- Human Editing

- Free AI Essay Writer

- AI Outline Generator

- AI Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Research Paper Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Paraphrasing tool

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Rephraser

- AI Paragraph Rewriter

- Summarizing Tool

- AI Content Shortener

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Citation Generator

- Reference Finder

- Book Citation Generator

- Legal Citation Generator

- Journal Citation Generator

- Reference Citation Generator

- Scientific Citation Generator

- Source Citation Generator

- Website Citation Generator

- URL Citation Generator

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

Most Popular

10 days ago

Why Congress Cares About Media Literacy and You Should Too

How educators can reinvent teaching and learning with ai, plagiarism vs copyright.

12 days ago

Who vs Whom

11 days ago

Top 20 Best Books on American History

Writing a first draft.

Steps for Writing a First Draft of an Essay

- Take a closer look at your assignment and the topic if it was given to you by your instructor. Revise your outline as well. This is needed for your clearer understanding of the tasks you must accomplish within the draft, and to make sure you meet the requirements of the assignment.

- Sketch out the introduction of your essay. At this point, don’t get stalled on form; introductory part should inform readers about what the topic is, and state your point of view according to this topic. The introduction should also be interesting to read to capture readers’ attention, but this task has more to do with thoughtful and scrupulous writing, and thus should be left for later.

- Based on your outline, start transferring your ideas to paper. The main task here is to give them the initial form and set a general direction for their further development, and not to write a full paper.

- Chalk out the summarizing paragraph of your essay. It should not contain any new ideas, but briefly reintroduce those from the main body, and restate your thesis statement.

- Read through the draft to see if you have included the information you wanted to, but without making any further corrections, since this is a task for the second and final drafts.

- If you are not sure that you checked everything, send it out for proofreading. Searching through the best essay service reviews, you can get some recommendations of where to look.

Key Points to Consider

- While an outline is needed to decide on what to write, the first draft is more about answering a question: “How to write?” In the first draft, you shape your ideas out, and not simply name and list them, as you did in an outline.

- When you start writing your thoughts down, it may happen that one idea or concept sparks new connections, memories, or associations. Be attentive to such sidetracks; choose those of them that might be useful for your writing, and don’t delve in those that are undesirable in terms of the purpose of your paper (academic, showing opinion). A successful piece of writing is focused on its topic, and doesn’t include everything you have to say on a subject.

- Making notes for yourself in the margins or even in the middle of the text is a useful practice. This can save you time and keep you focused on the essence of your essay without being distracted by secondary details. For example, such notes could look like this: “As documented, the Vietnam War cost the United States about … (search for the exact sum of money and interpret it in terms of modern exchange rates) U. S. dollars.”

- When you finish crafting your first draft, it is useful to put it aside and completely quit thinking about writing for a certain period of time. Time away will allow you to have a fresh look at your draft when you decide to revise it.

Do and Don’t

Common mistakes when writing a first draft of an essay.

– Editing and revising a draft in process of writing. If you stop after each sentence to think it over, you will most likely lose your flow; besides, many people have an internal editor or critic who can’t stand it if the material is written imperfectly. Therefore, first you should deal with the whole draft, and only after that proofread and edit it.

– Paying too much attention to secondary arguments, factual material, and other minor peculiarities. The main goal of the first draft is to sketch out your main ideas; you can fill it with details later. If you think you will forget about an important fact or remark, make brief notes in margins.

– Ignoring the role of a first draft in the essay writing process. Though it may seem you are wasting time working on a draft, you are working on the essay itself. You need to understand how your outline works in full written form.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Comments are closed.

More from Stages of the Writing Process

Jun 17 2015

Choosing an Essay Topic

May 08 2014

Information Sources

Apr 10 2014

Writing an Introduction

Samples for writing a first draft, parental control as a necessary measure in the upbringing of modern children (part 1) essay sample, example.

Remember Me

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

- What is academic writing?

- Academic Style

- What is the writing process?

- Understanding the title

- Brainstorming

- Researching

First draft

- Proofreading

- Report writing

- Compare & contrast

- Cause & effect

- Problem-solution

- Classification

- Essay structure

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Book review

- Research proposal

- Thesis/dissertation

- What is cohesion?

- Cohesion vs coherence

- Transition signals

- What are references?

- In-text citations

- Reference sections

- Reporting verbs

- Band descriptors

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

For another look at the same content, check out YouTube » or Youku » , or this infographic » .

After writing an outline , the next stage of the writing process is to write the first draft. This page explains what a first draft is and how to write one . There is also a checklist at the end of the page that you can use to check your own first draft.

What is a first draft?

A draft is a version of your writing in paragraph form. The first draft is when you move from the outline stage and write a complete version of your paper for the first time. A first draft is often called a 'rough draft', and as this suggests, it will be very 'rough' and far from perfect. The first draft will lead on to a second draft, third draft, fourth draft and so on as you refine your ideas and perhaps conduct more research . The paper you submit at the end is often called the 'final draft', and emphasises the fact that writing is a process without a definite end (as even the final draft will not be perfect). It should be stressed that a first draft is only suitable for writing where you have some time to complete it, such as longer, researched essays, rather than an exam essay where there will only be a single draft.

How to write a first draft?

As you write your initial draft, you should try to follow your outline as closely as possible. Writing, however, is a continuous, creative process and as you are writing you may think of new ideas which are not in your outline or brainstorm list, and these can be added if they are relevant. Your outline will probably contain a thesis , which is essentially a plan for the whole paper, and you should keep this in mind to decide whether ideas are relevant. It is possible to begin the drafting process at any stage, and some people recommend writing the main body first and the introduction and conclusion later. This makes sense as it can be difficult to introduce something you have not yet finished, though if your outline is detailed enough it is possible to begin at the beginning. When writing the first draft, the main focus will be the ideas and content, meaning you should not worry about grammar, punctuation or spelling. You may end up abandoning whole sections before the final draft, and slowing down to check grammar or spelling at this stage would be a waste of time. It is useful for the first draft to use double-spacing and wide margins on both sides of the paper so that you can add more details and information when you redraft your work.

In short, when writing a first draft, you should do the following:

- try to follow your outline as closely as possible;

- add new ideas if they are relevant;

- keep your thesis in mind while writing;

- begin where you think is best (e.g. main body before introduction);

- focus on ideas and content;

- do not worry about grammar, punctuation or spelling;

- use double-spacing and wide margins for easier redrafting.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres .

Below is a checklist for your first draft.

Oshima, A. and Hogue, A. (1999) Writing Academic English . New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

University of Arizona (n.d.) The Structure of an Essay Draft . Available at: http://www.u.arizona.edu/~atinkham/Essay_Structure.htm (Access date 1/4/18).

Next section

Read more about checking your work in the next section.

Previous section

Read the previous article about writing an outline .

