Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing in the Social Sciences

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

In this section

Subsections.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Table of Contents

Research Report

Definition:

Research Report is a written document that presents the results of a research project or study, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions, in a clear and objective manner.

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of the research to the intended audience, which could be other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public.

Components of Research Report

Components of Research Report are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for the research report and provides a brief overview of the research question or problem being investigated. It should include a clear statement of the purpose of the study and its significance or relevance to the field of research. It may also provide background information or a literature review to help contextualize the research.

Literature Review

The literature review provides a critical analysis and synthesis of the existing research and scholarship relevant to the research question or problem. It should identify the gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the literature and show how the current study addresses these issues. The literature review also establishes the theoretical framework or conceptual model that guides the research.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. It should include information on the sample or participants, data collection instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. The methodology should be clear and detailed enough to allow other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and objective manner. It should provide a detailed description of the data and statistics used to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. Tables, graphs, and figures may be included to help visualize the data and illustrate the key findings.

The discussion section interprets the results of the study and explains their significance or relevance to the research question or problem. It should also compare the current findings with those of previous studies and identify the implications for future research or practice. The discussion should be based on the results presented in the previous section and should avoid speculation or unfounded conclusions.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings of the study and restates the main argument or thesis presented in the introduction. It should also provide a brief overview of the contributions of the study to the field of research and the implications for practice or policy.

The references section lists all the sources cited in the research report, following a specific citation style, such as APA or MLA.

The appendices section includes any additional material, such as data tables, figures, or instruments used in the study, that could not be included in the main text due to space limitations.

Types of Research Report

Types of Research Report are as follows:

Thesis is a type of research report. A thesis is a long-form research document that presents the findings and conclusions of an original research study conducted by a student as part of a graduate or postgraduate program. It is typically written by a student pursuing a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctoral degree, although it can also be written by researchers or scholars in other fields.

Research Paper

Research paper is a type of research report. A research paper is a document that presents the results of a research study or investigation. Research papers can be written in a variety of fields, including science, social science, humanities, and business. They typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Technical Report

A technical report is a detailed report that provides information about a specific technical or scientific problem or project. Technical reports are often used in engineering, science, and other technical fields to document research and development work.

Progress Report

A progress report provides an update on the progress of a research project or program over a specific period of time. Progress reports are typically used to communicate the status of a project to stakeholders, funders, or project managers.

Feasibility Report

A feasibility report assesses the feasibility of a proposed project or plan, providing an analysis of the potential risks, benefits, and costs associated with the project. Feasibility reports are often used in business, engineering, and other fields to determine the viability of a project before it is undertaken.

Field Report

A field report documents observations and findings from fieldwork, which is research conducted in the natural environment or setting. Field reports are often used in anthropology, ecology, and other social and natural sciences.

Experimental Report

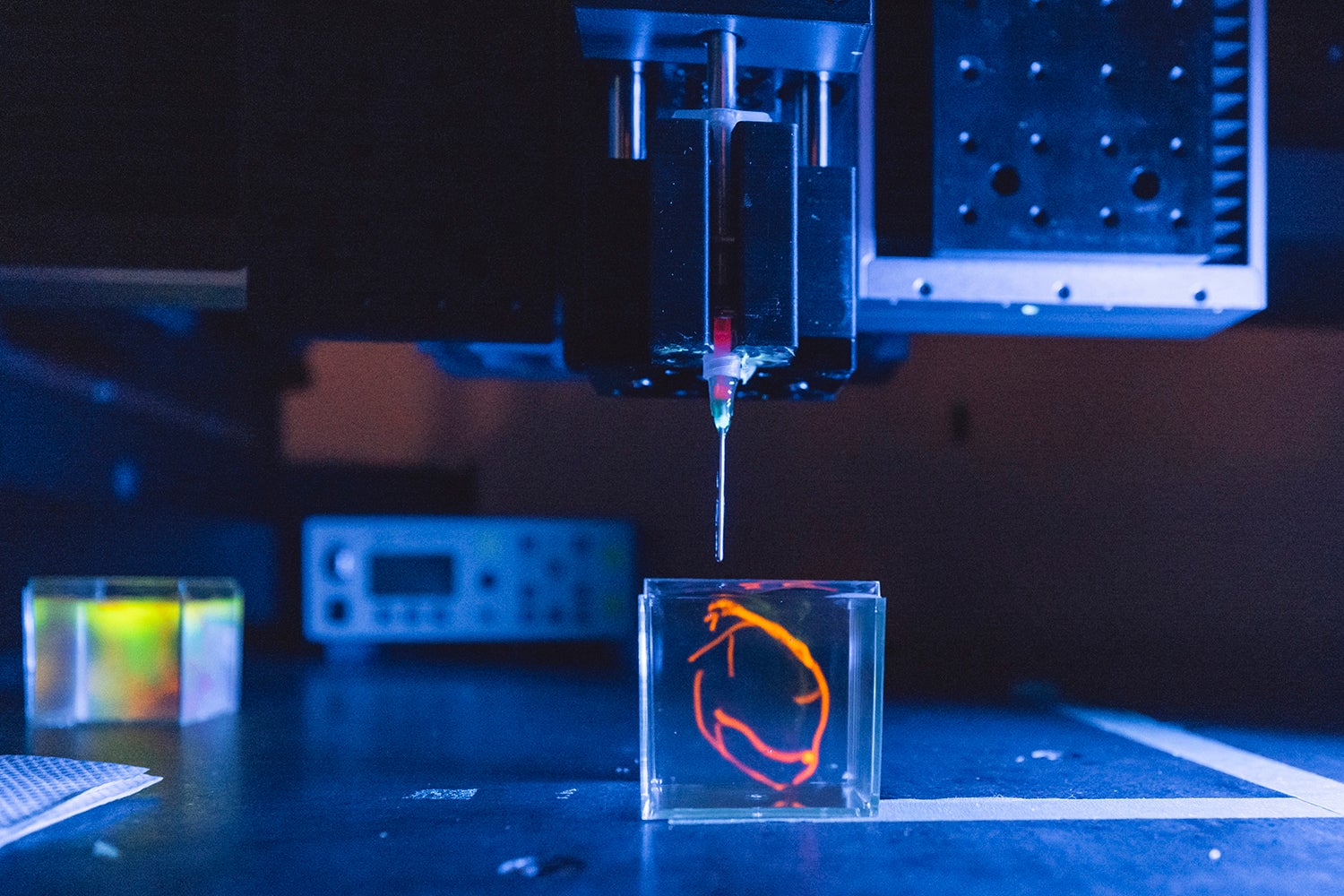

An experimental report documents the results of a scientific experiment, including the hypothesis, methods, results, and conclusions. Experimental reports are often used in biology, chemistry, and other sciences to communicate the results of laboratory experiments.

