Exploring what works, what doesn’t, and why.

Standout voices in African public health

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share through Email

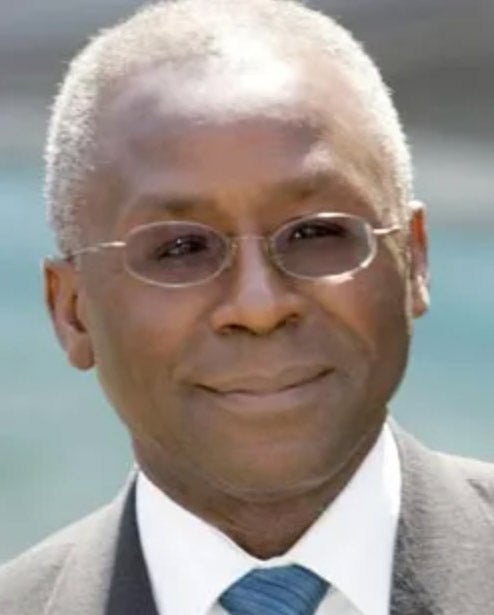

These are some of the notables making a new path for the field. They represent an increasingly deep bench of leaders shaping policy and practice on the continent.

Quarraisha Abdool Karim

Notable for: Developing HIV prevention solutions for women. Led South Africa’s first community-based HIV prevalence study in 1990, discovering disproportionately high rates of infection among adolescent girls. Helped establish and is associate scientific director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA). Developed several woman-controlled HIV prevention methods, including vaginal microbicides. Co-chairs a UN expert group advising governments on using science and technology for sustainable development. Is a professor of epidemiology at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health . — Linda Nordling

Salim Abdool Karim

Notable for: Prevention and treatment of HIV and tuberculosis. Karim’s clinical research revealed that antiretrovirals can prevent sexually transmitted HIV infection and genital herpes in women. Co-invented patents used in HIV vaccine candidates. Leads the South African Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19. Chairs the UNAIDS Scientific Expert Panel and WHO’s HIV Strategic and Technical Advisory Committee , and is a member of the WHO TB-HIV Task Force. — Gilbert Nakweya

Akinwumi A. Adesina

Notable for: Boosting food security. As Nigeria’s minister of agriculture and rural development, leveraged mobile phones to increase access to improved seeds and fertilizers for 15 million farmers, boosting food production by 21 million metric tons. Rooted out corruption in Nigeria’s agriculture sector, prompting Forbes Africa magazine to name him its Person of the Year in 2013. An economist, he is currently in his second term as president of the African Development Bank Group . — Esther Nakkazi

Agnes Binagwaho

Notable for: Global health equity and social justice. Vice chancellor and co-founder of Rwanda’s University of Global Health Equity , an initiative of Partners In Health . UGHE aims to refocus health education on expanding access to services. As Rwanda’s minister of health became known for #MinisterMondays, regular Twitter discussions on global health policy. — Esther Nakkazi

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

- Email address By clicking “Subscribe,” you agree to receive email communications from Harvard Public Health.

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Winnie Byanyima

Notable for: Expanding access to health services. As UNAIDS executive director , drives attention to the public health impacts of social justice and gender equality. Works to remove barriers to health services for women and vulnerable groups through the elimination of discriminatory laws. Has expanded HIV/AIDS prevention, testing, and treatment services to key populations. — Paul Adepoju

Kelly Chibale

Notable for: Drug discovery in Africa. In 2010, Zambia-born Chibale founded his drug discovery and development center H3D at the University of Cape Town , where his team developed antimalarial drugs now in early-phase human clinical trials – a first for an African drug discovery team . Works to optimize medicines for African populations, by studying how their livers digest common drugs. Also collaborates with industry to create jobs for young African scientists. — Linda Nordling

Mohammed Malick Fall

Notable for: Response to COVID-19. As UNICEF regional director for Eastern and Southern Africa , the native of Senegal led a large team to coordinate responses to COVID-19 across the continent. Worked with countries and other partners to procure, mobilize, and distribute vaccine doses and other tools to fend off the pandemic. Has been involved in UN initiatives in Afghanistan, France, Haiti, Indonesia, Mongolia, and Switzerland. —Paul Adepoju

Temie Giwa-Tubosun

Notable fo r : Supply chain logistics. Nigerian entrepreneur who founded LifeBank , a healthcare technology and logistics company that started with improving access to blood units for transfusion services in Nigeria and beyond. Has since expanded into medical oxygen access for patients. She works to develop and spread technologies that can be used to predict need for health commodities to create more efficient supply chains. — Paul Adepoju

Christian Happi

The professor of molecular biology and genomics at Nigeria’s Redeemer’s University leads a center crucial for pathogen genomic surveillance in Africa. It serves as a reference laboratory for the WHO and Africa CDC. Produced the continent’s first genomic sequence for COVID-19. Also helps other African countries with sequencing, research, and more. —Paul Adepoju

Catherine Kyobutungi

Notable for: Health care systems research and capacity building. Worked as a medical officer in rural Uganda and as a lecturer at Mbarara University of Science and Technology. A 2019 Joep Lange Chair at the University of Amsterdam where she investigates chronic disease management in Africa. Co-directs the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa which trains early-career researchers at PhD and post-doctoral level, and heads the African Population and Health Research Center. — Gilbert Nakweya

Zaakira Mahomed

Notable for: Menstrual hygiene and sanitation. South African businesswoman, social entrepreneur, and activist. Started the Mina Foundation to develop a sustainable, healthy, and eco-friendly alternative to current methods of period care. Mina menstrual cups have been distributed to more than 70,000 women through partnerships in six countries in Africa and the Middle East. Works to normalize menstruation promote period positivity and keep young women and girls in school during their periods. — Esther Nakkazi

Julie Makani

Notable for: Genomic research, advocacy, and awareness for sickle cell disease in Africa. Established the world’s largest study center for sickle cell disease at Tanzania’s Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences . Founded the Sickle Cell Foundation of Tanzania to raise awareness of the disease. Makani is the principal investigator for the Sickle Pan African Research Consortium under the Sickle In Africa network. — Gilbert Nakweya

Mamello Makhele

Notable for: Improving access to maternal health for women in rural areas. Registered nurse-midwife based in Lesotho. During the pandemic traveled by donkey and on foot into rural Lesotho to bring maternal care services, healthcare, and contraceptives. Named a Bill Gates’ Heroes in the Field . A Shedecides leader for Lesotho, educating young people on child marriages, consent, and teenage pregnancy. Board member of Safe Abortion Action Fund in London. — Esther Nakkazi

Strive Masiyiwa

Notable for: Increasing vaccine access. Zimbabwean billionaire businessman and philanthropist was engaged to lead the African Union ‘s African Vaccine Acquisition Trust. Actively highlighted the vaccine inequity that plagued the early months of COVID-19 vaccination rollout. Led discussions and negotiations that resulted in the availability of vaccine doses from several sources, including the fill-and-finish agreement bringing the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine to Africa. — Paul Adepoju

Matshidiso Moeti

Notable for: Reducing inequity. First female World Health Organization regional director for Africa . Marshaled global health actions by providing direction, leadership, and access to support for health ministries across Africa. Brought attention to health inequities and coordinated WHO response to COVID outbreaks across the continent through measures such as helping Somalia acquire medical oxygen infrastructure. Working to help African countries prepare for future pandemics. — Paul Adepoju

