Explore Jobs

- Jobs Near Me

- Remote Jobs

- Full Time Jobs

- Part Time Jobs

- Entry Level Jobs

- Work From Home Jobs

Find Specific Jobs

- $15 Per Hour Jobs

- $20 Per Hour Jobs

- Hiring Immediately Jobs

- High School Jobs

- H1b Visa Jobs

Explore Careers

- Business And Financial

- Architecture And Engineering

- Computer And Mathematical

Explore Professions

- What They Do

- Certifications

- Demographics

Best Companies

- Health Care

- Fortune 500

Explore Companies

- CEO And Executies

- Resume Builder

- Career Advice

- Explore Majors

- Questions And Answers

- Interview Questions

How To Answer “Why Do You Want To Be A Nurse?” (With Examples)

- Cover Letter

- Registered Nurse Interview Questions

- Registered Nurse Job Description

- Why Did You Choose Nursing?

When you’re in a nursing interview, you’ll hear the common question “Why do you want to be a nurse ?”, so it’s essential to know how to answer it. Your answer should reflect on what it was that drew you to nursing and tell a story about it, such as the moment it was clear that you wanted to be a nurse.

Whether you want to be a pediatric nurse , emergency department nurse, or travel nurse, we’ll go over how to answer “Why did you choose nursing as a career?”, why interviewers ask this question, as well as some common mistakes to avoid.

Key Takeaways:

Try to think of a story or a moment that made it clear that a nursing career was right for you.

Interviewers ask “Why do you want to become a nurse?” so you can highlight your passion for nursing and what got you interested in the field.

Avoid saying anything negative because it can often be a red flag for interviewers.

How to answer “Why do you want to be a nurse?”

Example answers to “why do you want to be a nurse”, why interviewers ask this interview question, common mistakes to avoid when answering, interview tips for answering this question, possible follow-up questions:, nurse career path faq, final thoughts.

- Sign Up For More Advice and Jobs

To answer “Why do you want to be a nurse?” you should first ask yourself questions as to why you want to be a nurse, start at the root, and tell your interviewer a story. Below is a more detailed list of how to answer this interview question .

As yourself questions. Before the interview, ask yourself, putting money and career goals aside, why do YOU want to be a nurse? Consider the following questions to better understand your reasoning:

Do you want to help people?

Does the medical field excite you?

Do you have certain skills, such as communication or concentration under duress, that naturally fit the position?

Do you thrive when you get to build relationships with people?

Do you love both science and working with people?

Focus on these aspects of yourself when you are asked why you are choosing nursing as a career.

Start at the root. If you’ve wanted to be a nurse since you were a kid, start there. If you got into medicine thanks to an impactful college professor , make that your starting point.

Tell a story. Most interviewers prefer narratives over bullet point facts — especially with a personal question like this. Don’t feel like you have to make up some great tale about how a nurse saved the day when you were a child, but bring in real moments when it became clear that nursing was the career for you.

Talk about people and experiences. Nursing is all about building relationships, so your answer should touch on your empathy and ability to form bonds with the people you work with and serve. In this way, your answer will show that you want to be a nurse because you truly enjoy the process of nursing.

Bring it to the future. Close your answer with a nod to the future and what you’d like to accomplish in your brilliant new nursing career. Bringing your answer from the past to the future shows that you’re forward-thinking and determined enough to make your dreams a reality.

Below are example answers to “Why do you want to be a nurse?” for different scenarios such as pediatric or emergency room nursing. Remember to tailor your answers to your specific needs when you answer in your interview.

Pediatric nurse example answer

“I have wanted to get into nursing since I was very young. One of my earliest memories is of a nurse taking care of me when I had to go to the hospital for stitches. She was so kind and gentle with me that I didn’t even cry or panic. I remember leaving thinking that was the kind of person I wanted to be when I grew up. Ever since then, everything I have done has been working towards becoming a nurse.”

Emergency room nurse example answer

“When I was in college I took a course on basic first aid and found it super interesting. I started signing up for volunteer first aid positions and some of my fellow volunteers were nurses. I was curious about their job and the more I learned about what they did the more I found myself excited by the prospect of helping people in medical situations. I made friends with these nurses and they helped guide me through the application process.”

Travel nurse example answer

“Medicine is such an exciting field, and one of the biggest joys of nursing is that I’m always learning new things. I know people who dread getting their necessary CEUs every year, but for me, it’s a perk of the career. “For instance, just last year I completed my certification from the Wilderness Medical Society and can now serve as medical staff on the Appalachian Trail. But from Diabetes for APRNs to Nursing for Infertility courses, I’m always able to maintain my passion for nursing through continuous discovery and wonder at the medical field.”

Critical care nurse example answer

“I believe in helping people, especially in times of extreme need. When I worked as an EMT I was always the one asked to facilitate information between any involved party. I want to expand this skill and I think nursing is a good fit for me. My interests and experience with medical professionals are good for this job.”

Nurse midwife example answer

“I want to be a nurse because I am deeply committed to providing compassionate healthcare to women during one of the most significant and transformative moments of their life. Being a nurse midwife will allow me to empower women by advocating their choices and preferences during childbirth. “Being a nurse midwife will also allow me to make a positive impact on the lives of women and their families. I will be able to provide personalized care, emotional support , and educational resources to help ensure a smooth and empowering birthing experience for my patients.”

Oncology nurse example answer

“I want to be an oncology nurse because this field is driven by a profound desire to make a meaningful difference in the lives of those fighting cancer. I am committed to providing compassionate care to patients during their cancer journey. “Working as an oncology nurse also has the opportunities to be part of cutting-edge research and advancements in cancer treatments. I want to be at the forefront of innovation and help contribute to the improvement of cancer care outcomes.”

The interviewer will ask why you want to be a nurse to know how serious you are about the position. This isn’t a career to take lightly because there are many challenges.

Nursing is a profession with a prerequisite for assisting others in potentially high-stress environments. So by answering this question, you are given the opportunity to highlight not only your skills but more importantly, your passion for nursing and ability to keep cool under pressure.

Additionally, interviewers hope to learn why you got interested in the field in the first place. Telling a story about an impactful experience with a medical professional or about the sense of satisfaction you feel when helping a patient can help illustrate that you’re not only skillful but also have deep compassion for the people you’ll be working with.

You should avoid saying anything negative because it can be a red flag for the interviewer. Here are some other common mistakes you should avoid when answering:

Saying anything negative. A negative response will be a red flag for the interviewer. If you are one to complain or see the worse in a situation, this will make you a difficult coworker in an already difficult field.

Focusing on money or self-serving reasons. Even if the wages are an attractive feature of the profession, mentioning this as a reason will hurt you. The interviewer is looking for an answer that goes beyond your own needs.

Unrelated anecdotes. Don’t get caught up in telling stories about nursing that have nothing to do with you or the job. Remember to keep things relevant and concise.

Your answer should be positive and you should use a personal experience to help you answer and tell a story. Here are some more tips to keep in mind when answering this question:

Be positive. Nothing will concern an interviewer more if you are cynical and negative in an interview where the job requires a strong sense of empathy and selflessness. This does not mean you can’t, nor should, ignore the challenges of the profession. If you can reframe these difficulties with a positive mindset and a “can do” attitude, you will strengthen your impact in the interview.

Be concise. A long-winded, rambling answer may give the impression that you have not considered the question ahead of time. That said, if you rush through your words, you may concern the interviewer as well. So, don’t be afraid to take breaths or have moments of silence, but choose your words carefully and effectively. Concise communication is a huge part of the nursing profession so here is an opportunity to highlight that skill.

Use personal experience. When answering the question “Why did you choose nursing as a career?” it can really help to bring in a personal touch to the response. This creates a unique answer that can help you stand out among other candidates. The personal experience may also reveal a moment of inspiration pointing towards why you chose nursing as a career.

Remember the job description. Use the skills required in the job description and apply them to yourself as you explain your interest in the field. Integrate them with care, you are not trying to restate your resume . Instead, consider how your skills have developed over time and how that relates to your interest in nursing. Remember, skills are developed through some kind of interest too.

Research the organization/department. Wherever you are applying to is going to have unique characteristics. Perhaps the organization focuses on low-income individuals or the elderly or intensive care patients. You may be able to bring this into your answer. Even if you do not, it is still good to give you context. By understanding where you’re applying to, you strengthen the explanation of why you are applying.

