Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 2 Chapter 3: What is Empirical Literature & Where can it be Found?

In Module 1, you read about the problem of pseudoscience. Here, we revisit the issue in addressing how to locate and assess scientific or empirical literature . In this chapter you will read about:

- distinguishing between what IS and IS NOT empirical literature

- how and where to locate empirical literature for understanding diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Probably the most important take-home lesson from this chapter is that one source is not sufficient to being well-informed on a topic. It is important to locate multiple sources of information and to critically appraise the points of convergence and divergence in the information acquired from different sources. This is especially true in emerging and poorly understood topics, as well as in answering complex questions.

What Is Empirical Literature

Social workers often need to locate valid, reliable information concerning the dimensions of a population group or subgroup, a social work problem, or social phenomenon. They might also seek information about the way specific problems or resources are distributed among the populations encountered in professional practice. Or, social workers might be interested in finding out about the way that certain people experience an event or phenomenon. Empirical literature resources may provide answers to many of these types of social work questions. In addition, resources containing data regarding social indicators may also prove helpful. Social indicators are the “facts and figures” statistics that describe the social, economic, and psychological factors that have an impact on the well-being of a community or other population group.The United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) are examples of organizations that monitor social indicators at a global level: dimensions of population trends (size, composition, growth/loss), health status (physical, mental, behavioral, life expectancy, maternal and infant mortality, fertility/child-bearing, and diseases like HIV/AIDS), housing and quality of sanitation (water supply, waste disposal), education and literacy, and work/income/unemployment/economics, for example.

Three characteristics stand out in empirical literature compared to other types of information available on a topic of interest: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/replicability/reproducibility. Let’s look a little more closely at these three features.

Systematic Observation and Methodology. The hallmark of empiricism is “repeated or reinforced observation of the facts or phenomena” (Holosko, 2006, p. 6). In empirical literature, established research methodologies and procedures are systematically applied to answer the questions of interest.

Objectivity. Gathering “facts,” whatever they may be, drives the search for empirical evidence (Holosko, 2006). Authors of empirical literature are expected to report the facts as observed, whether or not these facts support the investigators’ original hypotheses. Research integrity demands that the information be provided in an objective manner, reducing sources of investigator bias to the greatest possible extent.

Transparency and Replicability/Reproducibility. Empirical literature is reported in such a manner that other investigators understand precisely what was done and what was found in a particular research study—to the extent that they could replicate the study to determine whether the findings are reproduced when repeated. The outcomes of an original and replication study may differ, but a reader could easily interpret the methods and procedures leading to each study’s findings.

What is NOT Empirical Literature

By now, it is probably obvious to you that literature based on “evidence” that is not developed in a systematic, objective, transparent manner is not empirical literature. On one hand, non-empirical types of professional literature may have great significance to social workers. For example, social work scholars may produce articles that are clearly identified as describing a new intervention or program without evaluative evidence, critiquing a policy or practice, or offering a tentative, untested theory about a phenomenon. These resources are useful in educating ourselves about possible issues or concerns. But, even if they are informed by evidence, they are not empirical literature. Here is a list of several sources of information that do not meet the standard of being called empirical literature:

- your course instructor’s lectures

- political statements

- advertisements

- newspapers & magazines (journalism)

- television news reports & analyses (journalism)

- many websites, Facebook postings, Twitter tweets, and blog postings

- the introductory literature review in an empirical article

You may be surprised to see the last two included in this list. Like the other sources of information listed, these sources also might lead you to look for evidence. But, they are not themselves sources of evidence. They may summarize existing evidence, but in the process of summarizing (like your instructor’s lectures), information is transformed, modified, reduced, condensed, and otherwise manipulated in such a manner that you may not see the entire, objective story. These are called secondary sources, as opposed to the original, primary source of evidence. In relying solely on secondary sources, you sacrifice your own critical appraisal and thinking about the original work—you are “buying” someone else’s interpretation and opinion about the original work, rather than developing your own interpretation and opinion. What if they got it wrong? How would you know if you did not examine the primary source for yourself? Consider the following as an example of “getting it wrong” being perpetuated.

Example: Bullying and School Shootings . One result of the heavily publicized April 1999 school shooting incident at Columbine High School (Colorado), was a heavy emphasis placed on bullying as a causal factor in these incidents (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017), “creating a powerful master narrative about school shootings” (Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017, p. 3). Naturally, with an identified cause, a great deal of effort was devoted to anti-bullying campaigns and interventions for enhancing resilience among youth who experience bullying. However important these strategies might be for promoting positive mental health, preventing poor mental health, and possibly preventing suicide among school-aged children and youth, it is a mistaken belief that this can prevent school shootings (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017). Many times the accounts of the perpetrators having been bullied come from potentially inaccurate third-party accounts, rather than the perpetrators themselves; bullying was not involved in all instances of school shooting; a perpetrator’s perception of being bullied/persecuted are not necessarily accurate; many who experience severe bullying do not perpetrate these incidents; bullies are the least targeted shooting victims; perpetrators of the shooting incidents were often bullying others; and, bullying is only one of many important factors associated with perpetrating such an incident (Ioannou, Hammond, & Simpson, 2015; Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017; Newman &Fox, 2009; Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017). While mass media reports deliver bullying as a means of explaining the inexplicable, the reality is not so simple: “The connection between bullying and school shootings is elusive” (Langman, 2014), and “the relationship between bullying and school shooting is, at best, tenuous” (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017, p. 940). The point is, when a narrative becomes this publicly accepted, it is difficult to sort out truth and reality without going back to original sources of information and evidence.

What May or May Not Be Empirical Literature: Literature Reviews

Investigators typically engage in a review of existing literature as they develop their own research studies. The review informs them about where knowledge gaps exist, methods previously employed by other scholars, limitations of prior work, and previous scholars’ recommendations for directing future research. These reviews may appear as a published article, without new study data being reported (see Fields, Anderson, & Dabelko-Schoeny, 2014 for example). Or, the literature review may appear in the introduction to their own empirical study report. These literature reviews are not considered to be empirical evidence sources themselves, although they may be based on empirical evidence sources. One reason is that the authors of a literature review may or may not have engaged in a systematic search process, identifying a full, rich, multi-sided pool of evidence reports.

There is, however, a type of review that applies systematic methods and is, therefore, considered to be more strongly rooted in evidence: the systematic review .

Systematic review of literature. A systematic reviewis a type of literature report where established methods have been systematically applied, objectively, in locating and synthesizing a body of literature. The systematic review report is characterized by a great deal of transparency about the methods used and the decisions made in the review process, and are replicable. Thus, it meets the criteria for empirical literature: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/reproducibility. We will work a great deal more with systematic reviews in the second course, SWK 3402, since they are important tools for understanding interventions. They are somewhat less common, but not unheard of, in helping us understand diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Locating Empirical Evidence

Social workers have available a wide array of tools and resources for locating empirical evidence in the literature. These can be organized into four general categories.

