Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

So why is research important to social work?

As social workers, we train to be able to see the multitude of invisible lines within the systems that hold our lives together, or divide us. We learn to recognize the disconnects, and to help our clients figure out how to reconnect the dots. We view the world through a lens of person-in-environment, that is to say, we seek to understand the context in which our clients live.

The social sciences have an inherent obligation not only to keep abreast of current relevant research, but also to be competent enough to apply new treatments and insights within their practice. Social workers are truly dedicated professionals who have to complete a minimum number of continuing education credits to continue practicing. We don’t get to pick and choose the individuals we help, which is why we have to constantly develop our cultural competencies to identify the strengths of those we are helping. So, research is important to social work because it helps us be effective!

According to the NASW, research in social work helps us:

- Assess the needs and resources of people in their environments

- Evaluate the effectiveness of social work services in meeting peoples needs

- Demonstrate relative costs and benefits of social work services

- Advance professional education in light of changing contexts for practice

- Understand the impact of legislation and social policy on the clients and communities we serve (Retrieved from http://www.socialworkpolicy.org/research)

I still do not know what my research question will be for my senior thesis, but I am beginning to pare down some topics that interest me such as:

- Effects of childhood trauma

- The school-to-prison pipeline

- Trauma-informed therapies within prisons

- Effectiveness of prison diversion programs

8 thoughts on “ So why is research important to social work? ”

try explaining in detail

article quite informing for an amateur in research

In doing any of interventions;evidence based is needed. Not intuition,you need to do assessment of the problem before intervention.Then again you need to to evaluation on the service you provided if has positive impact to your client.

It is a very informative piece of work

try explaining in detail the points listed as to where the nexus between Research and Social work lie

are there means to conduct dual research projects with your institutions?

Akulu muziika zithu zonse ap tisamachiteso kuvutika iyayi 😏😏

CCleaner (Crap Cleaner) yasir252 is a freeware system optimization, privacy, and cleaning tool. It removes unused files from your system allowing Windows

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The link between social work research and practice

When thinking about social work, some may consider the field to solely focus on clinical interventions with individuals or groups.

There may be a mistaken impression that research is not a part of the social work profession. This is completely false. Rather, the two have been and will continue to need to be intertwined.

This guide covers why social workers should care about research, how both social work practice and social work research influence and guide each other, how to build research skills both as a student and as a professional working in the field, and the benefits of being a social worker with strong research skills.

A selection of social work research jobs are also discussed.

- Social workers and research

- Evidence-based practice

- Practice and research

- Research and practice

- Build research skills

- Social worker as researcher

- Benefits of research skills

- Research jobs

Why should social workers care about research?

Sometimes it may seem as though social work practice and social work research are two separate tracks running parallel to each other – they both seek to improve the lives of clients, families and communities, but they don’t interact. This is not the way it is supposed to work.

Research and practice should be intertwined, with each affecting the other and improving processes on both ends, so that it leads to better outcomes for the population we’re serving.

Section 5 of the NASW Social Work Code of Ethics is focused on social workers’ ethical responsibilities to the social work profession. There are two areas in which research is mentioned in upholding our ethical obligations: for the integrity of the profession (section 5.01) and for evaluation and research (section 5.02).

Some of the specific guidance provided around research and social work include:

- 5.01(b): …Social workers should protect, enhance, and improve the integrity of the profession through appropriate study and research, active discussion, and responsible criticism of the profession.

- 5.01(d): Social workers should contribute to the knowledge base of social work and share with colleagues their knowledge related to practice, research, and ethics…

- 5.02(a) Social workers should monitor and evaluate policies, the implementation of programs, and practice interventions.

- 5.02(b) Social workers should promote and facilitate evaluation and research to contribute to the development of knowledge.

- 5.02(c) Social workers should critically examine and keep current with emerging knowledge relevant to social work and fully use evaluation and research evidence in their professional practice.

- 5.02(q) Social workers should educate themselves, their students, and their colleagues about responsible research practices.

Evidence-based practice and evidence-based treatment

In order to strengthen the profession and determine that the interventions we are providing are, in fact, effective, we must conduct research. When research and practice are intertwined, this leads practitioners to develop evidence-based practice (EBP) and evidence-based treatment (EBT).

Evidence-based practice is, according to The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) , a process involving creating an answerable question based on a client or organizational need, locating the best available evidence to answer the question, evaluating the quality of the evidence as well as its applicability, applying the evidence, and evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of the solution.

Evidence-based treatment is any practice that has been established as effective through scientific research according to a set of explicit criteria (Drake et al., 2001). These are interventions that, when applied consistently, routinely produce improved client outcomes.

For example, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was one of a variety of interventions for those with anxiety disorders. Researchers wondered if CBT was better than other intervention options in producing positive, consistent results for clients.

So research was conducted comparing multiple types of interventions, and the evidence (research results) demonstrated that CBT was the best intervention.

The anecdotal evidence from practice combined with research evidence determined that CBT should become the standard treatment for those diagnosed with anxiety. Now more social workers are getting trained in CBT methods in order to offer this as a treatment option to their clients.

How does social work practice affect research?

Social work practice provides the context and content for research. For example, agency staff was concerned about the lack of nutritional food in their service area, and heard from clients that it was too hard to get to a grocery store with a variety of foods, because they didn’t have transportation, or public transit took too long.

So the agency applied for and received a grant to start a farmer’s market in their community, an urban area that was considered a food desert. This program accepted their state’s version of food stamps as a payment option for the items sold at the farmer’s market.

The agency used their passenger van to provide free transportation to and from the farmer’s market for those living more than four blocks from the market location.

The local university also had a booth each week at the market with nursing and medical students checking blood pressure and providing referrals to community agencies that could assist with medical needs. The agency was excited to improve the health of its clients by offering this program.

But how does the granting foundation know if this was a good use of their money? This is where research and evaluation comes in. Research could gather data to answer a number of questions. Here is but a small sample:

- How many community members visited each week and purchased fruits and vegetables?

- How many took advantage of the transportation provided, and how many walked to the market?

- How many took advantage of the blood pressure checks? Were improvements seen in those numbers for those having repeat blood pressure readings throughout the market season?

- How much did the self-reported fruit and vegetable intake increase for customers?

- What barriers did community members report in visiting and buying food from the market (prices too high? Inconvenient hours?)

- Do community members want the program to continue next year?

- Was the program cost-effective, or did it waste money by paying for a driver and for gasoline to offer free transportation that wasn’t utilized? What are areas where money could be saved without compromising the quality of the program?

- What else needs to be included in this program to help improve the health of community members?

How does research affect social work practice?

Research can guide practice to implement proven strategies. It can also ask the ‘what if’ or ‘how about’ questions that can open doors for new, innovative interventions to be developed (and then research the effectiveness of those interventions).

Engel and Schutt (2017) describe four categories of research used in social work:

- Descriptive research is research in which social phenomena are defined and described. A descriptive research question would be ‘How many homeless women with substance use disorder live in the metro area?’

