The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

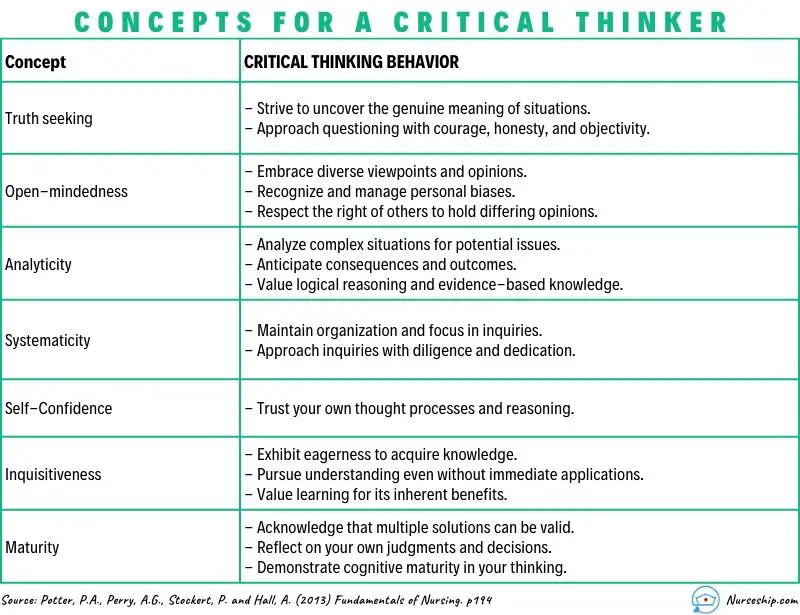

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter, DNP, APRN, ACNS-BC, CNE

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Critical thinking in nursing clinical practice, education and research: From attitudes to virtue

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Fundamental Care and Medical Surgital Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing, Consolidated Research Group Quantitative Psychology (2017-SGR-269), University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 2 Department of Fundamental Care and Medical Surgital Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing, Consolidated Research Group on Gender, Identity and Diversity (2017-SGR-1091), University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 3 Department of Fundamental Care and Medical Surgital Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 4 Multidisciplinary Nursing Research Group, Vall d'Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Vall d'Hebron Hospital, Barcelona, Spain.

- PMID: 33029860

- DOI: 10.1111/nup.12332

Critical thinking is a complex, dynamic process formed by attitudes and strategic skills, with the aim of achieving a specific goal or objective. The attitudes, including the critical thinking attitudes, constitute an important part of the idea of good care, of the good professional. It could be said that they become a virtue of the nursing profession. In this context, the ethics of virtue is a theoretical framework that becomes essential for analyse the critical thinking concept in nursing care and nursing science. Because the ethics of virtue consider how cultivating virtues are necessary to understand and justify the decisions and guide the actions. Based on selective analysis of the descriptive and empirical literature that addresses conceptual review of critical thinking, we conducted an analysis of this topic in the settings of clinical practice, training and research from the virtue ethical framework. Following JBI critical appraisal checklist for text and opinion papers, we argue the need for critical thinking as an essential element for true excellence in care and that it should be encouraged among professionals. The importance of developing critical thinking skills in education is well substantiated; however, greater efforts are required to implement educational strategies directed at developing critical thinking in students and professionals undergoing training, along with measures that demonstrate their success. Lastly, we show that critical thinking constitutes a fundamental component in the research process, and can improve research competencies in nursing. We conclude that future research and actions must go further in the search for new evidence and open new horizons, to ensure a positive effect on clinical practice, patient health, student education and the growth of nursing science.

Keywords: critical thinking; critical thinking attitudes; nurse education; nursing care; nursing research.

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Teaching strategies and outcome assessments targeting critical thinking in bachelor nursing students: a scoping review protocol. Westerdahl F, Carlson E, Wennick A, Borglin G. Westerdahl F, et al. BMJ Open. 2020 Feb 2;10(1):e033214. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033214. BMJ Open. 2020. PMID: 32014875 Free PMC article. Review.

- Health professionals' experience of teamwork education in acute hospital settings: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Eddy K, Jordan Z, Stephenson M. Eddy K, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016 Apr;14(4):96-137. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-1843. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016. PMID: 27532314 Review.

- Student and educator experiences of maternal-child simulation-based learning: a systematic review of qualitative evidence protocol. MacKinnon K, Marcellus L, Rivers J, Gordon C, Ryan M, Butcher D. MacKinnon K, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Jan;13(1):14-26. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1694. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015. PMID: 26447004

- Ethics in nursing education: learning to reflect on care practices. Vanlaere L, Gastmans C. Vanlaere L, et al. Nurs Ethics. 2007 Nov;14(6):758-66. doi: 10.1177/0969733007082116. Nurs Ethics. 2007. PMID: 17901186 Review.

- Strategies to overcome obstacles in the facilitation of critical thinking in nursing education. Mangena A, Chabeli MM. Mangena A, et al. Nurse Educ Today. 2005 May;25(4):291-8. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.01.012. Epub 2005 Apr 12. Nurse Educ Today. 2005. PMID: 15896414

- Higher Vocational Nursing Students' Clinical Core Competence in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Wang S, Huang S, Yan L. Wang S, et al. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024 Mar 1;10:23779608241233147. doi: 10.1177/23779608241233147. eCollection 2024 Jan-Dec. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024. PMID: 38435341 Free PMC article.

- Effect of the case-based learning method combined with virtual reality simulation technology on midwifery laboratory courses: A quasi-experimental study. Zhao L, Dai X, Chen S. Zhao L, et al. Int J Nurs Sci. 2023 Dec 16;11(1):76-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.12.009. eCollection 2024 Jan. Int J Nurs Sci. 2023. PMID: 38352279 Free PMC article.

- Translation, validation and psychometric properties of the Albanian version of the Nurses Professional Competence Scale Short form. Duka B, Stievano A, Caruso R, Prendi E, Ejupi V, Spada F, De Maria M, Rocco G, Notarnicola I. Duka B, et al. Acta Biomed. 2023 Aug 3;94(4):e2023197. doi: 10.23750/abm.v94i4.13575. Acta Biomed. 2023. PMID: 37539614 Free PMC article.

- A study of the effects of blended learning on university students' critical thinking: A systematic review. Haftador AM, Tehranineshat B, Keshtkaran Z, Mohebbi Z. Haftador AM, et al. J Educ Health Promot. 2023 Mar 31;12:95. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_665_22. eCollection 2023. J Educ Health Promot. 2023. PMID: 37288404 Free PMC article. Review.