Case Study Report

A case study report provides an in-depth analysis of a specific case or situation, often used in psychology, social work, and other fields to document and understand complex cases or phenomena.

Literature Review Report

A literature review report synthesizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on the subject. Literature review reports are often used in social sciences, education, and other fields to identify gaps in the literature and guide future research.

Research Report Example

Following is a Research Report Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Academic Performance among High School Students

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students. The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The findings indicate that there is a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students. The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers, as they highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities.

Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of the lives of high school students. With the widespread use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, students can connect with friends, share photos and videos, and engage in discussions on a range of topics. While social media offers many benefits, concerns have been raised about its impact on academic performance. Many studies have found a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance among high school students (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010; Paul, Baker, & Cochran, 2012).

Given the growing importance of social media in the lives of high school students, it is important to investigate its impact on academic performance. This study aims to address this gap by examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students.

Methodology:

The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and was designed to measure the frequency and duration of social media use, as well as academic performance.

The participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique, and the survey questionnaire was distributed in the classroom during regular school hours. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

The findings indicate that the majority of high school students use social media platforms on a daily basis, with Facebook being the most popular platform. The results also show a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students.

Discussion:

The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. The negative correlation between social media use and academic performance suggests that strategies should be put in place to help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. For example, educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of the negative impact of social media on academic performance among high school students. The findings highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which social media use affects academic performance and to develop effective strategies for addressing this issue.

Limitations:

One limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should use random sampling techniques to increase the representativeness of the sample. Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social media use and academic performance, such as tracking software and school records.

Implications:

The findings of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. For example, teachers could use social media platforms to share relevant educational resources and facilitate online discussions. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. They could also engage in open communication with their children to understand their social media use and its impact on their academic performance. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students. For example, schools could implement social media policies that restrict access during class time and encourage responsible use.

References:

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook® and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237-1245.

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology, 8(1), 1-19.

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(10), 652-657.

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958.

Note*: Above mention, Example is just a sample for the students’ guide. Do not directly copy and paste as your College or University assignment. Kindly do some research and Write your own.

Applications of Research Report

Research reports have many applications, including:

- Communicating research findings: The primary application of a research report is to communicate the results of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public. The report serves as a way to share new knowledge, insights, and discoveries with others in the field.

- Informing policy and practice : Research reports can inform policy and practice by providing evidence-based recommendations for decision-makers. For example, a research report on the effectiveness of a new drug could inform regulatory agencies in their decision-making process.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research in a particular area. Other researchers may use the findings and methodology of a report to develop new research questions or to build on existing research.

- Evaluating programs and interventions : Research reports can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions in achieving their intended outcomes. For example, a research report on a new educational program could provide evidence of its impact on student performance.

- Demonstrating impact : Research reports can be used to demonstrate the impact of research funding or to evaluate the success of research projects. By presenting the findings and outcomes of a study, research reports can show the value of research to funders and stakeholders.

- Enhancing professional development : Research reports can be used to enhance professional development by providing a source of information and learning for researchers and practitioners in a particular field. For example, a research report on a new teaching methodology could provide insights and ideas for educators to incorporate into their own practice.

How to write Research Report

Here are some steps you can follow to write a research report:

- Identify the research question: The first step in writing a research report is to identify your research question. This will help you focus your research and organize your findings.

- Conduct research : Once you have identified your research question, you will need to conduct research to gather relevant data and information. This can involve conducting experiments, reviewing literature, or analyzing data.

- Organize your findings: Once you have gathered all of your data, you will need to organize your findings in a way that is clear and understandable. This can involve creating tables, graphs, or charts to illustrate your results.

- Write the report: Once you have organized your findings, you can begin writing the report. Start with an introduction that provides background information and explains the purpose of your research. Next, provide a detailed description of your research methods and findings. Finally, summarize your results and draw conclusions based on your findings.

- Proofread and edit: After you have written your report, be sure to proofread and edit it carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, and make sure that your report is well-organized and easy to read.

- Include a reference list: Be sure to include a list of references that you used in your research. This will give credit to your sources and allow readers to further explore the topic if they choose.

- Format your report: Finally, format your report according to the guidelines provided by your instructor or organization. This may include formatting requirements for headings, margins, fonts, and spacing.

Purpose of Research Report

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the results of a research study to a specific audience, such as peers in the same field, stakeholders, or the general public. The report provides a detailed description of the research methods, findings, and conclusions.

Some common purposes of a research report include:

- Sharing knowledge: A research report allows researchers to share their findings and knowledge with others in their field. This helps to advance the field and improve the understanding of a particular topic.

- Identifying trends: A research report can identify trends and patterns in data, which can help guide future research and inform decision-making.

- Addressing problems: A research report can provide insights into problems or issues and suggest solutions or recommendations for addressing them.

- Evaluating programs or interventions : A research report can evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions, which can inform decision-making about whether to continue, modify, or discontinue them.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies.

When to Write Research Report

A research report should be written after completing the research study. This includes collecting data, analyzing the results, and drawing conclusions based on the findings. Once the research is complete, the report should be written in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

In academic settings, research reports are often required as part of coursework or as part of a thesis or dissertation. In this case, the report should be written according to the guidelines provided by the instructor or institution.

In other settings, such as in industry or government, research reports may be required to inform decision-making or to comply with regulatory requirements. In these cases, the report should be written as soon as possible after the research is completed in order to inform decision-making in a timely manner.

Overall, the timing of when to write a research report depends on the purpose of the research, the expectations of the audience, and any regulatory requirements that need to be met. However, it is important to complete the report in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

Characteristics of Research Report

There are several characteristics of a research report that distinguish it from other types of writing. These characteristics include:

- Objective: A research report should be written in an objective and unbiased manner. It should present the facts and findings of the research study without any personal opinions or biases.