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 02 March 2020.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

Compare & contrast essays examine the similarities of two or more objects, and the differences.

Cause & effect essays consider the reasons (or causes) for something, then discuss the results (or effects).

Discussion essays require you to examine both sides of a situation and to conclude by saying which side you favour.

Problem-solution essays are a sub-type of SPSE essays (Situation, Problem, Solution, Evaluation).

Transition signals are useful in achieving good cohesion and coherence in your writing.

Reporting verbs are used to link your in-text citations to the information cited.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Drafting

Learning objectives.

- Identify drafting strategies that improve writing.

- Use drafting strategies to prepare the first draft of an essay.

Drafting is the stage of the writing process in which you develop a complete first version of a piece of writing.

Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original every time they open a blank document on their computers. Because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process, you have already recovered from empty page syndrome. You have hours of prewriting and planning already done. You know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline.

Getting Started: Strategies For Drafting

Your objective for this portion of Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” is to draft the body paragraphs of a standard five-paragraph essay. A five-paragraph essay contains an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and then type it before you revise. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. In this lesson, Mariah does all her work on the computer, but you may use pen and paper or the computer to write a rough draft.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

What makes the writing process so beneficial to writers is that it encourages alternatives to standard practices while motivating you to develop your best ideas. For instance, the following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about. You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page.

- Write one paragraph at a time and then stop. As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind. This tip might be most useful if you are writing a multipage report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals. If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write. These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can.

Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

Writing at Work

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss. Menu language is a common example. Descriptions like “organic romaine” and “free-range chicken” are intended to appeal to a certain type of customer though perhaps not to the same customer who craves a thick steak. Similarly, mail-order companies research the demographics of the people who buy their merchandise. Successful vendors customize product descriptions in catalogs to appeal to their buyers’ tastes. For example, the product descriptions in a skateboarder catalog will differ from the descriptions in a clothing catalog for mature adults.

Using the topic for the essay that you outlined in Section 8.2 “Outlining” , describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Use your own sheet of paper to record your responses. Then keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

Setting Goals for Your First Draft

A draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you will have the opportunity to make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

In a perfect collaboration, each contributor has the right to add, edit, and delete text. Strong communication skills, in addition to strong writing skills, are important in this kind of writing situation because disagreements over style, content, process, emphasis, and other issues may arise.

The collaborative software, or document management systems, that groups use to work on common projects is sometimes called groupware or workgroup support systems.

The reviewing tool on some word-processing programs also gives you access to a collaborative tool that many smaller workgroups use when they exchange documents. You can also use it to leave comments to yourself.

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you will be able to use it with confidence during the revision stage of the writing process. Then, when you start to revise, set your reviewing tool to track any changes you make, so you will be able to tinker with text and commit only those final changes you want to keep.

Discovering the Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in this chapter step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you make the creative leap from the outline to the first draft. A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that piques the audience’s interest, tells what the essay is about, and motivates readers to keep reading.

- A thesis statement that presents the main point, or controlling idea, of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main idea of the paragraph and implies how that main idea connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be specific facts, examples, anecdotes, or other details that elaborate on the topic sentence.

- A conclusion that reinforces the thesis statement and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

These elements follow the standard five-paragraph essay format, which you probably first encountered in high school. This basic format is valid for most essays you will write in college, even much longer ones. For now, however, Mariah focuses on writing the three body paragraphs from her outline. Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” covers writing introductions and conclusions, and you will read Mariah’s introduction and conclusion in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

The Role of Topic Sentences

Topic sentences make the structure of a text and the writer’s basic arguments easy to locate and comprehend. In college writing, using a topic sentence in each paragraph of the essay is the standard rule. However, the topic sentence does not always have to be the first sentence in your paragraph even if it the first item in your formal outline.

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas. However, as you begin to express your ideas in complete sentences, it might strike you that the topic sentence might work better at the end of the paragraph or in the middle. Try it. Writing a draft, by its nature, is a good time for experimentation.

The topic sentence can be the first, middle, or final sentence in a paragraph. The assignment’s audience and purpose will often determine where a topic sentence belongs. When the purpose of the assignment is to persuade, for example, the topic sentence should be the first sentence in a paragraph. In a persuasive essay, the writer’s point of view should be clearly expressed at the beginning of each paragraph.

Choosing where to position the topic sentence depends not only on your audience and purpose but also on the essay’s arrangement, or order. When you organize information according to order of importance, the topic sentence may be the final sentence in a paragraph. All the supporting sentences build up to the topic sentence. Chronological order may also position the topic sentence as the final sentence because the controlling idea of the paragraph may make the most sense at the end of a sequence.

When you organize information according to spatial order, a topic sentence may appear as the middle sentence in a paragraph. An essay arranged by spatial order often contains paragraphs that begin with descriptions. A reader may first need a visual in his or her mind before understanding the development of the paragraph. When the topic sentence is in the middle, it unites the details that come before it with the ones that come after it.

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs. For more information on topic sentences, please see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .

Developing topic sentences and thinking about their placement in a paragraph will prepare you to write the rest of the paragraph.

The paragraph is the main structural component of an essay as well as other forms of writing. Each paragraph of an essay adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related main idea is supported and developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one main idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be?

One answer to this important question may be “long enough”—long enough for you to address your points and explain your main idea. To grab attention or to present succinct supporting ideas, a paragraph can be fairly short and consist of two to three sentences. A paragraph in a complex essay about some abstract point in philosophy or archaeology can be three-quarters of a page or more in length. As long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In general, try to keep the paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than one full page of double-spaced text.

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

You may find that a particular paragraph you write may be longer than one that will hold your audience’s interest. In such cases, you should divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a topic statement or some kind of transitional word or phrase at the start of the new paragraph. Transition words or phrases show the connection between the two ideas.

In all cases, however, be guided by what you instructor wants and expects to find in your draft. Many instructors will expect you to develop a mature college-level style as you progress through the semester’s assignments.

To build your sense of appropriate paragraph length, use the Internet to find examples of the following items. Copy them into a file, identify your sources, and present them to your instructor with your annotations, or notes.

- A news article written in short paragraphs. Take notes on, or annotate, your selection with your observations about the effect of combining paragraphs that develop the same topic idea. Explain how effective those paragraphs would be.

- A long paragraph from a scholarly work that you identify through an academic search engine. Annotate it with your observations about the author’s paragraphing style.

Starting Your First Draft

Now we are finally ready to look over Mariah’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Mariah in the proper mind-set to start.

