Coronavirus Disease 2019

How the pandemic changed family dynamics, the potential impact of covid-19 on adolescents’ social development..

Posted August 2, 2021 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- The social effects of quarantine hit younger adolescents particularly hard, derailing typical development.

- During COVID-19, family was more influential than friends during a developmental period when the opposite would normally be true.

- Siblings may have functioned as a buffer against the social effects of quarantine for older adolescents.

The social landscape has looked wildly different over the past year and a half. Because of the quarantines and social restrictions made necessary by the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person social interactions were greatly reduced in 2020 as many found themselves spending the majority of their time at home with family, and away from friends and colleagues. Previous research has already connected quarantine and increased mental health issues that have been observed during the pandemic (e.g., Chahal et al., 2020; Ghebreyesus et al., 2020).

Adolescence is a time of social exploration where peers begin to play a greater role than parents as teens move toward independence, so the disruption of this normative timeline, and particularly interactions with friends, is cause for concern (Ellis et al., 2020; Orben, Tomova, Blakemore, 2020). Cross-sectional studies on the effects of COVID-19 have shown that maintaining friendships is something children and adolescents were bothered by and that while online social connections can be beneficial, in-person interactions are more effective (Ellis et al., 2020; Orben et al., 2020).

A recent study led by Dr. Reuma Gadassi-Polack in our lab expanded what is known about the effects of COVID-19 quarantine by looking at adolescents’ social interactions and depressive symptoms before and during the pandemic (Gadassi Polack et al., in press). Researchers collected data from kids using short questionnaires completed daily, a year before COVID and again at the beginning of the pandemic. Each day, participants reported both positive and negative interactions with family members and peers and their depressive symptoms.

The study looked at 112 participants (age 8-15) who completed daily questionnaires in both the initial pre-COVID data collection (Wave 1) and the data collection during COVID (Wave 2). Researchers were able to capture information about both individual relationships and how they affect one another via “spillover,” a concept that will be discussed further below.

COVID Had Greater Negative Effects on Younger Adolescents

In typical development, we would expect to see uniform increases in interactions with peers alongside decreases in interactions with parents (e.g., Lam et al., 2012; Larson et al., 1991; Larson et al., 1996). Instead, younger (but not older) participants had significantly fewer positive interactions with peers during COVID compared to pre-COVID. For participants 13 and older, significantly more positive interactions with siblings were seen during COVID vs. before. This led to a greater negative impact on younger adolescents, who lost positive interactions with peers without gaining any positive interactions with siblings like older adolescents. In fact, younger adolescents had more negative interactions with siblings than friends or parents.

For both age groups, negative interactions with friends significantly decreased while there were no other significant decreases in other relationships. This finding presents a different facet of the move to online school: for some, this was an opportunity to escape a negative environment.

Altogether, the lack of the expected increase in interactions with friends suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has derailed the typical trajectory of social development. The larger effect can potentially be credited to less social development as younger adolescents are experiencing the same effects earlier in development, with less social skills in place. A further implication of these results is that in-person interactions cannot be neatly substituted with virtual interaction.

Family Members Were More Influential than Friends During the Early Stages of COVID-19

Looking at a process named “spillover” allowed researchers to understand the connections within the family, family subsystems, and peer relationships. The concept of spillover is grounded in the idea that our social world is made up of subsystems, including those within the family: the mother and father is a subsystem, as is the parent and child, or the siblings. These subsystems are of course connected (e.g., the mother-father relationship is related to the mother-child relationship), but not without some boundaries . When these boundaries become weaker, interactions in one subsystem can affect interactions in other subsystems via spillover (e.g., Chung et al., 2011; Flook & Fuligni, 2008; Kaufman et al., 2020; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000; Mastrotheodoros et al., 2020).

For example, an argument between parents can cause each parent to be more likely to argue with their child. What began as a negative interaction in the mother-father relationship has then spilled over into the parent-child relationship. This example would be considered negative spillover, where negative occurrences in one subsystem lead to negative interactions or feelings in another. Positive spillover occurs when the same thing happens with positive occurrences. For example, being praised by their mother might cause a child to be kinder to their sibling . Then, a positive interaction in the mother-child relationship has spilled over into the sibling relationship.

COVID-19 appeared to create a more closed family system, with fewer spillover effects from outside and more inside. In other words, interactions with family members impacted interactions with friends to a lesser degree during COVID. Separate interactions with family and friends are expected to affect each other less as adolescents develop typically. However, in the context of the pandemic, this was particularly detrimental for those who already had more negative family relationships prior to COVID as there was less day-level positive spillover and increased negative spillover on the individual level.

Increase in Depressive Symptoms Related to Family Interactions

Changes were not only seen in interactions, but also in levels of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms increased significantly by almost 40 percent during COVID-19, regardless of age. This signifies the severity of COVID-19’s impact on adolescent mental health, above and beyond any increase in depression typically seen in development (e.g., Salk et al., 2016). The occurrence of less positive and more negative interactions with family members significantly predicted depressive symptoms during COVID-19.

More Positive than Negative Interactions and a New Role for Siblings

The effects of the social changes wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic were not wholly negative, however. Overall, most kids reported five times more positive interactions than negative interactions. Importantly, having more positive interactions with family members was associated with smaller increases in depressive symptoms during COVID.

The effect of the pandemic on sibling relationships was also more positive. Few would be surprised to hear siblings had a high number of negative interactions – much higher compared to any other relationship. However, increased positive interactions without an increase in negative interactions with siblings was seen in older adolescents, suggesting that siblings can compensate at least somewhat for the decrease in in-person peer interactions.

Combined with prior research on siblings’ positive effects on mental health and loneliness (McHale, Updegraff, & Whiteman, 2012; Wikle, Ackert, & Jenson, 2019), these results suggest that the presence of siblings is beneficial during a time of social isolation .

In general, this research shines a light on how important peer interactions are for normative development and the necessity of ensuring children and adolescents are given opportunities to spend time, especially in-person, with peers.

Take-Home Points

- Family negativity predicted the increase in depressive symptoms during COVID-19. In families with more positive interactions, there was less of an increase.

- Siblings potentially functioned as a buffer for the social effects of quarantine for older adolescents.

Anna Leah Davis, a Yale undergraduate, contributed to the writing of this blog post.