- Systematic: A research report should be written in a systematic manner. It should follow a clear and logical structure, and the information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand and follow.

- Detailed: A research report should be detailed and comprehensive. It should provide a thorough description of the research methods, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research report should be accurate and based on sound research methods. The findings and conclusions should be supported by data and evidence.

- Organized: A research report should be well-organized. It should include headings and subheadings to help the reader navigate the report and understand the main points.

- Clear and concise: A research report should be written in clear and concise language. The information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand, and unnecessary jargon should be avoided.

- Citations and references: A research report should include citations and references to support the findings and conclusions. This helps to give credit to other researchers and to provide readers with the opportunity to further explore the topic.

Advantages of Research Report

Research reports have several advantages, including:

- Communicating research findings: Research reports allow researchers to communicate their findings to a wider audience, including other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public. This helps to disseminate knowledge and advance the understanding of a particular topic.

- Providing evidence for decision-making : Research reports can provide evidence to inform decision-making, such as in the case of policy-making, program planning, or product development. The findings and conclusions can help guide decisions and improve outcomes.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research on a particular topic. Other researchers can build on the findings and conclusions of the report, which can lead to further discoveries and advancements in the field.

- Demonstrating expertise: Research reports can demonstrate the expertise of the researchers and their ability to conduct rigorous and high-quality research. This can be important for securing funding, promotions, and other professional opportunities.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies. Producing a high-quality research report can help ensure compliance with these requirements.

Limitations of Research Report

Despite their advantages, research reports also have some limitations, including:

- Time-consuming: Conducting research and writing a report can be a time-consuming process, particularly for large-scale studies. This can limit the frequency and speed of producing research reports.

- Expensive: Conducting research and producing a report can be expensive, particularly for studies that require specialized equipment, personnel, or data. This can limit the scope and feasibility of some research studies.

- Limited generalizability: Research studies often focus on a specific population or context, which can limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or contexts.

- Potential bias : Researchers may have biases or conflicts of interest that can influence the findings and conclusions of the research study. Additionally, participants may also have biases or may not be representative of the larger population, which can limit the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Accessibility: Research reports may be written in technical or academic language, which can limit their accessibility to a wider audience. Additionally, some research may be behind paywalls or require specialized access, which can limit the ability of others to read and use the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Clear and Precise

The clarity and precision of writing in the social sciences is paramount. Clarity refers to a variety of elements of your writing. First and foremost, you want to provide empirical evidence and/or citations for every claim that you make. Writing in the social sciences is not opinion based; you cannot say “Crime is decreasing across America” without providing empirical evidence for this claim, whether it is from a primary or secondary source. Furthermore, you want to be precise with your claims and language. If poverty is rising for women under 30, make sure to include this demographic information in a precise fashion. Additionally, do not use synonyms when they do not have the same meaning—use the specific terminology for the topic.

Writing in the social sciences also relies on paraphrasing more than direct quotations. Whenever possible, paraphrase or summarize your sources. You should only use a direct quotation if the exact words are crucial to your line of reasoning and argument. Remember that paraphrasing does not involve merely shifting words or finding synonyms. You need to take the material and rephrase it in your own words. A helpful tip for doing so is to read the information and then put it out of sight. From there, write about what you engaged with in your own words without looking at the original source text. When you are finished, you can compare the two for accuracy. Remember, too, that a paraphrase needs a citation even though it uses different language than the source. You are drawing upon the work of someone else.

Regarding precision, writing in the social sciences is not creative writing. Avoid flowery, emotional language; cut excess adjectives and adverbs. Platitudes such as “This came to light” or “It is general knowledge that…” should not be used.

Well-Organized

Organization is highly valued within the social sciences. While your organizational structure will vary with the genre of your writing assignment, there are general rules you will want to follow when organizing your writing assignments. The first key is to lay-out your organizational structure in your introduction and then follow that organizational structure within your text. If you mention that you will address a , b , and c , you need to address a , b , and c in that order.

There are some other general patterns to follow. You should have a clear and direct thesis statement in your introduction. Afterward, you need to present your evidence, summarizing and reviewing your research. In the body of your text, avoid moving from one topic to another. Stay with each topic until you have developed it thoroughly and sufficiently. Once your evidence has been addressed, you want to conclude your text with a strong, solid statement—the takeaway for your readers. When dealing with a research assignment, the conclusion often addresses areas for future research, yet the manner in which you approach the conclusion will vary from assignment to assignment.

Within the Scope of the Project

Narrowing a topic so that it is manageable within the scope of the project is essential. If not, the text can either fail to address key issues of the topic (if the topic is too broad) or the text will not have enough depth for the scope of the project (if the topic is too narrow). Due to the extensive scholarship available on most topics, it is usually better to narrow your topic.

One of the best ways to accomplish this is to narrow by geographic region and certain demographics (age, ethnicity, education-level, etc.) or other specific information like type(s) of crime, type(s) of punishment, or program (especially in criminal justice). Another effective method is to narrow toward the focus of the course by reviewing the syllabus and learning outcomes for the course. Using a variety of search terms will allow you to see the sources available on your topic.

Thorough and Logical Analysis

Strong analysis is vital to writing in the social sciences. The core of a strong analysis is in breaking down a topic into its major components and then exploring those components in-depth. Overall, a social scientist conducting an analysis wishes to break a topic into its major components in order to analyze them to form larger conclusions about the whole.

Although the method for analysis can vary according to the particular discipline and project, in general, you will want to start by identifying the issue. From there, you will want to inform the reader about the main facets of the issue and then move into a review of the research. Once you have reviewed the research, you can then form conclusions predicated on the research. Provide your readers with the main takeaways that an analysis of the research offers.

Pro Tips: Constructing a Literature Review

Literature reviews are a common genre in the social sciences. Here are some expert tips for how you can handle a literature review.

- Do not approach a literature review as an annotated bibliography. An annotated bibliography provides the APA or ASA reference and a short description of the source. A literature review delves more deeply into the sources and places them in conversation with one another. Annotations discuss sources in a separate fashion; literature reviews discuss sources in relation to one another.

- Compare and contrast the articles in a literature review. Place them in conversation with one another.

