excellent resources to deliver content, however, in-person discussions are critical to ensuring improved quality and safety are adopted as lifelong goals, rather than just a box to be checked.

Once residents haven a proven understanding of the QI curriculum, they must “show how,” by demonstrating knowledge and competence in practice by leading QI projects. 13 In our experience, the primary focus of QI project involvement should be learning and practicing the principles, not project outcomes. QI work is messy and fraught with barriers and challenges, many of which are out of the control of the average resident. Therefore, understanding fundamental QI principles with ongoing engagement in QI should be the goal.

Address Institutional Culture and Values

Management guru, Peter Drucker, is attributed as saying, “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” This is as true in establishing effective QI curricula as in the business sector. The most well-considered QI curriculum will miss the mark if institutional culture surrounding QI is not identified and addressed. The values of the institution influence residents’ ability to implement change through QI processes. Furthermore, Adult Learning Theory posits that residents will learn best when they see a need to acquire knowledge and skills in a particular domain. 14 This suggests that residents are unlikely to develop an intrinsic motivation to learn and apply QI skills without appropriate faculty role modeling of its importance. Changes in culture come from the top and it is critical to engage high level stakeholders when implementing a QI program. By engaging senior leadership first, the culture of quality will permeate all aspects of resident training, not just the siloed QI curriculum.

Support Faculty QI Champions

Our current trainees are faced with mandates to learn something for which there are exceedingly few teachers and even fewer experts. 15 For any QI curricula to succeed, faculty development is critical. (See Appendix for opportunities for advanced training in quality improvement and patient safety.) Residents should have the opportunity to interact with a faculty champion or curriculum director as they learn foundational principles, as well as a faculty coach or mentor as they work through a QI project. Educational leaders in QI have suggested that resident projects fail for two reasons: (1) burnout of the few faculty who are qualified to coach projects, and (2) lack of faculty engagement to ensure QI project success. 16 Interested faculty should be identified and encouraged to obtain training in QI through a variety of certificate programs that are now available institutionally and nationally. 16–19 Finally, QI principles are universal across specialties and health care professions, so seeking teachers and coaches outside of the department of surgery is an important avenue to consider.

Integrate and Align with the Hospital System

Hospital operations and graduate medical education (GME) alignment need to be addressed to support QI curriculum development and implementation. Implementation of effective QI curricula requires access to infrastructure and resources such as data, project management, IT support, and process improvement expertise, which are likely to reside within clinical operations. A QI initiative is more likely to gain access to these resources if it falls in line with the hospital’s strategic priorities, particularly if the resident is able to present a business case that estimates savings for the institution. However, GME and clinical operations leadership and their missions typically exist in silos and are not routinely aligned. In order to improve alignment, residents are encouraged to develop relationships with hospital quality leaders. GME-wide house staff councils are one way to facilitate this. 20 Appointing resident representatives to institutional QI councils and committees can also improve communication and collaboration between residents and hospital leaders. 21 Projects that are derived from partnership with the hospital are also more likely to affect day-to-day experience of those involved and can increase engagement of residents and faculty who are able to see the problem and results of their efforts in real time.

Celebrate Successes and Make QI Efforts Visible

Celebrating resident QI efforts is critical to achieve buy-in from the residents and promote success of the QI curriculum. Residents should be given the opportunity to share their work at conferences, such as grand rounds. 22 The University of Utah has established an annual Department Value Symposium where residents present abstracts of their QI work and a keynote speaker is invited, similar to resident research days that are commonplace across programs. Furthermore, QI is not unique to surgery and engagement with other specialties, as well as administration, can be leveraged to establish QI symposia or learning days outside the department of surgery. In addition to demonstrating appreciation for the residents’ work, this serves as an opportunity for faculty development.

Residents should present successful projects directly to the administration. These presentations will expand QI discussion, improve patient care, and show residents their research is valued. Previous work in medical fields suggests that residents may view QI as a lot of extra work, and we must remember to recognize and applaud their efforts. 8 Encourage residents to present their work at local and national meetings. As the field of patient safety and QI grows, there is great room for scholarship in this realm. Presenting at QI meetings should be encouraged and valued in line with support of research presentations and conference attendance.

Continuous improvement in the quality of care we deliver can only be achieved by continuous, frontline efforts. Effective QI curricula in residency will empower surgeons to participate in QI efforts in their clinical practice. Taking a cue from the business world on total quality management—a program aimed at increasing quality and productivity—we must “institute a vigorous program of education” and realize that quality transformation is everyone’s work. 23

- Davis K, Stremikis K, Schoen C, Squires D. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, 2014 Update: How the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally . The Commonwealth Fund; June 2014. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2014_ jun_1755_davis_mirror_mirror_2014.pdf . Accessed January 28, 2020.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Craossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001.