Chahal, R., Kirshenbaum, J. S., Miller, J. G., Ho, T. C., & Gotlib, I. H. (2020). Higher executive control network coherence buffers against puberty-related increases in internalizing symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biological Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.08.010

Chung, G. H., Flook, L., & Fuligni, A. J. (2011). Reciprocal associations between family and peer conflict in adolescents' daily lives. Child Development, 82, 1390–1396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01625.x

Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 52, 177-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000215

Flook, L., & Fuligni, A. J. (2008). Family and school spillover in adolescents’ daily lives. Child Development, 79, 776-787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01157.x

Gadassi Polack, R. Sened, H., Aubé, S., Zhang, A., Joormann, J., & Kober, H. (in press) Connections during Crisis: Adolescents’ social dynamics and mental health during COVID-19. Developmental Psychology.

Ghebreyesus, T.A. (2020). Addressing mental health needs: an integral part of COVID-19 response. World Psychiatry, 19, 129–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20768

Hankin, B. L., Stone, L., & Wright, P. A. (2010). Corumination, interpersonal stress generation, and internalizing symptoms: accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multiwave study of adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990368

Kaufman, T. M., Kretschmer, T., Huitsing, G., & Veenstra, R. (2020). Caught in a vicious cycle? Explaining bidirectional spillover between parent-child relationships and peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 32, 11-20. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001360.

Krishnakumar, A., & Buehler, C. (2000). Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta‐analytic review. Family Relations, 49, 25-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x

Lam, C. B., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2012). Parent–child shared time from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 83, 2089-2103. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01826.x

Larson, R., & Richards, M. H. (1991). Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: Changing developmental contexts. Child Development, 62, 284-300. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131003

Larson, R. W., Richards, M. H., Moneta, G., Holmbeck, G., & Duckett, E. (1996). Changes in adolescents' daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology, 32, 744–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.744

Mastrotheodoros, S., Van Lissa, C. J., Van der Graaff, J., Deković, M., Meeus, W. H., & Branje, S. J. (2020). Day-to-day spillover and long-term transmission of interparental conflict to adolescent–mother conflict: The role of mood. Journal of Family Psychology. doi: 10.1037/fam0000649.

McHale, S. M., Updegraff, K. A., & Whiteman, S. D. (2012). Sibling Relationships and Influences in Childhood and Adolescence. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 74, 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x

Orben, A., Tomova, L., & Blakemore, S. J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2352-4642(20)30186-3

Salk, R. H., Petersen, J. L., Abramson, L. Y., & Hyde, J. S. (2016). The contemporary face of gender differences and similarities in depression throughout adolescence: Development and chronicity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 205, 28-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.071

Wikle, J. S., Ackert, E., & Jensen, A. C. (2019). Companionship patterns and emotional states during social interactions for adolescents with and without siblings. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 2190–2206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01121-z

Jutta Joormann, Ph.D ., is a professor of psychology at Yale University who studies risk factors for depression and anxiety disorders.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Rochester News

- Science & Technology

- Society & Culture

- Campus Life

- University News

How does the pandemic affect families who were already struggling?

- Facebook Share on Facebook

- X/Twitter Share on Twitter

- LinkedIn Share on LinkedIn

Rochester psychologists have been awarded federal funding to study the pandemic’s long-term effects on family cohesion and child well-being.

About a year and a half after COVID-19 rapidly spread around the globe, scientists have begun to examine the pandemic’s long-term societal effects. University of Rochester psychologists and the University’s Mt. Hope Family Center have been awarded a $3.1 million grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development ( NICHD ) to study the pandemic’s implications for American families and parenting.

The study’s principal coinvestigators, psychology professors Melissa Sturge-Apple and Patrick Davies , expect acute negative effects on family functioning and family cohesion to last for years, especially in families that already experienced high levels of difficulties prior to the pandemic.

While scientifically sound, measures to slow the pandemic—such as stay-at-home orders, remote instruction, and limited public gatherings—had negative repercussions on families.

“The pandemic has been extremely stressful for families with significant worries about the health of family members, financial instability, food uncertainty, social isolation, and increased caregiving burdens associated with having children at home,” says Sturge-Apple, who is also the University’s vice provost and dean of graduate education. “The study seeks to identify factors that helped families cope, in order to inform best interventions for families at risk.”

How and why COVID amplifies family conflict

During the pandemic, the incidence of domestic violence in the US surged, with estimates ranging between a 21 to 35 percent increase. These statistics are particularly distressing in the context of already high levels of harsh parenting , as documented in Davies and Sturge-Apple’s work, even before the pandemic.

“By following families before, during, and after the pandemic, we will be able to assess more precisely how and why COVID-19 may amplify conflict between parents that then spills over into the way they care for their children,” says Davies. “Our study will examine a number of different mechanisms at neurobiological, familial, and extrafamilial levels.”

What helped secure the NICHD funding was the existence of a recent three-year family study at Mt. Hope Family Center immediately prior to the onset of the pandemic, which provides a baseline against which the additional COVID-19 stressors and effects can be measured. The teams plan on three additional annual waves of data collection.

Understanding the public health significance is crucial for developmental scientists, clinicians, and public policy advocates in order to develop evidence-based treatments and interventions that help struggling families.

The NICHD will award the grant funding over five years.

The Mt. Hope Family Center sits on a two-way street. Its researchers and clinicians have provided evidence-based services to at-risk families, while training the next generation of clinicians and research scientists.

New grants recognize the center’s success in addressing complex challenges among vulnerable children and their families.

A new study shows that early experiences of environmental harshness, in combination with personal temperament, can shape the child’s problem-solving abilities later in life.

More in Society & Culture

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak has dramatically changed americans’ lives and relationships over the past year. we asked people to tell us about their experiences – good and bad – in living through this moment in history..

Pew Research Center has been asking survey questions over the past year about Americans’ views and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August, we gave the public a chance to tell us in their own words how the pandemic has affected them in their personal lives. We wanted to let them tell us how their lives have become more difficult or challenging, and we also asked about any unexpectedly positive events that might have happened during that time.

