8 Tips for How to Thrive as a Nurse With ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) affects both men and women but in different ways. Due to the differences, women are often underdiagnosed or diagnosed late in life, which can be a barrier to treatment, a sense of understanding, and the ability to find community.

An underdiagnosis of ADHD significantly affects careers where women make up the majority of the workforce, which includes nursing. In 2021, 82.5% of nurses were women.

While ADHD poses challenges, people with ADHD typically have other skills, including:

- High levels of empathy

- Spontaneity

- High levels of courage

- Being able to hyper-focus on a task

On this page, we share the experiences of one nurse with ADHD, how she tackled school, and how she thrives today as a nurse.

Molly Foss is a registered nurse at a level 1 trauma center. She was diagnosed with ADHD when she was 29.

Foss didn’t answer the call to be a nurse right out of high school. She felt intimidated by the work, so she pursued something else first.

“When I realized that wasn’t working, I was very intimidated to go back to school,” she says. “I finally realized that it’s all just a series of small steps.”

How to Thrive as a Nurse or Nursing Student With ADHD

Nursing students with ADHD must find strategies to help them study and absorb the material. Many of those same strategies can be used after graduation to stay up to date with research and nursing procedures. Before you can develop strategies, you must have a grasp of your own limitations and needs, which may be different than others with ADHD.

Self-awareness is the first step to creating tactics that help overcome your specific challenges. Foss has discovered that the medication prescribed to her is her No. 1 asset.

“Taking my medication is like putting on my glasses in the morning,” she says. “Everything goes from equally foggy and blurry to clear and obvious.”

While medication can help, lifestyle changes are what contribute to finding your groove with ADHD and maintaining it.

Foss also has created an assignment sheet. The sheet has tick boxes for most of the information she must track for patient care during her shift.

“More neurotypical people make their sheet on a blank piece of paper, I assume, because their brain is more organized,” she says. “My brain isn’t so organized, which is why I need my report sheet to be over-organized with a spot for everything.”

8 Tips for Nursing Students and Nurses With ADHD

Students and nurses with ADHD may help reduce the frustration and challenges accompanying the diagnosis by using tips and tricks others have discovered. These tips can be used independently or combined. They might also inspire another strategy that helps you in school, at work, or in your daily activities.

1. Use Flashcards

Students find consistent, repetitive exposure to information can help retention. Flashcards are a quick way to test yourself while involved in other activities. Movement and altering the environment can help to engage your brain in learning. Consider flashcards while eating, playing games, or when you’re out for a walk.

2. Change Your Environment

Students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder find studying in the same environment for an extended period of time challenging. Consider moving your study space every hour or two. Don’t limit this space to the library or your home. Instead, include a coffee shop, park, restaurant, or a student lounge on campus.

Anywhere you can sit and comfortably study is fair game.

3. Ask for Help

Contact the school’s office for students with disabilities. You’ll need documentation of your diagnosis but this will give you access to accommodations that can help you succeed in school.

“One of the students in my class was allowed to take tests in a quiet room so they wouldn’t be distracted by everyone else,” Foss says.

4. Seek Out Resources

Students and working nurses need access to resources that help increase their level of success and to better understand ADHD, its origins, and its impacts. ADDitude magazine is one resource Foss recommends. Reading the articles helped her feel seen and not ignored by society. The magazine is full of resources, tips, and stories for adults with ADHD and parents with children who have ADHD.

Additionally, Dr. Gabor Maté, who has ADHD himself, authored “Scattered,” which helps readers understand their ADHD diagnosis, the origins of ADHD, and how to heal and reduce the impacts of ADHD.

5. Try the Pomodoro Technique

This strategy works with the short attention span that many people with ADHD experience. The Pomodoro Technique is a time management tool that sets a 25-minute limit on the amount of time you work on any assignment before taking a scheduled five-minute break. After the fourth break, you schedule a longer 15- to 30-minute break. Of course, you can alter the 25-minute work time to fit your personal needs without extending it past 30 minutes.

6. Practice Flexibility and Self-Compassion

No one is a robot. It’s important to recognize when you may be hyper-focused or highly productive. Take this time to work on projects that require more brainpower.

When you have trouble focussing, have self-compassion and use the time to relax or work on something that doesn’t require as much attention, such as creating flashcards. The trick is to be flexible with your schedule to work with your flow of attention and not against it.

4. Create Structure

New nursing students may enjoy the lack of structure and freedom they experience as a first-year college student. But for students with ADHD it can be a recipe for disaster. Instead, create your own structure for studying and develop an accountability system, so you aren’t on your own. Don’t forget to include downtime and recreational activities. They are important for your mental health.

5. Consider Treatment

Many with ADHD find that medication helps calm their mind and allows them to focus productively on tasks necessary for school and work. Many of the medications used are stimulants, yet they help people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder function calmly and sleep better.

Additionally, cognitive behavioral therapy and environment modification can ease symptoms and help you cope better.

6. Prioritize Your Treatment

You can’t take care of your patients, family, or life if you aren’t taking care of yourself. Set an alarm to take your medication on time, create and stick with coping strategies that help you at school or work, and connect with others who have ADHD.

When you feel understood and appreciated for who you are, it can help raise your motivation to care for yourself so you can care for others.

7. Clear Your Mind

Frequently stopping what you’re doing to address an idea or thought that popped into your mind can mess up your day and impact patient care. Instead, carry a small notepad or your cell phone where you can write down the idea and address it later when you don’t have so much on your plate.

8. Take Things One Step at a Time

Just out of high school, Foss felt a calling to be a nurse. Terrified of the schooling and being able to work as a nurse, she chose to do something else. She soon realized the career wasn’t working but figured out that changing was really only a series of small steps.

“Right out of high school, I told people I wasn’t going to a university because I ‘didn’t have a four-year attention span.’ Now I have two two-year degrees and my BSN. Take the first step, even if it’s scary,” she says.

How ADHD Impacts Nurses and Nursing Students

The symptoms and manifestations of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults can differ from those in children. Adults not diagnosed in childhood may not seek support at work or school. Yet, up to 5% of adults have ADHD, affecting their relationships and ability to function at work and home. This number is likely underreported.

How ADHD Shows Up

Without tools to cope with the impacts of ADHD, it can get overwhelming, and it may feel like the symptoms are getting harder to manage. The symptoms of ADHD can vary in each individual, but they aren’t all obstacles to life. Some symptoms of ADHD can enhance the lives of those diagnosed.

These symptoms are triggered by altered brain chemistry and neural activity:

- Lack of general focus

- Hyperfocused on details

- Poor impulse control or spontaneity

- Poor time management

- Inattention

- Increased empathy and exaggerated emotions

- Hyperactivity

- Executive dysfunction

There is no single test to determine if a person has ADHD. Additionally, there are three subtypes of ADHD. They are primarily hyperactive, primarily inattentive, or primarily combined types.

There are nine symptoms of ADHD that are primarily inattentive or primarily hyperactive. Adults must exhibit at least five of the symptoms in multiple settings to be diagnosed with ADHD.

How to Treat ADHD

The best treatments for ADHD are combinations of several approaches that work together. The ideal combination may be different for each individual.

They can include some or all of the following:

- Behavioral therapy

- Supplements

- Stress reduction

Adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder can develop strategies that help focus attention to successfully complete their activities at home and at work.

This is how Foss successfully completed nursing school and has thrived in her position in a fast-paced healthcare environment.

Seeking a Diagnosis

Foss was prompted to see her doctor after a classmate with many of the same challenges she had was diagnosed with ADHD. Finally having a diagnosis took a weight off her shoulders.

Foss has found that her symptoms can vary from day to day.

“Sometimes I can multitask like a pro; other times I constantly forget to bring a patient the warm blanket I promised them,” she says.

