- Board of Regents

- Business Portal

New York State Education Department

- Commissioner

- USNY Affiliates

- Organization Chart

- Building Tours

- Program Offices

- Rules & Regulations

- Office of Counsel

- Office of State Review

- Freedom of Information (FOIL)

- Governmental Relations

- Adult Education

- Bilingual Education

- Career & Technical Education

- Cultural Education

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Early Learning

- Educator Quality

- Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

- Graduation Measures

- Higher Education

- High School Equivalency

- Indigenous Education

- My Brother's Keeper

Office of the Professions

- P-12 Education

- Special Education

- Vocational Rehabilitation

- Next Generation Learning Standards: ELA and Math

- Office of Standards and Instruction

- Diploma Requirements

- Teaching in Remote/Hybrid Learning Environments (TRLE)

- Office of State Assessment

- Computer-Based Testing

- Exam Schedules

- Grades 3-8 Tests

- Regents Exams

- New York State Alternate Assessment (NYSAA)

- English as a Second Language Tests

- Test Security

- Teaching Assistants

- Pupil Personnel Services Staff

- School Administrators

- Professionals

- Career Schools

- Fingerprinting

- Accountability

- Audit Services

- Budget Coordination

- Chief Financial Office

- Child Nutrition

- Facilities Planning

- Ed Management Services

- Pupil Transportation Services

- Religious and Independent School Support

- SEDREF Query

- Public Data

- Data Privacy and Security

- Information & Reporting

High School Regents Examinations

- June 2024 Examinations General Information

- Past Regents Examinations

- Archive: Regents Examination Schedules

- High School Administrator's Manual

- January 2024 Regents Examination Scoring Information

- Testing Materials for Duplication by Schools

- English Language Arts

- Next Generation Algebra I Reference Sheet

- Life Science: Biology

- Earth and Space Sciences

- Science Reference Tables (1996 Learning Standards)

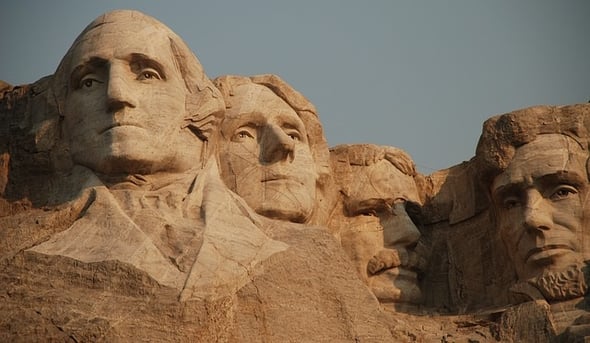

- United States History and Government

- Global History and Geography II

- Transition Examination in Global History and Geography

- High School Field Testing

- Test Guides and Samplers

- Technical Information and Reports

United States History and Government (Framework)

General information.

- Information Booklet for Scoring the Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework)

- Frequently Asked Questions on Cancellation of Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework) - Revised, 6/17/22

- Cancellation of the Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework) for June 2022

- Educator Guide to the Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework) - Updated, July 2023

- Memo: January 2022 Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework) Diploma Requirement Exemption

- Timeline for Regents Examination in United States History and Government and Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework)

- Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework) Essay Booklet - For June 2023 and beyond

- Prototypes for Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework)

- Regents Examination in United States History and Government (Framework) Test Design - Updated, 3/4/19

- Performance Level Descriptors (PLDs) for United States History and Government (Framework)

Part 1: Multiple-Choice Questions

- Part I: Task Models for Stimulus Based Multiple-Choice Question

Part II: Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions: Sample Student Papers

The links below lead to sample student papers for the Part II Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions for both Set 1 and Set 2. They include an anchor paper and a practice paper at each score point on a 5-point rubric. These materials were created to provide further understanding of the Part II Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions and rubrics for scoring actual student papers. Each set includes Scoring Worksheets A and B, which can be used for training in conjunction with the practice papers. The 5-point scoring rubric has been specifically designed for use with these Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions.

Part III: Civic Literacy Essay Question

The link below leads to sample student papers for the Part III Civic Literacy Essay Question. It includes Part IIIA and Part IIIB of a new Civic Literacy Essay Question along with rubrics for both parts and an anchor paper and practice paper at each score point on a 5-point rubric. These materials were created to provide further understanding of the Part III Civic Literacy Essay Question and rubric for scoring actual student papers. Also included are Scoring Worksheets A and B, which can be used for training in conjunction with the practice papers. The 5-point scoring rubric is the same rubric used to score the Document-Based Question essay on the current United States History and Government Regents Examination.

- Part III: Civic Literacy Essay Question Sample Student Papers

Get the Latest Updates!

Subscribe to receive news and updates from the New York State Education Department.

Popular Topics

- Charter Schools

- High School Equivalency Test

- Next Generation Learning Standards

- Professional Licenses & Certification

- Reports & Data

- School Climate

- School Report Cards

- Teacher Certification

- Vocational Services

- Find a school report card

- Find assessment results

- Find high school graduation rates

- Find information about grants

- Get information about learning standards

- Get information about my teacher certification

- Obtain vocational services

- Serve legal papers

- Verify a licensed professional

- File an appeal to the Commissioner

Quick Links

- About the New York State Education Department

- About the University of the State of New York (USNY)

- Business Portal for School Administrators

- Employment Opportunities

- FOIL (Freedom of Information Law)

- Incorporation for Education Corporations

- NYS Archives

- NYS Library

- NYSED Online Services

- Public Broadcasting

Media Center

- Newsletters

- Video Gallery

- X (Formerly Twitter)

New York State Education Building

89 Washington Avenue

Albany, NY 12234

CONTACT US

NYSED General Information: (518) 474-3852

ACCES-VR: 1-800-222-JOBS (5627)

High School Equivalency: (518) 474-5906

New York State Archives: (518) 474-6926

New York State Library: (518) 474-5355

New York State Museum: (518) 474-5877

Office of Higher Education: (518) 486-3633

Office of the Professions: (518) 474-3817

P-12 Education: (518) 474-3862

EMAIL CONTACTS

Adult Education & Vocational Services

New York State Archives

New York State Library

New York State Museum

Office of Higher Education

Office of Education Policy (P-20)

© 2015 - 2024 New York State Education Department

Diversity & Access | Accessibility | Internet Privacy Policy | Disclaimer | Terms of Use

The Civic Literacy Curriculum

A comprehensive set of free resources for educators and learners designed to prepare the next generation of leaders for American political and civil society.

Full Curriculum

The Civic Literacy Curriculum is a resource for teaching and learning American civics. Organized around but going beyond the U.S. Citizenship Test, it is available as both a full curriculum and abridged study guides. The full Civic Literacy Curriculum offers over 100 lessons including historical background, edited primary texts, exercises, worksheets, discussion prompts, and other tools to incorporate into your class, whether in-school or home-learning. These materials are completely free. ASU aims to make it easier for educators to access the tools they need to effectively teach the next generation of leaders. Click the button below to access the curriculum guide.

Access Full Curriculum Access Table of Contents

Access Teacher Materials

(Log in required)

Abridged Study Guides

The Civic Literacy Curriculum also offers abridged study guides for each learning section, with practice quizzes and flashcards, and hundreds of videos to help you prepare.