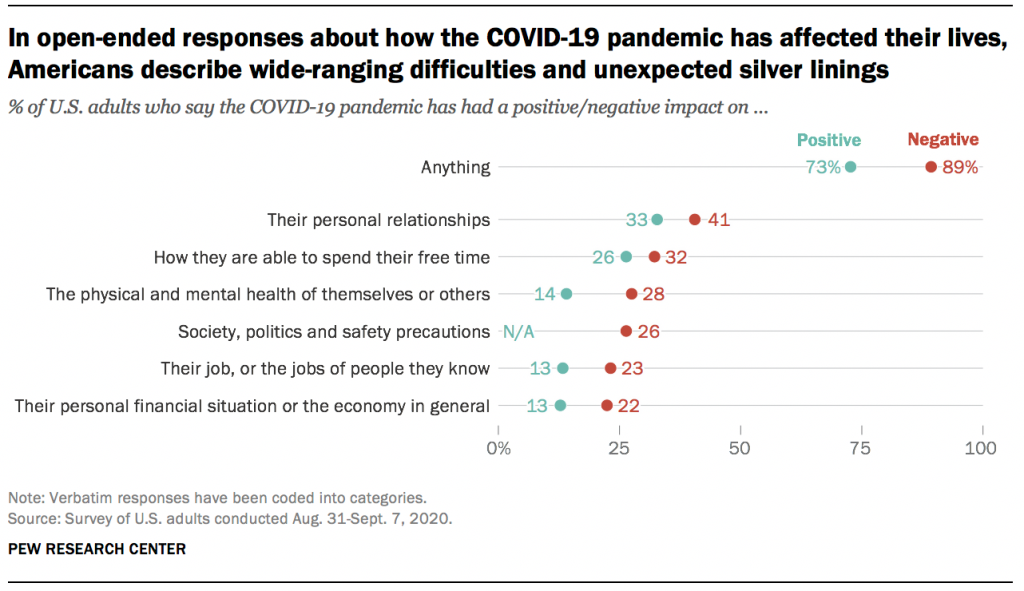

The vast majority of Americans (89%) mentioned at least one negative change in their own lives, while a smaller share (though still a 73% majority) mentioned at least one unexpected upside. Most have experienced these negative impacts and silver linings simultaneously: Two-thirds (67%) of Americans mentioned at least one negative and at least one positive change since the pandemic began.

For this analysis, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31-Sept. 7, 2020. Everyone who completed the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents to the survey were asked to describe in their own words how their lives have been difficult or challenging since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, and to describe any positive aspects of the situation they have personally experienced as well. Overall, 84% of respondents provided an answer to one or both of the questions. The Center then categorized a random sample of 4,071 of their answers using a combination of in-house human coders, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and keyword-based pattern matching. The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

In many ways, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives – an unsurprising reaction to a pandemic that had killed more than 180,000 Americans at the time the survey was conducted. Across every major aspect of life mentioned in these responses, a larger share mentioned a negative impact than mentioned an unexpected upside. Americans also described the negative aspects of the pandemic in greater detail: On average, negative responses were longer than positive ones (27 vs. 19 words). But for all the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, a majority of Americans were able to think of at least one silver lining.

Both the negative and positive impacts described in these responses cover many aspects of life, none of which were mentioned by a majority of Americans. Instead, the responses reveal a pandemic that has affected Americans’ lives in a variety of ways, of which there is no “typical” experience. Indeed, not all groups seem to have experienced the pandemic equally. For instance, younger and more educated Americans were more likely to mention silver linings, while women were more likely than men to mention challenges or difficulties.

Here are some direct quotes that reveal how Americans are processing the new reality that has upended life across the country.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Open access

- Published: 30 November 2020

Family perspectives of COVID-19 research

- Shelley M. Vanderhout 1 ,

- Catherine S. Birken 2 ,

- Peter Wong 3 ,

- Sarah Kelleher 4 ,

- Shannon Weir 4 &

- Jonathon L. Maguire 1 , 5

Research Involvement and Engagement volume 6 , Article number: 69 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

186k Accesses

20 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has uniquely affected children and families by disrupting routines, changing relationships and roles, and altering usual child care, school and recreational activities. Understanding the way families experience these changes from parents’ perspectives may help to guide research on the effects of COVID-19 among children.

As a multidisciplinary team of child health researchers, we assembled a group of nine parents to identify concerns, raise questions, and voice perspectives to inform COVID-19 research for children and families. Parents provided a range of insightful perspectives, ideas for research questions, and reflections on their experiences during the pandemic.

Including parents as partners in early stages of COVID-19 research helped determine priorities, led to more feasible data collection methods, and hopefully has improved the relevance, applicability and value of research findings to parents and children.

Peer Review reports

Plain English summary

Understanding the physical, mental, and emotional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic for children and families will help to guide approaches to support families and children during the pandemic and after. As a team of child health researchers in Toronto, Canada, we assembled a group of parents and clinician researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic to identify concerns, raise questions, and voice perspectives to inform COVID-19 research for children and families. Parents were eager to share their experience of shifting roles, priorities, and routines during the pandemic, and were instrumental in guiding research priorities and methods to understand of the effects of COVID-19 on families. First-hand experience that parents have in navigating the COVID-19 pandemic with their families contributed to collaborative relationships between researchers and research participants, helped orient research about COVID-19 in children around family priorities, and offered valuable perspectives for the development of guidelines for safe return to school and childcare. Partnerships between researchers and families in designing and delivering COVID-19 research may lead to a better understanding of how health research can best support children and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Children and families have been uniquely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. While children appear to experience milder symptoms from COVID-19 infection than older individuals [ 1 ], sudden changes in routines, resources, and relationships as a result of restrictions on physical interaction have resulted in major impacts on families with young children. In the absence of school, child care, extra-curricular activities and family gatherings, children’s social and support networks have been broadly disrupted. Stress from COVID-19 has been compounded by additional responsibilities for parents as they adapt to their new roles as educators and playmates while balancing full-time caregiving with their own stressful changes to work, financial and social situations. On the contrary, families with greater parental support and perceived control have had less perceived stress during COVID-19 [ 2 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly sparked research activity across the globe. Patient and family voices are increasingly considered essential to research agenda and priority setting [ 3 ]. Understanding the physical, mental, and emotional consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for families will inform approaches to support parents and children during the pandemic and after. In this unusual time, patient and family voices can be valuable in informing health research priorities, study designs, implementation plans and knowledge translation strategies that directly affect them [ 4 ].

As a multidisciplinary team of child health researchers with expertise in general paediatrics, nutrition and mental health, we assembled a group of nine parents to identify concerns, raise questions, and voice perspectives to inform COVID-19 research for children and families. Parents were recruited from the TARGet Kids! primary care research network [ 5 ], which is a collaboration between applied health researchers at the SickKids and St. Michael’s Hospitals, primary care providers from the Departments of Pediatrics and Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, and families. Parents were contacted by email and invited to voluntary meetings on April 7 and 23, 2020 via Zoom [ 6 ] for 3 h. In an unstructured discussion, we asked how parents imagined research about COVID-19 could make an impact on child and family well-being. Parents were encouraged to share their lived experience and perspectives on the anticipated effects of COVID-19 and social distancing policies on their children and families, and opinions to inform how research on child mental and physical health during and after the pandemic could best be conducted. Parents had opportunities to review proposed data collection tools such as smartphone apps and serology testing devices, and provided feedback about the feasibility and meaningfulness of each. Content, frequency and organization of questionnaires were also reviewed by parents to ensure they were appropriate in length and feasible to complete.