- Module 4. Approaches to Quality Improvement. AHRQ. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/system/pfhandbook/mod4.html . Published May 2013. Accessed June 30, 2019.

- Purnell SM, Wolf LM, Millar MM, Smith BK. A National Survey of Integrated Vascular Surgery Residents' Experiences with and Attitudes about Quality Improvement During Residency. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(1):158–165.

- Medbery RL, Sellers MM, Ko CY, Kelz RR. The unmet need for a national surgical quality improvement curriculum: A systematic review. J Surg Ed . 2014;71:613–631.

- Kelz RR, Sellers MM, Reinke CE, Medbery RL, Morris J, Ko C. Quality in-training initiative—A solution to the need for education in quality improvement: Results from a survey of program directors. J Am Coll Surg . 2013,217:1126–1132.

- Kuy S, Greenberg CC, Gusani NJ, Dimick JB, Kao LS, Brasel KJ. Health services research resources for surgeons. J Surg Res . 2011;171(1):e69–73.

- Butler JM, Anderson KA, Supiano MA, Weir CR. "It Feels Like a Lot of Extra Work": Resident Attitudes About Quality Improvement and Implications for an Effective Learning Health Care System. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):984–990.

- Bordage G, Harris I. Making a difference in curriculum reform and decision-making processes. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):87–94.

- American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. Practical QI: The basics of quality improvement education. ACS Quality In-Training Initiative; 2017. https://qiti.acsnsqip.org/ACS_NSQIP_2017_QITI_Curriculum.pdf . Accessed January 28, 2020.

- IHI Open School Home: IHI—Institute for Healthcare Improvement. IHI. http://www.ihi.org/education/IHIOpenSchool/Pages/default.aspx . Accessed January 28, 2020.

- Goldman J, Kuper A,Wong BM. How Theory Can Inform Our Understanding of Experiential Learning in Quality Improvement Education. Acad Med . 2018;93(12):1784–1790.

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/rerformance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–67.

- Jones AC, Shipman SA, Ogrinc G. Key characteristics of successful quality improvement curricula in physician education: A realist review. BMJ Qual Saf . 2015;24:77–88.

- Mosser G, Frisch KK, Skarda PK, Gertner E. Addressing the challenges in teaching quality improvement. Am J Med . 2009;122(5):487–491.

- Wong BM, Goldman J, Goguen JM, et al. Faculty-Resident “Co-Learning”: A Longitudinal Exploration Of An Innovative Model For Faculty Development In Quality Improvement. Acad Med . 2017; 92(8):1151–1159.

- Baxley EG, Lawson L, Garrison HG, et al. The Teachers Of Quality Academy: A Learning Community Approach To Preparing Faculty To Teach Health Systems Science. Acad Med. 2016; 91(12):1655–1660.

- Myers JS, Tess A, Glasheen JJ, et al. The Quality and Safety Educators Academy: Fulfilling an unmet need for faculty development. Am J Med Qual . 2014; 29(1):5–12.

- Stille CJ, Savageau JA, McBride J, Alper EJ. Quality Improvement “201”: Context-relevant quality improvement leadership training for the busy clinician-educator. Am J Med Qual . 2012; 27(2):98–105.

- Tevis SE, Ravi S, Buel L, Clough B, Goelzer S. Blueprint for a Successful Resident Quality and Safety Council. J Grad Med Educ . 2016;8(3):328–331.

- Tess A, Vidyarthi A, Yang J, Myers JS. Bridging the Gap: A Framework and Strategies for Integrating the Quality and Safety Mission of Teaching Hospitals and Graduate Medical Education. Acad Med . 2015;90:1251–1257.

- Sellers MM, Hanson K, Schuller M, et al. Development and participant assessment of a practical quality improvement educational initiative for surgical residents. J Am Coll Surg . 2013;216:1207–1213.

