- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Communication privacy management theory.

- Sandra Petronio Sandra Petronio Department of Communication Studies, Indiana University-Purdue University

- and Rachael Hernandez Rachael Hernandez Department of Communication Studies, Indiana University-Purdue University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.373

- Published online: 25 January 2019

Have you ever wondered why a complete stranger sitting next to you on a plane would tell you about a recent cancer diagnosis? Why your parents never disclosed that you were adopted, feeling shocked when you accidently find out as an adult? These and many other actions reflect decisions individuals make about managing their private information. Being aware of how individuals navigate decisions to disclose or protect their private information provides useful insights that aid in the development and sustainability of relationships with others. Given privacy plays an integral role in everyone’s life, knowing more about privacy management is critical. communication privacy management (CPM) theory was first introduced by Sandra Petronio in 2002. CPM is evidence-based and accordingly provides a dependable understanding of how decisions are made to disclose and protect private information. This theory uses plain language to understand privacy management in everyday life. CPM focuses on the relationship people have with each other in communicative contexts, such as face-to-face interactions, on social media, and in dyads or groups. CPM theory is based on a communicative-social behavioral perspective and not necessarily a legal point of view. CPM theory illustrates that privacy is not paradoxical but is sustainable through the process of a privacy management system used in everyday life. The theory of CPM has been employed in a number of contexts shedding light on antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of private information management. In addition, a number of researchers across multiple countries, such as the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Japan, Kenya, South Korea, and the United States, have used CPM theory in their research investigations. Learning more about the system of private information management allows for a better understanding of how people navigate managing their private information when others are involved. Literature illustrates patterns of privacy management and demonstrates the challenges as well as the positive outcomes of the way individuals regulate their private information.

- confidentiality

- information control

- information ownership

- self-disclosure

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Communication. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 05 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

Character limit 500 /500

- Communication

- Unveiling Communication Privacy Management Theory: A Comprehensive Insight

Communication privacy is a fundamental aspect of our daily interactions, but have you ever wondered how individuals manage and protect their private information in this digital age? Cue the Communication Privacy Management (CPM) theory, a comprehensive framework that sheds light on the intricacies of privacy management in interpersonal communication. In this article, we will delve into the depths of CPM theory, exploring its key concepts and applications. So, grab a cup of coffee and get ready to embark on an enlightening journey into the fascinating world of communication privacy management.

What are the 5 principles of communication privacy management theory?

What is the communication management privacy theory discover its significance and impact., frequently asked questions (faq).

The 5 principles of communication privacy management theory provide a framework for understanding how individuals navigate the intricacies of privacy in their interpersonal communication. Developed by Sandra Petronio, this theory highlights the complexities of managing privacy boundaries in relationships and the impact it has on communication dynamics.

1. Ownership

The principle of ownership emphasizes that individuals have the right to control their private information. It acknowledges that people have ownership over their personal experiences, thoughts, and feelings, and they can decide whether to disclose or withhold this information from others.

2. Privacy rules

Privacy rules refer to the guidelines that people establish for managing their private information. These rules can be explicit or implicit and vary across individuals and relationships. They shape how individuals make decisions about sharing or protecting their private information.

3. Co-ownership

Co-ownership recognizes that in certain relationships, individuals may share ownership over private information. People often form mutually agreed-upon rules and expectations for managing their shared privacy boundaries. This principle acknowledges the negotiation and coordination of privacy rules within relationships.

4. Boundary turbulence

Boundary turbulence occurs when there is a disruption or conflict in the management of privacy boundaries. It can arise from disagreements about privacy rules, breaches of trust, or unexpected disclosure of private information. Boundary turbulence can strain relationships and lead to communication difficulties.

5. Boundary coordination

Boundary coordination focuses on the strategies individuals use to manage their privacy boundaries. It recognizes that people engage in coordinated efforts to protect and disclose private information based on their understanding of the privacy rules. Effective boundary coordination enhances communication and fosters trust in relationships.

Overall, the 5 principles of communication privacy management theory shed light on the complexities of privacy management in interpersonal communication. They offer valuable insights into how individuals navigate the delicate balance between privacy and disclosure, helping us understand the dynamics of communication in various relationships.

What is the Communication Management Privacy Theory?

The Communication Management Privacy Theory is a conceptual framework that seeks to understand and guide the management of privacy in communication processes. It explores how individuals and organizations navigate the complexities of privacy in various contexts, such as interpersonal relationships, mass media, and digital communication platforms.

Significance and Impact:

The theory holds great significance in today's information-driven society, where privacy concerns have become increasingly prominent. Here are some key aspects of its impact:

- Understanding Privacy Boundaries: The theory helps individuals and organizations define and establish their privacy boundaries in communication. It recognizes that privacy is a subjective and context-dependent concept, emphasizing the importance of respecting diverse privacy expectations.

- Privacy Management Strategies: It provides insights into the strategies individuals and organizations employ to manage privacy. These strategies include selective exposure, boundary management, and communication regulation, enabling them to maintain a balance between privacy and information sharing.

- Privacy Norms and Expectations: The theory acknowledges the role of societal norms and cultural expectations in shaping privacy practices. By understanding these norms, individuals and organizations can navigate communication contexts while respecting privacy expectations and avoiding potential conflicts.

- Implications for Communication Technology: As technology continues to advance, the theory helps guide the design and implementation of communication technologies with privacy considerations in mind. It highlights the importance of user control, transparency, and consent in digital environments.

- Organizational Communication: The theory extends beyond interpersonal communication to encompass organizational settings. It explores how organizations manage privacy in their communication processes, taking into account factors such as employee privacy, information sharing, and data protection.

What is the central focus of communication privacy management theory? Understanding boundaries and information control.

Boundaries play a crucial role in the communication privacy management process.

These are the imaginary lines that individuals draw around their private information, determining who has access to it and who does not. Boundaries can be fluid and dynamic, changing depending on the relationship, context, or individual preferences.

The concept of information control refers to the strategies employed by individuals to regulate the flow of private information. This includes decisions about what information to disclose, to whom, and how much. Communication privacy management theory suggests that individuals are motivated to maintain control over their private information to protect their autonomy, privacy, and self-image.

Understanding the dynamics of boundary management and information control is essential in comprehending how individuals navigate their interpersonal relationships. The theory posits that when individuals share private information with others, they enter into a co-ownership of that information. Co-owners must mutually negotiate and establish rules for managing and disclosing the shared information.

According to the theory, individuals create and manage boundaries through a process of decision-making and negotiation. They employ a set of privacy rules that guide their interactions and determine what kind of information is shared, with whom, and under what circumstances. These rules are shaped by cultural norms, social expectations, and personal preferences.

The co-orientation model is another important aspect of communication privacy management theory. It suggests that individuals in relationships develop a shared understanding of each other's boundaries and privacy rules. This shared understanding helps establish a sense of trust, respect, and openness in communication.

What is the primary goal of communication privacy management? Understanding personal boundaries.

The primary goal of communication privacy management is understanding personal boundaries.

Communication privacy management, also known as CPM, is a theoretical framework that aims to explain how individuals navigate and manage the boundaries of their private information in the process of communication. It recognizes that individuals have varying levels of privacy needs and preferences, and that they actively regulate the flow of information to maintain their privacy.

Understanding personal boundaries

One of the key objectives of communication privacy management is to understand and respect personal boundaries. This involves recognizing that individuals have different thresholds for what they consider private and what they are willing to disclose to others.