Jean-Jacques Muyembe

Notable for: The discovery of Ebola virus disease. The Congolese microbiologist leads public health emergency responses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including for COVID-19. He led the design of Ebola treatment and pioneered the deployment of experimental Ebola vaccines. Heads the DRC’s Institut National de la Recherche Biomédicale , a significant contributor to global knowledge of infectious diseases. — Paul Adepoju

Wilfred Ndifon

Notable for: Research on the immune system. Discovered a mechanism for T-cell generation, showed how influenza interferes with the immune system’s antibodies, and proposed an explanation for the idea of original antigenic sin , a well-known phenomenon in immunologic response systems. The Cameroonian virologist’s work could lead to the development of ‘zero-interference’ vaccines, expected to improve immune response. Currently chief scientific officer of the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences Global Network. — Esther Nakkazi

John N. Nkengasong

Notable for: Public health leadership. Cameroonian virologist was the first head of the Africa CDC and helped build frameworks for stronger health systems across Africa, emphasizing cross-border collaboration, capacity building, and resource mobilization. Led the African Union’s public health agency in responding to Ebola, Lassa fever, and COVID-19. First African to head PEPFAR , the U.S’s global effort to combat HIV/AIDS. —Paul Adepoju

Muhammad Pate

Notable for: Healthcare systems innovation and reform. In Nigeria, galvanized efforts to reduce polio and drove innovation across the country’s health sector, including launching the Midwives’ Service Scheme to help reduce maternal and childhood mortality. At the World Bank , Pate initiated a $100 million private-public partnership in Lesotho to build a new national referral hospital, completed in 2011. This was one of the first such development effort s in the health care sector in Africa. Co-chairs a Lancet commission aiming to improve global health systems and teaches at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health . — Michael Fitzgerald

Notable for: Translating health research into policy and practice. An anti-apartheid activist doctor, she has led the Reproductive Health and HIV Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg since 1994. Has served on a multitude of global health advisory bodies and committees on vaccines. Advises the South African government on Covid variants and vaccines. Co-leads South Africa’s arm on the WHO’s COVID-19 Solidarity Therapeutics Trial . Chairs the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority and fought vaccine disinformation during the pandemic. — Linda Nordling

David Moinina Sengeh

Notable for: Policy innovation. Being Chief Innovation Officer for Sierra Leone and also its minister for basic and secondary education does not sound like a public health job. But Sengeh and his team at the Directorate of Science, Technology, and Innovation became the fulcrum for the country’s fight against COVID-19, providing data and analysis to shape emergency response, lockdown policies, and school closings and reopenings. It also developed tools to share information with the populace, such as the Moi Minute, public health messages Sengeh recorded that were on Youtube and TV. — Michael Fitzgerald

Flavia Senkubuge

Notable for: Academic leadership. First Black female president and youngest ever (at age 39) of the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa , only the third woman president in its 66 years. CMSA sets the country’s standards for medical and dental education and care. She is deputy dean of health stakeholder relations at the University of Pretoria , Faculty of Health Sciences. Chairs the WHO/Afro African Advisory Committee on Research and Development ( AACHRD ). — Esther Nakkazi

Michel Sidibé

Notable for: Rallying support for the African Medicines Agency, established to coordinate pan-African regulatory structures and standards. Left position as Mali’s minister of health and social affairs to become African Union special envoy, lobbying governments to sign and ratify the AMA treaty . Helped establish the AMA. Had been the second executive director of UNAIDS . — Paul Adepoju

Oyewale Tomori

Notable for: Researching viruses. Established the African Regional Polio Laboratory Network, helping nearly eradicate poliovirus infections. Has studied Ebola, Lassa fever, Yellow fever, and Chikungunya, a virus that causes joints to swell. The Nigerian virologist, who also holds a DVM in veterinary medicine, isolated the properties of the Orungo arbovirus, which can cause encephalitis. — Esther Nakkazi

Notable for: Vaccine manufacturing. Spearheading Egypt’s private sector COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing initiative. Leads Egypt’s largest vaccine production facility, which has produced tens of millions of doses of the Sinovac vaccine. Plays a key role in helping the continent fulfill its goal of producing 60% of its own vaccines by 2040, developing vaccine production partnerships and transfer of vaccine manufacturing technology in other parts of Africa. — Paul Adepoju

This story has been updated to clarify Quarraisha Abdool Karim’s role in developing HIV prevention methods.

Contributors: Paul Adepoju is a Nigerian science journalist. Esther Nakkazi is a Ugandan science journalist and blogger. Gilbert Nakweya is a Kenyan science journalist. Linda Nordling is a science journalist based in South Africa. Michael Fitzgerald is Editor-in-Chief of Harvard Public Health.

Photos: Quarraisha Abdool Karim: Rajesh Jantilal; Salim Abdool Karim: Dean Demos, CAPRISA; Adesina: AfDB; Binagwaho: Courtesy of Agnes Binagwaho; Chibale: University of Capetown; Giwa-Tubosun: Courtesy of Temie Giwa-Tubosun; Happi, Moeti, Muyembe, and Nkengasong: Paul Adepoju; Kyobutungi: Florence Sipalla, APHRC; Mahomed: Courtesy of Zaakira Mahomed; Makhele: Lee-Ann Olwage; Masiyiwa: Gus Ruelas / Rueters; Ndifon: AIMS; Pate: Harvard Chan School; Rees: Wits University; Senkubuge: Courtesy of Flavia Senkubuge; Tomori: Courtesy of Oyewale Tomori.

Spring 2022

More in global health.

Cambodia’s new path for prosthetic care

How public health officials keep hope alive in Sudan’s civil war

How a deadly global crisis went unseen

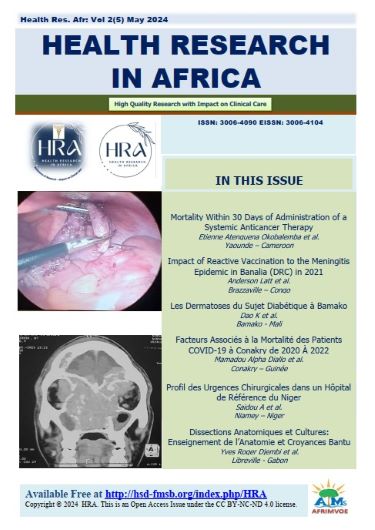

HEALTH RESEARCH IN AFRICA

About the journal.

Health Research in Afr ica (HRA) is an open access, peer reviewed medical journal that is affiliated to Health Sciences and Disease . HRA values high quality research with impact on clinical care in order to improve human health in Africa. HRA covers all aspects of medicine, pharmacy, biomedical and health sciences, including public health and societal issues. Like HSD, it is an “online first” publication, which means that all the publications articles appear on the website before being included in the print journal. The papers are published in full on the website, with open access. Acceptance of manuscripts is based on the originality, the quality of the work and validity of the evidence, the clarity of presentation, and the relevance to our readership. Publications are expected to be concise, well organized and clearly written. Authors submit a manuscript with the understanding that the manuscript (or its essential substance) has not been published other than as an abstract in any language or format and is not currently submitted elsewhere for print or electronic publication. HRA is published by Afrimvoe Medical Services , Yaounde (Cameroon).

