- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

What is a Feasibility Study and its Importance?

This blog talks about how a study that assesses the potential success of a proposed project. Let’s dive in to learn how to conduct this study and comprehend what determines the viability of a project. It will help you understand how the Feasibility Study evaluates the necessity of a project in terms of legal aspects. Read more!

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Project and Infrastructure Financing Training

- Waterfall Project Management Certification Course

- Jira Training

- CGPM (Certified Global Project Manager) Course

- Project Management Office Fundamentals Certification Course

A Feasibility Study is a crucial assessment that is during Project Management conducted to determine the viability and potential success of a project. By thoroughly examining such factors, stakeholders can make informed decisions regarding the project’s feasibility. Apart from the technical and financial considerations, this study ensures a project’s compliance with relevant laws, regulations and industry standards. To give you a better overview, this blog will talk about the multiple aspects associated with this. So, let’s dive in to comprehend the significance of a Feasibility Study. After reading this blog, stakeholders can make well-informed decisions that enhance the chances of a project’s success.

Table of Contents

1) Feasibility Study - An overview

2) Importance of a Feasibility Study

3) Types of Feasibility Studies

4) What is included in a Feasibility Study report?

5) Examples of a Feasibility Study

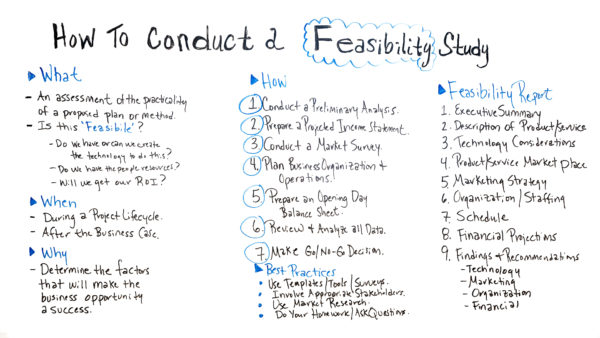

6) Seven steps to do a Feasibility Study

7) Conclusion

Feasibility Study - An overview

A Feasibility Study is an initial investigation into the potential benefits and viability of a project or endeavour. An impartial appraisal that looks at a project's technical, financial, legal, and environmental elements is what this study provides.

Importance of a Feasibility Study

A Feasibility Study may reveal novel concepts that fundamentally alter the Scope of a Project . Feasibility Studies are of the greatest importance in the decision-making process when it comes to projects, businesses, and investments. They are mostly structured assessments that are focused on various aspects of a proposed project`s Feasibility. The following are some of its advantages:

a) Increases the focus of project teams

b) Finds fresh opportunities

c) Gives important information to help make a "go/no-go" choice.

d) Reduces the number of available business options

e) Finds a good cause to start the project

f) Increases the success rate through the assessment of several factors

g) Assists in making project decisions

h) Identifies grounds for not moving forward

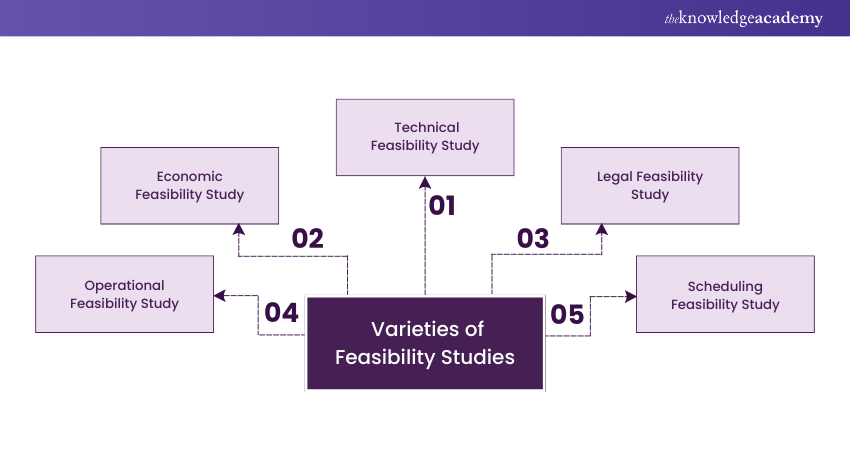

Types of Feasibility Studies

Technical Feasibility Study

A technical Feasibility Study aims to verify whether the organisation is eligible to use its technical in-house resources and expertise to perform successfully. This assessment involves scrutinising various aspects, including the following:

a) Production capacity: Does the company have the resource base to produce that number of products and services for the customers?

b) Facility needs: Will today’s facilities fulfil the standards required, or will new facilities be constructed?

c) Raw materials and supply chain: Are there enough purchases, and have the organisation maintained a supply chain?

d) Regulatory compliance: Does the Project Execution follow the relevant guidelines and professionals bear the relevant certifications to meet the requirements and the industry standards?

Economic Feasibility Study

It is a financial Feasibility Study that primarily examines the project's financial viability. The economic Feasibility Study typically involves several steps:

a) Determining capital requirements: Calculate funding collection, overhead, and other capital.

b) Cost breakdown: Determining and listing all the project costs including the purchase of materials, hardware, labour, and overheard costs are too.

c) Funding sources: Trying out a variety of possible solutions like banks, stakes, or grants.

d) Revenue projection: By using prediction tools such as a cost-benefit analysis or business forecasting to get the level of income, return on investment and profit margin.

e) Financial analysis: Projecting the performance of the Project based on means that are related to a financial analysis and are characterised by the utilisation of such things as cash flow statements, balance sheets and financial projections.

Learn the tools and methods to manage projects by signing up for our Running Small Projects Training now!

Legal Feasibility Study

Legal Feasibility is a type of analysis that seeks to confirm that a pProject follows all the relevant laws and regulations. Key considerations include:

a) Regulatory compliance: Briefing the whole project team about all required laws and regulations that the project has to comply with.

b) Business structure: Assessing the legal systems (e.g., LLCs vs. corporations) that would best protect liability, governance, and minimising taxation, if any.

Operational Feasibility Study

An operational Feasibility Study looks at how effectively a product will meet its needs. It also talks about how easy it will be to use and maintain once it is in place. In addition, this study enumerates the necessity of evaluating a product's utility and the response and suggestions of application development team.

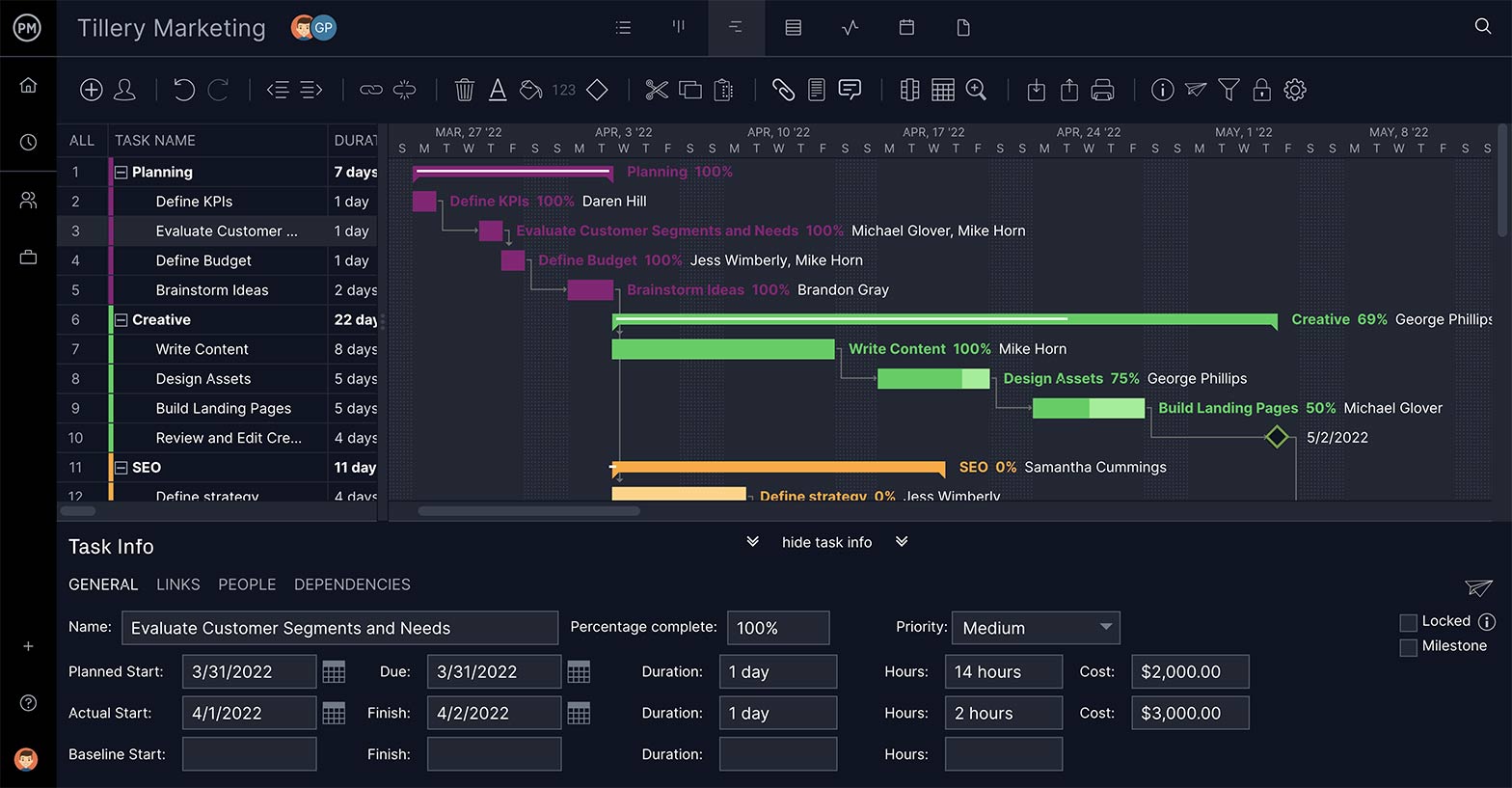

Scheduling Feasibility Study

Proposed project schedules and deadlines are the main subject of a scheduling a Feasibility Study. This evaluation concerns how long team members will need to complete the project. It also highly impacts the business because if the programme isn't finished on time, the planned result might not be realised.