Access Civic Literacy Practice Tests Here

The abridged Civic Literacy Curriculum offers even more free materials for over 100 lessons including historical background, edited primary texts, exercises, worksheets, discussion prompts, and other tools to incorporate into your class— whether in school or home learning.

Our goal is to give lifelong learners the tools needed to hone your citizenship skills and knowledge. Browse the study guides for each of the seven learning sections, watch our curated video playlists or prep for your test!

Access Study Guides

Access Quiz Flashcards

Browse the Civic Literacy Curriculum

Section 1: principles of the american republic.

Full Curriculum Study Guide

Section 2: Systems of Government

Section 3: rights and responsibilities, full curriculum study guide , section 4: colonial period and independence, section 5: the 1800s, section 6: recent american history, section 7: geography, symbols, and holidays, additional resources.

The Civic Literacy Curriculum also includes over 200 videos, flashcards, and grade-level-appropriate tests for learners.

The Civic Literacy Curriculum video archive contains over 200 short videos for educators and learners to help build their knowledge of American civics and politics. Use the playlist browser below, visit our YouTube channel , or check out the archive for the complete list of videos.

And be sure to check out the flash cards and Civic Literacy Curriculum Test itself!

About the curriculum

The Civic Literacy Curriculum is a comprehensive civics curriculum developed and reviewed by educators and university scholars. The study guides, curriculum content for teachers, videos, and flash cards are all based on the United States Customs and Immigration Naturalization Test required by the federal government for those looking to become naturalized American citizens. The curriculum also goes above the federal Naturalization test, offering more opportunities for learning about the systems of government, American history, and more. Arizona State University faculty plan to continue to develop additional learning sections to supplement the Civic Literacy Curriculum.

Arizona State University's Center for American Civics developed the Civic Literacy Curriculum. The CAC aims to further research in American political thought and support civic education at all levels inside and outside the classroom. We support scholars, teachers, and students in their efforts to understand and improve American political society. We are nonpartisan and inter-ideological, focused on pursuing knowledge and practicing truth as common goods for American politics and culture.

The School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

The CAC is a research center in the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University. Established in 2017, the school combines a classical liberal arts curriculum with intensive learning experiences, including study abroad programs, professional internships, and leadership opportunities. Students graduate ready for government, law, business, and civil society careers.

- Introduction

- Citizenship Profile

- Major Findings

- Additional Finding

- Survey Methods

Information For:

- Policymakers

- Donors & Alumni

America’s Founders were convinced American freedom could survive only if each generation understood its founding principles and the sacrifices made to maintain it.

Failing Our Students, Failing America: Holding Colleges Accountable for Teaching America’s History and Institutions asks: Is American higher education doing its duty to prepare the next generation to maintain our legacy of liberty?

In fall 2005, researchers at the University of Connecticut’s Department of Public Policy (UConnDPP), commissioned by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s (ISI) National Civic Literacy Board, conducted a survey of some 14,000 freshmen and seniors at 50 colleges and universities. Students were asked 60 multiple-choice questions to measure their knowledge in four subject areas: America’s history, government, international relations, and market economy. The disappointing results were published by ISI in fall 2006 in The Coming Crisis in Citizenship: Higher Education’s Failure to Teach America’s History and Institutions . Seniors, on average, failed all four subjects, and their overall average score was 53.2%.

This report follows up on The Coming Crisis in Citizenship . It is based on an analysis of the results of a second survey of some 14,000 freshmen and seniors at 50 colleges conducted by the research team at UConn in the fall of 2006. The results of this second survey corroborate and extend the results of the first. Seniors once again failed all four subjects.

The question now is: Will legislators, donors, trustees, parents, and other decision-makers hold colleges accountable?

MAJOR FINDINGS

College seniors failed a basic test on america’s history and institutions..

The average college senior knows astoundingly little about America’s history, government, international relations and market economy, earning an “F” on the American civic literacy exam with a score of 54.2%. Harvard seniors did best, but their overall average was 69.6%, a disappointing D+.

Colleges Stall Student Learning about America.

From kindergarten through 12th grade, the average student gains 2.3 points per year in civic knowledge, almost twice the annual gain of the average college student. Students at some colleges did learn more per year than students in grade school, demonstrating that it is possible.

- Eastern Connecticut State, one of 25 colleges randomly selected for this year’s survey, was the best performer, increasing civic knowledge by 9.65 points. Rhodes College, which increased civic knowledge by 7.42 points, was the best performer among 18 elite colleges surveyed both this year and last. Rhodes was also the best overall performer last year.

America’s Most Prestigious Universities Performed the Worst.

Colleges that do well in popular rankings typically do not do well in advancing civic knowledge.

- Generally, the higher U.S. News & World Report ranks a college, the lower it ranks here in civic learning. At four colleges U.S. News ranked in its top 12 (Cornell, Yale, Duke, and Princeton), seniors scored lower than freshmen. These colleges are elite centers of “negative learning.” Cornell was the third-worst performer last year and the worst this year.

- Surveyed colleges ranked by Barron’s imparted only about one-third the civic learning of colleges overlooked by Barron’s .

Inadequate College Curriculum Contributes to Failure.

The number of history, political science, and economics courses a student takes helps determine, together with the quality of these courses, whether he acquires knowledge about America during college. Students generally gain one point of civic knowledge for each civics course taken. The average senior, however, has taken only four such courses.

Greater Learning about America Goes Hand-in-Hand with More Active Citizenship.

Students who gain more civic knowledge during college are more likely to vote and engage in other civic activities than students who gain less.

ADDITIONAL FINDINGS

Additional finding 1:, higher quality family life contributes to more learning about america..

College seniors whose families engaged in frequent conversations about current events and history, whose parents were married and living together, and who came from homes where English was the primary language all tended to learn more than students who lacked these advantages.

Additional Finding 2:

American colleges under-serve minority students..

The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. eloquently argued that the civil rights movement was rooted in America’s founding documents as well as key historical events and decisions. American colleges today are not helping minorities learn this heritage. On average, minority seniors (Asian, Black, Hispanic, and Multiracial) answered less than half the exam questions correctly and made no significant overall gain in civic knowledge during college. Civic-knowledge gain among whites was six times greater.

Additional Finding 3:

American colleges don’t teach their foreign students about america..

The average foreign student at an American college learns nothing about America’s history and institutions. Colleges thus squander an opportunity to foster greater understanding of America’s institutions in an increasingly hostile world.

QUESTIONS OF ACCOUNTABILITY

1: are parents and students getting their money’s worth from college costs.

The least-expensive colleges increase civic knowledge more than the most expensive.

2: Are Taxpayers and Legislators Getting Their Money’s Worth from College Subsidies?

Colleges enjoying larger subsidies in the form of government-funded grants to students tend to increase civic knowledge less than colleges enjoying smaller such subsidies.

3: Are Alumni and Philanthropists Getting Their Money’s Worth from the Donations they make to Colleges?

Some of the worst-performing colleges also have the largest, most rapidly growing endowments. These include Yale, Penn, Duke, Princeton, and Cornell.

4: Are College Trustees Getting Their Money’s Worth from College Presidents?

Six of the 10 worst-performing colleges also ranked among the top 10 for the salaries they paid their presidents. These include Penn, Cornell, Yale, Princeton, Rutgers and Duke, which paid their presidents $500,000 or more.