Current Issue

Front Cover Page

Please download the front cover page here, in this issue, please, download the full contents page here, about health research in africa, a few facts about your journal, research articles, mortality within 30 days of administration of a systemic anticancer therapy in a medical oncology unit of yaounde mortalité dans les 30 jours suivant l'administration d'une thérapie anticancéreuse systémique dans une unité d'oncologie médicale à yaoundé, determinants of the non-use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets in benin déterminants de la non-utilisation des moustiquaires imprégnées d'insecticide au bénin, knowledge, attitudes and practices related to blood donation among the population of kribi connaissances, attitudes et pratiques liées au don de sang des populations de kribi, iron overload in living children with major sickle cell syndrome la surcharge en fer chez les enfants vivant avec un syndrome drépanocytaire majeur, impact of reactive vaccination on the 2021 meningitis epidemic in banalia impact de la vaccination réactive sur l'epidémie de méningite de 2021 à banalia, serum creatinine as a predictive tool of adverse outcomes in covid-19 patients in douala créatinine sérique comme outil prédictif des résultats défavorables chez les patients atteints de covid-19 à douala., prevalence and characterization of adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors in brazzaville, congo prévalence et caractérisation des effets indésirables des inhibiteurs de la pompe à protons à brazzaville au congo., prevalence of gastrointestinal toxicity in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy at douala general hospital prévalence de la toxicité gastro-intestinale chez les patients recevant une chimiothérapie à base de platine à l'hôpital général de douala, evaluation of oxidative stress by plasma measurement of oxidized ldl in type 2 diabetics in mali évaluation du stress oxydatif par le dosage plasmatique des ldl oxydées chez les diabétiques de type 2 au mali, medicine and surgery in the tropics, skin diseases of diabetic patients in mali: prevalence and clinical presentation les dermatoses chez les patients diabétiques au mali : prévalence et aspects cliniques, epidemioclinical pattern of glenohumeral dislocations at owendo university hospital profil épidémioclinique des luxations gléno-humérales au chu d’owendo, outcome of surgical treatment of adult’s olecranon fracture in yaoundé résultat du traitement chirurgical de la fracture de l'olécrane de l'adulte à yaoundé, insulin therapy of diabetic patients at hopital du mali from 2016 to 2017 l’insulinothérapie chez les patients diabétiques à l’hôpital du mali de 2016 à 2017, spectrum of surgical emergencies in a national reference hospital of niger profil des urgences chirurgicales dans un hôpital de référence national du niger, medical secrecy in the context of the response against the covid-19 health crisis in cameroon: analysis from the united#covid-19 le secret médical dans le contexte de la réponse à la crise sanitaire du covid-19 au cameroun : analyse de united#covid-19, functional results and patient satisfaction after cataract surgery by phacoemulsification in gabon résultats fonctionnels et satisfaction des patients après chirurgie de la cataracte par phacoémulsification au gabon, clinical, paraclinical, therapeutic and evolutionary aspects of gout in brazzaville aspects cliniques, paracliniques, thérapeutiques et evolutifs de la goutte à brazzaville, factors associated with mortality of covid-19 patients hospitalized in conakry from 2020 to 2022 facteurs associés à la mortalité des patients covid-19 hospitalisés à conakry de 2020 à 2022, anatomical dissections and cultures: the teaching of anatomy and bantu beliefs dissections anatomiques et cultures: enseignement de l’anatomie et croyances bantu, case reports, inverted papilloma of right maxillary sinus with subdural and orbital extension : a case report inverted papilloma of right maxillary sinus with subdural and orbital extension : a case report, pheochromocytoma and neuromalaria: a disturbing morbid association pheochromocytome et neuro-paludisme: une association pathologique déroutante, an unexpected dystocia after head delivery, linked to a large sacrococcygeal teratoma in a situation of limited resources and insecurity due to terrorist armed groups in burkina faso dystocie après accouchement de la tête liée à un volumineux tératome sacrococcygien en situation de ressources limitées et d’insécurité liée aux groupes armés terroristes, author guidelines, please, download the guidelines for authors here, and read carefully before submitting.

Endorsed by

The University of Yaounde 1

Our Partners

Make a submission, follow us on social media.

HRA on facebook

Useful links

Conseil Africain et Malgache pour l'Enseignement Supérieur (CAMES)

Faculté de Médecine et des Sciences Biomédicales (UYI)

Afrimvoe Medical Services

African Union

Ministry of Higher Education

Ministry of Public Health

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

EDITORIAL POLICIES

EDITORIAL POLICIES, ETHICS AND PEER REVIEWING

HRA’s Publications Policy Committee follows the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE ), the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) , and the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) for guidance on policies and procedures related to publication ethics. The policies for HRA have been adapted from those three advisory bodies and, where necessary, modified and tailored to meet the specific content, audiences, and aims of HRA. Review process

Research manuscripts are initially checked by the editor in chief or section editor for identification of gross deficiencies. At this stage, the proposal may be rejected. After this initial screening, articles are sent to one or two-reviewers whose names are hidden from the author and whose review is guided by a checklist (single anonymized review). The review summary is signed by the reviewer and is not posted with article. The review process may take days to weeks to reach a final decision that is the responsibility of the editor in chief. The duration from submission to publication may take one to six months (average: 6 months). So, the authors should avoid contacting the editorial office less than 6 weeks after the initial submission. Plagiarism, Scientific Misconduct Manuscripts proven of plagiarism will be returned to the authors without peer review. The editors reserve the right to request that the authors provide additional data collected during their investigations. The editors also reserve the right to send a copy of the manuscript and data in question to the author’s dean, university, or supervisor or, in the case of an investigation being funded by an agency, to that funding agency for appreciation. Conflict of Interest At the time of submission, authors are asked to disclose whether they have any financial interests or connections, direct or indirect, or other situations that may influence directly or indirectly the work submitted for consideration. Human and Animal Studies Manuscripts reporting results of prospective or retrospective studies involving human subjects must document that appropriate institutional review board (IRB) approval and informed consent were obtained (or waived by the IRB) after the nature of the procedure(s) had been fully explained. Authorship To be listed as an author, an individual must have made substantial contributions to all three categories established by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE ) : (a) “conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data,” (b) “drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content,” and (c) “final approval of the version to be published.” Individuals who have not made substantial contributions in all three categories but who have made substantial contributions either to some of them or in other areas should be listed in acknowledgments. Please limit the number of authors to ten when this is feasible.

Content licensing - Open access compliance - Copyright Since its creation, articles published in HRA are Open Access and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Non-Commercial No-Derivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) The authors publishing under this license with HRA retain all rights which means that the authors can read, print, and download, redistribute or republish (eg, display in a repository), translate the article (for private use only, not for distribution), download for text and data mining, reuse portions or extracts in other works, but they are not allowed to sell or re-use for commercial purposes or re-use for non-commercial purposes; without asking prior permission from the publisher, provided the original work is properly cited. Language HRA accepts publications in English and French . All the publications should have an abstract in both languages. Whenever possible, picture captions and table titles should be in both languages. All accepted manuscripts are copy-edited. Particularly if English is not your first language, before submitting your manuscript, HRA advises the work to have it edited for language. Artificial Intelligence (AI)–Assisted Technology At submission, the authors should disclose whether they used artificial intelligence (AI)–assisted technologies in the production of the publication and how AI was used. However, authors should not list AI and AI-assisted technologies as an author or co-author, nor cite AI as an author.