Practice your answer. Before the interview, practice this answer, preferably with someone else who can give you feedback such as a friend or family member. However, if you do not have that opportunity, practice in front of a mirror or, better yet, record yourself on your phone and listen back to what you said. In the end, you want to “train” for this question by giving yourself the opportunity to run through it a couple of times with the chance to tweak your response.

After the question “Why did you choose a nursing career?” there will most likely be follow-up questions. Here are some examples of other common interview questions and some tips on how to answer them. This will help you prepare yourself for the direction the interview may take.

What do you think is most difficult about being a nurse? Why?

Be aware of certain challenges of nursing ahead of time. Do some research . The worst thing you can do for yourself is be caught off guard by this question.

How are you at handling stress?

Consider what techniques you use for reducing stress. It is going to be important to show your competency. Consider answering in a way that reveals you to be a team player and aware of the stresses of your coworkers as well.

What are your long-term career goals?

The interviewer is going to be gauging your seriousness in becoming a nurse. It is not a profession that you can just “try-out”, so give an answer that shows sincere consideration for a long-term medical profession. Note: This does not necessarily tie you strictly to nursing. Many managers and hospital administrators come from nursing backgrounds.

Why do you want to work here?

Many interviewers will want to hear about not only your passion for nursing as a career but also how your passions align with their organization.

Look up the mission and vision of the facility before your interview and talk about how that resonates with you, or give an example of how you’ve seen them in action and want to be a part of that.

What drove your interest in this specialty?

Not every nurse fits well in every nursing role, so your interviewers will likely ask you why you want this particular job.

Whether this is the specialty you’ve always worked in or you’re trying something new, structure your answer similarly to your answer to the “Why do you want to be a nurse?” question.

Why would one want to be a nurse?

Many people want to be a nurse because it gives them an opportunity to help people in a meaningful way. Nurses not only perform specialized tasks that are vital to a person’s well-being, but they also get to emotionally support people who are going through an incredibly difficult time.

This can be as simple as being a calm, friendly presence or advocating for them with the rest of the medical staff, but it makes a huge impact on people’s lives.

In addition to this, many people choose to become nurses over another occupation that helps people because they love science and medicine or love the fast-paced, challenging work environment.

What is a good weakness to say in a nursing interview?

A good weakness to say in a nursing interview is a weakness that you’re actively working on. Whether your greatest weakness is that you’re too detailed with your paperwork or say yes to too many people and requests, always follow it up by explaining the steps you’re taking to overcome that weakness.

Hiring managers don’t expect you to be perfect, but they do expect you to be self-aware and take the initiative to minimize the impact of your weak spots.

What are the 6 C’s of nursing?

The 6 C’s of nursing are care, compassion, communication, courage, and commitment. These are principles taught to many nurses to help them learn how to give excellent care to patients.

They also help to set cultural expectations at medical facilities, since all of the nurses are upheld to this standard, no matter what their educational background or specialty.

What are some common nursing interview questions?

Some common nursing interview questions include:

What skills do you think are important for nurses to possess?

Describe your experience as a nurse and what you’ve learned from it.

How would you manage an uncooperative patient?

How well do you thrive in a fast-paced environment?

There are so many nursing jobs out there and nurses are in high demand. You will want to know what you’re getting yourself into before you are asked at the interview what brings you to the field.

Knowledge is power, so knowing your response to “Why did you choose a nursing career?” is crucial for success. This is your moment to shine and show why you are the best candidate for the job.

Those who are able to answer with sincerity and empathy are the types of nurses all organizations will want. So get yourself ready and figure out ahead of time why you want to be a nurse.

Nightingale College – How To Ace Your Nursing Job Interview: Questions, Answers & Tips

The College of St. Scholastica – Why do you want to be a nurse? Students share their sentiments

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating / 5. Vote count:

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Conor McMahon is a writer for Zippia, with previous experience in the nonprofit, customer service and technical support industries. He has a degree in Music Industry from Northeastern University and in his free time he plays guitar with his friends. Conor enjoys creative writing between his work doing professional content creation and technical documentation.

Recent Job Searches

- Registered Nurse Jobs Resume Location

- Truck Driver Jobs Resume Location

- Call Center Representative Jobs Resume Location

- Customer Service Representative Jobs Resume

- Delivery Driver Jobs Resume Location

- Warehouse Worker Jobs Resume Location

- Account Executive Jobs Resume Location

- Sales Associate Jobs Resume Location

- Licensed Practical Nurse Jobs Resume Location

- Company Driver Jobs Resume

Related posts

15 Job Search Tips Guaranteed To Get You Hired

How To Answer The Interview Question “What Are Your Career Goals?” (With Examples)

How To Answer “What Is Your Desired Salary?” (With Examples)

How To Nail Popular Teamwork Interview Questions

- Career Advice >

- Get The Job >

- Why Do You Want To Be A Nurse

Online Nursing Essays

Top Quality Nursing Papers

Why I Want To Be A Nurse Essay

Applying for nursing school is an exciting step towards a rewarding career helping others. The nursing school essay, also known as a personal statement, is a critical part of the application. This is your chance to showcase your passion for the nursing profession and explain why you want to become a nurse.

This guide will show you exactly what admission committees are looking for in a strong nursing school application essay. Let’s walk through how to plan, write, and polish your “why I want to be a nurse” personal statement so it stands out from the competition.

What To Include In Your Nursing Essay

Writing a compelling nursing school essay requires advanced planning and preparation. Follow these tips to create an effective personal statement:

Plan Your Nurse Essay

The first step is to carefully conceptualize your nursing school admissions essay. Jot down some notes answering these key questions:

- Why do you want to go into nursing?

- What personal experiences or traits draw you to the field of nursing?

- How have you demonstrated commitment to caring for others?

- What are your academic and professional qualifications for nursing?

From here, you can start mapping out a logical flow of key points to cover in your nursing school application essay.

Show an Emotional Connection to the Profession

Admission committees want to see that you have genuine passion and empathy for the nursing career choice. Dedicate part of your personal statement to describing your intrinsic motivations and positive impacts for desiring to become a nurse.

Avoid cliché reasons like “I want to help people.” Instead, get specific by sharing a personal anecdote that emotionally moved you towards nursing.

Here’s an example of how you could open your nursing school entrance essay by highlighting a meaningful patient-care interaction:

“Holding Mrs. Wilson’s trembling hand, I watched her fearful eyes relax as I reassured her that the medical team would take excellent care of her. At that moment, providing empathetic comfort to calm her nerves despite the clinical chaos around us, I knew deep down that nursing was my calling.”

This introduction immediately establishes an emotional pull towards the human side of healthcare. From here, explain how this or similar experiences instilled a drive in you to become a nurse.

Show That You Care

Much of nursing is providing compassionate, person-centered care. Therefore, your “why I want to be a nurse” essay should emphasize your ability to be caring, empathetic, patient, and comforting to others.

Share examples that showcase your natural inclination for caregiving:

“Volunteering at the Red Cross shelter after the wildfires by comforting displaced families demonstrated my patience and attentiveness to those suffering. Even as some evacuees grew frustrated by the chaos, I calmly reassured them that we would do everything possible to assist with their recoveries and ensure they felt cared for.”

This example highlights key soft skills needed in nursing as a career, like compassion, active listening, the desire to help, and providing a calming presence under pressure.

Share Your Aspirations

A strong application essay will also articulate your goals and vision for contributing to the nursing field. What are you hoping to achieve through a career in nursing?

Here is an example of discussing aspirations in a nursing school personal statement:

“My long-term aspiration is to become a nurse leader by earning an advanced degree and management experience. I aim to leverage my organizational, communication and critical thinking skills to mentor junior staff, improve operational workflows, and advocate for policies that enhance quality of care. In nursing, I’ve found my true calling – to provide critical care, and help others by being a source of compassion and driving excellence in healthcare delivery.”

This type of self-motivated, forward-looking vision demonstrates maturity, strong goals, and natural leadership qualities.

Describe Your Nursing Skills and Qualifications

Finally, your nursing school entrance essay should summarize the skills; profession offers, and experience that makes you an excellent candidate for the nursing program. Highlight relevant strengths like:

- Academic achievements (science/healthcare courses, GPA, etc.)

- Extracurricular activities (volunteering, internships, etc.)

- Relevant work experience (patient care roles like CNA, medical assistant, etc.)

- Other transferable skills (communication, leadership, teamwork, critical thinking, etc.)