- Exploratory research seeks to find out how people get along in the setting under question, what meanings they give to their actions, and what issues concern them. An example research question would be ‘What are the barriers to homeless women with substance use disorder receiving treatment services?’

- Explanatory research seeks to identify causes and effects of social phenomena. It can be used to rule out other explanations for findings and show how two events are related to each other. An explanatory research question would be ‘Why do women with substance use disorder become homeless?’

- Evaluation research describes or identifies the impact of social programs and policies. This type of research question could be ‘How effective was XYZ treatment-first program that combined housing and required drug/alcohol abstinence in keeping women with substance use disorder in stable housing 2 years after the program ended?’

Each of the above types of research can answer important questions about the population, setting or intervention being provided. This can help practitioners determine which option is most effective or cost-efficient or that clients are most likely to adhere to. In turn, this data allows social workers to make informed choices on what to keep in their practice, and what needs changing.

How to build research skills while in school

There are a number of ways to build research skills while a student. BSW and MSW programs require a research course, but there are other ways to develop these skills beyond a single class:

- Volunteer to help a professor working in an area of interest. Professors are often excited to share their knowledge and receive extra assistance from students with similar interests.

- Participate in student research projects where you’re the subject. These are most often found in psychology departments. You can learn a lot about the informed consent process and how data is collected by volunteering as a research participant. Many of these studies also pay a small amount, so it’s an easy way to earn a bit of extra money while you’re on campus.

- Create an independent study research project as an elective and work with a professor who is an expert in an area you’re interested in. You’d design a research study, collect the data, analyze it, and write a report or possibly even an article you can submit to an academic journal.

- Some practicum programs will have you complete a small evaluation project or assist with a larger research project as part of your field education hours.

- In MSW programs, some professors hire students to conduct interviews or enter data on their funded research projects. This could be a good part time job while in school.

- Research assistant positions are more common in MSW programs, and these pay for some or all your tuition in exchange for working a set number of hours per week on a funded research project.

How to build research skills while working as a social worker

Social service agencies are often understaffed, with more projects to complete than there are people to complete them.

Taking the initiative to volunteer to survey clients about what they want and need, conduct an evaluation on a program, or seeing if there is data that has been previously collected but not analyzed and review that data and write up a report can help you stand out from your peers, be appreciated by management and other staff, and may even lead to a raise, a promotion, or even new job opportunities because of the skills you’ve developed.

Benefits of being a social worker with strong research skills

Social workers with strong research skills can have the opportunity to work on various projects, and at higher levels of responsibility.

Many can be promoted into administration level positions after demonstrating they understand how to conduct, interpret and report research findings and apply those findings to improving the agency and their programs.

There’s also a level of confidence knowing you’re implementing proven strategies with your clients.

Social work research jobs

There are a number of ways in which you can blend interests in social work and research. A quick search on Glassdoor.com and Indeed.com retrieved the following positions related to social work research:

- Research Coordinator on a clinical trial offering psychosocial supportive interventions and non-addictive pain treatments to minimize opioid use for pain.

- Senior Research Associate leading and overseeing research on a suite of projects offered in housing, mental health and corrections.

- Research Fellow in a school of social work

- Project Policy Analyst for large health organization

- Health Educator/Research Specialist to implement and evaluate cancer prevention and screening programs for a health department

- Research Interventionist providing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for insomnia patients participating in a clinical trial

- Research Associate for Child Care and Early Education

- Social Services Data Researcher for an organization serving adults with disabilities.

- Director of Community Health Equity Research Programs evaluating health disparities.

No matter your population or area of interest, you’d likely be able to find a position that integrated research and social work.

Social work practice and research are and should remain intertwined. This is the only way we can know what questions to ask about the programs and services we are providing, and ensure our interventions are effective.

There are many opportunities to develop research skills while in school and while working in the field, and these skills can lead to some interesting positions that can make a real difference to clients, families and communities.

Drake, R. E., Goldman, H., Leff, H. S., Lehman, A. F., Dixon, L., Mueser, K. T., et al. (2001). Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services, 52(2), 179-182.

Engel, R.J., & Schutt, R.K. (2017). The Practice of Research in Social Work. Sage.

National Association of Social Workers. (n.d). Evidence Based Practice. Retrieved from: https://www.socialworkers.org/News/Research-Data/Social-Work-Policy-Research/Evidence-Based-Practice

Social Work Research Methods That Drive the Practice

Social workers advocate for the well-being of individuals, families and communities. But how do social workers know what interventions are needed to help an individual? How do they assess whether a treatment plan is working? What do social workers use to write evidence-based policy?

Social work involves research-informed practice and practice-informed research. At every level, social workers need to know objective facts about the populations they serve, the efficacy of their interventions and the likelihood that their policies will improve lives. A variety of social work research methods make that possible.

Data-Driven Work

Data is a collection of facts used for reference and analysis. In a field as broad as social work, data comes in many forms.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

As with any research, social work research involves both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Quantitative Research

Answers to questions like these can help social workers know about the populations they serve — or hope to serve in the future.

- How many students currently receive reduced-price school lunches in the local school district?

- How many hours per week does a specific individual consume digital media?

- How frequently did community members access a specific medical service last year?

Quantitative data — facts that can be measured and expressed numerically — are crucial for social work.

Quantitative research has advantages for social scientists. Such research can be more generalizable to large populations, as it uses specific sampling methods and lends itself to large datasets. It can provide important descriptive statistics about a specific population. Furthermore, by operationalizing variables, it can help social workers easily compare similar datasets with one another.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative data — facts that cannot be measured or expressed in terms of mere numbers or counts — offer rich insights into individuals, groups and societies. It can be collected via interviews and observations.

- What attitudes do students have toward the reduced-price school lunch program?

- What strategies do individuals use to moderate their weekly digital media consumption?

- What factors made community members more or less likely to access a specific medical service last year?

Qualitative research can thereby provide a textured view of social contexts and systems that may not have been possible with quantitative methods. Plus, it may even suggest new lines of inquiry for social work research.

Mixed Methods Research

Combining quantitative and qualitative methods into a single study is known as mixed methods research. This form of research has gained popularity in the study of social sciences, according to a 2019 report in the academic journal Theory and Society. Since quantitative and qualitative methods answer different questions, merging them into a single study can balance the limitations of each and potentially produce more in-depth findings.

However, mixed methods research is not without its drawbacks. Combining research methods increases the complexity of a study and generally requires a higher level of expertise to collect, analyze and interpret the data. It also requires a greater level of effort, time and often money.

The Importance of Research Design

Data-driven practice plays an essential role in social work. Unlike philanthropists and altruistic volunteers, social workers are obligated to operate from a scientific knowledge base.

To know whether their programs are effective, social workers must conduct research to determine results, aggregate those results into comprehensible data, analyze and interpret their findings, and use evidence to justify next steps.

Employing the proper design ensures that any evidence obtained during research enables social workers to reliably answer their research questions.

Research Methods in Social Work

The various social work research methods have specific benefits and limitations determined by context. Common research methods include surveys, program evaluations, needs assessments, randomized controlled trials, descriptive studies and single-system designs.