Self-acceptance and reparenting are two big ways to cope with the neurodivergence of ADHD while having compassion for its impacts. Foss recognizes that her brain is not as organized as her coworkers, and she has found approaches that help her work around the impacts of ADHD and successfully function as a nurse.

With medication, education, and established strategies, Foss stays organized by writing down everything. These strategies help her complete her tasks and pass important details to the next shift.

Foss has also identified certain benefits to her ADHD that help her at work. For example, she believes that she is more comfortable deviating from a set list of activities than some of her coworkers.

“I’m the one other nurses come to with the unusual questions about finding a workaround when we’re out of supplies,” she says.

Her management recognizes these qualities in Foss too. The education department specifically schedules Foss to cover other staff when three rounds of education are planned in a shift.

“I can go with the flow and rotate between three different assignments better than others can,” she says.

Finding what works for you is the first step in thriving as a nurse with ADHD. Seeking a community of people similarly impacted by ADHD can increase your sense of belonging, your support network, and your ability to meet your unique needs as a nurse or nursing student with ADHD.

Meet Our Contributor

Molly Foss, RN

Molly Foss is a registered nurse at a level 1 trauma center, but before that she was a mechanical drafter. After five years she realized that she wasn’t cut out to be sitting at a desk all day. At age 27, she went back to school to become a nurse. After two years, she was diagnosed with ADHD during her first year of nursing school. She has been a nurse for 11 years and has been in trauma and specialty care for the last eight.

You might be interested in

Time Management Tips for Nursing Students

Many nursing students have out-of-control schedules and a vanishing social life. These time management strategies can help you achieve your goals and still get some sleep.

Study Tips for Online Nursing Students

To help learners improve their study skills, we have gathered 10 tips for online success.

How to Manage Stress as a Nurse

Have you learned how to manage stress as a nurse? These 15 strategies can help reduce stress and protect your physical and mental health.

- Don’t leave your email app open as it is a huge distraction to hear that ‘incoming mail’ message. Make a rule that you only check your email at set times of day and only after your work is done.

- Use reminder alarms so you can “set it and forget it.” Knowing your alarm will go off when it’s time to leave to pick up the kids means your brain has a lot less “stuff” swirling around in it, making it much easier to focus on the task at hand.

- Slow down when taking tests and read things aloud if you can. This greatly minimizes the risk you’ll skip over potentially important words or phrases.

- When attending in-person lectures, sit in the front row so there are no distractions in front of you.

- If electronics are difficult distractions for you to resist, try taking notes on paper so you aren’t tempted to shop or do other things that pull you away from your work.

- Utilize earplugs or noise-canceling headphones during exams and work sessions if sounds are a source of distraction for you.

- Reward yourself for completing focus sessions. Maybe it’s making a cup of tea, playing with the dog or spending ten minutes doing an activity you enjoy. You’ve worked hard….you’ve earned it!

- Minimize visual distractions by keeping only the things you need to for that specific task/assignment on your desk. Put other books, notes or in-progress projects out of sight.

- If you tend to procrastinate with non-essential activities (especially when stressed), write a note to yourself and put it somewhere you can see it. Maybe it says, “I’ll organize my closet tomorrow. Today I’m studying for an exam.”

- If a thought or future task keeps popping into your head while you’re studying, jot it down on a dedicated list of things to tackle later. I call this my “Later List.”

Create an ADHD-friendly study space

Tackling nursing school with ADHD means setting up a workspace designed to maximize your success.

- Make sure you have everything you need at your desk area so you can get to work and minimize disruptions. This may include a water bottle, a snack, pens/pencils/highlighters, a comfortable chair, headphones, fidgets, reference books and study materials.

- Consider a computer riser so you can sit, stand, sit, stand, sit, stand, etc…

- Use a bookcase cabinet with doors versus open shelving so you can put things away when you’re not using them, leading to less distractions.

- Designate a study-only area in your home. This sends a message to your brain that when you’re in this space, it’s time to work.

- Some students benefit from alternate forms of seating and switch from a desk to a table to the couch to a lap desk, etc… Experiment to find what works for you!

Maximize your learning style

If you’re going to nursing school with ADHD, studying effectively means knowing and maximizing your learning style.

- Utilize interactive learning to stay as engaged as possible. A great resource for this is through the online access codes that come with textbooks. These often include many interactive activities that can help the student with ADHD stay engaged while learning and studying.

- Write your notes in different color pens or pencils. For visual and creative learners this can “trick” your brain into thinking it’s art and not just a bunch of words.

- Learn the material by teaching someone else. This is an excellent way to stay engaged and take on a very active role in your learning. Plus, it’s a great way to develop positive relationships in nursing school!

- Incorporate physical activity while reading. I’ve heard of students using fidget tools, incorporating color-coded highlighting and even knitting.

- Use a fidget tool to remind yourself to slow down during tests.

- If your brain is drawn to art and creativity, doing things like color-coding your notes, drawing out concepts, and even, using different handwriting styles can all engage your brain in an effective way.

- If you tend to zone out or lose interest during lecture, try to familiarize yourself with the concepts prior to class. One student reported that it was very helpful to do a quick skim of the reading and then try to fill out a LATTE template before class. Then, during lecture, she would stay engaged by filling in the gaps.

- If your school allows audio recordings of lecture, take advantage of this so you can listen to the lessons more than once. If you get bored with people who speak slowly, increase the playback speed.

- Utilize captions while watching videos. This gives your brain additional sensory input which can help you stay focused and engaged. You may need to request closed-captioning from your school or ask your professor to turn on captioning when using Zoom.

- Find what helps you remember things, even if it seems silly. Some students use goofy stories to remember medication side effects or disease signs/symptoms. Other effective techniques are mnemonic devices or even songs. Hey, whatever works!

- As you learn a concept, try to guess what the test questions will be about. Write these out as you go and not only have you stayed engaged, you’ve also created a study guide for the exam. That’s a win-win!

- Record yourself reading your notes or talking through concepts. Listen to these recordings as you do a physical activity such as walking to class or doing chores around the house.

- When reading out loud, try using an exaggerated voice. It sounds silly but it can help you stay engaged AND help you remember.

- Many students learn optimally by having the material read TO them. If you’re utilizing e-books, check to see if they have a “read aloud” option.

Apps and equipment

Having the tools you need to thrive can make going to nursing school with ADHD a lot less stressful. Note that some of these links earn this site a commission, these are always designated by #ad.

- Fidgets, like this Infinity Cube (#ad) , can help ease anxiety, focus your mind and serve as a reminder to stay engaged.

- iPad with Apple pencil and the Notability app. This app allows you to record lectures and take notes within the same document. This is a great way to review the material if you lost attention during class.

- Habitica – app that helps you form and follow habit routines with fun gamification built in.

- Freedom and Self Control – apps that block distracting apps and websites at times you designate.

- Focus Keeper – app that utilizes the Pomodoro technique.

- A white noise machine (#ad) can drown out unwanted sounds that cause distractions.

- Noise-canceling headphones(#ad) create a sound-free environment, or a superb auditory experience…you choose!

- An adjustable computer riser (#ad) enables you to transition from sitting to standing with ease.

Utilize your resources

If you’re heading into nursing school with ADHD, take the time to familiarize yourself with the resources available at your school.

- Utilize every resource that is available at your school. These include the disability center, writing center, tutoring services and counseling. Plan ahead because some of these may require appointments and documentation, especially when getting accommodations for things like exams.

- The “ How to ADHD ” YouTube channel has some wonderful suggestions and tools.

- If your school or division of Nursing has tutoring, make an appointment even if you don’t necessarily need the tutoring. Having structured study time is worth its weight in gold.