- Deming WE. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study; 1986.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement Open School Online—Basic Certificate in Quality & Safety

Coursera—Leading Healthcare Quality and Safety (Certificate available for a fee, course materials free)

Tuition Required—Certificate Programs

University of Washington—Certificate Program in Patient Safety and Quality

American Institute for Healthcare Quality— Certificate in Healthcare Quality

American Institute for Healthcare Quality— Certificate in Lean Six Sigma (Green Belt)

American Society for Quality—Quality Improvement Associate Certification

American Society of Health Care Risk Management— Patient Safety Certificate Program

University of Tennessee Health Science Center— Healthcare Quality Improvement, Certificate

Georgetown University—Executive Certificate for Patient Safety & Quality

George Washington University—Graduate Certificate in Health Care Corporate Compliance

University of Pittsburgh—Graduate Certificate in Health Systems Leadership and Management

University of Alabama—Graduate Certificate in Health Care Quality and Safety

University of Pennsylvania—Certificate in Health Care Quality and Safety

Johns Hopkins Medicine—Online Patient Safety Certificate

Northwestern University-Certificate in Health services Contemporary Issues and Methodology

Graduate Degrees

Thomas Jefferson University—Healthcare Quality and Safety Master’s (Online)

Nova Southeastern University—Master of Health Science: Health Care Risk Management, Patient Safety and Compliance Concentration

Franklin University—Master of Healthcare Administration—Healthcare Quality Management

Drexel University—MS in Quality, Safety and Risk Management in Healthcare (Online)

University of Illinois Chicago—Master of Science in Patient Safety Leadership (Online)

University of Alabama at Birmingham—Master of Science in Healthcare Quality and Safety (Online)

Western Governors University—Master of Health Leadership-Healthcare Quality (Online)

Georgetown University—Executive Master’s in Clinical Quality, Safety & Leadership

The George Washington University—Master of Health Sciences in Healthcare Quality (Online)

Mary Baldwin University—Master of Healthcare Administration in Quality and Systems Safety

Johns Hopkins University—Master of Applied Science in Patient Safety and Healthcare Quality (Online)

Northwestern University—Master of Science Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety and Masters of Science in Health Services and Outcomes Research

About the Authors

Neha R. Malhotra, MD, is a division of urology fellow at the University of Utah Department of Surgery in Salt Lake City.

Ashley Vavra, MD , is an assistant professor in the division of vascular surgery at Northwestern University in Evanston, IL.

Robert E. Glasgow, MD, is a professor, vice chair of clinical operation and quality, and the chief value officer in the department of surgery at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Brigitte K. Smith, MD, is an assistant professor, vice chair of education, and director of resident value curriculum in the department of surgery’s division of vascular surgery at University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The most effective ways to improve the health system presentation

Related posts.

Which components should be included in an effective message of appreciation?

Keep on Making Ways For Me

What are the 5 ways to make our food safer?

Name two ways to determine if a solution is acidic.

In what ways is meiosis II similar to and different from mitosis of a diploid cell?

Which of the following is least effective when building a sustainable competitive advantage?

All of the following are ways to reassure or calm a child during a haircutting service except:

What are three ways to put out a grease fire?

What are 5 ways food can be contaminated?

Which of the following is not one of the ways that angiotensin ii increases arterial blood pressure?

How fast does hair grow per day

Which of the following allows different operating systems to coexist on the same physical computer?

What is being defined as the degree to which something is related or useful to what is happening or being talked about?

Which of the following is NOT a pathway in the oxidation of glucose

Juan is the person employees go to when knowledge of a topic was needed. juan holds ________ power.

Which of the following is not a standard mounting dimension for an electric motor? select one:

Which set of characteristics will produce the smallest value for the estimated standard error?

Is a program that assesses and reports information about various computer resources and devices.

How much energy is needed to move one electron through a potential difference of 1.0 102 volts

Includes procedures and techniques that are designed to protect a computer from intentional theft

- Advertising

LATEST NEWS

What brand of castor oil is best for hair, what are control charts based on, vscode no server install found in wsl, needs x64, how do you get to motion settings on iphone, how long is a furlong in horse, replace the underlined word with the correct form, how many spinach plants per person, bread clip in wallet when traveling, what aisle is heavy cream on, how do you play roblox on a chromebook without downloading it.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Services

- Cookie Policy

- Knowledge Base

- Remove a question

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports; Ulmer C, Bruno M, Burke S, editors. Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010.

Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

6 Improving Presentation of Information

The NHQR and NHDR can be forward-looking documents that not only present historical trend data but also convey a story of the potential for progress and the health benefits to the nation of closing quality and disparity gaps. To serve as catalysts for improvement, the Future Directions committee envisions that the reports will extrapolate rates of change to indicate when gaps between current and recommended care might be closed and will present benchmarks on best-in-class performance. The committee makes sug gestions for organizing report content to tell a more complete quality improvement story, realize greater integration between quality improvement and disparities elimination, improve takeaway messages and data displays, and achieve a better match between the AHRQ products and potential audiences.