CPM suggests that individuals make decisions about their privacy boundaries by weighing the potential risks and benefits of disclosing personal information. Factors such as the relationship with the other person, the context of the communication, and the nature of the information itself all play a role in determining these boundaries.

Boundary turbulence

Communication privacy management acknowledges that privacy boundaries are not static and can be subject to turbulence. Boundary turbulence occurs when there are conflicts or disagreements regarding privacy expectations and disclosures.

For example, a person may feel that they have shared certain information with someone in confidence, only to discover that the other person has revealed it to others without their consent. This breach of privacy can lead to boundary turbulence and strain the trust in the relationship.

Managing privacy boundaries

CPM also emphasizes the importance of actively managing privacy boundaries in communication. Individuals engage in privacy rules and strategies to maintain control over their personal information.

Some common strategies include selective disclosure, where individuals choose what information to disclose and to whom, and boundary coordination, where individuals negotiate and establish mutually agreed-upon privacy rules in relationships.

Implications of CPM

Understanding the primary goal of communication privacy management can have several implications for various contexts, such as interpersonal relationships, organizational communication, and online communication.

By recognizing and respecting personal boundaries, individuals can build trust, enhance communication quality, and avoid potential privacy violations. Organizations can also benefit from applying CPM principles by establishing clear privacy policies and guidelines that promote a culture of privacy awareness and respect.

What is Communication Privacy Management Theory?

Communication Privacy Management Theory (CPM Theory) is a comprehensive framework developed to understand how individuals navigate and manage the privacy of their personal information during communication interactions. It explores how people establish boundaries and make decisions regarding what to disclose and what to keep private in various social contexts.

How does Communication Privacy Management Theory work?

CPM Theory proposes that individuals create and manage privacy boundaries to control the flow of personal information. These boundaries act as filters, determining what information is shared with others and what remains private. The theory also emphasizes the collaborative aspect of privacy management, as individuals negotiate and coordinate their privacy rules with others to maintain mutual understanding and respect.

What are the key concepts of Communication Privacy Management Theory?

There are several key concepts in Communication Privacy Management Theory. These include:

- Privacy Boundaries: These are the metaphorical lines that individuals draw to separate private information from public disclosure.

- Ownership: Individuals have ownership rights over their private information and have the right to control its disclosure.

- Control: Individuals have agency in deciding when, where, and how to disclose their private information.

- Co-ownership: When more than one person is involved, they establish rules together to manage the privacy boundaries and disclose information.

- Boundary Turbulence: This refers to conflicts that may arise when privacy rules are violated or misunderstood, leading to a breakdown in communication or trust.

How is Communication Privacy Management Theory relevant in today's digital age?

In an era of social media and increased digital communication, Communication Privacy Management Theory provides valuable insights into how individuals navigate privacy concerns. It helps us understand the challenges people face in managing their privacy online, such as deciding what to share on social platforms and setting privacy settings. The theory's concepts can also be applied to organizational communication and information-sharing practices.

If you want to know other articles similar to Unveiling Communication Privacy Management Theory: A Comprehensive Insight you can visit the category Communication .

Related posts

The Big Theory Season 9: Hilarious Antics and Unexpected Twists

Endosymbiotic Theory: The Groundbreaking Discovery

Understanding Child Development Theories: Unraveling the Path to Growth

The Hypodermic Needle Model Theory: Influencing Mass Communication

Understanding the Life Course Theory in Criminology: Unraveling Paths to Offending

Unlock Your Musical Potential with an Online Music Theory Class

Communication Privacy Management Theory

Have you ever wondered why a complete stranger sitting next to you on a plane would tell you about a recent cancer diagnosis? Why your parents never disclosed that you were adopted, feeling shocked when you accidently find out as an adult? These and many other actions reflect decisions individuals make about managing their private information. Being aware of how individuals navigate decisions to disclose or protect their private information provides useful insights that aid in the development and sustainability of relationships with others. Given privacy plays an integral role in everyone’s life, knowing more about privacy management is critical. communication privacy management (CPM) theory was first introduced by Sandra Petronio in 2002. CPM is evidence-based and accordingly provides a dependable understanding of how decisions are made to disclose and protect private information. This theory uses plain language to understand privacy management in everyday life. CPM focuses on the relationship people have with each other in communicative contexts, such as face-to-face interactions, on social media, and in dyads or groups. CPM theory is based on a communicative-social behavioral perspective and not necessarily a legal point of view. CPM theory illustrates that privacy is not paradoxical but is sustainable through the process of a privacy management system used in everyday life. The theory of CPM has been employed in a number of contexts shedding light on antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of private information management. In addition, a number of researchers across multiple countries, such as the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Japan, Kenya, South Korea, and the United States, have used CPM theory in their research investigations. Learning more about the system of private information management allows for a better understanding of how people navigate managing their private information when others are involved. Literature illustrates patterns of privacy management and demonstrates the challenges as well as the positive outcomes of the way individuals regulate their private information.

- Related Documents

Cybervetting and the Public Life of Social Media Data

The article examines whether and how the ever-evolving practice of using social media to screen job applicants may undermine people’s trust in the organizations that are engaging in this practice. Using a survey of 429 participants, we assess whether their comfort level with cybervetting can be explained by the factors outlined by Petronio’s communication privacy management theory: culture, gender, motivation, and risk-benefit ratio. We find that respondents from India are significantly more comfortable with social media screening than those living in the United States. We did not find any gender-based differences in individuals’ comfort with social media screening, which suggests that there may be some consistent set of norms, expectations, or “privacy rules” that apply in the context of employment seeking—irrespective of gender. As a theoretical contribution, we apply the communication privacy management theory to analyze information that is publicly available, which offers a unique extension of the theory that focuses on private information. Importantly, the research suggests that privacy boundaries are not only important when it comes to private information, but also with information that is publicly available on social media. The research identifies that just because social media data are public, does not mean people do not have context-specific and data-specific expectations of privacy.

Managing the virtual boundaries: Online social networks, disclosure, and privacy behaviors

Online social networks are designed to encourage disclosure while also having the ability to disrupt existing privacy boundaries. This study assesses those individuals who are the most active online: “Digital Natives.” The specific focus includes participants’ privacy beliefs; how valuable they believe their personal, private information to be; and what risks they perceive in terms of disclosing this information in a fairly anonymous online setting. A model incorporating these concepts was tested in the context of communication privacy management theory. Study findings suggest that attitudinal measures were stronger predictors of privacy behaviors than were social locators. In particular, support was found for a model positing that if an individual placed a higher premium on their personal, private information, they would then be less inclined to disclose such information while visiting online social networking sites.