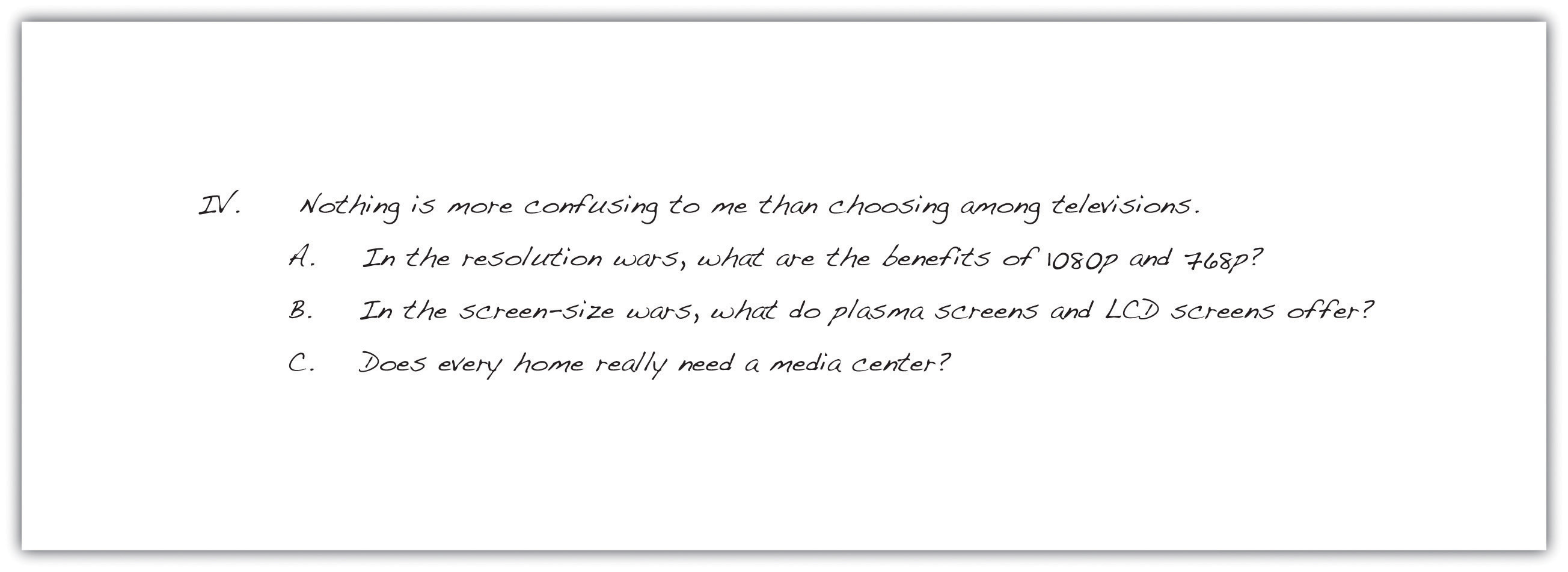

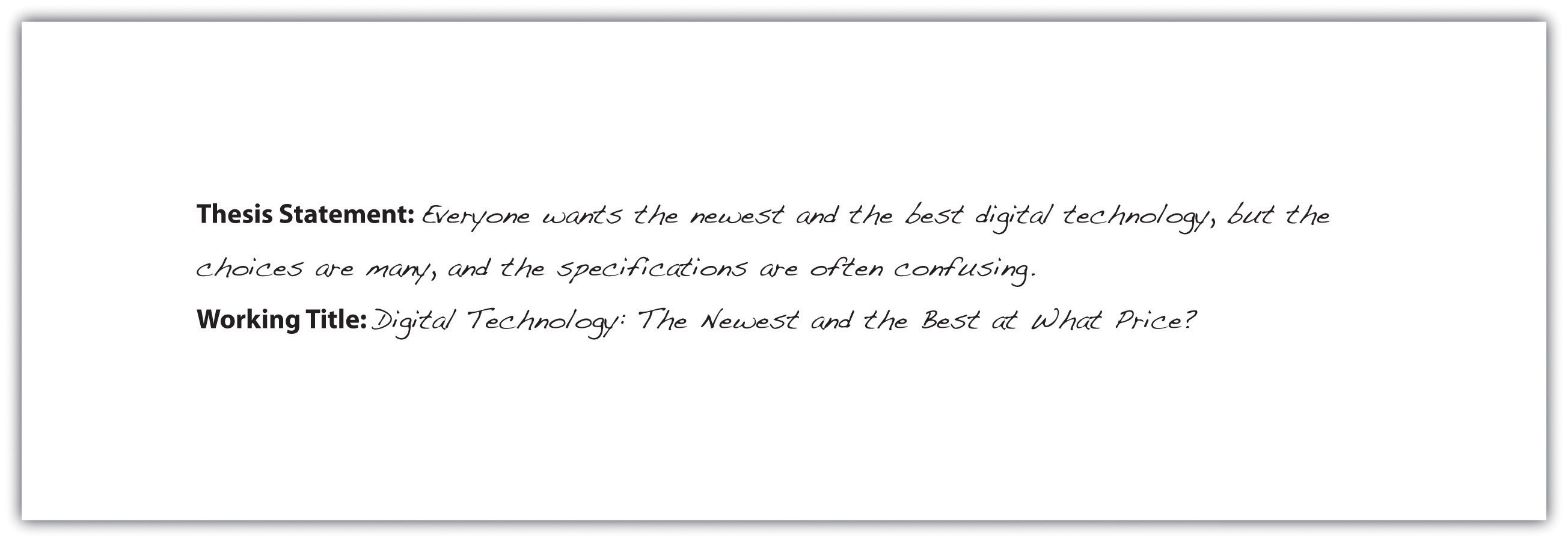

The following is Mariah’s thesis statement.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience.

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. You will read her introduction again in Section 8.4 “Revising and Editing” when she revises it.

Remember Mariah’s other options. She could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs.

You will learn more about writing attention-getting introductions and effective conclusions in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

With her thesis statement and her purpose and audience notes in front of her, Mariah then looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is the portion of her outline for the first body paragraph. The roman numeral II identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and arabic numerals label subpoints.

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

In your documents, observe any formatting requirements—for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters—that your instructor requires.

Study how Mariah made the transition from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then copy sentences from Mariah’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Continuing the First Draft

Mariah continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered subpoints in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of writing the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

Preceding each body paragraph that Mariah wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded roman numeral III from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

Mariah then began her third and final body paragraph using roman numeral IV from her outline.

Reread body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Mariah is writing. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In body paragraph two, Mariah decided to develop her paragraph as a nonfiction narrative. Do you agree with her decision? Explain. How else could she have chosen to develop the paragraph? Why is that better?

- Compare the writing styles of paragraphs two and three. What evidence do you have that Mariah was getting tired or running out of steam? What advice would you give her? Why?

- Choose one of these two body paragraphs. Write a version of your own that you think better fits Mariah’s audience and purpose.

Writing a Title

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Mariah crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Mariah finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph (you will read her conclusion in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” ). She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Writing Your Own First Draft

Now you may begin your own first draft, if you have not already done so. Follow the suggestions and the guidelines presented in this section.