TYPES OF ARTICLES The main sections are original articles, clinical cases, brief reports, review articles, letters to the editor, pictures and disease, medicine and society or book reviews

CHECK LISTS 1. For studies dealing with diagnostic accuracy, use the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/stard/ 2. For randomized controlled trials, use the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement (BMJ 2010; 340). 3. For systemic reviews and meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy studies, follow the PRISMA-DTA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews-Diagnostic Test Accuracy) guidelines) http://www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/DTA. 4. For observational studies, such as cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies, use the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. https://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=strobe-home

ARTICLE PROCESSING CHARGES (APC) Article submission is free of charges, but if your paper is accepted for publication, you will be asked to pay article processing charges to cover publications costs (220-250 $), depending on the type, complexity and length of the work, and on the number of authors. To guarantee HRA's independence, APC cover publication charges such as electronic archiving, plagiarism checking, editing, peer review process, site maintenance and web-hosting, proofreading, quality check, PDF designing and article maintenance. FAST TRACK Please, contact the editor-in-chief. Special article processing charges may apply.

Developed By

Address Health Research in Africa Afrimvoe Medical Services PO Box 17583, Yaoundé Cameroon.

Contact Info Samuel Nko'o-Amvene Phone: +237699970946 / 677257000 Email: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 05 September 2023

A new model for public health in Africa can become a reality

- Jean Kaseya 0

Jean Kaseya is director-general of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

This year is a crucial one for the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). Launched by the African Union (AU) in 2017 after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, the organization was directed by Cameroonian virologist John Nkengasong for its first five years, including the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. I succeeded him as director-general in April after more than 25 years of managing public-health programmes across Africa, working with bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations children’s charity UNICEF and GAVI, the vaccine alliance.

The Africa CDC faces many challenges, not least to apply the lessons learnt from COVID-19 ( C. T. Happi & J. N. Nkengasong Nature 601 , 22–25; 2022 ) as we strive to become a world-class, self-sustaining and agile institution. According to our 2022 priority ranking of infectious diseases, Ebola, cholera and COVID-19 have the highest epidemic potential across Africa, and the diseases the continent is least prepared for are the plague and Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever, as well as any as-yet unknown disease.

Africa is bringing vaccine manufacturing home

Our remit has also expanded to include non-infectious diseases and mental health. In many AU nations, people are more likely to die of non-communicable diseases — such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes — than of communicable, nutritional, maternal and perinatal conditions put together. Yet less than 20% of AU member states have surveillance programmes for non-communicable diseases.

In response to these challenges, our efforts to transform public health on the continent are focused on six areas:

Local manufacturing of vaccines, diagnostics and treatments. The Africa CDC must coordinate the continental agenda on local manufacturing of these fundamental health-care tools , targeting outbreak-prone as well as non-communicable diseases, and mental-health conditions. This includes working with various stakeholders to ensure that appropriate regulatory frameworks are in place, providing manufacturers with financial support and helping to create a conducive market environment. To help expand regional manufacturing capabilities, we have signed a memorandum of understanding with GAVI to work on market design and forecasting of vaccine demand.

Improved surveillance, intelligence and early-warning systems. A new partnership between the Africa CDC, the WHO and the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin will improve health security on the continent by strengthening integrated disease surveillance at the community level, democratizing genomic surveillance and strengthening epidemic intelligence. The first phase will be implemented in Gambia, Mali, Morocco, Namibia, Tunisia and South Africa.

We are also working to outfit all rural health clinics with tests for the 15 most common infectious diseases. Ruling out pathogens that researchers already know about is the best way for these clinics to reliably flag potential new diseases — and prevent them from jumping from rural to more densely populated urban areas.

Integrated health systems and robust primary care. Because of the crucial role of primary care in both infectious and non-communicable disease prevention and management, Africa CDC has secured a grant to fund primary health-care facilities in rural areas. Even in areas that don’t have a freezer capable of storing biological samples at −80 °C, much can be accomplished by improving information technology and empowering community-health workers to collect and process samples and send them to central laboratories.

Two years of COVID-19 in Africa: lessons for the world

As part of our mission to mentor and develop the next generation of public-health leaders, this year the Africa CDC has allocated US$3.9 million to training programmes, including for field epidemiologists. In partnership with the Kofi Annan Foundation, established by the Ghanaian former UN secretary-general, we have trained 40 leaders of public-health institutions from 31 AU member states; another 20 have just been accepted for training.

Expanded networks of laboratories. Since 2020, the Africa CDC’s Pathogen Genomics Initiative has conducted 5 training sessions and delivered sequencing and automation systems, equipment and reagents to 14 AU member states, broadening access to genomic surveillance.

Emergency preparedness and response. To improve cross-border coordination, the Africa CDC will harness technologies developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. One example is the PanaBIOS system, a transcontinental digital suite and mobile application for monitoring disease outbreaks, which will be used by 27 countries.

Strong national public-health institutes. The Africa CDC has begun bolstering national public-health institutes and emergency operations centres in 20 AU member states and will eventually establish a support team in each member state. We also met with a group of AU health ministers to devise shared negotiation strategies for the WHO’s proposed pandemic treaty and the UN High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage.

All six of these actions will require sustained support from African communities, AU member states, donors and other partners. I am convinced that a new way of doing public health in Africa is within reach.

Nature 621 , 9 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02749-5

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

Africa: a new dawn for local vaccine manufacture

- Public health

- Developing world

Could bird flu in cows lead to a human outbreak? Slow response worries scientists

News 17 MAY 24

Neglecting sex and gender in research is a public-health risk

Comment 15 MAY 24

Interpersonal therapy can be an effective tool against the devastating effects of loneliness

Correspondence 14 MAY 24

Gut microbes linked to fatty diet drive tumour growth

News 16 MAY 24

Dual-action obesity drug rewires brain circuits for appetite

News & Views 15 MAY 24

Experimental obesity drug packs double punch to reduce weight

News 15 MAY 24

Imprinting of serum neutralizing antibodies by Wuhan-1 mRNA vaccines

Article 15 MAY 24

Vaccine-enhancing plant extract could be mass produced in yeast

News & Views 08 MAY 24

UTIs make life miserable — scientists are finding new ways to tackle them

News 02 MAY 24

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow required to lead exciting projects in Cancer Cell Cycle Biology and Cancer Epigenetics.

Melbourne University, Melbourne (AU)

University of Melbourne & Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre

Overseas Talent, Embarking on a New Journey Together at Tianjin University

We cordially invite outstanding young individuals from overseas to apply for the Excellent Young Scientists Fund Program (Overseas).

Tianjin, China

Tianjin University (TJU)

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology

SPST seeks top Faculty scholars in Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Precision Instruments and Optoelectronic Engineering

We are committed to accomplishing the mission of achieving a world-top-class engineering school.

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Mechanical Engineering

Aims to cultivate top talents, train a top-ranking faculty team, construct first-class disciplines and foster a favorable academic environment.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Announcements

- About AOSIS

Journal of Public Health in Africa

- Editorial Team

- Submission Procedures

- Submission Guidelines

- Submit and Track Manuscript

- Publication fees

- Make a payment

- Journal Information

- Journal Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Article RSS

- Support Enquiry (Login required)

- Aosis Newsletter

Quick links:

- Articles by Author

- Articles by Issue

- Articles by Section

- Find an Article

- Login / Log Out

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get specific, domain-collection newsletters detailing the latest CPD courses, scholarly research and call-for-papers in your field.

Journal of Public Health in Africa | ISSN: 2038-9922 (PRINT) | ISSN: 2038-9930 (ONLINE)

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

Africa’s New Approach to Public Health

Related content.

A Brief History of Traffic Deaths in the U.S.