Be a clinical rockstar

Nursing school clinicals can be especially challenging for students with ADHD, but with these tips you will soar!

- In clinical, lists and routines will be your BFFs. Many students report having several things they need to do and then forgetting what they are by the time they get to the patient’s room. That’s because hospitals (and patients) are absolutely brimming with distractions. Make lists, even if it’s just a list of things to do next time you go in the patient’s room. Over time, you’ll probably find you rely on these lists less and less as the environment becomes more familiar.

- Routines help ensure you don’t forget to do important tasks. Develop a “start-of-shift” routine a “first-assessment” routine and an “end-of-shift” routine. I talk about all these routines in my book, Nursing School Thrive Guide (#ad).

- Use a run sheet. Run sheets are your general plan for the day, so you know when meds and specific interventions will be done. Download the Clinical Success Pack and get a run sheet you can use over and over again.

- Keep a small notepad (#ad) with you at all times. Jot down vital signs, patient requests, instructions from the RN and anything else you need to remember. There’s no shame in writing things down, especially when those tasks are new.

Stick with your medication regimen

- This is not the time to experiment with your medication regimen without your physician’s input. Up to 50% of college students under-use or stop using their ADHD medication. Always discuss your medication regimen with your healthcare provider.

- If you move away from home, have a plan for refills and regular check-ins with your doctor. This may include finding a new primary care provider, so plan ahead.

Be kind to yourself

Attending nursing school is rough enough, attending nursing school with ADHD can be especially challenging. You owe it to yourself to celebrate how amazing you are and to reward yourself for a job well done!

- More than anything else, it’s important that you give yourself some grace. Things that seem easy for other students may be challenging for you, but you actually have a lot of advantages. People with ADHD are creative problem solvers and that is HUGE in nursing…so give yourself a pat on the back!

- Exercise has been shown to be highly beneficial for students with ADHD, so make the time even if it’s just 30 minutes a day.

- Incorporate self care into your routine, and this includes down time to do things that simply bring you joy. Remember that replenishing your emotional reserves will actually make you MORE productive in the long run.

____________________________________________________________

The information, including but not limited to, audio, video, text, and graphics contained on this website are for educational purposes only. No content on this website is intended to guide nursing practice and does not supersede any individual healthcare provider’s scope of practice or any nursing school curriculum. Additionally, no content on this website is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

20 Secrets of Successful Nursing Students

Being a successful nursing student is more than just study tips and test strategies. It’s a way of life.

you may also like...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Thieme Open Access

ADHD: Current Concepts and Treatments in Children and Adolescents

Renate drechsler.

1 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital of Psychiatry, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Silvia Brem

2 Neuroscience Center Zurich, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Daniel Brandeis

3 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim/Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany

4 Zurich Center for Integrative Human Physiology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Edna Grünblatt

Gregor berger, susanne walitza.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is among the most frequent disorders within child and adolescent psychiatry, with a prevalence of over 5%. Nosological systems, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Diseases, editions 10 and 11 (ICD-10/11) continue to define ADHD according to behavioral criteria, based on observation and on informant reports. Despite an overwhelming body of research on ADHD over the last 10 to 20 years, valid neurobiological markers or other objective criteria that may lead to unequivocal diagnostic classification are still lacking. On the contrary, the concept of ADHD seems to have become broader and more heterogeneous. Thus, the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD are still challenging for clinicians, necessitating increased reliance on their expertise and experience. The first part of this review presents an overview of the current definitions of the disorder (DSM-5, ICD-10/11). Furthermore, it discusses more controversial aspects of the construct of ADHD, including the dimensional versus categorical approach, alternative ADHD constructs, and aspects pertaining to epidemiology and prevalence. The second part focuses on comorbidities, on the difficulty of distinguishing between “primary” and “secondary” ADHD for purposes of differential diagnosis, and on clinical diagnostic procedures. In the third and most prominent part, an overview of current neurobiological concepts of ADHD is given, including neuropsychological and neurophysiological researches and summaries of current neuroimaging and genetic studies. Finally, treatment options are reviewed, including a discussion of multimodal, pharmacological, and nonpharmacological interventions and their evidence base.

Introduction

With a prevalence of over 5%, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most frequent disorders within child and adolescent psychiatry. Despite an overwhelming body of research, approximately 20,000 publications have been referenced in PubMed during the past 10 years, assessment and treatment continue to present a challenge for clinicians. ADHD is characterized by the heterogeneity of presentations, which may take opposite forms, by frequent and variable comorbidities and an overlap with other disorders, and by the context-dependency of symptoms, which may or may not become apparent during clinical examination. While the neurobiological and genetic underpinnings of the disorder are beyond dispute, biomarkers or other objective criteria, which could lead to an automatic algorithm for the reliable identification of ADHD in an individual within clinical practice, are still lacking. In contrast to what one might expect after years of intense research, ADHD criteria defined by nosological systems, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Diseases, editions 10 and 11 (ICD-10/11) have not become narrower and more specific. Rather, they have become broader, for example, encompassing wider age ranges, thus placing more emphasis on the specialist's expertise and experience. 1 2 3

Definitions and Phenomenology

Adhd according to the dsm-5 and icd-10/11.

ADHD is defined as a neurodevelopmental disorder. Its diagnostic classification is based on the observation of behavioral symptoms. ADHD according to the DSM-5 continues to be a diagnosis of exclusion and should not be diagnosed if the behavioral symptoms can be better explained by other mental disorders (e.g., psychotic disorder, mood or anxiety disorder, personality disorder, substance intoxication, or withdrawal). 1 However, comorbidity with other mental disorders is common.

In the DSM-5, the defining symptoms of ADHD are divided into symptoms of inattention (11 symptoms) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (9 symptoms). 1 The former differentiation between subtypes in the DSM-IV proved to be unstable and to depend on the situational context, on informants, or on maturation, and was therefore replaced by “presentations.” 4 Thus, the DSM-5 distinguishes between different presentations of ADHD: predominantly inattentive (6 or more out of 11 symptoms present), predominantly hyperactive/impulsive (6 or more out of 9 symptoms present), and combined presentation (both criteria fulfilled), as well as a partial remission category. Symptoms have to be present in two or more settings before the age of 12 years for at least 6 months and have to reduce or impair social, academic, or occupational functioning. In adolescents over 17 years and in adults, five symptoms per dimension need to be present for diagnosis. 1 In adults, the use of validated instruments like the Wender Utah rating scale is recommended. 5

In contrast, the ICD-10 classification distinguishes between hyperkinetic disorder of childhood (with at least six symptoms of inattention and six symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity, present before the age of 6 years) and hyperkinetic conduct disorder, a combination of ADHD symptoms and symptoms of oppositional defiant and conduct disorders (CD). 3 In the ICD-11 (online release from June 2018, printed release expected 2022), the latter category has been dropped, as has the precise age limit (“onset during the developmental period, typically early to mid-childhood”). Moreover, the ICD-11 distinguishes five ADHD subcategories, which match those of the DSM-5: ADHD combined presentation, ADHD predominantly inattentive presentation, ADHD predominantly hyperactive/impulsive presentation and two residual categories, ADHD other specified and ADHD nonspecified presentation. For diagnosis, behavioral symptoms need to be outside the limits of normal variation expected for the individual's age and level of intellectual functioning. 2

Overlapping Constructs: Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and Emotional Dysregulation

Sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) is a clinical construct characterized by low energy, sleepiness, and absent-mindedness, and is estimated to occur in 39 to 59% of (adult) individuals with ADHD. 6 7 The question of whether SCT might constitute a feature of ADHD or a separate construct that overlaps with ADHD inattention symptoms is unresolved. 8 While current studies indicate that SCT might be distinct and independent from hyperactivity/impulsivity, as well as from inattention dimensions, it remains uncertain whether it should be considered as a separate disorder. 8 9 Twin studies have revealed a certain overlap between SCT and ADHD, especially with regard to inattention symptoms, but SCT seems to be more strongly related to nonshared environmental factors. 10