Key Takeaways

- Make the writing process work for you. Use any and all of the strategies that help you move forward in the writing process.

- Always be aware of your purpose for writing and the needs of your audience. Cater to those needs in every sensible way.

- Remember to include all the key structural parts of an essay: a thesis statement that is part of your introductory paragraph, three or more body paragraphs as described in your outline, and a concluding paragraph. Then add an engaging title to draw in readers.

- Write paragraphs of an appropriate length for your writing assignment. Paragraphs in college-level writing can be a page long, as long as they cover the main topics in your outline.

- Use your topic outline or your sentence outline to guide the development of your paragraphs and the elaboration of your ideas. Each main idea, indicated by a roman numeral in your outline, becomes the topic of a new paragraph. Develop it with the supporting details and the subpoints of those details that you included in your outline.

- Generally speaking, write your introduction and conclusion last, after you have fleshed out the body paragraphs.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

The Wordling

The Wordling - The info and tools you need to live your best writing life.

How to Write a First Draft: 10 Tips for Reaching “The End”

The first draft is the most important phase of your project. Here’s how to keep it fast and fun.

By Natasha Khullar Relph

Do you know why so many writers freeze up the moment they sit down to write? The reason that the fear, the anxiety, and the uncertainty bubbles up and causes an otherwise articulate person to resist putting a single word on the page?

It’s perfectionism.

It’s the idea that what you’re writing now will be what the reader will see later.

This is almost never the case. Which is why, when it comes to writing, it’s important to begin simply: by thinking of any piece of work you’re doing as a first draft.

JUMP TO SECTION

What qualifies as a first draft How to write a first draft

- Make time for your writing

- Know your story before you start writing

- Write out of order

- Allow for imperfection

- Keep yourself accountable with goals and deadlines

- Eliminate distractions

- Practice writing in sprints

- Use the TK placeholder

- Don’t go back and fix things you’re changing

- Know your next step

Finish your first draft the easy way

What qualifies as a first draft?

A first draft or rough draft is the initial version of a piece of writing, whether it’s an essay, article, short story, or chapter in a nonfiction book or novel. The first draft is the initial output you create, with no extensive editing, revision, or proofreading.

First drafts are essential because they serve as the foundation upon which you can build and refine your work. They allow you to get your ideas down on the page without getting bogged down by perfectionism or self-criticism. Once you’ve completed a rough draft , you can review, revise, or edit your work to improve clarity, coherence, style, and overall quality.

Generally, a piece of writing can be considered a first draft if:

- It captures the writer’s initial thoughts and ideas.

- It covers the main points or themes, but lacks completeness.

- It may be rough and unpolished, with errors in grammar and style.

- The organization and structure might be loose or imperfect.

- Annotations and comments for self-improvement may be present.

- It may contain inconsistencies, both in content and style.

- The primary focus is on getting ideas down rather than perfection.

How to write a first draft

“I believe the first draft of a book —even a long one—should take no more than three months,” says New York Times bestselling author Stephen King , and we tend to agree. A first draft is nothing but a way of taking the ideas in your head and putting them on the page. We’ll give them shape later. Right now, for the first draft, the goal is simply to have them exist as fast as possible .

Here are some strategies, techniques and writing tips that will make it easier to transform your ideas into words on the page.

1. Make time for your writing

No one—and I do mean no one—writes the first draft of anything without some serious arse in chair time . (Yes, that’s the technical term.)

Want to write more? Want to write faster? Put your arse in the chair as often as you can, for as long as you can.

Now, this might not always be possible. You might have a full-time job, kids, and other responsibilities that come in the way of your writing. Regardless, if you want to finish your first draft, you’re going to have to schedule writing time . Establish a routine that aligns with your goals and guard that time fiercely. Some ideas for how to do that:

- Set clear priorities: Recognize the importance of your writing and prioritize it in your daily life. Create a regular writing routine, whether it’s daily, weekly, or on specific days.

- Wake up early or stay up late: Consider waking up an hour earlier in the morning or, if you’re like me, staying up after everyone’s gone to bed, to get a few uninterrupted hours of writing time.

- Use your lunch breaks: If you have a full-time job, see if you can use part of your lunch break for writing. If you work from home , treat the time you may have spent commuting as “found time” and use it to put some words on the page.

- Weekend retreats: If time and budget allow, consider going on a weekend retreat for a solid block of writing time. If going away isn’t an option, perhaps you can have a makeshift retreat of your own at home.

- Plan ahead: Try to schedule writing time in advance to ensure it doesn’t get overshadowed by other commitments. If you have children , arrange childcare during your writing hours. The more you can delegate non-essential tasks or chores, the more writing time you can free up.

2. Know your story before you start writing

While it’s tempting to just open a blank page and start writing, this is the most difficult and inefficient way to write a first draft. That’s not to say that you can’t be a pantser—someone who writes without an outline and by the seat of their pants (hence the name)—but knowing what you want to say makes it infinitely easier for you to actually say it.

It’s crucial to have a clear understanding of your story , no matter whether you’re a novelist, a screenwriter, a short story writer, or journalist. And knowing your story, including your main characters, is essential for a successful drafting process , especially if this is your first book or first novel.

Here are some aspects of your work that are helpful to know before you begin writing:

- Purpose and message: Knowing your story’s purpose and central message provides you with a compass to navigate the writing process. Are you aiming to entertain, inform, persuade, or provoke thought? This clarity guides your decisions throughout the first draft stage.

- Characters: Understanding your characters’ backgrounds, motivations, and arcs allows you to breathe life into them on the page. It enables you to craft multidimensional characters with authentic reactions and growth.

- Plot structure: Knowing the overarching plot and its key events helps you maintain a cohesive and engaging narrative, whether you’re brainstorming or world building. You can create foreshadowing, build tension, and ensure that each scene contributes to the story’s progress when you know where you’re heading.

- Themes: Identifying the themes and vibes you want to explore allows you to weave them into your narrative seamlessly. Themes add depth to your story and provide readers with thought-provoking ideas.

3. Write out of order

The conventional approach to writing a first draft involves starting at the beginning and progressing sequentially to the end. While this method works well for many writers, it’s not the only path to a successful final product. In fact, you may find that it might work better for your writing process to write out of order.

Here’s why this unconventional approach works:

- Overcoming writer’s block: The frustration of staring at a blank page can be paralyzing. Writing out of order allows you to sidestep this roadblock. If you’re feeling stuck on an introduction or a particular chapter, don’t let it hinder your progress. Instead, jump to a body paragraph or different section of your work that excites you. By doing this, you keep your creative juices flowing and maintain momentum.