The Hunger Gap

Rewriting the Story of Life’s Later Years

Inside the Movement to Transform Mental Health in Sierra Leone

What to Know About COVID FLiRT Variants

- Open access

- Published: 11 December 2021

Measuring health science research and development in Africa: mapping the available data

- Clare Wenham ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5378-3203 1 ,

- Olivier Wouters 1 ,

- Catherine Jones 2 ,

- Pamela A. Juma 2 ,

- Rhona M. Mijumbi-Deve 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Joëlle L. Sobngwi-Tambekou 2 , 5 &

- Justin Parkhurst 1

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 19 , Article number: 142 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5693 Accesses

9 Citations

33 Altmetric

Metrics details

In recent years there have been calls to strengthen health sciences research capacity in African countries. This capacity can contribute to improvements in health, social welfare and poverty reduction through domestic application of research findings; it is increasingly seen as critical to pandemic preparedness and response. Developing research infrastructure and performance may reduce national economies’ reliance on primary commodity and agricultural production, as countries strive to develop knowledge-based economies to help drive macroeconomic growth. Yet efforts to date to understand health sciences research capacity are limited to output metrics of journal citations and publications, failing to reflect the complexity of the health sciences research landscape in many settings.

We map and assess current capacity for health sciences research across all 54 countries of Africa by collecting a range of available data. This included structural indicators (research institutions and research funding), process indicators (clinical trial infrastructures, intellectual property rights and regulatory capacities) and output indicators (publications and citations).

While there are some countries which perform well across the range of indicators used, for most countries the results are varied—suggesting high relative performance in some indicators, but lower in others. Missing data for key measures of capacity or performance is also a key concern. Taken as a whole, existing data suggest a nuanced view of the current health sciences research landscape on the African continent.

Mapping existing data may enable governments and international organizations to identify where gaps in health sciences research capacity lie, particularly in comparison to other countries in the region. It also highlights gaps where more data are needed. These data can help to inform investment priorities and future system needs.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Health sciences research (HSciR) has been defined to include basic, clinical and applied science on human health and well-being, as well as the determinants, prevention, detection, treatment and management of disease [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. To date, the majority of HSciR has taken place in the Global North [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. As of 2018, less than 1% of scientific articles published worldwide each year include at least one author based at an African institution [ 7 ].

In the past few years, however, a number of international organizations, including the African Union [ 8 ], WHO [ 9 ] and the World Bank [ 10 ], have called for political and economic investment in HSciR in Africa. Several high-profile reports have further raised awareness of the so-called 10/90 gap: only a 10th of global expenditure on health research is targeted to issues that affect the poorest 90% of the world’s population [ 5 ].

There are two key reasons why investments in HSciR in Africa may be particularly important from a developmental perspective. First, the promotion of a strong health science industry, as part of broader efforts to establish a robust research and development (R&D) landscape, can contribute to development goals by reducing national economies’ reliance on primary commodity and agricultural production; this can help governments develop knowledge-based economies, which may be important for macroeconomic growth [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. In a seminal 1990 report, the Commission on Health Research and Development [ 4 ] stated that strengthening research capacity in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is “one of the most powerful, cost-effective and sustainable means of advancing health and development” (p. 71).

Second, HSciR may contribute to improvements in health, social welfare and poverty reduction through domestic application of the findings of the research itself [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. The 2013 World Health Report stressed that all nations should be producers, users and consumers of HSciR [ 6 ]. Africa is home to nearly one sixth of the world’s population and is estimated to account for about a quarter of the global burden of disease [ 19 ]. Yet only a small fraction of global health research currently focuses on diseases which exclusively affect LMICs [ 20 , 21 ]. While there have been developments in the HSciR landscape over the past three decades, many LMICs have been unable to build up sufficient capacity to develop their own evidence base nationally to inform policy directly and/or to improve their population’s health [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. The International Vaccines Task Force of the World Bank has highlighted the importance of building research capacity to lower the risk of emergent epidemics [ 25 ].

To date, few academic studies have evaluated HSciR capacity in LMICs. The most widely available indicator of health research capacity is the publication of health-related scientific journal articles. These have been the focus of research in the past, with bibliometric analyses undertaken to map the numbers of African publications related to cardiovascular diseases [ 26 , 27 ], genomics [ 28 ], health economic evaluation [ 29 ], health policies and systems [ 30 , 31 ], human immunodeficiency virus [ 32 ], neglected tropical diseases [ 33 ] and public health [ 34 ]. Four studies have also examined the total number of African publications on any health-related topic (as indexed in major bibliographic databases) [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Beyond publication outputs, however, researchers have also collected data on investments in health-related R&D [ 35 ], clinical trial infrastructures [ 25 , 35 ], healthcare workforce numbers [ 39 ] and the numbers of universities and “centres of excellence” [ 39 , 40 ] in African countries to estimate HSciR capacity.

Each of these studies can help to understand individual aspects of HSciR capacity in African countries, yet no single piece of information can fully capture the degree of capacity in a country or region. There remains a need for analyses which attempt to collect and analytically combine data on multiple indicators to provide a more comprehensive analysis of HSciR capacity across the continent.

The importance of knowledge economies

Science and innovation, if well-utilized, may play a core role in realizing sustainable development [ 1 , 41 ]. As seen from the experiences of many industrialized nations, scientific research and linked innovations have been core to economic and social advancement over the past two centuries—be it medical innovations such as vaccines and antibiotics, or industrial innovations in manufacturing, communications and computation [ 42 , 43 , 44 ].

More recently, questions have been asked as to whether scientific research supports development, or whether it represents a product of development [ 45 , 46 ]. Both these positions have their justifications. In terms of science resulting in development, it is research and knowledge generation, linked with subsequent innovation and application of that knowledge, that some argue has been critical to overcoming key development challenges in LMICs [ 45 ]. Under this position, the need to invest in capacity for mobilizing and using science and innovation can be viewed as an essential component of strategies for promoting sustainable development [ 47 , 48 , 49 ]. This argument appears to underpin the inclusion of research within the Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 3.B specifically focusses on health research for LMIC needs, calling for “supporting the development of research and development of vaccines and medicines for health conditions which affect LMICS”; goals 9.5 and 12.A call for increased scientific, technical and research capacity more generally in developing countries [ 50 ].

Many calls for the creation of so-called knowledge economies are linked to thinking of research activity as an end goal of development. It has been argued that the conceptualization of an economy of knowledge reproduces a growth and market-oriented rationale for knowledge production, accumulation and diffusion which has particularly influenced the international aid, education and development agenda [ 51 , 52 ]. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [ 11 ] defines knowledge-based economies as those “which are directly based on the production, distribution and use of knowledge and information’’ (p. 7). The World Bank has classified the knowledge economy into four areas: economic and institutional regime, education and skills, information and communication infrastructure, and an innovation system—with the agency going so far as to create a Knowledge Economy Index (KEI) as an indicator of a country’s “preparedness” for a knowledge economy [ 53 ].

Asongu and colleagues [ 54 ] found the overall trends in African countries’ performance between 1996 and 2010 differed across the World Bank’s KEI dimensions: Tunisia led in education, the Seychelles in information and communication technology, South Africa in innovation and Botswana and Mauritius in institutional regime. Oluwatobi and colleagues [ 55 ] have argued that the potential for knowledge production and innovation in Sub-Saharan Africa is mitigated by the level of human capital and quality of institutions. Overall, quality education and strong institutions are held to be imperative for the transformation into a knowledge economy [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. Both educational and economic institutions may create enabling structures for developing knowledge and innovation and for economic growth, but their influence varies according to institutional arrangements, income and development levels in countries [ 57 , 58 , 59 ]. In particular, education plays a vital role in strengthening human capital, which directly influences the ability to create, absorb, transform, disseminate and use knowledge and innovation [ 55 , 60 , 61 , 62 ]. Education and training emphasizing the value of traditional knowledge and culture also strengthens human capital to innovate contextually relevant solutions for local development problems [ 54 , 59 , 63 ].

The contribution of HSciR

Within the broader remit of science for development, HSciR is vital in its own specific way. HSciR has led to collective human benefit, development of medical treatments, or better understanding of health risks of activities such as tobacco smoking. At a national level, HSciR can also specifically generate evidence that is useful for public service planning and programme implementation. It can provide policy-relevant information, including disease trends, risk factors, outcomes of interventions and patterns of care, as well as health systems and services costs and outcomes [ 64 ].

Grant and Buxton developed a framework to estimate the value that HSciR provides to countries [ 65 ]. Their analysis has included as benefits reduced expenditure on delivering existing services; service and provision delivery improvements; health service effectiveness improvements; greater overall improvements in health and equity with more consideration of allocation of resources and access to provision; and a healthy, performance-driven workforce.

Finally, Dobrow et al. have shown that HSciR evidence can in turn support development of the process of health policy-making through the identification of new issues worthy of bringing to the policy agenda in a particular context, supporting decision-makers in their analyses of policy content and continued direction and policy impact monitoring and evaluation [ 66 ]; Gilson has noted that health policy and systems research more specifically provides insights into how policy decisions are made and the factors affecting successful policy implementation [ 67 ]. In many ways, these examples capture the benefits widely seen to follow from a system of evidence-informed policy-making, whereby a more systematic and robust use of research evidence in decision-making is seen to improve planning effectiveness efficiency and policy implementation to serve the broader social good [ 16 , 68 ].

HSciR input and output by national governments are not uniform, with significant disparities between regions or income levels and also across countries within the same region or at similar levels of income [ 69 , 70 ]. On the African continent, for example, Tanzania and Lesotho had similar levels of GDP per capita (US$ 2365 and US$ 2494, respectively, in 2013); however, the percentage of GDP invested in research in Tanzania was more than three times as high as in Lesotho (0.28 vs 0.08), while the number of publications per million inhabitants was nearly 50 times as high, at 770 in Tanzania compared to 16 in Lesotho [ 71 ].

One of the most critical contextual determinants of HSciR outputs is historical evolution of research systems. For those African nations subject to colonial rule, for instance, modern forms of research were often developed in service to the economic interests of the colonizing power. The focus of research thus centred on key exports such as agriculture-, forestry- and mining-related activity, with little interest in HSciR to benefit local populations [ 72 , 73 ]. After independence, HSciR remained embryonic, with governments often choosing to invest in economies based on the commercialization of cash products and natural resources rather than in the development of research and technology [ 74 ]. Moreover, countries which have experienced conflict, instability and other sociopolitical crises have had to direct resources towards reconstruction and peacekeeping investments, rather than towards scientific research and innovation [ 75 ].

For some nations, the catalyst for investment and development of HSciR has mainly been through the emergence of health crises—new diseases such as HIV/AIDS and Ebola, or the rising incidence of tuberculosis and plague [ 76 , 77 ] (MTN, 2017). Outbreaks have also at times inspired new policies calling for investment in HSciR by global organizations such as WHO and UNESCO [ 78 , 79 ]. These calls for investment have allowed for a more open dialogue and progress on conceptualizing the importance of health research, even within low-income African states—with several governments now committed to investing in scientific research in connection with a country's economic and sustainable development priorities [ 80 , 81 , 82 ]. Despite these shifts, such as the Bamako Initiative, WHO’s efforts to regionalize research efforts and signs of increased attention to domestic HSciR, key drivers of research and research funding in the health sector remain exogenous to African states. Indeed, funding largely reflects global HSciR priorities, with limited options for investigator-initiated research on local health concerns.

How to measure HSciR?

While there is a strong case that HSciR in LMICs is important at national and global levels—for improving health, preventing epidemic spread, supporting health policy and systems and as an influential factor of national development more broadly—there is no single framework or consensus method to assess HSciR capacity across countries. Indicators for measuring and monitoring HSciR generally include standard output indicators of knowledge production and innovation, such as scientific journal articles per million inhabitants or patents per million inhabitants [ 53 ] and input and process indicators of health R&D. Such process indicators can include gross domestic R&D expenditure on health as a percentage of GDP, number of clinical trials per million inhabitants, research grants and full-time equivalent health researcher per million inhabitants [ 35 ]. From the perspective of decision-makers in national agencies, these indicators of knowledge production and human resources for research are helpful for benchmarking performance against regional and global comparators and for informing policy and strategy to strengthen R&D [ 83 ].

Researchers and international organizations have attempted to compile indicators and measure HSciR capacity in different ways. For example, WHO has created a Global Observatory on Health R&D which aims to “consolidate, monitor and analyse relevant information on health research and development activities” [ 84 ]. This uses a logic model perspective to assessing HSciR, tracking a range of indicators to monitor health R&D inputs, processes and outputs as identified and defined by Røttingen and colleagues [ 35 ]. While these indicators are useful for monitoring and benchmarking the state of HSciR and development activities, funding and performance at the national level, they do not provide information to assess the overall capacity of national health research systems as a set of “people, institutions and processes” for HSciR [ 4 ]. Moreover, there are incomplete or missing data for many of these indicators.

A second approach takes a systems perspective to assessing HSciR capacity, recognizing that R&D funds and personnel represent but two components of a nation’s HSciR capacity. Pang and colleagues [ 17 ] defined a national health research system within a conceptual framework considering four key tenets: stewardship, financing, creating and sustaining resources, and producing and using research. This framework has been operationalized under the Research for Health unit at the WHO Regional Office for Africa through the development of a “barometer” that aims to assess the evolution of national health research systems. The team collected data from surveys of individual health research focal points in countries (with rounds in 2003, 2009, 2014 and 2018) [ 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 ]. Key informants within national ministries of health and other institutions replied to questions about whether HSciR policies, institutions or other resources were currently in place in the country (e.g. national health research policy, national research ethics committee, national health research institute, national budget line for health research) [ 85 ].

In applying this approach, Kirigia and colleagues [ 86 ] analysed trends between 2003 and 2014 to show that although there have been positive gains across many functions, there are still considerable gaps in many African countries. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, fewer than 50% of countries have a nationwide official health research policy, or a national health research strategy/policy plan, a HSciR law or regulation, or a much-needed budget line for HSciR within the ministry of health. Approximately half of states analysed have a national health research institute/council, a research programme at the governmental level, or an equivalent health research management forum. Public financing for HSciR is also typically measured to be very low, with minimal progress towards the goal of 2% of the national health expenditure allocated to HSciR. Instead, most funds for HSciR come from external sources such as international organizations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or multilateral/bilateral partners. According to Kirigia et al., the weakest elements of African health research systems are human resources for HSciR, government spending on HSciR, publications in peer-reviewed journals, and research institutions to conduct HSciR [ 87 ].

Overall, there have been a variety of attempts to identify key elements of HSciR activity, performance and capacity in Africa. Some have assessed R&D potential, measured funding inputs or identified gaps in national HSciR systems. These efforts shed light on where strengths and weaknesses lie, but currently do not provide a comprehensive review and synthesis of data on which to comparatively evaluate HSciR knowledge and innovation, HSciR and development activities and HSciR systems at the national level across Africa.