Emotion dysregulation is another associated feature that has been discussed as a possible core component of childhood ADHD, although it is not included in the DSM-5 criteria. Deficient emotion regulation is more typically part of the symptom definition of other psychopathological disorders, such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), CD, or disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DSM-5; for children up to 8 years). 11 However, an estimated 50 to 75% of children with ADHD also present symptoms of emotion dysregulation, for example, anger, irritability, low tolerance for frustration, and outbursts, or sometimes express inappropriate positive emotions. The presence of these symptoms increases the risk for further comorbidities, such as ODD and also for anxiety disorders. 12 13 For adult ADHD, emotional irritability is a defining symptom according to the Wender Utah criteria, and has been confirmed as a primary ADHD symptom by several studies (e.g., Hirsch et al). 5 14 15

Whether emotion dysregulation is inherent to ADHD, applies to a subgroup with combined symptoms and a singular neurobiological pathway, or is comorbid with but independent of ADHD, is still a matter of debate (for a description of these three models; Shaw et al 13 ). Faraone et al 12 distinguished three ADHD prototypes with regard to deficient emotion regulation: ADHD prototype 1 with high-emotional impulsivity and deficient self-regulation, prototype 2 with low-emotional impulsivity and deficient self-regulation, and prototype 3 with high-emotional impulsivity and effective self-regulation. All three prototypes are characterized by an inappropriate intensity of emotional response. While prototypes 1 and 3 build up their responses very quickly, prototype 2 is slower to respond but experiences higher subjective emotional upheaval than is overtly shown in the behavior. Prototypes 1 and 2 both need more time to calm down compared with prototype 3 in which emotional self-regulation capacities are intact.

Dimensional versus Categorical Nature of ADHD

Recent research on subthreshold ADHD argues in favor of a dimensional rather than categorical understanding of the ADHD construct, as its core symptoms and comorbid features are dimensionally distributed in the population. 16 17 18 Subthreshold ADHD is common in the population, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 10%. 19 According to Biederman and colleagues, clinically referred children with subthreshold ADHD symptoms show a similar amount of functional deficits and comorbid symptoms to those with full ADHD, but tend to come from higher social-class families with fewer family conflicts, to have fewer perinatal complications, and to be older and female (for the latter two, a confound with DSM-IV criteria cannot be excluded). 20

Temperament and Personality Approaches to ADHD

Another approach which is in accordance with a dimensional concept is to analyze ADHD and categorize subtypes according to temperament/personality traits (for a review and the different concepts of temperament see Gomez and Corr 21 ). Temperament/personality traits are usually defined as neurobiologically based constitutional tendencies, which determine how the individual searches for or reacts to external stimulation and regulates emotion and activity. While temperament traits per se are not pathological, extreme variations or specific combinations of traits may lead to pathological behavior. This approach has been investigated in several studies by Martel and colleagues and Nigg, 22 23 24 who employed a temperament model comprising three empirically derived domains 25 26 : (1) negative affect, such as tendencies to react with anger, frustration, or fear; (2) positive affect or surgency which includes overall activity, expression of happiness, and interest in novelty; and (3) effortful control which is related to self-regulation and the control of action. The latter domain shows a strong overlap with the concept of executive function. 27 In a community sample, early temperamental traits, especially effortful control and activity level, were found to potentially predict later ADHD. 28 Karalunas et al 29 30 distinguished three temperament profiles in a sample of children with ADHD: one with normal emotional functioning; one with high surgency, characterized by high levels of positive approach-motivated behaviors and a high–activity level; and one with high negative (“irritable”) affect, with the latter showing the strongest, albeit only moderate stability over 2 years. Irritability was not reducible to comorbidity with ODD or CD and was interpreted as an ADHD subgroup characteristic with predictive validity for an unfavorable outcome. These ADHD temperament types were distinguished by resting-state and peripheral physiological characteristics as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). 29

Epidemiology and Prevalence

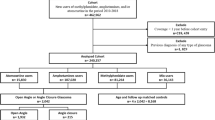

While ADHD seems to be a phenomenon that is encountered worldwide, 31 prevalence rates and reported changes in prevalence are highly variable, depending on country and regions, method, and sample. 32 A meta-analysis by Polanczyk et al 32 yielded a worldwide prevalence rate of 5.8% in children and adolescents. 33 In an update published 6 years later, the authors did not find evidence for an increase in prevalence over a time span of 30 years. Other meta-analyses reported slightly higher (e.g., 7.2%) 34 or lower prevalence rates, which seems to be attributable to the different criteria adopted for defining ADHD. Prevalence rates in children and adolescents represent averaged values across the full age range, but peak prevalence may be much higher in certain age groups, for example, 13% in 9-year-old boys. 35 Universal ADHD prevalence in adults is estimated to lie at 2.8%, with higher rates in high-income (3.6%) than in low-income (1.4%) countries. 36 True prevalence rates (also called community prevalence, e.g., Sayal et al 37 ) should be based on population-based representative health surveys, that is, the actual base rate of ADHD in the population, in contrast to the administrative base rate, which is related to clinical data collection (Taylor 38 ). Recent reports on the increase in ADHD rates usually refer to administrative rates, drawn from health insurance companies, from the number of clinical referrals for ADHD, 39 clinical case identification estimates, or from the percentage of children taking stimulant medication (prescription data). Changes in these rates may be influenced by increased awareness, destigmatization, modifications in the defining criteria of ADHD, or altered medical practice. According to a recent U.S. health survey on children and adolescents (4–17 years), in which parents had to indicate whether their child had ever been diagnosed with ADHD, the percentage of diagnoses increased from 6.1% in 1997 to 10.2% in 2016. 40 A representative Danish survey based on health registry, data collected from 1995 to 2010 reported that ADHD incidence rates increased by a factor of approximately 12 (for individuals aged 4–65 years) during this period. Moreover, the gender ratio decreased from 7.5:1 to 3:1 at early school age and from 8.1:1 to 1.6:1 in adolescents in the same time frame, 41 42 probably indicating an improved awareness of ADHD symptoms in girls. In other countries, it is assumed that girls are still underdiagnosed. 38

Population register data show that the use of stimulants for ADHD has increased considerably worldwide. 43 In most countries, an increase in stimulant medication use has been observed in children since the 1990s (e.g., United Kingdom from 0.15% in 1992 to 5.1% in 2012/2013), 44 45 but in some European countries, stimulant prescription rates for children and adolescents have remained stable or decreased over the last 5 to 10 years (e.g., Germany). 35 In the United States, the prescription of methylphenidate peaked in 2012 and has since been slightly decreasing, while the use of amphetamines continues to rise. 46

Comorbidity, Differential Diagnosis, and Clinical Assessment

Comorbidity.