- Remain balanced. Focus on demonstrating knowledge about, and a comprehensive understanding of, the topic.

- When applicable, use the literature review to identify a research question (or questions) that needs to be answered. The literature review adds to the body of knowledge in the field and serves to establish the need for future research by demonstrating a gap or highlighting critical issues within the topic.

Pro Tips: Finding and Integrating Sources

Finding credible, impactful sources does not need to be challenging. Use these expert tips to help find the best sources and weave them into your research.

- Use scholarly sources primarily. Sources outside of academia should only be used as support for the primary sources.

- In general, a scholarly source is something that was written by an expert in a field or discipline, undergoes some level of peer or editorial review, and provides citations for all sources used.

- Substantive, reputable news sources (e.g. The Atlantic , The Boston Globe , The Washington Post , USA Today , etc.) can be used in the social sciences as well, yet they should not take the place of peer-reviewed sources.

- Draw information from websites that end in .gov or .org when possible. However, make sure to investigate the site—.gov and .org sites are not reliable 100% of the time. Some of these organizations exist to promote research for the purpose of selling us a product or service or promoting a political ideology or political agenda.

- Do not cite Twitter, Facebook, Wikipedia, etc.

- Remember to cite, especially when you paraphrase. If the idea is not your own, it needs to be cited even if you placed it in your own words.

- Cite every major claim. Do not make a claim without providing evidence for it. Where possible, go to the original source. Try to avoid citing indirect information.

- Contact the University Library if you are struggling to find sources—they are here to help!

Helpful Resources

Purdue OWL APA American Political Science Association Website Introduction to Scholarly Sources Advice for Writing a Literature Review Academic Phrase Bank

Need help with an assignment? Click here to make an appointment with a tutor

- The Lookout

- Military History Symposium

- Writing in Liberal Studies

- Writing in Social Work

Special preparations for April 8

A&M–Central Texas is making special preparations for April 8.

Students : Please note that the university is not holding any campus-wide events or on-campus classes on Monday, April 8, even though the campus will technically remain open for required services. Classes are not canceled, but they will be conducted as remote sessions unless otherwise stated by course faculty. Faculty will provide information on course requirements and assignments. Security/UPD and facilities services will be on campus that date.

All visitors : Most university employees will be working remotely with very limited on-campus availability. Please call ahead to confirm in-person campus appointments. The University Library and Archives will be closed, but reference librarians will be monitoring online chat requests.

Find more information on faculty, staff and class availability on Monday .

Updated: 7:35 am April 4

Office Closure:

The university will close at noon Friday, and will be closed on Monday in recognition of Memorial Day. Normal business hours will resume at 8 am Tuesday.

Updated: 9:20 a.m. May 24

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Common Assignments: Writing in the Social Sciences

Although there may be some differences in writing expectations between disciplines, all writers of scholarly material are required to follow basic writing standards such as writing clear, concise, and grammatically correct sentences; using proper punctuation; and, in all Walden programs, using APA style. When writing in the social sciences, however, students must also be familiar with the goals of the discipline as these inform the discipline’s writing expectations. According to Ragin (1994), the primary goal of social science research is “identifying order in the complexity of social life” (para. 1). Serving the primary goal are the following secondary goals:

- Identifying general patterns and relationships

- Testing and refining theories

- Making predictions

- Interpreting culturally and historically significant phenomena

- Exploring diversity

- Giving voice

- Advancing new theories (Ragin, 1994, para. 2)

To accomplish these goals, social scientists examine and explain the behavior of individuals, systems, cultures, communities, and so on (Dartmouth Writing Program, 2005), with the hope of adding to the world’s knowledge of a particular issue. Students in the social sciences should have these goals at the back of their minds when choosing a research topic or crafting an effective research question. Instead of simply restating what is already known, students must think in terms of how they can take a topic a step further. The elements that follow are meant to give students an idea of what is expected of social science writers.

If you have content-specific questions, be sure to ask your instructor. The Writing Center is available to help you present your ideas as effectively as possible.

Because one cannot say everything there is to say about a particular subject, writers in the social sciences present their work from a particular perspective. For instance, one might choose to examine the problem of childhood obesity from a psychological perspective versus a social or environmental perspective. One’s particular contribution, proposition, or argument is commonly referred to as the thesis and, according to Gerring et al. (2009), a good thesis is one that is “ new, true, and significant ” (p. 2). To strengthen their theses, social scientists might consider presenting an argument that goes against what is currently accepted within that field while carefully addressing counterarguments, and adequately explaining why the issue under consideration matters (Gerring et al., 2009). For instance, one might interpret a claim made by a classical theorist differently from the manner in which it is commonly interpreted and expound on the implications of the new interpretation. The thesis is particularly important because readers want to know whether the writer has something new or significant to say about a given topic. Thus, as you review the literature, before writing, it is important to find gaps and creative linkages between ideas with the goal of contributing something worthwhile to an ongoing discussion. In crafting an argument, you must remember that social scientists place a premium on ideas that are well reasoned and based on evidence. For a contribution to be worthwhile, you must read the literature carefully and without bias; doing this will enable you to identify some of the subtle differences in the viewpoints presented by different authors and help you to better identify the gaps in the literature. Because the thesis is essentially the heart of your discussion, it must be argued objectively and persuasively.

In examining a research question, social scientists may present a hypothesis and they may choose to use either qualitative or quantitative methods of inquiry or both. The methods most often used include interviews, case studies, observations, surveys, and so on. The nature of the study should dictate the chosen method. (Do keep in mind that not all your papers will require that you employ the various methods of social science research; many will simply require that you analyze an issue and present a well reasoned argument.) When you write your capstones, however, you will be required to come to terms with the reliability of the methods you choose, the validity of your research questions, and ethical considerations. You will also be required to defend each one of these components. The research process as a whole may include the following: formulation of research question, sampling and measurement, research design, and analysis and recommendations. Keep in mind that your method will have an impact on the credibility of your work, so it is important that your methods are rigorous. Walden offers a series of research methods courses to help students become familiar with research methods in the social sciences.