Surveys involve a hypothesis and a series of questions in order to test that hypothesis. Social work researchers will send out a survey, receive responses, aggregate the results, analyze the data, and form conclusions based on trends.

Surveys are one of the most common research methods social workers use — and for good reason. They tend to be relatively simple and are usually affordable. However, surveys generally require large participant groups, and self-reports from survey respondents are not always reliable.

Program Evaluations

Social workers ally with all sorts of programs: after-school programs, government initiatives, nonprofit projects and private programs, for example.

Crucially, social workers must evaluate a program’s effectiveness in order to determine whether the program is meeting its goals and what improvements can be made to better serve the program’s target population.

Evidence-based programming helps everyone save money and time, and comparing programs with one another can help social workers make decisions about how to structure new initiatives. Evaluating programs becomes complicated, however, when programs have multiple goal metrics, some of which may be vague or difficult to assess (e.g., “we aim to promote the well-being of our community”).

Needs Assessments

Social workers use needs assessments to identify services and necessities that a population lacks access to.

Common social work populations that researchers may perform needs assessments on include:

- People in a specific income group

- Everyone in a specific geographic region

- A specific ethnic group

- People in a specific age group

In the field, a social worker may use a combination of methods (e.g., surveys and descriptive studies) to learn more about a specific population or program. Social workers look for gaps between the actual context and a population’s or individual’s “wants” or desires.

For example, a social worker could conduct a needs assessment with an individual with cancer trying to navigate the complex medical-industrial system. The social worker may ask the client questions about the number of hours they spend scheduling doctor’s appointments, commuting and managing their many medications. After learning more about the specific client needs, the social worker can identify opportunities for improvements in an updated care plan.

In policy and program development, social workers conduct needs assessments to determine where and how to effect change on a much larger scale. Integral to social work at all levels, needs assessments reveal crucial information about a population’s needs to researchers, policymakers and other stakeholders. Needs assessments may fall short, however, in revealing the root causes of those needs (e.g., structural racism).

Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials are studies in which a randomly selected group is subjected to a variable (e.g., a specific stimulus or treatment) and a control group is not. Social workers then measure and compare the results of the randomized group with the control group in order to glean insights about the effectiveness of a particular intervention or treatment.

Randomized controlled trials are easily reproducible and highly measurable. They’re useful when results are easily quantifiable. However, this method is less helpful when results are not easily quantifiable (i.e., when rich data such as narratives and on-the-ground observations are needed).

Descriptive Studies

Descriptive studies immerse the researcher in another context or culture to study specific participant practices or ways of living. Descriptive studies, including descriptive ethnographic studies, may overlap with and include other research methods:

- Informant interviews

- Census data

- Observation

By using descriptive studies, researchers may glean a richer, deeper understanding of a nuanced culture or group on-site. The main limitations of this research method are that it tends to be time-consuming and expensive.

Single-System Designs

Unlike most medical studies, which involve testing a drug or treatment on two groups — an experimental group that receives the drug/treatment and a control group that does not — single-system designs allow researchers to study just one group (e.g., an individual or family).

Single-system designs typically entail studying a single group over a long period of time and may involve assessing the group’s response to multiple variables.

For example, consider a study on how media consumption affects a person’s mood. One way to test a hypothesis that consuming media correlates with low mood would be to observe two groups: a control group (no media) and an experimental group (two hours of media per day). When employing a single-system design, however, researchers would observe a single participant as they watch two hours of media per day for one week and then four hours per day of media the next week.

These designs allow researchers to test multiple variables over a longer period of time. However, similar to descriptive studies, single-system designs can be fairly time-consuming and costly.

Learn More About Social Work Research Methods

Social workers have the opportunity to improve the social environment by advocating for the vulnerable — including children, older adults and people with disabilities — and facilitating and developing resources and programs.

Learn more about how you can earn your Master of Social Work online at Virginia Commonwealth University . The highest-ranking school of social work in Virginia, VCU has a wide range of courses online. That means students can earn their degrees with the flexibility of learning at home. Learn more about how you can take your career in social work further with VCU.

From M.S.W. to LCSW: Understanding Your Career Path as a Social Worker

How Palliative Care Social Workers Support Patients With Terminal Illnesses

How to Become a Social Worker in Health Care

Gov.uk, Mixed Methods Study

MVS Open Press, Foundations of Social Work Research

Open Social Work Education, Scientific Inquiry in Social Work

Open Social Work, Graduate Research Methods in Social Work: A Project-Based Approach

Routledge, Research for Social Workers: An Introduction to Methods

SAGE Publications, Research Methods for Social Work: A Problem-Based Approach

Theory and Society, Mixed Methods Research: What It Is and What It Could Be

READY TO GET STARTED WITH OUR ONLINE M.S.W. PROGRAM FORMAT?

Bachelor’s degree is required.

VCU Program Helper

This AI chatbot provides automated responses, which may not always be accurate. By continuing with this conversation, you agree that the contents of this chat session may be transcribed and retained. You also consent that this chat session and your interactions, including cookie usage, are subject to our privacy policy .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 1. Science and social work

Chapter outline.

- How do social workers know what to do? (12 minute read time)

- The scientific method (16 minute read time)

- Evidence-based practice (11 minute read time)

- Social work research (10 minute read time)

Content warning: Examples in this chapter contain references to school discipline, child abuse, food insecurity, homelessness, poverty and anti-poverty stigma, anti-vaccination pseudoscience, autism, trauma and PTSD, mental health stigma, susto and culture-bound syndromes, gender-based discrimination at work, homelessness, psychiatric hospitalizations, substance use, and mandatory treatment.

1.1 How do social workers know what to do?

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Reflect on how we, as social workers, make decisions

- Differentiate between micro-, meso-, and macro-level analysis

- Describe the concept of intuition, its purpose in social work, and its limitations

- Identify specific errors in thinking and reasoning

What would you do?

Case 1: Imagine you are a clinical social worker at a children’s mental health agency. One day, you receive a referral from your town’s middle school about a client who often skips school, gets into fights, and is disruptive in class. The school has suspended him and met with the parents on multiple occasions, who say they practice strict discipline at home. Yet the client’s behavior has worsened. When you arrive at the school to meet with your client, who is also a gifted artist, you notice he seems to have bruises on his legs, has difficulty maintaining eye contact, and appears distracted. Despite this, he spends the hour painting and drawing, during which time you are able to observe him.

- Given your observations of your client’s strengths and challenges, what intervention would you select, and how could you determine its effectiveness?

Case 2: Imagine you are a social worker working in the midst of an urban food desert (a geographic area in which there is no grocery store that sells fresh food). As a result, many of your low-income clients either eat takeout, or rely on food from the dollar store or a convenience store. You are becoming concerned about your clients’ health, as many of them are obese and say they are unable to buy fresh food. Your clients tell you that they have to rely on food pantries because convenience stores are expensive and often don’t have the right kinds of food for their families. You have spent the past month building a coalition of community members to lobby your city council. The coalition includes individuals from non-profit agencies, religious groups, and healthcare workers.