- Capturing ideas as they come: Inspiration often strikes at unpredictable moments. You might have a brilliant idea for the conclusion of your podcast episode, the climax of your novel, or the final argument in your thesis statement long before you reach that point in your rough draft. By writing out of order, you can capture these ideas while they’re fresh and vivid, ensuring you don’t forget them.

- Building the core of your work: Sometimes, you may have a clear vision of the central themes, arguments, or emotional arcs of your work before you have all the details in place. In such cases, writing these pivotal sections first can provide a strong foundation upon which you can build the rest of your narrative.

- Flexibility and experimentation: Writing out of order gives you the freedom to experiment with different writing styles, tones, or perspectives. Whether you’re a screenwriter exploring various character interactions or a novelist tackling non-linear storytelling, this approach allows you to explore diverse creative avenues without feeling confined by chronological constraints.

- Maintaining enthusiasm: The creative writing process can be a long and demanding journey. Writing out of order allows you to maintain enthusiasm by working on the parts of your work that excite you the most. This enthusiasm can get you through the messy middle when you’re in the thick of it and questions about why you’re even doing this begin to surface.

4. Allow for imperfection

Listen, you’re not going to get it right the first time. So stop expecting that of yourself.

The first draft, as I mentioned before, is the draft whose sole purpose is to take something out of your head and make it exist on the page. Typos are fine! Your word choices will change! There is no bad thing you can do in this draft that cannot be changed, revised, or edited out.

Your only goal when writing the first draft is to take those ideas from your head and turn them into words on the page. There will be other drafts—a second draft, a third draft, a final draft—that will start bringing order to this material and mould it into shape. But you can’t give shape to something that doesn’t exist.

So use this draft to get everything out of your head and on to the page. Then you can either self-edit or work with beta readers or professional editors to take it further.

5. Keep yourself accountable with goals and deadlines

I’m willing to bet my favorite writing pen that half the writing that exists in the world today wouldn’t have been committed to page if there wasn’t a frustrated editor breathing down a writer’s neck with a can’t-be-missed deadline. While it’s unlikely you’ll have an editor for your fiction writing, at least at first, you can keep yourself accountable by setting your own deadlines . Here’s what you need to keep in mind when doing so:

- Define clear goals: Set specific, measurable, and achievable writing goals . These could include word count targets, chapter outlines, research milestones, or deadlines for submitting work to editors or publishers.

- Break down larger goals: For larger projects, like novel writing or research papers, break them down into smaller chunks. Set deadlines for completing each section or chapter. This will prevent you from feeling overwhelmed and can help you make steady progress.

- Set and honor deadlines: Give yourself deadlines for completing specific writing tasks. These deadlines can be self-imposed or align with external submission requirements. However, it’s imperative that you treat these deadlines with the same seriousness that you would a deadline from an editor or publisher.

- Track progress: Regularly review your progress. Make sure to celebrate your achievements, even small ones, to stay motivated and keep writing.

6. Eliminate distractions

You can’t write if you can’t concentrate. And you can’t concentrate if you have notifications going off every two minutes, a child knocking on your door because they’re hungry and need a snack, or you can’t resist the urge to see what Taylor Swift’s been up to Instagram.

The very first thing you need to do once you’ve committed to finishing your first draft is to create space in your life for your writing to happen and minimize or eliminate any distractions. Here’s how:

- Turn off notifications: Silence your phone, mute social media notifications, and close irrelevant tabs or apps on your computer. These constant pings and alerts can pull you away from your writing flow.

- Set clear boundaries: If you share your writing space with others, communicate your need for uninterrupted time. Let family members, roommates, or colleagues know when you’ll be writing and request their cooperation.

- Use website blockers: If you find yourself succumbing to the temptation of browsing the Internet during writing sessions, consider using website blockers or productivity apps that restrict access to distracting websites for a set period.

- Declutter your workspace: A clutter-free environment can lead to a clutter-free mind. Organize your writing area and keep it tidy to minimize visual distractions.

- Use noise-cancelling headphones: If you’re in a noisy environment, invest in noise-cancelling headphones to block out external sounds and create a more serene writing atmosphere.

7. Practice writing in sprints

Writing sprints or word sprints are short, focused bursts of writing where you set a timer and write as much as you can during that specific timeframe. These sprints can vary in length, but common durations include 10, 15, or 20 minutes.

The key is to commit to uninterrupted writing during the sprint, without editing or revising as you go. Writing sprints are about getting words on the page, not perfecting them.

Writing sprints work for a few reasons:

- They create a sense of urgency, reducing the temptation to procrastinate or endlessly revise.

- The time constraint of a sprint encourages heightened concentration, leading to increased productivity.

- Sprints break writing tasks into manageable chunks, allowing for consistent and measurable progress.

- They make the process of writing more time-efficient by emphasizing output over perfection.

- Practicing writing in sprints provides a structured approach to improving writing skills and becoming a better writer.

8. Use the TK placeholder

Using the “TK” placeholder is a technique that English-language journalists often use to maintain their writing flow and avoid getting stuck when they can’t immediately recall a specific detail or need to insert additional information. TK, which stands for to come , is an acknowledgement that there’s a gap or missing content that requires attention.

Once your initial draft is complete, you can revisit these TK placeholders and add in all relevant or missing information.

9. Don’t go back and fix things you’re changing

Resist, I repeat, resist the temptation to go back and fix things as you write. This urge to rewrite is especially strong in new writers, who feel they must make what they’ve written perfect, or even legible, before they can move on to the next section.

Here’s the thing: What you’re writing will change. And if you’re making big changes, like renaming a character, changing the point of view, or expanding the time period, they will affect the parts of the book you’ve already written. However, by going back and making those changes now, you’re creating extra work for yourself for two reasons:

- You may implement the changes and write in a new point of view or a different period of time only to find that it doesn’t really work. If you decide to revert changes, you’ll have to go back and fix your entire novel again .

- There are still many decisions you’ll make as your story moves forward that will continue to impact the beginning. It’s far better to write the first draft all the way through and see how it ends before going back to implement any changes. There may be far more—or less—than what you expected.

That’s a job for the editing process. For the phase you’re in right now, the goal is simply to get to The End. So turn off track changes, focus on your own first draft, and keep writing and moving forward step by step until you get there.

10. Know your next step

You don’t—and can’t—know how the whole thing will end. The best you can do at any point during the writing of the first draft is to know the next step.

Much like a hiker navigating through dense woods, you can’t see the entire trail from the starting point, but you can identify the next marker or landmark. Similarly, in writing, you may not have the entire plot or structure of your story mapped out, but you can always figure out the next sentence, paragraph, or scene that needs to be written.

And when you’re writing the first draft? That’s all you need to know.

Learn how to finish your first draft the easy way

The first draft of a book should take no more than three months to finish, as the great Stephen King suggests, but for most authors, it can end up being a multi-year challenge.