Journal Articles. A number of professional journals publish articles where investigators report on the results of their empirical studies. However, it is important to know how to distinguish between empirical and non-empirical manuscripts in these journals. A key indicator, though not the only one, involves a peer review process . Many professional journals require that manuscripts undergo a process of peer review before they are accepted for publication. This means that the authors’ work is shared with scholars who provide feedback to the journal editor as to the quality of the submitted manuscript. The editor then makes a decision based on the reviewers’ feedback:

- Accept as is

- Accept with minor revisions

- Request that a revision be resubmitted (no assurance of acceptance)

When a “revise and resubmit” decision is made, the piece will go back through the review process to determine if it is now acceptable for publication and that all of the reviewers’ concerns have been adequately addressed. Editors may also reject a manuscript because it is a poor fit for the journal, based on its mission and audience, rather than sending it for review consideration.

Indicators of journal relevance. Various journals are not equally relevant to every type of question being asked of the literature. Journals may overlap to a great extent in terms of the topics they might cover; in other words, a topic might appear in multiple different journals, depending on how the topic was being addressed. For example, articles that might help answer a question about the relationship between community poverty and violence exposure might appear in several different journals, some with a focus on poverty, others with a focus on violence, and still others on community development or public health. Journal titles are sometimes a good starting point but may not give a broad enough picture of what they cover in their contents.

In focusing a literature search, it also helps to review a journal’s mission and target audience. For example, at least four different journals focus specifically on poverty:

- Journal of Children & Poverty

- Journal of Poverty

- Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

- Poverty & Public Policy

Let’s look at an example using the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice . Information about this journal is located on the journal’s webpage: http://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/journals/journal-of-poverty-and-social-justice . In the section headed “About the Journal” you can see that it is an internationally focused research journal, and that it addresses social justice issues in addition to poverty alone. The research articles are peer-reviewed (there appear to be non-empirical discussions published, as well). These descriptions about a journal are almost always available, sometimes listed as “scope” or “mission.” These descriptions also indicate the sponsorship of the journal—sponsorship may be institutional (a particular university or agency, such as Smith College Studies in Social Work ), a professional organization, such as the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) or the National Association of Social Work (NASW), or a publishing company (e.g., Taylor & Frances, Wiley, or Sage).

Indicators of journal caliber. Despite engaging in a peer review process, not all journals are equally rigorous. Some journals have very high rejection rates, meaning that many submitted manuscripts are rejected; others have fairly high acceptance rates, meaning that relatively few manuscripts are rejected. This is not necessarily the best indicator of quality, however, since newer journals may not be sufficiently familiar to authors with high quality manuscripts and some journals are very specific in terms of what they publish. Another index that is sometimes used is the journal’s impact factor . Impact factor is a quantitative number indicative of how often articles published in the journal are cited in the reference list of other journal articles—the statistic is calculated as the number of times on average each article published in a particular year were cited divided by the number of articles published (the number that could be cited). For example, the impact factor for the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice in our list above was 0.70 in 2017, and for the Journal of Poverty was 0.30. These are relatively low figures compared to a journal like the New England Journal of Medicine with an impact factor of 59.56! This means that articles published in that journal were, on average, cited more than 59 times in the next year or two.

Impact factors are not necessarily the best indicator of caliber, however, since many strong journals are geared toward practitioners rather than scholars, so they are less likely to be cited by other scholars but may have a large impact on a large readership. This may be the case for a journal like the one titled Social Work, the official journal of the National Association of Social Workers. It is distributed free to all members: over 120,000 practitioners, educators, and students of social work world-wide. The journal has a recent impact factor of.790. The journals with social work relevant content have impact factors in the range of 1.0 to 3.0 according to Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), particularly when they are interdisciplinary journals (for example, Child Development , Journal of Marriage and Family , Child Abuse and Neglect , Child Maltreatmen t, Social Service Review , and British Journal of Social Work ). Once upon a time, a reader could locate different indexes comparing the “quality” of social work-related journals. However, the concept of “quality” is difficult to systematically define. These indexes have mostly been replaced by impact ratings, which are not necessarily the best, most robust indicators on which to rely in assessing journal quality. For example, new journals addressing cutting edge topics have not been around long enough to have been evaluated using this particular tool, and it takes a few years for articles to begin to be cited in other, later publications.

Beware of pseudo-, illegitimate, misleading, deceptive, and suspicious journals . Another side effect of living in the Age of Information is that almost anyone can circulate almost anything and call it whatever they wish. This goes for “journal” publications, as well. With the advent of open-access publishing in recent years (electronic resources available without subscription), we have seen an explosion of what are called predatory or junk journals . These are publications calling themselves journals, often with titles very similar to legitimate publications and often with fake editorial boards. These “publications” lack the integrity of legitimate journals. This caution is reminiscent of the discussions earlier in the course about pseudoscience and “snake oil” sales. The predatory nature of many apparent information dissemination outlets has to do with how scientists and scholars may be fooled into submitting their work, often paying to have their work peer-reviewed and published. There exists a “thriving black-market economy of publishing scams,” and at least two “journal blacklists” exist to help identify and avoid these scam journals (Anderson, 2017).

This issue is important to information consumers, because it creates a challenge in terms of identifying legitimate sources and publications. The challenge is particularly important to address when information from on-line, open-access journals is being considered. Open-access is not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate scientists may pay sizeable fees to legitimate publishers to make their work freely available and accessible as open-access resources. On-line access is also not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate publishers often make articles available on-line to provide timely access to the content, especially when publishing the article in hard copy will be delayed by months or even a year or more. On the other hand, stating that a journal engages in a peer-review process is no guarantee of quality—this claim may or may not be truthful. Pseudo- and junk journals may engage in some quality control practices, but may lack attention to important quality control processes, such as managing conflict of interest, reviewing content for objectivity or quality of the research conducted, or otherwise failing to adhere to industry standards (Laine & Winker, 2017).

One resource designed to assist with the process of deciphering legitimacy is the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). The DOAJ is not a comprehensive listing of all possible legitimate open-access journals, and does not guarantee quality, but it does help identify legitimate sources of information that are openly accessible and meet basic legitimacy criteria. It also is about open-access journals, not the many journals published in hard copy.

An additional caution: Search for article corrections. Despite all of the careful manuscript review and editing, sometimes an error appears in a published article. Most journals have a practice of publishing corrections in future issues. When you locate an article, it is helpful to also search for updates. Here is an example where data presented in an article’s original tables were erroneous, and a correction appeared in a later issue.