Manajemen Privasi Jemaat Ahmadiyah di Kota Semarang

Abstrak: Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk menggambarkan perilaku komunikasi Jemaat Ahmadiyah dalam posisi mereka sebagai kelompok yang dilarang menyebarkan ajarannya. Dengan menggunakan teori manajemen privasi komunikasi yang diperkenalkan oleh Sandra Petronio, penelitian ini berusaha menjelaskan proses dialektis yang dilakukan oleh jemaat Ahmadiyah di kota Semarang ketika berinteraksi dengan banyak orang dalam kehidupan sehari-hari. Hasil penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa Jemaat Ahmadiyah melakukan pembukaan informasi privat dengan komunikasi langsung dan tidak langsung. Jemaat Ahmadiyah melakukan pembukaan informasi privat bertujuan untuk mengklarifikasi kesalahpahaman ghair tentang Ahmadiyah. Jemaat Ahmadiyah kota Semarang cenderung menutup informasi privat mereka kepada keluarga dan teman ketika mereka baru berbai’at. Mereka juga menutup informasi privat kepada orang-orang Muhammadiyah, serta kepada kelompok-kelompok Islam garis keras, seperti FPI, LDII, termasuk juga kader PKS. Tetapi mereka membuka informasi mengenai Ahmadiyah kepada orang-orang dari kalangan NU, dan aparatur pemerintah. Abstract : This research aims to describe the behavior of Ahmadiyyah community in their position as a group that is prohibited from spreading its teachings. Using the communication privacy management theory introduced by Sandra Petronio, this research attempts to explain the dialectical process undertaken by the Ahmadiyah community in the Semarang city while interacting with many people in everyday life. The results of this study indicate that the Ahmadiyyah community conducts the opening of private information with direct and indirect communication. The Ahmadiyah community conducted the opening of private information aimed to clarify misunderstanding about “ghair” of Ahmadiyah. The Ahmadiyah community of Semarang tends to hide their private information from family and friends when they are newly banned. They also hide private informations to Muhammadiyah people, as well as to hard-line Islamic groups, such as FPI, LDII, as well as PKS cadres. But they do not hide information about Ahmadiyyah to people from the NU, and the government apparatus.

Exploring societal-level privacy rules for talking about miscarriage

Communication privacy management (CPM) theory posits that culturally specific understandings of privacy guide how people manage private information in everyday conversations. We use the context of miscarriage to demonstrate how societal-level expectations about (in)appropriate topics of talk converge with micro-level decisions about privacy rules and privacy boundary management. More specifically, we explore how people’s perceptions of broad social rules about the topic of miscarriage influence their disclosure decisions. Based on interviews with 20 couples who have experienced pregnancy loss, we examined how couples described miscarriage as a topic that is bound by societal-level expectations about whether and how this subject should be discussed in interpersonal conversations. Participants reflected on their perceptions of societal-level privacy rules for protecting information about their miscarriage experiences and described how these rules affected their own privacy management decisions. We discuss these findings in terms of CPM’s theoretical tools for linking macro-level discourses to everyday talk.

Openings offers specific tools to assist the nurse in traversing the challenging yet profoundly rewarding moments of transition that require the clinical practice of intimate openings with the patient/family. Replacing evasion with an opportunity to move into tension and avoidance is essential in helping a patient/family receive palliative care. Observations of tension might be clear indications of a needed transition in care. Complex interactions with patients and families coincide with transitions in care and require intimate and disclosive exchanges among patient/family and nurses. Communication privacy management theory helps us understand more about private information and how that information depends on the relationship people share. Communicating a transition to palliative care from hospital to home or to end-of-life care and hospice requires nurses to address a patient’s/family’s fears and feelings of hopelessness and to provide education about palliative care and its services. Facilitating appropriate access to private health information, creating intimate openings to process transitions in life and care, and understanding the impact of disclosure on patient/family relationships all play an important role.

Communication Privacy Management in Open Adoption Relationships: Negotiating Co-ownership across In-person and Mediated Communication

Open adoption relationships are rife with privacy dilemmas and fuzzy boundaries, which require ongoing coordination of private disclosures as a result. The present study employed communication privacy management (CPM) theory to examine adoptive parents’ ( N = 354) private disclosures with the birth family across in-person and mediated (i.e., texting and social media) contexts. SEM analysis revealed that adoptive families who were more private and were concerned about the birth family sharing private information with others viewed disclosures to the birth family as risky. These privacy concerns related to adoptive parents being more clear with the birth family about preferences for sharing that private information with others. More social media contact between birth and adoptive parents predicted increased perceptions of risk of disclosure to birth parents. Results advance CPM theorizing by underscoring the motivational bases of perceived risk, the importance of anticipated boundary turbulence, and the nuanced privacy management processes within communication modes.

Communication Privacy Management Theory and Health and Risk Messaging

Communication privacy management theory (CPM) argues that disclosure is the process by which we give or receive private information. Private information is what people reveal. Generally, CPM theory argues that individuals believe they own their private information and have the right to control said information. Management of private information is not necessary until others are involved. CPM does not limit an understanding of disclosure by framing it as only about the self. Instead, CPM theory points out that when management is needed, others are given co-ownership status, thereby expanding the notion of disclosing information; the theory uses the metaphor of privacy boundary to illustrate where private information is located and how the boundary expands to accommodate multiple owners of private information. Thus, individuals can disclose not only their own information but also information that belongs to others or is owned by collectives such as families. Making decisions to disclose or protect private information often creates a tension in which individuals vacillate between sharing and concealing their private information. Within the purview of health issues, these decisions have a potential to increase or decrease risk. The choice of disclosing health matters to a friend, for example, can garner social support to cope with health problems. At the same time, the individual may have concerns that his or her friend might tell someone else about the health problem, thus causing more difficulties. Understanding the tension between disclosing and protecting private health information by the owner is only one side of the coin. Because disclosure creates authorized co-owners, these co-owners (e.g., families, friends, and partners) often feel they have right to know about the owner’s health conditions. The privacy boundaries are used metaphorically to indicate where private information is located. Individuals have both personal privacy boundaries around health information that expands to include others referred to as “authorized co-owners.” Once given this status, withholding to protect some part of the private information can risk relationships and interfere with health needs. Within the scheme of health, disclosure risks and privacy predicaments are not experienced exclusively by the individual with an illness. Rather, these risks prevail for a number of individuals connected to a patient such as providers, the patient’s family, and supportive friends. Everyone involved has a dual role. For example, the clinician is both the co-owner of a patient’s private health information and holds information within his or her own privacy boundary, such as worrying whether he or she diagnosed the symptoms correctly. Thus, there are a number of circumstances that can lead to health risks where privacy management and decisions to reveal or conceal health information are concerned. CPM theory has been applied in eleven countries and in numerous contexts where privacy management occurs, such as health, families, organizations, interpersonal relationships, and social media. This theory is unique in offering a comprehensive way to understand the relationship between the notion of disclosure and that of privacy. The landscape of health-related risks where privacy management plays a significant role is both large and complex. The situations of HIV/AIDS, cancer care, and managing patient and provider disclosure of private information help to elucidate the ways decisions of privacy potentially lead to health risks.

To Reveal or Conceal: Using Communication Privacy Management Theory to Understand Disclosures in the Workplace

A sample of 103 full-time employees from various organizations and industries completed an online, open-ended survey to explore and understand the decisions people make to manage their private disclosures at work. Communication privacy management theory was used to understand the management of private information. Results indicate that core and catalyst criteria motivate people to reveal/conceal at work, such as boundary maintenance based on organizational culture, relational considerations, a desire for feedback, and risk/benefit considerations. People also used implicit/explicit rules, reiteration of privacy rules, and retaliation to limit and respond to turbulence. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed along with limitations and directions for future research.