Organization

Most social science research manuscripts contain the same general organizational elements:

Title

Abstract

Introduction

Literature Review

Methods

Results

Discussion

References

Note that the presentation follows a certain logic: in the introduction one presents the issue under consideration; in the literature review, one presents what is already known about the topic (thus providing a context for the discussion), identifies gaps, and presents one’s approach; in the methods section, one identifies the method used to gather data; in the results and discussion sections, one then presents and explains the results in an objective manner, acknowledging the limitations of the study (American Psychological Association [APA], 2020). One may end with a presentation of the implications of the study and areas upon which other researchers might focus.

For a detailed explanation of typical research paper organization and content, be sure to review Table 3.1 (pp. 77-81) and Table 3.2 (pp. 95-99) of your 7th edition APA manual.

Objectivity

Although social scientists continue to debate whether objectivity is achievable in the social sciences and whether theories really represent objective scientific analyses, they agree that one’s work must be presented as objectively as possible. This does not mean that writers cannot be passionate about their subject; it simply means that social scientists are to think of themselves primarily as observers and they must try to present their findings in a neutral manner, avoiding biases, and acknowledging opposing viewpoints.

It is important to note that instructors expect social science students to master the content of the discipline and to be able to use discipline appropriate language in their writing. Successful writers of social science literature have cultivated the thinking skills that are useful in their discipline and are able to communicate professionally, integrating and incorporating the language of their field as appropriate (Colorado State University, 2011). For instance, if one were writing about how aid impacts the development of less developed countries, it would be important to know and understand the different ways in which aid is defined within the field of development studies.

Colorado State University. (2011). Why assign WID tasks? http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/com6a1.cfm

Gerring, J., Yesnowitz, J., & Bird, S. (2009). General advice on social science writing . https://www.bu.edu/polisci/files/people/faculty/gerring/documents/WritingAdvice.pdf

Ragin, C. (1994). Construction social research: The unity and diversity of method . http://poli.haifa.ac.il/~levi/res/mgsr1.htm

Trochim, W. (2006). Research methods knowledge base . http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Writing in the Disciplines

- Next Page: Collaborative Writing in Business & Management

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

How to write a scientific report at university

David foster, professor in science and engineering at the university of manchester, explains the best way to write a successful scientific report.

David H Foster

At university, you might need to write scientific reports for laboratory experiments, computing and theoretical projects, and literature-based studies – and some eventually as research dissertations. All have a similar structure modelled on scientific journal articles. Their special format helps readers to navigate, understand and make comparisons across the research field.

Scientific report structure

The main components are similar for many subject areas, though some sections might be optional.

If you can choose a title, make it informative and not more than around 12 words. This is the average for scientific articles. Make every word count.

The abstract summarises your report’s content in a restricted word limit. It might be read separately from your full report, so it should contain a micro-report, without references or personalisation.

Usual elements you can include:

- Some background to the research area.

- Reason for the work.

- Main results.

- Any implications.

Ensure you omit empty statements such as “results are discussed”, as they usually are.

Introduction

The introduction should give enough background for readers to assess your work without consulting previous publications.

It can be organised along these lines:

- An opening statement to set the context.

- A summary of relevant published research.

- Your research question, hypothesis or other motivation.

- The purpose of your work.

- An indication of methodology.

- Your outcome.

Choose citations to any previous research carefully. They should reflect priority and importance, not necessarily recency. Your choices signal your grasp of the field.

Literature review

Dissertations and literature-based studies demand a more comprehensive review of published research than is summarised in the introduction. Fortunately, you don’t need to examine thousands of articles. Just proceed systematically.

- Use two to three published reviews to familiarise yourself with the field.

- Use authoritative databases such as Scopus or Web of Science to find the most frequently cited articles.

- Read these articles, noting key points. Experiment with their order and then turn them into sentences, in your own words.

- Get advice about expected review length and database usage from your individual programme.

Aims and objectives

Although the introduction describes the purpose of your work, dissertations might require something more accountable, with distinct aims and objectives.

The aim or aims represent the overall goal (for example, to land people on the moon). The objectives are the individual tasks that together achieve this goal (build rocket, recruit volunteers, launch rocket and so on).

The method section must give enough detail for a competent researcher to repeat your work. Technical descriptions should be accessible, so use generic names for equipment with proprietary names in parentheses (model, year, manufacturer, for example). Ensure that essential steps are clear, especially any affecting your conclusions.

The results section should contain mainly data and analysis. Start with a sentence or two to orient your reader. For numeric data, use graphs over tables and try to make graphs self-explanatory. Leave any interpretations for the discussion section.

The purpose of the discussion is to say what your results mean. Useful items to include:

- A reminder of the reason for the work.

- A review of the results. Ensure you are not repeating the results themselves; this should be more about your thoughts on them.

- The relationship between your results and the original objective.

- Their relationship to the literature, with citations.

- Any limitations of your results.

- Any knowledge you gained, new questions or longer-term implications.

The last item might form a concluding paragraph or be placed in a separate conclusion section. If your report is an internal document, ensure you only refer to your future research plans.

Try to finish with a “take-home” message complementing the opening of your introduction. For example: “This analysis has shown the process is feasible, but cost will decide its acceptability.”

Five common mistakes to avoid when writing your doctoral dissertation 9 tips to improve your academic writing Five resources to help students with academic writing

Acknowledgements

If appropriate, thank colleagues for advice, reading your report and technical support. Make sure that you secure their agreement first. Thank any funding agency. Avoid emotional declarations that you might later regret. That is all that is required in this section.

Referencing

Giving references ensures other authors’ ideas, procedures, results and inferences are credited. Use Web of Science or Scopus as mentioned earlier. Avoid databases giving online sources without journal publication details because they might be unreliable.

Don’t refer to Wikipedia. It isn’t a citable source.

Use one referencing style consistently and make sure it matches the required style of your degree or department. Choose either numbers or author and year to refer to the full references listed near the end of your report. Include all publication details, not just website links. Every reference should be cited in the text.

Figures and tables

Each figure should have a caption below with a label, such as “Fig. 1”, with a title and a sentence or two about what it shows. Similarly for tables, except that the title appears above. Every figure and table should be cited in the text.

Theoretical studies

More flexibility is possible with theoretical reports, but extra care is needed with logical development and mathematical presentation. An introduction and discussion are still needed, and possibly a literature review.