Acquire the necessary skills to effectively deliver projects by signing up for our Project Management Office Fundamentals Training now!

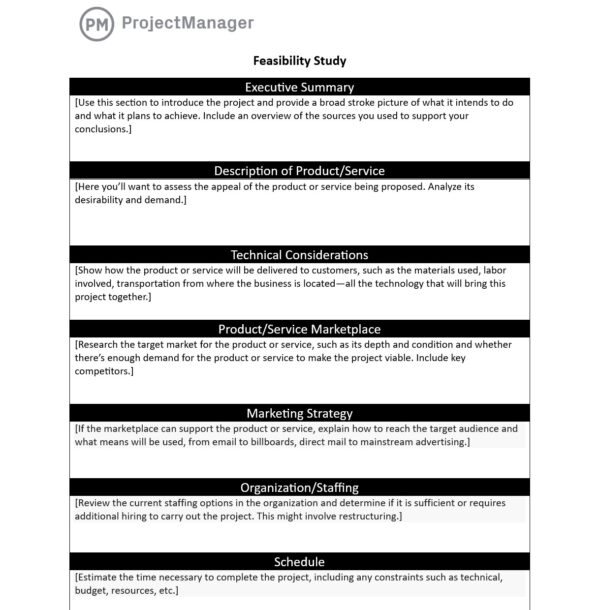

What is included in a Feasibility Study report?

You should make a Feasibility Study report before starting a project. This way you can analyse if your business idea is really viable and will bring you success. When you conduct this study, you would have to consider lots of factors such as if the people are going to buy your product or service, how much competition is out there, if the company can afford it and so on.

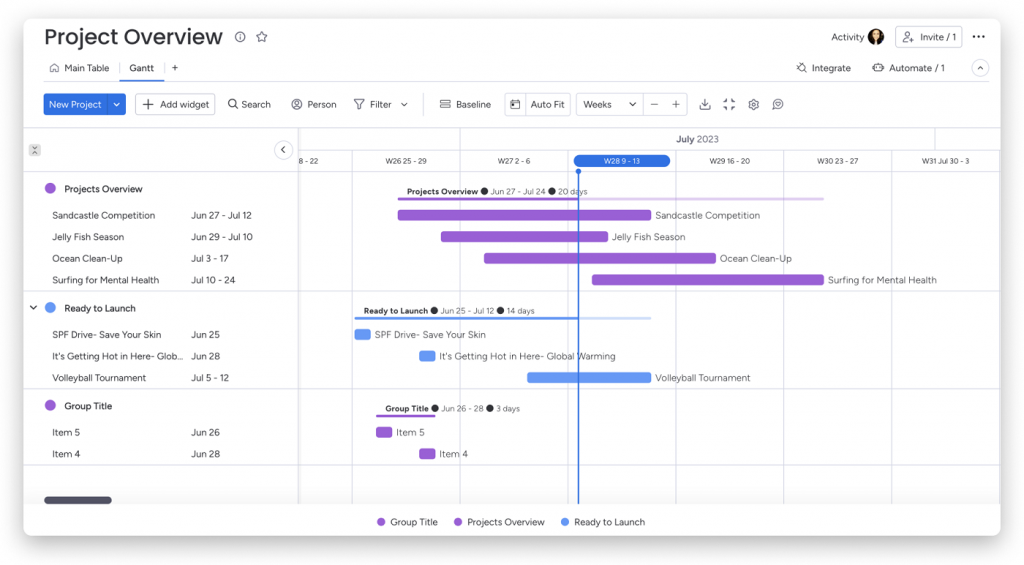

The Feasibility Study must include things like how much technology and resources you need and how much you can hope to earn from your investment. The results of this study are put together in a report, which usually includes the following sections:

a) Executive summary

b) Approach to marketing

c) Organisation/staffing

Examples of a Feasibility Study

Feasibility Study has helped decide if big ideas can work. Here are two examples:

University Science Building Upgrade

This example is about a university that wanted to upgrade its old science building from the 1970s. They thought it was outdated and needed a change. To implement this, they evaluated different options and determined how much they would approximately cost. Some people were worried about the project being too expensive or its potential to causeissues in the community. The study also analysed what technology the new building would require, and how effectively it would help students, and also, if it would attract more students.

Along with this, they looked at the financial aspect too, as to how they would sponsor for it and if they would make more money from having additional students. The study showed that the project could work, so they went ahead with the upgrade.

High-speed Rail Project

This example is timed when the Washington State Department of Transportation wanted to see if they could build a fast train connecting Vancouver, Seattle, and Portland. To initiate this, they first focused on how to make decisions about the project in the future.

They discussed it with several people and groups to ensure everyone was okay with the plan. Later, they looked at how to pay for it and thought it would cost between $24 billion and $42 billion. They would get money from the government and maybe from loans and investors.

The study showed that the train could bring lots of good things like better jobs and less traffic. They started looking into this in 2016 and finished the study in 2020. They then shared the report with the government.

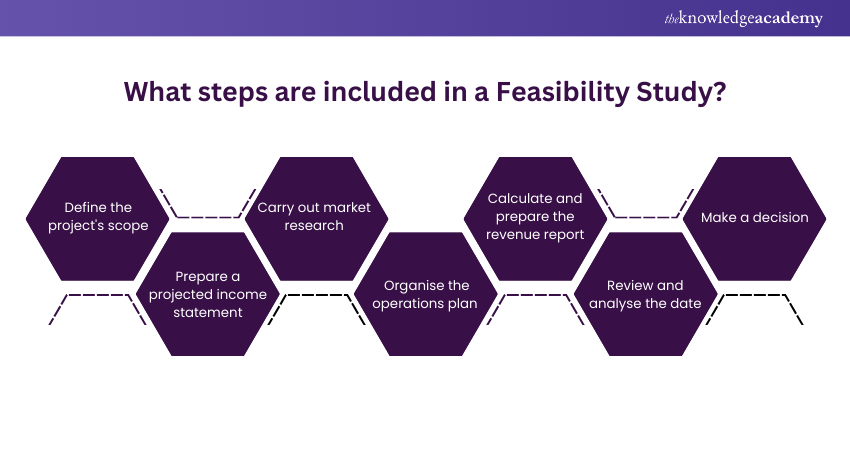

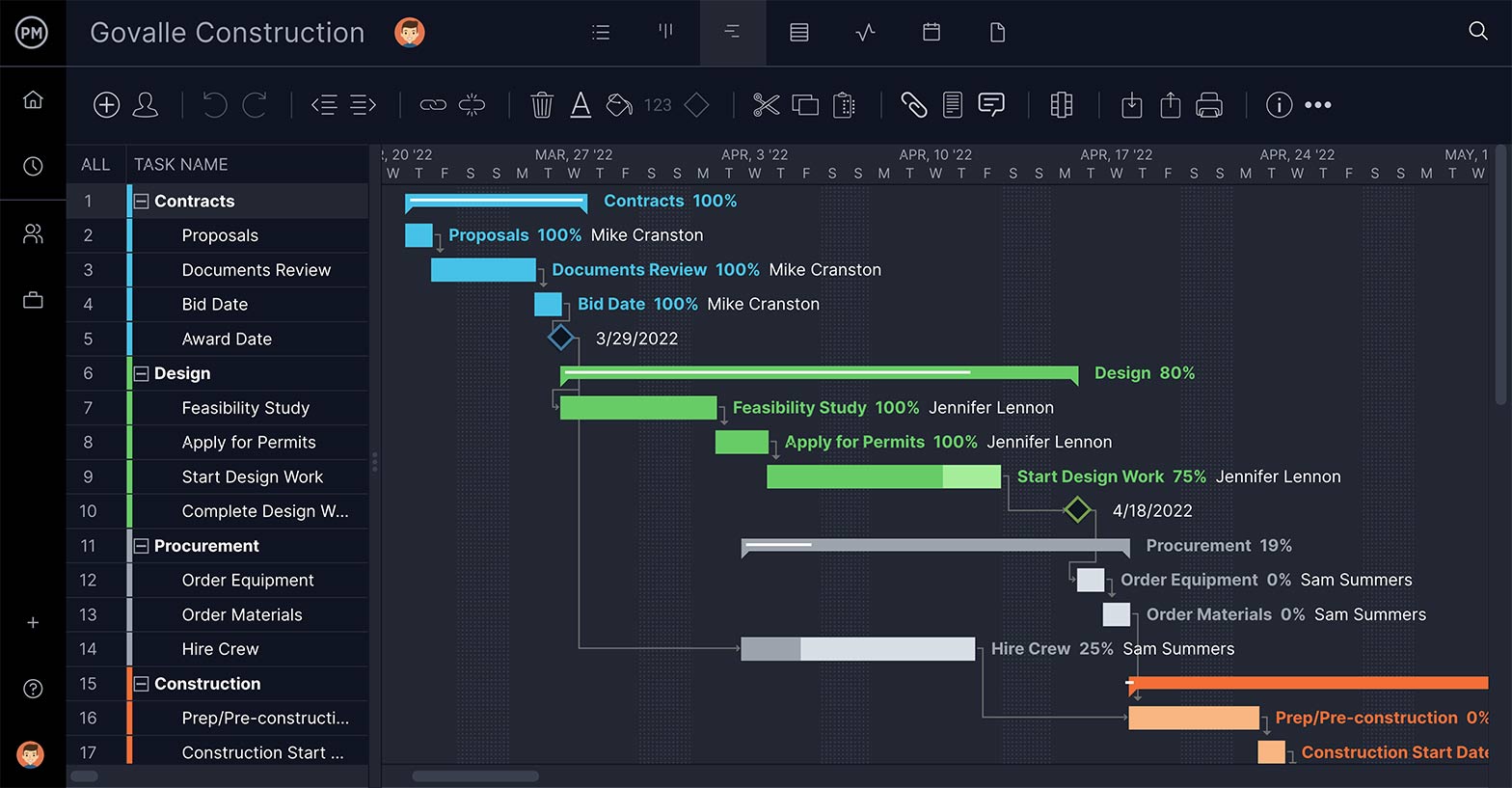

Seven steps to do a Feasibility Study

As Feasibility Study is a crucial step in determining a potential of a project, it involves a substantial period of time and resources. Let’s take you through some of the steps involved in the following points:

1) Do a preliminary analysis and define the scope of the study

Before going through a Feasibility Study, it is wise that you do just one small check. The time and resources involved in Feasibility Studies may be burdensome; hence, it is imperative to determine if it is worth it as early as possible.