Communication privacy management of students in Latvia

The lack of communication privacy boundaries among students and the fault of self-disclosure are two main reasons for unforeseen distress, broken relationships and trust, vulnerability and conflicts in universities. Based on S. Petronio’s theory of communication privacy management this research investigates the interaction of domestic students and foreign students in Latvia with their peers in order to set up privacy and disclosure boundaries that do not violate peer privacy, especially in a sensitive multicultural context. In fact, the presence of private information and the willingness to disclose it is often confronted with numerous privacy dilemmas and issues regarding their secureness, especially in universities where peers are young with different cultural backgrounds. This article analyzes the privacy management skills of locals and foreigners and reveals how security of information is managed between them stemming from social penetration and communication privacy management theory. Privacy management is significant in facing the dilemma of communication privacy and facilitates solving already existing problems of privacy among students

Communication Privacy Management and Mediated Communication

Communication privacy management theory (CPM) was originally developed to explain how individuals control and reveal private information in traditional social interactions. It has since been extended to a number of contexts, most recently to evolving communication technologies and social networking sites. CPM provides a set of theoretical tools to explore the intersection of technology and individual privacy in relationship management. This chapter introduces CPM; privacy is defined, the three primary components and eight axioms of CPM are reviewed, and their application to mediated communication contexts are outlined. Areas for future research are presented.

Export Citation Format

Share document.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

IUPUI IUPUI IUPUI

- Meet the Theorist

- Roots of CPM

- Directors and Affiliates

- CPM Theory Glossary of Terms

- Classroom Exercises

- CPM Theory Clarity

- CPM Citation List

- CPM Publication of the Month

Communication Privacy Management Center

Let's talk theory.

What does CPM theory explain?

Communcation Privacy Management theory explains how people make choices about their private information through communication with others (Petronio, 2002, 2007, 2013) .

What do you need to know about where CPM is coming from?

CPM is a well-used theory grounded in real-world evidence. Despite how we talk about privacy sometimes, there are both benefits and risks to opening up our private information to others. Privacy management helps us balance the need to be open and receive benefits like support from others, while enjoying the autonomy that comes from keeping our private information to ourselves.

What is privacy ownership?

People believe they own their private information. This ownership is marked by a line, a metaphorical boundary between public and private. When the metaphorical boundary is very thin and permeable, people are more likely to disclose private information. When a boundary is thick, the line between public and private is impermeable, or thick and the information is heavily guarded. When people open up a privacy boundary, allowing others access to the private information, they give authorized co-ownership of that information to others (Petronio, 2013) .

What is privacy control?

When a person tells another private information, they expect to keep total control over their private information. Therefore, when another individual gains access private information, they assume co-ownership of information, and thus, the responsibility to control the information. To manage risks of private information, people use rules to regulate the flow of private information (Petronio, 2013) .

What is privacy turbulence?

Human communication is flawed, and these communication processes do not always unfold perfectly. At times, confidants may break rules about the management of private information. When these violations occur, boundary turbulence arises. This turbulence has the potential to disrupt relationships and guide future decisions about to whom to open a privacy boundary.

Where does CPM unfold?

CPM processes can be witnessed in contexts including computer-mediated communication, health, family, organizations, and in interpersonal and intercultural relationships. To learn more about how CPM is studied in these contexts, visit the CPM Center Practice page.

What is recalibration?

Recalibration occurs when there is privacy turbulence. People change the privacy rules to deal with the breakdown, realigning their privacy management system.

Communication Privacy Management Center social media channels

IU School of Liberal Arts Communication Privacy Management Center

- email: [email protected] phone: 317-278-5620 755 West Michigan Street University Library, Suite 2102 Indianapolis, IN 46202-5195

Communication Privacy Management Theory : Significance for Interpersonal Communication

Citation Count

Privacy antecedents for SNS self-disclosure

Disclosing too much situational factors affecting information disclosure in social commerce environment, extent of private information disclosure on online social networks: an exploration of facebook mobile phone users, relational uncertainty, partner interference, and privacy boundary turbulence explaining spousal discrepancies in infertility disclosures, students' perceptions and communicative management of instructors' online self–disclosure, boundaries of privacy: dialectics of disclosure, the basics of communication research, ‘feeling caught’ in stepfamilies: managing boundary turbulence through appropriate communication privacy rules, exploring privacy management on facebook: motivations and perceived consequences of voluntary disclosure, brief status report on communication privacy management theory., related papers (5), communication privacy management theory: what do we know about family privacy regulation, communication privacy management theory : understanding families, trending questions (1).

The paper does not provide specific qualitative research questions that can be formulated using the communication privacy management theory.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Communication Privacy Management Theory

This essay about Communication Privacy Management (CPM) theory offers a nuanced exploration of how individuals navigate privacy in interpersonal relationships. It highlights the theory’s strengths, such as its recognition of the dynamic nature of privacy and its consideration of contextual influences. Additionally, it discusses the limitations of CPM theory, including its potential oversight of power dynamics and its tendency towards oversimplification. Overall, the essay provides valuable insights into the complexities of privacy management within the realm of human connection.

How it works

Communication Privacy Management (CPM) theory, sculpted by the deft hands of Sandra Petronio, serves as a guiding lantern illuminating the darkened corridors of interpersonal privacy. Picture it as a seasoned cartographer, mapping out the uncharted territories of disclosure and secrecy within the realm of human relationships. Yet, amidst its brilliance, CPM theory reveals both the shimmering treasures and hidden pitfalls of its theoretical landscape.

An advantage of CPM theory lies in its recognition of the dynamic nature of privacy management, akin to the ebb and flow of tides.

It portrays privacy as a living entity, subject to the whims of context and circumstance. Individuals are not mere gatekeepers of their secrets but rather architects of their own boundaries, continually adjusting the sails of disclosure as they navigate the choppy waters of social interaction.

Moreover, CPM theory shines a light on the multifaceted influences that shape our privacy decisions, akin to a prism refracting light into a spectrum of colors. Cultural norms, social roles, and situational factors converge to paint a complex tapestry of privacy management practices. By acknowledging these contextual nuances, CPM theory transcends the confines of individual psychology to encompass the broader landscape of social interaction.

Yet, within the glittering expanse of its theoretical framework, CPM theory harbors its own shadows. One critique is its tendency to overlook the power dynamics that loom over interpersonal communication like silent sentinels. In relationships where power differentials exist, the ability to assert one’s privacy boundaries may be compromised, challenging the assumptions of autonomy embedded within CPM theory.

Furthermore, CPM theory may flatten the nuanced contours of privacy management into a binary landscape of disclosure and concealment. Like a painter reducing a landscape to mere brushstrokes, this oversimplification fails to capture the intricate dance of revelation and reservation that unfolds within the hearts of individuals. By framing privacy management as a series of discrete choices, CPM theory risks obscuring the subtleties of human experience.

In conclusion, Communication Privacy Management theory stands as a beacon in the foggy labyrinth of interpersonal privacy, offering both illumination and shadow. Its recognition of the dynamic interplay between disclosure and secrecy, coupled with an awareness of contextual influences, enriches our understanding of how individuals navigate the delicate balance of intimacy and autonomy in their relationships. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the limitations of CPM theory, including its potential blind spots regarding power dynamics and its tendency towards oversimplification. Like any theoretical framework, CPM theory is a tool to be wielded with care, guiding us through the complexities of human connection while reminding us of the mysteries that lie beyond its reach.

Cite this page

Advantages And Disadvantages Of Communication Privacy Management Theory. (2024, Apr 29). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-communication-privacy-management-theory/

"Advantages And Disadvantages Of Communication Privacy Management Theory." PapersOwl.com , 29 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-communication-privacy-management-theory/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Advantages And Disadvantages Of Communication Privacy Management Theory . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-communication-privacy-management-theory/ [Accessed: 5 May. 2024]

"Advantages And Disadvantages Of Communication Privacy Management Theory." PapersOwl.com, Apr 29, 2024. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-communication-privacy-management-theory/

"Advantages And Disadvantages Of Communication Privacy Management Theory," PapersOwl.com , 29-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-communication-privacy-management-theory/. [Accessed: 5-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Advantages And Disadvantages Of Communication Privacy Management Theory . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-communication-privacy-management-theory/ [Accessed: 5-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Literature review, data analysis, acknowledgment.