Final steps

Check that your report satisfies the formatting requirements of your department or degree programme. Check for grammatical errors, misspellings, informal language, punctuation, typos and repetition or omission.

Ask fellow students to read your report critically. Then rewrite it. Put it aside for a few days and read it afresh, making any new edits you’ve noticed. Keep up this process until you are happy with the final report.

You may also like

.css-185owts{overflow:hidden;max-height:54px;text-indent:0px;} How to write an undergraduate university dissertation

Grace McCabe

How to use digital advisers to improve academic writing

How to write a successful research piece at university

Maggie Tighe

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Writing a Field Report

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Research Effectively

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Bibliography

The purpose of a field report in the social sciences is to describe the observation of people, places, and/or events and to analyze that observation data in order to identify and categorize common themes in relation to the research problem underpinning the study. The content represents the researcher's interpretation of meaning found in data that has been gathered during one or more observational events.

Flick, Uwe The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection . London: SAGE Publications, 2018.

How to Approach Writing a Field Report

How to Begin

Field reports are most often assigned in disciplines of the applied social sciences [e.g., social work, anthropology, gerontology, criminal justice, education, law, the health care professions] where it is important to build a bridge of relevancy between the theoretical concepts learned in the classroom and the practice of actually doing the work you are being taught to do. Field reports are also common in certain science disciplines [e.g., geology] but these reports are organized differently and serve a different purpose than what is described below.

Professors will assign a field report with the intention of improving your understanding of key theoretical concepts through a method of careful and structured observation of, and reflection about, people, places, or phenomena existing in their natural settings. Field reports facilitate the development of data collection techniques and observation skills and they help you to understand how theory applies to real world situations. Field reports are also an opportunity to obtain evidence through methods of observing professional practice that contribute to or challenge existing theories.

We are all observers of people, their interactions, places, and events; however, your responsibility when writing a field report is to create a research study based on data generated by the act of designing a specific study, deliberate observation, a synthesis of key findings, and an interpretation of their meaning. When writing a field report you need to:

- Systematically observe and accurately record the varying aspects of a situation . Always approach your field study with a detailed protocol about what you will observe, where you should conduct your observations, and the method by which you will collect and record your data.

- Continuously analyze your observations . Always look for the meaning underlying the actions you observe. Ask yourself: What's going on here? What does this observed activity mean? What else does this relate to? Note that this is an on-going process of reflection and analysis taking place for the duration of your field research.

- Keep the report’s aims in mind while you are observing . Recording what you observe should not be done randomly or haphazardly; you must be focused and pay attention to details. Enter the observation site [i.e., "field"] with a clear plan about what you are intending to observe and record while, at the same time, being prepared to adapt to changing circumstances as they may arise.

- Consciously observe, record, and analyze what you hear and see in the context of a theoretical framework . This is what separates data gatherings from simple reporting. The theoretical framework guiding your field research should determine what, when, and how you observe and act as the foundation from which you interpret your findings.

Techniques to Record Your Observations Although there is no limit to the type of data gathering technique you can use, these are the most frequently used methods:

Note Taking This is the most commonly used and easiest method of recording your observations. Tips for taking notes include: organizing some shorthand symbols beforehand so that recording basic or repeated actions does not impede your ability to observe, using many small paragraphs, which reflect changes in activities, who is talking, etc., and, leaving space on the page so you can write down additional thoughts and ideas about what’s being observed, any theoretical insights, and notes to yourself that are set aside for further investigation. See drop-down tab for additional information about note-taking.

Photography With the advent of smart phones, high quality photographs can be taken of the objects, events, and people observed during a field study. Photographs can help capture an important moment in time as well as document details about the space where your observation takes place. Taking a photograph can save you time in documenting the details of a space that would otherwise require extensive note taking. However, be aware that flash photography could undermine your ability to observe unobtrusively so assess the lighting in your observation space; if it's too dark, you may need to rely on taking notes. Also, you should reject the idea that photographs are some sort of "window into the world" because this assumption creates the risk of over-interpreting what they show. As with any product of data gathering, you are the sole instrument of interpretation and meaning-making, not the object itself. Video and Audio Recordings Video or audio recording your observations has the positive effect of giving you an unfiltered record of the observation event. It also facilitates repeated analysis of your observations. This can be particularly helpful as you gather additional information or insights during your research. However, these techniques have the negative effect of increasing how intrusive you are as an observer and will often not be practical or even allowed under certain circumstances [e.g., interaction between a doctor and a patient] and in certain organizational settings [e.g., a courtroom]. Illustrations/Drawings This does not refer to an artistic endeavor but, rather, refers to the possible need, for example, to draw a map of the observation setting or illustrating objects in relation to people's behavior. This can also take the form of rough tables or graphs documenting the frequency and type of activities observed. These can be subsequently placed in a more readable format when you write your field report. To save time, draft a table [i.e., columns and rows] on a separate piece of paper before an observation if you know you will be entering data in that way.

NOTE: You may consider using a laptop or other electronic device to record your notes as you observe, but keep in mind the possibility that the clicking of keys while you type or noises from your device can be obtrusive, whereas writing your notes on paper is relatively quiet and unobtrusive. Always assess your presence in the setting where you're gathering the data so as to minimize your impact on the subject or phenomenon being studied.

ANOTHER NOTE : Techniques of observation and data gathering are not innate skills; they are skills that must be learned and practiced in order to achieve proficiency. Before your first observation, practice the technique you plan to use in a setting similar to your study site [e.g., take notes about how people choose to enter checkout lines at a grocery store if your research involves examining the choice patterns of unrelated people forced to queue in busy social settings]. When the act of data gathering counts, you'll be glad you practiced beforehand.

Examples of Things to Document While Observing

- Physical setting . The characteristics of an occupied space and the human use of the place where the observation(s) are being conducted.

- Objects and material culture . This refers to the presence, placement, and arrangement of objects that impact the behavior or actions of those being observed. If applicable, describe the cultural artifacts representing the beliefs--values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions--used by the individuals you are observing.

- Use of language . Don't just observe but listen to what is being said, how is it being said, and, the tone of conversation among participants.

- Behavior cycles . This refers to documenting when and who performs what behavior or task and how often they occur. Record at which stage is this behavior occurring within the setting.