Through this form, one can establish whether the study holds awarding potential and who else should be involved on a higher level. You further this stage by answering questions like what you might win, what pitfalls you will face, and what you need for the success of the project.

2) Prepare a projected income statement

First, while doing a Feasibility Study, you should obtain the income statement projection. In this, the statement calculates earnings and expenditures in subsequent one-year amounts. It is made up of the sum of what you will surely get and the cost you will need to cover.

Smaller businesses tend to need marketing strategies to grow into bigger companies. These facts are extremely important because they help business owners make smart decisions regarding the stage of the business.

3) Carry out market research

Market research is of paramount importance or, naturally, it will be of no use when developing the Feasibility Study. Primarily, it operates to ascertain the viability of the project. This point tells you time, which gives you knowledge of the current market state: Who your customers are, who your competitors are, how big the market is, and how many of it you could have. One way of doing this market research is by asking people questions, referring to experts, and checking very broad social media and other public info to find out what's going on.

4) Organisation and operations plan

Once you've figured out how the market behaves and the scope of your organisation, you can draft the setup of your plan. The detailed work plan for the project will provide the answer to how it will work in a practical form. It tests three aspects of your project, like whether it can be run, whether it is cost-effective, whether it complies with the law, and whether the technology fits.

This is to help you comprehend everything you can do and what you may require to get this project going, for example, the equipment, the materials to start the project, additional costs, and if you need to hire or train people. If you need to, you may make that change if the information you have brought is enough.

5) Calculate and prepare the initial balance of expected revenue and expenses

In this step, you must be expert in handling things from the financial part. You’ll make estimates on how much you may initially spend starting up your project, and then how much your project could make and spend based on that estimate. Among the many issues involved are such as the amount of money you are receiving from your customers, money you owe to others and assets that you own.

Fixed costs, such as variable costs that will change based on the number of goods you produce, and equipment costs also need to be factored in money you may borrow or pay for land and service other companies. Keeping this in mind, you should also consider your business’ off seasons and how much risk you are willing to take. These calculations save a lot of time and effort and can be used to answer the most difficult questions of Feasibility.

6) Review and analyse all data

After going through all the steps, it's crucial to do a thorough review and analysis. This helps ensure that everything is in order and there's nothing that needs adjusting. Take a moment to carefully look back at your work, including the income statement, and compare it with your expenses and debts. Ask yourself: Does everything still seem realistic?

This is also the perfect opportunity to consider any risks that might come up and create contingency plans to handle them. By doing this, you'll be better prepared for any unexpected challenges that may arise.

7) Make a go/No-go decision

Now, it's time to decide if the project can work. This might seem simple, but all the work you've done so far leads up to this moment of decision-making. Before making the final call, there are a few more things to think about. First, consider if the project is worth the time, effort, and money you'll be putting into it. Is the commitment worth it?

Secondly, think about whether the project fits with what your organisation wants to achieve in the long run. Does it align with the organisation’s strategic goals and plans? These factors are essential to consider before making your decision.

Attain the skills to become a stellar Project Manager by signing up for our Project Management Courses now!

Conclusion

You are now more familiar with how a well-executed Feasibility Study is a cornerstone of informed decision-making in Project Management and business ventures. It acts as a critical guide, helping organisations assess the practicality and viability of their initiatives, ultimately minimising risks and increasing the likelihood of success.

Frequently Asked Questions

Employers value skills like analysis, problem-solving, attention to detail, and communication in Feasibility Study specialists. They need to be good at crunching numbers, finding solutions, and explaining complex ideas clearly.

Many industries need expertise in Feasibility Studies, like Construction, Healthcare, Tech, and more. It helps decide if projects are doable.

The Knowledge Academy takes global learning to new heights, offering over 30,000 online courses across 490+ locations in 220 countries. This expansive reach ensures accessibility and convenience for learners worldwide.

Alongside our diverse Online Course Catalogue, encompassing 17 major categories, we go the extra mile by providing a plethora of free educational Online Resources like News updates, Blogs , videos, webinars, and interview questions. Tailoring learning experiences further, professionals can maximise value with customisable Course Bundles of TKA .

The Knowledge Academy’s Knowledge Pass , a prepaid voucher, adds another layer of flexibility, allowing course bookings over a 12-month period. Join us on a journey where education knows no bounds.

The Knowledge Academy offers various Project Management Courses , including Introduction to Project Management Certification Course and Project Management Masterclass. These courses cater to different skill levels, providing comprehensive insights into Project Resource Management .

Our Project Management Blogs cover a range of topics related to Project Management Skills, offering valuable resources, best practices, and industry insights. Whether you are a beginner or looking to advance your skills in Project Management, The Knowledge Academy's diverse courses and informative blogs have you covered.

Upcoming Project Management Resources Batches & Dates

Fri 21st Jun 2024

Fri 19th Jul 2024

Fri 16th Aug 2024

Fri 13th Sep 2024

Fri 11th Oct 2024

Fri 8th Nov 2024

Fri 13th Dec 2024

Fri 10th Jan 2025

Fri 14th Feb 2025

Fri 14th Mar 2025

Fri 11th Apr 2025

Fri 9th May 2025

Fri 13th Jun 2025

Fri 18th Jul 2025

Fri 15th Aug 2025

Fri 12th Sep 2025

Fri 10th Oct 2025

Fri 14th Nov 2025

Fri 12th Dec 2025

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest spring sale.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Business Analysis Courses

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Microsoft Project

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is a Feasibility Study?

Understanding a feasibility study, how to conduct a feasibility study, the bottom line.

- Business Essentials

Feasibility Study

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Group1805-3b9f749674f0434184ef75020339bd35.jpg)

Yarilet Perez is an experienced multimedia journalist and fact-checker with a Master of Science in Journalism. She has worked in multiple cities covering breaking news, politics, education, and more. Her expertise is in personal finance and investing, and real estate.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YariletPerez-d2289cb01c3c4f2aabf79ce6057e5078.jpg)

A feasibility study is a detailed analysis that considers all of the critical aspects of a proposed project in order to determine the likelihood of it succeeding.

Success in business may be defined primarily by return on investment , meaning that the project will generate enough profit to justify the investment. However, many other important factors may be identified on the plus or minus side, such as community reaction and environmental impact.

Although feasibility studies can help project managers determine the risk and return of pursuing a plan of action, several steps should be considered before moving forward.

Key Takeaways

- A company may conduct a feasibility study when it’s considering launching a new business, adding a new product line, or acquiring a rival.

- A feasibility study assesses the potential for success of the proposed plan or project by defining its expected costs and projected benefits in detail.

- It’s a good idea to have a contingency plan on hand in case the original project is found to be infeasible.

Lara Antal / Investopedia

A feasibility study is an assessment of the practicality of a proposed plan or project. A feasibility study analyzes the viability of a project to determine whether the project or venture is likely to succeed. The study is also designed to identify potential issues and problems that could arise while pursuing the project.

As part of the feasibility study, project managers must determine whether they have enough of the right people, financial resources, and technology. The study must also determine the return on investment, whether this is measured as a financial gain or a benefit to society, the latter in the case of a nonprofit project.

The feasibility study might include a cash flow analysis, measuring the level of cash generated from revenue vs. the project’s operating costs . A risk assessment must also be completed to determine whether the return is enough to offset the risk of undergoing the venture.

When doing a feasibility study, it’s always good to have a contingency plan that is ready to test as a viable alternative if the first plan fails.

Benefits of a Feasibility Study

There are several benefits to feasibility studies, including helping project managers discern the pros and cons of undertaking a project before investing a significant amount of time and capital into it.

Feasibility studies can also provide a company’s management team with crucial information that could prevent them from entering into a risky business venture.

Such studies help companies determine how they will grow. They will know more about how they will operate, what the potential obstacles are, who the competition is, and what the market is.

Feasibility studies also help convince investors and bankers that investing in a particular project or business is a wise choice.

The exact format of a feasibility study will depend on the type of organization that requires it. However, the same factors will be involved even if their weighting varies.

Preliminary Analysis

Although each project can have unique goals and needs, there are some best practices for conducting any feasibility study:

- Conduct a preliminary analysis, which involves getting feedback about the new concept from the appropriate stakeholders.

- Analyze and ask questions about the data obtained in the early phase of the study to make sure that it’s solid.