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 12(8): e0181722. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5558917/

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2018).Correction—A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 13(3): e0193937. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0193937

Search Tools. In this age of information, it is all too easy to find items—the problem lies in sifting, sorting, and managing the vast numbers of items that can be found. For example, a simple Google® search for the topic “community poverty and violence” resulted in about 15,600,000 results! As a means of simplifying the process of searching for journal articles on a specific topic, a variety of helpful tools have emerged. One type of search tool has previously applied a filtering process for you: abstracting and indexing databases . These resources provide the user with the results of a search to which records have already passed through one or more filters. For example, PsycINFO is managed by the American Psychological Association and is devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioral science. It contains almost 4.5 million records and is growing every month. However, it may not be available to users who are not affiliated with a university library. Conducting a basic search for our topic of “community poverty and violence” in PsychINFO returned 1,119 articles. Still a large number, but far more manageable. Additional filters can be applied, such as limiting the range in publication dates, selecting only peer reviewed items, limiting the language of the published piece (English only, for example), and specified types of documents (either chapters, dissertations, or journal articles only, for example). Adding the filters for English, peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2010 and 2017 resulted in 346 documents being identified.

Just as was the case with journals, not all abstracting and indexing databases are equivalent. There may be overlap between them, but none is guaranteed to identify all relevant pieces of literature. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the questions asked of the literature:

- Academic Search Complete—multidisciplinary index of 9,300 peer-reviewed journals

- AgeLine—multidisciplinary index of aging-related content for over 600 journals

- Campbell Collaboration—systematic reviews in education, crime and justice, social welfare, international development

- Google Scholar—broad search tool for scholarly literature across many disciplines

- MEDLINE/ PubMed—National Library of medicine, access to over 15 million citations

- Oxford Bibliographies—annotated bibliographies, each is discipline specific (e.g., psychology, childhood studies, criminology, social work, sociology)

- PsycINFO/PsycLIT—international literature on material relevant to psychology and related disciplines

- SocINDEX—publications in sociology

- Social Sciences Abstracts—multiple disciplines

- Social Work Abstracts—many areas of social work are covered

- Web of Science—a “meta” search tool that searches other search tools, multiple disciplines

Placing our search for information about “community violence and poverty” into the Social Work Abstracts tool with no additional filters resulted in a manageable 54-item list. Finally, abstracting and indexing databases are another way to determine journal legitimacy: if a journal is indexed in a one of these systems, it is likely a legitimate journal. However, the converse is not necessarily true: if a journal is not indexed does not mean it is an illegitimate or pseudo-journal.

Government Sources. A great deal of information is gathered, analyzed, and disseminated by various governmental branches at the international, national, state, regional, county, and city level. Searching websites that end in.gov is one way to identify this type of information, often presented in articles, news briefs, and statistical reports. These government sources gather information in two ways: they fund external investigations through grants and contracts and they conduct research internally, through their own investigators. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the topic for which information is sought:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) at https://www.ahrq.gov/

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) at https://www.bjs.gov/

- Census Bureau at https://www.census.gov

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of the CDC (MMWR-CDC) at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index.html

- Child Welfare Information Gateway at https://www.childwelfare.gov

- Children’s Bureau/Administration for Children & Families at https://www.acf.hhs.gov

- Forum on Child and Family Statistics at https://www.childstats.gov

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) at https://www.nih.gov , including (not limited to):

- National Institute on Aging (NIA at https://www.nia.nih.gov

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) at https://www.niaaa.nih.gov

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at https://www.nichd.nih.gov

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at https://www.nida.nih.gov

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at https://www.niehs.nih.gov

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at https://www.nimh.nih.gov

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at https://www.nimhd.nih.gov

- National Institute of Justice (NIJ) at https://www.nij.gov

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at https://www.samhsa.gov/

- United States Agency for International Development at https://usaid.gov

Each state and many counties or cities have similar data sources and analysis reports available, such as Ohio Department of Health at https://www.odh.ohio.gov/healthstats/dataandstats.aspx and Franklin County at https://statisticalatlas.com/county/Ohio/Franklin-County/Overview . Data are available from international/global resources (e.g., United Nations and World Health Organization), as well.

Other Sources. The Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies—previously the Institute of Medicine (IOM)—is a nonprofit institution that aims to provide government and private sector policy and other decision makers with objective analysis and advice for making informed health decisions. For example, in 2018 they produced reports on topics in substance use and mental health concerning the intersection of opioid use disorder and infectious disease, the legal implications of emerging neurotechnologies, and a global agenda concerning the identification and prevention of violence (see http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/Topics/Substance-Abuse-Mental-Health.aspx ). The exciting aspect of this resource is that it addresses many topics that are current concerns because they are hoping to help inform emerging policy. The caution to consider with this resource is the evidence is often still emerging, as well.

Numerous “think tank” organizations exist, each with a specific mission. For example, the Rand Corporation is a nonprofit organization offering research and analysis to address global issues since 1948. The institution’s mission is to help improve policy and decision making “to help individuals, families, and communities throughout the world be safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous,” addressing issues of energy, education, health care, justice, the environment, international affairs, and national security (https://www.rand.org/about/history.html). And, for example, the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation is a philanthropic organization supporting research and research dissemination concerning health issues facing the United States. The foundation works to build a culture of health across systems of care (not only medical care) and communities (https://www.rwjf.org).

While many of these have a great deal of helpful evidence to share, they also may have a strong political bias. Objectivity is often lacking in what information these organizations provide: they provide evidence to support certain points of view. That is their purpose—to provide ideas on specific problems, many of which have a political component. Think tanks “are constantly researching solutions to a variety of the world’s problems, and arguing, advocating, and lobbying for policy changes at local, state, and federal levels” (quoted from https://thebestschools.org/features/most-influential-think-tanks/ ). Helpful information about what this one source identified as the 50 most influential U.S. think tanks includes identifying each think tank’s political orientation. For example, The Heritage Foundation is identified as conservative, whereas Human Rights Watch is identified as liberal.

While not the same as think tanks, many mission-driven organizations also sponsor or report on research, as well. For example, the National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA) in the United States is a registered nonprofit organization. Its mission, along with other partnering organizations, private-sector groups, and federal agencies, is to promote policy and program development in research, prevention and treatment to provide information to, for, and about children of alcoholics (of all ages). Based on this mission, the organization supports knowledge development and information gathering on the topic and disseminates information that serves the needs of this population. While this is a worthwhile mission, there is no guarantee that the information meets the criteria for evidence with which we have been working. Evidence reported by think tank and mission-driven sources must be utilized with a great deal of caution and critical analysis!

In many instances an empirical report has not appeared in the published literature, but in the form of a technical or final report to the agency or program providing the funding for the research that was conducted. One such example is presented by a team of investigators funded by the National Institute of Justice to evaluate a program for training professionals to collect strong forensic evidence in instances of sexual assault (Patterson, Resko, Pierce-Weeks, & Campbell, 2014): https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/247081.pdf . Investigators may serve in the capacity of consultant to agencies, programs, or institutions, and provide empirical evidence to inform activities and planning. One such example is presented by Maguire-Jack (2014) as a report to a state’s child maltreatment prevention board: https://preventionboard.wi.gov/Documents/InvestmentInPreventionPrograming_Final.pdf .