- How should this group address the impact of food deserts in your community? What intervention(s) do you suggest? How would you determine whether your intervention was effective?

Case 3: You are a social worker working at a public policy center whose work focuses on the issue of homelessness. Your city is seeking a large federal grant to address this growing problem and has hired you as a consultant to work on the grant proposal. After interviewing individuals who are homeless and conducting a needs assessment in collaboration with local social service agencies, you meet with city council members to talk about potential opportunities for intervention. Local agencies want to spend the money to increase the capacity of existing shelters in the community. In addition, they want to create a transitional housing program at an unused apartment complex where people can reside upon leaving the shelter, and where they can gain independent living skills. On the other hand, homeless individuals you interview indicate that they would prefer to receive housing vouchers to rent an apartment in the community. They also fear the agencies running the shelter and transitional housing program would impose restrictions and unnecessary rules and regulations, thereby curbing their ability to freely live their lives. When you ask the agencies about these client concerns, they state that these clients need the structure and supervision provided by agency support workers.

- Which kind of program should your city choose to implement? Which is most likely to be effective and why?

Assuming you’ve taken a social work course before, you will notice that these case studies cover different levels of analysis in the social ecosystem—micro, meso, and macro. At the micro-level , social workers examine the smallest levels of interaction; in some cases, just “the self” alone (e.g. the child in case one).

When social workers investigate groups and communities, such as our food desert in case 2, their inquiry is at the meso-level .

At the macro-level , social workers examine social structures and institutions. Research at the macro-level examines large-scale patterns, including culture and government policy.

These three domains interact with one another, and it is common for a research project to address more than one level of analysis. For example, you may have a study about individuals at a case management agency (a micro-level study) that impacts the organization as a whole (meso-level) and incorporates policies and cultural issues (macro-level). Moreover, research that occurs on one level is likely to have multiple implications across domains.

How do social workers know what to do?

Welcome to social work research. This chapter begins with three problems that social workers might face in practice, and three questions about what a social worker should do next. If you haven’t already, spend a minute or two thinking about the three aforementioned cases and jot down some notes. How might you respond to each of these cases?

I assume it is unlikely you are an expert in the areas of children’s mental health, community responses to food deserts, and homelessness policy. Don’t worry, I’m not either. In fact, for many of you, this textbook will likely come at an early point in your graduate social work education, so it may seem unfair for me to ask you what the ‘right’ answers are. And to disappoint you further, this course will not teach you the ‘right’ answer to these questions. It will, however, teach you how to answer these questions for yourself, and to find the ‘right’ answer that works best in each unique situation.

Assuming you are not an experienced practitioner in the areas described above, you likely used intuition (Cheung, 2016). [1] when thinking about what you would do in each of these scenarios. Intuition is a “gut feeling” about what to think about and do, often based on personal experience. What we experience influences how we perceive the world. For example, if you’ve witnessed representations of trauma in your practice, personal life, or in movies or television, you may have perceived that the child in case one was being physically abused and that his behavior was a sign of trauma. As you think about problems such as those described above, you find that certain details stay with you and influence your thinking to a greater degree than others. Using past experiences, you apply seemingly relevant knowledge and make predictions about what might be true.

Over a social worker’s career, intuition evolves into practice wisdom . Practice wisdom is the “learning by doing” that develops as a result of practice experience. For example, a clinical social worker may have a “feel” for why certain clients would be a good fit to join a particular therapy group. This idea may be informed by direct experience with similar situations, reflections on previous experiences, and any consultation they receive from colleagues and/or supervisors. This “feel” that social workers get for their practice is a useful and valid source of knowledge and decision-makin – do not discount it.

On the other hand, intuitive thinking can be prone to a number of errors. We are all limited in terms of what we know and experience. One’s economic, social, and cultural background will shape intuition, and acting on your intuition may not work in a different sociocultural context. Because you cannot learn everything there is to know before you start your career as a social worker, it is important to learn how to understand and use social science to help you make sense of the world and to help you make sound, reasoned, and well-thought out decisions.

Social workers must learn how to take their intuition and deepen or challenge it by engaging with scientific literature. Similarly, social work researchers engage in research to make certain their interventions are effective and efficient (see Section 1.4 for more information). Both of these processes–consuming and producing research–inform the social justice mission of social work. That’s why the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), who accredits the MSW program you are in, requires that you engage in social science.

Competency 4: Engage In Practice-informed Research and Research-informed Practice Social workers understand quantitative and qualitative research methods and their respective roles in advancing a science of social work and in evaluating their practice. Social workers know the principles of logic, scientific inquiry, and culturally informed and ethical approaches to building knowledge. Social workers understand that evidence that informs practice derives from multi-disciplinary sources and multiple ways of knowing. They also understand the processes for translating research findings into effective practice. Social workers: • use practice experience and theory to inform scientific inquiry and research; • apply critical thinking to engage in analysis of quantitative and qualitative research methods and research findings; and • use and translate research evidence to inform and improve practice, policy, and service delivery. (CSWE, 2015). [2]

Errors in thinking

We all rely on mental shortcuts to help us figure out what to do in a practice situation. All people, including you and me, must train our minds to be aware of predictable flaws in thinking, termed cognitive biases . Here is a link to the Wikipedia entry on cognitive biases, as well as an interactive list . As you can see, there are many types of biases that can results in irrational conclusions.

The most important error in thinking for social scientists to be aware of is the concept of confirmation bias . Confirmation bias involves observing and analyzing information in a way that confirms what you already believe to be true. We all arrive at each moment with a set of personal beliefs, experiences, and worldviews that have been developed and ingrained over time. These patterns of thought inform our intuitions, primarily in an unconscious manner. Confirmation bias occurs when our mind ignores or manipulates information to avoid challenging what we already believe to be true.

In our second case study, we are trying to figure out how to help people who receive SNAP (sometimes referred to as Food Stamps) who live in a food desert. Let’s say we have arrived at a policy solution and are now lobbying the city council to implement it. There are many who have negative beliefs about people who are “on welfare.” These people may believe individuals who receive social welfare benefits spend their money irresponsibly, are too lazy to get a job, and manipulate the system to maintain or increase their government payout.

Those espousing this belief may point to an example such as Louis Cuff , who bought steak and lobster with his SNAP benefits and resold them for a profit. However, they are falling prey to assuming that one person’s bad behavior reflects upon an entire group of people. City council members who hold these beliefs may ignore the truth about the client population—that people experiencing poverty usually spend their money responsibly and that they genuinely need help accessing fresh and healthy food. In this way, confirmation bias often makes people less capable of empathizing with one another because they have difficulty accepting alternative perspectives.

Errors in reasoning

Because the human mind is prone to errors, when anyone makes a statement about what is true or what should be done in a given situation, errors in logic may abound. Think back to the case studies at the beginning of this section. You most likely had some ideas about what to do in each case. Below are some of the most common logical fallacies and the ways in which they may negatively influence a social worker:

- Making hasty generalization : when a person draws conclusions before having enough information. A social worker may apply lessons from a handful of clients to an entire population of people (see Louis Cuff , above). It is important to examine the scientific literature in order to avoid this.