- Conduct a market survey or market research to identify the market demand and opportunity for pursuing the project or business.

- Write an organizational, operational, or business plan, including identifying the amount of labor needed, at what cost, and for how long.

- Prepare a projected income statement, which includes revenue, operating costs, and profit .

- Prepare an opening day balance sheet .

- Identify obstacles and any potential vulnerabilities, as well as how to deal with them.

- Make an initial “go” or “no-go” decision about moving ahead with the plan.

Suggested Components

Once the initial due diligence has been completed, the real work begins. Components that are typically found in a feasibility study include the following:

- Executive summary : Formulate a narrative describing details of the project, product, service, plan, or business.

- Technological considerations : Ask what will it take. Do you have it? If not, can you get it? What will it cost?

- Existing marketplace : Examine the local and broader markets for the product, service, plan, or business.

- Marketing strategy : Describe it in detail.

- Required staffing : What are the human capital needs for this project? Draw up an organizational chart.

- Schedule and timeline : Include significant interim markers for the project’s completion date.

- Project financials

- Findings and recommendations : Break down into subsets of technology, marketing, organization, and financials.

Examples of a Feasibility Study

Below are two examples of a feasibility study. The first involves expansion plans for a university. The second is a real-world example conducted by the Washington State Department of Transportation with private contributions from Microsoft Inc.

A University Science Building

Officials at a university were concerned that the science building—built in the 1970s—was outdated. Considering the technological and scientific advances of the last 20 years, they wanted to explore the cost and benefits of upgrading and expanding the building. A feasibility study was conducted.

In the preliminary analysis, school officials explored several options, weighing the benefits and costs of expanding and updating the science building. Some school officials had concerns about the project, including the cost and possible community opposition. The new science building would be much larger, and the community board had earlier rejected similar proposals. The feasibility study would need to address these concerns and any potential legal or zoning issues.

The feasibility study also explored the technological needs of the new science facility, the benefits to the students, and the long-term viability of the college. A modernized science facility would expand the school’s scientific research capabilities, improve its curriculum, and attract new students.

Financial projections showed the cost and scope of the project and how the school planned to raise the needed funds, which included issuing a bond to investors and tapping into the school’s endowment . The projections also showed how the expanded facility would allow more students to be enrolled in the science programs, increasing revenue from tuition and fees.

The feasibility study demonstrated that the project was viable, paving the way to enacting the modernization and expansion plans of the science building.

Without conducting a feasibility study, the school administrators would never have known whether its expansion plans were viable.

A High-Speed Rail Project

The Washington State Department of Transportation decided to conduct a feasibility study on a proposal to construct a high-speed rail that would connect Vancouver, British Columbia, Seattle, Washington, and Portland, Oregon. The goal was to create an environmentally responsible transportation system to enhance the competitiveness and future prosperity of the Pacific Northwest.

The preliminary analysis outlined a governance framework for future decision making. The study involved researching the most effective governance framework by interviewing experts and stakeholders, reviewing governance structures, and learning from existing high-speed rail projects in North America. As a result, governing and coordinating entities were developed to oversee and follow the project if it was approved by the state legislature.

A strategic engagement plan involved an equitable approach with the public, elected officials, federal agencies, business leaders, advocacy groups, and Indigenous communities. The engagement plan was designed to be flexible, considering the size and scope of the project and how many cities and towns would be involved. A team of the executive committee members was formed and met to discuss strategies, as well as lessons learned from previous projects, and met with experts to create an outreach framework.

The financial component of the feasibility study outlined the strategy for securing the project’s funding, which explored obtaining funds from federal, state, and private investments. The project’s cost was estimated to be $24 billion to $42 billion. The revenue generated from the high-speed rail system was estimated to be $160 million to $250 million.

The report bifurcated the money sources between funding and financing. Funding referred to grants, appropriations from the local or state government, and revenue. Financing referred to bonds issued by the government, loans from financial institutions, and equity investments, which are essentially loans against future revenue that need to be paid back with interest.

The sources for the capital needed were to vary as the project moved forward. In the early stages, most of the funding would come from the government, and as the project developed, funding would come from private contributions and financing measures. Private contributors included Microsoft Inc., which donated more than $570,000 to the project.

The benefits outlined in the feasibility report show that the region would experience enhanced interconnectivity, allowing for better management of the population and increasing regional economic growth by $355 billion. The new transportation system would provide people with access to better jobs and more affordable housing. The high-speed rail system would also relieve congested areas from automobile traffic.

The timeline for the study began in 2016, when an agreement was reached with British Columbia to work together on a new technology corridor that included high-speed rail transportation. The feasibility report was submitted to the Washington State Legislature in December 2020.

What Is the Main Objective of a Feasibility Study?

A feasibility study is designed to help decision makers determine whether or not a proposed project or investment is likely to be successful. It identifies both the known costs and the expected benefits.

In business, “successful” means that the financial return exceeds the cost. In a nonprofit, success may be measured in other ways. A project’s benefit to the community it serves may be worth the cost.

What Are the Steps in a Feasibility Study?

A feasibility study starts with a preliminary analysis. Stakeholders are interviewed, market research is conducted, and a business plan is prepared. All of this information is analyzed to make an initial “go” or “no-go” decision.

If it’s a go, the real study can begin. This includes listing the technological considerations, studying the marketplace, describing the marketing strategy, and outlining the necessary human capital, project schedule, and financing requirements.

Who Conducts a Feasibility Study?

A feasibility study may be conducted by a team of the organization’s senior managers. If they lack the expertise or time to do the work internally, it may be outsourced to a consultant.

What Are the 4 Types of Feasibility?

The study considers the feasibility of four aspects of a project:

Technical : A list of the hardware and software needed, and the skilled labor required to make them work

Financial : An estimate of the cost of the overall project and its expected return

Market : An analysis of the market for the product or service, the industry, competition, consumer demand, sales forecasts, and growth projections

Organizational : An outline of the business structure and the management team that will be needed

Feasibility studies help project managers determine the viability of a project or business venture by identifying the factors that can lead to its success. The study also shows the potential return on investment and any risks to the success of the venture.

A feasibility study contains a detailed analysis of what’s needed to complete the proposed project. The report may include a description of the new product or venture, a market analysis, the technology and labor needed, and the sources of financing and capital. The report will also include financial projections, the likelihood of success, and ultimately, a “go” or “no-go” decision.

Washington State Department of Transportation. “ Ultra-High-Speed Rail Study .”

Washington State Department of Transportation. “ Cascadia Ultra High Speed Ground Transportation: Framework for the Future .”

Washington State Department of Transportation. “ Ultra-High-Speed Rail Study: Outcomes .”

Washington State Department of Transportation. “ Ultra-High-Speed Ground Transportation Business Case Analysis ,” Page ii (Page 3 of PDF).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/project-management.asp-Final-0c4cd7f77aad40228e7311783c27f728.png)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

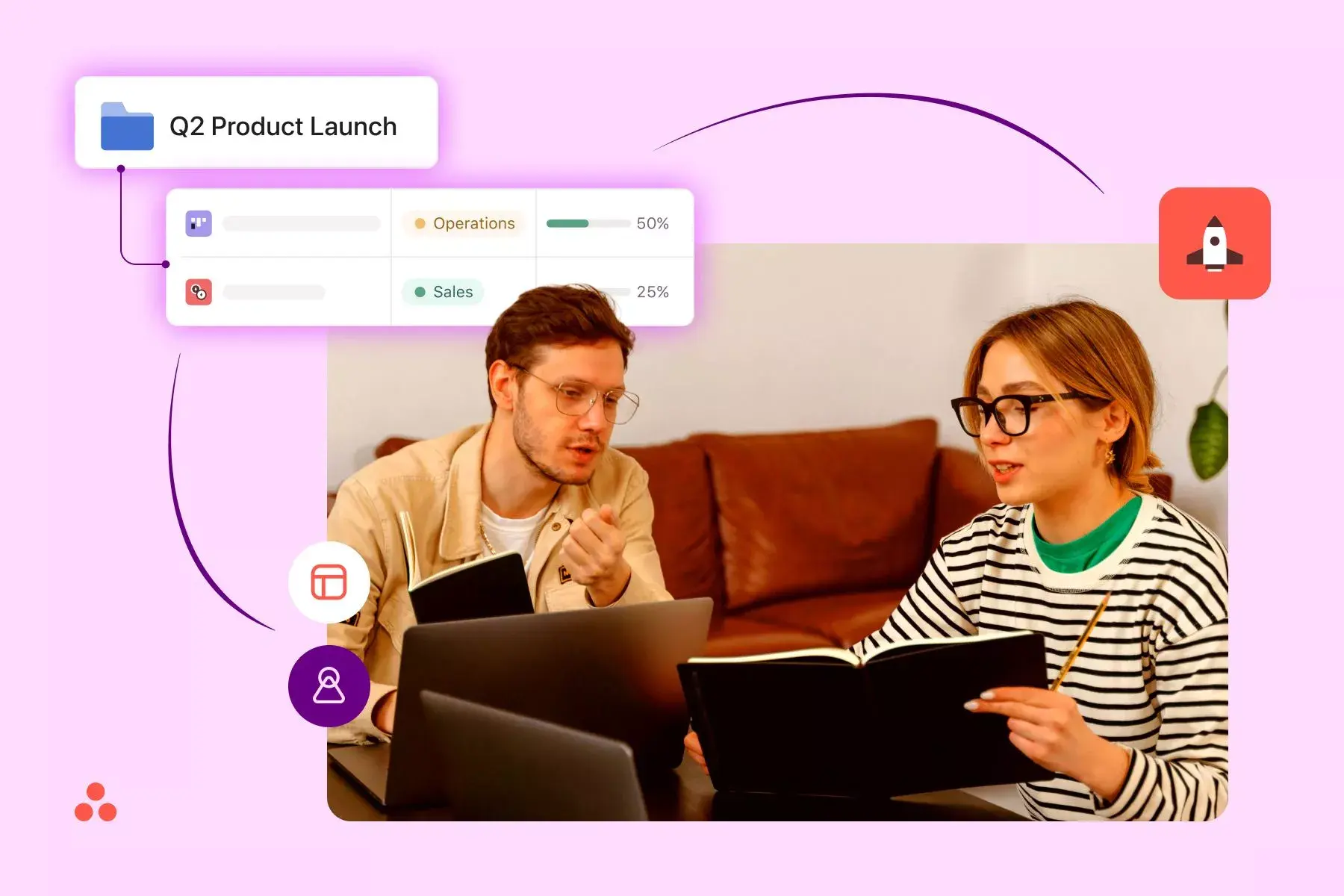

What is a Feasibility Study and How to Conduct It? (+ Examples)

Appinio Research · 26.09.2023 · 28min read

Are you ready to turn your project or business idea into a concrete reality but unsure about its feasibility? Whether you're a seasoned entrepreneur or a first-time project manager, understanding the intricate process of conducting a feasibility study is vital for making informed decisions and maximizing your chances of success.