- Multilevel Modeling of Individual and Group Level Influences on Critical Thinking and Clinical Decision-Making Skills among Registered Nurses: A Study Protocol. Zainal NH, Musa KI, Rasudin NS, Mamat Z. Zainal NH, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Apr 19;11(8):1169. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11081169. Healthcare (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37108003 Free PMC article.

- Alfaro-Lefevre, R. (2019). Critical thinking, clinical reasoning and clinical judgment. A practical approach, 7th ed. Elsevier.

- Armstrong, A. (2006). Towards a strong virtue ethics for nursing practice. Nursing Philosophy, 7(3), 110-124.

- Armstrong, A. (2007). Nursing ethics. A virtue-based approach. Palgrave Macmillian.

- Banks-Wallace, J., Despins, L., Adams-Leander, S., McBroom, L., & Tandy, L. (2008). Re/Affirming and re/conceptualizing disciplinary knowledge as the foundations for doctoral education. Advances in Nursing Sciencies, 31(1), 67-78. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ANS.0000311530.81188.88

- Banning, M. (2008). Clinical reasoning and its application to nursing: Concepts and research studies. Nurse Education in Practice, 8(3), 177-183.

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- PREI-19-007-B/School of Nursing. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Barcelona

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Critical Thinking in Nursing

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Şefika Dilek Güven 3

Part of the book series: Integrated Science ((IS,volume 12))

1169 Accesses

Critical thinking is an integral part of nursing, especially in terms of professionalization and independent clinical decision-making. It is necessary to think critically to provide adequate, creative, and effective nursing care when making the right decisions for practices and care in the clinical setting and solving various ethical issues encountered. Nurses should develop their critical thinking skills so that they can analyze the problems of the current century, keep up with new developments and changes, cope with nursing problems they encounter, identify more complex patient care needs, provide more systematic care, give the most appropriate patient care in line with the education they have received, and make clinical decisions. The present chapter briefly examines critical thinking, how it relates to nursing, and which skills nurses need to develop as critical thinkers.

Graphical Abstract/Art Performance

Critical thinking in nursing.

This painting shows a nurse and how she is thinking critically. On the right side are the stages of critical thinking and on the left side, there are challenges that a nurse might face. The entire background is also painted in several colors to represent a kind of intellectual puzzle. It is made using colored pencils and markers.

(Adapted with permission from the Association of Science and Art (ASA), Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN); Painting by Mahshad Naserpour).

Unless the individuals of a nation thinkers, the masses can be drawn in any direction. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Thinking Critically About the Quality of Critical Thinking Definitions and Measures

Criticality in Osteopathic Medicine: Exploring the Relationship between Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

Clinical Decision Making

Bilgiç Ş, Kurtuluş Tosun Z (2016) Birinci ve son sınıf hemşirelik öğrencilerinde eleştirel düşünme ve etkileyen faktörler. Sağlık Bilimleri ve Meslekleri Dergisi 3(1):39–47

Article Google Scholar

Kantek F, Yıldırım N (2019) The effects of nursing education on critical thinking of students: a meta-analysis. Florence Nightingale Hemşirelik Dergisi 27(1):17–25

Ennis R (1996) Critical thinking dispositions: their nature and assessability. Informal Logic 18(2):165–182

Riddell T (2007) Critical assumptions: thinking critically about critical thinking. J Nurs Educ 46(3):121–126

Cüceloğlu D (2001) İyi düşün doğru karar ver. Remzi Kitabevi, pp 242–284

Google Scholar

Kurnaz A (2019) Eleştirel düşünme öğretimi etkinlikleri Planlama-Uygulama ve Değerlendirme. Eğitim yayın evi, p 27

Doğanay A, Ünal F (2006) Eleştirel düşünmenin öğretimi. In: İçerik Türlerine Dayalı Öğretim. Ankara Nobel Yayınevi, pp 209–261

Scheffer B-K, Rubenfeld M-G (2000) A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing. J Nurs Educ 39(8):352–359

Article CAS Google Scholar

Rubenfeld M-G, Scheffer B (2014) Critical thinking tactics for nurses. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, pp 5–6, 7, 19–20

Gobet F (2005) Chunking models of expertise: implications for education. Appl Cogn Psychol 19:183–204

Ay F-A (2008) Mesleki temel kavramlar. In: Temel hemşirelik: Kavramlar, ilkeler, uygulamalar. İstanbul Medikal Yayıncılık, pp 205–220

Birol L (2010) Hemşirelik bakımında sistematik yaklaşım. In: Hemşirelik süreci. Berke Ofset Matbaacılık, pp 35–45

Twibell R, Ryan M, Hermiz M (2005) Faculty perceptions of critical thinking in student clinical experiences. J Nurs Educ 44(2):71–79

The Importance of Critical Thinking in Nursing. 19 November 2018 by Carson-Newman University Online. https://onlinenursing.cn.edu/news/value-critical-thinking-nursing

Suzanne C, Smeltzer Brenda G, Bare Janice L, Cheever HK (2010) Definition of critical thinking, critical thinking process. Medical surgical nursing. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, pp 27–28

Profetto-McGrath J (2003) The relationship of critical thinking skills and critical thinking dispositions of baccalaureate nursing students. J Adv Nurs 43(6):569–577

Elaine S, Mary C (2002) Critical thinking in nursing education: literature review. Int J Nurs Pract 8(2):89–98

Brunt B-A (2005) Critical thinking in nursing: an integrated review. J Continuing Educ Nurs 36(2):60–67

Carter L-M, Rukholm E (2008) A study of critical thinking, teacher–student interaction, and discipline-specific writing in an online educational setting for registered nurses. J Continuing Educ Nurs 39(3):133–138

Daly W-M (2001) The development of an alternative method in the assessment of critical thinking as an outcome of nursing education. J Adv Nurs 36(1):120–130

Edwards S-L (2007) Critical thinking: a two-phase framework. Nurse Educ Pract 7(5):303–314

Rogal S-M, Young J (2008) Exploring critical thinking in critical care nursing education: a pilot study. J Continuing Educ Nurs 39(1):28–33

Worrell J-A, Profetto-McGrath J (2007) Critical thinking as an outcome of context-based learning among post RN students: a literature review. Nurse Educ Today 27(5):420–426

Morrall P, Goodman B (2013) Critical thinking, nurse education and universities: some thoughts on current issues and implications for nursing practice. Nurse Educ Today 33(9):935–937

Raymond-Seniuk C, Profetto-McGrath J (2011) Can one learn to think critically?—a philosophical exploration. Open Nurs J 5:45–51