ADHD is characterized by frequent comorbidity and overlap with other neurodevelopmental and mental disorders of childhood and adolescence. The most frequent comorbidities are learning disorders (reading disorders: 15–50%, 4 dyscalculia: 5–30%, 47 autism spectrum disorder, which since the DSM-5 is no longer viewed as an exclusion criterion for ADHD diagnosis: 70–85%, 48 49 tic/Tourette's disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder: 20%, and 5%, 50 developmental coordination disorder: 30–50%, 51 depression and anxiety disorders: 0–45%, 52 53 and ODD and CD: 27–55% 54 ). ADHD increases the risk of substance misuse disorders 1.5-fold (2.4-fold for smoking) and problematic media use 9.3-fold in adolescence 55 56 and increases the risk of becoming obese 1.23-fold for adolescent girls. 57 58 59 It is also associated with different forms of dysregulated eating in children and adolescents. Enuresis occurs in approximately 17% of children with ADHD, 60 and sleep disorders in 25 to 70%. 61 Frequent neurological comorbidities of ADHD include migraine (about thrice more frequent in ADHD than in typically developing [TD] children) 62 63 64 and epilepsy (2.3 to thrice more frequent in ADHD than in TD children). 65 66 The risk of coexisting ADHD being seen as a comorbid condition and not the primary diagnosis is considerably enhanced in many childhood disorders of different origins. For example, the rate of comorbid ADHD is estimated at 15 to 40% 67 68 in children with reading disorders and at 26 to 41% 69 70 in children with mild intellectual dysfunction. While comorbidity in neurodevelopmental disorders may arise from a certain genetic overlap (see details under genetic associations), ADHD symptoms are also present in several disorders with well-known and circumscribed genetic defects, normally not related to ADHD (e.g., neurofibromatosis, Turner's syndrome, and Noonan's syndrome) 71 or disorders with nongenetic causes, such as traumatic brain injuries, pre-, peri- or postnatal stroke, or syndromes due to toxic agents, such as fetal alcohol syndrome. Comorbid ADHD is estimated in 20 to 50% of children with epilepsy, 72 73 in 43% of children with fetal alcohol syndrome, 74 and in 40% of children with neurofibromatosis I. 75 ADHD is three times more frequent in preterm-born children than in children born at term and four times more frequent in extremely preterm-born children. 76

Differential Diagnosis, Primary and Secondary ADHD

A range of medical and psychiatric conditions show symptoms that are also present in primary ADHD. The most important medical conditions which are known to “mimic” ADHD and need to be excluded during the diagnostic process are epilepsy (especially absence epilepsy and rolandic epilepsy), thyroid disorders, sleep disorder, drug interaction, anemia, and leukodystrophy. 77 78 The most important psychiatric conditions to be excluded are learning disorder, anxiety disorders, and affective disorders, while an adverse home environment also needs to be excluded.

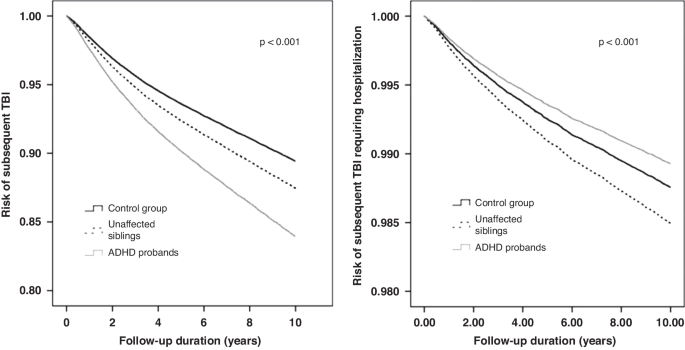

However, the picture is complex, as many differential diagnoses may also occur as comorbidities. For instance, bipolar disorder, which is frequently diagnosed in children and adolescents in the United States but not in Europe, is considered as a differential diagnosis to ADHD, but ADHD has also been found to be a comorbidity of bipolar disorder in 21 to 98% of cases. 79 Similarly, absence epilepsy is a differential diagnosis of ADHD but is also considered to be a frequent comorbidity, occurring in 30 to 60% of children with absence epilepsy. 80 The prevalence of the ADHD phenotype in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (rolandic epilepsy) lies at 64 to 65%, 81 and is possibly related to the occurrence of febrile convulsions. 82 The literature often does not draw a clear distinction between an ADHD phenotype, which includes all types of etiologies and causes, and a yet to be specified developmental ADHD “genotype.” Some authors use terms, such as “idiopathic” ADHD, 83 “primary,” or “genotypic” ADHD, 84 in contrast to ADHD of circumscribed origin other than developmental, the latter being referred to as ADHD “phenotype,” or “phenocopy,” 85 or “ADHD-like.” 86 “Secondary ADHD” usually refers to newly acquired ADHD symptoms arising after a known event or incident, for example, a head trauma or stroke. After early childhood stroke, the ADHD phenotype occurs in 13 to 20% of cases, and after pediatric traumatic brain injury, ADHD symptoms are observed in 15 to 20% of children. 87 Having ADHD considerably increases the risk of suffering a traumatic brain injury, 88 89 90 and most studies on secondary ADHD after traumatic brain injury control for or compare with premorbid ADHD (e.g., Ornstein et al 91 ). Whether and to what extent “phenotypic” and “genotypic” ADHD need to be distinguished on a phenomenological level is not clear. It is possible that shared neurobiological mechanisms will prevail and that genetic vulnerability and epigenetic factors may play a role in both types. For example, James et al 86 compared neurophysiological markers in two groups of adolescents with ADHD, one born very preterm and the other born at term. While the authors found very similar ADHD-specific markers in the two groups, some additional deficits only emerged in the preterm group, indicating more severe impairment. Other examples are rare genetic diseases with known genetic defects, which are often comorbid with ADHD. One may ask whether, for example, ADHD in Turner's syndrome should be considered as a rare genetic ADHD variant and count as genotypic ADHD, or whether it results from a different genetic etiology, with the status of an ADHD phenotype.

Clinical Diagnostic Procedure

Clinical assessment in children should mainly be based on a clinical interview with parents, including an exploration of the problems, the detailed developmental history of the child including medical or psychiatric antecedents, information on family functioning, peer relationships, and school history. According to the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom, this may also include information on the mental health of the parents and the family's economic situation. The child's mental state should be assessed, possibly using a standardized semistructured clinical interview containing ADHD assessments (e.g., Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime version, DSM-5) 92 93 and by observer reports. The exploration should cover behavioral difficulties and strengths in several life contexts, for example, school, peer relationships, and leisure time. The use of informant rating scales, such as Conners' Rating Scales, 3rd edition, 94 or the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire 95 may be useful, but diagnosis should not be solely based on rating scales (NICE, AWFM ADHD). 96 97 A further interview should be conducted with the child or adolescent to gain a picture of the patient's perspective on current problems, needs, and goals, even though self-reports are considered less reliable for diagnosis. Information should also be obtained from the school, for example, by face-to-face or telephone contact with the teacher and, if possible, by direct school-based observation. A medical examination should be performed to exclude somatic causes for the behavioral symptoms and to gain an impression of the general physical condition of the patient. Current guidelines do not recommend including objective test procedures (intelligence and neuropsychological tests), neuroimaging, or neurophysiological measures in routine ADHD assessment but do suggest their use as additional tools when questions about cognitive functions, academic problems, coexisting abnormalities in electroencephalography (EEG), or unrecognized neurological conditions arise. After completion of the information gathering, the NICE guidelines recommend a period of “watchful waiting” for up to 10 weeks before delivering a formal diagnosis of ADHD. A younger age of the diagnosed child relative to his/her classmates has to be mentioned as one of the many pitfalls in the assessment of ADHD. It has been shown that the youngest children in a class have the highest probability of being diagnosed with ADHD and of being medicated with stimulants. 98

There is consensus that the diagnosis of ADHD requires a specialist, that is, a child psychiatrist, a pediatrician, or other appropriately qualified health care professionals with training and expertise in diagnosing ADHD. 97

Current Neurobiological and Neuropsychological Concepts

Neuropsychology, neuropsychological pathways and subgroups.