This guide will equip you with the knowledge and tools to navigate the complexities of market, technical, financial, and operational feasibility studies. By the end, you'll have a clear roadmap to confidently assess, plan, and execute your project.

What is a Feasibility Study?

A feasibility study is a systematic and comprehensive analysis of a proposed project or business idea to assess its viability and potential for success. It involves evaluating various aspects such as market demand, technical feasibility, financial viability, and operational capabilities. The primary goal of a feasibility study is to provide you with valuable insights and data to make informed decisions about whether to proceed with the project.

Why is a Feasibility Study Important?

Conducting a feasibility study is a critical step in the planning process for any project or business. It helps you:

- Minimize Risks: By identifying potential challenges and obstacles early on, you can develop strategies to mitigate risks.

- Optimize Resource Allocation: A feasibility study helps you allocate your resources more efficiently, including time and money.

- Enhance Decision-Making: Armed with data and insights, you can make well-informed decisions about pursuing the project or exploring alternative options.

- Attract Stakeholders: Potential investors, lenders, and partners often require a feasibility study to assess the project's credibility and potential return on investment.

Now that you understand the importance of feasibility studies, let's explore the various types and dive deeper into each aspect.

Types of Feasibility Studies

Feasibility studies come in various forms, each designed to assess different aspects of a project's viability. Let's delve into the four primary types of feasibility studies in more detail:

1. Market Feasibility Study

Market feasibility studies are conducted to determine whether there is a demand for a product or service in a specific market or industry. This type of study focuses on understanding customer needs, market trends, and the competitive landscape. Here are the key elements of a market feasibility study:

- Market Research and Analysis: Comprehensive research is conducted to gather market size, growth potential , and customer behavior data. This includes both primary research (surveys, interviews) and secondary research (existing reports, data).

- Target Audience Identification: Identifying the ideal customer base by segmenting the market based on demographics, psychographics, and behavior. Understanding your target audience is crucial for tailoring your product or service.

- Competitive Analysis : Assessing the competition within the market, including identifying direct and indirect competitors, their strengths, weaknesses, and market share .

- Demand and Supply Assessment: Analyzing the balance between the demand for the product or service and its supply. This helps determine whether there is room for a new entrant in the market.

2. Technical Feasibility Study

Technical feasibility studies evaluate whether the project can be developed and implemented from a technical standpoint. This assessment focuses on the project's design, technical requirements, and resource availability. Here's what it entails:

- Project Design and Technical Requirements: Defining the technical specifications of the project, including hardware, software, and any specialized equipment. This phase outlines the technical aspects required for project execution.

- Technology Assessment: Evaluating the chosen technology's suitability for the project and assessing its scalability and compatibility with existing systems.

- Resource Evaluation: Assessing the availability of essential resources such as personnel, materials, and suppliers to ensure the project's technical requirements can be met.

- Risk Analysis: Identifying potential technical risks, challenges, and obstacles that may arise during project development. Developing risk mitigation strategies is a critical part of technical feasibility.

3. Financial Feasibility Study

Financial feasibility studies aim to determine whether the project is financially viable and sustainable in the long run. This type of study involves estimating costs, projecting revenue, and conducting financial analyses. Key components include:

- Cost Estimation: Calculating both initial and ongoing costs associated with the project, including capital expenditures, operational expenses, and contingency funds.

- Revenue Projections: Forecasting the income the project is expected to generate, considering sales, pricing strategies, market demand, and potential revenue streams.

- Investment Analysis: Evaluating the return on investment (ROI), payback period, and potential risks associated with financing the project.

- Financial Viability Assessment: Analyzing the project's profitability, cash flow, and financial stability to ensure it can meet its financial obligations and sustain operations.

4. Operational Feasibility Study

Operational feasibility studies assess whether the project can be effectively implemented within the organization's existing operational framework. This study considers processes, resource planning, scalability, and operational risks. Key elements include:

- Process and Workflow Assessment: Analyzing how the project integrates with current processes and workflows, identifying potential bottlenecks, and optimizing operations.

- Resource Planning: Determining the human, physical, and technological resources required for successful project execution and identifying resource gaps.

- Scalability Evaluation: Assessing the project's ability to adapt and expand to meet changing demands and growth opportunities, including capacity planning and growth strategies.

- Operational Risks Analysis: Identifying potential operational challenges and developing strategies to mitigate them, ensuring smooth project implementation.

Each type of feasibility study serves a specific purpose in evaluating different facets of your project, collectively providing a comprehensive assessment of its viability and potential for success.

How to Prepare for a Feasibility Study?

Before you dive into the nitty-gritty details of conducting a feasibility study, it's essential to prepare thoroughly. Proper preparation will set the stage for a successful and insightful study. In this section, we'll explore the main steps involved in preparing for a feasibility study.

1. Identify the Project or Idea

Identifying and defining your project or business idea is the foundational step in the feasibility study process. This initial phase is critical because it helps you clarify your objectives and set the direction for the study.

- Problem Identification: Start by pinpointing the problem or need your project addresses. What pain point does it solve for your target audience?

- Project Definition: Clearly define your project or business idea. What are its core components, features, or offerings?

- Goals and Objectives: Establish specific goals and objectives for your project. What do you aim to achieve in the short and long term?

- Alignment with Vision: Ensure your project aligns with your overall vision and mission. How does it fit into your larger strategic plan?

Remember, the more precisely you can articulate your project or idea at this stage, the easier it will be to conduct a focused and effective feasibility study.

2. Assemble a Feasibility Study Team

Once you've defined your project, the next step is to assemble a competent and diverse feasibility study team. Your team's expertise will play a crucial role in conducting a thorough assessment of your project's viability.

- Identify Key Roles: Determine the essential roles required for your feasibility study. These typically include experts in areas such as market research, finance, technology, and operations.

- Select Team Members: Choose team members with the relevant skills and experience to fulfill these roles effectively. Look for individuals who have successfully conducted feasibility studies in the past.

- Collaboration and Communication: Foster a collaborative environment within your team. Effective communication is essential to ensure everyone is aligned on objectives and timelines.

- Project Manager: Designate a project manager responsible for coordinating the study, tracking progress, and meeting deadlines.

- External Consultants: In some cases, you may need to engage external consultants or specialists with niche expertise to provide valuable insights.

Having the right people on your team will help you collect accurate data, analyze findings comprehensively, and make well-informed decisions based on the study's outcomes.

3. Set Clear Objectives and Scope

Before you begin the feasibility study, it's crucial to establish clear and well-defined objectives. These objectives will guide your research and analysis efforts throughout the study.

Steps to Set Clear Objectives and Scope:

- Objective Clarity: Define the specific goals you aim to achieve through the feasibility study. What questions do you want to answer, and what decisions will the study inform?

- Scope Definition: Determine the boundaries of your study. What aspects of the project will be included, and what will be excluded? Clarify any limitations.

- Resource Allocation: Assess the resources needed for the study, including time, budget, and personnel. Ensure that you allocate resources appropriately based on the scope and objectives.

- Timeline: Establish a realistic timeline for the feasibility study. Identify key milestones and deadlines for completing different phases of the study.

Clear objectives and a well-defined scope will help you stay focused and avoid scope creep during the study. They also provide a basis for measuring the study's success against its intended outcomes.

4. Gather Initial Information

Before you delve into extensive research and data collection, start by gathering any existing information and documents related to your project or industry. This initial step will help you understand the current landscape and identify gaps in your knowledge.

- Document Review: Review any existing project documentation, market research reports, business plans, or relevant industry studies.

- Competitor Analysis: Gather information about your competitors, including their products, pricing, market share, and strategies.

- Regulatory and Compliance Documents: If applicable, collect information on industry regulations, permits, licenses, and compliance requirements.

- Market Trends: Stay informed about current market trends, consumer preferences, and emerging technologies that may impact your project.

- Stakeholder Interviews: Consider conducting initial interviews with key stakeholders, including potential customers, suppliers, and industry experts, to gather insights and feedback.

By starting with a strong foundation of existing knowledge, you'll be better prepared to identify gaps that require further investigation during the feasibility study. This proactive approach ensures that your study is comprehensive and well-informed from the outset.

How to Conduct a Market Feasibility Study?

The market feasibility study is a crucial component of your overall feasibility analysis. It focuses on assessing the potential demand for your product or service, understanding your target audience, analyzing your competition, and evaluating supply and demand dynamics within your chosen market.