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli University, Semra ve Vefa Küçük, Faculty of Health Sciences, Nursing Department, 2000 Evler Mah. Damat İbrahim Paşa Yerleşkesi, Nevşehir, Turkey

Şefika Dilek Güven

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Şefika Dilek Güven .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Stockholm, Sweden

Nima Rezaei

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Güven, Ş.D. (2023). Critical Thinking in Nursing. In: Rezaei, N. (eds) Brain, Decision Making and Mental Health. Integrated Science, vol 12. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_10

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-15958-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-15959-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What is Problem-Solving in Nursing? (With Examples, Importance, & Tips to Improve)

Whether you have been a nurse for many years or you are just beginning your nursing career, chances are, you know that problem-solving skills are essential to your success. With all the skills you are expected to develop and hone as a nurse, you may wonder, “Exactly what is problem solving in nursing?” or “Why is it so important?” In this article, I will share some insight into problem-solving in nursing from my experience as a nurse. I will also tell you why I believe problem-solving skills are important and share some tips on how to improve your problem-solving skills.

What Exactly Is Problem-Solving In Nursing?

5 reasons why problem-solving is important in nursing, reason #1: good problem-solving skills reflect effective clinical judgement and critical thinking skills, reason #2: improved patient outcomes, reason #3: problem-solving skills are essential for interdisciplinary collaboration, reason #4: problem-solving skills help promote preventative care measures, reason #5: fosters opportunities for improvement, 5 steps to effective problem-solving in nursing, step #1: gather information (assessment), step #2: identify the problem (diagnosis), step #3: collaborate with your team (planning), step #4: putting your plan into action (implementation), step #5: decide if your plan was effective (evaluation), what are the most common examples of problem-solving in nursing, example #1: what to do when a medication error occurs, how to solve:, example #2: delegating tasks when shifts are short-staffed, example #3: resolving conflicts between team members, example #4: dealing with communication barriers/lack of communication, example #5: lack of essential supplies, example #6: prioritizing care to facilitate time management, example #7: preventing ethical dilemmas from hindering patient care, example #8: finding ways to reduce risks to patient safety, bonus 7 tips to improve your problem-solving skills in nursing, tip #1: enhance your clinical knowledge by becoming a lifelong learner, tip #2: practice effective communication, tip #3: encourage creative thinking and team participation, tip #4: be open-minded, tip #5: utilize your critical thinking skills, tip #6: use evidence-based practices to guide decision-making, tip #7: set a good example for other nurses to follow, my final thoughts, list of sources used for this article.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Margaret McCartney:...

Nurses are critical thinkers

Rapid response to:

Margaret McCartney: Nurses must be allowed to exercise professional judgment

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

The characteristic that distinguishes a professional nurse is cognitive rather than psychomotor ability. Nursing practice demands that practitioners display sound judgement and decision-making skills as critical thinking and clinical decision making is an essential component of nursing practice. Nurses’ ability to recognize and respond to signs of patient deterioration in a timely manner plays a pivotal role in patient outcomes (Purling & King 2012). Errors in clinical judgement and decision making are said to account for more than half of adverse clinical events (Tomlinson, 2015). The focus of the nurse clinical judgement has to be on quality evidence based care delivery, therefore, observational and reasoning skills will result in sound, reliable, clinical judgements. Clinical judgement, a concept which is critical to the nursing can be complex, because the nurse is required to use observation skills, identify relevant information, to identify the relationships among given elements through reasoning and judgement. Clinical reasoning is the process by which nurses observe patients status, process the information, come to an understanding of the patient problem, plan and implement interventions, evaluate outcomes, with reflection and learning from the process (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). At all times, nurses are responsible for their actions and are accountable for nursing judgment and action or inaction.

The speed and ability by which the nurses make sound clinical judgement is affected by their experience. Novice nurses may find this process difficult, whereas the experienced nurse should rely on her intuition, followed by fast action. Therefore education must begin at the undergraduate level to develop students’ critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills. Clinical reasoning is a learnt skill requiring determination and active engagement in deliberate practice design to improve performance. In order to acquire such skills, students need to develop critical thinking ability, as well as an understanding of how judgements and decisions are reached in complex healthcare environments.

As lifelong learners, nurses are constantly accumulating more knowledge, expertise, and experience, and it’s a rare nurse indeed who chooses to not apply his or her mind towards the goal of constant learning and professional growth. Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the Future of Nursing, stated, that nurses must continue their education and engage in lifelong learning to gain the needed competencies for practice. American Nurses Association (ANA), Scope and Standards of Practice requires a nurse to remain involved in continuous learning and strengthening individual practice (p.26)

Alfaro-LeFevre, R. (2009). Critical thinking and clinical judgement: A practical approach to outcome-focused thinking. (4th ed.). St Louis: Elsevier

The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health, (2010). https://campaignforaction.org/resource/future-nursing-iom-report

Levett-Jones, T., Hoffman, K. Dempsey, Y. Jeong, S., Noble, D., Norton, C., Roche, J., & Hickey, N. (2010). The ‘five rights’ of clinical reasoning: an educational model to enhance nursing students’ ability to identify and manage clinically ‘at risk’ patients. Nurse Education Today. 30(6), 515-520.

NMC (2010) New Standards for Pre-Registration Nursing. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council.

Purling A. & King L. (2012). A literature review: graduate nurses’ preparedness for recognising and responding to the deteriorating patient. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(23–24), 3451–3465

Thompson, C., Aitken, l., Doran, D., Dowing, D. (2013). An agenda for clinical decision making and judgement in nursing research and education. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50 (12), 1720 - 1726 Tomlinson, J. (2015). Using clinical supervision to improve the quality and safety of patient care: a response to Berwick and Francis. BMC Medical Education, 15(103)

Competing interests: No competing interests

ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

Problem Solving in Nursing: Strategies for Your Staff

4 min read • September, 15 2023

Problem solving is in a nurse manager’s DNA. As leaders, nurse managers solve problems every day on an individual level and with their teams. Effective leaders find innovative solutions to problems and encourage their staff to nurture their own critical thinking skills and see problems as opportunities rather than obstacles.

Health care constantly evolves, so problem solving and ingenuity are skills often used out of necessity. Tackling a problem requires considering multiple options to develop a solution. Problem solving in nursing requires a solid strategy.

Nurse problem solving

Nurse managers face challenges ranging from patient care matters to maintaining staff satisfaction. Encourage your staff to develop problem-solving nursing skills to cultivate new methods of improving patient care and to promote nurse-led innovation .