If you’re tired of the struggle and eager to finish that writing project you’ve poured your heart and soul into, we’re here to show you an easier way. Learn how you can finish your first draft in just 90 days with Finish That Damn Book, one of the 20+ courses available through Wordling Plus. Get started here with a 7-day free trial.

FREE RESOURCE:

MASTERCLASS: The $100K Blueprint for Multipassionate Writers

In this masterclass, I’m going to give you a step-by-step strategy to build multiple sources of income with your creative work in less than a year.

If you’ve been told you need to focus on one thing in order to succeed, this class will be an eye-opener. Watch it here.

Natasha Khullar Relph

Founder and Editor, The Wordling

Natasha Khullar Relph is an award-winning journalist and author with bylines in The New York Times, TIME CNN, BBC, ABC News, Ms. Marie Claire, Vogue, and more. She is the founder of The Wordling , a weekly business newsletter for journalists, authors, and content creators. Natasha has mentored over 1,000 writers , helping them break into dream publications and build six-figure careers. She is the author of Shut Up and Write: The No-Nonsense, No B.S. Guide to Getting Words on the Page and several other books .

Sign up for The Wordling

Writing trends, advice, and industry news. Delivered with a cheeky twist to your Inbox weekly, for free.

Writing a First Draft

Now that you have a topic and/or a working thesis, you have several options for how to begin writing a more complete draft.

Just write. You already have at least one focusing idea. Start there. What do you want to say about it? What connections can you make with it? If you have a working thesis, what points might you make that support that thesis?

Make an outline. Write your topic or thesis down and then jot down what points you might make that will flesh out that topic or support that thesis. These don’t have to be detailed. In fact, they don’t even have to be complete sentences (yet)!

Begin with research. If this is an assignment that asks you to do research to support your points or to learn more about your topic, doing that research is an important early step (see the section on “ Finding Quality Texts ” in the “Information Literacy” section). This might include a range of things, such as conducting an interview, creating and administering a survey, or locating articles on the Internet and in library databases.

Research is a great early step because learning what information is available from credible sources about your topic can sometimes lead to shifting your thesis. Saving the research for a later step in the drafting process can mean making this change after already committing sometimes significant amounts of work to a thesis that existing credible research doesn’t support. Research is also useful because learning what information is available about your topic can help you flesh out what you might want to say about it.

Essay Structure

You might already be familiar with the five-paragraph essay structure, in which you spend the first paragraph introducing your topic, culminating in a thesis that has three distinct parts. That introduction paragraph is followed by three body paragraphs, each one of those going into some detail about one of the parts of the thesis. Finally, the conclusion paragraph summarizes the main ideas discussed in the essay and states the thesis (or a slightly re-worded version of the thesis) again.

This structure is commonly taught in high schools, and it has some pros and some cons.

- It helps get your thoughts organized.

- It is a good introduction to a simple way of structuring an essay that lets students focus on content rather than wrestling with a more complex structure.

- It familiarizes students with the general shape and components of many essays—a broader introductory conversation giving readers context for this discussion, followed by a more detailed supporting discussion in the body of the essay, and ending with a sense of wrapping up the discussion and refocusing on the main idea.

- It is an effective structure for in-class essays or timed written exams.

- It can be formulaic—essays structured this way sound a lot alike.

- It isn’t very flexible—often, topics don’t lend themselves easily to this structure.

- It doesn’t encourage research and discussion at the depth college-level work tends to ask for. Quite often, a paragraph is simply not enough space to have a conversation on paper that is thorough enough to support a stance presented in your thesis.

So, if the five-paragraph essay isn’t the golden ticket in college work, what is?

That is a trickier question! There isn’t really one prescribed structure that written college-level work adheres to—audience, purpose, length, and other considerations all help dictate what that structure will be for any given piece of writing you are doing. Instead, this text offers you some guidelines and best practices.

Things to Keep in Mind about Structure in College-Level Writing

Avoid the three-point structure.

Aim for a thesis that addresses a single issue rather than the three-point structure. Take a look at our example from the previous section, “ Finding the Thesis ”:

“Katniss Everdeen, the heroine of The Hunger Games, creates as much danger for herself as she faces from others over the course of the film.”

This thesis allows you to cover your single, narrow topic in greater depth, so you can examine multiple sides of a single angle of the topic rather than having to quickly and briefly address a broader main idea.

There’s No “Right” Number of Supporting Points

There is no prescribed number of supporting points. You don’t have to have three! Maybe you have two in great depth, or maybe four that explore that one element from the most salient angles. Depending on the length of your paper, you may even have more than that.

There’s More than One Good Spot for a Thesis

Depending on the goals of the assignment, your thesis may no longer sit at the end of the first paragraph, so let’s discuss a few places it can commonly be found in college writing.

It may end up at the end of your introductory information—once you’ve introduced your topic, given readers some reasonable context around it, and narrowed your focus to one area of that topic. This might put your thesis in the predictable end-of-the-first-paragraph spot, but it might also put that thesis several paragraphs into the paper

Some college work, particularly work that asks you to consider multiple sides of an issue fully, lends itself well to an end-of-paper thesis (sometimes called a “delayed thesis”). This thesis often appears a paragraph or so before the conclusion, which allows you to have a thorough discussion about multiple sides of a question and let that discussion guide you to your stance rather than having to spend the paper defending a stance you’ve already stated.

These are some common places you may find your thesis landing in your paper, but a thesis truly can be anywhere in a text.

Writing Beginnings

Beginnings have a few jobs. These will depend somewhat on the purpose of the writing, but here are some of the things the first couple of paragraphs do for your text:

- They establish the tone and primary audience of your text—is it casual? Academic? Geared toward a professional audience already versed in the topic? An interested audience that doesn’t know much about this topic yet?

- They introduce your audience to your topic.

- They give you an opportunity to provide context around that topic—what current conversations are happening around it? Why is it important? If it’s a topic your audience isn’t likely to know much about, you may find you need to define what the topic itself is.

- They let you show your audience what piece of that bigger topic you are going to be working with in this text and how you will be working with it.

- They might introduce a narrative, if appropriate, or a related story that provides an example of the topic being discussed.

Take a look at the thesis about Katniss once more. There are a number of discussions that you could have about this film, and almost as many that you could have about this film and its intersections with the concept of danger (such as corruption in government, the hazards of power, risks of love or other personal attachments, etc.). Your introduction moving toward this thesis will shift our attention to the prevalence of self-imposed danger in this film, which will narrow your reader’s focus in a way that prepares us for your thesis.

The most important thing at this point in the drafting process is to just get started, but when you’re ready, if you want to learn more about formulas and methods for writing introductions, see “ Writing Introductions ,” presented later in this section of the text.

Writing Middles

Middles tend to have a clearer job—they provide the meat of the discussion! Here are some ways that might happen:

- If you state a thesis early in the paper, the middle of the paper will likely provide support for that thesis.