- Confusing correlation with causation : when one concludes that because two things are correlated (as one changes, the other changes), they must be causally related. As an example, a social worker might observe both an increase in the minimum wage and higher unemployment in certain areas of the city. However, just because two things changed at the same time does not mean they are causally related. Social workers should explore other factors that might impact causality.

- Going down a slippery slope : when a person concludes that we should not do something because something far worse will happen if we do so. For example, a social worker may seek to increase a client’s opportunity to choose their own activities, but face opposition from those who believe it will lead to clients making unreasonable demands. Clearly, this is nonsense. Changes that foster self-determination are unlikely to result in client revolt. Social workers should be skeptical of arguments opposing small changes because one argues that radical changes are inevitable.

- Appealing to authority : when a person draws a conclusion by appealing to the authority of an expert or reputable individual, rather than through the strength of the claim. You have likely encountered individuals who believe they are correct because another in a position of authority told them so. Instead, we should work to build a reflective and critical approach to practice that questions authority.

- Hopping on the bandwagon : when a person draws a conclusion consistent with popular belief. Just because something is popular does not mean it is correct. Fashionable ideas come and go. Social workers should engage with trendy ideas but must ground their work in scientific evidence rather than popular opinion.

- Using a straw man : when a person does not represent their opponent’s position fairly or with sufficient depth. For example, a social worker advocating for a new group home may depict homeowners that are opposed to clients living in their neighborhood as individuals concerned only with their property values. However, this may not be the case. Social workers should instead engage deeply with all sides of an issue and represent them accurately.

Key Takeaways

- Social work research occurs at the micro-, meso-, and macro-level.

- Intuition is a powerful, though limited, source of information when making decisions.

- All human thought is subject to errors in thinking and reasoning.

- Scientific inquiry accounts for cognitive biases by applying an organized, logical way of observing and theorizing about the world.

- Think about a social work topic you might want to study this semester as part of a research project. How do individuals commit specific errors in logic or reasoning when discussing a specific topic (e.g. Louis Cuff)? How can using scientific evidence help you combat popular myths that are based on erroneous thinking?

- Reflect on the strengths and limitations of your personal experiences as a way to guide your work with diverse populations. Describe an instance when your intuition may have resulted in biased or misguided thinking or behavior in a social work practice situation.

1.2 The scientific method

Learning objectives.

- Define science and social science

- Describe the differences between objective and subjective truth(s)

- Identify how qualitative and quantitative data are analyzed differently and how they can be used together

- Delineate the features of science that distinguish it from pseudoscience

If I asked you to draw a picture of science, what would you draw? My guess is it would be something from a chemistry or biology classroom, like a microscope or a beaker. Maybe something from a science fiction movie. All social workers use scientific thinking in their practice. However, social workers have a unique understanding of what science means, one that is (not surprisingly) more open to the unexpected and human side of the social world.

Science and not-science

In social work, science is a way of ‘knowing’ that attempts to systematically collect and categorize facts or truths. A key word here is systematically –conducting science is a deliberate process. Scientists gather information about facts in a way that is organized and intentional, and usually follows a set of predetermined steps. Social work is not a science, but social work is informed by social science ; the science of humanity, social interactions, and social structures. In other words, social work research uses organized and intentional procedures to uncover facts or truths about the social world. And social workers rely on social scientific research to promote change.

Science can also be thought of in terms of its impostor, pseudoscience. Pseudoscience refers to beliefs about the social world that are unsupported by scientific evidence. These claims are often presented as though they are based on science. But once researchers test them scientifically, they are demonstrated to be false. A scientifically uninformed social work practitioner using pseudoscience may recommend any number of ineffective, misguided, or harmful interventions. Pseudoscience often relies on information and scholarship that has not been reviewed by experts or offers a selective and biased reading of reviewed literature.

An example of pseudoscience comes from anti-vaccination activists. Despite overwhelming scientific consensus that vaccines do not cause autism, a very vocal minority of people continue to believe that they do. Anti-vaccination advocates present their information as based in science, as seen here at Green Med Info . The author of this website shares real abstracts from scientific journal articles and studies but will only provide information on articles that show the potential dangers of vaccines, without showing any research that prevents the positive and safe side of vaccines. Green Med Info is an example of confirmation bias, as all data presented on the website supports what the pseudo-scientific researcher believes to be true. For more information on assessing causal relationships, consult Chapter 6 , where we discuss causality in detail.

The values and practices associated with the scientific method work to overcome common errors in thinking (such as confirmation bias). First, the scientific method uses established techniques from the literature to determine the likelihood of something being true or false. The research process often cites these techniques, reasons for their use, and how researchers came to the decision to use said techniques. However, each technique comes with its own strengths and limitations. Rigorous science is about making the best choice, being open about your process, and allowing others to check your work. It is important to remember that there is no “perfect” study – all research has limitations because all scientific methods come with limitations.

Skepticism and debate

Unfortunately, the “perfect” researcher does not exist. Scientists are human, so they are subject to error and bias, such as gravitating toward fashionable ideas and thinking their work is more important than others’ work. Theories and concepts fade in and out of use and may be tossed aside when new evidence challenges their truth. Part of the challenge in your research projects will be finding what you believe about an issue, rather than summarizing what others think about the topic. Good science, just like good social work practice, is authentic. When I see students present their research projects, those that are the strongest deliver both passionate and informed arguments about their topic area.

Good science is also open to ongoing questioning. Scientists are fundamentally skeptical. As such, they are likely to pursue alternative explanations. They might question the design of a study or replicate it to see if it works in another context. Scientists debate what is true until they arrive at a majority consensus. If you’ve ever heard that 97% of climate scientists agree that global warming is due to human activity [3] or that 99% of economists agree that tariffs make the economy worse [4] , you are seeing this sociology of science in action. This skepticism will help to catch situations in which scientists who make the oh-so-human mistakes in thinking and reasoning reviewed in Section 1.1.

Skepticism also helps to identify unethical scientists, as with Andrew Wakefield’s study linking the MMR vaccination and autism. When other researchers looked at his data, they found that he had altered the data to match his own conclusions and sought to benefit financially from the ensuing panic about vaccination (Godlee, Smith, & Marcovitch, 2011). [5] This highlights another key value in science: openness.

Through the use of publications and presentations, scientists share the methods used to gather and analyze data. The trend towards open science has also prompted researchers to share data as well. This in turn enables other researchers to re-run, replicate, and validate analyses and results. A major barrier to openness in science is the paywall. When you’ve searched online for a journal article (we will review search techniques in Chapter 3), you have likely run into the $25-$50 price tag. Don’t despair – your university should subscribe to these journals. However, the push towards openness in science means that more researchers are sharing their work in open access journals, which are free for people to access (like this textbook!). These open access journals do not require a university subscription to view.