Parent perspectives

Parents were optimistic that research would provide an understanding of the effects of COVID-19 on families and deliver solutions to minimize negative effects and bolster positive effects. Parents wondered about several questions which they hoped research would answer including: What will be the effects of physical distancing and disrupted routines for my children? How can I help my children develop healthy coping habits? How can I appropriately talk about the virus with my children? What factors might predict resiliency against negative effects of the pandemic among children and families, and how can these be strengthened?

Parents speculated what risks children might face as a result of schoolwork transitioning to home, educational activities provided online, child care being limited or unavailable, social relationships changing, sports and extra-curricular activities being cancelled, and stress and anxiety increasing at home. Some parents reflected on feeling some relief from not having to coordinate usual extracurricular activities. However, they expressed frustration in finding high quality educational activities and resources to support physical and mental health for their children during physical isolation. Parents voiced a need for a centralized, accessible hub with peer reviewed, high quality resources to keep children entertained and supported while spending more time indoors, away from usual activities and school. They hoped for resources to help families adjust to new routines and roles, as well as answer children’s questions in truthful ways that would not increase anxiety.

Parents were curious about studying the impact of COVID-19 on children and families. How would researchers use information about children who are affected physically, mentally, or socially by the pandemic? What could be the possible implications of testing for COVID-19 on social relationships and parents’ employment? This question generated discussion about difficult positions families of lower socio-economic status, who may need to maintain attendance at work but have a suspected COVID-19 infected household member. Would health and social care for children going forward reflect the unique ways they had been impacted by changes in their daily routines and relationships? How can families return to school and everyday routines with a minimum of disruption? What will be done to prepare children and families for emergency situations in the future? Considering these questions may lead child health researchers to study relevant and contemporary concepts to families during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When presented with options to include more measures on other family members, parents maintained that the focus of our COVID-19 research should be on children. Parents provided essential feedback about the length and frequency of questionnaires, to ensure they were appropriate given the limited time available for completing them. Parent involvement early in the research process helped to direct research priorities, informed data collection strategies and hopefully has increased the relevance of research conducted for children and families. Conducting a follow-up meeting with parents was important to understand shifting concerns and ensure data collection was reflecting current routines, habits and policies affecting families.

Conclusions

As researchers who are seeking to understand the impact of COVID-19 on children and families, we felt it important to involve families in designing and implementing new research. First-hand experience that parents have in navigating the COVID-19 pandemic with their children contributed to co-building between researchers and research participants. Parents were generous with their time and provided insightful, honest suggestions for how researchers could create knowledge that would be directly relevant to them. Next steps will include expanding our dialogue with a more diverse group of parents in terms of gender, as all parents in our meetings were women, and ethnicity to better represent the diversity of Toronto. Other researchers conducting COVID-19 research among children and families may consider engaging parents and caregivers in preliminary stages to identify priorities, understand lived experiences and help guide all stages of the research process. This presents value in focusing research on the most important priorities for families and developing data collection methods which are feasible in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the nature of the COVID-19 pandemic is dynamic, ongoing communication between researchers and parents to understand changing perspectives and concerns is important to respond to family needs. We hope that ongoing partnerships between parents and researchers will promote leadership among parents as co-investigators in COVID-19 research, and result in research which addresses the needs of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ideally, engaging with families in COVID-19 research will result in findings that will be valuable to families, assist them in developing collective resilience, and provide a foundation for family-oriented research throughout the COVD-19 pandemic and beyond.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Lee PI, Hu YL, Chen PY, Huang YC, Hsueh PR. Are children less susceptible to COVID-19? J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53(3):371.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Pena S, Watamura SE, Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;1:104699.

Article Google Scholar

Manafo E, Petermann L, Vandall-Walker V, Mason-Lai P. Patient and public engagement in priority setting: a systematic rapid review of the literature. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193579.

Strategy for Patient Oriented Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research - Patient Engagement Framework. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html-a7 . Published 2019. Accessed 2020.

Carsley S, Borkhoff CM, Maguire JL, et al. Cohort profile: the applied research Group for Kids (TARGet kids!). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;44(3):776.

Zoom [computer program]. Version 2.0.02020.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the TARGet Kids! Parent And Clinician Team for their generous contribution of time and participation in discussions about COVID-19 in children and families.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

There is no funding source for this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, 209 Victoria St, Toronto, ON, M5B 1T8, Canada

Shelley M. Vanderhout & Jonathon L. Maguire

Division of Paediatric Medicine and the Paediatric Outcomes Research Team, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1X8, Canada

Catherine S. Birken

Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children, Peter Gilgan Centre for Research & Learning, 686 Bay Street, 11th floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 0A4, Canada

Patient partners, Toronto, Canada

Sarah Kelleher & Shannon Weir

Toronto, Canada

Jonathon L. Maguire

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Shelley Vanderhout, Catherine Birken, Peter Wong, Shannon Weir, Sarah Kelleher and Jonathon Maguire participated in the concept and design, drafting and revising of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jonathon L. Maguire .

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors have no competing interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Vanderhout, S.M., Birken, C.S., Wong, P. et al. Family perspectives of COVID-19 research. Res Involv Engagem 6 , 69 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00242-1

Download citation

Received : 18 August 2020

Accepted : 24 November 2020

Published : 30 November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00242-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Research Involvement and Engagement

ISSN: 2056-7529

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 January 2021

The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic

- Ruta Clair ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9828-9911 1 ,

- Maya Gordon 1 ,

- Matthew Kroon 1 &

- Carolyn Reilly 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 28 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

98k Accesses

148 Citations

161 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health humanities

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic placed many locations under ‘stay at home” orders and adults simultaneously underwent a form of social isolation that is unprecedented in the modern world. Perceived social isolation can have a significant effect on health and well-being. Further, one can live with others and still experience perceived social isolation. However, there is limited research on psychological well-being during a pandemic. In addition, much of the research is limited to older adult samples. This study examined the effects of perceived social isolation in adults across the age span. Specifically, this study documented the prevalence of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the various factors that contribute to individuals of all ages feeling more or less isolated while they are required to maintain physical distancing for an extended period of time. Survey data was collected from 309 adults who ranged in age from 18 to 84. The measure consisted of a 42 item survey from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, Measures of Social Isolation (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ), and items specifically about the pandemic and demographics. Items included both Likert scale items and open-ended questions. A “snowball” data collection process was used to build the sample. While the entire sample reported at least some perceived social isolation, young adults reported the highest levels of isolation, χ 2 (2) = 27.36, p < 0.001. Perceived social isolation was associated with poor life satisfaction across all domains, as well as work-related stress, and lower trust of institutions. Higher levels of substance use as a coping strategy was also related to higher perceived social isolation. Respondents reporting higher levels of subjective personal risk for COVID-19 also reported higher perceived social isolation. The experience of perceived social isolation has significant negative consequences related to psychological well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Loneliness trajectories over three decades are associated with conspiracist worldviews in midlife

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

Introduction.