ADHD is related to multiple underlying neurobiological pathways and heterogeneous neuropsychological (NP) profiles. Twenty-five years ago, ADHD was characterized as a disorder of inhibitory self-control, 54 and an early dual pathway model distinguished between an inhibitory/executive function pathway and a motivational/delay aversion pathway (also called “cool” and “hot” executive function pathways in later publications), which are related to distinct neurobiological networks. 99 100 101 Still, the two systems may also interact. 102

Since then, other pathways have been added, such as time processing, 103 but a definitive number of possible pathways is difficult to define. For example, Coghill and colleagues 104 differentiated six cognitive factors in children with ADHD (working memory, inhibition, delay aversion, decision-making, timing, and response time variability) derived from seven subtests of the Cambridge neuropsychological test automated battery. Attempts to empirically classify patients into subgroups with selective performance profiles departing from comprehensive NP data collection were inconclusive. For example, using delay aversion, working memory, and response-time tasks, Lambek and colleagues 105 expected to differentiate corresponding performance profile subgroups in children with ADHD. However, their analysis resulted in subgroups differentiated by the severity of impairments, and not by selective profiles. Other empirical studies using latent profile or cluster analysis of NP tasks in large ADHD samples have differentiated three 106 107 or four 108 NP profile groups, which all included children with ADHD, as well as TD children, differing in severity but not in the type of profile. This might indicate that the identified NP deficit profiles were not ADHD-specific, but rather reflected characteristic distributions of NP performances, which are also present in the general population, with extreme values in children with ADHD. Some other empirical studies in the search for subgroups, however, identified ADHD-specific performance profiles (“poor cognitive control,” 109 “with attentional lapses and fast processing speed” 110 ), among other profiles being shared with TD controls. Obviously, divergent results regarding subgrouping may also be related to differing compilations of tested domains, consequently leading to a limited comparability of these studies.

Which Neuropsychological Functions are Impaired in ADHD and When?

A meta-analysis conducted in 2005 identified consistent executive function deficits with moderate effect sizes in children with ADHD in terms of response inhibition, vigilance, working memory, and planning. 67 Since then, a vast number of studies on NP deficits in children with ADHD compared with TD controls have been published. A recent meta-analysis included 34 meta-analyses on neurocognitive profiles in ADHD (all ages) published until 2016, referring to 12 neurocognitive domains. 111 The authors found that 96% of all standardized mean differences were positive in favor of the control group. Unweighted effect sizes ranged from 0.35 (set shifting) to 0.66 (reaction time variability). Weighted mean effect sizes above 0.50 were found for working memory (0.54), reaction time variability (0.53), response inhibition (0.52), intelligence/achievement (0.51), and planning/organization (0.51). Effects were larger in children and adolescents than in adults. The other domains comprised vigilance, set shifting, selective attention, reaction time, fluency, decision making, and memory.

Nearly every neuropsychological domain has been found to be significantly impaired in ADHD compared with TD controls, though effect sizes are often small. This includes, for example, altered perception (e.g., increased odor sensitivity 112 ; altered sensory profile 113 ; impaired yellow/blue color perception, e.g., Banaschewski et al, 114 for review, see Fuermaier et al 115 ), emotional tasks (e.g., facial affect discrimination), 116 social tasks (e.g., Marton et al 117 ), communication, 118 and memory. 119 Several of the described impairments may be related to deficient top-down cognitive control and strategic deficits, 120 121 122 but there is also evidence for basic processing deficits. 123

Neuropsychological Deficits as Mediators of Gene-Behavior Relations

A vast amount of research has been devoted to the search for neuropsychological endophenotypes (or intermediate phenotypes) for ADHD, that is, neurobiologically based impairments of NP performance characteristic of the disorder that may also be found in nonaffected close relatives. ADHD neuropsychological endophenotypes are assumed to mediate genetic risk from common genetic variants. 124 So far, deficits in working memory, reaction-time variability, inhibition, time processing, response preparation, arousal regulation, and others have been identified as probable endophenotypes for ADHD. 124 125 126 127 Genetic studies indicate an association of an ADHD-specific polygenetic general risk score (i.e., the total number of genetic variants that may be associated with ADHD, mostly related to dopaminergic transmission) with working memory deficits and arousal/alertness, 124 or with a lower intelligence quotient (IQ) and working memory deficits, 128 respectively. More specifically, a link of ADHD-specific variants of DAT1 genes with inattention and hyperactivity symptoms seems to be mediated by inhibitory control deficits. 129

Individual Cognitive Profiles and the Relevance of Cognitive Testing for the Clinical Assessment

Heterogeneity is found with regard to profiles, as well as with regard to the severity of cognitive impairment in individuals with ADHD, as measured by standardized tests. ADHD does not necessarily come with impaired neuropsychological test performance: about one-third of children with ADHD will not present any clinically relevant impairment, while another one-third shows unstable or partial clinical impairment, and about another one-third performs below average in NP tests. The classic concept of NP impairment, which assumes relative stability over time, possibly does not apply to NP deficits observed in ADHD, or only to a lesser extent. For the larger part, the manifestation of performance deficits may depend on contextual factors, 130 such as reward, or specifically its timing, amount, and nature, or on energetic factors, 131 for example, the rate of stimulus presentation or the activation provided by the task.

Many studies have shown that behavioral ratings of ADHD symptoms or questionnaires on executive function deficits are not, or at best weakly, correlated with NP test performance, even when both target the same NP domain. 132 133 In consequence, questionnaires on executive functioning are not an appropriate replacement for neuropsychological testing. Likewise, ADHD symptom rating scales do not predict results of objective attention or executive function tests and vice versa. Although mild intellectual disability and low IQ are more typically associated with the disorder, ADHD can be encountered across the entire IQ spectrum, including highly gifted children. 134 Therefore, an intelligence test should be part of the diagnostic procedure, but is not mandatory according to ADHD guidelines. In some children, intellectual difficulties and not ADHD may be the underlying cause for ADHD-like behaviors, while in other children with ADHD, academic underachievement despite a high IQ may be present.

It has been argued that symptoms defining ADHD may be understood as dimensional markers of several disorders belonging to an ADHD spectrum and, in consequence, the diagnosis of these behavioral symptoms should be the starting point for a more in-depth diagnosis rather than the endpoint. 135 This should include the cognitive performance profile. The ADHD behavioral phenotype predicts neither NP impairment nor intellectual achievement in the individual case, and objective testing is the only way to obtain an accurate picture of the child's cognitive performance under standardized conditions. Its goal is not ADHD classification, but rather to obtain the best possible understanding of the relation between cognitive functioning and behavioral symptoms for a given patient, to establish an individually tailored treatment plan.

Neurophysiology

Neurophysiological methods like EEG, magnetoencephalography, and event-related potentials (ERPs) as task-locked EEG averages capture brain functions in ADHD at high (ms) temporal resolution. The approach covers both fast and slow neural processes and oscillations, and clarifies the type and timing of brain activity altered in ADHD at rest and in tasks. It reveals neural precursors, as well as correlates, and consequences of ADHD behavior. 136 Neurophysiological and particularly EEG measures also have a long and controversial history as potential biomarkers of ADHD. Current evidence clarifies how multiple pathways and deficits are involved in ADHD at the group level, but recent attempts toward individual clinical translation have also revealed considerable heterogeneity, which does not yet support a clinical application for diagnostic uses or treatment personalization, as explained below.

Resting Electroencephalography

The EEG is dominated by oscillations in frequency bands ranging from slow δ (<4 Hz) and θ (4–7 Hz) via α (8–12 Hz) to faster β (13–30 Hz) and γ (30–100 Hz) band activity. The spectral profile reflects maturation and arousal, with slow frequencies dominating during early childhood and slow-wave sleep. Source models can link scalp topography to brain sources and distributed networks.