For example:

“My passion for science, healthcare experience as a CNA, and volunteering at a community health fair have prepared me to thrive in the intellectually stimulating and collaborative nursing curriculum. I bring dedication, attention to detail, and a strong work ethic as demonstrated by my 3.8 GPA studying Biology at the University of Michigan.”

With application essays, it’s all about showcasing why you would make an outstanding addition to the nursing program, making a difference through your qualifications and intangible traits.

How Do You Write an Introduction to a Nurse Essay?

Now that you’ve brainstormed content ideas, it’s time to turn them into a polished personal statement. Here are some tips for crafting an attention-grabbing introduction to your nursing school essay:

Hook the Reader with a Personal Story

One of the most engaging ways to start writing your essay is by recounting a brief personal story that illuminates your drive to become a nurse. This can immediately immerse the reader in your intrinsic motivations.

For example , you could open with an anecdote describing a meaningful instance of care and comfort you provided to someone in need:

“Tears streamed down Mrs. Hernandez’s face as she told me about losing her husband to cancer last year. As a hospice volunteer, I held her hand, listening intently to her painful story of grief and loss…”

This type of vivid introduction pulls the reader into the narrative straight away. From here, you can continue sharing details about the scenario and its influence on your desire to pursue nursing.

Illustrate the Human Impact of Nursing

Another compelling way to begin your nursing personal statement is by painting a picture of nursing’s profound impact on patients and their families. This highlights your understanding of the profession’s vital role.

For instance:

“Looking a trembling new mother in the eyes as she first held her newborn, relieved knowing both were safe and healthy after a complicated delivery – that is the human difference nurses make each and every day.”

This type of introduction emphasizes nursing’s profound emotional impact on patients during vulnerable yet joyful moments. It activates the reader’s empathy by bringing them into the vivid scene while showing your own insight into the medical field.

Articulate Passion for Helping Others

Finally, you can start your nursing application essay by asserting your resounding passion for caring for others. This clear expression allows you to succinctly introduce central values like empathy and compassion.

“Ever since I was a young volunteer candy striper in my local hospital, I’ve held an unwavering passion for helping those suffering through the profound act of nursing. I was born to care for others.”

This authoritative opening clearly states your emotional connection to nursing in a compelling yet concise way. You can then build on this assertion of passion through personal examples and further explanation.

No matter how you start your nursing school essay, the introduction should vividly showcase your motivation and why you chose nursing. Set the tone early with your authorship and emotion.

Why I Want To Be A Nurse Essay Examples

Now let’s analyze some complete sample nursing personal statements for inspiration on crafting your own:

Why I Want to Be a Nurse at a Hospital: Essay

Essay on why i want to be a nurse assistant, 1000-word essay on why i want to be a nurse, essay on why i want to be a nurse, why i want to be a nurse: argumentative essay, mental health nursing personal statement, why i want to be a pediatrics nurse, why i want to be a nurse practitioner essay, writing a why i want to become a nurse essay.

To craft a standout nursing school application essay, prospective students should engage the reader with an emotional opening that illuminates their calling to the profession, whether through a compelling personal anecdote or vivid imagery expressing the profound impact of nursing.

The conclusion should be resolved by painting an inspiring vision of how the writer’s skills, values, and determination will be channeled into excellence as a nursing student and future registered nurse, making an empathetic difference in patients’ lives.

With focused, mature writing that radiates passion and preparedness, a “why I want to become a registered nurse” personal statement can stand out amidst the competition as a window into a promising applicant’s commitment to this vital healthcare profession.

Don’t wait until the last minute

Fill in your requirements and let our experts deliver your work asap.

Essay Sample on Why I Want to Be A Nurse

Nursing is a rewarding and challenging career that has the power to make a real difference in people’s lives. Whether your motivation is to help others, attain financial freedom, or both, writing a “Why I Want To Be A Nurse” essay is an excellent opportunity to express your passion and commitment to the field.

In this article, we’ll explore the reasons why you might want to become a nurse and provide you with helpful tips and inspiration for writing a powerful and persuasive essay .

Why I Want to Be A Nurse (Free Essay Sample)

Nursing is a career that offers a unique combination of hands-on care and emotional support to those in need. There are many reasons why someone might choose to become a nurse, including:

The Empathy and Altruism of Nursing

I have a strong desire to help people and hope to become a nurse. I think nursing is the best way for me to make a difference in other people’s lives because it combines my natural empathy and desire to help people. Nursing gives me a chance to positively touch people’s lives, which has always attracted me to the thought of doing so.

I saw the beneficial effects that nurses may have on people’s life as a child. I have always been moved by the kindness and concern they have for their patients. The small gestures of kindness, like holding a patient’s hand or speaking encouraging words, have always touched me. I think nurses have a special power to change people’s lives and leave a lasting impression, and I want to contribute to that.

Additionally, I think that becoming a nurse is a great and selfless job. To provide for their patients and ensure they are secure and comfortable, nurses put their own needs on hold. I absolutely respect this kind of dedication to helping others, and I aim to exhibit it in my own nursing career.

The Economic Benefits of Nursing

The financial stability that comes with being a nurse is one of the reasons I wish to pursue this career. Nursing is a field that is in high demand, which translates to a wealth of job opportunities and competitive salaries. This profession offers the chance for a stable income, which makes it a good choice for people who want to secure their financial future.

Nursing not only gives economic freedom but also a flexible work schedule that promotes a healthy work-life balance. Many nurses can choose to work part-time or in a variety of places, such as clinics, hospitals, and schools..

A Love for the Science and Art of Nursing

To succeed in the unique field of nursing, one must have both artistic talent and scientific knowledge. This mix is what initially drew me to the thought of becoming a nurse. The human body and its mechanisms have always captivated me, and I enjoy learning about the science that underpins healthcare. But nursing requires more than just a scientific knowledge of the body. It also requires an artistic understanding of the patient and their needs.. Nursing is a demanding and fulfilling job since it combines science and art, which is why I’m drawn to it.

I saw as a child the effect nurses had on patients and their families. Their compassion and understanding have motivated me to seek a profession in nursing because they frequently offer comfort and help in the hardest of situations. My enthusiasm for the science and art of nursing will undoubtedly help me to have a good influence on other people’s lives. I want to work as a nurse and improve the lives of the people I take care of, whether it be by giving medication, educating patients, or just being a reassuring presence.

Continuous Professional Development in Nursing

I think the nursing industry is dynamic and always changing, which gives people a lot of chances to learn and grow. I would have the chance to continuously advance my knowledge and abilities in this sector if I choose to become a nurse. In turn, this would enable me to better care for my patients and stay abreast of professional developments.

There are several different nursing specialties available as well. There are many options, including critical care, pediatrics, gerontology, and surgical nursing. Because of the variety of disciplines available, nurses have the chance to develop their interests and find their niche.

I am certain that a career in nursing will provide me the chance to pursue my passion for healthcare while also allowing me to grow professionally.

Nursing is a fulfilling and noble career that offers a mix of hands-on care, emotional support, and professional growth. I am inspired by the positive impact nurses have on patients and their families and aim to offer my own empathy and compassion. The nursing industry is constantly changing, providing ample opportunities for growth and job prospects with financial stability. The ultimate reward in a nursing career is the satisfaction of making a difference in people’s lives.