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, prompting most governors in the United States to issue stay-at-home orders in an effort to minimize the spread of COVID-19. This was after several months of similar quarantine orders in countries throughout Asia and Europe. As a result, a unique situation arose, in which most of the world’s population was confined to their homes, with only medical staff and other essential workers being allowed to leave their homes on a regular basis. Several studies of previous quarantine episodes have shown that psychological stress reactions may emerge from the experience of physical and social isolation (Brooks et al., 2020 ). In addition to the stress that might arise with social isolation or being restricted to your home, there is also the stress of worrying about contracting COVID-19 and losing loved ones to the disease (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). For many families, this stress is compounded by the challenge of working from home while also caring for children whose schools had been closed in an effort to slow the spread of the disease. While the effects of social isolation has been reported in the literature, little is known about the effects of social isolation during a global pandemic (Galea et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ).

Social isolation is a multi-dimensional construct that can be defined as the inadequate quantity and/or quality of interactions with other people, including those interactions that occur at the individual, group, and/or community level (Nicholson, 2012 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Umberson and Karas Montez, 2010 ; Zavaleta et al., 2017 ). Some measures of social isolation focus on external isolation which refers to the frequency of contact or interactions with other people. Other measures focus on internal or perceived social isolation which refers to the person’s perceptions of loneliness, trust, and satisfaction with their relationships. This distinction is important because a person can have the subjective experience of being isolated even when they have frequent contact with other people and conversely they may not feel isolated even when their contact with others is limited (Hughes et al., 2004 ).

When considering the effects of social isolation, it is important to note that the majority of the existing research has focused on the elderly population (Nyqvist et al., 2016 ). This is likely because older adulthood is a time when external isolation is more likely due to various circumstances such as retirement, and limited physical mobility (Umberson and Karas Montez, 2010 ). During the COVID-19 pandemic the need for physical distancing due to virus mitigation efforts has exacerbated the isolation of many older adults (Berg-Weger and Morley, 2020 ; Smith et al., 2020 ) and has exposed younger adults to a similar experience (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). Notably, a few studies have found that young adults report higher levels of loneliness (perceived social isolation) even though their social networks are larger (Child and Lawton, 2019 ; Nyqvist et al., 2016 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ); thus indicating that age may be an important factor to consider in determining how long-term distancing due to COVID-19 will influence people’s perceptions of being socially isolated.

The general pattern in this research is that increased social isolation is associated with decreased life satisfaction, higher levels of depression, and lower levels of psychological well-being (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2014 ; Coutin and Knapp, 2017 ; Dahlberg and McKee, 2018 ; Harasemiw et al., 2018 ; Lee and Cagle, 2018 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). Individuals who experience high levels of social isolation may engage in self-protective thinking that can lead to a negative outlook impacting the way individuals interact with others (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2014 ). Further, restricting social networks and experiencing elevated levels of social isolation act as mediators that result in elevated negative mood and lower satisfaction with life factors (Harasemiw et al., 2018 ; Zheng et al., 2020 ). The relationship between well-being and feelings of control and satisfaction with one’s environment are related to psychological health (Zheng et al., 2020 ). Dissatisfaction with one’s home, resource scarcity such as food and self-care products, and job instability contribute to social isolation and poor well-being (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ).

Although there are fewer studies with young and middle aged adults, there is some evidence of a similar pattern of greater isolation being associated with negative psychological outcomes for this population (Bergin and Pakenham, 2015 ; Elphinstone, 2018 ; Liu et al., 2019 ; Nicholson, 2012 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). There is also considerable evidence that social isolation can have a detrimental impact on physical health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010 ; Steptoe et al., 2013 ). In a meta-analysis of 148 studies examining connections between social relationships and risk of mortality, Holt-Lunstad et al. ( 2010 ) concluded that the influence of social relationships on the risk for death is comparable to the risk caused by other factors like smoking and alcohol use, and greater than the risk associated with obesity and lack of exercise. Likewise, other researchers have highlighted the detrimental impact of social isolation and loneliness on various illnesses, including cardiovascular, inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and cognitive disorders (Bhatti and Haq, 2017 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). Understanding behavioral factors related to positive and negative copings is essential in providing health guidance to adult populations.

Feelings of belonging and social connection are related to life satisfaction in older adults (Hawton et al., 2011 ; Mellor et al., 2008 ; Nicholson, 2012 ; Victor et al., 2000 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). While physical distancing initiatives were implemented to save lives by reducing the spread of COVID-19, these results suggest that social isolation can have a negative impact on both mental and physical health that may linger beyond the mitigation orders (Berg-Weger and Morley, 2020 ; Brooks et al., 2020 ; Cava et al., 2005 ; Smith et al., 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). It is therefore important that we document the prevalence of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the various factors that contribute to individuals of all ages feeling more or less isolated, while they are required to maintain physical distancing for an extended period of time. It was hypothesized that perceived social isolation would not be limited to an older adult population. Further, it was hypothesized that perceived social isolation would be related to individual’s coping with the pandemic. Finally, it was hypothesized that the experience of social isolation would act as a mediator to life satisfaction and basic trust in institutions for individuals across the adult lifespan. The current study was designed to examine the following research questions:

Are there age differences in participants’ perceived social isolation?

Do factors like time spent under required distancing and worry about personal risk for illness have an association with perceived social isolation?

Is perceived social isolation due to quarantine and pandemic mitigation efforts related to life satisfaction?

Is there an association between perceived social isolation and trust of institutions?

Is there a difference in basic stressors and coping during the pandemic for individuals experiencing varying levels of perceived social isolation?

Participants

Participants were adults age 18 years and above. Individuals younger than 18 years were not eligible to participate in the study. There were no limitations on occupation, education, or time under mandatory “stay at home” orders. The researchers sought a sample of adults that was diverse by age, occupation, and ethnicity. The researchers sought a broad sample that would allow researchers to conduct a descriptive quantitative survey study examining factors related to perceived social isolation during the first months of the COVID-19 mitigation efforts.

Participants were asked to complete a 42-item electronic survey that consisted of both Likert-type items and open-ended questions. There were 20 Likert scale items, 3 items on a 3-point scale (1 = Hardly ever to 3 = Often) and 17 items on a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all satisfied to 4 = very satisfied, 0 = I don’t know), 11 multiple choice items, one of which had an available short response answer, and 11 short answer items.