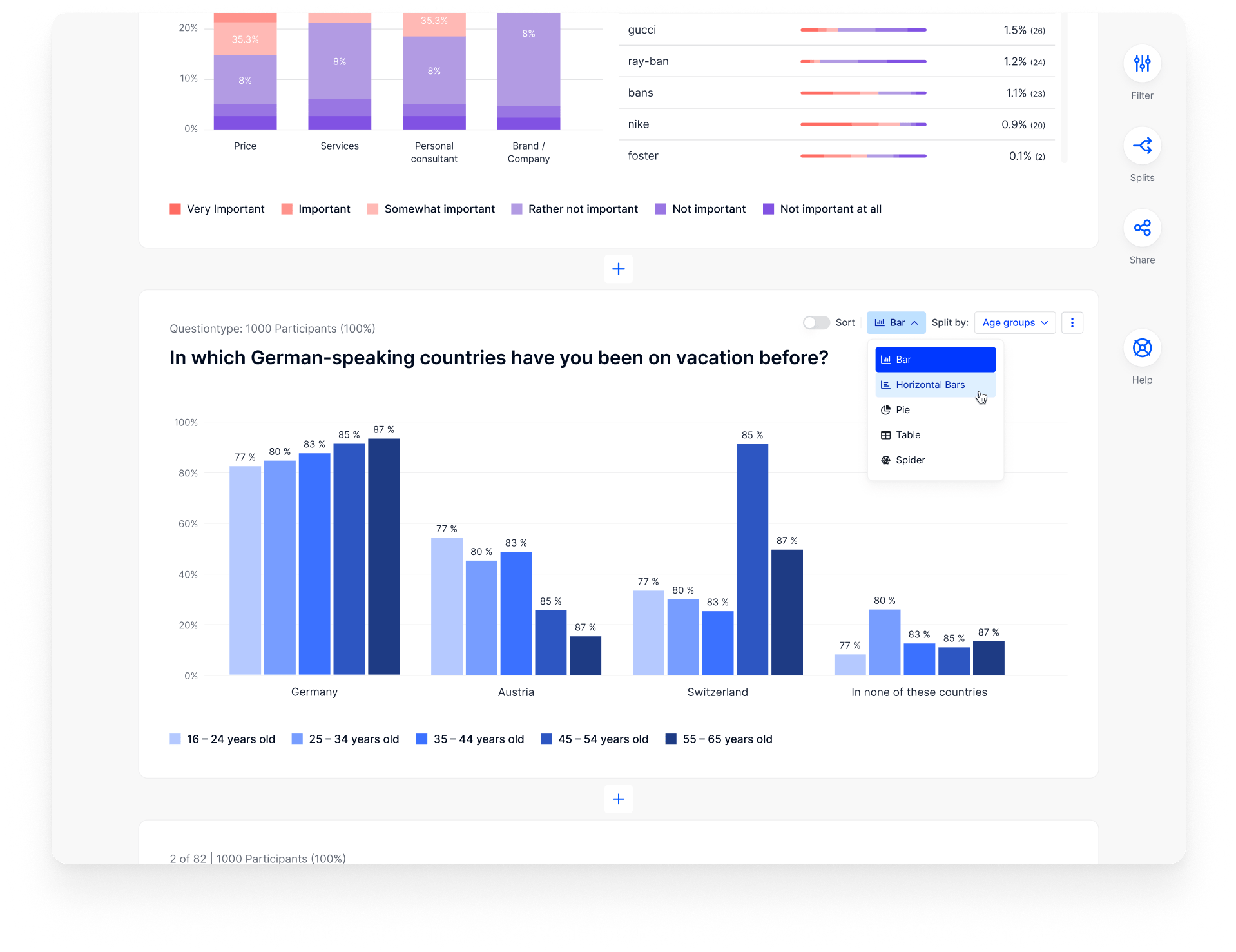

Market Research and Analysis

Market research is the foundation of your market feasibility study. It involves gathering and analyzing data to gain insights into market trends, customer preferences, and the overall business landscape.

- Data Collection: Utilize various methods such as surveys, interviews, questionnaires, and secondary research to collect data about the market. This data may include market size, growth rates, and historical trends.

- Market Segmentation: Divide the market into segments based on factors such as demographics, psychographics , geography, and behavior. This segmentation helps you identify specific target markets .

- Customer Needs Analysis: Understand the needs, preferences, and pain points of potential customers . Determine how your product or service can address these needs effectively.

- Market Trends: Stay updated on current market trends, emerging technologies, and industry innovations that could impact your project.

- SWOT Analysis: Conduct a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis to identify internal and external factors that may affect your market entry strategy.

In today's dynamic market landscape, gathering precise data for your market feasibility study is paramount. Appinio offers a versatile platform that enables you to swiftly collect valuable market insights from a diverse audience.

With Appinio, you can employ surveys, questionnaires, and in-depth analyses to refine your understanding of market trends, customer preferences, and competition.

Enhance your market research and gain a competitive edge by booking a demo with us today!

Book a Demo

Target Audience Identification

Knowing your target audience is essential for tailoring your product or service to meet their specific needs and preferences.

- Demographic Analysis: Define the age, gender, income level, education, and other demographic characteristics of your ideal customers.

- Psychographic Profiling: Understand the psychographics of your target audience, including their lifestyle, values, interests, and buying behavior.

- Market Segmentation: Refine your target audience by segmenting it further based on shared characteristics and behaviors.

- Needs and Pain Points: Identify your target audience's unique needs, challenges, and pain points that your product or service can address.

- Competitor's Customers: Analyze the customer base of your competitors to identify potential opportunities for capturing market share.

Competitive Analysis

Competitive analysis helps you understand the strengths and weaknesses of your competitors, positioning your project strategically within the market.

- Competitor Identification: Identify direct and indirect competitors within your industry or market niche.

- Competitive Advantage: Determine the unique selling points (USPs) that set your project apart from competitors. What value can you offer that others cannot?

- SWOT Analysis for Competitors: Conduct a SWOT analysis for each competitor to assess their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

- Market Share Assessment: Analyze each competitor's market share and market penetration strategies.

- Pricing Strategies: Investigate the pricing strategies employed by competitors and consider how your pricing strategy will compare.

Leveraging the power of data collection and analysis is essential in gaining a competitive edge. With Appinio , you can efficiently gather critical insights about your competitors, their strengths, and weaknesses. Seamlessly integrate these findings into your market feasibility study, empowering your project with a strategic advantage.

Demand and Supply Assessment

Understanding supply and demand dynamics is crucial for gauging market sustainability and potential challenges.

- Market Demand Analysis: Estimate the current and future demand for your product or service. Consider factors like seasonality and trends.

- Supply Evaluation: Assess the availability of resources, suppliers, and distribution channels required to meet the expected demand.

- Market Saturation: Determine whether the market is saturated with similar offerings and how this might affect your project.

- Demand Forecasting: Use historical data and market trends to make informed projections about future demand.

- Scalability: Consider the scalability of your project to meet increased demand or potential fluctuations.

A comprehensive market feasibility study will give you valuable insights into your potential customer base, market dynamics, and competitive landscape. This information will be pivotal in shaping your project's direction and strategy.

How to Conduct a Technical Feasibility Study?

The technical feasibility study assesses the practicality of implementing your project from a technical standpoint. It involves evaluating the project's design, technical requirements, technological feasibility, resource availability, and risk analysis. Let's delve into each aspect in more detail.

1. Project Design and Technical Requirements

The project design and technical requirements are the foundation of your technical feasibility study. This phase involves defining the technical specifications and infrastructure needed to execute your project successfully.

- Technical Specifications: Clearly define the technical specifications of your project, including hardware, software, and any specialized equipment.

- Infrastructure Planning: Determine the physical infrastructure requirements, such as facilities, utilities, and transportation logistics.

- Development Workflow: Outline the workflow and processes required to design, develop, and implement the project.

- Prototyping: Consider creating prototypes or proof-of-concept models to test and validate the technical aspects of your project.

2. Technology Assessment

A critical aspect of the technical feasibility study is assessing the technology required for your project and ensuring it aligns with your goals.

- Technology Suitability: Evaluate the suitability of the chosen technology for your project. Is it the right fit, or are there better alternatives?

- Scalability and Compatibility: Assess whether the chosen technology can scale as your project grows and whether it is compatible with existing systems or software.

- Security Measures: Consider cybersecurity and data protection measures to safeguard sensitive information.

- Technical Expertise: Ensure your team or external partners possess the technical expertise to implement and maintain the technology.

3. Resource Evaluation

Resource evaluation involves assessing the availability of the essential resources required to execute your project successfully. These resources include personnel, materials, and suppliers.

- Human Resources: Evaluate whether you have access to skilled personnel or if additional hiring or training is necessary.

- Material Resources: Identify the materials and supplies needed for your project and assess their availability and costs.

- Supplier Relationships: Establish relationships with reliable suppliers and consistently assess their ability to meet your resource requirements.

4. Risk Analysis

Risk analysis is a critical component of the technical feasibility study, as it helps you anticipate and mitigate potential technical challenges and setbacks.

- Identify Risks: Identify potential technical risks, such as hardware or software failures, technical skill gaps, or unforeseen technical obstacles.

- Risk Mitigation Strategies: Develop strategies to mitigate identified risks, including contingency plans and resource allocation for risk management.

- Cost Estimation for Risk Mitigation: Assess the potential costs associated with managing technical risks and incorporate them into your project budget.

By conducting a thorough technical feasibility study, you can ensure that your project is technically viable and well-prepared to overcome technical challenges. This assessment will also guide decision-making regarding technology choices, resource allocation, and risk management strategies.