Tips for Writing A Compelling Why I Want To Be A Nurse Essay

Now that you understand the reasons why someone might want to become a nurse, it’s time to learn how to write a compelling essay. Here are some tips and strategies to help you get started:

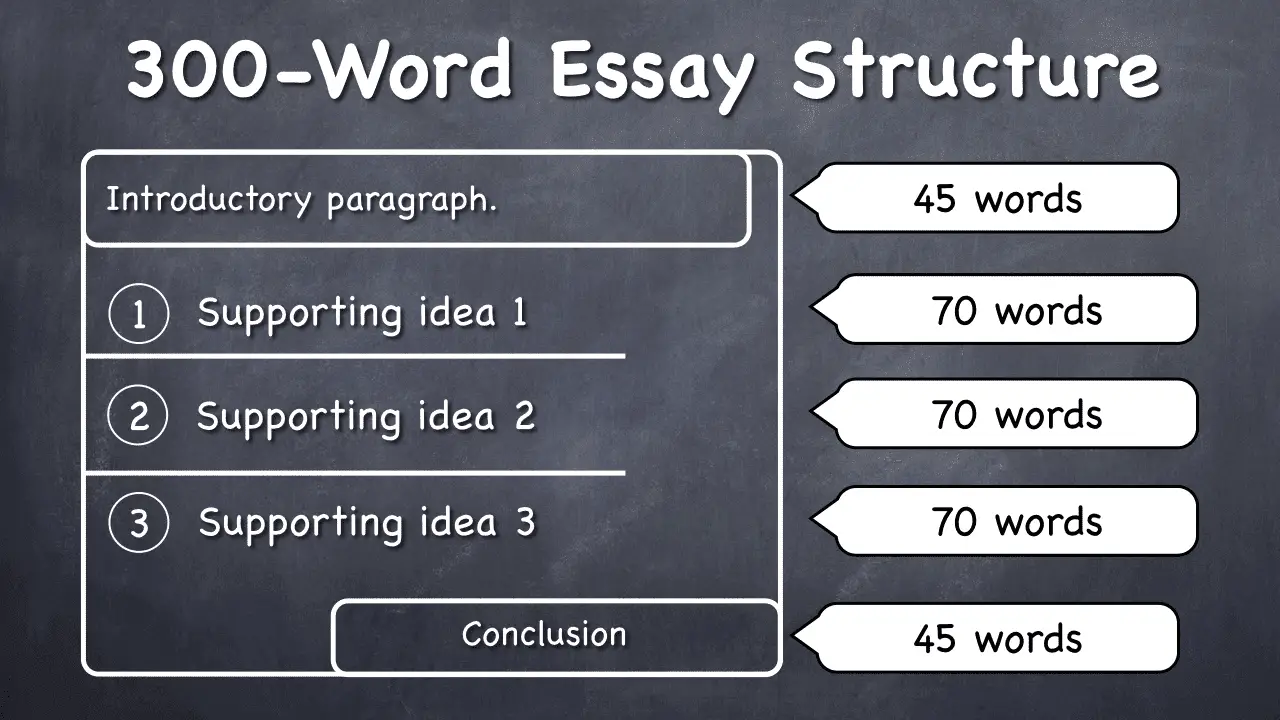

Create an Outline

Before you start writing, it’s important to identify the main points you’ll discuss in your essay. This will help you stay organized and make your essay easier to read.

Start with an Attention-grabbing Introduction

Your introduction is your chance to make a good first impression and engage the reader. Start with a hook that captures the reader’s attention, such as a surprising statistic or personal story .

Be Specific and Personal

Rather than making general statements about why you want to become a nurse, be specific and personal. Share your own experiences, motivations, and passions, and explain why nursing is the right career choice for you.

Highlight your Skills and Qualifications

Nursing is a demanding and complex profession that requires a wide range of skills and qualifications. Be sure to highlight your relevant skills, such as compassion, communication, and problem-solving, and explain how they make you a good fit for the nursing field.

Related posts:

- The Great Gatsby (Analyze this Essay Online)

- Pollution Cause and Effect Essay Sample

- Essay Sample on How Can I Be a Good American

- The Power of Imaging: Why I am Passionate about Becoming a Sonographer

Improve your writing with our guides

Youth Culture Essay Prompt and Discussion

Why Should College Athletes Be Paid, Essay Sample

Reasons Why Minimum Wage Should Be Raised Essay: Benefits for Workers, Society, and The Economy

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

find nursing schools near you

What to include: why i want to be a nurse essay.

Why do you want to be a nurse? What is your reason for entering the nursing profession? What drives you?

You will face these questions multiple times throughout your career, but there are two occasions in which answering them could actually define your career.

The first is when you apply to nursing school. You may be asked to complete an essay outlining why you want to become a nurse.

The second time is when you apply for a nursing position and answer that question as part of the interview process.

Whether you're applying for a nursing program or job, it's important to know how to address this question and what sort of answers work best.

What To Include In Your Nursing Essay

To create the perfect nursing essay, one that can help you get into nursing school or find your first job, follow the steps below:

Plan Your Nurse Essay

Before you start writing your nursing essay, think about what you want to include.

Jot down ideas that express your passion for the nursing profession, as well as any personal or familiar experience that led you to take this step.

Be honest. Be open. Summarize your story, highlight your goals, and think about what the nursing profession means to you.

All of these things will be important when structuring your essay.

Show an Emotional Connection to the Profession

Do you have any family members that worked as nurses or doctors? Did you care for a loved one during an illness? Did you require a lot of care at some point in your life?

If so, this should be your lead, and it's probably the most important part of your essay.

Nursing is a lucrative career. You can make a decent salary, enter numerous specialties, and even progress to opening your own practice. There is also a national nursing shortage, so you'll also have plenty of opportunities if you're willing to learn and work. But interviewers don't want to hear that you became a nurse to earn good money and pick up lots of overtime.

Think of it in the context of a talent show. We know that the contestants are there to get famous and make lots of money. But when they stand in front of the camera and appeal for votes, they talk about deceased parents/grandparents, changing their family's life for the better, and making a difference in the world.

It's easy to sympathize with someone who wants to follow in the footsteps of a beloved mother or make a grandparent proud. It's not as easy to sympathize with someone who just wants to drive a Bugatti and wear a Rolex.

Examples :

"My mother is a nurse practitioner. I can see how happy the role makes her and how much it has changed her. I have looked up to her throughout my life and have always wanted to follow in her footsteps."

"I cared for my father when he was ill. I was able to comfort him and assist him in his time of need, and while it was very challenging, it always felt right to me and it's something I would love to do as a career."

Show That You Care

Like all health care workers, nurses are devoted to healing the sick. If you're not a people person, it's probably not the profession for you.

Make it clear that you're a caring person and are willing to devote your life to healing sick people. A good nurse also knows how to comfort distraught family members, so you may want to include this in your essay as well.

If you have any examples of times when you have helped others, include them. This is a good time to talk about volunteer work, as well as other occasions in which you have devoted your time to helping strangers.

"I feel a great sense of pride working with families and patients through difficult times. I like to know that I am making a difference in the lives of others."

"I want to become a nurse so that I can help others in their time of need. I chose nursing as a profession because I feel a great sense of accomplishment when helping others".

Share Your Aspirations

What are your goals for your nursing career? Do you want to become a nurse practitioner? Do you want to specialize as a nurse anesthetist, a critical care nurse, or focus more on pediatrics?

Nurses work across a range of specialties, and it's important to show that you are interested in continuing your education and developing to your full potential.

The goal is to show that you are determined. You are driven to succeed and to better yourself.

If you're just taking your first steps as a nursing student, now is a good time to research into specialties and get an idea of how you want your career to progress.

"I have always been drawn to the nursing profession because it's challenging, demanding, and interesting. I want to push myself every day, engaging my academic interests and satisfying my need to learn and improve as a person."

Describe Your Nursing Skills and Qualifications

If you're applying for an accelerated nursing program or a new nursing job, the interviewer will have access to your qualifications. But they won't know what those qualifications mean to you, what you learned from them, and how you can use them in your career.

It's about problem-solving skills, as well as academic work. It's about experience and personal growth, as well as knowledge acquisition.

This is a good time to talk about internships.

How Do You Write an Introduction to a Nurse Essay?

Starting is always the hardest part, but it's best not to overthink it.

Just start writing about why you want to become a nurse. Don't overthink it. Don't worry too much about the first word or sentence. Everything can be edited, and if you spend too long thinking about those first words, you'll never finish the essay.

Keep it simple, check your work, and edit it until it's perfect and says exactly what you want it to say.

- Nursing School

“Why Do You Want to Be a Nurse?” Nursing School Interview Question

Preparing your “Why do you want to be a nurse” answer for an interview is key. The question will always be asked in a nursing school interview, which is why you must strategically plan out your answer, and take some time to reflect on this difficult question.

Not everybody puts thought into the “why” behind this question. Some people seem to act entirely on instinct, but you can’t afford to do so with your career – your future. Not to mention the fact that you need to have a professional, snappy, and thoughtful response to any (and every) question brought forward in an admissions interview.

Some nursing school interview questions are a chore to get through, but with some careful consideration, the question of why will be so foundational that you’ll never regret having explored it. This isn’t just something you have to answer, this is a question you want – even need – to answer.

In this article, you will find different answer samples to the “Why do you want to be a nurse” question, how to find a personal answer unique to you, and how to structure your answer to create an amazing impression on the interview day.

>> Want us to help you get accepted? Schedule a free strategy call here . <<

Article Contents 10 min read

Why are you asked this question.

Having an answer to this question is more than important, it’s necessary. It’s necessary for your interview, but it’s also necessary for yourself.

Imagine being the interviewer for a moment and seeing a candidate who looks great on paper, with strong academic record, a great nursing school personal statement , good letters of reference, and a demonstrable track record of excellence all-around demonstrated in their nursing school application resume . But in the interview, that candidate responds with, “I don’t know,” to the question of why they are selecting the career that they are. The interviewer’s likeliest response? Complete dismissal. If this question isn’t answered properly, it will corrupt the entire interview, and possibly even destroy the application altogether.

That’s why they ask the question. Would you select a candidate who didn’t know why they were even applying to nursing?

Of course not. If you were generous, you’d take the candidate aside and advise them to take more time to think about their future.

Which presents another reason why you need to answer the question: you owe it to yourself. This is who you want to be, after all. Make sure you put some thought into it. What the interviewer is asking of you is to not just explain why you’re a good candidate, but why nursing is important to you. So the main thing is to put your connection to the profession on display.

This question really is for the admissions committee to understand whether you fit with this career path. Your “why” will demonstrate whether you will be a positive addition to this profession.

Before you start composing your answer to this question, it’s important to reflect on your own reasons for pursuing this career. There are thousands of potential reasons and each one is legitimate in its own way. We have compiled a list of suggestions that may help you pinpoint your own “why” behind your decision.

Patient Care

One of the most common reasons that nurses give for “why nursing?” is to care for patients. Nurses spend more time with patients than any other medical professionals . They spend close to twice as long with patients as personal visitors (more than friends and family) and almost three times as many minutes with patients as other medical staff (physicians, physician assistants, and medical students).

Directly caring for patients is the biggest part of nursing, and an excellent potential aspect of your answer to the question of “why” you want to be a nurse. If you love working with patients, it could be an ideal entry into your answer to this question.

\u201cHuman connection has always been important to me. Nursing is an opportunity for me to help people at their most vulnerable.\u201d ","label":"Example statement","title":"Example statement"}]" code="tab1" template="BlogArticle">

Heat of a Team

Nurses work together as a team to care for their patients. Although each nurse is assigned certain patients, they will help each other out. Being part of a team is exciting for a lot of people, and perhaps this is one aspect of the profession that excites you. Knowing that somebody has your back, and you have theirs, is a big plus in any career.

Not just part of a nursing team, healthcare requires many specialists across disciplines, and nurses are a part of that team.

\u201cI love working with other people and knowing that I\u2019m part of a work-family. Nurses come together to share their workload in a way that I find encouraging. I would love to be the kind of person who can be counted on by my colleagues, and who has a good support network as part of the job.\u201d ","label":"Example Statement","title":"Example Statement"}]" code="tab2" template="BlogArticle">

Physically, mentally, and emotionally, nursing is a challenge. The profession demands excellence and endurance from all aspects of life. Many people find challenges exciting and rewarding, and it might be beneficial to let an interviewer see that hardworking, never-back-down side to your character.

\u201cI am someone who rises to a challenge, who doesn\u2019t quit, and who won\u2019t back down from hardship. If I fail, I try again. I know that nursing is tough, but that toughness is something I admire in others and in the profession, and I think I would be ideally suited for a place where I can be challenged. ","label":"Example Statement","title":"Example Statement"}]" code="tab3" template="BlogArticle">

Constant Learning

You’re a curious mind who loves to experience new things? Nursing is perfect.

Nursing is a multi-facetted profession, and there is always more to learn and explore. Whether travel nursing, working with children, or with the elderly, you can find something (or everything) within the field.

One of the most interesting areas to learn is in pure medical knowledge. Nurses have to deal with many different areas of medical science, so the opportunities for educational growth are exponential.

Although less altruistic than some other answers, it can be beneficial to let an interviewer know that you will love a career in nursing for these rewarding aspects as well.

\u201cLife is a journey, and an adventure, and nursing provides a place to be a kind of adventurer. There is so much this profession offers, so many different ways to learn and grow, and I look forward to a life of, not just helping people, but exploration.\u201d ","label":"Example Statement","title":"Example Statement"}]" code="tab4" template="BlogArticle">

Nursing exposes a person to a wide variety of medical experiences, and that can lead to excellent insights into the field at large and lead to other, perhaps unexpected, career paths.

There are a lot of growth opportunities within the nursing field. A nurse might strive to become a nurse practitioner – very similar to an R.N. or R.P.N., but with some powers granted and further responsibilities. They can diagnose illnesses, order tests, or give prescriptions, for example. It’s like a halfway point between nurse and doctor. If this is your ambition, do not hesitate to express that you want a career where you will be able to grow, learn, and advance as a professional!

Nurses may also explore other medical professions. While you may be hesitant to express your desire to go from nurse to doctor , you should know that these kinds of transitions are not rare. Nurses who transition to being physicians or other medical professional have a huge advantage in terms of experience and clinical knowledge! You should feel free to express your dedication and commitment to nursing, as well as your aspirations for other professional avenues. Whether you want to grow within nursing or beyond, admissions committees like applicants who show ambition.

\u201cI want to experience the medical field in its fullest, and I believe there is no better first step on that journey than nursing.\u201d ","label":"Example Statement","title":"Example Statement"}]" code="tab5" template="BlogArticle">

Want help preparing for your nursing school application and interview?

How to Plan Your Answer

All of the reasons we list above are good. But you need more than just a parroted reason. Reason without passion is just an excuse.

There is a deeper reason for entering this field. Use this question to display that depth and your passion for nursing.

The personal why is about how the profession connects with you. There was a point in your life when you knew you wanted this for yourself. Maybe a family member was a nurse? Maybe somebody you knew was hospitalized, but the nursing staff at their hospital made their recovery infinitely better. Maybe that person was you: sick or injured, your life and health, improved by the nurses who cared for you.

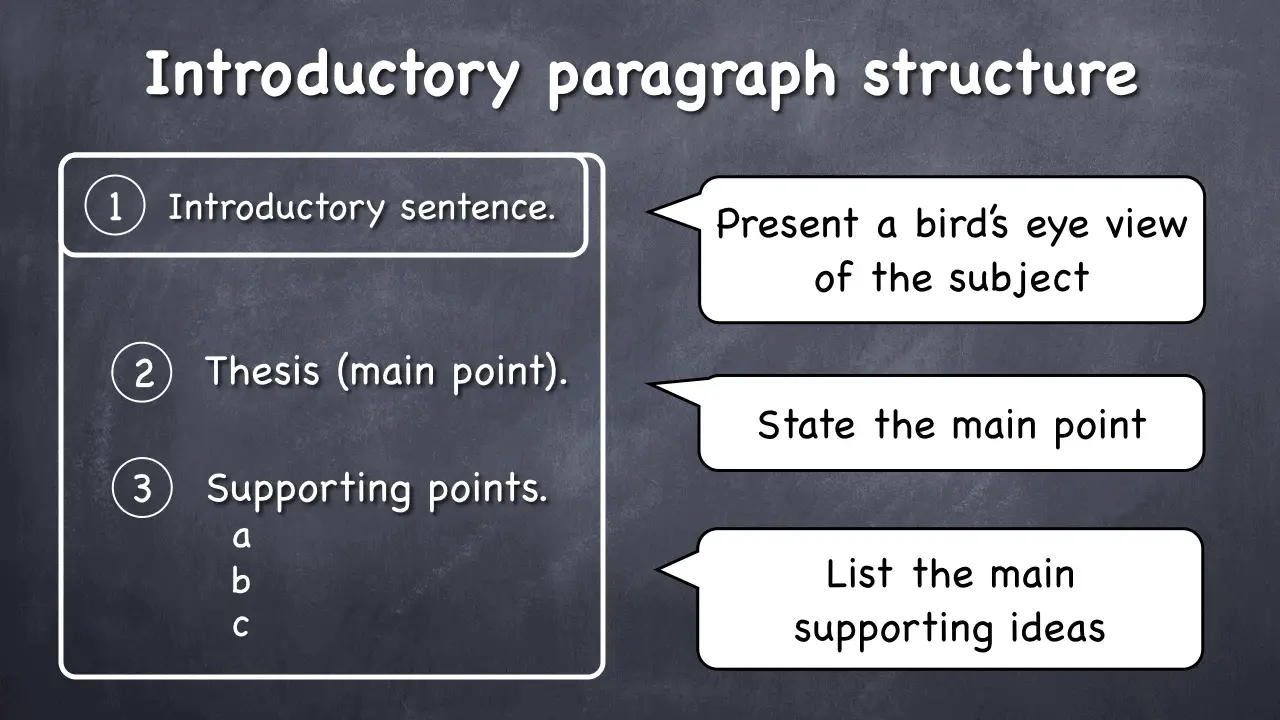

Start with a good, captivating opening statement. Make it short, to the point, and formulate it in such a way that you will set up the rest of your answer. A good attention-grabbing statement might be a cataclysmic life event, a profound quote, or a statement that generates intrigue. Think of the beginnings of your favorite books or films. They start with something that grabs attention (“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” for instance). You want to ensnare an audience, not just say, “I always wanted to be a nurse.”

For example: “We were miles from help, cell phones dead or no bars, and blood was everywhere. I was holding onto my belt, pulling it tight enough to stop the flow, talking my friend back to a state of calmness, and hoping like heck that my lack of belt wouldn’t mean my pants would fall down imminently. I didn’t know it at the time, but being the calm one in a crisis, remembering my first aid knowledge, and making it through all that trauma was what would lead me to become a nurse.”

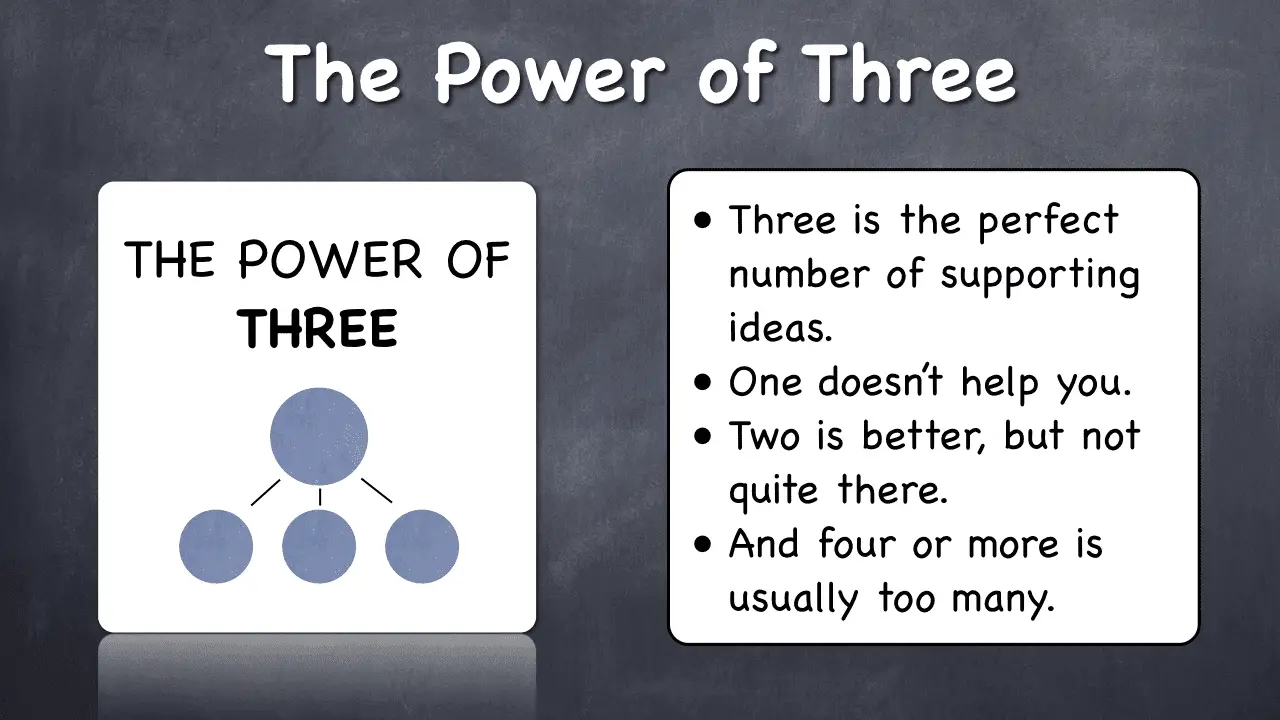

Keep to one or two main examples as to why you are pursuing nursing, show your connection to nursing beyond just, “it’s a job”, and throw in personal flair to accent your statement. Outlining one or two examples or reasons will allow you to include interesting details and expand on these reasons in more depth.

The personal connection is a good place to start. When did you realize you wanted to be a nurse? Why do you love it? Those catalyst points in your life that made you choose nursing are a great start.

A concluding statement – as short and punchy as your opening line – is the best way to wrap things up. You might let the interviewer know your career goals and how their program will help you get to where you want to go.

Make sure to keep your answer to 1 or 2 minutes long. You do not want to ramble on and on, thus losing the attention of your interviewers.

How to Practice Your “Why Do You Want to Be a Nurse?” Answer

Once you have an experience or two to focus on, spend some time thinking about how you want to present these talking points. Once you have an idea, start practicing. Remember, you do not want to memorize your answer, but you also want to have a clearly laid out format for your response. One of the worst things you can do is come to the interview unprepared, saying something like this, for example:

“I like helping people. I was once hurt and the nurses at the hospital helped me.”

That’s no good. Put effort, details, stories, and energy into the answer. This is the reason why you’re entering your next stage of life, so allow your excitement to shine through. Make a mini-story out of it.

It will help you a lot to practice your answer in mock interviews, making sure that your answer sounds natural, thorough, and professional.

“Why Do You Wat to Be a Nurse?” Sample Answer #1

“I have always needed to help people. As a kid, if my younger siblings got a scrape on the knee, I was right there with my mom, helping to bandage them up. I think I was just mostly in the way.

But that need to care and heal never went away. When I was older, I took first-aid classes and loved it. I loved learning how to help, knowing that if there was a problem I could be right there making things better.

The day that I knew specifically I wanted to be a nurse was after applying my first-aid knowledge directly. A friend of mine got hurt at school, slipped and had a bad fall down some stairs. I used my first-aid to keep them calm and check for any breaks or other issues before helping get them to the school nurse. While I was in the nurse's office, I felt like I was part of something already. Later, I spoke with the school nurse about my career path, and she was helpful, thoughtful, and encouraging.

Nursing is perfect for me. More than any other profession, nursing will give me an opportunity to care for people. It lets me do more than just give medicine, it connects me to people, and make a real difference in their lives.

That human element, making small differences day-to-day, and really helping people – all of that is deeply connected to who I am, who I want to be, and to nursing. Nursing and me are a perfect fit.”

“Nursing is a one-hundred percent career, and I am a one-hundred percent person.

Challenge is exciting to me. Rock climbing is a hobby of mine, and I love it because it’s active and requires commitment. I’ve always been passionate like that.

Another thing I’m deeply passionate about is going where I’m needed. I remember my aunt talking one time about being a nurse, and about the struggles that she and the other nurses went through. I remember her being really upset about it, but I also remember thinking, ‘Oh, they need people.’ And, as I said, I go where I’m needed.

From there I started learning as much as I could about nursing, taking elective classes in school, reading about the profession, and talking to my aunt about the job. The more I learned, the more I knew this was my path.

Nursing is a place where I can make a difference, be needed, and be challenged, and I am looking forward to all of that – one-hundred percent.”

The answer to this question is as personal as it is imperative. Really think about why you want to be a nurse above all else, and you’ll have your answer. Once you know the “why”, you might get thrashed a lot on your journey, but you will always have sight of your destination.

You also have the perfect answer for your interview. But with all that incredible insight into your life and who you want to be, that’s almost a by-product, isn’t it?

An in-depth answer, one that properly communicates your connection to nursing, is going to take up more than a couple sentences. Keep your answer to 1 or 2 minutes long.

No, and in fact, we strongly discourage memorization. Memorizing your answer comes off as disingenuous. Additionally, you run the risk of messing up your script and freezing in the middle of your answer. Instead, just focus on remembering your talking points.

Do plan out your answer carefully before your interview, practice it, but from that point on, just worry about holding the main points in your head. You don’t need to memorize the whole thing.

Everybody has a different approach to their writing processes, but one fast, fairly simple way to deal with writer’s block is to give yourself permission to take five minutes and free associate. You could use pen and paper, word processors, or record yourself talking aloud, but through whichever method you choose, just start getting out ideas about nursing and why you’re interested in it.

Another approach would be to think about the first time you considered nursing as a career and why. Those memories will give you excellent insight and a good starting place to plan your answer.

We recommend sticking to one or two events or reasons that led to your decision.

Since you don’t have time to get into every facet of every aspect of why you want to be a nurse, you’re going to want to stick to one or two primary reasons. You will weaken your statement if you have too many points.

To have a strong answer, you need to incorporate personal or professional events or experiences that led you to pursue nursing. Why did you decide to pursue this career? What interests you about it? What events took place to lead you to apply to nursing school? These events do not necessarily need to be related to nursing directly, but you can connect them to nursing. For example, maybe your volunteer or work experiences demonstrate exceptional communication and interpersonal skills? Whatever it is, make sure you can connect your passion for nursing, and your experiences in your answer.

Chronologically is probably clearest. It will let you, and the interviewer, track the story better.

Keep in mind classical story structure, with a beginning, middle, and end, and use that as a rough guide.

Just pause, take a breath, and remember the first thing your wanted to say. Since you’ll have practiced beforehand, the rest will come back to you. Since you’ve arranged your answer as a small story, the structure helps with remembering as well, and because you haven’t scripted anything, it doesn’t need to be exactly as you’ve rehearsed it.

You need to go back to your story and really look at it with a critical eye. Ask yourself if there are any details you’re including that aren’t really necessary. Try to weed it out.

What is extraneous to your story will pop out if you reconsider that story structure of beginning-middle-end. If you’ve started talking about a certain event in childhood that led to another event that led to your deciding to be a nurse, are you taking any digressions along the way? Including any anecdotes that, while nice, don’t support your main story?

If you’re having trouble sticking to two minutes, be ruthless in your editing.

Want more free tips? Subscribe to our channels for more free and useful content!

Apple Podcasts

Like our blog? Write for us ! >>

Have a question ask our admissions experts below and we'll answer your questions.

1.Why you want nursing? 2.what is customer service important

BeMo Academic Consulting

Thanks for your contribution, Rylie!

Get Started Now

Talk to one of our admissions experts

Our site uses cookies. By using our website, you agree with our cookie policy .

FREE Training Webclass:

How to improve your nursing school interview practice score by 27% , using the proven strategies they don’t want you to know.

The Nursing Blog

Why i want to be a nurse: my personal journey and motivation.

Why do I want to be a nurse? This question has been at the forefront of my mind for as long as I can remember. The desire to pursue a career in nursing has been deeply ingrained in me, stemming from a combination of personal experiences and a genuine passion for helping others.

Throughout my life, I have been inspired by the incredible work of nurses who have cared for me and my loved ones during times of illness and vulnerability. Their compassion, dedication, and ability to make a difference in the lives of others have left a lasting impression on me. I want to be a part of that impact, to provide comfort and support to patients and their families when they need it the most.

Moreover, my own journey of personal growth and development has further solidified my decision to become a nurse. I have witnessed firsthand the transformative power of healthcare professionals who not only treat physical ailments but also address the emotional and psychological needs of patients. This holistic approach to care resonates with me deeply, and I am motivated to contribute to the well-being of individuals in a comprehensive and meaningful way.

Early Inspirations

Early on in my life, I was fortunate enough to witness the incredible impact that nurses had on the lives of those around me. It was through these experiences that my interest in nursing was sparked and my passion for helping others was ignited.

One of my earliest inspirations came from my grandmother who was a nurse. I remember listening to her stories about the lives she touched and the difference she made in the lives of her patients. Her dedication and compassion left a lasting impression on me, and I knew from a young age that I wanted to follow in her footsteps.

Additionally, I had the opportunity to volunteer at a local hospital during my high school years. This experience allowed me to witness firsthand the incredible strength and resilience of patients, as well as the compassion and skill of the nurses who cared for them. Seeing the impact that nurses had on the lives of these individuals further solidified my desire to pursue a career in nursing.

Overcoming Challenges

On the journey to becoming a nurse, I have encountered numerous challenges that have tested my determination and resilience. From the demanding coursework to the emotional toll of working with patients in difficult situations, each obstacle has presented an opportunity for growth and learning.

One of the major challenges I faced was balancing my academic pursuits with my personal responsibilities. As a full-time student, I had to juggle coursework, clinical rotations, and part-time work to support myself financially. It required careful time management and sacrifice, but I remained committed to my goal of becoming a nurse.

Additionally, the emotional challenges of working with patients in distressing situations can be overwhelming. Witnessing the pain and suffering of others can take a toll on one’s mental well-being. However, I have learned to cope with these challenges by seeking support from my colleagues, practicing self-care, and reminding myself of the positive impact I can make in the lives of patients.

Through perseverance and determination, I have overcome these challenges and emerged stronger and more resilient. Each obstacle has reinforced my passion for nursing and my commitment to providing compassionate care to those in need. I am confident that these experiences have prepared me to face any future challenges that may come my way as a nurse.

Academic Pursuits

When it comes to pursuing a career in nursing, education plays a crucial role in shaping one’s path. For me, the journey towards becoming a nurse has been filled with both challenges and rewards.

My academic pursuits began with enrolling in a reputable nursing program, where I gained a solid foundation of knowledge and skills. However, the road to success was not without its obstacles. The rigorous coursework and demanding clinical rotations tested my resilience and dedication. Yet, with each challenge I faced, I grew stronger and more determined to achieve my goals.

One of the most rewarding aspects of my academic journey has been the opportunity to learn from experienced nursing professionals. Through hands-on training and mentorship, I have gained invaluable insights into the complexities of patient care and the importance of compassionate communication.

In addition to classroom learning, I have also engaged in extracurricular activities and participated in research projects to expand my knowledge and contribute to the field of nursing. These experiences have not only enhanced my academic growth but also allowed me to explore different areas of healthcare and develop a well-rounded perspective.

In conclusion, my academic pursuits in nursing have been challenging yet immensely rewarding. The knowledge and skills I have gained, combined with my passion for patient care, have solidified my commitment to this noble profession. I am excited to continue my educational journey and contribute to the healthcare field in meaningful ways.

Personal Growth and Development

Personal growth and development have played a significant role in shaping my decision to become a nurse and have had a profound impact on my approach to patient care. Throughout my life, I have encountered various experiences that have shaped my understanding of empathy, compassion, and the importance of providing holistic care to individuals in need.

One of the key personal experiences that influenced my decision to pursue a career in nursing was witnessing the care and support provided by nurses during a family member’s illness. Their dedication, kindness, and ability to make a difference in someone’s life left a lasting impression on me. It made me realize the immense impact that nurses have on patients and their families, and I knew I wanted to be a part of that impactful profession.

Furthermore, my personal growth journey has taught me the value of resilience, adaptability, and continuous learning. These qualities have not only helped me overcome personal challenges but have also prepared me to face the demands of the nursing profession. I believe that personal growth is an ongoing process, and as a nurse, I am committed to continually developing my skills, knowledge, and understanding of patient care to provide the best possible outcomes for those under my care.

Financial Considerations

When considering a career in nursing, it is important to address the financial considerations that come along with pursuing this profession. While the rewards of being a nurse are immeasurable, it is essential to understand the potential costs and sacrifices involved.

One of the main financial considerations is the cost of education. Nursing programs can be expensive, requiring tuition fees, textbooks, and other educational materials. Additionally, students may need to invest in uniforms, clinical equipment, and licensing exams. It is important to carefully plan and budget for these expenses to ensure a smooth educational journey.

Furthermore, pursuing a nursing career often requires sacrifices in terms of time and income. Nursing programs can be rigorous and demanding, requiring students to dedicate a significant amount of time to their studies and clinical rotations. This may result in reduced work hours or even the need to quit a job temporarily, impacting one’s income.

Despite these financial considerations, many individuals find that the personal and professional rewards of a nursing career far outweigh the costs. The opportunity to make a difference in the lives of patients and their families, the potential for career growth and advancement, and the job security that comes with being a nurse are all factors that make the financial sacrifices worthwhile.

Passion for Patient Care

As an aspiring nurse, my deep-seated passion lies in providing compassionate and quality care to patients. I believe that every individual deserves to be treated with dignity and respect, especially during their most vulnerable moments. The impact I hope to make in my nursing career is to be a source of comfort and support for patients and their families.

I firmly believe that patient care goes beyond just administering medications or performing medical procedures. It is about building meaningful connections with patients, listening to their concerns, and understanding their unique needs. By taking the time to truly connect with patients on a personal level, I aim to create a safe and trusting environment where they feel valued and cared for.

To ensure that I am able to provide the highest level of care, I am committed to continuously improving my knowledge and skills. I plan to stay updated with the latest advancements in healthcare and participate in professional development opportunities. By staying informed and continuously learning, I can adapt to the ever-changing healthcare landscape and provide the best possible care to my patients.

Future Goals

As a passionate and driven individual, my aspirations and long-term goals as a nurse extend far beyond the boundaries of the present. I envision myself not only providing exceptional patient care but also specializing in a particular area of healthcare that aligns with my interests and expertise.

One of my primary goals is to become a specialist in pediatric nursing. I have always had a natural affinity for working with children, and I believe that by focusing on this specific area, I can make a significant impact on the lives of young patients and their families. The joy and satisfaction of helping children overcome health challenges and witnessing their resilience is immeasurable.

In addition to specializing in pediatric nursing, I am also passionate about contributing to healthcare policy and advocacy. I believe that by actively participating in shaping healthcare policies, I can advocate for improved patient outcomes and access to quality care for all individuals. Whether it’s through research, community engagement, or collaboration with policymakers, I am determined to make a difference on a broader scale.

Continued Learning and Growth

The author’s commitment to lifelong learning and professional development in the nursing field is unwavering. They understand the importance of staying updated with the latest advancements and best practices in healthcare. To achieve this, they have plans to pursue advanced certifications and degrees that will enhance their knowledge and skills.

One of the author’s goals is to specialize in a specific area of healthcare. They believe that by gaining expertise in a particular field, they can provide even better care to their patients. Whether it’s becoming a nurse practitioner, a nurse educator, or a nurse researcher, they are determined to expand their horizons and contribute to the advancement of nursing as a whole.

In addition to formal education, the author also recognizes the value of continuous learning through professional development programs, workshops, and conferences. They understand that staying engaged in the nursing community and networking with other professionals can provide valuable insights and opportunities for growth.

Ultimately, the author’s commitment to continued learning and growth is driven by their desire to provide the highest quality of care to their patients. They believe that by staying current and expanding their knowledge, they can make a significant impact on the lives of those they serve.

Making a Difference

Making a difference in the lives of patients and their families is at the core of my desire to become a nurse. I am driven by the opportunity to provide comfort and support during challenging times, and to make a meaningful impact on those who are in need of care.

As a nurse, I believe in the power of compassion and empathy. I understand that patients and their families are often facing difficult situations, whether it be a serious illness, a life-changing diagnosis, or a challenging recovery process. I want to be there for them, to offer a listening ear, a comforting touch, and a sense of reassurance that they are not alone.

Through my nursing career, I hope to bring a sense of calm and understanding to those I care for. I want to be a source of support, not only for the physical needs of patients, but also for their emotional and mental well-being. I aim to create a safe and nurturing environment where patients feel heard, valued, and respected.

By being able to make a difference in the lives of patients and their families, I believe that I can truly contribute to the healing process. It is a privilege to be able to provide comfort and support during challenging times, and I am committed to doing so with compassion, dedication, and a genuine desire to make a positive impact.

- ← What Is an Aesthetic Nurse? A Comprehensive Guide

- Binge-Worthy: How Many Episodes of The Nurse are on Netflix? →

Marlene J. Shockley

My name is Marlene J. Shockley, and I am a Registered Nurse (RN). I have always been interested in helping people and Nursing seemed like the perfect career for me. After completing my Nursing Degree, I worked in a variety of settings, including hospitals, clinics, and home health care. I have also had the opportunity to work as a Travelling Nurse, which has allowed me to see different parts of the country and meet new people. No matter where I am working, I enjoy getting to know my patients and their families and helping them through whatever medical challenges they may be facing.

You May Also Like

Unlocking success: a nurse practitioner’s guide to opening a medical spa, how to become a pediatric nurse: a step-by-step guide, why do nurses think they know everything.

- December 27, 2022

How to Write: Why I Want to Be a Nurse Essay

The Why I Want to Be a Nurse essay is one of the most common components on nursing school applications. There are tons of reasons to become a nurse, but yours are unique – a good nursing essay will stand out and be remembered by those who read it. In addition to general admission, this could even be your ticket to some scholarships for nursing school!

Let’s dive into how to write your Why I Want to Be a Nurse essay and get you into nursing school!

Planning Your Nursing Essay

Before you get into writing anything, you should always complete your pre-writing phase of brainstorming and planning for what you want to write about. Only then can you start considering your structure and details that you want to include.

Step 1: Brainstorm an event or a list of moments that began your interest in nursing.

If this is a lifelong dream, then maybe you can’t remember when you first became interested in nursing. But what moments have helped you continue down this path?

Some people may not have a specific healthcare related experience that inspired them to take this path. That’s okay! You can think broadly and consider times you were satisfied by helping someone with a task or volunteered.

Haven’t taken a writing class in a hot minute? Here are some effective strategies for brainstorming your ideas.

Step 2: Consider what you did to learn more about nursing.

Think about when you began researching nursing as a viable career option. What made nursing more appealing than a different career?

Step 3: Write down what made you decide to choose nursing as a career path.

If you can boil your reasoning down to a sentence or two, then that will be the thesis for your Why I Chose Nursing essay.

What to Include: Why I Want to Be a Nurse Essay

Introduction: your hook and story.

Your test scores and transcripts tell the story of your technical aptitude. But your essay is an opportunity to give your application an emotional route. What experiences have made you passionate about nursing? Have you cared for sick loved ones before? Are there nurses in your family?

Your introduction is where you’ll explain the stake that you have in this. You want the admissions team to understand that you belong in the program. Not just that you have the academic qualifications, but that you’ll be an asset to the entire nursing profession.

In kindergarten, there was an accident while my family was camping. A pot of boiling water tipped over onto my leg. The burns were so bad that I had to be airlifted to a regional hospital. I don’t remember much of the incident itself today, but I remember the nurses who helped me recover. They turned a frightening experience into something much kinder. I want to be able to give that to a child by working as a pediatric nurse.

Paragraph 1: Detail the event or moment you became interested in nursing.

This is a paragraph where you really want to reel the reader in. You’ve hooked them with the broad overview of your story: what sets you apart, why you’re so interested in the nursing profession. Now you can detail a specific moment.

Pick one moment and capture it in as much detail as you can. For example, maybe you remember waiting in a hospital for news about a loved one. Perhaps it was the kindness of a nurse who treated you. Or, in contrast, it was a time that a nurse wasn’t kind, and it made you want to do better for a patient in need.

Despite spending several weeks in the hospital, I didn’t immediately develop a desire to become a nurse. Growing up, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life. Then in my sophomore year of high school, my neighbor’s son got sick. He was about the same age as I had been when I was in the hospital. When I babysat him, we would swap hospital stories — the good and the bad! And suddenly it dawned on me that if I was a nurse, I could help make those bad stories a little less painful.

Paragraph 2-3: Show how you have used that experience to build your foundation towards nursing school.

Here is where you’ll take your personal experiences into account. Nursing school requires more than just empathy. You will need to have core science credits and an ability to understand the human body. The best nurses are adaptable in the workplace and always willing to learn. You can browse a list of skills nurses need to thrive in the workplace.

I spent a lot of time researching my neighbor’s son’s condition. Though his illness wasn’t terminal, it was degenerative. He began to lose his hearing a few months after his diagnosis. I joined his father in learning sign language to communicate better. During that time period, I spent a lot of time thinking about how so many people have to struggle so hard to communicate.

I want to be a nurse who can give relief to the most vulnerable patients. Every person’s needs are different. A child’s needs are different from a developmentally disabled adult’s, which are different from the needs of someone hard of hearing, and so forth. I’ve seen firsthand the frustration that occurs when communication isn’t easy. So I’ve focused on learning adaptable communication methods and educating myself about the groups that are most overlooked in hospital settings.

Paragraphs 4-5: Detail how you will use your strengths and skills in your nursing career.

This is the point at which you can start to talk about your specific skills, similar to a job interview. You want to highlight any particularly unique aspects, then make sure to solidly establish your core competency. A dream of becoming a nurse can’t just be a dream; you need detail to back it up.

If you know where you want to place your specific focus as a nurse, mention it! Talk about your career goals and how you want to work with your patients and what you hope to learn in doing so.