- < Previous

Privacy Management and Self-Disclosure on Social Network Sites: The Moderating Effects of Stress and Gender

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Renwen Zhang, Jiawei Sophia Fu, Privacy Management and Self-Disclosure on Social Network Sites: The Moderating Effects of Stress and Gender, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 25, Issue 3, May 2020, Pages 236–251, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmaa004

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A plethora of research has examined the effects of privacy concerns on individuals' self-disclosure on social network sites (SNSs). However, most studies are based on the rational choice paradigm, without taking into account the influence of individuals' emotional states. This study examines the roles of stress in influencing the relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure on SNSs, as well as gender differences in the effects of stress. Results from a survey of 556 university students in Hong Kong suggest that privacy concerns are negatively related to the amount, intimacy, and honesty of self-disclosure on SNSs. Yet a person's level of stress dampens the association between privacy concerns and disclosure amount and intimacy, suggesting that people may worry less about privacy when highly stressed. Moreover, the moderating effect of stress varies based on gender. This study provides insights into the emotional component of privacy management online.

As people reveal large amounts of personal information on social network sites (SNSs), they also face unprecedented challenges to privacy and might become victims of cyberbullying, surveillance, and information or identity theft ( Debatin, Lovejoy, Horn, & Hughes, 2009 ; Taddicken, 2014 ). However, empirical research has revealed a perplexing and sometimes paradoxical relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure—the act of revealing personal information to others—on SNSs. While some studies find that privacy concerns may inhibit self-disclosure on SNSs ( Baruh, Secinti, & Cemalcilar, 2017 ; Krasnova, Spiekermann, Koroleva, & Hildebrand, 2010 ), others show a disconnect between privacy concerns and online disclosure ( Taddicken, 2014 ), which is known as the “privacy paradox” ( Barnes, 2006 ). In attempts to unravel the privacy paradox, studies in recent years have drawn attention to the privacy calculus, suggesting that individuals are inclined to disclose personal information when they perceive more benefits than privacy risks ( Dienlin & Metzger, 2016 ; Krasnova et al., 2010 ).

The privacy calculus is largely grounded in the rational choice paradigm, viewing individuals as rational agents who make cost-benefit calculations to decide upon the best course of action ( Coleman & Coleman, 1994 ). Yet little is known about how emotional factors may affect individuals' privacy management practices, in spite of a general understanding that emotions can distort reasoning ( Schwarz, 2000 ). Prior work suggests that when going through stressful situations such as divorce and injury, individuals tend to modify their privacy rules to meet their immediate needs ( Petronio, 2002 ). Echoing this view, researchers have found large amounts of SNS disclosures about negative or sensitive experiences such as mental illnesses and pregnancy loss ( Andalibi, Morris, & Forte, 2018 ; Bazarova, Choi, Whitlock, Cosley, & Sosik, 2017 ). Despite a direct association between stress and self-disclosure on SNSs ( Zhang, 2017 ), it remains unclear how stress may interact with privacy concerns in predicting disclosure behavior. Understanding the interplay between privacy concerns and stress may shed light on the underexplored emotional components of privacy management.

Apart from stress, individuals' self-disclosure and privacy management online may also vary based on gender. According to the Communication Privacy Management (CPM) theory ( Petronio, 2002 ), men and women define the nature of their privacy differently and thus develop dissimilar rules for regulating privacy boundaries. For example, women generally express more privacy concerns and engage in more proactive privacy protection behavior than men ( Fogel & Nehmad, 2009 ; Hoy & Milne, 2010 ). Some studies show that privacy concerns influence female users' online disclosure more than male users' ( Taddicken, 2014 ), whereas others report the opposite ( Chai, Das, & Rao, 2011 ; Sheehan, 1999 ). Given these inconsistent findings, we have limited understanding of how gender may influence the relationship between privacy concerns and SNS disclosures, especially when emotional factors come into play.

This study aims to examine how stress and gender may influence the relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure on SNSs. Specifically, we explore the interaction between privacy concerns and perceived stress in predicting individuals' self-disclosure on SNSs, including its amount, intimacy, honesty, and intent. We also investigate gender differences in the relationships between privacy, stress, and SNS disclosures. This study serves as a first attempt to interrogate the emotional component of privacy management on SNSs.

Privacy concerns and self-disclosure on SNSs

Self-disclosure is a crucial building block of interpersonal relationships ( Greene, Derlega, & Mathews, 2006 ; Jourard, 1971 ). Studies show that self-disclosure can foster trust and intimacy, leading to relationship development and maintenance ( Greene et al., 2006 ; Taylor & Altman, 1987 ). Yet self-disclosure also carries risks of information loss and privacy violations ( Acquisti & Gross, 2006 ), which can lead to cyberbullying, surveillance, and information or identity theft ( Debatin et al., 2009 ). Therefore, scholars have devoted extensive attention to examining how concerns about how privacy may influence self-disclosure online ( Dienlin & Metzger, 2016 ; Dienlin & Trepte, 2015 ; Krasnova et al., 2010 ).

However, extant research has yielded inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure on SNSs. Some studies have found privacy concerns to be negatively related to SNSs disclosures ( Baruh et al., 2017 ; Brandtzæg, Lüders, & Skjetne, 2010 ; Krasnova et al., 2010 ; Vitak, 2012 ), whereas others show that privacy concerns have little bearing on self-disclosure ( Acquisti & Gross, 2006 ; Norberg, Horne, & Horne, 2007 ; Taddicken, 2014 ; Tufekci, 2008 ). Researchers have therefore posited that self-disclosure is based on a cost-benefit tradeoff, or a privacy calculus ( Dienlin & Metzger, 2016 ; Dinev & Hart, 2006 ; Krasnova et al., 2010 ). Individuals tend to reveal personal information when their anticipated benefits outweigh perceived costs such as privacy risks.

Despite a plethora of research on online privacy, scholars have primarily viewed self-disclosure as a unidimensional construct, with a majority of research focusing on the amount or frequency of self-disclosure ( Bol et al., 2018 ; Dienlin & Trepte, 2015 ; Tufekci, 2008 ). Few studies have examined whether more nuanced aspects of self-disclosure, such as intimacy and honesty, may change due to privacy concerns ( Masur, 2018 ; Vitak, 2012 ). Mounting evidence suggests that individuals tend to engage in strategic disclosure and deliberately create, rather than completely curtail, content shared on SNSs in order to minimize potential risks while maintaining sociality ( Hogan, 2010 ; Marwick & Boyd, 2011 ). Only by taking different dimensions of self-disclosure into account can we gain a complete picture of users' disclosure behavior online.

In fact, traditional studies have viewed self-disclosure as a multidimensional construct. Cozby (1973 ) identified three basic dimensions of self-disclosure: breadth, depth, and duration. This was extended by Wheeless and Grotz (1976) , who posited that self-disclosure varied along five dimensions—amount, intimacy, honesty, intent, and valence. Amount refers to the frequency and duration of disclosure; intimacy indicates the depth of disclosed information; honesty refers to the accuracy of disclosure; intent is self-awareness when disclosing; and valence indicates whether the information is positive or negative. This conceptualization accounts for great variability in disclosure behavior and has been widely used in SNS research ( Gibbs, Ellison, & Heino, 2006 ; Leung, 2002 ; Zhang, 2017 ), but not in studies about online privacy.