Critical thinking skills are fostered throughout a nurse’s education, training, and career. These skills help nurses make informed decisions based on facts, data, and evidence to determine the best solution to a problem.

Problem-Solving Examples in Nursing

To solve a problem, begin by identifying it. Then analyze the problem, formulate possible solutions, and determine the best course of action. Remind staff that nurses have been solving problems since Florence Nightingale invented the nurse call system.

Nurses can implement the original nursing process to guide patient care for problem solving in nursing. These steps include:

- Assessment . Use critical thinking skills to brainstorm and gather information.

- Diagnosis . Identify the problem and any triggers or obstacles.

- Planning . Collaborate to formulate the desired outcome based on proven methods and resources.

- Implementation . Carry out the actions identified to resolve the problem.

- Evaluation . Reflect on the results and determine if the issue was resolved.

How to Develop Problem-Solving Strategies

Staff look to nurse managers to solve a problem, even when there’s not always an obvious solution. Leaders focused on problem solving encourage their team to work collaboratively to find an answer. Core leadership skills are a good way to nurture a health care environment that supports sharing concerns and innovation .

Here are some essentials for building a culture of innovation that encourages problem solving:

- Present problems as opportunities instead of obstacles.

- Strive to be a positive role model. Support creative thinking and staff collaboration.

- Encourage feedback and embrace new ideas.

- Respect staff knowledge and abilities.

- Match competencies with specific needs and inspire effective decision-making.

- Offer opportunities for continual learning and career growth.

- Promote research and analysis opportunities.

- Provide support and necessary resources.

- Recognize contributions and reward efforts .

Embrace Innovation to Find Solutions

Try this exercise:

Consider an ongoing departmental issue and encourage everyone to participate in brainstorming a solution. The team will:

- Define the problem, including triggers or obstacles.

- Determine methods that worked in the past to resolve similar issues.

- Explore innovative solutions.

- Develop a plan to implement a solution and monitor and evaluate results.

Problems arise unexpectedly in the fast-paced health care environment. Nurses must be able to react using critical thinking and quick decision-making skills to implement practical solutions. By employing problem-solving strategies, nurse leaders and their staff can improve patient outcomes and refine their nursing skills.

Images sourced from Getty Images

Related Resources

Item(s) added to cart

- Who We Insure

- Insurance Products

- About Berxi

Topics on this page:

The importance of critical thinking in nursing.

Topics on this page

While not every decision is an immediate life-and-death situation, there are hundreds of decisions nurses must make every day that impact patient care in ways small and large.

“Being able to assess situations and make decisions can lead to life-or-death situations,” said nurse anesthetist Aisha Allen . “Critical thinking is a crucial and essential skill for nurses.”

The National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission (NLNAC) defines critical thinking in nursing this way: “the deliberate nonlinear process of collecting, interpreting, analyzing, drawing conclusions about, presenting, and evaluating information that is both factually and belief-based. This is demonstrated in nursing by clinical judgment, which includes ethical, diagnostic, and therapeutic dimensions and research.”

Why Critical Thinking in Nursing Is Important

An eight-year study by Johns Hopkins reports that 10% of deaths in the U.S. are due to medical error — the third-highest cause of death in the country.

“Diagnostic errors, medical mistakes, and the absence of safety nets could result in someone’s death,” wrote Dr. Martin Makary , professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Everyone makes mistakes — even doctors. Nurses applying critical thinking skills can help reduce errors.

“Question everything,” said pediatric nurse practitioner Ersilia Pompilio RN, MSN, PNP . “Especially doctor’s orders.” Nurses often spend more time with patients than doctors and may notice slight changes in conditions that may not be obvious. Resolving these observations with treatment plans can help lead to better care.

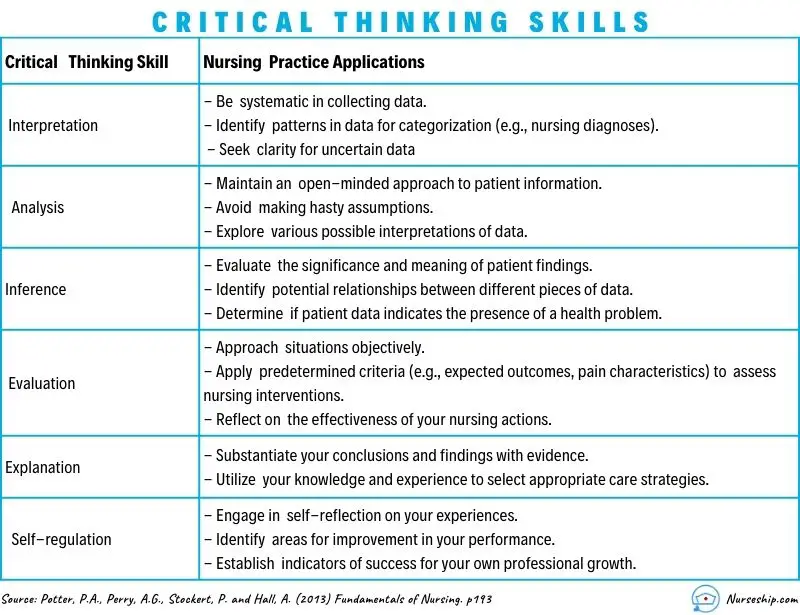

Key Nursing Critical Thinking Skills

Some of the most important critical thinking skills nurses use daily include interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation.

- Interpretation: Understanding the meaning of information or events.

- Analysis: Investigating a course of action based on objective and subjective data.

- Evaluation: Assessing the value of information and its credibility.

- Inference: Making logical deductions about the impact of care decisions.

- Explanation: Translating complicated and often complex medical information to patients and families in a way they can understand to make decisions about patient care.

- Self-Regulation: Avoiding the impact of unconscious bias with cognitive awareness.

These skills are used in conjunction with clinical reasoning. Based on training and experience, nurses use these skills and then have to make decisions affecting care.

It’s the ultimate test of a nurse’s ability to gather reliable data and solve complex problems. However, critical thinking goes beyond just solving problems. Critical thinking incorporates questioning and critiquing solutions to find the most effective one. For example, treating immediate symptoms may temporarily solve a problem, but determining the underlying cause of the symptoms is the key to effective long-term health.

8 Examples of Critical Thinking in Nursing

Here are some real-life examples of how nurses apply critical thinking on the job every day, as told by nurses themselves.

Example #1: Patient Assessments

“Doing a thorough assessment on your patient can help you detect that something is wrong, even if you're not quite sure what it is,” said Shantay Carter , registered nurse and co-founder of Women of Integrity . “When you notice the change, you have to use your critical thinking skills to decide what's the next step. Critical thinking allows you to provide the best and safest care possible.”