The NHQR and NHDR provide an enormous amount of data—principally presented in graphs—about how the United States is performing on various measures of health care and how performance has bettered or worsened over time. Although these data are useful, the NHQR and NHDR have potential beyond reporting on historical trends; the reports can also illuminate realistic levels of performance for all to strive toward and provide information on how long it will take to close gaps between current and recommended care at the current pace of improvement.

In this chapter, the committee expands on its vision that future versions of the NHQR and NHDR should tell a more complete story of how to move toward achieving a high-quality, high-value health care system. To make the information presented in the NHQR and NHDR more forward-looking and action-oriented, the committee recommends that AHRQ make greater use of benchmarking and suggests improvements to data displays and the general organization of the NHQR and NHDR. Helping audiences for the NHQR and NHDR better understand gaps in the quality of U.S. health care—whether between actual performance and receiving the recommended standard of care, or between population groups or geographic regions—and better understand the benefits of closing those gaps would provide audiences with stronger evidence and rationales for improving quality.

The chapter begins by reviewing the Future Directions committee’s suggestions for how AHRQ’s lineup of products could better serve current and expanded audiences. The committee underscores the importance of integrating disparities reduction into quality improvement by enhancing the relationship between the structure of the two national healthcare reports. Finally, suggestions are made on improving data displays and the statistical quality of quality reporting.

- MATCHING PRODUCTS TO AUDIENCE NEEDS

At present, the national healthcare reports and related products are consulted by a variety of stakeholders, many of which have different interest areas (e.g., heart disease, rural health, racial disparities, delivery settings) and different levels of sophistication for data interpretation and analysis. The 2001 IOM report Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report stated that the NHQR was not to be a “single static report, but rather a collection of annual reports tailored to the needs and interests of particular constituencies” (IOM, 2001, p. 6). The committee believes that AHRQ needs to expand and refine its quality reporting product line to provide products and data that are useful and understandable for a variety of audiences. Therefore, the committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 6: AHRQ should ensure that the content and presentation of its national health care reports and related products (print and online) become more actionable, advance recognition of equity as a quality of care issue, and more closely match the needs of users by:

- incorporating priority areas, goals, benchmarks, and links to promising practices;

- redesigning print and online versions of the NHQR and NHDR to be more integrated by recognizing disparities in the NHQR and quality benchmarks in the NHDR;

- taking advantage of online capability to build customized fact sheets and mini-reports; and

- enhancing access to the data sources for the reports.

The committee’s suggested products, along with their potential audiences, are reviewed in Table 6-1 .

Tailoring Products to Meet the Needs of Multiple Audiences.

Refining the Organization of the NHQR and NHDR

Integrating efforts to improve quality with efforts to eliminate disparities increases opportunities to positively affect change. Presenting the same organizational framework and measures in both reports reinforces users’ understanding of the relationship between overall health care quality and the depth of health care disparities. But currently, the two reports are not well linked beyond presenting the same measures.

Changing the Highlights Section of the Reports

The committee proposes that AHRQ present the same Highlights section in both the NHQR and NHDR to underscore the relationship between health care quality and equity. The text of the Highlights section should be developed so that the section can be published as a stand-alone document that could be the subject of dissemination events targeted to relevant stakeholder audiences. The document could:

- Spotlight areas with the greatest potential for quality improvement impact and provide detail on what the value of closing quality gaps would be to population health and equity.

- Feature progress on priority areas and toward any established national goals.

- Discuss evidence-based policies and best practices that may enhance quality improvement or factors that hinder progress as informed by data within the body of the report.

- Emphasize takeaway messages directed to different audiences (e.g., policy makers, health care providers, and the public) on what they can do to improve health care quality on prioritized topics and measures.

- Include a summary of state performance and the state of disparities.

The committee believes that a summary of state performance should be part of the Highlights section of the reports and would be of interest to legislators and policy makers at the state and national levels. A one- to two-page summary of state performance, perhaps in a scorecard fashion, should be included, and AHRQ could compile this from the information it already provides in the State Snapshots (e.g., ratings from very strong to very weak on overall health care quality, preventive measures, acute care measures, chronic measures, hospital care measures, cancer care measures). Currently, the State Snapshots are not available until several months after the reports have been released; the committee urges AHRQ to include this information in the Highlights section even if the detailed Snapshots are not posted online at the same time. Additionally, a summary on the state of disparities should be included.