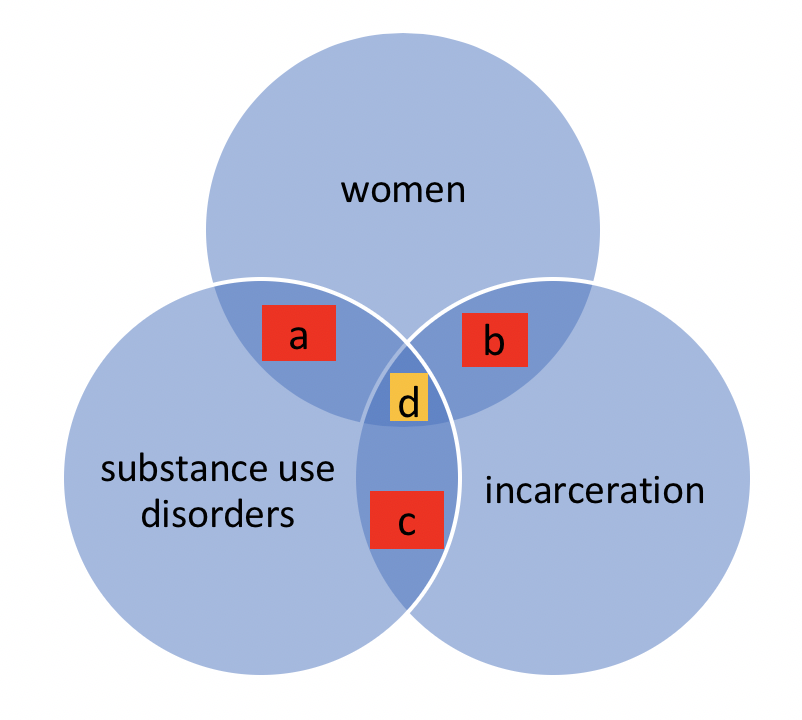

When Direct Answers to Questions Cannot Be Found. Sometimes social workers are interested in finding answers to complex questions or questions related to an emerging, not-yet-understood topic. This does not mean giving up on empirical literature. Instead, it requires a bit of creativity in approaching the literature. A Venn diagram might help explain this process. Consider a scenario where a social worker wishes to locate literature to answer a question concerning issues of intersectionality. Intersectionality is a social justice term applied to situations where multiple categorizations or classifications come together to create overlapping, interconnected, or multiplied disadvantage. For example, women with a substance use disorder and who have been incarcerated face a triple threat in terms of successful treatment for a substance use disorder: intersectionality exists between being a woman, having a substance use disorder, and having been in jail or prison. After searching the literature, little or no empirical evidence might have been located on this specific triple-threat topic. Instead, the social worker will need to seek literature on each of the threats individually, and possibly will find literature on pairs of topics (see Figure 3-1). There exists some literature about women’s outcomes for treatment of a substance use disorder (a), some literature about women during and following incarceration (b), and some literature about substance use disorders and incarceration (c). Despite not having a direct line on the center of the intersecting spheres of literature (d), the social worker can develop at least a partial picture based on the overlapping literatures.

Figure 3-1. Venn diagram of intersecting literature sets.

Take a moment to complete the following activity. For each statement about empirical literature, decide if it is true or false.

Social Work 3401 Coursebook Copyright © by Dr. Audrey Begun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Meriam Library

SWRK 330 - Social Work Research Methods

- Literature Reviews and Empirical Research

- Databases and Search Tips

- Article Citations

- Scholarly Journal Evaulation

- Statistical Sources

- Books and eBooks

What is a Literature Review?

Empirical research.

- Annotated Bibliographies

A literature review summarizes and discusses previous publications on a topic.

It should also:

explore past research and its strengths and weaknesses.

be used to validate the target and methods you have chosen for your proposed research.

consist of books and scholarly journals that provide research examples of populations or settings similar to your own, as well as community resources to document the need for your proposed research.

The literature review does not present new primary scholarship.

be completed in the correct citation format requested by your professor (see the C itations Tab)

Access Purdue OWL's Social Work Literature Review Guidelines here .

Empirical Research is research that is based on experimentation or observation, i.e. Evidence. Such research is often conducted to answer a specific question or to test a hypothesis (educated guess).

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

These are some key features to look for when identifying empirical research.

NOTE: Not all of these features will be in every empirical research article, some may be excluded, use this only as a guide.

- Statement of methodology

- Research questions are clear and measurable

- Individuals, group, subjects which are being studied are identified/defined

- Data is presented regarding the findings

- Controls or instruments such as surveys or tests were conducted

- There is a literature review

- There is discussion of the results included

- Citations/references are included

See also Empirical Research Guide

- << Previous: Citations

- Next: Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 8:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csuchico.edu/SWRK330

Meriam Library | CSU, Chico

A systematic literature review of empirical research on quality requirements

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 08 February 2022

- Volume 27 , pages 249–271, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Thomas Olsson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2933-1925 1 ,

- Séverine Sentilles ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0165-3743 2 &

- Efi Papatheocharous ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5157-8131 1

5245 Accesses

10 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Quality requirements deal with how well a product should perform the intended functionality, such as start-up time and learnability. Researchers argue they are important and at the same time studies indicate there are deficiencies in practice. Our goal is to review the state of evidence for quality requirements. We want to understand the empirical research on quality requirements topics as well as evaluations of quality requirements solutions. We used a hybrid method for our systematic literature review. We defined a start set based on two literature reviews combined with a keyword-based search from selected publication venues. We snowballed based on the start set. We screened 530 papers and included 84 papers in our review. Case study method is the most common (43), followed by surveys (15) and tests (13). We found no replication studies. The two most commonly studied themes are (1) differentiating characteristics of quality requirements compared to other types of requirements, (2) the importance and prevalence of quality requirements. Quality models, QUPER, and the NFR method are evaluated in several studies, with positive indications. Goal modeling is the only modeling approach evaluated. However, all studies are small scale and long-term costs and impact are not studied. We conclude that more research is needed as empirical research on quality requirements is not increasing at the same rate as software engineering research in general. We see a gap between research and practice. The solutions proposed are usually evaluated in an academic context and surveys on quality requirements in industry indicate unsystematic handling of quality requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Requirements quality research: a harmonized theory, evaluation, and roadmap

Julian Frattini, Lloyd Montgomery, … Michael Unterkalmsteiner

Empirical research on requirements quality: a systematic mapping study

Lloyd Montgomery, Davide Fucci, … Walid Maalej

Quality in model-driven engineering: a tertiary study

Miguel Goulão, Vasco Amaral & Marjan Mernik

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Quality requirements—also known as non-functional requirements—are requirements related to how well a product or service is supposed to perform the intended functionality [ 48 ]. Examples are start-up time, access control, and learnability [ 56 ]. Researchers have long argued the importance of quality requirements [ 39 , 68 , 82 ]. However, to what extent have problems and challenges with quality requirements been studied empirically? A recent systematic mapping study identified quality requirements as one of the emergent areas of empirical research [ 7 ]. There are several proposals over the years for how to deal with quality requirements, e.g., the NFR method [ 78 ], QUPER [ 87 ], quality models [ 37 ], and i* [ 107 ]. However, to what extent have they been empirically validated? We present a systematic literature review of empirical studies on problems and challenges as well as validated techniques and methods for quality requirements engineering.