Example #2: First Line of Defense

Often, nurses are the first line of defense for patients.

“One example would be a patient that had an accelerated heart rate,” said nurse educator and adult critical care nurse Dr. Jenna Liphart Rhoads . “As a nurse, it was my job to investigate the cause of the heart rate and implement nursing actions to help decrease the heart rate prior to calling the primary care provider.”

Nurses with poor critical thinking skills may fail to detect a patient in stress or deteriorating condition. This can result in what’s called a “ failure to rescue ,” or FTR, which can lead to adverse conditions following a complication that leads to mortality.

Example #3: Patient Interactions

Nurses are the ones taking initial reports or discussing care with patients.

“We maintain relationships with patients between office visits,” said registered nurse, care coordinator, and ambulatory case manager Amelia Roberts . “So, when there is a concern, we are the first name that comes to mind (and get the call).”

“Several times, a parent called after the child had a high temperature, and the call came in after hours,” Roberts said. “Doing a nursing assessment over the phone is a special skill, yet based on the information gathered related to the child's behavior (and) fluid intake, there were several recommendations I could make.”

Deciding whether it was OK to wait until the morning, page the primary care doctor, or go to the emergency room to be evaluated takes critical thinking.

Example #4: Using Detective Skills

Nurses have to use acute listening skills to discern what patients are really telling them (or not telling them) and whether they are getting the whole story.

“I once had a 5-year-old patient who came in for asthma exacerbation on repeated occasions into my clinic,” said Pompilio. “The mother swore she was giving her child all her medications, but the asthma just kept getting worse.”

Pompilio asked the parent to keep a medication diary.

“It turned out that after a day or so of medication and alleviation in some symptoms, the mother thought the child was getting better and stopped all medications,” she said.

Example #5: Prioritizing

“Critical thinking is present in almost all aspects of nursing, even those that are not in direct action with the patient,” said Rhoads. “During report, nurses decide which patient to see first based on the information gathered, and from there they must prioritize their actions when in a patient’s room. Nurses must be able to scrutinize which medications can be taken together, and which modality would be best to help a patient move from the bed to the chair.”

A critical thinking skill in prioritization is cognitive stacking. Cognitive stacking helps create smooth workflow management to set priorities and help nurses manage their time. It helps establish routines for care while leaving room within schedules for the unplanned events that will inevitably occur. Even experienced nurses can struggle with juggling today’s significant workload, prioritizing responsibilities, and delegating appropriately.

Example #6: Medication & Care Coordination

Another aspect that often falls to nurses is care coordination. A nurse may be the first to notice that a patient is having an issue with medications.

“Based on a report of illness in a patient who has autoimmune challenges, we might recommend that a dose of medicine that interferes with immune response be held until we communicate with their specialty provider,” said Roberts.

Nurses applying critical skills can also help ease treatment concerns for patients.

“We might recommend a patient who gets infusions come in earlier in the day to get routine labs drawn before the infusion to minimize needle sticks and trauma,” Robert said.

Example #7: Critical Decisions

During the middle of an operation, the anesthesia breathing machine Allen was using malfunctioned.

“I had to critically think about whether or not I could fix this machine or abandon that mode of delivering nursing anesthesia care safely,” she said. “I chose to disconnect my patient from the malfunctioning machine and retrieve tools and medications to resume medication administration so that the surgery could go on.”

Nurses are also called on to do rapid assessments of patient conditions and make split-second decisions in the operating room.

“When blood pressure drops, it is my responsibility to decide which medication and how much medication will fix the issue,” Allen said. “I must work alongside the surgeons and the operating room team to determine the best plan of care for that patient's surgery.”

“On some days, it seems like you are in the movie ‘The Matrix,’” said Pompilio. “There's lots of chaos happening around you. Your patient might be decompensating. You have to literally stop time and take yourself out of the situation and make a decision.”

Example #8: Fast & Flexible Decisions

Allen said she thinks electronics are great, but she can remember a time when technology failed her.

“The hospital monitor that gives us vitals stopped correlating with real-time values,” she said. “So I had to rely on basic nursing skills to make sure my patient was safe. (Pulse check, visual assessments, etc.)”

In such cases, there may not be enough time to think through every possible outcome. Critical thinking combined with experience gives nurses the ability to think quickly and make the right decisions.

Improving the Quality of Patient Care

Nurses who think critically are in a position to significantly increase the quality of patient care and avoid adverse outcomes.

“Critical thinking allows you to ensure patient safety,” said Carter. “It’s essential to being a good nurse.”

Nurses must be able to recognize a change in a patient’s condition, conduct independent interventions, anticipate patients and provider needs, and prioritize. Such actions require critical thinking ability and advanced problem-solving skills.

“Nurses are the eyes and ears for patients, and critical thinking allows us to be their advocates,” said Allen.

Image courtesy of iStock.com/ davidf

Last updated on Jan 05, 2024 .

Originally published on Aug 25, 2021 .

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Berxi™ or Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance Company. This article (subject to change without notice) is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute professional advice. Click here to read our full disclaimer

Delegation in Nursing: Steps, Skills, & Solutions for Creating Balance at Work

The 7 Most Common Nursing Mistakes (And What You Can Do If You Make One)

Resource topics.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (Explained W/ Examples)

Last updated on August 23rd, 2023

Critical thinking is a foundational skill applicable across various domains, including education, problem-solving, decision-making, and professional fields such as science, business, healthcare, and more.

It plays a crucial role in promoting logical and rational thinking, fostering informed decision-making, and enabling individuals to navigate complex and rapidly changing environments.

In this article, we will look at what is critical thinking in nursing practice, its importance, and how it enables nurses to excel in their roles while also positively impacting patient outcomes.

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is a cognitive process that involves analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

It’s a mental activity that goes beyond simple memorization or acceptance of information at face value.

Critical thinking involves careful, reflective, and logical thinking to understand complex problems, consider various perspectives, and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions or solutions.

Key aspects of critical thinking include:

- Analysis: Critical thinking begins with the thorough examination of information, ideas, or situations. It involves breaking down complex concepts into smaller parts to better understand their components and relationships.

- Evaluation: Critical thinkers assess the quality and reliability of information or arguments. They weigh evidence, identify strengths and weaknesses, and determine the credibility of sources.

- Synthesis: Critical thinking involves combining different pieces of information or ideas to create a new understanding or perspective. This involves connecting the dots between various sources and integrating them into a coherent whole.