Items were selected from Measures of Social Isolation (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ) that included 27 items to measure feelings of social isolation through the proxy variables of stress, trust, and life satisfaction. Trust was measured for government, business, and media. Life satisfaction examined overall feelings of satisfaction as well as satisfaction with resources such as food, housing, work, and relationships. Three items related to social isolation were chosen from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale. Hughes et al. ( 2004 ) reported that these three items showed good psychometric validity and reliability for the construct of Loneliness.

There were a further 12 items from the authors specifically about circumstances regarding COVID-19 at the time of the survey. Participants answered questions about the length of time spent distancing from others, level of compliance with local regulations, primary news sources, whether physical distancing was voluntary or mandatory, how many people are in their household, work availability, methods of communication, feelings of personal risk of contracting COVID-19, possible changes in behavior, coping methods, stressors, and whether there are children over the age of 18 staying in the home.

This study was submitted to the Cabrini University Institutional Review Board and approval was obtained in March 2020. Researchers recruited a sample of people that varied by age, gender, and ethnicity by identifying potential participants across academic and non-academic settings using professional contact lists. A “snowball” approach to data gathering was used. The researchers sent the survey to a broad group of adults and requested that the participants send the survey to others they felt would be interested in taking part in research. Recipients received an email that contained a description of the purpose of the study and how the data would be used. Included at the end of the email was a link to the online survey that first presented the study’s consent form. Participants acknowledged informed consent and agreed to participate by opening and completing the survey.

At the end of the survey, participants were given the opportunity to supply an email to participate in a longitudinal study which consists of completing surveys at later dates. In addition, the sample was asked to forward the survey to their contacts who might be interested. Overall, the study took ~10 min to complete.

Demographics

Participants were 309 adults who ranged in age from 18 to 84 ( M = 38.54, s = 18.27). Data was collected beginning in 2020 from late March until early April. At the time of data collection distancing mandates were in place for 64.7% and voluntary for 34.6% of the sample, while 0.6% lived in places which had not yet outlined any pandemic mitigation policies. The average length of time distancing was slightly more than 2 weeks ( M = 14.91 days, s = 4.5) with 30 days as the longest reported time.

The sample identified mostly as female (80.3%), with males (17.8%) and those who preferred not to answer (1.9%) representing smaller numbers. The majority of the sample identified as Caucasian (71.5%). Other ethnic identities reported by participants included Hispanic/Latinx, African-American/Black, Asian/East Asian, Jewish/Jewish White-Passing, Multiracial/Multiethnic, and Country of Origin (Table 1 ). Individuals resided in the United States and Europe.

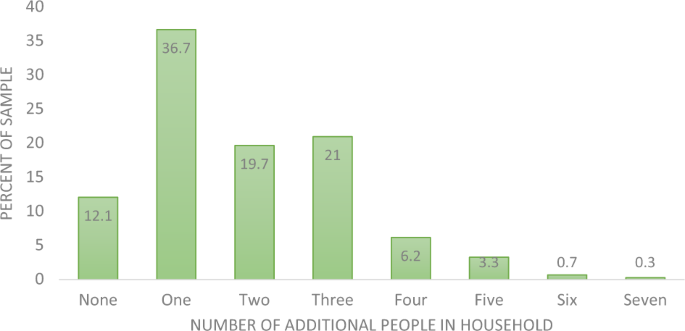

The majority of the sample lived in households with others (Fig. 1 ). More than one-third (36.7%) lived with one other person, 19.7% lived with two others, and 21% lived with three other people. People living alone comprised 12.1% of the sample. When asked about the presence of children under 18 years of age in the home, 20.5% answered yes.

Figure shows how many additional individuals live in the participant’s household in March 2020.

The highest level of education attained ranged from completion of lower secondary school (0.3%) to doctoral level (6.8%). Two thirds of the sample consisted of individuals with a Bachelor’s degree or above (Table 2 ).

Participants were asked to provide their occupation. The largest group identified themselves as professionals (26.5%), while 38.6% reported their field of work (Table 3 ). Students comprised 23.1% of the sample, while 11.1% reported that they were retired. Some of the occupations reported by the sample included nurses and physicians, lawyers, psychologists, teachers, mental health professionals, retail sales, government work, homemakers, artists across types of media, financial analysts, hairdresser, and veterinary support personnel. One person indicated that they were unemployed prior to the pandemic.

Social isolation and demographics

Spearman’s rank-order correlations were used to examine relationships between the three Likert scale items from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale that measure social isolation. Feeling isolated from others was significantly correlated with lacking companionship ( r s = 0.45, p < 0.001) and feeling left out ( r s = 0.43, p < 0.001). The items related to lacking companionship and feeling left out were also significantly correlated ( r s = 0.39, p < 0.001).

Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to determine if the variables of time in required distancing and age were each related to the three levels of social isolation (hardly, sometimes, often). There were no significant findings between perceived social isolation and length of time in required distancing, χ 2 (2) = 0.024, p = 0.98.

A significant relationship was found between perceived social isolation and age, χ 2 (2) = 27.36, p < 0.001). Subsequently, pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s procedure with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p values are presented. Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in age between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 25) and some social isolation (Mdn = 31) ( p = <0.001) and low isolation (Mdn = 46) ( p = 0.002). Higher levels of social isolation were associated with younger age.

Age was then grouped (18–29, 30–49, 50–69, 70+) and a significant relationship was found between social isolation and age, χ 2 (3) = 13.78, p = 0.003). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in perceived social isolation across age groups. The youngest adults (age 18–29) reported significantly higher social isolation (Mdn = 2.4) than the two oldest groups (50–69 year olds: Mdn = 1.6, p = 004); age 70 and above: Mdn = 1.57), p = 0.01). The difference between the youngest adults and the next youngest (30–49) was not significant ( p = 0.09).

When asked if participants feel personally at risk for contracting SARS-CoV-2 61.2% reported that they feel at risk. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who reported feeling at risk and those who did not feel at risk. Individuals who feel at risk for infection reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.0) than those that do not feel at risk (Mdn = 1.75), U = 9377, z = −2.43, p = 0.015.

Social isolation and life satisfaction

The relationship between level of social isolation and overall life satisfaction were examined using Kruskal–Wallis tests as the measure consisted of Likert-type items (Table 4 ).

Overall life satisfaction was significantly lower for those who reported greater social isolation ( χ 2 (2) = 50.56, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in life satisfaction scores between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 2.82) and some social isolation (Mdn = 3.04) ( p ≤ 0.001) and between high and low isolation (Mdn = 3.47) ( p ≤ 0.001), but not between high levels of social isolation and some social isolation ( p = 0.09).