Although the Highlights document proposed by the committee would be longer than the current Highlights section, sharing the same Highlights section should streamline AHRQ staff efforts.

Organizing the NHQR and NHDR by the Framework Components

The framework for health care quality and disparities measurement (see Chapter 3 ) is both a tool to assess whether balance is achieved in the selection of quality measures and a way to organize the reports. Table 6-2 suggests chapters (or sections) for future iterations of the NHQR and NHDR. To increase parallelism across both national healthcare reports, access to care, a topic currently addressed only in the NHDR, should also be included in future NHQRs. After carefully considering whether efficiency and health systems infrastructure should be featured in both reports, the committee concludes, as discussed in Chapter 3 , that efficiency measures of overuse and underuse are of interest for populations included in the NHDR and infrastructure is also applicable to equity concerns. Given the limited nature of measures at this time, however, the same efficiency and infrastructure measures may not always be available to include in both reports.

Sections Recommended for Future National Healthcare Reports.

Incorporating Equity into the NHQR

Based on interviews with current and potential users, the committee finds that, to some extent, the NHQR and NHDR have different audiences. There is one school of thought that improving health care performance overall will ameliorate the problem of disparities in health care; this view tends to neglect the reality that disparities in health care usually persist even as overall performance levels improve. The committee believes that closing equity gaps is one of the most important factors in raising overall health care quality (Chin and Chien, 2006; Clarke et al., 2004). For that reason, the NHQR should incorporate the concept of equity by including an additional section focusing on disparities elimination.

Quantifying the impact of disparities on overall quality performance may be one way to define the connection between health care quality and disparities in the Highlights section of the reports. Furthermore, the commentary on each measure within the NHQR could reflect the degree to which disparities remain or are growing even as quality improves so that conclusions on the state of quality are not misleading. An HIV/AIDS measure reported in the 2008 NHQR provides a concrete example of a situation where the nation as a whole is performing well but data in the NHQR mask disparities shown in the NHDR (AHRQ, 2009d, p. 65, 2009e, p. 63).

Presenting Data on Priority Populations

The NHDR is required by the 1999 federal law under which it was established to report on “prevailing disparities in health care delivery as it relates to racial factors and socioeconomic factors in priority populations.” 1 Priority populations were defined in the authorizing legislation with respect to the agency’s full portfolio of activities (research, evaluation, and demonstration projects): low-income groups, minority groups, women, children, the elderly, and individuals with special health care needs, including individuals with disabilities and individuals who need chronic care or end-of-life health care. AHRQ’s overall activities are also to address inner-city and rural areas. The fourth chapter of the NHDR, “Priority Populations,” includes limited supplemental measures specific to each priority population.

AHRQ has presented data on priority populations in the NHDR by offering: (1) summaries of the findings presented earlier in the report on access and on the core measures the NHDR shares with the NHQR (e.g., Tables 4.2 and 4.3 in the 2008 NHDR), and (2) occasional additional measures of particular interest for specific populations (e.g., hospital admissions for uncontrolled diabetes for American Indian and Alaska Native populations). The committee encourages more comprehensive treatment of the priority populations both within the reports and through other vehicles (e.g., alternate year treatment of priority populations in the reports, spinoff mini-reports with additional detail, customization of data via NHQRDRnet). The national reports should convey key measures that address top health concerns of the priority populations if they are not already part of the AHRQ set of core measures; inclusion would depend on passing the same rigorous evaluation process for measures outlined in Chapter 4 .

Given the limitations in the length of a print version of the NHDR, other vehicles can provide additional opportunities for more in-depth treatment. Specialized products for audiences interested in specific priority populations may garner more attention than solely expanding the priority population sections within the NHQRs and NHDRs. These derivative products could be published over time, perhaps in conjunction with partners who have a particular interest in care related to a topic or population.

While “women,” “children,” and the “elderly” are priority populations, they do not belong solely in the NHDR. At a minimum, the committee believes a summary of findings for these populations should be available in the NHQR. Moving to the NHQR much of this material, which is now in the NHDR, would open up space in the NHDR. The committee expects further inclusion of children’s quality measures in the future as a result of the findings from AHRQ’s National Advisory Council Subcommittee on Quality Measures for Children in Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Programs, and the ongoing AHRQ- and CMS-funded IOM study of Pediatric Health and Health Care Quality Measures (AHRQ, 2009c; IOM, 2010). The full number of metrics and the various analyses that might be performed will likely exceed the capacity of the print NHQRs and NHDRs; as noted earlier, more detailed treatment could be accomplished through a special topic report, alternating in-depth sections in the NHQR or NHDR, and/or an ability to customize reports through Web-based capabilities.