- Inference: Critical thinkers draw logical and well-supported conclusions based on the information and evidence available. They use reasoning to make educated guesses about situations where complete information might be lacking.

- Problem-Solving: Critical thinking is essential in solving complex problems. It allows individuals to identify and define problems, generate potential solutions, evaluate the pros and cons of each solution, and choose the most appropriate course of action.

- Creativity: Critical thinking involves thinking outside the box and considering alternative viewpoints or approaches. It encourages the exploration of new ideas and solutions beyond conventional thinking.

- Reflection: Critical thinkers engage in self-assessment and reflection on their thought processes. They consider their own biases, assumptions, and potential errors in reasoning, aiming to improve their thinking skills over time.

- Open-Mindedness: Critical thinkers approach ideas and information with an open mind, willing to consider different viewpoints and perspectives even if they challenge their own beliefs.

- Effective Communication: Critical thinkers can articulate their thoughts and reasoning clearly and persuasively to others. They can express complex ideas in a coherent and understandable manner.

- Continuous Learning: Critical thinking encourages a commitment to ongoing learning and intellectual growth. It involves seeking out new knowledge, refining thinking skills, and staying receptive to new information.

Definition of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an intellectual process of analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing is a vital cognitive skill that involves analyzing, evaluating, and making reasoned decisions about patient care.

It’s an essential aspect of a nurse’s professional practice as it enables them to provide safe and effective care to patients.

Critical thinking involves a careful and deliberate thought process to gather and assess information, consider alternative solutions, and make informed decisions based on evidence and sound judgment.

This skill helps nurses to:

- Assess Information: Critical thinking allows nurses to thoroughly assess patient information, including medical history, symptoms, and test results. By analyzing this data, nurses can identify patterns, discrepancies, and potential issues that may require further investigation.

- Diagnose: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data and collaboratively work with other healthcare professionals to formulate accurate nursing diagnoses. This is crucial for developing appropriate care plans that address the unique needs of each patient.

- Plan and Implement Care: Once a nursing diagnosis is established, critical thinking helps nurses develop effective care plans. They consider various interventions and treatment options, considering the patient’s preferences, medical history, and evidence-based practices.

- Evaluate Outcomes: After implementing interventions, critical thinking enables nurses to evaluate the outcomes of their actions. If the desired outcomes are not achieved, nurses can adapt their approach and make necessary changes to the care plan.

- Prioritize Care: In busy healthcare environments, nurses often face situations where they must prioritize patient care. Critical thinking helps them determine which patients require immediate attention and which interventions are most essential.

- Communicate Effectively: Critical thinking skills allow nurses to communicate clearly and confidently with patients, their families, and other members of the healthcare team. They can explain complex medical information and treatment plans in a way that is easily understood by all parties involved.

- Identify Problems: Nurses use critical thinking to identify potential complications or problems in a patient’s condition. This early recognition can lead to timely interventions and prevent further deterioration.

- Collaborate: Healthcare is a collaborative effort involving various professionals. Critical thinking enables nurses to actively participate in interdisciplinary discussions, share their insights, and contribute to holistic patient care.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Critical thinking helps nurses navigate ethical dilemmas that can arise in patient care. They can analyze different perspectives, consider ethical principles, and make morally sound decisions.

- Continual Learning: Critical thinking encourages nurses to seek out new knowledge, stay up-to-date with the latest research and medical advancements, and incorporate evidence-based practices into their care.

In summary, critical thinking is an integral skill for nurses, allowing them to provide high-quality, patient-centered care by analyzing information, making informed decisions, and adapting their approaches as needed.

It’s a dynamic process that enhances clinical reasoning , problem-solving, and overall patient outcomes.

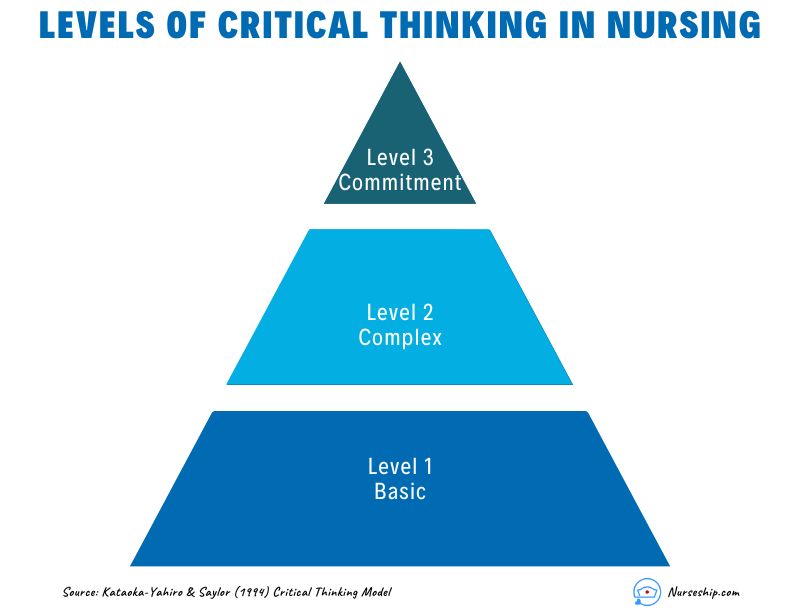

What are the Levels of Critical Thinking in Nursing?

The development of critical thinking in nursing practice involves progressing through three levels: basic, complex, and commitment.

The Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor model outlines this progression.

1. Basic Critical Thinking:

At this level, learners trust experts for solutions. Thinking is based on rules and principles. For instance, nursing students may strictly follow a procedure manual without personalization, as they lack experience. Answers are seen as right or wrong, and the opinions of experts are accepted.

2. Complex Critical Thinking:

Learners start to analyze choices independently and think creatively. They recognize conflicting solutions and weigh benefits and risks. Thinking becomes innovative, with a willingness to consider various approaches in complex situations.

3. Commitment:

At this level, individuals anticipate decision points without external help and take responsibility for their choices. They choose actions or beliefs based on available alternatives, considering consequences and accountability.

As nurses gain knowledge and experience, their critical thinking evolves from relying on experts to independent analysis and decision-making, ultimately leading to committed and accountable choices in patient care.

Why Critical Thinking is Important in Nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing for several crucial reasons:

Patient Safety:

Nursing decisions directly impact patient well-being. Critical thinking helps nurses identify potential risks, make informed choices, and prevent errors.

Clinical Judgment:

Nursing decisions often involve evaluating information from various sources, such as patient history, lab results, and medical literature.