The pandemic added concern about access to resources such as food and 68% of the sample reported stress related to availability of resources. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and satisfaction with access to food, χ 2 (2) = 21.92, p < 0.001). Individuals reporting high levels of social isolation were the least satisfied with their food situation. Statistical difference were evident between high social isolation (Mdn = 3.28) and some social isolation (Mdn = 3.46) ( p = 0.003) and between high and low isolation (Mdn = 3.69) ( p < 0.001). Reporting higher levels of social isolation is associated with lower satisfaction with food.

As a result of stay at home orders, many participants were spending more time in their residences than prior to the pandemic. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and housing satisfaction, χ 2 (2) = 10.33, p = 0.006). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically a significant difference in housing satisfaction between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 3.49) and low social isolation (Mdn = 3.75) ( p = 0.006). Higher levels of social isolation is associated with lower levels of satisfaction with housing.

Work life changed for many participants and 22% of participants reported job loss as a result of the pandemic. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and work satisfaction, χ 2 (2) = 21.40, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed individuals reporting high social isolation reported much lower satisfaction with work (Mdn = 2.53) than did those reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 3.27) ( p < 0.001) and moderate social isolation (Mdn = 3.03) ( p = 0.003).

Social isolation and trust of institutions

The relationship between social isolation and connection to community was measured using a Kruskal–Wallis test. A significant relationship was found between feelings of social isolation and connection to community ( χ 2 (2) = 13.97, p = 0.001. Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in connection to community such that the group reporting higher social isolation (Mdn = 2.27, p = 0.001) reports less connection to their community than the group reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 2.93).

A significant relationship was found between social isolation and trust of central government institutions, χ 2 (2) = 10.46, p = 0.005). Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in trust of central government between individuals reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 2.91) and those reporting high social isolation (Mdn = 2.32) ( p = 0.008) and moderate social isolation (Mdn = 2.48) ( p = 0.03). There was less trust of central government for the group reporting high social isolation. However, distrust of central government did not extend to local government institutions. There was no significant difference in trust of local government for low, moderate, and high social isolation groups, χ 2 (2) = 5.92, p = 0.052.

Trust levels of business was significantly different between groups that differed in feelings of social isolation, χ 2 (2) = 9.58, p = 0.008). Post hoc analysis revealed more trust of business institutions for the low social isolation group (Mdn = 3.10) compared to the group reporting high social isolation (Mdn = 2.62) ( p = 0.007).

Sixty-seven participants reported loss of a job as a result of COVID-19. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who had lost their job to those who had not. Individuals who experienced job loss reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.26) than those that did not lose their job (Mdn = 1.80), U = 5819.5, z = −3.66 , p < 0.001.

Stress related to caring for an elderly family member was identified by 12% of the sample. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who reported that caring for an elderly family member is a stressor to those who had not. There was no significant finding, U = 4483, z = −1.28, p = 0.20. Similarly, there was no significant effect for caring for a child, U = 3568.5, z = −0.48, p = 0.63.

Coping strategies

Participants were asked to check off whether they were using virtual communication, exercise, going outdoors, and/or substances in order to cope with the challenges of distancing during pandemic. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who used substances as a coping strategy and those that did not. Individuals who reported substance use reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.12) than those that did not (Mdn = 1.80), U = 6724, z = −2.01, p = 0.04.

There was no significant difference on Mann–Whitney U test for social isolation between those individuals who went outdoors to cope with pandemic versus those that did not, U = 5416, z = −0.72, p = 0.47. Similarly, there was no difference in social isolation between those individuals who used exercise as a coping tool and those that did not. Finally, there was no difference in social isolation between those that used virtual communication tools and those that did not, U = 7839.5, z = −0.56, p = 0.58. The only coping strategy which was significantly associated with social isolation was substance use.

While research has explored the subjective experience of social isolation, the novel experience of mass physical distancing as a result of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic suggests that social isolation is a significant factor in the public health crisis. The experience of social isolation has been examined in older populations but less often in middle-age and younger adults (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). Perceived social isolation is related to numerous negative outcomes related to both physical and mental health (Bhatti and Haq, 2017 ; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010 , Victor et al., 2000 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). Our findings indicate that younger adults in their 20s reported more social isolation than did those individuals aged 50 and older during physical distancing. This supports the findings of Nyqvist et al. ( 2016 ) that found teenagers and young adults in Finland reported greater loneliness than did older adults.

The experience of social isolation is related to a reduction in life satisfaction. Previous research has shown that feelings of social connection are related to general life satisfaction in older adults (Hawton et al., 2011 , Hughes et al., 2004 , Mellor et al., 2008 ; Victor et al., 2000 , Xia and Li, 2018 ). These findings indicate that perceived social isolation can be a significant mediator in life satisfaction and well-being across the adult lifespan during a global health crisis. Individuals reporting higher levels of social isolation experience less satisfaction with the conditions in their home.

During mandated “stay-at-home” conditions, the experience of work changed for many people. For many adults work is an essential aspect of identity and life satisfaction. The experience of individuals reporting elevated social isolation was also related to lower satisfaction with work. This study included a wide span of occupations involving both individuals required to work from home and essential workers continuing to work outside the home. Further, ~22% of the sample ( n = 67) reported job loss as a stressor related to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and reported elevated social isolation. As institutions and businesses consider whether remote work is an economically viable alternative to face-to-face offices once physical distancing mandates are ended, the needs of workers for social interaction should be considered.

Further, individuals reporting higher social isolation also indicated less connection to their community and lower satisfaction with environmental factors such as housing and food. Findings indicate that higher perceived social isolation is associated with broad dissatisfaction across social and life domains and perceptions of personal risk from COVID-19. This supports research that identified a relationship between social isolation and health-related quality of life outcomes (Hawton et al., 2011 , Victor et al., 2000 ). Perceptions of elevated social isolation are related to lower life satisfaction in functional and social domains.

Perceived social isolation is likewise related to trust of some institutions. While there was no effect for local government, individuals with higher perceived social isolation reported less trust of central government and of business. There is an association between higher levels of perceived social isolation and less connection to the community, lower life satisfaction, and less trust of large-scale institutions such as central government and businesses. As a result, the individuals who need the most support may be the most suspicious of the effectiveness of those institutions.

Coping strategies related to exercise, time spent outdoors, and virtual communication were not related to social isolation. However, individuals who reported using substances as a coping strategy reported significantly higher social isolation than did the group who did not indicate substance use as a coping strategy. Perceived social isolation was associated with negative coping rather than positive coping. This study shows that clinicians and health care providers should ask about coping strategies in order to provide effective supports for individuals.