Openness also means engaging the broader public about your study. Social work researchers conduct studies to help people, and part of scientific work is making sure your study has an impact. For example, it is likely that many of the authors publishing in scientific journals are on Twitter or other social media platforms, relaying the importance of study findings. They may create content for popular media, including newspapers, websites, blogs, or podcasts. It may lead to training for agency workers or public administrators. Regrettably, academic researchers have a reputation for being aloof and disengaged from the public conversation. However, this reputation is slowly changing with the trend towards public scholarship and engagement. For example, see this recent section of the Journal of the Society of Social Work and Research on public impact scholarship .

Science supported by empirical data

Pseudoscience is often doctored up to look like science, but the surety with which its advocates speak is not backed up by empirical data. Empirical data refers to information about the social world gathered and analyzed through scientific observation or experimentation. Theory is also an important part of science, as we will discuss in Chapter 5 . However, theories must be supported by empirical data–evidence that what we think is true really exists in the world.

There are two types of empirical data that social workers should become familiar with. Quantitative data refers to numbers and qualitative data usually refers to word data (like a transcript of an interview) but can also refer to pictures, performances, and other means of expressing oneself. Researchers use specific methods designed to analyze each type of data. Together, these are known as research methods , or the methods researchers use to examine empirical data.

Objective truth

In our vaccine example, scientists have conducted many studies tracking children who were vaccinated to look for future diagnoses of autism (see Taylor et al. 2014 for a review). This is an example of using quantitative data to determine whether there is a causal relationship between vaccination and autism. By examining the number of people who develop autism after vaccinations and controlling for all of the other possible causes, researchers can determine the likelihood of whether vaccinations cause changes in the brain that are eventually diagnosed as autism.

In this case, the use of quantitative data is a good fit for disproving myths about the dangers of vaccination. When researchers analyze quantitative data, they are trying to establish an objective truth. An objective truth is always true, regardless of context. Generally speaking, researchers seeking to establish objective truth tend to use quantitative data because they believe numbers don’t lie. If repeated statistical analyses don’t show a relationship between two variables, like vaccines and autism, that relationship almost certainly does not exist. By boiling everything down to numbers, we can minimize the biases and logical errors that human researchers bring to the scientific process. That said, the interpretation of those numbers is always up for debate. That process can be subjective.

This approach to finding truth probably sounds similar to something you heard in your middle school science classes. When you learned about gravitational force or the mitochondria of a cell, you were learning about the theories and observations that make up our understanding of the physical world. We assume that gravity is real and that the mitochondria of a cell are real. Mitochondria are easy to spot with a powerful microscope and we can observe and theorize about their function in a cell. The gravitational force is invisible, but clearly apparent from observable facts, such as watching an apple fall. If we were unable to perceive mitochondria or gravity, they would still be there, doing their thing, because they exist independent of our observation of them.

Let’s consider a social work example. Scientific research has established that children who are subjected to severely traumatic experiences are more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health disorder (e.g., Mahoney, Karatzias, & Hutton, 2019). [6] A diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is considered objective, and may refer to a mental health issue that exists independent of the individual observing it and is highly similar in its presentation across clients. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2017) [7] identifies a group of criteria which is based on unbiased, neutral client observations. These criteria are based in research, and render an objective diagnosis more likely to be valid and reliable. Through the clinician’s observations and the client’s description of their symptoms, an objective determination of a mental health diagnosis can be made.

Subjective truth(s)

For those of you skeptics, you may ask yourself: but does a diagnosis tell a client’s whole story? No. It does not tell you what the client thinks and feels about their diagnosis, for example. Receiving a diagnosis of PTSD may be a relief for a client. The diagnosis may suggest the words to describe their experiences. In addition, this diagnosis may provide a direction for therapeutic work, as there are evidence-based interventions clinicians can use with each diagnosis. On the other hand, a client may feel shame and view the diagnosis as a label, defining them in a negative way and limiting their potential (Barsky, 2015). [8]

Imagine if we surveyed people with PTSD to see how they interpreted their diagnosis. Objectively, we could determine whether more people said the diagnosis was, overall, a positive or negative event for them. However, it is unlikely that the experience of receiving a diagnosis was either completely positive or completely negative. In social work, we know that a client’s thoughts and emotions are rarely binary, either/or situations. Clients likely feel a mix of positive and negative thoughts and emotions during the diagnostic process. These messy bits are subjective truths , or the thoughts and feelings that arise as people interpret and make meaning of situations. Uniquely, looking for subjective truths can help us see the contradictory and multi-faceted nature of people’s thoughts, and qualitative data allows us to avoid oversimplifying them into negative and positive feelings that could be counted, as in quantitative data. It is the role of a researcher, just like a practitioner, to seek to understand things from the perspective of the client. Unlike with objective truth, this will not lead to a general sense of what is true for everyone, but rather what is true for that one person.

Subjective truths are best expressed through qualitative data, or through the use of words (not numbers). For example, we might invite a client to tell us how they felt after they were first diagnosed, after they spoke with family, and over the course of the therapeutic process. While it may look different from what we normally think of as science (e.g. pharmaceutical studies), these stories are indeed a rich source of data for scientific analysis. However, it is impossible to analyze what this client said without also considering the sociocultural context in which they live. For example, the concept of PTSD is generated from Western thought and philosophy. How might people from other cultures understand trauma differently?

In the DSM-5 classification of mental health disorders, there is a list of culture-bound syndromes which appear only in certain cultures. For example, susto describes a unique cluster of symptoms experienced by Latin Americans after a traumatic event (Nogueira, Mari, & Razzouk, 2015). [9] Susto involves more physical symptoms than a traditional PTSD diagnosis. Indeed, many of these syndromes do not fit within a Western conceptualization of mental health because they differentiate less between the mind and body. To a Western scientist, susto may seem less real than PTSD. To someone from Latin America, their symptoms may not fit neatly into the PTSD framework developed in Western nations . Science has historically privileged knowledge from the United States and other nations in the West and Global North , marking them as objectively true. The objectivity of Western science as universally applicable to all cultures has been increasingly called into question as science has become less dominated by white males, and interaction between cultures and groups becomes broadly more democratic. Clearly, what is true depends in part on the context in which it is observed.

In this way, social scientists have a unique task. People are both objects and subjects. Objectively, you could quantify how tall a person is, what car they drive, how many adverse childhood experiences they had, or their score on a PTSD checklist. Subjectively, you could understand how a person made sense of a traumatic incident or how it contributed to certain patterns in thinking, negative feelings, or opportunities for growth, for example. It is this added dimension that renders social science unique to natural science, which focuses almost exclusively on quantitative data and objective truth. For this reason, this book is divided between projects using qualitative data and quantitative data.

There is no “better” or “more true” way of approaching social science. Instead, the methods a researcher chooses should match the question they ask. If you want to answer, “do vaccines cause autism?” you should choose methods appropriate to answer that question. It seeks an objective truth–one that is true for everyone, regardless of context. Studies like these use quantitative data and statistical analyses to test mathematical relationships between variables. If, on the other hand, you wanted to know “what does a diagnosis of PTSD mean to clients?” you should collect qualitative data and seek subjective truths. You will gather stories and experiences from clients and interpret them in a way that best represents their unique and shared truths. Where there is consensus, you will report that. Where there is contradiction, you will report that as well.