The aim of this paper is to build on earlier work by collecting and aggregating data on a range of variables to consider HSciR activity, performance and capacity in all African countries. We develop a framework for evaluating a country’s capacity for HSciR based on publicly available global data sources. This framework incorporates and expands on indicators from previous studies. Using this framework, we present data on HSciR capacity in each of the 54 UN-recognized African states to map current capacity across the region for HSciR—providing one of the first analyses to systematically outline the contribution of African countries to HSciR across such a wide range of indicators.

Data collection

We reviewed data for each of the 54 UN-recognized states in Africa. This excluded any foreign departments (e.g. Mayotte), regions (e.g. Réunion) or territories (e.g. Saint Helena) located in Africa, as well as the disputed territory of Western Sahara. We collected population and gross domestic product (GDP) data from the World Bank [ 90 ] for each of these states to be able to benchmark our findings against broader development metrics.

We sought to identify a range of indicators which could help measure the HSciR capacity in each country. We used the indicators selected by the WHO Global Observatory on Health R&D database as a starting point, which comprised GERD as a proportion of GDP, health researchers per million inhabitants, number of institutions and official development assistance for the medical research and basic health sectors as a proportion of gross national income [ 91 ]. We then supplemented this with others measures of HSciR capacity which we identified through discussions between authors and members of a project oversight committee, Footnote 1 including bibliographic data, data on clinical trial infrastructures, regulatory environment, intellectual property rights and research funding. All data were acquired between June and September 2018.

To classify and conceptualize the various indicators available, we followed the Donabedian [ 92 ] model of healthcare quality measurement to categorize our indicators into one of three types: structural, process and output measures related to HSciR. Structural measures capture inputs into the system and thus comprised metrics such as workforce numbers, budget allocation to R&D and numbers of organizations, regulations and guidelines on human subject protections. Process measures are indicators of ongoing HSciR activities, including numbers of clinical trials registered and patent applications. Finally, output measures capture the outputs of research activities including numbers of peer-reviewed publications and citations for these publications.

Structural indicators

R&d expenditures and personnel.

Data on R&D expenditure and personnel were obtained from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2016, or the most recent available year) [ 91 ]. We collected data on the number of full-time-equivalent staff in the following categories: (i) R&D personnel (per million inhabitants), (ii) researchers (per million inhabitants) and (iii) researchers with doctoral or equivalent degrees (as a proportion of total number of researchers). From the same database, we also collected data on GERD in current purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars (in thousands); these figures were also shown as a proportion of GDP and per capita. Whenever possible, we collected expenditure and personnel data specific to medical and health sciences.

Research institutions

We collected data on the number of universities in each country, using a list based on information from the International Association of Universities [ 93 ]. We recognize that there may be limitations affecting the quality of data from this source; thus, we also identified the number of African universities listed on the most recent global university rankings of three influential publishers: Quacquarelli Symonds Limited ( QS World University Rankings ) [ 94 ], Times Higher Education ( THE World University Rankings ) [ 95 ] and Shanghai Ranking Consultancy ( Academic Ranking of World Universities ) [ 96 ]. Whilst this may not be comprehensive, it allows an indication of the number of institutions across the continent.

We further collected data on the number of institutional review boards [ 97 ] and WHO Collaborating Centres [ 98 ] in each country and noted whether or not there exists a national ethics committee [ 99 ] and national public health institute [ 100 ].

Research funding

We collected data on international funding awarded to researchers in each country (2008–2017) from the 10 largest public and philanthropic funders of health research globally (listed in order of size) [ 101 ]: (1) United States National Institutes of Health, (2) European Commission, (3) United Kingdom Medical Research Council, (4) French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, (5) United States Department of Defense (including the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs), (6) Wellcome Trust, (7) Canadian Institutes of Health Research, (8) Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, (9) Howard Hughes Medical Institute and (10) German Research Foundation.

The data were collected from each funder’s website. As we are seeking to understand current capacity, we only counted funding allocated to researchers based at institutions in African countries. We excluded funding for research projects in which the principal investigators were based at non-African institutions, even if these projects included collaborators, field sites or locations of research in Africa.

Foreign currencies were converted to dollars based on the yearly average exchange rates published by the World Bank [ 90 ]. All amounts were reported in 2018 US dollars based on the United States consumer price index adjustments to account for inflation.

Process indicators (clinical trial infrastructures, intellectual property rights and regulatory capacities)

Data on the numbers of clinical trials and records, as of 4 August 2018, were extracted from the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) [ 102 ] and United States National Institutes of Health database (ClinicalTrials.gov) [ 103 ]. ClinicalTrials.gov indexes trials of new investigational drugs, whereas the ICTRP indexes data from several sources, including the European Union Clinical Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number register and Pan African Clinical Trial Registry. A full list of data providers can be found on the ICTRP website [ 102 ]. The ICTRP registry accepts all types of clinical research studies, including trials of public health interventions.

We also collected information on the number of organizations, regulations and guidelines on human subjects protection in each country. These data, which are collected annually by the United States Department of Health and Human Services [ 104 ], reflect protections in each of the following categories: “general (i.e. applicable to most or all types of human subjects research)”, “drugs and devices”, “clinical trial registries”, “research injury”, “social-behavioural research”, “privacy/data protection”, “human biological materials”, “genetic” and “embryos, stem cells and cloning”. We used the 2018 edition of the compilation of protections [ 104 ].

Finally, we collected data from the World Intellectual Property Organization on the numbers of patents issued to residents in each country (2016, or most recent available year) [ 105 ].

Output indicators (publications and citations)

To systematically collect publication data, we searched Scopus, the largest global peer-reviewed literature abstract and citation database [ 106 ]. Scopus was chosen as it includes a larger volume of non-English-language journals than many other major bibliographic databases (e.g. Web of Science or PubMed/Medline) [ 106 ]. We searched for any articles published in the following Scopus subject areas: health sciences (medicine, nursing, veterinary, dentistry, health professions) and life sciences (agricultural and biological sciences, biochemistry, genetics and molecular biology, immunology and microbiology, neuroscience and pharmacology, toxicology and pharmaceutics). We included the following types of publications: articles, in press, books, chapters and conference papers.

We searched for articles published with at least one author based at an institution in each of the 54 countries, using the “Affiliation country” field in Scopus. We searched the names of each country in English, French and Portuguese, as well as variant spellings of country names. We restricted the searches to publications published in the 10-year period from 2008 to 2017. The search strategy, including the country names, can be found in Additional file 1 .

For each country, we extracted data on the number of publications with at least one author based in the country, as well as the number of publications first authored by a local researcher. We also collected citation data for all articles. For publications published in the 5-year period from 2013 to 2017, we collected data on the proportion of publications with international, institutional and national collaborators; these data were unavailable for articles published before 2013. These data were obtained in SciVal, a research information tool developed by Elsevier to synthesize bibliometric data from Scopus.

Data for each individual indicator are presented as a series of tables in Additional file 2 . We describe findings for each indicator in Additional file 3 , before providing a summary table in this section (see Table 1 ).