There are several limitations that may limit the generalizability of the findings. The study is heavily female and this may have an effect on findings. In addition, the majority of the sample has a post-secondary degree and, as such, this study may not accurately reflect the broad experience of individuals during pandemic. Further, it cannot be ruled out that individuals reporting high levels of perceived social isolation may have experienced some social isolation prior to the pandemic.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study suggests that perceived social isolation is a significant element of health-related quality of life during pandemic. Perceived social isolation is not just an issue for older adults. Indeed, young adults appear to be suffering greatly from the distancing required to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The experience of social isolation is associated with poor life satisfaction across domains, work-related stress, lower trust of institutions such as central government and business, perceived personal risk for COVID-19, and higher levels of use of substances as a coping strategy. Measuring the degree of perceived social isolation is an important addition to wellness assessments. Stress and social isolation can impact health and immune function and so reducing perceived social isolation is essential during a time when individuals require strong immune function to fight off a novel virus. Further, it is anticipated that these widespread effects may linger as the uncertainty of the virus continues. As a result, we plan to follow participants for at least a year to examine the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the well-being of adults.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and analyzed during the current study is not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and privacy agreements between the authors and participants.

Berg-Weger M, Morley J (2020) Loneliness and social isolation in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for gerontological social work. J Nutr Health Aging 24(5):456–458

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bergin A, Pakenham K (2015) Law student stress: relationships between academic demands, social isolation, career pressure, study/life imbalance, and adjustment outcomes in law students. Psychiatry Psychol Law 22:388–406

Article Google Scholar

Bhatti A, Haq A (2017) The pathophysiology of perceived social isolation: effects on health and mortality. Cureus 9(1):e994. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.994

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brooks S, Webster R, Smith L, Woodland L, Wesseley S, Greenberg N, Rubin G (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395:912–920

Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S (2014) Social relationships and health: the toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 8(2):58–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12087

Cava M, Fay K, Beanlands H, McCay E, Wignall R (2005) The experience of quarantine for individuals affected by SARS in Toronto. Public Health Nurs 22(5):398–406

Child ST, Lawton L (2019) Loneliness and social isolation among young and late middle age adults: associations with personal networks and social participation. Aging Mental Health 23:196–204

Coutin E, Knapp M (2017) Social isolation, loneliness, and health in old age. Health Soc Care Community 25:799–812

Dahlberg L, McKee KJ (2018) Social exclusion and well-being among older adults in rural and urban areas. Arch Gerontol Geriatrics 79:176–184

Elphinstone B (2018) Identification of a suitable short-form of the UCLA-Loneliness Scale. Austral Psychol 53:107–115

Galea S, Merchant R, Lurie N (2020) The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med 180(6):817–818

Harasemiw O, Newall N, Mackenzie CS, Shooshtari S, Menec V (2018) Is the association between social network types, depressive symptoms and life satisfaction mediated by the perceived availability of social support? A cross-sectional analysis using the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Aging Mental Health 23:1413–1422

Hawton A, Green C, Dickens A, Richards C, Taylor R, Edwards R, Greaves C, Campbell J (2011) The impact of social isolation on the health status and health-related quality of life of older people. Qual Life Res 20:57–67

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7:1–20

Hughes M, Waite L, Hawkley L, Cacioppo J (2004) A short scale of measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging 26(6):655–672

Lee J, Cagle JG (2018) Social exclusion factors influencing life satisfaction among older adults. J Poverty Soc Justice 26:35–50

Liu H, Zhang M, Yang Q, Yu B (2019) Gender differences in the influence of social isolation and loneliness on depressive symptoms in college students: a longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55:251–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01726-6

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mellor D, Stokes M, Firth L, Hayashi Y, Cummins R (2008) Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personal Individ Differ 45(2008):213–218

Nicholson N (2012) A review of social isolation: an important but underassessed condition in older adults. J Prim Prev 33(2–3):137–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2

Nyqvist F, Victor C, Forsman A, Cattan M (2016) The association between social capital and loneliness in different age groups: a population-based study in Western Finland. BMC Public Health 16:542. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3248-x

Smith B, Lim M (2020) How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Res Pract 30(2):e3022008. https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3022008

Smith M, Steinman L, Casey EA (2020). Combatting social isolation among older adults in the time of physical distancing: the COVID-19 social connectivity paradox. Front Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00403

Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J (2013) Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(15):5797–5801. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219686110

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Umberson D, Karas Montez J (2010) Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav 51:S54–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383501

Usher K, Bhullar N, Jackson D (2020). Life in the pandemic: social isolation and mental health. J Clin Nurs https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15290

Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J, Bowling A (2000) Being alone in later life: loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Rev Clin Gerontol 10(4):407–417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259800104101

Xia N, Li H (2018) Loneliness, social isolation, and cardiovascular health. Antioxid Redox Signal 28(9):837–851

Zavaleta D, Samuel K, Mills CT (2017) Measures of social isolation. Soc Indic Res 131(1):367–391

Zheng L, Miao M, Gan Y (2020). Perceived control buffers the effects of the covid-19 pandemic on general health and life satisfaction: the mediating role of psychological distance. Appl Psychol https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12232

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Cabrini University, Radnor, USA

Ruta Clair, Maya Gordon, Matthew Kroon & Carolyn Reilly

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors jointly supervised and contributed to this work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ruta Clair .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Clair, R., Gordon, M., Kroon, M. et al. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 28 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3

Download citation

Received : 29 August 2020

Accepted : 07 January 2021

Published : 27 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Assessing the impact of covid-19 on self-reported levels of depression during the pandemic relative to pre-pandemic among canadian adults.

- Rasha Elamoshy

- Marwa Farag

Archives of Public Health (2024)

Associations between social networks, cognitive function, and quality of life among older adults in long-term care

- Laura Dodds

- Carol Brayne

- Joyce Siette

BMC Geriatrics (2024)

Locked Down: The Gendered Impact of Social Support on Children’s Well-Being Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Jasper Dhoore

- Bram Spruyt

- Jessy Siongers

Child Indicators Research (2024)

Life Satisfaction during the Second Lockdown of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany: The Effects of Local Restrictions and Respondents’ Perceptions about the Pandemic

- Lisa Schmid

- Pablo Christmann

- Carolin Thönnissen

Applied Research in Quality of Life (2024)

From the table to the sofa: The remote work revolution in a context of crises and its consequences on work attitudes and behaviors

- Humberto Batista Xavier

- Suzana Cândido de Barros Sampaio

- Kathryn Cormican

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the impact of the covid-19 pandemic on families: young people’s experiences in estonia.

- 1 Institute of Social Studies, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

- 2 Institute of Cultural Research, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia