"I Have a Dream"

August 28, 1963

Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered at the 28 August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom , synthesized portions of his previous sermons and speeches, with selected statements by other prominent public figures.

King had been drawing on material he used in the “I Have a Dream” speech in his other speeches and sermons for many years. The finale of King’s April 1957 address, “A Realistic Look at the Question of Progress in the Area of Race Relations,” envisioned a “new world,” quoted the song “My Country ’Tis of Thee,” and proclaimed that he had heard “a powerful orator say not so long ago, that … Freedom must ring from every mountain side…. Yes, let it ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado…. Let it ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let it ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let it ring from every mountain and hill of Alabama. From every mountain side, let freedom ring” ( Papers 4:178–179 ).

In King’s 1959 sermon “Unfulfilled Hopes,” he describes the life of the apostle Paul as one of “unfulfilled hopes and shattered dreams” ( Papers 6:360 ). He notes that suffering as intense as Paul’s “might make you stronger and bring you closer to the Almighty God,” alluding to a concept he later summarized in “I Have a Dream”: “unearned suffering is redemptive” ( Papers 6:366 ; King, “I Have a Dream,” 84).

In September 1960, King began giving speeches referring directly to the American Dream. In a speech given that month at a conference of the North Carolina branches of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , King referred to the unexecuted clauses of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution and spoke of America as “a dream yet unfulfilled” ( Papers 5:508 ). He advised the crowd that “we must be sure that our struggle is conducted on the highest level of dignity and discipline” and reminded them not to “drink the poisonous wine of hate,” but to use the “way of nonviolence” when taking “direct action” against oppression ( Papers 5:510 ).

King continued to give versions of this speech throughout 1961 and 1962, then calling it “The American Dream.” Two months before the March on Washington, King stood before a throng of 150,000 people at Cobo Hall in Detroit to expound upon making “the American Dream a reality” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 70). King repeatedly exclaimed, “I have a dream this afternoon” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 71). He articulated the words of the prophets Amos and Isaiah, declaring that “justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream,” for “every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 72). As he had done numerous times in the previous two years, King concluded his message imagining the day “when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing with the Negroes in the spiritual of old: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” (King, Address at Freedom Rally , 73).

As King and his advisors prepared his speech for the conclusion of the 1963 march, he solicited suggestions for the text. Clarence Jones offered a metaphor for the unfulfilled promise of constitutional rights for African Americans, which King incorporated into the final text: “America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned” (King, “I Have a Dream,” 82). Several other drafts and suggestions were posed. References to Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation were sustained throughout the countless revisions. King recalled that he did not finish the complete text of the speech until 3:30 A.M. on the morning of 28 August.

Later that day, King stood at the podium overlooking the gathering. Although a typescript version of the speech was made available to the press on the morning of the march, King did not merely read his prepared remarks. He later recalled: “I started out reading the speech, and I read it down to a point … the audience response was wonderful that day…. And all of a sudden this thing came to me that … I’d used many times before.... ‘I have a dream.’ And I just felt that I wanted to use it here … I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn’t come back to it” (King, 29 November 1963).

The following day in the New York Times, James Reston wrote: “Dr. King touched all the themes of the day, only better than anybody else. He was full of the symbolism of Lincoln and Gandhi, and the cadences of the Bible. He was both militant and sad, and he sent the crowd away feeling that the long journey had been worthwhile” (Reston, “‘I Have a Dream …’”).

Carey to King, 7 June 1955, in Papers 2:560–561.

Hansen, The Dream, 2003.

King, Address at the Freedom Rally in Cobo Hall, in A Call to Conscience , ed. Carson and Shepard, 2001.

King, “I Have a Dream,” Address Delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, in A Call to Conscience , ed. Carson and Shepard, 2001.

King, Interview by Donald H. Smith, 29 November 1963, DHSTR-WHi .

King, “The Negro and the American Dream,” Excerpt from Address at the Annual Freedom Mass Meeting of the North Carolina State Conference of Branches of the NAACP, 25 September 1960, in Papers 5:508–511.

King, “A Realistic Look at the Question of Progress in the Area of Race Relations,” Address Delivered at St. Louis Freedom Rally, 10 April 1957, in Papers 4:167–179.

King, Unfulfilled Hopes, 5 April 1959, in Papers 6:359–367.

James Reston, “‘I Have a Dream…’: Peroration by Dr. King Sums Up a Day the Capital Will Remember,” New York Times , 29 August 1963.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Read Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream' speech in its entirety

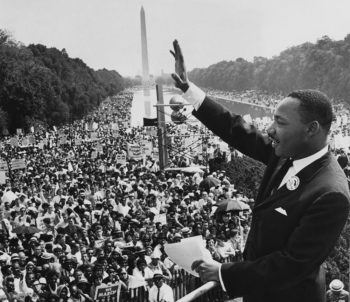

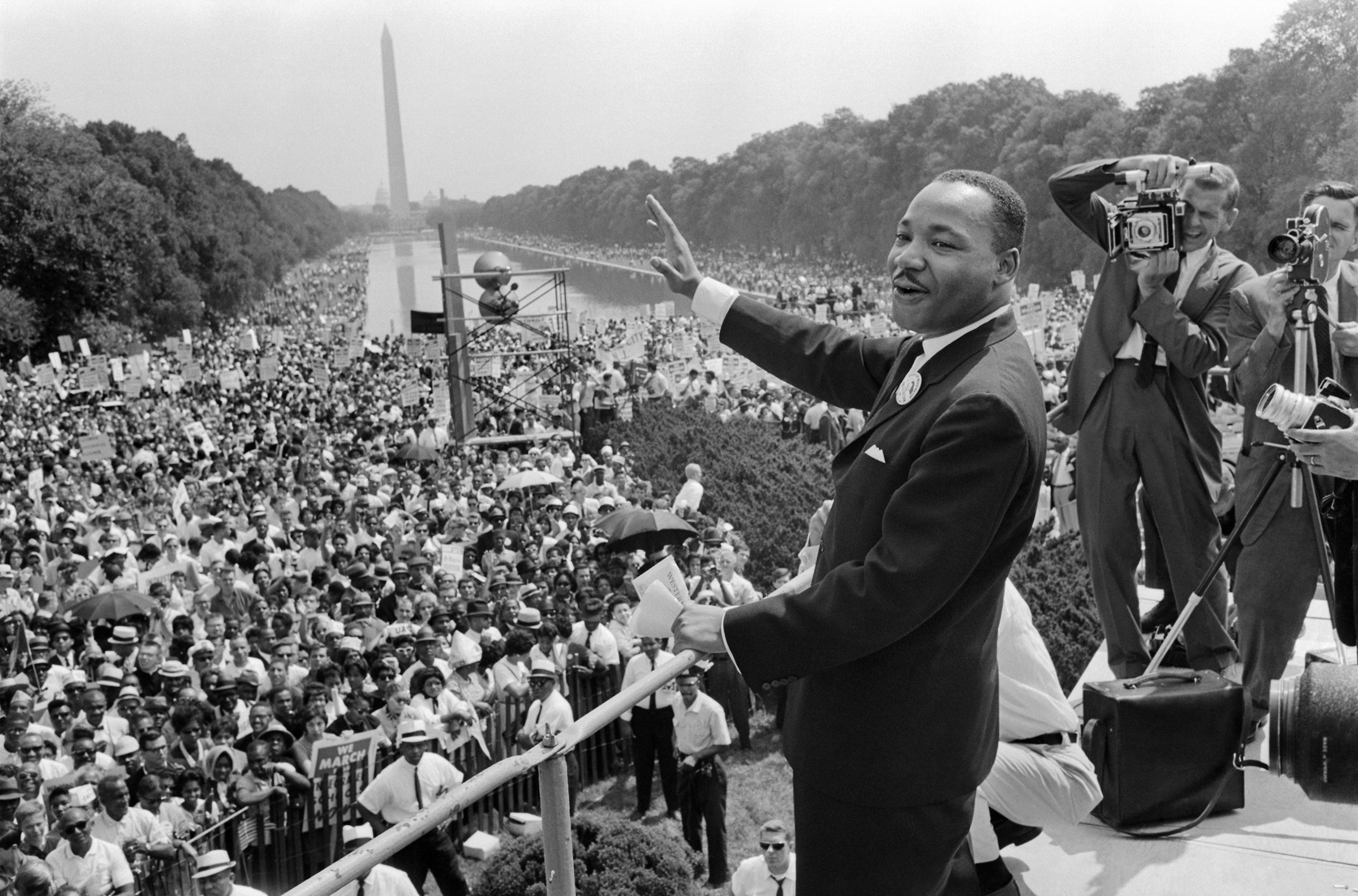

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington. AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington.

Monday marks Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Below is a transcript of his celebrated "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered on Aug. 28, 1963, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. NPR's Talk of the Nation aired the speech in 2010 — listen to that broadcast at the audio link above.

Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders gather before a rally at the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963, in Washington. National Archives/Hulton Archive via Getty Images hide caption

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.: Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check.

Code Switch

The power of martin luther king jr.'s anger.

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

Martin Luther King is not your mascot

We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we've come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

Civil rights protesters march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. Kurt Severin/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

Throughline

Bayard rustin: the man behind the march on washington (2021).

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny.

And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only.

We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

How The Voting Rights Act Came To Be And How It's Changed

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

People clap and sing along to a freedom song between speeches at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Express Newspapers via Getty Images hide caption

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

Nikole Hannah-Jones on the power of collective memory

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.

Correction Jan. 15, 2024

A previous version of this transcript included the line, "We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now." The correct wording is "We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now."

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1963 Speech at Keuka College

Dr. King gave the baccalaureate address on June 16, 1963. Listen now and be a part of history.

- College History

- Service & Social Justice

- Spiritual Life

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is shown delivering the baccalaureate address on the campus of Keuka College on June 16, 1963, in one of the only known color photographs of the event.

Class of this great institution of learning, and ladies and gentlemen. I need not pause to say how very delighted I am to have the privilege and opportunity of being here today and being on the campus of Keuka College. — Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

With those words, Civil Rights icon Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. began the baccalaureate address on the campus of Keuka College on June 16, 1963.

Long thought lost to the ages, a reel-to-reel recording of this historic address was recently returned to Keuka College by a former employee. The approximately 35-minute speech has now been digitally transferred and will be played for the public at a listening event on campus during Black History Month.

Download the Listener's Guide

“Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to our campus was a watershed moment in the College’s history,” said College President Dr. Jorge L. Díaz-Herrera. “So we are thrilled to have the original recording of this stirring speech back in our possession – and even more excited to share it with the public.”

The public broadcast, which is to include a roundtable discussion and reception, is scheduled for 6:30 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 20, in the College’s Norton Chapel. It will be free and open to the public. An earlier public broadcast – scheduled exclusively for students, faculty, and staff of the College – is planned for 12:20 p.m. that day, during Common Hour, also in Norton Chapel. Events will also include a related 4:35 p.m. program, roundtable discussions, and an end-of-the-day reception.

The speech, which centers on King’s famous sermon “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life,” came amid a tumultuous period in the Civil Rights movement. The Birmingham marches against segregation had begun just two months earlier, resulting in King’s arrest on April 12 (Good Friday). It was during this confinement that he wrote his enduring declaration, “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

And fellow Civil Rights leader Medgar Evers had been assassinated just days prior to the address. Indeed, King came to Keuka Park directly from the June 15 Evers funeral in Jackson, Mississippi. He makes note of the event during his speech, after intoning the words of the Civil Rights anthem, “We Shall Overcome”:

“Before the victory’s won some will have to get scarred up a bit. Before the victory’s won maybe some will have to face what the young man whose funeral I attended yesterday afternoon in Jackson, Mississippi, Medgar Evers, faced, and that is physical death. But we shall overcome. Before the victory’s won, maybe some will have to lose our jobs. Before the victory’s won more will have to go to jail. We shall overcome. And I’ll tell you why, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Following his address, King was presented with an honorary Doctor of Letters degree from then-College President Dr. William S. Litterick.

In a July 3 follow-up letter, King thanked President Litterick for the invitation and trustees for the degree: “This is just a note again to express my appreciation to you for making my recent visit to Keuka College so meaningful. Mrs. King and I enjoyed every minute of our visit.”

A little more than two months after his Keuka College address, King would lead the March on Washington, at which he galvanized the nation and the Civil Rights movement with his historic “I Have a Dream” speech.

He was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” in 1963 and, the following year, received the Nobel Peace Prize.

King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, returned to the Keuka College campus in 1970 to receive an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from the College.

You Might Also Like

Digging Deep: Keuka College Students Plant Trees and Foster Connections During Alternative Spring Break

Nearly a dozen students trade relaxation for restoration on a service-oriented spring break trip.

Commemorating a Legacy: Celebrate Service…Celebrate Yates Marks 25 Years of Community Impact

Keuka College Seeks Nominees for Its 2024 Stork Award

Keuka College Honors Bravery, Extends Gratitude at Veterans Day Ceremony

Keuka College, Local Community Mark 24 Years of Service to Yates County

Fribolin Lecture Aims to Spark Conversation and Change Through Art and Activism

What a Team! Jeff and Wendy Gifford Receive Keuka College’s 2021-22 Stork Award

Penn Yan’s Jeff and Wendy Gifford to Receive Keuka College’s Prestigious Stork Award Aug. 11

Keuka College Students Rally for Women's Rights

White House Insider Anita McBride Spotlights History, Influence of First Ladies at Keuka College

Keuka College Marks the Return of Celebrate Service… Celebrate Yates

Explore blog topics.

Digital Humanities

- Projects and Initiatives

- Graduate Certificate

- Full Site Navigation

Finding King’s Speech

Editor’s Note: Earlier versions of this article appeared in our print magazine, Accolades, and online.

For years, Rocky Mount citizens have told tales about hearing the first rendition of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

On Nov. 27, 1962, nine months before the refrain echoed across the National Mall during the March on Washington, King’s words rang out in the gymnasium of a segregated high school in the small North Carolina town.

In a 55-minute address to a packed house of 1,800 residents, King delivered — for the first time — phrases that would ultimately inspire millions.

“So my friends in Rocky Mount, I have a dream tonight,” King declared.

Five decades later, that speech has a new, vastly larger audience. After uncovering and restoring a recording of King’s Rocky Mount speech, NC State English professor Jason Miller is airing the address for the world to hear.

Miller created kingsfirstdream.com , a website where visitors can listen to the audio and read a full transcript, accompanied by 89 interactive annotations that explain the speech’s historical and literary contexts. He hopes the site will draw researchers and students of English, rhetoric, history, politics and social sciences.

However, his most significant find came only an hour and a half from his NC State campus office, at Rocky Mount’s Braswell Memorial Library. A librarian there told Miller she found a reel of acetate tape sitting on her desk when she returned from vacation. Inside a box holding the 1.5 mm recording was a note penned in elegant handwriting: “Dr. Martin Luther King speech — please do not erase.”

When he played it, Miller says he knew he’d found what he was looking for: the complete 1962 Rocky Mount speech, which captures King at the height of his oratorical prowess. Although the recording is similar to King’s 1963 address in Washington, Miller said it’s “incredibly unique,” marking a high point in King’s development of the “dream” motif as a rhetorical device.

Miller should know. He’s spent much of the past decade charting the evolution of King’s “dream” and how it was influenced by Hughes’ poetry.

Jason Miller. Photo credit: Marc Hall.

King-Hughes connection

While it’s clear that Hughes “sparked King’s own poetic self,” Miller says, that influence is hard to trace. Miller pored over Hughes’ poetry and King’s speeches from the early 1960s.

“The ideas from Hughes’ poetry are there, but they’re submerged,” Miller says.

To chart the connections between Hughes and King, Miller bought a piece of butcher’s paper three feet tall and 14 feet long on which he documented “letters exchanged, poems sent, times they met.” Working backward from King’s famous March on Washington address, Miller made a notation for every time King uttered the word “dream” in a speech, publication or correspondence.

The exercise brought Miller back to a speech King delivered on Aug. 11, 1956, when King spoke of the dream while paraphrasing Hughes’ 1941 poem “I Dream a World.” In 1959, King riffed on Hughes’ poem “Harlem (Dream Deferred),” when talking about shattered dreams during a speech. And in January 1960, King had Hughes write a poem about dreams for a special event.

But unlike several speeches that lightly touched on the dream theme, Miller said the Rocky Mount speech is far more than a paraphrased version of Hughes’ ideals; it’s King’s own dream, fully developed and articulated.

“This is the turning point,” Miller says — where Hughes’ utopian ideal is transformed into King’s bold vision for a just society. “He thought of himself in artistic terms, not simply as an orator,” Miller said of King. “When he got up to deliver a speech, he thought of it as his chance to perform. It wasn’t just rhetoric. It wasn’t just a speech. It was a way of bringing poetry into the world of public speaking and communication.”

The King-Hughes Connection

I dream a world where man

No other man will scorn,

Where love will bless the earth

And peace its paths adorn.

I dream a world where all

Will know sweet freedom’s way,

Where greed no longer saps the soul

Nor avarice blights our day.

A world I dream where black or white,

Whatever race you be,

Will share the bounties of the earth

And every man is free,

Where wretchedness will hang its head

And joy, like a pearl,

Attends the needs of all mankind —

Of such I dream, my world!

— “I Dream a World” by Langston Hughes

“So my friends in Rocky Mount, I have a dream tonight. It is a dream rooted firmly in the American dream. I have a dream that one day down in Sasser County, Georgia, where they burned two churches down a few days ago because Negroes wanted to register to vote, one day right down there little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and little white girls and walk the streets as brothers and sisters. I have a dream.”

— Excerpt from King’s 1962 speech in Rocky Mount

- https://dh.news.chass.ncsu.edu/2016/05/12/finding-kings-speech/">

Filed Under

Leave a response cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.

Your response

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Other Top News

Explore queen victoria’s lost garden pavilion through 3d virtual model.

An interdisciplinary team of NC State researchers has virtually reconstructed a lost piece of history.

Interactive Tool Offers Window Into History of Arab-Americans in NYC

Interactive, online tool allows scholars and the public to better understand the long history of Syrian and Lebanese immigrants to the United States.

View the Archive

Why “I Have A Dream” Remains One Of History’s Greatest Speeches

Monday will mark the holiday in honor of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Texas A&M University Professor of Communication Leroy Dorsey is reflecting on King’s celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech, one which he said is a masterful use of rhetorical traditions.

King delivered the famous speech as he stood before a crowd of 250,000 people in front of the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963 during the “March on Washington.” The speech was televised live to an audience of millions.

“He was not just speaking to African Americans, but to all Americans” ~ Leroy Dorsey

Dorsey , associate dean for inclusive excellence and strategic initiatives in the College of Liberal Arts, said one of the reasons the speech stands above all of King’s other speeches – and nearly every other speech ever written – is because its themes are timeless. “It addresses issues that American culture has faced from the beginning of its existence and still faces today: discrimination, broken promises, and the need to believe that things will be better,” he said.

Powerful Use of Rhetorical Devices

Dorsey said the speech is also notable for its use of several rhetorical traditions, namely the Jeremiad, metaphor-use and repetition.

The Jeremiad is a form of early American sermon that narratively moved audiences from recognizing the moral standard set in its past to a damning critique of current events to the need to embrace higher virtues.

“King does that with his invocation of several ‘holy’ American documents such as the Emancipation Proclamation and Declaration of Independence as the markers of what America is supposed to be,” Dorsey said. “Then he moves to the broken promises in the form of injustice and violence. And he then moves to a realization that people need to look to one another’s character and not their skin color for true progress to be made.”

Second, King’s use of metaphors explains U.S. history in a way that is easy to understand, Dorsey said.

“Metaphors can be used to connect an unknown or confusing idea to a known idea for the audience to better understand,” he said. For example, referring to founding U.S. documents as “bad checks” transformed what could have been a complex political treatise into the simpler ideas that the government had broken promises to the American people and that this was not consistent with the promise of equal rights.

The third rhetorical device found in the speech, repetition, is used while juxtaposing contrasting ideas, setting up a rhythm and cadence that keeps the audience engaged and thoughtful, Dorsey said.

“I have a dream” is repeated while contrasting “sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners” and “judged by the content of their character” instead of “judged by the color of their skin.” The device was used also with “let freedom ring” which juxtaposes states that were culturally polar opposites – Colorado, California and New York vs. Georgia, Tennessee and Mississippi.

Words That Moved A Movement

The March on Washington and King’s speech are widely considered turning points in the Civil Rights Movement, shifting the demand and demonstrations for racial equality that had mostly occurred in the South to a national stage.

Dorsey said the speech advanced and solidified the movement because “it became the perfect response to a turbulent moment as it tried to address past hurts, current indifference and potential violence, acting as a pivot point between the Kennedy administration’s slow response and the urgent response of the ‘marvelous new militancy’ [those fighting against racism].”

What made King such an outstanding orator were the communication skills he used to stir audience passion, Dorsey said. “When you watch the speech, halfway through he stops reading and becomes a pastor, urging his flock to do the right thing,” he said. “The cadence, power and call to the better nature of his audience reminds you of a religious service.”

Lessons For Today

Dorsey said the best leaders are those who can inspire all without dismissing some, and that King in his famous address did just that.

“He was not just speaking to African Americans in that speech, but to all Americans, because he understood that the country would more easily rise together when it worked together,” he said.

“I Have a Dream” remains relevant today “because for as many strides that have been made, we’re still dealing with the elements of a ‘bad check’ – voter suppression, instances of violence against people of color without real redress, etc.,” Dorsey said. “Remembering what King was trying to do then can provide us insight into what we need to consider now.”

Additionally, King understood that persuasion doesn’t move from A to Z in one fell swoop, but it moves methodically from A to B, B to C, etc., Dorsey said. “In the line ‘I have a dream that one day ,’ he recognized that things are not going to get better overnight, but such sentiment is needed to help people stay committed day-to-day until the country can honestly say, ‘free at last!'”

Media contact: Lesley Henton, 979-845-5591, [email protected].

Related Stories

MSC SCOLA Illuminates Path To Success

The three-day Student Conference on Latinx Affairs offers opportunities for learning, leadership and growth.

Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Heritage Month Events

A variety of campus organizations are inviting the Aggie community for unique cultural experiences.

MSC SCOLA 2023: ‘Focusing On The Present To Ensure Our Future’

The MSC Student Conference On Latinx Affairs (SCOLA) will challenge student leaders to focus on the influence of the Latinx community.

Recent Stories

Common Heartburn Medications May Help Fight Cancer And Other Immune Disorders In Dogs, Texas A&M Researchers Find

Study shows proton pump inhibitors could enhance effectiveness of chemotherapy.

Caring For Dogs With Special Needs

Special-needs dogs may require more work for the owner, but it can also be immensely fulfilling to help a dog in need.

Aggies Bring Creative Visions To Life At Starlab Motion Capture Facility

With professional-grade equipment and guidance from an industry veteran, Visualization students are using the technology from feature films like ‘Avatar’ to tell their own stories.

Subscribe to the Texas A&M Today newsletter for the latest news and stories every week.

Martin Luther King’s ‘Dream’ Speech: A defining Moment in American History

29 août 2013

Commentaire(s)

Partager cet article

Facebook X LinkedIn WhatsApp

Among the different personalities who combatted racial inequality in America, the name of Martin Luther King stands out. He was even entitled man of the year by Time magazine in 1963.

Tes Sorensen, President John F. Kennedy’s speechwriter said “ the right speech on the right topic delivered by the right speaker in the right way at the right moment can ignite a fire, change men’s mind , open their eyes, bring hope to their lives and in all these ways, change the world… .”

Remember Winston Churchill’s wartime speeches like “ we shall fight on the beaches, our finest hour …” that are appealing not only in contents but also couched in a flowery, metaphorical language that helped boost up the morale of the British army to the point that it was said of Churchill that he “ mobilized the English language and sent it to battle ”.

President Kennedy’s ‘World Peace’ address at the American university in June 1963 calling for a re-examination of “Americans’ own attitudes” at the height of the Cold war and shortly after the Cuban missile crisis, much to the surprise of the American people, eased the simmering tension and brought about a détente in the US/Soviet relationship.

But the early 60s also witnessed a ground-breaking event. Though Kennedy gave his tacit support to the Civil rights movement and Lyndon B. Johnson got the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act passed putting blacks and whites on the same pedestal as never before, it was Dr Martin Luther King’s historic - “I have a dream” - speech delivered on 28th August 1963, that American Historians claim was a defining moment in American history. King’s speech stirred America’s conscience that the time had arrived to change the centuries-old racist mindset engulfing the country and chart a new course where the US could justly be able to assume its leadership role of the “free world”.

King’s speech stands out as a soaring rhetoric bursting with metaphors and poetry. Analysts found it a well researched piece drawing references from Biblical passages and such documents as the Emancipation Proclamation, the US Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. The impact of the eloquence was so resounding that Time magazine went about to confer upon King the man of the year title in 1963. King outpaced in the title race a serious contender, John F. Kennedy, whose “World Peace” speech a bit earlier had a positive influence in that it calibrated the minds of angry Americans into accepting peace thus avoiding a possible, if not military, confrontation with Khrushchev’s Soviet Union, a gesture which led to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

That was followed in 1964 by the award to King of the Nobel Peace Prize at the young age of thirty-five, a distinction which even escaped the no less famous Mohandas Gandhi whose ideas of nonviolence King pulled into his own synthesis. Time also ranked some years ago the ‘dream’ speech in the ten best speeches ever delivered in world history.

On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, an impressive crowd of 250,000 people with a large number of whites gathered to listen to King’s passionate demands for ‘jobs and freedom’. Millions watched on television. The “March on Washington” as it became famously known was the culmination of black agitations and protests against abuses and discriminatory practices suffered by blacks. Despite the Emancipation Proclamation pronounced in 1863, King said the “ life of the Negro is still crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination ”.

Pressure for the introduction of civil rights legislation had a timid beginning in 1941 but started gathering momentum in the 50s following a series of incidents described as outrageous. Like for example, the Montgomery bus incident in 1955 when Rosa Parks, a black woman, was jailed for refusing to surrender on a bus her seat to a white man. The segregation law required that blacks were to be seated at the back and had to give up seat to a white who could not find one. There was the incident of the six year old black girl. A group of whites spat on her face because she wanted to go to the same school as white children. A 14 year old boy was hunted down and murdered because he dared make some remarks to a white woman. Blacks even with high education were debarred from voting. The segregation law was applied in all its harshness. “ Segregation yesterday, segregation now and segregation forever ”, proclaimed George Wallace, a state Governor.

In public places, the notice “Whites only” prominently displayed reminded blacks not to tread in reserved zones. The irony was that as a super power the US was teaching lessons of freedom and democracy to others when apartheid was raging in its own land. Civil rights’ activists led by Martin Luther King cried foul. Enough was enough.

The call for boycott of public transport by black Americans was massively followed and lasted for almost a year. Protest marches soon spread to several states and were met with police brutality until the US Supreme Court struck out the segregation law. That was already a triumphant outcome for King’s movement. Emboldened by this success, King and his civil rights activists conducted peaceful civil disobedience demonstrations. Even Kennedy endorsed King’s movement and decided to push forward the civil rights bill. Kennedy knew well that the bill would face a tough ride through Congress because of segregationists’ opposition and urged King to abandon his protest marches because these were “ill-timed”. “ We want success in Congress, not just a big show at the Capitol,” said the President to King.

“ Frankly, I have never been engaged in a direct action ”,retorted King, “that did not seem ill-timed...” Hisconvictions in his deeds andaction, his profound faith inthe goodness of men andhis belief in the great potentialof American democracycould hardly dampen hiszeal to fight for justice andequal rights for the American

people, whites or blacks. “ We are not satisfied and we will not be satisfied,” he said, “until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream”.

The historic “March on Washington” on 28th August 1963 claiming “Jobs and freedom” opened a new chapter in American history. With many Hollywood, music and literary celebrities mingling with the crowd, the mass rally at the Lincoln Memorial was designed as well to turn pressure on the Kennedy’s administration to expedite civil rights legislation. It was here in the speech delivered that King crafted his vision of a new America where blacks and whites were to enjoy equal rights. The “dream” speech has been hailed by Time as one of the ten greatest speeches ever delivered since the 4th century B.C when Socrates pleading his innocence in front of the Athenian judges ended his rhetoric with this line – “ the hour of departure has arrived, and we go our ways. I to die and you to live. What is better God only knows”. Likewise King’s speech was impregnated with emotion and lyrical cadence as he repeatedly used such refrains as –“ I have a dream ” (hope for a better future), “ Now is the time ” (for immediate action) and “ Let Freedom ring ” ( for equality and justice) so powerfully driven to stir the people’s moral conscience.

King started his speech by going back to the promises made ‘100 years ago’ through the “ magnificent words ” of the constitution and the Declaration of Independence that all men-black and white “ would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness ”. Nothing happened since then. That was like a promissory note, he said, thrown to the winds. Instead of fulfilling this sacred obligation, America has given “ the negro people a bad cheque, a cheque which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds’ .” He refused to believe that the American “ bank of justice has gone bankrupt’’ for the “ negro lives, one hundred years later, on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.” So he said “ now is the time ” to remind America that it had defaulted on this promissory note. There was a “ fierce urgency ”, he said for remedial action so that justice became a reality for “ all of God’s children ”. On a warning note, he said business was not going to be as usual henceforth for “ the whirlwind of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice merges”. “Now is the time”, he said , “to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice”. In so doing, the nation would be lifted from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. But he said the militancy of the black population should in no way lead to the distrust of the white people for “their destiny is tied up with our destiny…” King was about to wind up the speech when the singer Mahalia Jackson, a friend of King, standing nearby shouted at King “ Tell them about your dream, Martin, tell them about your dream”. From there, King pickedup the thread of his speech spontaneously. Departing from his prepared text, he started to dwell on the dream he held so dear, a dream “deeply rooted in the American dream” . The dream ‘sequence’ part was not to be found in the original text, it is said but as a skilled preacher used to delivering sermons, King carried on extemporaneously defining his dream studded with a string of hopes: “ One day, the sons offormer slaves and sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood”. “One day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.” “One day, my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judgedby the colour of their skin but by thecontent of their character”. “One day little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers”. America could only become a great nation, he said, if his dream was realised. King ended his speech with the ‘freedom refrain’ that blacks should be freed from the yoke of segregation. He wished he could hear the air of ‘freedom ringing’ from hilltops and mountains of America, from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city so that “ we will be able to speed that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘ Free at last! Free at last!’ ” But as King stated “ 1963 is not an end but a beginning ”. Rightly so for the speech aroused America’s moral conscience and much more after King’s assassination in 1968. A new era started creeping in. On the heels of that historic occasion followed a great leap with the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965) piloted by President Johnson. 50 years ago, it would not have occurred in the wildest dream of any American that of all things the country could have elected one day a black President. Barack Obama who will commemorate the ‘March on Washington’ at the Lincoln Memorial this Wednesday would not have become President of the US, political analysts argue, without the moral and political transformative leadership of Dr Martin Luther King.

Les plus récents

24 mai 2024 17:00

Collectif Arc-en-Ciel

Des mesures pour les droits des personnes transgenres à maurice.

24 mai 2024 16:30

Clap de fin en Bleu pour Giroud après l'Euro

24 mai 2024 16:06

Sooroojdev Phokeer : Un atout pour le MSM ?

24 mai 2024 16:00

«Metro leaks»

Les documents actuellement à l’étude.

24 mai 2024 15:00

«Chief Commercial Officer» de MK

Ziyaad parthasee remplace laurent recoura en pleine controverse.

24 mai 2024 14:00

Inondations à la rue Bissoondoyal

Une pétition pour exprimer la voix des habitants.

24 mai 2024 13:40

Coupe de France

Mbappé dans le groupe du psg pour la finale contre lyon.

24 mai 2024 13:00

Menaces d’une attaque à l’ambassade de France

Jaabir papauretty admis à brown-séquard car il dit entendre des voix.

24 mai 2024 12:38

Quatre morts dans l'effondrement d'un bar-restaurant aux Baléares

24 mai 2024 12:00

Budget supplémentaire de Rs 6,7 Mds

Débats prévus après le «budget day».

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

‘I Have a Dream’ Speech

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 19, 2023 | Original: November 30, 2017

The “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered by Martin Luther King, Jr. before a crowd of some 250,000 people at the 1963 March on Washington, remains one of the most famous speeches in history. Weaving in references to the country’s Founding Fathers and the Bible , King used universal themes to depict the struggles of African Americans before closing with an improvised riff on his dreams of equality. The eloquent speech was immediately recognized as a highlight of the successful protest, and has endured as one of the signature moments of the civil rights movement .

Civil Rights Movement Before the Speech

Martin Luther King Jr. , a young Baptist minister, rose to prominence in the 1950s as a spiritual leader of the burgeoning civil rights movement and president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SLCC).

By the early 1960s, African Americans had seen gains made through organized campaigns that placed its participants in harm’s way but also garnered attention for their plight. One such campaign, the 1961 Freedom Rides , resulted in vicious beatings for many participants, but resulted in the Interstate Commerce Commission ruling that ended the practice of segregation on buses and in stations.

Similarly, the Birmingham Campaign of 1963, designed to challenge the Alabama city’s segregationist policies, produced the searing images of demonstrators being beaten, attacked by dogs and blasted with high-powered water hoses.

Around the time he wrote his famed “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King decided to move forward with the idea for another event that coordinated with Negro American Labor Council (NACL) founder A. Philip Randolph’s plans for a job rights march.

March on Washington

Thanks to the efforts of veteran organizer Bayard Rustin, the logistics of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom came together by the summer of 1963.

Joining Randolph and King were the fellow heads of the “Big Six” civil rights organizations: Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Whitney Young of the National Urban League (NUL), James Farmer of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Other influential leaders also came aboard, including Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers (UAW) and Joachim Prinz of the American Jewish Congress (AJC).

Scheduled for August 28, the event was to consist of a mile-long march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, in honor of the president who had signed the Emancipation Proclamation a century earlier, and would feature a series of prominent speakers.

Its stated goals included demands for desegregated public accommodations and public schools, redress of violations of constitutional rights and an expansive federal works program to train employees.

The March on Washington produced a bigger turnout than expected, as an estimated 250,000 people arrived to participate in what was then the largest gathering for an event in the history of the nation’s capital.

Along with notable speeches by Randolph and Lewis, the audience was treated to performances by folk luminaries Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and gospel favorite Mahalia Jackson .

‘I Have a Dream’ Speech Origins

In preparation for his turn at the event, King solicited contributions from colleagues and incorporated successful elements from previous speeches. Although his “I have a dream” segment did not appear in his written text, it had been used to great effect before, most recently during a June 1963 speech to 150,000 supporters in Detroit.

Unlike his fellow speakers in Washington, King didn’t have the text ready for advance distribution by August 27. He didn’t even sit down to write the speech until after arriving at his hotel room later that evening, finishing up a draft after midnight.

‘Free At Last’

As the March on Washington drew to a close, television cameras beamed Martin Luther King’s image to a national audience. He began his speech slowly but soon showed his gift for weaving recognizable references to the Bible, the U.S. Constitution and other universal themes into his oratory.

Pointing out how the country’s founders had signed a “promissory note” that offered great freedom and opportunity, King noted that “Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.'”

At times warning of the potential for revolt, King nevertheless maintained a positive, uplifting tone, imploring the audience to “go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.”

Mahalia Jackson Prompts MLK: 'Tell 'em About the Dream, Martin'

Around the halfway point of the speech, Mahalia Jackson implored him to “Tell ’em about the ‘Dream,’ Martin.” Whether or not King consciously heard, he soon moved away from his prepared text.

Repeating the mantra, “I have a dream,” he offered up hope that “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” and the desire to “transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.”

“And when this happens,” he bellowed in his closing remarks, “and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!'”

‘I Have a Dream’ Speech Text

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we've come to our nation's Capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence , they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.

This note was a promise that all men, yes, Black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check; a check which has come back marked "insufficient funds."

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check—a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?"

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.

We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one.

We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating "for whites only."

We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, that one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exhalted [sic], every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I will go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning, "My country 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring."

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that; let freedom ring from the Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, Black men and white men, Jews and gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

MLK Speech Reception

King’s stirring speech was immediately singled out as the highlight of the successful march.

James Reston of The New York Times wrote that the “pilgrimage was merely a great spectacle” until King’s turn, and James Baldwin later described the impact of King’s words as making it seem that “we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real.”

Just three weeks after the march, King returned to the difficult realities of the struggle by eulogizing three of the girls killed in the bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

Still, his televised triumph at the feet of Lincoln brought favorable exposure to his movement, and eventually helped secure the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 . The following year, after the violent Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama, African Americans secured another victory with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 .

Over the final years of his life, King continued to spearhead campaigns for change even as he faced challenges by increasingly radical factions of the movement he helped popularize. Shortly after visiting Memphis, Tennessee, in support of striking sanitation workers, and just hours after delivering another celebrated speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” King was assassinated by shooter James Earl Ray on the balcony of his hotel room on April 4, 1968.

'I Have a Dream' Speech Legacy

Remembered for its powerful imagery and its repetition of a simple and memorable phrase, King’s “I Have a Dream” speech has endured as a signature moment of the civil rights struggle, and a crowning achievement of one of the movement’s most famous faces.

The Library of Congress added the speech to the National Recording Registry in 2002, and the following year the National Park Service dedicated an inscribed marble slab to mark the spot where King stood that day.

In 2016, Time included the speech as one of its 10 greatest orations in history.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

“I Have a Dream,” Address Delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute . March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. National Park Service . JFK, A. Philip Randolph and the March on Washington. The White House Historical Association . The Lasting Power of Dr. King’s Dream Speech. The New York Times .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Aug 28, 1963 ce: martin luther king jr. gives "i have a dream" speech.

On August 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington, a large gathering of civil rights protesters in Washington, D.C., United States.

Social Studies, Civics, U.S. History

Loading ...

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., took the podium at the March on Washington and addressed the gathered crowd, which numbered 200,000 people or more. His speech became famous for its recurring phrase “I have a dream.” He imagined a future in which “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners" could "sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” a future in which his four children are judged not "by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." King's moving speech became a central part of his legacy. King was born in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, in 1929. Like his father and grandfather, King studied theology and became a Baptist pastor . In 1957, he was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference ( SCLC ), which became a leading civil rights organization. Under King's leadership, the SCLC promoted nonviolent resistance to segregation, often in the form of marches and boycotts. In his campaign for racial equality, King gave hundreds of speeches, and was arrested more than 20 times. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 for his "nonviolent struggle for civil rights ." On April 4, 1968, King was shot and killed while standing on a balcony of his motel room in Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- HISTORY & CULTURE

Who was Martin Luther King, Jr.?

A civil rights legend, Dr. King fought for justice through peaceful protest—and delivered some of the 20th century's most iconic speeches.

The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., is a civil rights legend. In the mid-1950s, King led the movement to end segregation and counter prejudice in the United States through the means of peaceful protest. His speeches—some of the most iconic of the 20th century—had a profound effect on the national consciousness. Through his leadership, the civil rights movement opened doors to education and employment that had long been closed to Black America.

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a federal holiday to honor King for his commitment to equal rights and justice for all. Observed for the first time on January 20, 1986, it’s called Martin Luther King Jr. Day. In January 2000, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was officially observed in all 50 U.S. states . Here’s what you need to know about King’s extraordinary life.