Table 1 below presents data for selected indicators. We have shaded each cell to reflect whether the data in that cell fall in the highest, middle or lowest tercile of the range, with green for the top tercile, yellow the middle and orange the bottom. The table shows that while there were some high achievers across the board, the results were varied for most states—suggesting high relative performance in some indicators, but lower in others (or missing data). For example, Libya was a relatively high achiever for publications, first author publications and number of research institutions, but lagged behind this success with the number of clinical trials conducted within the country. Conversely, Burundi had low numbers of publications, first author publications, number of clinical trials and GERD as a percentage of GDP, but performed relatively well in number of research institutions. While many of the higher-income countries unsurprisingly perhaps do well on numerous indicators, some lower-income countries also appear to perform well, such as Senegal or Kenya.

Additional file 2 presents a further set of 10 figures to illustrate associations between various metrics and GDP (gross and per capita). In general, there was a strong positive association between GDP and the various indicators collected. However, there could be significant spread around the linear trend lines plotted, indicating some countries performing particularly well or poorly relative to income level.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, there is no single indicator for accurately ascertaining HSciR. Accordingly, we used a variety of available metrics that serve as proxy indicators. Thus, there is a risk that these proxies do not capture the full landscape we sought to map. For example, we have not accounted for broader financing and infrastructure which contributes to HSciR—such as buildings, routine access to electricity, and primary and secondary education attainment. Each of these may contribute to a country’s capacity for HSciR, but they may be part of broader development measures. Such indicators may not clearly demonstrate the impact of HSciR and can be difficult to disaggregate. However, there is support for the indicators we selected for our framework from the literature discussing measurement of health R&D globally and in Africa [ 35 , 107 ]. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that there are multiple challenges and issues with measuring HSciR performance using universal indicators in the contexts of African national health research systems [ 108 ].

Second, there are some important limitations of the sources of data used. Given the lack of consistent data on HSciR collected and reported at national levels, or indeed at the regional level, we restricted our searches to global-level data sets to try to ensure some degree of comparability. This approach fails to take into account the reality of what might be occurring within countries which is not reported formally or is not published at the national, regional or global level. Moreover, at the global level there was a lack of data for several indicators, or these data were outdated. The most comprehensive data sources were for publications and clinical trials, but many other indicators were missing results for numerous countries. In some data categories, there were issues of reliability and comparability between sources. Furthermore, while we aimed to collect data from 2007 to 2017, some data points had to come from before this time frame when more recent data were not available. This included data on patent applications and human resources. Ultimately, we decided that including data outside the period was better to get a fuller picture of the HSciR landscape.

Third, for the output indicators, it is important to note that research outputs are not always published in peer-reviewed journals; therefore, limiting the analysis to bibliometrics from SciVal could have led us to outputs in other sources and formats. Our approach does not include research published outside of peer-reviewed journals, including government or nongovernmental literature policy reports, open data sets, software or other grey literature. Scopus also does not index all journals published in African states. Similarly, we recognize that for the structural indicators, we only included universities, which may provide an incomplete picture of key research structures and institutions within a country. While the presence of universities was felt to be a reasonably comparable metric to serve as a proxy for infrastructure capacity, it is known that there are very important contributors to the HSciR landscape in Africa that are not affiliated to a specific university per se—for example, Tanzania’s Ifakara Health Institute, the Kenya Medical Research Institute and the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC). These entities undertake a large amount of work at national or regional levels. Indeed, some centres of excellence in Africa may be undertaking a very large share of HSciR in a given country, and not be affiliated with a university. While the activities of such organizations might be captured in publication metrics or clinical trials data, future efforts to evaluate HSciR capacity may need to consider ways to identify, count or compare the importance of centres of excellence as core hubs of institutional capacity [ 40 ].

Fourth, we were unable to find a consistent data source across the African continent to measure government budget allocation to HSciR. Instead, we used GERD as a proxy, which (see Table 1 ) captures investments in R&D (although not disaggregated by health sciences). Furthermore, data on GERD aggregate total expenditure on R&D from the government as well as university, private enterprise and not-for-profit sectors; yet this breakdown is rarely available for many African countries. The data available through internationally recognized and consistent sources on GERD for medical and health sciences are sparse (see Additional file 2 : Table S4). The WHO African Barometer survey collects data on health research budgets, which is self-reported by health research focal points at ministries of health. Data from 2018 reported that 24 countries had a dedicated budget line for health research and that 37 countries regularly tracked health research spending from all sources [ 89 ]. Whilst these data show a limited scope of HSciR funding, taking only the ministry of health budget and not other sources, it could contribute to better understanding of HSciR funding in countries. These data have not been made publicly available by intergovernmental sources, and we found no centralized data on national research funds on the continent in any comparable way, although in-depth qualitative case studies in a sample of nine African countries found these in five instances [ 109 ]. Future work evaluating HSciR could investigate which countries of the region have such funds, as there does not appear to be any data source indicating it at present despite a nascent literature on the topic [ 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 ]. Similarly, when measuring the number of universities in each state, we were not able to ascertain whether these universities undertake research or solely offer degrees or training in health sciences.

Fifth, these metrics are all aggregated at the national level, and thus this crude analysis fails to reveal any subnational interaction. A more in-depth analysis could reveal particular “hubs” of excellence, as well as institutional capacity or individual capacities which form key components of the national landscape.

Taken as a whole, the existing data we were able to analyse offer a nuanced view of current HSciR on the African continent. We hope that such mapping facilitates governments and international organizations in identifying gaps in HSciR capacity, particularly in comparison to other countries in the region, if important. Our findings importantly also highlight gaps where more data are very much needed. These data can help to inform investment priorities and future system needs.

Our findings have raised several issues for consideration:

There are some unsurprising high performers across the variety of indicators, such as South Africa, Egypt and Tunisia, which score highly across most metrics. However, it is worth noting that it is not simply the level of development (GDP) or international or national financing for HSciR (GERD and international research funding) that leads to success in HSciR. Nations which have had major donor investment in HSciR (per capita), including Uganda and Gambia, have not necessarily emerged as top performers across the range of proxy indicators used. Whilst the current level of economic development does not appear to play a significant role in a country’s HSciR capacity per se, our analysis shows a clear correlation between GDP and a range of individual metrics (Additional file 2 ), although this is not evidence of causality).

There are several possible explanations for these results. One explanation might be that reliance on donor funding has limited the sustainability of the health research sector when these collaborations end [ 114 , 115 ], or that donor investment focused on projects which lacked significant improvements in broader infrastructures within the national system. Alternatively, international arrangements may result in research agendas set by the Global North, which could imply that they either reflect the needs of the funding location [ 116 , 117 ], a focus on spotlight issues [ 118 ] or so-called parachute research [ 119 , 120 ] and bypass local research institutions and expertise [ 121 ], any of which may be limited in improving health research outcomes or capacity in the host location. The importance of local research development, however, has been highlighted as vital to building a knowledge economy and addressing domestic health concerns, as in-country researchers have the best understanding of the national agenda and cultural context which increased the likelihood of evidence uptake by policy-makers [ 22 , 122 ]. Yet, it is clear that several African governments have not met the commitment to ensure that 1% GDP is dedicated to research, and many have struggled to make even minimal investments in HSciR from public finances, being more reliant on international donors or private entities.

Another explanation is that using these indicators to measure performance does not capture the nuance of what is occurring within each system, particularly within each nation and the progress that research systems are making more holistically. For example, these metrics are not able to infer political commitment to HSciR, the relative importance of the HSciR landscape globally, how national systems have developed, where the success stories are and where barriers remain to solidifying knowledge economies. They are also unable to infer the historical contexts which led to the development of these systems, whether rooted in colonial science or postcolonial investments, each of which will lead to different-looking HSciR environments.