Mixed methods

In this textbook, we will treat quantitative and qualitative research methods separately. However, it is important to remember that a project can include both approaches. A mixed methods study, which we will discuss more in chapter 6, requires thinking through a more complicated project that includes at least one quantitative component, one qualitative component, and a plan to incorporate both approaches together. As a result, mixed methods projects may require more time for conceptualization, data collection, and analysis.

Finding patterns

Regardless of whether you are seeking objective or subjective truths, research and scientific inquiry aim to find and explain patterns. Most of the time, a pattern will not explain every single person’s experience, a fact about social science that is both fascinating and frustrating. Even individuals who do not know each other can create patterns that persist over time. Those new to social science may find these patterns frustrating because they may believe that the patterns describing their sex, age, or some other facet of their lives don’t represent their experience. It’s true. A pattern can exist among your cohort without your individual participation in it. There is diversity within diversity.

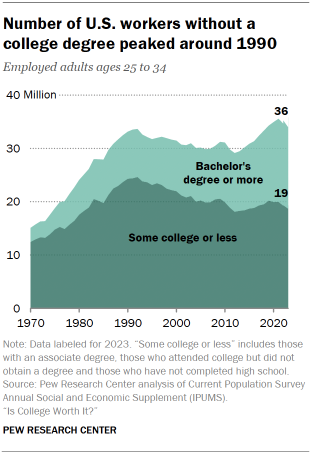

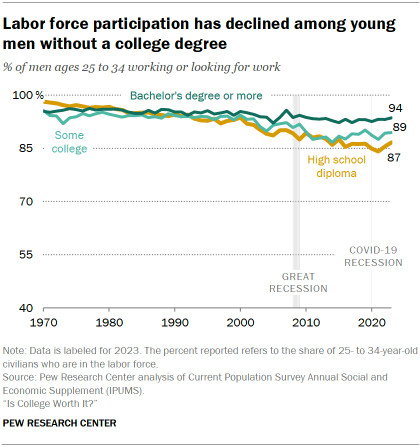

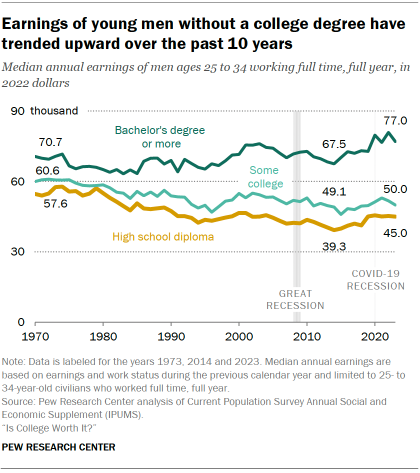

Let’s consider some specific examples. You probably wouldn’t be surprised to learn that a person’s social class background has an impact on their educational attainment and achievement. You may be surprised to learn that people select romantic partners that have similar educational attainment, which in turn, impacts their children’s educational attainment (Eika, Mogstad, & Zafar, 2019). [10] . People who have graduated college pair off with other college graduates, as so forth. This, in turn, reinforces existing inequalities, stratifying society by those who have the opportunity to complete college and those who don’t.

People who object to these findings tend to cite evidence from their own personal experience. However, the problem with this response is that objecting to a social pattern on the grounds that it doesn’t match one’s individual experience misses the point about patterns. Patterns don’t perfectly predict what will happen to an individual person. Yet, they are a reasonable guide that, when systematically observed, can help guide social work thought and action. When we don’t investigate these patterns scientifically, we are subject to developing stereotypes, biases, and other harmful beliefs.

A final note on qualitative and quantitative methods

There is not one superior way to find patterns that help us understand the world. As we will learn about in Chapter 5 , there are multiple philosophical, theoretical, and methodological ways to approach scientific truth. Qualitative methods aim to provide an in-depth understanding of a relatively small number of cases. They also provide a voice for the client. Quantitative methods offer less depth on each case but can say more about broad patterns because they typically focus on a much larger number of cases. A researcher should approach the process of scientific inquiry by formulating a clear research question and using the methodological tools best suited to that question.

Believe it or not, there are still significant methodological battles being waged in the academic literature on objective vs. subjective social science. Usually, quantitative methods are viewed as “more scientific” and qualitative methods are viewed as “less scientific.” Part of this battle is historical. As the social sciences developed, they were compared with the natural sciences, especially physics, which rely on mathematics and statistics to come to a truth. It is a hotly debated topic whether social science should adopt the philosophical assumptions of the natural sciences—with its emphasis on prediction, mathematics, and objectivity—or use a different set of tools—contextual understanding, language, and subjectivity—to find scientific truth.

You are fortunate to be in a profession that values multiple scientific ways of knowing. The qualitative/quantitative debate is fueled by researchers who may prefer one approach over another, either because their own research questions are better suited to one particular approach or because they happened to have been trained in one specific method. In this textbook, we’ll operate from the perspective that qualitative and quantitative methods are complementary rather than competing. While these two methodological approaches certainly differ, the main point is that they simply have different goals, strengths, and weaknesses. A social work researcher should select the method(s) that best match(es) the question they are asking.

- Social work is informed by science.

- Social science is concerned with both objective and subjective knowledge.

- Social science research aims to understand patterns in the social world.

- Social scientists use both qualitative and quantitative methods, which, while different, are often complementary.

Examine a pseudoscientific claim you’ve heard on the news or in conversation with others. Why do you consider it to be pseudoscientific? What empirical data can you find from a quick internet search that would demonstrate it lacks truth?

- Consider a topic you might want to study this semester as part of a research project. Provide a few examples of objective and subjective truths about the topic, even if you aren’t completely certain they are correct. Identify how objective and subjective truths differ.

1.3 Evidence-based practice

- Explain how social workers produce and consume research as part of practice

- Review the process of evidence-based practice and how social workers apply research knowledge with clients and groups

“Why am I in this class?”

“When will I ever use this information?”

While students aren’t always so direct, I would wager a guess that these questions are on the mind of almost every student in a research methods class. And they are valid and important questions to ask! While it may seem strange, the answer is that you will probably use these skills often. Social workers engage with research on a daily basis by consuming it through popular media, social work education, and advanced training. They also often contribute to research projects, adding new scientific information to what we know. As professors, we also sometimes hear from field supervisors who say that research competencies are unimportant in their setting. One might wonder how these organizations measure program outcomes, report the impact of their program to board members or funding agencies, or create new interventions grounded in social theory and empirical evidence.

Social workers as research consumers

Whether you know it or not, your life is impacted by research every day. Many of our laws, social policies, and court proceedings are grounded in some degree of empirical research and evidence (Jenkins & Kroll-Smith, 1996). [11] That’s not to say that all laws and social policies are good or make sense. But you can’t have an informed opinion about any of them without understanding where they come from, how they were formed, and what their evidence base is. In order to be effective practitioners across micro, meso, and macro domains, social workers need to understand the root causes and policy solutions to social problems their clients are experiencing.