Initial studies suggested a robust link between ADHD diagnosis and resting EEG markers of reduced attention, hypoarousal, or immaturity, such as increased θ and an increased θ/β ratio (TBR). However, more recent studies, 137 138 some with large samples, 139 140 failed to replicate a consistent TBR increase in ADHD. Instead, the results indicated heterogeneous θ and β power deviations in ADHD not explained by ADHD subtype and psychiatric comorbidity. 141 A cluster analysis of EEG in children with ADHD also revealed considerable heterogeneity regarding θ excess and β attenuation in ADHD. While several clusters with EEG patterns linked to underarousal and immaturity could be identified, only three of the five EEG clusters (60% of the cases with ADHD) had increased θ. 139 Several recent θ and TBR studies that no longer found TBR association with ADHD diagnosis still replicated the reliable age effects, 137 138 142 confirming the high quality of these studies. Increasing sleepiness in adolescents, 143 or shorter EEG recordings, may have reduced the sensitivity to time effects and state regulation deficits in ADHD, 136 144 potentially contributing to these replication failures. Also, conceptualizing TBR as a marker of inattention or maturational lag may be too simple, since θ activity can also reflect concentration, cognitive effort, and activation. 145 146

During sleep, stage profiles reveal no consistent deviations in ADHD, but the slow-wave sleep topography is altered. In particular, frontal slow waves are reduced, leading to a more posterior topography as observed also in younger children. 147 This delayed frontalization can be interpreted as a maturational delay in ADHD, in line with a cluster of resting EEG, changes in task related ERPs during response inhibition, 148 and structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. 149

Task Related Event-Related Potentials

Task-related processing measures, particularly ERPs, have critically advanced our understanding of ADHD through their high-time resolution, which can separate intact and compromised brain functions. ERPs have revealed impairments during preparation, attention, inhibition, action control, as well as error, and reward processing, with partly distinct networks but often present during different phases of the same task. In youth and adults with ADHD, the attentional and inhibitory P3 components and the preparatory contingent negative variation (CNV) component are most consistently affected, but state regulation and error or reward processing are also compromised. 136 150 Activity during preparation, attention, or inhibition is typically weaker and more variable but not delayed. This often occurs in task phases without visible behavior and precedes the compromised performance. Familial and genetic factors also modulate these markers of attention and control. Some impairment is also observed in nonaffected siblings or in parents without ADHD, 151 152 and genetic correlates often implicate the dopamine system. 125 Some ERP changes, like the attenuated CNV during preparation, remain stable throughout maturation, and are also markers of persistent ADHD, while other markers, such as the inhibition related P3, remain attenuated despite clinical remission. 148 153

Overall, the ERP results confirm attentional, cognitive, and motivational, rather than sensory or motor impairments in ADHD, in line with current psychological and neurobiological models. However, different ERP studies hardly used the same tests and measures, so valid statements regarding classification accuracy and effect size are particularly difficult, 154 and there is an urgent need for meta-analyses regarding the different ERPs.

Clinical Translation

Despite published failures to replicate robust TBR based classification of ADHD, a TBR-based EEG test was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to assist ADHD diagnosis. 155 Although not promoted as a stand-alone test, children with suspected ADHD, and increased TBR were claimed to likely meet full diagnostic criteria for ADHD; while children with suspected ADHD but no TBR increase should undergo further testing, as they were likely to have other disorders better explaining ADHD symptoms (see also DSM-5 exclusionary criterion E).

This multistage diagnostic approach could possibly identify a homogeneous neurophysiological subgroup, but it omits critical elements of careful, guideline-based ADHD diagnostics. Reliability and predictive value of the TBR remain untested, and the increasing evidence for poor validity of TBR renders it unsuitable for stand-alone ADHD diagnosis. Accordingly, the use of TBR as a diagnostic aid was broadly criticized. 156 157

In sum, the recent literature suggests that neither TBR nor other single EEG or ERP markers are sufficient to diagnose ADHD and are not recommended for clinical routine use, in line with the increasing evidence for heterogeneity in ADHD.

Combining measures across time, frequency, and tasks or states into multivariate patterns may better characterize ADHD. The potential of such approaches is evident in improved classification using machine-learning algorithms based on combinations of EEG measures 142 or EEG and ERP measures. 138 158 However, claims of high-classification accuracies up to 95% (e.g., Mueller et al 158 ) require further independent replication and validation with larger samples, and plausible mapping to neural systems and mechanisms. Modern pattern classification is particularly sensitive to uncontrolled sample characteristics and needs validation through independent large samples. 159

Focusing on EEG-based prediction rather than diagnosis may hold more promise for clinical translation, and may utilize the EEG heterogeneity in clinical ADHD samples. For example, early studies on predicting stimulant response suggested that children with altered wave activity, in particular increased TBR, θ or α slowing, respond well to stimulant medication. However, in recent prospective work with a large sample, TBR was not predictive, and α slowing allowed only limited prediction in a male adolescent subgroup. 160

Predicting response to intense nonpharmacological treatment is of particular interest given the high costs and time requirements. Promising findings have been reported for one neurofeedback study, where α EEG activity and stronger CNV activity together predicted nearly 30% of the treatment response. 161 Still, the lack of independent validation currently allows no clinical application.

In conclusion, neurophysiological measures have clarified a rich set of distinct impairments but also preserved functions which can also serve as markers of persistence or risk. These markers may also contribute in the classification of psychiatric disorders based on neuromarkers (research domain criteria approach). As potential predictors of treatment outcome they may support precision medicine, and proof-of-concept studies also highlight the potential of multivariate profiling. The findings also demonstrate the challenge with this approach, including notable replication failures, and generalizability of most findings remains to be tested. Neurophysiological markers are not ready to serve as tools or aids to reliably diagnose ADHD, or to personalize ADHD treatment in individual patients.

Neuroimaging

Modern brain imaging techniques have critically contributed to elucidating the etiology of ADHD. While MRI provides detailed insights into the brain microstructure, such as for example gray matter volume, density, cortical thickness, or white matter integrity, fMRI allows insights into brain functions through activation and connectivity measures with high–spatial resolution.

Delayed Maturation and Persistent Alterations in the Brain Microstructure in ADHD

The brain undergoes pronounced developmental alterations in childhood and adolescence. Gray matter volume and cortical thickness show nonlinear inverted U -shaped trajectories of maturation with a prepubertal increase followed by a subsequent decrease until adulthood while white matter volume progressively increases throughout adolescence and early adulthood in a rather linear way. 162 163 164 165 Large variations of the maturational curves in different brain regions and subregions suggest that phylogenetically older cortical areas mature earlier than the newer cortical regions. Moreover, brain areas associated with more basic motor or sensory functions mature earlier than areas associated with more complex functions including cognitive control or attention. 163 164 Altered maturation of the cortex for ADHD has been reported for multiple areas and cortical dimensions, 166 167 mainly in the form of delayed developmental trajectories in ADHD but recently also as persistent reductions, particularly in the frontal cortex. 168 Such findings speak for delayed maturation in specific areas rather than a global developmental delay of cortical maturation in ADHD. Microstructural alterations in ADHD have been associated with a decreased intracranial volume 169 and total brain size reduction of around 3 to 5%. 100 168 170 In accordance, increasing ADHD symptoms in the general population correlated negatively with the total brain size. 171 A meta-analysis (Frodl et al) and a recent cross-sectional mega- and meta-analysis (Hoogman et al) indicate that such reductions in brain volume may be due to decreased gray matter volumes in several subcortical structures, such as the accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, and putamen but also cortical areas (prefrontal, the parietotemporal cortex) and the cerebellum. 170 172 173 174 175 176 177 Effects sizes of subcortical alterations were highest in children with ADHD and the subcortical structures showed a delayed maturation. 169 Moreover, higher levels of hyperactivity/impulsivity in children were associated with a slower rate of cortical thinning in prefrontal and cingulate regions. 167 178 Differences in brain microstructure have also been reported in a meta-analysis for white matter integrity as measured with diffusion tensor imaging in tracts subserving the frontostriatal-cerebellar circuits. 179 To summarize, diverse neuroanatomical alterations in total brain volume and multiple cortical and subcortical dimensions characterize ADHD. These alterations are most pronounced in childhood and suggest a delayed maturation of specific cortical and subcortical areas along with some persistent reductions in frontal areas in a subgroup of ADHD patients with enduring symptoms into adulthood.