How to Conduct a Financial Feasibility Study?

The financial feasibility study is a critical aspect of your overall feasibility analysis. It focuses on assessing the financial viability of your project by estimating costs, projecting revenue, conducting investment analysis, and evaluating the overall financial health of your project. Let's delve into each aspect in more detail.

1. Cost Estimation

Cost estimation is the process of calculating the expenses associated with planning, developing, and implementing your project. This involves identifying both initial and ongoing costs.

- Initial Costs: Calculate the upfront expenses required to initiate the project, including capital expenditures, equipment purchases, and any development costs.

- Operational Costs: Estimate the ongoing operating expenses, such as salaries, utilities, rent, marketing, and maintenance.

- Contingency Funds: Allocate funds for unexpected expenses or contingencies to account for unforeseen challenges.

- Depreciation: Consider the depreciation of assets over time, as it impacts your financial statements.

2. Revenue Projections

Revenue projections involve forecasting the income your project is expected to generate over a specific period. Accurate revenue projections are crucial for assessing the project's financial viability.

- Sales Forecasts: Estimate your product or service sales based on market demand, pricing strategies, and potential growth.

- Pricing Strategy: Determine your pricing strategy, considering factors like competition, market conditions, and customer willingness to pay.

- Market Penetration: Analyze how quickly you can capture market share and increase sales over time.

- Seasonal Variations: Account for any seasonal fluctuations in revenue that may impact your cash flow.

3. Investment Analysis

Investment analysis involves evaluating the potential return on investment (ROI) and assessing the attractiveness of your project to potential investors or stakeholders.

- Return on Investment (ROI): Calculate the expected ROI by comparing the project's net gains against the initial investment.

- Payback Period: Determine how long it will take for the project to generate sufficient revenue to cover its initial costs.

- Risk Assessment: Consider the level of risk associated with the project and whether it aligns with investors' risk tolerance.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform sensitivity analysis to understand how changes in key variables, such as sales or costs, affect the investment's profitability.

4. Financial Viability Assessment

A financial viability assessment evaluates the project's ability to sustain itself financially in the long term. It considers factors such as profitability, cash flow, and financial stability.

- Profitability Analysis: Assess whether the project is expected to generate profits over its lifespan.

- Cash Flow Management: Analyze the project's cash flow to ensure it can cover operating expenses, debt payments, and other financial obligations.

- Break-Even Analysis: Determine the point at which the project's revenue covers all costs, resulting in neither profit nor loss.

- Financial Ratios: Calculate key financial ratios, such as debt-to-equity ratio and return on equity, to evaluate the project's financial health.

By conducting a comprehensive financial feasibility study, you can gain a clear understanding of the project's financial prospects and make informed decisions regarding its viability and potential for success.

How to Conduct an Operational Feasibility Study?

The operational feasibility study assesses whether your project can be implemented effectively within your organization's operational framework. It involves evaluating processes, resource planning, scalability, and analyzing potential operational risks.

1. Process and Workflow Assessment

The process and workflow assessment examines how the project integrates with existing processes and workflows within your organization.

- Process Mapping: Map out current processes and workflows to identify areas of integration and potential bottlenecks.

- Workflow Efficiency: Assess the efficiency and effectiveness of existing workflows and identify opportunities for improvement.

- Change Management: Consider the project's impact on employees and plan for change management strategies to ensure a smooth transition.

2. Resource Planning

Resource planning involves determining the human, physical, and technological resources needed to execute the project successfully.

- Human Resources: Assess the availability of skilled personnel and consider whether additional hiring or training is necessary.

- Physical Resources: Identify the physical infrastructure, equipment, and materials required for the project.

- Technology and Tools: Ensure that the necessary technology and tools are available and up to date to support project implementation.

3. Scalability Evaluation

Scalability evaluation assesses whether the project can adapt and expand to meet changing demands and growth opportunities.

- Scalability Factors: Identify factors impacting scalability, such as market growth, customer demand, and technological advancements.

- Capacity Planning: Plan for the scalability of resources, including personnel, infrastructure, and technology.

- Growth Strategies: Develop strategies for scaling the project, such as geographic expansion, product diversification, or increasing production capacity.

4. Operational Risk Analysis

Operational risk analysis involves identifying potential operational challenges and developing mitigation strategies.

- Risk Identification: Identify operational risks that could disrupt project implementation or ongoing operations.

- Risk Mitigation: Develop risk mitigation plans and contingency strategies to address potential challenges.

- Testing and Simulation: Consider conducting simulations or testing to evaluate how the project performs under various operational scenarios.

- Monitoring and Adaptation: Implement monitoring and feedback mechanisms to detect and address operational issues as they arise.

Conducting a thorough operational feasibility study ensures that your project aligns with your organization's capabilities, processes, and resources. This assessment will help you plan for a successful implementation and minimize operational disruptions.

How to Write a Feasibility Study?

The feasibility study report is the culmination of your feasibility analysis. It provides a structured and comprehensive document outlining your study's findings, conclusions, and recommendations. Let's explore the key components of the feasibility study report.

1. Structure and Components

The structure of your feasibility study report should be well-organized and easy to navigate. It typically includes the following components:

- Executive Summary: A concise summary of the study's key findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

- Introduction: An overview of the project, the objectives of the study, and a brief outline of what the report covers.

- Methodology: A description of the research methods , data sources, and analytical techniques used in the study.

- Market Feasibility Study: Detailed information on market research, target audience, competitive analysis, and demand-supply assessment.

- Technical Feasibility Study: Insights into project design, technical requirements, technology assessment, resource evaluation, and risk analysis.

- Financial Feasibility Study: Comprehensive information on cost estimation, revenue projections, investment analysis, and financial viability assessment.

- Operational Feasibility Study: Details on process and workflow assessment, resource planning, scalability evaluation, and operational risks analysis.

- Conclusion: A summary of key findings and conclusions drawn from the study.

Recommendations: Clear and actionable recommendations based on the study's findings.

2. Write the Feasibility Study Report

When writing the feasibility study report, it's essential to maintain clarity, conciseness, and objectivity. Use clear language and provide sufficient detail to support your conclusions and recommendations.

- Be Objective: Present findings and conclusions impartially, based on data and analysis.

- Use Visuals: Incorporate charts, graphs, and tables to illustrate key points and make the report more accessible.

- Cite Sources: Properly cite all data sources and references used in the study.

- Include Appendices: Attach any supplementary information, data, or documents in appendices for reference.

3. Present Findings and Recommendations

When presenting your findings and recommendations, consider your target audience. Tailor your presentation to the needs and interests of stakeholders, whether they are investors, executives, or decision-makers.

- Highlight Key Takeaways: Summarize the most critical findings and recommendations upfront.

- Use Visual Aids: Create a visually engaging presentation with slides, charts, and infographics.

- Address Questions: Be prepared to answer questions and provide additional context during the presentation.

- Provide Supporting Data: Back up your findings and recommendations with data from the feasibility study.

4. Review and Validation

Before finalizing the feasibility study report, conducting a thorough review and validation process is crucial. This ensures the accuracy and credibility of the report.

- Peer Review: Have colleagues or subject matter experts review the report for accuracy and completeness.

- Data Validation: Double-check data sources and calculations to ensure they are accurate.

- Cross-Functional Review: Involve team members from different disciplines to provide diverse perspectives.

- Stakeholder Input: Seek input from key stakeholders to validate findings and recommendations.

By following a structured approach to creating your feasibility study report, you can effectively communicate the results of your analysis, support informed decision-making, and increase the likelihood of project success.

Feasibility Study Examples

Let's dive into some real-world examples to truly grasp the concept and application of feasibility studies. These examples will illustrate how various types of projects and businesses undergo the feasibility assessment process to ensure their viability and success.

Example 1: Local Restaurant

Imagine you're passionate about opening a new restaurant in a bustling urban area. Before investing significant capital, you'd want to conduct a thorough feasibility study. Here's how it might unfold:

- Market Feasibility: You research the local dining scene, identify target demographics, and assess the demand for your cuisine. Market surveys reveal potential competitors, dining preferences, and pricing expectations.

- Technical Feasibility: You design the restaurant layout, plan the kitchen setup, and assess the technical requirements for equipment and facilities. You consider factors like kitchen efficiency, safety regulations, and adherence to health codes.

- Financial Feasibility: You estimate the initial costs for leasing or purchasing a space, kitchen equipment, staff hiring, and marketing. Revenue projections are based on expected foot traffic, menu pricing, and seasonal variations.

- Operational Feasibility: You create kitchen and service operations workflow diagrams, considering staff roles and responsibilities. Resource planning includes hiring chefs, waitstaff, and kitchen personnel. Scalability is evaluated for potential expansion or franchising.

- Risk Analysis: Potential operational risks are identified, such as food safety concerns, labor shortages, or location-specific challenges. Risk mitigation strategies involve staff training, quality control measures, and contingency plans for unexpected events.

Example 2: Software Development Project

Now, let's explore the feasibility study process for a software development project, such as building a mobile app:

- Market Feasibility: You analyze the mobile app market, identify your target audience, and assess the demand for a solution in a specific niche. You gather user feedback and conduct competitor analysis to understand the competitive landscape.

- Technical Feasibility: You define the technical requirements for the app, considering platforms (iOS, Android), development tools, and potential integrations with third-party services. You evaluate the feasibility of implementing specific features.

- Financial Feasibility: You estimate the development costs, including hiring developers, designers, and ongoing maintenance expenses. Revenue projections are based on app pricing, potential in-app purchases, and advertising revenue.

- Operational Feasibility: You map out the development workflow, detailing the phases from concept to deployment. Resource planning includes hiring developers with the necessary skills, setting up development environments, and establishing a testing framework.