Following Wheeless and Grotz's (1976) conceptualization, this study focuses on four dimensions of self-disclosure: amount, intimacy, honesty, and intent. Research shows that these four dimensions have significant impact on relational outcomes ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ) and psychological well-being of individuals ( Zhang, 2017 ), while the influence of valence is somewhat ambiguous. Thus, people might adjust these four dimensions of disclosure based on their privcay concerns. In the next section, we discuss the theoretical framework used for understanding the ways in which people manage their self-disclosure and privacy online.

Communication privacy management theory

One of the most influential and elaborate theories about privacy is CPM theory ( Petronio, 2002 ). Building on Altman's (1975) conceptualization of privacy as a dialectic boundary regulation process, CPM theory posits that people have competing needs of revealing information (self-disclosure) and concealing information (privacy), and they handle this dialectical tension by establishing privacy boundaries and rules ( Petronio, 2002 ). CPM consists of three core elements: (a) privacy ownership, (b) privacy control, and (c) privacy turbulence ( Petronio, 2013 ). Privacy ownership pertains to individuals' perceived boundaries of their private information. They control the flow of private information by developing and negotiating a set of privacy rules depending on various factors. When these rules break down, privacy turbulence occurs. This compels individuals to recalibrate their privacy rules to avoid future turbulence.

A central tenet of CPM is that people rely on a rule-based system to control the flow of private information ( Petronio, 2002 ). They develop privacy rules to determine when, where, how, and with whom it is appropriate to share a piece of private information, typically based on criteria such as gender, culture, context, motivation, and risk–benefit ratio. For example, privacy needs are often higher in Western countries than in Asian cultures ( de Munck & Korotayev, 2007 ; Kim, 2005 ). Although CPM was developed in offline contexts, it has been widely employed to study the use of SNSs ( Stutzman & Kramer-Duffield, 2010 ; Waters & Ackerman, 2011 ). However, some of the underlying assumptions of CPM such as the rule-based privacy management have not been sufficiently supported by empirical evidence, partly due to the difficulty of operationalizing privacy boundaries and rules ( Masur, 2018 ).

One possible way to operationalize privacy rules is by considering the multidimensionality of self-disclosure. In discussing boundary permeability, CPM suggests that “rules that control permeability are manifested in the depth, breadth, and amount of private information that is revealed” ( Petronio, 2002 , p. 99). This echoes the multifaceted nature of self-disclosure discussed in the previous section. Hence, people may regulate their privacy by controlling the characteristics of their disclosure, including amount, intimacy, honesty, and intent. Based on a meta-review of SNS research ( Baruh et al., 2017 ), we first propose that privacy concerns are negatively related to the amount of self-disclosure on SNSs. Second, we hypothesize that privacy concerns are inversely related to the intimacy of disclosure, as users often avoid sharing overly intimate and private content on SNSs to maintain their privacy ( Brandtzæg et al., 2010 ). Third, we propose that people with more privacy concerns may present a less honest description of themselves online, as previous studies have suggested (e.g., Taddicken, 2014 ). Finally, since individuals tend to strategically and purposefully construct their SNS posts to mitigate risks ( Marwick & Boyd, 2011 ), we hypothesize that people with more privacy concerns will engage in more intentional self-disclosure online. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1: Individuals who have more privacy concerns will engage in: (a) less frequent, (b) less intimate, (c) less honest, and (d) more intentional self-disclosure on SNSs.

Bounded rationality and the moderating role of stress

While privacy concerns may inhibit self-disclosure, the story is much more complex. Masur (2018) developed the theory of situational privacy and self-disclosure, suggesting that the specific circumstances determine a person's levels of privacy and self-disclosure. This situational perspective on privacy echoes CPM theory ( Petronio, 2002 ), suggesting that contextual factors such as traumatic events have a critical role to play in influencing how people manage their privacy. When going through unpleasant or disruptive circumstances such as divorce and injury, disclosure is a clear way to cope. Thus, individuals tend to modify their privacy rules based on such situations and may even break them entirely ( Petronio, 2002 ).

Indeed, stressful life events can serve as a catalyst of self-disclosure ( Bazarova & Choi, 2014 ; Zhang, 2017 ). Studies have found SNSs are an outlet for negative emotions and feelings. For example, individuals tend to share stigmatized or sensitive experiences such as mental illness, pregnancy loss, and sexual abuse on SNSs ( Andalibi et al., 2018 ; Bazarova et al., 2017 ; Moreno et al., 2011 ). This might be explained by the fever model of disclosure, which posits that individuals who experience distress are prompted to disclose their distress to others ( Stiles, 1987 ). Extending the fever model to SNS contexts, Zhang (2017) found stressful life events to be positively associated with intimate and intentional self-disclosure on Facebook. This finding corresponds to the work by Bazarova and Choi (2014) , suggesting that Facebook posts driven by self-expression and stress relief goals were more intimate than disclosures for gaining social validation.

The role of stress and emotion in individuals' privacy regulation processes is implied but underexplored in CPM theory. As Petronio (2010) puts it, “when a person has high emotional needs to disclose, the privacy rules characteristic for that person change to accommodate the individual's need to vent those emotions to others” (p. 192). She likewise acknowledged the role of sadness, anger, and depression in affecting privacy rules ( Petronio, 2010 ). The emotional aspect of self-disclosure problematizes existing privacy research assuming that individuals have perfect rationality and evaluate probabilities and possible consequences of events when it comes to the decision making ( Coleman & Coleman, 1994 ). Indeed, Simon (1955) contended that human beings have bounded rationality: when making decisions, human rationality is constrained by the cognitive limitations of the mind and the time and information available. All these factors can affect individuals' decision with respect to privacy ( Acquisti & Grossklags, 2005 ). Instead, people often rely on heuristics and mental shortcuts to deal with uncertain and complex issues ( Carey & Burkell, 2009 ; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974 ).

In light of the emotional aspect of individual decision making, it is reasonable to posit that a person's emotional state may affect the relationship between their privacy concerns and self-disclosure. While Zhang (2017) explored the main effect of stress on self-disclosure on SNSs, we extend this research by examining how stress moderates the relationship between privacy concerns and SNS disclosures. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2: A high level of stress will weaken the relationship between privacy concerns and the: (a) amount, (b) intimacy, (c) honesty, and (d) intent of self-disclosure on SNSs.

Gender differences in privacy management and self-disclosure

CPM theory also posits that men and women define the nature of their privacy differently and thus develop dissimilar rules for regulating privacy boundaries ( Petronio, 2002 ). In particular, evidence suggests that women are more willing to reveal personal information than men ( Parker & Parrott, 1995 ), especially intimate information such as feelings ( Derlega, Durham, Gockel, & Sholis, 1981 ). However, other studies have found no or minor gender differences in the amount of self-disclosure offline ( Shapiro & Swensen, 1977 ) or online ( Barak & Gluck-Ofri, 2007 ). Moreover, research has shown gender differences in the type of information revealed. For instance, Tufekci (2008) found that women were more prone to disclose their favorite music, books, and religion on their SNS profiles, whereas men provided their phone numbers more often than women.