- The order in which events unfold . Note sequential patterns of behavior or the moment when actions or events take place and their significance.

- Physical characteristics of subjects. If relevant, note age, gender, clothing, etc. of individuals being observed.

- Expressive body movements . This would include things like body posture or facial expressions. Note that it may be relevant to also assess whether expressive body movements support or contradict the language used in conversation [e.g., detecting sarcasm].

Brief notes about all of these examples contextualize your observations; however, your observation notes will be guided primarily by your theoretical framework, keeping in mind that your observations will feed into and potentially modify or alter these frameworks.

Sampling Techniques

Sampling refers to the process used to select a portion of the population for study . Qualitative research, of which observation is one method of data gathering, is generally based on non-probability and purposive sampling rather than probability or random approaches characteristic of quantitatively-driven studies. Sampling in observational research is flexible and often continues until no new themes emerge from the data, a point referred to as data saturation.

All sampling decisions are made for the explicit purpose of obtaining the richest possible source of information to answer the research questions. Decisions about sampling assumes you know what you want to observe, what behaviors are important to record, and what research problem you are addressing before you begin the study. These questions determine what sampling technique you should use, so be sure you have adequately answered them before selecting a sampling method.

Ways to sample when conducting an observation include:

Ad Libitum Sampling -- this approach is not that different from what people do at the zoo--observing whatever seems interesting at the moment. There is no organized system of recording the observations; you just note whatever seems relevant at the time. The advantage of this method is that you are often able to observe relatively rare or unusual behaviors that might be missed by more deliberate sampling methods. This method is also useful for obtaining preliminary observations that can be used to develop your final field study. Problems using this method include the possibility of inherent bias toward conspicuous behaviors or individuals and that you may miss brief interactions in social settings.

Behavior Sampling -- this involves watching the entire group of subjects and recording each occurrence of a specific behavior of interest and with reference to which individuals were involved. The method is useful in recording rare behaviors missed by other sampling methods and is often used in conjunction with focal or scan methods. However, sampling can be biased towards particular conspicuous behaviors.

Continuous Recording -- provides a faithful record of behavior including frequencies, durations, and latencies [the time that elapses between a stimulus and the response to it]. This is a very demanding method because you are trying to record everything within the setting and, thus, measuring reliability may be sacrificed. In addition, durations and latencies are only reliable if subjects remain present throughout the collection of data. However, this method facilitates analyzing sequences of behaviors and ensures obtaining a wealth of data about the observation site and the people within it. The use of audio or video recording is most useful with this type of sampling.

Focal Sampling -- this involves observing one individual for a specified amount of time and recording all instances of that individual's behavior. Usually you have a set of predetermined categories or types of behaviors that you are interested in observing [e.g., when a teacher walks around the classroom] and you keep track of the duration of those behaviors. This approach doesn't tend to bias one behavior over another and provides significant detail about a individual's behavior. However, with this method, you likely have to conduct a lot of focal samples before you have a good idea about how group members interact. It can also be difficult within certain settings to keep one individual in sight for the entire period of the observation.

Instantaneous Sampling -- this is where observation sessions are divided into short intervals divided by sample points. At each sample point the observer records if predetermined behaviors of interest are taking place. This method is not effective for recording discrete events of short duration and, frequently, observers will want to record novel behaviors that occur slightly before or after the point of sampling, creating a sampling error. Though not exact, this method does give you an idea of durations and is relatively easy to do. It is also good for recording behavior patterns occurring at a specific instant, such as, movement or body positions.

One-Zero Sampling -- this is very similar to instantaneous sampling, only the observer records if the behaviors of interest have occurred at any time during an interval instead of at the instant of the sampling point. The method is useful for capturing data on behavior patterns that start and stop repeatedly and rapidly, but that last only for a brief period of time. The disadvantage of this approach is that you get a dimensionless score for an entire recording session, so you only get one one data point for each recording session.

Scan Sampling -- this method involves taking a census of the entire observed group at predetermined time periods and recording what each individual is doing at that moment. This is useful for obtaining group behavioral data and allows for data that are evenly representative across individuals and periods of time. On the other hand, this method may be biased towards more conspicuous behaviors and you may miss a lot of what is going on between observations, especially rare or unusual behaviors. It is also difficult to record more than a few individuals in a group setting without missing what each individual is doing at each predetermined moment in time [e.g., children sitting at a table during lunch at school].

Alderks, Peter. Data Collection . Psychology 330 Course Documents. Animal Behavior Lab. University of Washington; Emerson, Robert M. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations . 2nd ed. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 2001; Emerson, Robert M. et al. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography . Paul Atkinson et al., eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), 352-368; Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Hazel, Spencer. "The Paradox from Within: Research Participants Doing-Being-Observed." Qualitative Research 16 (August 2016): 446-457; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports . Scribd Online Library; Presser, Jon and Dona Schwartz. “Photographs within the Sociological Research Process.” In Image-based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers . Jon Prosser, editor (London: Falmer Press, 1998), pp. 115-130; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing . UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports . Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

Structure and Writing Style

How you choose to format your field report is determined by the research problem, the theoretical perspective that is driving your analysis, the observations that you make, and/or specific guidelines established by your professor. Since field reports do not have a standard format, it is worthwhile to determine from your professor what the preferred organization should be before you begin to write. Note that field reports should be written in the past tense. With this in mind, most field reports in the social sciences include the following elements:

I. Introduction The introduction should describe the research problem, the specific objectives of your research, and the important theories or concepts underpinning your field study. The introduction should describe the nature of the organization or setting where you are conducting the observation, what type of observations you have conducted, what your focus was, when you observed, and the methods you used for collecting the data. You should also include a review of pertinent literature related to the research problem, particularly if similar methods were used in prior studies. Conclude your introduction with a statement about how the rest of the paper is organized.

II. Description of Activities

Your readers only knowledge and understanding of what happened will come from the description section of your report because they have not been witness to the situation, people, or events that you are writing about. Given this, it is crucial that you provide sufficient details to place the analysis that will follow into proper context; don't make the mistake of providing a description without context. The description section of a field report is similar to a well written piece of journalism. Therefore, a helpful approach to systematically describing the varying aspects of an observed situation is to answer the "Five W’s of Investigative Reporting." These are:

- What -- describe what you observed. Note the temporal, physical, and social boundaries you imposed to limit the observations you made. What were your general impressions of the situation you were observing. For example, as a student teacher, what is your impression of the application of iPads as a learning device in a history class; as a cultural anthropologist, what is your impression of women's participation in a Native American religious ritual?

- Where -- provide background information about the setting of your observation and, if necessary, note important material objects that are present that help contextualize the observation [e.g., arrangement of computers in relation to student engagement with the teacher].

- When -- record factual data about the day and the beginning and ending time of each observation. Note that it may also be necessary to include background information or key events which impact upon the situation you were observing [e.g., observing the ability of teachers to re-engage students after coming back from an unannounced fire drill].

- Who -- note background and demographic information about the individuals being observed e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, and/or any other variables relevant to your study]. Record who is doing what and saying what, as well as, who is not doing or saying what. If relevant, be sure to record who was missing from the observation.

- Why -- why were you doing this? Describe the reasons for selecting particular situations to observe. Note why something happened. Also note why you may have included or excluded certain information.

III. Interpretation and Analysis

Always place the analysis and interpretations of your field observations within the larger context of the theories and issues you described in the introduction. Part of your responsibility in analyzing the data is to determine which observations are worthy of comment and interpretation, and which observations are more general in nature. It is your theoretical framework that allows you to make these decisions. You need to demonstrate to the reader that you are looking at the situation through the eyes of an informed viewer, not as a lay person.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when analyzing your observations:

- What is the meaning of what you have observed?

- Why do you think what you observed happened? What evidence do you have for your reasoning?

- What events or behaviors were typical or widespread? If appropriate, what was unusual or out of ordinary? How were they distributed among categories of people?

- Do you see any connections or patterns in what you observed?

- Why did the people you observed proceed with an action in the way that they did? What are the implications of this?

- Did the stated or implicit objectives of what you were observing match what was achieved?

- What were the relative merits of the behaviors you observed?

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the observations you recorded?

- Do you see connections between what you observed and the findings of similar studies identified from your review of the literature?

- How do your observations fit into the larger context of professional practice? In what ways have your observations possibly changed or affirmed your perceptions of professional practice?

- Have you learned anything from what you observed?

NOTE: Only base your interpretations on what you have actually observed. Do not speculate or manipulate your observational data to fit into your study's theoretical framework.

IV. Conclusion and Recommendations

The conclusion should briefly recap of the entire study, reiterating the importance or significance of your observations. Avoid including any new information. You should also state any recommendations you may have. Be sure to describe any unanticipated problems you encountered and note the limitations of your study. The conclusion should not be more than two or three paragraphs.

V. Appendix

This is where you would place information that is not essential to explaining your findings, but that supports your analysis [especially repetitive or lengthy information], that validates your conclusions, or that contextualizes a related point that helps the reader understand the overall report. Examples of information that could be included in an appendix are figures/tables/charts/graphs of results, statistics, pictures, maps, drawings, or, if applicable, transcripts of interviews. There is no limit to what can be included in the appendix or its format [e.g., a DVD recording of the observation site], provided that it is relevant to the study's purpose and reference is made to it in the report. If information is placed in more than one appendix ["appendices"], the order in which they are organized is dictated by the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

VI. References

List all sources that you consulted and obtained information from while writing your field report. Note that field reports generally do not include further readings or an extended bibliography. However, consult with your professor concerning what your list of sources should be included. Be sure to write them in the preferred citation style of your discipline [i.e., APA, Chicago, MLA, etc.].

Alderks, Peter. Data Collection . Psychology 330 Course Documents. Animal Behavior Lab. University of Washington; Emerson, Robert M. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations . 2nd ed. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 2001; Emerson, Robert M. et al. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography . Paul Atkinson et al., eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), 352-368; Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports . Scribd Online Library; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing . UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports . Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Study

- Next: About Informed Consent >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2023 10:50 AM

- URL: https://libguides.pointloma.edu/ResearchPaper

Writing & Stylistics Guides

- General Writing & Stylistics Guides

Writing in the Disciplines

- Arts & Humanities

- Creative Writing & Journalism

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science, Data Science, Engineering

- Writing in Business

- Literature Reviews & Writing Your Thesis

- Publishing Books & Articles

- MLA Stylistics

- Chicago Stylistics

- APA Stylistics

- Harvard Stylistics

Need Help? Ask a Librarian!

You can always e-mail your librarian for help with your questions, book an online consultation with a research specialist, or chat with us in real-time!

Once you've gotten comfortable with the basic elements of style and conventions of writing, you'll find that the craft of writing is not a one-size-fits-all pursuit: different disciplines employ different conventions and styles, which you'll need to be familiar with. Learn more about the discipline-specific styles for Creative Writing (including journalism, writing fiction, and creative non-fiction), writing in the Social Sciences (including psychology, gender & sexuality studies, sociology, social work, international relations, and politics), and crafting your essay in the Arts and Humanities (including history, literature, music, and the fine arts).

- << Previous: General Writing & Stylistics Guides

- Next: Arts & Humanities >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 4:45 AM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/WritingGuides

- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Renowned historian of modern social science Dorothy Ross dies at 87

The first woman to be named chair of the history department, ross's research focused on historical writing in the social sciences, revealing insights that transformed scholars' understanding of the past.

By Rachel Wallach

Dorothy Ross, pioneering historian of the origins of modern social science and a professor emerita in the Johns Hopkins University Department of History , died last week. She was 87.

Ross's research focused on historical writing in the social sciences, revealing insights from the history of fields including psychology, economics, political science, and sociology that transformed scholars' understanding of the past. The depth of her dedication to graduate education was illustrated by her 2023 establishment of the New Directions Fund in the History Department to support graduate student research and conference travel.

Image caption: Dorothy Ross

"Dorothy was an exemplary scholar, a generous mentor, and a kind colleague," said Tobie Meyer-Fong , professor and chair of the Department of History. "She was incredibly supportive of me when I first joined the department and continued to offer wise counsel as recently as this past semester. She was a role model both professionally and personally: She was an ambitious and brilliant historian, an outstanding teacher of graduate students, a loving wife, a devoted mother and grandmother, and a kind and caring friend. She made it seem possible and desirable to have both professional and family commitments."