- The middle might explore multiple sides of an issue.

- It might look at opposing views—ones other than the one you are supporting—and discuss why those don’t address the issue as well as the view you are supporting does.

Let’s think about the “multiple sides of the issue” approach to building support with our Hunger Games example. Perhaps Katniss may not see a particular dangerous situation she ends up in as being one she’s created, but another character or the viewers may disagree. It might be worth exploring both versions of this specific danger to give the most complete, balanced discussion to support your thesis.

Writing Endings

Endings, like beginnings, tend to have more than one job. Here are some things they often need to do for a text to feel complete:

- Reconnect to the main idea/thesis. However, note that this is different than a simple copy/paste of the thesis from earlier in the text. We’ve likely had a whole conversation in the text since we first encountered that thesis. Simply repeating it, or even replacing a few key words with synonyms, doesn’t acknowledge that bigger conversation. Instead, try pointing us back to the main idea in a new way.

- Tie up loose ends. If you opened the text with the beginning of a story to demonstrate how the topic applies to average daily life, the end of your text is a good time to share the end of that story with readers. If several ideas in the text tie together in a relevant way that didn’t fit neatly into the original discussion of those ideas, the end may be the place to do that.

- Keep the focus clear—this is your last chance to leave an impression on the reader. What do you want them to leave this text thinking about? What action do you want them to take? It’s often a good idea to be direct about this in the ending paragraph(s).

How might we reconnect with the main idea in our Hunger Games example? We might say something like, “In many ways, Katniss Everdeen is her own greatest obstacle to the safe and peaceful life she seems to wish for.” It echoes, strongly, the original thesis, but also takes into account the more robust exploration that has happened in the middle parts of the paper.

As mentioned about writing introductions above, the most important thing at this point in the drafting process is to just get started (or in this case, to get started concluding), but when you’re ready, if you want to learn more about formulas and methods for writing conclusions, see “ Writing Conclusions ,” presented later in this section of the text.

The Word on College Reading and Writing Copyright © by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Write the First Draft

Part 4: How to Write the First Draft

Introduction

By this stage, you will have a final essay plan and a research document that presents your findings from the research stage in an organised and easy-to-use way. Together, these documents provide a clear map and all the information you need to write a well-structured essay , in a fraction of the time it would otherwise take.

This timesaving comes from the fact that you have already made all the big decisions about your essay during the research phase:

- You have a clear idea of your answer to the essay question.

- You know the main topics you will discuss to support your answer.

- You know the best order in which to discuss these topics.

- You know how many words should be spent on these topics, based on their importance to supporting your answer.

- You know what points you will make under each topic and will discuss each of these in a new paragraph.

- You know exactly what information each paragraph of your essay should contain.

You have already compiled your list of references or bibliography, and have easy access to all the details you need to correctly cite and reference your work.

Formal academic language

Before starting to write your essay, you must understand that using formal academic language is essential when writing at university. Formal academic language is clear and concise. You should never use 20 words when 10 will do; and your writing should leave no room for misunderstanding or confusion.

First person should almost always be avoided when writing an essay; however, it is recommended that you check with your tutor or lecturer about their attitude towards the first person and when it should be used, if ever. Conversely, contractions (e.g. shouldn’t, could’ve, he’s and hasn’t) are always inappropriate in academic writing. The only time you should see a contraction in academic text is in a direct quotation, usually taken from informal or spoken text.

Care should be taken to craft grammatically correct sentences, with no errors of spelling or punctuation. Colloquialisms and idiomatic language should be avoided. (These are characteristics of informal or spoken language.) It is also important to avoid racist, sexist and gender-specific language in your writing. Instead, use inclusive and gender-neutral vocabulary. For more information, please see our blog article ‘ Simplicity in Academic Writing ’.

Introductions

As you already have a clear idea of what your essay will include, you can write your introduction first. Of course, you should always come back to your introduction at the end of writing your essay to make sure that it definitely introduces all the topics you discussed. (You should not discuss any topics in the body of your essay that you have not mentioned in the introduction.)

Some other points to remember when writing your introduction are that you need to clearly state your answer to the essay question (your thesis statement), not just introduce the question. Also, your introduction should include no information that is not directly relevant to your topic. Including irrelevant background information in the introduction is a common mistake made by novice academic writers.

See the following example of a poor introduction. Then, compare it with the example of a good introduction below that. These example introductions are for the same 1,000-word essay used for the examples given in earlier stages of this guide, ‘How to Begin’ and ‘How to Organise Your Research’.

This is an example of a poor introduction: In 1492, Columbus set sail from Spain on a quest to find a new trade route to Asia. Despite the fact that he believed he had landed in the East Indies, Columbus had found another continent entirely. This essay will examine the issue of whether or not indigenous culture was completely decimated in the Americas as a result of Spain’s colonisation in the 16th century. It will look at the areas of family, religion and language.

This is an example of a good introduction: Beginning in the sixteenth century, Spanish colonisation of the Americas had a significantly negative effect on the cultural practices of the indigenous population. In particular, the introduction of new diseases and the consequent demographic collapse dramatically weakened indigenous culture and their ability to resist Spanish domination. However, aspects of the culture of some indigenous groups survived and even thrived—it was not completely decimated. Through an examination of the evidence related to religion, family and language, including the effects of colonisation on these areas of society, this essay will demonstrate aspects of indigenous beliefs, customs and practices that managed to endure.

In the example of a poor introduction, background information is included that is not directly relevant to the topic. Also, it does not answer the question, it only introduces it. Finally, it does not introduce all the topics to be discussed (as outlined in the final essay plan), and for those it does introduce, it does not mention them in the order they will be discussed in the essay (as outlined in the final essay plan).

By contrast, the good introduction provides a clear thesis statement; introduces, in order, all the topics to be discussed; and only includes information that is directly relevant to the essay question.

Topic sentences

As explained in ‘How to Begin’, every paragraph needs a topic sentence. The topic sentence introduces the new topic about to be discussed. It also links the topic back to the essay question, to make it clear why it is relevant and how it advances your argument.

The following are examples of topic sentences for Topic 1 ‘Disease and demographic impact’, Topic 2 ‘Religion’ and Topic 4 ‘Language’, as outlined in the final essay plan in ‘How to Finalise Your Essay Plan’. Notice how they link back to the thesis statement: ‘Spain’s colonisation had a significantly negative effect on the indigenous population of the Americas but some aspects of the culture of some indigenous groups survived and even thrived—it was not completely decimated’.

Topic 1: One of the most obvious negative effects of colonisation was the introduction of diseases that caused rapid demographic collapse among the indigenous population. Topic 2: Missionaries arrived to preach Catholicism to the Native Americans, but they allowed the Native Americans to keep parts of their culture and religion that did not clash with Catholic value and traditions. Topic 4: The Spanish did not force their language on the Native Americans, but there were nonetheless cases of indigenous languages fading out of use and being replaced with Spanish.