Gender differences in self-disclosure are often explained by the gender role theory ( Eagly & Karau, 2002 ). Gender roles reflect shared expectations about what men and women ideally should do (i.e., injunctive norms) and about how men and women typically behave (i.e., descriptive norms). Gender roles can result in sex-typed social behavior through internationalization of ideal selves and social reinforcement of role-conforming behaviors ( Eagly & Karau, 2002 ). In his early discussion on gender and disclosure, Jourard (1971 ) contends that the male role requires men to “appear tough, objective, striving, achieving, unsentimental, and emotionally unexpressive” (p. 35), which might inhibit their ability to disclose the entire breadth and depth of their inner experience to others. Therefore, men and women use distinct criteria for disclosure and privacy rule-making to meet gender-specific expectations ( Petronio, 2002 ).

Gender differences also exist in online privacy concerns and privacy protection behavior. Studies have found that women generally express more privacy concerns than men ( Fogel & Nehmad, 2009 ; Sheehan, 1999 ), engage in more proactive privacy protection behavior ( Hoy & Milne, 2010 ), but possess fewer technical skills to protect their privacy ( Park, 2015 ). When weighing the benefits and risks of online self-disclosure, women tend to care more about privacy risks while men value benefits more ( Sun, Wang, Shen, & Zhang, 2015 ).

However, there is mixed evidence regarding gender differences in the impact of privacy concerns on self-disclosure. Some studies show that privacy concerns affect female users' self-disclosure more than male users' ( Taddicken, 2014 ), while others report the opposite ( Chai et al., 2011 ; Sheehan, 1999 ). Moreover, Baruh et al.'s (2017) meta-analysis reveals no moderating effect of gender on self-disclosure. Given these conflicting findings, we ask the following research question (RQ):

RQ1: What is the effect of gender on the hypothesized relationships? That is, how does gender moderate the relationship between privacy concerns, stress, and self-disclosure on SNSs?

Procedure and participants

Paper-based surveys were conducted at a public research university in Hong Kong. Following a stratified sampling method, we first randomly selected two to three departments out of the eight departments, and then randomly picked two to three classes with more than 50 students from each department. A total of 17 classes were selected. After obtaining prior approvals from course instructors, we conducted the survey in classrooms in April 2016. Informed consents were obtained from the participants. Five-hundred and seventy-three students completed the survey, with a response rate of 67.4%. Among these participants, 560 (97.7%) were Facebook users and were included in the final sample. It is important to note that this study drew on the same data set as the paper by Zhang (2017) . To clarify the differences between the two papers, we have provided an ethics statement as online supplementary material (OSM). 1

Of the 560 participants, 60.7% were female and 39.3% were male. Most (98.2%) of the students were between 18- and 25-years-old. The sample consisted of 29.6% freshmen, 30.5% sophomore, 24.2% junior, and 15.8% senior. About half (49.5%) of the participants majored in social science and humanities and the rest majored in science and engineering. At the time of the research, 48.6% lived on campus and 51.4% lived off campus.

To ensure factorial validity and reliability, confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were run for each variable. Drawing on common goodness-of-fit (GOF) criteria by Kline (2015) , we found that all measures showed good validity and reliability; the overall model also achieved a good fit (see Table 1 ). To implement open science practices, all data, questionnaire items, CFAs, and analysis scripts were provided as OSM.

Self-disclosure on Facebook

An adapted General Disclosiveness Scale ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ; Wheeless and Grotz, 1976 ; Zhang, 2017 ) was used to measure the multidimensionality of self-disclosure on Facebook. Participants who had a Facebook profile were instructed to think about the updates they post on Facebook and then indicate their self-disclosure behavior on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. CFA results showed a good model fit and confirmed the four subscales of Facebook self-disclosure: amount, intimacy, honesty, and intent (see Table 1 ).

Level of stress

Based on prior work and pre-survey focus group sessions, we developed a list of 11 stressful life events and asked participants to rate the relative stressfulness of each event on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = did not occur/not stressful, 5 = extremely stressful). We first ran CFA on these 11 items, which revealed a poor GOF, suggesting that this scale may not be unidimensional. Building on Zhang's (2017) categorization of three types of life stressors, we regarded stressful life events as a second-order measure with four sub-dimensions: academic, interpersonal, environmental, and health stressors (eight items). CFA results showed a good model fit and confirmed the four-dimensional measure (see Table 1 ). The OSM lists the selected and deleted items.

Privacy concerns

We used three items from Vitak's (2012) study to gauge privacy concerns. Participants reported their concerns about access of personal information by strangers on a scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Psychometric Properties of the Study Variables

Note: a Kline (2015 ); α = Cronbach's alpha; CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted.

A binary variable was created to indicate the gender of participants (1 = male , 0 = female ). The questionnaire also included a third choice “Other,” which no participant marked and thus was dropped.

Control variables

We also included five control variables in the analyses. Given that the frequency of Facebook use has been found to predict individuals' self-disclosure ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ), we asked participants to report the amount of time on average they spent on Facebook per day in the past week on a six-point scale (0 = less than 10 minutes, 1 = 10–30 minutes, 2 = 31–60 minutes, 3 = 1–2 hours, 4 = 2–3 hours, 5 = more than 3 hours). Second, we gauged participants' Facebook network size, measured by the reported number of Facebook friends on a six-point scale (0 = less than 10, 1 = 11–100, 2 = 101–200, 3 = 201–300, 4 = 301–400, 5 = more than 400). Because this variable was skewed (skewness = −.72), we used natural log to transform it. Also, we collected basic demographic information, including age, major, and residence.

Determining an appropriate sample size in survey research is critical. However, there is no consensus on the sample size requirements for structural equation modeling (SEM)—the main data analysis technique in this research. Scholars have proposed varied rules of thumb, including: (a) a minimum sample size of 100 to 150 ( Anderson & Gerbing, 1988 ; Muthén & Muthén, 2002 ), (b) 5 cases or observations per indicator variable ( Bentler & Chou, 1987 ), and (c) 10–20 cases or observations per indicator variable ( Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994 ). In this study, we adopted the strictest criteria of 10–20 cases per variable. Given that we had a total of 19 indicator variables and five control variables, our sample size ( n = 560) was satisfactory.

Moreover, we conducted a power analysis, which showed that a sample size of n = 1293 was needed to test our hypotheses with a power of 95% and an alpha level of 5%, assuming that the effects were at least small (i.e., beta = .10). With the current sample size of n = 560, the achieved power was only 66%. Thus, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine the effect sizes we can reliably interpret. The analysis showed that this study can reliably detect actually existing effects of a size of beta = .12 in 80% of all cases, which was deemed acceptable ( Cohen, 1988 ). Any values below this threshold are not considered as support for our hypotheses, because the results are not sufficiently trustworthy.

We tested our hypotheses and examined the RQ using SEM. Four cases with missing values were treated with listwise deletion, resulting in a final sample size of 556. To estimate effect sizes, the correlation coefficient r was used, where .5 signals large effects, .3 represents medium effects, and .1 describes small effects ( Cohen, 1988 ). Multicollinearity was not an issue in this study because the variance inflation factors (VIFs) of all variables were all below 1.5, significantly lower than the cut-off of 10 ( Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2013 ). For the analyses, we used the software R (version 3.5.1) and R packages such as lavaan. We ran separate models to test the main effect (H1) and the interaction effect (H2) in the full model and gender-specific analyses. To compare whether the effects differ across gender, we established invariance between the two groups (male and female) for all measurement models. Note that in the structural model, we used the predicted factor scores for privacy and stress based on CFA in order to create their interaction term, but retained the measurement model for self-disclosure. The SEM results using predicted factor scores did not differ from those using the measurement models for all variables (see the OSM).