Bridging the NHQR and NHDR

An inherent problem in having two separate reports is that data on a subject (e.g., cancer, heart disease, a priority population) are split between the NHQR and NHDR. Moreover, in the NHDR, data on a subject are often hard to find because information is dispersed between different sections (see Box 6-1 ). This fragmentation of information will continue to exist, but adding an index at the end of each book would help users find information more readily.

How Do I Find Disease-Specific Information in the NHDR? When examining a health topic or specific population in the NHDR, the information is often difficult to find. For example, if one aims to look at colorectal cancer, one is unable to access all of (more...)

The committee also notes that introductory page(s) for the same topic in the NHQR and NHDR tend to cover the same types of information but are laid out differently; this requires unnecessary effort on the part of AHRQ staff and leads to confusion by readers. For example, the pages on effectiveness of cancer screening in the NHQR (AHRQ, 2009e, pp. 32-33) and NHDR (AHRQ, 2009d, p. 39) contain similar yet not identical information. The committee finds it logical to convey the same information in both locations.

Expanding and Sustaining Interest Through Derivative Products

AHRQ provides online access to the national healthcare reports and State Snapshots, to a few report-related fact sheets, and to an online data query system (NHQRDRnet); the Future Directions committee suggests changes to each of these products (see Table 6-1 , presented earlier in this chapter).

Fact Sheets and Mini-Reports

AHRQ has previously developed three fact sheets to supplement the NHQR and NHDR. The fact sheets have addressed the subjects of children and adolescents (AHRQ, 2005b, 2008a, 2009b), women’s health (2005c), and rural health (2005a). These fact sheets are not easily accessible on the national healthcare report-related websites; instead they are listed on AHRQ’s Measuring Quality website.

Concise fact sheets are a way to expand AHRQ’s reach of NHQR and NHDR findings and are useful for reaching new audiences. Timing the release of fact sheets to specific events (e.g., heart disease or breast cancer awareness months) could help sustain interest in the national healthcare reports throughout the year. Currently, Internet traffic to the NHQR and NHDR tends to decrease about two months after the report release date. Periodic releases of fact sheets could direct Internet traffic to the reports.

There may be times when a derivative product elaborating on a specific topic (e.g., a mini-report) could provide information beyond what can be contained in a fact sheet. The committee believes that such mini-reports could provide expanded treatment of priority populations. Priority population-specific derivative products would allow fuller exploration, for example, of the particular health care concerns of a priority population (e.g., children, women) or the diversity of health care experiences of different granular ethnicity groups within a race category (e.g., the Asian American population, for instance, is made up of persons of Japanese, Korean, and Cambodian heritage, among other granular ethnicity groups).

State Snapshots

In 2006, using data collected for the NHQR, AHRQ created the Web-based State Snapshots to fulfill the needs for state-level information of members of Congress, state officials, health care providers, and purchasers. As noted by previous IOM guidance, “analyses such as state-by-state comparisons on health care are familiar and meaningful to members of Congress, other policy makers, and consumers” (IOM, 2002, p. 5). The committee finds AHRQ’s Web-based State Snapshots to be a valuable addition to the NHQR and NHDR and recognizes recent improvements to the State Snapshots website. Nevertheless, the committee urges further development. For example, the State Snapshots do not show any data on access measures, and the committee believes these data are important to have at the state-level.

Health care report cards provide information about the quality of care by geographic regions, health plans, hospitals and other institutions, and even individual practitioners (Epstein, 1995). Report cards use various systems of scoring and passing judgment on quality, whether the end result is to grade national health performance, rank a state’s health care quality against all others, compare head-to-head the quality of care delivered in cities across the country, or to develop a list of best value hospitals (Brooke et al., 2008; Chernew and Scanlon, 1998; Davies et al., 2002; Hibbard and Jewett, 1997; Romano et al., 1999). A 2006 qualitative study conducted by AcademyHealth indicated that users of the State Snapshots suggested a rank ordering of states so that states could compare their performance against all others (Martinez-Vidal and Brodt, 2006). Currently, in the State Snapshots, each state is ranked on 18 selected measures. The committee’s view is that state-by-state ratings should be more clearly available so that states know what the best attained level of quality performance is, and then they could contact and learn from states with the best rates on specific quality measures. Additionally, it would be useful if state data and rankings were easily sortable for high-profile sets of metrics such as AHRQ core or HEDIS (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) measures, given the almost 200 measures that AHRQ tracks for states.

AHRQ displays average regional performance on measures in the State Snapshots, but state audiences have indicated that adjoining states are not always peers. AHRQ has provided a graphical “dial” to show states how they fit on a spectrum of contextual factors (i.e., demographics, health status, etc.), but states have noted that they would like flexibility to be able to identify a different coterie of peer states (for example, states that have the same degree of contextual factors). Then, for example, a state policy maker could assess state performance against states that have a comparable extent of persons below the poverty level.

Users of the NHQR and NHDR suggest that their needs for information tend to be topic specific and episodic; most users of the national healthcare reports are unlikely to read the reports from cover to cover. Additionally, the reports are viewed and downloaded online more than they are used in hard copy. 2 Thus, improving the ability of users to find needed information online is an important aim. In 2008, AHRQ added an online interactive tool called NHQRDRnet that can be used to query and search the databases behind the NHQR and NHDR by content areas (quality, access, patient safety, priority populations), clinical conditions, care type or settings, and dimensions of access (e.g., insurance coverage, usual source of care, utilization).

The committee applauds AHRQ’s intent to facilitate searching for content in the national healthcare reports but finds navigating the NHQRDRnet website difficult. The committee also observes that it takes fewer steps to gain similar information from the more straightforward and easier to use Appendix D of the NHQR and NHDR. AHRQ recently commissioned a usability survey that queried current users of the national healthcare reports about their experience with and impressions of the NHQR and NHDR and related Web content (Social & Scientific Systems and UserWorks, 2009). Comments from survey participants regarding ease of using the website and clarity of information echoed the committee’s findings (e.g., difficulty finding the reports using a basic Web search, organization of report, and Web content not matching user expectations).

The major change the Future Directions committee suggests for the NHQRDRnet is the development of a tool or sorting function that would allow users to customize their own reports. Now, one can search for all data related to a topic—for example, cancer—and all data files since 2002 are displayed for download; the search does not yield a fact sheet or summarization of the current content on the subject of interest. At a minimum, links to relevant text of the current year’s NHQR and NHDR would enhance the site’s usability and ability to tell a more comprehensive story. Additionally, one- or two-page fact sheets or more in-depth mini-reports on topics (whether individual clinical conditions, framework components, or something more specific, such as quality and disparities issues of specific interest to Hispanic persons) would be useful. AHRQ’s partnerships with other stakeholders would be assisted by having prepackaged collections of information in its NHQRDRnet index.

Web-based products, in addition to the NHQRDRnet, can be configured to make it easier to guide readers to other AHRQ or non-AHRQ resources that may help with quality improvement. For example, future online versions of the NHQRs and NHDRs could link to interventions highlighted in the AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange or other related resources (e.g., CMS, entities utilizing measures for which data at the national level are still aspirational). This linking capacity should also be available through the Web-based version of the NHQR and NHDR without the reader having to go through the NHQRDRnet.

Online Access to Data Used in the NHQR and NHDR

The committee discussed the extent to which the NHQR and NHDR should provide data for geographic areas below the state level. Various stakeholders have noted that the national healthcare reports contain information that is too “high level” for making decisions at the local or practice level. Consequently, the reports may be of less use to some health care providers, local policy makers, or some researchers than if the performance data were stratified to show performance at more local or organizational levels and provided in a timelier manner. State-based data are a unit of analysis that policy makers as well as the public can easily relate to and use for comparative purposes. Given the interest in substate variation (e.g., the Dartmouth Atlas, the University of Wisconsin/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation county-by-county health rankings), these data would be useful to develop over time (The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, 2010; RWJF and the University of Wisconsin, 2010). The NHQR and NHDR could also include linkages to other HHS data resources on community health status indicators (HHS, 2010).

The data included in the NHQR and NHDR may be reported nearly a year or more after they have been submitted to AHRQ because of the processes involved with compiling data sources, cleaning the data, analyzing it, reviewing the reports at the departmental level, and submitting the work for production. For entities that are evaluating performance in real time (daily, weekly, monthly), such data may have limited use. Still, there are groups that do not have day-to-day access to performance measurement data and would benefit from the wider availability of nationally collected data at a more local level (Kerr et al., 2004). For example, AHRQ has made available county-level data on the number of Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes who did not have an eye exam so that one area’s community aging agencies could focus intervention efforts (Moy, 2009).

In deciding whether to recommend that AHRQ provide more locally based data, the committee balanced the usefulness of local data, its timeliness, its reliability, and the additional workload for AHRQ staff. AHRQ staff indicated that it is possible to drill down to at least the larger Metropolitan Statistical Areas for about half of the State Snapshot measures, but that smaller Metropolitan Statistical Areas and counties would be more difficult because, for instance, some datasets are likely to require special permissions to present the data in these ways. 3 The committee encourages AHRQ to explore the feasibility and value of drilling down for at least some high-impact measures. When summarized in the reports, the Highlights section, or the proposed guide to using the NHQR and NHDR (discussed below), more localized data can inform readers about variation within states. Such detail could be presented in the State Snapshots to show substate variation, particularly when it is readily available in the datasets AHRQ already uses, and perhaps as a derivative product similar to the Atlas of Mortality (Pickle et al., 1996), depending on the availability of data for coverage of the United States. Links could be made to the HHS Community Health Status indicators site if it eventually included health care-related metrics and not just health status.

Individuals wanting to work with primary data are often not satisfied with the data available through the national healthcare reports’ website. AHRQ provides Excel files with the data points reflected in its graphs and text, but it does not provide access to the original datasets. Although AHRQ does not have in-house all of the databases it uses in the NHQR and NHDR, most of the data AHRQ uses are from federally sponsored datasets. The committee believes that data access could be expanded so that researchers can download the full dataset to manipulate it as needed. This is consistent with the efforts of data.gov , a website currently under development that will house all federal executive branch datasets, to “increase public access to high value, machine readable datasets generated by the Executive Branch of the Federal Government.” 4 AHRQ is among the agencies contributing data, as are other federal agencies whose data AHRQ acquires (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CMS). Because the website is still under construction, the committee is unable to discern which of AHRQ’s datasets will be made available. Nonetheless, the committee feels that making available datasets that support findings in the NHQR and NHDR would be a service to providers and health services researchers.

The committee encourages AHRQ and its partners to provide access to the data in a timely fashion, even prior to its publication in the NHQR and NHDR, to allow those with the capacity for analysis to use it for their own needs. Such data access was previously recommended to AHRQ by the IOM in the 2001 report Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report . Further, AHRQ should provide tools for analysts who want to replicate AHRQ’s methods to produce comparative data for their locale or population cohort. Until such tools are available, analytic methods will need to be clearly specified in methodology descriptions.

Proposed Development of a Guide to Using the NHQR and NHDR

Given the diversity of resources that AHRQ now offers and the potential for greater direct data access, the committee suggests that AHRQ develop a guide to using the NHQR and NHDR. As envisioned by the committee, this technical assistance product would review the resources that the print NHQR and NHDR and websites have to offer and, more importantly, would provide examples of how different stakeholder groups can apply the knowledge to action (e.g., Hispanic elders diabetes project). The guide to using the NHQR and NHDR would go beyond telling someone how to navigate a website. Instead, it would tells users how to access the data resources, provide tools for manipulating data for analyses, explain the methods used by AHRQ in its analyses, and offer suggestions for meaningful analyses. This guide, when it becomes available, should be referenced in the Highlights section of the NHQR and NHDR.

Dissemination Strategies

The committee proposes communicating the findings of the NHQR and NHDR to diverse audiences through a series of new products and modifications to existing documents. The goal of expanded dissemination efforts should be to raise awareness, visibility, and use of the reports. Between 2003 and 2008, AHRQ distributed approximately 24,000 print copies of the NHQR and NHDR. 5 The annual release of the NHQR and NHDR should be more widely publicized in advance, and momentum from the release of the reports should not be permitted to dwindle. The committee sought input on dissemination and media strategies for the NHQR and NHDR, as well as sample fact sheets, from Ketchum, a public relations and communications firm. 6

Ketchum suggested ways to repackage the wealth of information contained in the NHQR and NHDR throughout the year so that findings can be made continually relevant. AHRQ could, for example, produce succinct derivative materials that convey targeted messages (e.g., mini-reports and fact sheets), and link distribution and media outreach to appropriate audiences (e.g., advocacy groups for specific clinical conditions or population groups). In addition to relying on traditional media outreach (e.g., participating in roundtables, telebriefings, radio media tours, outreach around editorial calendars), AHRQ could take advantage of wide-reaching and increasingly common Web-based tools (e.g., blogs, advanced search engine options, inbound linking programs, social media such as Facebook and Twitter).