Alterations in the Brain Function of Specific Networks in ADHD

Specific functional networks, mainly those involved in inhibition, attention processes, cognitive control, reward processing, working memory, or during rest have been intensively studied in ADHD using fMRI in the past. Alterations have been reported in the corresponding brain networks and the main findings are summarized below.

Atypical Resting State Connectivity in Children with ADHD

Resting state examines spontaneous, low frequency fluctuations in the fMRI signal during rest, that is , in absence of any explicit task. 180 Resting state networks describe multiple brain regions for which the fMRI signal is correlated (functionally connected) at rest, but the same networks may coactivate also during task-based fMRI. 181 One important resting state network, the so-called default mode network (DMN), comprises brain areas that show higher activation during wakeful rest and deactivations with increasing attentional demands. 182 183 While the DMN usually shows decreasing activation with increasing attentional demands, the cognitive control network shows an opposite pattern and increases its activation. This inverse correlation of DMN and the cognitive control networks is diminished or absent in children and adults with ADHD and may explain impaired sustained attention through attentional lapses that are mediated by the DMN. 181 184 185 186 In addition, a more diffuse pattern of resting state networks connectivity and a delayed functional network development in children with ADHD have been reported. 187 Finally, atypical connectivity in cognitive and limbic cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical loops of patients with ADHD suggest that the neural substrates may either reside in impaired cognitive network and/or affective, motivational systems. 181

Altered Processing of Attention and Inhibition in Fronto-basal Ganglia Circuits in ADHD

Meta-analyses summarizing the findings of functional activation studies report most consistent alterations in brain activation patterns as hypoactivation of the frontoparietal network for executive functions and the ventral attention system for attentional processes in children with ADHD. 188 189 190 More specifically, motor or interference inhibition tasks yielded consistent decreases in a (right lateralized) fronto-basal ganglia network comprising supplementary motor area, anterior cingulate gyrus, left putamen, and right caudate in children with ADHD. 189 190 For tasks targeting attentional processes, decreased activation in a mainly right lateralized dorsolateral fronto-basal ganglia-thalamoparietal network characterized children with ADHD. Depending on the task, hyperactivation can cooccur in partly or distinct cerebellar, cortical, and subcortical regions. 188 189 190

Altered Reward Processing and Motivation

Emotion regulation and motivation is mediated by extended orbitomedial and ventromedial frontolimbic networks in the brain. 191 Abnormal sensitivity to reward seems to be an important factor in the etiology of ADHD as suggested by several models of ADHD, 192 193 194 mainly due to a hypofunctioning dopaminergic system. 195 In accordance, impairments in specific signals that indicate violations of expectations, the so called reward prediction errors (RPE), were shown in the medial prefrontal cortex of adolescents with ADHD during a learning task. 196 RPE signals are known to be encoded by the dopaminergic system of the brain, and deficient learning and decision making in ADHD may thus be a consequence of impaired RPE processing. 196 Abnormal activation has also been reported for the ventral striatum during reward anticipation and in other cortical and subcortical structures of the reward circuitry. 197

Normalization of Atypical Activation and Brain Structural Measures after Treatment

Stimulant medication and neurofeedback studies have pointed to a certain normalization of dysfunctional activation patterns in critical dorsolateral frontostriatal and orbitofrontostriatal regions along with improvements in ADHD symptoms. 198 199 200 201 Also, brain microstructure, especially the right caudate, has shown some gradual normalization with long-term stimulant treatment. 176 190

To conclude, a wide range of neuroimaging studies reveal relatively consistent functional deficits in ADHD during executive functions, including inhibitory control, working memory, reward processes, and attention regulation but also during rest. Some of these alterations are more persistent, others are specific to children and may thus represent a developmental delay. Specific treatments showed trends toward a normalization of alterations in brain microstructure and functional networks.

Genetic Associations with ADHD and ADHD Related Traits

From family studies, as well as twin studies, the heritability for ADHD has been estimated to be between 75 upto 90%. 202 Moreover, the heritability was found to be similar in males and females and for inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive components of ADHD. 202 Interestingly, a strong genetic component was also found when the extreme and subthreshold continuous ADHD trait symptoms were assessed in the Swedish twins. 19 Even over the lifespan, adult ADHD was found to demonstrate high heritability that was not affected by shared environmental effects. 203 Recently, structural and functional brain connectivity assessed in families affected by ADHD has been shown to have heritable components associated with ADHD. 204 Similarly, the heritability of ERPs elicited in a Go/No-Go-task measuring response inhibition known to be altered in ADHD, was found to be significantly heritable. 205

In several studies, ADHD-related traits have also shown significant heritability. For example, in two independent, population based studies, significant single nucleotide polymorphism heritability estimates were found for attention-deficit hyperactivity symptoms, externalizing problems, and total problems. 206 In another study, investigating the two opposite ends of ADHD symptoms, low-extreme ADHD traits were significantly associated with shared environmental factors without significant heritability. 207 While on the other hand, high-extreme ADHD traits showed significant heritability without shared environmental influences. 207 A crossdisorder study including 25 brain disorders from genome wide association studies (GWAS) of 265,218 patients and 784,643 controls, including their relationship to 17 phenotypes from 1,191,588 individuals, could demonstrate significant shared heritability. 208 In particular, ADHD shared common risk variants with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and with migraine. 208 Indeed, in general, population-based twin studies suggest that genetic factors are associated with related-population traits for several psychiatric disorders including ADHD. 209 This suggests that many psychiatric disorders are likely to be a continuous rather than a categorical phenotype.

Though ADHD was found to be highly heritable, the underlying genetic risk factors are still not fully revealed. The current consensus suggests, as in many other psychiatric disorders, a multifactorial polygenic nature of the common disorder. Both common genetic variants studied by hypothesis-driven candidate gene association or by the hypothesis-free GWAS could only reveal the tip of the iceberg. Through the candidate gene approach, only very few findings could show replicable significant association with ADHD, as reported by meta-analysis studies for the dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic genes. 210 211 Several GWAS have been conducted followed by meta-analysis, which again failed reaching genome-wide significant results. 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 However, recently, the first genome-wide significance has been reached in a GWAS meta-analysis consisting of over 20,000 ADHD patients and 35,000 controls. 225 Twelve independent loci were found to significantly associate with ADHD, including genes involved in neurodevelopmental processes, such as FOX2 and DUSP6 . 225 But even in these findings the effect sizes are rather small to be used for diagnostic tools. Therefore, polygenic risk score approaches have emerged as a possible tool to predict ADHD. 202 Yet this approach needs further investigation now that genome-wide significance has been reached by Demontis et al. 225 However, at this point, it is not yet possible to exclude that rare SNPs of strong effect may also be responsible (similar to breast cancer) for a small proportion of ADHD cases due to the heterogeneity of symptomatology, illness course, as well as biological marker distribution, as outlined above.

Multimodal Treatment of ADHD

A variety of national and international guidelines on the assessment and management of ADHD have been published over the last 10 years, not only for clinicians but also for patients and caregivers. 96 97 226 227 228 All guidelines recommend a multimodal treatment approach in which psychoeducation forms a cornerstone of the treatment and should be offered to all of those receiving an ADHD diagnosis, as well as to their families and caregivers.