Critical thinking assists nurses in critically appraising this information, distinguishing credible sources, and making rational judgments that align with evidence-based practices.

Enhances Decision-Making:

In nursing, critical thinking allows nurses to gather relevant patient information, assess it objectively, and weigh different options based on evidence and analysis.

This process empowers them to make informed decisions about patient care, treatment plans, and interventions, ultimately leading to better outcomes.

Promotes Problem-Solving:

Nurses encounter complex patient issues that require effective problem-solving.

Critical thinking equips them to break down problems into manageable parts, analyze root causes, and explore creative solutions that consider the unique needs of each patient.

Drives Creativity:

Nursing care is not always straightforward. Critical thinking encourages nurses to think creatively and explore innovative approaches to challenges, especially when standard protocols might not suffice for unique patient situations.

Fosters Effective Communication:

Communication is central to nursing. Critical thinking enables nurses to clearly express their thoughts, provide logical explanations for their decisions, and engage in meaningful dialogues with patients, families, and other healthcare professionals.

Aids Learning:

Nursing is a field of continuous learning. Critical thinking encourages nurses to engage in ongoing self-directed education, seeking out new knowledge, embracing new techniques, and staying current with the latest research and developments.

Improves Relationships:

Open-mindedness and empathy are essential in nursing relationships.

Critical thinking encourages nurses to consider diverse viewpoints, understand patients’ perspectives, and communicate compassionately, leading to stronger therapeutic relationships.

Empowers Independence:

Nursing often requires autonomous decision-making. Critical thinking empowers nurses to analyze situations independently, make judgments without undue influence, and take responsibility for their actions.

Facilitates Adaptability:

Healthcare environments are ever-changing. Critical thinking equips nurses with the ability to quickly assess new information, adjust care plans, and navigate unexpected situations while maintaining patient safety and well-being.

Strengthens Critical Analysis:

In the era of vast information, nurses must discern reliable data from misinformation.

Critical thinking helps them scrutinize sources, question assumptions, and make well-founded choices based on credible information.

How to Apply Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples)

Here are some examples of how nurses can apply critical thinking.

Assess Patient Data:

Critical Thinking Action: Carefully review patient history, symptoms, and test results.

Example: A nurse notices a change in a diabetic patient’s blood sugar levels. Instead of just administering insulin, the nurse considers recent dietary changes, activity levels, and possible medication interactions before adjusting the treatment plan.

Diagnose Patient Needs:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze patient data to identify potential nursing diagnoses.

Example: After reviewing a patient’s lab results, vital signs, and observations, a nurse identifies “ Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity ” due to the patient’s limited mobility.

Plan and Implement Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Develop a care plan based on patient needs and evidence-based practices.

Example: For a patient at risk of falls, the nurse plans interventions such as hourly rounding, non-slip footwear, and bed alarms to ensure patient safety.

Evaluate Interventions:

Critical Thinking Action: Assess the effectiveness of interventions and modify the care plan as needed.

Example: After administering pain medication, the nurse evaluates its impact on the patient’s comfort level and considers adjusting the dosage or trying an alternative pain management approach.

Prioritize Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Determine the order of interventions based on patient acuity and needs.

Example: In a busy emergency department, the nurse triages patients by considering the severity of their conditions, ensuring that critical cases receive immediate attention.

Collaborate with the Healthcare Team:

Critical Thinking Action: Participate in interdisciplinary discussions and share insights.

Example: During rounds, a nurse provides input on a patient’s response to treatment, which prompts the team to adjust the care plan for better outcomes.

Ethical Decision-Making:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze ethical dilemmas and make morally sound choices.

Example: When a terminally ill patient expresses a desire to stop treatment, the nurse engages in ethical discussions, respecting the patient’s autonomy and ensuring proper end-of-life care.

Patient Education:

Critical Thinking Action: Tailor patient education to individual needs and comprehension levels.

Example: A nurse uses visual aids and simplified language to explain medication administration to a patient with limited literacy skills.

Adapt to Changes:

Critical Thinking Action: Quickly adjust care plans when patient conditions change.

Example: During post-operative recovery, a nurse notices signs of infection and promptly informs the healthcare team to initiate appropriate treatment adjustments.

Critical Analysis of Information:

Critical Thinking Action: Evaluate information sources for reliability and relevance.

Example: When presented with conflicting research studies, a nurse critically examines the methodologies and sample sizes to determine which study is more credible.

Making Sense of Critical Thinking Skills

What is the purpose of critical thinking in nursing.

The purpose of critical thinking in nursing is to enable nurses to effectively analyze, interpret, and evaluate patient information, make informed clinical judgments, develop appropriate care plans, prioritize interventions, and adapt their approaches as needed, thereby ensuring safe, evidence-based, and patient-centered care.

Why critical thinking is important in nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing because it promotes safe decision-making, accurate clinical judgment, problem-solving, evidence-based practice, holistic patient care, ethical reasoning, collaboration, and adapting to dynamic healthcare environments.

Critical thinking skill also enhances patient safety, improves outcomes, and supports nurses’ professional growth.

How is critical thinking used in the nursing process?

Critical thinking is integral to the nursing process as it guides nurses through the systematic approach of assessing, diagnosing, planning, implementing, and evaluating patient care. It involves:

- Assessment: Critical thinking enables nurses to gather and interpret patient data accurately, recognizing relevant patterns and cues.

- Diagnosis: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data, identify nursing diagnoses, and differentiate actual issues from potential complications.

- Planning: Critical thinking helps nurses develop tailored care plans, selecting appropriate interventions based on patient needs and evidence.

- Implementation: Nurses make informed decisions during interventions, considering patient responses and adjusting plans as needed.

- Evaluation: Critical thinking supports the assessment of patient outcomes, determining the effectiveness of intervention, and adapting care accordingly.

Throughout the nursing process , critical thinking ensures comprehensive, patient-centered care and fosters continuous improvement in clinical judgment and decision-making.

What is an example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice?

An example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice could be:

A nurse is caring for a patient with a complex medical history who is experiencing a new set of symptoms. The nurse carefully reviews the patient’s history, recent test results, and medication list.

While discussing the case with the healthcare team, the nurse realizes that the current treatment plan might not be addressing all aspects of the patient’s condition.

Instead of simply following the established protocol, the nurse independently considers alternative approaches based on their assessment.

The nurse proposes a modification to the treatment plan, citing the rationale and evidence supporting the change.

This demonstrates independent thinking by critically evaluating the situation, challenging assumptions, and advocating for a more personalized and effective patient care approach.