Ambreen et al. conducted a systematic mapping study on empirical research in requirements engineering [ 7 ], published in 2018. They found 270 primary studies where 36 papers were categorized as research on quality requirements. They concluded that empirical research on quality requirements is an emerging area within requirements engineering. Berntsson Svensson et al. carried out a systematic mapping study on empirical studies on quality requirements [ 15 ], published in 2010. They found 18 primary empirical studies on quality requirements. They concluded that there is a lack of unified view and reliable empirical evidence, for example, through replications and that there is a lack of empirical work on prioritization in particular. In our study, we follow up on the systematic mapping study om Ambreen et al. [ 7 ] by performing a systematic literature review in one of the highlighted areas. Our study complements Berntsson Svensson et al. study from 2010 by performing a similar systematic literature review 10 years later and by methodologically also using a snowball approach.

There exist several definitions of quality requirements as well as names [ 48 ]. Glinz defines a non-functional requirement as an attribute (such as performance or security) or a constraint on the system. The two prevalent terms are quality requirements and non-functional requirements. Both are used roughly as much and usually mean approximately the same thing. The ISO25010 defines quality in use as to whether the solution fulfills the goals with effectiveness, efficiency, freedom from risk, and satisfaction [ 56 ]. Eckhardt et al. analyzed 530 quality requirements and found that they described a behavior—essentially a function [ 40 ]. Hence, the term non-functional might be counter-intuitive. We use the term quality requirements in this paper. In layman’s terms, we mean a quality requirement expresses how well a solution should execute an intended function, as opposed to functional requirements which express what the solution should perform. Furthermore, conceptually, we use the definition from Glinz [ 48 ] and the sub-characteristics of ISO25010 as the main refinement of quality requirements [ 56 ].

We want to understand from primary studies (1) what are the problems and challenges with quality requirements as identified through empirical studies, and (2) which quality requirements solutions have been empirically validated. We are motivated by addressing problems with quality requirements in practice and understanding why quality requirements is still, after decades of research, often reported as a troublesome area of software engineering in practice. Hence, we study which are the direct observations and experience with quality requirements. We define the following research questions for our systematic literature review:

Which empirical methods are used to study quality requirements?

What are the problems and challenges for quality requirements identified by empirical studies?

Which quality requirements solution proposals have been empirically validated?

We study quality requirements in general and therefore exclude papers focusing on specific aspects, e.g., on safety or user experience.

We summarize the related literature reviews in Sect. 2 . We describe the hybrid method we used for our systematic literature review in Sect. 3 . Section 4 elaborates on the findings from screening of 530 papers to finally include 84 papers from the years 1995 to 2019. We discuss the results and threats to validity in Sect. 5 ; empirical studies on quality requirements are—in relative terms—less common than other types of requirements engineering papers, there is a lack of longitudinal studies of quality requirements topics, we found very few replications. We conclude the paper in Sect. 6 with a reflection that there seems to be a divide between solutions proposed in an academic setting and the challenges and needs of practitioners.

2 Related work

A recent systematic mapping study on empirical studies on requirements engineering states that quality requirements are “by far the most active among these emerging research areas” [ 7 ]. They classified 36 papers of the 270 they included as papers in the quality requirements area. In their mapping, they identify security and usability as the most common topics. These results are similar to that of Ouhbi et al. systematic mapping study from 2013 [ 81 ]. However, they had slightly different keywords in their search, including also studies on quality in the requirements engineering area, which is not necessarily the same as quality requirements. A systematic mapping study is suggested for a broader area whereas a systematic literature review for a narrower area which is studies in more depth [ 63 ]. To our knowledge, there are no recent systematic literature reviews on quality requirements.

Berntsson Svensson et al. performed a systematic literature review on empirical studies on managing quality requirements in 2010 [ 15 ]. They identified 18 primary studies. They classified 12 out of the 18 primary studies as case studies, three as experiments, two as surveys, and one as a mix of survey and experiment. They classified only four of the 18 studies as properly handling validity threats systematically. Their results indicate that there is a lack of replications and multiple studies on the same or similar phenomena. However, they identify a dichotomy between two views; those who argue that quality requirements need special treatment and others who argue quality requirements need to be handled at the same time as other requirements. Furthermore, they identify a lack of studies on prioritization of quality requirements. Berntsson Svensson et al. limited their systematic literature review to studies containing the keyword “software,” whereas we did not in our study. Furthermore, Berntsson Svensson et al. performed a keyword-based literature search with a number of keywords required to be present in the search set. We used a hybrid approach and relied on snowballing instead of strict keywords. Lastly, we used Ivarsson and Gorschek [ 58 ] for rigor, which entailed stricter inclusion criteria, i.e., as a result we did not include all studies from Berntsson Svensson et al. This, in combination with performing the study 10 years afterward, means we complement Berntsson Svensson both in terms of the method as well as studied period.

Alsaqaf et al. could not find any empirical studies on quality requirements in their 2017 systematic literature review on quality requirements in large-scale agile projects [ 5 ]. They included studies on agile practices and requirements in general. Hence, their scope does not overlap significantly with ours. They found, however, 12 challenges to quality requirements in an agile context. For example, a focus on delivering functionality at the expense of architecture flexibility, difficulties in documenting quality requirements in user stories, and late validation of quality requirements. We do not explicitly focus on agile practices. Hence, there is a small overlap between their study and ours.

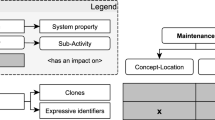

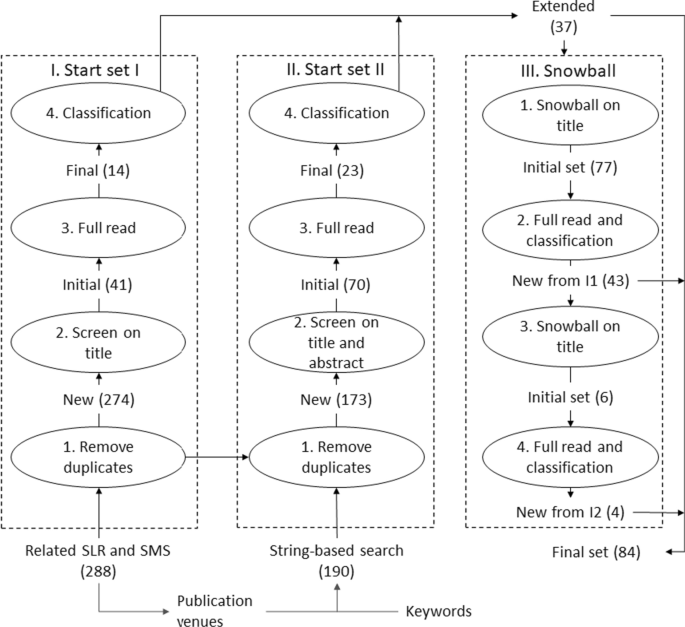

We designed a systematic literature review using a hybrid method [ 77 ]. The hybrid method combines a keyword-based search, typical of a systematic literature review [ 63 ], to define a start set and a snowball method [ 105 ] to systematically find relevant papers. We base our study on two literature reviews [ 7 , 15 ], which we complement in a systematic way. The overall process is found in Fig. 1 .