A common misconception is that your paragraphs need a concluding sentence for each topic. This is not true, and in fact results in unnecessary repetition, especially in a short essay.

If you have carefully followed the steps outlined in the articles on organising your research and finalising your essay plan, your final essay plan should clearly indicate what information will go in each paragraph of your essay. Each paragraph should contain only one main idea. Care should also be taken to only spend as many words as planned on each paragraph. If you decided in your research and planning stages that 150 words were enough to discuss a certain topic, then stick as closely to that plan as possible. Likewise, unless you have a very good reason for doing otherwise, follow your planned order of paragraphs, as that order should reflect the most logical arrangement and help your essay to flow well.

When writing your paragraphs, you want to choose the best supporting evidence and examples from your research to use. You must also ensure that you are inserting the necessary in-text citations and compiling your final reference list as you are writing, rather than leaving this until the end. This should be easy to do, as all these details are readily available in your research document (see ‘How to Organise Your Research’).

Conclusions

As explained in ‘How to Begin’, a conclusion should restate the thesis statement and summarise the points that were made in the body of the essay in the order in which they were made. The conclusion offers an important opportunity to synthesise the points you have made to support your argument and to reinforce how these points prove that your argument is correct. In many ways, the conclusion is a reflection of the introduction, but it is important that it is not an exact repeat of it. A key point of difference is that you have already provided ample evidence and support for your answer to the essay question, so the purpose of your conclusion is not to introduce what you will say, but rather to reiterate what you have said. Further, your conclusion absolutely must not contain any new material not already discussed in detail in the body of your text.

Referencing

It is important that you acknowledge your sources of information in your academic writing. This allows you to clearly show how the ideas of others have influenced your own work. You should provide a citation (and matching reference) in your essay every time you use words, ideas or information from other sources. In this way, you can avoid accidental plagiarism.

Referencing also serves other purposes. It allows you to demonstrate the depth and breadth of your research, to show that you have read and engaged with the ideas of experts in your field. It also allows you to give credit to the writers from whom you have borrowed words or ideas. For your reader, referencing allows them to trace the sources of information you have used, to verify the validity of your work. Your referencing must be accurate and provide all necessary details to allow your reader to locate the source.

Whether you have been provided referencing guidelines to follow, or have selected guidelines that you consider appropriate for your field, these must be followed closely, correctly and consistently. All work that is not 100% your own should be referenced, including page numbers where necessary (see ‘How, When and Why to Reference’). Your referencing should be checked carefully at the end of writing to ensure that everything that should have been referenced has been referenced, all in-text citations have corresponding reference list entries and the reference list or bibliography is correctly ordered.

Your document should be neatly and consistently formatted, following any guidelines provided by your tutor or lecturer. Neat formatting shows that you have taken pride in your work and that you understand the importance of following convention.

If no guidelines have been provided to you, we recommend you use the following formatting guidelines:

- normal page margins

- 12 pt Times New Roman or Arial font for the body (10 pt for footnotes)

- bold for headings

- 1.5 or double line spacing for the body (single spacing for footnotes)

- a line between each paragraph (or a first line indent of 1.27 cm for each paragraph).

These are the guidelines most commonly preferred by Australian and New Zealand universities.

Learning how to write your first draft can feel overwhelming. To solidify your knowledge, you might like to watch Dr Lisa Lines' video on the topic on our YouTube channel . If you need any further assistance, you can read more about our professional editing service . Capstone Editing is always here to help.

Related Guides

Essay writing: everything you need to know and nothing you don’t—part 1: how to begin.

This guide will explain everything you need to know about how to organise, research and write an argumentative essay.

Essay Writing Part 2: How to Organise Your Research

Organising your research effectively is a crucial and often overlooked step to successful essay writing.

Essay Writing Part 3: How to Finalise Your Essay Plan

The key to successful essay writing is to finalise a detailed essay plan, carefully refined during the research stage, before beginning to write your essay.

Part 5: How to Finalise and Polish Your Essay

Before handing in any assignment, you must take the time to carefully edit and proofread it. This article explains exactly how to do so effectively.

Writing Center: The First Draft

- How to Set Up an Appointment Online

- Documentation Styles

- Parts of Speech

- Types of Clauses

- Punctuation

- Spelling & Mechanics

- Usage & Styles

- Resources for ESL Students

- How to Set up an APA Paper

- How to Set up an MLA Paper

- Adapt to Academic Learning

- Audience Awareness

- Learn Touch Typing

- Getting Started

- Thesis Statement

- The First Draft

- Proofreading

- Writing Introductions

- Writing Conclusions

- Chicago / Turabian Style

- CSE / CBE Style

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Cross-Cultural Understanding

- Writing Resources

- Research Paper - General Guidelines

- Annotated Bibliographies

- History Papers

- Science Papers

- Experimental Research Papers

- Exegetical Papers

- FAQs About Creative Writing

- Tips For Creative Writing

- Exercises To Develop Creative Writing Skills

- Checklist For Creative Writing

- Additional Resources For Creative Writing

- FAQs About Creating PowerPoints

- Tips For Creating PowerPoints

- Exercises to Improve PowerPoint Skills

- Checklist For PowerPoints

- Structure For GRE Essay

- Additional Resources For PowerPoints

- Additional Resources For GRE Essay Writing

- FAQs About Multimodal Assignments

- Tips For Creating Multimodal Assignments

- Checklist For Multimodal Assignments

- Additional Resources For Multimodal Assignments

- GRE Essay Writing FAQ

- Tips for GRE Essay Writing

- Sample GRE Essay Prompts

- Checklist For GRE Essays

- Cover Letter

- Personal Statements

- Resources for Tutors

- Chapter 2: Theoretical Perspectives on Learning a Second Language

- Chapter 4: Reading an ESL Writer's Text

- Chapter 5: Avoiding Appropriation

- Chapter 6: 'Earth Aches by Midnight': Helping ESL Writers Clarify Their Intended Meaning

- Chapter 7: Looking at the Whole Text

- Chapter 8: Meeting in the Middle: Bridging the Construction of Meaning with Generation 1.5 Learners

- Chapter 9: A(n)/The/Ø Article About Articles

- Chapter 10: Editing Line by Line

- Chapter 14: Writing Activities for ESL Writers

- Resources for Faculty

- Writing Center Newsletter

- Writing Center Survey

First Draft

T he importance of the first draft is to test your outline and structure to see if they work. As you start your first draft, do not get caught up on the details just yet. Do not worry about having the most creative Introduction or a fully developed argument. It is very rare that a writer will write the perfect draft on the first try. The importance of the first draft is to try to get your ideas out based on the outline you have created. It serves as a reference point to build off of for your later drafts.

The Introduction