- Risk Analysis: Potential risks like scope creep, technical challenges, or market saturation are assessed. Mitigation strategies involve setting clear project milestones, conducting thorough testing, and having contingency plans for technical glitches.

These examples demonstrate the versatility of feasibility studies across diverse projects. Whatever type of venture or endeavor you want to embark on, a well-structured feasibility study guides you toward informed decisions and increased project success.

In conclusion, conducting a feasibility study is a crucial step in your project's journey. It helps you assess the viability and potential risks, providing a solid foundation for informed decision-making. Remember, a well-executed feasibility study not only enables you to identify challenges but also uncovers opportunities that can lead to your project's success.

By thoroughly examining market trends, technical requirements, financial aspects, and operational considerations, you are better prepared to embark on your project confidently. With this guide, you've gained the knowledge and tools needed to navigate the intricate terrain of feasibility studies.

How to Conduct a Feasibility Study in Minutes?

Speed and precision are paramount for feasibility studies, and Appinio delivers just that. As a real-time market research platform, Appinio empowers you to seamlessly conduct your market research in a matter of minutes, putting actionable insights at your fingertips.

Here's why Appinio stands out as the go-to tool for feasibility studies:

- Rapid Insights: Appinio's intuitive platform ensures that anyone, regardless of their research background, can effortlessly navigate and conduct research, saving valuable time and resources.

- Lightning-Fast Responses: With an average field time of under 23 minutes for 1,000 respondents, Appinio ensures that you get the answers you need when you need them, making it ideal for time-sensitive feasibility studies.

- Global Reach: Appinio's extensive reach spans over 90 countries, allowing you to define the perfect target group from a pool of 1,200+ characteristics and gather insights from diverse markets.

Get free access to the platform!

Join the loop 💌

Be the first to hear about new updates, product news, and data insights. We'll send it all straight to your inbox.

Get the latest market research news straight to your inbox! 💌

Wait, there's more

18.06.2024 | 6min read

Future Flavors: How Burger King nailed Concept Testing with Appinio's Predictive Insights

18.06.2024 | 32min read

What is a Pulse Survey? Definition, Types, Questions

30.05.2024 | 29min read

Pareto Analysis: Definition, Pareto Chart, Examples

- Open access

- Published: 31 October 2020

Guidance for conducting feasibility and pilot studies for implementation trials

- Nicole Pearson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2677-2327 1 , 2 ,

- Patti-Jean Naylor 3 ,

- Maureen C. Ashe 5 ,

- Maria Fernandez 4 ,

- Sze Lin Yoong 1 , 2 &

- Luke Wolfenden 1 , 2

Pilot and Feasibility Studies volume 6 , Article number: 167 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

87k Accesses

132 Citations

24 Altmetric

Metrics details

Implementation trials aim to test the effects of implementation strategies on the adoption, integration or uptake of an evidence-based intervention within organisations or settings. Feasibility and pilot studies can assist with building and testing effective implementation strategies by helping to address uncertainties around design and methods, assessing potential implementation strategy effects and identifying potential causal mechanisms. This paper aims to provide broad guidance for the conduct of feasibility and pilot studies for implementation trials.

We convened a group with a mutual interest in the use of feasibility and pilot trials in implementation science including implementation and behavioural science experts and public health researchers. We conducted a literature review to identify existing recommendations for feasibility and pilot studies, as well as publications describing formative processes for implementation trials. In the absence of previous explicit guidance for the conduct of feasibility or pilot implementation trials specifically, we used the effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial design typology proposed by Curran and colleagues as a framework for conceptualising the application of feasibility and pilot testing of implementation interventions. We discuss and offer guidance regarding the aims, methods, design, measures, progression criteria and reporting for implementation feasibility and pilot studies.

Conclusions

This paper provides a resource for those undertaking preliminary work to enrich and inform larger scale implementation trials.

Peer Review reports

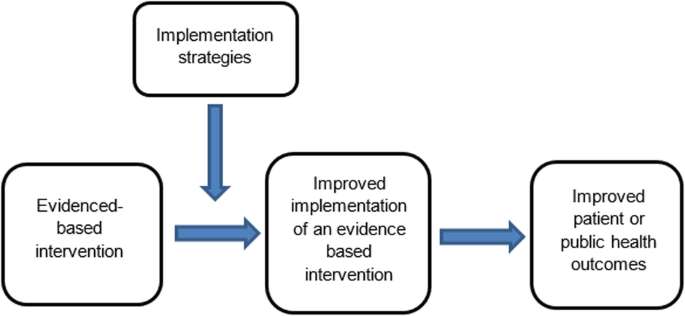

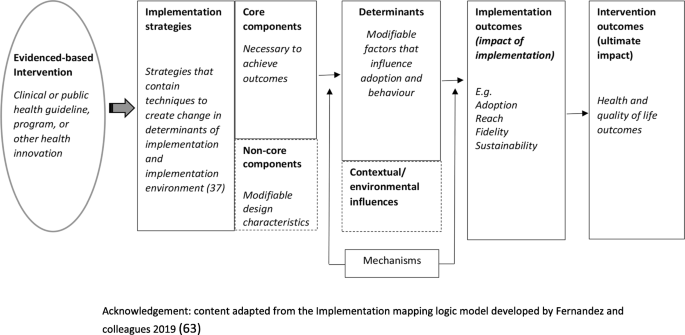

The failure to translate effective interventions for improving population and patient outcomes into policy and routine health service practice denies the community the benefits of investment in such research [ 1 ]. Improving the implementation of effective interventions has therefore been identified as a priority of health systems and research agencies internationally [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. The increased emphasis on research translation has resulted in the rapid emergence of implementation science as a scientific discipline, with the goal of integrating effective medical and public health interventions into health care systems, policies and practice [ 1 ]. Implementation research aims to do this via the generation of new knowledge, including the evaluation of the effectiveness of implementation strategies [ 7 ]. The term “implementation strategies” is used to describe the methods or techniques (e.g. training, performance feedback, communities of practice) used to enhance the adoption, implementation and/or sustainability of evidence-based interventions (Fig. 1 ) [ 8 , 9 ].

| |

Feasibility studies: an umbrella term used to describe any type of study relating to the preparation for a main study | |

: a subset of feasibility studies that specifically look at a design feature proposed for the main trial, whether in part or in full, conducted on a smaller scale [ ] |

Conceptual role of implementation strategies in improving intervention implementation and patient and public health outcomes

While there has been a rapid increase in the number of implementation trials over the past decade, the quality of trials has been criticised, and the effects of the strategies for such trials on implementation, patient or public health outcomes have been modest [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. To improve the likelihood of impact, factors that may impede intervention implementation should be considered during intervention development and across each phase of the research translation process [ 2 ]. Feasibility and pilot studies play an important role in improving the conduct and quality of a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) for both intervention and implementation trials [ 10 ]. For clinical or public health interventions, pilot and feasibility studies may serve to identify potential refinements to the intervention, address uncertainties around the feasibility of intervention trial methods, or test preliminary effects of the intervention [ 10 ]. In implementation research, feasibility and pilot studies perform the same functions as those for intervention trials, however with a focus on developing or refining implementation strategies, refining research methods for an implementation intervention trial, or undertake preliminary testing of implementation strategies [ 14 , 15 ]. Despite this, reviews of implementation studies appear to suggest that few full implementation randomised controlled trials have undertaken feasibility and pilot work in advance of a larger trial [ 16 ].

A range of publications provides guidance for the conduct of feasibility and pilot studies for conventional clinical or public health efficacy trials including Guidance for Exploratory Studies of complex public health interventions [ 17 ] and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT 2010) for Pilot and Feasibility trials [ 18 ]. However, given the differences between implementation trials and conventional clinical or public health efficacy trials, the field of implementation science has identified the need for nuanced guidance [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 19 , 20 ]. Specifically, unlike traditional feasibility and pilot studies that may include the preliminary testing of interventions on individual clinical or public health outcomes, implementation feasibility and pilot studies that explore strategies to improve intervention implementation often require assessing changes across multiple levels including individuals (e.g. service providers or clinicians) and organisational systems [ 21 ]. Due to the complexity of influencing behaviour change, the role of feasibility and pilot studies of implementation may also extend to identifying potential causal mechanisms of change and facilitate an iterative process of refining intervention strategies and optimising their impact [ 16 , 17 ]. In addition, where conventional clinical or public health efficacy trials are typically conducted under controlled conditions and directed mostly by researchers, implementation trials are more pragmatic [ 15 ]. As is the case for well conducted effectiveness trials, implementation trials often require partnerships with end-users and at times, the prioritisation of end-user needs over methods (e.g. random assignment) that seek to maximise internal validity [ 15 , 22 ]. These factors pose additional challenges for implementation researchers and underscore the need for guidance on conducting feasibility and pilot implementation studies.

Given the importance of feasibility and pilot studies in improving implementation strategies and the quality of full-scale trials of those implementation strategies, our aim is to provide practice guidance for those undertaking formative feasibility or pilot studies in the field of implementation science. Specifically, we seek to provide guidance pertaining to the three possible purposes of undertaking pilot and feasibility studies, namely (i) to inform implementation strategy development, (ii) to assess potential implementation strategy effects and (iii) to assess the feasibility of study methods.

A series of three facilitated group discussions were conducted with a group comprising of the 6 members from Canada, the U.S. and Australia (authors of the manuscript) that were mutually interested in the use of feasibility and pilot trials in implementation science. Members included international experts in implementation and behavioural science, public health and trial methods, and had considerable experience in conducting feasibility, pilot and/ or implementation trials. The group was responsible for developing the guidance document, including identification and synthesis of pertinent literature, and approving the final guidance.