Though King's name is known worldwide, many may not realize that he was born Michael King, Jr. in Atlanta, Georgia on January 15, 1929. His father , Michael King, was a pastor at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. During a trip to Germany, King, Sr. was so impressed by the history of Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther that he changed not only his own name, but also five-year-old Michael’s.

( Read about Martin Luther King, Jr. with your kids .)

His brilliance was noted early, as he was accepted into Morehouse College , a historically Black school in Atlanta, at age 15. By the summer before his last year of college, King knew he was destined to continue the family profession of pastoral work and decided to enter the ministry. He received his Bachelor’s degree from Morehouse at age 19, and then enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, graduating with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951. He earned a doctorate in systematic theology from Boston University in 1955.

King married Coretta Scott on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama. They became the parents of four children : Yolanda King (1955–2007), Martin Luther King III (b. 1957), Dexter Scott King (b. 1961), and Bernice King (b. 1963).

Becoming a civil rights leader

In 1954, when he was 25 years old, Dr. King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. In March 1955, Claudette Colvin—a 15-year-old Black schoolgirl in Montgomery—refused to give up her bus seat to a white man, which was a violation of Jim Crow laws, local laws in the southern United States that enforced racial segregation.

( Jim Crow laws created 'slavery by another name. ')

King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case. The local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) briefly considered using Colvin's case to challenge the segregation laws, but decided that because she was so young—and had become pregnant—her case would attract too much negative attention.

Nine months later on December 1, 1955, a similar incident occurred when a seamstress named Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus. The two incidents led to the Montgomery bus boycott , which was urged and planned by the President of the Alabama Chapter of the NAACP, E.D. Nixon, and led by King. The boycott lasted for 385 days.

King’s prominent and outspoken role in the boycott led to numerous threats against his life, and his house was firebombed. He was arrested during the campaign, which concluded with a United States District Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle ( in which Colvin was a plaintiff ) that ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses. King's role in the bus boycott transformed him into a national figure and the best-known spokesman of the civil rights movement.

Fighting for change through nonviolent protest

From the early days of the Montgomery boycott, King had often referred to India’s Mahatma Gandhi as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change.”

You May Also Like

The birth of the Holy Roman Empire—and the unlikely king who ruled it

How Martin Luther King, Jr.’s multifaceted view on human rights still inspires today

How Martin Luther Started a Religious Revolution

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Joseph Lowery, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to harness the organizing power of Black churches to conduct nonviolent protests to ultimately achieve civil rights reform. The group was part of what was called “The Big Five” of civil rights organizations, which included the NAACP, the National Urban League, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Congress on Racial Equality.

Through his connections with the Big Five civil rights groups, overwhelming support from Black America and with the support of prominent individual well-wishers, King’s skill and effectiveness grew exponentially. He organized and led marches for Blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.

( How the U.S. Voting Rights Act was won—and why it's under fire today .)

On August 28, 1963, The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom became the pinnacle of King’s national and international influence. Before a crowd of 250,000 people, he delivered the legendary “I Have A Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. That speech, along with many others that King delivered, has had a lasting influence on world rhetoric .

In 1964, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his civil rights and social justice activism. Most of the rights King organized protests around were successfully enacted into law with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act .

Economic justice and the Vietnam War

King’s opposition to the Vietnam War became a prominent part of his public persona. On April 4, 1967—exactly one year before his death—he gave a speech called “Beyond Vietnam” in New York City, in which he proposed a stop to the bombing of Vietnam. King also suggested that the United States declare a truce with the aim of achieving peace talks, and that the U.S. set a date for withdrawal.

( King's advocacy for human rights around the world still inspires today .)

Ultimately, King was driven to focus on social and economic justice in the United States. He had traveled to Memphis, Tennessee in early April 1968 to help organize a sanitation workers’ strike, and on the night of April 3, he delivered the legendary “I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech , in which he compared the strike to the long struggle for human freedom and the battle for economic justice, using the New Testament's Parable of the Good Samaritan to stress the need for people to get involved.

Assassination

But King would not live to realize that vision. The next day, April 4, 1968, King was gunned down on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis by James Earl Ray , a small-time criminal who had escaped the year before from a maximum-security prison. Ray was charged and convicted of the murder and sentenced to 99 years in prison on March 10, 1969. But Ray changed his mind after three days in jail, claiming he was not guilty and had been framed. He spent the rest of his life fighting unsuccessfully for a trial, despite the ultimate support of some members of the King family and the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

The turmoil that flowed from King’s assassination led many Black Americans to wonder if that dream he had spoken of so eloquently had died with him. But, today, young people around the world still learn about King's life and legacy—and his vision of equality and justice for all continue to resonate.

Related Topics

- CIVIL RIGHTS

Herod I: The controversial king who transformed the Holy Land

What was the Stonewall uprising?

Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

Meet the 5 iconic women being honored on new quarters in 2024

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Free Directory

- Arts & Entertainment

- Education & Professional

- Religion & Spirituality

- Self Development

- Social Sciences

- Sports & Hobbies

Free Audio Book

Get this free title from:

Free stuff in these categories, find more titles by.

Title Details

Learnoutloud.com review, people who liked martin luther king jr. discusses his i have a dream speech also liked these free titles:.

“I Have A Dream”: Annotated

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic speech, annotated with relevant scholarship on the literary, political, and religious roots of his words.

For this month’s Annotations, we’ve taken Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic “I Have A Dream” speech, and provided scholarly analysis of its groundings and inspirations—the speech’s religious, political, historical and cultural underpinnings are wide-ranging and have been read as jeremiad, call to action, and literature. While the speech itself has been used (and sometimes misused) to call for a “color-blind” country, its power is only increased by knowing its rhetorical and intellectual antecedents.