5: Are Colleges Encouraging Students to Take Enough Courses about America’s History and Institutions and Then Assessing the Quality of These Courses?

The average senior had completed only four courses in history, political science, and economics. But more courses taken did not always mean more knowledge gained. At eight colleges, each additional civics course a student completed, on average, decreased his civic knowledge.

- Print This Page

- Email This Page

- Ask A Librarian

- Meet with a Librarian

- Research by Topic

- Writing Center

- Online Assistance

- In-Person Assistance

- Faculty Services

- Writing Resources

- Document Delivery

- Course Reserves

- Circulation

- Library Instruction

- Computer Programming Consultation

- Featured Collections

- Digital Arts + Humanities Lab

- Group Study Rooms

- Instructional Spaces

- Meeting Spaces

- Library Profile

- Policies and Forms

On Thursday, May 23 from 9-10 a.m., campus IT staff will perform maintenance that may impact access to library resources and Document Delivery.

- Helmke Library

- General Guides

- Civics Literacy

- Introduction

Civics Literacy: Introduction

What is civics literacy, civics literacy proficiency program, guide purpose.

- Program Requirements

- Supplemental Library Resources

Assistant Librarian

Civics literacy is defined as:

The knowledge and skills to participate effectively in civic life through knowing how to stay informed, understanding governmental processes, and knowing how to exercise the rights and obligations of citizenship at local, state, national, and global levels. Individuals also have an understanding of the local and global implications of civic decisions. (Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2009; Morgan, 2016)

In June 2021, the Purdue University Board of Trustees adopted a civics literacy graduation requirement for undergraduates, including all transfer students. This requirement applies to all undergraduate students who enter Purdue University Fort Wayne in Fall 2022 or any subsequent semester.

The Civics Literacy Proficiency activities are designed to develop the civic knowledge of PFW students in an effort to graduate a more informed citizenry. These activities will:

- Increase your understanding of important contemporary political issues.

- Identify opportunities to grow your engagement in American politics.

- Expand your awareness of and options for civic participation.

The Civics Literacy Proficiency activities are accessed via Brightspace. Here is the link for the PFW Civics Literacy page .

This library guide is meant to act as a supplemental resource for the program. It includes a brief overview of the requirements along with library resources that complement the program and enhance civics literacy education.

- Next: Program Requirements >>

- Last Updated: Oct 18, 2023 8:29 AM

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the best us history regents review guide 2020.

General Education

Taking US History in preparation for the Regents test? The next US History Regents exam dates are Wednesday, January 22nd and Thursday, June 18th, both at 9:15am. Will you be prepared?

You may have heard the test is undergoing some significant changes. In this guide, we explain everything you need to know about the newly-revised US History Regents exam, from what the format will look like to which topics it'll cover. We also include official sample questions of every question type you'll see on this test and break down exactly what your answers to each of them should include.

What Is the Format of the US History Regents Exam?

Beginning in 2020, the US History Regents exam will have a new format. Previously, the test consisted of 50 multiple-choice questions with long essays, but now it will have a mix of multiple choice, short answer, short essay, and long essay questions (schools can choose to use the old version of the exam through June 2021). Here's the format of the new test, along with how it's scored:

In Part 2, there will be two sets of paired documents (always primary sources). For each pair of documents, students will answer with a short essay (about two to three paragraphs, no introduction or conclusion).

For the first pair of documents, students will need to describe the historical context of the documents and explain how the two documents relate to each other. For the second pair, students will again describe the historical context of the documents then explain how audience, bias, purpose, or point of view affect the reliability of each document.

Part A: Students will be given a set of documents focused on a civil or constitutional issue, and they'll need to respond to a set of six short-answer questions about them.

Part B: Using the same set of documents as Part A, students will write a full-length essay (the Civic Literacy essay) that answers the following prompt:

- Describe the historical circumstances surrounding a constitutional or civic issue.

- Explain efforts by individuals, groups, and/or governments to address this constitutional or civic issue.

- Discuss the extent to which these efforts were successful OR discuss the impact of the efforts on the United States and/or American society.

What Topics Does the US History Regents Exam Cover?

Even though the format of the US History Regents test is changing, the topics the exam focuses on are pretty much staying the same. New Visions for Public Schools recommends teachers base their US History class around the following ten units:

As you can see, the US History Regents exam can cover pretty much any major topic/era/conflict in US History from the colonial period to present day, so make sure you have a good grasp of each topic during your US History Regents review.

What Will Questions Look Like on the US History Regents Exam?

Because the US History Regents exam is being revamped for 2020, all the old released exams (with answer explanations) are out-of-date. They can still be useful study tools, but you'll need to remember that they won't be the same as the test you'll be taking.

Fortunately, the New York State Education Department has released a partial sample exam so you can see what the new version of the US History Regents exam will be like. In this section, we go over a sample question for each of the four question types you'll see on the test and explain how to answer it.

Multiple-Choice Sample Question

Base your answers to questions 1 through 3 on the letter below and on your knowledge of social studies.

- Upton Sinclair wrote this letter to President Theodore Roosevelt to inform the president about

1. excessive federal regulation of meatpacking plants 2. unhealthy practices in the meatpacking plants 3. raising wages for meatpacking workers 4. state laws regulating the meatpacking industry

There will be 28 multiple-choice questions on the exam, and they'll all reference "stimuli" such as this example's excerpt of a letter from Upton Sinclair to Theodore Roosevelt. This means you'll never need to pull an answer out of thin air (you'll always have information from the stimulus to refer to), but you will still need a solid knowledge of US history to do well.

To answer these questions, first read the stimulus carefully but still efficiently. In this example, Sinclair is describing a place called "Packingtown," and it seems to be pretty gross. He mentions rotting meat, dead rats, infected animals, etc.

Once you have a solid idea of what the stimulus is about, read the answer choices (some students may prefer to read through the answer choices before reading the stimulus; try both to see which you prefer).

Option 1 doesn't seem correct because there definitely doesn't seem to be much regulation occurring in the meatpacking plant. Option 2 seems possible because things do seem very unhealthy there. Option 3 is incorrect because Sinclair mentions nothing about wages, and similarly for option 4, there is nothing about state laws in the letter.

Option 2 is the correct answer. Because of the stimulus (the letter), you don't need to know everything about the history of industrialization in the US and how its rampant growth had the tendency to cause serious health/social/moral etc. problems, but having an overview of it at least can help you answer questions like these faster and with more confidence.

Short Essay

This Short Essay Question is based on the accompanying documents and is designed to test your ability to work with historical documents. Each Short Essay Question set will consist of two documents. Some of these documents have been edited for the purposes of this question. Keep in mind that the language and images used in a document may reflect the historical context of the time in which it was created.

Task: Read and analyze the following documents, applying your social studies knowledge and skills to write a short essay of two or three paragraphs in which you:

In developing your short essay answer of two or three paragraphs, be sure to keep these explanations in mind:

Describe means "to illustrate something in words or tell about it"

Historical Context refers to "the relevant historical circumstances surrounding or connecting the events, ideas, or developments in these documents"

Identify means "to put a name to or to name"

Explain means "to make plain or understandable; to give reasons for or causes of; to show the logical development or relationship of"

Types of Relationships :

Cause refers to "something that contributes to the occurrence of an event, the rise of an idea, or the bringing about of a development"

Effect refers to "what happens as a consequence (result, impact, outcome) of an event, an idea, or a development"

Similarity tells how "something is alike or the same as something else"

Difference tells how "something is not alike or not the same as something else"

Turning Point is "a major event, idea, or historical development that brings about significant change. It can be local, regional, national, or global"

It's important to read the instructions accompanying the documents so you know exactly how to answer the short essays. This example is from the first short essay question, so along with explaining the historical context of the documents, you'll also need to explain the relationship between the documents (for the second short essay question, you'll need to explain biases). Your options for the types of relationships are:

- cause and effect,

- similarity/difference

- turning point

You'll only choose one of these relationships. Key words are explained in the instructions, which we recommend you read through carefully now so you don't waste time doing it on test day. The instructions above are the exact instructions you'll see on your own exam.

Next, read through the two documents, jotting down some brief notes if you like. Document 1 is an excerpt from a press conference where President Eisenhower discusses the importance of Indochina, namely the goods it produces, the danger of a dictatorship to the free world, and the potential of Indochina causing other countries in the region to become communist as well.

Document 2 is an excerpt from the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. It mentions an attack on the US Navy by the communist regime in Vietnam, and it states that while the US desires that there be peace in the region and is reluctant to get involved, Congress approves the President of the United States to "take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression."

Your response should be no more than three paragraphs. For the first paragraph, we recommend discussing the historical context of the two documents. This is where your history knowledge comes in. If you have a strong grasp of the history of this time period, you can discuss how France's colonial reign in Indochina (present-day Vietnam) ended in 1954, which led to a communist regime in the north and a pro-Western democracy in the south. Eisenhower didn't want to get directly involved in Vietnam, but he subscribed to the "domino theory" (Document 1) and believed that if Vietnam became fully communist, other countries in Southeast Asia would as well. Therefore, he supplied the south with money and weapons, which helped cause the outbreak of the Vietnam War.

After Eisenhower, the US had limited involvement in the Vietnam War, but the Gulf of Tonkin incident, where US and North Vietnam ships confronted each other and exchanged fire, led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (Document 2) and gave President Lyndon B. Johnson powers to send US military forces to Vietnam without an official declaration of war. This led to a large escalation of the US's involvement in Vietnam.

You don't need to know every detail mentioned above, but having a solid knowledge of key US events (like its involvement in the Vietnam War) will help you place documents in their correct historical context.

For the next one to two paragraphs of your response, discuss the relationship of the documents. It's not really a cause and effect relationship, since it wasn't Eisenhower's domino theory that led directly to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, but you could discuss the similarities and differences between the two documents (they're similar because they both show a fear of the entire region becoming communist and a US desire for peace in the area, but they're different because the first is a much more hands-off approach while the second shows significant involvement). You could also argue it's a turning point relationship because the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was the turning point in the US's involvement in the Vietnam War. Up to that point, the US was primarily hands-off (as shown in Document 1). Typically, the relationship you choose is less important than your ability to support your argument with facts and analysis.

Short Answers and Civic Literacy Essay

This Civic Literacy essay is based on the accompanying documents. The question is designed to test your ability to work with historical documents. Some of these documents have been edited for the purpose of this question. As you analyze the documents, take into account the source of each document and any point of view that may be presented in the document. Keep in mind that the language and images used in a document may reflect the historical context of the time in which it was created.

Historical Context: African American Civil Rights

Throughout United States history, many constitutional and civic issues have been debated by Americans. These debates have resulted in efforts by individuals, groups, and governments to address these issues. These efforts have achieved varying degrees of success. One of these constitutional and civic issues is African American civil rights.

Task: Read and analyze the documents. Using information from the documents and your knowledge of United States history, write an essay in which you

Discuss means "to make observations about something using facts, reasoning, and argument; to present in some detail"

Document 1a

Document 1b

- Based on these documents, state one way the end of Reconstruction affected African Americans.

- According to this document, what is one way Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois disagreed about how African Americans should achieve equality?

- According to this document, what is one reason Thurgood Marshall argued that the "separate but equal" ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson should be overturned?

Document 4a

Document 4b

- Based on these documents, state one result of the sit-in at the Greensboro Woolworth.

- According to Henry Louis Gates Jr., what was one result of the 1960s civil rights protests?

- Based on this document, state one impact of the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Start by reading the instructions, then the documents themselves. There are eight of them, all focused on African American civil rights. The short answers and the civic literacy essay use the same documents. We recommend answering the short answer questions first, then completing your essay.

A short answer question follows each document or set of documents. These are straightforward questions than can be answered in 1-2 sentences. Question 1 asks, "Based on these documents, state one way the end of Reconstruction affected African Americans."

Reading through documents 1a and 1b, there are many potential answers. Choose one (don't try to choose more than one to get more points; it won't help and you'll just lose time you could be spending on other questions) for your response. Using information from document 1a, a potential answer could be, "After Reconstruction, African Americans were able to hold many elected positions. This made it possible for them to influence politics and public life more than they had ever been able to before."

Your Civic Literacy essay will be a standard five-paragraph essay, with an introduction, thesis statement, and a conclusion. You'll need to use many of the documents to answer the three bullet points laid out in the instructions. We recommend one paragraph per bullet point. For each paragraph, you'll need to use your knowledge of US history AND information directly from the documents to make your case.

As with the short essay, we recommended devoting a paragraph to each of the bullet points. In the first paragraph, you should discuss how the documents fit into the larger narrative of African American civil rights. You could discuss the effects of Reconstruction, how the industrialization of the North affected blacks, segregation and its impacts, key events in the Civil Rights movement such as the bus boycott in Montgomery and the March on Washington, etc. The key is to use your own knowledge of US history while also discussing the documents and how they tie in.

For the second paragraph, you'll discuss efforts to address African American civil rights. Here you can talk about groups, such as the NAACP (Document 3), specific people such as W.E.B. Du Bois (Document 2), and/or major events, such as the passing of the Civil Rights Act (Document 5).

In the third paragraph, you'll discuss how successful the effort to increase African American civil rights was. Again, use both the documents and your own knowledge to discuss setbacks faced and victories achieved. Your overall opinion will reflect your thesis statement you included at the end of your introductory paragraph. As with the other essays, it matters less what you conclude than how well you are able to support your argument.

3 Tips for Your US History Regents Review

In order to earn a Regents Diploma, you'll need to pass at least one of the social science regents. Here are some tips for passing the US Regents exam.

#1: Focus on Broad Themes, Not Tiny Details

With the revamp of the US History exam, there is much less focus on memorization and basic fact recall. Every question on the exam, including multiple choice, will have a document or excerpt referred to in the questions, so you'll never need to pull an answer out of thin air.

Because you'll never see a question like, "What year did Alabama become a state?" don't waste your time trying to memorize a lot of dates. It's good to have a general idea of when key events occurred, like WWII or the Gilded Age, but i t's much more important that you understand, say, the causes and consequences of WWII rather than the dates of specific battles. The exam tests your knowledge of major themes and changes in US history, so focus on that during your US History Regents review over rote memorization.

#2: Don't Write More Than You Need To

You only need to write one full-length essay for the US History Regents exam, and it's for the final question of the test (the Civic Literacy essay). All other questions (besides multiple choice) only require a few sentences or a few paragraphs.

Don't be tempted to go beyond these guidelines in an attempt to get more points. If a question asks for one example, only give one example; giving more won't get you any additional points, and it'll cause you to lose valuable time. For the two short essay questions, only write three paragraphs each, maximum. The short response questions only require a sentence or two. The questions are carefully designed so that they can be fully answered by responses of this length, so don't feel pressured to write more in an attempt to get a higher score. Quality is much more important than quantity here.

#3: Search the Documents for Clues

As mentioned above, all questions on this test are document-based, and those documents will hold lots of key information in them. Even ones that at first glance don't seem to show a lot, like a poster or photograph, can contain many key details if you have a general idea of what was going on at that point in history. The caption or explanation beneath each document is also often critical to fully understanding it. In your essays and short answers, remember to always refer back to the information you get from these documents to help support your answers.

What's Next?

Taking other Regents exams ? We have guides to the Chemistry , Earth Science , and Living Environment Regents , as well as the Algebra 1 , Algebra 2 , and Geometry Regents .

Need more information on Colonial America? Become an expert by reading our guide to the 13 colonies.

The Platt Amendment was written during another key time in American history. Learn all about this important document, and how it is still influencing Guantanamo Bay, by reading our complete guide to the Platt Amendment .

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Critical affective civic literacy: A framework for attending to political emotion in the social studies classroom

Heightened political polarization challenges civic educators seeking to prepare youth as citizens who can navigate affective boundaries. Current approaches to civic education do not yet account for the emotional basis of citizenship. This paper presents an argument for critical affective literacy in civic education classrooms. Drawing from concepts and theories in critical emotion studies, affective citizenship, and agonistic political theory, critical affective civic literacy challenges the rationalistic bent of civic education, and offers instructional strategies for educating the political emotions of students. The voices of late-arrival migrant youth enacting affective citizenship are featured in order to help illuminate the contributions of critical affective literacy to social studies research and practice.

1. Introduction

Increasing political polarization challenges civic educators to prepare youth as citizens who can navigate ideological and affective boundaries. A 2014 Pew Research Center poll found that not only are Republicans and Democrats more ideologically divided than they have been in decades, but also feel more animosity towards each other ( Pew Research Center, 2014 ). For example, “27% of Democrats see the Republican Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being,” up from 16% in 1994 ( Pew Research Center, 2014 ). The current presidential administration’s use of emotion-based discourses to label people of color, Muslims, and migrants as fearsome, or not deserving of citizenship, has a measurable impact on the work of civic educators. According to a study by the Southern Poverty Law Center, following the 2016 presidential election, “four in ten [teachers] heard derogatory language directed at students of color, Muslims, [and] immigrants” ( Southern Poverty Law Center, 2016 ). Moreover, in schools with racially and socio-economically diverse student populations, tensions have flared due to students reportedly being less trusting of each other.

As diverse public spaces, schools are uniquely situated to prepare students to navigate affective boundaries in the broader political discourse ( Parker, 2003 ). However, there is limited research that theorizes emotion and its role in the civics classroom. Current approaches to civic education rely primarily on deliberative models of citizenship that relegate emotions to the private sphere ( Hess & McAvoy, 2015 ; Knowles & Clark, 2018 ). Recent scholarship has explored the affective dimension of citizenship, including the links between political emotion and civic engagement ( Abowitz & Mamlok, 2019 ), and sought to better understand how teachers conceptualize emotions in the social studies classroom ( Sheppard & Levy, 2019 ). This nascent work challenges the predominant approach of teaching students to resolve social issues through rational deliberation and dialogue ( Lo, 2017 ).

Looking to the field of literacy education, promising scholarship links critical literacy approaches ( Freire, 1970 ) with critical affect studies ( Ahmed, 2014 ) in order to develop an educational response to the current polarized political context. Anwaruddin (2016) proposed a conceptual framework of critical affective literacy (CAL) to address ethical dilemmas regarding how to respond to human suffering, and asks why some people are deemed worthier of moral concern than others. CAL is based on the theory that emotions do not reside solely in the body, or in society, but are performative and interactional ( Zembylas, 2007 ). In addition, CAL draws on the work of critical affect scholars who argue that “emotions create the very effect of the surfaces and boundaries that allow us to distinguish an inside and outside in the first place” ( Ahmed, 2014 , p. 10).

Understanding how emotions delineate citizenship boundaries is pivotal to the work of social studies education and the preparation of youth as engaged and compassionate citizens who can respond to human suffering. For instance, through greater awareness of the role emotion plays in creating affective boundaries, we can critically examine how our emotional response to state-sponsored violence committed against “Others” may be linked to discourses of fear or pride. For example, Donald Trump’s portrayal of asylum seekers and their children as an “invasion” ( realDonaldTrump, 2018 ) conditions how we respond to the inhumane treatment of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, including the policy of child separation ( United States Department of Justice, 2018 ).

Attention to the emotional work that takes place in social studies classrooms also builds on previous critical citizenship frameworks ( Banks, 2008 ; Ladson-Billings, 2004 ) to challenge liberal conceptions of citizens as rational actors, by inviting civic educators and their students to explore their emotional commitments at different scales (e.g. family, neighborhood, community, world) and to reflect on the emotional basis of their civic engagements ( Zembylas, 2014 ). Greater attention to the role of emotions in political life also opens up new avenues for the civic engagement of disenfranchised groups who are excluded from a civic sphere where universal agreement or consensus is the end goal (( Lo, 2017 ); Ruitenberg, 2009 ).

In this paper I outline how CAL’s four principles – (1) examining why we feel what we feel; (2) striving to enter a relation of affective equivalence; (3) interrogating the production and circulation of objects of emotion in everyday politics; and (4) focusing on the performativity of emotions to achieve social justice – could be implemented in the civic education classroom. I will offer an analytical argument that young citizens develop a critical awareness of the role emotion plays in political life as part of their civic preparation in order to address unequal power relations in society. I begin with a discussion of the limitations of current empirical and theoretical research on the role of emotion in citizenship preparation. I then describe the political theories of affective citizenship and agonism that inform an approach to social studies education that takes emotions seriously. Next, I discuss each of the four principles of CAL in turn, and their specific application to the K-12 civics classroom, and social studies teacher education. In order to further illuminate this approach to educating political emotions, I feature the voices of migrant students enacting affective citizenship ( Keegan, 2019 ). Their narratives demonstrate how a critical awareness of emotion can contribute to a more engaged citizenship. I conclude with a discussion of the contributions of agonistic political theory towards implementing CAL in civic education classrooms.

2. Literature review

2.1. educating political emotions in the social studies.

In order to become active, informed, and engaged citizens, youth must develop a critical awareness of emotion and its role in politics. However, emotion is rarely mentioned in the literature on the skills and dispositions necessary for youth to acquire as part of their civic preparation. The widely referenced report, The Civic Mission of Schools , published by The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, defines “competent and responsible citizens” as “having the skills, knowledge, and commitment needed to accomplish public purposes, such as group problem solving, public speaking, petitioning and protesting, and voting,” as well as “moral and civic virtues such as concern for the rights and welfare of others, social responsibility, tolerance and respect, and belief in the capacity to make a difference” ( CIRCLE, 2003 , p. 4). Notably absent from this definition is any reference to the emotional labor ( Hochschild, 1983 ) that goes into acquiring the necessary civic virtues. Instead, it is assumed that being tolerant is a mere cognitive exercise of understanding the reasonableness of worldviews that differ from one’s own.

In their review of the social studies literature, Sheppard, Katz and Grosland (2015) found that while the topics of emotion and affect are of interest to researchers, “they are un-theorized, and their role in the process of teaching and learning social studies remains primarily hidden” (p 157). An area of research that has made an important contribution to understanding emotions in civics classrooms have been studies examining how teachers facilitate controversial issues discussions, including under what circumstances they disclosed their feelings on political issues ( Hess, 2005 ; James, 2009 ). A reason some teachers gave for withholding their political beliefs, was to remain “objective” to students ( Hess, 2005 ). This pedagogical stance may reflect an underlying conception of school as a public space where “unbiased” facts take precedence over consideration of feelings, which belong to the private sphere.

Shepard and Levy (2019) found that social studies teachers weighed a variety of contextual factors in deciding how to attend to emotions in the classroom. Whereas some teachers chose topics they considered controversial in order to invite impassioned debate, others avoided topics they deemed too emotionally sensitive for their students in order to maintain what they believed to be a safe classroom space. Research surrounding the 2016 presidential election found that some teachers responded to their Muslim and immigrant students’ fears of a Trump presidency by avoiding discussion of the election outcome altogether, and trying to remain neutral ( Dunn et al., 2019 ).

A small number of studies consider the place of emotion in social studies teacher education. This is an important area of investigation, since teachers are unlikely to welcome emotions into their classrooms if they have not had an opportunity to explore the relationship between emotion and their own civic commitments. Garrett’s (2011) study about difficult knowledge explores the relationships between emotion and learning with pre-service teachers. Grounded in psychoanalytic theory, Garrett investigates “the affective relationships that individuals have with social knowledge” (p. 344). Teachers’ empathic feelings towards the recent past has important implications for civic education, including awareness of present-day injustices and the ability to join in solidarity with others to address inequity.

However, the conception of politics as reasoned debate may be so ingrained in current models of civic preparation that attempts to spur critical awareness of emotion will meet with resistance from pre-service social studies teachers. Reidel and Salinas (2011) found it difficult to dislodge the theory of emotion as individual and private in a teacher education course that sought to engage emotions explicitly in classroom discussions of controversial issues. Despite the instructor’s repeated efforts to bring attention to the role of emotions, students were critical of classmates they judged as being too “emotional” during class discussions. In order to raise critical awareness of emotion, theories are needed that explain how emotions function in civic education, how emotions can motivate different forms of civic engagement, and how emotion-based civic discourses regulate who is deserving of “concern” and “tolerance.”

2.2. Challenges to deliberative models of civic education

The lack of attention to emotion in social studies education is due in part to the pervasiveness of liberal assimilationist conceptions of the public sphere, which advocate a strict separation of public and private spheres in order to reach agreement on universal rules of civil discourse and ensure equality ( Rawls, 1971 ). Because emotions are viewed as a threat to rational deliberation and the ability to arrive at democratic consensus they are confined to the private sphere. However, feminist political philosophers have contended that calls for a ‘universal’ public sphere privilege particular forms of ‘manly’ speech that merely reinforce power imbalances in society and exclude minoritized groups from particular forms of civic participation ( Fraser, 1992 ; Young, 1990 ). Feminist critiques of democratic dialogue rightly point out that classrooms are public spaces that reflect societal inequalities, and therefore not all voices may receive equal consideration ( Boler, 1999 ). Speech that is deemed too ‘emotional’ may be dismissed in favor of supposedly ‘reasoned opinion.’ Moreover, critics of liberal assimilationist citizenship education have called for the recognition of cultural rights and group-based identities in the public sphere so that diverse members of society can experience civic equality ( Banks, 2008 ; Flores & Benmayor, 1998 ) Finally, liberal conceptions of citizenship that focus on the individual as the carrier of rights and responsibilities neglect the importance of group affiliation and belonging to civic engagement and ‘the political’ ( Mouffe, 2005 ).

As public spaces, civic education classrooms are necessarily shaped by debates over the role of emotion in democratic deliberation and citizenship. Civic educators must equip our youngest citizens to recognize how emotions are situated within unequal power relations in society, and how emotion-based discourses regulate feelings towards “Others” or promote feelings of pride or loyalty to the nation-state ( Helmsing, 2014 ). Zembylas (2014) discussed how emotions help to regulate the boundaries of belonging in multicultural, pluralistic democracies. Affective boundaries create us/them distinctions that determine “who is seen as the ‘legitimate’ object of empathic and tolerant feelings” ( Zembylas, 2014 , p. 11).

Another challenge to liberal conceptions of the public sphere comes from the agonistic model of democracy that sees conflict as inherent to political life ( Mouffe, 2005 ; Ruitenberg, 2009 ). According to Mouffe’s conception of pluralist politics, “the prime task of democratic politics is not to eliminate the passions from the sphere of the public, but to mobilize these passions towards democratic designs” ( Mouffe, 2005 , p. 103). Several researchers have drawn on the agonistic critique of liberalism to argue for greater attention to emotion in civic education. Ruitenberg (2009) contended that “political education cannot consist in skills of reasoning and civic virtues alone, but must also take into account the desire for belonging to collectivities, and attendant political emotions” (p. 274). An example of a political emotion is political anger, which is “the indignation one feels when decisions are made and actions are taken that violate … the ethico-political values of equality and liberty that, one believes, would support a just society” ( Ruitenberg, 2009 , p. 277). Building on agonistic political theory, Lo (2017) argued that deliberative discussions that emphasize consensus over conflict alienate students who “already feel distant from the status quo, [and] accentuate their lack of power in the current system, especially if they were not involved when the commonalities were first deduced” (p. 2). Instead, Lo proposed several changes to how deliberative discussions are conducted in civic education classrooms, including agonistic deliberations that allow students to draw upon their passionate responses to social injustice. Rather than compromise or consensus, the end result of agonistic deliberation is negotiated action steps to address a social issue.

Recent research seeking to better understand political emotion was a case study by Abowitz and Mamlok (2019) of youth civic activism to address gun violence following the mass shooting in Parkland, Florida. Political emotion, according to the authors, “can be thought of as the explicit connection between affect or feeling and political actions, events or ideas” (p. 161). The leaders of the political campaign to end gun violence, known as #NeverAgainMSD, were driven by the indignation they felt at the normalization of gun violence. Rather than make rational appeals to lawmakers to address the violence, the youth expressed their anger publicly and shamed politicians for offering ‘thoughts and prayers’ instead of concrete actions.

However, not all political emotion may be directed at redressing injustice. Emotions like hate and fear can be used to manipulate citizens into feeling certain ways towards the nation-state. An important consideration, then, is how to channel political conflict into democratic commitments, rather than as a means to sow affective divisions in society ( Ruitenberg, 2009 ). While agonistic political theory sees conflict as inherent to democratic deliberation, it does not go far enough in explaining how affective boundaries construct citizens in particular ways, or how emotion can become a site of resistance. In order to address these concerns, in the next section I will discuss how the concept of affective citizenship disrupts the concept of citizenship “as a strictly legal, institutional product of state authority and rationality” ( Fortier, 2016 , p. 1038).

3. Theoretical framework: affective citizenship

The concept of affective citizenship “identifies which emotional relationships between citizens are recognized and endorsed or rejected, and how citizens are encouraged to feel about themselves and others” ( Zembylas, 2014 , p. 6). The feelings youth have for the nation, neighbors, migrants, or those deemed “Other,” are not predetermined, but rather socially mediated and constructed. Feminist scholarship laid important groundwork for understanding the affective basis of citizenship. Hochschild (1983) wrote about the existence of ‘feeling rules’ that govern our emotions. Feeling rules are most apparent when a discrepancy arises between our feelings and how social convention tells us we should feel. Ahmed (2014) offered a model of the sociality of emotion in which emotions are not something we have , but rather emotions move and circulate to transform certain ‘Others’ into objects of feeling. Ahmed’s theory helps explain why some emotions, whether fear, love, hatred, or concern “stick” more to some bodies than others, leaving their impressions, and creating us/them distinctions.

Emotions also circulate in schools to construct what Fortier (2010) calls the ‘affective citizen.’ According to Fortier (2010) , “the ‘affective subject’ becomes the ‘affective citizen’ when its membership to the ‘community’ is contingent on personal feelings and acts that extend beyond the individual self … to the community” (p. 22). Zembylas (2014) analyzed two emotional injunctions in pluralistic societies that explain how the ‘affective citizen’ is constructed in schools. The first emotional injunction is “coping with difference” (p 12). The assumption behind the emotional imperative to cope with difference is that “multiculturalism brings discomfort to the host population, and therefore, ideal citizens have to learn to live with difference” (p. 12). However, as Zembylas contends, feelings of discomfort and unease are not distributed equally among people. Certain types of religious, ethnic, or racial differences are believed to cause greater degrees of discomfort. As Ahmed (2014) theorizes, the emotion of fear, hate, or shame attaches more to some bodies than others. Therefore, if a goal of civic education is to prepare youth to be able “to enter into dialogue with others about different points of view” ( CIRCLE, 2003 , p. 10, emphasis added), it is necessary to be able to critically analyze how ‘difference’ is constructed through particular emotional discourses.

The second emotional injunction that Zembylas analyzes is that of “embracing the other” (p. 11). Zembylas cites the motto of ‘we are all different, and yet, we are all the same’ endorsed by many schools as demonstrative of a tension between celebrating diversity, and expecting those who are deemed ‘different’ to assimilate. Another example of how schools ‘embrace the other’ is the practice of hanging flags in corridors to show the variety of nations represented in the student body. These public displays project a self-image of the school as a civic space that is welcoming and tolerant of diversity. In this case, the object of emotions that circulate can be a school motto celebrating diversity, or a national ideal of embracing some forms of difference. Collective ideals, whether or not they are fully realized, is another way that the affective citizen is constructed. As Ahmed (2014) explains, “identifying with the ideal of the multicultural nation, means that one gets to see oneself as a good or tolerant subject” (p. 133–134).

At the same time, the imperative to ‘embrace the other’ is not unconditional. Those who do not “reflect back the good image the nation has of itself” are not welcome ( Ahmed, 2014 , p. 134). A recent illustration of how acceptance and belonging is conditioned upon having the proper feelings for the nation can be found in reactions to Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s criticism of America. Omar, a high-profile Somali American, Muslim woman, and refugee, told a group of high school students how, for her family fleeing civil war, the U.S. had not kept its promise of being “the country that guaranteed justice to all” ( Jaffe & Mekhennet, 2019 ). In response, President Trump tweeted out that Omar, should “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came” 1 ( realDonaldTrump, 2019 ). Omar’s belonging was predicated on her having the proper feelings of gratitude towards America for accepting her family. This example demonstrates how becoming an affective citizen is predicated on personal feelings and acts that extend beyond the individual to the nation-state ( Fortier, 2010 ).

Emotion-based discourses can also “govern through affect” in schools. For example, refugee students may be made into the objects of teachers’ compassion or pity ( Anwaruddin, 2016 ). In order to be welcomed into the school community, refugee and migrant students may be expected to take advantage of educational opportunities in the U.S., and demonstrate that they are ‘good’ citizens by working hard in school. The terms of conditional belonging may be used by teachers to label some migrant youth as ‘model minorities’ ( Lee, 2009 ), or create divisions between students who show proper appreciation for education, and those who do not ‘care’ about school in the ways teachers expect ( Valenzuela, 1999 ). Those who either criticize America, or don’t reflect back the image America has of itself as a land of equal opportunity and tolerance can be deemed less deserving of compassion and care.

In summary, defining ‘good’ citizenship as being “concerned for the rights and welfare of others” ( CIRCLE, 2003 , p. 10) is insufficient without also considering how affective boundaries determine who is considered deserving of concern and social welfare. The concept of affective citizenship helps explain the emotional basis of citizenship, including “how less-desirable political emotions function in politics” ( Abowitz & Mamlok, 2019 , p. 172). The theory of the sociality of emotion ( Ahmed, 2014 ) can inform approaches to CAL in civics classrooms, so that students can become more aware of the role of emotion in creating social divisions, and as a political asset for seeking justice.

4. Critical affective civic literacy

Anwaruddin’s (2016) framework of CAL is motivated by the questions, “How should we respond to violence? Are we supposed to be touched by the suffering of some, and yet be indifferent to the suffering of others?” (p. 381). Anwaruddin looks to the field of critical literacy for answers, but finds that the “rationalistic tendency of critical literacy often blurs our vision when we try to understand the suffering of others” (p 388). Similarly, I have argued that the rational approach to deliberation in civic education also makes it difficult to understand how the objects of emotion circulate to label some political subjects as more or less deserving of compassion and care. In the sections below, I describe and build on the four pedagogical principles of CAL to discuss how they can be adapted and applied specifically in the civics classroom and social studies teacher education. In order to help illustrate the application of CAL to citizenship preparation, I include the voices of migrant youth enacting affective citizenship ( Keegan, 2019 ). I conclude by integrating agonistic political theory and CAL to explain how emotion can function as a civic asset.

4.1. Examining why we feel what we feel

The first principle of CAL is for students to examine not only what they feel, but why they feel that way. Building on Ahmed (2014) , Anwaruddin argues that “emotions are relational and that emotions involve relations of ‘towardness’ and ‘awayness’” (p. 390). When we come into contact with a particular object of our emotion, we may move toward or away from it based on “the object’s immediate revelation of its orientation toward us or by our own prejudgments of the object and its history …” (p. 388). Students can develop a critical awareness of emotion by tracing their emotional responses towards “Others” to discourses of fear and anxiety. Anwaruddin (2016) recommends that “teachers and students interrogate popular culture and media texts to identify which emotions are renamed for particular predefined effects” (p. 391). For instance, the continent of Africa is frequently portrayed in the media as a place shaped by tribalism and ethnic conflict, poverty and malnutrition, and wilderness and exotic animals ( Ukpokodu, 2017 ; Watson & Knight-Manuel, 2017 ). Following the 2014 outbreak of Ebola in parts of West Africa, Newsweek published an issue with a racist photo on its cover, featuring a chimpanzee and the heading “A Back Door for Ebola” ( Flynn & Scutti, 2014 ). The characterization of migrants from Africa as carrying dangerous diseases contributed to outbreaks of bullying in schools. Two brothers from Senegal, 11- and 13-years-old, were taunted and physically attacked at their school in the Bronx, NY. Classmates yelled at the boys, “Go back home” and “Ebola” ( Hagan, 2014 ). A high school student in a study with West African migrant youth explained the effect emotion-based discourses of fear have on his sense of belonging and identity as African: “‘People say everywhere have Ebola in Africa. And when I hear about it I get so angry because when people see you as African, they treat us different. Because you’re from somewhere that people don’t like’” ( Keegan, 2019 , p. 359).

As part of their civic preparation, K-12 students and pre-service social studies teachers can learn to interrogate how injunctions to feel certain ways towards people and places produce subjects who are more or less deserving of belonging by studying the history of xenophobia in the U.S. Throughout U.S. history, migrants including Chinese, Irish, and Mexicans, have been associated with disease and contagion ( Lee, 2019 ). The supposed threat of disease labeled these migrants as foreign, and hid the true effects of poverty, racism and structural inequality. The history of xenophobia in the U.S. is an example of how racialized fear of migrants has been spread through emotion-based discourses that label migrant bodies as dangerous.

Increased racism towards Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) during the coronavirus pandemic is the most recent example of how fear of disease has been used to label some bodies as unhygienic and threatening. According to a recent poll by the New Center for Public Integrity/Ipsos, almost a third of Americans reported having witnessed someone blaming Asian people for the coronavirus epidemic ( Jackson, Berg, & Yi, 2020 ), and STOP AAPI HATE has received over 1700 reports of verbal harassment, shunning, and physical assaults since March 19, 2020 ( Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council, 2020 ). President Trump has been accused of exacerbating racism and xenophobia towards AAPI by referring to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” ( Baynes-Dunning, 2020 ). Lessons that teach K-12 students how to identify and interrupt hate and bias are essential. However, they must also be educated on how to make sense of the emotion-based discourses they encounter on social media, as well as trace their own emotional responses towards migrant “Others.”

Besides fear, emotions like love and compassion can also harm and essentialize migrant, refugee, or asylum-seeking youth, by categorizing them as pitiable and vulnerable ( Anwaruddin, 2017 ). Students can investigate whether emotional injunctions to ‘embrace the Other,’ or show compassion towards migrants, are meant to reproduce an image of the U.S. as a compassionate nation, and its citizens as caring people. In order to recognize how discourses engender particular emotional responses, students could compare how different media outlets report on the same event. Bondy and Johnson (2019) suggested that pre-service teachers analyze how conservative and liberal news sources each portray the effect of deportations on children born in the U.S. to migrant parents. Students can assess whether and how migrants are portrayed in each source as either criminals undeserving of sympathy, or as vulnerable children separated from their parents.

4.2. Striving to enter a relation of affective equivalence

The second principal of CAL “invites ‘us to imagine standing in the shoes of others’” ( Anwaruddin, 2016 , p. 391). More broadly, Anwaruddin asks how we are to understand the suffering of others in order to be sensitized to violence and injustice. According to Anwaruddin, the “various frames used to re/present their suffering allocate the recognizability of certain human bodies as grievable while others are non- or less-grievable” (p. 391). Seeing the world through the eyes of a refugee seeking asylum in the United States, for instance, is conditioned on how the refugee’s suffering is presented to us, whether as someone to be feared, or a threat to American identity. In addition, Anwaruddin distinguishes between an act of recognition and recognizability . Anwaruddin quotes Butler (2010) to make this key distinction: “recognizability characterizes the more general conditions that prepare or shape a subject for recognition – the general terms, conventions, and norms ‘act’ in their own way, crafting a living being into a recognizable subject” (p. 5).

This principle of CAL is aligned with the goal of considering multiple perspectives during democratic deliberations, which is frequently touted in civics education. Some scholars of teaching and learning in history consider empathy to be a necessary element of historical thinking, including “affective engagement with historical figures to better understand and contextualize their lived experiences, decisions, or actions” ( Endacott & Brooks, 2013 , p. 41). Barton and Levstik (2004) contend that “perspective recognition,” their preferred term for historical empathy, “is indispensable for public deliberation in a pluralistic society,” where people hold diverse views and opinions based on their lived experience (p. 224). Many civic educators agree that schools should cultivate empathy so that students will become citizens who make decisions that benefit the least advantaged members of society, and not just themselves ( Parker, 2003 ). Moreover, preparing youth for global citizenship can include “perspective consciousness,” which Merryfield (2012) defines as “the recognition that our view of the world is not universally shared, [and] that this view of the world is shaped by influences that often escape conscious detection …” (p. 20).

However, these pedagogical approaches to perspective-taking in social studies classrooms do not consider how the ability to empathize with others or imagine their suffering depends on how ‘they’ are presented to ‘us.’ CAL challenges civic educators to think differently about the skill of perspective-taking, and how to teach students to recognize how particular perspectives, and the people who hold them, get framed as un/reasonable. Furthermore, CAL strives to feel ‘with’ the suffering of others. Notably, this relation of affective equivalence is not the same as feeling sad ‘about’ others’ suffering, which diverts attention away from the person who is suffering, and makes them the “object of our feeling” ( Anwaruddin, 2016 , p. 21).

As public spaces, schools can further promote relations of affective equivalence in the classroom by framing the diverse perspectives of students as civic assets to be leveraged. In a study with West African youth attending a high school for late-arrival migrants, teachers created instructional groups so that a variety of native languages were represented ( Keegan, 2019 ). Students heard from and drew upon a diversity of perspectives as they completed group projects, and developed an awareness of how culture shaped one’s worldview. Moreover, in accordance with CAL, the youth developed an awareness of the conditions of recognizability, because teachers situated every perspective as valuable to listen to and learn from.

4.3. Interrogating the production and circulation of objects of emotion in everyday politics

The third principle of CAL focuses on the affective politics of emotions, notably fear, to manipulate the populace into supporting particular policy decisions. Anwaruddin contends that “instructional activities have to be designed to show how emotions – such as fear – are created and circulated.” Fixing certain subjects as the objects of fear enables political leaders and others in positions of power to take preemptive action against those who would supposedly do us harm. Anwaruddin uses the example of President Bush’s decision to invade Iraq based on the false premise that Saddam Hussein harbored weapons of mass destruction to illustrate an affective politics of fear. A more recent example is President Trump’s portrayal of migrants at the U.S. southern border seeking asylum as an “invasion” ( Bondy & Johnson, 2019 ). The Trump administration justified its policy of detaining migrants at the border, including putting children in cages and separating them from their parents, by portraying asylum-seekers as people who would do harm to America. The emotion of fear conditions the response of American citizens to the suffering of these migrants seeking entry to the U.S., so that their lives “do not touch us, or do not appear as lives at all” ( Butler, 2010 , p. 50).

In order to investigate the circulation of emotion in everyday politics in civics classrooms, and in social studies methods courses, students could compare speeches by Trump and President Barack Obama on the topic of immigration. For example, after studying the discourse of fear of migrants used by Trump in his public comments, students could analyze the circulation of emotion in remarks made by President Obama at a naturalization ceremony in 2015:

Just about every nation in the world, to some extent, admits immigrants. But there’s something unique about America. We don’t simply welcome new immigrants – we are born of immigrants. Immigration is our origin story. And for more than two centuries, it’s remained at the core of our national character; it’s our oldest tradition. It’s who we are. It’s part of what makes us exceptional ( The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 2015 ).