A recent lawsuit against Walmart provides an example of social science research in action. A sociologist named Professor William Bielby was enlisted by plaintiffs to conduct an analysis of Walmart’s personnel policies in order to support their claim that Walmart engages in gender discriminatory practices. Bielby’s analysis shows that Walmart’s compensation and promotion decisions may indeed have been vulnerable to gender bias. In June 2011, the United States Supreme Court decided against allowing the case to proceed as a class-action lawsuit ( Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes , 2011). [12] While a class-action suit was not pursued in this case, consider the impact that such a suit against one of our nation’s largest employers could have had on companies, their employees, and even consumers around the country. [13]

A social worker might learn about this lawsuit through popular media, news media websites or television programs. Social science knowledge allows a social worker to apply a critical eye towards new information, regardless of the source. Unfortunately, popular media does not always report on scientific findings accurately. A social worker armed with scientific knowledge would be able to search for, read, and interpret the original study as well as other information that might challenge or support the study. As social work graduate students, you should be comfortable in your information literacy abilities, and your advocacy and practice should be grounded in these skills. Chapters 2, 3, and 4 of this textbook focus on information literacy , or how to understand what we already know about a topic and contribute to that body of knowledge.

When social workers consume research, they are usually doing so to inform their practice. Clinical social workers are required by a state licensing board to complete continuing education classes in order to remain informed on the latest information in their field. On the macro side, social workers at public policy think tanks consume information to inform advocacy and public awareness campaigns. Regardless of the role of the social worker, practice must be informed by research.

Evidence-based practice

Consuming research is the first component of evidence-based practice (EBP). Drisko and Grady (2015) [14] present EBP as a process composed of “four equally weighted parts: 1) current client needs and situation, (2) the best relevant research evidence, (3) client values and preferences, and (4) the clinician’s expertise” (p. 275). It is not simply “doing what the literature says,” but is rather a process by which practitioners examine the literature, client, self, and context to inform interventions with clients and systems (McNeese & Thyer, 2004). [15] It is a collaboration between social worker, client, and context. As we discussed in Section 1.2, the patterns discovered by scientific research are not applicable to all situations. Instead, we rely on our critical thinking skills to apply scientific knowledge to real-world situations.

The bedrock of EBP is a proper assessment of the client or client system. Once we have a solid understanding of what the issue is, we can evaluate the literature to determine whether there are any interventions that have been shown to treat the issue, and if so, which have been shown to be the most effective. You will learn those skills in the next few chapters. Once we know what our options are, we should be upfront with clients about each option, what the interventions look like, and what the expected outcome will be. Once we have client feedback, we use our expertise and practice wisdom to make an informed decision about how to move forward.

If this sounds familiar, it’s the same approach a doctor, physical therapist, or other health professional would use. This highlights a common critique of EBP: it is too focused on micro-level, clinical social work practice. Not every social worker is a clinical social worker. While there is a large body of literature on EBP for clinical practice, the same concepts apply to other social work roles as well. A social work manager should endeavor to be familiar with evidence-based management styles, and a social work policy advocate should argue for evidence-based policies.

In agency-based social work practice, EBP can take on a different role due to the complexities of the grant funding process. Funders naturally require agencies to demonstrate that their practice is effective. Agencies are almost always required to document that they are achieving the outcomes they intended. However, funders sometimes require agencies to choose from a limited list of interventions determined to be evidence-based practices. Not included in this model are clinical expertise and client values, which are key components of EBP and the therapeutic process. According to some funders, EBP is not a process conducted by a practitioner but instead consists of a list of interventions. Similar dynamics are at play in private clinical practice, in which insurance companies may specify the modality of therapy offered. For example, insurance companies may favor short-term, solution-focused therapy which minimizes cost. But what happens when someone has an idea for a new kind of intervention? How do new approaches get “on the list” of EBPs of grant funders?

Social workers as research producers

Innovation in social work is incredibly important. Social workers work on wicked problems for their careers. For those of you who have practice experience, you may have had an idea of how to better approach a practice situation. That is another reason you are here in a research methods class. You (really!) will have bright ideas about what to do in practice. Sam Tsemberis relates an “ Aha! ” moment from his practice in this Ted talk on homelessness . While a faculty member at the New York University School of Medicine, he noticed a problem with people cycling in and out of the local psychiatric hospital wards. Clients would arrive in psychiatric crisis, stabilize under medical supervision in the hospital, and end up back at the hospital in psychiatric crisis shortly after discharge.

When he asked the clients what their issues were, they said they were unable to participate in homelessness programs because they were not always compliant with medication for their mental health diagnosis and they continued to use drugs and alcohol. The housing supports offered by the city government required abstinence and medication compliance before one was deemed “ready” for housing. For these clients, the problem was a homelessness service system that was unable to meet clients where they were–ready for housing, but not ready for abstinence and psychiatric medication. As a result, chronically homeless clients were cycling in and out of psychiatric crises, moving back and forth from the hospital to the street.

The solution that Sam Tsemberis implemented and popularized is called Housing First , and is an approach to homelessness prevention that starts by, you guessed it, providing people with housing first and foremost. Tsemberis’s model addresses chronic homelessness in people with co-occurring disorders (those who have a diagnosis of a substance use and mental health disorder). The Housing First model states that housing is a human right: clients should not be denied their right to housing based on substance use or mental health diagnoses.

In Housing First programs, clients are provided housing as soon as possible. The Housing First agency provides wraparound treatment from an interdisciplinary team, including social workers, nurses, psychiatrists, and former clients who are in recovery. Over the past few decades, this program has gone from a single program in New York City to the program of choice for federal, state, and local governments seeking to address homelessness in their communities.

The main idea behind Housing First is that once clients have a residence of their own, they are better able to engage in mental health and substance use treatment. While this approach may seem logical to you, it is the opposite of the traditional homelessness treatment model. The traditional approach began with the client abstaining from drug and alcohol use and taking prescribed medication. Only after clients achieved these goals were they offered group housing. If the client remained sober and medication compliant, they could then graduate towards less restrictive individual housing.

Conducting and disseminating research allows practitioners to establish an evidence base for their innovation or intervention, and to argue that it is more effective than the alternatives, and should therefore be implemented more broadly. For example, by comparing clients who were served through Housing First with those receiving traditional services, Tsemberis could establish that Housing First was more effective at keeping people housed and at addressing mental health and substance use goals. Starting first with smaller studies and graduating to larger ones, Housing First built a reputation as an effective approach to addressing homelessness. When President Bush created the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness in 2003, Housing First was used in a majority of the interventions and its effectiveness was demonstrated on a national scale. In 2007, it was acknowledged as an evidence-based practice in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) EBP resource center. [16]

We suggest browsing around the SAMHSA EBP Resource Center and looking for interventions on topics that interest you. Other sources of evidence-based practices include the Cochrane Reviews digital library and Campbell Collaboration . In the next few chapters, we will talk more about how to search for and locate literature about clinical interventions. The use of systematic reviews , meta-analyses , and randomized controlled trials are particularly important in this regard, types of research we will describe more in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4.