3.1 Approach

We decided to use a hybrid approach for our literature review [ 77 ]. A standard keyword-based systematic literature review [ 63 ] can result in a very large set of papers to review if keywords are not restrictive. On the other hand, having too restrictive keywords can result in a too-small set of papers. A snowball approach [ 105 ], on the other hand, is sensitive to the start set. If the studies are published in different communities not referencing each other, there is a risk of not finding relevant papers if the start set is limited to one community. Hence, we used a hybrid method where we combine the results from a systematic mapping study and a systematic literature review to give us one start set with a keyword-based search in the publication venues of the papers from the two review papers.

We used two different approaches to create the start sets: Start set I is based on two other literature reviews, and Start set II is created through a keyword-based search in relevant publication venues. The two start sets are combined and snowballed on to arrive at the final set of included papers. The numbers between the steps in each set are the number of references within that set. The numbers between the sets are the total number of references included in the final set

Start set I

We defined Start set I for our systematic literature review by using a systematic mapping study on empirical evidence for requirements engineering in general [ 7 ] from 2018 and a systematic literature review from 2010 [ 15 ] with similar research questions as in our paper.

The systematic literature review from 2010 by Berntsson Svensson et al. includes 18 primary studies [ 15 ]. However, we have different inclusion criteria (see Sect. 3.2 ). Hence, not all the references are included. In our final set, we included 10 of the 18 studies.

The systematic mapping by Ambreem et al. from 2018 looks at empirical evidence in general for requirements engineering [ 7 ]. They included 270 primary studies. However, there are some duplicates in their list. They classified 36 papers to be in the quality requirements area. However, there is an overlap with the Berntsson Svensson et al. review [ 15 ]. When we remove the already included papers from Berntsson Svensson et al., we reviewed 24 from Ambreem et al. and in the end included 4 of them.

Start set II

To complement start set I, we also performed a keyword-based search. We have slightly different research questions than the two papers in the Start set I. Therefore, our search string is slightly different than that of Ambreen et al. and Berntsson Svensson et al. Also, the most recent references in Start set I are from 2014, i.e., five years before we performed our search. Hence, we also fill the gap of the papers published since 2014. We include all studies, not just studies from 2014 and onward, as our method and research questions are slightly different.

We used the most frequent and highly ranked publication venues from Start set I to limit our search but still have a relevant scope. Table 1 summarizes the included conferences and journals. Even though the publication venues included are not an exhaustive list of applicable venues, we believe they are representative venues that are likely to include most communities and thereby reducing the risk with a snowball approach of missing relevant publications, as intended with the hybrid method.

We used Scopus to search. The search was performed in September 2019. Table 2 outlines the components of the search string. The title and abstract were included in the search and only papers that include both the keyword for quality requirements and the keywords for empirical research.

Snowballing

The last step in our hybrid systematic review [ 77 ] is the snowballing of the start set papers. We snowballed on the extended start set—the combination of Start set I and Start set II—to get to our final set of papers (cf. Fig. 1 ). In a snowball approach, both references in the paper (backward references) and papers referring to the paper (forward references) were screened [ 105 ]. We used Google Scholar to find forward references.

3.2 Planning

We arrived at the following inclusion criteria, in a discussion among the researchers and based on related work:

The paper should be on quality requirements or have quality requirements as a central result.

There should be empirical results with a well-defined method and validity section, not just an example or anecdotal experience.

Papers should be written in English.

The papers should be peer-reviewed.

The papers should be primary studies.

Conference or journal should be listed in reference ranking such as SJR.

Similarly, we defined our exclusion criteria as:

Literature reviews, meta-studies, etc.,—secondary studies—are excluded.

If a conference paper is extended into a journal version, we only include the journal version.

We include papers only once, i.e., duplicates are removed throughout the process.

Papers focusing on only specific aspect(s) (security, sustainability, etc.) are excluded.

All researchers were involved in the screening and classification process, even though the primary researcher performed the bulk of the work. The screening and classification were performed as follows:

Screen based on title and/or abstract.

We performed a full read when at least one researcher wanted to include the paper from the screening step.

Papers were classified according to the review protocol, see Sect. 3.3 . This was performed by the primary researcher and validated by another researcher.

To ensure reliability in the inclusion of papers and coding, the process was performed iteratively according to the sets.

For Start set I, all references from the systematic literature review [ 15 ] and systematic mapping study [ 7 ] were screened by two or three researchers. We only used the title in the screening step for Start set I. Full read and classification were performed by two or three researchers.

For Start set II, the screening was primarily performed by the primary researcher but with frequent alignment with at least one more researcher to ensure consistent screening—both on title and abstract. Similarly for the full read and classification of the papers. Specifically, we paid extra attention to which papers to exclude to ensure we did not exclude relevant papers.

The primary researcher performed the snowballing. We screened on title only for backward and forward snowballing. We included borderline cases, to ensure we did not miss any relevant references.

The full read and classification were primarily performed by the primary researcher for Start set II and the Snowballing set. A sample of the papers was read by another researcher to improve validity in addition to those cases already reviewed by more than one researcher.

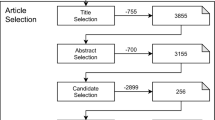

The combined number of primary studies from the systematic literature review [ 15 ] and systematic mapping study [ 7 ] are 288 in Start set I. However, there is an overlap between the two studies and there are some duplicates in the Ambreen et al. paper [ 7 ]. In the end, we had 274 unique papers in Start set I. After the screening, 41 papers remained. After the full read, additional papers were excluded resulting in 14 papers in the Start set I.

Our search in Start Set II resulted in 190 papers. A total of 173 papers remained after removing duplicate papers and papers already included in Start set I. After the screening and full read, the final Start set II was 23. Hence, the extended start set (combining Start set I and Start set II) together resulted in the screening of 447 papers and the inclusion of 37 papers.

The snowball process was repeated until no new papers are found. We iterated 2 times—denoted I1 and I2 in Fig. 1 . In iteration 1, we reviewed 77 papers and included 43. In iteration 2, we reviewed 6 papers and included 4. This resulted in a total of 84 papers included and 530 papers reviewed.

3.3 Classification and review protocol

We developed the review protocol based on the systematic literature review [ 15 ] and systematic mapping study [ 7 ], the methodology papers [ 63 , 105 ], and our research questions. The main items in our protocol are:

Type of empirical study according to Wieringa et al. [ 104 ]. As we are focusing on empirical studies, we use the evaluation type—investigations of quality requirements practices in a real setting—,validation type—investigations of solution proposals before they are implemented in a real setting—,or experience type—studies where the researchers are taking a more part in the study, not just observing.

Method used in the papers. We found the following primary methods used: Experiment, test, case study, survey, and action research.

Analysis of rigor according to Ivarsson and Gorschek [ 58 ].

Thematic analysis of the papers—in an initial analysis based on the author keyword and in later iterations further refined and grouped during the analysis process.

We used a spreadsheet for documentation of the classification and review notes. The classification scheme evolved iteratively (see Sect. 3.2 ) as we included more papers. The initial themes were documented in the review process. In the analysis phase, the initial themes were used for an initial grouping of the papers. The themes were aligned and grouped in the analysis process of the papers, which included a number of meetings and iterative reviews of the results. The final themes which we used for the papers are the results of the iterative analysis process, primarily performed by the first and third researcher.

3.4 Validity

All cases where there were uncertainties whether to include a paper—both in the screening step and the full read step—or on the classification were reviewed by at least two researchers. Furthermore, to ensure consistent use of the inclusion and exclusion criterion as well as the classification we also sampled and reviewed papers that had only been screened or reviewed by only one researcher.

We used Scopus for Start set II. We confirmed that all journals and conferences selected from Start set I were found in Scopus. However, REFSQ was only indexed from 2005 and onward. However, we do not see this as a problem as we are snowballing and the papers that are missing from the Scopus search due to this, should appear in the results through the snowballing process.

We used Google Scholar in the snowballing. This is recommended [ 105 ] and usually gives the most complete results.

A hybrid search strategy can be sensitive to starting conditions, as pointed out by Mourão et al. [ 77 ]. However, their results indicate that the strategy can produce similar results as a standard systematic literature review. We carefully selected the systematic literature review and the systematic mapping study as Start set I and extended it with a keyword-based search for selected forums in Start set II. Hence, we believe the extended start set on which we snowballed is likely to be sufficient to ensure a good result when complemented with the snowball approach.

4 Analysis and results

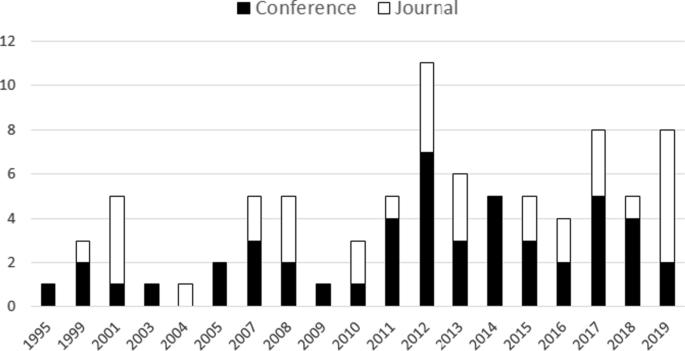

The screening and reading of the papers in Start set I was performed in August and September 2019. The keyword-based search for Start set II was performed in September 2019. The snowballing was subsequently performed in October and November. In total, 530 papers are screened, of which 194 papers are read in full. This resulted in including 84 papers, from 1995 to 2019—see Fig. 2 .

An overview of papers included—publication type and year of publication

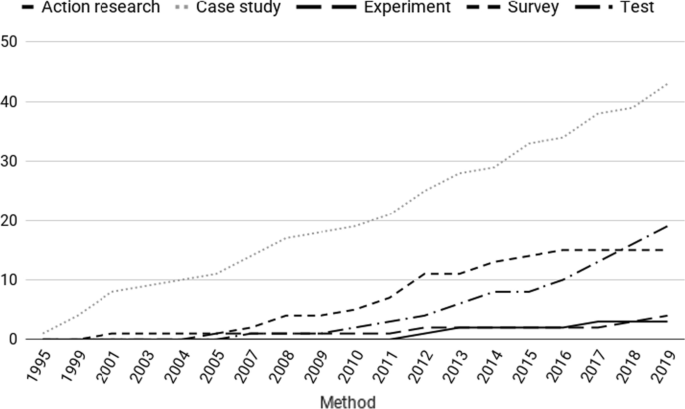

4.1 RQ1 Which empirical methods are used to study quality requirements?

The type of studies performed is found in Table 3 —categorized according to Wieringa et al. [ 104 ]. We differentiate between two types of validations: experiments involving human subjects and tests of algorithms on a data set. For the latter, the authors either report experiment or case study, whereas we call them test. The evaluations we found are either performed as case studies or surveys. Lastly, we found three papers that used action research—categorized as experience in Table 3 . It should be noted that the authors of the action research papers did not themselves explicitly say they performed an action research study. However, when we classified the papers, it is quite clear that, according to Wieringa et al. [ 104 ], they are in the action research category.

Case studies in an industry setting are the most common (35 of 84), followed by surveys in industry (14 of 84) and test in academic settings (13 of 84). This indicates that research on quality requirements is applied and evidence is primarily of individual case studies rather than through validation in laboratory settings. Case studies seem to have similar popularity over time, see Fig. 3 . We speculate that since requirements engineering in general as well as quality requirements in particular is a human-intensive activity, there are not so many clear cause–effect relationships to study in a rigorous experiment. Rather, it is more important to study practices in realistic settings. However, there are only three longitudinal studies.

Tests are, in contrast to the case studies, primarily performed in an academic setting, which is not necessarily representative in terms of scale and artifacts. The papers are published from 2010 to 2019—one exception, published in 2007, see Fig. 3 . One explanation might be the developments in computing driving the trend to use large data sets.

We found only one study on open source, see Table 3 , which is also longitudinal. We speculate that requirements engineering is sometimes seen as a business activity where someone other than the developers decides what should be implemented. In open-source projects, there is often a delegated culture where there is no clear product manager or similar deciding what to do, albeit there can be influential individuals such as the originator or core team member. We believe this entails that quality requirements engineering is different in open-source projects than when managed within an organization. It would be interesting to see if this hypothesis holds for requirements engineering in general and not just quality requirements. We believe, however, that by studying forums, issue management, and reviews that open-source projects are an untapped resource for quality requirements research.

An overview of papers included—method and accumulated number of publications per year

We classify the studies according to rigor, as proposed by Ivarsson and Gorschek [ 58 ]. We assess the design and validity rigor. Table 4 presents our evaluation of design and validity rigor in the papers. An inclusion criterion is that there should be an empirical study, not just examples or anecdotes. Hence, it is not surprising that overall studies score well in our rigor assessment.