How to use Costa’s level of questioning for critical thinking in nursing?

Costa’s levels of questioning can be applied in nursing to facilitate critical thinking and stimulate a deeper understanding of patient situations. The levels of questioning are as follows:

| Level 1: Gathering | 1. What are the common side effects of the prescribed medication? 2. When was the patient’s last bowel movement? 3. Who is the patient’s emergency contact person? 4. Describe the patient’s current level of pain. 5. What information is in the patient’s medical record? |

| 1. What would happen if the patient’s blood pressure falls further? 2. Compare the patient’s oxygen saturation levels before and after administering oxygen. 3. What other nursing interventions could be considered for wound care? 4. Infer the potential reasons behind the patient’s increased heart rate. 5. Analyze the relationship between the patient’s diet and blood glucose levels. | |

| 1. What do you think will be the patient’s response to the new pain management strategy? 2. Could the patient’s current symptoms be indicative of an underlying complication? 3. How would you prioritize care for patients with varying acuity levels in the emergency department? 4. What evidence supports your choice of administering the medication at this time? 5. Create a care plan for a patient with complex needs requiring multiple interventions. |

- 15 Attitudes of Critical Thinking in Nursing (Explained W/ Examples)

- Nursing Concept Map (FREE Template)

- Clinical Reasoning In Nursing (Explained W/ Example)

- 8 Stages Of The Clinical Reasoning Cycle

- How To Improve Critical Thinking Skills In Nursing? 24 Strategies With Examples

- What is the “5 Whys” Technique?

- What Are Socratic Questions?

Critical thinking in nursing is the foundation that underpins safe, effective, and patient-centered care.

Critical thinking skills empower nurses to navigate the complexities of their profession while consistently providing high-quality care to diverse patient populations.

Reading Recommendation

Potter, P.A., Perry, A.G., Stockert, P. and Hall, A. (2013) Fundamentals of Nursing

Comments are closed.

Medical & Legal Disclaimer

All the contents on this site are for entertainment, informational, educational, and example purposes ONLY. These contents are not intended to be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or practice guidelines. However, we aim to publish precise and current information. By using any content on this website, you agree never to hold us legally liable for damages, harm, loss, or misinformation. Read the privacy policy and terms and conditions.

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

© 2024 nurseship.com. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Healthcare (Basel)

- PMC10779280

Teaching Strategies for Developing Clinical Reasoning Skills in Nursing Students: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials

Associated data.

Data are contained within the article.

Background: Clinical reasoning (CR) is a holistic and recursive cognitive process. It allows nursing students to accurately perceive patients’ situations and choose the best course of action among the available alternatives. This study aimed to identify the randomised controlled trials studies in the literature that concern clinical reasoning in the context of nursing students. Methods: A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) was performed to identify relevant studies published up to October 2023. The following inclusion criteria were examined: (a) clinical reasoning, clinical judgment, and critical thinking in nursing students as a primary study aim; (b) articles published for the last eleven years; (c) research conducted between January 2012 and September 2023; (d) articles published only in English and Spanish; and (e) Randomised Clinical Trials. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool was utilised to appraise all included studies. Results: Fifteen papers were analysed. Based on the teaching strategies used in the articles, two groups have been identified: simulation methods and learning programs. The studies focus on comparing different teaching methodologies. Conclusions: This systematic review has detected different approaches to help nursing students improve their reasoning and decision-making skills. The use of mobile apps, digital simulations, and learning games has a positive impact on the clinical reasoning abilities of nursing students and their motivation. Incorporating new technologies into problem-solving-based learning and decision-making can also enhance nursing students’ reasoning skills. Nursing schools should evaluate their current methods and consider integrating or modifying new technologies and methodologies that can help enhance students’ learning and improve their clinical reasoning and cognitive skills.

1. Introduction

Clinical reasoning (CR) is a holistic cognitive process. It allows nursing students to accurately perceive patients’ situations and choose the best course of action among the available alternatives. This process is consistent, dynamic, and flexible, and it helps nursing students gain awareness and put their learning into perspective [ 1 ]. CR is an essential competence for nurses’ professional practice. It is considered crucial that its development begin during basic training [ 2 ]. Analysing clinical data, determining priorities, developing plans, and interpreting results are primary skills in clinical reasoning during clinical nursing practise [ 3 ]. To develop these skills, nursing students must participate in caring for patients and working in teams during clinical experiences. Among clinical reasoning skills, we can identify communication skills as necessary for connecting with patients, conducting health interviews, engaging in shared decision-making, eliciting patients’ concerns and expectations, discussing clinical cases with colleagues and supervisors, and explaining one’s reasoning to others [ 4 ].

Educating students in nursing practise to ensure high-quality learning and safe clinical practise is a constant challenge [ 5 ]. Facilitating the development of reasoning is challenging for educators due to its complexity and multifaceted nature [ 6 ], but it is necessary because clinical reasoning must be embedded throughout the nursing curriculum [ 7 ]. Such being the case, the development of clinical reasoning is encouraged, aiming to promote better performance in indispensable skills, decision-making, quality, and safety when assisting patients [ 8 ].

Nursing education is targeted at recognising clinical signs and symptoms, accurately assessing the patient, appropriately intervening, and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions. All these clinical processes require clinical reasoning, and it takes time to develop [ 9 ]. This is a significant goal of nursing education [ 10 ] in contemporary teaching and learning approaches [ 6 ].

Strategies to mitigate errors, promote knowledge acquisition, and develop clinical reasoning should be adopted in the training of health professionals. According to the literature, different methods and teaching strategies can be applied during nursing training, as well as traditional teaching through lectures. However, the literature explains that this type of methodology cannot enhance students’ clinical reasoning alone. Therefore, nursing educators are tasked with looking for other methodologies that improve students’ clinical reasoning [ 11 ], such as clinical simulation. Clinical simulation offers a secure and controlled setting to encounter and contemplate clinical scenarios, establish relationships, gather information, and exercise autonomy in decision-making and problem-solving [ 12 ]. Different teaching strategies have been developed in clinical simulation, like games or case studies. Research indicates a positive correlation between the use of simulation to improve learning outcomes and how it positively influences the development of students’ clinical reasoning skills [ 13 ].

The students of the 21st century utilise information and communication technologies. With their technological skills, organisations can enhance their productivity and achieve their goals more efficiently. Serious games are simulations that use technology to provide nursing students with a safe and realistic environment to practise clinical reasoning and decision-making skills [ 14 ] and can foster the development of clinical reasoning through an engaging and motivating experience [ 15 ].