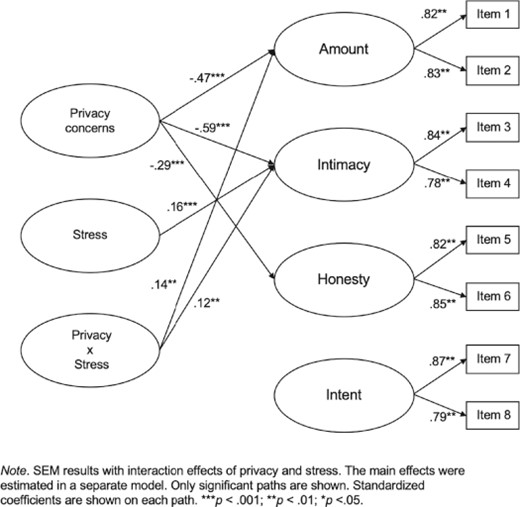

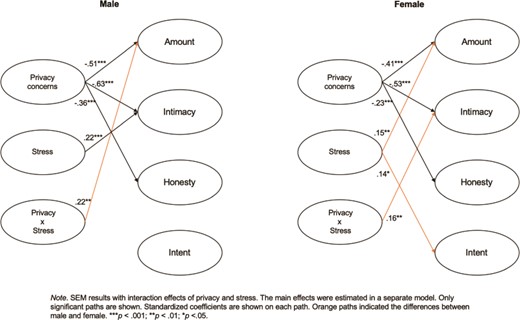

SEM results for the full model (with the interaction term) showed good fit ( |${\chi}^2$| = 145.18, df = 46, |${\chi}^2/ df$| = 3.15, P < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = .92, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .02), indicating that our model provided a good representation of the actual data. The two separate models for men and women were acceptable ( |${\chi}^2$| = 280.50, df = 92, |${\chi}^2$| /df = 3.05, P < .001, CFI = .93, TLI = .85, RMSEA = .086, SRMR = .03). Although the GOF for the separate models was not optimal, it is still considered a moderate model fit based on Kline's (2015) criteria. Figure 1 and Figure 2 provide visual presentations of the three models.

SEM results for all respondents (n = 556).

A comparison of SEM results for male (n = 216) vs. female (n = 340).

H1 proposed that individuals with more privacy concerns had: (a) less frequent, (b) less intimate, (c) less honest, and (d) more intentional self-disclosure on SNSs. The results showed that privacy concerns were negatively associated with disclosure amount ( B = −.69, SE = .06, β = −.47, CI[−.82, −.57], P < .001), intimacy ( B = −.68, SE = .05, β = −.59, CI[−.77, −.58], P < .001) and honesty ( B = −.45, SE = .07, β = −.29, CI[−.59, −.31], P < .001), but was not related to intent ( B = .04, SE = .08, β = .02, CI[−.12, .20], P = .61), lending support to H1a, H1b, and H1c. The standardized coefficients indicated that these effects were medium to large.

H2 proposed that stress moderated the relationship between privacy concerns and the amount, intimacy, honesty, and intent of self-disclosure on SNSs. The results confirmed that stress moderated the relationship between privacy concerns and disclosure amount ( B = .83, SE = .25, β = .14, CI[.33, 1.33], P = .001), and the association between privacy concerns and disclosure intimacy ( B = .61, SE = .19, β = .12, CI[.23, .99], P = .002). As such, highly stressed individuals with high privacy concerns were more likely to self-disclose frequently and intimately than less stressed individuals with the same level of concerns. Thus, H2 was partly supported. The standardized coefficients showed that the effects were small.

To investigate RQ1, we created two SEM models for male and female users (see Figure 2 ). The negative associations between privacy concerns and disclosure amount, intimacy, and honesty held for both men and women. Further Wald tests of coefficient invariance revealed that the influence of privacy on self-disclosure amount ( |${\chi}^2$| = 1.08, P = .30), intimacy ( |${\chi}^2$| = 2.50, P = .11), and honesty ( |${\chi}^2$| = 1.01, P = .32) did not vary significantly across men and women.

However, the results revealed three notable differences between male and female users. First, when men were highly stressed, they tended to disclose more frequently despite privacy concerns than those who were less stressed ( B = 1.45, SE = .43, β = .22, CI[.61, 2.30], P = .001). For highly-stressed women, they were more likely to disclose intimately in spite of high privacy concerns ( B = .75, SE = .26, β = .16, CI[.24, 1.26], P = .005). Second, while stress was positively related to the intimacy of self-disclosure for both men ( B = .79, SE = .22, β = .21, CI[.35, 1.23], P < .001) and women ( B = .41, SE = .15, β = .15, CI[.11, .71], P = .007), it was also associated with the amount ( B = .57, SE = .19, β = .16, CI[.19, .95], P = .004) and intent of disclosure ( B = .63, SE = .26, β = .13, CI[.12, 1.14], P = .016) for women. Finally, the variances explained by our model on disclosure amount ( R 2 male = .42, R 2 female = .24), intimacy ( R 2 male = .51 vs. R 2 female = .32), and honesty ( R 2 male = .18, R 2 female = .13) were larger for men than for women. In contrast, the variance explained by our model on disclosure intent ( R 2 female = .24, R 2 male = .12) was larger for women than for men.

This purpose of this study is to interrogate how stress and gender may affect the relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure on SNSs. The results revealed that stress had an overriding effect on privacy concerns: while privacy concerns were negatively related to the amount, intimacy, and honesty of self-disclosure on SNSs, perceived stress moderated this relationship. Specifically, the more stress individuals experienced, the less negative the association between privacy concerns and disclosure amount and intimacy became. Gender differences also existed. For male users, stress weakened the relation between privacy concerns and disclosure amount . By contrast, for female users, stress weakened the link between privacy concerns and disclosure intimacy . This study makes important contributions to social media and privacy research in three ways.

First, by featuring the multidimensionality of self-disclosure, this study provides a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between privacy concerns and online disclosure. While previous research on online privacy primarily focused on the frequency or amount of online disclosure ( Bol et al., 2018 ; Dienlin & Trepte, 2015 ; Tufekci, 2008 ), this study goes beyond the commonly studied aspect of online disclosure and examines the various characteristics of self-disclosure, including amount, intimacy, honesty, and intent. The findings demonstrate that privacy concerns are related to not only how much people disclose on SNSs but how they disclose. In particular, individuals with more privacy concerns had less frequent, less intimate, and less honest self-disclosure on Facebook. This corroborates prior work that reveals a negative association between privacy concerns and online disclosure ( Baruh et al., 2017 ; Dienlin & Metzger, 2016 ), thereby refuting the privacy paradox.

This finding also provides insights into individuals' privacy management strategies in using social media. According to CPM theory ( Petronio, 2002 ), people regulate their private information by establishing privacy boundaries and rules, which manifest in the depth, breadth, and amount of information revealed. In line with this view, Facebook users in our study were likely to adjust the amount and intimacy of their disclosure when privacy concerns were high, possibly as a way to control their privacy boundaries. Particularly, privacy concerns had larger effects on disclosure intimacy than amount and honesty. This raises an intriguing possibility that controlling the depth of disclosure might serve as a more important strategy for individuals to manage and regulate their privacy. In extending CPM theory, we found honesty to be another dimension that people strategize. When individuals had elevated privacy concerns, they were likely to share less accurate personal information, corresponding to prior research suggesting that privacy concerns prevent users from using their real names on SNSs ( Tufekci, 2008 ).