High rigor is important for validations studies—to allow for replications—which is also the case for 11 out of 23 studies. The number increases to 13 if we include papers with a rigor score 0.5 for both design and validity and to 19 if we focus solely on the design rigor. Interestingly, we found no replication studies. Furthermore, the number of studies on a single (similar) approach or solution is in general low. We speculate that the originators of a solution have an interest in performing empirical studies on their solution. However, it seems unusual that practitioners or empiricists with no connection to the original solution or approach try to apply it. Furthermore, we also speculate that academic quality requirements research is not addressing critical topics for industry as there seems not to be an interest in applying and learning more about them. This implies that the research on quality requirements might need to better understand what are the real issues facing software developing organizations in terms of quality requirements.

The validity part of rigor is also important for evaluations and experience papers. Strict replications are typically not possible. However, understanding the contextual factors and validity are key in interpreting the results and assessing their applicability in other cases and contexts. 22 of the 58 evaluation and 1 of the 3 experience papers do not have a well-described validity section (rigor score 0), and 10 evaluation and 1 experience paper have a low score (rigor score 0.5). Hence, we conclude that the overall strength of evidence is weak.

4.1.1 Validations

Experiments are, in general, the most rigorous type of empirical study with the most control. However, it is difficult to scale to a realistic scenario. We found four experiments validating quality requirements with human subjects, see Table 5 .

We note that all experiments are performed with students—at varying academic levels. This might very well be appropriate for experiments [ 54 ]. We notice that there are only four experiments, which might be justified by: (1) Experiments as a method is not well accepted nor understood in the community. (2) Scale and context are key factors for applied fields such as requirements engineering, making it more challenging to design relevant experiments.

Several empirical studies study methods or tools by applying them to a data set or document set. We categorize those as tests, see Table 6 . We found three themes for tests.

Automatic analysis—The aim is to evaluate an algorithm or statistical method to automatically analyze a text, usually a requirements document.

Tool—The aim is to evaluate a tool specifically.

Runtime analysis—Evaluating the degree of satisfaction of quality requirements during runtime.

Tests are also fairly rigorous in that it is possible to control the study parameters well. It can also be possible to perform realistic studies, representative of real scenarios. The challenge is often to attain data that is representative. The data set is described in Table 7 .

The most commonly used data set is the DePaul07 data set [ 27 ]. It consists of 15 annotated specifications from student projects at DePaul University from 2007. This data set consists of requirements specification—annotated to functional and quality requirements as well as the type of quality requirement—from student projects.

There are few examples where data from commercial projects have been used. The data do not seem to be available for use by other researchers. There are examples where data from public organizations—such as government agencies—are available and used, e.g., the EU procurement specification, see Table 7 .

The most common type of data is a traditional requirements document, written in structured text. There are also a couple of instances where use case documents are used. For non-requirements specific artifacts, manuals, data use agreements, request for proposals (RFPs), and app reviews are used. From the papers in this systematic literature view, artifacts such as backlogs, feature lists, roadmaps, pull requests, or test documents do not seem to have been included.

4.1.2 Evaluations

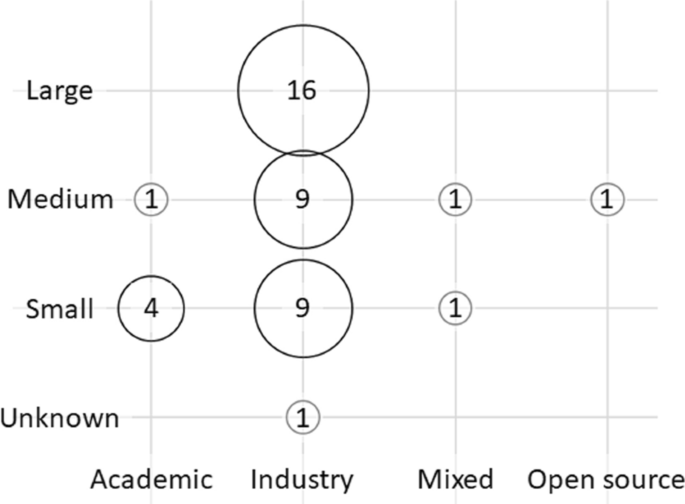

It is usually not possible to have the same rigorous control of all study parameters in case studies [ 38 ]. However, it is often easier to have realistic scenarios, more relevant for a practical setting. We found both case studies performed in an industry context with practitioners as well as in an academic context with primarily students at different academic levels. We found 43 papers presenting case study reports on quality requirements, see Fig. 4 (all details can be found in Table 10 ). We separate case studies that explicitly evaluate a specific tool, method, technique, framework, etc., and exploratory case studies aiming to understand a specific context rather than evaluating something specific.

Case studies sometimes study a specific object, e.g., a tool or method, see Table 10 . We found 25 case studies explicitly studying a particular object. Two objects are evaluated more than once, otherwise just one case study per object. We found no longitudinal cases; hence, the case studies are executed at one point in time and not followed up at a later time. The QUPER method is studied in several case studies in several different contexts (see Table 10 ). There are several case studies for the NFR method; however, it seems the context is similar or the same in most of the cases (row 2).

Overview of the case studies on quality requirements—43 papers of the 84 included in this literature review. Scale refers to the context of the case study—small: sampling parts of the context (e.g., one part of a company) or is overall a smaller context (e.g., example system), medium: sampling a significant part of the context or a larger example system, large: sampling all significant parts of a context of an actual system (not example or made up). The context is also classified according to where the case studies are executed. Academic means primarily by students (at some academic level). Mixed means the case studies are executed in both an academic and industry context. For details, please see Table 10

We found 18 exploratory case studies on quality requirements where a specific object wasn’t the focus, see Table 10 . Rather, the goal is to understand a particular theme of quality requirements. Eight case studies want to understand details of quality requirements, e.g., the prevalence of a specific type of quality requirement or what happens in the lifecycle of a project. Five case studies have studied the process around quality requirements, two studies on sources of quality requirements (in particular app reviews), two studies in particular on developers’ view on quality requirements (specifically using StackOverflow), and lastly one study on metric related to quality requirements. We found two longitudinal case studies.

The goal of a survey is to understand a broader context without performing any intervention [ 38 ]. Surveys can be used either very early in the research process before there is a theory to find interesting hypotheses or late in the process to understand the prevalence of a theme from a theory in a certain population. We found 15 surveys, see Table 8 ; 5 interviews, 9 questionnaires, one both. The goals of the surveys are a mix of understanding practices around the engineering of quality requirements and understanding actual quality requirements as such.

Overall, the surveys we found are small in terms of the sample of the population. In most cases, they do not report from which population they sample. The most common theme is the importance of quality requirements and specific sub-characteristics—typically according to ISO9126 [ 57 ] or ISO25010 [ 56 ]. However, we cannot draw any conclusions as sampling is not systematic and the population unclear. We believe it is not realistic to systematically sample any population and achieve a statistically significant result on how important quality requirements are nor which sub-characteristics are more or less important. We speculate that, besides the sampling challenge, the variance among organizations and point in time will likely be large, making the practical implications of such studies of questionable value.

4.1.3 Experience